Abstract

Natural gas plays a pivotal role in the global energy landscape under the dual challenges of energy transition and climate change. However, the impurities present within natural gas pose several disadvantages, including corrosion of transportation pipelines, toxicity, hydrate formation, and a reduction in the fuel’s calorific value. Membrane separation technology has been recognized as an ideal approach for natural gas purification owing to its advantages of low energy consumption, operational simplicity, and excellent separation performance. This review summarizes recent progress in the development of advanced membrane materials, including polymer bulk membranes, two-dimensional (2D) nanosheet membranes, mixed-matrix membranes (MMMs), surface-modified membranes, and carbon molecular sieve membranes (CMSMs). The fundamental separation mechanisms—such as solution-diffusion, molecular sieving, adsorption-selectivity, and competitive sorption and surface diffusion—are analyzed in detail. Moreover, the critical scientific questions and technological challenges in this field are discussed in depth. Finally, future research perspectives are proposed to guide the rational design and practical application of high-performance membranes for natural gas separation.

1. Introduction

Natural gas, as a low-cost and high-efficiency clean energy source, plays a crucial role in ensuring the sustainable global energy supply and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. It primarily consists of the combustible component methane (CH4), which typically accounts for 70–95% of its composition. However, natural gas also contains substantial amounts of non-combustible impurities such as carbon dioxide (CO2), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), nitrogen (N2), and water vapor (H2O) [1]. Among these, CO2 and H2S are acidic gases that can easily form hydrosulfuric acid and carbonic acid upon contact with water. These impurities can corrode transportation pipelines, with H2S itself being toxic, and its combustion produces sulfur dioxide (SO2), a major contributor to acid rain [2]. Additionally, inert gases like N2 lower the purity of natural gas, reducing the calorific value of the fuel. Particularly, the presence of water vapor, when transported under high pressure and low temperature conditions, can form hydrate crystals with methane, ethane, and other hydrocarbons. This can block pipelines, valves, instruments, and other equipment, leading to a rapid increase in transport pressure, interruptions in gas flow, and potential equipment damage [3,4]. Therefore, purification is essential before natural gas can meet pipeline transportation standards. Consequently, the development of clean, efficient, and facile separation technologies has become an urgent necessity.

Commonly used natural gas purification techniques include amine absorption, physical solvent methods, membrane separation, cryogenic separation, and pressure swing adsorption [5,6,7,8]. Among these, membrane separation has emerged as one of the most promising approaches due to its remarkable advantages, including low energy consumption, cost-effectiveness, operational simplicity, modular design, and environmental friendliness [9,10,11]. It is particularly suitable for compact or space-limited applications [12]. In practical purification processes, membrane technology enables the simultaneous removal of multiple impurities from natural gas and exhibits excellent separation performance—both in permeability and selectivity—toward acidic gases such as H2S and CO2 [13,14]. However, conventional membrane materials rely on a single separation mechanism and are generally suitable only for mild purification conditions. Moreover, these membranes are constrained by the Robeson upper bound, which reflects the inherent trade-off between permeability and selectivity. They also suffer from limitations such as physical aging, susceptibility to blocking, and limited stability, making it difficult for them to meet the current pipeline transportation standards [15,16]. To overcome the limitations of conventional membranes, researchers have developed a variety of advanced high-performance membrane materials through chemical structure regulation and physical morphology design [17,18,19]. By employing strategies such as surface functionalization, internal structural optimization, and the incorporation of composite components, these membranes achieve a favorable balance between high permeability and enhanced selectivity [15,19]. Furthermore, they exhibit superior resistance to plasticization, improved anti-blocking performance, and excellent long-term operational stability, offering a promising pathway for efficient natural gas purification [17,20,21].

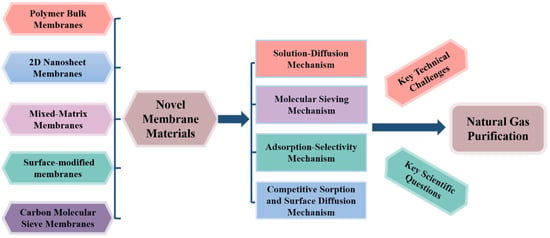

Therefore, this review provides an overview of recent advances in the design, fabrication, and modification of novel membrane materials for natural gas purification. The separation mechanisms of these membranes in removing impurity gases are analyzed in detail, and future research directions in this field are discussed. This work aims to provide theoretical insights and practical guidance for the development of low-carbon and efficient membrane-based gas purification technologies. The overall framework of this review is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the overall framework and conceptual roadmap.

2. Gas Purification Efficiency of Membrane Technologies and Other Separation Methods

2.1. Efficiency of Membrane Separation Technology

Membrane separation technology offers several intrinsic advantages, including low energy consumption, modular equipment design, simple operation, and strong adaptability to compact or space-limited installations. Its separation efficiency is fundamentally governed by the membrane material’s permeability and selectivity [22]. Permeability reflects the amount of gas that can pass through a unit area of membrane per unit time, representing the processing throughput, whereas selectivity describes the membrane’s ability to discriminate between different gas species, which directly determines product purity and recovery [23]. The trade-off between these two parameters defines the overall purification potential of membrane materials in natural gas treatment [24].

Emerging membrane materials—compared with conventional polymeric membranes such as polyimides or cellulose acetates—have focused on surpassing the Robeson limit, optimizing fabrication and operational conditions, and improving long-term stability [25]. These developments have led to multiple high-performance membranes capable of significantly enhancing natural gas purification efficiency. Presently, single-stage membrane systems, while effective at removing H2O, H2S, and CO2 despite the Robeson upper bound constraint, perform poorly in rejecting N2 and heavy hydrocarbons due to pore blockage by slow-permeating heavy hydrocarbons and the similar permeabilities of N2 and CH4 [26,27].

2.2. Other Gas Purification Technologies

In addition to membrane separation, several established techniques are widely used for natural gas purification, including amine absorption, pressure swing adsorption, and cryogenic separation [5]. Their comparative performance, advantages, and limitations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of gas purification efficiency and characteristics of different separation technologies.

Amine absorption, one of the most mature and reliable industrial processes, removes acidic impurities such as H2S and CO2 through reversible chemical reactions between these species and organic amine solvents [28,29]. It offers excellent purification efficiency, high processing capacity, broad applicability, stable operation, and regenerable solvents [30]. However, this method requires large and complex equipment, involves high energy consumption for solvent regeneration, may cause corrosion, and generates secondary pollutants [31,32].

Pressure swing adsorption relies on differences in adsorption capacity of gas components on porous adsorbents under high pressure. Impurities such as H2O, CO2, and H2S are selectively adsorbed and subsequently desorbed by lowering the pressure [5,33]. Pressure swing adsorption enables deep removal of moisture and CO2, provides high product purity, relatively low energy consumption, and allows automated operation under mild conditions [34]. Nevertheless, its treatment capacity is restricted by the size of adsorption columns, and during regeneration, a portion of the adsorbed CH4 is inevitably lost, reducing overall recovery. Additionally, its performance is less satisfactory when treating high-sulfur natural gas [35].

Cryogenic separation exploits differences in boiling points among gas components [36]. By lowering the temperature, simultaneous removal of H2O and heavy hydrocarbons can be achieved with high efficiency [37]. This method becomes especially attractive for large-scale applications due to its process simplicity and environmental compatibility [38]. However, its ability to deeply remove H2O is limited, and the formation of solid hydrates at low temperatures can block pipelines and equipment [39]. Furthermore, the severe low-temperature and high-pressure operating conditions impose strict requirements on equipment materials, increasing capital investment [37].

3. Membrane Materials for Natural Gas Purification

Novel membranes for natural gas purification can be broadly categorized into polymer bulk membranes, 2D nanosheet membranes, surface-modified membranes, and carbon molecular sieve membranes. Owing to their unique physicochemical properties, each of these materials exhibits distinct advantages and significant development potential. Table 2 summarizes the separation performance of various membrane materials developed in recent years for the removal of impurities from natural gas, highlighting their effectiveness in purifying methane from common contaminants such as CO2, H2S, and H2O.

Table 2.

Separation performance of various emerging membrane materials for removing impurities from natural gas.

3.1. Polymer Bulk Membranes

Polymer bulk membranes are the most widely used materials in natural gas purification due to their low cost and ease of large-scale production [60]. According to their glass transition temperature (Tg), they can be categorized into rubbery and glassy polymers [13]. At the operating temperature, the polymer chains in rubbery membranes are in a thermally mobile state, providing excellent elasticity and gas permeability. Common examples include polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [61,62] and polyether block amide (Pebax) [48,63], whose separation mechanism is primarily governed by solubility selectivity. However, the flexible structure of rubbery polymers makes it difficult to achieve the required gas separation performance, and under high pressure, surface defects can lead to swelling, thereby significantly shortening membrane lifespan [64,65,66]. In contrast, glassy polymers such as cellulose acetate (CA), polysulfone (PSF), and polyimide (PI) are non-equilibrium supercooled liquids characterized by high rigidity, superior selectivity, and excellent thermal and chemical stability [67,68]. Their separation performance mainly depends on the intrinsic microporous structure between polymer chains, which is dominated by differences in diffusion coefficients, leading to outstanding selectivity [69]. However, these membranes generally possess a dense, non-porous internal structure, which results in inherently low permeability. In addition, they are prone to plasticization and pronounced physical aging when exposed to high-pressure operating conditions [70,71,72].

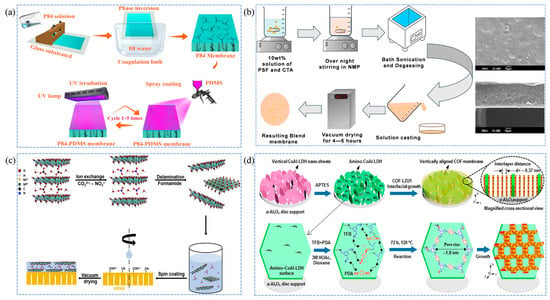

Current research on polymer bulk membranes primarily focuses on functional modification, polymer innovation, and optimization of fabrication procedures, aiming to develop ideal polymeric membranes that simultaneously exhibit high permeability, strong selectivity, and outstanding operational stability [73]. Among them, polyimides have been widely engineered by introducing bulky pendant groups or applying crosslinking strategies, both of which significantly enhance their position relative to the Robeson upper bound and improve resistance to physical aging [74]. Polymer composite membrane, which integrate rubbery and glassy polymers in a well-designed configuration, further address the limitations of single-component polymer membranes, such as inadequate separation performance, physical aging, and poor long-term stability, while maintaining high cost-effectiveness [75]. Suleman et al. [40] fabricated PSF/PDMS composite membranes via a dip-coating process and systematically investigated the effects of operating pressure and blending ratio. Compared with pristine PSF membranes, the PSF/PDMS composites exhibited simultaneous enhancements in both permeability and selectivity. Notably, the permeability difference between CO2 and CH4 increased with rising pressure, while the CO2/CH4 selectivity improved significantly from 19.2 to 56.7. Building on this idea of functional enhancement, Li et al. [41] further explored membrane repair strategies by employing a rapid layer-by-layer assembly approach via PDMS spraying to restore copolyimide (P84) membranes. Under UV irradiation, the polymer membranes were able to self-heal within an ultrashort time (20–30 s), and their results showed that the P84-PDMS-3A membrane, prepared using a triple PDMS spraying concentration and two deposition cycles, delivered the best gas-separation performance. Compared with the original P84 membrane, the increased coating thickness reduced the permeability of larger molecules (CO2 and CH4), thereby widening the permeability gap between H2 and CH4 and resulting in a 2.4-fold enhancement in H2/CH4 selectivity, reaching as high as 231.9. The fabrication process is illustrated in Figure 2a. Roafi et al. [43] also successfully combined cellulose triacetate (CTA) and PSF polymer membranes. As illustrated in Figure 2b, their fabrication method yielded a dense, defect-free CTA/PSF membrane, which exhibited significantly enhanced selectivity without compromising permeability compared to the original CTA and PSF membranes, demonstrating great potential for CO2 removal.

Figure 2.

Schematic fabrication processes of membranes for natural gas purification. (a) Fabrication of P84-PDMS composite membranes [41]; (b) Fabrication of CTA/PSF membranes [43]; (c) Preparation of LDH membranes containing interlayer NO3− [45]; (d) Preparation of 2D COF-LZU1 membranes [47].

3.2. Two-Dimensional Nanosheet Membranes

Two-dimensional (2D) nanosheet membranes, including graphene oxide (GO) [44,76], MXene [77], 2D metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) [78], and layered double hydroxides (LDHs) [45], have attracted considerable attention due to their unique 2D nanoporous structures and tunable properties [79]. These membranes provide promising solutions to the limitations of conventional polymer membranes, such as low permeation flux, the Robeson upper bound, and suboptimal separation performance [80]. The precise control of interlayer spacing and surface functional groups of 2D nanosheets—typically achieved through physical intercalation, chemical etching, or related strategies—is crucial for constructing 2D nanosheet membranes, which enables the selective separation of different gas molecules [81]. For example, Ren et al. [44] used vacuum filtration to filter GO modified with polydopamine (PDA) and Zn2+ onto a polyethersulfone (PES) substrate, successfully preparing GO-PDA-Zn2+@PES nanosheet membrane materials. The crosslinking interactions between Zn2+ and PDA not only expanded the interlayer spacing of the GO framework and elongated the internal nanochannel structures, but also effectively repaired surface defects on the GO membrane. Moreover, the presence of water molecules under humid conditions facilitated preferential CO2 transport, resulting in a significantly enhanced CO2/CH4 selectivity of up to 32.9. In addition, due to the strong affinity between CO2 and the membrane surface, the CO2 permeability increased markedly by approximately 61% compared with pristine GO membranes.

However, in practical industrial applications, 2D nanomaterials are costly and prone to issues such as interlayer swelling, structural aging, and membrane blocking under harsh operating conditions [82,83,84]. Liu et al. [45] prepared a smooth-surfaced LDH membrane using a co-precipitation-hydrothermal aging method and found that the intrinsic nitrate ions (NO3−) within the interlayers could undergo ion exchange with CO2, converting into carbonate ions (CO32−). Owing to the high electronegativity and small size of CO32−, the interlayer spacing of the LDH decreased from 0.7 nm to 0.3 nm, which effectively enhanced the separation performance. When the membrane thickness was increased to 70 nm, the CO2/CH4 selectivity improved from 33 to 37. However, the permeability of both CO2 and CH4 decreased, dropping to 105 and 1, respectively. Furthermore, the LDH membrane maintained a CO2/CH4 selectivity of approximately 30 during a 144 h operation test, demonstrating excellent separation performance and stability. The fabrication process is illustrated in Figure 2c. Fan et al. [47] designed a vertical COF-LZU1 membrane, with its fabrication process detailed in Figure 2d. In contrast to a pure COF 2D membrane, this configuration features a more refined internal structure, which is attributed to a substantial increase in permeability up to 3800 GPU while retaining a CO2/CH4 selectivity of 31.6.

3.3. Mixed-Matrix Membranes

Mixed-matrix membranes (MMMs) are composite materials formed by uniformly dispersing porous fillers with excellent molecular sieving performance or high permeability, such as zeolites [85,86], MOFs [87,88], polystyrene [89], and 2D materials [90], into a polymer matrix. The incorporation of these fillers generates well-ordered and tunable pore structures within the polymer membrane, while interactions between the fillers and polymer chains restrict chain mobility [51,91]. This combination significantly enhances both the permeability and selectivity of the membrane, surpassing the Robeson upper bound of conventional polymer membranes, and integrates the advantages of both the polymer matrix and the porous fillers [48,49,50,92].

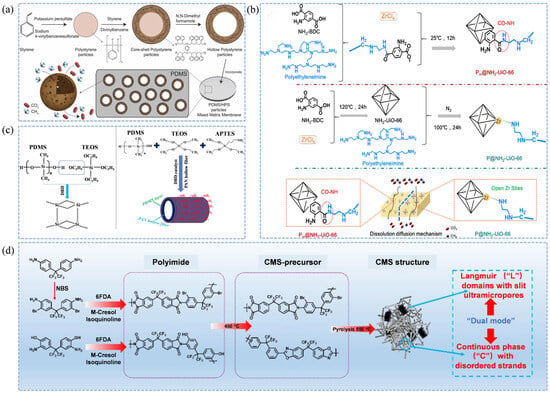

The structure and performance of porous fillers are critical factors in the development of MMMs [93,94]. Martínez-Izquierdo et al. [48] successfully prepared ultrasmall UiO-66-NO2 particles (4–6 nm) and co-embedded them with ZIF-94 into a Pebax polymer matrix, resulting in UiO-66/Pebax 1657 thin-film nanocomposite membranes. The abundant surface amino, nitro, and hydrophilic groups on these fillers enhanced interactions with CO2, increased the membrane’s hydrophilicity, and promoted CO2 affinity, thereby achieving improved CO2/CH4 selectivity. The compatibility between porous fillers and the polymer matrix is also crucial. Unlike conventional inorganic fillers, Guo et al. [49] employed an improved template polymerization method to synthesize hollow polystyrene (HPS) particles, which were incorporated into a PDMS polymer matrix to fabricate PDMS/HPS MMMs. The results demonstrated that both PDMS and HPS being polymeric materials ensured excellent interfacial compatibility; SEM characterization revealed a smooth membrane interface without observable defect pores. Moreover, both the CO2/CH4 permeability and selectivity increased with the loading of HPS, reaching a maximum at 4 wt%, showing significant improvements compared with pristine PDMS membranes (259% and 37%, respectively). The CO2 permeability increased from 1.45 GPU to 5.21 GPU, while the selectivity rose to 5.86. The fabrication process is illustrated in Figure 3a. Cui et al. [50] fabricated a Pin@NH2-UiO-66-PEI mixed matrix membrane, with the preparation process detailed in Figure 3b. The amino groups on the MOF surface enhanced the membrane’s affinity for CO2 and expanded its internal porous structure. Consequently, CO2/CH4 permeability and selectivity were increased by 21 times and 4 times, respectively, compared to the pristine PEI membrane.

Figure 3.

Schematic fabrication processes of membranes for natural gas purification. (a) Fabrication of PDMS/HPS MMMs [49]; (b) Fabrication of 30-Pin@NH2-UiO-66-PEI membranes [50]; (c) Fabrication of APTES/PDMS@PAN membranes [55]; (d) Thermal rearrangement and pyrolysis processes of PI-OH-550 and PI-Br-550 membranes [56].

3.4. Surface-Modified Membranes

Enhancing the separation performance of membrane materials has always been a key issue in natural gas purification. Surface-modified membranes improve the interaction between the membrane material and acidic gas molecules through physical or chemical modification of the membrane surface [95,96,97]. These modifications are generally classified into two main strategies: surface grafting and surface coating [98,99]. Surface coating refers to the deposition of a functional layer onto the membrane substrate via physical or chemical means, such as dip-coating [100], spray-coating [101], or vapor deposition [102]. Aydani et al. [52] prepared Si-functionalized SSZ-13 membranes by dip-coating SSZ-13 molecular sieve membranes into a silica sol solution. Experimental results demonstrated that the modification effectively reduced surface defects. The membrane exhibited optimal performance at an ethanol/TEOS molar ratio of 95.5, achieving a CO2/CH4 selectivity as high as 660. This enhancement is attributed to the formation of siloxane (Si-O-Si) on the surface, which repaired the non-selective pores of the SSZ-13 membrane and improved the CO2/CH4 selectivity by more than fivefold. Similarly, Zhang et al. [53] employed a simple dip-coating approach to deposit an ultrathin Pebax/PEGDA-MXene selective layer on PVDF hollow fibers. The resulting layer exhibited a precisely controlled interlayer spacing of 3.59 Å—between the kinetic diameters of CH4 and CO2—achieving efficient CO2/CH4 separation. Furthermore, the attachment of PEGDA onto MXene enhanced the membrane’s affinity for CO2, resulting in a remarkable improvement in CO2/CH4 selectivity, reaching as high as 66.2. Moreover, after a long-term test of 160 h, the membrane maintained excellent separation performance, with selectivity remaining stable at approximately 68.

Plasma-induced grafting and chemical grafting are two common surface grafting techniques, differing mainly in the methods used to generate reactive sites such as free radicals [103]. In chemical grafting, these active sites are typically initiated by chemical reagents (e.g., peroxides or azo compounds) or by radiation sources (e.g., ultraviolet light or electron beams) [104,105]. The generated reactive species subsequently induce polymerization with monomers containing target functional groups (such as -NH2, -COOH, or epoxy groups), forming grafted polymer chains on the membrane surface. Huang et al. [54] employed plasma treatment under a helium atmosphere to induce chain scission in an intrinsic microporous polymer (PIM-1) membrane, thereby adjusting its hierarchical microporous structure. This modification enabled efficient CO2/CH4 separation, achieving a selectivity of 32.6—an increase of 165% compared with pristine PDMS membranes. Although the CO2 permeability decreased to 2045 GPU, it retained 82.6% of the original value, effectively enhancing the CO2/CH4 separation performance. Similarly, Hu et al. [55] utilized the strong affinity between amino groups and acidic gases to introduce amino-functionalized silane coupling agent (APTES) onto the PDMS surface through chemical grafting. Using a polyacrylonitrile (PAN) hollow fiber as the support, they fabricated an APTES/PDMS@PAN composite membrane with significantly improved surface polarity and gas separation performance. The abundance of nitrogen atoms on the membrane surface increased the surface polarity and hydrophilicity of PDMS. Moreover, with increasing APTES content, the crosslinked network became progressively more flexible, resulting in a continuous enhancement of CO2 permeability. This strategy effectively addressed the low permeability issue of nonpolar pristine PDMS membranes. The fabrication process is illustrated in Figure 3c.

3.5. Carbon Molecular Sieve Membranes

Carbon molecular sieve membranes (CMSMs), as typical intrinsic microporous membranes, are generally derived from polymer precursors such as phenolic resin [106], PI [107,108], or PAN [109] via high-temperature pyrolysis. These membranes possess rigid micropores with sizes around 3–5 Å, which enhance interactions with gas molecules [57]. Owing to the distinct kinetic diameters of different gas molecules and their varying interactions with the pore walls, CMSMs can achieve exceptional separation performance [110,111]. Consequently, these membranes enable the simultaneous removal of CO2, H2S, H2, and N2 impurities. CMSMs also exhibit excellent thermal and chemical stability, addressing plasticization issues of conventional polymer membranes under extreme conditions, extending membrane lifetime, and reducing secondary contamination, thereby offering significant potential for natural gas purification [112,113]. However, the precise control of pore size, together with the intrinsic brittleness of CMSMs, poses significant challenges for the fabrication of practical membrane modules. In addition, the high cost of suitable polymer precursors remains a major limitation for their large-scale application [114,115]. Sun et al. [56] designed two polymer precursors, PI-Br and debrominated PI-OH, which were thermally rearranged via pyrolysis to produce PI-OH-550 and PI-Br-550. Both membranes demonstrated excellent CO2/CH4 separation performance. Notably, the debrominated PI-Br-550 exhibited a dramatic increase in ultramicroporosity (from 10.4% to 83.03%), a reduced interlayer spacing, and abundant active sites. These structural advantages enabled exceptionally high CO2/CH4 and H2/CH4 selectivities of 45.5 and 102, respectively. Furthermore, high-temperature carbonization generated rigid aromatic structures within the membrane, increasing chain spacing and resulting in a remarkable enhancement in gas permeability—up to 199 times. The fabrication process is illustrated in Figure 3d.

4. Separation Mechanisms

The gas separation mechanisms of membrane technologies primarily include the solution-diffusion mechanism, the molecular sieving mechanism, and the adsorption-selectivity mechanism. In the field of natural gas purification, the separation behavior of membrane materials is often complex, with multiple mechanisms acting synergistically. Depending on the characteristics of the membrane, strategies such as surface modification, bulk functionalization, and hybrid material incorporation can be employed to achieve multi-mechanism cooperative separation, thereby enhancing the overall performance of natural gas purification membranes.

4.1. Solution-Diffusion Mechanism

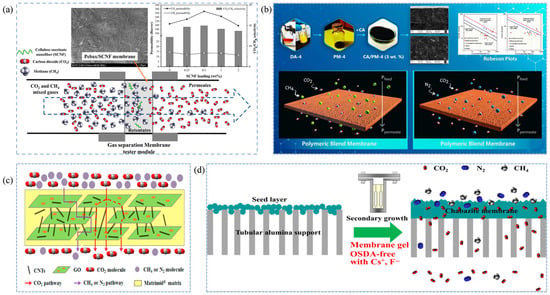

The solution-diffusion mechanism is the dominant separation mechanism for most dense membranes, such as polymeric membranes, and involves three consecutive steps: dissolution, diffusion, and desorption [116,117,118]. First, the gas impurities are adsorbed and dissolved in the membrane phase. This occurs because some membrane materials have a high free volume, and the solubility of gas molecules in the polymer membrane primarily depends on the critical temperature [119,120]. Polar molecules (such as H2O, H2S, CO2, etc.) tend to form hydrogen bonds or dipole interactions with the membrane and, having a higher critical temperature, are more likely to dissolve in the membrane phase [121]. Next, driven by the concentration gradient across the membrane, the gases diffuse to the other side of the membrane [122]. The rate of diffusion is determined primarily by the kinetic diameter and critical volume of the gas molecules. Finally, the gas species are desorbed from the membrane surface [123,124]. The core of this separation mechanism is the removal of polar gases, such as H2O, H2S, and CO2, from natural gas by exploiting the differences in solubility and diffusion coefficients of various gases [125,126]. For instance, Narkkun et al. [127] incorporated carboxyl-functionalized cellulose nanofibers (SCNF) into Pebax and fabricated Pebax/SCNF composite membranes via a solvent-casting method. Pebax provided abundant dissolution sites, while the SCNF regulated the microporous structure and enhanced CO2 solubility within the membrane, allowing CO2 to preferentially dissolve and diffuse through the membrane, resulting in efficient CO2/CH4 separation (Figure 4a). Akbarzadeh et al. [128] blended a glassy polymer (CA) with a rubbery polymer (PM-4) to prepare a high-performance polymer blend membrane (Figure 4b). Their study showed that the adsorption-dissolution sequence follows CO2 > CH4, and the presence of relatively large free-volume regions within the membrane promotes faster gas transport. This synergistic combination significantly improves both the permeability and selectivity compared with single-polymer membranes.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustrations of gas separation mechanisms in natural gas purification membranes. (a,b) Solution-diffusion mechanism [127,128]; (c,d) Molecular sieving mechanism [129,130].

4.2. Molecular Sieving Mechanism

The core of the porous-membrane sieving mechanism lies in utilizing uniformly distributed and nanoscale pore channels within the membrane to separate natural-gas components based on differences in their molecular kinetic diameters [57,131]. The kinetic diameters of typical gas species are as follows: H2 (2.89 Å), H2O (2.65 Å), CO2 (3.30 Å), H2S (3.60 Å), N2 (3.64 Å), CH2 (3.80 Å), and heavy hydrocarbons (>3.80 Å) [129,132]. To efficiently remove acidic impurities such as CO2 and H2S from natural gas, the membrane pore size is typically tuned to fall between the kinetic diameters of CO2 and CH4 [133,134]. When high-pressure feed gas flows across the membrane surface, gas molecules are first selectively adsorbed onto the membrane and migrate toward the pore entrances. Subsequently, because the pore size is much smaller than the mean free path of the gas molecules, transport inside the membrane is dominated by Knudsen diffusion [110,135]. In this regime, frequent collisions between gas molecules and pore walls occur, enabling smaller CO2 molecules to permeate through the nanochannels toward the permeate side, while larger CH4 molecules are effectively hindered. Finally, desorption and gas collection occur on the low-pressure side of the membrane [136,137]. Therefore, this separation process is primarily governed by molecular sieving, and the precise design of pore size and internal structure is crucial for achieving high selectivity in natural-gas purification [138]. For example, Li et al. [129] developed a Matrimid@CNT/GO mixed-matrix membrane with both high selectivity and permeability. The incorporation of CNTs and GO nanosheets not only enhanced membrane permeability but also created internal pore channels that allowed CO2 passage while hindering CH4 transport, accelerating CO2/CH4 separation (Figure 4c). Liu et al. [130] fabricated CHA zeolite membranes on Al2O3 substrates by employing a secondary-growth method using an OSDA gel containing cesium and fluoride salts. This approach increased the thickness of the selective layer to approximately 6 µm, thereby enhancing the molecular-sieving performance of the membrane (Figure 4d).

4.3. Adsorption-Selectivity Mechanism

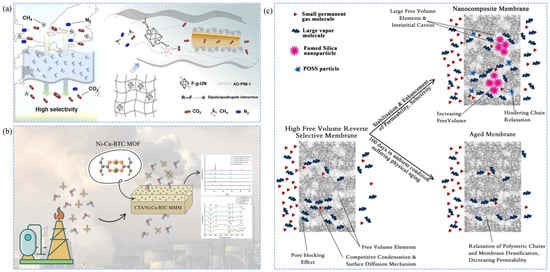

The adsorption-selectivity mechanism is based on differential interactions between membrane materials and gas components (CH4, H2S, CO2, N2, etc.) on the membrane surface or within the pores [139,140]. The process involves adsorption, diffusion, and desorption steps, with adsorption serving as the core of the mechanism. Natural gas molecules are first adsorbed and dissolved on the membrane surface [141,142]. Subsequently, driven by the concentration gradient, they diffuse from the high-pressure side of the membrane to the low-pressure side, and are finally desorbed and collected [143,144]. Adsorption can be classified into physical and chemical types [145]. Physical adsorption depends on the membrane’s specific surface area, pore size, and surface polarity, whereas chemical adsorption is typically achieved by introducing functional groups that specifically interact with gas impurities, such as -NH2, -OH, -F, -COOH, or metal coordination sites [146,147]. Zhang et al. [148] grafted -F onto Zr-MOF particles to obtain F-g-UN nanoparticles, which were uniformly dispersed in AO-PIM-1 polymer membranes. The -F groups in the F-g-UN particles formed dipole-quadrupole interactions with CO2, selectively adsorbing CO2 and thus enhancing the CO2/CH4 separation performance (Figure 5a). Asad et al. [149] developed a novel mixed-matrix membrane by incorporating cellulose triacetate with bimetallic MOFs (Ni-Cu-BTC). The resulting membrane exhibited remarkable improvements in CO2 permeability and CO2/CH4 selectivity, increasing by 91.7% and 154.8%, respectively. These enhancements are attributed to the introduction of Ni-Cu-BTC, which generates abundant porous structures and active sites (unsaturated Ni+ and Cu2+) within the membrane, thereby increasing the gas diffusion coefficient and strengthening the adsorption affinity toward CO2, as illustrated in Figure 5b.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustrations of gas separation mechanisms in natural gas purification membranes. (a,b) Adsorption-selectivity mechanism [148,149]; (c) Competitive sorption and surface diffusion mechanism [16].

4.4. Competitive Sorption and Surface Diffusion Mechanism

Unlike the adsorption-selectivity mechanism, the competitive sorption and surface diffusion mechanism emphasizes the competition of various gas impurities for limited sites on the membrane surface [150,151]. Adsorption dominates this process, controlling the entire transport mechanism, followed by mass transfer separation via surface diffusion [150]. This mechanism is primarily found in glassy polymer membranes with ultra-high permeability, where selectivity is mainly determined by the different permeation rates of molecules through the polymer membrane [57]. An increase in permeability leads to enhanced selectivity [22]. In the case of natural gas components, polar gas molecules and heavier hydrocarbon components have higher condensation rates and critical temperatures compared to CH4 [152]. This means that impurity gases have higher permeability in ultra-permeable polymer membranes (such as glassy polymer membranes), thus achieving selectivity differences and purifying natural gas impurities [153]. Khosravi et al. [16] developed a high free-volume glassy polymer membrane, a novel PMP-FS-POSS mixed nanocomposite membrane for removing heavy hydrocarbon impurities. With the introduction of functionalized POSS-FS binary fillers, the free volume of the original polymer membrane increased, leading to higher permeability and strengthening the competitive sorption and surface diffusion mechanism, significantly improving the C3H8/CH4 separation performance (Figure 5c).

5. Key Scientific Questions and Technical Challenges

5.1. Key Scientific Questions

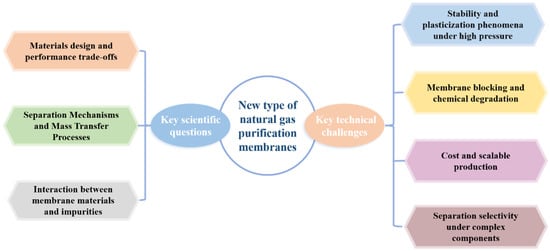

The application of membrane separation technology in natural gas purification involves several fundamental scientific questions. At its core, the challenge lies in understanding and optimizing the complex interactions among gas molecules, membrane materials, and operating environments. A summary of these key scientific questions and technical challenges is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration of key scientific questions and technical challenges.

(1) Material design and the permeability-selectivity trade-off. A central scientific challenge in membrane science is to surpass the Robeson upper bound by designing membrane materials that combine high permeability with high selectivity. The separation performance of a membrane is closely related to its internal structure: larger pores enhance permeability but reduce selectivity, and vice versa [13]. Thus, precise molecular-level design of membrane microstructures is required. Strategies such as grafting or crosslinking rigid side groups (e.g., phenyl, heterocyclic, or conjugated rings) onto polymer backbones can finely tune the free volume distribution (0.3–0.5 nm) and improve gas diffusivity [154,155]. Alternatively, introducing specific functional groups (e.g., -NH2, -COOH, -OH, or metal centers) into polymer chains can enhance affinity toward acidic gases while suppressing CH4 permeation [156].

(2) Separation mechanisms and mass transport processes. Gas transport in advanced membranes follows multiple concurrent mechanisms, and the dominant mechanism varies with membrane type. For example, rubbery polymers primarily follow the solution–diffusion mechanism, governed by gas solubility differences [157]; glassy polymers, 2D membranes, MMMs, and CMSMs are mainly controlled by molecular sieving or surface diffusion [54,158]; while surface-modified membranes rely predominantly on adsorption-selective interactions due to the presence of reactive sites or polar functional groups [140]. Therefore, elucidating the adsorption sites, diffusion pathways, and competitive transport behaviors of CO2, H2S, and CH4 within different membrane structures is critical for improving separation efficiency.

(3) Interactions between membrane materials and gas impurities. Trace impurities in natural gas (e.g., CO2, H2O, heavy hydrocarbons, mercaptans) are not inert components—they can interact physically or chemically with membrane materials, leading to irreversible structural changes [159]. For instance, water molecules can induce hydrogen-bond reorganization and swelling in polymers [160]; high-pressure CO2 can plasticize glassy polymers, weaken interchain forces, and reduce selectivity [161]; and the acidity of H2S may hydrolyze certain polymer chains (e.g., cellulose acetate) or corrode inorganic fillers [162]. Unraveling these interaction mechanisms is essential for developing anti-aging, blocking-resistant, and long-term stable membranes for industrial natural gas purification.

5.2. Key Technical Challenges

Despite the promising prospects of membrane technology, its large-scale industrial application in natural gas purification still faces several significant engineering and technical challenges.

(1) Stability and plasticization under high pressure. Wellhead natural gas typically exists at pressures of several hundred to over a thousand psi. Under such conditions, nearly all polymer membranes experience permeability decay, with CO2-induced plasticization being particularly problematic [161]. Plasticization causes polymer chains to swell and lose selectivity, severely limiting long-term performance. Developing structurally stable membranes capable of maintaining separation efficiency under high pressure—such as rigid CMSMs or MMMs reinforced with rigid fillers—represents a critical research direction.

(2) Membrane blocking and chemical degradation. Feed gases often contain water vapor, heavy hydrocarbons, liquid droplets, and solid particulates, which can condense or deposit on the membrane surface, forming fouling layers that block pores and reduce permeability. Moreover, the coexistence of H2S, O2, and H2O can trigger oxidation and acid–base reactions, leading to chemical degradation of the membrane material and deterioration of performance [163]. Therefore, membrane materials must possess anti-blocking and corrosion-resistant properties, and effective, low-cost pretreatment processes should be developed to minimize contamination and degradation.

(3) Cost and scalable fabrication. Many high-performance membranes suffer from complex synthesis routes, harsh fabrication conditions, and high production costs, making large-scale manufacture challenging. For example, MOF membranes involve multi-step synthesis and delicate crystal growth control [164]; CMSMs require high-temperature pyrolysis with low yield [165]; while MMMs and 2D membranes often suffer from poor reproducibility and difficult process control [166]. Achieving cost-effective, high-throughput, and continuous membrane fabrication with consistent quality is therefore a crucial step toward commercialization.

(4) Selectivity under complex gas compositions. In practical applications, natural gas streams contain multiple impurities such as CO2, H2S, H2O, N2, and heavy hydrocarbons [167]. These components can interact competitively within the membrane, leading to decreased selectivity and separation efficiency [162,163]. Designing membranes capable of maintaining high selectivity toward specific target impurities (e.g., H2S or CO2) under multicomponent conditions remains a persistent and complex challenge.

6. Conclusions and Outlook

6.1. Conclusions

As a clean, efficient, and straightforward separation method, membrane separation technology has been widely applied in the field of natural gas purification due to its excellent gas separation performance and promising development potential. This review summarized the design principles and research progress of various novel membrane materials—including polymer bulk membranes, MMMs, 2D nanosheet membranes, and surface-modified membranes. The major separation mechanisms of these membranes in natural gas purification, such as the solution–diffusion mechanism, molecular sieving through porous structures, and adsorption–selectivity mechanism, were analyzed in detail. Furthermore, the fundamental scientific challenges—such as the trade-off between permeability and selectivity, complex mass transfer mechanisms, and membrane–component interactions—were discussed. On this basis, key technical barriers including high-pressure stability, membrane blocking, fabrication cost, and selective separation under multicomponent gas mixtures were also examined.

6.2. Outlook

Although membrane technology has shown great potential in natural gas purification, several challenges remain—particularly concerning long-term stability, anti-blocking performance, and large-scale fabrication cost. Future research directions can be as follows.

(1) Development of new high-performance materials. Explore novel membrane materials such as porous organic frameworks, advanced 2D materials, and bio-based membranes with enhanced selectivity and stability.

(2) Optimization of membrane structure design. Construct asymmetric or composite hollow-fiber membranes to improve gas permeance, mechanical strength, and operational durability.

(3) Process integration and intelligent control. Integrate membrane separation with adsorption or absorption processes to achieve synergistic effects, while incorporating intelligent monitoring and control strategies for enhanced process efficiency.

(4) Green and sustainable development. Emphasize renewable raw materials, low-energy fabrication, and membrane recyclability to promote environmentally friendly and sustainable membrane technologies.

In summary, with continuous innovation in material design, structural optimization, and process integration, membrane technology is expected to play an increasingly significant role in the green purification of natural gas—contributing to energy efficiency, carbon reduction, and sustainable development in the energy sector.

Author Contributions

Q.F., Writing—original draft preparation; R.X., Visualization; C.Y., Conceptualization; M.X., Software; X.Z., Writing—review and editing; G.Z., Supervision, Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Qijie Fan, Rui Xiao, Cheng Yang were employed by the company Sichuan Lianfa Natural Gas Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, X.; Liu, G.; Jin, W. Natural gas purification by asymmetric membranes: An overview. Green Energy Environ. 2021, 6, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, M.; Koutník, P.; Kohout, J. Addressing Hydrogen Sulfide Corrosion in Oil and Gas Industries: A Sustainable Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, B.; Schorr, M.; Bastidas, J.M. The natural gas industry: Equipment, materials, and corrosion. Corros. Rev. 2015, 33, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toghyani, M.; Dadkhahfar, S.; Alishahi, A. Chapter Nineteen—Economic assessment and environmental challenges of methane storage and transportation. In Advances and Technology Development in Greenhouse Gases: Emission, Capture and Conversion; Rahimpour, M.R., Makarem, M.A., Meshksar, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 463–510. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.; Wen, C.; Yang, Y. Conventional Natural Gas Processing. In Supersonic Separators for Sustainable Gas Purification; Ding, H., Wen, C., Yang, Y., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Taqvi, S.A.A.; Ellaf, A. 1—Introduction to natural gas sweetening methods and technologies. In Advances in Natural Gas: Formation, Processing, and Applications. Volume 2: Natural Gas Sweetening; Rahimpour, M.R., Makarem, M.A., Meshksar, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jepleting, A.; Mecha, A.C.; Sombei, D.; Moraa, D.; Chollom, M.N. Potential of low-cost materials for biogas purification, a review of recent developments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 210, 115152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krótki, A.; Bigda, J.; Spietz, T.; Ignasiak, K.; Matusiak, P.; Kowol, D. Performance Evaluation of Pressure Swing Adsorption for Hydrogen Separation from Syngas and Water–Gas Shift Syngas. Energies 2025, 18, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, A.; Othman, M.H.D.; Jilani, A.; Khan, I.U.; Kamaludin, R.; Iqbal, J.; Al-Sehemi, A.G. Challenges, Opportunities and Future Directions of Membrane Technology for Natural Gas Purification: A Critical Review. Membranes 2022, 12, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, W.H.; Lau, K.K.; Lai, L.S.; Shariff, A.M.; Wang, T. Current development and challenges in the intensified absorption technology for natural gas purification at offshore condition. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2019, 71, 102977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wilson, T.J.; Maroon, C.R.; Laub, J.A.; Rheingold, S.E.; Vogiatzis, K.D.; Long, B.K. Vinyl-Addition Fluoroalkoxysilyl-Substituted Polynorbornene Membranes for CO2/CH4 Separation. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 7976–7988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Chen, P.; Li, C.; Qin, Y.; Lu, Q.; Li, M.; Liu, Q. Mixed matrix membranes for CO2 separation from associated gas: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 120179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnam, M.; bin Mukhtar, H.; bin Mohd Shariff, A. A Review on Glassy and Rubbery Polymeric Membranes for Natural Gas Purification. ChemBioEng Rev. 2021, 8, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezakazemi, M.; Heydari, I.; Zhang, Z. Hybrid systems: Combining membrane and absorption technologies leads to more efficient acid gases (CO2 and H2S) removal from natural gas. J. CO2 Util. 2017, 18, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.W.; Lokhandwala, K. Natural Gas Processing with Membranes: An Overview. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 2109–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A.; Vatani, A.; Mohammadi, T. Application of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane to the stabilization and performance enhancement of poly(4-methyl-2-pentyne) nanocomposite membranes for natural gas conditioning. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 45158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Bai, L.; Lindbråthen, A.; Pan, F.; Zhang, X.; He, X. Carbon membranes for CO2 removal: Status and perspectives from materials to processes. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 401, 126084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Megren, H. Natural Gas Purification Technologies—Major Advances for CO2 Separation and Future Directions. In Advances in Natural Gas Technology; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.B.; Kamcev, J.; Robeson, L.M.; Elimelech, M.; Freeman, B.D. Maximizing the right stuff: The trade-off between membrane permeability and selectivity. Science 2017, 356, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Othman, M.H.D.; Jilani, A.; Ismail, A.F.; Hashim, H.; Jaafar, J.; Zulhairun, A.K.; Rahman, M.A.; Rehman, G.U. ZIF-8 based polysulfone hollow fiber membranes for natural gas purification. Polym. Test 2020, 84, 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcheikhhamdon, Y.; Hoorfar, M. Natural gas quality enhancement: A review of the conventional treatment processes, and the industrial challenges facing emerging technologies. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 34, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholes, C.A.; Stevens, G.W.; Kentish, S.E. Membrane gas separation applications in natural gas processing. Fuel 2012, 96, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Xiao, G.; Hou, M.; Lu, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, T. Boosted gas separation performances of polyimide and thermally rearranged membranes by Fe-doping. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, R.; Al-Marzouqi, M. Insights on natural gas purification: Simultaneous absorption of CO2 and H2S using membrane contactors. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2011, 76, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, Z.; Lock, S.S.M.; Hira, N.e.; Ilyas, S.U.; Lim, L.G.; Lock, I.S.M.; Yiin, C.L.; Darban, M.A. A review on recent advances of cellulose acetate membranes for gas separation. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 19560–19580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, A.I.; Chen, Z.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Farghali, M.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Priya, A.K.; Hawash, H.B.; Yap, P.S. Membrane Technology for Energy Saving: Principles, Techniques, Applications, Challenges, and Prospects. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2024, 5, 2400011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sunarso, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, R. Current status and development of membranes for CO2/CH4 separation: A review. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2013, 12, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Hovland, J.; Jens, K.J. Amine reclaiming technologies in post-combustion carbon dioxide capture. J. Environ. Sci. 2015, 27, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubeva, I.A.; Dashkina, A.V.; Shulga, I.V. Demanding Problems of Amine Treating of Natural Gas: Analysis and Ways of Solution. Pet. Chem. 2020, 60, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, D.-Y.; Kang, H.; Lee, J.-W.; Park, Y.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, H. Energy-efficient natural gas hydrate production using gas exchange. Appl. Energy 2016, 162, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loachamin, D.; Casierra, J.; Calva, V.; Palma-Cando, A.; Ávila, E.E.; Ricaurte, M. Amine-Based Solvents and Additives to Improve the CO2 Capture Processes: A Review. ChemEngineering 2024, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Li, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, W.; Huang, H.; Peng, Z.; Gong, T. Advances on research of H2S removal by deep eutectic solvents as green solvent. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2025, 12, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemzadeh, S.; Rahimpour, M.R. 7—Swing processes for natural gas dehydration: Pressure, thermal, vacuum, and mixed swing processes. In Advances in Natural Gas: Formation, Processing, and Applications. Volume 4: Natural Gas Dehydration; Rahimpour, M.R., Makarem, M.A., Meshksar, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Khoramzadeh, E.; Bakhtyari, A.; Mofarahi, M. 10—Nitrogen rejection from natural gas by adsorption processes and swing technologies. In Advances in Natural Gas: Formation, Processing, and Applications. Volume 5: Natural Gas Impurities and Condensate Removal; Rahimpour, M.R., Makarem, M.A., Meshksar, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, K.d.N.; Trierweiler, J.O.; Farenzena, M.; Trierweiler, L.F. 7—Modeling and simulating natural gas dehydration by adsorption technologies: Pressure swing adsorption, temperature swing adsorption, vacuum swing adsorption. In Advances Natural Gas: Formation, Processing, and Applications. Volume 8: Natural Gas Process Modelling and Simulation; Rahimpour, M.R., Makarem, M.A., Meshksar, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 185–209. [Google Scholar]

- Vakili, S.S.; Kargari, A.; Sanaeepur, H. Chapter twelve—Cryogenic-membrane gas separation hybrid processes. In Current Trends and Future Developments on (Bio-) Membranes; Basile, A., Favvas, E.P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 349–368. [Google Scholar]

- Lak, S.Z.; Rostami, M.; Rahimpour, M.R. 9—Nitrogen separation from natural gas using absorption and cryogenic processes. In Advances in Natural Gas: Formation, Processing, and Applications. Volume 5: Natural Gas Impurities and Condensate Removal; Rahimpour, M.R., Makarem, M.A., Meshksar, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- He, T.; Si, B.; Gundersen, T.; Lin, W.; Chen, L.; Zhang, K. High ethane content enables efficient CO2 capture from natural gas by cryogenic distillation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 352, 128153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, H.T.; Chen, L.; Gorgojo, P. Simulation study of a hybrid cryogenic and membrane separation system for SF6 recovery from aged gas mixture in electrical power apparatus. In Computer Aided Chemical Engineering; Manenti, F., Reklaitis, G.V., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 53, pp. 703–708. [Google Scholar]

- Suleman, M.S.; Lau, K.K.; Yeong, Y.F. Enhanced gas separation performance of PSF membrane after modification to PSF/PDMS composite membrane in CO2/CH4 separation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 45650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Si, Z.; Yang, S.; Xue, T.; Baeyens, J.; Qin, P. Fast layer-by-layer assembly of PDMS for boosting the gas separation of P84 membranes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 253, 117588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhao, G.; Lau, C.H.; Wang, F.; Fan, S.; Niu, C.; Ren, Z.; Tang, G.; Qin, P.; Liu, Y.; et al. Fabrication of high-flux defect-free hollow fiber membranes derived from a phenolphthalein-based copolyimide for gas separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 331, 125724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roafi, H.; Farrukh, S.; Salahuddin, Z.; Raza, A.; Karim, S.S.; Waheed, H. Fabrication and Permeation Analysis of Polysulfone (PSf) Modified Cellulose Triacetate (CTA) Blend Membranes for CO2 Separation from Methane (CH4). J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 2414–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Peng, D.; Wu, H.; Yang, L.; Wu, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Z. Enhanced carbon dioxide flux by catechol–Zn2+ synergistic manipulation of graphene oxide membranes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 195, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Min, L.; Song, S.; Yang, L.; Ren, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, R.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Z. 2D layered double hydroxide membranes with intrinsic breathing effect toward CO2 for efficient carbon capture. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 598, 117663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, W.; Wei, Y.; Wang, H. Tuning the Stacking Modes of Ultrathin Two-Dimensional Metal–Organic Framework Nanosheet Membranes for Highly Efficient Hydrogen Separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202312995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Peng, M.; Strauss, I.; Mundstock, A.; Meng, H.; Caro, J. High-Flux Vertically Aligned 2D Covalent Organic Framework Membrane with Enhanced Hydrogen Separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 6872–6877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Izquierdo, L.; García-Comas, C.; Dai, S.; Navarro, M.; Tissot, A.; Serre, C.; Téllez, C.; Coronas, J. Ultrasmall Functionalized UiO-66 Nanoparticle/Polymer Pebax 1657 Thin-Film Nanocomposite Membranes for Optimal CO2 Separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 4024–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Yang, P.; Yang, Y.; Huo, S.; Wen, P.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, Y. Encapsulation of hollow polystyrene particles in PDMS membranes for efficient natural gas purification. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Cui, X.; Tosheva, L.; Wang, C.; Chai, Y.; Kang, Z.; Gao, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, H.; et al. Polyethyleneimine NH2-UiO-66 nanofiller-based mixed matrix membranes for natural gas purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, M.; Wan, J.; Duan, J.; Jin, W. Enhancing natural gas purification in mixed matrix membranes: Stepwise MOF filler functionalization through amino grafting and defect engineering. J. Membr. Sci. 2026, 738, 124765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydani, A.; Maghsoudi, H.; Brunetti, A.; Barbieri, G. Silica sol gel assisted defect patching of SSZ-13 zeolite membranes for CO2/CH4 separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 277, 119518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sheng, K.; Wang, Z.; Wu, W.; Yin, B.H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Y. Rational Design of MXene Hollow Fiber Membranes for Gas Separations. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 2710–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Wu, Q.; Qi, D.; Yang, F.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Liu, G.; Zhu, H. Plasma-treated polymer of intrinsic microporosity membranes for enhanced CO2/CH4 separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 376, 134025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Cheng, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Cen, K. Amino-functionalized surface modification of polyacrylonitrile hollow fiber-supported polydimethylsiloxane membranes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 413, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Chu, J.; Zuo, H.; Wang, M.; Wu, C.; Riaz, A.; Liu, L.; Guo, W.; Li, J.; Ma, X. The influence of debromination and TR on the microstructure and properties of CMSMs. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 352, 128167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Fang, C.; Li, Z.; Zhao, G.; Wang, Y.; Song, Z.; Lei, L.; Xu, Z. Oxygen-enriched carbon molecular sieve hollow fiber membrane for efficient CO2 removal from natural gas. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 347, 127611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazazi, K.; Ma, X.; Wang, Y.; Ogieglo, W.; Alhazmi, A.; Han, Y.; Pinnau, I. Ultra-selective carbon molecular sieve membranes for natural gas separations based on a carbon-rich intrinsically microporous polyimide precursor. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 585, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Bai, L.; Weng, Y.; Xu, Z.; Huang, L.; Huang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X. Fine tune gas separation property of intrinsic microporous polyimides and their carbon molecular sieve membranes by gradient bromine substitution/removal. J. Membr. Sci. 2023, 669, 121310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Prasad, B.; Han, Y.; Ho, W.S.W. Polymeric Membranes for H2S and CO2 Removal from Natural Gas for Hydrogen Production: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 5713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Gong, H.; Guo, X.; Chen, L. Feasibility study of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membranes for siloxane removal from biogas. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 135047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, B.; Dilshad, M.R.; Atiq ur Rehman, M.; Akram, M.S.; Kaspereit, M. Highly permeable innovative PDMS coated polyethersulfone membranes embedded with activated carbon for gas separation. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 81, 103406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshkat, S.; Kaliaguine, S.; Rodrigue, D. Enhancing CO2 separation performance of Pebax® MH-1657 with aromatic carboxylic acids. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 212, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeson, L.M.; Burgoyne, W.F.; Langsam, M.; Savoca, A.C.; Tien, C.F. High performance polymers for membrane separation. Polymer 1994, 35, 4970–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasooriya, W. Aging and Long-Term Performance of Elastomers for Utilization in Harsh Environments. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Leoben, Leoben, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, D.A.; Haddad, E.E.; Lin, S.; Sharber, S.A.; Yang, J.; Lawrence, J.A.; Harrigan, D.J.; Wright, P.T.; Liu, Y.; Sundell, B.J. Rational design of melamine-crosslinked poly(ethylene glycol) membranes for sour gas purification. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 709, 123082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favvas, E.P.; Katsaros, F.K.; Papageorgiou, S.K.; Sapalidis, A.A.; Mitropoulos, A.C. A review of the latest development of polyimide based membranes for CO2 separations. React. Funct. Polym. 2017, 120, 104–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.; Galiano, F.; Iulianelli, A.; Basile, A.; Figoli, A. Biopolymers for sustainable membranes in CO2 separation: A review. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 213, 106643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, W.; Koros, W.J. Molecularly Engineered 6FDA-Based Polyimide Membranes for Sour Natural Gas Separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 14877–14883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaidan, R.; Ghanem, B.; Litwiller, E.; Pinnau, I. Physical Aging, Plasticization and Their Effects on Gas Permeation in “Rigid” Polymers of Intrinsic Microporosity. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 6553–6561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadirkhan, F.; Goh, P.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Wan Mustapa, W.N.; Halim, M.H.; Soh, W.K.; Yeo, S.Y. Recent Advances of Polymeric Membranes in Tackling Plasticization and Aging for Practical Industrial CO2/CH4 Applications—A Review. Membranes 2022, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhu, K.; Yang, L.; Ren, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, R.; Khan, N.A.; et al. Plasticization- and aging-resistant membranes with venation-like architecture for efficient carbon capture. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 609, 118215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcheikhhamdon, Y.; Hoorfar, M. Natural gas purification from acid gases using membranes: A review of the history, features, techno-commercial challenges, and process intensification of commercial membranes. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2017, 120, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.W. Crosslinked Hollow Fiber Membranes for Natural Gas Purification and Their Manufacture from Novel Polymers. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar, S.; Smitha, B.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Separation of Carbon Dioxide from Natural Gas Mixtures through Polymeric Membranes—A Review. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2007, 36, 113–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, Z.; Liu, G.; Sun, L.; Xu, R.; Zhong, J. Functionalized GO Membranes for Efficient Separation of Acid Gases from Natural Gas: A Computational Mechanistic Understanding. Membranes 2022, 12, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Xu, C.; Wu, M.; Zhang, X.-F.; Yao, J. Deep eutectic solvent- and nanocellulose-tuned MXene membranes for efficient gas separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 727, 124090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Cai, X.; Yang, X.; Wei, Y.; Ding, L.; Li, L.; Wang, H. Accurate stacking engineering of MOF nanosheets as membranes for precise H2 sieving. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhang, X.; Qu, L.; Fan, T.; Miao, J. Ultrathin two-dimensional membranes by assembling graphene and MXene nanosheets for high-performance precise separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 30121–30168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Song, Y.; Jia, C.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Kipper, M.J.; Huang, L.; Tang, J. A comprehensive review of recent developments and challenges for gas separation membranes based on two-dimensional materials. FlatChem 2024, 43, 100594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, I.A.; Barone, V. Gas processing with intrinsically porous 2D membranes. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 276, 125426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Oh, J.-M.; Azam, M.; Iqbal, J.; Hussain, S.; Miran, W.; Rasool, K. Advances in the Synthesis and Application of Anti-Fouling Membranes Using Two-Dimensional Nanomaterials. Membranes 2021, 11, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, Y.; Wang, H. Dual-module integration of large-area tubular 2D MXene membranes for H2 purification. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 283, 119392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Cheng, L.; Liu, G.; Jin, W. Sub-Nanometer Channels in Two-Dimensional-Material Membranes for Gas Separation. In Porous Membranes; Scrivener Publishing LLC: Beverly, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 313–336. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Goh, K.; Chuah, C.Y.; Bae, T.-H. Mixed-matrix carbon molecular sieve membranes using hierarchical zeolite: A simple approach towards high CO2 permeability enhancements. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 588, 117220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, A.; Muhammad, N.; Gilani, M.A.; Vankelecom, I.F.J.; Khan, A.L. Effect of zeolite surface modification with ionic liquid [APTMS][Ac] on gas separation performance of mixed matrix membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 205, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.Z.; Navarro, M.; Lhotka, M.; Zornoza, B.; Téllez, C.; de Vos, W.M.; Benes, N.E.; Konnertz, N.M.; Visser, T.; Semino, R.; et al. Enhanced gas separation performance of 6FDA-DAM based mixed matrix membranes by incorporating MOF UiO-66 and its derivatives. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 558, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Othman, M.H.D.; Rahman, M.A.; Iftikhar, M.; Ali, Z.; Muqeet, M.; Jaafar, J.; Jilani, A.; Ramli, M.K.N. Enhanced CO2/CH4 separation using amine-modified ZIF-8 mixed matrix membranes. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 334, 130404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, F.; Lo Celso, F.; Duca, D. Construction and characterization of models of hypercrosslinked polystyrene. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2012, 290, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Zheng, X.; Wang, P.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Xiang, Y.; Luo, J.; Chiao, Y.-H.; Pu, S. High-performance membranes based on two-dimensional materials for removing emerging contaminants from water systems: Progress and challenges. Desalination 2025, 594, 118294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Zhao, J.; Wan, J.; Zheng, B.; Chang, I.Y.; Duan, J.; Jin, W. Enhanced natural gas purification by a mixed-matrix membrane with a soft MOF that has a CO2-adapted nanochannel. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 708, 123080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.; He, W.; Ma, J.; Hassan, S.U.; Du, J.; Sun, Q.; Cao, D.; Guan, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J. Membranes with hollow bowl-shaped window for CO2 removal from natural gas. Adv. Membr. 2025, 5, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuto, C.; Zhou, H.; Antonangelo, A.R.; Bezzu, C.G.; Jansen, J.C.; Carta, M.; Fuoco, A. Enhancement of the gas separation performance of mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) with functionalized triptycene hypercrosslinked polymers of intrinsic microporosity (HCP-PIMs). Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 382, 135814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Dai, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Yu, M.; Zheng, W.; Ruan, X.; Xi, Y.; Liang, H.; Liu, H.; et al. Synergistic improvement in gas separation performance of MMMs by porogenic action and strong molecular forces of ZIF-93. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 345, 127214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khulbe, K.C.; Feng, C.; Matsuura, T. The art of surface modification of synthetic polymeric membranes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 115, 855–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, R.A.; Lau, W.J.; Ismail, A.F.; Kartohardjono, S. Recent 10-year development on surface modification of polymeric hollow fiber membranes via surface coating approach for gas separation: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 10083–10118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Yu, J.; Wang, F.; Li, X.; Ni, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Surface-Modified Sodalite (SOD) Zeolite and Preparation of Mixed Matrix Membranes with Polymers of Intrinsic Microporosity (PIM-1) for Efficient Gas Separation. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 8640–8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, L.; Qian, X.; Ranil Wickramasinghe, S. Chemical modification of membrane surface—Overview. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2018, 20, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Hu, H.; Wang, Z.; Cui, Z. DOPA/PEI surface-modified poly-4-methyl-1-pentene membranes and application in membrane aeration biofilm reactor. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 77, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.J.; An, H.; Shin, J.H.; Brunetti, A.; Lee, J.S. A new dip-coating approach for plasticization-resistant polyimide hollow fiber membranes: In situ thermal imidization and cross-linking of polyamic acid. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473, 145378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.H.; Salleh, W.N.W.; Sazali, N.; Ismail, A.F.; Yusof, N.; Aziz, F. Disk supported carbon membrane via spray coating method: Effect of carbonization temperature and atmosphere. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 195, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljumaily, M.M.; Alsaadi, M.A.; Hashim, N.A.; Alsalhy, Q.F.; Das, R.; Mjalli, F.S. Embedded high-hydrophobic CNMs prepared by CVD technique with PVDF-co-HFP membrane for application in water desalination by DCMD. Desalin. Water Treat. 2019, 142, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, X.J.; Show, P.L.; Katsuda, T.; Chen, W.-H.; Chang, J.-S. Surface grafting techniques on the improvement of membrane bioreactor: State-of-the-art advances. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 269, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Yang, Z.; Ma, W.; Chen, X.; Zhao, L.; Liu, G.; Li, N. Facile fabrication of 6FDA-DAM/PGMA blend membranes for advanced gas separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 360, 130895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Fan, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lang, X.; Li, J. Mild ultraviolet detemplation of SAPO-34 zeolite membranes toward pore structure control and highly selective gas separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 318, 123988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Das, R.; Gagrai, M.K.; Sarkar, S. Preparation of carbon molecular sieve membrane derived from phenolic resin over macroporous clay-alumina based support for hydrogen separation. J. Porous Mater. 2016, 23, 1653–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, C.; Weng, Y.; Li, P. Synergistic improvement of CO2/CH4 separation performance of phenolphthalein-based polyimide membranes by thermal decomposition and thermal-oxidative crosslinking. Polymer 2022, 263, 125528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xin, J.; Huo, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Bi, J.; Kang, S.; Dai, Z.; Li, N. Cross-linked PI membranes with simultaneously improved CO2 permeability and plasticization resistance via tunning polymer precursor orientation degree. J. Membr. Sci. 2023, 687, 121994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Sanyal, O.; Koros, W.J. Carbon Molecular Sieve Membrane Preparation by Economical Coating and Pyrolysis of Porous Polymer Hollow Fibers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12149–12153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Wu, J.; Han, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Min, Y. Excellent gas separation performance of hybrid carbon molecular sieve membrane derived from polyimide/10X zeolite for hydrogen purification. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2024, 365, 112889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Hao, L.; Zhang, C.; Qiao, L.; Pang, J.; Wang, H.; Chang, H.; Fan, W.; Fan, L.; Wang, R.; et al. Porous organic cage induced high CO2/CH4 separation efficiency of carbon molecular sieve membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 711, 123231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, D.; Wang, T.; Qiu, J. A simple one-step drop-coating approach on fabrication of supported carbon molecular sieve membranes with high gas separation performance. Asia Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 13, e2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, F.; Cornelius, C.J.; Fan, Y. Carbon molecular sieve membranes derived from crosslinkable polyimides for CO2/CH4 and C2H4/C2H6 separations. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 621, 118785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, G.; Yu, R.; Wang, P.; Ji, Y. High-Performance Carbon Capture with Fluorine-Tailored Carbon Molecular Sieve Membranes. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2420477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, M.; Wei, J.; Ma, Y.; Qin, Z.; Song, J.; Yang, L.; Yao, L.; Jiang, W.; Yi, S.; Li, N.; et al. Next-generation carbon molecule sieve membranes derived from polyimides and polymers of intrinsic microporosity for key energy intensive gas separations and carbon capture. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 19806–19838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koros, W.J.; Fleming, G.K.; Jordan, S.M.; Kim, T.H.; Hoehn, H.H. Polymeric membrane materials for solution-diffusion based permeation separations. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1988, 13, 339–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijmans, J.G.; Baker, R.W. The solution-diffusion model: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 1995, 107, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Gou, M.; Wang, C.; Guo, R. Constructing solubility-diffusion domain in pebax by hybrid-phase MOFs for efficient separation of carbon dioxide and methane. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 346, 112328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Fan, H.; Elimelech, M.; Li, Y. Molecular simulations of organic solvent transport in dense polymer membranes: Solution-diffusion or pore-flow mechanism? J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 708, 123055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarjeh, R.A.B.; Yeo, J.Y.J.; Atassi, Y.; Hosseini, S.S.; Sunarso, J. An Improved Permeation Model for Solution–Diffusion-Based Hollow Fiber Gas Separation Membrane: Implementation and Analysis. Asia Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 20, e3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimund, K.K.; Sujanani, R.; Hernandez, J.M.; Gleason, K.L.; Freeman, B.D. Experimental observation of nonlinear relation between pressure and water flux is consistent with the solution-diffusion model. J. Membr. Sci. 2026, 737, 124756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, M.J.; Javadi, H.; Babaluo, A.A. Effect of Polymer–Zeolite Interactions on the Separation Performance of Modified DD3R Membrane. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e57073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wang, R.; Wu, H.; Wang, F.; Elimelech, M. Molecular simulations reveal gas transport mechanisms in polyamide membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 731, 124056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shovon, S.M.; Akash, F.A.; Monir, M.U.; Ahmed, M.T.; Aziz, A.A. 18—Membrane technology for CO2 removal from CO2-rich natural gas. In Advances in Natural Gas: Formation, Processing, and Applications. Volume 2: Natural Gas Sweetening; Rahimpour, M.R., Makarem, M.A., Meshksar, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 487–508. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, Z.Y.; Chew, T.L.; Zhu, P.W.; Mohamed, A.R.; Chai, S.-P. Conventional processes and membrane technology for carbon dioxide removal from natural gas: A review. J. Nat. Gas Chem. 2012, 21, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Wang, M.; Xia, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Lyu, W.; Liao, B.; Sun, Z.; Wei, B.; Lu, X. Revolutionary insights into CO2 solubility in nanoporous MXenes: Atomic-Scale revelations in CO2/CH4 separation and permeance optimization. Mater. Today Phys. 2025, 57, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narkkun, T.; Kraithong, W.; Ruangdit, S.; Klaysom, C.; Faungnawakij, K.; Itthibenchapong, V. Pebax/Modified Cellulose Nanofiber Composite Membranes for Highly Enhanced CO2/CH4 Separation. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 45428–45437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarzadeh, E.; Shockravi, A.; Vatanpour, V. High performance compatible thiazole-based polymeric blend cellulose acetate membrane as selective CO2 absorbent and molecular sieve. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 252, 117215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Z.; Guo, R.; Wu, H.; Cao, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, B. Synergistic effect of combining carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide in mixed matrix membranes for efficient CO2 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 479, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhou, R.; Yogo, K.; Kita, H. Preparation of CHA zeolite (chabazite) crystals and membranes without organic structural directing agents for CO2 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 573, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, L.; Wu, J.; Han, Z.; Chen, Z.; Cui, T.; Zhang, S.; Ma, X.; et al. Remarkably enhanced molecular sieving effect of carbon molecular sieve membrane by enhancing the concentration of thermally rearranged precursors. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 341, 126945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Jia, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, D. Ultrathin mixed matrix membranes containing two-dimensional metal-organic framework nanosheets for efficient CO2/CH4 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 539, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Li, H.; Chen, Z.; Lin, J.; Liu, Y. Enhancing gas separation performance of polyimide with Tröger’s bases: Unveiling the impact on polymer and carbon molecular sieve membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 336, 126286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Amal, R.S.; Maiti, P.K. Unifying mixed gas adsorption in molecular sieve membranes and MOFs using machine learning. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, W.; Xu, S.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, M.; Qu, Y.; Geng, C.; Jia, H.; Wang, X. Convenient preparation of inexpensive sandwich-type poly(vinylidene fluoride)/molecular sieve/ethyl cellulose mixed matrix membranes and their effective pre-exploration for the selective separation of CO2 in large-scale industrial utilization. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Wang, S.; Shen, T.; Gai, F.; Ma, Z.; Liu, G.; Li, J.; Wang, H. High-performance carbon molecular sieve membrane derived from PEK-N polymer for CO2 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 713, 123337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Li, L.; Xu, R.; Lu, Y.; Song, J.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, T.; Jian, X. Precursor-chemistry engineering toward ultrapermeable carbon molecular sieve membrane for CO2 capture. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 102, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fan, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, L.; Guan, D.; Ma, C.; Li, N. Ultra-selective molecular-sieving gas separation membranes enabled by multi-covalent-crosslinking of microporous polymer blends. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]