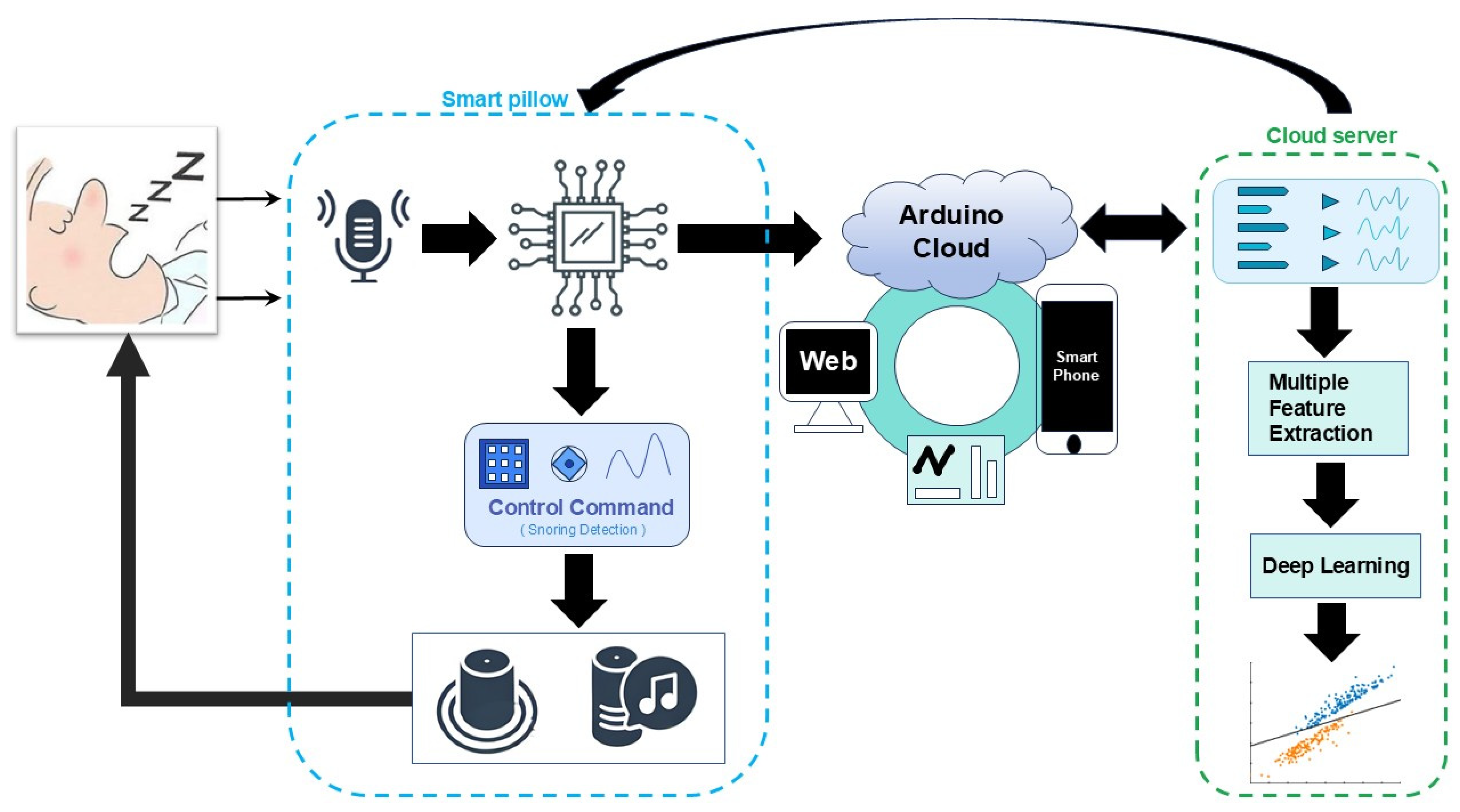

An IoT-Enabled Smart Pillow with Multi-Spectrum Deep Learning Model for Real-Time Snoring Detection and Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

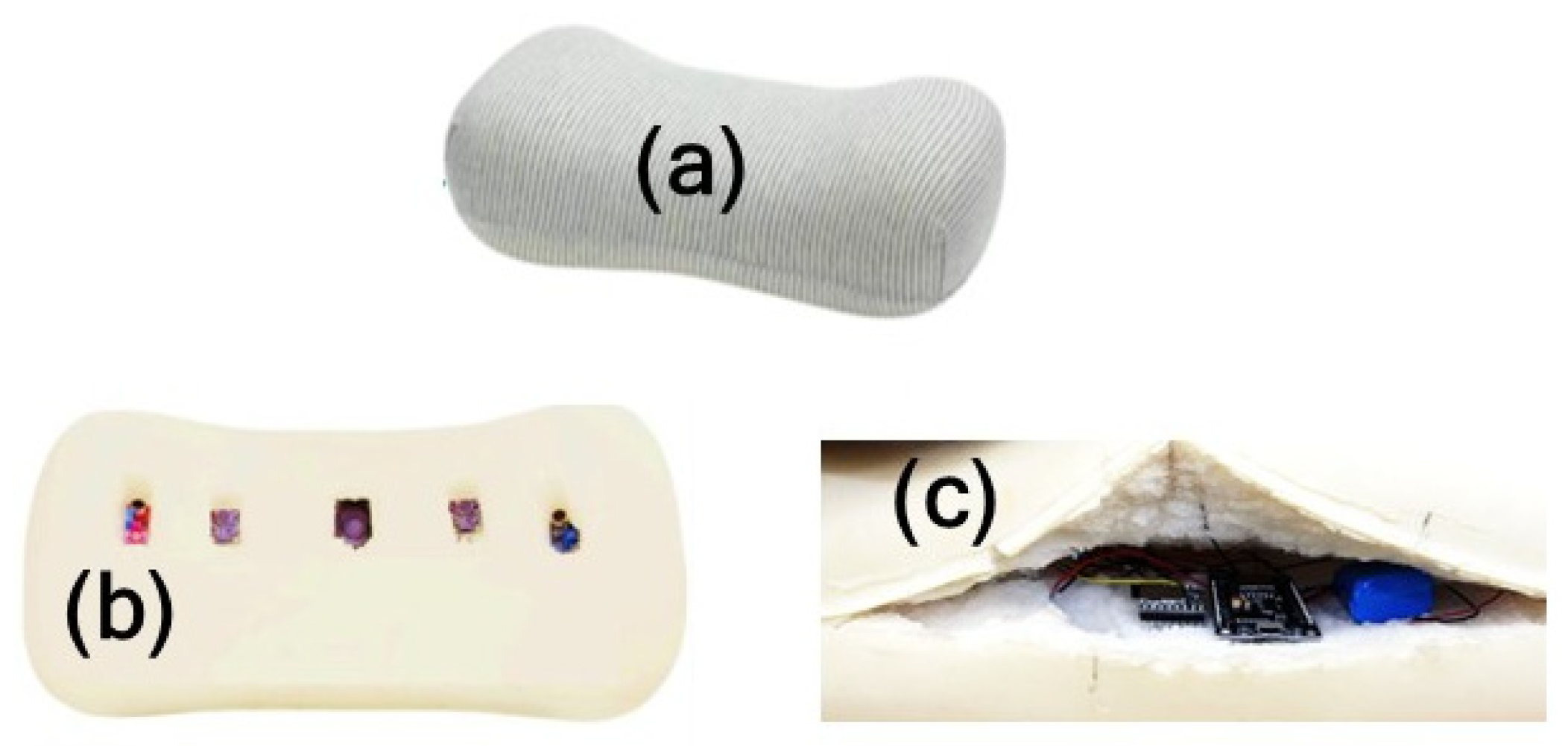

3.1. Smart Pillow

3.2. Arduino Cloud

3.3. Cloud Server

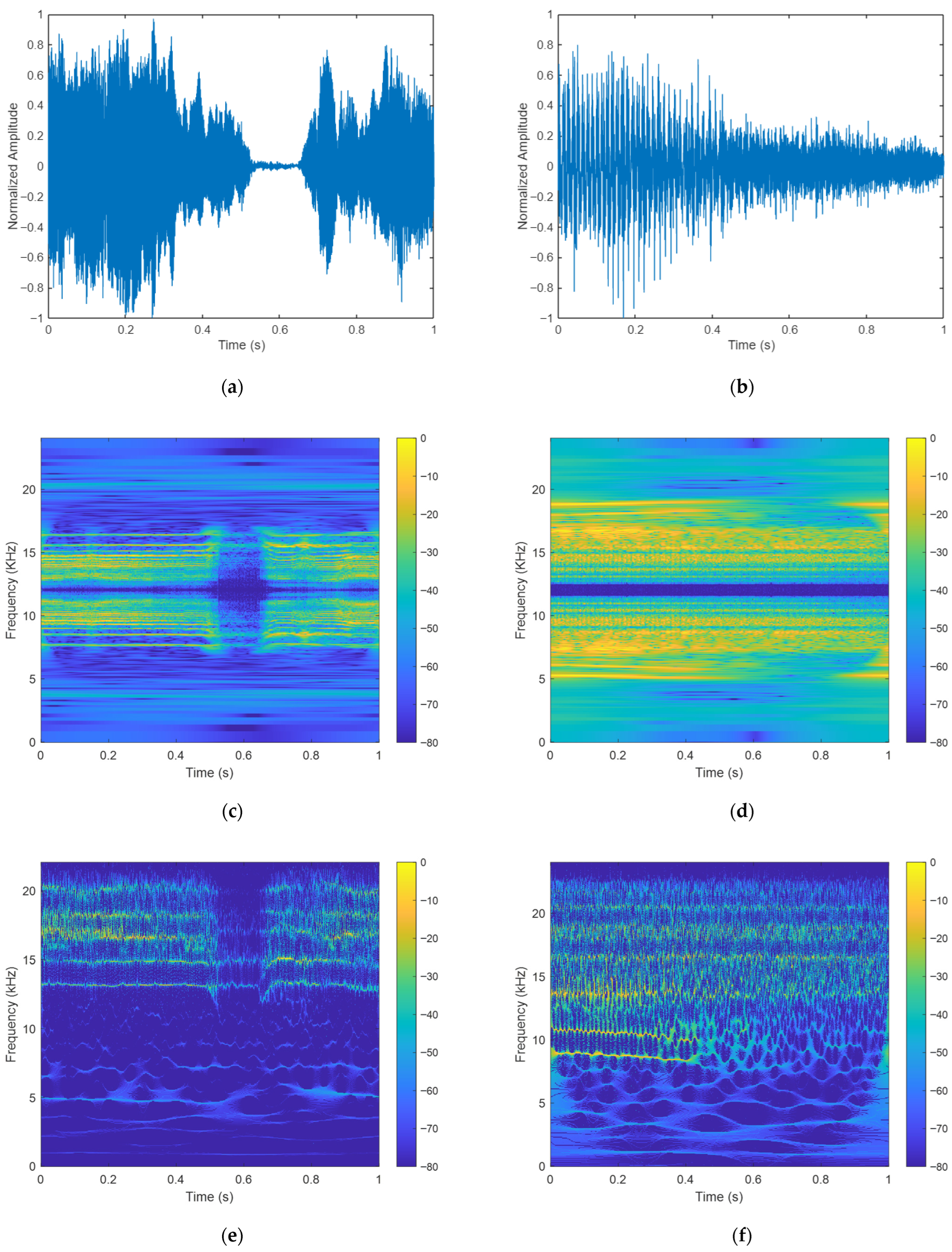

3.3.1. Data Processing

- CQT was originally developed for music analysis, as the human auditory system perceives pitch on a logarithmic rather than linear scale. By maintaining a constant quality factor across all spectral bins, the CQT allocates frequency channels that increase in absolute Hertz width while preserving a fixed relative bandwidth. The quality factor (Q) is defined [37]:

- 2.

- SWT [38] is a re-assignment-based technique that sharpens the classical Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT). It achieves this by collapsing energy exclusively along the frequency dimension, while leaving the time axis unaltered. The objective is to transform the blurred CWT scalogram into a sparse, invertible time–frequency representation. This representation can accurately trace the instantaneous frequency (IF) of each oscillatory component.

- 3.

- The HHT is a data-driven, adaptive time–frequency analysis method introduced by Huang et al. [39] specifically designed for analyzing nonlinear and non-stationary signals. Unlike traditional transforms that rely on predefined basis functions (e.g., FT or CWT), the HHT decomposes a signal into a finite set of Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) using a process called Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD). Each IMF represents a simple oscillatory mode embedded in the data, satisfying two conditions:

- The number of extrema and zero-crossings must either be equal or differ by at most one.

- The mean value of the upper and lower envelopes defined by local maxima and minima is zero at any point.

3.3.2. Deep Learning Framework

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

3.5. Dataset

4. Results

4.1. Prototype System

4.2. Experimental Environment

4.3. Results of CQT, SWT, and HHT

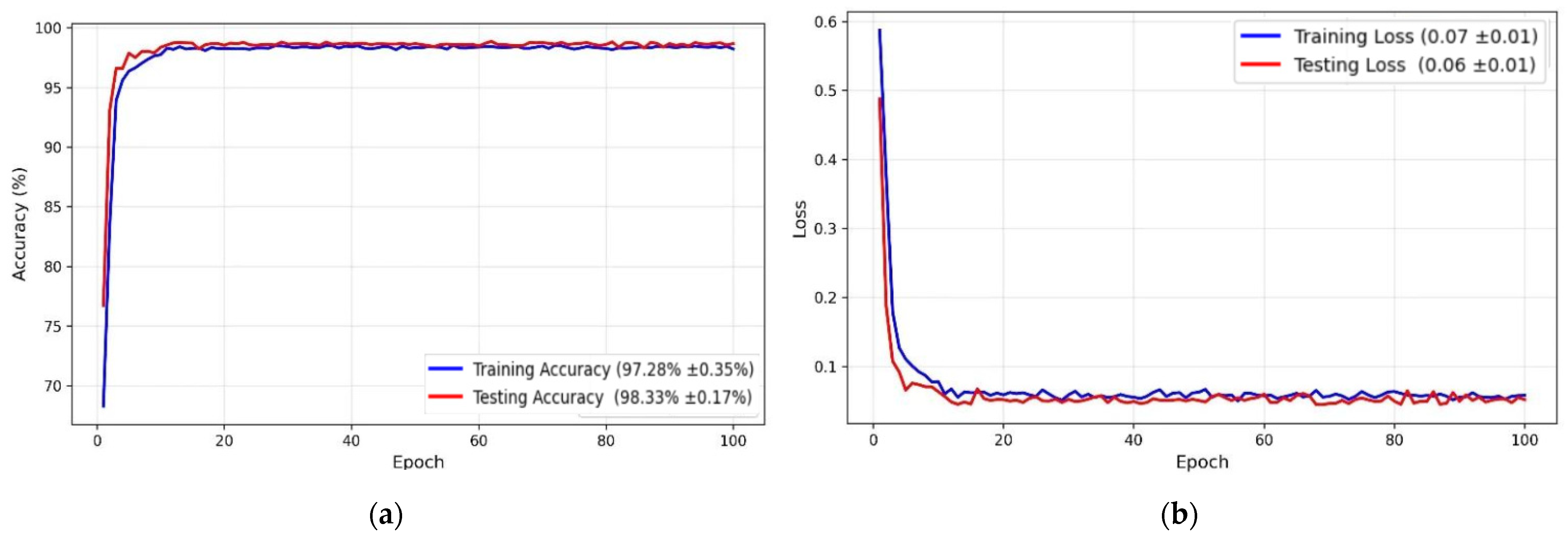

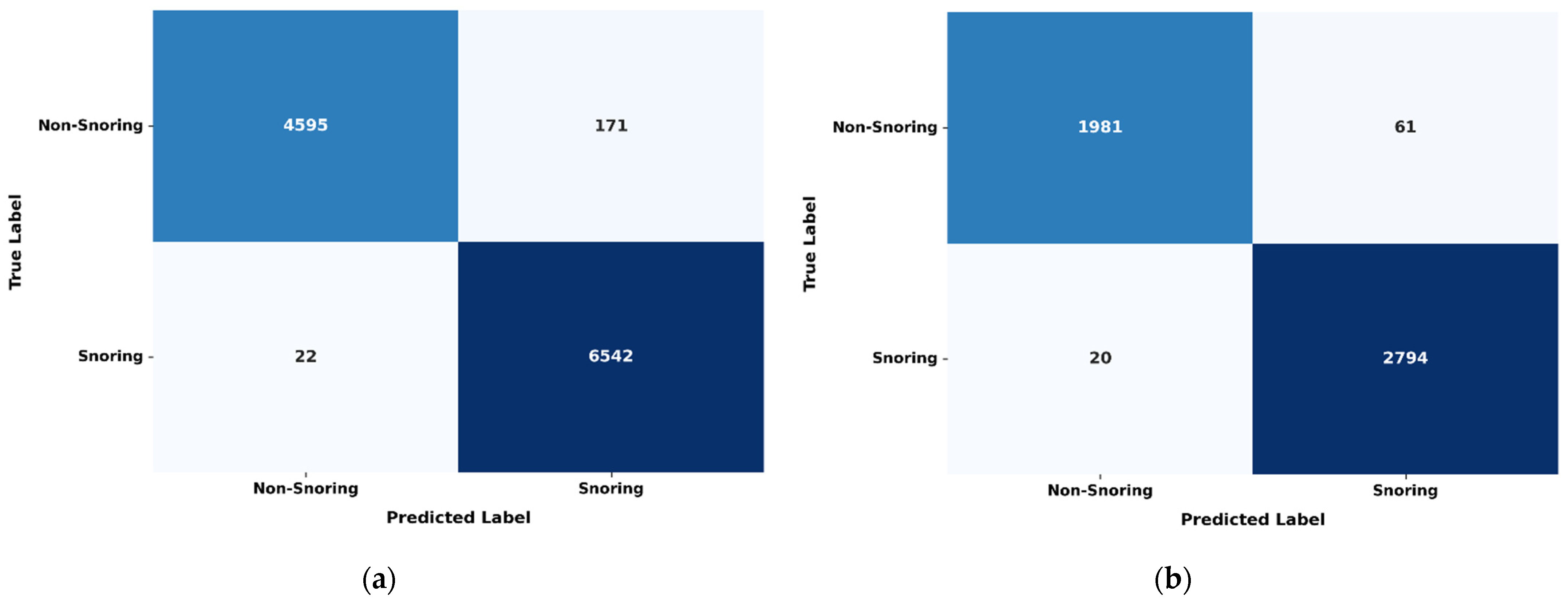

4.4. Deep Learning Model Performance Evaluation

5. Discussion

5.1. Feature Performance Evaluation

5.2. Comparison with Other Studies

5.3. Limitations

- Cost-effectiveness: Hardware costs under USD 8 including two microphones, two vibration motors, a speaker, an SD card module, an ESP8266 off-shelf board, and a 5000 mAh battery.

- High accuracy: Integration of temporal–spatial features with our modified PSCN model yields classification accuracy exceeding 98%.

- Secure cloud storage: Historical data stored on Arduino cloud is accessible by authorized personnels for post hoc clinical diagnosis and treatment.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Molina, G.G.; Chellamuthu, V.; Gorski, B.; Siyahjani, F.; Babaeizadeh, S.; Mushtaq, F.; Mills, R.; McGhee, L.; DeFranco, S.; Aloia, M. 0325 Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Associations Through the Lens of a Smart Bed Platform. Sleep 2024, 47, A139–A140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaratna, C.V.; Perret, J.L.; Lodge, C.J.; Lowe, A.J.; Campbell, B.E.; Matheson, M.C.; Hamilton, G.S.; Dharmage, S.C. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2017, 34, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ayas, N.; Laher, I. A narrative review on obstructive sleep apnea in China: A sleeping giant in disease pathology. Heart Mind 2022, 6, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppard, P.E.; Young, T.; Barnet, J.H.; Palta, M.; Hagen, E.W.; Hla, K.M. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 177, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.S.; McSharry, D.G.; Malhotra, A. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet 2014, 383, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.C.; Afreixo, V.; Cravo, J. Impact of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Treatment on Marital Relationships: Sleeping Together Again? Cureus 2023, 15, e46513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, R.B.; Brooks, R.; Gamaldo, C.E.; Harding, S.M.; Marcus, C.; Vaughn, B.V. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Darien, IL, USA, 2012; Volume 176, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhan, P.; Ditthapron, A.; Banluesombatkul, N.; Wilaiprasitporn, T. Deep Neural Networks with Weighted Averaged Overnight Airflow Features for Sleep Apnea–Hypopnea Severity Classification. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2018—IEEE Region 10 Conference, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 28–31 October 2018; pp. 441–445. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, Z.; Gao, J.; Lin, L.; Liu, Z.; Wu, H.; Liu, F.; Yao, R. Automatic detection of obstructive sleep apnea events using a deep CNN-LSTM model. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 2021, 5594733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Wong, K.K.; Rowsell, L.; Don, G.W.; Yee, B.J.; Grunstein, R.R. Predicting response to oxygen therapy in obstructive sleep apnoea patients using a 10-minute daytime test. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 51, 1701587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-Y.; Wu, H.-T.; Hsu, C.-A.; Huang, P.-C.; Huang, Y.-H.; Lo, Y.-L. Sleep Apnea Detection Based on Thoracic and Abdominal Movement Signals of Wearable Piezoelectric Bands. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2016, 21, 1533–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutta, S.; Cheng, Q. Modeling of oxygen saturation and respiration for sleep apnea detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 50th Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 6–9 November 2016; pp. 1636–1640. [Google Scholar]

- Zarei, A.; Asl, B.M. Automatic detection of obstructive sleep apnea using wavelet transform and entropy-based features from single-lead ECG signal. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2018, 23, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Kan, C.; Yang, H. Heterogeneous recurrence analysis of heartbeat dynamics for the identification of sleep apnea events. Comput. Biol. Med. 2016, 75, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urtnasan, E.; Park, J.-U.; Joo, E.-Y.; Lee, K.-J. Automated detection of obstructive sleep apnea events from a single-lead electrocardiogram using a convolutional neural network. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappalà, P.; Lentini, M.; Ronsivalle, S.; Lavalle, S.; La Via, L.; Maniaci, A. The Global Socioeconomic Burden of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Comprehensive Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.S.; Abdallah, M.B.; Bashir, Z.; Khalife, W. Heart Failure Beyond the Diagnosis: A Narrative Review of Patients’ Perspectives on Daily Life and Challenges. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wu, D.J.; Coates, A.; Ng, A.Y. End-to-End Text Recognition with Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR 2012), Tsukuba, Japan, 11–15 November 2012; pp. 3304–3308. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Hamid, O.; Mohamed, A.-r.; Jiang, H.; Penn, G. Applying Convolutional Neural Networks Concepts to Hybrid NN-HMM Model for Speech Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP 2012), Kyoto, Japan, 25–30 March 2012; pp. 4277–4280. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banluesombatkul, N.; Ouppaphan, P.; Leelaarporn, P.; Lakhan, P.; Chaitusaney, B.; Jaimchariyatam, N.; Chuangsuwanich, E.; Chen, W.; Phan, H.; Dilokthanakul, N. MetaSleepLearner: A Pilot Study on Fast Adaptation of Bio-Signals-Based Sleep Stage Classifier to New Individual Subjects Using Meta-Learning. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020, 25, 1949–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilleminault, C.; Winkle, R.; Connolly, S.; Melvin, K.; Tilkian, A. Cyclical variation of the heart rate in sleep apnoea syndrome: Mechanisms, and usefulness of 24 h electrocardiography as a screening technique. Lancet 1984, 323, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhang, X. Automatic snoring sounds detection from sleep sounds based on deep learning. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2020, 43, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T. A deep learning model for snoring detection and vibration notification using a smart wearable gadget. Electronics 2019, 8, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Janott, C.; Pandit, V.; Zhang, Z.; Heiser, C.; Hohenhorst, W.; Herzog, M.; Hemmert, W.; Schuller, B. Classification of the excitation location of snore sounds in the upper airway by acoustic multifeature analysis. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 64, 1731–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhao, S.; Deng, D. Improving OSAHS prevention based on multidimensional feature analysis of snoring. Electronics 2023, 12, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, P.; Ding, B.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Z. Ultra-wideband radar detection based on target response and time reversal. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 14750–14762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Fu, X.; Ge, C.; Cao, C.; Zha, Z.-J. Towards generalized uav object detection: A novel perspective from frequency domain disentanglement. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2024, 132, 5410–5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Wang, X.; Zhan, Y. Environmental sound classification algorithm based on region joint signal analysis feature and boosting ensemble learning. Electronics 2022, 11, 3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadem, S.P. Traditional Methods in Edge, Corner and Boundary Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.07714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibisono, J.K.; Hang, H.-M. Traditional Method Inspired Deep Neural Network for Edge Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP 2020), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 25–28 October 2020; pp. 678–682. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Xiang, A. Research on Edge Detection of LiDAR Images Based on Artificial Intelligence Technology. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.09773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamout, Y.; Yeasar, T.S.; Iqbal, S.; Zulkernine, M. Beyond smart homes: An in-depth analysis of smart aging care system security. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, S.S.; Mendonça, F.; Ravelo-García, A.G.; Morgado-Dias, F. A systematic review of detecting sleep apnea using deep learning. Sensors 2019, 19, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, S.K.; Rajaguru, H.; Won, D.-O. Coherent Feature Extraction with Swarm Intelligence Based Hybrid Adaboost Weighted ELM Classification for Snoring Sound Classification. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Mawla, M.; Chaccour, K.; Fares, H. A novel enhancement approach following MVMD and NMF separation of complex snoring signals. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 71, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liao, J.; Zhang, W.; Dai, J.; Huang, C.; Li, H.; Yu, H. Graph Convolutional Network Based on CQT Spectrogram for Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Machines 2024, 12, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Liu, B.; Liu, G.; Wang, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Forced oscillation source location of bulk power systems using synchrosqueezing wavelet transform. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 6689–6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.E.; Shen, Z.; Long, S.R.; Wu, M.C.; Shih, H.H.; Zheng, Q.; Yen, N.-C.; Tung, C.C.; Liu, H.H. The empirical mode decomposition and the Hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1998, 454, 903–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, G.; Wang, C.; Cascioli, V.; McCarthy, P.W. Unobtrusive Sleep Posture Detection Using a Smart Bed Mattress with Optimally Distributed Triaxial Accelerometer Array and Parallel Convolutional Spatiotemporal Network. Sensors 2025, 25, 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckitt, W.; Tuomi, S.; Niesler, T. Automatic detection, segmentation and assessment of snoring from ambient acoustic data. Physiol. Meas. 2006, 27, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusoglu, M.; Kamasak, M.; Erogul, O.; Ciloglu, T.; Serinagaoglu, Y.; Akcam, T. An efficient method for snore/nonsnore classification of sleep sounds. Physiol. Meas. 2007, 28, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azarbarzin, A.; Moussavi, Z.M. Automatic and unsupervised snore sound extraction from respiratory sound signals. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 58, 1156–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penagos, H.P.; Mahecha, E.M.; Camargo, A.M.; Jimenez, E.S.; Sarmiento, D.A.C.; Salazar, S.V.H. Detection, recognition and transmission of snoring signals by ESP32. Meas. Sens. 2024, 36, 101397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafna, E.; Tarasiuk, A.; Zigel, Y. Automatic detection of whole night snoring events using non-contact microphone. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnkar, V.R.; Abeyratne, U.R.; Sharan, R.V. Automatic picking of snore events from overnight breath sound recordings. In Proceedings of the 2017 39th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Jeju Island, Repulic of Korea, 11–15 July 2017; pp. 2822–2825. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenali, B.; van Dijk, J.; Ouweltjes, O.; den Brinker, B.; Pevernagie, D.; Krijn, R.; van Gilst, M.; Overeem, S. Recurrent neural network for classification of snoring and non-snoring sound events. In Proceedings of the 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 18–21 July 2018; pp. 328–331. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.; Cho, J. Unconstrained snoring detection using a smartphone during ordinary sleep. Biomed. Eng. Online 2014, 13, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Aubert, X.; Long, X.; van Dijk, J.; Arsenali, B.; Fonseca, P.; Overeem, S. Audio-based snore detection using deep neural networks. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 200, 105917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, Y.-P.; Chuang, H.-H.; Lo, Y.-L.; Huang, S.-Y.; Zhan, W.-T.; Lee, G.-S.; Li, H.-Y.; Shyu, L.-Y.; Lee, L.-A. Automated sleep apnea detection from snoring and carotid pulse signals using an innovative neck wearable piezoelectric sensor. Measurement 2025, 242, 116102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.T.; Lee, M.T.; Ku, M.C.; Yang, K.C.; Wei, C.Y. Efficacy of a smart antisnore pillow in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Behav. Neurol. 2021, 2021, 8824011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| References | Strengths | Key Metrics | Weaknesses |

| Banluesombatkul et al. [21] | A novel MAML*-based meta sleep learner; Adapt sleep-stage classification to new individuals with minimal labeled data; Reduce clinician workload; Support human–machine collaboration; Provide interpretability through layer-wise relevance propagation. | A statistically significant 5.4–17.7% performance improvement over traditional deep learning-based methods (e.g., CNN* and RNN*) | Require substantial computational resources and lengthy training; Exhibit reduced accuracy for REM* stage, lack validation on real-world clinical datasets; Employ a simplified CNN architecture; Demonstrate limited generalization across diverse populations. |

| Zhang et al. [9] | Integrates CNN and LSTM* to automatically detect OSA* events from single-lead ECG*; Eliminate handcrafted features; Capture spatial and temporal ECG patterns effectively; Enable reliable real-time apnea detection for portable monitoring applications. | Accuracy: 96.1% Sensitivity: 96.1% Specificity: 96.2% | Restricted to OSA and normal event detection (excluding hypopnea); Exhibit reduced performance on noisy and transition epochs; Remain unvalidated across diverse clinical datasets or real-world environments. |

| Guilleminault et al. [22] | CVHR* provides a robust, physiologically grounded biomarker for non-invasive ECG/Holter-based screening of moderate-to-severe sleep-disordered breathing; Detect clinically significant events without full PSG*. | Not applicable | Night-to-night variability; Limited sensitivity for mild apnea/hypopnea; Reduced accuracy with noisy/ectopic ecgs or comorbid cardiac conditions. |

| Jiang et al. [23] | Employ CNN-based deep learning for automated snoring detection from sleep audio; Achieve high accuracy; noise robustness, and minimal manual feature extraction; Demonstrate strong potential for non-invasive sleep monitoring. | Accuracy: 95.07% Sensitivity: 95.42% Specificity: 95.82% | Limited dataset diversity and size; Overfitting to controlled laboratory conditions; Degraded performance in real-world noisy environments or with mixed sound sources; Insufficient validation across diverse populations and device types. |

| Khan [24] | Present a complete, low-cost CNN-based snoring detection and prevention system; Integrate a wearable vibration actuator, acoustic sensor module, and smartphone app; Low-power, real-time operation. | Accuracy: 96% | Small and non-clinical dataset; No long-term validation; Limited generalizability. |

| Participants | Age (Years) | Height (cm) | Body Mass (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 11) | 26.0 ± 5.0 | 176.6 ± 3.1 | 84.8 ± 12.9 |

| Female (n = 3) | 36.0 ± 18.7 | 161.7 ± 9.0 | 72.3 ± 19.7 |

| Overall (n = 14) | 28.1 ± 9.6 | 173.4 ± 7.8 | 82.1 ± 14.7 |

| Feature Type | Accuracy [%] | Sensitivity [%] | Precision [%] | Recall [%] | F1-Score [%] | Running Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CQT | 98.15 | 99.06 | 98.04 | 98.43 | 98.23 | 0.12 |

| HHT | 96.80 | 97.37 | 96.87 | 97.21 | 97.04 | 0.20 |

| SWT | 98.14 | 98.73 | 98.24 | 98.21 | 98.22 | 0.24 |

| CQT + HHT | 98.35 | 99.02 | 98.40 | 98.47 | 98.43 | 0.25 |

| CQT + SWT | 98.22 | 99.42 | 98.21 | 98.36 | 98.28 | 0.30 |

| HHT + SWT | 98.12 | 99.31 | 98.07 | 98.38 | 98.22 | 0.37 |

| CQT + HHT + SWT | 98.33 | 99.29 | 98.34 | 98.30 | 98.32 | 0.43 |

| References | Classifiers | Feature | Hardware | Experiment | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiang et al. [23] | CNN–LSTM–DNN | Spectrum, Spectrogram, Mel-spectrogram, and CQT | A microphone (RODE, NTG-3, Sydney, Australia) and a digital audio recorder (Rowland R-44, Roland Corporation, Hamamatsu, Japan) | 15 participants (11 patients diagnosed with sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome and 4 simple snorers) | 95.07% | 95.42% | 95.82% |

| Khan [24] | CNN | MFCC | nRF52832 Feather board (Adafruit Industries LLC, New York City, NY, USA), Raspberry Pi (Sony UK Technology Centre, Pencoed, Bridgend, UK). | 1000 samples; vibration on the arm to prevent snoring | 96% | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| Duckitt et al. [41] | Hidden Markov model | Spectral features | Carol Sigma Plus 5 condenser microphone (Taiwan Carol Electronics Co., Ltd, Taichung, Taiwan) | 6 subjects, 1.5 h from each subject, 1 h for training, 0.5 h for testing | 82–89% | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| Cavusoglu et al. [42] | Robust logistic regression | MFCC | Sennheiser condenser microphone (Sennheiser electronic GmbH & Co. KG, Wedemark, Germany) | Full-night recordings from 18 simple snorers and 12 OSA patients | Simple snorer: 97.3% OSA patients: 90.2% Mixed (simple snorer + OSA patients): 86.8% | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| Azarbarzin et al. [43] | Unsupervised fuzzy C-means clustering | Principal component analysis | Tracheal microphone, ambient microphone | A short period of the entire night recording of 30 participants | Tracheal microphone: 98.6% Ambient microphone: 93.1% | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| Penagos et al. [44] | YAMMET | Matlab AudioTool Box (Wiener and parametric EQ filters to remove noise) spectrograms and periodograms for graph display statistical values (maxima, minima, average and standard deviation), powers and entropies as features | INMP441 MEMS microphone (InvenSense, San Jose, CA, USA), ESP32 Board (Espressif Systems, Shenzhen, China) | 23 potential snoring sounds | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| Dafna et al. [45] | AdaBoost classifier | Time-related features and spectral-related features (127 features) | Directional condenser microphone | Full night recordings from 67 subjects (42 for validation) | 98.4%; | 98.1% | 98.2% |

| Swarnkar et al. [46] | Artificial Neural Network | Repetitive packets of energy | Microphone and computerized data-acquisition system | Full night recordings from 34 subjects, 21 subjects for training, 13 subjects for testing | 86–89% | 82–87% | 87–89% |

| Arsenali et al. [47] | Recurrent neural network | MFCC | A field recorder (Zoom Corpora-tion, Tokyo, Japan) and a non-contact microphone (Studiocare Profes-sional Audio Ltd. Liverpool, UK) | Part of full night recordings from 20 subjects (11 for training, 3 for validation, and 6 for testing) | 95% | 92% | 98% |

| Shin et al. [48] | Quadratic classifier | Autoregressive model and the local maximum of the spectral density | GT-I9300 (Galaxy S3™) microphone (Samsung Electronics, Suwon, Republic of Korea) | 44 snoring datasets and 75 noise datasets | 95.07% | 98.58% | 94.62% |

| Xie et al. [49] | CNN + RNN | CQT and spectrogram | Two types of microphones: Earthworks M23 (Earthworks Inc. Milford, NH, USA) and Behringer ECM8000 (Behringer, Zhoushan, China); placement of five microphones: Two microphones above a subject’s head, another two on the left/right side of the bed, and the fifth placed on the bedside table | Full night recording from 38 subjects | 95.3 ± 0.5% | 92.2 ± 0.9% | 97.7 ± 0.4% |

| Chao et al. [50] | Traditional Linear Regression (TLR) Automatic Linear Regression (ALR) Categorical Regression (CR) with LASSO | From snoring vibration signal: Snoring index; Snore duration and interval; Duration and interval variance; Snoring vibration energy; From carotid pulse signal: Pulse rate; Standard deviation. | Advanced piezoelectric sensor (NPS, Eleceram Technology Co., Ltd., Taoyuan, Taiwan), PSG Alice system (Philips Respironics, MA, USA), Portable digital sound recorder (Sony PCM-D50, PCM-D50, Sony Electronics Inc., Tokyo, Japan), Data acquisition card (USB-6008, National Instruments Corporation, Austin, TX, USA) | Simultaneous overnight recording using NPS, in-lab PSG, and snoring sound analysis in a controlled sleep laboratory from 29 patients with Sleep Apnea Syndrome (SAS) | 85–90% | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| Our work | Modified PCSN | CQT, HHT, SWT | sound Sensors, ESP8266 off-shelf board (Tensilica Xtensa LX106, Shenzhen Guiyuanjing Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), vibration motors, a speaker | 14 participants and downloaded snoring/non-snoring sound; Real-time detection and gentle haptic/sound feedback | 98.33% | 99.29% | 98.34% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Perin, K.K.O.; Li, G.; Wang, J.; He, T.; Xu, Y.; McCarthy, P.W. An IoT-Enabled Smart Pillow with Multi-Spectrum Deep Learning Model for Real-Time Snoring Detection and Intervention. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12891. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412891

Liu Z, Perin KKO, Li G, Wang J, He T, Xu Y, McCarthy PW. An IoT-Enabled Smart Pillow with Multi-Spectrum Deep Learning Model for Real-Time Snoring Detection and Intervention. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12891. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412891

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhuofu, Kotchoni K. O. Perin, Gaohan Li, Jian Wang, Tian He, Yuewen Xu, and Peter W. McCarthy. 2025. "An IoT-Enabled Smart Pillow with Multi-Spectrum Deep Learning Model for Real-Time Snoring Detection and Intervention" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12891. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412891

APA StyleLiu, Z., Perin, K. K. O., Li, G., Wang, J., He, T., Xu, Y., & McCarthy, P. W. (2025). An IoT-Enabled Smart Pillow with Multi-Spectrum Deep Learning Model for Real-Time Snoring Detection and Intervention. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12891. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412891