Abstract

No vaccine has been more effective in reducing disease burden, especially in preventing child deaths, than measles-containing vaccine. The return on investment makes measles-containing vaccine one of the most cost-effective public health measures available. Exhaustive reviews of biological, technical, economic and programmatic evidence have concluded that measles can and should be eradicated, and by including rubella antigen in measles-containing vaccine, congenital rubella syndrome will also be eradicated. All World Health Organisation Regions have pledged to achieve measles elimination. Unfortunately, not all countries and global partners have demonstrated an appropriate commitment to these laudable public health goals, and the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on coverage rates has been profound. Unsurprisingly, large disruptive outbreaks are already occurring in many countries with a global epidemic curve ominously similar to that of 2018/2019 emerging. The Immunization Agenda 2030 will fail dismally unless measles and rubella eradication efforts are accelerated. Over half of all member states have been verified to have eliminated rubella and endemic rubella transmission has not been re-established in any country to date. In 2023, 84 countries and areas were verified to have sustained elimination of measles. However, without a global target, this success will be difficult to sustain. Now is the time for a global eradication goal and commitment by the World Health Assembly. Having a galvanising goal, with a shared call for action, will demand adequate resourcing from every country government and global partners. Greater coordination across countries and regions will be necessary. Measles, rubella and congenital rubella syndrome eradication should not remain just a technically feasible possibility but rather be completed to ensure that future generations of children do not live under the shadow of preventable childhood death and lifelong disability.

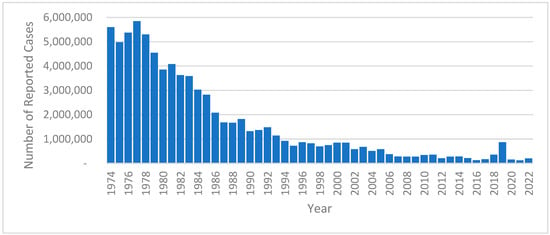

Fifty years after the Expanded Programme on Immunization was launched in 1974, the extraordinary benefits of life-saving vaccines are being enjoyed by millions of children around the world [1]. No vaccine has been more effective in reducing the disease burden (Figure 1), especially in preventing child deaths, than the measles-containing vaccine (MCV). Between 2000 and 2022, the MCV prevented an estimated 57 million deaths globally [2]. Other than perhaps safe water and sanitation and breastfeeding, no other global health initiative can claim such a remarkable impact in averting deaths. Modeling indicates that measles vaccination will prevent 37% of deaths due to vaccination against 14 key pathogens between 2021 and 2030, with a remarkable 18.8 million lives saved in the current decade alone [3]. In addition to the immediate threats posed by measles disease, the subsequent immunosuppression among children who have been infected may last for weeks to months, leading to increased vulnerability to an array of other viral and bacterial infections [4]. Up to half of all infectious disease-related childhood deaths within the first few years of natural measles infection may be explained by this phenomenon. The return on investment makes the MCV one of the most cost-effective public health measures available. The analysis of economic data from 73 low- and middle-income countries on the costs for delivering the measles vaccine suggests that for every USD 1 invested, USD 58 were saved in future costs from 2001 to 2020 [5].

Figure 1.

Measles reported cases worldwide, 1974–2022. Source: World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory. Measles—number of reported cases (https://www.who.int/), accessed on 29 April 2024.

Congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) is associated with considerable disability, including heart defects, cataracts, hearing loss, and developmental delays, and can occur when a woman is infected with rubella in early pregnancy. The CRS burden is typically low in countries where coverage with rubella-containing vaccines (RCVs) is high and disappears when endemic rubella transmission ceases. Estimates suggest that between 1996 and 2010, the number of children born with CRS decreased from 119,000 to just over 100,000 as the vaccination coverage slowly increased; this is still an intolerable burden of disability given the lower population RCV coverage required to drive this virus to extinction [6]. By including the rubella antigen with the MCV to produce an MR-containing vaccine (MRCV), the elimination of measles will result in the elimination of CRS.

‘Measles can and should be eradicated’ was the conclusion of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) Working Group on Immunization to the WHO in 2010 following an exhaustive review of biological, technical, economic, and programmatic evidence [7]. By 2010, all WHO regions had pledged to achieve measles elimination, and this was reflected in the Global Vaccine Action Plan, 2011–2020 (GVAP), implying a global measles eradication agenda by default [8]. The GVAP endorsed by all member states simultaneously committed every region to achieving rubella and CRS elimination. Rubella elimination achievement was verified in the region of the Americas in 2015 and measles elimination in 2016.

Unfortunately, not all countries and global partners have demonstrated an appropriate commitment to these laudable public health goals. The devastating global measles resurgence in 2018/2019 bore testament to a failure to achieve the necessary two-dose MCV coverage required to protect all children. Applying the current criteria, the massive and disruptive measles outbreaks in 2019 in many countries met the criteria for the declaration of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). The World Health Organization (WHO) did not declare it for measles as another PHEIC, COVID-19’s emergence, distracted attention from the measles catastrophe [9]. In contrast with COVID-19, the measles disease burden particularly affects children living in developing countries and so it did not receive the attention and resources devoted to COVID-19, which affected all countries and adult populations. The closure of country borders during the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with the dramatic decrease in international travel and wide-scale non-pharmaceutical public health measures, significantly obstructed the importation and transmission of measles and rubella viruses and provided an opportunity for accelerated progress towards measles and rubella elimination. However, this would have required concerted and coordinated efforts to close the immunity gaps resulting from the detrimental pandemic impacts on routine immunization program performance and postponed campaigns as a result of COVID-19 [10].

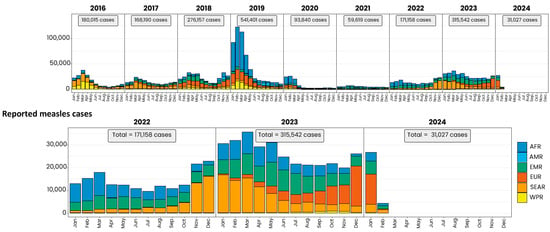

Sadly, only 81% of children born in 2021 received MCV1, the lowest coverage since 2008, leaving 25 million children born that year vulnerable to measles [2]. In 2022, the MCV1 coverage was at 83%, 3% below the pre-pandemic 2019 level of 86%, which had proved inadequate to prevent the epidemic surge at that time. Unsurprisingly, large disruptive outbreaks are already occurring in many countries, with a global epidemic curve ominously similar to that of 2018 and early 2019 (Figure 2), but, additionally, with the knowledge that there is a greater susceptible pool of measles-naïve individuals—both unvaccinated children born since the COVID-19 pandemic and cohorts of older children and young adults who do not enjoy immunity because of historically inadequate routine immunization coverage or sub-optimal campaign performance. It may well be too late to prevent the next measles pandemic.

Figure 2.

Measles reported cases by WHO region, 2016–2024. Source: World Health Organization, used with permission. Based on data received 2024-02—Data Source: IVB Database. These are surveillance data; hence, for the last month(s), the data may be incomplete. Note: The lower panel is an expanded high-resolution representation of years 2022–2024 in the upper panel. AFR = African Region; AMR = Region of the Americas; EMR = Eastern Mediterranean Region; EUR = European Region; SEAR = Southeast Asian Region; WPR = Western Pacific Region.

The Immunisation Agenda 2030 (IA2030) rightly recognizes measles as a tracer of the strength of immunization programs, with strategic priority 3 noting that measles cases and outbreaks should serve to identify weaknesses in immunization programs and guide programmatic planning in identifying and addressing these weaknesses [11]. In reality, IA2030 will inevitably fail unless the measles and rubella eradication efforts are accelerated, including a failure to achieve impact goals 1.1 (deaths averted), 1.2 (endorsed elimination targets), 1.3 (declining trend in number of large or disruptive outbreaks), 2.1 (50% reduction in zero dose children), and 3.1 (90% global coverage with MCV2) [12]. The central tenet of IA2030 is to leave no one behind. As such, the measles virus is the ultimate test of this equity obligation.

Against this bleak backdrop, there are some impressive success stories. Over half of all member states have been verified to have eliminated rubella, and endemic rubella transmission has not been re-established in any country to date (Table 1). This success bodes well for the achievement of global rubella and CRS elimination in the foreseeable future [13], and this progress towards rubella elimination should serve as a catalyst towards measles elimination.

Table 1.

Global measles and rubella elimination verification status by country and territory, 2011–2022.

Unfortunately, progress towards global measles elimination has not been homogenous. Only one region has achieved measles elimination, the Americas. This success story has recently been threatened with the loss of ‘measles-free’ status in Brazil and Venezuela due to a sustained, import-related measles outbreak lasting for longer than 12 months. In the European and Western Pacific Regions, 11 countries were verified to have eliminated measles, but, unfortunately, endemic transmission was then re-established (Table 1).

Without a global target, success is difficult to sustain. The other countries of the Region of the Americas have done so, but authorities recognize the fragility of elimination when the virus circulates elsewhere. To this end, there is great promise appearing on the horizon in each region. For example, in the Americas, Brazil and Venezuela appear to have interrupted measles transmission and are likely to apply for reverification. In the Western Pacific, China continues to make phenomenal steady progress towards measles elimination, and the Pacific Island Countries and Areas [14] and Mongolia are targeting 2025 to apply for verification. In the Eastern Mediterranean region, four countries, including Iran and Egypt, have documented and sustained elimination, and five additional countries are close to being verified.

What are the keys to success in this task? Given that each region has committed to measles and rubella elimination, now is the time for a global eradication goal and commitment by the World Health Assembly.

Having a galvanizing goal, with a shared call for action, will demand adequate resourcing from every country government and global partner. However, in addition to health ministers, we need finance ministers appreciating the return on investment. With many countries delegating health responsibility and funding to provincial or local governments, decentralized governments must embrace the goal as well. Such efforts will attract more local engagement and ownership. By proactively looking for opportunities, measles and rubella elimination will enhance national and local health capacity development and the response to future pandemic threats [15].

Champions are needed as advocates in all communities—this should not be too onerous as every community loves its children. New visionary partners are also needed—the world has become too dependent on single major players. Any country not using a rubella-containing vaccine—currently, there are 19—should immediately do so. No scientific arguments justifying the withholding of the RCV exist that have been proven to outweigh the benefits of CRS elimination.

Greater coordination across countries and regions will be necessary. The approach piloted in the Americas remains valid. Coordinated campaigns and surveillance efforts will foster collaboration between countries and achieve more than individual countries working in isolation could ever achieve alone.

Highly effective measles- and rubella-containing vaccines have shown what is possible. With microarray vaccination patches now in clinical trials, this simplified delivery of effective vaccines may guarantee that outreach to every community and child becomes a practical reality [16].

We have no choice—there is a moral imperative to now commit to and achieve measles and rubella eradication [17]. How long will the global community tolerate the ongoing disease burden and preventable deaths due to measles? The rule of rescue demands that if we have effective tools, we should make every effort to save lives. Measles, rubella, and CRS eradication should not remain merely a technically feasible possibility but rather be completed to ensure that future generations of children do not live under the shadow of preventable childhood death and lifelong disability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.N.D., J.K.A., S.T., D.G., M.K. and N.T.; writing—original draft preparation, D.N.D., writing—review and editing, D.N.D., J.K.A., S.T., D.G., M.K. and N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Mahoney F, Deputy Chairperson Regional Measles and Rubella Elimination Verification Commission, European Pacific Region, for his contribution to the conception and review. O’Connor P, Department of Immunization, Vaccines, and Biologicals (IVB). World Health Organization—Geneva, Switzerland, for assisting with the construction and refinement of Table 1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Essential Programme on Immunisation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Minta, A.A.; Ferrari, M.; Antoni, S.; Portnoy, A.; Sbarra, A.; Lambert, B.; Hatcher, C.; Hsu, C.H.; Ho, L.L.; Steulet, C.; et al. Progress toward regional measles elimination—Worldwide, 2000–2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 1262–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, A.; Msemburi, W.; Sim, S.Y.; Gaythorpe, K.A.; Lambach, P.; Lindstrand, A.; Hutubessy, R. Modeling the impact of vaccination for the immunization Agenda 2030: Deaths averted due to vaccination against 14 pathogens in 194 countries from 2021 to 2030. Vaccine 2023, in press. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hübschen, J.M.; Gouandjika-Vasilache, I.; Dina, J. Measles. Lancet 2022, 399, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozawa, S.; Clark, S.; Portnoy, A.; Grewal, S.; Stack, M.L.; Sinha, A.; Mirelman, A.; Franklin, H.; Friberg, I.K.; Tam, Y.; et al. Estimated economic impact of vaccinations in 73 low- and middle-income countries, 2001–2020. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 95, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vynnycky, E.; Knapp, J.K.; Papadopoulos, T.; Cutts, F.T.; Hachiya, M.; Miyano, S.; Reef, S.E. Estimates of the global burden of Congenital Rubella Syndrome, 1996–2019. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 137, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization, November 2010. Summary, conclusions and recommendations. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2011, 86, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Vaccine Action Plan, 2011–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Durrheim, D.N.; Crowcroft, N.S.; Blumberg, L.H. Is the global measles resurgence a “public health emergency of international concern”? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 83, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrheim, D.N.; Andrus, J.K.; Tabassum, S.; Bashour, H.; Githanga, D.; Pfaff, G. A dangerous measles future looms beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 360–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Immunization Agenda 2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/immunization-agenda-2030-a-global-strategy-to-leave-no-one-behind (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- World Health Organization. IA 2030 scorecard–global. In IA2030 Scorecard for Immunization Agenda 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Reef, S.E.; Icenogle, J.P.; Plotkin, S.A. The path to eradication of rubella. Vaccine 2023, 41, 7525–7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrheim, D.N.; Tuibeqa, I.V.; Aho, G.S.; Grangeon, J.P.; Ogaoga, D.; Wattiaux, A.; Mariano, K.M.; Evans, R.; Hossain, S.; Aslam, S.K. Pacific Island Countries demonstrate the sustained success of a coordinated measles mass vaccination campaign. Lancet Reg. Health–West. Pac. 2024, 42, 100998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrus, J.K.; Cochi, S.L.; Cooper, L.Z.; Klein, J. Combining global elimination of measles and rubella with strengthening of health systems in developing countries. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hasso-Agopsowicz, M.; Crowcroft, N.; Biellik, R.; Gregory, C.J.; Menozzi-Arnaud, M.; Amorij, J.P.; Gilbert, P.A.; Earle, K.; Frivold, C.; Jarrahian, C.; et al. Accelerating the Development of Measles and Rubella Microarray Patches to Eliminate Measles and Rubella: Recent Progress, Remaining Challenges. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 809675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrheim, D.N.; Andrus, J.K. The ethical case for global measles eradication-justice and the Rule of Rescue. Int. Health 2020, 12, 375–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).