Abstract

The geomagnetic field (GMF) is crucial for the survival and evolution of life on Earth. The weakening of the GMF, known as the hypomagnetic field (HMF), significantly affects various aspects of life on Earth. HMF has become a potential health risk for future deep space exploration. Oxidative stress is directly involved in the biological effects of HMF on animals or cells. Oxidative stress occurs when there is an imbalance favoring oxidants over antioxidants, resulting in cellular damage. Oxidative stress is a double-edged sword, depending on the degree of deviation from homeostasis. In this review, we summarize the important experimental findings from animal and cell studies on HMF exposure affecting intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), as well as the accompanying many physiological abnormalities, such as cognitive dysfunction, the imbalance of gut microbiota homeostasis, mood disorders, and osteoporosis. We discuss new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying these HMF effects in the context of the signaling pathways related to ROS. Among them, mitochondria are considered to be the main organelles that respond to HMF-induced stress by regulating metabolism and ROS production in cells. In order to unravel the molecular mechanisms of HMF action, future studies need to consider the upstream and downstream pathways associated with ROS.

1. Introduction

The geomagnetic field (GMF) is crucial for the survival and evolution of life on Earth because it protects against atmospheric escape, solar wind, and cosmic rays. The elimination of the GMF, known as the hypomagnetic field (HMF), poses risks for astronauts during deep space exploration, as well as for all life during geomagnetic reversals. Paleomagnetic studies have indicated that during reversals, the dipole field strength can decrease by up to 90% at Earth’s surface. This weakens the protection of the GMF, leading to increased radiation on the surface of Earth, exposing all life to the HMF and a strong radiation environment for thousands of years [1,2,3]. The change in Earth’s environment has a profound impact on the evolution and survival of living organisms. Therefore, the role of the GMF on life is composed of two different scales: The GMF’s impact on the origins and evolution of life on Earth and its influence on living organisms’ physiology and behaviors. Although the evolutionary effect of GMF reversals on life is still not fully understood, major variations in the GMF correlate with major geological and biological processes [4,5]. As we look towards future space exploration, astronauts will encounter extremely weak magnetic field conditions, such as in interstellar space (2–8 nT), on the Moon (9–300 nT), and on Mars (10 nT–5 µT) [6,7,8]. These weak magnetic fields could have a negative impact on astronauts’ health. In this article, we focus on the influence of the elimination of GMF on various aspects of animals’ health. Numerous studies have shown that HMF exposure causes many adverse biological effects at both a cellular and organism levels, with changes in the intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) often occurring in response to HMF exposure [9,10,11].

ROS belong to a large group of oxidants derived from molecular oxygen [12,13]. Oxidative stress occurs when there is an imbalance favoring oxidants over antioxidants, leading to redox signaling disruption and/or molecular damage. In recent years, with a better understanding of the roles of different ROS in cells, “oxidative stress” has come to encompass two meanings: elevated levels of ROS cause molecular damage, known as ‘oxidative stress’, and physiological levels of ROS play key roles in redox signaling through post-translational modifications, known as ‘oxidative eustress’ [14,15]. ROS are essential for cellular signaling and response to stress, which contribute to both physiological and pathological conditions. Moderate ROS levels serve as signaling molecules and are essential for cellular functions and various pathologies [16]. ROS assist the host in combating micro-organisms and also participate in intermicrobial competition. For instance, mouse peritoneal macrophages can be stimulated to release H2O2 against micro-organisms into the extracellular medium [17], while excess ROS levels incur damage to DNA, protein, or lipids, widely associated with dysfunction and disease. The interaction of ROS with nitrogenous bases and deoxyribose results in significant oxidative DNA damage, leading to mutations, carcinogenesis, apoptosis, necrosis, and hereditary diseases [18]. Most cancers are believed to have a direct connection to ROS-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. This direct relationship between ROS and cancer has also been identified in other conditions, such as Alzheimer’s and Type 2 diabetes [19]. Research indicates that HMFs have a significant impact on cellular ROS levels, altering physiological and biological processes in organisms [20,21]. Signaling pathways associated with ROS regulation may be linked to many biological effects caused by HMF exposure. Here, we outline the upstream and downstream signaling pathways of ROS and propose the possible molecular mechanisms underlying the HMF action.

2. Types of ROS

ROS encompass molecules derived from O2, including superoxide (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (•OH). Superoxide dismutases (SODs) catalyze the dismutation of O2•− to H2O2. H2O2 is reduced by many kinds of enzymes (antioxidants), including catalase, peroxiredoxins (PRDXs), glutathione peroxidases (GPXs), and other peroxidases (cytochrome c). Catalase is one of the key antioxidant enzymes that destroys cellular hydrogen peroxide to produce water and oxygen to relieve oxidative stress [22]. O2•− can damage various cellular components and indirectly affect signaling pathways [18,23]. H2O2 serves as a signaling molecule through the reversible oxidation of cysteine residues within proteins, which is involved in redox signaling at specific concentrations. For example, the thiolate anion of cysteine residues is oxidized to sulfenic form (Cys-SOH) by low levels of H2O2, which alters the function of protein during redox signaling [24,25], while higher levels of H2O2 further oxidize thiolate anions to sulfinic (SO2H) or sulfonic (SO3H) species to cause permanent protein damage [18]. The most harmful effect of H2O2 is its reaction with transition metals such as ferrous iron (Fe2+) to produce hydroxyl radicals (•OH), known as the Fenton reaction. •OH is a powerful oxidant that indiscriminately oxidizes lipids, proteins, and DNA, causing significant damage and genomic instability. In addition, other oxygen-containing free radicals can also cause oxidation of essential cellular components, including peroxynitrite, lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH), alkoxyl radical (RO•), peroxyl radical (ROO•), sulfate radical (SO4•−), and Fenton reaction intermediates [26,27]. Here, we mainly discuss two types of ROS involved in the biological effects of HMF: O2•− and H2O2.

3. ROS Homeostasis

ROS levels are strictly controlled by multiple ROS-generating and ROS-eliminating systems, which actively maintain the intracellular redox state in cells. Production of O2•− is primarily from the mitochondrial respiratory chain and the NADPH oxidases (NOXs) in cells. NOXs are transmembrane enzymes responsible for the production of O2•− via electron transfer across membranes from NAD(P)H to molecular oxygen [28]. NOXs produce superoxide primarily on the intracellular side of membranes. The human NOXs family consists of Nox1–5, Duox1, and Duox2. The classic activity control of Nox enzymes is exerted by calcium or protein–protein interactions and post-translational modifications (PTMs). Phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, and glycosylation are the most studied PTMs in cells. The activities of Nox5 and the Duox enzymes are calcium-dependent, and the activity controls of Nox1, Nox2, and Nox3 are regulated through interactions with the cytosolic proteins, such as the small GTPase Rac [29]. Interactions between different oxidases or oxidase systems play key roles in oxidative stress. Activation of NOX induces activation of downstream secondary oxidase systems, including uncoupled endothelial nitric oxide synthase and xanthine oxidase [30].

Mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) complexes I and III are the main sites of O2•− production where the leaking O2 is reduced to O2•−. The NADH and FADH2 donate electrons to the ETC. Thus, the ratio of NADH to NAD+ regulates O2•− production [22,31]. Therefore, there is a close relationship between mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) generated by the ETC. The mtROS production depends on the metabolic state of mitochondria in cells [32]. In response to the electron transport, protons (H+) are pumped from the matrix into the intermembrane space to form mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). ATP synthase uses the energy of proton gradient to produce ATP. However, uncoupling proteins (UCPs) break the perfect coupling between proton gradient and ATP synthase, mediating a small amount of H+ to flow into the matrix to reduce ATP synthesis. Therefore, UCPs are able to reduce the efficiency of OXPHOS, thereby reducing ROS production [33]. Other than mitochondria and NOXs, other sources of ROS production include xanthine oxidase (XO) and cyclooxygenases (COXs) [34].

ROS are counterbalanced by antioxidant networks, which modulate ROS levels to allow their physiological roles. ROS-eliminating systems and antioxidants include GPXs, thioredoxin peroxidases (TRXPs), SODs, PRDXs, glutathione (GSH), thioredoxin 2 (TRX2), glutaredoxin 2 (GRX2), ascorbic acid, tocopherol, vitamin E, and carotene [35]. For example, SODs convert O2•− to H2O2, which can then be converted by catalase to harmless H2O [32,36].

4. Changes in Cellular ROS Levels Caused by HMF

The effects of HMF on living organisms are diverse, including different effects ranging from cells, tissues, and organs to organisms. For instance, HMF has significant negative effects on early development, circadian rhythms, and the central nervous system in animals [9,37]. However, the mechanisms underlying these effects are still not well understood. Here, we summarize published studies on the effects of HMFs on ROS within animal cells or organisms (Table 1), excluding studies on plants or micro-organisms. HMF generally reduced H2O2 levels within cells, accompanied by changes in cell behavior and gene expression in in vitro studies (Table 1). HMF in the range of 0.2–0.5 μT inhibited the proliferation and eNOS expression in endothelial cells [38], while HMFs (0.5–2 μT) suppressed H2O2 production in cancer cells and bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAEC). This effect can be inhibited by antioxidants like catalase and SOD mimetic MnTBAP [39]. HMF (<0.2 μT) reduced H2O2 levels in human neuroblastoma cells by inhibiting the activity of CuZn-SOD, and the enhanced cell proliferation caused by HMF can be remedied by additional H2O2 supplementation [40]. HMF (20 nT) also reduced ROS production in mice peritoneal neutrophils by affecting NOX activity and mitochondrial ETC [41,42]. However, an in vitro study of mouse skeletal muscle cells showed that HMF (<3 μT) could cause an increase in its ROS levels, leading to a decrease in cell function [43].

Table 1.

ROS changes caused by HMF at cellular level.

As shown in Table 2, we have found that HMF (0.29 ± 0.01 μT) reduced endogenous ROS in adult hippocampal neural stem cells, further affecting cognitive function of the hippocampus in mice [11]. ROS levels are tightly controlled by an inducible antioxidant program that responds to cellular stressors. Further, in vivo research on other hippocampal cells in the mouse hippocampus revealed that HMF (31.9 ± 4.5 nT) significantly increased its ROS levels by decreasing the expression of antioxidant genes, which may cause oxidative stress damage to the overall hippocampus and further affect anxiety and cognitive behavior in mice [44,45]. HMF can cause bone loss in mammals. For instance, HMF (<300 nT) promotes additional bone loss in the mouse femur during mechanical unloading, likely due to iron overload, exacerbating oxidative stress and thereby inhibiting osteoblast activity [46,47]. Other research showed that under particular conditions of oxidative stress, HMF (0.192 μT) could disrupt the functional state of erythrocytes and promote cell death in rats [48]. In addition, neuroinflammation regulates stem cell niches, particularly neural stem/progenitor cells in mammals. We have found that HMF (31.1 ± 2.0 nT) may also cause neuroinflammation in the hippocampus of mice, manifested by the activation of microglia and upregulation of GFAP expression in astrocytes [49]. This may be closely related to the increase in ROS in hippocampal cells [44,45]. In the biological effects of HMF, changes in ROS levels in cells are often accompanied by changes in cell number, proliferation, and survival; changes in the expression level of antioxidant genes; and even behavioral abnormalities, such as a decline in cognitive and orientation abilities, in animals (Table 1 and Table 2). The different results of HMF affecting ROS levels may be related to the differences in magnetic strength, duration of exposure, cell type, or method of HMF generation.

Table 2.

ROS changes caused by HMF at organism level.

5. ROS-Mediated Signaling Pathways and Potential Links to HMF Effects

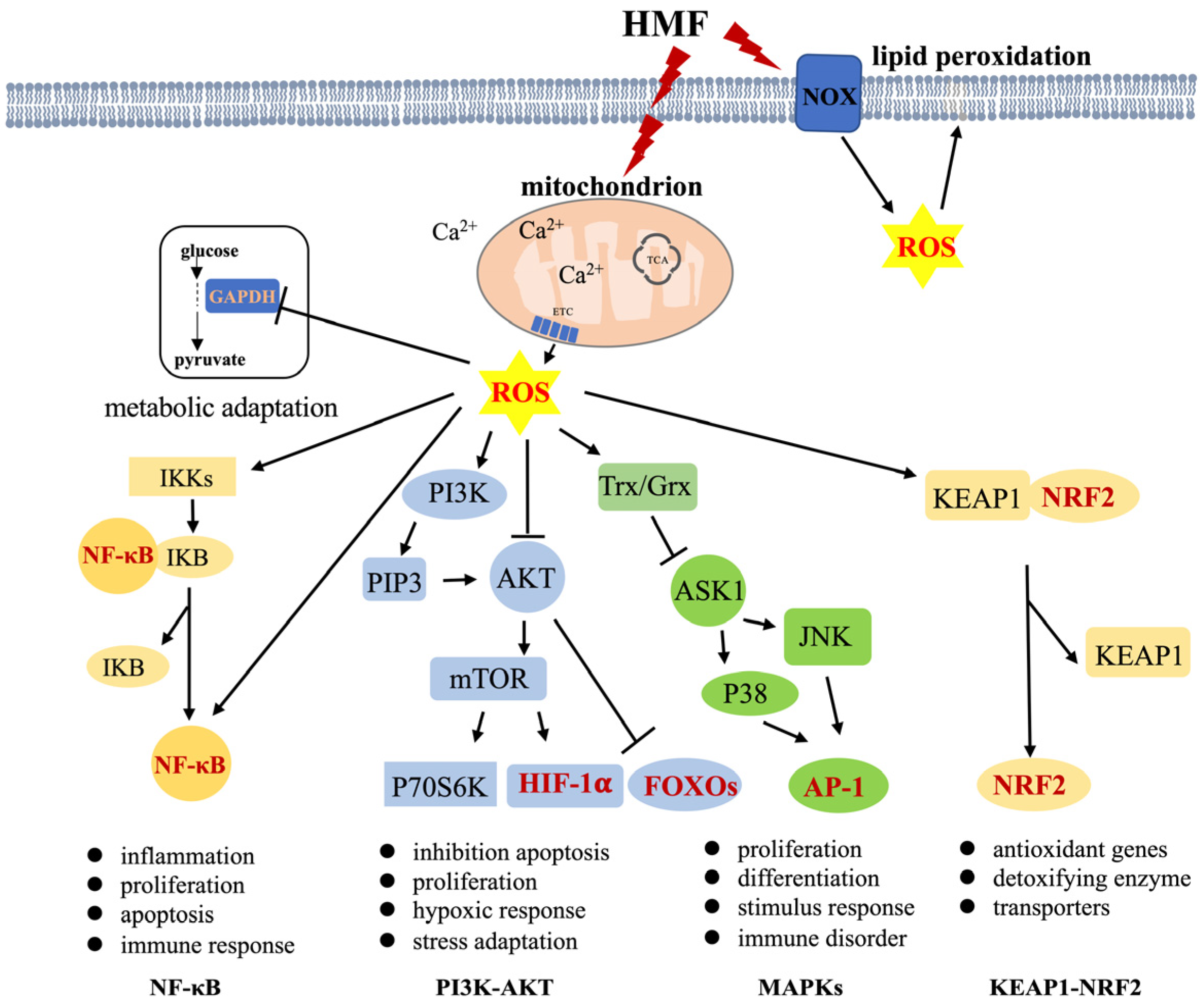

ROS have beneficial or harmful effects depending on their local concentration in a cell. Suitable levels of ROS are involved in numerous crucial physiological processes, including proliferation, differentiation, metabolic adaptation, and the regulation of adaptive and innate immunity. However, excess ROS can be harmful to maintaining cellular redox homeostasis, inevitably causing damage to macromolecules or inducing cell death. which contributes to the development of many diseases, such as hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer, neurodegeneration, and aging [15,18]. The possible signaling pathways mediated by ROS are nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt pathways, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)s, and Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathways, which regulate various physiological/pathological functions, including cell proliferation and differentiation, growth and apoptosis, and the response to external stress and inflammation (Figure 1) [53,54,55,56]. Moderate elevations of H2O2 mediate GAPDH oxidation in glycolysis, and the inactivation of GAPDH stimulates the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway of glucose. ROS as pleiotropic physiological signaling agents are thoroughly summarized in two recent papers [15,57]. The following are brief summaries concerning signaling pathways mediated by ROS (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

ROS-regulated signaling pathways. ROS act as second messengers to regulate four main signaling pathways, controlling a variety of biological processes in cells. Mitochondria and NOXs are the two main sources of ROS generation (black arrows: activation; black T-arrows: inhibition). Dark red font represents the transcription factors. TCA: tricarboxylic acid cycle, ETC: electron transport chain, AP-1: activator protein-1.

(1) The transcription factor NF-κB regulates the expression of various inflammatory genes and mediates the inflammatory response to stressful stimuli. The activation of NF-κB involves two major signaling pathways — the canonical and noncanonical pathways—which are important for regulating immune and inflammatory responses [58]. In addition, NF-κB plays a critical role in regulating the survival, activation, and differentiation of innate immune cells and inflammatory T cells. NF-κB activity influences ROS levels by regulating the expression of antioxidant (SOD2) or pro-ROS enzymes, while ROS have various inhibitory or stimulatory roles in NF-κB signaling in a context-dependent manner [59,60]. ROS has been shown to regulate the upstream NF-κB activating pathways; for example, ROS activates NF-κB through alternative IκBα phosphorylation in IKKs [61], and H2O2 markedly decreased the ability of TNF to induce IKK activity, resulting in the prevention of I-κB degradation and NF-κB activation [62]. Meanwhile, sustained oxidative stress may lead to the inactivation of the proteasome and subsequently inhibit NF-κB activation by impeding the degradation of I-κB [63]. mtROS are intermediates that trigger inflammatory signaling cascades, which enable proinflammatory signaling by inducing the disulfide linkage of NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO). This bond is essential for activating the NF-κB and MAPK pathways and leading to proinflammatory cytokine secretion [64]. Both mtDNA and mtROS from dysfunctional mitochondria can drive IL-1β and IL-18 secretion as a consequence of inflammasome signaling [54]. Direct or indirect oxidation of NF-κB heterodimers by ROS inhibits its DNA binding ability or activates the interaction of RelA with CBP/300 [65,66]. NF-κB also regulates some enzymes that promote the production of ROS in immune cells [67,68,69]. Moreover, NF-κB signaling crosstalk influences various signaling pathways, including STAT3, AP1, interferon regulatory factors, NRF2, Notch, WNT–β-catenin, and p53 [59,70,71,72]. Kim et al. reported that H2O2 modulates IKK-dependent NF-kB activation by promoting the redox-sensitive activation of the PI3K/PTEN/Akt and NIK/IKK pathways [73]. There is an extremely close relationship between the NF-κB signaling pathway, ROS-generating enzymes, and antioxidant enzymes in inflammation-related injuries and diseases. The activation of NF-κB is a key link in the inflammatory response, which mediates IL-1 β, TNF-α, and iNOS expression [74,75,76]. Inhibiting the activation of NOXs can inhibit NF-κB activation to alleviate inflammation [77,78,79,80].

(2) PI3K/AKT pathway is downstream of the EGFR/HER family and upstream of mTOR. It regulates various cellular activities, such as cell cycle progression and cancer onset. PI3K/AKT signaling can be regulated by ROS in a concentration-dependent manner. Chen et al. showed that excess ROS hinder the PI3K/AKT pathway, causing apoptosis and inflammation in corneal epithelial cells (CECs). However, at the appropriate level, ROS activate PI3K/AKT signaling, inhibiting apoptosis and promoting the proliferation of CECs [81]. For instance, ROS can inactivate PTEN by oxidizing the active site cysteine residues, which upregulates the PI3K/AKT pathway [82]. These are responsible for negatively regulating PIP3 synthesis, thereby inhibiting Akt activation by oxidizing cysteine residues inside the active center [83,84]. In addition, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) can regulate cell adaptation to hypoxia and other stimulators. Tian et al. showed that the PI3K/AKT pathway can upregulate the expression of HIF1α in breast cancer cells [85]. Forkhead box O (FOXO) members in humans are modulated by the PI3K/AKT pathway, which predominately responds to stress conditions [86,87].

(3) The MAPK pathways are important bridges in the switch from extracellular signals to intracellular responses, regulating processes like cell proliferation, differentiation, survival, cancer dissemination, and resistance to drug therapy. There are three main MAPK cascades: extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK), and p38 kinase (p38). MAPK, MAPKK, and MAP3K (also known as ASK1) are classic protein kinases in each cascade [88]. Reduced thioredoxin (Trx) is a key negative regulator of ASK1 kinase activity. Trx contains Cys32 and Cys35 cysteine residues in its active site. In response to oxidative stress, H2O2 oxidizes these cysteine residues, leading to the release of Trx, which is required for the kinase activity of ASK1. TNF receptor-associated factor (TRAF)2 and TRAF6 are then recruited to the ASK1 signalosome, resulting in the activation of the JNK and p38 MAPK pathways [89,90].

(4) NRF2-KEAP1 plays a crucial role in maintaining redox homeostasis and metabolism in cells. NRF2 is an important transcription factor for the expression of antioxidant proteins, protecting cells from oxidative damage. Meanwhile, KEAP1 serves as a negative regulator of NRF2 by binding to the Neh2 domain of NRF2 [91]. Evidence indicates that under stress conditions, ROS directly oxidizes KEAP1-cystines, leading to its dissociation and NRF2 translocation to the nucleus to regulate the genes of antioxidants [89,91].

These pathways regulate various downstream physiological and pathological functions. ROS, especially H2O2, can act as a second messenger or damaging oxidative stress, triggering some key signaling pathways through interaction with critical signaling molecules to regulate many downstream cascade events. This results in various physiological effects and behavioral abnormalities, such as cognitive dysfunction and anxiety in animals exposed to HMF. We suggest that understanding the relationship between these signaling pathways and HMF exposure is key to uncovering the molecular mechanisms underlying these biological effects.

Research has shown that HMF affects the mitochondria and NOXs, which are responsible for producing ROS. HMF exposure also leads to reduced mitochondrial ΔΨm, decreased ATP production and mitochondria activity, elevated ROS levels, and disrupted Ca2+ balance in cells (Table 1 and Figure 1). Under oxidative stress, ROS, especially H2O2, activate signaling pathways to initiate biological processes, while high levels of ROS result in damage to DNA, protein, or lipids. These effects are closely linked to cellular mitochondrial dysfunction [43,49,92,93]. PGC-1α, a regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and an important inducer of antioxidant gene expression during oxidative stress, has been found to significantly reduce in expression levels due to HMF exposure, with a decrease in the number of active mitochondria in the hippocampus [45]. Low PGC-1α expression inhibits the induction of various ROS-detoxifying enzymes, resulting in increased ROS levels [94]. As a result, we propose that mitochondria are considered to be the primary organelles responding to HMF-induced stress by regulating the metabolism and ROS production in cells. We speculate that the shift between glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation is a response to HMF. Although it is still unclear how HMF affects ROS production by regulating upstream signals, we speculate that certain molecules/ions (e.g., Ca2+) within cells or organelles may sense HMF as an external environmental stimulus, leading to changes in NOXs activity or mitochondrial dynamics and function, ultimately affecting cellular ROS levels. ROS serves as a second messenger or causes oxidative stress, triggering key signaling pathways or oxidative damage to macromolecules, resulting in a series of downstream cascades (Figure 1). However, the question of which biological effects caused by HMF are regulated by ROS-regulated signaling pathways still needs experimental verification. Additionally, N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) or γ-glutamylcysteine (γGC) can be attempted to relieve oxidative stress and mitigate the negative effects of HMF. For example, NF-κB can be activated by high levels of H2O2, and this activation is blocked by treating the cells with the anti-oxidant NAC [95,96] and γGC, as a precursor to GSH, which may increase GSH levels in healthy subjects, suggesting its potential to detoxify H2O2 in a GPX1-dependent manner [97,98].

6. Conclusions

HMF has been found to cause cognitive dysfunction, anxiety-related behaviors, circadian disorders, gut dysbiosis, reproductive and developmental abnormalities, and osteoporosis in animals [37]. These functional abnormalities in animals may be linked to cellular-level effects caused by HMF. For example, HMF inhibited adult hippocampal neurogenesis, led to high ROS levels and inflammation in the hippocampus, and altered the concentrations of melatonin and norepinephrine in animals. These effects may collectively contribute to cognitive impairment in the animals. HMF also leads to osteoporosis by inhibiting osteoblast differentiation and mineralization. ROS may play key roles in the regulatory mechanisms behind these HMF effects through one or more signaling pathways. However, the question of which biological effects caused by HMF are regulated by ROS-regulated signaling pathways needs to be confirmed in future studies. Mitochondria are considered to be the primary organelles responding to HMF-induced stress. Changes in NOX activity and mitochondrial dynamics and function caused by HMF affect the cellular ROS level. H2O2 acts as a second messenger molecule or oxidative stress, leading to a series of downstream cascades. To reveal the molecular mechanism of HMF effects, the upstream and downstream pathways related to ROS need to be considered in future studies. Therapeutic methods targeting oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction could be developed to mitigate the negative effects of HMF in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T.; writing—review and editing, L.T., Y.L., J.R. and C.Z.; visualization, L.T. and Y.L.; supervision, L.T.; project administration, L.T.; funding acquisition, L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers 42388101 and 42274099, and the CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research, grant number YSBR-097.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Juan Wan for the helpful discussion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tarduno, J.A.; Blackman, E.G.; Mamajek, E.E. Detecting the oldest geodynamo and attendant shielding from the solar wind: Implications for habitability. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2014, 233, 68–87. [Google Scholar]

- Valet, J.P.; Meynadier, L.; Guyodo, Y. Geomagnetic dipole strength and reversal rate over the past two million years. Nature 2005, 435, 802–805. [Google Scholar]

- Gubbins, D. Earth science: Geomagnetic reversals. Nature 2008, 452, 165–167. [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann, W.; Kmita, H.; Kosicki, J.Z.; Kaczmarek, L. How the Geomagnetic Field Influences Life on Earth-An Integrated Approach to Geomagnetobiology. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 2021, 51, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.X.; Li, J.H. On the biospheric effects of geomagnetic reversals. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.P.; Mitchell, D.L.; Curtis, D.W.; Anderson, K.A.; Carlson, C.W.; McFadden, J.; Acuña, M.H.; Hood, L.L.; Binder, A. Lunar surface magnetic fields and their interaction with the solar wind: Results from lunar prospector. Science 1998, 281, 1480–1484. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhilber, F.; Abreu, J.A.; Beer, J.; McCracken, K.G. Interplanetary magnetic field during the past 9300 years inferred from cosmogenic radionuclides. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2010, 115, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, A.M.; Ge, Y.S.; Wang, H.P.; Li, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, H.; Huang, C.; Shan, L.C.; Han, F.; Liu, Y.; et al. Ground magnetic survey on Mars from the Zhurong rover. Nat. Astron. 2023, 7, 1037–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Binhi, V.N.; Prato, F.S. Biological effects of the hypomagnetic field: An analytical review of experiments and theories. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binhi, V.N.; Rubin, A.B. Theoretical Concepts in Magnetobiology after 40 Years of Research. Cells 2022, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.F.; Wang, L.; Zhan, A.S.; Wang, M.; Tian, L.X.; Guo, W.X.; Pan, Y.X. Long-term exposure to a hypomagnetic field attenuates adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognition. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sies, H. Oxidative Stress; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sies, H. Oxidative stress: A concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 180–183. [Google Scholar]

- Sies, H.; Belousov, V.V.; Chandel, N.S.; Davies, M.J.; Jones, D.P.; Mann, G.E.; Murphy, M.P.; Yamamoto, M.; Winterbourn, C. Defining roles of specific reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cell biology and physiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 499–515. [Google Scholar]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar]

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative Stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–748. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan, C.F.; Root, R.K. Hydrogen peroxide release from mouse peritoneal macrophages: Dependence on sequential activation and triggering. J. Exp. Med. 1977, 146, 1648–1662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS Function in Redox Signaling and Oxidative Stress. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R453–R462. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Vegas, A.; Sanchez-Aguilera, P.; Krycer, J.R.; Morales, P.E.; Monsalves-Alvarez, M.; Cifuentes, M.; Rothermel, B.A.; Lavandero, S. Is Mitochondrial Dysfunction a Common Root of Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases? Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, 491–517. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.Z.; Zhang, X. Magnetic Fields and Reactive Oxygen Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.F.; Tian, L.X. Reactive Oxygen Species: Potential Regulatory Molecules in Response to Hypomagnetic Field Exposure. Bioelectromagnetics 2020, 41, 573–580. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009, 417, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Azad, M.B.; Gibson, S.B. Superoxide is the major reactive oxygen species regulating autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2009, 16, 1040–1052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rhee, S. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science 2006, 312, 1882–1883. [Google Scholar]

- Winterbourn, C.C.; Hampton, M.B. Thiol chemistry and specificity in redox signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 549–561. [Google Scholar]

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species (Ros) and Ros-Induced Ros Release. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 909–950. [Google Scholar]

- Radi, R. Oxygen radicals, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite: Redox pathways in molecular medicine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 5839–5848. [Google Scholar]

- Bedard, K.; Krause, K.H. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: Physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 245–313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brandes, R.P.; Weissmann, N.; Schröder, K. Nox family NADPH oxidases: Molecular mechanisms of activation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 76, 208–226. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Murugesan, P.; Huang, K.; Cai, H. NADPH oxidases and oxidase crosstalk in cardiovascular diseases: Novel therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 170–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kowaltowski, A.J.; de Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Castilho, R.F.; Vercesi, A.E. Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 47, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suski, J.M.; Lebiedzinska, M.; Bonora, M.; Pinton, P.; Duszynski, J.; Wieckowski, M.R. Relation between mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS formation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 810, 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Cadenas, S. Mitochondrial uncoupling, ROS generation and cardioprotection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 2018, 1859, 940–950. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Chattopadhyay, R.; Mitra, S.; Crowe, S.E. Oxidative Stress: An Essential Factor in the Pathogenesis of Gastrointestinal Mucosal Diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Snezhkina, A.V.; Kudryavtseva, A.V.; Kardymon, O.L.; Savvateeva, M.V.; Melnikova, N.V.; Krasnov, G.S.; Dmitriev, A.A. ROS Generation and Antioxidant Defense Systems in Normal and Malignant Cells. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 6175804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Understanding mechanisms of antioxidant action in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sincák, M.; Sedlakova-Kadukova, J. Hypomagnetic Fields and Their Multilevel Effects on Living Organisms. Processes 2023, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, C.F.; Perea, H.; Hopfner, U.; Ferguson, V.L.; Wintermantel, E. Effects of Weak Static Magnetic Fields on Endothelial Cells. Bioelectromagnetics 2010, 31, 296–301. [Google Scholar]

- Martino, C.F.; Castello, P.R. Modulation of Hydrogen Peroxide Production in Cellular Systems by Low Level Magnetic Fields. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.T.; Zhang, Z.J.; Mo, W.C.; Hu, P.D.; Ding, H.M.; Liu, Y.; Hua, Q.; He, R.Q. Shielding of the geomagnetic field reduces hydrogen peroxide production in human neuroblastoma cell and inhibits the activity of CuZn superoxide dismutase. Protein Cell 2017, 8, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Novikov, V.V.; Yablokova, E.V.; Fesenko, E.E. The Effect of a Zero Magnetic Field on the Production of Reactive Oxygen Species in Neutrophils. Biophysics 2018, 63, 365–368. [Google Scholar]

- Novikov, V.V.; Yablokova, E.V.; Valeeva, E.R.; Fesenko, E.E. On the Molecular Mechanisms of the Effect of a Zero Magnetic Field on the Production of Reactive Oxygen Species in Inactivated Neutrophils. Biophysics 2019, 64, 571–575. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.P.; Mo, W.C.; Liu, Y.; He, R.Q. Decline of cell viability and mitochondrial activity in mouse skeletal muscle cell in a hypomagnetic field. Bioelectromagnetics 2016, 37, 212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Luo, Y.; Zhan, A.; Ren, J.; Qin, H.; Pan, Y. Hypomagnetic Field Induces the Production of Reactive Oxygen Species and Cognitive Deficits in Mice Hippocampus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Ren, J.; Luo, Y. The effects of different durations of exposure to hypomagnetic field on the number of active mitochondria and ROS levels in the mouse hippocampus. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 38, 101696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Xie, L.; Zheng, Q.; Yang, P.F.; Zhang, W.J.; Ding, C.; Qian, A.R.; Shang, P. A hypomagnetic field aggravates bone loss induced by hindlimb unloading in rat femurs. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Meng, X.F.; Dong, D.D.; Xue, Y.R.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.H.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, G.J.; Shang, P. Iron overload involved in the enhancement of unloading-induced bone loss by hypomagnetic field. Bone 2018, 114, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nadeev, A.D.; Terpilowski, M.A.; Bogdanov, V.A.; Khmelevskoy, D.A.; Shchegolev, B.F.; Surma, S.V.; Stefanov, V.E.; Jenkins, R.O.; Goncharov, N.V. Effects of exposure of rat erythrocytes to a hypogeomagnetic field. Biomed. Spectrosc. Imaging 2018, 7, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.K.; Zhan, A.S.; Fan, Y.C.; Tian, L.X. Effects of hypomagnetic field on adult hippocampal neurogenic niche and neurogenesis in mice. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 1075198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannino, G.; Casacci, L.P.; Dolino, G.B.; Badolato, G.; Maffei, M.E.; Barbero, F. The Geomagnetic Field (GMF) Is Necessary for Black Garden Ant (Lasius niger L.) Foraging and Modulates Orientation Potentially through Aminergic Regulation and MagR Expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, A.; Luo, Y.; Qin, H.; Lin, W.; Tian, L. Hypomagnetic Field Exposure Affecting Gut Microbiota, Reactive Oxygen Species Levels, and Colonic Cell Proliferation in Mice. Bioelectromagnetics 2022, 43, 462–475. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P.D.; Mo, W.C.; Fu, J.P.; Liu, Y.; He, R.Q. Long-term Hypogeomagnetic Field Exposure Reduces Muscular Mitochondrial Function and Exercise Capacity in Adult Male Mice. Prog. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 47, 426–438. [Google Scholar]

- Beręsewicz, A. NADPH oxidases, nuclear factor kappa B, NF-E2-related factor2, and oxidative stress in diabetes. In Diabetes; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Marchi, S.; Guilbaud, E.; Tait, S.W.G.; Yamazaki, T.; Galluzzi, L. Mitochondrial control of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sies, H.; Mailloux, R.J.; Jakob, U. Fundamentals of redox regulation in biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Khalil, A.A.; Awadallah, S.; Khan, S.A.; Abu-Izneid, T.; Kamran, M.; Hemeg, H.A.; Mubarak, M.S.; Khalid, A.; Wilairatana, P. Reactive oxygen species in biological systems: Pathways, associated diseases, and potential inhibitors—A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lennicke, C.; Cochemé, H.M. Redox metabolism: ROS as specific molecular regulators of cell signaling and function. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 3691–3707. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, e17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.J.; Liu, Z. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB signaling. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, S.; Kitamura, M. Bidirectional regulation of NF-κB by reactive oxygen species: A role of unfolded protein response. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 162–174. [Google Scholar]

- Toledano, M.B.; Leonard, W.J. Modulation of Transcription Factor Nf-Kappa-B Binding-Activity by Oxidation Reduction Invitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 4328–4332. [Google Scholar]

- Korn, S.H.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Vos, N.; Janssen-Heininger, Y.M.W. Cytokine-induced activation of nuclear factor-κB is inhibited by hydrogen peroxide through oxidative inactivation of IκB kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 35693–35700. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; Bian, Q.; Liu, Y.; Fernandes, A.F.; Taylor, A.; Pereira, P.; Shang, F. Sustained oxidative stress inhibits NF-kappaB activation partially via inactivating the proteasome. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 46, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Herb, M.; Gluschko, A.; Wiegmann, K.; Farid, A.; Wolf, A.; Utermohlen, O.; Krut, O.; Kronke, M.; Schramm, M. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species enable proinflammatory signaling through disulfide linkage of NEMO. Sci. Signal. 2019, 12, eaar5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.E.; Tian, B.; Jamaluddin, M.; Boldogh, I.; Vergara, L.A.; Choudhary, S.; Brasier, A.R. RelA Ser phosphorylation is required for activation of a subset of NF-κB-dependent genes by recruiting cyclin-dependent kinase 9/cyclin T1 complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 3623–3638. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gloire, G.; Piette, J. Redox Regulation of Nuclear Post-Translational Modifications During NF-κB Activation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 2209–2222. [Google Scholar]

- Anrather, J.; Racchumi, G.; Iadecola, C. NF-kappaB regulates phagocytic NADPH oxidase by inducing the expression of gp91phox. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 5657–5667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakata, S.; Tsutsui, M.; Shimokawa, H.; Yamashita, T.; Tanimoto, A.; Tasaki, H.; Ozumi, K.; Sabanai, K.; Morishita, T.; Suda, O.; et al. Statin treatment upregulates vascular neuronal nitric oxide synthase through Akt/NF-κB pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.H.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Li, G.Y.; Wang, J.; Li, T.T.; Li, W.; Lu, J.Y. Regulation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase exon 1f gene expression by nuclear factor-κB acetylation in human neuroblastoma cells. J. Neurochem. 2007, 101, 1194–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Das, K.C.; Lewismolock, Y.; White, C.W. Activation of Nf-Kappa-B and Elevation of Mnsod Gene-Expression by Thiol Reducing Agents in Lung Adenocarcinoma (A549) Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 1995, 269, L588–L602. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.L.; Ping, D.S.; Boss, J.M. Tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1 beta regulate the murine manganese superoxide dismutase gene through a complex intronic enhancer involving C/EBP-beta and NF-kappa B. Mol. Cell Biol. 1997, 17, 6970–6981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, K.; Karin, M. NF-κB, inflammation, immunity and cancer: Coming of age. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 309–324. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Na, H.J.; Kim, C.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Ha, K.S.; Lee, H.; Chung, H.T.; Kwon, H.J.; Kwon, Y.G.; Kim, Y.M. The non-provitamin A carotenoid, lutein, inhibits NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression through redox-based regulation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/Akt and NF-kappaB-inducing kinase pathways: Role of H2O2 in NF-kappaB activation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sethi, G.; Sung, B.; Aggarwal, B.B. Aggarwal, Nuclear factor-κB activation: From bench to bedside. Exp. Biol. Med. 2008, 233, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Min, K.J.; Pyo, H.K.; Yang, M.S.; Ji, K.A.; Jou, I.; Joe, E.H. Gangliosides activate microglia via protein kinase C and NADPH oxidase. Glia 2004, 48, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.H.; Park, E.J.; Jou, I.; Kim, J.H.; Joe, E.H. Reactive oxygen species mediate Aβ(25-35)-induced activation of BV-2 microglia. Neuroreport 2001, 12, 1449–1452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.Y.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, H.; Yoo, H.S.; Yun, Y.P.; Oh, K.W.; Ha, T.Y.; Hong, J.T. Inhibitory effect of green tea extract on β-amyloid-induced PC12 cell death by inhibition of the activation of NF-κB and ERK/p38 MAP kinase pathway through antioxidant mechanisms. Mol. Brain Res. 2005, 140, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhen, Y.F.; Pu-Bu-Ci-Ren; Song, L.G.; Kong, W.N.; Shao, T.M.; Li, X.; Chai, X.Q. Salidroside attenuates beta amyloid-induced cognitive deficits via modulating oxidative stress and inflammatory mediators in rat hippocampus. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 244, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C.R.; Wang, S.N.; Zhu, S.Y.; Wang, Y.Q.; Li, Z.Z.; Liu, Z.Y.; Jiang, W.S.; Chen, J.T.; Wu, Q. Advanced oxidation protein products increase TNF-α and IL-1β expression in chondrocytes via NADPH oxidase 4 and accelerate cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritis progression. Redox Biol. 2020, 28, 101306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.S.; Zou, Y.; Peng, J. Oregano Essential Oil Attenuates RAW264.7 Cells from Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Response through Regulating NADPH Oxidase Activation-Driven Oxidative Stress. Molecules 2018, 23, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ullah, R.; Tong, J.; Shen, Y. The role of the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway in the corneal epithelium: Recent updates. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, N.; Batty, I.; Maccario, H.; Davidson, L.; Downes, C.P. Understanding PTEN regulation: PIP2, polarity and protein stability. Oncogene 2008, 27, 5464–5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, M.; Frittoli, E.; Ponzanelli, I.; Falck, J.R.; Brachmann, S.M.; Di Fiore, P.P.; Scita, G. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase activates Rac by entering in a complex with Eps8, Abi1, and Sos-1. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 160, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leslie, N.R.; Downes, C.P. PTEN: The down side of PI 3-kinase signalling. Cell. Signal. 2002, 14, 285–295. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Zhao, L.; Gui, Z.W.; Liu, S.Y.; Liu, C.G.; Yu, T.Y.; Zhang, L. PI3K/AKT signaling activates HIF1α to modulate the biological effects of invasive breast cancer with microcalcification. NPJ Breast Cancer 2023, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, L.O.; Sánchez-Ramos, C.; Prieto-Arroyo, I.; Urbánek, P.; Steinbrenner, H.; Monsalve, M. Redox regulation of FoxO transcription factors. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, A.R.; Ali, F.E.M.; Abd-Elhamid, T.H.; Hassanein, E.H.M. Coenzyme Q10 protects hepatocytes from ischemia reperfusion-induced apoptosis and oxidative stress via regulation of Bax/Bcl-2/PUMA and Nrf-2/FOXO-3/Sirt-1 signaling pathways. Tissue Cell 2019, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Keshet, Y.; Seger, R. The MAP kinase signaling cascades: A system of hundreds of components regulates a diverse array of physiological functions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010, 661, 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kirtonia, A.; Sethi, G.; Garg, M. The multifaceted role of reactive oxygen species in tumorigenesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 4459–4483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Averill-Bates, D. Reactive oxygen species and cell signaling. Review. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Cell Res. 2024, 1871, 119573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNicola, G.M.; Karreth, F.A.; Humpton, T.J.; Gopinathan, A.; Wei, C.; Frese, K.; Mangal, D.; Yu, K.H.; Yeo, C.J.; Calhoun, E.S.; et al. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature 2011, 475, 106–109. [Google Scholar]

- Belyavskaya, N.A. Biological effects due to weak magnetic field on plants. Adv. Space Res. 2004, 34, 1566–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belyavskaya, N.A. Ultrastructure and calcium balance in meristem cells of pea roots exposed to extremely low magnetic fields. Adv. Space Res. 2001, 28, 645–650. [Google Scholar]

- St-Pierre, J.; Drori, S.; Uldry, M.; Silvaggi, J.M.; Rhee, J.; Jager, S.; Handschin, C.; Zheng, K.; Lin, J.; Yang, W.; et al. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell 2006, 127, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lingappan, K. NF-kappaB in Oxidative Stress. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 7, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Berk, M.; Campochiaro, P.A.; Jaeschke, H.; Marenzi, G.; Richeldi, L.; Wen, F.Q.; Nicoletti, F.; Calverley, P.M.A. The Multifaceted Therapeutic Role of N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) in Disorders Characterized by Oxidative Stress. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2021, 19, 1202–1224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zarka, M.H.; Bridge, W.J. Oral administration of gamma-glutamylcysteine increases intracellular glutathione levels above homeostasis in a randomised human trial pilot study. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quintana-Cabrera, R.; Bolanos, J.P. Glutathione and gamma-glutamylcysteine in hydrogen peroxide detoxification. Methods Enzymol. 2013, 527, 129–144. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).