NMDA Autoimmune Encephalitis and Severe Persistent Hypokalemia in a Pregnant Woman

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

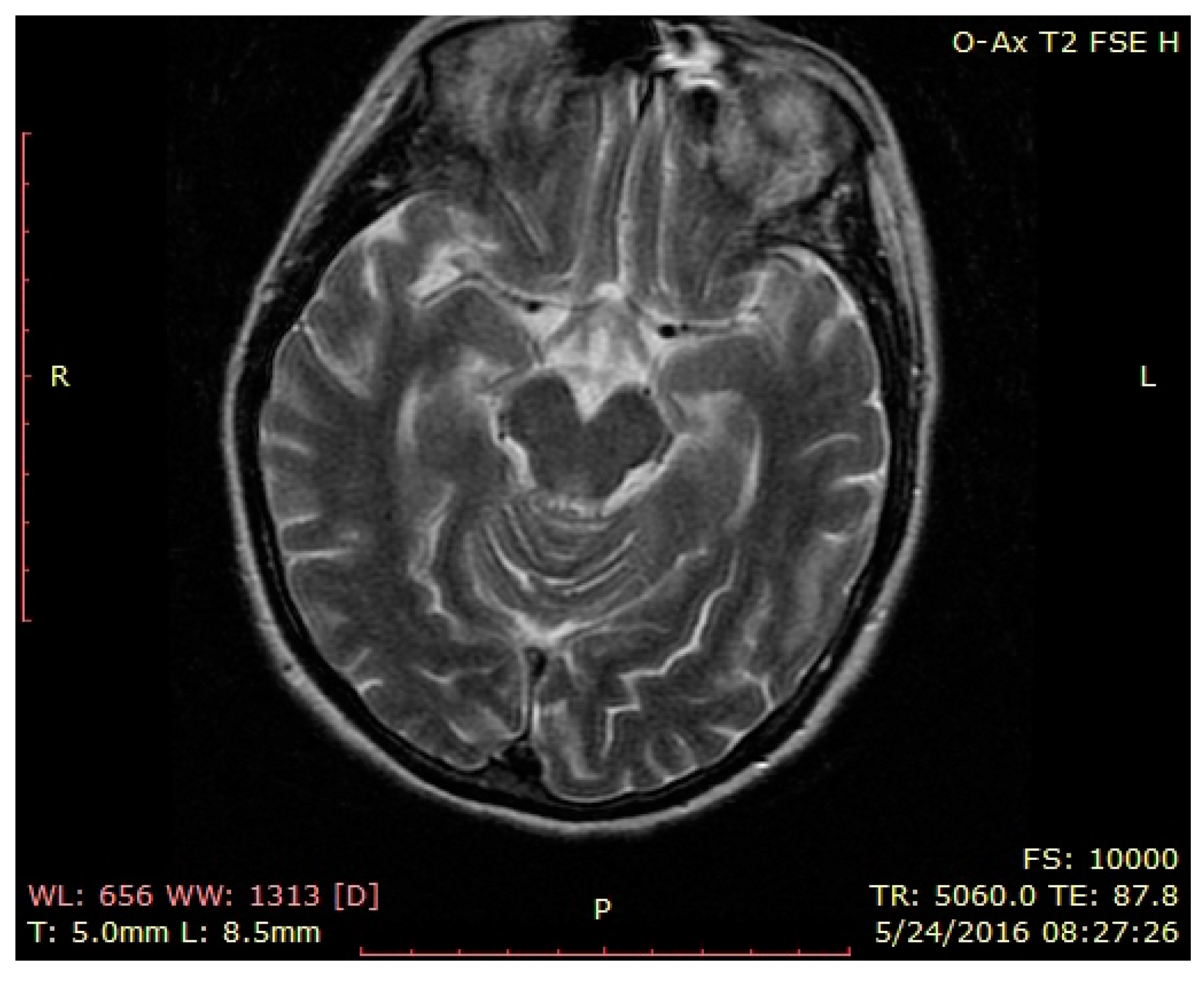

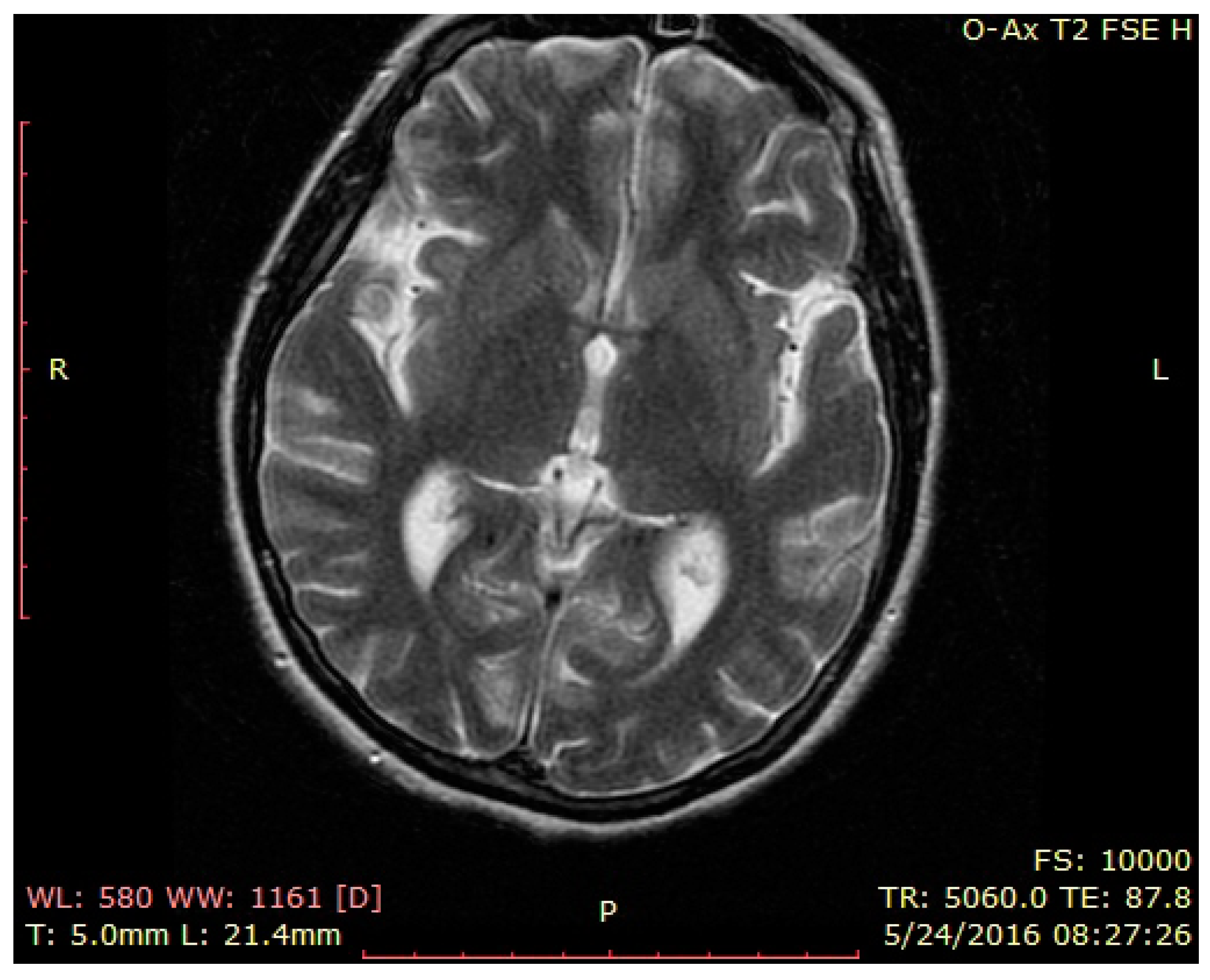

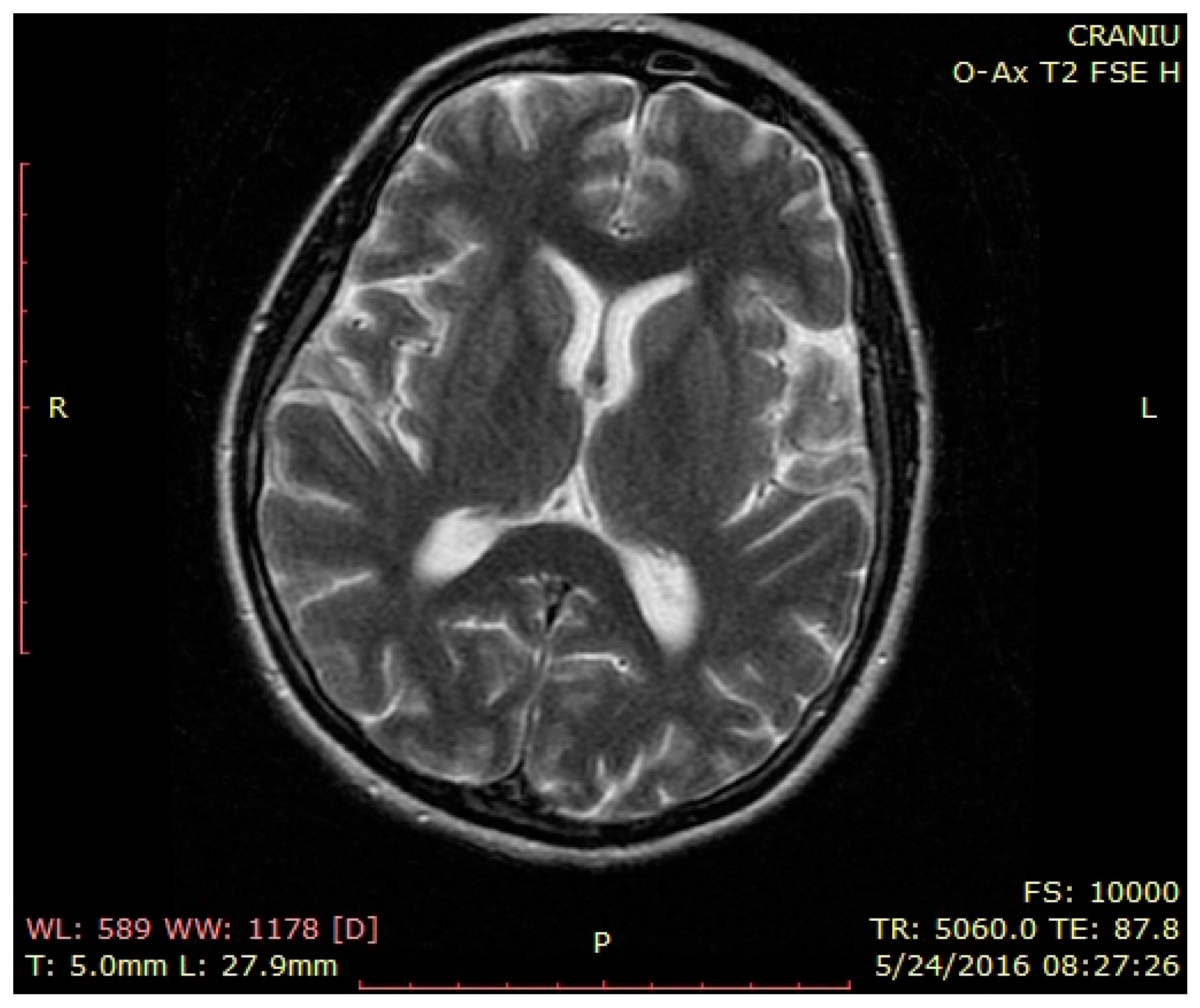

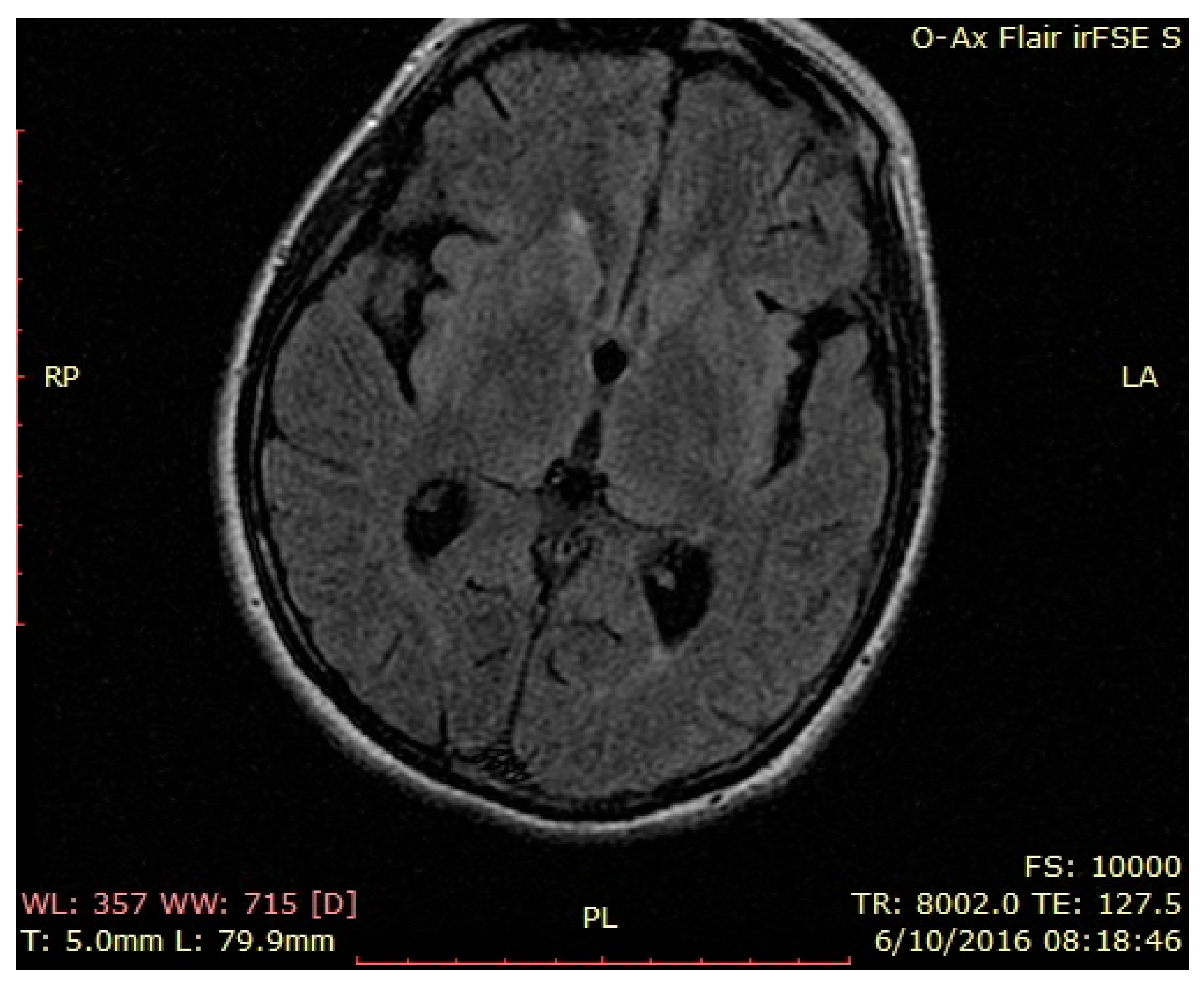

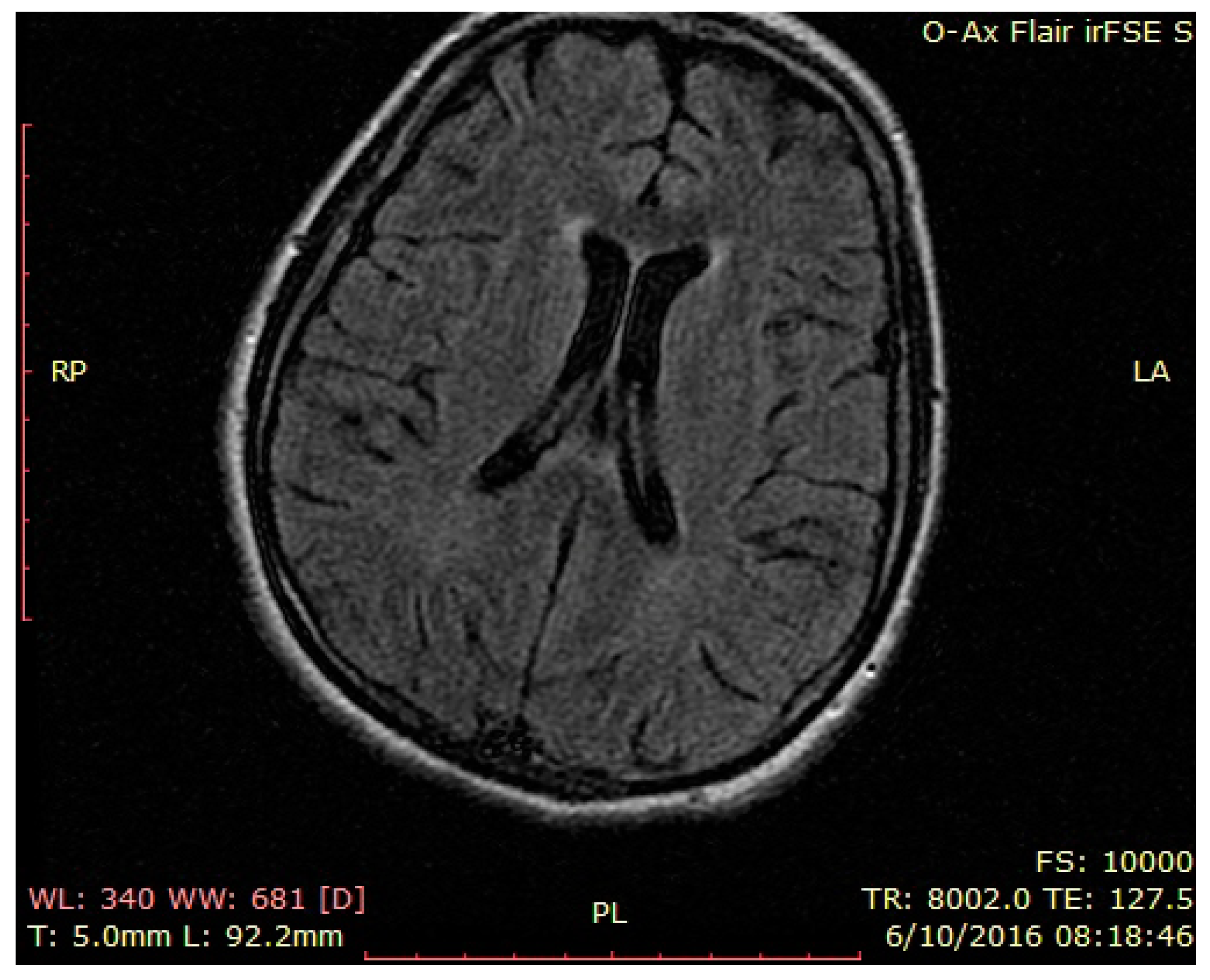

3. Case Presentation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- It attests to the implications of other organs/systems in the general autoimmune process of NMDAR encephalitis.

- It might change the way we address certain psychiatric diseases by searching for underlying organic conditions.

- It could permit the diagnosis of a very probable sub-clinical type of NMDAR encephalitis which can be detected not only psychiatrically, but with abnormal laboratory results.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dalmau, J.; Tüzün, E.; Wu, H.-Y.; Masjuan, J.; Ba, J.E.R.; Voloschin, A.; Baehring, J.M.; Shimazaki, H.; Koide, R.; King, D.; et al. Paraneoplastic Anti-N-methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis Associated with Ovarian Teratoma. Ann. Neurol. 2007, 61, 25–36. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2430743/ (accessed on 25 January 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalmau, J.; Gleichman, A.J.; Hughes, E.G.; Rossi, J.E.; Peng, X.; Lai, M.; Dessain, S.K.; Rosenfeld, M.R.; Balice-Gordon, R.; Lynch, D.R. Anti-NMDA-Receptor Encephalitis: Case Series and Analysis of the Effects of Antibodies. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 1091–1098. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2607118/ (accessed on 25 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Titulaer, M.J.; McCracken, L.; Gabilondo, I.; Armangue, T.; Glaser, C.; Iizuka, T.; Honig, L.S.; Benseler, S.M.; Kawachi, I.; Martinez-Hernandez, E.; et al. Treatment and Prognostic Factors for Long-Term Outcome in Patients with Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis: An Observational Cohort Study. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 157–165. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laneur/article/PIIS1474-4422(12)70310-1/fulltext (accessed on 25 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hogan-Cann, A.D.; Anderson, C.M. Physiological Roles of Non-Neuronal NMDA Receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 37, 750–767. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165614716300554 (accessed on 25 January 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, B.; McDonald, A.; Srinivasan, S. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: A case study and illness overview. Drugs Context 2019, 8, 212589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joubert, B.; García-Serra, A.; Planagumà, J.; Martínez-Hernandez, E.; Kraft, A.; Palm, F.; Iizuka, T.; Honnorat, J.; Leypoldt, F.; Graus, F.; et al. Pregnancy outcomes in anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: Case series. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflammation 2020, 7, e668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggio, M.C.; Mastrangelo, G.; Skabar, A.; Ventura, A.; Carrozzi, M.; Santangelo, G.; Vanadia, F.; Corsello, G.; Cimaz, R. Atypical presentation of anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis: Two case reports. J. Med. Case Rep. 2017, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrou, M.; Yeo, J.M.; Slater, A.D.; Koch, O.; Irani, S.; Foley, P. Case report: Meningitis as a presenting feature of an-ti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, K.; Wu, W.; Huang, Y.; Xu, D.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, B.; Jiang, M.; Kou, C.; Gao, J.; Li, W.; et al. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor(NMDAR) antibody encephalitis presents in atypical types and coexists with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder or neurosyphilis. BMC Neurol. 2017, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosadini, M.; Shekeeb, S.M.; Ruga, E.M.; Kothur, K.; Perilongo, G.; Frigo, A.C.; Toldo, I.; Dale, R.C.; Sartori, S. Herpes simplex virus-induced anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis: A systematic literature review with analysis of 43 cases. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 58, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, G.; Giovannini, G.; Marudi, A.; Bedin, R.; Melegari, A.; Simone, A.M.; Santangelo, M.; Pignatti, A.; Bertellini, E.; Trenti, T.; et al. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis presenting as new onset refractory status epilepticus in COVID-19. Seizure 2020, 81, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burr, T.; Barton, C.; Doll, E.; Lakhotia, A.; Sweeney, M. N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis Associated With COVID-19 Infection in a Toddler. Pediatr. Neurol. 2021, 114, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, C.V.; Theel, E.; Binnicker, M.; Toledano, M.; McKeon, A. Autoimmune Encephalitis After SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Case Frequency, Findings, and Outcomes. Neurology 2021, 97, e22262–e22268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejuste, F.; Thomas, L.; Picard, G.; Desestret, V.; Ducray, F.; Rogemond, V.; Psimaras, D.; Antoine, J.-C.; Delattre, J.-Y.; Groc, L.; et al. Neuroleptic intolerance in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflammation 2016, 3, e280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, K.; Sapkota, K. The origin of NMDA receptor hypofunction in schizophrenia. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 205, 107426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-W.; Li, S.; Dong, Y. The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Hypokalemia in Pregnancy-Related Hospitalizations: A Nationwide Population Study. Int. J. Nephrol. 2021, 2021, 9922245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdivielso, J.M.; Eritja, A.; Caus, M.; Bozic, M. Glutamate-Gated NMDA Receptors: Insights into the Function and Signaling in the Kidney. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, A.; Bockenhauer, D.; Bolignano, D.; Calò, L.A.; Cosyns, E.; Devuyst, O.; Ellison, D.; Frankl, F.E.K.; Knoers, N.V.; Konrad, M.; et al. Gitelman syndrome: Consensus and guidance from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çetik, S.; Basaran, N.C.; Ozisik, L.; Oz, S.G.; Arici, M. Gitelman Syndrome Diagnosed in a Woman in the Second Trimester of Pregnancy. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2019, 6, 001100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, M.A.; Mukhtar, M.; Ahmed, A.; Ullah, W.; Saeed, R.; Hamid, M. Gitelman Syndrome: A Rare Cause of Seizure Disorder and a Systematic Review. Case Rep. Med. 2019, 2019, 4204907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reisz, D.; Gramescu, I.-G.; Mihaicuta, S.; Popescu, F.G.; Georgescu, D. NMDA Autoimmune Encephalitis and Severe Persistent Hypokalemia in a Pregnant Woman. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020221

Reisz D, Gramescu I-G, Mihaicuta S, Popescu FG, Georgescu D. NMDA Autoimmune Encephalitis and Severe Persistent Hypokalemia in a Pregnant Woman. Brain Sciences. 2022; 12(2):221. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020221

Chicago/Turabian StyleReisz, Daniela, Iulia-Gabriela Gramescu, Stefan Mihaicuta, Florina Georgeta Popescu, and Doina Georgescu. 2022. "NMDA Autoimmune Encephalitis and Severe Persistent Hypokalemia in a Pregnant Woman" Brain Sciences 12, no. 2: 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020221

APA StyleReisz, D., Gramescu, I.-G., Mihaicuta, S., Popescu, F. G., & Georgescu, D. (2022). NMDA Autoimmune Encephalitis and Severe Persistent Hypokalemia in a Pregnant Woman. Brain Sciences, 12(2), 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020221