Abstract

WHO identifies vaccine hesitancy (VH) as one of the ten threats to global health. The authors bring to the international scientific community an Italian episode that offers the opportunity to renew the discussion on the extent of the VH matter. The purpose of this systematic review is to analyze the factors determining vaccine hesitancy in the Italian population, to understand its roots, and suggest potential strategies to mitigate it. A systematic review of the literature according to the PRISMA guidelines was carried out using the SCOPUS and Medline (via PubMed) databases, using the following strategy: (COVID-19 vaccines) AND (vaccination hesitancy) AND (Italy). After the selection process, 36 articles were included in this systematic review. The most frequently detected factors associated with VH in the Italian population can be grouped as vaccine-related factors, socio-cultural factors, and demographic factors. Currently, we are facing a gap between the population and science, governments, and institutions. To heal this breach, it is necessary to strengthen the trust of the population through the implementation of health communication and public education strategies, while scientific literacy must continue to support families and individuals in discerning evidence from opinions to recognize the real risks and balance them with the benefits.

1. Introduction

In the topical background characterized by the spread of the COVID-19 disease, vaccines represent the most effective tool in containing the pandemic.

According to official data from the World Health Organization (WHO), to date, over thirteen billion doses have been administered worldwide [] and, although the safety of immunization has been widely demonstrated, there are still many people sceptic about vaccination due to misconceptions or distrust of the scientific evidence [].

WHO defines vaccine hesitancy as “the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination” and identify it as one of the ten threats to global health []. This phenomenon depends on several factors, including socio-demographic, cultural, and religious beliefs [,,,,], and is often fueled by political debates that sometimes provide unreliable information. An additional role is played by the influences of anti-vaccination movements and social media, which feed the so-called infodemic phenomenon, meaning the dissemination of false or misleading information not based on scientific evidence [,,,,]. Frequently, the eventuality of vaccination-related side effects is overemphasized, leading to an attitude of suspicion and rejection from the population. This setting constitutes a danger both to public health and the individual in the pandemic era, sometimes resulting in significant consequences in therapeutic choices not always directly related to vaccination itself.

The authors want to bring to the international scientific community the Italian case of a married couple who asked to use the blood of people unvaccinated against the coronavirus for possible transfusions during the life-saving heart surgery of their two-year-old child, postponing the operation. The health workers, believing that they could no longer delay the surgery, challenged Article 3 of Law 219 of 2017, which provides that if the legal representatives of the minor refuse the treatment deemed appropriate and necessary by the doctor, the decision is left to the tutelary judge. The dissent of the couple derived from the assumption that the COVID-19 vaccine involves a high incidence of cardiovascular complications and can be inoculated through transfused blood. However, after analyzing the reasons given by the spouses, the tutelary judge emphasized in agreement with the scientific community that blood transfusion does not involve any risk for patients who receive blood from vaccinated subjects. Therefore, the judge suspended the parental authority of the couple and ordered that the child undergo cardiac surgery, with possible blood transfusions chosen by the hospital. The case is peculiar as it highlights a new aspect of the “dangerousness” of the distrust of the vaccine against COVID-19, whose perceived risk, based on non-scientifically founded beliefs, is such as to lead to the decision to delay a life-saving intervention.

The episode described above offers the opportunity to renew the discussion on the extent of the “vaccine hesitancy” matter. VH has a complex nature and varies according to time and country [,]. Therefore, although numerous studies investigating this phenomenon worldwide have been published in the literature, they may have the limitation of not investigating the determinants in relation to the context of a specific region. The purpose of this systematic review is to analyze the factors determining vaccine hesitancy in the Italian population, to understand its roots, and suggest potential strategies to mitigate it.

2. Materials and Methods

On 9 November 2022, a systematic review of the literature according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [] was carried out using the SCOPUS and Medline (via PubMed) databases, using the following strategy:

- −

- Scopus search string: (COVID-19 vaccines) AND (vaccination hesitancy) AND (Italy);

the filters applied were Document type: Article, Short Survey; Language: English.

- −

- Pubmed search string: ((“COVID-19 Vaccines”[Mesh]) AND “Vaccination Hesitancy”[Mesh]) AND “Italy”[Mesh];

The filter applied was Language: English.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were: human studies; studies among healthcare workers, pregnant women, parents, students, and people affected by pathologies; aim of the study: to evaluate COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the Italian population. The exclusion criteria were: article not aimed at evaluating COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the Italian population; article not in English; abstract; case report; editorial; review; letter; note; conference paper.

2.2. Quality Assessment and Critical Appraisal

M.F. and G.B. evaluated the entire text of the articles, independently. The articles in which there was disagreement were discussed with the senior investigator, P.F., for the final decision.

2.3. Risk of Bias

The main risk was linked to the keyword selected for the search strings. Therefore, the Kappa interobserver variability coefficient showed “almost perfect agreement” (0.89) [].

2.4. Characteristics of Eligible Studies

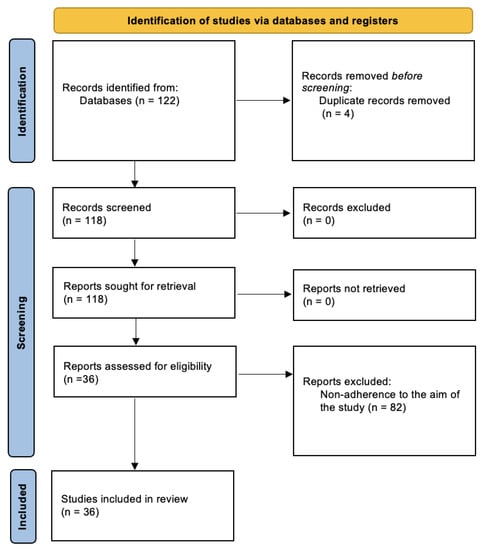

A total of 122 articles were identified. Four duplicate articles were removed, and 82 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria. After the selection process, 36 articles were included in the present systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram for this systematic review.

3. Results

The analysis of the results, summarized in Table 1, shows that the overall period covered by the included studies ranges from December 2020 to May 2022.

Table 1.

Summary of the studies included in the present systematic review.

Of these, four studies were performed before the vaccination campaign in Italy (December 2020), 29 studies were conducted after that date, and three studies started before and ended after the vaccination campaign began in Italy. In relation to the type of population under study, the articles included in this review can be divided as follows: 10 studies investigated the phenomenon of vaccination hesitancy in pregnant women or parents/caregivers; 10 studies concern medical students or health professionals; six studies consider individuals affected by pathologies; and 10 studies analyze the problem in the general population (including non-healthcare students).

The most frequently detected factors associated with VH in the Italian population are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Most frequently encountered factors predisposing vaccine hesitancy in the Italian population.

These factors can be grouped into three main categories: vaccine-related factors (e.g., doubts about the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, concern about adverse reactions, awareness of the possibility of contracting the infection, adequacy of information regarding the topic); socio-cultural factors (e.g., low level of education, political orientation, social support, distrust in authorities); and demographic factors (gender, age).

3.1. Vaccine-Related Factors

The most common predisposing factor for VH found in the included studies and related to vaccination is the fear of developing adverse reactions [,,,,,,,,,,,]. Another significant aspect is the distrust or doubts about vaccination against COVID-19 and its efficacy [,,,,,,,,,,]. As easily expected, the attitude of refusal towards vaccinations or the adoption of poorly protective behaviours constitutes a further preponderant element predisposing to VH against COVID-19 [,,,,,,,,,,]. Another predisposing element is the lack of awareness of contracting the infection [,,,,,,,,]. Furthermore, four studies found that knowing people who have contracted the COVID-19 disease affects the decision to undergo the vaccination [,,,]. Finally, the preference for natural immunity or having contracted COVID-19 before vaccination are both conditioning factors for the decision to undergo the vaccine [,,,].

3.2. Socio-Cultural Factors

Among the sociocultural factors, the one most frequently found associated with VH is a low level of education [,,,,,,,,,,]. Information obtained through mass media or the internet, scarcity of information, and information obtained from non-medical people are associated with VH [,,,,,]. Five studies identify distrust of authorities [,,,,], and two studies identify a conspirative mentality [,] as elements implied in the decision to vaccinate against COVID-19. One study found that VH is widespread in individuals with right-wing or center-right political orientation [], while another survey shows that the phenomenon is associated with poor social support from parents or family members [].

3.3. Demographic Factors

Three studies considered age as a predisposing factor for VH. Tomietto et al. [] show that those belonging to the so-called “generation X” (born between 1961 and 1980) [] are more hesitant. Moscardino et al. [], on the other hand, found that reluctant people fall more into the 30–40 age group. According to the study by Zona et al. [], individuals younger than 40 are the most unwilling to vaccinate against COVID-19. In addition, one study reveals that the inhabitants of northern Italy and those who are unemployed are more hesitant towards this vaccine []. Five studies show that female gender is an additional determinant for hesitancy [,,,,].

Analyzing the phenomenon in relation to the different categories of individuals taken into consideration in this review, it emerges that, as regards the population of “parents”, including pregnant women, the factor most frequently found as predisposing to vaccination hesitancy is a low level of education, encountered in 7 out of 10 studies. The fear of developing adverse reactions to vaccination is the factor most highlighted in the category of “health professionals and medical students” and in the population of people affected by pathologies, although there is no apparent prevalence of this element compared to the other determinants found in these individuals. On the other hand, studies conducted on the general population show that the main predisposing factors to vaccine hesitancy consist of distrust of the authorities and an attitude of general refusal towards vaccinations.

4. Discussion

Vaccine hesitancy is an ever-current topic and understanding its determinants may help both to develop strategies to enhance immunization acceptance and learn lessons from the pandemic to be better prepared for future public health crises. The data updated to 2 December 2022 show that in Italy, 6.79 million people over the age of 5 have yet to receive even one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, of which 6.10 million are currently eligible for vaccination []. This review analyzes the factors predisposing to vaccine hesitancy in the Italian population and represents, to the best of our knowledge, the first systematic review providing a global vision of this issue concerning this country.

The vaccination campaign in Italy was accompanied by the slogan “Italy is reborn with a flower” and by the symbol of the primrose as a sign of rebirth and hope after the high rate of deaths and the restrictive measures of the lockdown. Various advertisements were broadcast on television to raise public awareness of the importance of vaccination as a means of protection for the individual and for the community, focusing on the emotional aspect of the issue (such as the protection of family members) rather than on the safety of the vaccine [].

Nevertheless, the website of the Ministry of Health [], which is updated regularly, provides information about the type of vaccines authorized in Italy, their safety (there is a link to the website of the Italian Medicines Agency, which reports the results of the pharmacovigilance activity using interactive graphs), the possibility of vaccinating particular age groups or immunosuppressed individuals, and the possibility of receiving anti-COVID 19 vaccination at the same time as other vaccinations, as well as a dashboard that collects data and statistics relating to the administration of vaccines throughout the national territory. In addition, there is a section of the site dedicated to the most frequent fake news, with explanations verified by experts from the Ministry of Health and/or the Italian National Institute of Health and is based on scientific evidence, regulations, and national and international documentation [].

The Italian Pediatric Society conducted a pilot project and enrolled pediatricians as “influencers” to share on their own Facebook profile information from the official page of the scientific society to contrast fake news [].

However, although for months the media mainly hosted immunologists and medical or scientific experts, the opportunity to take part in the debate was given also to influencers and commentators, resulting in the dissemination of antiscientific opinions, which certainly influenced the diffusion of VH.

Among the determinants of VH most frequently detected by the present study are those closely related to the vaccine, including fear of developing adverse reactions and safety concerns or low confidence in vaccination against COVID-19.

These results are consistent with a survey published in 2016 revealing a high mistrust of the Italian population toward vaccination safety [].

Indeed, the speed of development and the scarcity of information on vaccines has influenced the reticence of the population and, at the beginning of the vaccination campaign, there was little information about the side effects and safety of the vaccine. Furthermore, the Italian authorities suspended the administration of the Vaxzevria vaccine in March 2021 for a few days after reports of rare side effects related to coagulation disorders. Arguably, this suspension fueled fears of developing adverse vaccine events and, consequently, contributed to the phenomenon of vaccine hesitancy. These findings could be related to another result of the present review, which identifies among the predisposing factors for reluctance the preference to acquire natural immunity rather than through vaccination.

Healthcare professionals and medical students are mainly more concerned about adverse effects than other groups. This finding agrees with previously published studies [,,] and could be related to the refusal of the small number of health professionals to undergo vaccination, which has led the Italian government to issue the decree-law of 1 April 2021, n. 44, establishing COVID-19 mandatory vaccination for Italian healthcare workers until the complete realization of the vaccination plan. Transparent and personalized education of HCWs about the frequency and type of adverse effects related to COVID-19 vaccination could represent a valuable approach to overcoming the fear of this eventuality. Healthcare professionals represent one of the main vehicles of scientifically correct information about vaccinations. Vaccine information obtained from non-healthcare personnel is another study finding influencing vaccine hesitancy. This data is relevant considering that the exponential role of the internet and the mass media in disseminating information has led to the generation of the phenomenon known as “infodemic”. The dissemination of inaccurate information, if not contrasted, can influence the decision-making process of individuals and triggers a self-feeding phenomenon, as people who encounter fake information on social media can, in turn, share it [].

Among the socio-cultural factors, a low level of education strongly influences the choice to carry out the vaccination against COVID-19, especially among parents. From this point of view, pediatricians need to start orientation courses for parents and pregnant women through adequate counseling and personalized communication strategies to overcome cultural barriers, dialoguing, and providing arguments based on scientific evidence. This need becomes even more contemporary in the light of the recent circular from the Italian Ministry of Health, issued on 9 December 2022, which extends the indication for the use of the Comirnaty (BioNTech/Pfizer) vaccine for the age group between 6 months and 4 years [].

Therefore, transparent and homogeneous information from HCWs and institutional figures is needed to support preventive behaviours and change personal risk perception.

Regarding political orientation, right-wing beliefs influence the predisposition to vaccination, in agreement with Cadeddu et al. [], who investigated the confidence of the Italian population in vaccines. This data, however, disagrees with the findings of Engin et al., according to which political conservatism does not impact vaccine beliefs [].

Among the demographic factors, there seems to be no uniformity between the evidence found in relation to age, while the female gender appears to be a predisposing factor to hesitancy, according to data published by other studies [].

5. Conclusions

Currently, we are facing a gap between the population and science, governments, and institutions []. This phenomenon involves both the general population and healthcare professionals, to the point that Italy was the first European country to make vaccination mandatory for this professional category [].

To heal this breach, it is necessary to strengthen the trust of the population through the implementation of health communication and public education strategies, which cannot prescind from determinants such as competence, correctness, sincerity, faith, consistency, and objectivity []. On the other hand, scientific literacy must continue to support families and individuals in discerning evidence from opinions to recognize the real risks and balance them with the benefits [,].

Clear communication is the main tool to encourage vaccinations. Since the internet is one of the main sources of interaction, it should be remembered that a lot of information on the web is disseminated by users not having knowledge of the disease or vaccine and promoting fake news circulation.

To counter the infodemic phenomenon, it could be useful for health authorities to implement public platforms (so-called fact-checking) where users can expose and verify doubts about the truthfulness of information. Furthermore, since a low cultural level has proved to be one of the factors predisposing to VH, the information provided by institutional sites must be easy to understand. An Italian study [] found that Italian regions have websites providing information on COVID-19 vaccines using terminology that is too complex for users with a low level of education to understand. Consequently, the simplification of the texts would allow these population groups to access material about the safety and reliability of vaccines and encourage their propensity to vaccinate.

6. Limitations

The studies included in this study are surveys, representing a snapshot of the vaccine hesitancy position in a short time. Furthermore, the results of the studies conducted before and after the start of the vaccination campaign were considered together. Consequently, the incidence of the beginning of the vaccination campaign on the perception of the Italian population was not specifically evaluated, which could be a bias in the data interpretation. Additionally, the surveys used questionnaires with items not always overlapping. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution, as the representativeness of the study is not fully guaranteed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.; methodology, R.L.R.; literature review: G.V. and N.D.F.; quality assessment and critical appraisal, A.D.F. and G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F. and G.B.; writing—review and editing, R.L.R. and M.A.; supervision, P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval is not applicable for this systematic review since the data are from previously published studies in which informed consent was obtained by the primary investigators.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting this systematic review are available in the reference section.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Zimmerman, T.; Shiroma, K.; Fleischmann, K.R.; Xie, B.; Jia, C.; Verma, N.; Lee, M.K. Misinformation and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine 2022, 41, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Hwang, S.E.; Kim, W.H.; Heo, J. Socio-demographic, psychological, and experiential predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Korea, October-December 2020. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwebelem, O.C.; Onyeaka, H.; Yunusa, I.; Miri, T.; Onwuneme, Y.M.; Eunice, A.T.; Anyogu, A.; Obi, B.; Carol, N.A. Do we trust the government? Attributes of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance in Nigeria. AIMS Med. Sci. 2022, 9, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, M.; De Cola, M.; MacDonald, N.E.; Dumolard, L.; Duclos, P. Assessments of global drivers of vaccine hesitancy in 2014-Looking beyond safety concerns. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L.P.; Wong, P.F.; Megat Hashim, M.M.A.A.; Han, L.; Lin, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Zimet, G.D. Multidimensional social and cultural norms influencing HPV vaccine hesitancy in Asia. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugliese-Garcia, M.; Heyerdahl, L.W.; Mwamba, C.; Nkwemu, S.; Chilengi, R.; Demolis, R.; Guillermet, E.; Sharma, A. Factors influencing vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in three informal settlements in Lusaka, Zambia. Vaccine 2018, 36, 5617–5624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muric, G.; Wu, Y.; Ferrara, E. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy on Social Media: Building a Public Twitter Data Set of Antivaccine Content, Vaccine Misinformation, and Conspiracies. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2021, 7, e30642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Infectious Diseases. The COVID-19 infodemic. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Regaiey, K.A.; Alshamry, W.S.; Alqarni, R.A.; Albarrak, M.K.; Alghoraiby, R.M.; Alkadi, D.Y.; Alhakeem, L.R.; Bashir, S.; Iqbal, M. Influence of social media on parents’ attitudes towards vaccine administration. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18, 1872340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafuri, S.; Gallone, M.S.; Cappelli, M.G.; Martinelli, D.; Prato, R.; Germinario, C. Addressing the anti-vaccination movement and the role of HCWs. Vaccine 2014, 32, 4860–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarocostas, J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, D.A.; Dudley, M.Z.; Glanz, J.M.; Omer, S.B. Vaccine Hesitancy: Causes, Consequences, and a Call to Action. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, S391–S398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E.; Eskola, J.; Liang, X.; Chaudhuri, M.; Dube, E.; Gellin, B.; Goldstein, S.; Larson, H.; Manzo, M.L.; Reingold, A.; et al. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, A.J.; Garrett, J.M. Understanding interobserver agreement: The kappa statistic. Fam. Med. 2005, 37, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- del Giudice, G.M.; Folcarelli, L.; Napoli, A.; Corea, F.; Angelillo, I.F. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy and willingness among pregnant women in Italy. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 995382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomietto, M.; Simonetti, V.; Comparcini, D.; Stefanizzi, P.; Cicolini, G. A large cross-sectional survey of COVID-19 vaccination willingness amongst healthcare students and professionals: Reveals generational patterns. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 2894–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peruch, M.; Toscani, P.; Grassi, N.; Zamagni, G.; Monasta, L.; Radaelli, D.; Livieri, T.; Manfredi, A.; D’Errico, S. Did Italy Really Need Compulsory Vaccination against COVID-19 for Healthcare Workers? Results of a Survey in a Centre for Maternal and Child Health. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechini, A.; Vannacci, A.; Crescioli, G.; Lombardi, N.; Del Riccio, M.; Albora, G.; Shtylla, J.; Masoni, M.; Guelfi, M.R.; Bonanni, P.; et al. Attitudes and Perceptions of University Students in Healthcare Settings towards Vaccines and Vaccinations Strategies during the COVID-19 Pandemic Period in Italy. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffetti, E.; Mondino, E.; Di Baldassarre, G. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Sweden and Italy: The role of trust in authorities. Scand. J. Public Health 2022, 50, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Riccio, M.; Bechini, A.; Buscemi, P.; Bonanni, P.; Boccalini, S. Reasons for the Intention to Refuse COVID-19 Vaccination and Their Association with Preferred Sources of Information in a Nationwide, Population-Based Sample in Italy, before COVID-19 Vaccines Roll Out. Vaccines 2022, 10, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarese, G.; Carpinelli, L.; Chiara, A.D.; Giordano, C.; Perillo, M.; Fornino, D.; De Caro, F.; Capunzo, M.; Moccia, G. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Campaign: Risk Perception, Emotional States, and Vaccine Hesitancy in a Sample of Adolescents’ Vaccinated Parents in Southern Italy. Vaccines 2022, 10, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Moro, G.; Cugudda, E.; Bert, F.; Raco, I.; Siliquini, R. Vaccine Hesitancy and Fear of COVID-19 Among Italian Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Community Health 2022, 47, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecce, M.; Milani, G.P.; Agostoni, C.; D’Auria, E.; Banderali, G.; Biganzoli, G.; Castellazzi, L.; Paramithiotti, C.; Salvatici, E.; Tommasi, P.; et al. Caregivers’ Intention to Vaccinate Their Children Under 12 Years of Age Against COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Center Study in Milan, Italy. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giuseppe, G.; Pelullo, C.P.; Lanzano, R.; Lombardi, C.; Nese, G.; Pavia, M. COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake and Related Determinants in Detained Subjects in Italy. Vaccines 2022, 10, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbo, C.; Candini, V.; Ferrari, C.; d’Addazio, M.; Calamandrei, G.; Starace, F.; Caserotti, M.; Gavaruzzi, T.; Lotto, L.; Tasso, A.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Italy: Predictors of Acceptance, Fence Sitting and Refusal of the COVID-19 Vaccination. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 873098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonsenso, D.; Valentini, P.; Macchi, M.; Folino, F.; Pensabene, C.; Patria, M.F.; Agostoni, C.; Castaldi, S.; Lecce, M.; Giannì, M.L.; et al. Caregivers’ Attitudes Toward COVID-19 Vaccination in Children and Adolescents With a History of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardino, U.; Musso, P.; Inguglia, C.; Ceccon, C.; Miconi, D.; Rousseau, C. Sociodemographic and psychological correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in the young adult population in Italy. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2379–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, C.; Graziano, G.; Bonaccorso, N.; Conforto, A.; Cimino, L.; Sciortino, M.; Scarpitta, F.; Giuffrè, C.; Mannino, S.; Bilardo, M.; et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions and Vaccination Acceptance/Hesitancy among the Community Pharmacists of Palermo’s Province, Italy: From Influenza to COVID-19. Vaccines 2022, 10, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, G.M.; Napoli, A.; Corea, F.; Folcarelli, L.; Angelillo, I.F. Evaluating COVID-19 Vaccine Willingness and Hesitancy among Parents of Children Aged 5–11 Years with Chronic Conditions in Italy. Vaccines 2022, 10, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folcarelli, L.; Del Giudice, G.M.; Corea, F.; Angelillo, I.F. Intention to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Dose in a University Community in Italy. Vaccines 2022, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, C.; Costantino, C.; Odone, A.; Trimarchi, G.; La Fauci, V.; Mazzitelli, F.; D’amato, S.; Squeri, R. A Knowledge, Attitude, and Perception Study on Flu and COVID-19 Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Multicentric Italian Survey Insights. Vaccines 2022, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colciago, E.; Capitoli, G.; Vergani, P.; Ornaghi, S. Women’s attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy: A survey study in northern Italy. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regazzi, L.; Marziali, E.; Lontano, A.; Villani, L.; Paladini, A.; Calabrò, G.E.; Laurenti, P.; Ricciardi, W.; Cadeddu, C. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors toward COVID-19 vaccination in a sample of Italian healthcare workers. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18, 2116206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrone, C.; Fiabane, E.; Maffoni, M.; Pierobon, A.; Setti, I.; Sommovigo, V.; Gabanelli, P. Vaccination hesitancy: To be vaccinated, or not to be vaccinated, that is the question in the era of COVID-19. Public Health Nurs. 2022, 40, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomietto, M.; Comparcini, D.; Simonetti, V.; Papappicco, C.A.M.; Stefanizzi, P.; Mercuri, M.; Cicolini, G. Attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination in the nursing profession: Validation of the Italian version of the VAX scale and descriptive study. Ann. Ig. 2022, 34, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monami, M.; Gori, D.; Guaraldi, F.; Montalti, M.; Nreu, B.; Burioni, R.; Mannucci, E. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Early Adverse Events Reported in a Cohort of 7,881 Italian Physicians. Ann. Ig. 2022, 34, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papini, F.; Mazzilli, S.; Paganini, D.; Rago, L.; Arzilli, G.; Pan, A.; Goglio, A.; Tuvo, B.; Privitera, G.; Casini, B. Healthcare Workers Attitudes, Practices and Sources of Information for COVID-19 Vaccination: An Italian National Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.; Della Polla, G.; Angelillo, S.; Pelullo, C.P.; Licata, F.; Angelillo, I.F. Parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A cross-sectional survey in Italy. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2022, 21, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contoli, B.; Possenti, V.; Minardi, V.; Binkin, N.J.; Ramigni, M.; Carrozzi, G.; Masocco, M. What Is the Willingness to Receive Vaccination Against COVID-19 Among the Elderly in Italy? Data From the PASSI d’Argento Surveillance System. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, A.; Invernizzi, F.; Centorrino, E.; Vecchi, M.; Lampertico, P.; Donato, M.F. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Liver Transplant Recipients. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zona, S.; Partesotti, S.; Bergomi, A.; Rosafio, C.; Antodaro, F.; Esposito, S. Anti-COVID Vaccination for Adolescents: A Survey on Determinants of Vaccine Parental Hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchi, S.; Torreggiani, M.; Chatrenet, A.; Fois, A.; Mazé, B.; Njandjo, L.; Bianco, G.; Lepori, N.; Pili, A.; Michel, P.A.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Patients on Dialysis in Italy and France. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 2763–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoccimarro, D.; Panichi, L.; Ragghianti, B.; Silverii, A.; Mannucci, E.; Monami, M. Sars-CoV2 vaccine hesitancy in Italy: A survey on subjects with diabetes. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salerno, L.; Craxì, L.; Amodio, E.; Lo Coco, G. Factors Affecting Hesitancy to mRNA and Viral Vector COVID-19 Vaccines among College Students in Italy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccio, M.D.; Boccalini, S.; Rigon, L.; Biamonte, M.A.; Albora, G.; Giorgetti, D.; Bonanni, P.; Bechini, A. Factors Influencing SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy in a Population-Based Sample in Italy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, A.; Topa, M.; Roncoroni, L.; Doneda, L.; Lombardo, V.; Stocco, D.; Gramegna, A.; Costantino, C.; Vecchi, M.; Elli, L. COVID-19 Vaccine: A Survey of Hesitancy in Patients with Celiac Disease. Vaccines 2021, 9, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalti, M.; Rallo, F.; Guaraldi, F.; Bartoli, L.; Po, G.; Stillo, M.; Perrone, P.; Squillace, L.; Dallolio, L.; Pandolfi, P.; et al. Would Parents Get Their Children Vaccinated Against SARS-CoV-2? Rate and Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy According to a Survey over 5000 Families from Bologna, Italy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reno, C.; Maietti, E.; Fantini, M.P.; Savoia, E.; Manzoli, L.; Montalti, M.; Gori, D. Enhancing COVID-19 Vaccines Acceptance: Results from a Survey on Vaccine Hesitancy in Northern Italy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, F.; Murri, R.; Segala, F.V.; Cerruti, L.; Abdulle, A.; Saracino, A.; Bavaro, D.F.; Fantoni, M. Attitudes towards Anti-SARS-CoV2 Vaccination among Healthcare Workers: Results from a National Survey in Italy. Viruses 2021, 13, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, F.; Aria, M.; Esposito, V.; Micillo, M.; Cecere, G.; Spano, M.; De Marco, G. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A survey in a population highly compliant to common vaccinations. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 3348–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gursoy, D.; Maier, T.A.; Chi, C.G. Generational differences: An examination of work values and generational gaps in the hospitality workforce. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monitoraggio Settimanale Dell'epidemia da COVID-19 in Italia a Cura Della Fondazione GIMBE. Available online: https://coronavirus.gimbe.org/emergenza-coronavirus-italia/monitoraggio-settimanale.it-IT.html#:~:text=Il%20monitoraggio%20indipendente%20della%20Fondazione,i%2032%20mila%20casi%20giornalieri (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Profeti, S. ‘I hope you like jabbing, too’. The Covid vaccination campaign in Italy and the measures to promote compliance. Contemp. Ital. Politics 2022, 14, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero Della Salute. Vaccini Anti COVID-19. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioFaqNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?id=255&lingua=italiano (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Ministero Della Salute. Fake News. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/archivioFakeNewsNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&tagId=881 (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Bozzola, E.; Staiano, A.M.; Spina, G.; Zamperini, N.; Marino, F.; Roversi, M.; Corsello, G.; Villani, A.; Agostiniani, R.; Memo, L.; et al. Social media use to improve communication on children and adolescent’s health: The role of the Italian Paediatric Society influencers. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, H.J.; de Figueiredo, A.; Xiahong, Z.; Schulz, W.S.; Verger, P.; Johnston, I.G.; Cook, A.R.; Jones, N.S. The State of Vaccine Confidence 2016: Global Insights Through a 67-Country Survey. EBioMedicine 2016, 12, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekhar, R.; Sheikh, A.B.; Upadhyay, S.; Singh, M.; Kottewar, S.; Mir, H.; Barrett, E.; Pal, S. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Health Care Workers in the United States. Vaccines 2021, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.; Stewart, T.; Anderson, K.; Hanley, S.; Thomas, S.; Salmon, D.; Morley, C. Assessment of US health care personnel (HCP) attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination in a large university health care system. Clin. Infect Dis. 2021, 73, 1776–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmann-Littig, C.; Frank, T.; Schmaderer, C.; Braunisch, M.C.; Renders, L.; Kranke, P.; Popp, M.; Seeber, C.; Fichtner, F.; Littig, B.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccines: Fear of Side Effects among German Health Care Workers. Vaccines 2022, 10, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apuke, O.D.; Omar, B. Fake news and COVID-19: Modelling the predictors of fake news sharing among social media users. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 56, 101475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero Della Salute. Estensione di Indicazione di Utilizzo del Vaccino Comirnaty (BioNTech/Pfizer) per la Fascia di età 6 mesi-4 Anni (Compresi). Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2022&codLeg=90956&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Cadeddu, C.; Daugbjerg, S.; Ricciardi, W.; Rosano, A. Beliefs towards vaccination and trust in the scientific community in Italy. Vaccine 2020, 38, 6609–6617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engin, C.; Vezzoni, C. Who’s Skeptical of Vaccines? Prevalence and Determinants of Anti-Vaccination Attitudes in Italy. Popul. Rev. 2020, 59, 156–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tambone, V.; Frati, P.; De Micco, F.; Ghilardi, G.; Fineschi, V. How to fix democracy to fix health care. Lancet 2022, 399, 433–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frati, P.; La Russa, R.; Di Fazio, N.; Del Fante, Z.; Delogu, G.; Fineschi, V. Compulsory vaccination for healthcare workers in Italy for the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Vaccines 2021, 9, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Halth Organization. Vaccination and Trust How Concerns Arise and the Role of Communication in Mitigating Crises. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/329647/Vaccines-and-trust.PDF (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- D’Errico, S.; Turillazzi, E.; Zanon, M.; Viola, R.V.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. The Model of “Informed Refusal” for Vaccination: How to Fight against Anti-Vaccinationist Misinformation without Disregarding the Principle of Self-Determination. Vaccines 2021, 9, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaboue, M.; Ferrara, M.; Bertozzi, G.; Berritto, D.; Volonnino, G.; La Russa, R.; Lacasella, G. To vaccinate or not: Literacy against hesitancy. Medicina Historica 2022, 6, e2022014. [Google Scholar]

- La Comunicazione Della Vaccinazione anti COVID-19 sui siti Web Delle Regioni e Province Autonome Italiane. Available online: https://www.agenas.gov.it/images/agenas/In%20primo%20piano/2021/vaccini_siti/Report_conferenza_18_maggio.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).