Abstract

This study focuses on the genesis mechanism of thermal anomalies in the southwestern part of the Anan Depression in the Erlian Basin. Based on magnetotelluric 3D inversion data, a high-resolution electrical resistivity structure model was constructed, revealing the spatial configuration of deep heat sources and thermal pathways. The main conclusions are as follows: (1) Magnetotelluric 3D imaging reveals an elliptical low-resistivity anomaly (Anomaly C: 20 km × 16 km × 5 km, 0–5 Ωm) at depths of ~10–15 km. This anomaly is interpreted as a hypersaline fluid (approximately 400 °C, ~1.5% volume fraction, 3–5 wt.% NaCl), acting as the primary heat source. (2) Upward migration along F1/F3 fault conduits (10–40 Ωm) establishes a continuous pathway to mid-depth reservoirs D1/D2 (~5 km, 5–10 Ωm) and shallow crust. An overlying high-resistivity caprock (40–100 Ωm) seals thermal energy, forming a convective “source-conduit-reservoir-cap” system. (3) Integrated seismic data reveal that heat from the Abaga volcanic melt supplements Anomaly C via conduction through these conduits, combining with mantle-derived heat to form a composite source. This research delineates the interacting genesis mechanism of “deep low-resistivity heat source—medium-low resistivity fault conduit—shallow low-resistivity reservoir—relatively high-resistivity cap rock” in the southwestern A’nan Sag, providing a scientific basis for optimizing geothermal exploration targets and assessing resource potential.

1. Introduction

Against the strategic backdrop of global energy transition, geothermal energy, as a crucial clean and renewable resource, has attracted growing strategic attention due to its abundant reserves, stable operation, and significant carbon reduction potential [1,2,3,4,5]. In recent years, China has implemented a series of intensive policies to pro-mote the standardized and scaled development of medium-deep geothermal resources [6,7,8,9]. Within this context, the Erlian Basin—distinguished by a prominent regional high-heat background—has emerged as a key target for medium-deep geothermal exploration in China [10,11,12]. Situated in the eastern segment of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB), the Erlian Basin is a typical Mesozoic continental rift basin, with geothermal measurement revealing multiple high-heat-flow anomalies (e.g., 109.5 ± 17 mW/m2 in the Manite Depression) [10,13]. Geophysical explorations, including Magnetotelluric (MT) surveys, further indicate the presence of deep-seated heat sources and thermal conductive pathways [14,15,16]. Specifically, in the southwestern A’nan Sag of this basin, measured terrestrial heat flow exceeds 100 mW/m2, signaling a significant thermal anomaly and substantial potential for geothermal resource exploitation. However, the genetic mechanisms underlying this thermal anomaly remain unclear [10,11,16].

The MT technology, since its breakthrough in data processing and inversion algorithms in the 1980s, has become a pivotal tool for investigating deep electrical structures and key elements of geothermal systems [17,18,19,20]. For shallow thermal responses and heat transport mechanisms, Árnason et al. (2010) integrated MT with Transient Electromagnetic (TEM) data to reveal the linkage between shallow mineral alteration zones and deep magmatic heat sources in Iceland, establishing a quantitative model correlating resistivity with altered mineral content [21]; Araya et al. (2019) precisely delineated deep low-resistivity (<10 Ωm) geothermal fluid reservoirs via MT and elucidated high-permeability (>50 mD) fault-controlled thermal conduction-convection mechanisms connecting shallow systems to deep heat sources through anisotropy analysis [22]. Regarding thermal reservoir architecture and heat source localization, Gao et al. (2018) employed 3D MT inversion to construct a resistivity model of the Gonghe Basin, identifying the coupling relationship between heat sources and hydrothermal fluid channels [23]; He et al. (2016) combined AMT-MT joint exploration to comprehensively map the spatial distribution of thermal reservoirs, heat flow pathways, and magmatic heat source boundaries in the Mapamyum geothermal system [24]; Wu et al. (2018) systematically resolved the spatial configuration of the Zhangzhou Basin’s thermal structure and its magmatic-hydrothermal genetic coupling using multidimensional MT datasets [25]. In deep thermal state inversion, Hata et al. (2015) derived the mantle wedge temperature field (800–1200 °C) and partial melt fraction (5–15%) in the Kyushu subduction zone by integrating 3D MT electrical models with thermodynamic boundary constraints [26]; Sheng et al. (2020) fused 3D electrical architecture, Hashin–Shtrikman boundary constraints, and Arrhenius rheological equations to reconstruct the upper mantle thermal evolution model in the eastern Gangdese, jointly inverting temperature gradient fields at 30–100 km depths with surface heat flow data [27].

Given the significant resource potential associated with the high-heat-flow anomaly in the southwestern A’nan Sag and the critical need to understand its controlling mechanisms for effective exploration targeting and regional geothermal assessment, this study employs 3D MT inversion technology to obtain a high-resolution sub-surface resistivity structure of the study area, providing critical electrical constraints for thermal anomaly genesis analysis. Based on the derived 3D resistivity model, we identify key structural features controlling thermal anomalies and establish a correlation model of geothermal system elements (integrating heat source, reservoirs, caprocks, and conduits) in the southwestern A’nan Sag, elucidating their spatial configuration. Finally, by integrating resistivity structures with the correlation model, we systematically analyze the nature of deep heat sources and dominant controlling factors in heat transfer processes, ultimately revealing the genetic mechanism of high-heat-flow anomalies. This research provides a geophysical basis for optimizing geothermal exploration targets in the southwestern A’nan Sag and establishes a scientific foundation for assessing the overall geothermal resource potential of the Erlian Basin.

2. Overview of Regional Geology

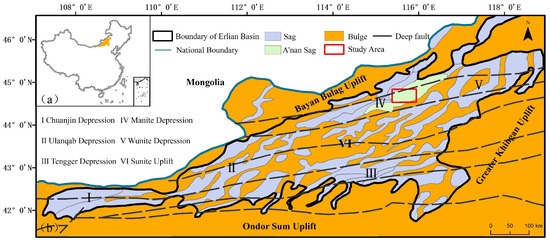

The Erlian Basin, situated in the north-central Inner Mongolia Plateau, covers a total area of ~105 km2 [28]. This basin developed atop the suture zone between the Asian and Siberian plates, representing a typical NE-trending Cretaceous rift basin [10,28,29,30]. Its dominant NE-oriented tectonic framework controls the distribution of first-order structural units, forming a fundamental pattern termed “five depressions and one up-lift” [29]. The internal architecture is complex, with 53 sags and 21 uplifts arranged alternately, making it one of China’s major onshore sedimentary basins [13,30,31]. The A’nan Sag, located in the northeastern part of the Manite Depression, is adjacent to the Sonid Up-lift to its southeast (Figure 1). This sag exhibits an elongated NE-trending morphology, characterized as a fault-sag superimposed depression with an area of ~2100 km2 [32]. It ranks among the largest and most hydrocarbon-rich sags within the Erlian Basin [32,33,34,35]. Internally, the sag features complex structures, including multiple sub-sags and uplifts [32]. Among these, the A’nan Sub-sag serves as the primary trough, covering an area of ~375 km2 with a maximum basement depth of ~4700 m [33]. The Late Paleozoic basement in the A’nan Sub-sag consists of arc-related tuffs and serpentinized ultramafic rocks, overlain by thick Lower Cretaceous and Cenozoic sedimentary sequences [34,36,37,38].

Figure 1.

(a) The location of the Erlian Basin; (b) structural units division map of the Erlian Basin.

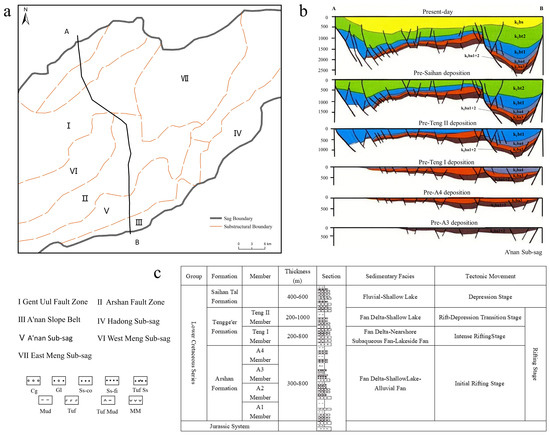

The tectonic evolution of the A’nan Sag has been jointly controlled by Yanshanian tectonic movements and the Paleozoic basement, resulting in the present-day structural framework (Figure 2a) [29,32]. This framework comprises three positive structural units (Jing-tewula Fault Zone, Aershan Fault Zone and A’nan Slope Belt) and four negative structural units (A’nan Sub-sag, Shadong Sub-sag, Mengdong Sub-sag and Mengxi Sub-sag) [33]. The evolutionary sequence can be divided into five main stages: (1) the Late Paleozoic–Triassic Basement Uplift and Denudation Phase, which established the crystalline basement framework [29]; (2) the Early Jurassic Initial Rifting Phase, forming fault-bounded lacustrine basins filled with coal-bearing clastic rocks [39]; (3) the Late Jurassic Compression–Thrusting Phase, characterized by basement-involved fold-thrust belts accompanied by basement-involved fold-thrust belts accompanied by predominantly basaltic to andesitic volcanic activity that modified the pre-existing structural configuration [29,40]; (4) the Early Cretaceous Intense Rifting and Subsidence Phase (Main Ba-sin-Forming Period), featuring sustained basement extension that generated half-graben systems with rapid accumulation of thick oil-bearing clastic rocks (Bayanhua Group, K1b), including sub-stages of fault reactivation controlling secondary unit formation, migration of depocenters, widespread lake transgression, and shallow-water deposits in extensive lacustrine basins [36,41]; and (5) the Saihantala Formation (K1bs) Decline and Post-rift Modification Phase, marked by regional uplift inducing lake-basin shrinkage transitioning to fluvial–swamp facies, with Late Yanshanian faulting and volcanic eruptions establishing the present-day structural geomorphology of the sag (Figure 2b) [15,29,42,43].

Figure 2.

(a) Tectonic division map of the A’nan Sag, modified from Zhang et al. (2025) [44]; (b) Schematic geological sections across the A’nan Sag, refers to Sun et al. (2017) [45]; (c) generalized stratigraphic column of the A’nan Sag, modified from Sun et al. (2001) [46].

The A’nan Sag is a typical Mesozoic continental rift basin lacking Triassic deposits, with a maximum basement burial depth exceeding 3500 m (Figure 2c) [32]. The primary sedimentary cover consists of the Lower Cretaceous Bayanhua Group (K1b), subdivided ascendingly into the Arshan Formation (K1ba), Tenggeer Formation (K1bt), and Saihantala Formation (K1bs) [41,44]. The Paleozoic (PZ) fold basement comprises metamorphic sequences, tuffs (interbedded Late Paleozoic basic/intermediate volcanic rocks), and localized serpentinites and rhyolites, with intermediate tuffs exhibiting reservoir potential [29,32]. The Jurassic system (J) is dominated by volcaniclastic rocks and coal-bearing sandy mudstones, overlying the basement via an angular unconformity [40]. The Cretaceous Arshan Formation (K1ba) records initial rift infill: its lower part (K1ba1) features conglomerates and variegated sandstones; the middle part (K1ba2) consists of grayish-green lacustrine mudstones; and the upper part (K1ba3) comprises light-gray breccias and sandy conglomerates interbedded with dark mudstones, serving as the primary oil-bearing and geothermal reservoir unit [13,36,47]. The Tenggeer Formation (K1bt), deposited during the main syn-rift subsidence phase, includes the Tenggeer Member 1 (K1bt1), characterized by strongly reducing deep-to-semi-deep lacustrine facies, with gray sandstone-mudstone intercalations, tuff layers, and dark gray mudstones, constituting both the key hydrocarbon reservoir and regional seal; the Tenggeer Member 2 (K1bt2) formed in shallow-water extensive basins, with lower sandy conglomerates to fine sandstones and upper gray mudstones acting as a critical regional caprock [36,37,48]. The Saihantala Formation (K1bs) reflects rift decline with fluvial-swamp facies, exhibiting interbedded conglomerates, sandstones, siltstones, and mudstones, contacting the underlying Tenggeer Formation via an angular unconformity [32]. The Cenozoic lacks Paleogene and Neogene strata; the Quaternary (Q) comprises grayish-yellow gravelly clays (alluvial-proluvial origin, <35 m thickness) with localized basalt lenses or thin layers, unconformably overlying pre-existing units [29].

3. Data Acquisition and Processing

3.1. MT Data Acquisition

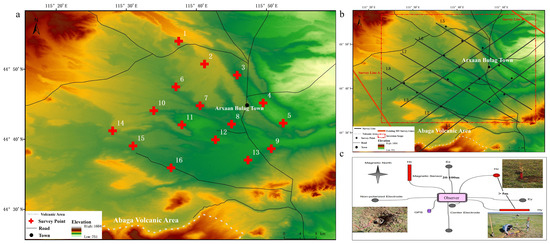

To investigate the deep-seated genetic mechanism of thermal anomalies in the southwestern A’nan Sag, this study systematically deployed 16 MT stations within the target area (44°30′–44°50′ N, 115°28′–115°52′ E; coverage 1024 km2), organized into eight survey profiles (Figure 3a,b). With an average station spacing of ~8 km, a Phoenix Geophysics MTU-5A system was employed to acquire horizontal electric field components (Ex, Ey) and horizontal magnetic field components (Hx, Hy) (Figure 3c). Continuous observation at each station lasted for ≥20 h, with a frequency range spanning 0.001–320 Hz, enabling high-resolution imaging of deep-seated heat sources and heat-controlling structures. Field operations strictly adhered to the following technical protocols: (1) Site Selection and Interference Mitigation: Flat terrains (<10% slope) with homogeneous surficial soils were prioritized; high-voltage lines (>500 m buffer), rail-ways (>200 m buffer), high-population areas, and significant near-surface heterogeneities were strictly avoided. (2) Sensor Deployment and Calibration: Electrodes were arranged in a cross-shaped array, with Ex aligned to magnetic north and electrode spacing optimized between 20–100 m based on ground conditions; horizontal magnetic probes (Hx, Hy) were orthogonally buried at 25–30 cm depth with azimuthal deviations <1°, and all probes were leveled using precision spirit levels. (3) Grounding and Cable Layout: Electrode grounding resistance was maintained <2 KΩ through saline solution infusion and dry soil removal; signal cables were laid in a non-loop “serpentine pattern” to minimize inductive current interference. (4) Real-time Data Quality Control: Pre-acquisition tests (≥15 min) assessed ambient electromagnetic noise and instrument stability; continuous monitoring tracked electrode potential differences, magnetic field amplitudes, and real-time apparent resistivity-phase curves; data col-lection was halted immediately upon detecting anomalies (e.g., strong interference, electrode instability, curve distortion) for site reevaluation or sensor reconfiguration. This protocol, combining ultra-low-frequency signal acquisition (0.001 Hz) and systematic noise suppression measures, yielded high-quality MT datasets with optimal signal-to-noise ratios for deep subsurface probing. These data provide a robust foundation for subsequent 3D inversion to resolve key structures associated with thermal anomalies—such as low-resistivity fluid/melt migration pathways and heat-controlling fault zones—including geometry, spatial distribution, and resistivity attributes.

Figure 3.

(a) Distribution of magnetotelluric stations in the study area; (b) layout of magnetotelluric survey lines in the study area; (c) schematic diagram of phoenix geophysics MTU-5A system deployment.

3.2. Preprocessing of MT Data

To acquire high-precision MT data for deep thermal structure inversion and thermal anomaly genesis analysis in the southwestern A’nan Sag, this study implemented systematic preprocessing on the original time-series data. First, the data were converted into the frequency domain via Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). Subsequently, the impedance tensor was estimated using the SSMT2000 software, with Robust statistical weighting applied to effectively suppress non-Gaussian noise interference such as electromagnetic pulses and industrial harmonics. Further, the remote reference technique was applied by deploying a reference station in a low-noise background area (west of Abaga Volcano, <200 km from the study area) with synchronized observations. Cross-spectral density analysis between the reference and local magnetic field components was used to reconstruct the impedance tensor, effectively reducing incoherent local noise. This workflow significantly enhanced the data signal-to-noise ratio, reducing scatter in apparent resistivity curves for heavily disturbed sites and decreasing phase curve distortion points by ~70%.

To eliminate outliers and abrupt transitions in apparent resistivity and phase curves induced by residual interference, this study performed spectral editing through manual interactive power spectrum selection in MTEditor software (https://www.phoenixgeophysics.com/, accessed on 10 January 2025). For each frequency point, outlier data points in the raw power spectral estimates were rigorously screened and removed, followed by precise calculation of the impedance tensor via Robust statistical averaging to export high-quality apparent resistivity and phase data. During editing, phase data were assigned higher weighting to ensure physical consistency and smoothness, due to their critical constraint on shallow thermal reservoir boundary in-version. Post-editing analysis demonstrated substantial data quality improvement at representative stations: scatter in apparent resistivity curves decreased by 35%, and phase curve distortion points reduced by ~80%. The integrated noise suppression workflow—combining robust processing, remote reference, and spectral editing—significantly enhanced the reliability and accuracy of the impedance tensor, establishing a robust data foundation for high-resolution characterization of deep heat sources, low-resistivity thermal anomaly conduits, and heat-controlling structures.

4. Electrical Structure Characteristics of the Southwestern A’nan Sag

4.1. 3D Inversion Methods

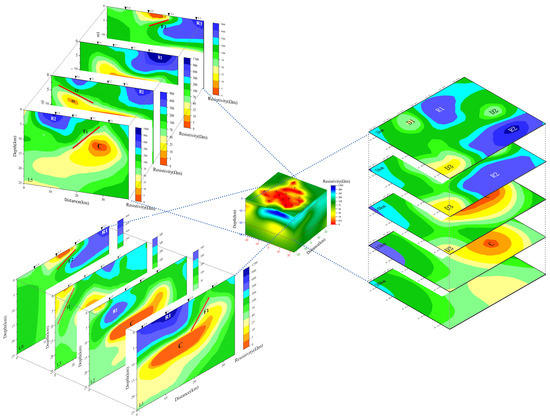

To resolve the electrical structure of the southwestern A’nan Sag with high fidelity, this study implemented high-resolution 3D inversion of 16 MT stations (42 frequencies spanning 0.000275–80 Hz) using the cloud computing system toPeak [49]. The inversion algorithm synergized dual engines of Occam inversion and Nonlinear Conjugate Gradient (NLCG) method within the ModEM framework. A homogeneous half-space with a background resistivity of 30 Ωm served as the initial model, and a multigrid optimization strategy was implemented to accelerate computation: coarse-grid inversion was first conducted to derive large-scale electrical features as prior constraints; subsequently, topological grid interpolation topologically mapped the prior model to a refined grid (32 × 32 × 83 cells, total 83,968) for fine-scale inversion. After 200 iterations, a high-precision 3D resistivity model with RMS = 1.27 was obtained (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

3D Inverted electrical resistivity structure model of the study.

For the shallow subsurface (0.5–1 km depth), a spurious low-resistivity layer—attributed to precipitation-induced pore fluid saturation (distribution spatially correlated with stations, absent elsewhere)—was identified based on anomaly patterns, corroborated by regional meteorological data and resistivity spatial discontinuities. To minimize shallow interference artifacts in deep thermal structure inversion, spatial interpolation of reliable deep resistivity data reconstructed shallow electrical parameters, ensuring the 3D model accurately reflects the primary thermal structure. This approach provides robust resistivity constraints for precise identification of deep heat source pathways.

4.2. 3D Electrical Structure Characteristics Analysis

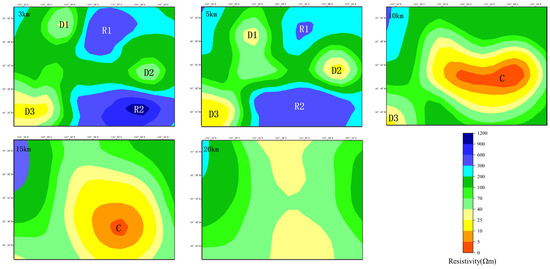

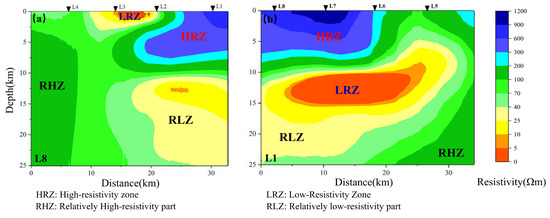

Based on the high-precision resistivity model obtained from 3D inversion, this study systematically reveals the electrical structure controlling thermal anomalies in the southwestern A’nan Sag by extracting horizontal slices at depths of 3 km, 5 km, 10 km, 15 km, and 20 km, combined with eight intersecting profiles (four NNE-striking lines L1–L4 and four NW-striking lines L5–L8) covering the core thermal anomaly zone (Figure 4). As illustrated in Figure 5, the horizontal slice analysis demonstrates significant vertical heterogeneity: (1) Shallow depths (3–5 km): Three low-resistivity zones (D1, D2, D3) exhibit spatial segregation from high-resistivity areas, with D1 and D2 showing progressively decreasing resistivity values and laterally expanding coverage with in-creasing depth, ultimately forming a vertical interconnection with the ultra-low-resistivity Anomaly C (0–5 Ωm) at 10 km depth. (2) Mid-depth (10 km): Anomaly C attains its maximum spatial extent, while a regionally extensive moderate-low resistivity background (10–40 Ωm) dominates the area. (3) Deep levels (15–20 km): Anomaly C diminishes in scale, and the regional moderate-low resistivity back-ground expands laterally at 15 km depth but contracts vertically from 15–20 km, ac-companied by a significant reduction or attenuation of the shallow high-resistivity background (>200 Ωm), likely associated with enhanced deep-seated partial melting processes.

Figure 5.

Horizontal slice maps at multiple depths of the 3D inversion model in the study area.

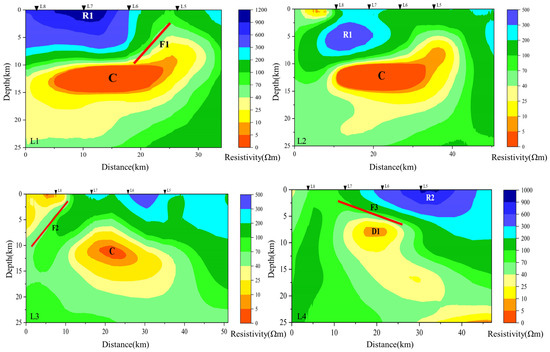

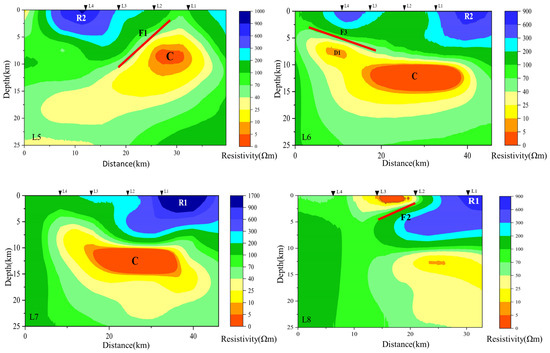

Vertical profile analysis further delineates the geometry of deep-seated heat sources (Anomalous Body C) and their structural connections. The NNE-striking profiles (L1–L4) reveal that: (1) Anomalous Body C (0–5 Ωm) is clearly defined at 10–15 km depths in profiles L1–L3; (2) It extends upward along faults (e.g., F1 in L1, F2 in L3), forming upward heat-conducting pathways while extending downward; (3) Its absence in the deep section of L4 indicates eastward pinch-out (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Cross sections along survey lines L1–L4 of the 3D inversion model in the study area.

The NW-striking profiles (L5–L8) demonstrate NNE-striking continuity of Anomaly C, with its spatial extent and geometry consistent with NNE-oriented profiles (L6 aligns with L1/L2), and reveal a shallow low-resistivity body D1 with L6 correlating with L4 in delineating this feature. Profile L8 displays a moderate-low resistivity zone (10–50 Ωm; Figure 7) but lacks a distinct deep Anomaly C (0–5 Ωm). All profiles resolve shallow high-resistivity domains (R1/R2), with partial sections revealing thermally conductive faults (F1, F2, F3). This electrical structure provides critical constraints for delineating shallow geothermal reservoir boundaries, characterizing deep-seated heat-conducting pathways, and clarifying the thermo-tectonic framework.

Figure 7.

Cross sections along survey lines L5–L8 of the 3D inversion model in the study area.

5. Genetic Mechanism Analysis of Thermal Anomalies in the Southwestern A’nan Sag Structure Characteristics of the Southwestern A’nan Sag

5.1. Analysis of the Geothermal System in the Study Area

5.1.1. Geoelectrical Model Analysis of the Study Area

The high-precision resistivity model constructed from 3D MT inversion reveals that the southwestern A’nan Sag exhibits electrical signatures typical of a convective geothermal system dominated by hydrothermal convection as the primary heat transfer mechanism [50,51]. Fracture systems act as conduits for hydrothermal fluid migration, facilitating vertical transport of deep geothermal energy. Deep-seated thermal fluids ascend along fractures to heat host rock pore fluids, establishing convective circulation through mixing with shallow cold groundwater [51]. The spatial heterogeneity of electromagnetic responses is primarily controlled by the fracture network: high-salinity fluids saturating fracture networks generate pronounced low-resistivity anomalies (typically <10 Ωm), while hydrothermal alteration under elevated temperatures induces resistivity reduction of 1–2 orders of magnitude in altered zones relative to the background (>100 Ωm) [52].

The 3D resistivity model delineates key electrical units: A significant low-resistivity Anomaly C (0–5 Ωm) is developed at 10–15 km depth, which is connected to shallow levels via deep-rooted fault zones. Under hydrothermal fluid upwelling influence, a relatively low-resistivity layer (<10 Ωm) forms in shallow strata above these fault zones. Notably, this shallow conductive layer is capped by a rock unit with resistivity values of 40–100 Ωm—higher than underlying strata but lower than the regional background (>200 Ωm) at equivalent depths. The model’s core characteristic lies in the effective spatial connectivity between deep Anomaly C and the shallow conductive layer through a moderate-low resistivity zone (10–40 Ωm). Vertical transects across fault zones reveal a sequential resistivity transition from deep to shallow: “Anomaly C—Moderate-low resistivity connectivity zone—Relatively low-resistivity layer—Relatively high-resistivity layer”. This complete vertical resistivity stratification and spatial connectivity further confirm that the study area conforms to the geoelectrical signature of a typical convective geothermal system.

5.1.2. Analysis of Heat Source in the Geothermal System

The 3D resistivity model derived from inversion identifies a significant low-resistivity Anomaly C (0–5 Ωm) at 10–15 km depth. This anomaly exhibits effective electrical connectivity with the shallow low-resistivity layer (5–10 Ωm) via a moderate-low resistivity channel (10–40 Ωm), indicating that it likely constitutes the deep-seated heat source of the geothermal system. Potential mechanisms for crustal low-resistivity anomalies include partial melting, saline fluids, or conductive mineral phases [53,54]. Given the regional scale of Anomaly C, while metal oxides and graphite layers typically manifest as localized small-scale features, they can be discounted as primary contributors. Although the study area is adjacent to the Abaga Volcanic Field and partial melting is commonly invoked to explain crustal low-resistivity in volcanic settings [55,56,57], the temperature at the depth of Anomaly C (10–15 km) is ~400 °C according to the 3D thermal structure model of East Asia by Sun et al. (2022) [58]. This temperature is substantially lower than the solidus of mafic rocks, precluding partial melting as a viable mechanism. Integrating these eliminative analyses, the low-resistivity characteristics of Anomaly C are primarily attributed to saline fluids [59,60].

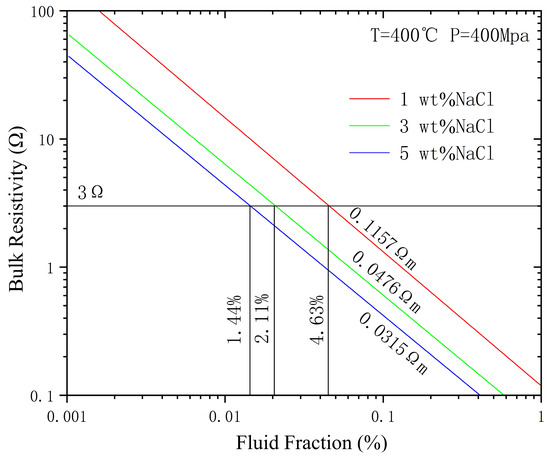

NaCl is the dominant solute in crustal fluids, with its mass fraction (wt%) defining the quantitative salinity metric [61]. The resistivity of saline fluids is primarily controlled by NaCl concentration while being modulated by temperature and pressure [61,62]. High-conductivity zones in the continental lower crust are commonly attributed to saline fluid accumulation, exhibiting NaCl concentrations of 0.2–7.0 wt% [63,64]. Anomaly C exhibits resistivity values of 0.1–5 Ωm (mean ~3 Ωm) at an in-situ temperature of ~400 °C (constrained by the East Asia thermal model) [58]. To quantify fluid salinity and content within Anomaly C, we employ the saline fluid resistivity relationship established by Dong et al. (2023) based on the Hashin–Shtrikman (H-S) model [14]. This function defines the quantitative correlation between rock resistivity, fluid volume fraction, NaCl salinity (1–5 wt%) at 400 °C and 400 MPa. As illustrated in Figure 8, for the mean resistivity of Anomaly C (3 Ωm), the required fluid volume fractions are approximately 1.44%, 2.11%, and 4.63% at NaCl salinities of 1 wt%, 3 wt%, and 5 wt%, respectively.

Figure 8.

Relationship between electrical resistivity and fluid fraction for 1 wt%, 3 wt%, and 5 wt% nacl saline fluids, modified from Dong et al. (2023) [14].

To validate the H-S model estimates, this study further applies Archie’s law to derive the porosity of the low-resistivity zone [65], assuming full saturation of rock voids, expressed as:

where: : porosity; : resistivity of the rock; : resistivity of the pore fluid; : cementation exponent, ranging between 1 and 2. Given that Anomaly C is situated at depths > 10 km under high-temperature–high-pressure conditions, the highly cemented rocks justify assigning = 1.

Based on the 3D resistivity inversion model, the country rock resistivity is constrained to ~200 Ωm, while Anomaly C exhibits resistivity values of 0–5 Ωm (mean: 3 Ωm). Substituting these parameters into Archie’s formula yields a porosity of ~1.5% for the low-resistivity zone. This value aligns with the range of 1.44% to 2.11% derived from the resistivity-salinity-fluid fraction relationship (Figure 8).

In summary, the electrical anomaly characteristics of low-resistivity Anomaly C can be reasonably explained by saline fluids with a fluid volume fraction of 1.5% and NaCl salinity of 3–5 wt%. T The in-situ temperature at anomaly depths is ~400 °C, and its sustained thermal energy contribution provides a stable deep heat source for regional geothermal resource accumulation. The porosity derived from Archie’s law (1.50%) exhibits close agreement with the fluid fraction range (1.44–2.11 vol%) calculated by the H-S model at 3–5 wt% salinity, corroborating the reliability of this quantitative interpretation.

5.1.3. Thermal Conduits of the Geothermal System

The fault system functions as dual conduits for thermal conduction and hydro-thermal transport in the formation of thermal anomalies within the study area, acting as a key control via spatiotemporal coupling with heat sources and thermal reservoirs [51]. Thermal energy from deep heat sources is primarily vertically advected along deep-seated fault zones, directly heating fluids and country rocks to form localized thermal anomalies [66,67,68]. The heated fluids subsequently migrate upward along secondary fractures or damage zones, undergo thermo-chemical exchange with shallow groundwater, potentially triggering surface thermal manifestations such as hot springs [69]. Within the tectonic context of a rift basin, the deep-seated fault system also forms the framework for conductive geothermal systems, significantly enhancing the vertical transfer efficiency of deep thermal energy and shaping efficient thermal reservoirs at shallow depths [66,70]. Based on MT inversion results, the F1 and F3 faults in the southwestern A’nan Sag are identified as regionally dominant thermal conductive faults. Their deep-seated characteristics effectively connect the deep low-resistivity Anomaly C with shallow low-resistivity zones, constituting the primary channels for hydrothermal fluid migration. In contrast, the F2 fault, constrained by its boundary conditions and resistivity structure evidence, exhibits no direct connectivity with the deep low-resistivity Anomaly C.

5.1.4. Reservoir and Caprock of the Geothermal System

The thermal reservoir is characterized by shallow low-resistivity anomalies (5–10 Ωm), indicating high-permeability volcaniclastic conglomerates and fractured sandstones enriched with geothermal fluids, with secondary porosity dominated by tectonic fractures. In contrast, the overlying cap rock exhibits relatively high resistivity (40–100 Ωm); although substantially exceeding the underlying reservoir’s resistivity, it remains markedly lower than the regional background resistivity at equivalent depths (>200 Ωm). Composed of low-permeability tight sandstones interbedded with argillaceous rocks, it functions as a thermal insulator through capillary pressure differentials and mineral thermal resistance effects, thereby inhibiting vertical heat dissipation and facilitating thermal energy accumulation within the reservoir.

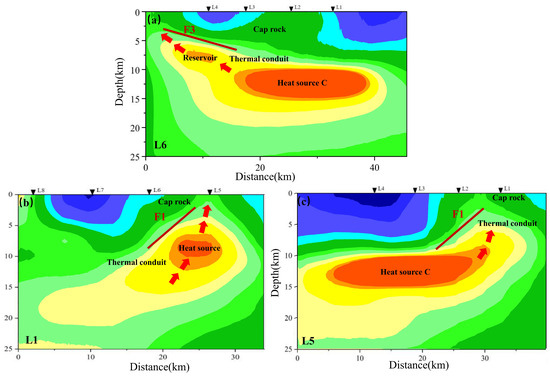

In summary, thermal energy from the deep heat source (low-resistivity Anomaly C) is primarily transported upward via thermal convection along fault F3, driving the convergence of geothermal fluids at ~7 km depth to form a low-resistivity thermal reservoir. Notably, from ~5 km depth to the surface, resistivity systematically increases with decreasing depth (Figure 9a). This electrical structure reveals a distinct transition in heat transfer mechanisms: fluid-dominated convection prevails at depths >5 km, whereas rock-conduction becomes predominant at shallower depths (<5 km). Furthermore, the resistivity profile across fault F1 (Figure 9b,c) displays a consistent vertical sequence: “deep low-resistivity heat source—moderate-low resistivity fault conduit (F1)—shallow low-resistivity reservoir—relatively high-resistivity cap rock”. The integrated electrical structure model formed by the F1 and F3 fault systems further confirms that the geothermal system in the study area aligns with the essential characteristics of a convective-type system.

Figure 9.

Geothermal system conceptual model of the study area. (a) profile l6-based structural-thermal model; (b) profile l1-based structural-thermal model; (c) profile l5-based structural-thermal model.

5.2. Analysis of Geothermal Anomaly Formation Mechanism

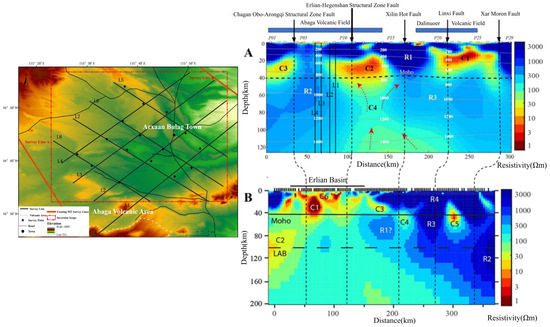

The deep heat source of the geothermal system corresponds to the prominent low-resistivity Anomaly C, with its thermal origin being pivotal to deciphering the genetic mechanism of regional thermal anomalies [15]. As a key parameter characterizing the electrical properties of the lithosphere, resistivity exhibits multi-parameter sensitivity to thermo-pressure regimes, mineral phase transitions, and structural architectures, rendering it an effective geophysical proxy for inverting deep thermal configurations [71,72,73]. MT inversion results from adjacent areas (Figure 10) reveal significant low-resistivity anomalies: Anomaly C2 in southwestern Profile A spans 15–40 km depth, while Anomaly C1 in northeastern Profile B develops at 10–40 km depth.

Figure 10.

(A) Distribution of magnetotelluric survey lines in the study and adjacent areas; (B) resistivity inversion profiles of lines A and B, modified from Ye et al. (2022) [74].

The resistivity section of Line L8 (Figure 11a), striking subparallel to Profile A, reveals an electrical structure divisible into low-resistivity zones, relatively low-resistivity zones, high-resistivity zones, and relatively high-resistivity zones. Spatial correlation analysis confirms high consistency between Profile A and Line L8, jointly exhibiting: (1) Shallow low-resistivity zone, (2) Eastern high-resistivity zone, (3) Subjacent moderate-low resistivity zone, (4) Western moderate-high resistivity zone, and (5) Central transitional zone. Integrated with Line L1 resistivity distribution (Figure 11b), this study confirms spatial continuity between the study area’s Anomaly C and the Abaga Volcanic Field Anomaly C2, connected through a moderate-low resistivity corridor (10–40 Ωm).

Figure 11.

(a) Resistivity layering profile along survey line l8; (b) resistivity layering Profile along Survey Line L1.

Regarding the genesis of low-resistivity Anomaly C2 in Profile A, saline fluids and partial melting constitute two primary explanatory mechanisms. However, Anomaly C is definitively attributed to hypersaline fluids. Critical differences exist in deep structural evidence, as S-wave velocity structure reveals extensive low-velocity anomalies at 20–40 km depth beneath the Abaga volcanic zone, whereas no significant velocity anomaly is detected at equivalent depths in the study area [75,76,77,78]. Liu et al.‘s (2017) ambient noise tomography study further confirms that shear wave velocities within 15–70 km depth beneath this volcanic zone are significantly lower than the minimum value predicted by global orogenic belt models [79]. Additionally, Qiang et al. (2019) shear wave splitting observations indicate an isotropic medium response without detectable splitting, thus suggesting localized mantle upwelling [75]. Integrating its prominent low-resistivity characteristics and ambient thermobaric conditions (exceeding the wet basalt solidus >800 °C), Anomaly C2 in the Abaga volcanic zone is conclusively attributed to partial melting, potentially underlain by a magma chamber. This geophysical evidence demonstrates that the partial melting layer and potential magma reservoirs at depth in the Abaga volcanic zone transmit mantle-derived melt heat and deep conductive heat to Anomaly C through a medium-low resistivity conduit (10–40 Ωm), forming a composite heat source mechanism. This hybrid mechanism provides sustained thermal energy flux to Anomaly C, driving the formation and evolution of regional thermal anomalies.

6. Conclusions

Based on the three-dimensional resistivity structure model of the southwestern A’nan Sag (Erlian Basin), constructed through (MT) data inversion and integrated analysis of key geothermal system elements and thermal anomaly genesis, the following conclusions are drawn:

- (1)

- MT 3D inversion reveals an elliptical low-resistivity Anomaly C at depths of 10–15 km depth, with dimensions of ~20 km (long axis) × 16 km (short axis) × 5 km (thickness). Among the major faults (F1, F2, F3), Anomaly C extends upward along F1 and F3 faults, forming medium-low resistivity conduits (10–40 Ωm) that culminate in shallow relatively low-resistivity layers D1/D2 at ~5 km depth (5–10 Ωm). These interconnected features establish a vertically continuous hydrothermal migration pathway extending to 0–3 km depth.

- (2)

- The deep-seated low-resistivity Anomaly C is primarily attributed to hypersaline fluids (1.50 vol%, 3–5 wt% NaCl) at ~400 °C, with an estimated temperature of ~400 °C, constituting the system’s core heat source. The mid-depth low-resistivity layers D1 and D2 function as the thermal reservoirs, characterized by fracture networks saturated with geothermal fluids. Overlying these, a relatively high-resistivity layer (40–100 Ωm) forms an effective caprock through low-permeability tight sandstones that suppress vertical heat dissipation. Faults F1/F3 dominate thermal energy transport, establishing a coherent “heat source–conduit–reservoir–cap” architecture that aligns with the defining characteristics of a typical convective-type geothermal system.

- (3)

- Integrated seismic S-wave velocity analysis reveals that the thermal energy derived from partial melt beneath the Abaga volcanic zone is supplied to Anomaly C via medium-low resistivity conduits (10–40 Ωm) primarily through thermal conduction. Superimposed with deep mantle conductive heat, forms a stable composite heat source. Driven by the fault systems, thermal energy is transported to shallow crustal levels through a coupled conduction-convection mode, generating and sustaining regional thermal anomalies.

Building on this initial analysis of the 3D resistivity structure and heat source mechanism, future research will focus on: (1) enhancing geological constraints through systematic exploration (core sampling, precision logging) to refine thermal reservoir modeling and quantify fault-controlled heat transfer; (2) advancing multi-physics coupling by integrating seismic velocity, gravity-magnetic data for joint inversion, combined with geochemical tracing of geothermal fluids, to resolve the spatiotemporal linkage between the deep heat source (Anomaly C) and fault systems (F1–F3); (3) establishing a volcano-geothermal coupling model centered on the Abaga volcanic zone, deploying integrated surveys to characterize the hierarchical development of shallow convective and mid-deep conductive-convective reservoirs, ultimately constructing a sustainable exploitation framework for regional geothermal resources.

Author Contributions

For research conceptualization, S.W. and W.X.; methodology, S.W. and T.G.; software, T.G. and S.W.; validation, S.W., W.D. and Z.W.; formal analysis, S.W.; investigation, T.G. and S.W.; data curation, T.G.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G. and S.W.; writing—review and editing, S.W.; visualization, S.W.; supervision, W.X., W.D. and S.W.; project administration, W.X.; funding acquisition, W.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant No. 42172335.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Wei Xu) upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Our heartfelt gratitude is given to the editor and the reviewers for their scientific and linguistic revisions of the manuscript. We also sincerely thank Jiong Zhang (National Institute of Natural Hazards, Ministry of Emergency Management of China) and Ruoli Wang for his professional guidance on magnetotelluric data inversion in the A’nan Sag.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Krieger, M.; Kurek, K.A.; Brommer, M. Global geothermal industry data collection: A systematic review. Geothermics 2022, 104, 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Zwaan, B.; Dalla Longa, F. Integrated assessment projections for global geothermal energy use. Geothermics 2019, 82, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharathi N, K.; Abirami, M.; Vighneshwari, D.; Hariprasath, M. Techno-economic optimization of hybrid renewable systems for sustainable energy solutions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarczyk, M.; Sowiżdżał, A. Environmental and Social Dimensions of Energy Transformation Using Geothermal Energy. Energies 2025, 18, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellabban, O.; Abu-Rub, H.; Blaabjerg, F. Renewable energy resources: Current status, future prospects and their enabling technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 748–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Sun, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, D. Geothermal resource distribution and prospects for development and utilization in China. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2024, 11, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, J.; Tjiawi, H.; Chidire, A.; Veerasamy, B.B.; Massier, T.; Romagnoli, A.; Wu, W.; Lu, D.; Lim, J.W.M.; Yang, L.; et al. Geothermal development in South, Southeast and East Asia: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 209, 115043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dou, J.; Li, M.; Zeng, M. Geothermal energy in China: Status, challenges, and policy recommendations. Util. Policy 2020, 64, 101020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.L.; Hu, K.Y.; Lu, X.L.; Huang, X.X.; Liu, K.T.; Wu, X.J. A review of geothermal energy resources, development, and applications in China: Current status and prospects. Energy 2015, 93, 466–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Huang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ke, T.; Yu, R.; Li, Y. Geothermal gradient and heat flow of the Erlian Basin and adjacent areas, Northern China: Geodynamic implication. Geothermics 2021, 92, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Thermo-tectonic evolution of the northern Erlian Basin (NE China): Evidence from fission track and (U–Th)/He thermochronology. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2023, 248, 105620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Wang, C.; Tang, S.; Hao, Q. Mesozoic and Cenozoic thermal history and source rock thermal evolution of the Baiyinchagan sag, Erlian Basin, Northern China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2016, 139, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Liu, Z.; Song, L.; Ge, J.; Tian, N.; Yin, K.; Wang, X. A new division of late Cretaceous Erlian Basin tectonic units based on differential basement characteristics. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 245, 213536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Zhan, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Li, N.; Han, B.; Sun, X.; Liu, X.; Tang, J. Electrical resistivity structure across the Late Cenozoic Abaga-Dalinor volcanic field, eastern China, from 3-D magnetotelluric imaging and its tectonic implications. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2023, 258, 105574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Fu, H.; Jin, S.; Wei, W. Magnetotelluric study of the mechanism of the Abaga and Dalinor volcanic groups in Central Inner Mongolia, China. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2020, 308, 106570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, S.; Zuo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Duan, W.; Wei, X. Terrestrial heat flow in the baiyinchagan sag, erlian Basin, northern China. Geothermics 2020, 86, 101799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, G. Exploring for Geothermal Resources with Electromagnetic Methods. Surv. Geophys. 2014, 35, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H.; Yin, C.C.; Cai, J.; Huang, W.; Ben, F.; Zhang, B.; Qi, Y.F.; Qiu, C.K.; Ren, X.Y.; Huang, X.; et al. Review on research of electrical anisotropy in electromagnetic prospecting. Chin. J. Geophys.-Chin. Ed. 2018, 61, 3468–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.T.; Ren, Z.Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, L.C.; Yuan, Y.; Xiao, X. Frequency-domain electromagnetic methods for exploration of the shallow subsurface: A review. Chin. J. Geophys.-Chin. Ed. 2015, 58, 2681–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanassoulas, C. Geothermal-Exploration Using Electrical Methods. Geoexploration 1991, 27, 321–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Árnason, K.; Eysteinsson, H.; Hersir, G.P. Joint 1D inversion of TEM and MT data and 3D inversion of MT data in the Hengill area, SW Iceland. Geothermics 2010, 39, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya Vargas, J.; Meqbel, N.M.; Ritter, O.; Brasse, H.; Weckmann, U.; Yáñez, G.; Godoy, B. Fluid Distribution in the Central Andes Subduction Zone Imaged with Magnetotellurics. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2019, 124, 4017–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Cheng, Z.; Jia, X.; Li, S.; Fu, L.; Gao, L.; Xin, H. Three-dimensional magnetotelluric imaging of the geothermal system beneath the Gonghe Basin, Northeast Tibetan Plateau. Geothermics 2018, 76, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Chen, L.; Dorji; Xi, X.; Zhao, X.; Chen, R.; Yao, H. Mapping the Geothermal System Using AMT and MT in the Mapamyum (QP) Field, Lake Manasarovar, Southwestern Tibet. Energies 2016, 9, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Hu, X.; Wang, G.; Xi, Y.; Lin, W.; Liu, S.; Yang, B.; Cai, J. Magnetotelluric Imaging of the Zhangzhou Basin Geothermal Zone, Southeastern China. Energies 2018, 11, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, M.; Uyeshima, M. Temperature and melt fraction distributions in a mantle wedge determined from the electrical conductivity structure: Application to one nonvolcanic and two volcanic regions in the Kyushu subduction zone, Japan. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 2709–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Jin, S.; Lei, L.; Dong, H.; Zhang, L.; Wei, W.; Ye, G.; Li, B.; Lu, Z. Deep thermal state on the eastern margin of the Lhasa-Gangdese belt and its constraints on tectonic dynamics based on the 3-D electrical model. Tectonophysics 2020, 793, 228606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnetti, C.; Malartre, F.; Huault, V.; Cuney, M.; Bourlange, S.; Liu, X.D.; Peng, Y.B. Sedimentology, stratigraphy and palynological occurrences of the late Cretaceous Erlian Formation, Erlian Basin, Inner Mongolia, People’s Republic of China. Cretac. Res. 2014, 48, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Fu, S.; Jiang, S.; Yao, N.; Wang, X. New understandings of the basement characteristics and evolution process of Erlian Basin. Oil Geophys. Prospect. 2019, 54, 404–416. [Google Scholar]

- Yongqian, C.U.I.; Hengmao, T.; Xianping, L.I.; Zhen, L.I.U.; Hongbo, Z.; Changjiang, D.U. Tectonic Mechanism of the Erlian Basin during Early Yanshanian and Speculation on the Basin Prototype. Acta Geol. Sin. 2011, 85, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Coupling relationship of Mesozoic-Cenozoic Basin and Mountains in the Erlian Basin. Spec. Oil Gas Reserv. 2011, 18, 60–63,138. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Song, T.; Li, X.; Yan, W.; Wang, J.; Zhong, X. Accumulation features and formation conditions of tight oil reservoir in A’nan Sag, Erlian Basin, China. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2016, 27, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Ma, L.; Sun, F. Exploration prospects of low-mature oil/gas in the shallow layers of the A’nan Sag, the Erlian Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2007, 28, 610–614,633. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Zhang, T.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, T.; Li, B.; Li, C. Characteristics and main controlling factors of tight oil reservoirs in Cretaceous Tengger Formation, A’nan Sag, Erlian Basin. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2021, 43, 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Weiliang, D.U.; Xianping, L.I.; Yang, X.; Jiuqiang, Z.; Yahui, L.U.; Shunping, Y.U. Reverse Structures in Erlian Basin and Their Relations with Hydrocarbon. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2007, 25, 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Shou, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, B.; Zhang, T.; Lan, B. Petrophysical property limits of effective tight oil reservoirs in the lower part of the first member of Cretaceous Tengger Formation, A’nan Sag, Erlian Basin, North China. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2016, 38, 551–558. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, X.; Dan, W.N.; Lu, S.F.; Zhang, P.F.; Li, B.; Cao, L.Z.; Wei, Y.; Li, X.W.; Fan, J.; Wang, J.J.; et al. Insight into Fluid Occurrence and Pore Structure of Lacustrine Shale from the Cretaceous Tengger Formation, A’nan Sag, Erlian Basin, China. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 12960–12977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Chang, F.; Jiang, B.Y.; Li, C.; Dai, X.D.; Li, C.H. Study on Hydrocarbon Accumulation Law in Erlian Basin China. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2021, 30, 6277–6284. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Shao, L.Y.; Wang, D.D.; Sun, Q.P.; Sun, B.; Lu, J. Sequence stratigraphy and coal accumulation of Lower Cretaceous coal-bearing series in Erlian Basin, northeastern China. AAPG Bull. 2019, 103, 1653–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.X.; Zhao, X.Z.; Yang, Y.T.; Zhang, R.F.; Han, C.Y.; Shi, Y.P.; Jiang, S.Q.; Tao, M.H. Jurassic-earliest Cretaceous tectonostratigraphic evolution of the Erlian Basin, Northeast China: Records of polyphase intracontinental deformation in Northeast Asia. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2018, 96, 405–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Guo, Z.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, M. Upper Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous Stratigraphy in the Middle Wuliyasitai Depression, Erlian Basin: Evidence from Zircon U-Pb Dating. J. Stratigr. 2017, 41, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.F.; Yue, H.; Zhu, X.M.; Sun, S.Y.; Wei, W.; Liu, X.; Jia, Y. Dolomitization of felsic volcaniclastic rocks in continental strata: A study from the Lower Cretaceous of the A’nan Sag in Er’lian Basin, China. Sediment. Geol. 2017, 353, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.W.; Cui, F.R.; Zhao, Z.D.; Bai, Z.D.; Chang, Z.G.; Zhao, J.X. First Optically Stimulated Luminescence and Radiocarbon Dating of the Late Quaternary Eruptions in the Xilinhot Volcanic Field, China. Minerals 2024, 14, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Lu, S.; Wu, H.; Liu, C.; Gao, W.; Li, W.; Zhou, N.; Chen, G.; Wu, C.; et al. Geochemical characteristics and paleo-environment of Lower Cretaceous lacustrine shale in the A’nan Sag, Erlian Basin, Northern China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2025, 178, 107420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Qian, Z.; Lu, X.; Guo, Q.; Xu, J.; Shi, Y.; Hu, W. Reservoir property of the special lithologic section in the lower Tengger Formation of Anan depression, ErIian basin. Geol. Bull. China 2017, 36, 644–653. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Hong, Y.; Wu, Q.; Gan, C. Seismic characteristics of the gas reservoir in A’nan Sag of Erlian Basin. Tianranqi Gongye Nat. Gas Ind. 2001, 21, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, B. Characteristics and favorable zone distribution of tuff reservoirt of Cretaceous in A’nan sag, Erlian Basin. Lithol. Reserv. 2024, 36, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, H.Z.; Chen, K.Y.; Qi, Z.Y.; Chen, D.; Chen, W.L. Geochemical characteristics and genetic mechanism of dolomitic rocks in tengger formation in A’nan sag, China. Chim. Oggi-Chem. TODAY 2016, 34, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Cai, J.; Cui, T.; Zhao, G.; Tang, J.; Ouyang, B. The Design and Application of Topeak: A Threedimensional Magnetotelluric Inversion Cloud Computing System. Seismol. Geol. 2022, 44, 802–820. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, J.; He, Z.; Li, P. Classification of geothermal systems and their formation key factors. Earth Sci. Front. 2017, 24, 190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Lin, W. Main hydro-geothermal systems and their genetic models in China. Acta Geol. Sin. 2020, 94, 1923–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, S.P.; Fu, R.; Tang, X.Y. Application of magnetotellurics in geothermal exploration and research in volcano areas. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2017, 33, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.L. Lithosphere thickness controls the extent of mantle melting, depth of melt extraction and basalt compositions in all tectonic settings on Earth—A review and new perspectives. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 217, 103614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Xu, Y.X.; Yang, B.; Guo, Z.Q.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Y. Deciphering Fine Electrical Conductivity Structures in the Crust from MT Data Using the Equivalent Conductivity Formula. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2021, 126, e2021JB022519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeau, M.J.; Unsworth, M.J.; Cordell, D. New constraints on the magma distribution and composition beneath Volcan Uturuncu and the southern Bolivian Altiplano from magnetotelluric data. Geosphere 2016, 12, 1391–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, H.J.; Zhang, S.Q.; Xin, H.L.; Li, Z.W.; Tian, W.; Bao, F.; Cheng, Z.P.; Jia, X.F.; Fu, L. Magma recharging beneath the Weishan volcano of the intraplate Wudalianchi volcanic field, northeast China, implied from 3-D magnetotelluric imaging. Geology 2020, 48, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.M.; Kang, G.F.; Bai, C.H.; Gao, G.M. Studies on the relationships of the Curie surface with heat flow and crustal structures in Yunnan Province, China, and its adjacent areas. Earth Planets Space 2019, 71, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.J.; Dong, S.W.; Wang, X.Q.; Liu, M.A.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Y.L. Three-Dimensional Thermal Structure of East Asian Continental Lithosphere. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2021JB023432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feucht, D.W.; Sheehan, A.F.; Bedrosian, P.A. Magnetotelluric Imaging of Lower Crustal Melt and Lithospheric Hydration in the Rocky Mountain Front Transition Zone, Colorado, USA. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2017, 122, 9489–9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.J.; Dong, S.W.; Liu, M.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Y.L. The rheological structure of East Asian continental lithosphere. Tectonophysics 2025, 895, 230575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinmyo, R.; Keppler, H. Electrical conductivity of NaCl-bearing aqueous fluids to 600 °C and 1 GPa. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2017, 172, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.H.; Keppler, H. Electrical Conductivity of NaCl-Bearing Aqueous Fluids to 900°C and 5GPa. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2019, 124, 1397–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, C. The physical and chemical evolution of low-salinity magmatic fluids at the porphyry to epithermal transition: A thermodynamic study. Miner. Depos. 2005, 39, 864–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, H.; Ichiki, M. Electrical conductivity of NaCl-H2O fluid in the crust. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2016, 121, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucok, H.; Ershaghi, I.; Olhoeft, G.R. Electrical-Resistivity of Geothermal Brines. J. Pet. Technol. 1980, 32, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lin, W.; Liu, F.; Gan, H.; Wang, S.; Yue, G.; Long, X.; Liu, Y. Theory and survey practice of deep heat accumulation in geothermal system and exploration practice. Acta Geol. Sin. 2023, 97, 639–660. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, G.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Tang, X.; Ma, F.; Hu, S. Medium-high temperature geothermal resources in China: Exploration directions and optimizing prospecting targets. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2022, 40, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Lin, W. The thermal status of Chinas land areas and heat-control factors. Earth Sci. Front. 2024, 31, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, N.; Tang, B.; Zhu, C. Deep thermal background of hot spring distribution in the Chinese continent. Acta Geol. Sin. 2022, 96, 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.H.; Liu, J.X.; Ma, Z.Q.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, H. Development simulation in Gucheng County, Hebei Province: Comparative study of the thermal storage development of clastic and carbonate rocks. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2024, 11, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.K.; Wang, D.L.; Wang, T.Q.; Weng, A.H.; Li, Y.B.; Guo, J.H.; Wang, X.Q. Undulating electrical lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary beneath Northeast China; as revealed by long-period magnetotelluric data. Tectonophysics 2023, 851, 229770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Han, J.T.; Liu, L.J.; Hou, H.S.; Liu, W.Y.; Liu, G.X.; Liang, H.D.; Wu, Y.H.; Xin, Z.H. The deep section cutting through the Xing’an Mongolia Orogenic Belt: Lithospheric resistivity structure and modification model. Chin. J. Geophys.-Chin. Ed. 2023, 66, 1603–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanneson, C.; Unsworth, M.J.; Currie, C.A. Lithospheric thickness and the backarc-craton lithosphere step in southwestern Canada imaged by a 3D magnetotelluric study. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2025, 62, 843–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.F.; Xia, Z.H.; Unsworth, M.; Wei, W.B.; Jin, S.; Liu, Z.L. Ongoing Asthenospheric Upwelling and Delamination-Style Down-Welling Beneath Northeast China: Evidence from High-Resolution Magnetotelluric Profiles. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2021JB022100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Z.Y.; Wu, Q.J. Upper mantle anisotropy beneath Abag area in Inner Mongolia from shear wave splitting. Chin. J. Geophys.-Chin. Ed. 2019, 62, 2510–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wu, Q.J.; Zhang, R.Q.; Lei, J.S. Crustal structure beneath the Abaga area of Xing’an-Mongolia Orogenic Belt using teleseismic receiver functions. Chin. J. Geophys.-Chin. Ed. 2018, 61, 3676–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wu, Q. Crustal S-wave velocity structure of the Abaga area of Xing’an-Mongolia Orogenic Belt from ambient noise. Acta Seismol. Sin. 2025, 47, 54–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, J.; Wu, Q.J.; Yu, D.X.; Ye, Q.D.; Zhang, R.Q. Study on surface-wave tomography in Abaga volcanic area, Inner Mongolia. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1131393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.N.; Niu, F.L.; Chen, M.; Yang, W.C. 3-D crustal and uppermost mantle structure beneath NE China revealed by ambient noise adjoint tomography. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2017, 461, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).