Abstract

The optimization of distillation columns is critically important due to their substantial contribution to operational costs in the petrochemical industry. This paper introduces a computationally efficient surrogate-based optimization framework designed explicitly for prefractionation columns. To address the challenges of high computational cost and model accuracy in model-based optimization, a self-adaptive Kriging model, which features automated hyperparameter tuning via Bayesian optimization, is implemented and trained using Latin hypercube sampling of historical process data. By integrating a self-adaptive Kriging model with a modified firefly algorithm, the framework efficiently identifies optimal operating conditions that maximize economic profit while adhering to operational constraints. Case studies demonstrate that the proposed framework achieves superior economic performance, increasing the average final profit by 0.17–0.31% compared to non-adaptive surrogate benchmarks. Furthermore, it is exceptionally stable, achieving a minimal relative standard deviation of only 0.037% in the final profit across 30 independent runs, significantly lower than the 0.266% and 0.237% achieved by the benchmark methods. This study provides a practical and efficient tool to optimize complex distillation columns with limited computational resources.

1. Introduction

Distillation represents one of the most critical separation processes in the petrochemical industry. According to recent studies, distillation operations account for approximately 40 percent of the total capital and operating costs in petrochemical manufacturing [1]. Among various distillation systems, prefractionation columns are significant as they perform the initial separation of multi-component mixtures, establishing the foundation for subsequent purification steps [2]. Optimizing prefractionation columns yields substantial economic benefits by improving efficiency, reducing energy consumption, and enhancing product quality, especially in crude oil refining processes.

The optimization of prefractionation columns involves determining optimal operating conditions that maximize economic benefits while satisfying product specifications and operational constraints [3]. Traditional approaches employ either simplified shortcut models or rigorous equilibrium-stage models integrated with mathematical programming techniques [2,3]. These methods often require substantial computational resources due to the highly nonlinear nature of distillation columns and the complex thermodynamic relationships [4,5], particularly when searching for global optima in landscapes with multiple local optima.

Surrogate-based optimization (SBO) has emerged as an effective alternative to address these computational challenges [6,7]. By constructing an approximation model that emulates the original system with reduced computational requirements, SBO enables efficient exploration of the design space [8,9]. This approach has gained attention in process engineering, particularly for distillation columns where rigorous simulations are computationally intensive [10]. The selection of an appropriate surrogate model depends on the specific objectives of the optimization problem, the inherent properties of the surrogate model, and the available information about the process being optimized [11]. Recent advancements in surrogate-based optimization have demonstrated its effectiveness across various distillation applications through classic surrogate modelling techniques, including polynomial regression, artificial neural network (ANN), radial basis function (RBF), and Kriging model, among others [12,13,14,15]. While polynomial regression often fails to capture complex nonlinearities, the applicability of data-intensive models like ANN can be challenging in this domain. If the training data is insufficient, it is often necessary to run time-consuming, rigorous simulations to generate larger datasets, which incur very high computational costs. When applied to the sparse datasets characteristic of such problems, careful model selection and regularization techniques are needed to mitigate potential overfitting [16,17]. Furthermore, like many surrogate models, including Kriging and ANNs, it often provides limited direct physical insight.

In this case, the Kriging model, as a type of Gaussian process model [18,19], is well-suited for optimizing computationally expensive systems. The statistical foundation of the Kriging model enables it to achieve high accuracy with limited training data, making it appropriate for distillation column modelling [20]. Crucially, its ability to provide not only predictions but also estimates of prediction uncertainty enables more intelligent and efficient exploration. The effectiveness of the Kriging model critically depends on sampling methods and hyperparameters. To ensure consistent accuracy, the sampling data must balance randomness and uniform distribution [21]. While traditional Monte Carlo sampling is random, it often leads to clustering of points and requires larger datasets [22]. Therefore, Latin hypercube sampling (LHS) is preferred for surrogate modelling as it ensures balanced exploration with significantly fewer samples [23,24], making it highly suitable for building an accurate model from small datasets.

Meanwhile, hyperparameters significantly influence model accuracy [25]. Some researchers implement surrogate model switching strategies to ensure model accuracy [26,27], but this requires prior knowledge and increases computational burden. A more flexible alternative is hyperparameter tuning. Bayesian optimization is a probabilistic, sequential approach to global optimization [28], and offers an attractive alternative by: (1) employing a probabilistic surrogate model to learn from previous evaluations [29]; (2) balancing exploration of uncertain regions with exploitation of promising areas; and (3) demonstrating effectiveness for expensive black-box optimization problems [9]. By integrating Bayesian hyperparameter optimization with the Kriging model, a self-adaptive Kriging (SAK) framework is developed that automatically adjusts its parameters. This adaptive capability ensures consistent accuracy across diverse optimization scenarios without manual intervention. Consequently, investigating the effectiveness of the self-adaptive Kriging model in distillation column optimization represents a promising direction for enhancing computational efficiency while maintaining prediction accuracy in process engineering applications. This self-adaptive Kriging model forms the foundation of our optimization framework. The second critical component is the optimization algorithm that searches the solution space mapped by this surrogate.

Selecting an appropriate optimization algorithm depends on the problem’s characteristics. Here, the objective function relies on the surrogate model output. This data-driven surrogate, much like the rigorous simulator, functions as a “black-box” because no explicit algebraic equation describes the profit. A critical consequence is the unavailability of analytical derivatives (gradients). This characteristic precludes the use of standard gradient-based methods.

Furthermore, complex chemical processes often exhibit non-convexity due to strong nonlinearities, such as Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor kinetics [30], leading to multiple local optima. This multi-solution characteristic poses a fundamental challenge, making the search for global optima difficult. Gradient-based optimization algorithms, such as Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) and Limited-memory Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno (L-BFGS), are core methods for large-scale nonlinear problems that utilize gradient information to find local descent directions. However, their primary drawback stems from their nature as local search algorithms. They are susceptible to the initial starting point and tend to converge to the nearest local optimum, offering no guarantee of finding the global solution. Researchers develop specialized SQP variants, for example, by combining Quadratic Constraint Quadratic Programming approximations with splitting techniques [31], aiming to escape local traps. L-BFGS, due to its memory-limited characteristic of discarding old information, arguably reinforces its nature as a purely local search method, potentially increasing its sensitivity. Moreover, gradient-based methods can fail when constraints are highly nonlinear, requiring additional mechanisms like exact penalty functions [32]. Finally, the brute-force grid search, which requires a massive number of additional evaluations, is computationally infeasible. Even a relatively coarse discretization of the eight decision variables, with merely 10 points per dimension, would necessitate approximately evaluations. This is precisely what surrogate modelling endeavours to circumvent.

Given these limitations, SBO using derivative-free global optimization strategies, particularly metaheuristics, has become the established state of the art. Among these, the Firefly Algorithm (FA) is selected. The literature consensus identifies FA as a simple, flexible, and easy-to-implement algorithm [33,34,35] that is particularly effective and efficient in solving challenging engineering problems [36], including the exact non-derivative, nonlinear, and/or non-convex problems that define our black-box surrogate. The most significant advantage of FA for our landscape is its inherent mechanism for handling multi-modality [34]. The attraction-based search of FA, in which local attraction is stronger than long-distance attraction, automatically subdivides the population into subgroups [37]. This unique feature allows FA to naturally and efficiently handle highly nonlinear, multimodal optimization problems and reduces the likelihood of getting stuck in local minima [34]. Furthermore, studies indicate that FA can perform better than genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization (PSO), often achieving better performance in determining the global optimum in multivariable problems [36]. This superiority stems from key structural differences: FA mitigates “premature convergence” by not relying on a single global best [33], and its velocity-free nature 11results in “fewer parameters than PSO”. While the standard FA offers these compelling advantages, the literature [33,37] indicates that modifications are often beneficial. Therefore, this work proposes a Modified Firefly Algorithm (MFA) tailored to improve solution precision within our adaptive surrogate framework.

This paper develops an efficient surrogate-based optimization framework to address the computationally expensive task of optimizing prefractionation columns. The proposed framework integrates a self-adaptive Kriging (SAK) model with a modified firefly algorithm (MFA) to achieve this goal. The primary contributions of this study are as follows.

- The integrated SAK-MFA framework is successfully applied to the economic optimization of an industrial prefractionation column. It is demonstrated to significantly reduce computational costs compared to high-fidelity simulation-based optimization while identifying superior operating points, thus providing a practical and efficient tool for real-world process optimization.

- A SAK model is implemented, featuring an automated Bayesian optimization approach for hyperparameter tuning. This eliminates the need for manual, expert-driven selection and enhances the predictive accuracy of the model for the complex behaviour of prefractionation columns.

- A MFA is applied to solve the optimization problem defined by the SAK surrogate efficiently. The MFA is specifically structured to balance global exploration and local exploitation, enabling a more effective search for optimal operating conditions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a detailed description of the prefractionation column and formulates the optimization problem. Section 3 presents the surrogate-aided optimization strategy, including the Kriging modelling approach, Bayesian hyperparameter optimization, MFA, and the integrated optimization framework. Section 4 demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed optimization framework, as illustrated by optimizing a real prefractionation column using rigorous Aspen Plus simulations. Meanwhile, it is also compared with alternative optimization methods. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the key findings and discusses potential directions for future research.

2. Problem Statement

2.1. Prefractionation Column Description

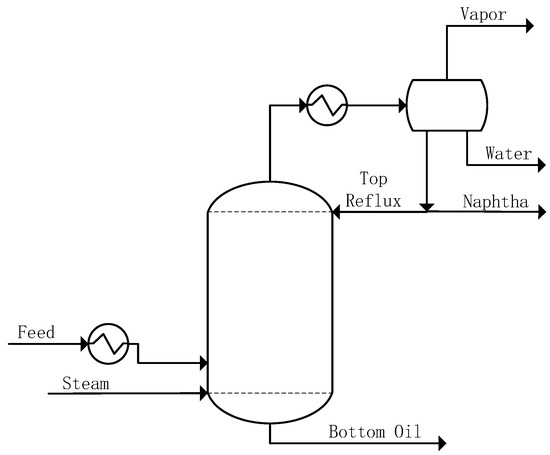

The prefractionation column serves as a preliminary processing unit within the atmospheric and vacuum distillation system in petroleum refining processes [38]. The complete prefractionation system consists of several integrated components: the main distillation column, overhead draw system, cooling equipment, flash drum, and feed heat exchanger network. These components work synergistically to achieve efficient separation of petroleum fractions. A typical structure of the prefractionation column is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A typical structure of the prefractionation column.

The operational sequence of the prefractionation system follows a systematic process flow. Initially, the feed stream is preheated in a heat exchanger network before entering the prefractionation column for primary separation. At the column bottom, stripping steam is introduced to enhance the vaporization of the feed stream and facilitate the separation of light components. The overhead output stream then passes through a condenser and enters a flash tank, where a three-phase separation process occurs. This separation yields three distinct products: overhead gas (primarily light hydrocarbons), condensate water, and naphtha product. To maintain optimal separation efficiency, the system recycles a portion of the naphtha product as column reflux. Meanwhile, the bottom oil, containing heavier hydrocarbon components, is directed to the atmospheric distillation unit for subsequent processing and further fractionation.

2.2. Optimization Problem Formulation

The optimization problem aims to maximize the operational profit of the prefractionation column while satisfying essential process constraints. The formulation incorporates eight key decision variables that control the column’s performance. These variables include the crude oil flow rate and temperature , the feeding temperature of the reflux accumulator , and the reflux flow rate and temperature . The product streams are defined by the set , where represents the overhead gas product, denotes the light hydrocarbon fraction, and represents the bottom oil directed to subsequent processing. The flow rates of these products are represented as for each . Additional process parameters monitored during optimization include the top section temperature and pressure , as well as the feeding section temperature and bottom temperature , which serve as indicators of process stability and product quality. The mathematical formulation of the optimization problem is expressed as:

where is the operational profit of the prefractionation column, is the unit price of each product stream, is the unit price of crude oil. and are the lower and upper bounds of decision variables. All product flow rates and feed flow rates satisfy the mass conservation.

3. Surrogate-Aided Optimization Strategy

3.1. Surrogate Modeling Modular

The Kriging model [26], grounded in the optimal linear unbiased estimation approach, consists of two components: a polynomial representation and a deviation term from that polynomial.

where is a polynomial formulation designed to closely approximate the actual function. In this study, is assumed to be an unknown constant, which means a zero-order polynomial. is a stochastic process subjected to a normal distribution . The characteristics of are defined by:

where is a set of correlation parameters that determine the gradient of , and n is the dimension of x. In this formulation, the Gaussian correlation function is employed:

To construct an effective Kriging model, appropriate training data must be generated through systematic sampling of the input space. LHS is particularly suitable for this purpose. This methodology, proposed in reference [39], is an n-dimensional extension of Latin-square sampling and provides superior space-filling properties while maintaining computational efficiency. In the context of Kriging model development, the input vector x represents the set of decision variables for the optimization problem. For a sample size of m, the LHS procedure divides the range of each dimension into m non-overlapping intervals of equal probability. The mathematical formulation of this sampling process is:

where is the ith input variable in the jth sample, is the inverse cumulative distribution function, is a random permutation of integers , and is a random number in .

3.2. Bayesian Hyperparameter Optimizer

In the Kriging model, hyperparameters play a crucial role in determining predictive performance and generalization. The primary hyperparameter in the correlation function controls the smoothness and correlation length scales of the predicted response surface. This parameter significantly influences how the model interpolates between training points and extrapolates to unseen regions. To optimize these hyperparameters effectively, Bayesian optimization with Gaussian processes is employed. This approach minimizes the mean squared error obtained through three-fold cross-validation from the scikit-learn library [40], formulated as:

where is the prediction from the Kriging model trained on data excluding the k-th fold , and are the actual observed values. The search space for is with log-uniform sampling, as smaller values tend to produce better results for this application.

The optimization process uses a Gaussian process [18] surrogate model to approximate the objective function:

where is the mean function, and the squared exponential covariance kernel is

At each iteration t, the next evaluation point is selected by maximizing the Expected Improvement (EI) [29] acquisition function

where

Here, is the current best parameter value, controls the exploration-exploitation trade-off, while and denote the standard normal cumulative and probability density functions, respectively, and is the standard deviation. Through this Bayesian hyperparameter optimization approach, the Kriging model systematically refines its hyperparameters to minimize prediction error while maintaining computational efficiency. The resulting SAK model is subsequently employed to accurately represent the complex behaviour of the prefractionation column within the proposed surrogate-aided optimization strategy, enabling efficient exploration of the operational space without requiring excessive evaluations of the computationally intensive first-principles model.

3.3. Modified Firefly Algorithm

For the standard FA [35], there are three basic formulas:

In Equation (13), is the original light intensity, is the light absorption coefficient, and stands for the spatial distance between firefly i and j, for n fireflies. in Equation (14) is the value of original attractiveness. For Equation (15), and are the positions of firefly i and j in the space. is a constant step size factor, and is an n-dimensional vector whose entries are generated randomly from a uniform distribution between 0 and 1. As the evolution continues, most fireflies will eventually gather together. When there is no difference in brightness between the fireflies, the location of the fireflies is the optimal solution. The initialization of a firefly for standard FA is

where and are the lower and upper bounds of feasible regions with compatible dimensions. When combined with the location update method in Equation (15), it is clear that the algorithm is easily trapped into a local optimal solution. And Equation (15) shows that the influence of firefly i could be too strong when firefly i and j are close enough. To improve algorithm performance, a new two-step modified FA location-update strategy is proposed. First, let

This step makes each firefly search the swarm and move closer to the brighter firefly. Second, each firefly moves to the brightest one in the swarm as

where is the best firefly in the current iteration. Meanwhile, to help the improved FA find the optimal solution faster and better, the parameter is replaced by

where is the worst firefly in the current iteration. With Equation (19), the step size of each firefly is decided by its location. After each firefly updates its location, to avoid falling into the local optimal solution, fireflies are randomly initialized by Equation (16). These modifications could enhance algorithm performance, leading to lower iteration costs and better optimal solutions.

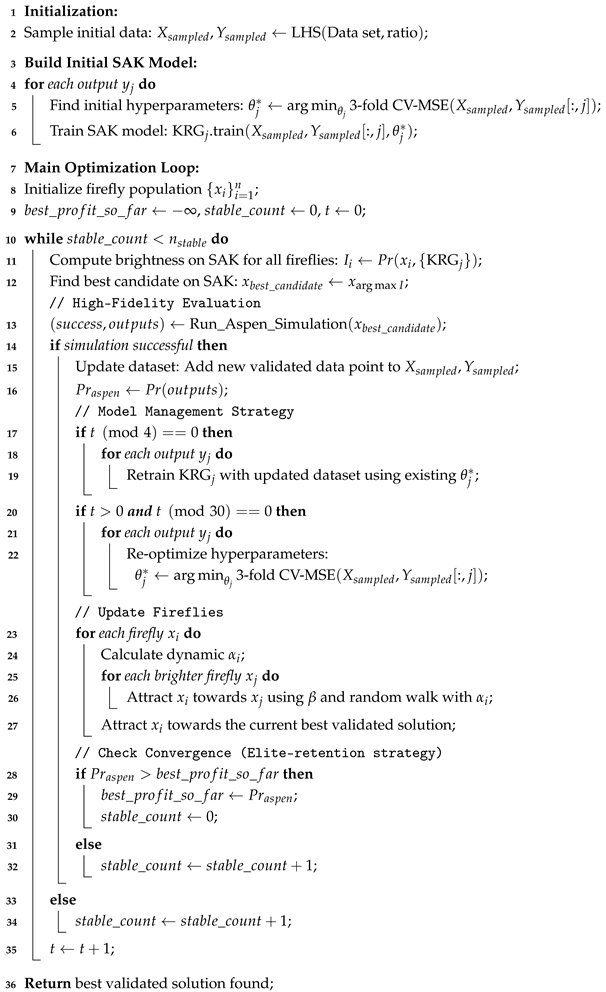

3.4. Integration Framework

The integrated optimization strategy combines the SAK model and the MFA into a cohesive, two-level surrogate-based optimization framework, illustrated in Algorithm 1. This structure is designed to efficiently locate the global optimum of computationally expensive processes by leveraging a fast surrogate model while ensuring solution reliability through targeted high-fidelity evaluations. The framework operates via two nested loops:

- Inner Loop: SAK Hyperparameter Optimization. This loop ensures the surrogate model’s adaptability. The hyperparameters of the SAK model (e.g., the correlation function parameter ) are automatically tuned using Bayesian optimization. The objective is to minimize the cross-validation error (CV-MSE) of the model based on the currently available training data. This inner loop ensures the surrogate provides the most accurate possible representation of the actual process behaviour given the data.

- Outer Loop: Process Economic Optimization. This loop performs the primary optimization task. The MFA searches for optimal operating conditions by iteratively evaluating candidate solutions using the fast, accurate SAK model built by the inner loop, rather than the computationally expensive high-fidelity simulator. The objective is to maximize the economic profit, subject to operational constraints. Within this outer loop, a critical model management strategy is employed to maintain and improve surrogate accuracy throughout the search. Candidate solutions identified by MFA on the surrogate are periodically selected for validation using the high-fidelity process simulator (e.g., Aspen Plus, detailed for our case study in Section 4.2). The simulator provides accurate output data for these points, enabling reliable economic profit calculations and validating the surrogate’s predictions in promising regions. These validated high-fidelity input-output data pairs are then added back to the training dataset used by the SAK model. The SAK model is periodically updated (retrained and hyperparameters potentially re-optimized, as per Algorithm 1) using this dynamically enriched dataset, ensuring its fidelity improves as the optimization progresses towards the optimum.

The primary goal of this integrated framework is to drastically reduce the number of required calls to the expensive high-fidelity simulator compared to direct optimization, while still achieving a reliable and high-quality optimal solution. The SAK prediction is implicitly incorporated into the objective function evaluated by the MFA during its search over the surrogate. In Algorithm 1, X and Y are inputs and outputs of the prefractionation column data sets. is the stopping criterion of the algorithm, that is, the global optimal profit remains unchanged throughout iterations. Other parameters have the same meaning as described in this paper.

| Algorithm 1: Surrogate-based Optimization using SAK and MFA with Two-Tiered Model Update. |

|

4. Results and Discussion

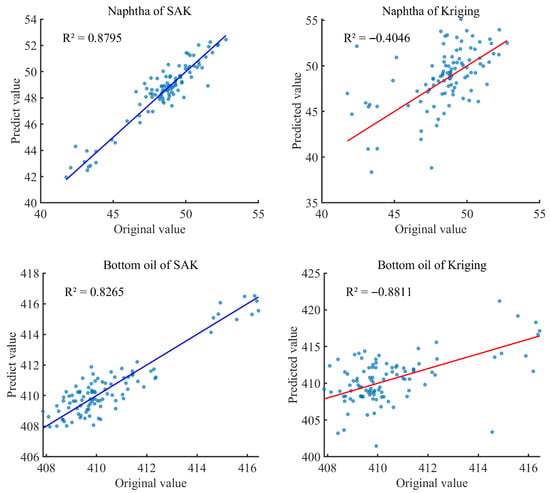

4.1. Surrogate Model Improvement

This section compares the prediction accuracy of the SAK model with that of other surrogate models. For the surrogate modelling component, the Kriging model is implemented using the Surrogate Modelling Toolbox (SMT 2.8.0) [41], an open-source Python package providing comprehensive libraries of surrogate modelling techniques. The hyperparameters of the standard Kriging model are fixed at 0.01. The RBF model was implemented using the default hyperparameter configuration of the SMT library. The ANN model, a multi-layer perceptron regressor from the Scikit-learn library [40], was configured with an architecture of two hidden layers containing 100 and 50 neurons, respectively. This model employed the commonly used ReLU activation function and the Adam optimizer. To ensure convergence during training, the maximum number of iterations was set to 1000. All decision variables and product streams have been introduced in Section 2.2. An initial dataset comprising 1000 historical operating data points was collected from a prefractionation column in a real refinery. Analysis revealed that this data corresponds to a narrow operating window around a single, stable condition, exhibiting minimal fluctuation. This indicates that, while valuable, the historical data likely represents suboptimal performance and is insufficient on its own to build a surrogate model capable of accurately predicting process behaviour across the entire potential operating space required for global optimization. Therefore, a specific procedure is followed to generate the initial training and testing sets. First, the 1000 historical data points are split into a training set and a testing set using a standard method from the Scikit-learn library. Then, LHS with a sampling ratio of 0.2 is explicitly applied to the training set subset. The actual training data points closest to these LHS samples (identified via nearest-neighbour search) were then selected to form the final initial training set () used for comparing the surrogate models in this section. The aforementioned testing set () was reserved for evaluating the predictive accuracy of different models. Due to mass conservation principles, only naphtha and bottom oil fractions need to be predicted by the surrogate models.

Table 1 presents the accuracy comparison results. With limited data, only the SAK model could achieve high predictive accuracy, yielding strong coefficients of determination () of 0.8795 for the Naphtha output and 0.8265 for the Bottom oil output. Correspondingly, it registered the lowest Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for both variables, indicating reliable performance in modelling the prefractionation column. In stark contrast, all other models failed to produce valid predictions. The standard Kriging model with fixed hyperparameters yielded negative scores, showing that proper hyperparameter optimization is critical for the model’s viability. The RBF and ANN models performed even more poorly, with significant negative scores indicating a complete failure to capture the underlying process dynamics from the available data. It should be noted that this comparison is conducted on unscaled, raw process data, a condition to which ANN and RBF models are known to be highly sensitive and which is a primary contributor to their poor performance. These findings suggest that RBF and ANN models are not suitable for this application without significant preprocessing. Due to the poor predictive performance of the RBF and ANN models under these conditions, their results have been omitted from Figure 2 for clarity, which focuses on the comparison between the SAK model and the standard Kriging model.

Table 1.

The accuracy results of each surrogate model.

Figure 2.

values of SAK model and standard Kriging model.

4.2. Surrogate-Based Optimization Results

For this case study, the high-fidelity simulation model, which plays a crucial role in validation, accurate profit calculation, and dataset enrichment within the optimization loop (as outlined in Section 3.4), was developed in Aspen Plus (V14.0) based on a prefractionation column from a real refinery. The structure of the prefractionation column in Aspen Plus is the same as shown in Figure 1. The column comprises 28 theoretical stages. The condenser type is set to ‘Partial-Vapor’, the reboiler is configured for bottom steam reboiling, and the valid-phases are specified as ‘Vapor–Liquid–Freewater’. The distillate rate is set as an operating specification. Desalted and preheated crude oil enters the column above stage 27, while the overhead output stream is withdrawn from the top of the column. Stripping steam enters the column at stage 28. The column outputs include the overhead output stream and bottom oil. The overhead output stream is cooled in a heat exchanger before entering a flash drum. The flash drum separates the stream into overhead off-gas, water, and naphtha. The condensed naphtha is split into two streams: one is withdrawn as product, while the other (the reflux) returns to stage 1 to maintain the required liquid-vapor contact efficiency. Heat exchanger networks were simplified to basic heater units in the Aspen Plus simulation environment, as this simplification is justified by the optimization objective being solely related to stream flow rates rather than heat integration efficiency. The feed stream heat exchanger outlet temperature is set to 231.62 °C, and the overhead heat exchanger outlet temperature is set to 44.05 °C.

As defined in Equation (1), all decision variables of the optimization problem are subject to specific constraints based on operational feasibility. These detailed ranges are presented in Table 2. It should be noted that, while most variables have flexible ranges, the feed rate is maintained at a constant 878.949 tonne/h to meet actual refinery throughput requirements. Meanwhile, the parameters of MFA are listed in Table 3.

Table 2.

Decision variables and their permissible ranges.

Table 3.

Parameters of the MFA.

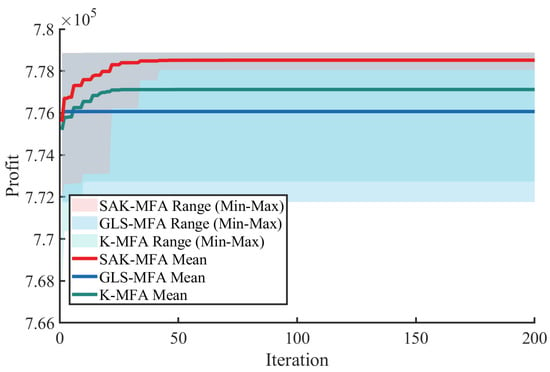

To demonstrate the efficiency of the proposed optimization approach, this study compares the performance of three distinct surrogate-assisted strategies combined with MFA: self-adaptive Kriging with MFA (SAK-MFA), global and local surrogate models with MFA (GLS-MFA), and a standard Kriging model with MFA (K-MFA). The GLS-MFA represents a conventional model-switching technique for maintaining predictive accuracy as referenced in Xiong et al. [26]. Within this framework, Kriging serves as the global surrogate model, while RBF serves as the local approximation model, with both models used alternately as the optimization progresses. The superior predictive accuracy of the SAK model, as established in Section 4.1, is hypothesized to be the primary driver of its enhanced performance in the optimization task. A more reliable surrogate enables the MFA to explore the solution space more efficiently, as reflected in the following convergence and solution quality results.

To ensure experimental validity, all three strategies use identical MFA parameters and the same historical dataset for model training. The objective function value (profit) is calculated according to Equation (1), with product pricing factors established as follows: vapor at 2.34, naphtha at 4926, bottom oil at 4000, and feed at 3000 monetary units per tonne. These standardized pricing coefficients are employed solely for comparative evaluation purposes and can be readily adjusted to reflect current market conditions in practical applications.

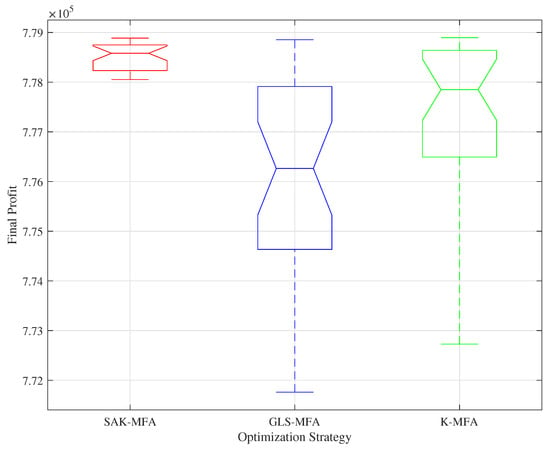

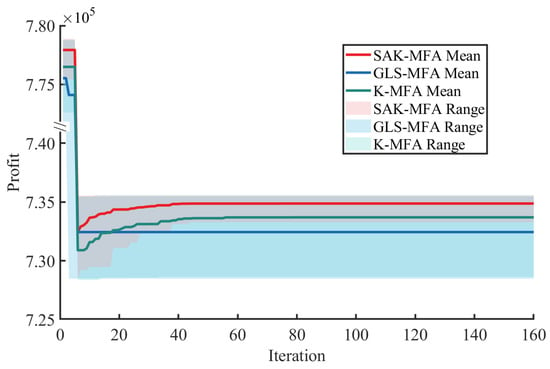

The performance of three strategies with the results of 30 independent runs is presented in Figure 3. The convergence profiles in Figure 3 illustrate the dynamic optimization process, while the box plot in Figure 4 summarizes the distribution of final profits achieved by each method.

Figure 3.

The comparison of optimization results.

Figure 4.

The statistical properties of optimization results.

Before analyzing the convergence curves, it is crucial to establish the metric for computational efficiency. To quantitatively evaluate computational efficiency, the primary metric in SBO is the total number of expensive high-fidelity simulations (Aspen Plus calls) required. A direct optimization approach using the MFA (population ) in Aspen Plus would require 30 simulations per iteration. In stark contrast, all three SBO frameworks (SAK-MFA, K-MFA, GLS-MFA) are designed to use only one high-fidelity simulation per iteration (for validation and dataset enrichment), representing a fundamental structural advantage.

As illustrated by the convergence curves, the proposed SAK-MFA strategy (red line) demonstrates superior performance on this metric. It converges to the highest profit level among the three methods and stabilizes efficiently after approximately 70 iterations. This corresponds to a total computational cost of approximately 70 high-fidelity Aspen Plus simulations. Compared to the estimated 2100 simulations (70 iterations × 30 calls per iteration) required by a direct optimization approach, our SAK-MFA framework achieves a computational cost reduction of nearly 96.7%. In contrast, the GLS-MFA strategy (blue line) shows a clear failure to converge. Its average profit stagnates early in the optimization process, while the wide solution envelope (the shaded area) indicates highly volatile, inconsistent performance across runs. This indicates the strategy struggles to escape an initial, suboptimal region of the search space. The baseline K-MFA strategy (green line) converges the fastest in approximately 49 iterations and costs the same amount of Aspen simulations. However, it does so prematurely to a significantly inferior local optimum, underscoring the inadequacy of a non-adaptive surrogate model with fixed hyperparameters. This comparison highlights that the SAK-MFA’s modest additional computational budget (an extra 21 simulations on average) was a necessary investment for the adaptive model to successfully avoid the local optimum and locate the true global solution.

The box plot in Figure 4 provides further statistical evidence of the SAK-MFA framework’s superiority and robustness. The SAK-MFA results exhibit a minimal interquartile range and overall variance by a relative standard deviation of only 0.037%, indicating that the method identified the high-quality optimal solution across all 30 runs. Its median profit is also visibly the highest among the three. Conversely, the GLS-MFA shows a wide distribution with a relative standard deviation of 0.266%, a large interquartile range, and long whiskers, highlighting its unreliability and high sensitivity to initial conditions. The K-MFA consistently converges to a distinctly suboptimal range of solutions by a relative standard deviation of 0.237%.

Table 4 summarizes the optimal operating parameters and corresponding performance metrics obtained by each optimization strategy. To ensure simulation validity in Aspen Plus, the stage 1 temperature and pressure were held constant across all strategies. The economic advantage of the SAK-MFA strategy is evident from the profit value of 778,530.200 monetary units, which exceeds the GLS-MFA result by 2388.056 units and the K-MFA result by 1320.22 units. While these differences may appear modest in percentage terms, they translate to significant annual savings in large-scale industrial operations.

Table 4.

Comparison of optimization results.

These aggregated results confirm the superior convergence properties and solution quality of the SAK-MFA approach. Specifically, the combination of achieving the highest average final profit of 778,530.200, coupled with an exceptionally low relative standard deviation of 0.037%, strongly indicates SAK-MFA’s ability to reliably escape the poor local optimum where the K-MFA strategy (relative standard deviation of 0.237%) consistently gets trapped. This demonstrates that SAK-MFA is more effective at exploring the entire search space and is less likely to get trapped in poor local optima.

Meanwhile, disturbances are inherently unavoidable in industrial production processes. These disturbances degrade the accuracy of the established surrogate model, thereby reducing the distillation column’s ability to achieve maximum economic performance. Consequently, effective optimization strategies must rapidly identify new optimal operating points when disturbances occur.

To evaluate optimization performance under disturbed conditions, we introduced a step change in the feed rate after the fifth iteration, reducing it from the initial value to 830 tonne/h. Figure 5 illustrates the optimization performance following this step change. SAK-MFA located the new optimal operating point more rapidly, achieving maximum economic benefits within fewer iterations. Once again, the GLS-MFA strategy fails to converge effectively, while the K-MFA strategy converges faster but only finds a local optimum.

Figure 5.

Optimization results after step change in feed rate.

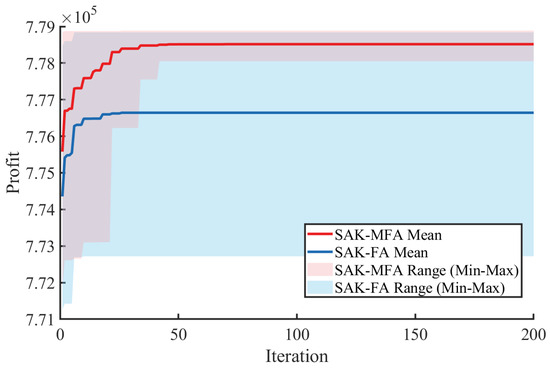

To evaluate the performance enhancement of MFA compared to the standard FA, the optimization results for the prefractionation column using both SAK-MFA and SAK-FA are presented in Figure 6. For the standard FA implementation, the attraction parameter was maintained at a common constant value of 0.5. The results demonstrate that MFA achieved superior optimization outcomes, evidenced by higher economic objective values. This performance difference validates the significance of the modifications introduced in the MFA, particularly its adaptive attraction mechanism compared to the fixed attraction parameter in standard FA. This comparison also addresses how the proposed framework compares to basic methods such as brute-force or random search. As established in the Introduction, a brute-force grid search is computationally infeasible for this problem. A simple random search (RS), while computationally feasible on the surrogate, is demonstrably inferior to the FA. Theoretically, the comprehensive FA review by reference [33] notes that the FA framework degenerates into a form of RS if its core attraction mechanism is removed (), implying the guided search is the critical component for performance. Empirically, FA is markedly more efficient than random search variants (such as intermittent search) [42]. Therefore, by demonstrating MFA’s superiority over standard FA (which is itself superior to RS), we have established that our guided search strategy is highly effective and necessary, validating its use over simpler, basic search methods.

Figure 6.

The optimization results of SAK with MFA and FA.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents an efficient surrogate-based optimization framework that addresses the computational challenges inherent in distillation processes by integrating a self-adaptive Kriging (SAK) model with a Modified Firefly Algorithm (MFA). The proposed SAK-MFA methodology demonstrated significant computational efficiency and superior effectiveness. Quantitatively, the framework proved its efficiency by reducing the required number of expensive high-fidelity simulations by over 96% compared to estimated direct optimization. Crucially, the SAK component enabled the framework to consistently achieve a higher average final profit than both the non-adaptive K-MFA and the GLS-MFA strategies, which converged prematurely to a poor local optimum. Furthermore, the SAK-MFA framework proved exceptionally stable, achieving a minimal relative standard deviation of only 0.037% over 30 independent runs, validating its superior performance and reliability for complex process optimization.

Several promising areas for future research have been identified: extension of the framework to handle more complex distillation configurations, including multiple columns and heat integration systems; integration of real-time optimization capabilities to address process dynamics and disturbances; and development of more sophisticated uncertainty quantification methods to enhance the robustness of optimization results under varying process conditions.

Author Contributions

Y.H.: Writing—Original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Validation. Q.J.: Writing—Review & Editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision. B.W.: Writing—Review & Editing, Methodology. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Crude oil feed flow rate (tonne/h) | Expected Improvement acquisition function | ||

| Crude oil feed temperature (°C) | Exploration-exploitation trade-off parameter | ||

| Reflux flow rate (tonne/h) | Standard normal Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) | ||

| Reflux temperature (°C) | Standard normal Probability Density Function (PDF) | ||

| Reflux accumulator feeding temp. (°C) | Std. deviation of Gaussian Process prediction | ||

| Column top section temperature (°C) | n | Population size of fireflies | |

| Column top section pressure (kPa) | n-dimensional uniform distribution vector | ||

| Column feeding section (stage 27) temp. (°C) | Position of firefly i | ||

| Column bottom (stage 28) temp. (°C) | Position of the best firefly (brightest) | ||

| Set of product streams {vapor, naphtha, bo} | Position of the worst firefly (dimmest) | ||

| s | Index for a product stream, | I | Light intensity of a firefly |

| Flow rate of product stream s (tonne/h) | Original (base) light intensity | ||

| Operational profit (unit/h) | Light absorption coefficient | ||

| Unit price of product stream s (unit/tonne) | Spatial distance between firefly i and j | ||

| Unit price of crude oil (unit/tonne) | Attractiveness of a firefly (FA) | ||

| Lower and upper bounds of the feasible region | Base attractiveness coefficient | ||

| x | Input vector of decision variables | Step size factor (dynamic in MFA) | |

| Kriging model prediction at point x | Percentage of re-initialized fireflies | ||

| Trend component (polynomial) of Kriging model | Input and output training datasets | ||

| Stochastic process (deviation) component | Initial sampled data subset for training | ||

| Variance of the stochastic process | t | Iteration counter | |

| Correlation function | Stopping criterion (number of stable iterations) | ||

| Vector of correlation hyperparameters | Profit by high-fidelity simulation (unit/h) | ||

| j-th correlation hyperparameter | Kriging model for the j-th output |

References

- Ye, L.; Zhang, N.; Li, G.; Gu, D.; Lu, J.; Lou, Y. Intelligent Optimization Design of Distillation Columns Using Surrogate Models Based on GA-BP. Processes 2023, 11, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Shi, X.; IEEE. Crude Oil Distillation Optimization Using Surrogate-aided Constrained Evolutionary Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Wellington, New Zealand, 10–13 June 2019; pp. 1118–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, D.; Jobson, M.; Li, J.; Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Optimization-Based Design of Crude Oil Distillation Units Using Surrogate Column Models and a Support Vector Machine. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2018, 134, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keßler, T.; Kunde, C.; Mertens, N.; Michaels, D.; Kienle, A. Global Optimization of Distillation Columns Using Surrogate Models. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzoi, R.E.; Menezes, B.C.; Kelly, J.D.; Gut, J.A.W.; Grossmann, I.E. Cutpoint Temperature Surrogate Modeling for Distillation Yields and Properties. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 18616–18628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Sahinidis, N.V.; Bindlish, R.; Bury, S.J.; Haghpanah, R.; Rajagopalan, S. Data-Driven Strategies for Extractive Distillation Unit Optimization. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2022, 167, 107970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, X.; Pei, Y.; Ren, H.; Choi, J.H. An Efficient Surrogate Model-Based Method for Deep-Towed Seismic System Optimization. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 268, 113463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Wang, X.; Gao, K.; Jin, Y.; Ding, J.; Chai, T. Evolutionary Optimization of High-Dimensional Multiobjective and Many-Objective Expensive Problems Assisted by a Dropout Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 52, 2084–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, Q.; Gielen, G.G.E. A Gaussian Process Surrogate Model Assisted Evolutionary Algorithm for Medium Scale Expensive Optimization Problems. IEEE Trans. Evol. Computat. 2014, 18, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Pedemonte, M.; Tories, A.I. A Genetic Programming Approach for Construction of Surrogate Models. Comput. Aided Chem. Eng. 2019, 47, 451–456. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, K.; Sanchez Medina, E.I.; Sundmacher, K. Hybrid Semi-parametric Modeling in Separation Processes: A Review. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2020, 92, 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirante, N.; Javaloyes, J.; Caballero, J.A. Rigorous Design of Distillation Columns Using Surrogate Models Based on Kriging Interpolation. AIChE J. 2015, 61, 2169–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza-Abaid, A.; Jakobsen, J.P. Neural Network Programming: Integrating First Principles into Machine Learning Models. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2022, 163, 107858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandis, M.; Baratti, R.; Chebeir, J.; Tronci, S.; Romagnoli, J.A. Exploring Nontraditional LSTM Architectures for Modeling Demethanizer Column Operations. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2024, 183, 108591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, J.; Cui, M.; Chen, X.; Liu, Q.; Fei, Z.; Qiao, X. Surrogate Modeling-Based Multi-Objective Optimization for the Integrated Distillation Processes. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2021, 159, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksal, E.S.; Aydin, E. Physics Informed Piecewise Linear Neural Networks for Process Optimization. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2023, 174, 108244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuolale, F.N.; Zhang, J. Energy Efficiency Optimisation for Distillation Column Using Artificial Neural Network Models. Energy 2016, 106, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.E.; Williams, C.K.I. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Minh, L.Q.; Duong, P.L.T.; Lee, M. Global Sensitivity Analysis and Uncertainty Quantification of Crude Distillation Unit Using Surrogate Model Based on Gaussian Process Regression. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 5035–5044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirante, N.; Javaloyes, J.; Ruiz-Femenia, R.; Caballero, J.A. Optimization of Chemical Processes Using Surrogate Models Based on a Kriging Interpolation. Comput. Aided Chem. Eng. 2015, 37, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Tang, Q.Q.; He, C.; Chen, Q.L.; Zhang, B.J. Hybrid Modelling for Combined Design Optimization of CO2 Removal and Compression in Raw Natural Gas Treatment Complexes. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2021, 173, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, F. Developing New Products with Kernel Partial Least Squares Model Inversion. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2021, 155, 107537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Jang, K.; Cui, C.; Moon, I. Novel Control-Aware Fault Detection Approach for Non-Stationary Processes via Deep Learning-Based Dynamic Surrogate Modeling. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 172, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.D.; Kim, K.Y. Objective Function Proposed for Optimization of Convective Heat Transfer Devices. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2012, 55, 2792–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mei, J.; Wang, D.; Guo, Y.; Wu, L. A Novel Damage Identification Method for Steel Catenary Risers Based on a Novel CNN-GRU Model Optimized by PSO. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Shi, X.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Y. Optimization Design of Crude Oil Distillation Unit Using Bi-Level Surrogate Model. Front. Control Eng. 2023, 4, 1162318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Long, Z.; Luo, J.; He, Z.; Li, X. Data Driven State Monitoring of Maglev System With Experimental Analysis. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 79104–79113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.R.; Schonlau, M.; Welch, W.J. Efficient Global Optimization of Expensive Black-Box Functions. J. Glob. Optim. 1998, 13, 455–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, B.; Swersky, K.; Wang, Z.; Adams, R.P.; De Freitas, N. Taking the Human Out of the Loop: A Review of Bayesian Optimization. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 148–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, K. Optimal Control Approach for Nonlinear Chemical Processes with Uncertainty and Application to a Continuous Stirred-Tank Reactor Problem. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.; Liu, P.; Yin, J.; Zhang, C.; Chao, M. A QCQP-based Splitting SQP Algorithm for Two-Block Nonconvex Constrained Optimization Problems with Application. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2021, 390, 113368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.V.; Curtis, F.E.; Wang, H.; Wang, J. Inexact Sequential Quadratic Optimization with Penalty Parameter Updates within the QP Solver. SIAM J. Optim. 2020, 30, 1822–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fister, I.; Fister, I.; Yang, X.S.; Brest, J. A Comprehensive Review of Firefly Algorithms. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2013, 13, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitouni, F.; Harous, S.; Maamri, R. A Novel Quantum Firefly Algorithm for Global Optimization. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 8741–8759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, S.L.; Ngnotchouye, J.M.T. Firefly Algorithm for Discrete Optimization Problems: A Survey. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 21, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çimen, M.E.; Yalçın, Y. A Novel Hybrid Firefly–Whale Optimization Algorithm and Its Application to Optimization of MPC Parameters. Soft Comput. 2022, 26, 1845–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandomi, A.; Yang, X.S.; Talatahari, S.; Alavi, A. Firefly Algorithm with Chaos. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2013, 18, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, D.; Jobson, M.; Li, J.; Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Optimal Design of Flexible Heat-Integrated Crude Oil Distillation Units Using Surrogate Models. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2021, 165, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M. Large Sample Properties of Simulations Using Latin Hypercube Sampling. Technometrics 1987, 29, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Saves, P.; Lafage, R.; Bartoli, N.; Diouane, Y.; Bussemaker, J.; Lefebvre, T.; Hwang, J.T.; Morlier, J.; Martins, J.R. SMT 2.0: A Surrogate Modeling Toolbox with a Focus on Hierarchical and Mixed Variables Gaussian Processes. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2024, 188, 103571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S.; He, X. Firefly Algorithm: Recent Advances and Applications. Int. J. Swarm Intell. 2013, 1, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).