Abstract

Dengue virus (DENV) infection is a significant public health concern in Indonesia, with increasing cases and severity posing challenges to the country’s healthcare systems. This study aims to develop and validate a machine learning-based prediction model for assessing dengue infection cases and their severity. The model incorporates epidemiological, clinical, and environmental factors to enhance early detection and resource allocation. Additionally, the model can be utilized to support logistics planning, such as the distribution of diagnostic kits and the preparation of health facilities in each region across Indonesia, ensuring timely and targeted responses to potential outbreaks. We applied various machine learning algorithms, including logistic regression, random forest, XGBoost, and SVM models, and evaluated them to determine the most effective predictive model. The results demonstrate the model’s efficacy in predicting dengue cases and severity, which can support public health interventions and clinical decision-making. Geospatial clustering and correlation matrices were generated to visualize risk patterns and support predictions. The XGBoost model demonstrated the highest performance, achieving an accuracy of 85%. Our findings suggest that integrating clinical and environmental data through machine learning (ML) techniques can significantly improve early detection and inform resource allocation strategies. The model offers a promising approach for public health surveillance and targeted interventions in dengue-endemic regions.

1. Introduction

Dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), caused by the dengue virus (DENV) and transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, remains a critical public health concern worldwide, including in Indonesia. The first reported cases in Indonesia appeared in Jakarta and Surabaya in 1968, and since then, cases have steadily increased across all provinces [1]. Throughout 2024, dengue cases in Indonesia had reached 257,271, resulting in 1461 deaths (Ministry of Health, Republic of Indonesia). The national trend reveals cyclical surges approximately every 6–9 years, shaped by complex drivers such as climate variability, rapid urbanization, and vector control effectiveness.

DENV, a member of the Flaviviridae family, comprises four serotypes. A pediatric urban cohort study using monotypic antibodies confirmed that all serotypes circulate in Indonesia [2]. Serotype dominance varies by geography and time [3], and phylogenetic analyses show that DENV-1 in Indonesia belongs to genotypes 1 and 4, DENV-2 to the Cosmopolitan genotype, DENV-3 to genotype 1, and DENV-4 to genotype 2 [4,5]. Previous studies showed that serotype, genotype, and strain influence disease severity [6,7,8]. Clinical manifestations range from asymptomatic to severe, with symptomatic infections classified into five categories: undifferentiated febrile illness (UF), dengue fever (DF), dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), dengue shock syndrome (DSS), and unusual dengue (UD) or expanded dengue syndrome (EDS) [9]. While most cases are mild, severe forms can be fatal if not detected and managed early. Delayed diagnosis is a key contributor to mortality, as early symptoms are often nonspecific. Timely and accurate identification remains essential for reducing deaths. Surveillance systems are therefore critical for detecting early signals of outbreaks and enabling rapid responses.

Despite sustained efforts, Indonesia still reports one of the world’s highest dengue case fatality rates, likely underestimating the true burden due to inconsistent surveillance across its > 17,000 islands. Challenges in case reporting and diagnosis delay effective intervention. These structural barriers highlight the need for more robust predictive systems to support early detection and resource allocation.

Traditional forecasting approaches such as regression-based and autoregressive time-series models (e.g., ARIMA, SARIMA) have been widely applied for dengue surveillance in both Indonesia and other endemic countries. While useful for short-term trend estimation, these models assume linearity and stationarity, limiting their capacity to integrate diverse inputs such as climate, demographics, and health system indicators [10,11]. As a result, their predictive power weakens when applied to heterogeneous populations, non-linear interactions, or longer forecast horizons. By contrast, machine learning (ML) methods can capture non-linear relationships, integrate high-dimensional and heterogeneous data sources, and typically achieve higher accuracy in complex prediction tasks.

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a promising alternative, offering the ability to capture complex, non-linear relationships and incorporate multidimensional datasets. Globally, numerous studies have applied ML for dengue forecasting, often demonstrating higher accuracy than traditional methods [11,12,13,14]. In Indonesia, ML has been tested in specific contexts: one study integrated meteorological, climatological, and epidemiological surveillance data using LSTM-based models to predict outbreaks at the district level, where ensemble methods such as Extra Trees performed best for short-term outbreak detection [11]. Another comparative analysis showed that deep learning approaches (RNN, BiLSTM, CNN-LSTM) outperformed SARIMA in capturing spatio-temporal transmission patterns, though their focus was limited to selected urban centers [7]. These efforts illustrate the potential of ML but remain constrained by narrow geographical coverage, short forecast horizons, or limited data integration. Crucially, no prior study in Indonesia has explicitly modeled inter-provincial spatial correlations or combined national epidemiological and clinical data to forecast dengue burden and severity.

Our prior research applied ML at the individual level to predict severity progression in dengue patients based on laboratory profiles, with strong performance [15,16]. Building on this foundation, the present study extends ML applications to a population-wide scale. The aim is to develop a machine learning-based model that forecasts dengue case counts for the subsequent year using historical dengue incidence data across all Indonesian provinces. The model predicts new geospatially clustered data from actual dengue incidence data. A provincial correlation incidence matrix is constructed to capture spatial relationships in dengue transmission and to enhance national-level prediction performance. This framing clarifies the study’s direct relevance to dengue surveillance by demonstrating how incidence-only data can support scalable, province-level forecasting. We also clarify that cluster-based methods are not the prediction target but are used only as an analytical component. Future work will extend this framework by integrating epidemiological, clinical [11,12], and environmental data to further improve predictive accuracy and public health utility.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study collected data from the National Dengue Control Programme, Ministry of Health, from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2024. These data were accessed for research purposes on 11 December 2024. Ethical approval for data exploration was given by the Research Ethical Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, No. KET-1847/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2024.

2.2. Data Collection

The data were obtained from health service facilities, primarily those affiliated with the District Health Office (Dinas Kesehatan), including public hospitals (RSUD) and primary health centers (puskesmas). The diagnostic method most commonly used was the rapid diagnostic test (RDT) for non-structural protein 1 (NS1) antigen detection, combined with IgM and IgG antibody testing. The sensitivity of the NS1 antigen test was 93.11% and 86.11% for primary and secondary infections, respectively [17]. When combined with IgG and IgM testing, the overall sensitivity increased to 100%. Case data were collected at the district level, reported to the provincial level, and subsequently submitted to the national Arbovirosis Working Team. The Arbovirosis Information System (SIARVI) was also used; however, its implementation was not yet fully optimized during the study period. Potential bias in the reported data was addressed through periodic validation meetings. These meetings were primarily intended to reconcile official case counts, review the use of RDTs—particularly NS1 testing—and support program planning. However, a systematic cross-checking mechanism for NS1 test results had not yet been implemented. In parallel, sample collection for PCR testing to determine dengue virus serotypes was conducted by the Public Health Laboratory (Balai Laboratorium Kesehatan Masyarakat, BTKL) within designated sentinel areas, including selected puskesmas and hospitals. Although this activity shared conceptual similarities with external quality assurance, it was not formally designed for that purpose. During the study period, this program was delayed and temporarily suspended following the transfer of laboratory responsibilities from the Directorate General of Disease Prevention and Control (Ditjen P2P) to the Directorate General of Health Services (Ditjen Binkesmas).

2.3. Data Storage and Cloud Computing Platform

The collected data were stored on the physical server of the Big Data Center (BDC) IMERI, located in Jakarta. The data were then analyzed using the BDC IMERI’s cloud computing platform, which is integrated with the data storage system. BDC, an Indonesian Medical Education and Research Institute (IMERI) unit, offers a comprehensive one-stop solution for data storage, labeling, and analysis. It is built on a high-performance physical server featuring a 128-thread CPU, 512 GB of RAM, 24 TB of storage, 1 GB of bandwidth, and 99.99% server uptime.

2.4. Machine Learning Models

We trained multiple machine learning algorithms to predict dengue incidence and classify provinces into low-, medium-, and high-risk clusters. The workflow consisted of three main steps: (i) Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) and preprocessing, (ii) K-Means clustering and geospatial mapping, and (iii) supervised learning using Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Support Vector Machines (SVM) were performed to generate cluster maps for each city in Indonesia.

2.4.1. Exploratory Data Analysis and Preprocessing

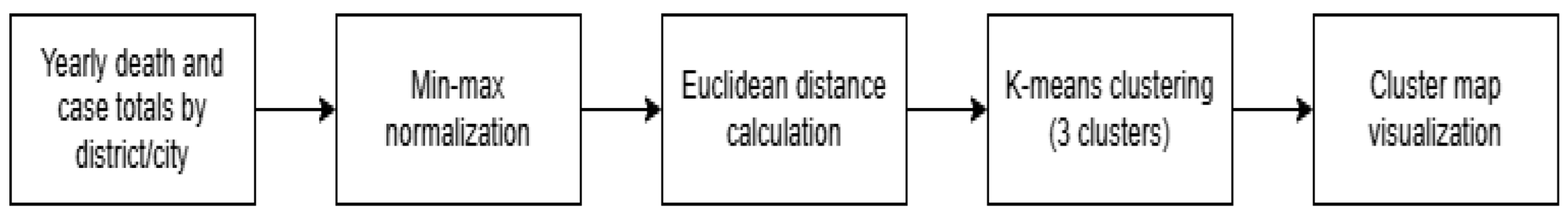

EDA was conducted to assess correlations between provinces based on incidence rates. Data were pivoted to generate a Pearson correlation matrix, which informed the clustering structure. Epidemiological data (cases and deaths) were aggregated per province per year. Normalization was applied using Min–Max scaling, and dimensionality reduction was performed using Euclidean distance, resulting in two reduced variables. To ensure reliable model training, pre-processing steps were performed prior to exploratory data analysis. First, raw data from epidemiological, demographic, health system, and environmental sources were cleaned, aggregated, and normalized. Specifically, the following were carried out:

- Aggregation: Monthly dengue incidence and fatality data were aggregated by province and year (2019–2024).

- Handling missing values: Missing values were checked and, where possible, imputed using temporal or provincial averages.

- Normalization: All numerical variables (e.g., case counts, population, hospital capacity) were scaled to the range [0, 1] using Min–Max scaling:

This transformation was applied to prevent features with large numerical ranges (e.g., population) from dominating those with smaller ranges (e.g., physician ratio) during clustering and model training. After pre-processing, exploratory data analysis (EDA) was performed to investigate temporal and spatial trends in dengue incidence:

- Correlation analysis: Annual incidence rates were pivoted by province to generate a Pearson correlation matrix.

- Dimensionality reduction: To visualize clustering patterns, variables were reduced to two dimensions using Euclidean distance-based similarity scores between provinces. These reduced dimensions provided input for clustering and subsequent geospatial visualization.

- Clustering: K-Means clustering was applied to the reduced dataset to group provinces into three incidence risk categories: low, medium, and high.

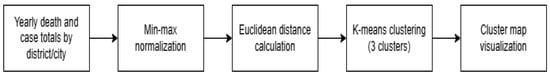

Figure 1 illustrate the rationale for dimensionality reduction which was to simplify high-dimensional health, demographic, and epidemiological data into two interpretable axes that could be visualized spatially on cluster maps while retaining the major structure of provincial differences.

Figure 1.

Complete pre-processing and EDA pipeline used to generate province-level clustering maps.

2.4.2. K-Means Clustering and Geospatial Analysis

The K-Means clustering algorithm was employed to classify Indonesian provinces into three dengue incident-risk categories: low, medium, and high. These clusters served as the primary outcome variable for subsequent supervised machine learning models, making it essential that they reflect meaningful epidemiological distinctions.

Clustering procedure was started with input variables included annual dengue incidence cases, annual dengue-related deaths, and the two dimension-reduced features derived from Euclidean distance similarity across provinces. Then, data were normalized using Min–Max scaling to ensure comparability between features of different magnitudes. The number of clusters (k = 3) was chosen a priori to correspond to interpretable risk levels (low/medium/high). To validate this choice, the elbow method and silhouette scores were examined, confirming that k = 3 provided both stable and well-separated groupings.

Cluster interpretation was defined as follows. Low-risk cluster (yellow): provinces with consistently low incidence and fatality rates relative to population size; Medium-risk cluster (orange): provinces with fluctuating incidence patterns and moderate case fatality rates; High-risk cluster (red): provinces with persistently high incidence rates, elevated fatality rates, or both, indicating severe disease burden and strain on local healthcare systems. These risk-based clusters represent a consolidated view of dengue burden by province, balancing incidence and mortality metrics. They were subsequently used as target classes for predictive modeling, where supervised machine learning algorithms attempted to forecast each province’s risk category for the following year based on epidemiological, demographic, healthcare, and environmental predictors.

In geospatial analysis, the clustering results were integrated with Indonesian provincial boundaries to produce annual geospatial maps (2019–2024). These maps visualize the spatial distribution of dengue risk and highlight temporal shifts across provinces, enabling both epidemiological interpretation and model validation.

Geospatial analysis was conducted to integrate the clustering results with Indonesia’s provincial boundaries and to produce annual risk maps from 2019 to 2024. The purpose of this step was twofold: first, to visualize the spatial distribution of dengue risk across the archipelago, and second, to capture temporal changes in risk levels across provinces. By mapping clusters to specific provinces, geospatial analysis allowed for the identification of regional patterns, such as provinces consistently classified as high risk, provinces showing fluctuating risk, and provinces transitioning between categories over time.

These maps provided an essential tool for interpreting the clustering results in a public health context. They revealed the heterogeneity of dengue burden across provinces, highlighting areas where surveillance and intervention efforts may need to be prioritized. In addition, the maps served as a form of model validation, as the spatial and temporal trends identified through clustering could be compared with known epidemiological patterns of dengue transmission. This ensured that the clustering outcomes were not only mathematically sound but also epidemiologically meaningful.

2.4.3. Logistic Regression (LR)

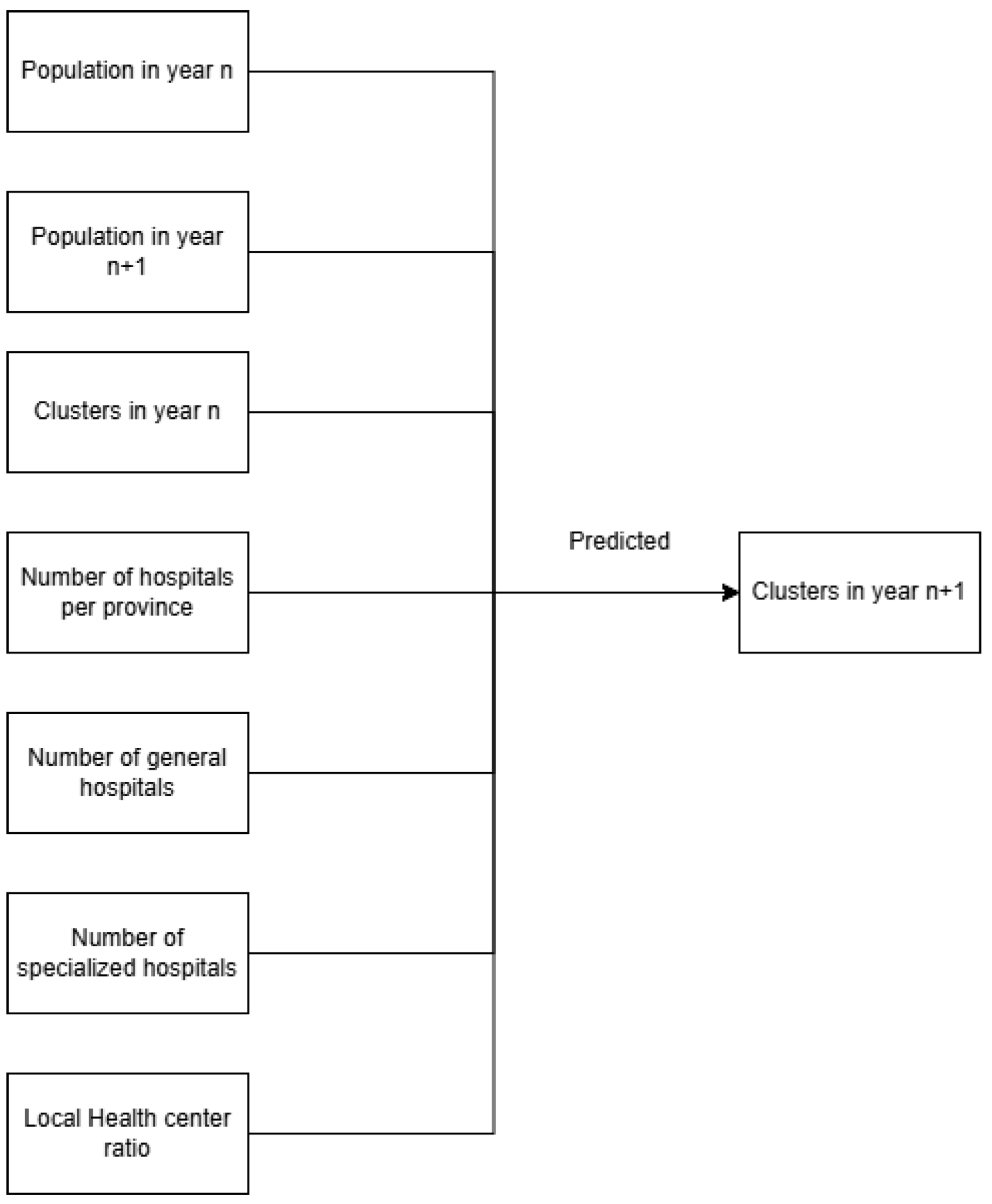

The Logistic Regression (LR) model was chosen because of its simplicity, interpretability, and suitability for binary and categorical classification tasks. In this study, LR was used to predict the dengue incident-risk cluster of each province for the following year, based on features from the current year. The input variables are the model included epidemiological, demographic, and health system features. These comprised provincial population size, cluster assignment from the previous year, number of hospitals (public and private), and the ratio of community health centers (Puskesmas) to population. The “community health center ratio” was defined as the number of Puskesmas per 100,000 population, which provides a proxy for primary healthcare availability. To address concerns of feasibility in practical surveillance settings, the “population in year n + 1” variable (used initially in exploratory runs) was excluded from the final predictive model, since such information would not be available prospectively in real-world applications.

For binary classification of dengue incidence, provinces were categorized as high incidence if their incidence rate exceeded the national median for that year, and as low incidence otherwise was used as classification of thresholds. Similarly, fatality was classified as high fatality if the case fatality rate exceeded 0.5% (WHO threshold for dengue severity) and low fatality if it was ≤0.5%. These thresholds ensured that outcomes were epidemiologically meaningful and comparable across provinces. The LR model was trained with a maximum of 1000 iterations to ensure convergence, with a fixed random state (42) to allow reproducibility. Model performance was evaluated using standard classification metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

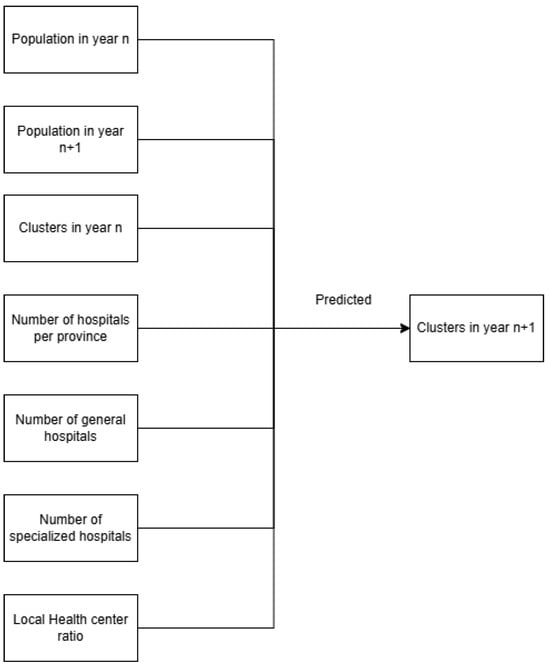

Logistic Regression was used as a baseline model due to its simplicity and interpretability. Input features included provincial population (current and projected), hospital counts (public and private), community health center ratio, and prior-year cluster assignments. The text classification process can be divided into two types: binary classification and multiclass classification. The softmax function works well in the output layer for multiclass classification tasks, because it produces vectors with a length corresponding to the number of classes and is normalized to have a sum of probabilities equal to 1. Categorical cross entropy is the loss function used in multiclass classification tasks [18]. Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) was applied for model fitting, with 1000 iterations and random state fixed at 42. Evaluation included classification metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score) and diagnostic measures (odds ratios, Wald test, likelihood ratio test). ROC-AUC values were used to assess discrimination (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Model classification input (left) and output (right).

2.4.4. Decision Tree (DT) Model

The Decision Tree (DT) model was applied as a non-linear classification approach to complement the Logistic Regression (LR) model. Although DTs do not always outperform LR, they can achieve superior performance in settings where relationships among predictors and outcomes are non-linear or involve interaction effects [19].

For this study, the DT was trained using the same epidemiological, demographic, and health system variables as the LR model. To ensure reproducibility, the random state was set to 42. Hyperparameters, including the maximum tree depth, minimum samples required for node splitting, and the splitting criterion (Gini impurity vs. entropy), were tuned to optimize model performance while mitigating overfitting [20].

The DT model’s predictive performance was evaluated using standard classification metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Results from the DT model were subsequently compared to those from LR to assess whether incorporating non-linear modeling improved predictive accuracy. DTs split the dataset into subsets based on feature values, recursively partitioning the data until a stopping criterion was met. This hierarchical structure allows DTs to model complex, non-linear relationships between predictors and outcomes while remaining interpretable [21].

2.4.5. Random Forest (RF) Model

The Random Forest (RF) algorithm, an ensemble method based on decision trees, was implemented to improve prediction accuracy and reduce overfitting. In this approach, multiple decision trees are constructed using bootstrap sampling of the training data. At each tree split, a random subset of predictor variables was considered, introducing variability and reducing correlation between trees. For classification, the final prediction was obtained through majority voting across all trees.

Model performance was assessed using n estimators 200 and random state 42 [22]. Previous research using hyperparameters of models specifically, the number of estimators (100–200) [23]. Choosing the right number of estimators entails balancing computational efficiency and prediction accuracy, as increasing the number of decision trees improves model stability but also necessitates more processing power.

Performance metrics included accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, providing a comprehensive evaluation of classification performance. Additionally, feature importance scores were extracted to quantify the relative contributions of epidemiological, demographic, healthcare, and environmental variables to model predictions.

2.4.6. XGBoost (XGB) Model

Given the favorable performance of the RF and LR models, XGBoost was subsequently applied as a more advanced approach to compare model performance. The label encoder was turned off in this model to prevent the model from automatically encoding the clustering results into numeric values. The evaluation metric was set using a Logarithmic Loss (Logloss) function to ensure probability-based prediction, and the random state was set to 42 to ensure reproducibility. The input and output of the XGBoost model were the same as those of the LR and RF models.

Model validation was performed using stratified. The dataset was randomly divided into 10 folds, while preserving the proportion of outcome classes in each fold. For each iteration, 9 folds were used for training and 1 fold for testing, and this process was repeated until each fold had been used once as a test set. The final performance was reported as the mean and standard deviation of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score across the 10 folds. This approach minimized the bias from a single random split and provided a more reliable estimate of the model’s generalization ability.

2.4.7. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

The Support Vector Machine (SVM) model was trained using scikit-learn’s SVC implementation with an RBF kernel, as it is effective in capturing non-linear relationships [24]. To obtain calibrated probability estimates, the probability = True option was enabled, which applies Platt Scaling [25]. Hyperparameters, including the regularization parameter (C) and kernel coefficient (gamma), were tuned using grid search with 5-fold cross-validation. The model was trained on 75% of the dataset and tested on the remaining 25%. Performance was evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC [26].

2.4.8. Model Training and Validation

The dataset was split into training (75%) and testing (25%) subsets (n = 1218 and n = 406, respectively). Performance was compared across models using classification metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score) and ROC-AUC values. For continuous predictions, Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) was also computed. Table 1 give comparison for each model.

Table 1.

Summary of Models.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia (No. KET-1847/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2024). The research utilized aggregate secondary data that were fully de-identified before analysis. No personally identifiable information was collected, stored, or analyzed at any stage of this study. The ethics committee waived informed consent given the nature of the dataset and the absence of individual-level data. All research activities were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report, ensuring respect, beneficence, and justice in handling public health data.

3. Results

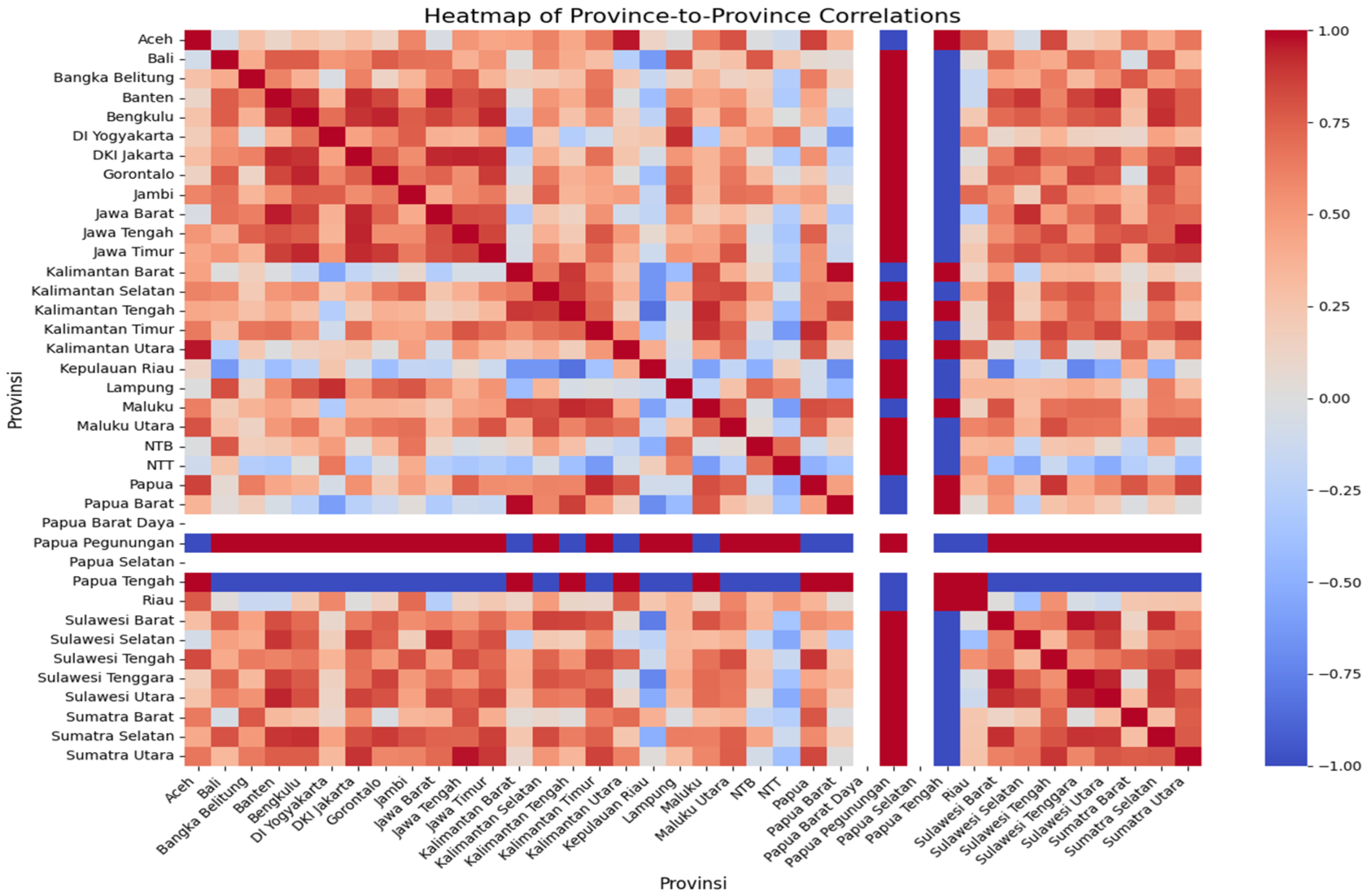

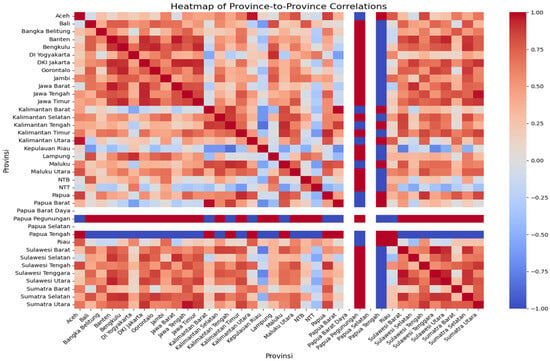

3.1. Pearson’s Correlation Matrix

We used Pearson’s correlation matrix to assess similarities in dengue incidence trends across provinces in Indonesia (Figure 3). In this heat map, the color scale reflects the correlation coefficient: dark red indicates a strong positive correlation (two provinces exhibit similar incidence rate trends over time), while dark blue indicates a strong negative correlation (the trends move in opposite directions). Intermediate colors represent weaker or moderate correlations.

Figure 3.

The correlation matrix of the incidence rate trend of all provinces in Indonesia can be used to predict the transmission of DENV.

Based on the correlation matrix, provinces located geographically close to each other often on the same island tended to show higher correlations in incidence trends, suggesting possible spatial clustering of transmission patterns. For example, Aceh province showed a strong positive correlation with Kalimantan Utara and Papua Tengah (dark red), indicating that incidence rates in these provinces varied in similar directions over time. By contrast, Aceh exhibited a strong negative correlation with Papua Pegunungan (dark blue), meaning their incidence trends differed substantially. This type of correlation analysis can help identify provinces with synchronized transmission dynamics, which is valuable for regional dengue prevention strategies.

The correlation matrix was used to predict the transmission of DENV in Indonesa using the preprocessed data. The red color showed the highest incidence rate, and turned to blue when the incidence rate was low. Based on Pearson’s correlation matrix, it can be assumed that provinces located close together on one island will show a similar trend in the incidence rate. This analysis was expected to be used for the DENV prevention strategy.

Figure 3 shows the incidence rate correlation of every province in Indonesia. It indicates that Aceh province has a similar incidence rate trend to Kalimantan Utara and Papua Tengah because Pearson’s correlation map shows a similar dark red color. In contrast, the incidence rate trend of Aceh province was significantly different from Papua Pegunungan because the correlation map shows that Papua Pegunungan has a dark blue color, while Aceh has a dark red color.

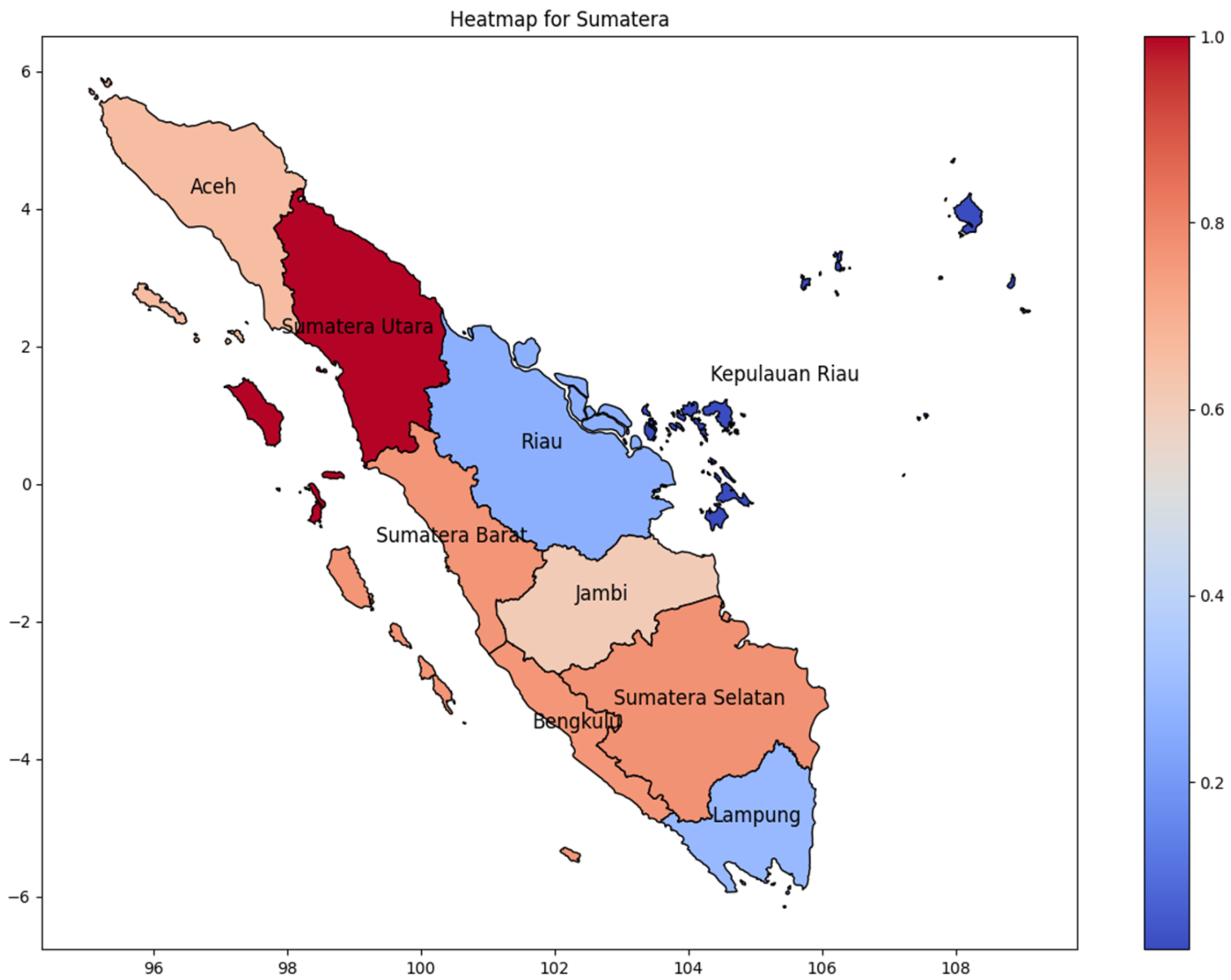

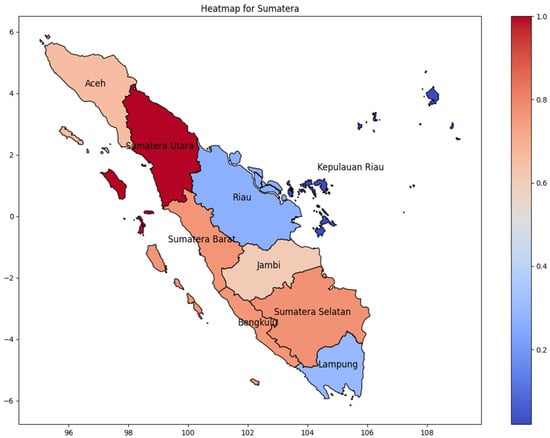

Sumatera Utara province has the highest number of dengue infections in Sumatra Island during the 2024 period. We are comparing the incidence rate based on the correlation matrix (Figure 3) to predict the distribution of dengue infection. Figure 4 shows the incidence rate correlation of every province on Sumatera Island, Indonesia. As Indonesia’s westernmost island, the highest cases were found in Sumatera’s westernmost province, and as the province moved further east, the incidence rate of DENV decreased gradually. As shown in Pearson’s correlation matrix, Sumatera Utara has the highest incidence rate, while Kepulauan Riau has the lowest incidence rate. It can be concluded that high cases occur in one province and then spread to the surrounding area. Moreover, Kepulauan Riau consists of many islands, which are distributed and separated by the sea, thus reducing the infection chain. Lampung, a province at the bottom of Sumatra Island, has a low incidence rate due to its distance from North Sumatra. It is critical to take into consideration that Riau Province, which is near the highest province, also has a low incidence rate.

Figure 4.

The correlation of the incidence rate of all provinces in Sumatera Island can be used to predict the transmission of DENV compared with the highest incidence case in Sumatera Island.

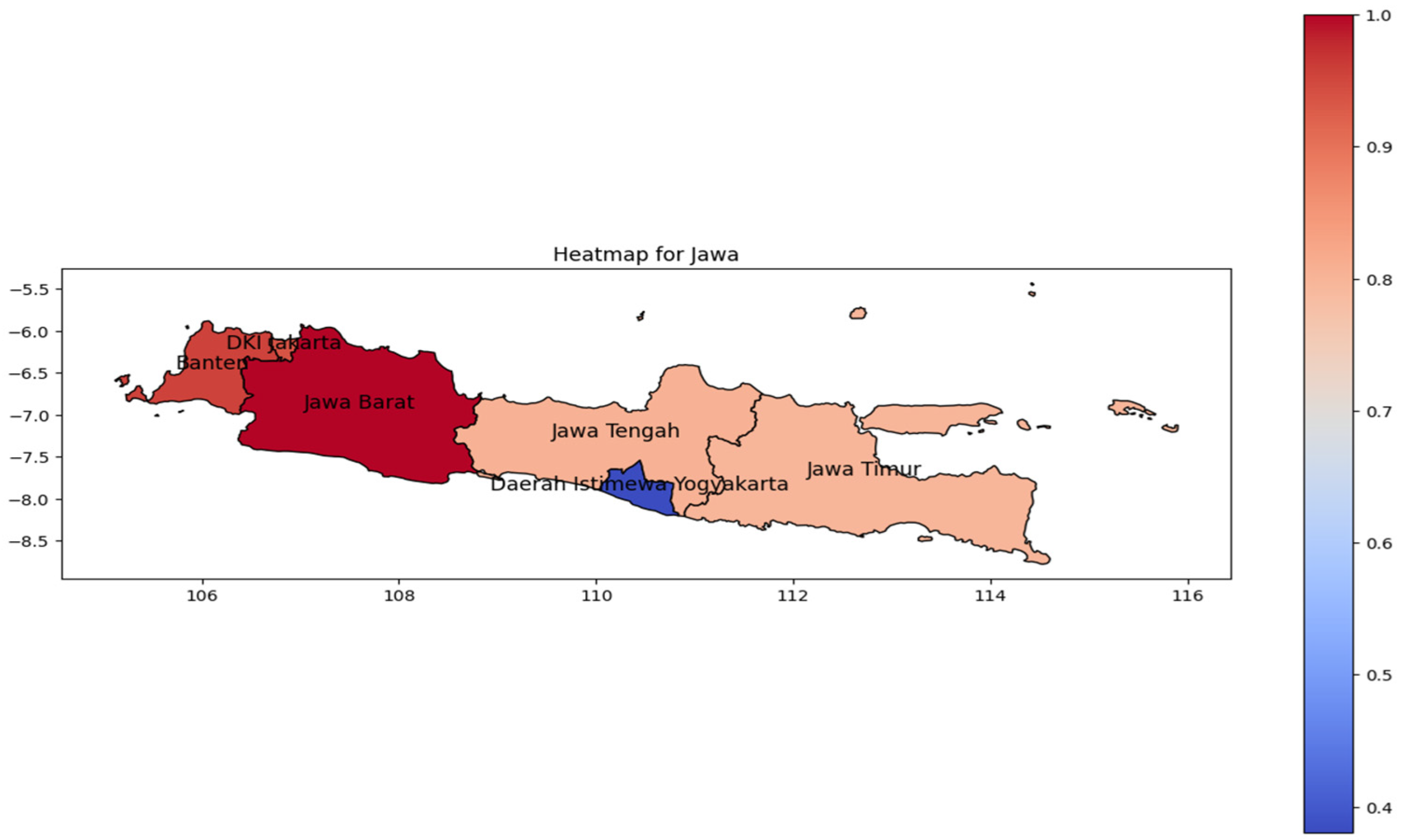

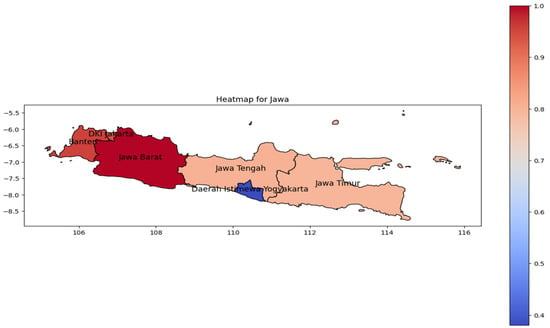

Similar patterns were observed in Java Island (Figure 5). The highest incidence rate (represented by the red color on the heat map) was concentrated in West Java as the most populous province [27]. In relation to its population, the incidence rate pattern spreads from Banten to Jakarta Province in western Java. However, the population tends to be reduced toward the eastern region; the spread to the east is likewise in line with the geographic trend.

Figure 5.

The correlation of the incidence rate of all provinces in Java Island can be used to predict the transmission of DENV compared with the highest incidence case in Java Island.

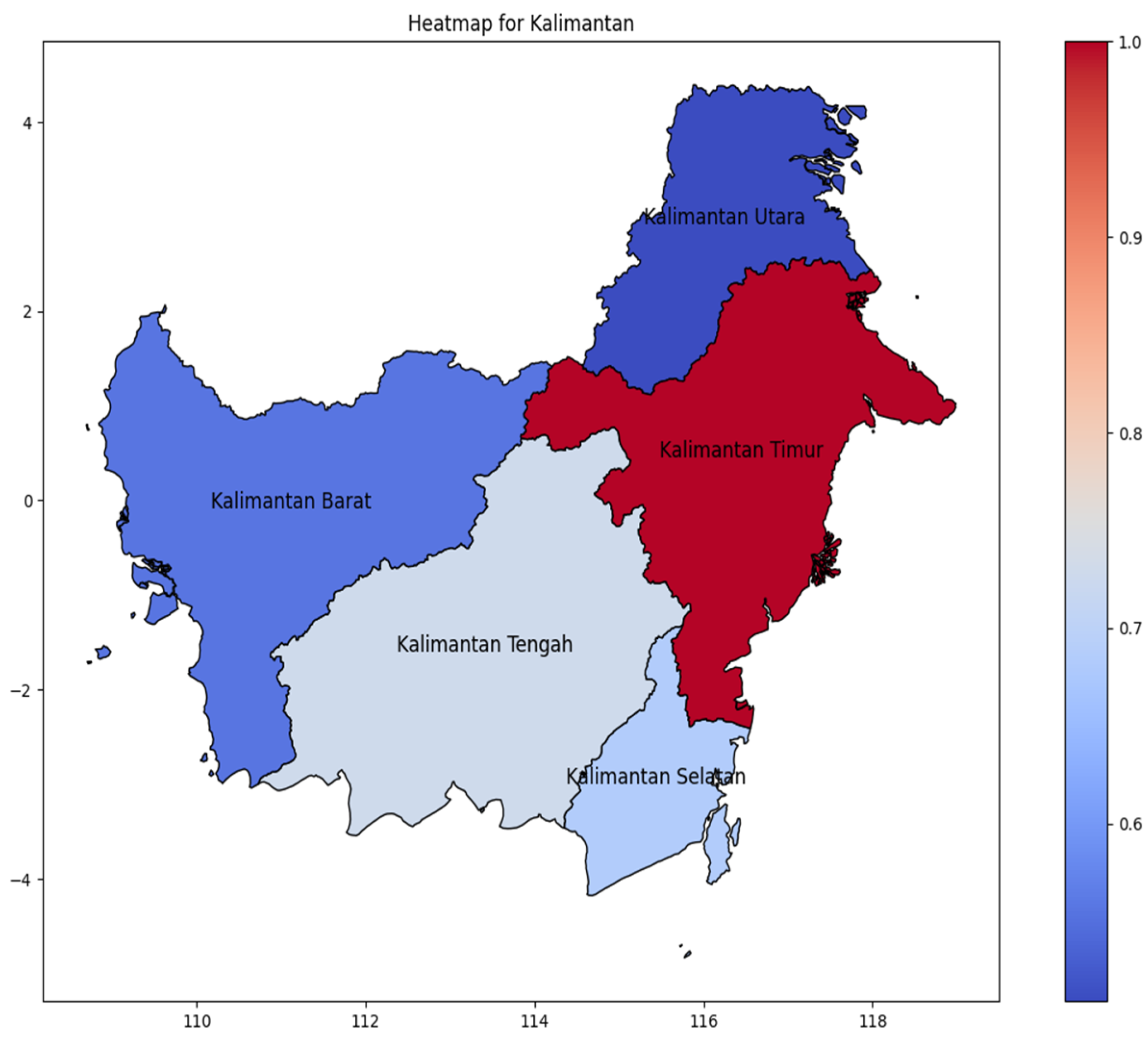

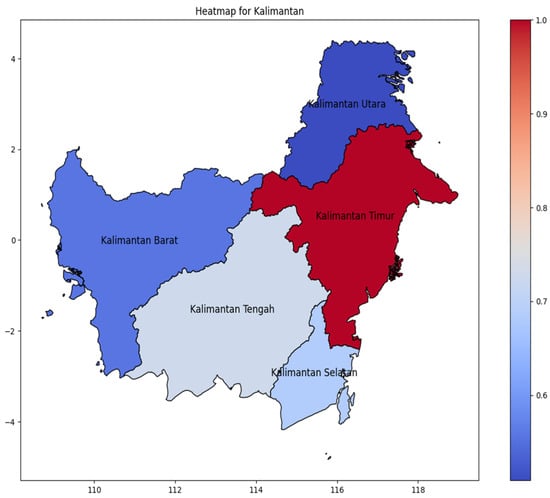

Kalimantan Island (Figure 6) distribution of DENV incidence rate is concentrated in Kalimantan Timur as the easternmost area, spreading to the center in Kalimantan Tengah. Contrary to Sumatera and Java, distribution of incidence cases does not spread gradually, but has a significant value from areas with have amount incidence rate to the fewer.

Figure 6.

The correlation of the incidence rate of all provinces in Kalimantan Island can be used to predict the transmission of DENV compared with the highest incidence case in Kalimantan Island.

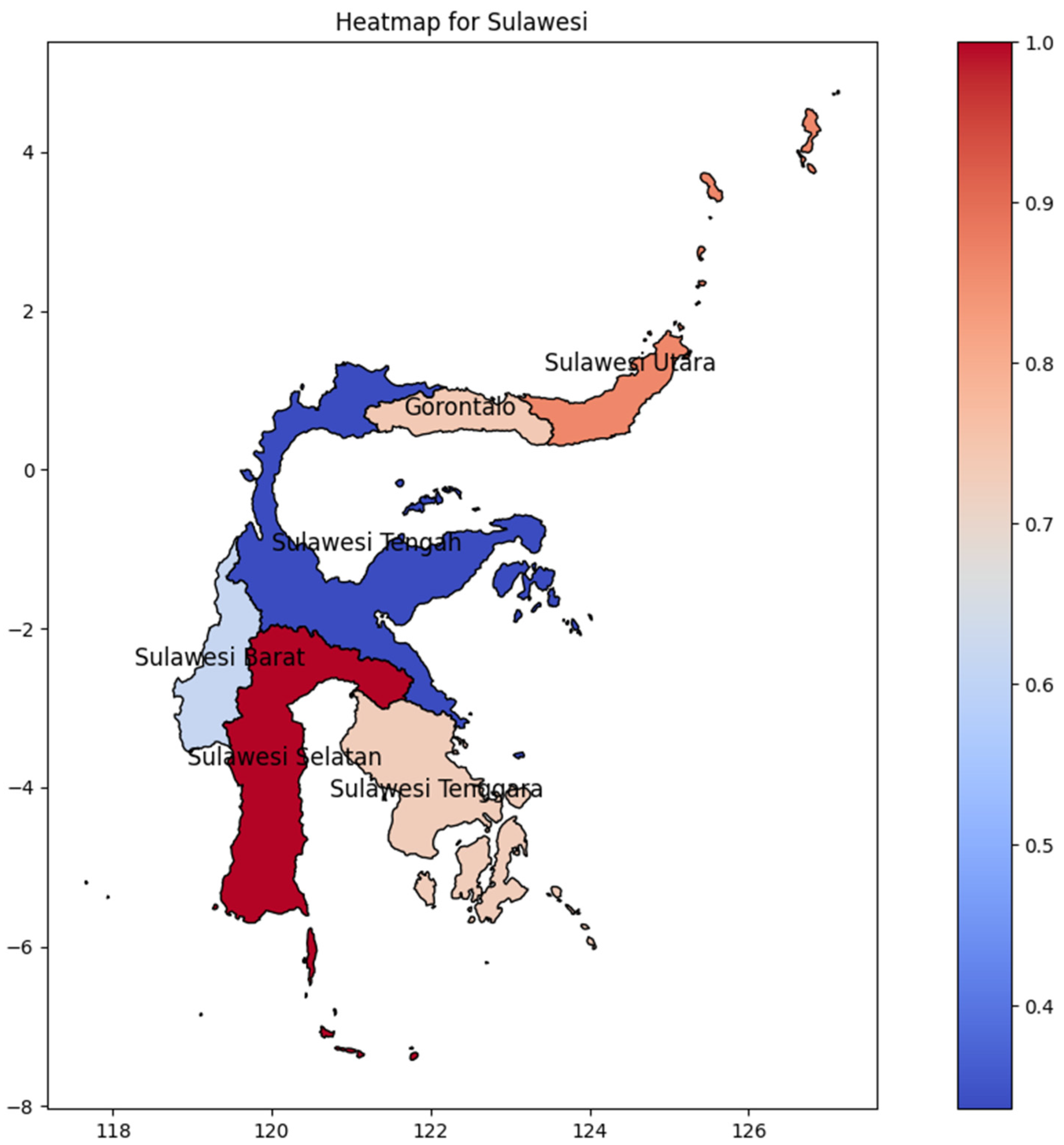

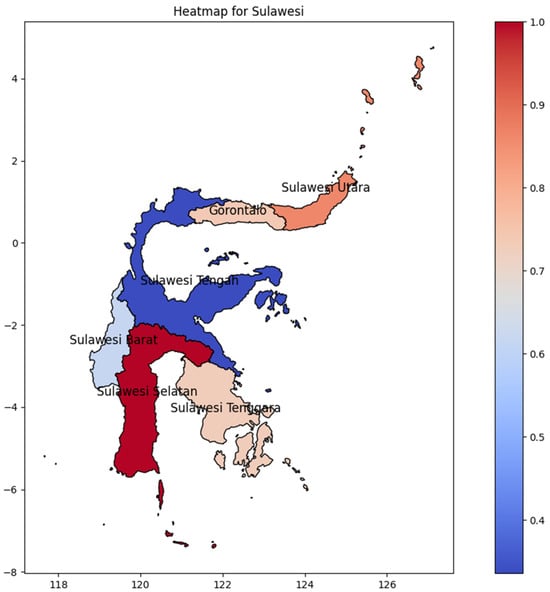

Sulawesi Selatan Province was the hotspot on Sulawesi Island (Figure 7), showing a distribution pattern in which initially emerged at the bottom and advanced gradually northward. Surprisingly, the second-highest DENV incidence rate on the island is found in Sulawesi Utara Province at the northernmost part of the region, and it spreads to the middle of Sulawesi Tengah with approximately the same values. Maluku, a nearby island of Sulawesi, could possibly be the determining factor of that evidence, particularly in Maluku Island, where Maluku Utara Province has the highest DENV incidence rate. However, Sulawesi Selatan has the highest DENV incidence rate, which could be influenced by the location of Makassar’s main international airport, in Makassar, Sulawesi Selatan.

Figure 7.

The correlation of the incidence rate of all provinces in Sulawesi Island can be used to predict the transmission of DENV compared with the highest incidence case in Sulawesi Island.

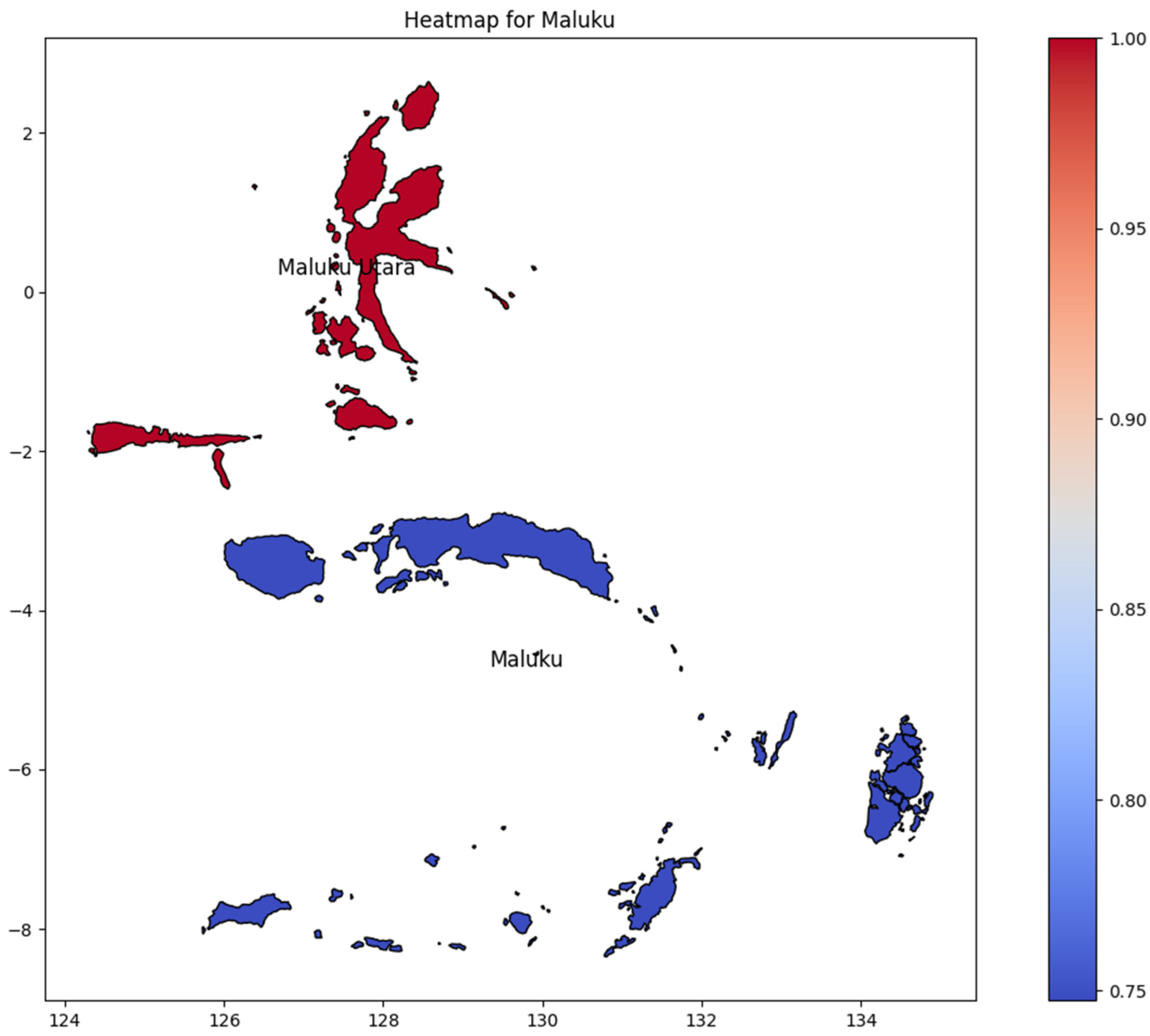

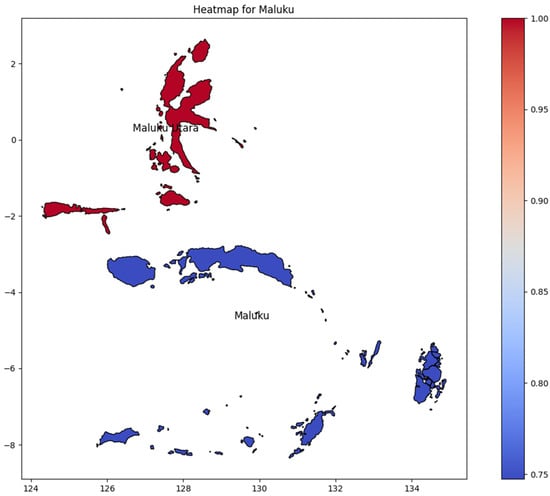

Maluku consists of only two provinces (Figure 8): Maluku and Maluku Utara (North Maluku). Maluku Utara had the highest DENV incidence rate; however, there was no significant difference between the provinces of Maluku and Maluku Utara regarding the number of DENV incidence rates. It is important to note the outcome was potentially determined by comparing only two provinces.

Figure 8.

The correlation of the incidence rate of all provinces in Maluku Island can be used to predict the transmission of DENV compared with the highest incidence case in Maluku Island.

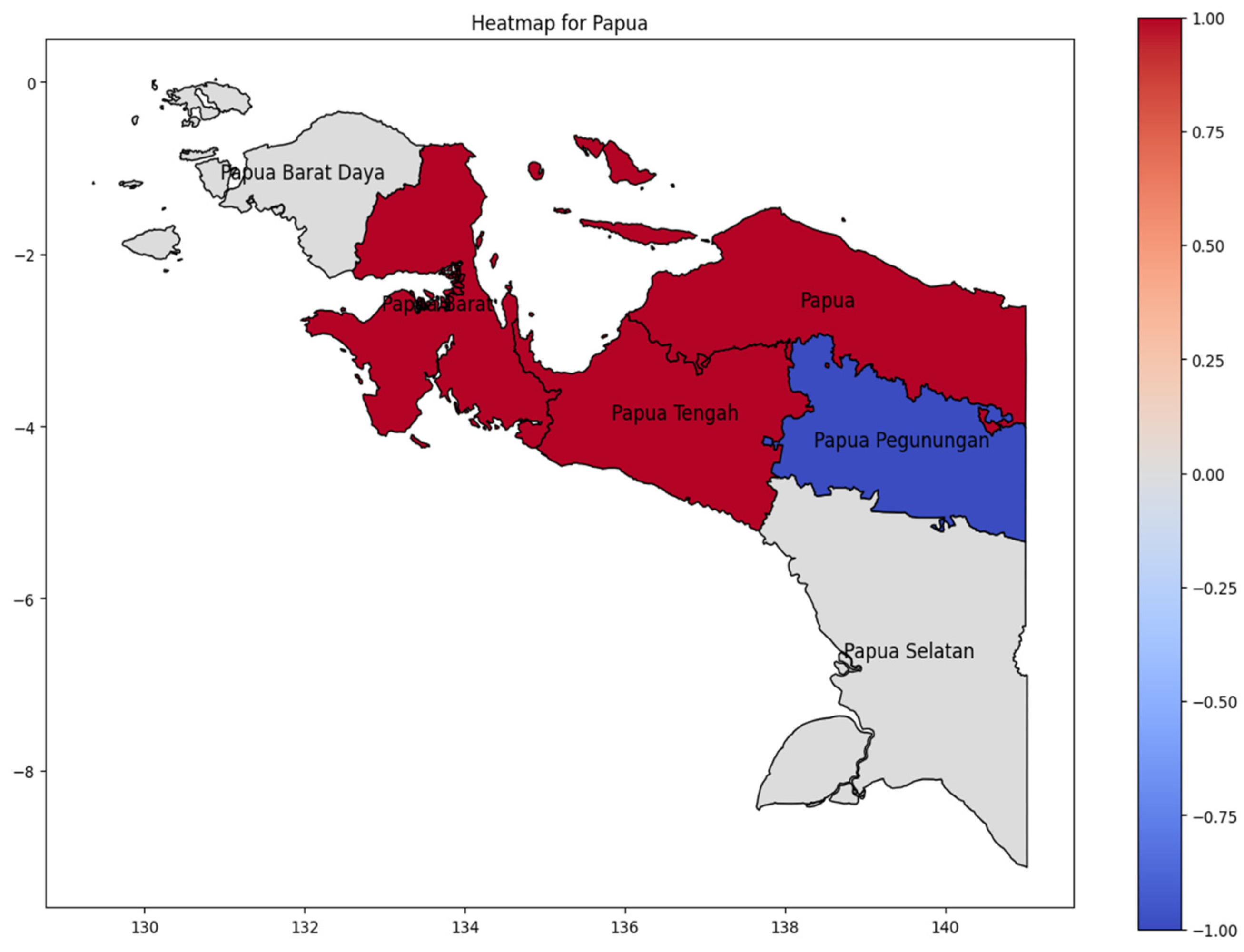

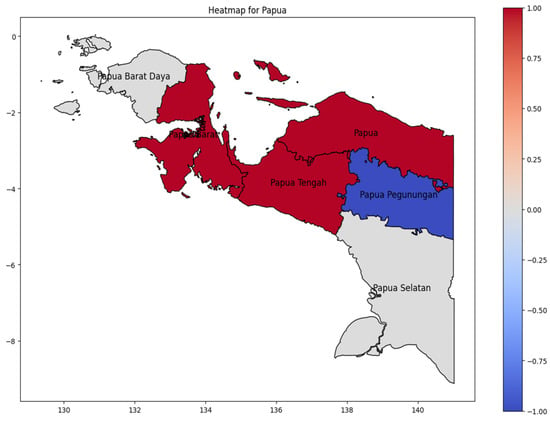

On Papua Island (Figure 9), the hotspot area was Papua Tengah Province as the higher DENV case in Papua Island during 20024, with the dengue incidence rate spreading westward to Papua Barat (West Papua) and upward in Papua Province. The lowest number of cases occurred in Papua Pegunungan (Highland Papua). The lowest incidence occurs in Papua Pegunungan (Highland Papua), a pattern consistent with studies demonstrating that cooler highland climates suppress Aedes aegypti mosquito populations and dengue virus transmission efficiency [28].

Figure 9.

The correlation of the incidence rate of all provinces in Papua Island can be used to predict the transmission of DENV compared with the highest incidence case in Papua Island.

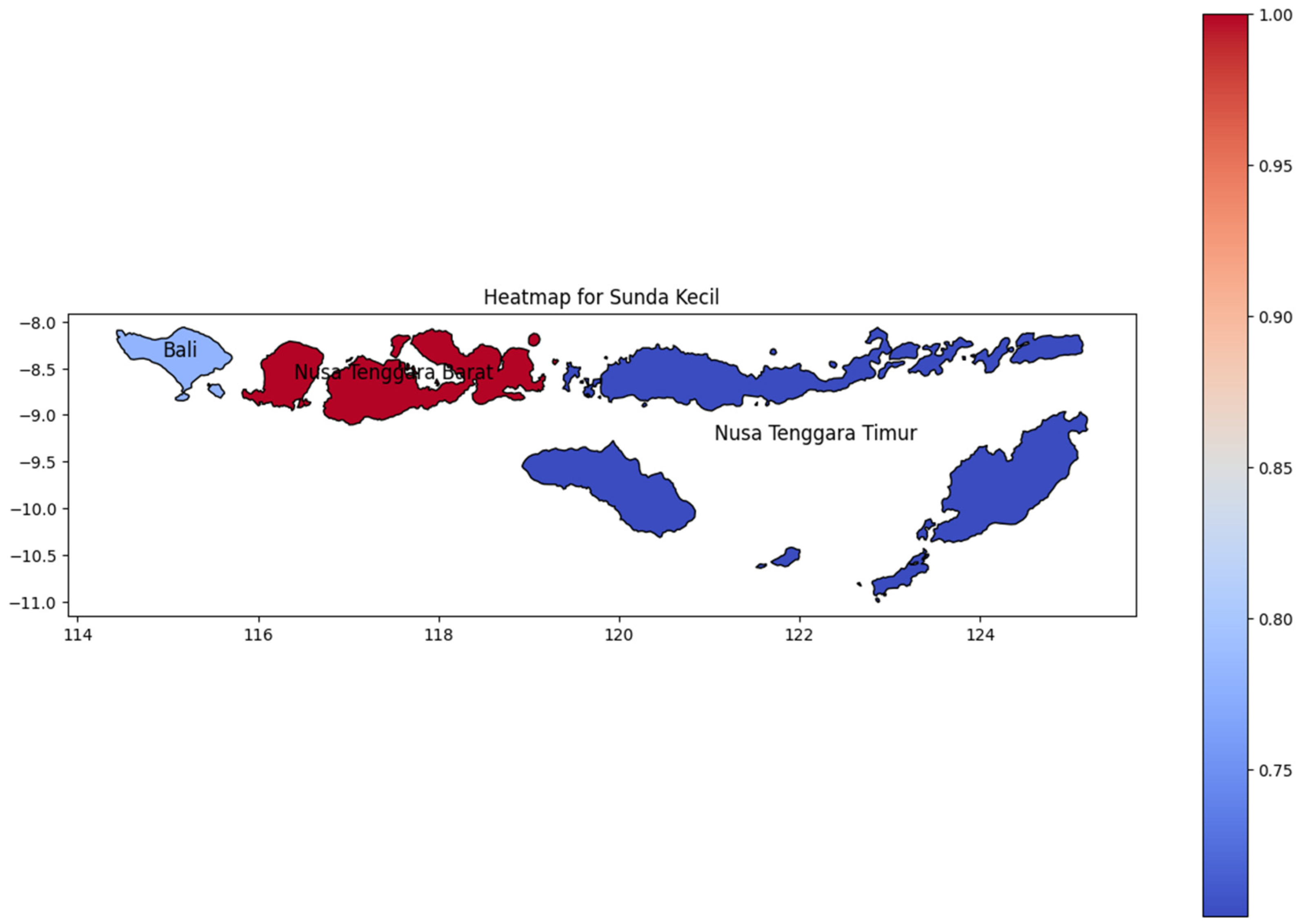

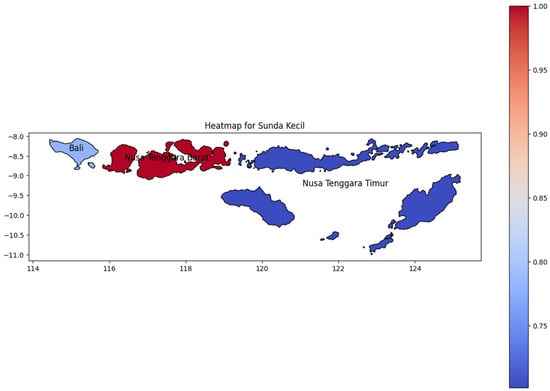

Like Maluku, Sunda Kecil (Figure 10) has a few provinces that consist of many islands. Nusa Tenggara Barat (West Nusa Tenggara), adjacent to Bali, has the highest dengue incidence rate in this region. Bali Island, consisting of a single province, also showed a high incidence rate on the heat map. As Indonesia’s top tourist destination, Bali has a highly diverse population, which likely contributed to the spread of dengue to neighboring regions. As Papua Island, the DENV cases decline to the easternmost area which Nusa Tenggara Timur as the easternmost region in Sunda Kecil.

Figure 10.

The correlation of the incidence rate of all provinces in Sunda Kecil Island can be used to predict the transmission of DENV compared with the highest incidence case in Sunda Kecil Island.

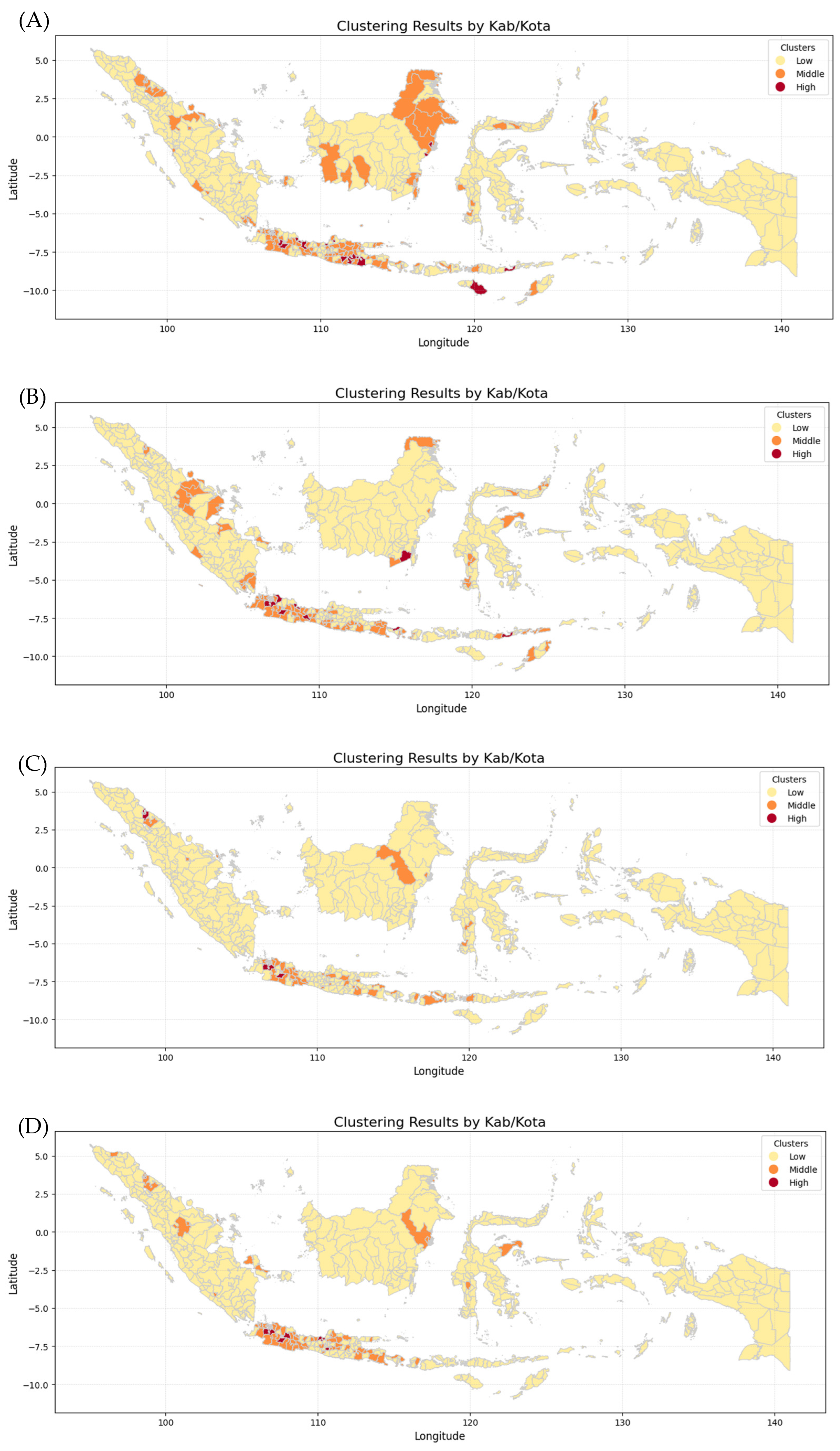

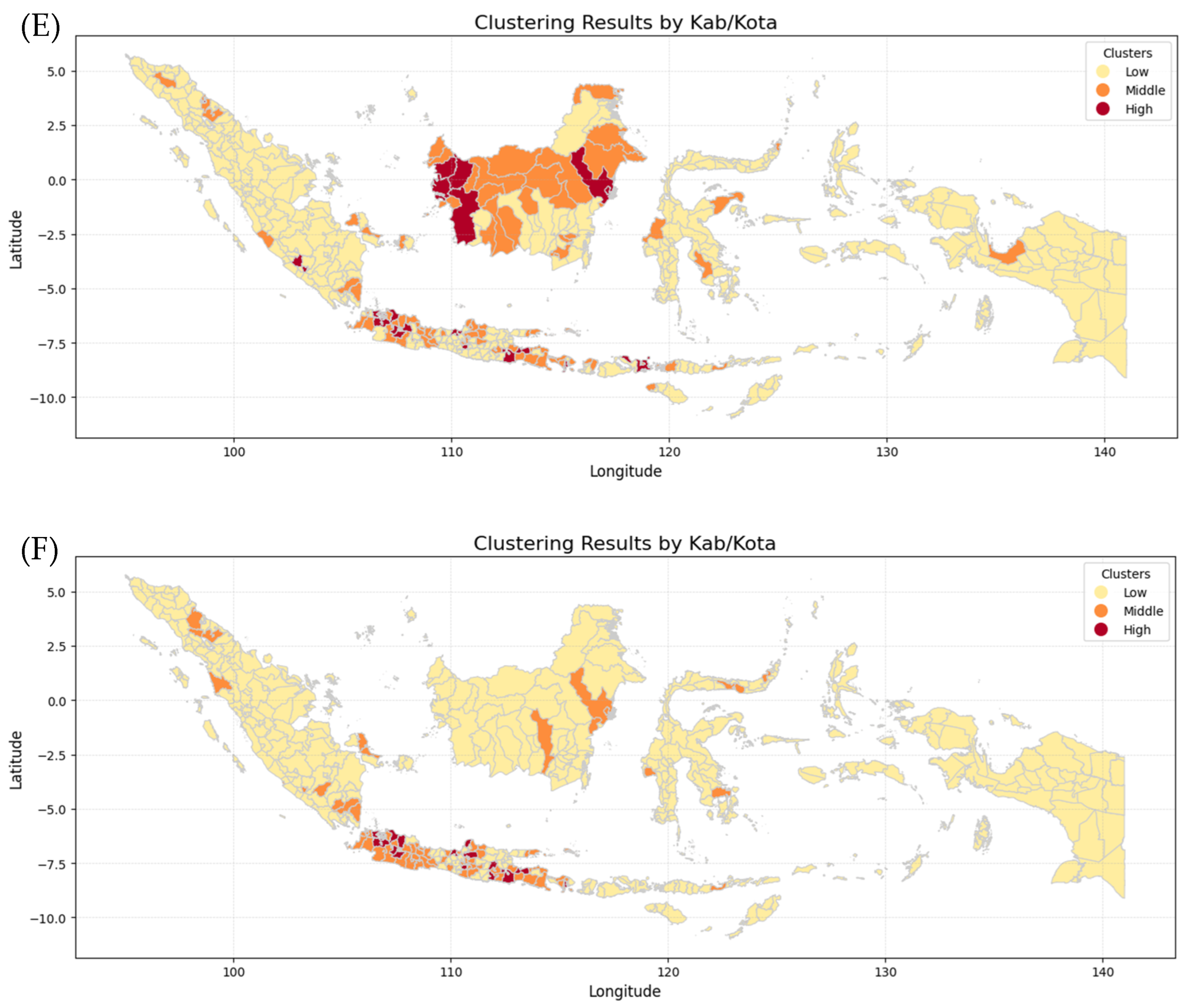

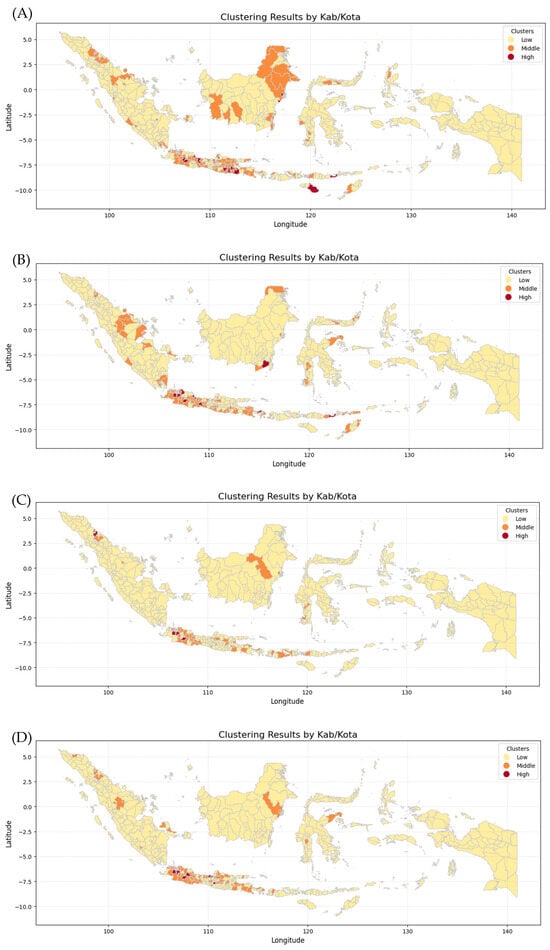

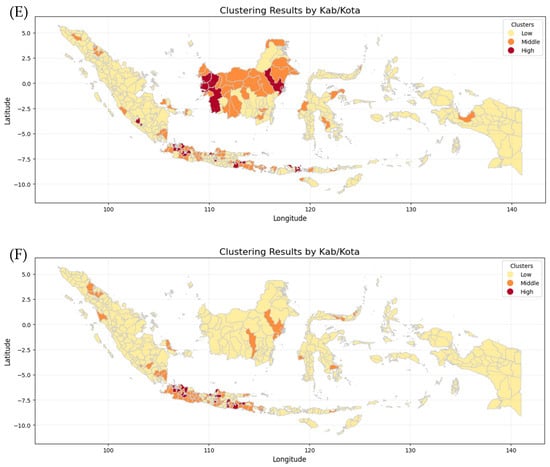

3.2. Geospatial Cluster Maps

Figure 11 shows six maps generated by combining the K-Means Clustering method with Geospatial Analysis, which differentiates every province by incidence risk. The maps show that Papua, Sulawesi, and Maluku Island have the lowest incidence risk because they show mostly yellow color from 2019 to 2024, while Kalimantan and Sumatera Island show moderate incidence risk because they show not only yellow color but also orange and even red color in 2020 and 2023. In contrast, Java Island has the highest incident risk because the maps are almost red and orange from 2019 to 2024. The clusters for each province in each year were then analyzed using various Machine Learning methods employed in this research, including Logistic Regression (LogReg), Decision Tree (DT), XGBoost, and Support Vector Machine (SVM).

Figure 11.

Clustering Maps of every province in Indonesia: (A) dengue cases in 2019, (B) dengue cases in 2020, (C) dengue cases in 2021, (D) dengue cases in 2022, (E) dengue cases in 2023, (F) dengue cases in 2024.

The k-means algorithm is generally the most well-known and used clustering method. Various extensions of k-means have been proposed in the literature [29]. Geospatial analysis refers to a collection of techniques and tools for geographic analysis and GIS data processing software engines [30]. By applying those methods, data on the dengue cases spreading pattern in each province and fatalities could be analyzed to forecast trends and potential outcomes for the coming year.

3.3. Performance Metrics in Four ML Models

Table 2 shows the comparison of XGBoost with other models. XGBoost achieved the highest accuracy, reaching 85%. While the XGBoost precision in low cases was 90%, there was a decline in the high and medium cases, as shown in Table 2. A more detailed comparison between XGBoost and SVM is necessary, as SVM demonstrates a higher precision value despite having a lower recall. Accuracy refers to how often a model makes correct predictions. However, accuracy alone may not be the best metric in imbalanced datasets, where one class significantly outweighs others.

Table 2.

Details of XGBoost analysis results for low, medium, and high cluster prediction. Yellow indicates the best-performing model, while orange indicates metrics where SVM or Logistic Regression outperformed XGBoost.

In such cases, precision, recall, or F1-score metrics might be more informative. Precision measures how many of the optimistic predictions are correct. For example, if a model predicts that Province A will experience dengue cases in the following year and it does, the model demonstrates high precision. Besides precision, which measures how many predicted positive cases are correct, we also consider recall (or sensitivity), which measures how many actual positive cases the model correctly identifies. Another important metric is the F1-score, representing the harmonic average of precision and recall. It provides a balanced measure of model performance, especially when precision and recall are not evenly distributed. If these two values differ significantly, the F1-score will be lower, indicating an imbalance in the model’s predictions. Although Logistic Regression (LogReg) shows higher accuracy and precision, it is too simple for complex data analysis. Therefore, it is crucial to emphasize the use of more advanced models in future research, with XGBoost as the top priority (priority 1) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) as the second priority (priority 2).

Table 2 shows the analysis results for low, medium, and high cluster prediction in every model. XGBoost shows superior performance in identifying low-risk areas because it has higher precision than the others. But SVM and logistic regression can also be considered as good models for identifying low-risk areas because they show greater recall value than XGBoost. As for identifying medium-risk areas, XGBoost also shows superior performance because it has higher precision, recall, and F1 score results than the others. In contrast, SVM shows greater precision in identifying high-risk areas even though it has smaller recall and F1 score values than XGBoost. Accordingly, the selection of models may be optimized based on the specific objectives of the application.

4. Discussion

Considering the machine learning application in infectious disease presents challenge and limitation into model adaptability [31], the study highlights comparison of the effectiveness of ML models in predicting dengue incidence and fatality cases. The K-Means method is an unsupervised learning algorithm for clustering data points into K groups based on similarity. In this study, k-means clustering was applied as an unsupervised learning approach to identify natural groupings in the data based on the distances between observations. Because k-means is sensitive to the random initialization of centroids (random seed), different initializations can lead to variations in cluster assignments and inter-cluster distances. To address this issue and to determine the most appropriate number of clusters, the elbow method was employed. The elbow method evaluates the relationship between the number of clusters (k) and the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS), allowing the identification of an optimal k at the point where further increases in k yield only marginal improvements. By selecting k at this “elbow” point, the clustering process achieves a balance between model simplicity and clustering accuracy. As a result, the clusters formed exhibit more appropriate and stable inter-point distances, reflecting better separation and compactness, while reducing the bias introduced by random initialization. This approach ensures that the chosen k-means configuration produces meaningful and reliable cluster structures for subsequent analysis.

The algorithm iteratively assigns each point to the nearest cluster center (centroid) and updates the centroids until convergence. Geospatial analysis involves using location-based data to identify patterns, relationships, and trends. Linear and nonlinear dimensionality reduction techniques such as PCA, t-SNE, and UMAP serve different analytical purposes. PCA projects the data onto orthogonal linear components that maximize variance, which can reduce dimensionality but may complicate the interpretation of individual variables in the transformed space. In contrast, t-SNE and UMAP are primarily designed for visualization, emphasizing local neighborhood structure and requiring several hyperparameter choices, which can limit their suitability for reproducible clustering and distance-based interpretation.

In this study, Euclidean distance, PCA, and UMAP were explored. PCA-based representations resulted in a reduced feature space that altered the original data structure, which may affect clustering outcomes and interpretability. UMAP produced low-dimensional embeddings optimized for visualization rather than preserving global distance relationships. Euclidean distance, by contrast, does not transform or reduce the original feature space; instead, it measures similarity directly using the original variables. This approach preserves the original data structure while producing a distance matrix suitable for clustering. Therefore, Euclidean distance was selected to maintain direct interpretability of interprovincial similarities in the original feature space and to ensure compatibility with distance-based methods such as K-means clustering.

Unlike K-Means, which relies on Euclidean distances, geospatial methods explicitly incorporate spatial relationships. Geospatial methods are specifically designed for location-based data and provide more accurate insights in spatial applications. The elbow method was used to avoid random sheet in select the number of clusters by examining the relationship between k and the within-cluster sum of squares. A clear elbow was observed at k = 3, supporting its selection as the optimal number of clusters in this study.

Logistic Regression (LR) is a statistical method commonly used in machine learning for binary classification tasks. It estimates the probability that a given input belongs to a particular class using the logistic (sigmoid) function. The key concepts of logistic regression are the Sigmoid Function, Decision Boundary, Loss Function, Gradient Descent, and Extensions. The Sigmoid Function converts linear combinations of input features into probabilities ranging from 0 to 1.

The Decision Boundary in logistic regression classifies an instance as class 1 if the predicted probability is above a certain threshold (typically 0.5) and class 0 otherwise. The Loss Function is log-loss (binary cross-entropy) to optimize model parameters. Gradient Descent is commonly used to optimize the best coefficients (weights). Logistic regression can be extended to Multinomial Logistic Regression for multi-class classification. In machine learning, logistic regression is widely used for applications such as disease prediction, spam detection, and fraud detection. Logistic regression demonstrated exemplary performance in our study, achieving an accuracy of 82% in predicting DENV infection and fatal cases across all provinces in Indonesia. Previous studies used logistic regression to classify dengue severity based on hematological markers, achieving high accuracy [32,33,34].

Logistic regression has also been applied to predict COVID-19 severity and mortality risk using patient data (e.g., age, comorbidities, blood markers) [35,36,37,38]. Logistic regression, a supervised learning classification algorithm, can be utilized for patient risk stratification to support tailored clinical decision-making. It can help measure disease probability, assess disease likelihood, and forecast its spread and fatality [39,40].

Random Forest (RF) is a powerful and widely used ensemble learning algorithm in machine learning. It is primarily used for classification and regression tasks by constructing multiple decision trees during training and combining their outputs for better accuracy and robustness. The key concepts of Random Forest include Ensemble Learning, Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregation), Feature Randomness, Out-of-Bag (OOB) Error, and Variable Importance. Ensemble Learning in Random Forest combines multiple decision trees to reduce overfitting and improve prediction accuracy. Additionally, Variable Importance helps identify the most influential features in making predictions. Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregation) involves training each tree on a random subset of the data, with predictions being averaged for regression tasks or determined by majority voting for classification tasks. Feature Randomness means that at each node, a random subset of features is used to split the data, enhancing model diversity and reducing correlation between trees. An out-of-bag (OOB) error occurs because each tree is trained on a different bootstrap sample, allowing the unused data to estimate the model’s accuracy. Variable Importance in Random Forest refers to the feature importance scores it provides, helping to identify the most influential variables in making predictions. RF model effectively captured the dynamic nature of an infectious disease epidemic and achieved high prediction [41,42,43]. In our study, the accuracy of the Decision Tree model was 78%, indicating a good prediction performance.

Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a robust supervised learning algorithm for classification, regression, and outlier detection. It is particularly effective for high-dimensional datasets and complex decision boundaries. In comparison with the Decision Tree model and Logistic Regression, the accuracy of SVM in this study was higher, reaching 83%. SVM identifies the optimal decision boundary (hyperplane) that best separates different classes in the dataset while maximizing the margin between the hyperplane and the nearest data points, improving generalization. Additionally, SVM can handle non-linearly separable data using kernel functions (e.g., linear, polynomial, radial basis function (RBF)) to transform data into higher dimensions where a linear separation becomes possible. It also balances the trade-off between achieving perfect separation and allowing some misclassifications for better generalization. SVMs have been used successfully for disease risk prediction [44] and, particularly, they have been successfully applied to type 1 diabetes (heritability is high ~90%) [45].

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), a highly efficient and robust ensemble learning algorithm based on gradient boosting, was developed and evaluated in this work. The need for additional validation is guided by the annual stability of feature importance. Feature importance is assessed on a yearly basis to determine whether the model’s behavior remains consistent over time. If similar importance patterns persist for three consecutive years, further validation may be considered unnecessary. Conversely, if notable changes occur, the model should be rerun and revalidated. The results show that feature importance follows a consistent pattern across three consecutive years, indicating stable model performance and reducing the immediate requirement for further validation.

XGBoost is widely used in machine learning competitions and real-world applications due to its speed, accuracy, and scalability. Among all the models developed in this study, XGBoost achieved the highest accuracy, reaching 85%. XGBoost outperforms many traditional machine learning models due to its efficiency, accuracy, and scalability [46,47,48]. This is because it uses gradient boosting, where weak learners (decision trees) are built sequentially, with each new tree correcting the errors of the previous ones. This iterative learning process reduces bias, unlike standard decision trees or random forests. It enhances predictive accuracy [49,50].

Additionally, XGBoost applies L1 (Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) regularization, reducing overfitting and improving generalization [51]. It also prunes trees using a minimum loss reduction threshold, preventing unnecessary splits and balancing bias and variance [52]. XGBoost is capable of automatically handling missing values and builds trees in parallel, making it significantly faster than Gradient Boosting Machines (GBMs) and Random Forests [53]. It also provides feature importance scores, helping to identify the most significant variables in prediction. Furthermore, XGBoost has built-in cross-validation and hyperparameter tuning, optimizing model performance efficiently. Based on previous research (COVID-19), the XGBoost method represents the most robust approach for the symptoms, initial vital signs, and clinical conditions. Findings show that XGBoost helps generate models capable of identifying high-risk patients earlier, allowing for better-targeted medical interventions and resource management [54].

Model evaluation in this study was conducted using internal validation. Although the data were derived from a single year (2024), the dataset was partitioned into independent training and testing subsets, and model performance was assessed on data that were not used during training. This strategy provides an estimate of the model’s ability to generalize within the same temporal context; however, it does not constitute external validation. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as evidence of promising predictive capability rather than definitive proof of generalizability across different time periods or settings. It should be evaluated using data from future years as well. Moreover, the model can be retrained as additional data becomes available; this retraining will help it capture evolving trends, reduce bias from older datasets, and improve its overall accuracy.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the use of single-year data restricts the model’s capacity to capture interannual variability driven by climatic fluctuations, mosquito population dynamics, and changes in population mobility. Second, although key epidemiological and case-count variables were included, other important determinants of dengue transmission such as detailed climatic indicators, entomological measures of vector density, and human behavioral or mobility factors were not incorporated due to data availability constraints. Third, the absence of external validation using data from other years or independent sources limits the immediate applicability of the model beyond the study period.

Despite these limitations, this study demonstrates the potential value of machine learning-based risk prediction models for dengue surveillance in Indonesia. By identifying high-risk provinces and periods of increased transmission, the proposed framework can support more targeted public health interventions, more efficient allocation of resources, and improved outbreak preparedness. With further validation and refinement, such models could become an important component of data-driven decision-making for dengue control at both national and subnational levels.

Dengue transmission is shaped by interactions among vector, host, environmental, and mobility factors [55,56]. Therefore, the spatial and temporal patterns observed in this study likely reflect shared underlying drivers across provinces rather than direct transmission. Aedes mosquito abundance depends on local environmental and urban conditions [57,58], while human mobility can synchronize outbreaks across regions without implying local spread [59]. Climatic factors such as temperature, rainfall, and humidity further influence dengue dynamics, often with delayed and nonlinear effects [60,61]. Because these variables were not explicitly included, interprovincial associations should be interpreted with caution.

Indonesia’s national surveillance system contains several demographic and health system variables, including population size and density, numbers of hospitals and community health centers (puskesmas), hospital bed-to-population and physician-to-population ratios, and levels of urbanization. Although these variables were not included in the current analysis, they represent valuable information that could be incorporated in future studies to improve model performance, enhance interpretability, and better capture differences in population structure and healthcare capacity across provinces.

This study was based on annual dengue incidence data from a single year, which provides a broad overview of national-level patterns but limits the ability to capture interannual variability. Future research should therefore validate the proposed framework using multi-year datasets and across different geographic or administrative contexts. Integrating real-time surveillance data with climatic variables, entomological indicators, and human mobility metrics is expected to further strengthen predictive accuracy and model robustness. Periodic retraining of the model as new data become available would also allow it to adapt to evolving transmission patterns and reduce bias associated with outdated information.

Extending the framework to include vector ecology, environmental conditions, and mobility data [62] will not only improve predictive performance but also enhance the mechanistic understanding of dengue transmission and the interpretability of observed spatial and temporal patterns. Effective dengue surveillance is essential for improving the accuracy of machine learning-based predictions of dengue incidence and mortality. Ultimately, such predictive models can inform public health policy by supporting infection prevention strategies, strengthening health system resilience, optimizing vaccination and treatment planning, minimizing economic disruption, and improving preparedness for future epidemics and pandemics.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that among the evaluated machine learning approaches, XGBoost achieved the highest predictive performance for dengue case, indicating its strong potential as a core model for data-driven dengue surveillance. The results suggest that XGBoost provides a strong methodological foundation for future dengue prediction studies and can serve as a benchmark against which more complex or biologically enriched models may be compared. The spatial and interprovincial patterns identified through clustering and correlation analyses represent statistical associations rather than evidence of direct transmission pathways. Dengue transmission is governed by intricate interactions between host immunity, mosquito vector ecology, environmental and climatic factors, and human mobility, none of which were explicitly incorporated in the current modeling framework. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted as reflecting data-driven pattern recognition rather than causal mechanisms of disease spread. Overall, this study positions XGBoost as a highly promising core algorithm for dengue prediction. By demonstrating its comparative advantage over other machine learning models, this work establishes a critical first step toward developing more comprehensive, interpretable, and operationally useful dengue early-warning systems that can support timely interventions and evidence-based public health decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.E.D., A.M.H. and A.S.; methodology, A.M.H., V.C. and J.F.; software, A.M.H., V.C. and J.F.; validation, B.E.D., A.T.F. and A.S.; formal analysis, V.C., J.F. and A.M.H.; investigation, B.E.D., A.S. and D.A.; resources, A.T.F., A.M.H., V.C., J.F., A.S. and D.A.; data curation, A.T.F., M.F.E., A.S. and D.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.E.D., M.F.E., A.M.H., A.A.A.K. and A.T.F.; writing—review and editing, B.E.D., M.F.E., A.M.H. and A.A.A.K.; visualization, A.M.H. and M.F.E.; supervision, B.E.D. and A.S.; project administration, A.A.A.K. and A.T.F.; funding acquisition, B.E.D. and A.A.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by part of the collaborative activities under the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) No. 52/AOI/FK/UI/2024 established between Universitas Indonesia and Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information, and in part by a grant from the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP), Grant No. PRJ-13/LPDP/LPDP.4/2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee of Research Ethical Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia (No. KET-1847/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are derived from the National Dengue Control Programme, Ministry of Health Indonesia, and are publicly available.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the administrative and technical support provided by Universitas Indonesia and KISTI, which was instrumental in the successful completion of this study. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used Python for the purposes of data visualization. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DENV | Dengue Virus |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DHF | Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever |

| CFR | Case Fatality Rates |

| EDA | Exploratory Data Analysis |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| RF | Random Forest |

References

- Harapan, H.; Michie, A.; Mudatsir, M.; Sasmono, R.T.; Imrie, A. Epidemiology of dengue hemorrhagic fever in Indonesia: Analysis of five decades data from the National Disease Surveillance. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmono, R.T.; Taurel, A.-F.; Prayitno, A.; Sitompul, H.; Yohan, B.; Hayati, R.F.; Bouckenooghe, A.; Hadinegoro, S.R.; Nealon, J. Dengue virus serotype distribution based on serological evidence in pediatric urban population in Indonesia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, B.E.; Nainggolan, L.; Sudiro, T.M.; Chenderawasi, S.; Goentoro, P.L.; Sjatha, F. Circulation of Various Dengue Serotypes in a Community-Based Study in Jakarta, Indonesia. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 74, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryati, A.; Wrahatnala, B.J.; Yohan, B.; Fanny, M.; Hakim, F.K.N.; Sunari, E.P.; Zuroidah, N.; Wardhani, P.; Santoso, M.S.; Husada, D.; et al. Dengue virus serotype 4 is responsible for the outbreak of dengue in East Java City of Jember, Indonesia. Viruses 2020, 12, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, R.; Ikawati, D.; Nugraha, A.A.; Agustiningsih, M.; Maha, S. Distribution of Dengue Genotype in Indonesia. 2016. Volume 7. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Dlq3Z4iqxH-ICeGhlNOfYl2hD4l5ki38/view (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- OhAinle, M.; Balmaseda, A.; Macalalad, A.R.; Tellez, Y.; Zody, M.C.; Saborío, S.; Nuñez, A.; Lennon, N.J.; Birren, B.W.; Gordon, A.; et al. Dynamics of Dengue Disease Severity Determined by the Interplay Between Viral Genetics and Serotype-Specific Immunity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 114ra128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, C.-F.; Lee, K.-S.; Thein, T.-L.; Tan, L.-K.; Gan, V.C.; Wong, J.G.X.; Lye, D.C.; Ng, L.-C.; Leo, Y.-S. Dengue Serotype-Specific Differences in Clinical Manifestation, Laboratory Parameters and Risk of Severe Disease in Adults, Singapore. Am. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 92, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente, C.R.; Herbinger, K.-H.; Fröschl, G.; Malta Romano, C.; de Souza Areias Cabidelle, A.; Cerutti Junior, C. Serotype influences on dengue severity: A cross-sectional study on 485 confirmed dengue cases in Vitória, Brazil. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. Comprehensive Guidelines for Prevention and Control of Dengue and Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever Revised and Expanded Edition; SEARO Publications: New Delhi, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Moraga, P. Assessing dengue forecasting methods: A comparative study of statistical models and machine learning techniques in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Trop. Med. Health 2025, 53, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningrum, D.N.A.; Li, Y.-C.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Muhtar, M.S.; Suhito, H.P. Artificial Intelligence Approach for Severe Dengue Early Warning System. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2023, 310, 881–885. [Google Scholar]

- Jaya, I.G.N.M.; Andriyana, Y.; Tantular, B.; Pangastuti, S.S.; Kristiani, F. Spatiotemporal Dengue Forecasting for Sustainable Public Health in Bandung, Indonesia: A Comparative Study of Classical, Machine Learning, and Bayesian Models. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavari Nejad, F.; Varathan, K.D. Identification of significant climatic risk factors and machine learning models in dengue outbreak prediction. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Moraga, P. Forecasting dengue across Brazil with LSTM neural networks and SHAP-driven lagged climate and spatial effects. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silitonga, P.; Bustamam, A.; Muradi, H.; Mangunwardoyo, W.; Dewi, B.E. Comparison of Dengue Predictive Models Developed Using Artificial Neural Network and Discriminant Analysis with Small Dataset. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silitonga, P.; Dewi, B.E.; Bustamam, A.; Al-Ash, H.S. Evaluation of Dengue Model Performances Developed Using Artificial Neural Network and Random Forest Classifiers. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 179, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, B.E.; Wijayanti, S.P.M.; Dewi, B.E.; Anugrha, H.W.; Goentoro, P.L.; Sudiro, M. Efficacy of NS1 Antigen Detection for Early Dengue Infection Diagnosis in Indonesia. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2020, 51, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Putra, T.I.Z.M.; Suprapto, S.; Bukhori, A.F. Model Klasifikasi Berbasis Multiclass Classification dengan Kombinasi Indobert Embedding dan Long Short-Term Memory untuk Tweet Berbahasa Indonesia. J. Ilmu Siber Dan Teknol. Digit. 2022, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, J.H.; Olshen, R.A.; Stone, C.J. Classification and Regression Trees, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokach, L.; Maimon, O. Data Mining with Decision Trees. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ZsOG_22xGHCqTzGhnNknw0FYM1xWAwEw/view (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singgalen, Y.A. Hotel Guest Length of Stay Prediction Using Random Forest Regressor. J. Inf. Syst. Inform. 2024, 6, 3016–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Jin, J.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, Z. Building a cancer risk and survival prediction model based on social determinants of health combined with machine learning: A NHANES 1999 to 2018 retrospective cohort study. Medicine 2025, 104, e41370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V.; Saitta, L. Support-Vector Networks Editor; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Hingham, MA, USA, 1995; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, J. Probabilistic Outputs for Support Vector Machines and Comparisons to Regularized Likelihood Methods. Adv. Large Margin Classif. 2000, 10, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-W.; Chang, C.-C.; Lin, C.-J. A Practical Guide to Support Vector Classification. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ARexDOONDMzUzMnSRtd12uF4m7ueg2x7/view (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Statistics Indonesia (BPS). Population by Province (Thousand People), 2023–2024. 2024. Available online: https://sumsel.bps.go.id/id/statistics-table/2/NTczIzI=/jumlah-penduduk-menurut-provinsi.html (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Ebi, K.L.; Nealon, J. Dengue in a changing climate. Environ. Res. 2016, 151, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaga, K.P.; Yang, M.-S. Unsupervised K-Means Clustering Algorithm. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 80716–80727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, E. Geospatial Analysis Framework. Brain 2010, 1, 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Al Meslamani, A.Z.; Sobrino, I.; de la Fuente, J. Machine learning in infectious diseases: Potential applications and limitations. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2362869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potts, J.A.; Gibbons, R.V.; Rothman, A.L.; Srikiatkhachorn, A.; Thomas, S.J.; Supradish, P.; Lemon, S.C.; Libraty, D.H.; Green, S.; Kalayanarooj, S. Prediction of Dengue Disease Severity among Pediatric Thai Patients Using Early Clinical Laboratory Indicators. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010, 4, e769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srisuphanunt, M.; Puttaruk, P.; Kooltheat, N.; Katzenmeier, G.; Wilairatana, P. Prognostic Indicators for the Early Prediction of Severe Dengue Infection: A Retrospective Study in a University Hospital in Thailand. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, B.R.; Mishra, A.; Aryal, S.; Chhusyabaga, M.; Bhujel, R. Association of Hematological and Biochemical Parameters with Serological Markers of Acute Dengue Infection during the 2022 Dengue Outbreak in Nepal. J. Trop. Med. 2023, 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Du, H.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, Y.; Kang, W.; et al. Early prediction and identification for severe patients during the pandemic of COVID-19: A severe COVID-19 risk model constructed by multivariate logistic regression analysis. J. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 020510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Qi, Y.; Yao, Y.; Yu, Y. A predictive model for disease severity among COVID-19 elderly patients based on IgG subtypes and machine learning. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1286380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Shaktawat, A.; Tak, A.; Patel, B.; Shukla, J.; Singhal, S.; Gupta, K.; Gupta, J.; Kakkar, S.; Dube, A. Logistic regression analysis to predict mortality risk in COVID-19 patients from routine hematologic parameters. Ibnosina J. Med. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 12, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nopour, R.; Shanbehzadeh, M.; Kazemi-Arpanahi, H. Using logistic regression to develop a diagnostic model for COVID-19. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeshal, A.M.; Almazrouee, A.I.; Alenizi, M.R.; Alhajeri, S.N. Forecasting the Spread of COVID-19 in Kuwait Using Compartmental and Logistic Regression Models. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Zhou, M.; Yang, D.; Ling, Y.; Liu, K.; Bai, T.; Cheng, Z.; Li, J. Application of ordinal logistic regression analysis to identify the determinants of illness severity of COVID-19 in China. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020, 148, e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Liu, W.; Ai, J.; He, M.; Wu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Shen, W.; Bao, C. Forecasting incidence of infectious diarrhea using random forest in Jiangsu Province, China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geeitha, S.; Karthikeyan, P.; Aravinth, S.; Nachiappan, P.; Jagadeesh, S. Contagious Disease Prediction using Random Forest Algorithm Interpolated with Fuzzy Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Data Communication Systems (ICSCDS), Erode, India, 23–25 March 2023; pp. 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Deng, X.-M.; Fu, F.-M.; Wang, J.-M.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Luo, Y.-X.; Zhang, S.-Y. Using random forest and biomarkers for differentiating COVID-19 and Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, K.; Qu, H.-Q.; Zhang, H.; Bradfield, J.; Kim, C.; Frackleton, E.; Hou, C.; Glessner, J.T.; Chiavacci, R.; et al. From Disease Association to Risk Assessment: An Optimistic View from Genome-Wide Association Studies on Type 1 Diabetes. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittag, F.; Büchel, F.; Saad, M.; Jahn, A.; Schulte, C.; Bochdanovits, Z.; Simón-Sánchez, J.; Nalls, M.A.; Keller, M.; Hernandez, D.G.; et al. Use of support vector machines for disease risk prediction in genome-wide association studies: Concerns and opportunities. Hum. Mutat. 2012, 33, 1708–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. Comparison and analysis of accuracy of traditional random forest machine learning model and XGBoost model on music emotion classification dataset. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Machine Learning and Computer Application, Hangzhou, China, 27–29 October 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.; Yang, J.-H.; Byun, Y.-C. Optimized XGBoost modeling for accurate battery capacity degradation prediction. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 102786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, F.; Troussas, C.; Krouska, A.; Sgouropoulou, C.; Voyiatzis, I. XGBoost and Deep Neural Network Comparison: The Case of Teams’ Performance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Bukov, M.; Wang, C.-H.; Day, A.G.R.; Richardson, C.; Fisher, C.K.; Schwab, D.J. A high-bias, low-variance introduction to Machine Learning for physicists. Phys. Rep. 2019, 810, 1–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.; Falcão, B.; Mohamed, M.A.; Annuk, A.; Marinho, M. Employing machine learning for advanced gap imputation in solar power generation databases. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumachenko, D.; Dudkina, T.; Chumachenko, T.; Morita, P.P. Epidemiological Implications of War: Machine Learning Estimations of the Russian Invasion’s Effect on Italy’s COVID-19 Dynamics. Computation 2023, 11, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yu, Z.; Qu, Y.; Xu, J.; Cao, Y. Application of the XGBoost Machine Learning Method in PM2.5 Prediction: A Case Study of Shanghai. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.A.; Abduljabbar, Z.H.; Tahir, H.A.; Sallow, A.B.; Almufti, S.M. eXtreme Gradient Boosting Algorithm with Machine Learning: A Review. Acad. J. Nawroz Univ. 2023, 12, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zuo, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, X.; Xie, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, C. Clinical and Laboratory Predictors of In-hospital Mortality in Patients With Coronavirus Disease-2019: A Cohort Study in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2079–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubler, D.J. Dengue, Urbanization and Globalization: The Unholy Trinity of the 21(st) Century. Trop. Med. Health 2011, 39, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, O.J.; Gething, P.W.; Bhatt, S.; Messina, J.P.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hoen, A.G.; Moyes, C.L.; Farlow, A.W.; Scott, T.W.; Hay, S.I. Refining the global spatial limits of dengue virus transmission by evidence-based consensus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, S.T.; Morrison, A.C.; Vazquez-Prokopec, G.M.; Paz Soldan, V.; Kochel, T.J.; Kitron, U.; Elder, J.P.; Scott, T.W. The Role of Human Movement in the Transmission of Vector-Borne Pathogens. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, e481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesolowski, A.; Qureshi, T.; Boni, M.F.; Sundsøy, P.R.; Johansson, M.A.; Rasheed, S.B.; Engø-Monsen, K.; Buckee, C.O. Impact of human mobility on the emergence of dengue epidemics in Pakistan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 11887–11892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, M.U.G.; Sinka, M.E.; Duda, K.A.; Mylne, A.Q.N.; Shearer, F.M.; Barker, C.M.; Moore, C.G.; Carvalho, R.G.; Coelho, G.E.; Van Bortel, W.; et al. The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus. Elife 2015, 4, e08347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, C.W.; Comrie, A.C.; Ernst, K. Climate and dengue transmission: Evidence and implications. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, R.; Gasparrini, A.; Van Meerbeeck, C.J.; Lippi, C.A.; Mahon, R.; Trotman, A.R.; Rollock, L.; Hinds, A.Q.J.; Ryan, S.J.; Stewart-Ibarra, A.M. Nonlinear and delayed impacts of climate on dengue risk in Barbados: A modelling study. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul Rahman, A.A.; Rajasekaran, G.; Ramalingam, R.; Meero, A.; Seetharaman, D. From Data to Diagnosis: Machine Learning Revolutionizes Epidemiological Predictions. Information 2024, 15, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.