Abstract

Numerous mysteries of cell and molecular biology have been resolved through extensive research into intracellular processes, which has also resulted in the development of innovative technologies for the treatment of infectious and non-infectious diseases. Some of the deadliest diseases, accounting for a staggering number of deaths, have been caused by viruses. Conventional antiviral therapies have been unable to achieve a feat in combating viral infections. As a result, the healthcare system has come under tremendous pressure globally. Therefore, there is an urgent need to discover and develop newer therapeutic approaches against viruses. One such innovative approach that has recently garnered attention in the research world and can be exploited for developing antiviral therapeutic strategies is the PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTAC) technology, in which heterobifunctional compounds are employed for the selective degradation of target proteins by the intracellular protein degradation machinery. This review covers the most recent advancements in PROTAC technology, its diversity and mode of action, and how it can be applied to open up new possibilities for creating cutting-edge antiviral treatments and vaccines.

1. Introduction

Investigation of intracellular processes has not only provided answers to various fundamental questions in cell and molecular biology but also led to the development of new technologies for the treatment of infectious and non-infectious diseases. For example, the research on understanding protein degradation and homeostasis has led to the development of technologies for targeted protein degradation, a new therapeutic modality currently being used to target biomedically relevant proteins that are not amenable to conventional small-molecule inhibitors. In targeted protein degradation, multi-specific small molecules redirect the cellular protein degradation machinery toward the target protein of interest (POI). The PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTAC), a technology for targeted protein degradation, relies on using heterobifunctional molecules to recruit intracellular protein degradation machinery to the intracellular target protein of interest [1]. This chemically-induced proximity between protein degradation machinery and the target POI results in polyubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of the target protein [2]. Despite the field of PROTAC technology being relatively new, PROTACs have found wide applications not just as a technical tool but also as a therapeutic approach for infectious and non-infectious diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [3,4,5,6].

Viruses have been known to cause many global pandemics throughout the history of humankind, leading to massive deaths. Some of the deadliest diseases have been caused by viruses, including AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), smallpox, Ebola, certain cancers, and the most recent pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). This has put enormous pressure on the global healthcare system, which other diseases have already constrained. Some currently used antiviral strategies include small molecule inhibitors that inhibit the target viral proteins and vaccines that help generate a robust immune response against a viral pathogen. Small molecule inhibitors interact with the key proteins essential for viral replication at different stages of the viral life cycle. These conventional methods share limitations, including incomplete inhibition of viral proteins and poor immunogenic response. Extensive research has been conducted to determine viral targets for developing efficient antiviral therapies. Developing effective vaccines against viruses with a rapidly evolving genome is a huge challenge. The diversity in the genetic pool of such viruses makes it difficult to select and identify a viral epitope that can be used to elicit an effective immune response [7]. Existing strategies and technologies fail to decipher the evolving genome of viruses and thus lack specificity in targeting viruses. Newer technologies and approaches that help tackle the drawbacks of conventional vaccines are the need of the hour in the face of the ongoing pandemic.

This review discusses recent advancements in PROTAC technology and its potential to develop alternative antiviral therapeutic strategies. We aim to explore further the current understanding of this technology, its mechanism of action, diversity, and applicability as antiviral therapeutics, including its usage to create alternative vaccine strategies.

2. PROTAC as a Tool for Targeted Protein Degradation

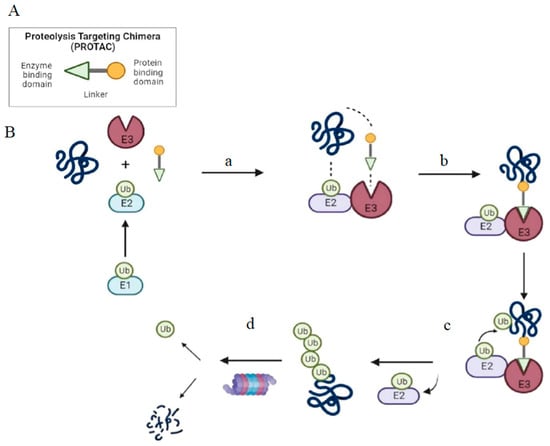

The intracellular protein degradation involves an array of proteins, including chaperones and the ubiquitin-proteasome system [8]. While the ubiquitin-proteasome system removes the unfolded and damaged proteins, the chaperone corrects any misfolding of the proteins. The 26S ubiquitin-proteasome system consists of one or two 19S regulatory subunit(s) which dictate(s) substrate specificity for proteasome-dependent cleavage and a 20S proteasome core which degrades the unfolded proteins [9]. The proteins meant for degradation by the proteasome are modified post-translationally by covalent tagging with the small ubiquitin (Ub) protein. This ubiquitylation involves a cascade of three enzymes: an E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, which activates Ub in an ATP-dependent manner forming the E1-Ub conjugate, an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, which catalyzes transesterification, resulting in the transfer of ubiquitin from E1 to E2, and finally, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which binds both the E2-Ub and the protein substrate and transfers Ub from E2 to the lysine residues of the protein slated for degradation. Repetition of this reaction generates a polyubiquitin chain that directs the proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome [10,11].

The concept of PROTAC was first reported in 2001 when Sakamoto et al. designed PROTAC to specifically degrade MetAP2 (methionine aminopeptidase-2) protein in Xenopus egg extract using a chimeric molecule comprising of MetAP2 ligand ovalicin linked to a phosphopeptide ligand of E3 ubiquitin ligase BTRC. Although peptide-based PROTACs efficiently degrade target proteins, there are some limitations that reduce their utility. For example, their labile nature, high molecular weight, and poor membrane permeability. These limitations were later overcome by synthetic small molecule PROTACs. The first small molecule PROTAC reported in 2008 was comprised of a selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM) as a ligand for the androgen receptor and nutlin as a ligand for the mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2) E3 ligase connected through a PEG-based linker [12]. Further improvements in the small molecule PROTACs expanded their use to in vivo depletion of the target proteins [13,14].

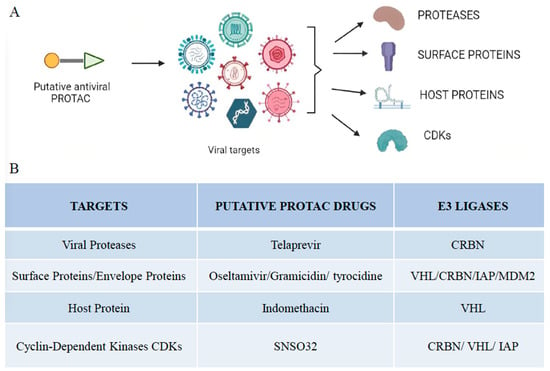

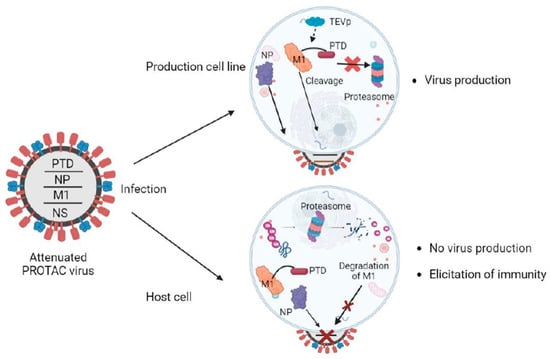

The fundamental structure of PROTAC consists of an “E3 moiety” that binds to the substrate binding domain of E3 ubiquitin ligase, a “protein targeting moiety” that binds to the POI and a linker that joins both the moieties (Figure 1). From recent studies, it has become clear that the effectiveness of overall degradation depends not only on the affinities of the “E3 moiety” and “protein targeting moiety” but also on the length and chemical makeup of the linker [15]. The length and chemical makeup play a crucial role in the formation of the ternary complex, target protein degradation efficiency, and target selectivity [16,17,18]. The substrate preferences of E3 ligases are influenced by the unique molecular architectures formed by the unique combinations of their scaffolding proteins, Ub-loaded E2, adaptor proteins, and substrate binding domains [10,18]. The human proteome currently contains more than 600 distinct E3 ligases.

Figure 1.

Structure and mechanism of PROTAC-based degradation. (A) General structure of a PROTAC: The E3 ligase targeting “anchor” (green) is connected to the specific POI targeting warhead (yellow) via a variable linker; (B) Mechanism of PROTAC-mediated target degradation (a) Ub transfer from E1 to E2, which is followed by complex formation with an E3 ligase; (b) the PROTAC binds to both the E3 ligase and POI to form a TC. This brings the E2 ligase into proximity to the POI; (c) this leads to the transfer of multiple Ub units to surface-exposed lysine residues; (d) the resulting polyubiquitin chain is recognized by the proteasome, leading to the proteolytic degradation of the POI. Ub, Ubiquitin; POI, Protein of interest; TC, Ternary complex.

PROTACs have quickly evolved and are considered a superior alternative to small molecule inhibitors [19,20]. The unique mechanism of PROTAC action enables rapid, long-lasting, and potent biological response against the target protein. The higher specificity of PROTACs reduces side effects that are associated with the off-target binding of conventional small molecule inhibitors [21]. PROTACs are also beneficial and preferred over small-molecule inhibitors as they can target multifunctional proteins with enzymatic and scaffolding roles [22,23].

3. Diversity of PROTACs

The shift in usage from peptide-based PROTACs to small molecule-based PROTACs has revolutionized the field of PROTACs. Small molecule-based PROTACs have been developed for the targeted protein degradation of various proteins such as ALK, Bcl-2 family proteins, Bcl-6, BCR-ABL, BRD4, BTK, FLT-3, HDAC family proteins, MDM2, PLK1, PRC2, and STAT3 among many others [24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Only a handful of the 600 E3 ligases reported in the human proteome have been exploited for developing PROTACs [3,31]. PROTACs can be of many different types based on the number and type of E3 ligase used, the nature of protein targeting moiety, the number of targets degraded, and the type of interactions involved.

The four most commonly used PROTACs, based on the type of E3 ligases used, are MDM2-based, CRBN-based, IAP-based, and VHL based. MDM2 acts as an oncogene that suppresses the activity of the tumor suppressor P53 protein by inducing its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome [32]. The first MDM2-based PROTAC utilized Nutlin-3a as the MDM2 ligand and SARM as the androgen receptor ligand to degrade the androgen receptor. MDM2-based PROTACs have been used to degrade PARP1, BRD4, BTK, TRKC, and HSP90 [33,34,35,36,37].

Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) is a family of proteins that negatively regulate apoptosis and consist of eight members X1AP, cIAP1, cIAP2, Ts-IAP, KIAP, BIRC5, BRUCE, and NAIP. The IAP E3 ligase-based PROTACs against cellular retinoic acid binding proteins (CRABPI and CRABPII) utilized bestatin ester as an IAP-binding ligand and all-trans retinoic acid as ligands for CRABP I and CRABP II. Methyl bestatin and the IAP antagonist LCL161 were used to substitute bestatin to address the shortcomings of bestatin-based PROTACs, such as their low potencies and autoubiquitination of cIAP [14,38]. PROTACs that recruit IAP have been found subsequently target many other proteins, including BCL-xL and BCR-ABL, ER, AR, Retinoic Acid receptors, and transforming acidic coiled-coil-3-containing protein [39,40].

VHL (Von Hippel Ligand) is a ubiquitously expressed E3 ligase; hence, VHL-based PROTACs have found application in many cell types [41,42]. As the transcription factor HIF-α is the natural substrate of VHL, a seven amino acid peptide derived from HIF-α and dihydroxy-testosterone, a ligand androgen receptor (AR), was used to develop a VHL-based PROTAC to degrade AR [43]. The first small molecule, VHL-based PROTAC, was developed against estrogen-related receptor alpha and receptor-interacting serine/threonine kinase 2 [13].

Cereblon (CRBN) forms an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex with the damaged DNA binding protein 1 (DDB1), cullin-4A (CUL4A), and regulator of cullins 1 (ROC1). CRBN is a target of immunomodulatory drugs such as thalidomide, lenalidomide and pomalidomide [44]. In contrast to VHL, CRBN-based PROTACs have been shown to degrade a broader range of proteins [41]. CRBN-based PROTACs are not as tissue-selective as VHL-based PROTACs as they are ubiquitously expressed. In addition, they have a low molecular weight, making them feasible to be developed as an orally bioavailable PROTAC.

Based on the number of E3 ligases used, PROTACs are classified into homobivalent and trivalent PROTACs. Homobivalent PROTACs involve a ternary complex of either a pair of similar kinds of E3 ligases or different kinds of E3 ligases joined by a suitable linker. The first kind of homobivalent PROTACs employs two similar E3 ligases and causes the dimer thus formed to self-ubiquitinate the E3 ligase involved [45]. Some of the commonly used PROTACs of this category include VHL-VHL-based and CRBN-CRBN-based homobivalent PROTACs. [46] The second kind involves two different types of E3 ligases and thus leads to the degradation of either one type of ligase or both [47,48]. Examples of this category include CRBN-VHL-based and MDM2-CRBN-based PROTACs [49,50].

Trivalent PROTACs are also known as two-headed PROTACs due to their degradative actions on two different target proteins. This dual activity permits the trivalent PROTAC molecule to simultaneously target two different proteins of interest [51]. Li and his co-workers synthesized the first trivalent PROTAC molecule using the dual targeting properties of the trivalent PROTACs to target two completely different proteins, PARP1 and EGFR [52]. They were, however, limited in their action by their large molecular weight, poor cellular permeability, and lower solubility.

The covalent PROTACs, yet another class of PROTACs, form an even more stable ternary complex providing improved target specificity and enhanced binding affinities. The covalent PROTACs are designed with the formation of a covalent interaction of a linker with a target protein or an E3 ligase, and these interactions may be reversible or irreversible [53]. These PROTACs have been reported to have high potency and selectivity coupled with covalent interactions that are in a simultaneous loop of formation and dissolution after the target protein has been selected and degraded [54].

Moreover, some other types are developed with a slight divergence in design from the conventional small molecule-based PROTACs. Instead of using small molecules as linkers between an E3 ligase and the protein of interest, BioPROTACs are developed by reengineering the substrate recognition domain of the E3 ligase such that the domain is replaced by a peptide that directly binds to the protein of interest. This eliminates the necessity of finding appropriate ligands for both the E3 ligase and the protein of interest. Though BioPROTACs exhibit poor permeability, they are highly target-specific.

Another category includes AbTACs or antibody-based PROTACs, which exploit bispecific antibodies to cause the targeted degradation of cell surface proteins. A bispecific antibody combines two different proteins and labels them for degradation [55]. These mimic the structure of a PROTAC molecule. Also, highly specific AbTACs can be created by exploiting recombinant technology, which will enhance the affinity of the synthesized molecule for the protein of interest [56].

6. Limitations

As discussed above, PROTACs are advantageous over small molecule inhibitors [109]. However, some concerns linked to PROTAC-based antiviral therapeutics should be addressed before their therapeutic use. Although PROTACs are more powerful than other small molecule inhibitors and completely deplete the desired target protein in the cell, they might cause on-target toxicity in the host cell and may impair normal cell function. Some POIs targeted by PROTACs can have both enzymatic as well as other scaffold functions that may be important for normal cellular functioning. Thus their total elimination can be toxic to the cell [110]. The degradation of the target protein of interest by the PROTAC may also degrade proteins that are directly or indirectly associated with the target protein, resulting in off-target effects. Off-target effects can also cause neomorphic interactions if the PROTAC binds to neo-substrates [111]. Therefore, future research should focus on strategies that can further reduce both on-target and off-target toxicities associated with PROTACs.

7. Future Implications

PROTAC technology is expected to result in the development of promising and potentially next-generation antivirals in the future. The PROTAC technology, unlike the traditional antivirals, has an expanded function against a repertoire of pathogenic proteins and can be effective against resistance acquired by mutating and adapting viruses. The technology in question can be further expanded by exploring a greater number of E3 ligases, apart from the existing collection of known ligases, as genomic alterations in the core of the E3 ligases’ machinery have flared up the resistance to therapies based on PROTAC technology. Developing the appropriate ligands for the target protein and E3 ligase can be assisted by artificial intelligence (protein structure prediction), virtual drug screening, and DEL screening (DNA-encoded library screening). For the quick and efficient construction of large-scale libraries of PROTAC molecules, it is necessary to optimize screened ligands and create effective synthesis methods based on high throughput screening.

Some of the existing drawbacks of PROTAC technology include its large molecular weight, cellular permeability, and metabolic instability of the small molecule-based PROTACs. CLIPTAC (CLIck-formed Proteolysis targeting chimera) technology has been used to counter this issue [112]. In click chemistry, the bifunctional molecule is divided into two parts: a ligand for the target protein, and the other part that binds to the ligase. The parts assemble to form a PROTAC molecule via a rapid reaction in the cell. Because both parts have a low molecular weight and improved cellular permeability, they significantly improve the technology. It has been shown that linkers also significantly impact the activity, selectivity, and druggability of PROTAC compounds. Shorter linker lengths may disrupt the formation of a stable ternary complex due to steric hindrance and restrict the PROTAC molecule from degrading the target protein. In contrast, a longer linker length may increase the molecular weight, reducing cellular permeability and efficacy. Increasing the rigidity of the linker enhances oral bioavailability by constraining a PROTAC molecule in its bioactive conformation.

Despite the increasing surge in the development of PROTAC technology, several concerns are associated with it. Although PROTAC technology is a promising tool for targeting the “undruggable proteome,” only a handful of these sites have been targeted by PROTACs thus far. Additionally, the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of these molecules need to be effectively analyzed and evaluated because the traditional methodologies typically used to evaluate the kinetics and dynamics of conventional small molecules that follow a stoichiometric mechanism of action are ineffective. There is also a growing need to screen for more protein ligands that effectively target protein-protein interactions. Furthermore, since PROTACs can completely degrade the target protein, there is a high probability of cytopathic effects arising from the complete elimination of otherwise essential proteins.

Better molecular design of PROTACs will be possible in the future thanks to more complex information gathered by X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy. Recent advances in alphafold2′s capacity to predict proteins and their associated complex structures may impact how PROTACs are designed. Studies have been carried out to discover newer targets that can effectively enhance the specificity of the technology. One such example is Ribonuclease Targeting Chimeras or RIBOTACs, which have emerged as a new class of small molecules that can potentially target diverse RNA types [113]. These RNA-degrading molecules can selectively bind an RNA-binding molecule to a latent ribonuclease, RNase L, which is involved in the degradation of the RNA molecule upon its activation [114]. RIBOTACs contain a tetra-adenylate component, similar to an oligoadenylate, that causes the dimerization and activation of RNase L, leading to viral RNA degradation.

Emerging and re-emerging viral infectious diseases pose a persistent pandemic threat to humankind, not only because of their negative impact on public health but also because of the possible worldwide economic, social, and political repercussions. Vaccination is the only sought after that could be a preventive measure, and the molecular-based approach may provide a more diverse defense against newly emerging viruses than conventional ones. Further extensive studies that elaborate on the possibility of newer targets and enable enhanced target specificity can contribute towards the advancement in PROTAC technology as potent antiviral therapeutics in the coming years.

Author Contributions

B.Z. and H.A. surveyed the published literature and wrote the first draft of the manuscript with help from H.H.; A.H. conceptualized, designed, and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Start-Up Research Grants from the Department of Science and Technology-Science and Engineering Research Board (SRG-2020-000819) and University Grant Commission (F.30-564/2021 (BSR)), Govt. of India.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thankfully acknowledge the facilities provided by the Aligarh Muslim University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sakamoto, K.M.; Kim, K.B.; Kumagai, A.; Mercurio, F.; Crews, C.M.; Deshaies, R.J. Protacs: Chimeric molecules that target proteins to the Skp1-Cullin-F box complex for ubiquitination and degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 8554–8559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.; Radoux, C.J.; Hercules, A.; Ochoa, D.; Dunham, I.; Zalmas, L.-P.; Hessler, G.; Ruf, S.; Shanmugasundaram, V.; Hann, M.M.; et al. The PROTACtable genome. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Khan, S.; Huo, Z.; Lv, D.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Hromas, R.; Xu, M.; Zheng, G.; et al. Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) are emerging therapeutics for hematologic malignancies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargbo, R.B. PROTAC Degradation of IRAK4 for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative and Cardiovascular Diseases. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 1251–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, K.M.; Kim, K.B.; Verma, R.J.; Ransick, A.; Stein, B.; Crews, C.M.; Deshaies, R. Development of Protacs to Target Cancer-promoting Proteins for Ubiquitination and Degradation. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2003, 2, 1350–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Khoo, R.; Peh, K.M.; Teo, J.; Chang, S.C.; Ng, S.; Beilhartz, G.L.; Melnyk, R.A.; Johannes, C.W.; Brown, C.J.; et al. bioPROTACs as versatile modulators of intracellular therapeutic targets including proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 5791–5800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, A.J.; Bijker, E.M. A guide to vaccinology: From basic principles to new developments. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, P.P.; Hamann, L.G. Development of targeted protein degradation therapeutics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupas, A.; Koster, A.J.; Baumeister, W. Structural Features of 26S and 20S Proteasomes. Enzym. Protein 1993, 47, 252–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershko, A.; Ciechanover, A. The Ubiquitin System for Protein Degradation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1992, 61, 761–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kierszenbaum, A.L. The 26S proteasome: Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis in the tunnel. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2000, 57, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneekloth, A.R.; Pucheault, M.; Tae, H.S.; Crews, C.M. Targeted intracellular protein degradation induced by a small molecule: En route to chemical proteomics. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 5904–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondeson, D.P.; Mares, A.; Smith, I.E.D.; Ko, E.; Campos, S.; Miah, A.H.; Mulholland, K.E.; Routly, N.; Buckley, D.L.; Gustafson, J.L.; et al. Catalytic in vivo protein knockdown by small-molecule PROTACs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohoka, N.; Okuhira, K.; Ito, M.; Nagai, K.; Shibata, N.; Hattori, T.; Ujikawa, O.; Shimokawa, K.; Sano, O.; Koyama, R.; et al. In Vivo Knockdown of Pathogenic Proteins via Specific and Nongenetic Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein (IAP)-dependent Protein Erasers (SNIPERs). J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 4556–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Gao, H.; Yang, Y.; He, M.; Wu, Y.; Song, Y.; Tong, Y.; Rao, Y. PROTACs: Great opportunities for academia and industry. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadd, M.S.; Testa, A.; Lucas, X.; Chan, K.H.; Chen, W.Z.; Lamont, D.J.; Zengerle, M.; Ciulli, A. Structural basis of PROTAC cooperative recognition for selective protein degradation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, N.; Nagai, K.; Morita, Y.; Ujikawa, O.; Ohoka, N.; Hattori, T.; Koyama, R.; Sano, O.; Imaeda, Y.; Nara, H.; et al. Development of Protein Degradation Inducers of Androgen Receptor by Conjugation of Androgen Receptor Ligands and Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein Ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 543–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershko, A.; Heller, H.; Elias, S.; Ciechanover, A. Components of ubiquitin-protein ligase system. Resolution, affinity purification, and role in protein breakdown. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 8206–8214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.C.; Crews, C.M. Induced protein degradation: An emerging drug discovery paradigm. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, H.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, Y. Small molecule PROTACs: An emerging technology for targeted therapy in drug discovery. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 16967–16976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Fu, L. Small-molecule PROTACs: An emerging and promising approach for the development of targeted therapy drugs. Ebiomedicine 2018, 36, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burslem, G.M.; Smith, B.E.; Lai, A.C.; Jaime-Figueroa, S.; McQuaid, D.C.; Bondeson, D.P.; Toure, M.; Dong, H.; Qian, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. The Advantages of Targeted Protein Degradation Over Inhibition: An RTK Case Study. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018, 25, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, M.A.; Schlessinger, J. Cell Signaling by Receptor Tyrosine Kinases. Cell 2010, 141, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Zhou, H.; Xu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Chinnaswamy, K.; McEachern, D.; Chen, J.; Yang, C.-Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, M.; et al. A Potent and Selective Small-Molecule Degrader of STAT3 Achieves Complete Tumor Regression In Vivo. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potjewyd, F.; Turner, A.-M.W.; Beri, J.; Rectenwald, J.M.; Norris-Drouin, J.L.; Cholensky, S.H.; Margolis, D.M.; Pearce, K.H.; Herring, L.E.; James, L.I. Degradation of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 with an EED-Targeted Bivalent Chemical Degrader. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoull, W.; Cheung, T.; Anderson, E.; Barton, P.; Burgess, J.; Byth, K.; Cao, Q.; Castaldi, M.P.; Chen, H.; Chiarparin, E.; et al. Development of a Novel B-Cell Lymphoma 6 (BCL6) PROTAC To Provide Insight into Small Molecule Targeting of BCL6. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 3131–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Dominici, M.; Porazzi, P.; Xiao, Y.; Chao, A.; Tang, H.-Y.; Kumar, G.; Fortina, P.; Spinelli, O.; Rambaldi, A.; Peterson, L.F.; et al. Selective inhibition of Ph-positive ALL cell growth through kinase-dependent and -independent effects by CDK6-specific PROTACs. Blood 2020, 135, 1560–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, M.; Jiang, B.; Bauer, S.; Donovan, K.A.; Liang, Y.; Wang, E.S.; Nowak, R.P.; Yuan, J.C.; Zhang, T.; Kwiatkowski, N.; et al. Homolog-Selective Degradation as a Strategy to Probe the Function of CDK6 in AML. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.-H.; Zengerle, M.; Testa, A.; Ciulli, A. Impact of Target Warhead and Linkage Vector on Inducing Protein Degradation: Comparison of Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal (BET) Degraders Derived from Triazolodiazepine (JQ1) and Tetrahydroquinoline (I-BET726) BET Inhibitor Scaffolds. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Pan, P.; Sun, H.; Xia, H.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Hou, T. Drug Discovery Targeting Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK). J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 10927–10954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalawansha, D.A.; Crews, C.M. PROTACs: An Emerging Therapeutic Modality in Precision Medicine. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27, 998–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Aguilar, A.; Bernard, D.; Yang, C.-Y. Targeting the MDM2–p53 Protein–Protein Interaction for New Cancer Therapy: Progress and Challenges. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017, 7, a026245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Lan, T.; Su, S.; Rao, Y. Induction of apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells by a PARP1-targeting PROTAC small molecule. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.; Lartigue, S.; Dong, H.; Qian, Y.; Crews, C.M. MDM2-Recruiting PROTAC Offers Superior, Synergistic Antiproliferative Activity via Simultaneous Degradation of BRD4 and Stabilization of p53. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, X.; Ding, N.; Gao, H.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Hwang, J.; Song, Y.; Liu, W.; et al. PROTAC-induced BTK degradation as a novel therapy for mutated BTK C481S induced ibrutinib-resistant B-cell malignancies. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 779–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Burgess, K. TrkC-Targeted Kinase Inhibitors and PROTACs. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 4313–4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Tu, G.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, J.; Lin, S.; Yu, Z.; Li, G.; Wu, X.; Tang, Y.; et al. Discovery of BP3 as an efficacious proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) degrader of HSP90 for treating breast cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 228, 114013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, M.; Ohoka, N.; Shibata, N. SNIPERs—Hijacking IAP activity to induce protein degradation. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2019, 31, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demizu, Y.; Okuhira, K.; Motoi, H.; Ohno, A.; Shoda, T.; Fukuhara, K.; Okuda, H.; Naito, M.; Kurihara, M. Design and synthesis of estrogen receptor degradation inducer based on a protein knockdown strategy. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 1793–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demizu, Y.; Shibata, N.; Hattori, T.; Ohoka, N.; Motoi, H.; Misawa, T.; Shoda, T.; Naito, M.; Kurihara, M. Development of BCR-ABL degradation inducers via the conjugation of an imatinib derivative and a cIAP1 ligand. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 4865–4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.C.; Toure, M.; Hellerschmied, D.; Salami, J.; Jaime-Figueroa, S.; Ko, E.; Hines, J.; Crews, C.M. Modular PROTAC Design for the Degradation of Oncogenic BCR-ABL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 807–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondeson, D.P.; Smith, B.E.; Burslem, G.M.; Buhimschi, A.D.; Hines, J.; Jaime-Figueroa, S.; Wang, J.; Hamman, B.D.; Ishchenko, A.; Crews, C.M. Lessons in PROTAC Design from Selective Degradation with a Promiscuous Warhead. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018, 25, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneekloth, J.S., Jr.; Fonseca, F.N.; Koldobskiy, M.; Mandal, A.; Deshaies, R.; Sakamoto, K.; Crews, C.M. Chemical Genetic Control of Protein Levels: Selective in Vivo Targeted Degradation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 3748–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Ando, H.; Suzuki, T.; Ogura, T.; Hotta, K.; Imamura, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Handa, H. Identification of a Primary Target of Thalidomide Teratogenicity. Science 2010, 327, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniaci, C.; Hughes, S.J.; Testa, A.; Chen, W.; Lamont, D.J.; Rocha, S.; Alessi, D.R.; Romeo, R.; Ciulli, A. Homo-PROTACs: Bivalent small-molecule dimerizers of the VHL E3 ubiquitin ligase to induce self-degradation. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinebach, C.; Lindner, S.; Udeshi, N.D.; Mani, D.C.; Kehm, H.; Köpff, S.; Carr, S.A.; Gütschow, M.; Krönke, J. Homo-PROTACs for the Chemical Knockdown of Cereblon. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 2771–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girardini, M.; Maniaci, C.; Hughes, S.J.; Testa, A.; Ciulli, A. Cereblon versus VHL: Hijacking E3 ligases against each other using PROTACs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2019, 27, 2466–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, C.E.; Du, G.; Bushman, J.W.; He, Z.; Zhang, T.; Fischer, E.S.; Gray, N.S. Selective degradation-inducing probes for studying cereblon (CRBN) biology. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Aguilar, A.; McEachern, D.; Przybranowski, S.; Liu, L.; Yang, C.-Y.; Wang, M.; Han, X.; Wang, S. Discovery of MD-224 as a First-in-Class, Highly Potent, and Efficacious Proteolysis Targeting Chimera Murine Double Minute 2 Degrader Capable of Achieving Complete and Durable Tumor Regression. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 448–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Tandon, I.; Wu, S.; Teng, P.; Liao, J.; Tang, W. Development of MDM2 degraders based on ligands derived from Ugi reactions: Lessons and discoveries. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 219, 113425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, R.R.; Popovic-Nikolicb, M.R.; Nikolic, K.; Uliassi, E.; Bolognesi, M.L. A perspective on multi-target drug discovery and design for complex diseases. Clin. Transl. Med. 2018, 7, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Huo, J.; Gu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; et al. Rational Design and Synthesis of Novel Dual PROTACs for Simultaneous Degradation of EGFR and PARP. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 7839–7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabizon, R.; London, N. The rise of covalent proteolysis targeting chimeras. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2021, 62, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiely-Collins, H.; Winter, G.E.; Bernardes, G.J. The role of reversible and irreversible covalent chemistry in targeted protein degradation. Cell Chem. Biol. 2021, 28, 952–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontermann, R. Dual targeting strategies with bispecific antibodies. Mabs 2012, 4, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotton, A.D.; Nguyen, D.P.; Gramespacher, J.A.; Seiple, I.B.; Wells, J.A. Development of Antibody-Based PROTACs for the Degradation of the Cell-Surface Immune Checkpoint Protein PD-L1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.; Ehmann, R.; Smith, G.L. Smallpox in the Post-Eradication Era. Viruses 2020, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trilla, A.; Trilla, G.; Daer, C. The 1918 “Spanish Flu” in Spain. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 47, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Su, S.; Yang, H.; Jiang, S. Antivirals with common targets against highly pathogenic viruses. Cell 2021, 184, 1604–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, L.B.; Chomont, N.; Deeks, S.G. The Biology of the HIV-1 Latent Reservoir and Implications for Cure Strategies. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morens, D.M.; Fauci, A.S. Emerging Pandemic Diseases: How We Got to COVID-19. Cell 2020, 182, 1077–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Huang, T.; Song, L.; Xu, S.; Cheng, Y.; Cherukupalli, S.; Kang, D.; Zhao, T.; Sun, L.; Zhang, J.; et al. Medicinal chemistry strategies towards the development of effective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Clercq, E. Fifty Years in Search of Selective Antiviral Drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 7322–7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, P.; Pannecouque, C.; De Clercq, E.; Liu, X. Anti-HIV Drug Discovery and Development: Current Innovations and Future Trends. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 2849–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Frutos-Beltrán, E.; Kang, D.; Pannecouque, C.; De Clercq, E.; Menéndez-Arias, L.; Liu, X.; Zhan, P. Medicinal chemistry strategies for discovering antivirals effective against drug-resistant viruses. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 4514–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, M.J. Recent Advances in Vaccine Technologies. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2018, 48, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dane, D.S.; Dick, G.W.A.; Briggs, M.; Nelson, R. Vaccination Against Poliomyelitis with Live Virus Vaccines. 5. Neutralizing anti body levels one year after vaccination. Br. Med. J. 1958, 2, 1187–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.I.; Cordeiro, M.; Sevilla, E.; Liu, J. Comparison of egg and high yielding MDCK cell-derived live attenuated influenza virus for commercial production of trivalent influenza vaccine: In vitro cell susceptibility and influenza virus replication kinetics in permissive and semi-permissive cells. Vaccine 2010, 28, 3848–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pica, N.; Palese, P. Toward a Universal Influenza Virus Vaccine: Prospects and Challenges. Annu. Rev. Med. 2013, 64, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; Shen, Q.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Shen, J.; Xiao, X.; Bai, H.; Feng, T.; Ye, A.Y.; Le Li, L.; et al. Generation of a live attenuated influenza A vaccine by proteolysis targeting. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wispelaere, M.; Du, G.; Donovan, K.A.; Zhang, T.; Eleuteri, N.A.; Yuan, J.C.; Kalabathula, J.; Nowak, R.P.; Fischer, E.S.; Gray, N.S.; et al. Small molecule degraders of the hepatitis C virus protease reduce susceptibility to resistance mutations. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Horby, P.W.; Hayden, F.G.; Gao, G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020, 395, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, S.A.; Banerjee, S.; Ghosh, K.; Gayen, S.; Jha, T. Protease targeted COVID-19 drug discovery and its challenges: Insight into viral main protease (Mpro) and papain-like protease (PLpro) inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 29, 115860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liang, C.; Xin, L.; Ren, X.; Tian, L.; Ju, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, H.; et al. The development of Coronavirus 3C-Like protease (3CLpro) inhibitors from 2010 to 2020. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 206, 112711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y. Sialobiology of Influenza: Molecular Mechanism of Host Range Variation of Influenza Viruses. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 28, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, D.; Revol, R.; Östbye, H.; Wang, H.; Daniels, R. Influenza A Virus Cell Entry, Replication, Virion Assembly and Movement. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, H.T.; Gallop, J.L. Membrane curvature and mechanisms of dynamic cell membrane remodelling. Nature 2005, 438, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.; Garcea, R.L.; Grigorieff, N.; Harrison, S.C. Subunit interactions in bovine papillomavirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6298–6303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Ma, X.; Zou, W.; Chen, Q.; Chen, F.; Deng, X.; Liang, J.; Dong, C.; Lan, K.; et al. Discovery of oseltamivir-based novel PROTACs as degraders targeting neuraminidase to combat H1N1 influenza virus. Cell Insight 2022, 1, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Structure, Function, and Evolution of Coronavirus Spike Proteins. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2016, 3, 237–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, T.; Peng, H.; Sterling, S.M.; Jr, R.M.W.; Rawson, S.; Rits-Volloch, S.; Chen, B. Distinct conformational states of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Science 2020, 369, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervushin, K.; Tan, E.; Parthasarathy, K.; Lin, X.; Jiang, F.L.; Yu, D.; Vararattanavech, A.; Soong, T.W.; Liu, D.X.; Torres, J. Structure and Inhibition of the SARS Coronavirus Envelope Protein Ion Channel. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.-Y.; Li, J.-L.; Yang, X.-L.; Chmura, A.A.; Zhu, G.; Epstein, J.H.; Mazet, J.K.; Hu, B.; Zhang, W.; Peng, C.; et al. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2013, 503, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Kumar, R.; Singh, J.; Dhanda, S. In silico molecular docking of SARS-CoV-2 surface proteins with microbial non-ribosomal peptides: Identification of potential drugs. J. Proteins Proteom. 2021, 12, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhong, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Li, M.; Li, X.; et al. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 766–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Komoto, J.; Watanabe, K.; Ohmiya, Y.; Takusagawa, F. Crystal Structure and Possible Catalytic Mechanism of Microsomal Prostaglandin E Synthase Type 2 (mPGES-2). J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 348, 1163–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.E.; Jang, G.M.; Bouhaddou, M.; Xu, J.; Obernier, K.; White, K.M.; O’Meara, M.J.; Rezelj, V.V.; Guo, J.Z.; Swaney, D.L.; et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature 2020, 583, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terracciano, R.; Preianò, M.; Fregola, A.; Pelaia, C.; Montalcini, T.; Savino, R. Mapping the SARS-CoV-2–Host Protein–Protein Interactome by Affinity Purification Mass Spectrometry and Proximity-Dependent Biotin Labeling: A Rational and Straightforward Route to Discover Host-Directed Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desantis, J.; Mercorelli, B.; Celegato, M.; Croci, F.; Bazzacco, A.; Baroni, M.; Siragusa, L.; Cruciani, G.; Loregian, A.; Goracci, L. Indomethacin-based PROTACs as pan-coronavirus antiviral agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 226, 113814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Chamorro, L.; Felip, E.; Ezeonwumelu, I.J.; Margelí, M.; Ballana, E. Cyclin-dependent Kinases as Emerging Targets for Developing Novel Antiviral Therapeutics. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, F.; Hamilton, S.T.; Wangen, C.; Wild, M.; Kicuntod, J.; Brückner, N.; Follett, J.E.L.; Herrmann, L.; Kheimar, A.; Kaufer, B.B.; et al. Development of a PROTAC-Based Targeting Strategy Provides a Mechanistically Unique Mode of Anti-Cytomegalovirus Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S. Hepatitis B Virus X Protein: Structure, Function and Biology. Intervirology 1999, 42, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feitelson, M.A.; Duan, L.X. Hepatitis B virus X antigen in the pathogenesis of chronic infections and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 1997, 150, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Montrose, K.; Krissansen, G.W. Design of a PROTAC that antagonizes and destroys the cancer-forming X-protein of the hepatitis B virus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 453, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landesman, S.H.; Ginzburg, H.M.; Weiss, S. The AIDS Epidemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985, 312, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, B.G.; Summers, M.F. Structural biology of HIV. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 285, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yuan, S.; Xu, S.; Guo, D.; Chen, L.; Hou, W.; Wang, M. Suppression of HIV-1 Integration by Targeting HIV-1 Integrase for Degradation with A Chimeric Ubiquitin Ligase. Virol. Sin. 2021, 36, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiedel, M.; Herp, D.; Hammelmann, S.; Swyter, S.; Lehotzky, A.; Robaa, D.; Oláh, J.; Ovádi, J.; Sippl, W.; Jung, M. Chemically Induced Degradation of Sirtuin 2 (Sirt2) by a Proteolysis Targeting Chimera (PROTAC) Based on Sirtuin Rearranging Ligands (SirReals). J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Bendjennat, M.; Kour, S.; King, H.M.; Kizhake, S.; Zahid, M.; Natarajan, A. Selective degradation of CDK6 by a palbociclib based PROTAC. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 1375–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crew, A.P.; Raina, K.; Dong, H.; Qian, Y.; Wang, J.; Vigil, D.; Serebrenik, Y.V.; Hamman, B.D.; Morgan, A.; Ferraro, C.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Von Hippel-Lindau-Recruiting Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) of TANK-Binding Kinase 1. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Hu, J.; Xu, F.; Chen, Z.; Bai, L.; Fernandez-Salas, E.; Lin, M.; Liu, L.; Yang, C.-Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Discovery of a Small-Molecule Degrader of Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal (BET) Proteins with Picomolar Cellular Potencies and Capable of Achieving Tumor Regression. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 462–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Cao, P.; Gao, Y.; Wu, M.; Lin, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, W. Differential expression of p38 MAPK α, β, γ, δ isoforms in nucleus pulposus modulates macrophage polarization in intervertebral disc degeneration. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burslem, G.M.; Schultz, A.R.; Bondeson, D.P.; Eide, C.A.; Stevens, S.L.S.; Druker, B.J.; Crews, C.M. Targeting BCR-ABL1 in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia by PROTAC-Mediated Targeted Protein Degradation. Cancer Res 2019, 79, 4744–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burslem, G.M.; Song, J.; Chen, X.; Hines, J.; Crews, C.M. Enhancing Antiproliferative Activity and Selectivity of a FLT-3 Inhibitor by Proteolysis Targeting Chimera Conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 16428–16432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yewdell, J.W.; Reits, E.; Neefjes, J. Making sense of mass destruction: Quantitating MHC class I antigen presentation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 3, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, S.; Setz, C.; Wild, J.; Schubert, U. The PTAP Sequence within the p6 Domain of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Gag Regulates Its Ubiquitination and MHC Class I Antigen Presentation. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 5706–5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Ortiz, W.; Zhou, M.-M. Could PROTACs Protect Us From COVID-19? Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 1894–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.-J.; Crank, M.C.; Shiver, J.; Graham, B.S.; Mascola, J.R.; Nabel, G.J. Next-generation influenza vaccines: Opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, Y.; Xia, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.P.; Wei, W. PROTACs: A novel strategy for cancer therapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 67, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Zhang, X.; Lv, D.; Zhang, Q.; He, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X.; Thummuri, D.; Yuan, Y.; Wiegand, J.S.; et al. A selective BCL-XL PROTAC degrader achieves safe and potent antitumor activity. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1938–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, K.; Coen, M.; Zhang, A.X.; Pachl, F.; Castaldi, M.P.; Dahl, G.; Boyd, H.; Scott, C.; Newham, P. Proteolysis-targeting chimeras in drug development: A safety perspective. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 1709–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebraud, H.; Wright, D.J.; Johnson, C.N.; Heightman, T.D. Protein Degradation by In-Cell Self-Assembly of Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costales, M.G.; Matsumoto, Y.; Velagapudi, S.P.; Disney, M.D. Small Molecule Targeted Recruitment of a Nuclease to RNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6741–6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, A.; Jha, B.K.; Silverman, R.H. New insights into the role of RNase L in innate immunity. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011, 37, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).