Abstract

Background: Neuromodulation encompasses a range of methods aimed at selectively modifying nervous system function to enhance motor and neurophysiological processes. Although neuromodulation suits have shown benefits in clinical populations, their application in sports remains unexplored. Therefore, the aim of this case study was to examine the acute effects of a neuromodulation suit on the contractile properties of the rectus femoris muscle in an elite football player. Methods: The subject was an 18.8-year-old male professional football player. After conducting an anthropometric evaluation, initial tensiomyography (TMG) was carried out to evaluate the contractile properties of the rectus femoris, such as delay time (Td), contraction time (Tc), sustain time (Ts), relaxation time (Tr), and maximum radial displacement (Dm), in both legs. The athlete then donned a neuromodulation suit set to 20 Hz for a duration of 60 min. Following this, the same TMG measurements were repeated to assess post-intervention changes. Results: The right leg showed a reduction in Tc from 33.33 to 31.93 milliseconds (ms); Dm increased from 6.61 to 11.17 millimeters (mm). Conversely, the left rectus femoris exhibited prolonged Tc from 26.84 to 29.45 ms. Conclusions: A single 60 min session of neuromodulation suit application produced acute changes in muscle contractile properties. Findings suggest a potential positive effect on rapid force production and reduced muscle stiffness, alongside notable inter-limb variability.

1. Introduction

Neuromodulation encompasses a set of interventions that selectively modify the function of the nervous system to modulate neurophysiological processes, behavior, or the clinical course of disease. The literature describes a wide range of approaches, including operative procedures involving electrical stimulation of peripheral nerves, particularly vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), as well as non-invasive methods such as transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS), transcutaneous nerve stimulation (TNS), and various forms of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS), including transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Additionally, devices designed to target specific regions of the nervous system are used to achieve analgesic, anti-inflammatory, or other neurophysiological effects [1,2,3]. Neuromodulatory interventions play an important role in the treatment of neurological disorders, which comprise a broad spectrum of impairments of both the central and peripheral nervous systems and can affect motor, sensory, and cognitive functions. These conditions are associated with an increased risk of disease progression and premature mortality, with the risk further increasing with chronological age and being slightly more pronounced in men than in women. Given that neurological diseases rank among the three leading groups of causes of locomotor system impairment, often resulting in various forms of disability and considerable reductions in quality of life, the application of neuromodulatory methods represents a relevant and potentially effective approach within public health [4]. This is particularly significant considering that the effects of other physical therapy modalities, even when combined with pharmacotherapy, which remains the cornerstone of treatment for severe neurological conditions such as cerebral palsy, especially for reducing spasticity, show certain limitations. The effectiveness of targeted pharmacological agents often diminishes over time due to their limited duration of action, and long-term use may lead to the development of pharmacological tolerance. Surgical procedures directed at soft tissue structures (muscles, tendons, ligaments) or selective partial neurectomy of nerves affected by spasm also present inherent limitations, as their effects are often reversible, recovery can be prolonged, and postoperative pain may be considerable [5]. Non-invasive neurostimulation methods, including taVNS, TNS, and tDCS, although exhibiting therapeutic potential for modulating specific neural networks, are characterized by notable methodological constraints. These techniques generally exert highly localized effects, targeting only a single anatomical region or functional system at a time. Consequently, the spatial specificity and restricted range of the stimulation field limit their effectiveness in clinical conditions that require simultaneous, coordinated, multisystemic, and reciprocally inhibitory neuromodulation. This limitation is particularly evident in disorders involving diffuse spasticity, generalized hypertonicity, or widely distributed motor deficits, in which therapeutic benefit would require the concurrent modulation of multiple neuromuscular units or several cortical and subcortical regions. Thus, the applicability of these non-invasive procedures is reduced in complex neurological conditions, where functional dysfunction arises from disturbances in integrated motor networks rather than isolated neural units [6]. An alternative and more innovative approach to overcoming these therapeutic limitations is the use of a non-invasive neuromodulatory electrostimulation suit. The foundation of this therapeutic concept lies in the mechanism of reciprocal inhibition, whereby increased sensory afferent signaling from an activated muscle induces inhibition of its antagonist. Targeted excitation of the antagonist relative to the spastic muscle group reduces reflex-induced hyperactivity in the spastic muscle while simultaneously contributing to the functional strengthening of the often weakened antagonist. This approach aims to restore intermuscular balance and enhance neuromuscular coordination. The neuromodulation suit can be conceptualized as an advanced integrated platform, either non-invasive or potentially implantable, that combines neural interfaces, biocompatible materials, and multiple neuromodulatory modalities to exert precise influence on neural networks and associated physiological functions. Such a system enables simultaneous activation of multiple peripheral neural structures as well as flexible adjustment of stimulation parameters, making it suitable for therapeutic strategies requiring multisite or coordinated neuromuscular modulation [7,8,9,10]. Although an increasing body of evidence supports the effectiveness of neuromodulation suits in improving motor control and functional outcomes in various patient groups with severe neurological impairments, research examining the use of this technology outside medical settings and beyond strictly controlled clinical environments remains notably limited [11,12,13]. To the best of our knowledge, no experimental studies have investigated the application of a neuromodulation suit in athletic populations. This gap in the literature is particularly relevant given the essential role of maintaining optimal muscle tone in athletes and the potential benefits of targeted stimulation in facilitating faster and more efficient neuromuscular recruitment. Such modulation may enhance motor skills, improve coordination and agility, support adaptation to various training loads, reduce injury risks, and ultimately improve athletic performance. Among the available techniques, tensiomyography (TMG) provides a precise, quantitative assessment of muscle tone and the mechanical properties of skeletal muscles. It is a non-invasive technique frequently employed to evaluate the contractile characteristics of skeletal muscles by observing the radial displacement of the muscle belly after a controlled electrical stimulus. Its use has grown in sports science and clinical research due to its portability, user friendliness, and ability to facilitate repeated measurements without the need for voluntary muscle contraction. Regarding reliability, numerous systematic reviews and experimental studies indicate that TMG parameters show good to excellent test-retest and inter-rater reliability in both healthy and athletic populations. Specifically, the relative reliability, assessed through intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for essential parameters like contraction time (Tc), delay time (Td), and maximal radial displacement (Dm), has been shown to range from moderate to high (e.g., ICC from 0.70 to 0.99), affirming the consistency of these measurements when standardized protocols are followed [14,15].

Considering the multidimensional demands of modern sports, examining the effectiveness of neuromodulatory methods in this population represents a particularly relevant and innovative area of application. Therefore, the primary aim of this case study was to examine the effects of applying a neuromodulation suit on the contractile properties of the muscles in an elite athlete.

2. Materials and Methods

The participant included in this study was a professional male football player, 18 years and 8 months of chronological age, with 12 years included in structured football training. His dominant leg is the right leg, and he has no history of major lower limb injuries that could affect muscle contractile properties. Currently competing for the senior team of Football Club Osijek, a member of the Croatian First SuperSport League, and a player of the Croatian U19 national team. Within his team structure, the participant played as a central forward. At the time of the experimental procedure, the participant did not report any health complaints and was in good general health. Prior to the initiation of the study and the experimental protocol, the participant was fully informed of all potential risks and benefits of participation and provided written informed consent.

Experimental Protocol

The experimental protocol was conducted in the official facilities of the club, in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, under the supervision of a physiotherapist in the following sequence: First, basic anthropometric measurements of body height were obtained using an SECA stadiometer. Subsequently, body mass was assessed using TANITA BC—418MA body composition analyzer, and the relative proportions of muscle and fat tissue were calculated and expressed as percentages. After completing the anthropometric assessment, the contractile properties of the rectus femoris muscles of both legs were evaluated using a TMG device. Measurements were performed as previously and thoroughly described in official protocol [16] using a digital displacement transducer (GK 40, Panoptik d.o.o., Ljubljana, Slovenia) featuring a spring stiffness of 0.17 N/mm. The sensor was positioned perpendicular to the muscle belly and applied with an initial pressure of 1.5 × 10−2 N/mm2. It was placed at the thickest point of the muscle, determined visually and through palpation during a voluntary contraction. Muscle stimulation was delivered via two electrodes (Axelgaard, Pulse, Fallbrook, CA, USA), positioned 2–5 cm apart and connected to an electrostimulator (TMG-S1, Furlan and Co., Ltd., Ljubljana, Slovenia). The participant was positioned in a supine posture following a predefined protocol. In order to reduce measurement error and obtain the most accurate results, rest periods of approximately 20 s were allowed between consecutive TMG measurements to minimize the effects of fatigue and post-activation potentiation. To minimize measurement error and ensure reproducibility, the exact sensor placement on the muscle belly was marked using a dermographic pen, allowing consistent positioning across repeated measurements. This approach reduced variability related to sensor relocation and contributed to the reliability of the recorded TMG parameters. Stimulation protocol started at an initial frequency of 20 Hz, which was subsequently increased by 10 Hz in each measurement until a plateau in contractile response was observed. A stimulation frequency of 50 Hz was identified as optimal, as further increases did not result in additional increases in radial displacement of the muscle belly. The following muscle contractile parameters relevant to the study were evaluated: Tc, Td, Ts, Tr, all expressed in milliseconds (ms), as well as muscle displacement amplitude (Dm), expressed in millimeters (mm). Following the initial TMG assessment, the participant was fitted with an Exopulse Mollii neuromodulation suit (Inerventions AB, Danderyd, Sweden) that had been pre-programmed by a certified institution Ottobock Adria Sarajevo. Neuromodulation suit was configured to target all major muscle groups of the lower extremities bilaterally. Specifically, stimulation was applied to the anterior muscle groups (including the quadriceps femoris and tibialis anterior) and posterior muscle groups (including the hamstrings, gluteal muscles, and triceps surae) of both legs. Low-intensity electrical stimulation (pulse width 25–175 μs) was applied to target specific muscle groups at different frequencies: 20 Hz for the quadriceps, 16 Hz for the tibialis anterior, 18 Hz for the gluteal region, 16 Hz for the hamstrings, and 14 Hz for the triceps surae. These stimulation frequencies below 20 Hz are commonly used to achieve motor modulation and reduce spasticity, as repetitive stimulation sequences can induce facilitation and functional reorganization of sensorimotor pathways. Moreover, they provide a favorable balance between efficacy and tolerability, which is why such frequencies are frequently employed as initial or reference values in pilot studies and review articles investigating external neuromodulation for motor related outcomes. [10]. By applying a lower intensity impulse to the posterior thigh muscles compared to the anterior muscles, we aimed to elicit an excitatory effect in the quadriceps muscles. During the neuromodulation procedure, the participant remained resting in a supine position for 60 min. The choice of a 60 min session for the neuromodulation suit application was informed by existing experimental protocols found in the literature. These protocols often utilize a single 60 min session of Exopulse Mollii stimulation to investigate its immediate effects on neuromuscular function and spasticity. For instance, earlier research that examined 60 min of Exopulse Mollii stimulation used this timeframe to evaluate both objective neuromuscular and clinical outcomes [10].

Upon completion of the 60 min session, the suit was removed, and the same muscle contractile properties were assessed using the TMG device, following the identical procedure and protocol as in the initial measurement.

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes the participant’s basic anthropometric measurements, including age, sex, body height and mass, and relative proportions of muscle and fat.

Table 1.

Basic Anthropometric Measurements of the Participant.

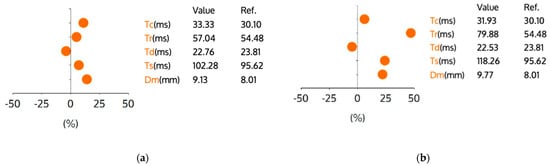

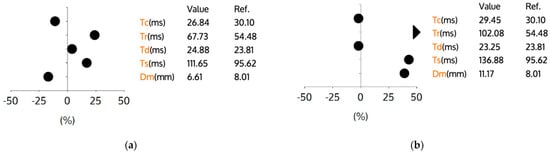

Figure 1 and Figure 2 present the tensiomyographic parameters of the rectus femoris muscle before (a) and after (b) a 60 min session using the Exopulse Mollii neuromodulation suit. In Figure 1, the right rectus femoris shows a decrease in Tc from 33.33 ms to 31.93 ms. The Tr increased from 57.04 ms to 79.88 ms, while the Td slightly dropped from 22.76 ms to 22.53 ms. The Ts rose from 102.28 ms to 118.26 ms, and the Dm increased from 9.13 mm to 9.77 mm. In Figure 2, the left rectus femoris experienced an increase in Tc from 26.84 ms to 29.45 ms. The Tr went up from 67.73 ms to 102.08 ms, and the Td decreased from 24.88 ms to 23.25 ms. The Ts increased from 111.65 ms to 136.88 ms, and the Dm rose from 6.61 mm to 11.17 mm. Overall, the neuromodulation session led to distinct, limb-specific changes in the main TMG parameters (Tc, Td, Tr, Ts, and Dm) from pre- to post-session, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Subsequent figures present the TMG parameter results of the rectus femoris muscle before and after the application of the Exopulse Mollii neuromodulation suit.

Figure 1.

TMG parameters for the right rectus femoris muscle. Graph (a) represents the muscle contractile parameters before application of Exopulse Mollii suit. Graph (b) represents the muscle contractile parameters after application of Exopulse Mollii suit. Legend: Y-axis units represent percent change relative to the reference value provided in the table, Tc—contraction time (ms), Tr—relaxation time (ms), Td—delay time (ms), Ts—sustain time (ms), Dm—maximal displacement (mm), Ref—indicates the reference value for football players. Each dot represents the relative change for the corresponding parameter compared to the reference.

Figure 2.

TMG parameters for the left rectus femoris muscle. Graph (a) represents the muscle contractile parameters before application of Exopulse Mollii suit. Graph (b) represents the muscle contractile parameters after application of Exopulse Mollii suit. Legend: Y-axis units represent percent change relative to the reference value provided in the table, Tc—contraction time (ms), Tr—relaxation time (ms), Td—delay time (ms), Ts—sustain time (ms), Dm—maximal displacement (mm), Ref—indicates the reference value for football players. Each dot represents the relative change for the corresponding parameter compared to the reference.

4. Discussion

The results of this case study indicate several relevant findings. The participant was male, 18 years and 8 months old, placing him in late adolescence, a stage in which anthropometric parameters are generally stabilized and body composition closely resembles that of adult elite athletes. His stature of 187 cm and body mass of 77.9 kg reflect a morphological profile typical for professional central forwards height combined with a relatively low body mass for stature contributes to agility, speed, and explosive performance. A muscle mass percentage of 50.9% is markedly high and consistent with values reported in elite football players, indicating a high level of training and optimal muscular development to meet the demands of modern football. The body fat percentage of 9.4% falls within the ideal range for top level football players (typically 7–12%), confirming good physical conditioning, a favorable muscle to fat ratio, and low metabolic risk [17,18,19]. The most notable observation was the potential effectiveness of the neuromodulation suit in modifying muscle contractile properties. After one hour of neuromodulatory stimulation, a reduction in the Tc of the right rectus femoris muscle was recorded (from an initial 33.33 ms to 31.93 ms). This muscle plays a key role in the kinetic chain due to its biarticular function and substantially contributes to knee joint stability and balance maintenance during various movement patterns [20,21]. Additionally, the reduction in the time required to generate muscle contraction (−1.4 ms in this case) may indicate an improved capacity for force development, and consequently greater power and speed of movement execution [22,23,24]. These capabilities are essential determinants of football performance, particularly in explosive actions such as sprinting, change in direction, and jumping. Collectively, these findings support the assumption that short-term neuromodulation can induce acute alterations in neuromechanical muscle properties, with potential functional implications relevant to athletic performance. The minimal change in Td indicates that peripheral neural conduction and excitation contraction coupling remain intact after the intervention. The observed sustained increase in Tr and Ts suggests alterations in neural control, possibly due to prolonged excitatory drive or modifications in inhibitory pathways that regulate muscle relaxation and sustained activation. Since Tr and Ts are modulated by central neural input and sensorimotor integration, these changes likely reflect central nervous system adaptations rather than peripheral mechanical factors alone [25]. However, the results obtained for the left leg revealed a markedly different pattern. The contractile properties of the left rectus femoris demonstrated a prolonged Tc, increasing from 26.84 ms to 29.45 ms. This Tc increase of 2.61 ms may be explained by several mechanisms. First, the participant was right-foot dominant and primarily used the right leg during technical actions with the ball. Such movement specializations can lead to pronounced biomechanical asymmetries, which may manifest as differences in muscle mass and neuromechanical responsiveness. This pattern is expected, as right-footed players predominantly rely on the left leg during kicking, passing, or take-off movements. In the support phase, the left leg provides stability and is subjected to increased force generation and higher mechanical loading. Asymmetric loading can result in divergent motor unit recruitment patterns, potentially contributing to prolonged contraction times and altered contraction dynamics [26,27]. Furthermore, one of the indicators of muscle fatigue is Dm. In the initial assessment of the left rectus femoris, a value of 6.61 mm was recorded, which was substantially below the reference value for football players (8.01 mm). This reduced baseline Dm value indicates increased muscle stiffness caused by fatigue, which may influence the central mechanisms of movement control and subsequently lead to altered motor unit recruitment patterns during electrical stimulation [27,28]. This heightened stiffness provides important context for interpreting post-intervention changes. Specifically, the low frequency 20 Hz stimulation, reported to have an inhibitory effect [10], may have contributed to modulating the neuromechanical behavior of the muscle. This is evident in the marked increase in Dm of the right rectus femoris muscle after treatment (11.17 mm), which indicates reduced muscle stiffness and enhanced muscle relaxation [28]. A decrease in Td from 24.88 ms to 23.25 ms, coupled with a 9.7% increase in Tc, may reflect an adaptation in motor unit recruitment. Specifically, the central nervous system initiates activation more rapidly (shorter Td), while the contraction develops more gradually (longer Tc), potentially facilitating controlled and sustained force production rather than rapid, explosive output. The marked increases in Tr from 67.73 ms to 102.08 ms, and Ts from 111.65 ms to 136.88 ms, suggest prolonged muscle activation and delayed relaxation, which could indicate enhanced excitatory drive and a possible reduction in presynaptic inhibition at the spinal level [29]. Importantly, these patterns are likely indicative of an adaptive neurophysiological approach rather than a deficiency: the central nervous system might extend activation in the left limb to preserve stability and enhance proprioceptive feedback, especially if the limb is less dominant or more prone to disturbances. For instance, in a soccer context, when a player lands on the nondominant leg following a lateral pass, the muscle might sustain increased tone for a longer duration to improve postural control and avert ankle or knee instability, even if the contraction occurs more gradually. These asymmetric adaptations highlight the Mollii suit’s impact on the central excitatory inhibitory balance and sensorimotor integration, emphasizing that the observed extension of Tr and Ts is functionally significant and neurophysiologically driven [25,30]. Also, the asymmetric adaptations observed in the left limb may reflect central neurophysiological modulation rather than peripheral deficit, where the central nervous system adjusts excitatory–inhibitory balance to support postural control and motor output. Similar principles have been described in studies of non-invasive neuromodulation of spinal circuitry, where targeted electrical stimulation alters spinal network excitability and motor output patterns. For example, Gerasimenko and colleagues demonstrated that transcutaneous electrical spinal cord stimulation (tSCS) can modulate spinal locomotor circuits and facilitate coordinated stepping movements in both non injured and spinal cord injured human subjects, suggesting engagement of propriospinal and sensorimotor pathways rather than simple muscle activation alone [31].

Study Limitations

This study has several inherent limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, as a single-subject case study, the findings cannot be generalized to larger populations, and individual variability may influence the observed neuromuscular responses. Second, the absence of a control group limits the ability to determine whether the changes in TMG parameters are solely attributable to the Mollii suit intervention or may reflect natural variability, learning effects, or other external factors. Third, measurements were performed only before and after the intervention, without multiple time points or longitudinal follow-up, which restricts understanding of temporal stability or potential long-term adaptations. Finally, while TMG provides valuable insights into neuromuscular function, it does not directly measure central nervous system activity or proprioceptive integration, and thus interpretations regarding neurophysiological mechanisms remain indirect.

Despite these limitations, the case study provides detailed insights into limb-specific neuromuscular adaptations to a neuromodulatory intervention, highlighting areas for future research with larger samples and controlled designs.

5. Conclusions

This case study demonstrates that short-term, 60 min application of the Exopulse Mollii suit can induce acute, limb-specific neuromuscular adaptations in an elite adolescent football player. Changes in tensiomyography parameters indicate that the intervention can modulate both muscle mechanical properties and central neural control mechanisms. Specifically, the right limb showed faster contraction and reduced muscle stiffness, reflecting enhanced neuromuscular efficiency, while the left limb exhibited prolonged contraction and relaxation dynamics, likely representing an adaptive neurophysiological strategy to support stability and proprioceptive integration. These findings suggest that the potential of non-invasive neuromodulatory interventions, such as the Mollii suit, may influence motor unit recruitment, excitatory–inhibitory balance, and postural control, with potential implications for athletic performance in explosive and stability-demanding actions. However, as a single-subject pilot study without a control group, these results are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution. Further research with larger samples, objective assessments of limb dominance and strength asymmetry, and longitudinal follow up is necessary to confirm these effects and determine their functional relevance in sport and rehabilitation contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.J. and I.P.; methodology, N.C.; formal analysis, I.P.; investigation, E.J. and I.P.; resources, E.J.; data curation, N.C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.P.; writing—review and editing, E.J.; visualization, N.C.; supervision, E.J.; project administration, E.J.; funding acquisition, E.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Ottobock SE & Co. KGaA, Max-Nader Strasse 15, 37115 Duderstadt, Germany.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Kinesiology Osijek, University of Josip Juraj Strossmayer Osijek (CLASS: 029-01/25-01/05, REG.NO.: 2158-110-01-25-61, approved on 16 December 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed and written consent was obtained from subject involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Monika Boras for her assistance in adjustment and programming Mollii suit, Amer Suljic for his support during the testing procedures, Zeljka Micic for medical supervision, and Marko Husic for administrative and logistical support. The authors also thank the participant for his time and cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Howland, R.H. Vagus Nerve Stimulation. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 2014, 1, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Lu, Z.; He, W.; Huang, B.; Jiang, H. Autonomic Modulation by Electrical Stimulation of the Parasympathetic Nervous System: An Emerging Intervention for Cardiovascular Diseases. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2016, 34, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, K.; Chaudhry, H.; Williams, K.; Christo, P.J. Review of the Uses of Vagal Nerve Stimulation in Chronic Pain Management. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2015, 19, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deuschl, G.; Beghi, E.; Fazekas, F.; Varga, T.; Christoforidi, K.A.; Sipido, E.; Bassetti, C.L.; Vos, T.; Feigin, V.L. The Burden of Neurological Diseases in Europe: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e551–e567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedin, H.; Wong, C.; Sjödén, A. The Effects of Using an Electrodress (Mollii®) to Reduce Spasticity and Enhance Functioning in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Pilot Study. Eur. J. Physiother. 2020, 24, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Alén, L.; Ros-Alsina, A.; Sistach-Bosch, L.; Wright, M.; Kumru, H. Noninvasive Electromagnetic Neuromodulation of the Central and Peripheral Nervous System for Upper-Limb Motor Strength and Functionality in Individuals with Cervical Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sensors 2024, 24, 4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, S.M.; Song, E.; Reeder, J.T.; Rogers, J.A. Emerging Modalities and Implantable Technologies for Neuromodulation. Cell 2020, 181, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacour, S.P.; Courtine, G.; Guck, J. Materials and Technologies for Soft Implantable Neuroprostheses. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, A.; Pouratian, N. Brain Imaging Correlates of Peripheral Nerve Stimulation. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2012, 3, S260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennati, G.V. Theoretical Framework for Clinical Applications of Mollii; Karolinska Institutet, Department of Clinical Sciences, Danderyd Hospital, Division of Rehabilitation Medicine: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Apolo-Arenas, M.D.; Tomas-Carus, P.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Parraca, J.A. Comparative Analysis of Psychophysiological Responses in Fibromyalgia Patients: Evaluating Neuromodulation Alone, Neuromodulation Combined with Virtual Reality, and Exercise Interventions. Medicina 2024, 60, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, J.G.; Chalah, M.A.; Ouerchefani, N.; Sorel, M.; Le Guilloux, J.; Lefaucheur, J.P.; Lahoud, G.N.A.; Ayache, S.S. The Effect of the EXOPULSE Mollii Suit on Pain and Fibromyalgia-Related Symptoms: A Randomized Sham-Controlled Crossover Trial. Eur. J. Pain 2025, 29, e4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayache, S.S.; Mattar, J.G.; Créange, A.; Abdellaoui, M.; Zedet, M.; Lefaucheur, J.-P.; Megherbi, H.; Khaled, H.; Lahoud, G.N.A.; Chalah, M.A. The Effect of the EXOPULSE Mollii Suit on Motor Functions in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Randomized Sham-Controlled Crossover Trial. Mult. Scler. J. Exp. Transl. Clin. 2025, 11, 20552173251348304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čular, D.; Babić, M.; Zubac, D.; Kezić, A.; Macan, I.; Peyré-Tartaruga, L.A.; Ceccarini, F.; Padulo, J. Tensiomyography: From muscle assessment to talent identification tool. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1163078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rodríguez, S.; Loturco, I.; Hunter, A.M.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, D.; Munguia-Izquierdo, D. Reliability and measurement error of tensiomyography to assess mechanical muscle function: A systematic review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 3524–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuba-Dorado, A.; Álvarez-Yates, T.; Iglesias-Caamaño, M.; Carballo-López, J.; Abalo-Rey, J.M.; Riveiro-Bozada, A.; Garcia-Remeseiro, T.; García-García, O. Neuromuscular Characteristics of Elite and Age Groups Triathletes from World Multisport Championships. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2026, 21, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, C.; Campa, F.; Holway, F.; Pengue, L.; Arrones, L.S. ISAK-Based Anthropometric Standards for Elite Male and Female Soccer Players. Sports 2024, 12, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spehnjak, M.; Gušić, M.; Molnar, S.; Baić, M.; Andrašić, S.; Selimi, M.; Mačak, D.; Madić, D.M.; Fišer, S.Ž.; Sporiš, G.; et al. Body Composition in Elite Soccer Players from Youth to Senior Squad. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittich, A.; Oliveri, M.B.; Rotemberg, E.; Mautalen, C. Body Composition of Professional Football (Soccer) Players Determined by Dual X-Ray Absorptiometry. J. Clin. Densitom. 2001, 4, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.E.; Pain, M.T. A Combined Muscle Model and Wavelet Approach to Interpreting the Surface EMG Signals from Maximal Dynamic Knee Extensions. J. Appl. Biomech. 2010, 26, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enocson, A.; Berg, H.E.; Vargas, R.; Jenner, G.; Tesch, P.A. Signal Intensity of MR-Images of Thigh Muscles Following Acute Open- and Closed-Chain Kinetic Knee Extensor Exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 94, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubiak, R.J.; Whitman, K.M.; Johnston, R.M. Changes in Quadriceps Femoris Muscle Strength Using Isometric Exercise versus Electrical Stimulation. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 1987, 8, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dervišević, E.; Bilban, M.; Valenčic, V. The Influence of Low-Frequency Electrostimulation and Isokinetic Training on the Maximal Strength of M. Quadriceps Femoris. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 2002, 10, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.J.; Widrick, J.J. Combined Effects of Fatigue and Eccentric Damage on Muscle Power. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 107, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajovic, L.; Toskic, L.; Stankovic, V.; Lilic, L.; Cicovic, B. Muscle contractile properties measured by the tensiomyography (TMG) method in top—Level football players of different playing positions. The case of Serbian super League. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, M.; Griffin, L.; Abraham, L.; Brandt, L. Alternating Stimulation of Synergistic Muscles during Functional Electrical Stimulation Cycling Improves Endurance in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2010, 20, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnier, Y.M.; Lepers, R.; Canepa, P.; Martin, A.; Paizis, C. Effect of the Knee and Hip Angles on Knee Extensor Torque: Neural, Architectural, and Mechanical Considerations. Front. Physiol. 2022, 12, 789867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toskić, L.; Dopsaj, M.; Stanković, V.; Marković, M. Concurrent and Predictive Validity of Isokinetic Dynamometry and Tensiomyography in Differently Trained Women and Men. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 2019, 27, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macgregor, L.J.; Hunter, A.M.; Orizio, C.; Fairweather, M.M.; Ditroilo, M. Assessment of skeletal muscle contractile properties by radial displacement: The case for tensiomyography. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1607–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Diaz, P.; Alentorn-Geli, E.; Ramon, S.; Marin, M.; Steinbacher, G.; Rius, M.; Seijas, R.; Ballester, J.; Cugat, R. Effects of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on neuromuscular tensiomyographic characteristics of the lower extremity in competitive male soccer players. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2015, 23, 3407–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimenko, Y.; Gorodnichev, R.; Moshonkina, T.; Sayenko, D.; Gad, P.; Edgerton, V.R. Transcutaneous electrical spinal-cord stimulation in humans. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 58, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.