Abstract

Background/Objectives: Combined chromosome 7 gain and chromosome 10 loss (+7/−10) is the most frequent cytogenetic alteration and a defining diagnostic criterion for isocitrate dehydrogenase wild-type (IDHwt) glioblastoma. Despite the association with poor prognosis, its clinical and therapeutic significance remains unclear. We aim to systematically review its clinical significance, focusing on prevalence, prognostic value, and potential association with therapeutic resistance in adult patients. Methods: PubMed, Embase, CENTRAL, Scopus, EBSCOhost, and Web of Science were searched from inception to April 2025, using controlled vocabulary and free-text terms. Eligible studies included adult glioblastoma with molecular confirmation of combined chromosome 7 gain and chromosome 10 loss and reported survival or treatment response. Quality was assessed qualitatively, and findings were synthesized descriptively. Results: Of 3249 records, 5 observational studies (523 patients) were included. The signature was present in 60% to 70% of glioblastoma cases and frequently co-occurred with epidermal growth factor receptor amplification and telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter mutations. This alteration was consistently associated with shorter survival (mean, 8–70 weeks) compared with tumors lacking the alteration (19–170 weeks). In one study, the signature was more common in radioresistant tumors (9/20 vs. 1/10). Molecular evidence suggests that this alteration arises early in tumorigenesis. Conclusions: The +7/−10 cytogenetic alteration, common in glioblastoma, is frequently associated with aggressive clinical behavior. While exploratory data suggest a possible association with radiotherapy response, current evidence is insufficient to establish a predictive or therapeutic role. Its principal clinical value lies in diagnosis, molecular classification, and risk stratification. Incorporating cytogenetic testing for this alteration into routine glioblastoma workup may improve risk stratification and guide individualized management.

1. Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is a highly aggressive brain tumor characterized by a genetic and molecular component that determines its classification and disease progression [1]. A common genomic alteration is the co-occurrence of chromosome 7 gain and chromosome 10 loss (+7/−10) [2], incorporated into the 5th version of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) to define isocitrate dehydrogenase wildtype (IDHwt) GBM [2,3,4]. These variations reflect high genomic instability [1]. Its presence leads tumors previously classified as high-grade glioma (astrocytomas IDHwt, grades 2 and 3) to acquire a GBM status [3].

Although this genetic signature confers a diagnosis of GBM to astrocytomas IDHwt grades 2 and 3 and is associated with an aggressive clinical course, its clinical implications remain unclear among GBM patients [5]. The heterogeneity of therapeutic response, tumor aggressiveness, and overall survival (OS) has not yet been studied. Despite the well-established association of +7/−10 with GBM, no prior study has systematically compared GBM patients exhibiting this cytogenetic profile and those without it in terms of clinically relevant outcomes. This scoping review aims to address this gap by focusing exclusively on GBM, thereby providing a more nuanced understanding of the prognostic relevance of these chromosomal alterations within this distinct tumor entity.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted following the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews) Checklist (Supplemental Material). The protocol for this scoping review was registered in the Open Science Framework database (DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/ZBUAY).

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Studies involving adults with GBM with molecular and genetic analysis to identify the +7/−10, reporting at least one clinical outcome, such as OS and/or therapeutic response. The types of studies sought were clinical trials, cohort studies, descriptive studies, case series, and/or case reports. No restrictions were applied for publication date or language if translation was available.

Exclusion criteria were pediatric patients; midline GBM, brainstem GBM, GBM with oligodendroglial component, or other variants; studies involving separate chromosome 7 gain or chromosome 10 loss (+7/−10), or only one chromosome arm abnormality. Non-peer-reviewed publications, journal supplements, editorials, letters, technical notes, conference abstracts, or non-human participant studies were not considered.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted across databases and search engines (PubMed, Embase, CENTRAL, Scopus, EBSCOhost, and Web of Science) up to 20 April 2025. Keywords using MeSH and DeCS descriptors, as well as free terms, were applied to search for “whole chromosome 7 gain”, “whole chromosome 10 loss”, “chromosome 7 gain/10 loss”, and “glioblastoma”.

2.3. Selection of Sources of Evidence

Zotero and Rayyan (https://www.rayyan.ai/, accessed from 1 January 2023 to 31 October 2025) were used to manage references and remove duplicates, and Rayyan for article selection. Four authors in two pairs screened titles and abstracts, each pair reviewing half of the references. Full-text reviews were then conducted independently by all four authors. Discrepancies were resolved between pairs. Reference lists of included studies were also reviewed to identify additional eligible studies.

2.4. Data Charting Process and Data Items

Four authors, working in pairs, independently extracted data from the included studies, dividing the references equally. Extracted information was compiled in a spreadsheet. It included: study details (first author, title, year, journal, country, and funding), population characteristics (sample size, mean age, and sex) tumor characteristics (diagnosis, location, imaging findings, molecular and genetics features, EGFR amplification status, details about the chromosome 7/chromosome 10 abnormalities, and the molecular method for analysis), management (surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy), and outcomes. Discrepancies were resolved collaboratively through discussion among the authors.

2.5. Synthesis of Results

The data extracted from the included studies was synthesized through a qualitative analysis, focusing on key themes across the literature. The results are presented descriptively, utilizing tables to systematically organize and summarize the main findings.

3. Results

3.1. Selected Studies

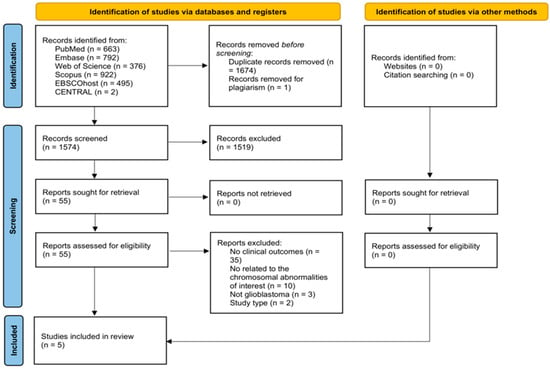

A total of 3249 articles were identified through the systematic search. After removing duplicates, 1574 studies were screened by title and abstract. 54 articles were sought for retrieval and were included for full-text review. Five studies were included in this review [6,7,8,9,10] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews flow diagram of study selection.

3.2. Study Characteristics

All five included observational studies [6,7,8,9,10] were from the United States [6,10], Turkey [7], Germany [8], and Spain [9]. Four studied the correlation of the +7/−10 alteration among GBM patients and its impact on OS [6,7,8,9], and the other one on differential response to radiotherapy according to the presence of the co-occurrence [10]. A summary of the included studies is presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Overview of included studies.

Table 2.

Summary of clinical outcomes of the included studies.

3.3. Study Outcomes and Synthesis of Results

3.3.1. Chromosome 7 Gain and Chromosome 10 Loss, and OS

López-Ginés et al. [9] studied 25 newly diagnosed GBM cases using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to assess chromosomal status and EGFR amplification. 58% of patients (14/25) had trisomy or polysomy of chromosome 7 and monosomy of chromosome 10. Of these, 28% (7/25) exhibited this chromosomal alteration alongside EGFR amplification. Overall, 52% of patients had EGFR gene amplification alone, and the +7/−10 was the most frequent alteration. Survival analysis showed that patients with +7/−10, regardless of EGFR status, had shorter survival times than those without these alterations (mean survival: 36 ± 3.7 weeks vs. 48 ± 4.7 weeks). These findings suggest a possible association between the +7/−10 alteration and poorer prognosis; however, the limited sample size and lack of statistical significance preclude definitive conclusions. It may represent an early event in tumorigenesis, occurring before EGFR gene amplification, which might be a later and independent event.

Arslantas et al. [7] conducted genomic profiling of primary GBMs and chromosomal abnormalities with potential prognostic significance. The most common alteration in patients with shorter OS was the complete loss of chromosome 10, however tumors showing both +7/−10 alteration, particularly in the 7p11–p13 region, were consistently associated with poor outcomes, hence limiting the specificity of this signature as an independent prognostic marker Five cases exhibited the +7/−10 alteration, with a mean survival of just 5.0 ± 3.1 months, compared to the overall average survival of 10.0 ± 5.6 months across all patients. This suggests that the +7/−10 alteration profile may serve as a marker of poor prognosis among GBM patients

Stichel et al. [8] evaluated the prognostic impact of the +7/−10 alteration across glioma subtypes. Survival analysis on 939 IDHwt gliomas showed that patients with the +7/−10, +7/−10q, or +7q/−10 alterations had significantly worse OS. Although the study did not directly compare GBM patients with and without the +7/−10 signature, a subset analysis of 167 patients, classified as GBM based on methylation profiling, revealed that 52 patients did not carry the +7/−10 alteration, but showed survival curves nearly identical to those of the 115 GBM patients who did. This finding emphasizes that while the +7/−10 signature may be associated with poor prognosis, it is not strictly necessary for observing poor survival rates in GBM.

Finally, Nair et al. [6] in their survival analysis of GBM patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort, stratified by chromosome 7 and 10 copy number status, revealed a marked difference in overall prognosis depending on the presence of aneuploidy. Patients with +7/−10 tumors exhibited the poorest OS, with most dying within 70 weeks. In contrast, patients without either alteration demonstrated relatively prolonged survival, in some cases exceeding 170 weeks. Intermediate outcomes were observed in patients with isolated alterations. However, only four patients lacked chromosomal alterations, substantially limiting the robustness of comparisons and precluding definitive conclusions.

3.3.2. Chromosome 7 Gain and Chromosome 10 Loss, and Radiotherapy Response

The study by Huhn et al. [10] explored the relationship between chromosomal abnormalities and radiotherapy response in GBM using comparative genomic hybridization. A total of 30 frozen tumor samples were analyzed and categorized into radiation-resistant (n = 20) and radiation-sensitive (n = 10) groups based on contrast enhancement changes following treatment. The +7/−10 signature was identified in 9 out of 20 resistant tumors, compared to only 1 out of 10 in the radiosensitive group. Although the +7/−10 alteration was more frequently observed in radiation-resistant tumors, no statistically significant association was demonstrated. These findings should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating only; worth mentioning that this specific chromosomal alteration and resistance to radiotherapy warrant further investigation in larger, controlled cohorts. The authors proposed that a higher frequency of copy number alterations (CNAs), including +7/−10, in the radioresistant group may indicate increased genomic instability, potentially contributing to a phenotype more resilient to radiation.

4. Discussion

4.1. 7/10 Signature Prevalence and Its Relationship with GBM

This review assessed the clinical significance of the +7/−10 signature in GBM. Across the five included studies, prevalence estimates of the +7/−10 signature ranged from approximately 60% to 70% of GBM cases, although direct comparisons are limited by differences in cohort composition and detection methodology [6,7,8,9,10]. Gains of chromosome 7 alone were highly frequent, but losses of chromosome 10 were almost always found in conjunction with chromosome 7 gains. Other chromosomal alterations included amplification of 12q regions, isolated loss of 1p, 9p, 17p, and 19q, and gains involving chromosomes 19 and 20. However, these were less frequent than the hallmark +7/−10 [7,10]. These findings emphasize the predominance of +7/−10 as a defining feature of GBM genomic architecture, underscoring their central role in tumor initiation and progression.

Genomic instability drives cancer initiation and progression, ranging from small DNA sequence mutations to large-scale chromosomal abnormalities [11,12]. +7/−10 alteration in GBM represents a recurrent form of numerical chromosomal instability, which is a well-established consequence of centrosome amplification and mitotic checkpoint failure [13,14]. Centrosomes organize microtubules for bipolar spindle formation in mitosis [12], but amplification in tumors leads to multipolar spindles, causing chromosome missegregation and aneuploidy [12,13,14]. Cancer cells cluster extra centrosomes into pseudo-bipolar spindles, preserving viability while keeping chromosomal instability [12,15].

In parallel, defects in the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), mediated by kinases such as Aurora A and B, allow mitotic errors and promote the evolution of tetraploid intermediates [16,17]. These intermediates, particularly in TP53-deficient contexts, bypass checkpoints and proliferate with increased centrosome and genomic content, propagating karyotypic chaos [12]. This interplay between centrosome amplification and SAC dysfunction drives the selection of specific, clonally advantageous aneuploidies such as the +7/−10, which confer both survival benefits and proliferative potential.

Other mechanisms contribute to the development of aneuploidy in cancer. Mitotic spindle assembly defects, particularly errors in microtubule–kinetochore attachments, can lead to lagging chromosomes and subsequent missegregation during cell division [18,19]. Likewise, kinetochore malfunctions, arising from structural abnormalities or disrupted protein complexes, impair the proper attachment and alignment of chromosomes on the spindle apparatus, further increasing the risk of aneuploid progeny [19,20]. Dysfunction of the cohesin complex, essential for maintaining sister chromatid cohesion until anaphase, can result in premature chromatid separation and chromosomal instability [21,22]. These mechanisms often act in concert with the centrosome and checkpoint abnormalities, collectively driving the chromosomal imbalances characteristic of tumors with high chromosomal instability, such as GBM.

There are a few studies investigating the intricate mechanisms underlying the occurrence of this chromosomal phenomenon. Körber et al. [23] studied the mechanism of driving GBM evolution by reconstructing the phylogenetic trajectories of primary and recurrent tumors. Their study demonstrated that chromosome 7 gain and chromosome 10 loss are among the earliest clonal events, often occurring together at tumor initiation, even years before clinical diagnosis. These large-scale chromosomal alterations establish a common evolutionary path across IDHwt GBM, preceding other driver mutations such as telomerase transcriptase reverse promoter (TERTp) mutations. This suggests that the +7/−10 reflects essential early steps in tumorigenesis rather than consequences of later selective pressures, highlighting their relevance as stable biomarkers and potential early therapeutic targets.

Building on these findings, Nair et al. [6] provided important insights into the early genomic events by exploring the functional relationship between chromosome 10 loss and 7 gain, proposing that their frequent co-occurrence is driven by a synthetic rescue mechanism. Loss of chromosome 10 removes key tumor suppressor genes such as PTEN, ANXA7, and KLF6 [24,25,26,27], which, while favoring tumor progression, also disrupt essential cellular processes and impose a significant fitness cost. To survive this, tumor cells upregulate compensatory genes, often oncogenes, on chromosome 7. These include EGFR [28], which can functionally rescue PTEN loss; and MET [29], which compensates for ANXA7 loss. This phenomenon reflects an adaptive, not random, evolutionary response, whereby chromosome 7 gain mitigates the detrimental effects of chromosome 10 loss through a distributed compensatory network.

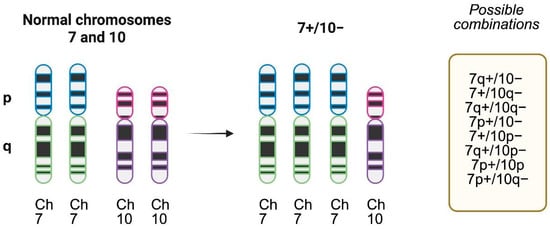

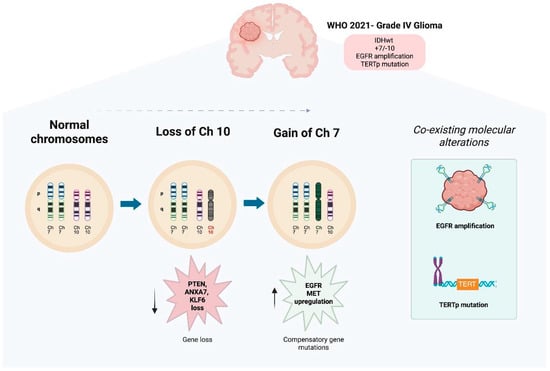

Such interplay illustrates how chromosomal aneuploidy in GBM is not merely a byproduct of genomic instability but a dynamic and selective mechanism enhancing tumor fitness. Together, these studies emphasize that chromosome 7 gain and 10 loss are both foundational events and functional adaptations in GBM pathogenesis, with important implications for understanding tumor evolution and guiding therapeutic development. Several possible chromosomal alterations for chromosomes 7 and 10 exist, as seen in Figure 2. This interplay between the +7/−10 along with co-occurring EGFR amplification and TERTp mutations is illustrated in Figure 3, highlighting their role as early and functionally compensatory events in GBM pathogenesis.

Figure 2.

Chromosome 7 gain and chromosome 10 loss patterns of alterations. Complete chromosome 7 gain (trisomy) and 10 loss (monosomy) is the most frequent pattern, but several possible combinations in the short (p) or long arm (q) exist and have been described in molecular studies. Created with www.biorender.com.

Figure 3.

Key Mechanisms in GBM Evolution: +7/−10 Signature, EGFR Amplification, and TERTp Mutation. Created with www.biorender.com.

Progression from normal chromosomal configuration to the characteristic gain of chromosome 7 and loss of chromosome 10 (+7/−10) is observed in GBM. The loss of chromosome 10 leads to the deletion of key tumor suppressor genes, including PTEN, ANXA7, and KLF6. There is impaired tumor suppressive functions, and as a compensatory response, there is a gain of chromosome 7, which results in overexpression of oncogenes like EGFR and MET, which promote cell proliferation and survival. These early and co-occurring chromosomal events contribute to genomic instability and establish a clonally advantageous profile that underlies GBM initiation and progression. EGFR amplification and TERT promoter (TERTp) mutations frequently co-occur with the +7/−10 signature, defining a distinct subgroup of high-risk gliomas. This cytogenetic pattern is integrated into the 2021 WHO classification of CNS tumors [30] for the diagnosis of grade IV IDH-wildtype glioblastoma, even in tumors lacking overt high-grade histological features.

Amalfitano et al. [31] analyzed chromosomes 7 and 10 via FISH in 64 GBM (44 primary, 20 secondary), finding similar rates of chromosome 7 gain and 10 loss across both subtypes. Combined +7/−10 alterations appeared in 68% of primary and 70% of secondary tumors. Notably, 14.3% of primary GBM with chromosome 10 loss retained chromosome 7 disomy, unlike secondary cases. This led the authors to suggest that chromosome 10 loss may precede chromosome 7 gain, especially in secondary GBM.

4.2. Clinical Implications of the +7/−10 Signature

The +7/−10 alteration is one of the most frequent and significant alterations in GBM, especially among IDHwt tumors [6,32]. Its presence is associated with poor OS [32]. Currently, it is part of the defining molecular features of GBM, even in tumors with lower-grade histology [32]. Multiple studies have shown [33,34,35] that patients with IDHwt astrocytomas who have this cytogenetic pattern experience clinical outcomes indistinguishable from those of conventional GBM, supporting their reclassification as GBM based on molecular findings, even if they were classified as low-grade histologically [32]. Partial chromosomal alterations, such as 7q gain combined with 10q loss, appear to reflect the clinical relevance of changes in the entire arm [32]. Additionally, it has also been detected in radiation-resistant tumors, suggesting a possible association with treatment failure, primarily in response to radiotherapy [10]. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to incorporate cytogenetic testing into standard diagnostic testing, as early identification of this pattern has direct implications for both prognosis and treatment planning.

On the other hand, other key molecular alterations that coexist with chromosome 7 gain and chromosome 10 loss are EGFR amplification and TERTp mutation. These two co-occurrences have shown specificity of up to 99.4% for IDHwt GBM and are absent in non-GBM entities [3,6]. EGFR amplification, typically mapped to 7p11.2, tends to appear after complete chromosome 7 gain and is associated with increased pathway activation and tumor proliferation [6,8]. Although EGFR amplification is the most specific of these markers, its sensitivity is limited, so it should be interpreted in conjunction with the +7/−10 and TERTp mutation status [3]. TERTp mutations, on the other hand, are more prevalent but less specific [8]. Taken together, the +7/−10, EGFR amplification, and TERTp mutation define a subgroup of high-risk gliomas that warrants precise classification and could benefit from individualized therapeutic strategies [6,8].

Furthermore, other alterations, along with the +7/−10, can shape clinical behavior and treatment response, such as codeletions involving 9p23–24 and 13q14 (regions that include CDKN2A/B and RB1), that are frequently found in older patients and have been linked to radioresistance [10]. These deletions possibly contribute to impaired cell cycle control and reduced apoptotic potential. Other recurrent alterations include gains in chromosomal regions such as 7q, 19p, 1p, 4q, and 12q, which are thought to promote genomic instability and more aggressive phenotypes [6]. Some of these combinations may reflect rescue interactions, where gains of oncogenes on chromosome 7 (e.g., EGFR, MET, BRAF) can compensate for losses on chromosome 10 (e.g., PTEN, ADARB2), collectively improving tumor survival [6].

4.3. Future Perspectives

The +7/−10 signature has shown utility as a molecular hallmark for the diagnosis of IDHwt GBM, and upgrading the diagnosis of IDHwt astrocytomas (grades 2 and 3) to GBM, as seen in the 2021 WHO CNS tumor classification [30], in spite of nuclear or ambiguous histopathological features [3,8,36]. Looking toward the future, probable implications regarding treatment outcomes and patient stratification can be expected, along with a more prominent role of molecular studies for earlier aggressive tumor recognition. Current studies are being carried out to differentiate between the partial or whole chromosome alterations in diagnosis and prognosis [7,28], as well as to elucidate the interaction between these molecular changes with other genetic alterations or biomarkers, to generate improved grading and risk groups [7,37]. Furthermore, targeted therapy and non-invasive monitoring of these genetic alterations could also be implemented in the future [3].

4.4. Limitations

Despite the limitations of this scoping review, it provides meaningful insights into the prognostic significance of the +7/−10 in GBM. The small number of studies included, reduced study samples, and the variability in study designs warrant careful interpretation of the findings. Evidence suggests the co-occurrence is associated with poorer survival and may be a biomarker for aggressive GBM.

Future research should aim to address these limitations by expanding the sample size to enhance the statistical power for the generalizability of the results. Additionally, standardization of methodologies, particularly in chromosomal analysis, is essential for consistency across studies. Longitudinal, prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials are needed to further explore the prognostic implications of the +7/−10, as well as its potential role in resistance to therapies such as radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. Ultimately, these efforts will help refine our understanding of GBM progression and improve patient outcomes through more personalized treatment approaches.

5. Conclusions

The +7/−10 signature is a frequent cytogenetic alteration in GBM and is consistently associated with poor survival across multiple cohorts. While biological and exploratory clinical data suggest a possible link with treatment resistance, current evidence remains insufficient to establish a predictive role. Its principal clinical value at present lies in diagnosis, molecular classification, and risk stratification. While not exclusive to GBM, the +7/−10 signature remains a valuable prognostic marker for high-grade glioma. Future research should explore its role in therapeutic resistance and its potential as a target for personalized treatment strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/brainsci16010060/s1, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist. Reference [38] is cited in the supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

A.R.-M., R.F.V.-A., C.R.-F. and A.L.C. were responsible for the data collation and primary manuscript generation. A.R.-M., R.F.V.-A., C.R.-F., S.F.-T., P.A.-A., D.F.G., F.H., J.F.R., E.G.O.-R., A.C.-C., C.P.-G. and R.P.-M. were responsible for manuscript editing. A.R.-M. performed the editing of the clinical figures. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or the use of identifiable private data, and therefore did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or the use of identifiable human data.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GBM | Glioblastoma |

| Ch+7/−10 | Co-occurrence of chromosome 7 gain and chromosome 10 loss |

| FISH | Fluorescence in situ hybridization |

| OS | Overall survival |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| IDHwt | Isocitrate dehydrogenase wildtype |

| TCGA | The cancer genome atlas |

| CNAs | Copy number alterations |

| SAC | Spindle assembly checkpoint |

| TERTp | Telomerase transcriptase reverse promoter |

References

- Delgado-Martín, B.; Medina, M.Á. Advances in the Knowledge of the Molecular Biology of Glioblastoma and Its Impact in Patient Diagnosis, Stratification, and Treatment. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1902971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandner, S. Molecular Diagnostics of Adult Gliomas in Neuropathological Practice. Acta Med. Acad. 2021, 50, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śledzińska, P.; Bebyn, M.G.; Furtak, J.; Kowalewski, J.; Lewandowska, M.A. Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in Gliomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sourty, B.; Dardaud, L.-M.; Bris, C.; Loussouarn, D.; Campion, L.; Mosser, J.; Vallette, F.M.; Cartron, P.-F. Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number as a Prognostic Marker Is Age-Dependent in Adult Glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2022, 4, vdab191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreyra Vega, S.; Wenger, A.; Kling, T.; Olsson Bontell, T.; Jakola, A.S.; Carén, H. Spatial Heterogeneity in DNA Methylation and Chromosomal Alterations in Diffuse Gliomas and Meningiomas. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 1551–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, N.U.; Schäffer, A.A.; Gertz, E.M.; Sharma, S.; Raghunathan, A.; Tembe, W.D.; Pochampally, R.; Smith, C.; Tuttle, R.; Brown, A.; et al. Chromosome 7 Gain Compensates for Chromosome 10 Loss in Glioma. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 3464–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslantas, A.; Artan, S.; Oner, U.; Müslümanoglu, M.; Ozdemir, M.; Durmaz, R. The Importance of Genomic Copy Number Changes in the Prognosis of Glioblastoma Multiforme. Neurosurg. Rev. 2004, 27, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stichel, D.; Ebrahimi, A.; Reuss, D.E.; Schrimpf, D.; Ono, T.; Shirahata, M.; Sahm, F.; Korshunov, A.; Wefers, A.K.; Reinhardt, A.; et al. Distribution of EGFR Amplification, Combined Chromosome 7 Gain and Chromosome 10 Loss, and TERT Promoter Mutation in Brain Tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Gines, C.; Cerda-Nicolas, M.; Gil-Benso, R.; Pellín, A.; López-Guerrero, J.A.; Callaghan, R.; Benito, R.; Roldán, P.; Piquer, J.; Llombart-Bosch, A. Association of Chromosome 7, Chromosome 10 and EGFR Gene Amplification in Glioblastoma Multiforme. Clin. Neuropathol. 2005, 24, 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Huhn, S.L.; Mohapatra, G.; Bollen, A.; Lamborn, K.R.; Prados, M.D.; Feuerstein, B.G. Chromosomal Abnormalities in Glioblastoma Multiforme by Comparative Genomic Hybridization. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoleni, A.; Awuah, W.A.; Sanker, V.; Kearns, P.; McDonald, D.; Jones, C.; Pfister, S.M.; Kool, M.; Sturm, D.; Jones, D.T.W. Chromosomal Instability: A Key Driver in Glioma Pathogenesis and Progression. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L.R.; Chen, H.; Collins, A.R.; Connell, M.; Damia, G.; Dasgupta, S.; Malhotra, M.; Meeker, A.K.; Amedei, A.; Amin, A.; et al. Genomic Instability in Human Cancer: Molecular Insights and Opportunities for Therapeutic Attack and Prevention through Diet and Nutrition. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2015, 35, S5–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barra, V.; Fachinetti, D. The Dark Side of Centromeres: Types, Causes and Consequences of Structural Abnormalities Implicating Centromeric DNA. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karami Fath, M.; Nazari, A.; Parsania, N.; Rahmati, M.; Karimi Dermani, F.; Alidadi, S.; Amini, M.; Mirzaei, H. Centromeres in Cancer: Unraveling the Link between Chromosomal Instability and Tumorigenesis. Med. Oncol. 2024, 41, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krämer, A.; Maier, B.; Bartek, J. Centrosome Clustering and Chromosomal (In)Stability: A Matter of Life and Death. Mol. Oncol. 2011, 5, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Aurora-A Promotes the Establishment of the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint by Priming the Haspin–Aurora-B Feedback Loop in Late G2 Phase. Cell Discov. 2017, 3, 16049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenn, V.; Musacchio, A. The Aurora B Kinase in Chromosome Bi-Orientation and Spindle Checkpoint Signaling. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giladi, M.; Schneiderman, R.S.; Voloshin, T.; Porat, Y.; Munster, M.; Blat, R.; Sherbo, S.; Bomzon, Z.; Urman, N.; Palti, Y. Mitotic Spindle Disruption by Alternating Electric Fields Leads to Improper Chromosome Segregation and Mitotic Catastrophe in Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoellerbauer, P.; Kufeld, M.; Arora, S.; Ramaswamy, V.; Weng, J.; LaPlant, Q.; Bhat, K.P.L.; Paddison, P.J. FBXO42 Activity Is Required to Prevent Mitotic Arrest, Spindle Assembly Checkpoint Activation and Lethality in Glioblastoma and Other Cancers. NAR Cancer 2024, 6, zcae021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.; Zhu, J.; DeLuca, J.; Paddison, P.J. Kinetochore Misregulation in Glioblastoma and Other Cancers. Neuro-Oncology 2020, 22, ii20–ii21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, M.; Pallotta, M.M.; Musio, A. The Multifaceted Roles of Cohesin in Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, J.-N.; Stasik, S.; Röllig, C.; Sauer, T.; Scholl, S.; Hochhaus, A.; Crysandt, M.; Brümmendorf, T.H.; Naumann, R.; Steffen, B.; et al. Alterations of Cohesin Complex Genes in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körber, V.; Yang, J.; Barah, P.; Wu, Y.; Stichel, D.; Gu, Z.; Fletcher, M.N.C.; Jones, D.; Hentschel, B.; Lamszus, K.; et al. Evolutionary Trajectories of IDH Wild-Type Glioblastomas Reveal a Common Path of Early Tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 692–704.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanu, O.O.; Hughes, B.; Di, C.; Lin, N.; Fu, J.; Bigner, D.D.; Yan, H.; Adamson, C. Glioblastoma Multiforme Oncogenomics and Signaling Pathways. Clin. Med. Oncol. 2009, 3, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-R.; Chen, M.; Pandolfi, P.P. The Functions and Regulation of the PTEN Tumour Suppressor. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leighton, X.; Eidelman, O.; Jozwik, C.; Pollard, H.B.; Srivastava, M. ANXA7-GTPase as Tumor Suppressor: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1513, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Syafruddin, S.E.; Mohtar, M.A.; Wan Mohamad Nazarie, W.F.; Low, T.Y. Two Sides of the Same Coin: The Roles of KLF6 in Physiology and Pathophysiology. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, S.M.B.; Kamel, A.; Ciubotaru, G.V.; Thakur, A.; Mehta, A.; Singh, S.K.; Bhat, K.P.L. EGFR Mechanisms and Targeted Therapies for Glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Guo, D. MET in Glioma: Signaling Pathways and Targeted Therapies. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalfitano, G.; Chatel, M.; Paquis, P.; Michiels, J.F. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization Study of Aneuploidy of Chromosomes 7, 10, X, and Y in Glioblastomas. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2000, 116, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, K.; Arita, H.; Satomi, K.; Yamasaki, K.; Matsushita, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Miyakita, Y.; Umehara, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Tamura, K.; et al. TERT Promoter Mutation Status Is Necessary and Sufficient to Diagnose IDH-Wildtype Diffuse Astrocytic Glioma with Molecular Features of Glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 142, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuss, D.E.; Kratz, A.; Sahm, F.; Capper, D.; Schrimpf, D.; Koelsche, C.; Hovestadt, V.; Bewerunge-Hudler, M.; Jones, D.T.; Schittenhelm, J.; et al. Adult IDH Wild-Type Astrocytomas Biologically and Clinically Resolve into Other Tumor Entities. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 130, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, D.; Lv, Y.; Zheng, J.; Lilljebjörn, H.; Ran, L.; Bao, Z.; Soneson, C.; Sjögren, H.O.; et al. A Glioma Classification Scheme Based on Coexpression Modules of EGFR and PDGFRA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 3538–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Aoki, K.; Chiba, K.; Sato, Y.; Shiozawa, Y.; Shiraishi, Y.; Shimamura, T.; Niida, A.; Motomura, K.; Ohka, F.; et al. Mutational Landscape and Clonal Architecture in Grade II and III Gliomas. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brat, D.J.; Aldape, K.; Bridge, J.A.; Canoll, P.; Colman, H.; Hameed, M.R.; Harris, B.T.; Hattab, E.M.; Huse, J.T.; Jenkins, R.B.; et al. Molecular Biomarker Testing for the Diagnosis of Diffuse Gliomas. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2022, 146, 547–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo, I.; Vital, A.L.; Nieto, A.B.; Rebelo, O.; Tão, H.; Lopes, M.C.; Oliveira, C.; Gonçalves, C.S.; Taipa, R.; Reis, R.M. Detailed Characterization of Alterations of Chromosomes 7, 9, and 10 in Glioblastomas. J. Mol. Diagn. 2011, 13, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.