Abstract

Background: The ability to perform simultaneous tasks, such as walking while engaging in cognitive or secondary motor activities, is crucial for autonomy post-stroke but is often impaired. Exercise-based interventions may improve dual-task gait performance. Methods: A systematic review following PRISMA 2020 guidelines (PROSPERO CRD420251082293) searched six databases for RCTs published between January 2017 and June 2025, including adults post-stroke receiving exercise-based interventions, with dual-task gait speed as the primary outcome. Data extraction and methodological quality assessment (PEDro scale) were conducted independently. A narrative synthesis was used due to heterogeneity in interventions and outcomes. Results: Seven RCTs (248 participants, 4–15 weeks) were included. Six studies reported statistically significant within-group improvements in dual-task gait speed (0.05–0.31 m/s), whereas one study showed no change. Between-group comparisons were largely inconsistent, with only one study indicating superiority of dual-task over single-task training. Methodological quality ranged from fair to good (PEDro 5–8/10). No serious adverse events were reported. Conclusions: Exercise-based interventions appear safe and can improve dual-task gait speed post-stroke. Evidence supporting the superiority of dual-task over single-task training remains inconclusive. Clinical application should consider individual goals, baseline performance, and cognitive-motor capacity. Future research should focus on larger, high-quality RCTs, standardized protocols, and clinically meaningful thresholds for dual-task gait speed.

1. Introduction

The ability to perform simultaneous tasks, including walking, is fundamental for autonomy and functional independence in daily life [,,,,,]. Following stroke, this capacity is frequently impaired, resulting in significant activity limitations and an increased risk of falls [,,,]. Post-stroke falls arise not only from motor and balance deficits but also from cognitive impairments that compromise safe ambulation [,,,]. Consequently, restoring the ability to manage concurrent motor and cognitive demands during gait is a central objective of neurorehabilitation. Interventions are often personalized to enhance motor control and motor learning through targeted dual-task practice [,,,].

Gait speed is a widely accepted clinical outcome in stroke rehabilitation. It reflects functional mobility, community ambulation potential, and health-related quality of life [,]. Notably, gait speed assessed under dual-task conditions often differs from single-task performance, providing a more accurate reflection of real-world walking demands for stroke survivors []. In addition to absolute gait speed measures, relative metrics such as dual-task cost (DTC) and dual-task effect (DTE) provide further insight into an individual’s ability to manage simultaneous motor and cognitive demands. Although conceptually distinct, both quantify the impact of the added task on gait performance and offer a more nuanced assessment of dual-task interference []. Standardized functional tests, such as the 10 Meter Walk Test, provide objective quantification of dual-task performance, highlighting the impact of concurrent cognitive or motor demands on gait []. Recent advances in gait analysis, including machine learning approaches for pattern recognition, have further demonstrated clinical feasibility for monitoring and optimizing individualized interventions []. Therefore, interventions aiming to improve dual-task gait speed are of particular clinical relevance [,,,].

A variety of exercise-based interventions have been proposed to enhance gait speed and dual-task performance post-stroke. These include treadmill training (often combined with virtual reality), targeted dual-task programs integrating cognitive or secondary motor tasks during walking, progressive strength training, and multimodal functional training simulating daily activities [,,,,,,,,,]. Personalizing dual-task practice according to an individual’s motor and cognitive profile may enhance gait automaticity and facilitate transfer to complex real-life tasks, supporting functional independence and quality of life []. However, variability across trials persists regarding intervention content, dosage, and outcome measures [,,,].

Previous systematic reviews have explored the effects of exercise and gait-training interventions on gait speed after stroke [,,,,]. Many, however, focused primarily on single-task outcomes, limiting their applicability to real-world walking scenarios [,]. Plummer and Iyigün [] examined exercise-based effects on dual-task gait speed, reporting promising yet inconclusive results. The present review updates and expands previous work by incorporating recently published randomized trials and by examining contemporary interventions such as cognitive-motor dual-task training and C-Mill-based therapy, which reflect ongoing advances in clinical practice and rehabilitation research.

Given the growing number of RCTs investigating task-oriented and cognitive-motor training post-stroke [,,,,,,], an updated synthesis focusing exclusively on RCTs and dual-task gait speed is warranted. This approach mitigates variability stemming from study design and thereby enhances causal inference regarding intervention effects [,]. Focusing on randomized evidence clarifies clinical implications and informs guideline development [,,].

Accordingly, this review systematically identifies RCTs evaluating therapeutic interventions on gait speed under dual-task walking conditions in adults with stroke. Its objectives are to (1) summarize the characteristics of eligible RCTs, including population, intervention, comparator, and outcomes; (2) quantify intervention effects on dual-task gait speed where data permit; and (3) examine sources of heterogeneity, considering intervention type (e.g., dual-task training versus other exercise modalities), duration, and outcome measurement procedures [,].

By concentrating on randomized evidence and dual-task outcomes, this review aims to provide clinicians and researchers with a clearer understanding of which exercise-based approaches most consistently improve dual-task gait speed post-stroke, while identifying knowledge gaps to guide future trials [].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Formulation of the Research Question and Search Strategy

This systematic review was designed according to the PICOS framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study design). The research question addressed the effects of exercise-based interventions on dual-task gait speed (primary outcome) and dual-task cost/effect (secondary outcome) in adults with post-stroke sequelae.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across six electronic databases: PubMed, Web of Science, PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database), CINAHL Complete, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Scopus, with the last search performed on 25 June 2025. Search strategies were tailored for each database: in PubMed, MeSH terms were complemented with title/abstract keywords; in Web of Science, the TS field was used; in PEDro, the internal clinical trial filter applied the terms “dual task AND gait speed AND stroke.” Equivalent strategies were adapted for CINAHL, Cochrane, and Scopus. A detailed, line-by-line example of the Web of Science strategy is provided in Appendix A.

This review adhered to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [,], with the complete checklist available in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. To ensure transparency and reproducibility, the protocol was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (CRD420251082293).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they met all of the following criteria:

- Population: adults with post-stroke sequelae;

- Intervention: any exercise-based intervention;

- Comparison: any other exercise-based intervention;

- Outcome: gait speed under dual-task conditions (primary outcome, mandatory) and dual-task cost/effect (secondary outcome, if reported);

- Study design: RCTs adhering to PEDro methodological standards [,,,,,];

- Publication: full-text articles in English or Portuguese, published from January 2017 onward.

Exclusion criteria were:

- Neurological conditions other than stroke;

- Dual-task assessment restricted to static balance;

- Animal studies;

- Retracted or withdrawn publications.

The temporal restriction aimed to capture recent evidence reflecting contemporary rehabilitation approaches and emerging RCTs, ensuring the review included the most up-to-date randomized trials relevant to current clinical practice.

2.3. Study Selection

References were exported and duplicates removed using EndNote Basic (Online). Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two pairs of reviewers, with discrepancies resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. Full-text articles were then assessed for eligibility. No semi-automated or AI-assisted screening tools were used.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data extraction was independently performed by both reviewer pairs using a predefined standardized form. Extracted data included study characteristics and participant information, intervention details, outcome measures, and assessment instruments. The extraction form was piloted to ensure consistency. No automated tools were applied.

2.5. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was gait speed under dual-task conditions, a clinically validated measure of functional mobility in post-stroke individuals [,,,]. The secondary outcome was dual-task cost/effect, representing the relative change in gait performance induced by an additional cognitive or motor task, providing insight into the individual’s capacity to manage simultaneous demands []. Validated assessment instruments included: Ten-Meter Walk Test with cognitive component, Two-Minute Walk Test with cognitive distraction, walking while performing the Stroop task, and other established dual-task protocols [,,,,,,].

No changes were made to predefined outcomes during the review.

2.6. Data Synthesis

All gait speed values were converted to meters per second (m/s) for consistency, while dual-task cost/effect measures were reported as percentages (%). Data synthesis included pre- vs. post-intervention, post-intervention vs. follow-up, and between-group comparisons for both primary (dual-task gait speed) and secondary (dual-task cost/effect) outcomes. Due to substantial heterogeneity in intervention type, duration, intensity, outcome measurement, follow-up periods, and participant characteristics, a formal meta-analysis was not feasible. A descriptive, quantitative, and narrative synthesis was conducted to evaluate trends and interpret the clinical relevance of the reported outcomes []. For calculating the mean difference and the respective CI between groups, the online calculator provided at https://www.statskingdom.com/difference-confidence-interval-calculator.html was used (accessed on 1 September 2025).

2.7. Presentation of Results

Results were summarized in comparative tables to facilitate side-by-side analysis of interventions, including primary and secondary outcomes, sample sizes, means, standard deviations, mean differences, and 95% confidence intervals.

2.8. Narrative Synthesis

The narrative synthesis focused on:

- Direction of effect: identifying which intervention was associated with superior outcomes;

- Magnitude of effect: evaluating the size of observed differences.

Methodological heterogeneity and variations in outcome measures were explicitly acknowledged, with consideration of both methodological quality and clinical relevance [].

2.9. Sensitivity Analysis

The potential influence of studies with lower methodological quality was explored narratively, considering studies with lower PEDro scores or lacking allocation concealment. No formal recalculation was performed.

2.10. Risk of Bias and Methodological Quality Assessment

A qualitative assessment of risk of bias related to missing data was independently conducted by two reviewers, with no major concerns identified. Methodological quality was assessed using the Portuguese version [] of the PEDro scale [,,,,]. Scores range from 0 to 10, with 9–10 indicating excellent, 6–8 good, 4–5 fair, and ≤3 poor quality. Assessment covered eligibility criteria, randomization, allocation concealment, baseline comparability, blinding, follow-up, intention-to-treat analysis, between-group comparisons, and reporting of variability.

Certainty of evidence was evaluated narratively, considering risk of bias, consistency of results, precision, effect magnitude, and clinical applicability for both dual-task gait speed and dual-task cost/effect. No formal grading system or automated tool was applied.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection Process

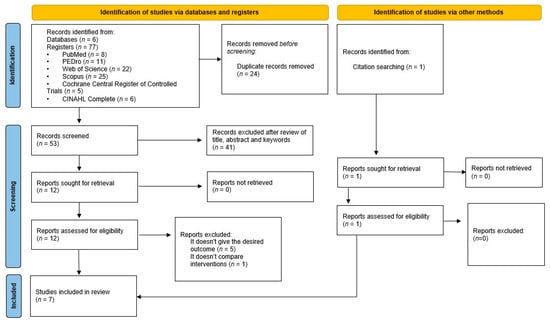

The search strategy identified 77 studies across six electronic databases: PubMed, Web of Science, PEDro, Scopus, CINAHL Complete, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. After removing duplicates, 53 studies were screened by title and abstract, resulting in 41 exclusions for not meeting the predefined eligibility criteria. Among the 13 full-text articles assessed, six were excluded because they either did not report the outcomes of interest or did not include a comparison between interventions, with one of the 13 studies having been identified through citation searching.

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram summarizing identification, screening, and inclusion. All searches were conducted between January 2017 and 25 June 2025, ensuring a comprehensive coverage of recent literature.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrating the study selection process from electronic databases, registers, and other sources.

3.2. Methodological Quality of Studies

Methodological quality, assessed using the PEDro scale, ranged from 5 to 8 points (maximum of 10). All studies met the criteria for random allocation (Item 2), baseline comparability between groups (Item 4), availability of outcome data for at least 85% of participants (Item 8), and reporting of point estimates with measures of variability (Item 11).

Criteria 5 (blinding of subjects) and 6 (blinding of therapists) were not met in any of the studies, reflecting the intrinsic challenges of implementing blinding in physiotherapy trials, where participants are aware of the treatment received and therapists cannot be blinded to the intervention delivered [].

Concealed allocation (Item 3), assessor blinding (Item 7), intention-to-treat analysis (Item 9), and reporting of between-group comparisons (Item 10) were inconsistently applied across studies. Only the trial by Liu et al. [] demonstrated fair methodological quality (PEDro = 5/10), while all others were rated as having good methodological quality. The detailed PEDro item scores for each study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Risk of bias assessment of included studies using the PEDro scale.

3.3. Study Characteristics

The seven randomized controlled trials included a total of 248 participants, with considerable variability in sample size, sex distribution, and stroke type (Table 2). Across studies, dual-task gait speed was assessed using heterogeneous protocols, including 4 m, 4.3 m, and 10 m walk tests, as well as the two-minute walk test combined with cognitive tasks such as verbal fluency, Stroop interference, serial-three subtraction, daily life questions, and task-switching paradigms (Table 2). Walking speed was measured with different systems, ranging from stopwatch timing to OptoGait (Microgate Srl, Bolzano, Italy), GAITRite (CIR system, Inc., Havertown, PA, USA), and LEGSys™ (Biosensics, Cambridge, MA, USA)/Qualisys Motion Capture System (Gothenburg, Sweden).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies and participants.

Intervention duration ranged from 4 to 15 weeks, with the number of sessions varying between 10 and 30 and session length ranging from 30 to 90 min (Table 3). The structure and complexity of dual-task interventions differed markedly, including treadmill-based cognitive-motor training, multimodal balance and gait programmes, overground gait training with cognitive or motor tasks, C-Mill adaptability therapy, and mixed aerobic–resistance protocols.

Table 3.

Detailed description of physical exercise and dual-task interventions included in the reviewed studies.

Four studies included follow-up assessments after the intervention period, ranging from 4 to 52 weeks: 4 weeks [], 5 weeks [], 11 weeks [] and 52 weeks [].

Substantial heterogeneity was observed in several methodological dimensions—intervention modality, cognitive task type, progression strategies, training dose, and measurement instruments for dual-task gait speed. This diversity precluded meaningful data pooling and justified the decision to employ a narrative synthesis rather than a quantitative meta-analysis.

3.4. Study Analysis

Individual trial results are summarized in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, providing a comprehensive overview of pre- and post-intervention changes, dual-task cost/effect, and post-intervention follow-up outcomes.

Table 4.

Pre- and post-intervention outcomes from the included studies: dual-task gait speed.

Table 5.

Pre- and post-intervention outcomes from the included studies: dual-task cost/effect.

Table 6.

Post-intervention and follow-up outcomes from the included studies: dual-task gait speed.

3.4.1. Within-Group Analyses

Six of the seven included RCTs reported statistically significant improvements in gait speed under dual-task conditions following the intervention (Table 4). Only Liu et al. [] did not show statistically significant change in any intervention group. Antonio et al. [] reported improvements in the experimental group (Mixed Physical Exercise with Dual-Task: pre 0.76 ± 0.33 m/s, post 1.07 ± 0.43 m/s, mean difference 0.31) but not in the control group (Mixed Physical Exercise Single-Task: pre 1.01 ± 0.35 m/s, post 1.27 ± 0.33 m/s, mean difference 0.26; not statistically significant). Baek et al. [] found significant improvements for both dual-task and single-task groups, with slightly higher gains in the dual-task group (dual-task: pre 0.35 ± 0.13 m/s, post 0.44 ± 0.13 m/s; single-task: pre 0.34 ± 0.18 m/s, post 0.39 ± 0.18 m/s). Chuang et al. [] reported significant increases in gait speed for both dual-task and single-task groups across two dual-task conditions (10 m walk with Stroop task and serial-three subtraction task), with dual-task mean differences ranging from 0.05 to 0.10 m/s and single-task mean differences ranging from 0.05 to 0.06 m/s. Liu et al. [] showed non-significant changes in all intervention groups (Cognitive Dual-Task, Motor Dual-Task, and Conventional Physical Therapy), with mean differences between −0.02 and 0.069 m/s. Meester et al. [] observed small but statistically significant improvements in dual-task (0.048 m/s) and single-task (0.035 m/s) treadmill training groups. Plummer et al. [] reported variable improvements depending on the dual-task condition: dual-task groups showed mean differences ranging from 0.03 to 0.05 m/s, while single-task groups ranged from 0.07 to 0.08 m/s. Notably, in this study, some of the dual-task comparisons did not reach statistical significance, reflecting variability between conditions (Stroop vs. Clock; fast vs. preferred walking speed). Timmermans et al. [] reported an overall improvement in dual-task gait speed when averaging both intervention arms, but did not provide separate results for each group.

Within-group analyses of dual-task cost/effect (Table 5) show that several interventions led to meaningful changes in dual-task performance. Antonio et al. [] reported a substantial reduction in dual-task cost for the dual-task group (pre 47.67 ± 91.53%, post 13.88 ± 47.40%, mean difference −33.79%), whereas the single-task group showed a smaller, non-significant decrease (−7.28%). Baek et al. [] found significant reductions in dual-task cost for both dual-task (−11.10%) and single-task (−4.52%) groups. Chuang et al. [] observed significant increases in dual-task effect for the dual-task groups in both Stroop (10.15%) and serial-three subtraction conditions (6.22%), while single-task groups showed non-significant changes (2.58% and 0.81%, respectively). Liu et al. [] demonstrated a significant within-group improvement in cognitive dual-task cost (6.9%), whereas motor dual-task and conventional therapy groups showed minimal changes (1.1% and 1.4%, respectively). Meester et al. [] reported small non-significant within-group reductions in dual-task effect for dual-task (−2.40%) and single-task (−2.90%) treadmill training. For Plummer et al. [] and Timmermans et al. [] it was not possible to extract mean and standard deviation data for dual-task cost/effect.

3.4.2. Between-Group Comparisons

Comparisons between single-task and dual-task training for gait speed revealed heterogeneous results. Only Baek et al. [] reported a statistically significant between-group difference favoring dual-task training (0.04 m/s, 95% CI [0.01, 0.08]). In all other studies, between-group comparisons were not statistically significant.

Comparisons between single-task and dual-task training for dual-task cost/effect showed that two studies reported statistically significant between-group differences favoring dual-task interventions. Specifically, Baek et al. [] showed a significant reduction in dual-task cost for the dual-task group compared with single-task training (−6.28%, 95% CI [−12.01, −0.56]). Chuang et al. [] reported significant between-group differences in dual-task effect for both the Stroop task (8.48%, 95% CI [2.42, 14.54]) and the serial-three subtraction task (6.12%, 95% CI [0.29, 11.95]), favoring dual-task training. In all other studies, between-group comparisons were non-significant or not reported, indicating no clear superiority of dual-task over single-task interventions.

3.4.3. Follow-Up Assessments

Four studies reported follow-up assessments after the intervention (Table 6). Within-group changes in gait speed from post-intervention to follow-up were generally small, ranging from −0.10 to 0.05 m/s. It was not possible to verify whether these differences reached statistical significance in the original studies. Between-group differences at follow-up were minimal, with only Meester et al. [] reporting a statistically significant difference favoring dual-task training (0.048 m/s, 95% CI [0.011, 0.085]).

3.4.4. Influence of Methodological Quality

A qualitative sensitivity assessment suggests that the robustness of reported improvements may be influenced by study quality. Excluding Meester et al. [], the only study without allocation concealment, slightly attenuated observed trends, whereas excluding Liu et al. [], the only study with a PEDro score below 6, amplified apparent statistical significance. No formal statistical recalculation was performed; these observations should therefore be interpreted as indicative rather than confirmatory.

3.5. Narrative Analysis of the Data

Risk of Bias. The methodological assessment of the included studies (Table 1) indicated moderate to good quality, with PEDro scores ranging from 5 to 8/10. Common limitations included the lack of participant and therapist blinding, inconsistent allocation concealment and assessor blinding, infrequent use of intention-to-treat analyses, and inconsistent reporting of between-group comparisons.

Consistency of Results. Across the seven RCTs, within-group analyses generally demonstrated improvements in dual-task gait speed, with mean differences ranging approximately from 0.05 to 0.31 m/s (Table 4). Liu et al. [] reported no significant within-group change. Between-group comparisons of single-task versus dual-task interventions were variable: Baek et al. [] observed significant improvements favouring dual-task training, whereas the remaining studies did not identify significant between-group differences.

Precision of Estimates. Several studies reported wide or unreported confidence intervals for mean differences. Small sample sizes and variability in measurement methods further limited the precision of effect estimates.

Magnitude of Effects. Within-group improvements in dual-task gait speed ranged from 0.05 to 0.31 m/s. Significant between-group effects were observed only in Baek et al. [] (Table 4). The largest within-group change reported across studies was 0.31 m/s [].

Clinical Applicability. All interventions were reported as safe, with no adverse events documented. Functional improvements in dual-task gait speed were observed across several interventions. Protocols varied in type, duration, intensity, and follow-up (Table 2 and Table 3), with both dual-task and single-task training approaches successfully implemented in clinical settings.

4. Discussion

Six of the seven randomized controlled trials included in this review reported statistically significant improvements in dual-task gait speed following intervention, with within-group mean differences ranging approximately from 0.05 to 0.31 m/s [,,,,,]. Only Baek et al. [] identified a significant advantage of dual-task intervention compared to single-task training, while the remaining studies did not demonstrate statistically significant between-group differences [,,,,,]. Liu et al. [] observed no relevant gains in either group, and Antonio et al. [] reported improvements were limited to the experimental group. Taken together, the findings indicate that the relative efficacy of dual-task interventions remains uncertain, with evidence suggesting that individuals with lower baseline performance may benefit more from specific dual-task training []. Observed gains suggest a possible functional relevance of these interventions, although statistical consistency across studies remains limited.

Analysis of dual-task cost/effect, reported by four studies [,,,], demonstrated improvements in multiple contexts, reflecting enhanced cognitive-motor integration during walking. For example, Antonio et al. [] reported a substantial improvement in DTC in the dual-task group, while Baek et al. [], Chuang et al. [], and Liu et al. [] also documented relevant improvements in DTC/DTE. These results highlight that relative assessment of dual-task performance provides complementary clinical insights beyond absolute gait speed analysis, being essential to understanding cognitive-motor interference [].

Four studies [,,,] included follow-up assessments. Overall, within-group gains in dual-task gait speed appeared to be maintained, with minimal between-group differences, except for a small advantage for dual-task training reported by Meester et al. []. The limited reporting and heterogeneity of follow-up data constrain firm conclusions regarding the durability of functional improvements.

Methodological heterogeneity across studies remained high, encompassing multiple dimensions of study design and intervention implementation. Differences included intervention type (treadmill-based, C-Mill therapy, overground gait training, multimodal programs, mixed aerobic-resistance training), duration (4–15 weeks) and total sessions (10–30), as well as session length (30–90 min). Exercise intensity varied, from aerobic treadmill walking at 55–85% of maximum heart rate [] to individualized overground and multimodal protocols [,,]. Cognitive dual-tasks also differed widely, spanning verbal fluency, serial-three subtraction, Stroop and clock tasks, working memory, calculation, and daily life scenario exercises, with variable prioritization strategies (fixed vs. variable priority) [,,,,,,]. Gait speed assessment employed heterogeneous instruments and protocols, including 4–10 m walk tests, 2 min walk tests, OptoGait, GAITRite, and LEGSys™/Qualysis systems, with self-selected, comfortable, or fast walking speeds [,,,,,,]. This multifaceted variability precluded meta-analytic synthesis and limits the generalizability of findings, underscoring the challenges of drawing uniform conclusions across studies.

Participant heterogeneity further contributed to variable outcomes, as differences in stroke chronicity, lesion characteristics, and baseline functional capacity may modulate responsiveness to dual-task training [,]. Stratified analyses considering these factors could clarify which subgroups derive the greatest benefit.

The methodological assessment of the included studies revealed moderate to good quality, with PEDro scores ranging from 5 to 8/10. Common limitations included lack of participant and therapist blinding, inconsistent allocation concealment and assessor blinding, infrequent intention-to-treat analyses, and variable reporting of between-group comparisons. Despite these limitations, within-group improvements in dual-task gait speed were generally consistent, while between-group effects were observed only in Baek et al. []. Precision was limited by small sample sizes and variability in measurement methods. This context suggests that, although improvements may be functionally relevant, caution is warranted when generalizing the findings due to methodological variability and the modest magnitude of observed effects.

The results of this review are consistent with previous evidence, including the synthesis by Plummer and Iyigün [], which indicates that exercise-based interventions can improve dual-task gait speed, although current findings do not provide conclusive evidence for the superiority of dual-task over single-task training. The observed magnitude of improvements suggests potential clinical relevance, yet dual-task gait speed lacks established reference values, emphasizing the importance of relative indices such as DTC or DTE for interpretation [,].

From a clinical perspective, both dual-task and single-task interventions were safe and feasible, with no adverse events reported. Decisions regarding training modality should be individualized, incorporating baseline performance, cognitive-motor capacity, and personal rehabilitation goals. Structured exercise protocols with defined progression criteria and standardized assessment tools are recommended to enhance clinical reproducibility and optimize functional outcomes.

For future research, it is recommended to: (i) conduct larger RCTs with standardized training protocols; (ii) systematically include relative metrics such as DTC/DTE; (iii) define minimal clinically important differences for dual-task gait; (iv) explore stratification by baseline performance, chronicity, and cognitive load; and (v) implement robust follow-up to assess the sustainability of effects. Additionally, integration of advanced gait analysis methods, including machine learning-based pattern recognition, may provide greater precision in monitoring and optimizing individualized interventions [].

In summary, exercise-based interventions hold promise for improving dual-task gait in post-stroke populations. Despite encouraging within-group effects, the evidence is constrained by heterogeneity, limited sample sizes, and methodological variability. Clinical application should be guided by individualized assessment, structured intervention planning, and careful monitoring, while future studies aim to strengthen the evidence base and enhance generalizability of findings.

5. Conclusions

The results of this review indicate that exercise-based interventions can improve dual-task gait speed in individuals with post-stroke sequelae. However, the available evidence remains insufficient to establish the superiority of dual-task training over single-task training. Significant methodological variability, the limited number of trials, small sample sizes, and inconsistent follow-up data constrain the strength and generalizability of the conclusions.

The magnitude of observed improvements, ranging from approximately 0.05 to 0.31 m/s, suggests potential clinical relevance; however, no established reference values or minimal clinically important differences exist for dual-task gait. For this reason, any interpretation of the functional impact of these changes should be approached with caution, and it is advisable to consider relative measures, such as dual-task cost or dual-task effect, to better frame the clinical relevance of the results.

Despite these limitations, both training modalities appear safe, feasible, and potentially beneficial, justifying their integration into individualized rehabilitation programs. The choice of intervention should take into account specific functional goals, baseline dual-task performance, and patient preferences, emphasizing the importance of shared decision-making.

Future research should prioritize large-scale, methodologically rigorous comparative trials with standardized training protocols. Establishing clinically relevant values for dual-task gait speed and using assessment tools with high ecological validity (such as wearable gait sensors) are essential steps to strengthen the evidence base and inform more precise clinical recommendations. These advances may contribute to optimizing functional outcomes and promoting greater independence in the daily lives of individuals with post-stroke sequelae.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152312697/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts Checklist; Table S2: PRISMA 2020 for Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S.G. and C.P.; methodology, all authors; validation, all authors; formal analysis, G.A., I.S., M.E.T., R.P. and S.R.; investigation, G.A., I.S., M.E.T., R.P. and S.R.; data curation, G.A., I.S., M.E.T., R.P. and S.R.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A., I.S., M.E.T., R.P. and S.R.; writing—review and editing, R.S.G. and C.P.; visualization, G.A., I.S., M.E.T., R.P. and S.R.; supervision, R.S.G. and C.P.; project administration, R.S.G. and C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors employed both GPT-4o and DeepL (https://www.deepl.com/en/translator) to assist with translation and proofreading. Subsequently, all content was carefully reviewed and edited by the authors, who take full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BA | Blinding of Assessors |

| BS | Blinding of Subjects |

| BT | Blinding of Therapists |

| CA | Concealed Allocation |

| ECS | Eligibility Criteria Specified |

| GSB | Group Similar at Baseline |

| ITA | Intention-to-Treat Analysis |

| NR | Not Reported |

| OD | Outcome Data from >85% of Subjects |

| PEVM | Point Estimates and Variability Measures |

| RA | Random Allocation |

| RBC | Reported Between-group Comparisons |

Appendix A. Full Search Strategy Used in Web of Science

| ( |

| TS = (stroke OR cerebrovascular accident OR cerebral stroke OR cerebrovascular apoplexy OR brain vascular accident OR cerebrovascular stroke OR apoplexy OR CVA OR CVAs OR cerebrovascular accidents OR brain vascular accidents OR cerebral strokes) |

| AND |

| TS = (exercise therapy OR rehabilitation exercise OR exercise, rehabilitation OR exercises rehabilitation OR rehabilitation exercises OR therapy, exercise OR exercise therapies OR therapies, exercise) |

| AND |

| TS = (walking speed OR speeds, walking OR speed, walking OR walking speeds OR walking pace OR paces, walking OR pace, walking OR walking paces OR gait speed OR gait speeds OR speed gait OR speeds, gait) |

| AND |

| TS = (dual task* OR dual-task*) |

| ) |

References

- Feld, J.A.; Zukowski, L.A.; Howard, A.G.; Giuliani, C.A.; Altmann, L.J.P.; Najafi, B.; Plummer, P. Relationship Between Dual-Task Gait Speed and Walking Activity Poststroke. Stroke 2018, 49, 1296–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, C.; Jiang, Y. Effect of dual task-based training on motor and cognitive function in stroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trails. BMC Neurol. 2025, 25, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Magdaleno, M.; Pereiro, A.; Navarro-Pardo, E.; Juncos-Rabadán, O.; Facal, D. Dual-task performance in old adults: Cognitive, functional, psychosocial and socio-demographic variables. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Barros, G.M.; Melo, F.; Domingos, J.; Oliveira, R.; Silva, L.; Fernandes, J.B.; Godinho, C. The Effects of Different Types of Dual Tasking on Balance in Healthy Older Adults. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deblock-Bellamy, A.; Lamontagne, A.; Blanchette, A.K. Cognitive-Locomotor Dual-Task Interference in Stroke Survivors and the Influence of the Tasks: A Systematic Review. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deblock-Bellamy, A.; Lamontagne, A.; McFadyen, B.J.; Ouellet, M.C.; Blanchette, A.K. Dual-Task Abilities During Activities Representative of Daily Life in Community-Dwelling Stroke Survivors: A Pilot Study. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 855226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, P.; Iyigün, G. Effects of Physical Exercise Interventions on Dual-Task Gait Speed Following Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 2548–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, F.; Shi, H.; Liu, R.; Wan, X. Effects of dual-task training on gait and balance in stroke patients: A meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2022, 36, 1186–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Whitton, N.; Zand, R.; Dombovy, M.; Parnianpour, M.; Khalaf, K.; Rashedi, E. A Systematic Review of Fall Risk Factors in Stroke Survivors: Towards Improved Assessment Platforms and Protocols. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 910698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, D.; Joshua, A.M.; K, V.K.; Nayak, A.; Mithra, P.; Pai, R.; Pai, S.; Krishnan K, S.; Palaniswamy, V. Dual tasking as a predictor of falls in post-stroke: A cross-sectional analysis comparing Walking While Talking versus Stops Walking While Talking. F1000Res 2024, 13, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurovic, O.; Mihaljevic, O.; Radovanovic, S.; Kostic, S.; Vukicevic, M.; Brkic, B.G.; Stankovic, S.; Radulovic, D.; Vukomanovic, I.S.; Radevic, S.R. Risk Factors Related to Falling in Patients after Stroke. Iran. J. Public. Health 2021, 50, 1832–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Lee, G. Impaired dynamic balance is associated with falling in post-stroke patients. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2013, 230, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Yu, J.; Rhee, H. Risk factors related to falling in stroke patients: A cross-sectional study. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1751–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, C.U.; Hansson, P.O. Determinants of falls after stroke based on data on 5065 patients from the Swedish Väststroke and Riksstroke Registers. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayabinar, B.; Alemdaroğlu-Gürbüz, İ.; Yilmaz, Ö. The effects of virtual reality augmented robot-assisted gait training on dual-task performance and functional measures in chronic stroke: A randomized controlled single-blind trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 57, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiaramonte, R.; Bonfiglio, M.; Leonforte, P.; Coltraro, G.L.; Guerrera, C.S.; Vecchio, M. Proprioceptive and Dual-Task Training: The Key of Stroke Rehabilitation, A Systematic Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2022, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, N.E.; Cheek, F.M.; Nichols-Larsen, D.S. Motor-Cognitive Dual-Task Training in Persons With Neurologic Disorders: A Systematic Review. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2015, 39, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Wan, X. Comparative effects of arithmetic, speech, and motor dual-task walking on gait in stroke survivors: A cross-sectional study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1587153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alingh, J.F.; Groen, B.E.; Kamphuis, J.F.; Geurts, A.C.H.; Weerdesteyn, V. Task-specific training for improving propulsion symmetry and gait speed in people in the chronic phase after stroke: A proof-of-concept study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2021, 18, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau-Pellicer, M.; Chamarro-Lusar, A.; Medina-Casanovas, J.; Serdà Ferrer, B.C. Walking speed as a predictor of community mobility and quality of life after stroke. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2019, 26, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Chen, J.; Peng, J.; Xiao, W. Comparing the effectiveness of dual-task and single-task training on walking function in stroke recovery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2025, 104, e41776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, P.; Eskes, G. Measuring treatment effects on dual-task performance: A framework for research and clinical practice. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahi, M.; Kuber, P.M.; Rashedi, E. Dual Tasking Affects the Outcomes of Instrumented Timed up and Go, Sit-to-Stand, Balance, and 10-Meter Walk Tests in Stroke Survivors. Sensors 2024, 24, 2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, H.; Quan, W.; Jiang, X.; Liang, M.; Li, S.; Ugbolue, U.C.; Baker, J.S.; Gusztav, F.; Ma, X.; et al. A new method proposed for realizing human gait pattern recognition: Inspirations for the application of sports and clinical gait analysis. Gait Posture 2024, 107, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, M.; Chiaramonte, R.; De Sire, A.; Buccheri, E.; Finocchiaro, P.; Scaturro, D.; Letizia Mauro, G.; Cioni, M. Do proprioceptive training strategies with dual-task exercises positively influence gait parameters in chronic stroke? A systematic review. J. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 56, jrm18396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Bi, M.M.; Zhou, T.T.; Liu, L.; Zhang, C. Effect of Dual-Task Training on Gait and Balance in Stroke Patients: An Updated Meta-analysis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 101, 1148–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.S.M.; Rehab, N.I.; Aly, S.M.A. Effect of aquatic versus land motor dual task training on balance and gait of patients with chronic stroke: A randomized controlled trial. NeuroRehabilitation 2019, 44, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landim, S.F.; López, R.; Caris, A.; Castro, C.; Castillo, R.D.; Avello, D.; Magnani Branco, B.H.; Valdés-Badilla, P.; Carmine, F.; Sandoval, C.; et al. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality in Occupational Therapy for Post-Stroke Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-Q.; Wei, M.-F.; Chen, L.; Xi, J.-N. Research progress in the application of motor-cognitive dual-task training in rehabilitation of walking function in stroke patients. J. Neurorestoratology 2023, 11, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Tabassum, D.; Baig, S.S.; Moyle, B.; Redgrave, J.; Nichols, S.; McGregor, G.; Evans, K.; Totton, N.; Cooper, C.; et al. Effect of Exercise Interventions on Health-Related Quality of Life After Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Stroke 2021, 52, 2445–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, D.; Goldberg, C.; Winterbottom, L.; Nilsen, D.M.; Mahoney, D.; Gillen, G. Task Oriented Training Interventions for Adults With Stroke to Improve ADL and Functional Mobility Performance (2012–2019). Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 77, 7710393050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, K.S.; Moncion, K.; Wiley, E.; Morgan, A.; Huynh, E.; Balbim, G.M.; Elliott, B.; Harris-Blake, C.; Krysa, B.; Koetsier, B.; et al. Prescribing strength training for stroke recovery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 2025, 59, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, R.; Triolo, G.; Ivaldi, D.; Quartarone, A.; Lo Buono, V. The Role of Dance in Stroke Rehabilitation: A Scoping Review of Functional and Cognitive Effects. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tally, Z.; Boetefuer, L.; Kauk, C.; Perez, G.; Schrand, L.; Hoder, J. The efficacy of treadmill training on balance dysfunction in individuals with chronic stroke: A systematic review. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2017, 24, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, L.C.; Hsu, A.L.; Hu, G.C.; Ou, Y.C.; Chen, A.C.; Chuang, L.L. Cognitive and motor multi-task balance training improves dual-task walking performance in ambulatory patients after stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, B.; Thomas, L.H.; Coupe, J.; McMahon, N.E.; Connell, L.; Harrison, J.; Sutton, C.J.; Tishkovskaya, S.; Watkins, C.L. Repetitive task training for improving functional ability after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 11, CD006073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, B.; Koohi, N.; Kaski, D.; Bamiou, D.E.; Pavlou, M. Impact of Vestibular Rehabilitation and Dual-Task Training on Balance and Gait in Survivors of Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e040663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, J.; Truijen, S.; Van Criekinge, T.; Saeys, W. Feasibility and effectiveness of repetitive gait training early after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 51, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwakkel, G.; Stinear, C.; Essers, B.; Munoz-Novoa, M.; Branscheidt, M.; Cabanas-Valdés, R.; Lakičević, S.; Lampropoulou, S.; Luft, A.R.; Marque, P.; et al. Motor rehabilitation after stroke: European Stroke Organisation (ESO) consensus-based definition and guiding framework. Eur. Stroke J. 2023, 8, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, B.A.; Bonuzzi, G.M.G.; Alves, C.M.P.; Polese, J.C.; Mochizuki, L.; Torriani-Pasin, C. Does dual task merged in a mixed physical exercise protocol impact the mobility under dual task conditions in mild impaired stroke survivors? A feasibility, safety, randomized, and controlled pilot trial. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, C.Y.; Chang, W.N.; Park, B.Y.; Lee, K.B.; Kang, K.Y.; Choi, M.R. Effects of Dual-Task Gait Treadmill Training on Gait Ability, Dual-Task Interference, and Fall Efficacy in People With Stroke: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys. Ther. 2021, 101, pzab067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, L.L.; Hsu, A.L.; Lin, Y.H.; Yu, M.H.; Hu, G.C.; Ou, Y.C.; Wong, A.M. Multimodal training with dual-task enhances immediate and retained effects on dual-task effects of gait speed not by cognitive-motor trade-offs in stroke survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 47, 1194–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Yang, Y.R.; Tsai, Y.A.; Wang, R.Y. Cognitive and motor dual task gait training improve dual task gait performance after stroke—A randomized controlled pilot trial. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meester, D.; Al-Yahya, E.; Dennis, A.; Collett, J.; Wade, D.T.; Ovington, M.; Liu, F.; Meaney, A.; Cockburn, J.; Johansen-Berg, H.; et al. A randomized controlled trial of a walking training with simultaneous cognitive demand (dual-task) in chronic stroke. Eur. J. Neurol. 2019, 26, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, P.; Zukowski, L.A.; Feld, J.A.; Najafi, B. Cognitive-motor dual-task gait training within 3 years after stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2022, 38, 1329–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermans, C.; Roerdink, M.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Beek, P.J.; Janssen, T.W.J. Walking-adaptability therapy after stroke: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2021, 22, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platz, T. Evidence-Based Guidelines and Clinical Pathways in Stroke Rehabilitation-An International Perspective. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todhunter-Brown, A.; Sellers, C.E.; Baer, G.D.; Choo, P.L.; Cowie, J.; Cheyne, J.D.; Langhorne, P.; Brown, J.; Morris, J.; Campbell, P. Physical rehabilitation approaches for the recovery of function and mobility following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 2, CD001920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, J.; Kashif, A.; Shahid, M.K. A Comprehensive Review of Physical Therapy Interventions for Stroke Rehabilitation: Impairment-Based Approaches and Functional Goals. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Lu, Y.; Yao, L. Mediation and moderation analysis of the association between physical capability and quality of life among stroke patients. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, C.S.; Wang, S.; Miller, T.; Pang, M.Y. Degree and pattern of dual-task interference during walking vary with component tasks in people after stroke: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2022, 68, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, R.B. PEDro: A physiotherapy evidence database. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 2008, 27, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, R.; Moseley, A.; Sherrington, C. PEDro: A database of randomised controlled trials in physiotherapy. Health Inf. Manag. 1998, 28, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.G.; Moseley, A.M.; Sherrington, C.; Elkins, M.R.; Herbert, R.D. A description of the trials, reviews, and practice guidelines indexed in the PEDro database. Phys. Ther. 2008, 88, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M.R.; Van der Wees, P.J.; Pinheiro, M.B. Using research to guide practice: The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2020, 24, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Maher, C.G.; Moseley, A.M. PEDro. A database of randomized trials and systematic reviews in physiotherapy. Man. Ther. 2000, 5, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrington, C.; Moseley, A.M.; Herbert, R.D.; Elkins, M.R.; Maher, C.G. Ten years of evidence to guide physiotherapy interventions: Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 836–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, S.; Lusardi, M. White paper: “walking speed: The sixth vital sign”. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2009, 32, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, A.; Fritz, S.L.; Lusardi, M. Walking speed: The functional vital sign. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2015, 23, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasseel-Ponche, S.; Roussel, M.; Toba, M.N.; Sader, T.; Barbier, V.; Delafontaine, A.; Meynier, J.; Picard, C.; Constans, J.M.; Schnitzler, A.; et al. Dual-task versus single-task gait rehabilitation after stroke: The protocol of the cognitive-motor synergy multicenter, randomized, controlled superiority trial (SYNCOMOT). Trials 2023, 24, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilson, J.K.; Sullivan, K.J.; Cen, S.Y.; Rose, D.K.; Koradia, C.H.; Azen, S.P.; Duncan, P.W. Meaningful gait speed improvement during the first 60 days poststroke: Minimal clinically important difference. Phys. Ther. 2010, 90, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristina da Silva, L.; Danielli Coelho de Moraes Faria, C.; da Cruz Peniche, P.; Ayessa Ferreira de Brito, S.; Tavares Aguiar, L. Validity of the two-minute walk test to assess exercise capacity and estimate cardiorespiratory fitness in individuals after stroke: A cross-sectional study. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2024, 31, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.H.; Woo, Y.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, K.H. Effects of task-oriented treadmill-walking training on walking ability of stoke patients. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2015, 22, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; He, C.; Pang, M.Y. Reliability and Validity of Dual-Task Mobility Assessments in People with Chronic Stroke. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.Y.; Han, M.R.; Lee, H.G. Effect of Dual-task Rehabilitative Training on Cognitive and Motor Function of Stroke Patients. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2014, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarello, F.; Bianchi, V.A.; Baccini, M.; Rubbieri, G.; Mossello, E.; Cavallini, M.C.; Marchionni, N.; Di Bari, M. Tools for observational gait analysis in patients with stroke: A systematic review. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 1673–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.H.; Hsu, M.J.; Hsu, H.W.; Wu, H.C.; Hsieh, C.L. Psychometric comparisons of 3 functional ambulation measures for patients with stroke. Stroke 2010, 41, 2021–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahi, M.; Rashedi, E.; Kuber, P.M.; Jahangiri, S.; Kazempour, B.; Dombovy, M.; Azadeh-Fard, N. Post-Stroke Functional Changes: In-Depth Analysis of Clinical Tests and Motor-Cognitive Dual-Tasking Using Wearable Sensors. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. i–xxviii. 694p. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M.; Katikireddi, S.; Sowden, A.; McKenzie, J.; Thomson, H. Improving Conduct and Reporting of Narrative Synthesis of Quantitative Data (ICONS-Quant): Protocol for a mixed methods study to develop a reporting guideline. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiwa, S.R.; Costa, L.O.; Costa, L.a.C.; Moseley, A.; Hespanhol Junior, L.C.; Venâncio, R.; Ruggero, C.; Sato, T.e.O.; Lopes, A.D. Reproducibility of the Portuguese version of the PEDro Scale. Cad. Saude Publica 2011, 27, 2063–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morton, N.A. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: A demographic study. Aust. J. Physiother. 2009, 55, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, M.R.; Moseley, A.M.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Maher, C.G. Growth in the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) and use of the PEDro scale. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 188–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, A.P.; Pegorari, M.S. How to Classify Clinical Trials Using the PEDro Scale? J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2020, 11, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moseley, A.M.; Herbert, R.; Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Elkins, M.R. PEDro scale can only rate what papers report. Aust. J. Physiother. 2008, 54, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutron, I.; Guittet, L.; Estellat, C.; Moher, D.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Ravaud, P. Reporting methods of blinding in randomized trials assessing nonpharmacological treatments. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Garrett, M.; Gronley, J.K.; Mulroy, S.J. Classification of walking handicap in the stroke population. Stroke 1995, 26, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).