Abstract

The last kilometer connection problem of metro transit stations is the core factor to measure the connection efficiency and service quality. Establishing the spatiotemporal distribution pattern of the connection distance is conducive to clarifying the interaction mechanism between bike-sharing connections and urban space. This study focuses on the travel behavior of shared bicycle users accessing metro stations, aiming to reveal the access distance decay patterns and their relationship with influence factors. Finally, the random forest algorithm was used to explore the nonlinear relationship between the influencing factors and the connection decay distance, and to clarify the importance of the factors. Multiple linear regression was applied to examine the linear correlation between the distance decay coefficient and the factors influence. The geographically weighted regression was further employed to explore spatial variations in their effects. Finally, the random forest algorithm was used to rank the importance of the impact factors. The results indicate that proximity distance to metro stations, proximity distance to bus stops, and the number of bus routes serving the station area have significant negative correlations with the distance decay coefficient. Significant spatial heterogeneity was observed in the influence of each factor on the distance decay coefficient, based on the geographically weighted regression analysis. With a high goodness-of-fit (R2 = 0.8032), the Random Forest regression model furthermore quantified the relative importance of each factor influencing the distance decay coefficient. The findings can be directly applied to optimize the layout of shared bicycle parking, metro access facilities planning, and multi-modal transportation system design.

1. Introduction

As a typical green travel mode, bicycle-sharing (BS) not only effectively addresses the “last-mile” connectivity challenge but also serves as a crucial driver for low-carbon transformation in urban transportation [1]. In China, the user base of shared bicycles has grown from 310 million in 2017 to 460 million in 2022. As of 2024, Hellobike has surpassed 750 million registered users. Within metro systems, BSs play a key bridging role, significantly enhancing the accessibility and efficiency of the overall urban transportation network [2].

At the core of understanding BS’s spatial interaction patterns lies the concept of distance decay—a fundamental geographical principle describing how the intensity of human mobility flows (e.g., bike trips) diminishes as travel distance increases [3]. Distance decay is not only critical for modeling travel demand and evaluating the accessibility of bike-sharing services but also serves as a foundational input for land use planning, bike fleet allocation, and the optimization of multi-modal transport integration [4,5]. For BS, in particular, distance decay exhibits inherent spatial heterogeneity: variations across urban contexts driven by built environment factors, infrastructure distribution, and user behavior, which directly impacts the accuracy of demand forecasting and system optimization [6]. Unpacking this heterogeneity and identifying the key influencing factors is therefore essential for evidence-based BS management.

Early studies on bike-related distance decay relied on small-scale survey data, limiting generalizability to shared bikes. Iacono et al. [7] and Yasmin et al. [8] explored distance decay for private bicycles using self-reported surveys, but their focus on non-shared modes and narrow geographic coverage failed to capture the unique dynamics of DLBS. With the advent of large-scale transactional data, Kou and Cai [9] analyzed distance decay for docked bike-sharing systems (DBS) across eight U.S. cities, confirming power-law decay for trip distance and duration. Li et al. [10] further explored this by incorporating road network data to estimate actual riding distances (rather than Euclidean distances, which underestimate real trip lengths) and confirmed that exponential functions best captured DLBS distance decay, as they more accurately reflected how trip intensity declines with realistic, network-constrained distances. Despite being standard choices for modeling spatial interactions, the use of exponential and power functions for DLBS is subject to ongoing debate.

The rise in DLBS has spurred research into its distance decay heterogeneity. Gao et al. [6] conducted a landmark study in Shanghai, leveraging 27 million DLBS transactions and routing APIs to estimate decay functions. Through multiple linear regression analysis, their study identified key built environment drivers. It was found that higher population density, greater land use entropy, and increased branch road density were associated with a stronger distance decay. Conversely, a higher proportion of commercial/industrial land use and greater motorway density were linked to a weaker decay effect. They employed Adaptive Geographically Weighted Regression (AGWR) to capture spatial non-stationarity, revealing that factors like population density had more pronounced effects in newly developed districts (e.g., Shanghai’s Pudong) than in downtown areas. This work highlighted the inadequacy of global models (e.g., MLR) for DLBS decay but left unresolved questions about the performance of more flexible, nonlinear models in capturing complex factor interactions.

A key limitation of existing research is the limited comparison of modeling approaches for quantifying distance decay heterogeneity. MLR, while useful for global factor associations, assumes uniform relationships across space and linearity, assumptions that may not hold for DLBS, where factors like land use mix and road infrastructure often interact nonlinearly [11]. AGWR addresses spatial non-stationarity by estimating local coefficients, but it still relies on linearity assumptions and may struggle with high-dimensional or collinear predictors [12]. Conversely, machine learning approaches such as Random Forest (RF) are capable of capturing nonlinear relationships, managing collinearity among variables, and evaluating feature importance without relying on strict distributional assumptions [13]. RF has been applied to bike-sharing demand forecasting [14] but remains underutilized in distance decay heterogeneity analysis, leaving a gap in understanding which modeling approach best captures the spatial variability of DLBS decay coefficients.

Furthermore, existing studies often focus on identifying influencing factors but rarely evaluate how different models alter interpretations of factor impacts on decay heterogeneity. For instance, within both the Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) frameworks, the degree of functional mixture emerges as linearly associated with the distance decay coefficient, but it shows a nonlinear relationship in the random forest model. Without comparing these models, researchers and practitioners risk relying on incomplete or biased insights into decay drivers and undermining DLBS planning decisions like fleet allocation and infrastructure investment.

To address these gaps, this study aims to evaluate the performance of three modeling approaches, namely Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR), and Random Forest (RF), in quantifying the spatial heterogeneity of BS connection distance decay coefficients and identifying their key influencing factors. This study integrates multi-source data to delineate metro station catchment areas using the 85th percentile distance of BS access trips. This study seeks to investigate, from global, local, and nonlinear dimensions, the interplay between multiple factors and the distance decay coefficient in BS connections. The research outcomes provide a theoretical foundation for optimizing BS rebalancing strategies around metro stations and scientifically planning parking facilities, thereby enhancing access efficiency and promoting sustainable green mobility.

The paper is structured as follows: the Introduction provides a review of relevant literature on connection distance fitting and the factors influencing BS systems. In the Data Resources, the sources of the multi-source data are introduced. In the Methodology section, the model and regression model for fitting the connection distance decay law were introduced. In the Results section, we analyzed the distribution characteristics of the distance decay coefficient and demonstrated the influence of different factors on different dimensions. The last section synthesizes the main conclusions, discusses the practical implications for planning, and suggests directions for future research.

2. Data Resources

At the end of 2024, the permanent resident population of Beijing is 21.832 million. The statistical data indicate that the total volume of urban passenger trips hit 7.347 billion person-times, with urban rail transit trips and shared bike trips registering at 3.622 billion person-times and 1.144 billion person-times, accounting for 49.3% and 15.5% of the total urban passenger trips, respectively.

The 2019 dataset was employed in this study. By 2019, Beijing’s core metro and bus network had achieved a stable, mature structure, and the BS industry was in a steady developmental phase. All multi-source data, including BS trips, urban spatial attributes, and demographic metrics, are temporally consistent with 2019, eliminating biases arising from cross-temporal mismatches, given that this study focuses on the inherent relationships between the built environment and bike-sharing access distance decay. The key influencing factors remaining unchanged over time, and the findings derived from the 2019 dataset, retain strong practical implications for guiding current connection transportation system planning and optimization.

2.1. BS Data

The analysis is based on Beijing’s BS data spanning one week (3–9 March 2019), which contains detailed information, including bike ID, and the time and location of each rental and return event. The dataset recorded approximately 350,000 orders per day. Some metro stations, particularly those in suburban areas or with inadequate BS system coverage, had very low or even zero access volume. Consequently, to ensure the reliability of the regression model, attribute data from 234 metro stations were retained for further analysis.

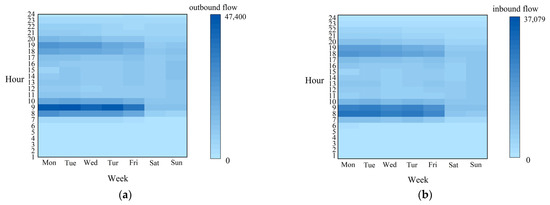

BS access to metro stations refers to trips connecting bicycles to the various entrances and exits of a station. The common approach of treating an entire station as a single point is prone to error, as exits can be far apart near large interchanges, commercial streets, or tourist attractions. To address this, we precisely mapped the location of each station exit using oMap (A cross-platform map browsing software developed by Beijing Yuan Sheng Hua Wang Software Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). A BS trip was subsequently classified as an access trip if its rental or return position was within 100 m of any station exit. At the same time, ensure the uniqueness of the BS accessed to the same metro station at the same time, and ultimately obtain all the BS access trips of each metro station. As shown in Figure 1, the daily bike-sharing access frequency over the week indicates that the morning and evening peak characteristics are strikingly more pronounced on weekdays than on weekends.

Figure 1.

The access flow distribution of bike-sharing at subway station (a) inbound flow, (b) outbound flow.

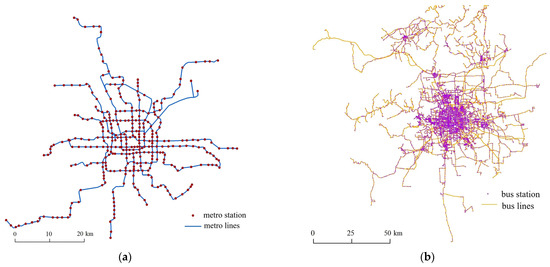

2.2. Urban Spatial Data

Data on the 2019 urban metro and bus networks were sourced from the Gaode Map platform. The spatial distribution of stations and lines for both networks is shown in Figure 2. Furthermore, the Points of Interest (POI) data, covering 16 primary categories (e.g., food and services), were processed for this research. This analysis focused on the following 10 categories: Catering, Scenic Spots, Companies, Shopping, Science-Education-Culture, Residential-Commercial Buildings, Life Services, Sports-Recreation, Healthcare, and Government-Social Organizations.

Figure 2.

Distribution of metro and bus network in Beijing (a) metro network, (b) bus network.

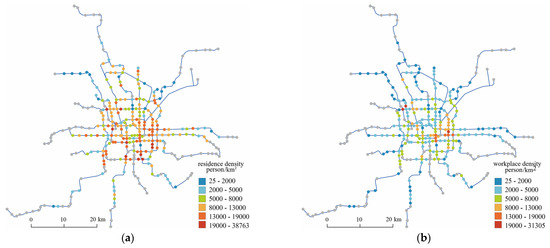

Daily commuting behavior is characterized by regular movement between residential and workplace locations. Probable residential and employment locations are inferred by analyzing the spatiotemporal patterns in mobile user data and calculating stay durations in various areas over consecutive days. The specific processing steps are as follows: First, the raw data obtained from telecommunications operators is preprocessed. Subsequently, user attributes related to residence and employment are extracted by integrating the temporal distribution patterns, the temporal attributes of the communication data, and user stay behavior, followed by the construction of corresponding membership functions. On this basis, a standard feature vector is established, and discrimination rules between this vector and the data under examination are formulated to identify the user’s employment and residential locations. Based on one month of mobile signal data from 2019, the distribution characteristics of residents’ travel chains were extracted, the commuting population was identified, and their residence and workplace were determined. The work density and residential density of the traffic zone were obtained as the job and residential density attributes of the metro station, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The residence, workplace density distribution of metro station in Beijing (a) residence density, (b) workplace density.

3. Methodology

To delve into the distance decay characteristics of BS behavior and their quantitative relationship with built environment factors, we first establish a distance decay model to characterize how such behavior varies with distance and extract the key distance decay coefficient. Based on this, a regression analysis method is employed to quantitatively examine the mechanisms through which multidimensional factors influence the decay coefficient. This provides a methodological foundation for understanding the patterns of connectivity between urban non-motorized transport and metro transit.

3.1. Constructing the Distance Decay Function

The distance decay function mathematically characterizes the relationship between travel distance and the cumulative percentage of BS trips used for metro access. Although various forms of distance decay functions have been proposed in existing studies, power functions and exponential functions are still the most commonly used in relevant research [6,10]. This paper employs exponential function fitting to analyze the distance decay pattern of BS at metro stations, and its formula is as follows:

where P(x) represents the cumulative proportion of trips with riding distances greater than x meters. Since the distance decay law is sensitive when the travel distance exceeds a certain threshold, trips with a riding distance of less than 300 m (i.e., γ = 300) are excluded to eliminate their impact on the fitting results. b represents the distance decay coefficient, which indicates the decline rate of BS trip volume with increasing distance. This coefficient is estimated based on the Euclidean distance of each metro station.

3.2. Regression Model Fitting

To explore the influence of built environment factors on the connection distance decay of BS, this study introduces three regression models: Ordinary Least Squares Regression (OLSR), Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR), and Random Forest Regression (RFR) models.

3.2.1. Ordinary Least Squares Regression

Ordinary least squares regression is a commonly used linear regression method, aiming to obtain model parameters by minimizing the difference between the true values and predicted values of the response variable. The equation expression is as follows:

where bi is the distance decay coefficient of BS at metro station i. xti is the t-th explanatory variable in the metro station catchment i. βt and β0 are the coefficient to be estimated and the intercept term, respectively, and θi indicates the random residual.

If a high correlation exists among explanatory variables, it can compromise model stability and interpretability. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) serves as a diagnostic statistic that assesses the extent of multicollinearity present within the set of independent variables. The generally accepted thresholds are as follows:

- When 0 < VIF ≤ 5, it is typically considered to indicate no multicollinearity;

- When 5 < VIF ≤ 10, there is a suggestion of weak multicollinearity;

- When 10 < VIF ≤ 100, there is strong multicollinearity;

- When VIF > 100, this signifies severe multicollinearity.

3.2.2. Geographic Weighted Regression

Since the OLSR model is global, its estimated coefficients for factors remain identical and constant across the entire range. The potential differences in local impacts have not been fully revealed. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the spatial autocorrelation of the distance delay coefficient using Moran’s I test to determine whether to further adopt the Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) method for analysis.

Spatial autocorrelation is defined as the systematic variation in a variable across geographic space, indicating that attribute values at nearby locations tend to cluster together [15]. Moran’s I is a commonly used indicator for testing spatial autocorrelation, and its value serves as a basis for making a judgment on whether to use the spatial local regression model. The equation expression is as follows:

where I is Moran’s Index. N is the total number samples. ωmn is the element of the spatial weight matrix. xₘ is the variable of sample m, and xn is the variable value of sample n. The value range of Moran’s I is [−1, 1]: values less than 0 indicate negative spatial autocorrelation, values greater than 0 indicate positive spatial autocorrelation, and a value of 0 indicates no spatial autocorrelation. Usually, the standardized Z-statistic is used to test the significance of spatial autocorrelation: when Z ≥ 2.58 or Z ≤ −2.58, it means that the spatial autocorrelation is statistically significant.

GWR is a powerful spatial analysis method that performs excellently in detecting local variations [16]. The fitted coefficients of each local impact factor can be estimated, rather than a global estimate. The mathematical formula of GWR is as follows:

where (ui, vi) is the coordinate of i. β0(ui, vi) is the intercept of i, and βt(ui, vi) is the t-th regression coefficient of i.

3.2.3. Random Forest Regression

To address the complex nonlinear effects that built environment factors on the distance decay coefficients of BS connection, this study introduces the RFR machine learning algorithm. Proposed by Leo Breiman [13], the model’s enhanced robustness stems from its ensemble learning framework that constructs numerous decision trees to perform tasks. This approach effectively mitigates the risk of overfitting while being capable of fully uncovering implicit patterns within large-sample datasets.

The Random Forest consists of a large number of decision trees. During the growth of each decision tree, the criterion for node splitting is selecting the feature that can maximally reduce node impurity. The importance level of a feature is the sum of the impurity reductions brought about by the nodes that split using this feature across all decision trees in the entire forest. The higher this value, the more critical the role this feature plays in model prediction, and the more important it is for explaining changes in the dependent variable.

The construction and evaluation of the RFR model were conducted in a Python 3.6.2 environment, and the model performance was comprehensively evaluated using three indicators: Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and coefficient of determination (R2). Subsequently, the importance level of factors influencing the distance decay coefficient was evaluated.

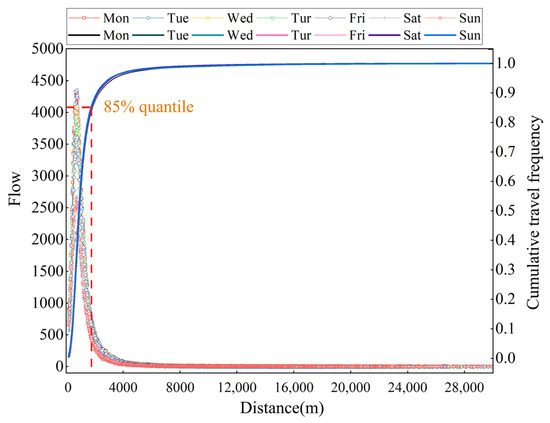

4. Extracting the Influence Variables

Using BS trip data, the distance distribution of BS connections at all metro stations was derived. As shown in the dot-line plot in Figure 4, the daily connection flow at all stations of the week is presented. The flow on weekdays is approximately similar, while the flow on weekends is significantly lower compared to weekdays. The smooth curve in the figure represents the cumulative travel frequency curve, indicating the percentage of trips with connection distances shorter than the corresponding value relative to the total flow. The cumulative travel frequency curves for each day of the week are highly similar, and the connection flow exhibits a distinct decay characteristic beyond a certain distance. In order to determine the metro catchment range, this paper chooses the 85th quantile connection distance of the metro station as the riding radius [17]. The built environment impact variables were extracted on the basis of 85th quantile station catchments.

Figure 4.

Connection distance frequency distribution.

Built environment attributes, encompassing public transit networks (i.e., bus and metro lines) and demographic metrics, are widely recognized as critical determinants influencing BS travel behavior. Based on the established premise that employment and residential activities constitute the fundamental drivers of trip generation, the respective population densities were selected as explanatory variables for this study. Furthermore, as transportation networks serve as the essential infrastructure underpinning accessible travel, three key topological metrics (degree centrality, closeness centrality, and betweenness centrality) were extracted from both metro and bus networks based on complex network theory. To assess the structural properties of the public transit networks, three centrality measures were adopted. Degree centrality captures a node’s local connection intensity. Betweenness centrality evaluates a node’s role as an intermediary in the shortest paths, highlighting its influence on network throughput. Closeness centrality gauges a node’s overall proximity to all others based on the average shortest-path distance. The extraction of impact factors can be referred to our previous study [18]. The description of all variable indicators is in Table 1.

Table 1.

The descriptive parameters of factors.

5. Results

The distance decay coefficient and the built environment impact factors have been extracted. Subsequently, a multivariate regression model was employed to model the relationship between the decay coefficient and impact factors.

5.1. Distance Decay Characteristics of BS

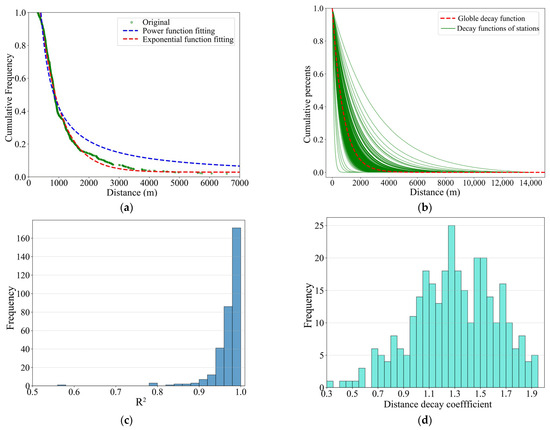

Take one station as an example, the exponential function outperforms the power function in terms of average R2 (0.9888 vs. 0.9341). As illustrated in Figure 5a, the green circular scatter points represent the distribution of cumulative trip percentage against corresponding access distance, while the red dashed and blue lines denote the exponential function fitting and power function fitting, respectively. Therefore, the exponential function is employed to model the distance decay characteristics of shared bicycle trips accessing metro stations. In Figure 5a, the data point (1000, 0.7) indicates that 70% of BS trips used for metro access in this area exceed 1000 m.

Figure 5.

The characteristics of connection distance decay. (a) the fitting of distance decay function, (b) decay fitting of station connection distance, (c) the R-squared value of the distance decay function, (d) the distribution of distance decay coefficient.

Figure 5b shows the distance decay patterns of BS access trips across different metro stations. The distribution patterns of access distances vary notably among stations, with significantly different decay rates observed in the cumulative frequency curves. The red line in the figure represents the globally fitted distance decay function, which has a global decay coefficient of 1.2974 and a goodness-of-fit (R2) of 0.9140. A larger decay coefficient indicates a stronger influence of access distance on travel demand. This suggests that BS are primarily used for short-distance travel, and as distance increases, users’ willingness to choose BS decreases more markedly.

Figure 5c,d present the statistical distributions of the goodness-of-fit (R2) and distance decay coefficients estimated for all stations, respectively. Notably, 98% of the stations exhibit an R2 greater than 0.85, indicating that the exponential function effectively captures the decay pattern of BS travel distances. The values of the distance decay coefficient conform to a Gaussian distribution, clustering within the range of 0.4 to 2.

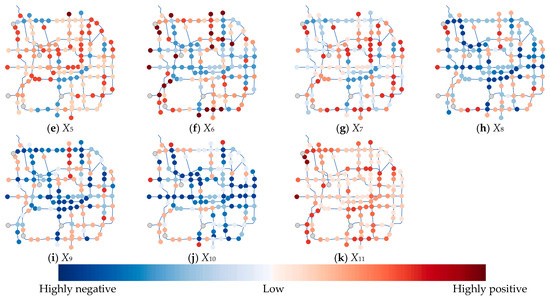

To test for spatial dependence, the global Moran’s I index was applied to the distance decay coefficients. The significant result (Moran’s I = 0.199, z-score = 10.282, p-value = 0.000) indicates a clear pattern of spatial clustering. As shown in Figure 6, in the spatial dimension, the distance decay coefficients in the main urban area exhibit a more pronounced decrease with increasing distance compared to suburban areas. This spatial pattern can be attributed to the substantially higher land use intensity and mixture in Beijing’s central urban areas compared to suburban and rural regions. The dense urban fabric enables residents to access various services within short distances. Meanwhile, the city center has a high-density public transportation network, providing more convenient access to metro and bus services for reaching diverse destinations. Consequently, travelers tend to use public transport to reach metro stations near their destinations, followed by BS or walking for the final leg of their journeys, resulting in a higher proportion of short-distance BS trips. Furthermore, this disparity reveals underlying relationships between distance decay in BS usage and the built environment across different urban contexts.

Figure 6.

Geographical distribution of distance attenuation coefficient.

5.2. OLSR of Variables

Prior to regression analysis, VIF was employed to examine multicollinearity among the independent variables. The test results indicated that all 11 variables had VIF values below 5, suggesting no significant multicollinearity issues. The multiple linear regression results presented in Table 2 reveal that explanatory variables X1 (Adjacency distance of metro stations), X2 (Adjacency distance of bus stations), and X3 (Number of bus lines) significantly influence the distance decay coefficient (Y). The adjusted R2 of 0.649 indicates that these three variables collectively explain 64.9% of the variance in distance decay coefficients across different station areas.

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression results.

The regression results demonstrate negative correlations between the distance decay coefficient and all three predictors: X1, X2, and X3. This indicates that greater distances to the nearest metro station or bus stop are associated with smaller decay coefficients. This relationship can be explained by the fact that longer access distances to public transit reduce travelers’ sensitivity to distance decay when using BSs for feeder trips. Similarly, a higher number of bus routes in a station catchment enables travelers to use BSs for accessing bus stops, thereby resulting in smaller decay coefficients.

5.3. GWR of Variables

The OLSR models the relationship between variables and the BS access distance decay from a global perspective. However, the statistically significant Moran’s I verifies the existence of spatial dependence in the distance decay, indicating that its variation is influenced not only by the built environment of the focal station area but also by that of the surrounding areas. Thus, the GWR approach was implemented to capture the potential spatial non-stationarity in the relationships between built environment variables and the distance decay coefficient. The results show that the correlation coefficients for X2 (Adjacency distance of the bus stations) and X3 (Number of bus lines) are 61.29% and 45.57%, respectively. There is no significant spatial variation between the distance decay coefficient and X12 (Functional mixing degree). The GWR model degenerates into a global least squares regression, resulting in the failure of bandwidth selection. In Table 3, we provide quantitative summaries of GWR’s spatial heterogeneity. For each key factor, we report the range of local coefficients, the percentage of stations with positive/negative effects across all stations. For example, X1 shows negative coefficients in 73.08% of stations (range: −0.0006 to 0.0003), indicating a predominantly negative effect on distance decay. The delay coefficients of all stations are negatively correlated with X2.

Table 3.

GWR Local Coefficients.

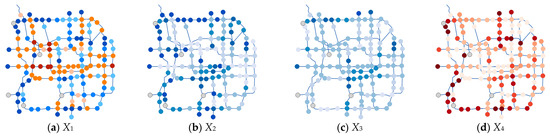

Figure 7 presents the regression results of the GWR model. In the figure, red and blue colors indicate positive and negative influences of the factors on the distance decay coefficient of BS usage, respectively. The intensity of the color corresponds to the magnitude of the influence. The results clearly reveal distinct geographical variations in how these factors affect the distance decay. As shown in Figure 7a, the adjacency distance to metro stations exhibits a positive correlation with the distance decay coefficient for most Line 1 stations, while demonstrating a negative influence in areas such as the northwestern Fourth Ring Road. This spatial heterogeneity can be attributed to distinct built environment characteristics: the areas along the central axis are predominantly high-density developments where cycling demand is reduced, whereas near scenic spots and university zones, cycling preference increases. The higher road network density in these areas enhances cycling accessibility, resulting in a smaller distance decay coefficient of BS access as the distance to metro stations increases. In Figure 7b, a negative correlation is observed between the adjacency distance to bus stops and the access distance decay coefficient. Notably, this negative association is particularly pronounced around scenic areas such as the Forbidden City and near university campuses. Both types of areas feature well-defined internal accessibility needs (e.g., to specific attraction entrances or campus gates). While bus stops generally serve the purpose of “reaching the vicinity”, BSs effectively fulfill the last-mile demand for “reaching precise destinations”. Consequently, the sensitivity of access distance to bus stop proximity is significantly reduced in these contexts. In Figure 7c, the number of bus lines was inversely associated with the access distance decay coefficient. This relationship can be attributed to two main factors. First, bus stops with a high density of routes typically function as regional transportation hubs, offering extensive aerial coverage. For last-mile accessibility, BSs effectively bridge the gap from these hub stations to specific final destinations. Second, bus stops with a high density of lines are typically supported by densely distributed bicycle-sharing parking facilities. This configuration creates a virtuous cycle of “high passenger flow prompting high vehicle supply”, which further reduces the perceived cost of using BSs. As a result, users show a greater willingness to choose cycling even for relatively longer access distances.

Figure 7.

Spatial heterogeneity effects of the built environments on BS distance decay.

Figure 7d–f present the spatially heterogeneous correlations between the metro network node degree and the access distance decay coefficient. Figure 7d reveals a positive correlation between the degree centrality of metro network nodes and the access distance decay coefficient. For instance, some stations on the southern section of Line 10 primarily serve residential areas. The stronger the hub functionality of a station, the greater its attractiveness as a metro destination, consequently increasing passengers’ preference for using BSs as an access mode to access these stations. Figure 7e demonstrates a locally negative correlation between the betweenness centrality of metro network nodes and the distance decay coefficient. This phenomenon can be primarily attributed to policy interventions, such as the establishment of BS restricted zones near Zhushikou Street. These restrictions lengthen the actual access distance, thereby attenuating the distance decay effect. Figure 7f indicates a predominantly negative correlation between the closeness centrality of metro network nodes and the distance decay coefficient. This pattern can be attributed to the interplay between high functional diversity and short-distance modal competition. Major hubs such as Xizhimen and Jianguomen stations are integrated with mixed-use developments that combine office, commercial, and residential functions. This configuration allows the majority of daily destinations to be accessible within a five-minute walk from the station, thereby diminishing the competitiveness of shared bicycles for ultra-short-distance trips.

Figure 7g–i illustrate the spatially heterogeneous correlations between the node degree of the bus network within metro station areas and the access distance decay coefficient. Figure 7g reveals a predominantly positive correlation between the degree centrality of the bus network nodes and the access distance decay coefficient at stations along the North and East Second Ring Roads. This phenomenon can be primarily attributed to an imbalance in road space allocation. Despite the high density of bus routes in these areas, limited road capacity has led to the encroachment of bus stops upon bicycle lanes, consequently compressing the available cycling space. As a result, BSs primarily serve short-distance access needs in these congested corridors. Figure 7h,i show a negative correlation between the betweenness/closeness centrality of the bus network notes and the access distance decay coefficient in the Qianmen and Temple of Heaven areas. This pattern occurs because the high density of bus lines around these scenic spots provides multiple transit options to reach well-defined destinations. The access distance becomes less sensitive to a specific bus stop.

Figure 7j illustrates the spatially heterogeneous correlation between residential population density within metro station catchments and the access distance decay coefficient. The results indicate negative correlation coefficients for the majority of stations, suggesting that residents in high-density areas exhibit strong reliance on metro commuting, with shared bicycles serving as an essential “last-mile” solution. Even under unfavorable road network conditions, residents still tolerate medium-to-long cycling distances due to this travel demand. Figure 7k shows the spatially heterogeneous correlation between workplace population density in metro station catchments and the access distance decay coefficient. The results reveal a positive correlation, indicating that a higher density of workplace population is associated with a larger distance decay coefficient. This suggests that commuters using BSs for trips with workplaces as either their origin or destination are more sensitive to travel time costs. Furthermore, the pedestrian and bicycle-friendly environment typically found around many workplaces further encourages the use of BSs, leading to greater travel demand.

5.4. RFR of Variables

The OLSR model described above globally captures the relationship between influencing variables and the distance decay coefficient, with a goodness-of-fit of 64.9%. However, nine factors did not pass the significance test, indicating their limited explanatory power in the global model. Following the validation of spatial autocorrelation, the Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) method revealed spatial heterogeneity in how various variables influence the distance decay coefficient. To further capture the complex nonlinear relationships between multidimensional influencing variables and the access distance decay coefficient, this section employs a Random Forest model.

Using stratified sampling, the data were allocated to training, validation, and test sets at a ratio of 70:15:15, respectively, with the aim of preserving the inherent spatial structure of the distance decay coefficients. The number of random forest decision trees is 500, and the tree depth is 10. The results demonstrate strong predictive performance:

Table 4 presents the feature importance ranking based on impurity reduction, revealing that the adjacency distance of the bus stations is the most influential factor, followed by the number of bus routes and the adjacency distance of the metro stations. This finding aligns closely with the results obtained from the multiple linear regression analysis. Additionally, it quantifies the importance of each predictor, including factors that were insignificant in the linear model.

Table 4.

Feature importance ranking based on impurity.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

Taking Beijing as a case study, this paper empirically reveals the spatial heterogeneity in the distance decay of BS access to metro stations and its relationship with the built environment. The findings provide significant implications for comprehensively understanding the spatial interactions of shared bicycles, supporting sustainable urban planning, and promoting bicycle-sharing integration across diverse urban contexts. The main conclusions are as follows:

Based on multi-source datasets, BS trips accessing metro stations were extracted. Distance decay functions were fitted for stations, with 98% of them achieving a goodness-of-fit above 0.85.

From a global perspective, the OLSR model was constructed to examine the relationship between built environment factors and the BS access distance decay coefficient. The results demonstrate that three variables (adjacency distance of metro stations, adjacency distance of bus stations, and number of bus lines) exhibit statistically significant negative correlations with the coefficient. This finding confirms that short-distance BS usage as a feeder mode is strongly associated with the convenience of public transportation services.

The GWR model was employed to investigate the spatial variations in how influencing factors affect the BS access distance decay coefficient. The results reveal significant spatial heterogeneity in the magnitude and direction of these effects. Furthermore, detailed empirical explanations were provided to interpret the varying impacts of different factors across geographical contexts.

The RF algorithm was applied to analyze the nonlinear relationships between influencing factors and the access distance decay coefficient, achieving a goodness-of-fit (R2) of 0.8032. The feature importance ranking derived from the model identifies adjacency distance of bus stations as the most influential factor, followed by the number of bus lines and adjacency distance of metro stations.

The spatial heterogeneity of BS access distance decay at metro stations reveals the close relationship between metro access mode choice and urban spatial interactions. This finding indicates that BS dispatch and rebalancing operations require customized models tailored to the specific characteristics of different urban spaces. The research outcomes will facilitate accurate prediction of bicycle-sharing demand, systematic planning of designated parking areas, and rational allocation of bicycle resources. These insights provide practical support for optimizing BS utilization rates.

However, this study still has some limitations that need to be further expanded in future research. Firstly, the distance decay characteristics for BS access may vary depending on trip purposes (e.g., commuting vs. leisure) and exhibit distinct spatial patterns. Secondly, the entropy method employed to quantify the land use mix has inherent limitations, as it does not fully account for the spatial configuration of different land use types or the scale of the analysis zones. More advanced methods for quantifying the distribution characteristic of interest points could be added in future work. Last but not least, this study did not classify metro stations by type (such as scenic spots, residential areas, and workplaces) to summarize the BS distance decay laws for the same type of stations, which will be addressed in subsequent research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C. and Y.W.; methodology, T.C.; software, H.S.; validation, Y.C., T.C. and H.S.; formal analysis, T.C. and Y.W.; investigation, Y.W. and X.W.; resources, Y.C.; data curation, T.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C. and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, H.S.; visualization, X.W.; supervision, Y.C.; project administration, X.W. and H.S.; funding acquisition, X.W. and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. ZR2025QC430) and Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. ZR2024QD186).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data, models, or code generated or used during the study are proprietary or confidential in nature and may only be provided with restrictions. (1) shared bicycle data: The data is in cooperation with Beijing transportation system, and our permission is only allowed to deploy the algorithm on their data platform and calculate the results. Meanwhile, the data cannot be token out. Therefore, this data is provided with restrictions. (2) Indicators extraction algorithm: This related codes are available from the corresponding author if requested.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Chen, W.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Mi, Z.; Zhu, D.; Liu, G. Characterizing the stocks, flows, and carbon impact of dockless sharing bikes in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 162, 105038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Ni, Y. Effects of Dockless Bike on Modal Shift in Metro Commuting: A Pilot Study in Shanghai. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board 97th Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 7–11 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tobler, W. A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Econ. Geogr. 1970, 46, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Fang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yin, L.; Li, J.; Lu, S. Spatial heterogeneity in spatial interaction of human movements-Insights from large-scale mobile positioning data. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 78, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Collins, J. Estimating road network accessibility during a hurricane evacuation: A case study of hurricane Irma in Florida. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 85, 102334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Yang, Y.; Li, A.; Qu, X. Spatial heterogeneity in distance decay of using bike sharing: An empirical large-scale analysis in Shanghai. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 94, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacono, M.; Krizek, K.; El-Geneidy, A. Access to Destinations: How Close Is Close Enough? Estimating Accurate Distance Decay Functions for Multiple Modes and Different Purposes; Minnesota Department of Transportation: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yasmin, F.; Larsen, J.; El-Geneidy, A. Examining travel distances by walking and cycling, Montréal, Canada. In Proceedings of the 89th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC, USA, 10–14 January 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, Z.; Cai, H. Understanding bike sharing travel patterns: An analysis of trip data from eight cities. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2019, 515, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Huang, Y.; Axhausen, K.W. An approach to imputing destination activities for inclusion in measures of bicycle accessibility. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 82, 102566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, M.; Huang, W.; Zhang, C.; Yan, X.; Zheng, J. Quantitative analysis of the relationships between dockless bike sharing and public transport: A trip-level perspective. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 190, 104277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsdon, C.; Fotheringham, A.S.; Charlton, M.E. Geographically weighted regression: A method for exploring spatial nonstationarity. Geogr. Anal. 1996, 28, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Li, W.; Peeta, S. Predicting Station-Level Bike-Sharing Demands Using Graph Convolutional Neural Network. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.08723. [Google Scholar]

- Mahato, R.; Htike, K.; Sornlorm, K.; Koro, A.B.; Kafle, A.; Sharma, V. A spatial autocorrelation analysis of road traffic accidents by severity using Moran’s I spatial statistics: A study from Nepal 2019–2022. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Lin, R. Spatial-temporal heterogeneity of air pollution: The relationship between built environment and on-road PM2.5 at micro scale. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 76, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, S.; Dong, J.; Wu, J. Exploring the spatial variations of transfer distances between dockless bike-sharing systems and metros. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 92, 103032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, J. Efficiency Assessment of Transit-Oriented Development Focusing on the 500-m Core Catchment of Metro Stations Based on the Concept of a Metro Microcenter in Beijing. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2023, 149, 04023117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).