Featured Application

The integrated energy–exergy–exergoeconomic framework developed in this study offers a transferable and field-validated methodology for the rigorous assessment of large-scale ammonia refrigeration systems. The approach enables precise identification of dominant irreversibility sources and cost-driving components, providing a robust scientific basis for optimization and retrofitting strategies in existing industrial cold storage applications.

Abstract

Improving the thermodynamic and economic performance of industrial refrigeration systems is essential for reducing energy consumption and enhancing cold chain sustainability. This study presents an integrated energy, exergy, and exergoeconomic assessment of a full-scale two-stage ammonia (R717) vapor compression refrigeration system operating under real industrial conditions in Türkiye. Experimental data from 33 measurement points were used to perform component-level thermodynamic balances under steady-state conditions. The results showed that the evaporative condenser exhibited the highest heat transfer rate (426.7 kW), while the overall First Law efficiency of the system was 63.71%. Exergy analysis revealed that heat exchangers are the dominant sources of irreversibility (>45%), followed by circulation pumps with a notably low Second Law efficiency of 11.56%. The exergoeconomic assessment identified the circulation pumps as the components with the highest loss-to-cost ratio (2.45 W/USD). An uncertainty analysis confirmed that the relative ranking of system components remained robust within the measurement uncertainty bounds. The findings indicate that, although the existing NH3 configuration provides adequate performance, significant improvements can be achieved by prioritizing pump optimization, maintaining higher compressor loading, and implementing advanced variable-speed fan control strategies.

1. Introduction

The growing energy demand in industrial facilities, the depletion of fossil resources, and the increasing severity of global climate change have made energy efficiency one of the most critical research topics of recent decades. Refrigeration and air-conditioning systems, which are extensively used in food processing, agricultural logistics, chemical industries, and healthcare, account for a significant share of industrial energy consumption. Therefore, improving the thermodynamic performance of these systems is essential for both economic competitiveness and environmental sustainability [1,2,3].

Because agricultural products are generally harvested seasonally but consumed throughout the year, the establishment of a reliable cold chain infrastructure has become indispensable. By maintaining controlled temperature and relative humidity conditions, the cold chain suppresses microbial activity and slows chemical degradation processes, thereby reducing spoilage and foodborne risks [4,5,6]. At the same time, it extends the shelf life of highly perishable products such as apples, fish, and fresh fruits and vegetables, contributing to a reduction in food waste and associated economic losses [5,7,8]. In this context, integrated cold storage facilities represent a fundamental technological infrastructure for preserving product quality and minimizing post-harvest losses.

Vapor compression refrigeration (VCR) systems continue to be the most widely adopted solutions in industrial applications due to their robust design and operational simplicity. Ammonia (R717), a natural refrigerant, offers high energy efficiency owing to its large latent heat of vaporization and favorable heat transfer characteristics, enabling reduced compressor power consumption and smaller equipment sizes [9,10]. In addition, its zero ozone depletion potential (ODP) and negligible global warming potential (GWP) make ammonia environmentally superior to hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) and hydrofluoroolefin (HFO) alternatives [11,12,13]. Nevertheless, single-stage ammonia systems may suffer from efficiency degradation and excessively high discharge temperatures at low evaporating pressures, rendering two-stage compression cycles a more suitable solution for medium- and low-temperature applications [1,2].

Extensive research has been conducted on two-stage and cascade refrigeration systems using different working fluids and cycle configurations from both energy and exergy perspectives. Previous studies have examined the low-temperature performance of CO2- and HFC-based refrigerant pairs [3,14,15], the extended operating range of ammonia–water systems [16], and the second-law performance of various refrigerants [17,18,19]. Investigations focusing on cycle modifications have demonstrated that ejector-assisted configurations, vapor injection techniques, and internal heat exchangers can lead to notable improvements in the coefficient of performance (COP) and exergy efficiency [20,21,22,23].

Optimization-oriented studies have highlighted the decisive influence of intermediate pressure selection, condenser temperature, and intercooler performance on overall system efficiency [24,25,26,27,28]. While theoretical and simulation-based analyses often identify compressors as the primary source of irreversibility, field data obtained from industrial facilities indicate that, particularly under partial-load conditions, heat exchangers and auxiliary components may play a more dominant role in system inefficiencies.

In recent years, it has become increasingly evident that energy analysis alone is insufficient for a comprehensive evaluation of industrial refrigeration systems. Consequently, exergy-based approaches and, more recently, exergoeconomic or 4E (energy–exergy–economic–environmental) analyses have gained widespread acceptance. The combined use of energy and exergy analyses enables the identification of components with the highest irreversibility levels—most notably evaporators and condensers [29,30,31,32,33]—whereas exergoeconomic methods allow the determination of components with the greatest improvement potential based on unit exergy costs [34,35,36,37,38].

Numerous studies have reported that heat exchangers account for approximately 20–40% of the total exergy destruction within refrigeration and heat pump systems [39,40,41,42]. Moreover, advanced exergy analyses applied to heat pump systems have shown that the majority of avoidable exergy destruction occurs in the evaporator and condenser, emphasizing the importance of these components for performance enhancement [43].

Recent studies have increasingly focused on hybrid and advanced thermal management concepts aimed at mitigating irreversibilities in heat exchangers and improving overall system efficiency. Approaches such as radiation thermal-diode tank (RTDT)–assisted cooling systems and dual-function solar–thermal–energy-storage–integrated heat pump configurations have been reported as promising solutions for enhancing thermal regulation and reducing exergy destruction. Although such architectures are beyond the scope of the present study, the identification of heat exchangers as dominant sources of irreversibility under real industrial operating conditions provides a quantitative basis for evaluating and prioritizing these advanced concepts in future refrigeration system designs.

Despite the breadth of existing literature, comprehensive field studies addressing full-scale two-stage R717 Vapor compression refrigeration systems operating under real industrial loads remain limited. In particular, the relationship between actual cooling demands, component-level exergy destruction, and feasible operational performance improvements has not been sufficiently explored. To address this gap, the present study evaluates the energy, exergy, and exergoeconomic performance of a full-scale two-stage ammonia (R717) refrigeration system installed in an integrated cold storage facility in Kütahya, Türkiye, using real operational data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Two-Stage Ammonia Refrigeration System

As the cooling load increases, the required compression ratio of the compressors also rises, which in turn leads to higher discharge temperatures. Elevated compression ratios adversely affect both the energy efficiency and operational reliability of refrigeration compressors, particularly in low-temperature applications. For this reason, refrigeration systems operating based on multi-stage compression principles have become indispensable in industrial applications, as they enable more balanced and efficient operation under demanding thermal conditions.

In the integrated cold storage facility investigated in this study, a two-stage vapor compression refrigeration cycle was implemented to supply cold rooms operating at different temperature levels from a single centralized system. While single-stage refrigeration cycles can adequately serve cold rooms operating at relatively higher temperatures, a staged compression configuration is required for frozen storage rooms operated at −18 °C. The use of a two-stage cycle allows low-temperature requirements to be met while maintaining compressors within more favorable operating ranges.

To facilitate a clear understanding of the system configuration and refrigerant circulation under industrial operating conditions, the overall working principle of the two-stage ammonia refrigeration system is briefly outlined below. This description focuses on the refrigerant flow paths, the interaction between the low- and high-pressure stages, and the role of the main components, without delving into theoretical cycle analysis or idealized assumptions.

In the two-stage refrigeration cycle, ammonia (R717) is compressed to the condenser pressure by parallel-operating high-pressure compressors. The refrigerant vapor leaving the compressors in a superheated state is directed to the evaporative condenser, where heat is rejected to the ambient air through combined air and water cooling. At the condenser outlet, the refrigerant exits in either liquid or saturated liquid–vapor mixture form and is subsequently routed to the liquid receiver to ensure stable system operation.

The refrigerant leaving the liquid receiver is transferred to the high-pressure receiver through pressure- and temperature-regulating valves. Within the high-pressure receiver, the refrigerant exists at saturation conditions as a liquid–vapor mixture, where the vapor phase supplies the high-pressure compressors. A portion of the refrigerant is expanded through pressure–temperature-regulating valves and directed to the low-pressure receiver, while the liquid phase is conveyed to the ammonia circulation pumps. These pumps pressurize the liquid refrigerant and deliver it to the evaporators.

At the evaporator inlet, the mass flow rate, pressure, and temperature of the refrigerant are regulated using throttling devices, pressure–temperature control valves, and solenoid valves. Within the evaporators, the refrigerant absorbs heat from the refrigerated spaces through fan-assisted forced convection, exiting the evaporators in either vapor or liquid–vapor mixture form. The refrigerant then passes through pressure and temperature regulators and solenoid valves before returning to the receivers at the corresponding operating conditions.

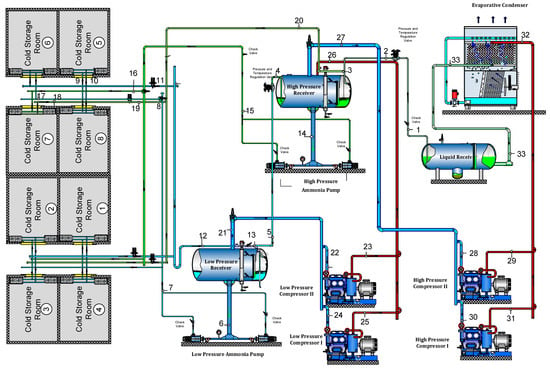

The low-pressure receiver operates between the high-pressure receiver and the low-pressure compressors. The vapor phase of the refrigerant returning from the receivers and evaporators supplies the low-pressure compressors, while the liquid phase is directed to the circulation pumps and subsequently delivered to the low-temperature evaporators. This configuration enables stable refrigerant distribution to evaporators operating at different temperature levels and ensures balanced operation between the stages of the refrigeration cycle. The overall refrigerant flow arrangement, operating pressure zones, and main system components are illustrated in Figure 1, while the corresponding components, specifications, and functional descriptions are summarized in Table 1. In Figure 1, the numbered labels indicate the inlet and outlet points of each system component as well as the locations of temperature and pressure measurement points. The corresponding point numbers listed in Table 1 represent the inlet (first number) and outlet (second number) of each component, and the refrigerant flow directions are indicated by arrows in the schematic. In addition, a schematic representation of the two-stage NH3 (R717) vapor compression refrigeration system of the integrated cold storage facility and photographs of the cycle components are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S1 and S2).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental two-stage vapor compression ammonia (R717) refrigeration system.

Table 1.

Main components and functions of the experimental two-stage refrigeration system.

2.2. Experimental Instrumentation and Data Acquisition

Temperature and pressure variations throughout the two-stage ammonia refrigeration cycle were monitored using ALMEMO-series sensors connected to a central ALMEMO 3290 multi-channel data logger (Ahlborn Mess- und Regelungstechnik GmbH, Holzkirchen, Germany). Liquid refrigerant mass flow rates were measured non-intrusively on the liquid lines using clamp-on ultrasonic flowmeters (KATflow 110, Katronic Technologies Ltd., Coventry, United Kingdom), while the electrical power consumption of all compressors and circulation pumps was recorded using three-phase digital power analyzers (Dongguan Mengtai Instrument Co., Ltd., Dongguan, China). The specifications, measurement ranges, accuracies, and the number of measurement points for each parameter are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Measurement parameters, instruments used, and uncertainty values.

All measurement signals were continuously transmitted to the facility’s proprietary PLC-based automation system. Information regarding the PLC manufacturer and software is not reported in accordance with the facility’s institutional confidentiality requirements. The acquired data were subsequently transferred to a personal computer via an RS232C communication interface for storage and post-processing. Data acquisition was performed at 10 s sampling intervals, allowing short-term fluctuations to be captured and enabling reliable identification of stable operating conditions.

Although high-frequency sampling was employed, the thermodynamic evaluation presented in this study is based on steady state operating conditions. Steady state periods were identified by monitoring the temporal evolution of key variables such as temperatures, pressures, mass flow rates, and electrical power consumption and selecting time intervals during which these parameters exhibited negligible variation around their mean values. The 10 s sampling interval was therefore used to verify steady-state stability and to filter out transient disturbances, rather than to conduct a fully dynamic analysis.

The refrigeration facility has been monitored over multiple years within the scope of the authors’ doctoral research; however, the present study focuses exclusively on a continuous one-month operating period corresponding to the storage duration of the investigated products. All experimental data used in this paper were collected during this period, ensuring that the dataset fully represents real industrial operating conditions.

Following data acquisition, raw measurements were screened to exclude transient regimes such as start-up and load-change events. Subsequently, time-averaged values were calculated for each measured parameter during steady-state intervals. These averaged values were then used as inputs for the energy, exergy, and exergoeconomic analyses. All calculations were performed using calibrated sensor data and standard thermodynamic relations, ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of the obtained results.

2.3. Uncertainty Analysis

A measurement uncertainty analysis was performed to evaluate the reliability of the experimental results. The uncertainties associated with each measurement device, as provided by the manufacturers, were used to calculate the combined uncertainty of derived quantities using a standard uncertainty propagation approach.

For a general result dependent on variables , the combined uncertainty is expressed as:

Based on repeated measurements and instrument specifications:

- The combined uncertainty of heat transfer rates was ±3.1%.

- The overall uncertainty of exergy efficiency calculations was ±4.5%.

- The highest contribution to uncertainty originated from mass flow measurements, influenced by ultrasonic sensor alignment and pipe length effects.

These values confirm that the experimental dataset exhibits high reliability for subsequent energy, exergy, and exergoeconomic analysis.

2.4. Operating Conditions of the Cold Rooms

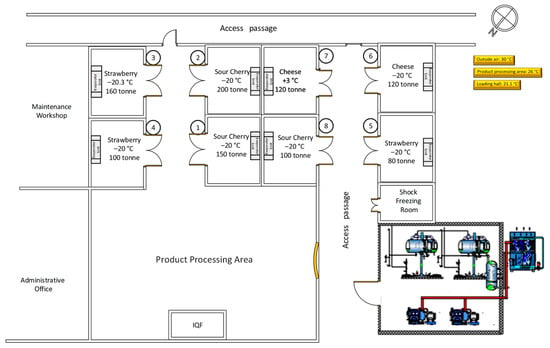

The experimental study was carried out under the actual operating conditions of an industrial cold storage facility. The plant consists of eight cold rooms, of which seven are operated under a frozen storage regime with a setpoint temperature of −18 °C, while one room is operated as fresh storage with a setpoint temperature of +3 °C. During the experimental period, the average outdoor ambient temperature was recorded as 30 °C. The temperatures of the product processing hall and the loading hall were maintained at 26 °C and 21.1 °C, respectively.

The layout of the facility, including the arrangement of the cold rooms, the types of stored products (e.g., strawberries, sour cherries, and cheese), and the corresponding storage capacities, is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Layout plan of the integrated cold storage facility showing the arrangement of cold rooms, product allocations, storage capacities, and operational temperature zones.

Throughout the experimental campaign, the cold rooms were operated under stable thermal conditions close to their respective setpoint temperatures. The average relative humidity levels were approximately 90% in the frozen storage rooms and 65% in the fresh storage room, in accordance with standard storage practices for the product categories considered.

2.5. Energy, Exergy and Exergoeconomic Analysis Framework

The thermodynamic performance of each system component was evaluated using component-wise energy and exergy balances under steady-flow, open-system conditions. Mass, heat, and work interactions across the control volumes of the individual components were taken into account. The energy, exergy, and exergoeconomic analyses were performed based on the following assumptions:

- The system operates under steady-state and steady-flow conditions.

- Changes in kinetic and potential energy are neglected.

- Pressure drops in the connecting pipelines are neglected, whereas component-level pressure losses are implicitly accounted for through the measured inlet and outlet thermodynamic states.

- Heat losses to the surroundings are neglected, except for those intentionally occurring in heat exchangers.

- Thermophysical properties of ammonia (R717) are obtained from standard thermodynamic property databases.

2.5.1. Energy Analysis

In steady-flow open systems, the conservation of mass requires that the total mass flow rate entering the control volume must equal the total mass flow rate leaving it. This fundamental principle is expressed as [31]:

The total energy transfer through the system is determined by the specific flow energy (enthalpy () and the mass flow rate () [32]:

The general energy balance for a control volume operating under steady-flow conditions is derived from the First Law of Thermodynamics. Neglecting kinetic and potential energy changes, the energy balance accounts for heat transfer () work interaction () and enthalpy change () [31,32,33];

The thermal performance of the refrigeration system is evaluated based on the First Law of Thermodynamics. This performance is characterized by the First Law Efficiency (), also referred to as the Coefficient of Performance (COP). It is defined as the ratio of the useful cooling load extracted from the evaporators () to the total electrical work input to the compressors ()

2.5.2. Exergy Analysis

Exergy represents the maximum work potential of a system relative to its environment and is evaluated based on the Second Law of Thermodynamics. While energy is conserved, exergy is destroyed due to irreversibilities such as friction and heat transfer across finite temperature differences. For a steady-flow open system, the specific flow exergy () is calculated as [31,32,33]:

where and are the enthalpy and entropy at the restricted dead state ( = 0.97 bar, = 30 °C). The total exergy flow rate () is [32]:

The general exergy balance for any control volume can be written as

Or more specifically, accounting for heat and work interactions:

The Second Law efficiency () indicates how efficiently the exergy input is converted into the exergy product and is defined as:

The ratio of the exergy destruction in each component to the total exergy destruction of the cycle is called the relative irreversibility and is expressed as. The relative irreversibility () of each component is:

2.5.3. Exergoeconomic Formulation

The EXCEM (Exergy–Cost–Energy–Mass) method was employed to evaluate the economic impact of thermodynamic inefficiencies. This method integrates the Second Law analysis with economic factors to calculate the cost of exergy destruction. The general balance equations for exergy and cost for each system component are expressed as follows [34]:

Under steady-state operation, the accumulation terms are zero. The cost generation term () typically includes capital investment, operation, and maintenance costs. In this study, since the capital investment constitutes the dominant share of the total cost for industrial ammonia refrigeration plants, the analysis focuses on the initial capital cost (K). The component costs were derived from the actual facility purchase invoices and updated vendor quotations.

Within the EXCEM framework, the thermodynamic losses are categorized as energy loss () and exergy loss defined as [35,39]

To compare the economic impact of these losses relative to the component cost, two dimensionless ratios are defined: the Energy Loss Ratio () and the Exergy Loss Ratio ():

These ratios serve as key exergoeconomic indicators: a higher value indicates that a component has a high rate of exergy destruction relative to its capital investment, identifying it as a priority for thermodynamic and economic optimization. The complete set of energy, exergy, and efficiency equations applied to all system components is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Energy Balances, Exergy Balances, and First and Second Law Efficiency Equations for All System Components.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the thermodynamic performance of the two-stage ammonia (R717) vapor compression refrigeration system operating under real industrial conditions. The evaluation is based on integrated energy, exergy, and exergoeconomic analyses conducted using experimentally measured data. The results provide insight into the overall system balance, component-level efficiencies, and the thermodynamic significance of irreversibilities from both performance and economic perspectives.

3.1. Results of Exergy Analysis

The energy balance analysis indicates that the evaporative condenser is the dominant thermal component of the cycle, rejecting heat at a rate of 426.7 kW. In contrast, the total cooling capacity extracted by the evaporators was calculated as 158.93 kW. The marked difference between the rejected heat and useful cooling load is primarily associated with the substantial compressor power input required by the two-stage compression configuration. This behavior is consistent with previous studies, which identify the condenser as the principal heat interaction component in cascade and multi-stage refrigeration systems [40].

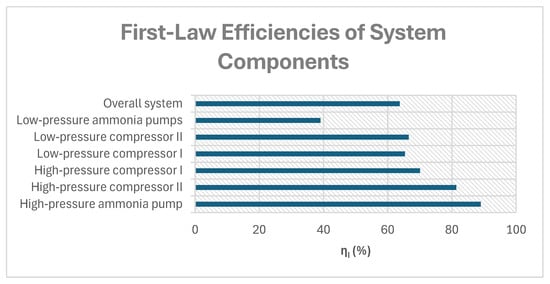

Component-level results further demonstrate the strong influence of operating load conditions on energy performance. For the high-pressure (HP) compressor group, increasing the load ratio from 33% to 66% led to a pronounced improvement in the First Law efficiency (η_I), which increased from 70.07% to 81.34%. In contrast, the low-pressure (LP) compressors operated close to full load throughout the measurement period and exhibited relatively stable efficiencies ranging between 65% and 67%.

The overall First Law efficiency of the refrigeration system was determined to be 63.71%. This value compares well with the efficiency level of approximately 66% reported by Cinti et al. [41] for optimized ammonia-based systems. The agreement supports the conclusion that, particularly in medium- and low-temperature industrial applications, a pure ammonia cycle can achieve competitive energy performance without the added complexity of cascade arrangements. The distribution of First Law efficiencies among the main system components is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

First Law Efficiencies of System Components.

Uncertainty Analysis of Energy and Exergy Results

To assess the reliability of the experimentally obtained energy, exergy, and exergoeconomic results, an uncertainty analysis was performed based on the measurement accuracies of the primary instruments and the error propagation methodology described in Section 2.3. The uncertainties associated with temperature, pressure, mass flow rate, and electrical power measurements were systematically propagated to the calculated thermodynamic performance parameters.

The uncertainty in the heat transfer rates of the evaporators and the evaporative condenser was estimated to be within ±3.1%, corresponding to an absolute variation of approximately ±5 kW for the dominant thermal components. This uncertainty level is consistent with those reported in similar large-scale industrial refrigeration studies and is considered acceptable for field-based experimental investigations.

For the exergy-based indicators, including exergy destruction rates and Second Law efficiencies, the combined measurement uncertainty was determined to lie within the range of ±4–5%. As a result, the overall Second Law efficiency of the system, calculated as 33.64%, is expected to vary within a narrow band of approximately ±1.5 percentage points. Importantly, this variation does not alter the relative distribution of exergy destruction among system components.

In particular, the ranking of the major contributors to total irreversibility, namely the evaporators, evaporative condenser, compressors, and circulation pumps—remains unchanged when the uncertainty margins are taken into account. Similarly, the identification of the pumping subsystem as the component group with the lowest Second Law efficiency and the highest exergoeconomic loss ratio is robust against the estimated uncertainty bounds.

Therefore, the uncertainty analysis confirms that the main conclusions drawn from the energy, exergy, and exergoeconomic evaluations are statistically and thermodynamically reliable, and that the observed performance trends and component rankings are not artifacts of measurement errors but reflect the intrinsic operational characteristics of the investigated industrial refrigeration system.

3.2. Exergy Analysis Results

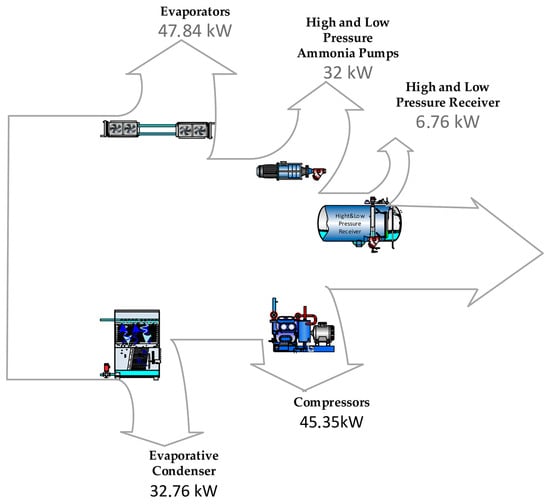

While energy analysis evaluates system performance based on the quantity of energy transferred, exergy analysis provides deeper insight into the quality of energy interactions by identifying the locations and magnitudes of thermodynamic irreversibilities within the system. In this study, a component-wise exergy analysis was conducted under steady-state operating conditions to determine the distribution of exergy destruction and the Second Law efficiencies of the main subsystems. The numerical results of the detailed balance equations are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1), while the overall distribution of exergy destruction across the system is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Exergy flow diagram illustrating the distribution of exergy destruction across the main system components.

As shown in Figure 4, the exergy analysis reveals that heat exchangers constitute the dominant sources of irreversibility in the investigated full-scale industrial refrigeration facility. In particular, the frozen storage evaporators account for the largest share of the total exergy destruction, corresponding to approximately 25.3% (41.86 kW) of the system-wide irreversibilities. This behavior is primarily attributed to heat transfer across finite temperature differences between the refrigerant and the cold room air, which is inherently associated with significant entropy generation under real operating conditions. The evaporative condenser represents the second-largest contributor, with an exergy destruction rate of 32.76 kW, corresponding to approximately 19.8% of the total irreversibility. The combined effect of air-side and water-side heat transfer processes, together with fan and pump power consumption, explains the elevated exergy losses observed in this component.

The compressor group, comprising both low-pressure (LP) and high-pressure (HP) compressors operating in parallel, constitutes the third major source of irreversibility. When evaluated collectively, the compressors are responsible for approximately 27.4% of the total exergy destruction in the system. Although compressors are often identified as the primary irreversibility source in idealized or simulation-based studies, the present results demonstrate that, under real industrial operating conditions, their contribution is exceeded by that of the heat exchangers. This finding highlights the strong influence of non-ideal heat transfer processes and partial-load operation on overall system performance.

A particularly important outcome of the exergy analysis is the identification of the ammonia pumping subsystem as the weak thermodynamic link of the facility. The combined contribution of the low- and high-pressure ammonia pumps amounts to approximately 19.3% of the total exergy destruction. Among these, the low-pressure pumps exhibit a notably low Second Law efficiency of only 11.56%, indicating that a large fraction of the supplied mechanical work is dissipated through hydraulic losses and internal irreversibilities. This result suggests potential oversizing and flow mismatch issues, and clearly identifies the pumping system as a priority target for performance improvement.

By contrast, components such as the liquid receiver, pressure-regulating valves, and solenoid valves contribute only marginally to the total irreversibility of the system. Their combined share remains well below 1%, and their Second Law efficiencies exceed 98%, confirming that no significant thermodynamic improvement can be achieved through modifications to these elements.

The overall Second Law efficiency of the two-stage ammonia refrigeration system was determined to be 33.64%. This value is in reasonable agreement with previously reported efficiencies for industrial ammonia-based refrigeration and hybrid systems operating under comparable temperature levels. Slight deviations from higher efficiencies reported in controlled or optimized configurations can be attributed to the variable cooling load, partial-load compressor operation, and real-world heat transfer limitations encountered during the experimental campaign.

Overall, the exergy analysis demonstrates that, contrary to common assumptions in theoretical studies, heat exchangers rather than compressors dominate the irreversibility structure of the system under actual industrial conditions. Furthermore, the poor exergetic performance of the pumping subsystem underscores the importance of auxiliary equipment in determining the real efficiency limits of large-scale refrigeration plants.

3.3. Exergoeconomic Performance

The exergoeconomic performance of the two-stage ammonia refrigeration system was evaluated using the EXCEM (Exergy–Cost–Energy–Mass) method, which integrates thermodynamic inefficiencies with component-level economic indicators to identify priority areas for performance improvement [35,44]. This approach enables a consistent comparison of irreversibilities relative to the capital investment of each system component under steady-state operating conditions.

The results clearly indicate that the pumping subsystem represents the most critical exergoeconomic bottleneck of the facility. The highest Exergy Loss Ratio was observed in the ammonia circulation pumps, with a combined value of 2.45 W/USD, corresponding to 1.163 W/USD for the low-pressure (LP) pumps and 1.287 W/USD for the high-pressure (HP) pump. Despite their relatively modest capital costs compared to compressors, the pumps generate disproportionately high exergy destruction relative to investment, primarily due to hydraulic losses and flow mismatches. This finding identifies the pumping subsystem as the highest priority candidate for targeted upgrades and operational optimization.

Following the pumps, the high-pressure liquid receiver exhibited a notable exergoeconomic impact with a value of 1.353 W/USD, despite its high Second Law efficiency. This outcome reflects the sensitivity of exergoeconomic indicators to even moderate irreversibilities when associated with relatively low investment costs. In contrast, compressors—although responsible for a substantial share of total exergy destruction—display lower exergoeconomic loss ratios due to their comparatively higher capital investment, confirming that thermodynamic dominance does not necessarily translate into economic dominance.

From an energy-based cost perspective, the medium-temperature (+3 °C) evaporators were identified as the most significant contributors, with an Energy Loss Ratio of 2.152 W/USD. This result is primarily attributed to the electrical power consumption of the evaporator fans, highlighting the combined influence of thermal load and auxiliary electricity demand on operating costs.

It should be noted that the present exergoeconomic analysis focuses primarily on capital investment costs, while operating and maintenance (O&M) costs—such as electricity price fluctuations, scheduled maintenance, and downtime-related expenses—were not explicitly included. This limitation arises from the unavailability of detailed O&M cost data due to confidentiality constraints imposed by the facility operator, as well as the strong dependence of electricity prices on region-specific tariffs and contractual arrangements. Nevertheless, sensitivity considerations indicate that the relative exergoeconomic ranking of components would remain largely unchanged if operating costs were incorporated, as the dominant contributors to exergy destruction (heat exchangers and pumps) are structurally inherent to the system and operate continuously across seasonal conditions.

In this context, the EXCEM framework provides a robust and transparent basis for component prioritization. Compared to alternative exergoeconomic methods such as SPECO or advanced cost allocation approaches, EXCEM offers reduced modeling complexity and lower data requirements, which is particularly advantageous for full-scale industrial systems operating under real conditions. While more detailed cost partitioning could be achieved with advanced methods, the resulting component ranking and improvement priorities are not expected to differ significantly for the system investigated.

The practical applicability of the identified improvement strategies was also considered. Importantly, the proposed optimization directions—such as pump resizing, hydraulic balancing, and heat exchanger performance enhancement—can be implemented without requiring major redesign or replacement of the existing refrigeration plant. This makes the findings directly relevant and feasible for similar industrial ammonia-based refrigeration facilities.

Finally, the robustness of the exergoeconomic conclusions was assessed by considering measurement uncertainties. The estimated uncertainty of ±3.1% in heat transfer rates and ±4–5% in exergy efficiency calculations translates into minor variations in the calculated loss ratios. These variations do not alter the identification of pumps and heat exchangers as the primary exergoeconomic weak points of the system, confirming the reliability of the conclusions drawn.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a full-scale two-stage ammonia (R717) vapor compression refrigeration system operating in an integrated cold storage facility in Türkiye was evaluated using energy, exergy, and exergoeconomic analyses based on real industrial operating data. The main conclusions drawn from the study can be summarized as follows.

The energy analysis showed that the system operates with an overall First Law efficiency of 63.71%. This result confirms that, for industrial cold storage applications operating at evaporation regimes of −18 °C and +3 °C, the two-stage R717 refrigeration cycle provides a thermodynamically competitive and reliable solution. Under these operating conditions, satisfactory performance is achieved without the need for more complex cascade configurations, which are typically required only for deep-freezing applications below approximately −35 °C.

The exergy analysis revealed a clear deviation from conventional theoretical expectations regarding the dominant sources of thermodynamic irreversibility. Contrary to the widespread assumption that compressors govern system losses, the results demonstrated that heat exchangers are the primary contributors to total exergy destruction under real industrial operating conditions. More than 45% of the total irreversibility was associated with the evaporators and the evaporative condenser. This finding highlights the critical role of heat transfer processes, temperature difference management, surface cleanliness, and auxiliary fan operation in determining actual system efficiency [45]. Similar trends have also been reported in recent studies focusing on advanced condenser designs and realistic operating conditions, where heat exchangers were identified as dominant sources of irreversibility in industrial refrigeration systems [46,47].

The exergoeconomic analysis further identified the circulation pumps as the combined thermodynamic and economic weak point of the system. Despite their relatively low capital investment cost, the pumps exhibited the lowest Second Law efficiency (11.56%) and the highest exergoeconomic loss ratio (2.45 W/USD). This result demonstrates that auxiliary components, often overlooked during design-stage evaluations, can exert a disproportionate influence on long-term system performance and operating costs.

The robustness of these conclusions was confirmed through an uncertainty analysis. Measurement uncertainties of approximately ±3.1% for heat transfer rates and ±4–5% for exergy-based performance indicators resulted in only minor variations in calculated efficiencies and loss ratios. Importantly, these uncertainty bounds did not affect the relative ranking of system components in terms of exergy destruction or exergoeconomic importance, confirming the reliability of the main findings.

Based on the combined thermodynamic and economic assessments, several improvement strategies are recommended that can be realistically implemented in existing industrial ammonia refrigeration plants without requiring large-scale system redesign. These include retrofitting circulation pumps with high-efficiency units, implementing variable-speed control for evaporator fans using Variable Frequency Drives (VFDs), and maintaining compressor operation above approximately 60% load through improved load management and automation, where higher First Law efficiencies are observed.

Sensitivity considerations indicate that moderate variations in electricity prices or seasonal operating conditions would primarily influence absolute operating costs rather than the relative exergoeconomic ranking of system components. Since pumps and heat exchangers remain dominant contributors to irreversibility across different operating scenarios, the proposed improvement priorities are expected to remain valid under a wide range of economic and environmental conditions. This observation is consistent with recent sensitivity-based assessments reported in the literature, where component-level exergoeconomic rankings were shown to remain stable under varying electricity tariffs and ambient conditions [46].

It should be noted that the exergoeconomic analysis primarily focused on capital investment costs, while detailed operation and maintenance (O&M) costs were not explicitly included due to data confidentiality constraints and the strong dependence of electricity tariffs on site-specific contractual conditions. Although this represents a limitation of the present study, it does not compromise the general applicability of the component-level performance rankings.

Finally, the outcomes of this work provide a quantitative foundation for future investigations into hybrid and advanced refrigeration system configurations, such as systems integrated with thermal energy storage, renewable energy-assisted operation, or advanced heat recovery concepts. In line with recent developments in hybrid and enhanced refrigeration systems reported in the literature [46,47], the present findings offer practical guidance for prioritizing such configurations in next-generation sustainable industrial refrigeration applications.

5. Patents

No patents have been generated from the work reported in this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16031163/s1, Figure S1: Schematic representation of the two-stage NH3 (R717) vapor compression refrigeration system of the integrated cold storage facility. Table S1: Detailed energy, exergy, and exergoeconomic performance data of all system components, including energy transfer rates, exergy destruction, First- and Second-Law efficiencies, relative irreversibilities, and component-level cost parameters. Figure S2:. Photographs of the cycle components of the two-stage NH3 (R717) vapor compression refrigeration system of the integrated cold storage facility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.A. and Y.Ç.; Methodology, A.B.A.; Software, A.B.A.; Validation, A.B.A. and Y.Ç.; Formal analysis, A.B.A.; Investigation, A.B.A.; Resources, Y.Ç.; Data curation, A.B.A.; Writing—original draft, A.B.A.; Writing—review and editing, Y.Ç.; Visualization, A.B.A.; Supervision, Y.Ç.; Project administration, Y.Ç. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained directly from the industrial cold storage facility during on-site measurements. Due to confidentiality agreements with the facility operator, raw data cannot be made publicly available. Processed data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5.1) and Gemini (Google, Gemini 3, https://gemini.google.com, accessed on 10 December 2025) for language refinement and formatting support. The author has reviewed and edited all outputs and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication. The author also acknowledges the valuable academic guidance provided by Yunus Çerçi throughout the doctoral research. Special thanks are extended to Cesur Canpolat, the manager of the integrated cold storage facility, for his support and collaboration during the experimental measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

| () | Mass flow rate | kg s−1 |

| () | Specific enthalpy | kJ kg−1 |

| () | Specific entropy | kJ kg−1 K−1 |

| () | Heat transfer rate | kW |

| () | Work rate | kW |

| () | Energy transfer rate | kW |

| () | Specific flow exergy | kJ kg−1 |

| () | Exergy transfer rate | kW |

| () | Exergy destruction rate | kW |

| () | First-law (energy) efficiency | – |

| () | Second-law (exergy) efficiency | – |

| () | Relative irreversibility | – |

| () | Capital investment cost | € |

| () | Energy loss rate | kW |

| () | Exergy loss rate | kW |

| () | Energy loss ratio | – |

| () | Exergy loss ratio | – |

| Subscript | Description | |

| in/out | Inlet/outlet | |

| 0 | Dead-state (reference environment) | |

| LR | Liquid receiver | |

| HPR | High-pressure receiver | |

| LPR | Low-pressure receiver | |

| EVAP | Evaporator | |

| COND | Condenser | |

| LPC | Low-pressure compressor | |

| HPC | High-pressure compressor | |

| PUMP | Ammonia pump | |

| SV | Solenoid valve | |

| PV | Pilot valve | |

| elec | Electrical input | |

| FAN | Fan | |

| w | Water | |

| total | Overall system | |

| Symbol | Description | Value |

| () | Dead-state temperature | 30 °C |

| () | Dead-state pressure | 0.97 bar |

References

- Arora, A.; Kaushik, S.C. Energy and exergy analyses of a two-stage vapour compression refrigeration system. Int. J. Energy Res. 2010, 34, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, C.; Probert, D. Exergy-method analysis of a two-stage vapour compression refrigeration plant’s performance. Appl. Energy 1998, 60, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nicola, G.; Giuliani, G.; Polonara, F.; Stryjek, R. Blends of CO2 and HFCs as working fluids for the low-temperature circuit in cascade refrigerating systems. Int. J. Refrig. 2005, 28, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, S.; Villeneuve, S.; Mondor, M.; Uysal, I. Time–temperature management along the food cold chain: A review of recent developments. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 647–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, J.; Martins, A.; Fidalgo, L.; Lima, V.; Amaral, R.; Pinto, C.; Silva, A.; Saraiva, J. Fresh fish degradation and advances in preservation using physical emerging technologies. Foods 2021, 10, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vîrlan, A.; Siminiuc, R. Impact of storage conditions on the microbiological and organoleptic quality of cooked rice. J. Eng. Sci. 2025, 32, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köse, A.; Heidarnejad, P.; Fenni, B. Design of a cold storage with R507A refrigerant for the preservation of apples. Int. J. New Find. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2023, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makule, E.; Dimoso, N.; Tassou, S. Precooling and cold storage methods for fruits and vegetables. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcentales, G.; Lucas, M.; Guerrero, J.; Gordín, R. Evaluation for the reduction of NH3 contamination risks. Int. J. Life Sci. 2017, 1, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, S.; Mital, M. An ultra-low ammonia charge system for industrial refrigeration. Int. J. Refrig. 2019, 107, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, K. Application of NH3/CO2 refrigerant cooling system in a cold storage project. MATEC Web Conf. 2021, 353, 01014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.; Dasgupta, M.; Widell, K.; Bhattacharyya, S. Energetic, environmental and economic assessment of multi-evaporator CO2–NH3 cascade refrigeration system. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 148, 2845–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, P.; Dasgupta, M.; Hafner, A.; Widell, K.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Saini, S. Performance analysis of a CO2/NH3 cascade refrigeration system with subcooling. Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 153, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paula, C.; Duarte, W.; Rocha, T.; De Oliveira, R.; Maia, A. Energetic, exergetic, environmental, and economic assessment of a cascade refrigeration system. Int. J. Air Cond. Refrig. 2021, 29, 2150025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafi, M.; Naeynian, S.M.; Amidpour, M. Exergy analysis of multistage cascade low-temperature refrigeration systems. Int. J. Refrig. 2009, 32, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirl, N.; Schmid, F.; Bierling, B.; Spindler, K. Design and analysis of an ammonia–water absorption heat pump. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 165, 114531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, E.; Şahin, A. Comparative exergy analysis of cascade cooling systems. Int. J. Energy Appl. Technol. 2020, 7, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aized, T.; Rashid, M.; Riaz, F.; Hamza, A.; Nabi, H.Z.; Sultan, M.; Ashraf, W.M.; Krzywanski, J. Energy and exergy analysis of VCR systems with low-GWP refrigerants. Energies 2022, 15, 7246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Comparative analysis of cascade refrigeration systems. J. Therm. Eng. 2020, 6, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, T.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, W. Performance comparison of series and parallel two-stage cycles. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 1616–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, J.; Qiu, B.; Zhang, X. Energy and exergy analysis of ejector-assisted systems. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 3331–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.; Faruque, M.W.; Nabil, M.H.; Ehsan, M.M. Ejector and vapor injection enhanced cascade systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 289, 117190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiluna, D.N.G.; Donasco, E.A.A.; Hernandez, N.M.; Mamalias, J.B.A.; Viña, R.R. Energy and exergy analysis of modified two-stage cascade systems. Int. J. Refrig. 2025, 169, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, K.; Sahni, V.; Mishra, R.S. Energy, exergy and sustainability analysis of two-stage systems. J. Therm. Eng. 2015, 1, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula, C.H.; Duarte, W.M.; Rocha, T.T.M.; de Oliveira, R.N.; Maia, A.A.T. Environmental, energy and exergy analysis of VCR systems. Int. J. Refrig. 2020, 113, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepekci, H. Performance of refrigerants in two-stage VCR systems. Int. J. Low Carbon Technol. 2025, 20, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjili, F.E.; Cheraghi, M. Performance of a transcritical CO2 cycle with ejectors. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 156, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashtoush, B.; Sahli, H.; Elakhdar, M.; Megdouli, K.; Nehdi, E. CO2 refrigeration with two-phase ejector and parallel compression. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuhan, E. Two-stage VCR system with flash intercooling. Therm. Sci. 2020, 24, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wu, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Q. Optimal cycle characteristics of CO2 heat pumps. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 295, 117626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengel, Y.A.; Boles, M.A. Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bejan, A. Advanced Engineering Thermodynamics, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, M.J.; Shapiro, H.N.; Boettner, D.D.; Bailey, M.B. Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bejan, A. Entropy Generation Minimization: The Method of Thermodynamic Optimization of Finite-Size Systems and Finite-Time Processes; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dincer, I.; Rosen, M.A. Exergy: Energy, Environment and Sustainable Development; Newnes: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dincer, I.; Kanoglu, M. Refrigeration Systems and Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, M.A. Thermodynamic losses and capital costs. In Proceedings of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) Winter Annual Meeting, Dallas, TX, USA, 25–30 November 1990; pp. 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, M.A.; Dincer, I. Thermoeconomic analysis of power plants. Energy Convers. Manag. 2003, 44, 2743–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.A.; Dincer, I. Exergy–cost–energy–mass analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2003, 44, 1633–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopazo, J.A.; Fernandez-Seara, J. Experimental evaluation of a cascade refrigeration system prototype with CO2 and NH3 for freezing process applications. Int. J. Refrig. 2011, 34, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinti, G.; Liso, V.; Araya, S.S. Design improvements for ammonia-fed SOFC systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 15269–15279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, J.U.; Saidur, R.; Masjuki, H.H. A review on exergy analysis of vapor compression refrigeration system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1593–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, R.; Forootan, M.M.; Ahmadi, R.; Keshavarzzadeh, M. Exergy-economic assessment of a hybrid power, cooling and heating generation system based on SOFC. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor, A.; Tsatsaronis, G.; Gunerhan, H.; Hepbasli, A. Advanced exergoeconomic analysis of a gas engine heat pump (GEHP) for food drying processes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 91, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voloshchuk, V.; Gullo, P.; Nikiforovich, E. Advanced exergy analysis of ultra-low GWP heat pumps. Energies 2023, 16, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hu, E.; Chen, L. Performance Simulation Model of a Radiation-Enhanced Thermal Diode Tank-Assisted Refrigeration and Air-Conditioning (RTDT-RAC) System: A Novel Cooling System. Energies 2023, 16, 6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hu, E.; Chen, L. TRNSYS Simulation of a Bi-Functional Solar-Thermal-Energy-Storage-Assisted Heat Pump System. Energies 2024, 17, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.