Featured Application

Potential applications of the work include novel AI-based optimization methods for 3D-printed assistive devices, especially hand exoskeletons.

Abstract

3D-printed hand exoskeletons are important because they enable the creation of affordable, lightweight, and highly customizable assistive and rehabilitation devices tailored to individual patient needs. Their rapid production and design flexibility accelerate innovation, improve access to therapies, and accelerate functional recovery for people with hand impairments. This article discusses the development of a hand exoskeleton using advanced additive manufacturing. It highlights how Industry 4.0 principles such as digital design, automation, and smart manufacturing enable precise prototyping and efficient use of materials. Moving on to Industry 5.0, the study highlights the role of human–machine collaboration, where customization and ergonomics are prioritized to ensure user comfort and rehabilitation effectiveness. The integration of AI-based generative design and digital twins (DTs) is explored as a path to Industry 6.0, where adaptive and self-optimizing systems support continuous improvement. The perspective of personal experience provides insight into practical challenges, including material selection, printing accuracy, and wearability. The results show how technological optimization can be used to reduce costs, improves efficiency and sustainability, and accelerates the personalization of medical devices. The article shows how evolving industrial paradigms are driving the design, manufacture, and refinement of 3D-printed hand exoskeletons, combining technological innovation with human-centered outcomes.

1. Introduction

The genesis of material and technological optimization for 3D-printed hand exoskeletons emerges from the intersection of additive manufacturing and cyber–physical systems, which are key to the Industry 4.0 paradigm [1]. It begins with the application of digital twins (DTs), which allow designers to simulate biomechanical behavior before printing any physical prototype [2]. Advances in smart materials enable the creation of lightweight yet robust structures that adapt to user-specific movement patterns [3]. Polymers with embedded sensors introduce real-time feedback loops, enhancing both ergonomic comfort and functional precision [4]. Cloud-connected design platforms facilitate collaborative refinement between engineers, medical specialists, and users [5]. In the transformation toward Industry 5.0, human-centered principles drive personalization based on individual anatomical and rehabilitation needs [6]. Artificial intelligence-assisted optimization algorithms learn from user interaction data to continuously refine the geometry and material layout [7]. Sustainable biopolymers and recyclable composites further align exoskeleton development with the environmental priorities of the newer industrial paradigm [8]. With the emergence of Industry 6.0, quantum-enhanced simulations are accelerating the exploration of new material combinations and structural configurations [9]. The evolution of the exoskeleton reflects the synergy of multiple paradigms, where advanced technologies serve human well-being through intelligent, adaptive, and sustainable design [10].

Significant scientific gaps remain in the material and technological optimization of 3D-printed hand exoskeletons in the context of the Industry 4.0, 5.0, and 6.0 paradigms. Knowledge about the behaviors of emerging smart materials under the prolonged, cyclic biomechanical loading typical of everyday hand use remains lacking [11].Current digital twin models lack the accuracy necessary to fully capture the nonlinear interactions between soft tissues, actuators, and additively manufactured components [12]. Multi-material 3D printing processes remain insufficiently characterized, hindering the optimization of stiffness, flexibility, and durability gradients [13]. Real-time sensor integration is also limited by the lack of standardized protocols for embedding electronics into complex printed geometries [14]. Human-centric personalization, which is crucial for Industry 5.0, is hampered by gaps in translating user-specific ergonomic and neurological data into manufacturable design parameters [15]. Sustainability assessments for medical-grade polymers and composites compatible with additive manufacturing are incomplete, especially in the context of a circular economy [16]. AI-based optimization frameworks lack sufficiently large and representative datasets to generate reliable design recommendations [17]. Early Industry 6.0 concepts, such as quantum-enhanced material simulations, remain largely theoretical, with unclear paths to their practical application. These gaps underscore the need for interdisciplinary research integrating materials science, biomechanics, manufacturing technologies, and human–system integration [18].

The novelty and contribution to the material and technological optimization of a 3D-printed hand exoskeleton require breakthrough solutions aligned with the evolving principles of Industry 4.0, 5.0, and 6.0. A key innovation is the development of fully adaptive multi-material printing methods, enabling seamless transitions between rigid and flexible zones, adapted to anatomical movement. Integrating high-resolution digital twins capable of modeling user-specific biomechanics would significantly increase design accuracy and clinical applicability. New contributions are also needed to create embedded sensor networks that self-calibrate and wirelessly communicate with cyber–physical systems to monitor performance in real-time [19,20]. Human-centric optimization tools, inspired by Industry 5.0, must incorporate data on user comfort, cognitive load, and emotions to improve exoskeleton usability [21]. Sustainable material innovations—such as biopolymers and closed-loop recycling strategies—which remain underexplored in the context of assistive device manufacturing would bring ecological value. AI-based design engines could advance the technology by autonomously generating optimized geometries based on mechanical, ergonomic, and sustainability metrics [22]. Interoperability frameworks enabling seamless data exchange between clinicians, engineers, and users would streamline the collaborative personalization process [23]. In the wake of Industry 6.0, quantum material discovery and ultra-intelligent design systems could usher in entirely new classes of exoskeleton architectures. Together, these solutions would not only advance cutting-edge technologies but also redefine how assistive devices are designed, manufactured, and integrated into human life [24].

Within the framework of Industry 4.0, additive manufacturing (3D printing) has transformed product design and manufacturing processes across a wide range of industries [25]. The evolution of 3D printing and its contribution to industrial innovation have already been widely explored, with examples in the fields of aerospace, automotive, and biomedicine [26]. Major additive manufacturing (AM) processes—such as binder jetting, direct energy deposition, and powder fusion—have been examined in the context of materials such as metals, polymers, ceramics, and composites, with new techniques such as rapid sintering, continuous fluidic interface production, and bioprinting having been highlighted [27]. This technology’s ability to create complex geometries and its material versatility make it particularly promising for personalized medical applications, although issues related to standardization, material quality, sustainability, recycling, and cost remain significant barriers to its widespread implementation [28]. By addressing these challenges and outlining future developments such as 4D and 5D printing, 3D printing is positioned as a key driver of Industry 5.0, with an emphasis on sustainability and human–machine collaboration [29]. In the study by Martinez-Cano et al., density functional theory (DFT) was used to investigate the electronic and vibrational properties of molecular complexes formed between glycerol monoacetate (monoacetin) and short-chain starch polymers; namely, amylose and amylopectin. All calculations were performed using the B3LYP functional with a 6–31G basis set, considering neutral systems with singlet multiplicity. Two interaction configurations were proposed: lateral interactions and linear interactions. The results indicate that all complexes are energetically stable, with exothermic adsorption processes, and thermodynamic and quantum molecular analyses identified the monoacetin–amylose tetramer complex as the most stable, exhibiting spontaneous chemisorption. Additionally, theoretical FT-IR spectra were generated for all complexes, providing potential reference data for future experimental and theoretical studies [30].

The aim of this study is to identify the current and future potential of AI-based optimization in the design and production of 3D-printed hand exoskeletons, as well as to assess the extent to which such methods are available and applied in their technological optimization. This enables the evaluation and possible adjustment of development directions for this group of technologies, while considering both material and process optimization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

The objective of our bibliometric analysis was to explore both the research landscape and the associated knowledge base engineering practices related to the material and technological optimization of (typically personalized) hand-held exoskeletons manufactured using additive manufacturing. For this purpose, we applied bibliometric methods to analyze scientific publication databases and answer the following research questions (RQs):

- RQ 1: How are additive manufacturing methods currently used to produce exoskeletons, including wrist exoskeletons?

- RQ 2: What research gaps, material and technological constraints, and unexplored opportunities currently exist within this interdisciplinary field?

- RQ 3: What new developments in this area are currently being researched or implemented?

- RQ 4: To what degree do current solutions satisfy the required criteria of Industry 4.0/5.0 and eHealth?

This analysis was performed to identify key areas, including the current state of knowledge, the origin and evolution of research topics, the origin of publications (institutions, country, and—where possible—funding sources), and the most influential authors and articles, taking into account their recency. This approach allowed us to obtain a comprehensive picture of current research and industry trends in the analyzed area of digital transformation, Industry 4.0/5.0, and eHealth. The obtained results of the analysis and interpretation of bibliometric data are expected to enrich current discussions and conclusions and create a stronger foundation for future research.

2.2. Methods

For this study, four major bibliographic databases were searched: Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, PubMed, and dblp. These databases were chosen for their extensive coverage and comprehensive citation data, enabling a detailed bibliometric analysis of the research area of material and technological optimization of 3D-printed wrist exoskeletons (Table 1). Appropriate search filters were applied to focus on selected literature, limiting the search results to original and review articles published in English. After this initial filtering, each article was manually assessed against predefined inclusion criteria to determine the final sample size. Three reviewers took part in the manual screening process, with inclusion or exclusion decisions made independently based on a majority vote. Any discrepancies were resolved through agreement by at least two of the three reviewers. Subsequently, key characteristics of the dataset were analyzed, including leading authors, research groups and institutions, contributing countries, thematic clusters, and emerging trends. This approach enabled the mapping of the evolution of key terminology and major research advances within the analyzed field. Where feasible, temporal trends were examined to track changes in research focus over time, and publications were organized into thematic clusters to uncover links between different research areas. This process facilitated the identification of the most significant topics and subdisciplines within the studied research domain.

Table 1.

Bibliometric analysis procedure (own approach used in this study).

The study is based on a selection of 10 items from the PRISMA 2020 guidelines for bibliographic reviews (PRISMA 2020 checklist in the Supplementary Materials). The following aspects were considered: justification (item 3), purpose(s) (item 4), eligibility criteria (item 5), information sources (item 6), search strategy (item 7), selection process (item 8), data collection process (item 9), synthesis methods (item 13a), synthesis results (item 20b), and discussion (item 23a).Bibliometric analysis was performed using tools embedded in the Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, PubMed, and dblp databases. This selected review methodology allows for improved categorization by concepts (keywords), research areas, authors/teams, affiliations, countries, documents, and sources.

2.3. Data Selection

In WoS, searches were conducted using the “Subject” field (consisting of title, abstract, keyword, and other keywords); in Scopus, using the article title, abstract, and keywords; and in PubMed and dblp, using manual keyword sets. Articles were searched in the databases using keywords—the best set of keywords was “additive manufacturing” AND exoskeleton AND optimization OR optimisation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Detail search query (in all four databases).

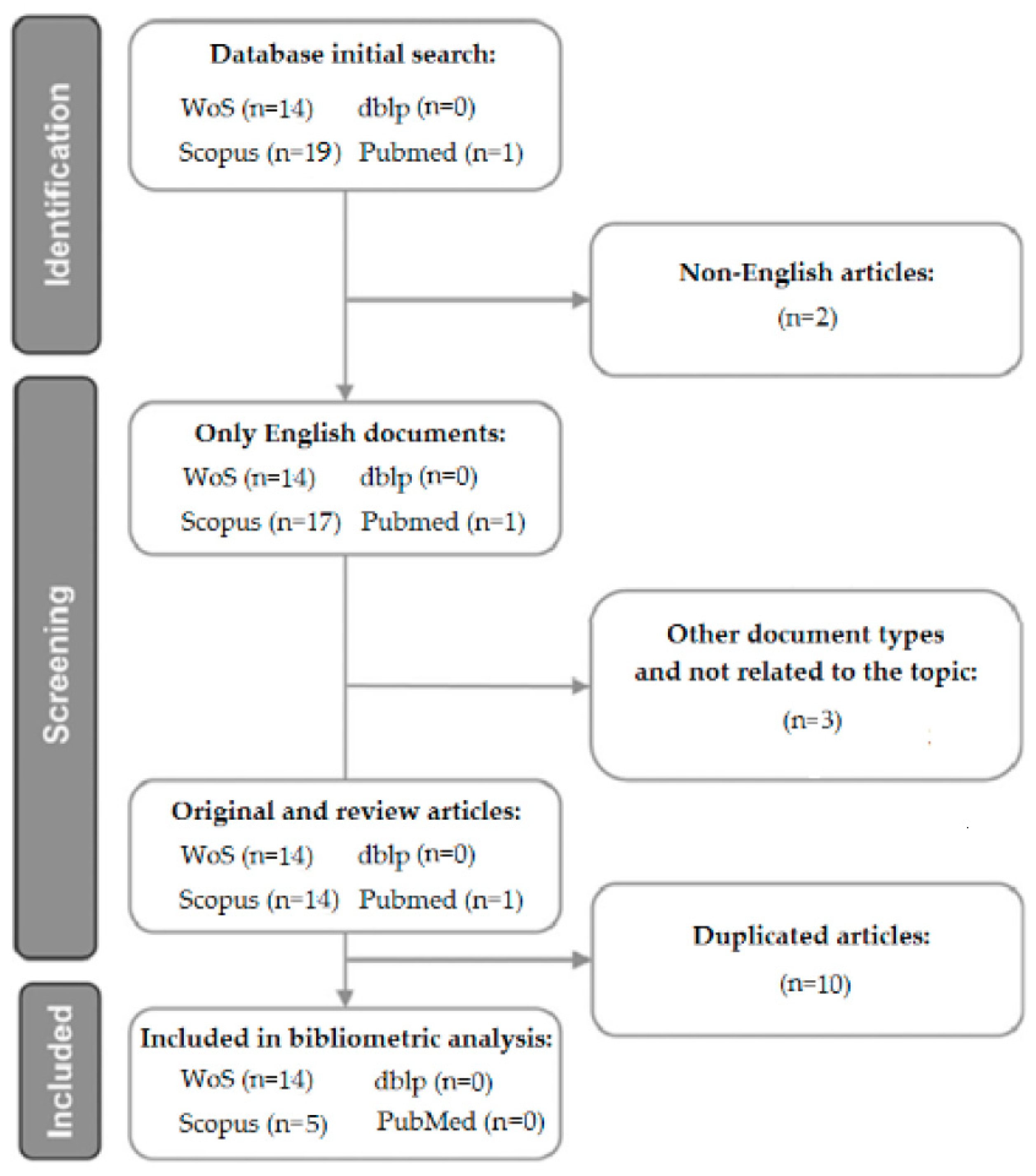

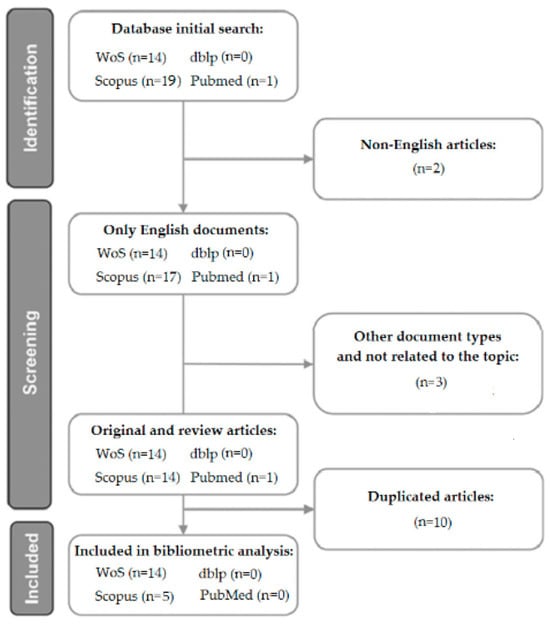

The selected set of publications underwent additional verification by manually re-screening articles, removing irrelevant items and duplicates, which allowed us to determine the final sample size (Figure 1). We used a combination of assessment tools to ensure the reliability and validity of the articles.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

The aforementioned PRISMA 2020 flowchart provides a clear, step-by-step overview of the process of identifying, selecting, assessing, and ultimately including studies in the review, ensuring methodological accuracy and reproducibility. It begins with the identification phase, which involves collecting data from databases and other sources, capturing the total volume of potentially relevant literature before removing duplicates. Next, in the screening phase, titles and abstracts are filtered based on predefined eligibility criteria, eliminating studies that are clearly not related to wearable devices based on machine learning or digital transformation technologies. Next, in the eligibility phase, full-text articles are thoroughly assessed for methodological quality, adequacy of data collection and security, and relevance to topics such as NLP or genAI. Finally, the inclusion phase shows how many articles remain after exclusion, which constitutes the evidence base used for synthesis and analysis. Interpreting the PRISMA diagram allows for a better understanding of the transparency of the review because it shows not only the volume of literature analyzed but also the rationale for each exclusion step, which strengthens the validity of the conclusions.

3. Results

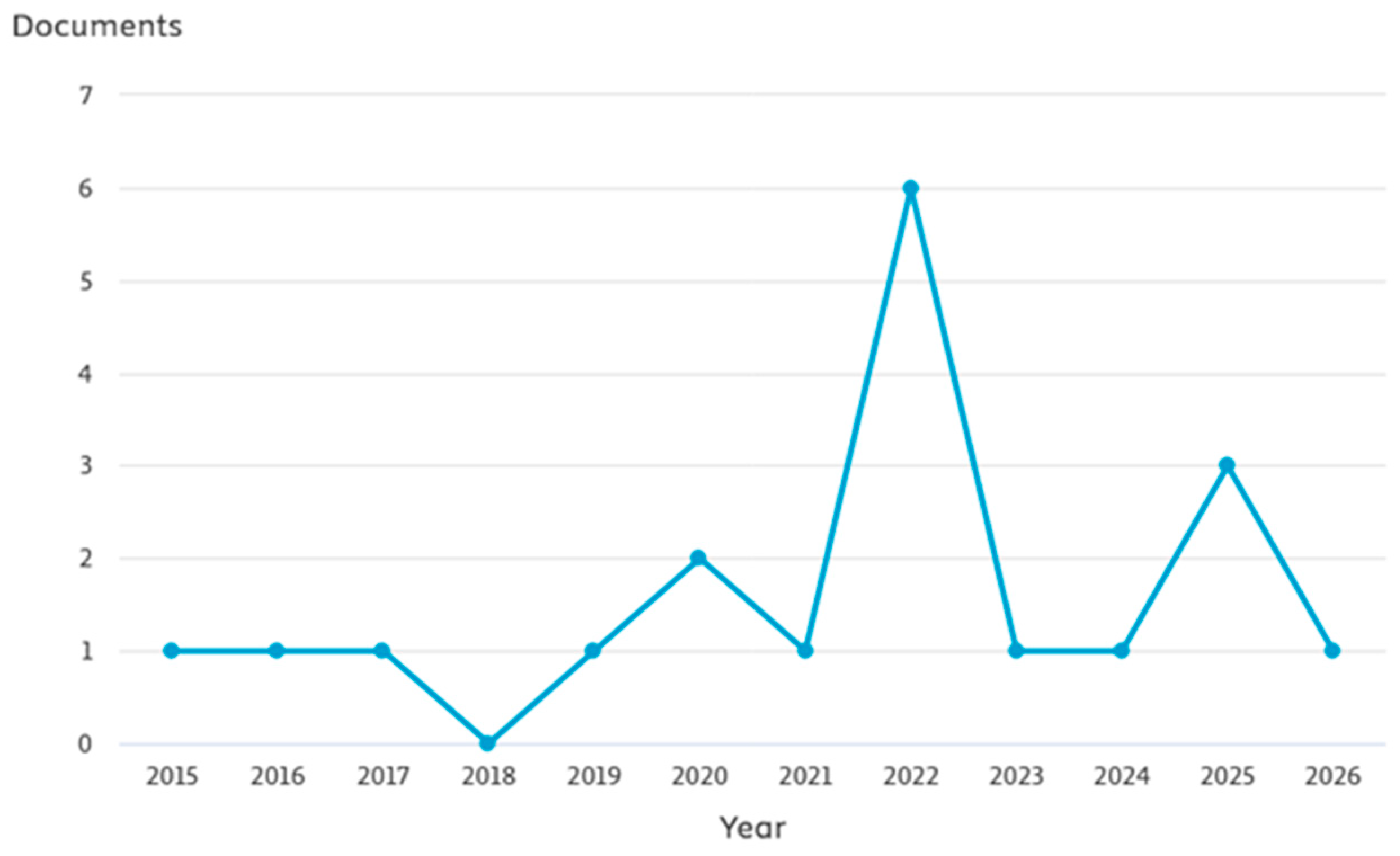

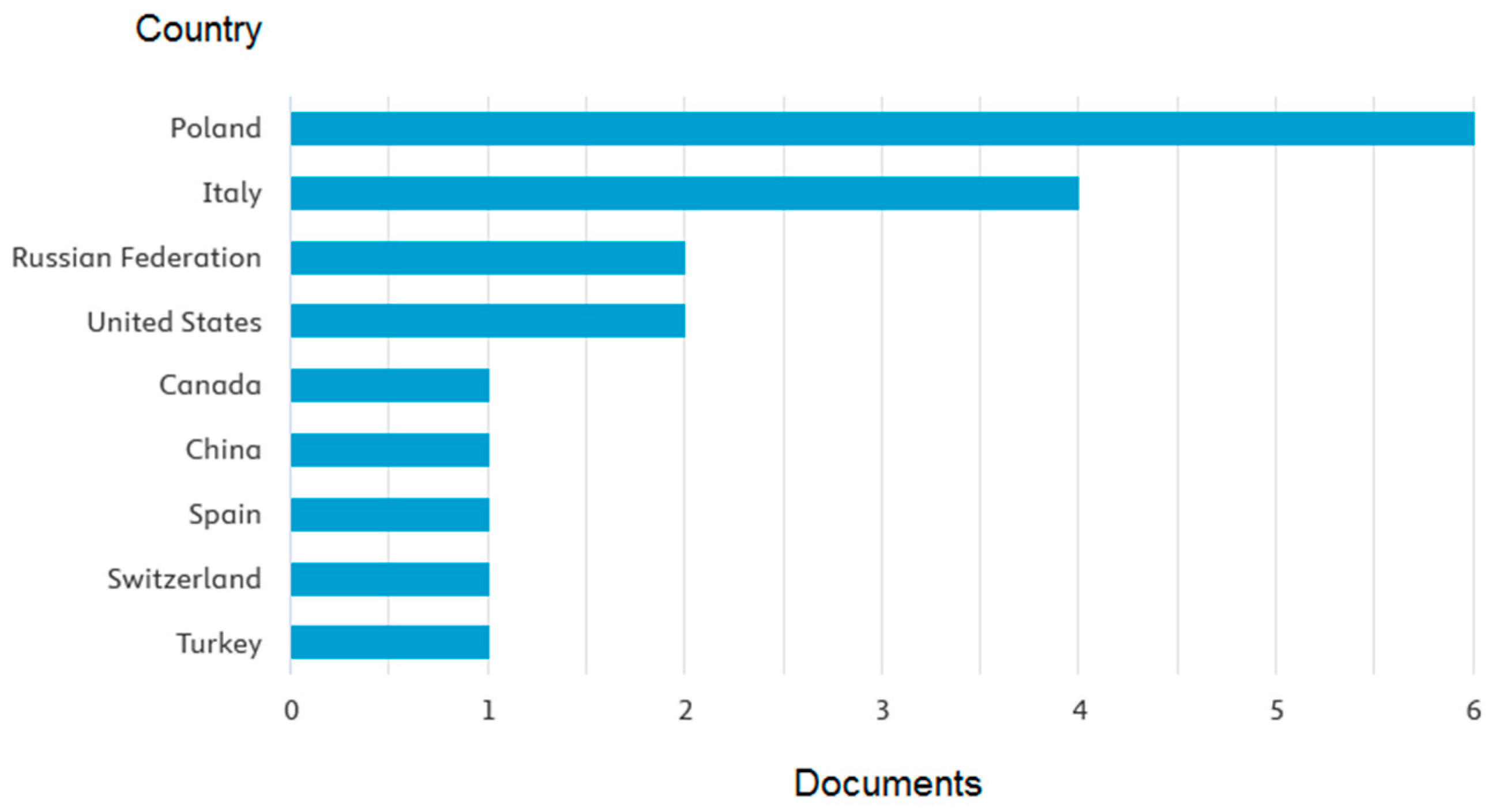

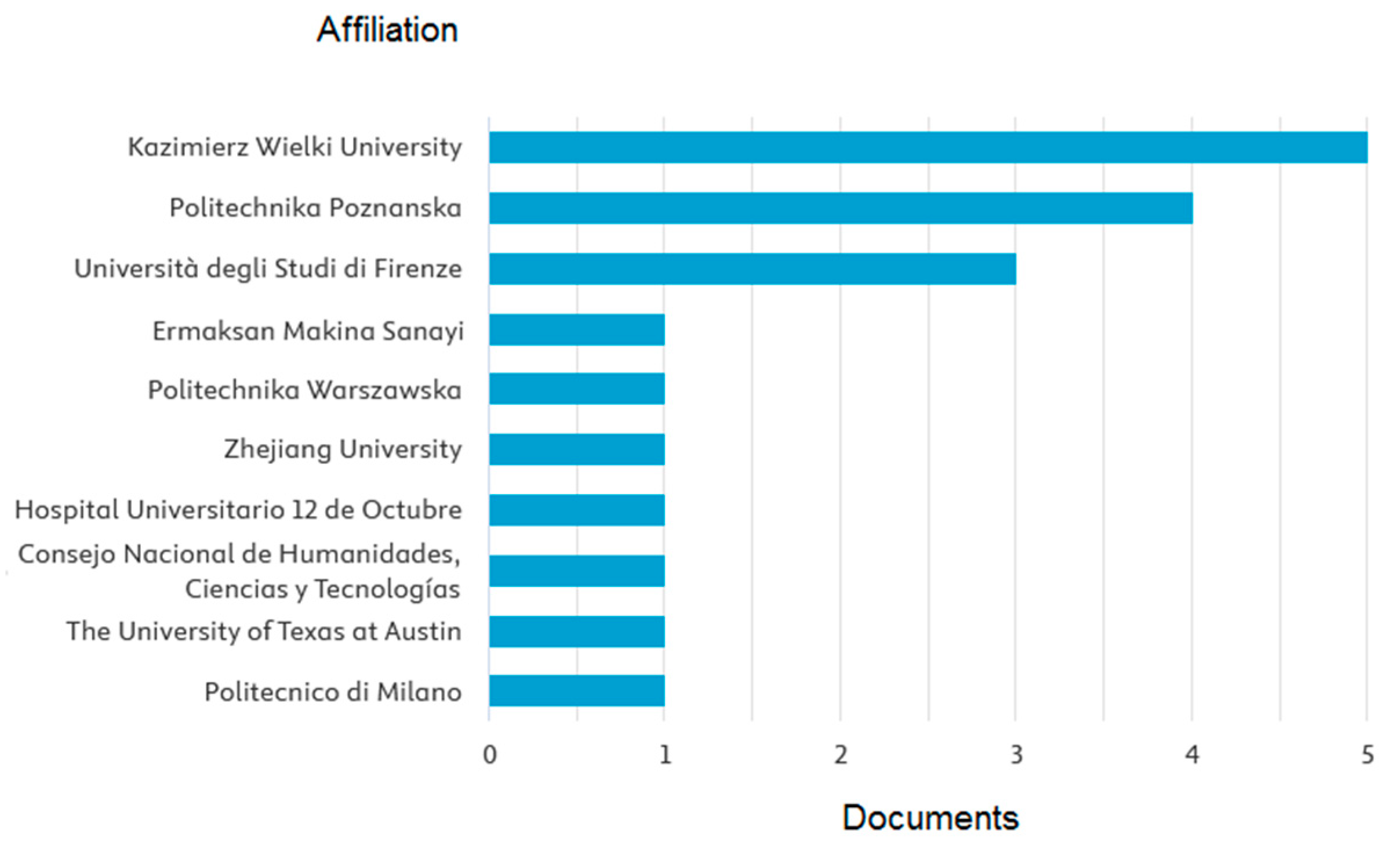

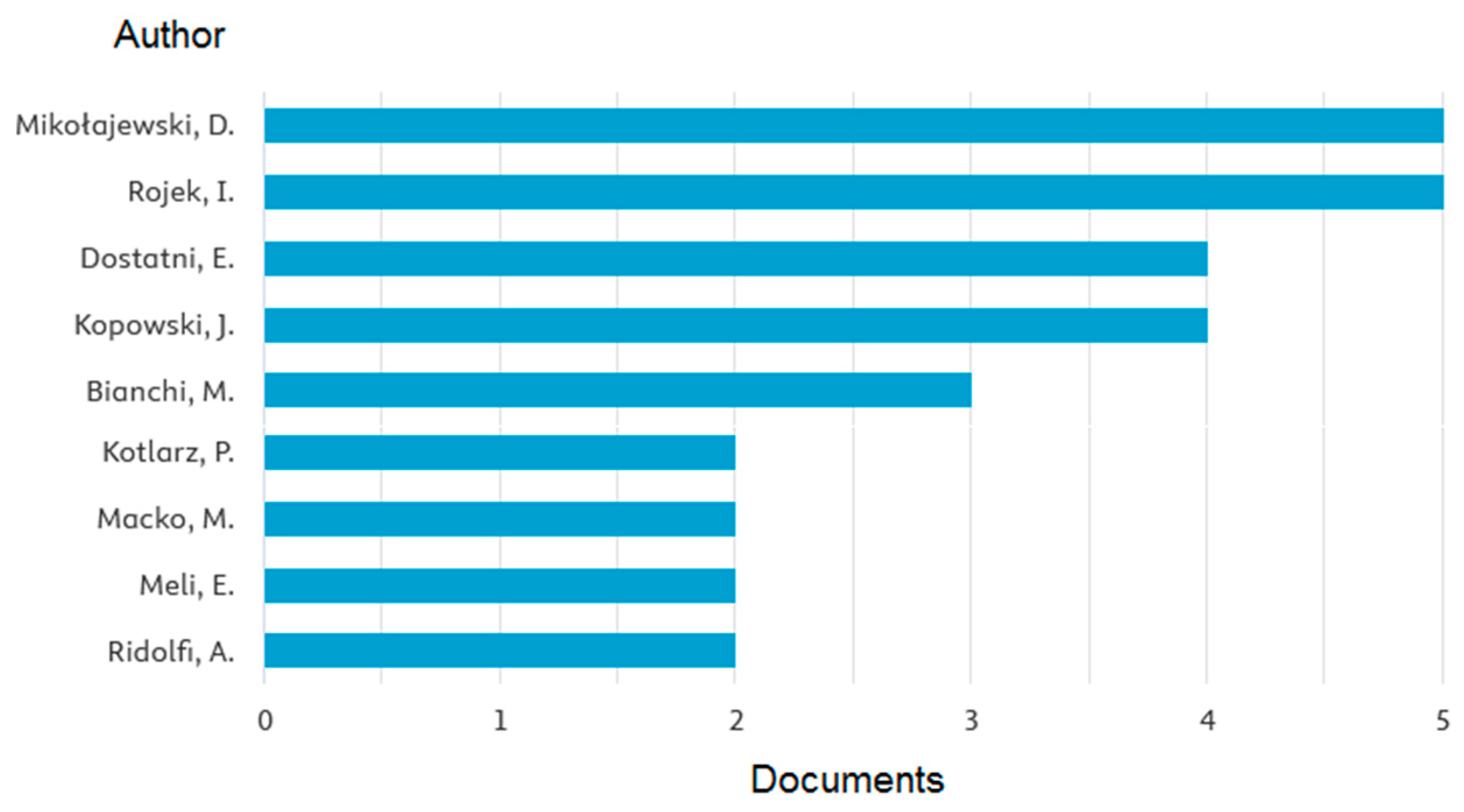

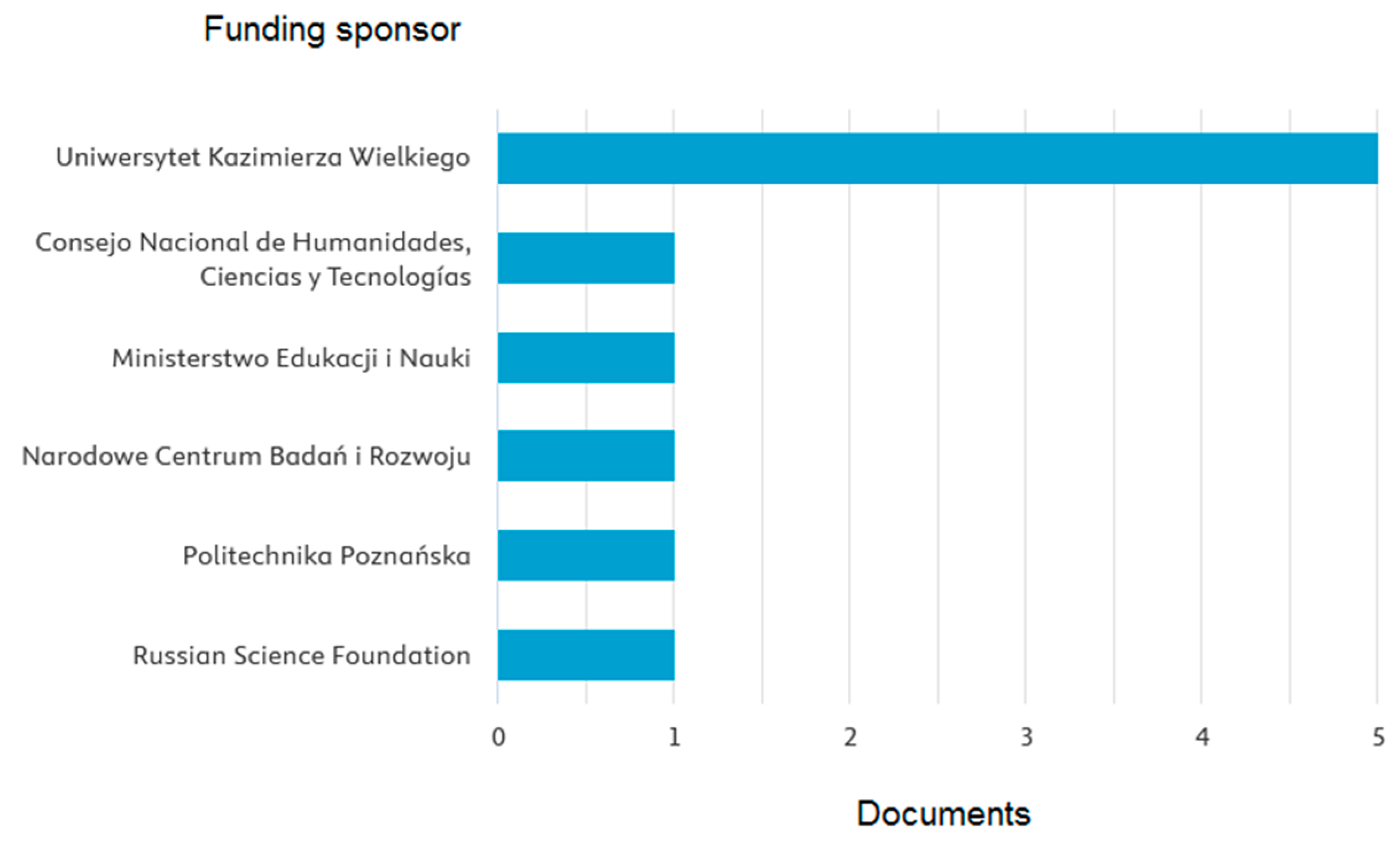

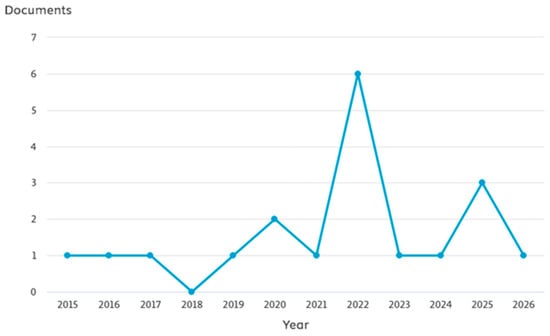

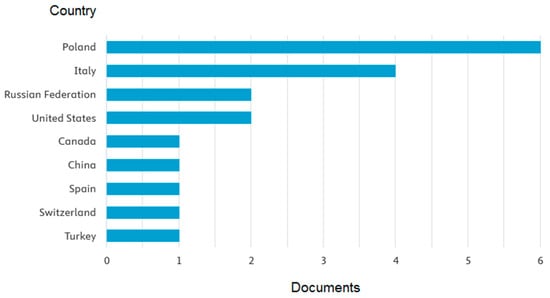

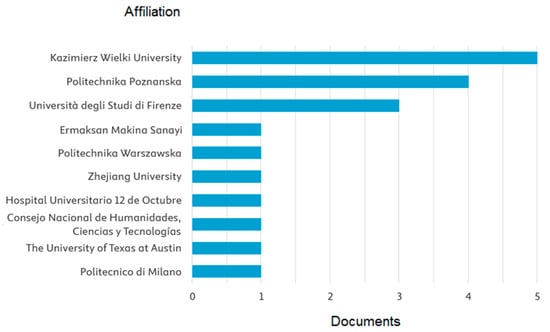

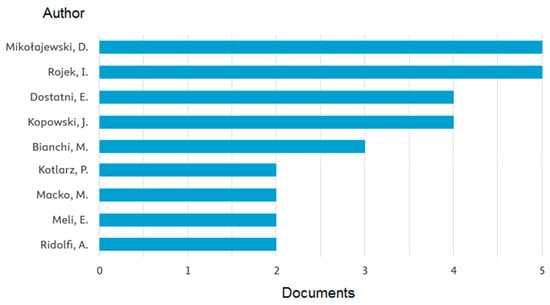

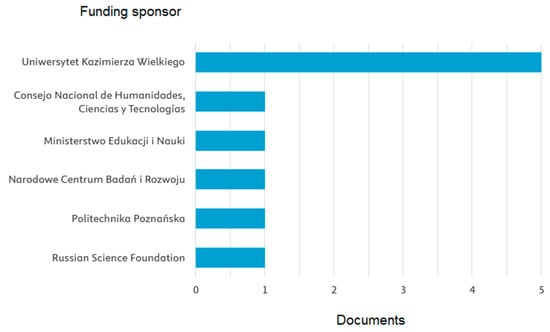

A general summary of the bibliographic analysis results is presented in Table 3 and Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8. The review included 19 articles published between 2016 and 2026. Articles published before 2016 were omitted because the integration of AI-optimized 3D printing into assistive technologies such as hand exoskeletons is a relatively new field of research. The literature was limited to studies published after 2016, as this period is characterized by the rapid development of additive manufacturing, smart materials, and cyber-physical systems, which are key to Industry 4.0 and subsequent paradigms. Before 2016, 3D-printed hand exoskeletons were largely experimental, with limited integration of real-time sensors, data-driven optimization, and human-centered design, making earlier work less representative of current technological capabilities. This timeframe also aligns with the emergence of Industry 5.0 and early Industry 6.0 concepts, which emphasize personalization, sustainability, and human–machine collaboration—key aspects of material and technological optimization in wearable robotics. Reference verification was necessary to ensure that the cited works are methodologically sound, technologically relevant, and consistent with the rapid development of materials, printing techniques, and control strategies in this field. Some limited self-citations are warranted because the authors’ prior work directly addresses specific design iterations, experimental insights, and optimization frameworks that are not fully addressed in the broader literature and also provides important continuity and personal experience within the research path. Significant progress in the field of AI/ML-based optimization has only been more widely applied to the digital transformation of the industry in the last few years. Including older studies would risk being influenced by outdated methods or technologies that do not reflect current capabilities and trends. Therefore, the 2016–2026 timeframe ensures that the review focuses on the most relevant, innovative, and technically feasible approaches.

Table 3.

Summary of results of a bibliographic analysis (in all four databases).

Figure 2.

Publications by year.

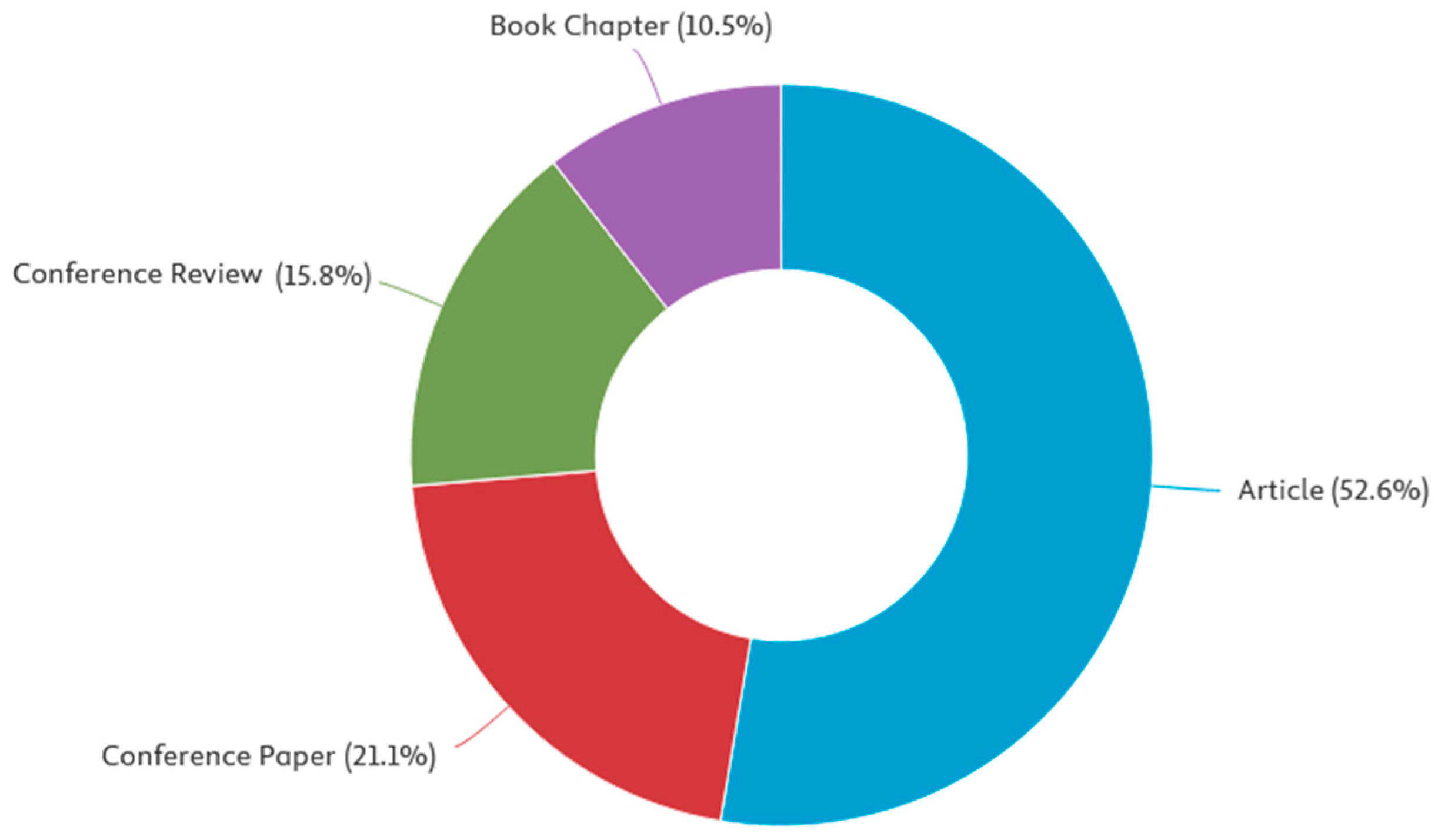

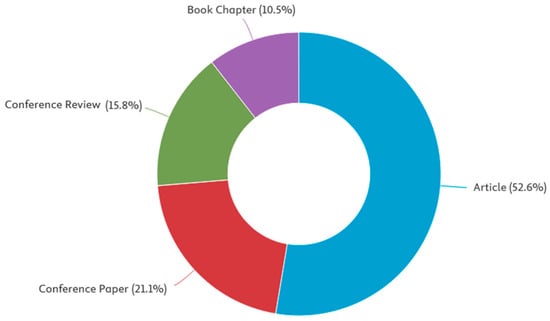

Figure 3.

Publications by type.

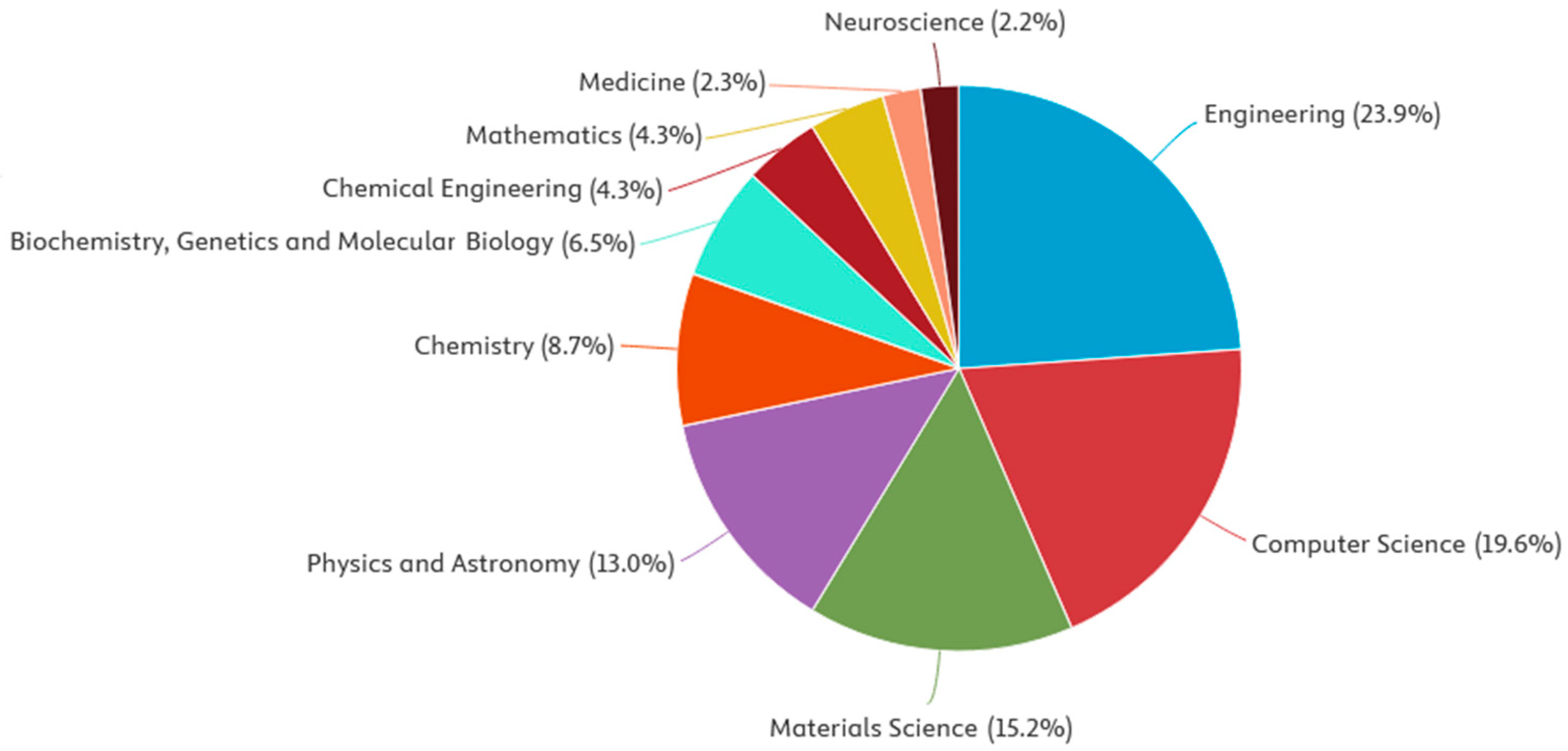

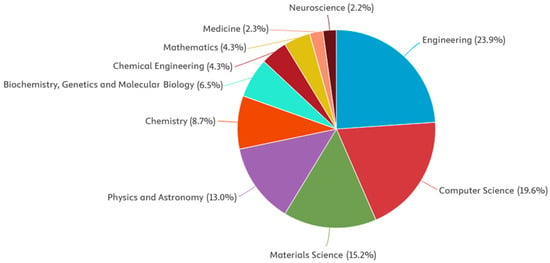

Figure 4.

Publications by area.

Figure 5.

Publications by country.

Figure 6.

Publications by affiliation.

Figure 7.

Publications by author.

Figure 8.

Publications by funding.

The bibliometric results indicate that the large share of journal articles, conference papers, and conference reviews may reflect a research area transitioning out of the conceptual stage, which supports the article’s focus on both proposed architectures and their clinical validation. Nevertheless, the majority of studies originate from computer science, engineering, and materials science rather than from medicine and healthcare, pointing to a relatively early level of technological maturity. The leading countries were Poland and Italy; however, these countries did not have a high number of publications despite recording leading researchers and affiliations, suggesting significant research fragmentation. The most frequently observed Sustainable Development Goals indicate an industrial context, focusing on “innovation and industrial infrastructure.” Only a small number of the reviewed publications explicitly referenced the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as this was not an inclusion criterion. In some countries and research institutions, reporting SDGs is not mandatory. Nevertheless, considering studies both with and without SDG references enables the review to capture a broader range of perspectives, including how SDGs are addressed and any limitations—whether intentional or unintentional—imposed by researchers, countries, or institutions within the context of sustainable development [31,32].

3.1. Key Areas of Material Optimization

Key areas of material optimization for 3D-printed hand exoskeletons within the paradigms of Industry 4.0, 5.0, and 6.0 include performance, sustainability, and human-centric innovation. One key area is the development of multi-material printing strategies that enable seamless transitions between rigid structural zones and flexible connections. Another goal is to develop lightweight, high-strength polymers and composites that increase durability without compromising user comfort [33]. Smart materials with embedded sensors or shape memory represent an emerging field that enables adaptive stiffness shaping and real-time feedback [34]. Materials simulation based on digital twins supports predictive optimization and accelerates design iterations. Human-centric Industry 5.0 principles promote biocompatible, skin-friendly materials that reduce irritation during prolonged wear. Sustainability remains a key area, driving research into polymers that are recyclable, biodegradable, or ready for the circular economy [35]. Materials optimization also requires innovation in internal lattice structures that balance strength, ventilation, and ergonomic fit [36]. Artificial intelligence-assisted material selection and optimization tools help to identify ideal combinations for personalized performance (Table 4) [37]. In the beginning of Industry 6.0, quantum-enhanced simulation could open up unprecedented avenues for discovering new polymer behaviors and microstructures.

Table 4.

Materials commonly used in 3D-printed hand exoskeletons, covering rigid structures, soft/active components, and emerging bio-inspired materials (e.g., hydrogels, polysaccharides, and macromolecules).

3.2. Key Areas of Technological Optimization

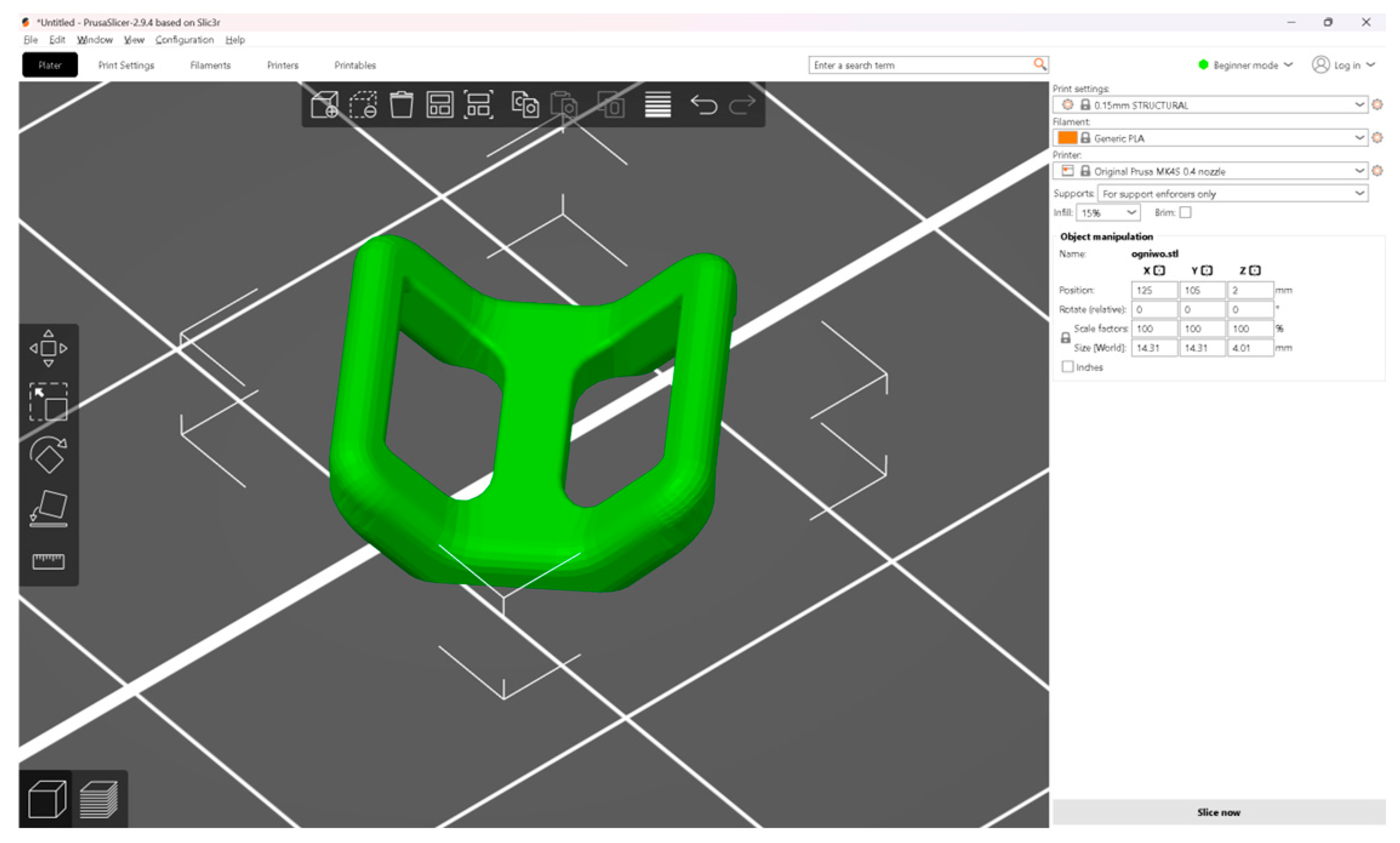

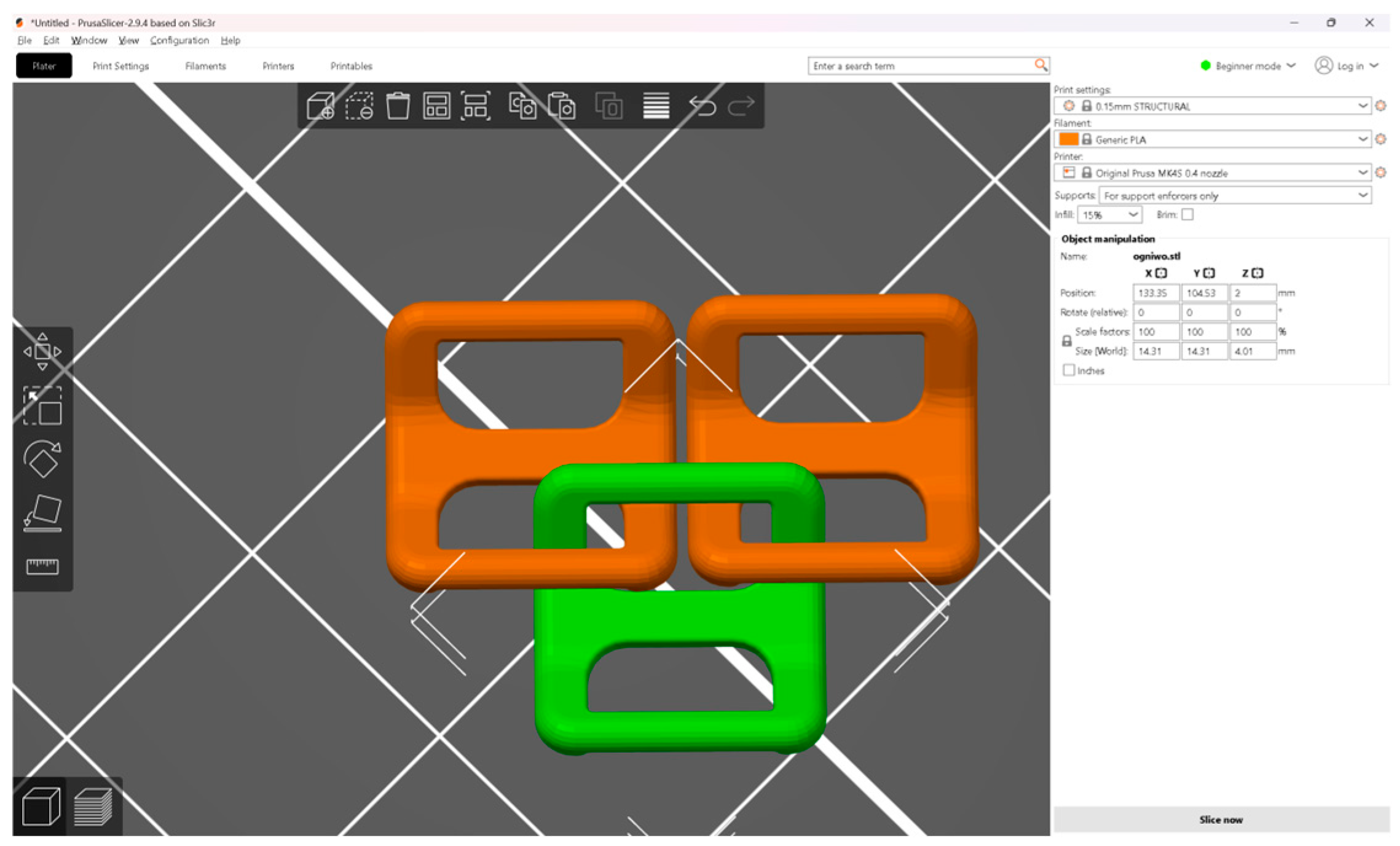

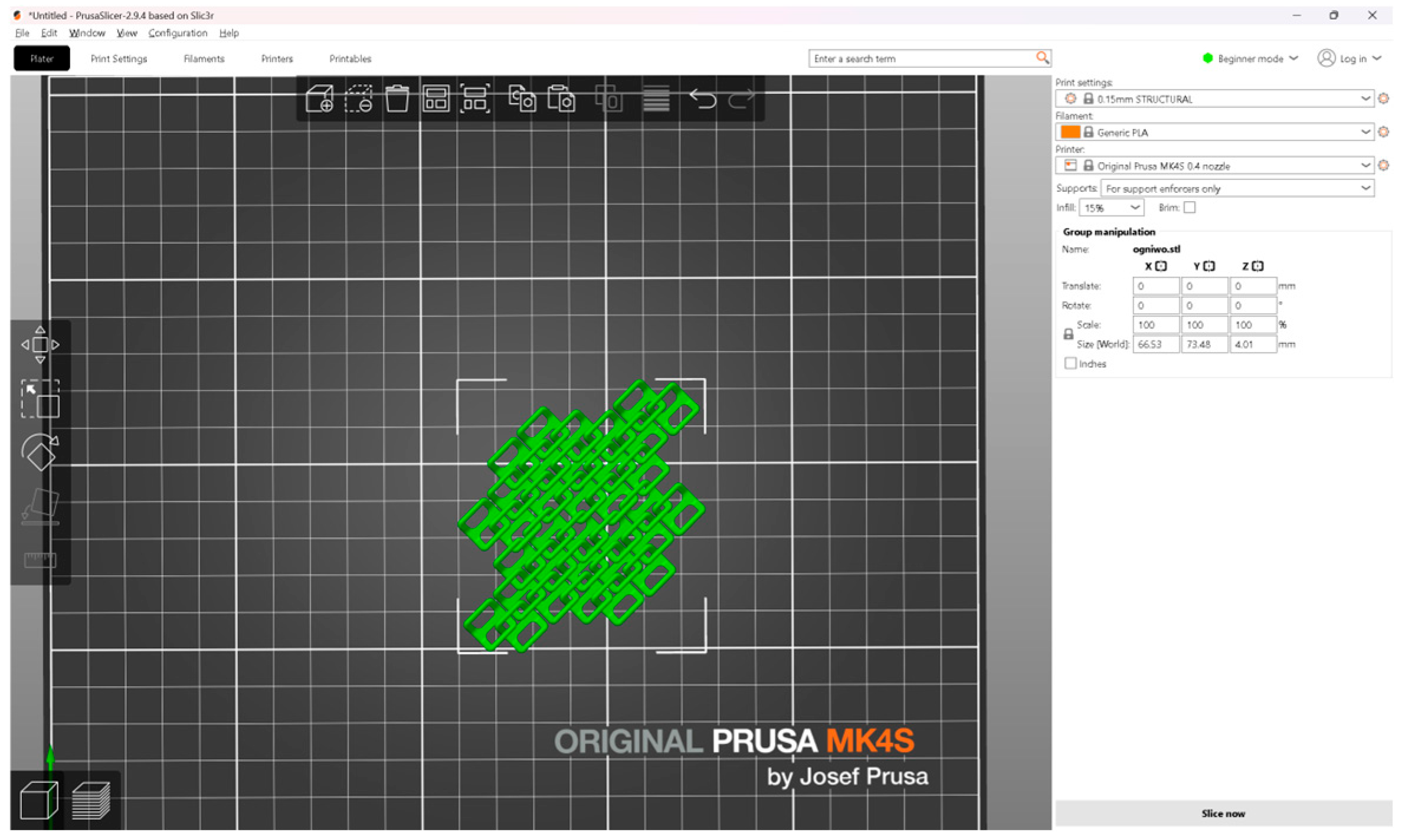

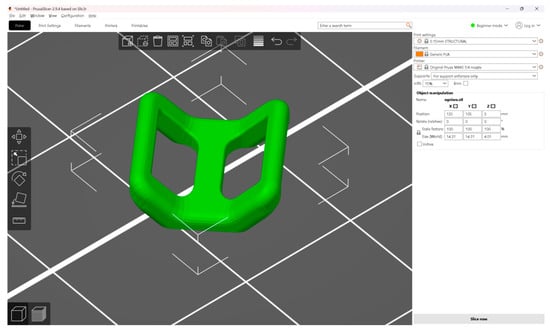

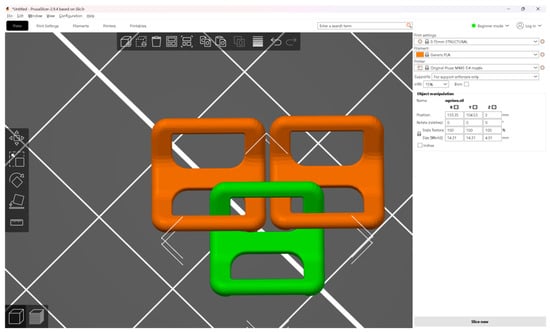

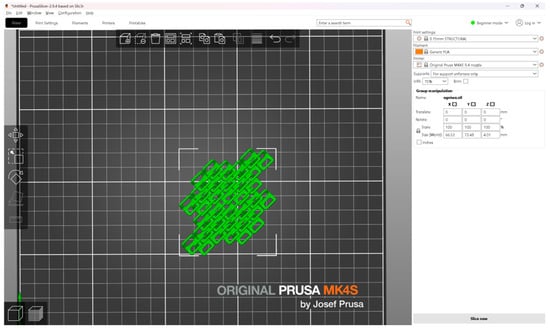

Key areas of technological optimization for 3D-printed hand exoskeletons within the Industry 4.0, 5.0, and 6.0 paradigms focus on connectivity, intelligence, and personalized functionality. One key area is the integration of advanced cyber–physical systems that synchronize user movement with actuator response in real-time [38]. High-resolution DTs are another key area, enabling continuous simulation, predictive maintenance, and iterative design improvements [39]. Embedded sensor networks require optimization to ensure accurate monitoring of force, motion, and physiological parameters without increasing bulk and discomfort [40]. AI-based control algorithms enhance responsiveness by learning user behaviors and dynamically adjusting assistance levels [41]. Human-centric Industry 5.0 principles drive the use of intuitive interfaces, voice or gesture control, and ergonomic adjustments tailored to individual needs [42]. Cloud-connected platforms support remote diagnostics, parameter tuning, and rehabilitation tracking [43]. Manufacturing optimization involves streamlining multi-material additive manufacturing processes for the reliable and scalable production of complex geometries [44]. Sustainability-based technological solutions focus on energy-efficient motors, modular architecture, and repairable components [45]. In the context of Industry 6.0, ultra-intelligent systems and quantum-enhanced optimization can dramatically accelerate the development of more efficient, adaptive, and personalized exoskeleton technologies such as chainmail supporting directional properties of 3D-printed elements (Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11).

Figure 9.

3D-printed single chainmail element creation as a part of hand exoskeleton with directional properties.

Figure 10.

3D-printed chainmail creation as a part of hand exoskeleton with directional properties: several elements combined into chainmail.

Figure 11.

3D-printed chainmail creation as a part of hand exoskeleton with directional properties: elements combined together within the chainmail.

3.3. Key Areas of Clinical Optimization

Key areas of clinical optimization of 3D-printed hand exoskeletons within the Industry 4.0, 5.0, and 6.0 paradigms focus on personalized rehabilitation, safety, and evidence-based integration with healthcare. A key focus is the development of clinically validated evaluation protocols that ensure the exoskeleton supports fine motor recovery and functional outcomes in diverse patient populations [46]. DT technology allows clinicians to simulate patient-specific biomechanics and adjust therapy parameters before prescribing the device [47]. Continuous sensor monitoring allows for real-time tracking of muscle activity, joint angles, and therapy progress, improving clinical decision-making [48]. AI-assisted rehabilitation programs can automatically adjust exercise intensity based on patient fatigue and recovery patterns. The human-centered principles of Industry 5.0 require exoskeleton designs that prioritize patient comfort, emotional acceptance, and cognitive accessibility during clinical use [49]. Clinically optimized workflows must also consider ease of adjustment, calibration, and daily operation for both patients and healthcare providers [50]. Long-term clinical trials are needed to determine durability, therapeutic efficacy, and safety across different age groups and conditions. Integrating remote care supports telerehabilitation models, allowing clinicians to tailor treatment plans for patients who cannot attend frequent clinic visits [51]. Future Industry 6.0 innovations (intelligent clinical decision-making systems) could significantly improve precise rehabilitation and patient-specific therapy modeling.

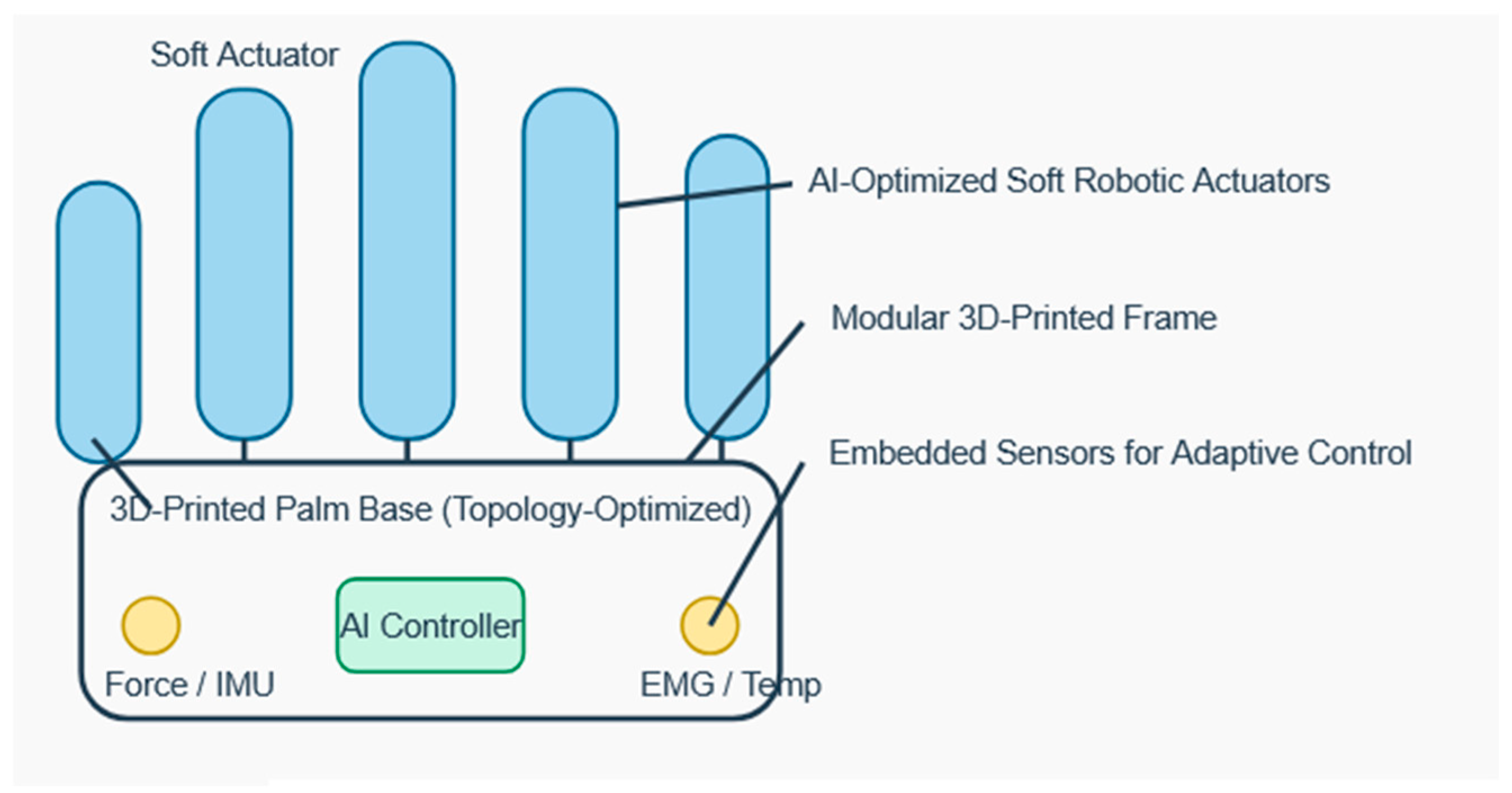

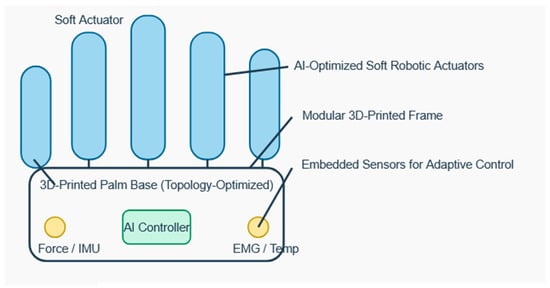

Key innovations within AI-optimized structure (Figure 12) include:

Figure 12.

Recent state-of-the-art innovations in a 3D-printed hand exoskeleton.

- The 3D-printed main frame utilizes AI-based topology optimization for maximum strength while minimizing weight;

- Soft actuators: each finger utilizes AI-designed soft actuators (e.g., TPU/hydrogel hybrids) that mimic natural flexion and reduce user fatigue;

- Built-in smart sensors: integrated IMU microsensors, force sensors, and temperature sensors transmit data to the AI control unit, providing adaptive assistance and real-time gait learning;

- Modular architecture: modular actuators and sensors enable easy upgrades and configurations tailored to various therapeutic goals;

- Comfort Interfaces: soft inserts (e.g., polysaccharide-based gels) improve comfort and reduce skin irritation.

3.4. Key Role of High-Resolution DTs in Improving Hand Exoskeletons

The key role of high-resolution DTs in improving 3D-printed hand exoskeletons in the Industry 4.0/5.0/6.0 paradigms is primarily their ability to precisely reproduce the user’s anatomy and biomechanics. High-resolution models allow for the simulation of microscale interactions between soft tissues and the exoskeleton structure, significantly increasing design accuracy [52]. Digital twins enable real-time analysis of force, friction, and stress distribution, supporting material optimization of individual components. They also facilitate testing of multiple geometric variants without the need for physical prototyping, accelerating design iterations [53]. In the Industry 5.0 framework, high-resolution digital twins support personalization by taking into account individual motor limitations, age, neurodegenerative diseases, and user ergonomics. Through integration with exoskeleton sensors, the digital twin can reflect the user’s actual behavior, enabling dynamic adjustment of support [54]. In the field of rehabilitation, digital twins support therapy planning by analyzing movement progression and adjusting device operating parameters. These models also play an important role in ensuring safety by detecting potential overloads or abnormal movement patterns [55]. From an Industry 6.0 perspective, future digital twins could use quantum computing for ultrafast prediction of new material configurations and microstructures. In this way, high-resolution digital twins become the foundation for intelligent, adaptive, and fully personalized hand exoskeletons.

3.5. Personal Experience

In AI-supported 3D printing, increasing emphasis is placed on structured data and design repositories, thorough data auditing for AI reuse, robust cybersecurity, and large-scale data analysis from IoT systems within Industry 4.0 and eHealth frameworks. These aspects should be incorporated into the figure alongside the iterative evaluation of successive exoskeleton generations. The development workflow includes biomechanical and technical assessment, identification of manufacturing constraints, retrofit planning, material and process optimization, and integration of test prints into functional prototypes. This cycle is completed through sensor-based motion analysis, mechanical and laboratory testing, additional simulations and experiments, iterative design refinement, and improved patient-specific fitting. The digital twin of an exoskeleton is a core element of the Industry 4.0 framework, enabling sustainable production and maintenance through continuous process monitoring, data-driven knowledge generation, and simulation-based improvement. By combining real experimental data, deep learning analysis, and scalable 3D-printed fabric designs, personalized chainmail structures with adjustable mechanical properties can be created to better support patient-specific therapeutic goals. In addition, AI-based software and remote monitoring systems enable contamination assessment and early detection of motor decline, supporting timely exoskeleton adjustments and improved clinical outcomes. Several factors must be considered in exoskeleton testing and control systems, including symmetric and asymmetric geometries, the biomechanics of the human hand, multiple feedback sources, and activities characterized by torque, position, trajectory, and motion laws, all of which are essential for detecting, interpreting, and supporting human movement intentions through feedforward control. This multimodal sensor data is processed by a classifier—commonly a k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) algorithm—and calibrated against an EMG-based unimodal classifier, achieving high prediction accuracy even with a small number of sEMG electrodes and without requiring precise electrode placement [56].

The human hand is an exceptionally precise and versatile instrument, and impairments to its function significantly reduce independence and quality of life. To address these challenges, researchers and clinicians are exploring advanced diagnostic, therapeutic, and rehabilitative solutions, including the development of hand exoskeletons. Effective exoskeleton design requires a strong focus on comfort, usability, and personalization, making proper fitting, testing, and user-specific adaptation essential. This study presents approaches to personalizing 3D-printed medical devices based on practical experience with user assessment, AI-supported material and design optimization, multi-generation exoskeleton development, and compliance with medical device standards, while outlining future directions of scientific and clinical relevance. The demanding and often conflicting requirements of hand exoskeletons frequently necessitate unconventional approaches, such as modifying 3D printers to fabricate novel materials with tailored properties. The significance of this challenge is highlighted by a soft hand exoskeleton developed for astronauts, which uses shape memory alloy actuators to reduce fatigue in pressurized EVA gloves while delivering high force in a compact design. Achieving high efficiency in such systems depends on optimizing material characteristics and technological parameters—a task well suited to artificial intelligence-based optimization of the 3D-printing process that balances performance and user safety. Existing research indicates that beyond basic functionality, factors such as mechanical simplicity, adaptability in design, and accommodation of different hand sizes are critical for successful hand exoskeleton development [57].

Based on the anatomical structure of the human hand, we designed an adjustable hand exoskeleton actuated by both pneumatic artificial muscles and tendon-driven mechanisms to support flexion and extension across all degrees of freedom. A distinctive aspect of the system is the 3D-printed artificial muscle integrated into the rehabilitation glove, which features a uniform, monolithic design. The glove consists of flexible polymer-based artificial muscles attached to individual fingers, ensuring a close fit, gentle stretching of the phalanges, stable hand positioning, and prevention of contractures. By combining cable-based and pneumatic actuation, this design achieves improved motion control and more accurate simulation of therapeutic rehabilitation movements [58].

The next two studies [59,60] aimed to develop an efficient automated or semi-automated method for designing 3D-printed exoskeleton chainmail with predefined, direction-dependent stiffness and flexibility tailored to individual user impairments. This approach is demonstrated through a hand exoskeleton in which single-layer 3D-printed chainmail structures provide adjustable one- or two-directional bending properties. The novelty of these studies lies in integrating real experimental data from hand exoskeleton research with deep neural network analysis and a scalable, customizable fabric design that can be personalized to therapeutic goals. This unique methodology, not previously reported in the literature, enables broader application of machine-learning-driven adaptive chainmail structures for increasingly complex exoskeleton designs [59,60].

Conventional rehabilitation technologies are progressing toward more advanced systems that improve therapeutic exercises and patient outcomes. The presented elbow exoskeleton enables reliable assessment and robotic assistance of upper-limb joints, supporting daily activities and helping prevent the progression of neuromuscular disorders through early, proactive rehabilitation. Given the rapid increase in plastic costs and usage, optimizing 3D-printing processes through AI-driven design and simulation can significantly reduce material consumption, waste, and environmental impact. Such optimization lowers time and production costs without compromising quality, offering a competitive advantage and enabling substantial material savings equivalent to one free print for every 6.67 produced [61].

Although patient-specific 3D-printed solutions can enhance the intensity and precision of robotic rehabilitation, their effectiveness may be reduced due to suboptimal material choices and printing parameters. This study focused on computational optimization of the 3D printing process and selection of materials to maximize the tensile strength of the hand exoskeleton component using artificial neural networks combined with genetic algorithms. Ten process and material parameters for PLA and PLA+ were analyzed in MATLAB 2021b (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA), with printed samples produced via fused filament fabrication and mechanically tested using a universal testing machine. The results identified PLA+ as the optimal material, highlighting the potential of AI-driven optimization to improve performance, safety, and reliability in customized exoskeleton components [62].

Soft–rigid interfaces play a critical role in exoskeleton design by balancing user comfort with the structural support required for effective assistance. Our experience shows that combining Bioflex with rigid filaments enhances mechanical performance while preserving adaptability to complex hand movements, though careful placement is necessary to avoid restricting natural motion. A major challenge lies in creating smooth, durable transitions between materials to prevent stress concentrations, fatigue, and early failure, which requires reliable bonding, mechanical locking, and geometric optimization. Therefore, this study focuses on investigating and optimizing the transition between soft and rigid materials to improve the durability, comfort, and functional performance of hand exoskeletons [63].

Support for the decision-making process in the production of 3D-printed hand exoskeletons within Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0 introduces innovative manufacturing approaches for medical devices intended for clinical use. Although many studies on hand exoskeletons have been published, a large proportion of these systems have not yet progressed to large-scale production or clinical implementation. Existing research demonstrates that hand exoskeletons provide significant therapeutic benefits, improving motor control while also promoting patient independence and reducing secondary motor impairments [64].

The authors’ own AI-based optimization of the 3D printing process, considering the characteristics and material selection to achieve maximum tensile force for the hand exoskeleton element, was conducted based on artificial neural network optimization supported by genetic algorithms in the MATLAB environment. The selected element was 3D-printed using fused filament fabrication technology. Ten selected parameters of two different printing materials (PLA, PLA+) were compared [62]. Improved AI-driven design reduces filament consumption, saves material, and reduces waste and environmental impacts. Saving time and money can provide a competitive advantage, especially for thin, mass-produced products.AI-driven optimization allows for one free print for every 6.67 prints (i.e., from previously wasted materials) [65]. A comparison of the optimization of 3D printing properties for the maximum tensile force of an exoskeleton sample based on traditional artificial neural networks and deep learning showed that the latter optimization method reduced the calculation speed by up to 1.5 times while maintaining the same print quality, improved quality, reduced MSE, and identified a set of printing parameters that had not been previously determined using other methods [66]. Automated, efficient, and practical chainmail design of 3D-printed exoskeletons with pre-programmed properties (including variable stiffness/flexibility depending on direction) allows for adaptive and optimized wrist exoskeleton design to individual user needs, including various types and degrees of impairment. 3D-printed chainmail components can be arranged into a single-layer structure with adjustable unidirectional or bidirectional bending modulus based on real-world user data, new methods for analyzing data using deep neural networks, and scalable, customizable 3D-printed fabric product design [59,60]. Further research shows that the main areas of AI-based optimization for wrist exoskeletons are:

- Personalized selection and optimization of exoskeleton materials (weight, mechanical, and chemical properties);

- Individual functional assessment, including the selection of an exoskeleton model/settings based on the type and level of a specific user’s deficit(s);

- User-specific exoskeleton design based on a template;

- 3D printing optimized with AI for material consumption and waste (preferring green technologies);

- Individual settings of the exoskeleton control system;

- Data collection, testing, and adjustment of the exoskeleton [67,68].

4. Discussion

This article addresses significant research gaps in the material, technological, and human-centric optimization of 3D-printed hand exoskeletons within the emerging concepts of Industry 4.0, 5.0, and 6.0. It highlights persistent limitations in understanding how smart materials behave under prolonged, cyclic biomechanical loading typical of everyday hand use. Current DT models are considered insufficiently accurate to capture the complex interactions between soft tissues, actuators, and additively manufactured components. Challenges associated with multi-material 3D printing, sensor integration, and data standardization continue to hinder the optimization of flexibility, durability, and real-time monitoring. The article highlights the difficulties in translating personalized ergonomic and neurological data into manufacturable designs, which limits effective human-centric personalization. Sustainability issues remain underexplored, particularly with regard to recyclable and medical materials suitable for additive manufacturing. AI-based design optimization is limited by the lack of large, high-quality datasets, which reduces the reliability of automated design recommendations. To address these challenges, this study proposes innovations such as adaptive multi-material printing, embedded self-calibrating sensors, advanced DTs, and AI-based generative design systems. It also highlights the importance of interdisciplinary collaborations integrating materials science, biomechanics, smart manufacturing, and user-centered design to improve device performance and usability. Combining technological innovations with human-centered principles could revolutionize the development of affordable, lightweight, sustainable, and highly personalized hand exoskeletons for rehabilitation and assistive care.

This article presents an innovative approach to the design and optimization of a 3D-printed hand exoskeleton as an adaptive, human-centric system rather than a purely mechanical assistive device. This directly reflects the core philosophy of Industry 5.0 and prefigures Industry 6.0. Structurally, Industry 5.0 is realized through the integration of expertise, personalized biomechanics, and sustainable material selection, positioning the user as an active co-designer in the optimization loop. Conceptually, Industry 6.0 is introduced by extending this framework toward cognitive automation, where systems continuously learn from user interactions and physiological feedback to autonomously evolve over time. At the theoretical level, AI is used as a decision-support and optimization layer, enabling adaptive material selection, geometric refinement, and control strategy tuning based on multi-criteria performance criteria. DTs are used not only for simulation but also as living virtual counterparts that mirror the behaviors of the physical exoskeleton, enabling predictive performance assessment and rapid pre-production iteration. This study introduces a novel combination of AI-based optimization with digital twin feedback loops to achieve real-time customization of exoskeleton structure and function. A significant contribution is demonstrating how the constraints of additive manufacturing and the behavior of smart materials can be co-optimized within this cyber–physical framework. This study advances this field by presenting a future methodological roadmap in which future hand exoskeletons evolve as intelligent, human-adapted systems rather than static assistive products.

The small number of studies and publications to date on the material and technological optimization of exoskeletons, including hand exoskeletons, indicates the need to intensify research in this area, especially with the use of AI. However, it is important to consider a number of factors, such as the energy and environmental costs of 3D printing. The key implications of this group of technologies will be discussed later in this article.

The current state of AI-based optimization development in hand exoskeleton modeling is characterized by a dynamic increase in interest and interdisciplinary applications combining robotics, biomechanics, and machine learning. AI is increasingly being used to automatically adapt exoskeleton design parameters to the user’s individual anatomical and functional characteristics, significantly improving comfort and device efficiency. Deep learning algorithms analyze EMG and movement signals in real-time, enabling more precise control of assistance based on the user’s intentions. AI-assisted topological optimization allows for the design of structures with optimal stiffness and mass, which can then be printed using advanced additive technologies. DTs, powered by AI predictive models, enable simulations of exoskeletons’ behavior in various use scenarios without the need for costly physical prototypes. Multi-criteria methods with ML enable simultaneous optimization of user comfort, energy efficiency, and safety. AI also supports adaptive control strategies that can adjust parameters in real-time in response to changing user needs and the environment. Reinforcement learning techniques are gaining importance for learning optimal movement sequences and providing assistance based on user interactions. Applying AI to the analysis of large experimental datasets is helping to identify new ergonomic and mechanical patterns that were previously difficult to capture. Despite significant progress, challenges remain in integrating AI with physical prototypes, ensuring system safety and predictability, and validating them across diverse user populations.

Industry 6.0 plays a future-proof role in the development of hand exoskeletons, moving beyond automation and human–machine collaboration toward cognitive, self-evolving, and ethically compliant systems. In this paradigm, hand exoskeletons are viewed as intelligent companions that continuously learn from the user’s biomechanical, neurological, and behavioral data to optimize assistance at an individual level. AI in Industry 6.0 enables lifelong learning models that adapt not only to the user’s short-term intentions but also to long-term changes such as rehabilitation progress, fatigue, or disease progression. DTs become autonomous, constantly synchronized entities that predict future performance, failure modes, and user needs, enabling proactive design updates and maintenance. Industry 6.0 also emphasizes neurosymbolic AI and XAI, which are crucial for ensuring safety, transparency, and clinical trust in wearable robotic systems. Advanced materials and 4D/5D printing, guided by design AI, allow exoskeletons to self-adjust their stiffness, geometry, and actuation properties over time. Human values, ethics, and well-being are directly embedded in the design logic, ensuring technological advancements serve rehabilitation, inclusiveness, and quality of life, not just performance metrics. Industry 6.0 is transforming hand exoskeletons from adaptive devices into predictive, self-optimizing, and human-adaptive cyber–physical systems that evolve with their users.

4.1. Limitations of Current Research

Existing studies on the material and technological optimization of 3D-printed hand exoskeletons remain limited by fragmented collaboration between materials scientists, clinicians, and manufacturing engineers. Interdisciplinary research teams are lacking. Many studies rely on small, unrepresentative test groups, making it difficult to generalize their results to diverse users with diverse biomechanical needs [69]. Multi-material printing, while promising, is characterized by inconsistent quality and, in practice, often requires extensive trial and error to obtain reliable stiffness gradients. DT simulations tend to oversimplify the behaviors of human tissues, leading to a discrepancy between virtual performance and real-world prototype testing [70]. Sensor embedding is another area where practical integration challenges (cable routing, durability, and signal noise) are often underexplored and underreported in the scientific literature. Despite Industry 5.0’s emphasis on human-centered design, many designs still prioritize mechanical optimization, placing significantly less emphasis on user comfort, emotional acceptance, and intuitive interaction (key to the Industry 5.0 paradigm) [71]. Sustainability discussions often remain theoretical, with few studies demonstrating concrete methods for recycling or reprinting used components. AI-based optimization tools are developing, but researchers often lack the extensive, high-quality datasets needed to effectively train them. Early Industry 6.0 concepts, such as quantum simulation, are emerging in discussions but offer little practical guidance for current design processes. The gap between theoretical promises and practical, ready-to-use solutions remains a persistent limitation in the field [72].

4.2. Technological Implications

The material and technological optimization of 3D-printed hand exoskeletons has significant technological implications for Industry 4.0, 5.0, and 6.0. It is expected to accelerates the integration of cyber–physical systems, enabling real-time synchronization between user movement, embedded sensors, and adaptive control algorithms. Advanced multi-material printing is introducing new manufacturing processes that enable the fabrication of complex, biomimetic structures in a single, automated process [73]. The use of DTs improves predictive maintenance and iterative design, allowing engineers to simulate wear, stress, and user interactions before production. Continuous data collection from intelligent sensors enhances closed-loop feedback systems, improving both performance and long-term reliability. Human-centric technology from Industry 5.0 is driving the development of customizable interfaces, ensuring that exoskeletons intuitively adapt to individual ergonomic and neurological conditions. Sustainable materials and energy-efficient manufacturing methods are transforming supply chains toward circular production models. AI-powered optimization tools are shortening development time by automating geometric refinement and performance prediction. As Industry 6.0 advances, quantum-accelerated simulations and ultra-intelligent systems can dramatically shorten the process of discovering new materials and structural configurations. These implications signal a shift toward autonomous, personalized, and environmentally friendly enabling technology ecosystems [74].

An integrated materials design strategy combining nature-inspired 3D-printed gradient materials with advanced post-processing will provide solutions that meet the specific requirements of various industries. This opens up new possibilities for next-generation structural materials with programmable ductility and damage resistance. It also enables better adaptation of biologically inspired solutions (including the biomechanics of the human hand) to practical engineering solutions (e.g., hand exoskeletons) [75].

4.3. Economic Implications

Material and technological optimization of 3D-printed hand exoskeletons introduces a number of significant economic implications within the Industry 4.0, 5.0, and 6.0 paradigms. Additive manufacturing lowers production costs by minimizing material waste and enabling on-demand production instead of mass production. Integrating DTs and AI-based optimization shortens development cycles, reducing research and prototyping costs for manufacturers. Customizable exoskeleton designs create new market opportunities in rehabilitation and physiotherapy, work assistance, and personalized healthcare (including home healthcare, which is crucial in aging societies in developed countries). Embedded sensor systems and predictive analytics can extend device lifespans, reducing maintenance costs for both clinics and individual users. Human-centered Industry 5.0 principles support the development of high-quality, personalized products, potentially increasing economic value through higher user satisfaction and adoption rates. Sustainable materials and circular manufacturing strategies help companies to reduce costs associated with disposal, logistics, and environmental compliance. Interdisciplinary digital collaboration platforms reduce coordination costs between design, engineering, and clinical teams. As Industry 6.0 technologies evolve, quantum-enhanced materials discovery and autonomous optimization can lower long-term R&D costs and accelerate market competitiveness. These advances are driving the transformation toward scalable, efficient, and personalized economies based on enabling technologies [76].

4.4. Societal Implications

The material and technological optimization of a 3D-printed hand exoskeleton has far-reaching societal implications across Industry 4.0, 5.0, and 6.0, particularly in aging societies. It increases the independence of older adults by supporting daily activities such as grasping, lifting, and manipulating objects despite age-related muscle weakness. The availability of personalized, lightweight exoskeletons can reduce the burden on caregivers, allowing medical staff and family members to focus on higher-level support. Improved rehabilitation devices accelerate recovery from stroke or age-related injuries, contributing to increased life quality and lowering the costs of long-term care. Human-centered design, consistent with Industry 5.0, ensures that devices address not only the physical needs but also the comfort, dignity, and emotional well-being of older adults. As the population ages, scalable additive manufacturing enables universal access to assistive technologies without overloading healthcare infrastructure. Digital connectivity and sensor data support remote monitoring, allowing clinicians to track progress and intervene early without frequent hospital visits. A more inclusive design approach promotes social participation, helping older adults to remain active in their communities and workplaces. Sustainable material selection promotes responsible production and disposal as demand for assistive devices increases. These advances strengthen societal resilience by aligning technological innovations with human well-being, equity, and the challenges of aging in developed countries [77].

4.5. Ethical and Legal Implications

The material and technological optimization of a 3D-printed hand exoskeleton carries significant ethical and legal implications within the Industry 4.0, 5.0, and 6.0 paradigms, particularly in aging societies. Ensuring data privacy becomes crucial, as sensor-rich exoskeletons constantly collect biomechanical and health information from users. Questions about informed consent arise, especially when older adults with cognitive impairments may struggle to fully understand how their data is used and shared. Legal frameworks must clearly define liability in cases where device failure, software errors, or AI-driven decisions result in user injury. Ethical concerns regarding equal access also arise, as personalized exoskeletons can become expensive and widen the gap between affluent and disadvantaged older adults. Transparent algorithms are needed to prevent bias in AI-based optimization systems that could inadvertently favor certain groups of users over others. Regulations must adapt to new materials and additive manufacturing processes to ensure the safety, biocompatibility, and long-term reliability of custom components. The human-centered principles of Industry 5.0 emphasize the moral responsibility of designing devices that enhance autonomy rather than creating dependency or limiting interpersonal interactions in care. Sustainability requirements introduce further legal considerations regarding responsible disposal, recycling, and sourcing of materials. These ethical and legal implications underscore the need for robust governance that protects older users while enabling innovation in assistive technologies [78].

4.6. Implications for Global Sustainability

The material and technological optimization of 3D-printed hand exoskeletons contributes to global sustainability by significantly reducing material waste through precise, digitally controlled additive manufacturing. The transition to Industry 4.0 practices enables more efficient energy use, as automated production systems minimize printing errors and lower overall resource consumption. From an environmental perspective, the ability to use lightweight, recyclable, or bio-based polymers reduces the ecological footprint of medical device production. Industry 5.0’s emphasis on human–machine collaboration further enhances sustainability by enabling device customization to individual anatomical needs, preventing overproduction and unnecessary material waste. From an energy perspective, optimized designs created with generative AI-based tools minimize weight, resulting in lower energy requirements during both production and operation. The use of digital twins within Industry 6.0 supports continuous monitoring and optimization, enabling long-term reductions in energy consumption throughout the product lifecycle. Environmentally responsible design also reduces transportation-related emissions, as local additive manufacturing shortens supply chains. From a health perspective, improved ergonomics and exoskeleton personalization support more effective rehabilitation, reducing the need for long-term medical interventions and the associated resource demands. Increased device durability, achieved through intelligent material selection, extends its lifespan and reduces waste resulting from premature replacement. This integrated approach demonstrates how advanced industrial paradigms can simultaneously support environmental protection, energy efficiency, and improved global health outcomes.

4.7. Directions for Further Research

Further research into the material and technological optimization of 3D-printed hand exoskeletons should prioritize the development of advanced multi-material printing methods, enabling the fabrication of lightweight and durable structures tailored to the needs of older users. Efforts are needed to create high-fidelity DTs that precisely simulate age-related biomechanical changes, enabling more precise personalization. Researchers should investigate the long-term performance of smart materials under repetitive loads typical of aging individuals with weakened muscle strength. Research must also be conducted with the aim of improving the seamless integration of sensors for continuous monitoring while ensuring data privacy and ease of use for seniors. Human-centered design frameworks should consider the physical, cognitive, and emotional aspects of older adults to increase their acceptance and usability. Sustainable materials development should focus on biocompatible, recyclable polymers that support large-scale implementation in aging societies characterized by a growing demand for medical devices. AI-based optimization models require larger and more diverse datasets that reflect the variability observed in older populations. Remote connectivity capabilities must be enhanced to allow clinicians to adjust device parameters without requiring frequent clinic visits. Legal and ethical research is needed to establish standards for safety, liability, and data management in personalized exoskeleton systems. Interdisciplinary collaboration will be essential to ensure that future exoskeleton technologies are compatible with the health, dignity, and independence of older adults in developed countries [79].

5. Conclusions

The development of 3D-printed hand exoskeletons demonstrates how advances in industrial design can significantly transform medical device engineering. Leveraging Industry 4.0 tools and principles, the project achieved greater precision, material efficiency, and design flexibility than would be possible using conventional methods. The transition to Industry 5.0 further emphasized the importance of human-centered design, ensuring that technological innovations align with ergonomics, comfort, and personalized rehabilitation needs. Meanwhile, integrating new Industry 6.0 concepts such as generative design and digital twins is expected to provide a clear path toward systems which are capable of autonomous adaptation and continuous optimization. Personal experiences with material selection, printing constraints, and device load-bearing capacity have highlighted the practical challenges that remain after moving from digital models to functional prototypes. Nevertheless, iterative refinement supported by smart manufacturing technologies has proven essential for improving performance while simultaneously reducing production time and resource consumption. Existing research and publications confirm that additive manufacturing, combined with increasingly intelligent industrial ecosystems, can significantly accelerate the personalization and availability of assistive devices. This demonstrates how the combination of technology and human-centered innovation can drive the development of the next generation of efficient, adaptive, and user-centric rehabilitation solutions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16031538/s1: Partial PRISMA 2020 Checklist [80].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.R., J.K., A.O. and D.M.; software, I.R., J.K., A.O. and D.M.; validation, I.R., J.K., A.O. and D.M.; formal analysis, I.R., J.K., A.O. and D.M.; investigation, I.R., J.K., A.O. and D.M.; resources, I.R., J.K., A.O. and D.M.; data curation, I.R., J.K., A.O. and D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.R., J.K., A.O. and D.M.; writing—review and editing, I.R., J.K., A.O. and D.M.; visualization, J.K. and D.M.; supervision, I.R.; project administration, I.R.; funding acquisition, I.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work presented in the paper has been financed under a grant to maintain the research potential of Kazimierz Wielki University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| DT | Digital twin |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| EVA | Ethylene vinyl acetate |

| genAI | Generative AI |

| IoT | Internet of things |

| kNN | k-nearest neighbors |

| ML | Machine learning |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

| PLA | Polylacticacid |

| PlA+ | PLA Plus, enhanced version of PLA |

| R&D | Research and development |

| SDG | Sustainable development goal |

References

- Fernandes da Silva, J.L.G.; Barroso Gonçalves, S.M.; Plácido da Silva, H.H.; Tavares da Silva, M.P. Three-dimensional printed exoskeletons and orthoses for the upper limb—Asystematic review. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2024, 8, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łukaniszyn, M.; Majka, Ł.; Grochowicz, B.; Mikołajewski, D.; Kawala-Sterniuk, A. Digital Twins Generated by Artificial Intelligence in Personalized Healthcare. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopura, R.A.R.C.; Kiguchi, K. Mechanical Designs of Active Upper-Limb Exoskeleton Robots: State-of-the-Art and Design Difficulties. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics, Kyoto, Japan, 23–26 June 2009; pp. 178–187. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Xie, H.; Li, W.; Yao, Z. Proceeding of Human Exoskeleton Technology and Discussions on Future Research. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2014, 27, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, I.; Kotlarz, P.; Dorożyński, J.; Mikołajewski, D. Sixth-Generation (6G) Networks for Improved Machine-to-Machine (M2M) Communication in Industry 4.0. Electronics 2024, 13, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Grove, K.; Wei, A.; Lee, J.; Akkouch, A. Ankle and Foot Arthroplasty and Prosthesis: A Review on the Current and Upcoming State of Designs and Manufacturing. Micromachines 2023, 14, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preethichandra, D.M.G.; Piyathilaka, L.; Sul, J.H.; Izhar, U.; Samarasinghe, R.; Arachchige, S.D.; de Silva, L.C. Passive and Active Exoskeleton Solutions: Sensors, Actuators, Applications, and Recent Trends. Sensors 2024, 24, 7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Halkiopoulos, C. Digital Twin Cognition: AI-Biomarker Integration in Biomimetic Neuropsychology. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, M.E.; Sauer, A.; Isaacs, C.; Ganga, T.A.F.; Fazan, L.H.; Keller Rorato, E. Teaching Bioinspired Design for Assistive Technologies Using Additive Manufacturing: A Collaborative Experience. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos Dias, W.; Soares, J.H.; Corrêa Guimarães, L.; Espinosa Martínez, N.; Ramos Luz, T.; da Costa Soares Sousa Lima, Y.M.; Huebner, R. Exploring Additive Manufacturing in Assistive Technologies to Transform the Educational Experience: Empowering Inclusion. J. Complex. Health Sci. 2024, 7, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, S.; Lago, F.; Lavia, G.; Macrì, F.P.; Sgamba, F.; Tozzo, A.; Adamo, D.; Avila, J.M.N.; Carbone, G. Design and Experimental Validation of a Unidirectional Cable-Driven Exoskeleton for Upper Limb Rehabilitation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, T.; Krause, M.; Ramlawi, A.; Lagos-Antonakos, J.; Catterlin, J.K.; Kartalov, E.P. Advanced Architectures of Microfluidic Microcapacitor Arrays for 3D-Printable Biomimetic Electrostatic Artificial Muscles. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, G.; Daly, L.; Jovanovic, V.; Cuckov, F. A Low-Cost Soft Robotic Hand Exoskeleton for Use in Therapy of Limited Hand–Motor Function. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalıkuşu, İ.; Fidan, U. The impact of different material types on ergonomics in lower extremity exoskeleton construction. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 193, 110403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Feng, B.; Emmanuel Yeboah, K.; Feng, J.; Jumani, M.S.; Ali, S.A. Leveraging Industry 4.0 for marketing strategies in the medical device industry of emerging economies. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdaus, M.M.; Dam, T.; Anavatti, S.; Das, S. Digital technologies for a net-zero energy future: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaway, I.; Jallouli-Khlif, R.; Maalej, B.; Derbel, N. A Robust Fuzzy Fractional Order PID Design Based On Multi-Objective Optimization for Rehabilitation Device Control. J. Robot. Control (JRC) 2023, 4, 388–402. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Jin, Y.; Hou, X.; Huang, Z.; Hu, J.; Yu, H.; He, Z. Mapping the Evolution of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Materials. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 43077–43088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, N.T.; Rashid, A.B.; Hoque, M.E. Artificial intelligence in additive manufacturing for biomedical engineering. In 3D Printing for Biomedical Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2026; pp. 561–594. [Google Scholar]

- Jenks, B.; Levan, H.; Stefanovic, F. Open SEA: A 3D printed planetary gear series elastic actuator for a compliant elbow joint exoskeleton. Front. Robot. AI 2025, 12, 1528266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, H.; Jangde, R.K. Biomedical Application of 3D Printing. In 3D Printing and Microfluidics in Dermatology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 56–80. [Google Scholar]

- Łapczyńska, D. Fuzzy FMEA in risk assessment of human-factor in production process. In International Conference on Intelligent Systems in Production Engineering and Maintenance; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 677–689. [Google Scholar]

- Bochnia, J.; Kozior, T.; Hajnys, J. 3D Printing of Thin-Walled Models- State-of-Art. Mechanics 2024, 66, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- John, P.; Selvam, A.K.; Uppal, M.; Mohammed Adhil, S. Futuristic Biomaterials for 3D Printed Healthcare Devices. In Digital Design and Manufacturing of Medical Devices and Systems; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Grira, S.; Mozumder, M.S.; Mourad, A.H.I.; Ramadan, M.; Khalifeh, H.A.; Alkhedher, M. 3D bioprinting of natural materials and their AI-Enhanced printability: A review. Bioprinting 2025, 46, e00385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiałek, M. Comparative analysis of selected parameters of thin-walled samples produced using FFF/FDM 3D printing technology. Mechanik 2024, 98, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.; Hasan, S.; Mashud, G.A.; Bhujel, S. Neural Network for Enhancing Robot-Assisted Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Actuators 2025, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alli, Y.A.; Anuar, H.; Manshor, M.R.; Okafor, C.E.; Kamarulzaman, A.F.; Akçakale, N.; Nasir, N.A.M. Optimization of 4D/3D printing via machine learning: A systematic review. Hybrid. Adv. 2024, 6, 100242. [Google Scholar]

- Bănică, C.-F.; Sover, A.; Anghel, D.-C. Printing the Future Layer by Layer: A Comprehensive Exploration of Additive Manufacturing in the Era of Industry 4.0. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cano, A.; Mendoza-Báez, R.; Zenteno-Mateo, B.; Rodríguez-Mora, J.I.; Agustín-Serrano, R.; Morales, M.A. Study by DFT of the functionalization of amylose/amylopectin with glycerin monoacetate: Characterization by FTIR, electronic and adsorption properties. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1269, 133761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntean, E.; Leba, M.; Ionica, A.C. AI-Driven Arm Movement Estimation for Sustainable Wearable Systems in Industry 4.0. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashta, G.; Finco, S.; Battini, D.; Persona, A. Passive Exoskeletons to Enhance Workforce Sustainability: Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śpiewak, S.; Wojnicz, W.; Awrejcewicz, J.; Mazur, M.; Ludwicki, M.; Stańczyk, B.; Zagrodny, B. Modeling and Strength Calculations of Parts Made Using 3D Printing Technology and Mounted in a Custom-Made Lower Limb Exoskeleton. Materials 2024, 17, 3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Junior, A.; Theodosiou, A.; Díaz, C.; Marques, C.; Pontes, M.J.; Kalli, K.; Frizera-Neto, A. Fiber Bragg Gratings in CYTOP Fibers Embedded in a 3D-Printed Flexible Support for Assessment of Human–Robot Interaction Forces. Materials 2018, 11, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Misra, M.; Taylor, G.W.; Mohanty, A.K. A review of AI for optimization of 3D printing of sustainable polymers and composites. Compos. Part C Open Access 2024, 15, 100513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-la-Cruz-Diaz, M.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Jaramillo-Arévalo, M.; de las Mercedes Anderson-Seminario, M.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S. 3Dprint, circularity, and footprints. In Circular Economy: Impact on Carbon and Water Footprint; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Shinkawa, H.; Ishizawa, T. Artificial intelligence-based technology for enhancing the quality of simulation, navigation, and outcome prediction for hepatectomy. Artif. Intell. Surg. 2023, 3, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, H.; Yang, H.; Li, Z.; Dai, Y. Adaptive Admittance Control of Human–Space suit Interaction for Joint-Assisted Exoskeleton Robot in Active Space suit. Electronics 2025, 14, 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Liu, G.; Meng, Q.; Xu, X.; Qin, L.; Yu, H. Bionic Design of a Novel Portable Hand-Elbow Coordinate Exoskeleton for Activities of Daily Living. Electronics 2023, 12, 3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, S.-J.; Chu, H.-R.; Li, I.-H.; Lee, L.-W. A Novel Wearable Upper-Limb Rehabilitation Assistance Exoskeleton System Driven by Fluidic Muscle Actuators. Electronics 2023, 12, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Dong, W.; Lin, W.; He, L.; Wang, X.; Li, P.; Gao, Y. Human Joint Torque Estimation Based on Mechanomyography for Upper Extremity Exosuit. Electronics 2022, 11, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, M.S.b.; Babar Ali, C.; Kausar, Z.; Shah, S.Y.; Shah, S.A.; Ahmad, J.; Imran, M.A.; Abbasi, Q.H. Design of Portable Exoskeleton Forearm for Rehabilitation of Monoparesis Patients Using Tendon Flexion Sensing Mechanism for Health Care Applications. Electronics 2021, 10, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dai, Y.; Tang, P. Adaptive Neural Network Control with Fuzzy Compensation for Upper Limb Exoskeleton in Active Spacesuit. Electronics 2021, 10, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, R.; Ariyanto, M.; Perkasa, I.A.; Adirianto, R.; Putri, F.T.; Glowacz, A.; Caesarendra, W. Soft Elbow Exoskeleton for Upper Limb Assistance Incorporating Dual Motor-Tendon Actuator. Electronics 2019, 8, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyo, M.K.; Raza, Y.; Ahmed, S.F.; Billah, M.M.; Kadir, K.; Naidu, K.; Ali, A.; Mohd Yusof, Z. Optimized Proportional-Integral-Derivative Controller for Upper Limb Rehabilitation Robot. Electronics 2019, 8, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Yoon, J.; Lee, D.; Seong, D.; Lee, S.; Jang, M.; Choi, J.; Yu, K.J.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.; et al. Wireless Epidermal Electromyogram Sensing System. Electronics 2020, 9, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rudolph, A.; Wright, M.A.; Teixidó-Font, C.; Sanchez-Carrion, R.; Cedersund, G.; Opisso, E. Digital twins in stroke rehabilitation: A scoping review of objectives, data sources, mechanisms, outcomes, and desirable properties. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kooij, H.; van Asseldonk, E.H.F.; Sartori, M.; Basla, C.; Esser, A.; Riener, R. AI in therapeutic and assistive exoskeletons and exosuits: Influences on performance and autonomy. Sci. Robot. 2025, 10, eadt7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misir, A.; Yuce, A. AI in Orthopedic Research: A Comprehensive Review. J. Orthop. Res. 2025, 43, 1508–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkowski, P.; Osiak, T.; Wilk, J.; Prokopiuk, N.; Leczkowski, B.; Pilat, Z.; Rzymkowski, C. Study on the Applicability of Digital Twins for Home Remote Motor Rehabilitation. Sensors 2023, 23, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzolato, C.; Saxby, D.J.; Palipana, D.; Diamond, L.E.; Barrett, R.S.; Teng, Y.D.; Lloyd, D.G. Neuromusculoskeletal Modeling-Based Prostheses for Recovery After Spinal Cord Injury. Front. Neurorobot. 2019, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wu, Y.; Hu, M.; Chang, C.W.; Liu, R.; Qiu, R.; Yang, X. Current progress of digital twin construction using medical imaging. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2025, 26, e70226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.; Covino, R.; Hänelt, I.; Müller-McNicoll, M. Understanding the cell: Future views of structural biology. Cell 2024, 187, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillevin, R.; Naudin, M.; Fayolle, P.; Giraud, C.; Le Guillou, X.; Thomas, C.; Herpe, G.; Miranville, A.; Fernandez-Maloigne, C.; Pellerin, L.; et al. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Issues in Glioma Using Imaging Data: The Challenge of Numerical Twinning. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terranova, N.; Venkatakrishnan, K. Machine Learning in Modeling Disease Trajectory and Treatment Outcomes: An Emerging Enabler for Model-Informed Precision Medicine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 115, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zheng, L. Model-Based Comparison of Passive and Active Assistance Designs in an Occupational Upper Limb Exoskeleton for Overhead Lifting. IISE Trans. Occup. Ergon. Hum. Factors 2021, 9, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikołajewski, D.; Rojek, I.; Kotlarz, P.; Dorożyński, J.; Kopowski, J. Personalization of the 3D-Printed Upper Limb Exoskeleton Design—Mechanical and IT Aspects. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, I.; Kaczmarek, M.; Kotlarz, P.; Kempiński, M.; Mikołajewski, D.; Szczepański, Z.; Kopowski, J.; Nowak, J.; Macko, M.; Szczepańczyk, A.; et al. Hand Exoskeleton—Development of Own Concept. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, I.; Kopowski, J.; Kotlarz, P.; Dorożyński, J.; Dostatni, E.; Mikołajewski, D. Deep Learning in Design of Semi-Automated 3D Printed Chainmail with Pre-Programmed Directional Functions for Hand Exoskeleton. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopowski, J.; Mikołajewski, D.; Kotlarz, P.; Dostatni, E.; Rojek, I. A Semi-Automated 3D-Printed Chainmail Design Algorithm with Preprogrammed Directional Functions for Hand Exoskeleton. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, I.; Mikołajewski, D.; Kopowski, J.; Kotlarz, P.; Piechowiak, M.; Dostatni, E. Reducing Waste in 3D Printing Using a Neural Network Based on an Own Elbow Exoskeleton. Materials 2021, 14, 5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. 3D printing applications for healthcare research and development. Glob. Health J. 2022, 6, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, I.; Kopowski, J.; Andryszczyk, M.; Mikołajewski, D. From Shore-A85 to Shore-D70: Multimaterial Transitions in 3D-Printed Exoskeleton. Electronics 2025, 14, 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenjareghi, M.J.; Sekkay, F.; Dadouchi, C.; Keivanpour, S. Wearable sensors in Industry 4.0: Preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Sens. Int. 2026, 7, 100343. [Google Scholar]

- BG, P.K.; Mehrotra, S.; Marques, S.M.; Kumar, L.; Verma, R. 3D printing in personalized medicines: A focus on applications of the technology. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.L.; Goh, G.L.; Goh, G.D.; Ten, J.S.J.; Yeong, W.Y. Progress and opportunities for machine learning in materials and processes of additive manufacturing. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2310006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, L.; Aljabali, A.A.; Tambuwala, M.M. Empowering precision medicine: The impact of 3D printing on personalized therapeutic. AAPS Pharmscitech 2023, 24, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nain, G.; Samal, U. Concurrence of artificial intelligence and additive manufacturing: A bibliometric analysis. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2025, 36, 1405–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, G.; Wang, Q.; Ding, Y.; Wu, L.; Shi, H.; Sun, Z.; Ou, Z.; Miao, Y.; Ji, X.; et al. Applications of Robotic Exoskeletons as Motion-Assistive Systems in Cancer Rehabilitation. Research 2025, 8, 0855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin-Bédard, N.; Déry, J.; Simon, M.; Blanchette, A.K.; Bouyer, L.; Gagnon, M.; Routhier, F.; Lamontagne, M.E. Acceptability of rehabilitation exoskeletons of users with spinal cord injury and healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2025, 69, 102033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Ko, M.J.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, B.J.; Lee, S.; Kwon, W.K.; Kang, S.H. State-of-the-Art in Robotic Rehabilitation for Spinal Cord Injury Patients: A Literature Review. Korean J. Neurotrauma 2025, 21, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xie, Q. Applications of artificial intelligence in rehabilitation: Technological innovation and transformation of clinical practice. SLAS Technol. 2025, 35, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, J. Effectiveness of AI-assisted rehabilitation for musculoskeletal disorders: A network meta-analysis of pain, range of motion, and functional outcomes. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1660524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supriyono, C.S.A.; Dragusanu, M.; Malvezzi, M. A Comprehensive Review of Elbow Exoskeletons: Classification by Structure, Actuation, and Sensing Technologies. Sensors 2025, 25, 4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, L. Nature-Inspired Gradient Material Structure with Exceptional Properties for Automotive Parts. Materials 2025, 18, 4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]