Abstract

Background: Since the advent of global COVID-19 vaccination, several studies reported cases of encephalitis with its various subtypes following COVID-19 vaccinations. In this regard, we conducted a systematic review to investigate and characterize the clinical settings of these reported cases to aid in physician awareness and proper care provision. Methods: We systematically searched PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus and manually searched Google Scholar. Studies published until October 2022 were included. Demographic data, clinical features, vaccine data, treatment lines, and outcomes were extracted. Results: A total of 65 patients from 52 studies were included. The mean age of patients was 46.82 ± 19.25 years, 36 cases (55.4%) were males. AstraZeneca was the most-reported vaccine associated with encephalitis (38.5%) followed by Pfizer (33.8%), Moderna (16.9%), and others. Moat encephalitis cases occurred after the first dose of vaccination in 41/65 (66.1%). The mean time between vaccination and symptom onset was 9.97 ± 7.16 days. Corticosteroids (86.2 %) and immunosuppressants (81.5 %) were the most used lines of treatment. The majority of affected individuals experienced a full recovery. Conclusion: Our study summarizes the current evidence of reported post-vaccination encephalitis, regarding clinical presentation, symptoms onset, management, outcomes, and comorbid conditions; however, it fails to either acknowledge the incidence of occurrence or establish a causal relationship between various COVID-19 vaccines and encephalitis.

1. Introduction

Encephalitis is an inflammation of the brain tissues and is most usually caused by a viral infection (mainly herpes simplex virus), which represents about 75% of diagnosed cases; however, autoimmune causes such as N-methyl D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antibody encephalitis are also common [1]. Encephalitis is a neurological emergency that can cause severe cognitive impairment or death if not treated promptly. It can be diagnosed by at least two of the following criteria: fever, seizures, focal neurological findings by a cause of brain parenchymal damage, EEG findings indicative of encephalitis, lumbar puncture pleocytosis (more than four white cells per μL), or neuroimaging findings suggestive of encephalitis [2].

Recently, COVID-19 emerged as a new public health crisis affecting worldwide populations. As of the date of this review, 664 million confirmed cases and 6.7 million deaths have been reported since the outbreak in late 2019 [3]. To curtail the development of this disease, research on coronavirus diagnosis, prevention, treatment techniques, and vaccines was launched. The burden was heavily lifted when COVID-19 vaccines emerged. The mechanism of action of various vaccines aim to elicit immune response: the mRNA-based vaccines (PfiZerBioNTech and Moderna) are made up of genetically modified viruses RNA or DNA that produces a viral protein [4,5,6]. The genetically modified non-mRNA adenovirus vector vaccines (Janssen/Johnson and Johnson, Sputnik V, and AstraZeneca) also produce coronavirus proteins [5]. The spike protein or its fragments that resemble COVID-19 are introduced in protein subunit vaccines (Corbevax, Novavax). A killed or weakened COVID-19 virus is introduced in the attenuated viral vaccines Sinopharm and Sinovac Corona Vaccine [6].

Due to the urgency, vaccinations were approved based merely on the initial stages of clinical trials, without completion of all phases [7]. However, adverse reactions to vaccinations, including myelitis and severe disseminated encephalomyelitis, have been identified, although poorly documented [8].

Variable neurological complications after the COVID-19 vaccination, despite the unproven causes, have been reported. These include functional neurological disorder symptoms, such as altered mental status, autoimmune encephalitis (AE), acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), dizziness, myalgia, fatigue, cognitive impairment, gait instability, facial palsy, Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS), convulsions, strokes, transverse myelitis, chronic fatigue syndrome, and acute encephalopathy [9,10]. Recently, major neurological complications indicative of vaccination-related autoimmune encephalitis and acute encephalitis after the first dose of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines were reported [11,12,13,14,15]. Notably, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) was consistently reported after the viral vector-based vaccines or inactivated viral vaccine (AstraZeneca, Sputnik V, Sinopharm) [16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

Dutta et al. reported 19,529 neurological adverse events after COVID-19 vaccination, including encephalitis [23]. Zuhorn et al. demonstrated a temporal association between ChAdOx1 nCov-19 vaccination (AstraZeneca) and encephalitic symptoms [24]. The diagnosis of mRNA-1273 vaccine-induced encephalitis and status epilepticus was made by Fan et al. [25] in several recent cases.

The underlying mechanism of such symptomatology is not clearly understood; some researchers theorized that SARS-CoV-2 spike protein produced by mRNA-based vaccines may act as a catalyst for the inflammatory processes that ensue, particularly in autoimmune encephalitis [26].

Globally, vaccine hesitation is linked to a lack of trust in the COVID-19 vaccine’s safety and doubts about its effectiveness. However, vaccination acceptance rates increased to 75.2% last year according to an international survey [27]. Continuous vaccine improvement efforts and modifications are ongoing with the expanding range of immunity and adverse events in vaccinated populations. In this study, we aim to characterize clinical and laboratory features and the diagnostic and management implications of encephalitis cases following COVID-19 vaccinations to aid in physician awareness and proper care provision.

2. Methods

2.1. Database Search

Our systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) checklist. It is registered in PROSPERO database with ID number: CRD42023389901. We performed a systematic literature search of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases, from inception until October 2022, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) [28]. The following search strategy was used (COVID-19 vaccination OR SARS-CoV-2 vaccine OR COVID-19 vaccine) AND (encephalitis). To increase our chances of identifying all relevant studies, we manually retrieved other studies from Google Scholar and performed backward citation analysis.

2.2. Screening and Inclusion Criteria

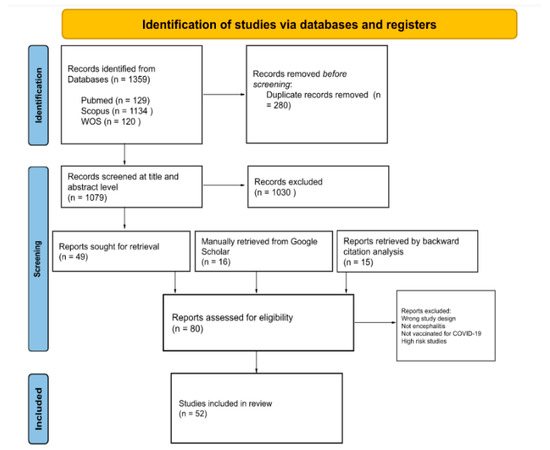

We included all published or pre-published papers presenting cases of any type of encephalitis in individuals who received any type of COVID-19 vaccination either as case reports, case series, or letters to editors. No language restrictions were applied. Secondary studies including reviews and meta-analyses, book chapters, and press releases were excluded from our study. Studies underwent title and abstract blind screening by two reviewers using Rayyan Artificial Intelligence [29]. After the removal of duplicates, the identified full-text articles were examined, and we manually assessed retrieved full-text records from Google Scholar and related references of further studies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for included studies.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

To provide a comprehensive understanding of the data included in those studies, we extracted patients’ characteristics (i.e., age and gender), the type of encephalitis, the type and dose of the vaccine, and the latency period before the onset of symptoms. We extracted symptoms, either relating to the nervous system or any other systems, and whether these patients had any other comorbidities. Investigations, treatment, and treatment outcomes were likewise extracted (Table 1). Extracted data were pooled into mean and standard deviation for continuous variables or frequency and percentage for categorical variables (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included patients.

Table 2.

Summary of patients’ characteristics, common symptoms, laboratory and imaging findings, treatment, and treatment outcomes of patients with post-COVID-19 vaccine encephalitis.

2.4. Quality Assessment

For included case reports and case series, we used the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality assessment tools, based on the clinical features, history, diagnoses, interventions, and management plans. Fourteen letters to the editor were excluded from the assessment due to a lack of appropriate assessment tools. Two authors assessed the quality of included studies and resolved conflicts by consensus. For case reports, JBI domains included eight questions, and the case series checklist assessed ten domains. Grades were assigned such that; Low risk: 75–100%, Moderate: 50–74%, High risk < 50%. High-risk studies will be excluded.

3. Results

Out of 1395 studies identified from databases, 280 were excluded as duplicates. We screened 1079 records at a title and abstract level, through which we excluded 1030 records for irrelevancy. At this point, 15 studies retrieved from previous studies and 16 records identified manually through a Google Scholar search were compared with studies eligible for full-text screening (n = 49), excluding duplicates. In total, 80 records were assessed through full-text screening, from which 11 studies were excluded for reporting CNS infections other than encephalitis and non-COVID-19 vaccination; 14 systematic reviews, literature reviews, and meta-analyses were excluded; 3 studies were excluded for being high risk on quality assessment. In total, 52 studies were included in the final qualitative synthesis, see Figure 1.

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Patients’ mean age was (46.82 SD 19.25) years, 55.4% of patients were males (37/28), and one case presented as a transgender male. Twenty-four patients (36.9%) had several comorbidities, including hypertension, DM, PD, heart disease, hypothyroidism, polymyalgia rheumatica, polyallergy, herpes simplex, migraine, MS, irritable bowel, kidney disease, hyperlipidemia, SARS-CoV-2, Tolosa–Hunt syndrome, CLL, benign prostate hyperplasia, pulmonary embolism, mycoplasma pneumonia, vasculitis, and fibromyalgia. The mean time for symptoms appearance post-vaccination was 9.97 ± 7.16, which was mostly reported after the first dose (66.1%), followed by the second dose (29%), the booster dose (3.2%) and the third dose (1.6%), see Table 2.

3.2. Clinical Presentation

Of all 65 patients, 11 presented with Acute encephalitis (16.9%), 15 with Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) (23.1%), 4 with Acute hemorrhagic encephalitis (AHEM) (6.2 %), and 35 cases with other types of encephalitis (53.8%) encompassing: unspecified Autoimmune encephalitis, Anti-LGI1 encephalitis, Anti-NMDAR encephalitis, Meningoencephalitis, Acute encephalopathy, Herpes simplex encephalitis, Rasmussen encephalitis, Limbic encephalitis, Bickerstaff Brainstem Encephalitis, Brainstem encephalitis, Encephalomyelitis, Multifocal Necrotizing Encephalitis, Anti-GAD encephalitis, and MOG encephalomyelitis, see Table 1.

All 65 patients presented with both neurologic symptoms. Most occurring neurologic symptoms were fever in 23/65 (35.4%) and abnormal movements in 24/65 (36.9%), headache occurred in 20/65 (30.8%) patients, and seizure occurred in 15/65 (23.1%) patients, see Table 2. Other reported neurologic symptoms included dysarthria, aphasia, dysphasia, altered mental status, gait disturbance, cognitive decline, general weakness, hypophonia, ataxia, disturbed conscious level, paraplegia, numbness, areflexia, agitation, spasms, FBDS, behavioral disturbances, memory impairment, status epilepticus, Lhermitte’s phenomenon, paraparesis, hypoesthesia, sphincter dysfunction, Babinski sign, hallucinations, spontaneous defecation, psychosis, coma, urinary retention, diplopia, photophobia, psychological changes, hypoglossal nerve paralysis, dizziness, taste disorder, and facial nerve paralysis. Non-neurologic symptoms were present in 36 patients (55.3%) and included: ophthalmoparesis, ophthalmoplegia, papilledema, optic neuritis, photophobia, blurred vision, aspiration pneumonia, cough, palpitation, myocarditis, bradyphrenia, sinus tachycardia, cardiac pauses, silent myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, dehydration, hypersomnia, myalgia, dizziness, back pain, fatigue, loss of appetite, ketoacidosis, sepsis, urinary tract infection, reactive arthritis, and skin rash. Three patients (4.6%) were hospitalized, see Table 1.

3.3. Investigations and Diagnostic Results

Diagnostic test results were primarily available for CSF and MRI findings; 61.5% (40/60) of MRI results were abnormal with the following findings: FLAIR, T2, and DWI hyperintensities in various regions, central focal hemorrhage, bilateral white matter lesions, minimal T2 sulcal hyperintensity without contrast enhancement, plaques in periventricular, juxtacortical and cortical areas, swelling and hyperintensities of the anterior part of the optic nerves, restricted diffusion through insular and mesial temporal cortices, swelling of the hippocampus, encephalomalacia in frontoparietal lobes, blurred gadolinium enhancement on T1-weighted images; for MRI spine: multiple enhanced lesions of the spinal cord were found in addition to longitudinal edema along the thoracic spinal cord with contrast enhancement and longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. In CSF, the most common finding was pleocytosis (48.5 %). Seven patients (10.8%) had high protein in their CSF samples, and six had positive CSF antibodies, including ANA, Anti-LGI1, SARS-CoV-2 spike S1 RBD IgG, anti-NMDA, intrathecal IgA, and IgM.

3.4. Treatment Plan and Its Outcomes

All 65 patients received a spectrum of medical treatments (steroids, IVIG, antivirals, immunosuppressive drugs, plasmapheresis, antibiotics, anticonvulsants, and analgesics), and 2 patients received anticoagulants. Most patients, i.e., 56 (86.2%), received steroids and immunosuppressive drugs, while 53 (81.5%) received drugs such as rituximab and tocilizumab. In total, 15 received immunoglobulins (23.1%) and 10 received an antiviral treatment (15.4%). Only 9 patients received plasmapheresis (13.8%).

Overall, 41 patients made a full recovery (63.1%), 11 had residual symptoms (16.9%), and 9 were transferred to a rehabilitation facility for extensive residual symptoms, including hypophonia, disturbed conscious level, dysphagia, vegetative state or coma, short-term memory loss, and tonic-clonic seizures. Four patients (6.2%) died, see Table 2.

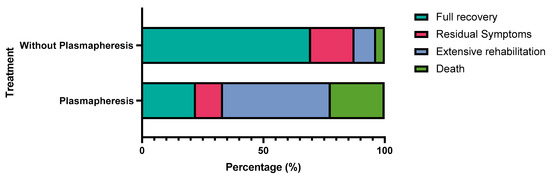

The type of vaccine administered was not statistically associated with any specific outcome (p = 0.124), see Table 3; however, patients with autoimmune encephalitis and other subtypes were more likely to undergo full recovery (p < 0.001), see Table 4. Patients who did not receive plasmapheresis were more likely to make a full recovery (p = 0.002), see Table 5 and Figure 2.

Table 3.

Relation between the type of vaccine and the outcome of treatment.

Table 4.

Relation between the subtypes of encephalitis and the outcome of treatment.

Table 5.

Comparison between the outcome of patients who underwent plasmapheresis versus patients who did not undergo plasmapheresis.

Figure 2.

Comparison between the outcome of patients who underwent plasmapheresis versus patients who did not undergo plasmapheresis.

3.5. Quality Assessment

Fifty-two case reports and three case series were assessed using the JBI checklist, see Table 6. Most case reports (n = 40) had a low risk of bias, nine had a moderate risk, and three had a high risk of bias. All three case series had a moderate risk of bias; data are shown in Table 7. Three high-risk studies were excluded.

Table 6.

Joanna Brigg’s institute critical appraisal checklist for case reports.

Table 7.

Joanna Brigg’s institute critical appraisal checklist for case series.

4. Discussion

In our sampled data, the majority of affected cases were males. According to the demographic distribution, encephalitis was likely to affect all ages, with the highest incidence in patients in their 40s. Most patients complained of encephalitis after the first dose 1–2 weeks post-vaccination. AstraZeneca was the most reported vaccine followed by Pfizer, Moderna, and others. Unlike typical diagnostic criteria for encephalitis (major criteria of patients presenting with altered mental status lasting ≥24 h with no alternative cause identified), the most occurring symptoms in our study were abnormal movements, fever, headache, and seizures [30]. CSF encephalitic findings and MRI abnormalities were evident in almost two-thirds of included patients. Most patients received corticosteroids as a part of the immunosuppressive regimen and achieved full recovery. However, death was common in patients who received plasmapheresis, which, to our understanding, could be contributed to the already late presentation and severe symptoms, which prompted plasma exchange therapy in the first place.

Although the exact etiology of vaccine-induced encephalitis is still not fully understood, it could be attributed to different potential mechanisms of vaccine-induced autoimmune diseases. COVID-19 vaccine was shown to trigger proinflammatory cytokine expression and the response of T-cells as in other vaccines [31]. This is important because these cytokines may reach the brain and activate microglial cells resulting in neuroinflammation [32]. However, the possible molecular mimicry between the vaccine antigens and self-antigens, or the acceleration of an ongoing autoimmune process caused by vaccines are still considered potential mechanisms [33].

Myalgia and general weakness were considered the most reported symptoms in a previous clinical trial assessing the safety of the AstraZeneca vaccine; notably, only two cases presented with neurologic symptoms, such as demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy and hypoesthesia. Nonetheless, no encephalitis-associated symptoms were reported [34]. To our knowledge, no other clinical trials reported encephalitis post-vaccination. As the vaccinated population increased, several SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have been associated with neurological side effects on follow-up observational studies [35]. Most reported cases in the literature were immunized by AstraZeneca and Pfizer. The incidence of encephalitis after vaccination with the AstraZeneca and Pfizer-Biontech mRNA vaccines was estimated to be 8 per 10 million and 2 per 10 million vaccination doses, respectively, which denotes an extremely rare incidence of adverse event occurrence in comparison to other well-established vaccines such as hepatitis vaccines [24]. A previous systematic review addressing 11 patients with autoimmune encephalitis also corresponds with a greater majority of AstraZeneca and Pfizer predominant case reporting (8/15) [31]. Consistent with our findings, in which AstraZeneca and Pfizer comprised almost two-thirds of available cases. However, no statistical correlation between vaccine subtype and encephalitis outcomes could be established in our study. Generally, performing a lumbar puncture can suggest the presence of encephalitic involvement [36]. Huang et al. presented 9/11 cases with lumbar puncture findings indicating encephalitic changes. In our study, CSF sample abnormalities were indeed reported in most cases followed by MRI abnormalities. Full recovery is indicated in a greater percentage of all the aforementioned studies and also in our study.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this systematic review is the use of a thorough search strategy to locate studies for evaluation, minimizing selection bias. These studies were evaluated using established critical appraisal tools and individually assessed by two authors to estimate the risk of bias in each study. We were able to synthesize comprehensive descriptive statistics. On the other hand, however, only 65 patients were included, which was considered insufficient to reach a precise conclusion. For a clear association between encephalitis and COVID-19 vaccination, a larger sample size with consistent reporting of clinical phases is required. To reduce the reporting bias, more clinical trials with appropriate follow-up of the treatment protocol must be analyzed. This would give a better insight into the severity and prognosis of the condition. Other limitations inherent to the nature of our systematic review of case reports and series follow naturally and must be considered.

5. Conclusions

With the increasing population of vaccinated individuals, a growing body of literature introduced a variety of rare side effects including encephalitis with its various subtypes. Studies included in our report should prompt awareness of possible encephalitis cases with presenting symptoms of abnormal movements, fever, and seizures, particularly 2–3 weeks post-vaccination. Physicians must pay attention to such adverse effects as they can be easily managed if noticed promptly and with excellent recovery rates. Further studies are needed to understand the underlying pathophysiologic mechanism and investigate an association relationship. Due to rarity of reported cases and good overall recovery, we still recommend COVID-19 vaccination.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.; Screening, M.A., M.A.E., M.A.H., M.M.A., M.M. and L.S.M.; Protocol, M.A.E.; Formal analysis, M.A. and A.A.; Data extraction, M.A., A.A., Y.H., M.A.E., M.A.H., M.M.A., L.S.M. and M.M.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.A.H., M.A.E. and Y.H.; Writing—review and editing, A.N., A.A., M.A., M.M.A., Y.H. and L.S.M.; Visualization, M.M.A. and A.A.; Supervision, A.N., A.A. and M.A.; Validation: A.A., A.N. and M.A.; Software: A.A., A.N. and M.A.; Resources A.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as this is a secondary study incorporating data from previously published studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived as no patient identification data were included for this is a secondary study incorporating data from previously published studies.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this systematic review are available from the original studies, but restrictions may apply. Some authors may not have provided open access to their data. All data are available upon reasonable request and with permission of the original authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Granerod, J.; Ambrose, H.E.; Davies, N.W.S.; Clewley, J.P.; Walsh, A.L.; Morgan, D.; Cunningham, R.; Zuckerman, M.; Mutton, K.J.; Solomon, T.; et al. Causes of encephalitis and differences in their clinical presentations in England: A multicentre, population-based prospective study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellul, M.; Solomon, T. Acute encephalitis—Diagnosis and management. Clin. Med. 2018, 18, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019?adgroupsurvey={adgroupsurvey}&gclid=Cj0KCQiAiJSeBhCCARIsAHnAzT88OV4oFdsSZEUH8dm2dTrqizrL4qFUaSGociASz3fTLjYEhyp3vw0aAmayEALw_wcB (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Sahin, U.; Muik, A.; Derhovanessian, E.; Vogler, I.; Kranz, L.M.; Vormehr, M.; Baum, A.; Pascal, K.; Quandt, J.; Maurus, D.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and TH1 T-cell responses. Nature 2020, 586, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascellino, M.T.; Di Timoteo, F.; De Angelis, M.; Oliva, A. Overview of the Main Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines: Mechanism of Action, Efficacy and Safety. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 3459–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abufares, H.I.; Oyoun Alsoud, L.; Alqudah, M.A.Y.; Shara, M.; Soares, N.C.; Alzoubi, K.H.; El-Huneidi, W.; Bustanji, Y.; Soliman, S.S.M.; Semreen, M.H.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccines, Effectiveness, and Immune Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skowronski, D.M.; De Serres, G. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1576–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.J.; Dutta, S.; Bhardwaj, P.; Charan, J.; Dhingra, S.; Mitra, P.; Singh, K.; Yadav, D.; Sharma, P.; Misra, S. Adverse Events Reported From COVID-19 Vaccine Trials: A Systematic Review. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2021, 36, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.K.; Paliwal, V.K. Spectrum of neurological complications following COVID-19 vaccination. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 43, 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meppiel, E.; Peiffer-Smadja, N.; Maury, A.; Bekri, I.; Delorme, C.; Desestret, V.; Gorza, L.; Hautecloque-Raysz, G.; Landre, S.; Lannuzel, A.; et al. Neurologic manifestations associated with COVID-19: A multicentre registry. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vences, M.A.; Canales, D.; Albujar, M.F.; Barja, E.; Araujo-Chumacero, M.M.; Cardenas, E.; Alvarez, A.; Urrunaga-Pastor, D. Post-Vaccinal Encephalitis with Early Relapse after BNT162b2 (COMIRNATY) COVID-19 Vaccine: A Case Report. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.-J.; Tseng, H.-P.; Lin, C.-L.; Hsu, R.-F.; Lee, M.-H.; Liu, C.-H. Acute encephalitis after COVID-19 vaccination: A case report and literature review. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2082206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyu, S.; Fan, H.-T.; Shang, S.-T.; Chan, J.-S.; Chiang, W.-F.; Chiu, C.-C.; Chen, M.-H.; Shyu, H.-Y.; Hsiao, P.-J. Clinical Manifestation, Management, and Outcomes in Patients with COVID-19 Vaccine-Induced Acute En-cephalitis: Two Case Reports and a Literature Review. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnik, Y.; Gadoth, A.; Abu-Salameh, I.; Horev, A.; Novoa, R.; Ifergane, G. Case Report: Anti-LGI1 Encephalitis Following COVID-19 Vaccination. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 813487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asaduzzaman, M.; Purkayastha, B.; Alam, M.M.J.; Chakraborty, S.R.; Roy, S.; Ahmed, N. COVID-19 mRNA vaccine-associated encephalopathy, myocarditis, and thrombocytopenia with ex-cellent response to methylprednisolone: A case report. J. Neuroimmunol. 2022, 368, 577883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaratnam, S.A.; Ferdi, A.C.; Leaney, J.; Lee, R.L.K.; Hwang, Y.T.; Heard, R. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis with bilateral optic neuritis following ChAdOx1 COVID-19 vaccination. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, V.; Bellucci, G.; Romano, A.; Bozzao, A.; Salvetti, M. ADEM after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine: A case report. Mult. Scler. J. 2022, 28, 1151–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permezel, F.; Borojevic, B.; Lau, S.; de Boer, H.H. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) following recent Ox-ford/AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2022, 18, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quliti, K.; Qureshi, A.; Quadri, M.; Abdulhameed, B.; Alanazi, A.; Alhujeily, R. Acute Demyelinating Encephalomyelitis Post-COVID-19 Vaccination: A Case Report and Literature Review. Diseases 2022, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaro, L.G.; Cossio, J.E.P.; Luis, M.B.; Tamagnini, F.; Mejia, D.A.P.; Solarz, H.; Liguori, N.A.F.; Alonso, R.N. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2: A case report. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2022, 20, 100439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, F.; Iranpour, P.; Haseli, S.; Poursadeghfard, M.; Yarmahmoodi, F. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: A case report. Radiol. Case Rep. 2022, 17, 1789–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Ren, L. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination: A case report. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2022, 122, 793–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Kaur, R.; Charan, J.; Bhardwaj, P.; Ambwani, S.R.; Babu, S.; Goyal, J.P.; Haque, M. Analysis of Neurological Adverse Events Reported in VigiBase From COVID-19 Vaccines. Cureus 2022, 14, e21376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuhorn, F.; Graf, T.; Klingebiel, R.; Schäbitz, W.; Rogalewski, A. Postvaccinal Encephalitis after ChAdOx1 nCov-19. Ann. Neurol. 2021, 90, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.-T.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Chiang, W.-F.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chen, M.-H.; Wu, K.-A.; Chan, J.-S.; Kao, Y.-H.; Shyu, H.-Y.; Hsiao, P.-J. COVID-19 vaccine-induced encephalitis and status epilepticus. Qjm Int. J. Med. 2022, 115, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mashdali, A.F.; Ata, Y.M.; Sadik, N. Post-COVID-19 vaccine acute hyperactive encephalopathy with dramatic response to methylprednisolone: A case report. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 69, 102803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Wyka, K.; White, T.M.; Picchio, C.A.; Rabin, K.; Ratzan, S.C.; Leigh, J.P.; Hu, J.; El-Mohandes, A. Revisiting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy around the world using data from 23 countries in 2021. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, A.; Tunkel, A.R.; Bloch, K.C.; Lauring, A.S.; Sejvar, J.; Bitnun, A.; Stahl, J.-P.; Mailles, A.; Drebot, M.; Rupprecht, C.E.; et al. Case definitions, diagnostic algorithms, and priorities in encephalitis: Consensus statement of the international encephalitis consortium. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 1114–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-F.; Ho, T.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Shen, D.H.-Y.; Chan, H.-P.; Chuang, K.-P.; Tyan, Y.-C.; Yang, M.-H. A Rare Adverse Effect of the COVID-19 Vaccine on Autoimmune Encephalitis. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervé, C.; Laupèze, B.; Del Giudice, G.; Didierlaurent, A.M.; Tavares Da Silva, F. The how’s and what’s of vaccine reac-togenicity. Npj Vaccines 2019, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, E.; Shrestha, A.K.; Colantonio, M.A.; Liberio, R.N.; Sriwastava, S. Acute transverse myelitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: A case report and review of literature. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falsey, A.R.; Sobieszczyk, M.E.; Hirsch, I.; Sproule, S.; Robb, M.L.; Corey, L.; Neuzil, K.M.; Hahn, W.; Hunt, J.; Mulligan, M.J.; et al. Phase 3 Safety and Efficacy of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) COVID-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 2348–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maramattom, B.V.; Lotlikar, R.S.; Sukumaran, S. Central nervous system adverse events after ChAdOx1 vaccination. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 43, 3503–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotta, E.M.; Batra, A.; Clark, J.R.; Shlobin, N.A.; Hoffman, S.C.; Orban, Z.S.; Koralnik, I.J. Frequent neurologic manifestations and encephalopathy-associated morbidity in COVID-19 patients. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2020, 7, 2221–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).