Featured Application

Results from the present systematic review are applicable in the field of restorative dentistry. Differences in microleakage between glass ionomers and the factors that influence it are crucial for restorative material selection.

Abstract

This study aimed to perform a qualitative synthesis of the available in vitro evidence on the microleakage of commercially available conventional glass ionomer cements (GICs), resin-modified glass ionomer cements (RMGICs), and modified glass ionomer cements with nano-fillers, zirconia, or bioactive glasses. A systematic review was conducted according to the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) statement standards. The literature search was performed in Medline (via PubMed), Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus to identify relevant articles. Laboratory studies that evaluated microleakage of GICs, RMGICs, and modified glass ionomer cements with nano-fillers, zirconia, or bioactive glasses were eligible for inclusion. The QUIN risk of bias tool for the assessment of in vitro studies conducted in dentistry was used. After the study selection process, which included duplicate removal, title and abstract screening, and full-text assessment, 15 studies were included. A qualitative synthesis of the evidence is presented, including author data, year of publication, glass ionomer materials used, sample characteristics, microleakage technique and values, and main outcome measures for primary and permanent teeth. Although no statistically significant differences were found in numerous studies, most results showed that RMGICs exhibited less leakage than conventional GICs. All studies agreed that leakage was significantly higher at dentin margins. It was also higher at the gingival margin than at the occlusal margin. Nano-filled RMGICs Ketac N100, Equia Forte, and Zirconomer appear to have less microleakage than conventional GICs and RMGICs. Further investigations using a standardized procedure are needed to confirm the results.

Keywords:

dentistry; dental materials; glass ionomers; microleakage; in vitro; laboratory; systematic review 1. Introduction

Glass ionomer cements (GICs), developed during the late 1960s [1], are one of the most important groups of dental materials due to their ionic exchange with the dental substrate and their continuous fluoride release. GICs do not mimic tooth color or composites and show faster surface loss with wear. However, because they are less technique-sensitive, they may act as the material of choice in many restorative cases [2]. On the other hand, GICs not only possess a remineralizing action but can also increase their hardness in contact with the oral environment over time, and their ability to incorporate calcium and phosphate has been demonstrated by SEM-EDX, suggesting an additional mineralization process [3]. The main disadvantages attributed to GICs are their poor mechanical properties [4], poor esthetics due to their lack of translucency [5], and moisture sensitivity while setting [6]. GICs have undergone multiple modifications in their structure and composition to overcome these disadvantages, increasing their usefulness as restorative materials in dental treatments [7]. Among these modifications, the following can be highlighted: the incorporation of resin, usually 2-hydroxy-ethyl methacrylate (HEMA) [8]; metallic fiber particles [9,10], such as titanium dioxide, zirconia, or alumina nanoparticles [11,12,13]; and other inorganic compounds, such as hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite, or bioactive glass [14,15].

Resin-modified glass ionomer cements (RMGICs) were developed to improve the physical and mechanical properties of GICs [16]. These materials undergo a dual-setting reaction, the typical acid–base reaction of GICs, and photopolymerization [17]. The remineralizing potential of RMGICs can be improved by incorporating bioactive glasses into their composition, which also confer bioinductive and regenerative potential to the material [18]. The calcium-fluor-aluminosilicate content in the glass powder is responsible for the remineralizing ability of the materials [19]. Fluoride promotes the formation of fluorapatite, which is less soluble than hydroxyapatite [20]. When fluoride ions are released, they can saturate the liquid phase in and around the surface of the restorative tooth, resulting in the precipitation of CaF2 crystals, which reduces the chances of demineralization and accelerates the remineralization process [21]. This process can be considered bioactive [22]. An in vitro study demonstrated that at 37 °C, maximum fluoride release was observed from Equia Forte HT filling, regardless of pH conditions [23]. Modified forms of glass ionomers are available in the form of resin-modified glass ionomer cements (RMGICs) [24], zirconia-reinforced glass ionomers [25], nano-filled modified GICs [26], bioactive glasses [27], and glass carbomers [24].

During the setting process, resin composite materials may undergo shrinkage, which causes difficulties in effectively sealing against the tooth surface, potentially leading to the infiltration of bacteria [28]. This phenomenon, known as microleakage, is frequently manifested as marginal staining, postoperative sensitivity, and the development of secondary caries around the restoration site [29]. Applying an elastic shrinking material layer combined with bulk fill composite reduces the stress magnitude in dentin and enamel to replace dental tissues in Class I and II posterior cavities [30]. On the other hand, less microleakage was reported from Equia Forte in Class II restorations than with GC G-aenial Posterior in an in vitro study [31].

The current minimally invasive treatment approach involves removing infected dentin but preserving affected tissue that is partially demineralized [32]. The dentin remineralization process involves a complex mechanism of mineral gain and its interaction with the collagen matrix [33]. This biomimetic remineralization process represents an approach based on creating nanocrystals that are small enough to fit into the gap zones between adjacent collagen molecules and establish a hierarchical order in the mineralized collagen [34]. Modified and unmodified GICs have the potential to remineralize dentin at different depths [35].

Modified formulations of GICs can also improve marginal adaptation and reduce microleakage. Based on this hypothesis, the present systematic review performs a qualitative synthesis of the available in vitro evidence on the microleakage of commercially available glass ionomer cements (GICs); resin-modified glass ionomer cements (RMGICs); and modified glass ionomer cements with nano-filled, zirconia, or bioactive glasses.

2. Materials and Methods

The present systematic review followed the established Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement standards [36]. The PRISMA 2020 checklist of items is presented in Supplementary Table S1. The protocol for the systematic review was previously registered in the Prospective Registry of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the number CRD42023415453.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

According to the PECOS strategy [37], P: human extracted primary or permanent teeth, E: newly modified GICs, C: conventional GICs, O: microleakage or dental leakage, and S: in vitro or laboratory studies. Laboratory studies comparing the microleakage of conventional and newly modified commercially available glass ionomer materials used as dental restorative materials were eligible for inclusion. Animal and in vivo studies were excluded. Studies that assessed materials other than glass ionomers, added experimental materials to commercial GICs, or did not include a comparison between the traditional and at least one of the newly modified GICs were also excluded.

2.2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive electronic literature search was performed in Medline (via PubMed), Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus) to identify relevant articles published up to March 2023 without year and language limitations. Search strategies were structured with keywords based on each section of the PECOS question, separated by the Boolean operator “OR”; then, all sections were combined with the Boolean operator “AND”, as shown in Table 1. The last search was performed on 29 June 2023.

Table 1.

Search strategy.

2.3. Study Selection Process

Study records were imported into a reference manager software (Mendeley 1.19.8; Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), and duplicate records were discarded. Subsequently, the titles and abstracts of the resulting records were screened based on the previously established eligibility criteria. Eligible articles were then read in full text, and the eligibility criteria were applied again to determine whether the article was appropriate for inclusion in the qualitative synthesis. Additionally, the references and citations of the selected articles were manually reviewed to check for potentially eligible studies. All databases had alerts set up to retrieve recently published articles. The search strategy, study selection process, data extraction, and quality assessment (risk of bias assessment) were performed by two independent investigators (A.A. and M.M.). In case of doubt, a third investigator was consulted (J.L.S.).

2.4. Data Extraction

The following data were extracted from the selected articles: information about the authors, year of publication, glass ionomer materials used, sample characteristics (sample size, primary or permanent teeth, number of groups, and cavity classification), materials or specific techniques used, main outcome, and additional outcome measures.

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

The QUIN risk of bias tool for the assessment of in vitro studies conducted in dentistry was used [38]. This tool consists of 12 criteria that must be rated and given a score, as follows: adequately specified = 2, inadequately specified = 1, not specified = 0, and not applicable = exclude criteria from the calculation. The scores obtained were used to categorize an in vitro study as having a high, medium, or low risk of bias (>70% = low risk of bias, 50% to 70% = medium risk of bias, and <50% = high risk of bias). Final score = (total score × 100)/(2 × number of applicable criteria).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

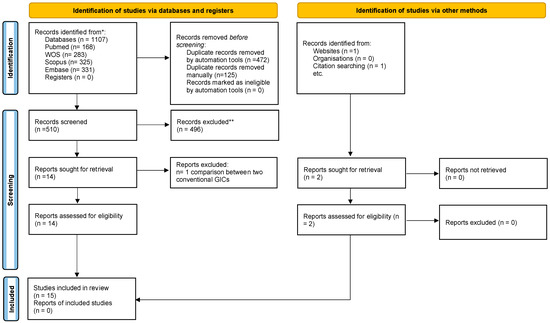

The search yielded a total of 1107 studies. Of these, 472 duplicate records were excluded by the reference manager software. A further 621 studies were excluded after title and abstract screening because they did not meet the eligibility criteria. The remaining 14 studies were selected for full-text review, which concluded with the exclusion of 1 study because it compared only two conventional GICs. Then, 1 study was added from citation research and 1 study from a Google Scholar search. Finally, 15 articles were included in this study for qualitative synthesis. The PRISMA 2020 statement flow diagram summarizing the selection process is shown in Figure 1 [36].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the study selection process. Based on the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [36]. * Records identified from each database. ** Records were excluded by a human and automation tools.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 2a,b.

Table 2.

(a) General outcomes in primary teeth. (b) General outcomes in permanent teeth.

All the included studies were in vitro studies published between 1993 and 2021. Of them, 1 study was conducted in Turkey [44], 1 in the USA [52], 1 in Egypt [27], 1 in Iraq [39], 1 in Indonesia [43], 2 in Belgium [48,49], 3 in Brazil [42,50,51] and 5 in India [40,41,45,46,47]. The sample size varied from 15 to 200 teeth; a total of 1159 teeth were evaluated. The number of assessed samples in each subgroup ranged from 5 to 30 cavities. In all studies, Black‘s cavity classification was reported [53]. The prepared cavities were classified as Class V except in two studies, where Class I was also used [45,46], and in one study, where the authors performed restorations of bacterial artificial root caries [50]. The selected teeth varied, with 5 studies on extracted primary teeth [39,40,41,42,43] and 10 studies on extracted permanent teeth [27,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Sound teeth were selected in most studies except one study on primary teeth [41] and one on permanent teeth [46], where caries teeth were selected.

Conventional GIC restorative materials used were Fuji II [40,47,48,52], Fuji IX [39,41,43,45,46,48], Equia Fil [27,44], Riva Self Cure [44], Ketac Fil [52], Ketac Fil Plus [49,50], Ketac Molar Easymix [42], and Ionofil Molar [49]. RMGICs used were Fuji II LC [27,39,40,41,43,45,47,48,51,52], Fuji VIII [48], Vitremer [50,51], and Photac Fil [49,52]. Other materials used were GICs reinforced with nano-zirconia fillers (Zirconomer Improved) [44], nano-filled carbonized glass (glass carbomer: Glass Fill) [44], bioactive ionic resin (Activa Bioactive Restorative) (27), highly reactive glass (hybrid GIC: Equia Forte) (41), and nano-filled RMGIC (Ketac N100) [42,43,45,46,47]. Other materials evaluated in the selected studies were Vitremer finishing gloss, Fuji Coat LC, G-Goat Plus, Ketac Primer, Icon, and Fuji Varnish II. The manufacturers and compositions of the mentioned materials are shown in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 3.

Commercially available conventional GICs evaluated in the included studies.

Table 4.

Commercially available RMGICs evaluated in the included studies.

Table 5.

Other commercially available dental materials evaluated in the included studies.

Various methods are used to evaluate the microleakage of GIC restorative materials. These include using the following dyes: 2% methylene blue [27,39,43,48,49,50], 0.5% methylene blue [42], 2% basic fuchsin [41,52], 0.5% basic fuchsin [44,46], rhodamine B [47,51], and acridine dye [45]. The studies used various methods to assess microleakage; in some, a score number between 0–4 [39,42,43,44,45], 0–3 [46,47,50,52], and 1–4 [27] was assigned; in others, quantitative assessment of dye penetration in millimeters was expressed as a percentage of the total length of the restorative interface in three studies [48,49,51]. SEM was employed in three studies for morphological analysis of cavities prepared by Er:YAG laser irradiation [48,49,50]. Additionally, SEM was utilized in one study to evaluate marginal gap formation and analyze the adhesion mechanism [52].

3.3. Results of Individual Studies

The studies showed conflicting results when comparing conventional GICs with RMGICs with regards to microleakage. Although no statistically significant differences were found in numerous studies [27,40,43,46,51], the results of most studies showed that RMGICs exhibited less leakage than conventional GICs [39,41,43,48,49,50,52]. Only two studies showed that conventional GICs had lower microleakage scores than RMGICs [43,51]. The included studies agreed that the most significant leakage was observed at the gingival margin compared to the occlusal margin [47,48,49,52], which was also significantly higher on dentin/cementum than on enamel margins [27,44].

In primary teeth, RMGIC (Fuji II LC and Ketac N100) showed less microleakage than conventional GIC (Fuji II, Fuji IX, and Ketac Molar Easymix) [39,40,41]. However, it is noteworthy that in one study [43], conventional Fuji IX exhibited slightly better results than Fuji II LC and Ketac N100, although the findings were not statistically significant. Also, one study on hybrid GIC (Equia Forte with Equia Coat) showed a significant reduction in microleakage compared to Fuji II LC and Fuji IX [39].

In permanent teeth, two studies showed that Ketac N100 exhibited less leakage, performed better than conventional GICs and RMGICs, and was more consistent in Class I and Class V cavities [45,47]. However, in one study, non-significant results were obtained compared to conventional GIC Fuji IX in Class I cavities [46]. Likewise, non-statistically significant differences were observed when comparing Activa Bioactive Restorative (RMIGC) to conventional GIC Equia Fil and RMGIC Fuji II LC with coating material G-Coat Plus [27]. Only one study comparing Zirconomer Improved GIC, conventional GIC, and glass carbomer showed that Zirconomer Improved and conventional GIC exhibited better results than glass carbomer [44].

Different methods for caries removal, like chemomechanical agents, air abrasion, and Er:YAG lasers, were also assessed in the included studies. The results of one study demonstrated no significant difference in microleakage between conventional GIC and Ketac N100 following conventional and chemomechanical caries removal methods [46]. Er:YAG laser irradiation was evaluated in three studies. In one study, after root caries removal, lower microleakage was observed in cavities prepared with a laser when combined with RMGIC restorative materials [50]. Two studies on Class V cavities restored with conventional GICs and RMGICs following conventional bur preparation and Er:YAG laser irradiation found that RMGICs showed less microleakage than GICs, regardless of the preparation method [48,49]. One study on cavities prepared with aluminum oxide air abrasion observed that conventional GIC and RMGIC used as restorative materials had similar behavior [51].

3.4. Quality Assessment (Risk of Bias)

The final scores among the included studies ranged from 50% to 70%, indicating a medium risk of bias. All the authors clearly stated the aims; provided a detailed explanation of the methodology, method of measurement of outcomes, and statistical analysis; and adequately presented the results. The sampling size calculation, the sampling technique, the criteria of outcome assessor details, and blinding needed to be adequately specified in most studies, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

QUIN tool risk of bias results.

4. Discussion

The use of GICs in posterior teeth has traditionally been limited by their physical properties [6]. The new GIC restorative materials have improved some of their mechanical properties without reducing their ion release [54]. This improvement could make them suitable in certain clinical situations, such as the restoration of primary teeth [55], cervical restorations [56], and teeth affected by molar incisor hypomineralization [57], among others. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis stated that high-viscosity GICs are comparable to composite resins for posterior restorations at least for 3 years, especially in patients at high risk of caries [58].

4.1. Study Methodology

Standardized and updated guidelines must be followed when performing in vitro studies [59]. Variations in the sample preparation methods could alter the results obtained. For example, bovine and swine substrates allow higher marginal leakage than human substrates [60]. Therefore, to maintain consistency in the findings, animal teeth studies were excluded from this study to reduce methodological heterogeneity. The use of human substrates was considered more relevant to the study’s objectives, and this decision contributes to the consistency of the results. Furthermore, primary teeth differ from permanent ones because they have thinner enamel, dentin, and longer pulp horns [40]. Therefore, the qualitative results were synthesized into two parts, primary and permanent teeth, to analyze the difference in the results.

Determining the appropriate sample size is crucial for achieving scientifically and statistically valid outcomes [61]. It is worth noting that among the studies reviewed, there was a lack of reporting or incomplete reporting of sample size calculations, and only two reported calculating the necessary sample size for the teeth used [40,41]. Additionally, two studies with small sample sizes produced different results from other included studies and demonstrated no statistical differences in their outcomes [43,51]. However, inadequate sample sizes can compromise the ability to detect differences between groups, leading to potentially falsely adverse outcomes and an elevated risk of a type II error [62].

The results of microleakage studies can be affected by cavity design. Notably, the U-shaped Class V cavity demonstrated superior performance in minimizing microleakage compared to the V-shaped design [63], a finding not mentioned in the studies.

Penetration may also be affected by the chosen dye material, the dye material’s concentration and diffusion coefficient, the dentin’s thickness, and the dentin’s available surface area for diffusion [63]. For example, rhodamine B dye has a molecular size smaller than the diameter of a dentinal tubule. It presents greater diffusion on human dentin than methylene blue, resulting in a higher leakage score [47]. The tested teeth were immersed in dye material for 24 h in all selected studies except for one study, in which the sample was immersed in 2% methylene blue dye for 4 h [43].

Thermocycling is a widely used method in laboratory dental studies to simulate temperature changes in the oral environment. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) recommends thermal cycling between 5 and 55 °C as an accelerated aging test [64]. Accordingly, most authors chose cycling temperatures between 5 and 55 °C except in one study by Madyarani et al. [43], where no thermocycling was applied. Concerning the methods used to detect microleakage, the authors opted for semi-quantitative assessment by different scores and quantitative assessment as a percentage in millimeters, allowing for precise measurements of the extent of leakage. The microleakage assessment using stereomicroscope methods featured high intra- and inter-examiner reproducibility levels [64]. However, a few studies referenced the level of inter-examiner agreement [39,40,42,45,48], indicating almost perfect inter-examiner reliability.

4.2. Study Results

The decrease in microleakage observed in RMGIC compared to conventional GIC could be attributed to differences in their setting reactions. In conventional GIC, if it encounters intraoral fluid during the initial setting, the matrix-forming ions (Ca and Al) may be washed out, resulting in improper matrix formation with inferior mechanical properties and increased microleakage. In contrast, RMGIC undergoes two setting processes: acid–base reaction and photopolymerization. In this process, hydroxyl ethyl methacrylate partially replaces water. The structure of RMGIC includes a matrix of metal polyacrylate salts and a polymer matrix. Consequently, RMGICs are generally considered less affected by moisture, exhibiting reduced microleakage compared to conventional GICs [41].

However, Hallet and Garcia-Godoy [52] also concluded that Fuji II LC performed worse than Fuji II at the enamel margin but was comparable at the dentin cementum margin. However, in the same study, Photac Fil showed a significantly more reliable seal than Ketac Fil at both the occlusal and gingival margins. The authors proposed that this could be attributed to the encapsulation of ESPE materials (Photac Fil and Ketac Fil). Meanwhile, the Fuji II LC and Fuji II were not capsulated, and individual hand proportions and mixing can affect the results.

Nano-filled RMGIC (Ketac N100) is a new RMGIC that was introduced in 2007. Two studies [45,47] performed on permanent teeth provided valuable insights on the performance of Ketac N100 compared to conventional GICs and other RMGICs. However, the study by Diwanji et al. [45] observed that there was no significant difference between the Fuji LC II and KN100 in Class I restoration. In contrast, a significant difference was obtained in Class V restorations. These results are consistent with those obtained by Gupta et al. [47], who found that Ketac N100 showed less leakage than conventional GIC and RMGIC at gingival margins. This could be due to smaller particle sizes providing better material flow and better adaptation to the tooth interface; also, the higher filler loading in the nano-filled type may result in lower polymerization shrinkage and a lower coefficient of thermal expansion, thus improving long-term bonding to the tooth structure. Additionally, the incremental layer technique used to place Ketac N100 may have further improved adaptation, leading to Ketac N100 showing less leakage and better performance than conventional GICs and other RMGICs.

The manufacturer and some authors refer to Activa Bioactive Restorative as a bio-active composite [65,66,67], but others consider it an RMGIC [27,68]. The components of Activa Bioactive Restorative are a proprietary bioactive ionic resin, a proprietary rubberized resin, and a bioactive glass ionomer; therefore, it was included in our research. We found only one study [27] that compared it with the GIC Equia Fil and the RMGIC Fuji II LC and demonstrated that they exhibited the same marginal adaptation and microleakage.

Carbomer Glass Fil is a new material that consists of nanosized hydroxyapatite–fluorapatite particles in powder form. Only one study evaluating permanent teeth [44] found higher microleakage and crack lines filled with dye in the glass carbomer. Despite the advantages of glass carbomer material, there is a need for improvements, particularly in its sealing capacity, for it to be considered a reliable restorative material.

Zirconomer Improved, a new restorative glass ionomer material (also called white amalgam because it combines the strength of amalgam with the biocompatibility and fluoride release of GICs), was evaluated in one study, and it was observed that they offer better leakage resistance than glass carbomer, conventional GICs, and RMGICs and might be considered as a reliable posterior restorative material, especially for patients with high caries activity [44].

Equia Forte is a glass hybrid restorative system that combines the benefits of GIC and composite resin. It is designed for anterior and posterior restorations, offering ease of use and esthetic results. The material comprises two components: a glass hybrid restorative and a nano-filled coating [69]. Alwan and Al Waheb’s study [39] on primary teeth revealed that Equia Forte with nano-coating (Equia Coat) demonstrated lower microleakage than both conventional GICs and RMGICs. Nevertheless, the limited available literature on Equia Forte, carbomer Glass Fil, and Activa Bioactive Restorative makes comparing the results to others difficult.

4.3. Factors Influencing Microleakage

Coating agents have a role in the prevention of microleakage; G-Coat Plus was studied in some studies with primary [39,40,41] and permanent teeth [27]. Alwan and Al-Waheb [39], in their study, concluded that conventional GIC (Fuji IX) with nano-coating (G-Coat Plus) has microleakage values equal to RMGIC (Fuji II LC) without coating. These outcomes are consistent with the results of the study conducted by Arthilakshmi et al. [41], who found that conventional GIC and RMGIC without G-Coat Plus coating showed more microleakage when compared to conventional GIC and RMGIC with G-Coat Plus. These findings were also confirmed in the study by Deshpande et al. [40]. Thus, using nano-coating with all types of GICs is preferred to minimize microleakage.

The different preparation techniques in the cavity may be another factor influencing the microleakage score results. In studies using laser cavity preparation [48,49,50], the researchers found that RMGICs performed better than conventional GICs in conditioned cavities treated with Er:YAG laser. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was applied to visualize the effect of the conditioner on the lasered tooth structure. Photographs demonstrated that the edges of the cavities obtained by Er:YAG laser irradiation were irregular, wrinkled, and free of a smear layer. Based on the authors’ opinions, this irregularity in cavity outlines and crater-like character free of the smear layer can improve the adhesion mechanism of GICs as it is favorable for micromechanical retention. Furthermore, conditioning is recommended to obtain a smoother surface with partial occlusion of dentinal tubules, which may improve contact between the GIC and the tooth. Pavuluri et al. also described that the chemomechanical removal of caries with Cariosolv in Class I cavities in young primary teeth did not affect the microleakage results in the GIC materials Fuji IX and Ketac N100. Furthermore, Cariosolv helps preserve dental tissue, although the clinical time is longer than when high-speed excavation is used [46].

There is weak evidence about the margin-sealing ability of GICs subjected to erosive challenges, and only one study [42] evaluated the behavior of GICs after subjecting them to Coca-Cola and orange juice. The results showed that they have a negative effect on the marginal sealing in both conventional and RMGIC materials. However, in vitro tests performed with composite materials have demonstrated that other variables can have a significant influence on long-term durability, such as depth of cure [70], curing type [71], and interface contamination [72]. Therefore, future studies on the influence of these factors on GICs are needed to expand our knowledge of these materials.

The results of many studies indicate that the gingival margins show more leakage than the occlusal margins. This behavior could be attributed to the fact that adhesion to enamel is stronger than dentin due to differences in morphologic, histologic, and compositional characteristics between the two because dentin has high organic and water content, low surface energy, and the presence of a smear layer [27,44,48,49].

In short, there are many factors that can affect the microfiltration of the materials, derived from the characteristics of the substrate, the conditioning of the fabrics, and the characteristics and handling of the material itself.

4.4. Limitations and Future Perspectives

The inherent laboratory nature of the included studies can serve as a limitation. In vitro studies do not replicate chewing load conditions or the thermal changes that occur orally. Likewise, setting conditions at a clinical level are not as controllable as in a laboratory and may affect microleakage. Due to the heterogeneity of the included studies, a meta-analysis could not be performed. Diverse materials were tested under different situations (different study groups, methodologies in manipulating the sample, primary or permanent, Class I and Class V, microleakage assessment method, and additional outcome measures). In addition, regarding newly modified GICs, only one study was included in the review for each assessed formulation, hindering the comparison of the obtained results. Therefore, in vitro studies and clinical trials are necessary to complete the information regarding their properties and clonal applications.

Another limitation could be the sample size of the studies included in the review, given that an adequate sample size calculation was presented in only two studies. Studies could also be influenced by reporting bias, as shown by the unfulfilled items in the quality assessment. At a review level, studies not included in the databases used could have been left out of the quality assessment.

The findings of the present systematic review represent the available evidence on the microleakage of various types of GICs in primary and permanent human teeth and may serve for future studies. Future investigations should use standardized laboratory procedures to evaluate the microleakage of newly modified GICs as restorative materials for primary and permanent human teeth in order to confirm the obtained results.

5. Conclusions

Based on the results of the in vitro studies included in the present review, Ketac N100, Equia Forte, and Zirconomer appear to exhibit less microleakage than conventional GICs and RMGICs. The use of nano-coating materials can significantly reduce microleakage in all glass ionomers. Further investigations using standardized procedures are needed to confirm the obtained results.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app14051729/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., C.L., and M.M.; methodology, A.A.; software, C.L. and S.F.; validation, J.L.S., M.M., and J.G.; formal analysis, C.L.; investigation, A.A.; resources, M.M.; data curation, C.L. and S.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, J.L.S. and M.M.; visualization, J.G. and S.F.; supervision, C.L. and S.F.; project administration, M.M.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Towler, M.R.; Bushby, A.J.; Billington, R.W.; Hill, R.G. A preliminary comparison of the mechanical properties of chemically cured and ultrasonically cured glass ionomer cements, using nano-indentation techniques. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 1401–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.L. Advances in glass-ionomer cements. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2006, 14, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duinen, R.N.; Davidson, C.L.; De Gee, A.J.; Feilzer, A.J. In situ transformation of glass-ionomer into an enamel-like material. Am. J. Dent. 2004, 17, 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, D.S.; Buciumeanu, M.; Martinelli, A.E.; Nascimento, R.M.; Henriques, B.; Silva, F.S.; Souza, J.C.M. Mechanical strength and wear of dental glass-ionomer and resin composites affected by porosity and chemical composition. J. Bio- Tribo-Corros. 2015, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes-Silva, R.; Cabral, R.N.; Pascotto, R.C.; Borges, A.F.S.; Martins, C.C.; Navarro, M.F.L.; Sidhu, S.K.; Leal, S.C. Mechanical and optical properties of conventional restorative glass-ionomer cements—A systematic review. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2019, 27, e2018357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, J.H.; Croll, T.P. Glass ionomer restorative cement systems: An update. Pediatr. Dent. 2015, 37, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, J.W.; Sidhu, S.K.; Czarnecka, B. Enhancing the Mechanical Properties of Glass-Ionomer Dental Cements: A Review. Materials 2020, 13, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beriat, N.C.; Nalbant, D. Water Absorption and HEMA Release of Resin-Modified Glass-Ionomers. Eur. J. Dent. 2009, 3, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Simmons, J.J. Silver-alloy powder and glass ionomer cement. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1990, 120, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohbauer, U.; Walker, J.; Nikolaenko, S.; Werner, J.; Clare, A.; Petschelt, A.; Griel, P. Reactive fibre reinforced glass ionomer cements. Biomaterials 2003, 17, 2901–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, A.H.; Schmitt, W.S.; Fleming, G.J.P. Modification of titanium dioxide particles to reinforce glass-ionomer restoratives. Dent. Mater 2014, 30, e159–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademolhosseini, M.R.; Barounian, M.H.; Eskandari, A.; Aminzare, M.; Zahedi, A.M.; Ghahremani, D. Development of new Al2O3/TiO2 reinforced glass-ionomer cements (GICs) nanocomposites. J. Basic Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 2, 7526–7529. [Google Scholar]

- Cibim, D.D.; Saito, M.T.; Giovani, P.A.; Borges, A.F.S.; Pecorari, V.G.A.; Gomes, O.P.; Lisboa-Filho, P.N.; Niciti-Junior, F.H.; Puppin-Rontani, R.M.; Kantovitz, K.R. Novel nanotechnology of TiO2 improves physical-chemical and biological properties of glass ionomer cement. Int. J. Biomater. 2017, 2017, 7123919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshaverinia, A.; Ansari, S.; Moshaverinia, M.; Roohpour, N.; Darr, J.; Rehman, A. Effects of incorporation of hydroxyapatite and fluorapatite nanobioceramics into conventional glass-ionomer cements (GIC). Acta Biomater. 2008, 4, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yli-Urpo, H.; Lassila, L.V.J.; Narhi, T.; Vallittu, P.K. Compressive strength and surface characterisation of glass-ionomer cements modified by particles of bioactive glass. Dent. Mater. 2005, 21, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunay, A.; Celenk, S.; Adiguzel, O.; Cangul, S.; Ozcan, N.; Eroglu Cakmakoglu, E. Comparison of Antibacterial Activity, Cytotoxicity, and Fluoride Release of Glass Ionomer Restorative Dental Cements in Dentistry. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2023, 29, e939065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzins, D.W.; Abey, S.; Costache, M.C.; Wilkie, C.A.; Roberts, H.W. Resin-modified Glass-ionomer Setting Reaction Competition. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, A.; Kharaziha, M.; Khoroushi, M. Dentin extracellular matrix loaded bioactive glass/GelMA support rapid bone mineralization for potential pulp regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 234, 123771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.W.; Czarnecka, B.; Limanowska-Shaw, H. The long-term interaction of dental cements with lactic acid solutions. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 1999, 10, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.E.; Arita, K.; Nishino, M. Toughness, bonding and fluoride-release properties of hydroxyapatite-added glass ionomer cement. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 3787–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijken, J.W.V.; Pallesen, U.; Benetti, A. A randomized controlled evaluation of posterior resin restorations of an altered resin modified glass-ionomer cement with claimed bioactivity. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, A.M.H.R.; Sidhu, S.K.; Nicholson, J.W. Fluoride release and uptake in enhanced bioactivity glass ionomer cement (“glass carbomerTM”) compared with conventional and resin-modified glass ionomer cements. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2019, 27, e20180230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lauro, A.; Di Duca, F.; Montuori, P.; Dal Piva, A.M.O.; Tribst, J.P.M.; Borges, A.L.S.; Ausiello, P. Fluoride and Calcium Release from Alkasite and Glass Ionomer Restorative Dental Materials: In Vitro Study. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, S.K.; Nicholson, J.W. A Review of Glass-Ionomer Cements for Clinical Dentistry. J. Funct. Biomater. 2016, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albeshti, R.; Shahid, S. Evaluation of Microleakage in Zirconomer (R): A Zirconia Reinforced Glass Ionomer Cement. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2018, 52, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharafeddin, F.; Feizi, N. Evaluation of the effect of adding micro-hydroxyapatite and nano-hydroxyapatite on the microleakage of conventional and resin-modified Glass-ionomer Cl V restorations. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2017, 9, e242–e248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebaya, M.M.; Ali, A.I.; Mahmoud, S.H. Evaluation of Marginal Adaptation and Microleakage of Three Glass Ionomer-Based Class V Restorations: In Vitro Study. Eur. J. Dent. 2019, 13, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figundio, N.; Lopes, P.; Tedesco, T.K.; Fernandes, J.C.H.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Mello-Moura, A.C.V. Deep Carious Lesions Management with Stepwise, Selective, or Non-Selective Removal in Permanent Dentition: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, F.A.; Andrade, M.F.; Pinelli, C.; Rastelli, A.; Victorino, K.R.; Loffredo, L.D. Accuracy of digital images in the detection of marginal microleakage: An in vitro study. J. Adhes. Dent. 2012, 14, 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Ausiello, P.; de Oliveira Dal Piva, A.M.; Souto Borges, A.L.; Lanzotti, A.; Zamparini, F.; Epifania, E.; Mendes Tribst, J.P. Effect of Shrinking and No Shrinking Dentine and Enamel Replacing Materials in Posterior Restoration: A 3D-FEA Study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, M.; Saleem Agwan, M.A.; Ghani, B.; Khatri, M.; Bopache, P.; Aziz, M.S. Evaluation of Class II Restoration Microleakage with Various Restorative Materials: A Comparative In vitro Study. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13 (Suppl. S2), S1210–S1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschberg, C.S.; Galicia, J.C.; Ruparel, N.B. AAE Position Statement on Vital Pulp Therapy. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 1340–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Smales, R.J.; Yip, H.K. Demineralisation and remineralisation of dentine caries, and the role of glass-ionomer cements. Int. Dent. J. 2000, 50, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Hao, Y.; Zhen, L.; Liu, H.; Shao, M.; Xu, X.; Liang, K.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, H.; Li, J.; et al. Biomineralization of dentin. J. Struct. Biol. 2019, 207, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghilotti, J.; Fernández, I.; Sanz, J.L.; Melo, M.; Llena, C. Remineralization Potential of Three Restorative Glass Ionomer Cements: An In Vitro Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, P.; Brunnhuber, K.; Chalkidou, K.; Chalmers, I.; Clarke, M.; Fenton, M.; Forbes, C.; Glanville, J.; Hicks, N.J.; Moody, J.; et al. How to formulate research recommendations. BMJ 2006, 333, 804–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheth, V.H.; Shah, N.P.; Jain, R.; Bhanushali, N.; Bhatnagar, V. Development and validation of a risk-of-bias tool for assessing in vitro studies conducted in dentistry: The QUIN. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, S.Q.; Al-Waheb, A.M. Effect of nano-coating on microleakage of different capsulated glass ionomer restoration in primary teeth: An in vitro study. Indian J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 2021, 15, 2674–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A.; Macwan, C.; Dhillon, S.; Wadhwa, M.; Joshi, N.; Shah, Y. Sealing Ability of Three Different Surface Coating Materials on Conventional and Resin Modified Glass Ion-omer Restoration in Primary Anterior Teeth: An In vitro Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2021, 15, ZC17–ZC22. [Google Scholar]

- Vishnurekha, C.; Annamalai, S.; Baghkomeh, P.N.; Sharmin, D.D. Effect of protective coating on microleakage of conventional glass ionomer cement and resin-modified glass ionomer cement in primary molars: An in vitro study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2018, 29, 744–748. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt Dissenha, R.M.; Lara, J.S.; Shitsuka, C.; Raggio, D.P.; Bonecker, M.; Pires Correa, F.N.; Imparato, J.C.P.; Salete, M.; Corrêa, N.P. Assessment of Glass Ionomer Cements (GIC) Restorations after Acidic Erosive Challenges: An in vitro Study. Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clínica Integr. 2016, 16, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Madyarani, D.; Nuraini, P.; Irmawati, I. Microleakage of conventional, resin-modified, and nano-ionomer glass ionomer cement as primary teeth filling material. Dent. J. Maj. Kedokt. Gigi 2014, 47, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meral, E.; Baseren, N.M. Shear bond strength and microleakage of novel glass-ionomer cements: An In vitro Study. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2019, 22, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diwanji, A.; Dhar, V.; Arora, R.; Madhusudan, A.; Rathore, A.S. Comparative evaluation of microleakage of three restorative glass ionomer cements: An in vitro study. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2014, 5, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavuluri, C.; Nuvvula, S.; Kamatham, R.L.; Nirmala, S. Comparative Evaluation of Microleakage in Conventional and RMGIC Restorations following Conventional and Chemome-chanical Caries Removal: An in vitro Study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2014, 7, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, J.; Saraswathi, V.; Ballal, N.; Shashirashmi, A.; Gupta, S. Comparative evaluation of microleakage in Class V cavities using various glass ionomer cements: An in vitro study. J. Interdiscip. Dent. 2012, 2, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmé, K.I.; Deman, P.J.; De Bruyne, M.A.; De Moor, R.J. Microleakage of Four Different Restorative Glass Ionomer Formulations in Class V Cavities: Er: YAG Laser versus Conventional Preparation. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2008, 26, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delmé, K.I.M.; Deman, P.J.; De Bruyne, M.A.A.; Nammour, S.; De Moor, R.J.G. Microleakage of glass ionomer formulations after erbium: Yttrium-aluminium-garnet laser preparation. Lasers Med. Sci. 2010, 25, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mello, A.M.; Mayer, M.P.; Mello, F.A.; Matos, A.B.; Marques, M.M. Effects of Er: YAG laser on the sealing of glass ionomer cement restorations of bacterial artificial root caries. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2006, 24, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corona, S.A.M.; Borsatto, M.C.; de Sá Rocha, R.A.S.; Palma-Dibb, R.G. Microleakage on Class V glass ionomer restorations after cavity preparation with aluminum oxide air abrasion. Braz. Dent. J. 2005, 16, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hallett, K.B.; Garcia-Godoy, F. Microleakage of resin-modified glass ionomer cement restorations: An in vitro study. Dent. Mater. 1993, 9, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shruthi, M.; Srinivasan, D.; Eagappan, S.; Louis, J.; Natarajan, D.; Meena, S. A Review of Dental Caries Classification Systems. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2022, 15, 4819–4824. [Google Scholar]

- Vilela, H.S.; Resende, M.C.A.; Trinca, R.B.; Scaramucci, T.; Sakae, L.O.; Braga, R.R. Glass ionomer cement with calcium-releasing particles: Effect on dentin mineral content and mechanical properties. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hübel, S.; Mejàre, I. Conventional versus resin-modified glass-ionomer cement for Class II restorations in primary molars. A 3-year clinical study. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2023, 13, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koc Vural, U.; Kerimova, L.; Kiremitci, A. Clinical comparison of a micro-hybride resin-based composite and resin modified glass ionomer in the treatment of cervical caries lesions: 36-month, split-mouth, randomized clinical trial. Odontology 2021, 109, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragelli, C.M.; Souza, J.F.; Jeremias, F.; Cordeiro Rde, C.; Santos-Pinto, L. Molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH): Conservative treatment management to restore affected teeth. Braz. Oral Res. 2015, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cribari, L.; Madeira, L.; Roeder, R.B.R.; Macedo, R.M.; Wambier, L.M.; Porto, T.S.; Gonzaga, C.C.; Kaizer, M.R. High-viscosity glass-ionomer cement or composite resin for restorations in posterior permanent teeth? A systematic review and meta-analyses. J. Dent. 2023, 137, 104629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlHabdan, A.A. Review of Microleakage Evaluation Tools. J. Int. Oral Health 2017, 9, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuabara, A.; Santos, A.J.S.D.; Aguiar, F.H.B.; Lovadino, J.R. Evaluation of microleakage in human, bovine and swine enamels. Braz. Oral Res. 2004, 18, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdar, C.C.; Cihan, M.; Yücel, D.; Serdar, M.A. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: Simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem. Medica 2021, 31, 10502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskin, A.; D’Hoore, W.; Gonthier, S.; Degrange, M.; Déjou, J. Reliability of in vitro microleakage tests: A literature review. J. Adhes. Dent. 2001, 3, 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/TS 11405:2015; Dental Materials—Testing of Adhesion to Tooth Structure. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- Alvarenga, F.A.S.; Pinelli, C.; Loffredo, L.C.M. Reliability of marginal microleakage assessment by visual and digital methods. Eur. J. Dent. 2015, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lardani, L.; Derchi, G.; Marchio, V.; Carli, E. One-Year Clinical Performance of ActivaTM Bioactive-Restorative Composite in Primary Molars. Child 2022, 9, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaireh, A.I.; Al-Jundi, S.H.; Alshraideh, H.A. In vitro evaluation of microleakage in primary teeth restored with three adhesive materials: ACTIVATM, composite resin, and res-in-modified glass ionomer. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 20, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhadra, D.; Shah, N.C.; Rao, A.S.; Dedania, M.S.; Bajpai, N. A 1-year comparative evaluation of clinical performance of nanohybrid composite with ActivaTM bioactive composite in Class II carious lesion: A randomized control study. J. Conserv. Dent. 2019, 22, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Benetti, A.R.; Michou, S.; Larsen, L.; Peutzfeldt, A.; Pallesen, U.; van Dijken, J.W.V. Adhesion and marginal adaptation of a claimed bioactive, restorative material. Biomater. Investig. Dent. 2019, 6, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brkanović, S.; Ivanišević, A.; Miletić, I.; Mezdić, D.; Jukić Krmek, S. Effect of Nano-Filled Protective Coating and Different pH Enviroment on Wear Resistance of New Glass Hybrid Restorative Material. Materials 2021, 14, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, M.; Gallo, S.; Poggio, C.; Ricaldone, V.; Arciola, C.R.; Scribante, A. New Resin-Based Bulk-Fill Composites: In vitro Evaluation of Micro-Hardness and Depth of Cure as Infection Risk Indexes. Materials 2020, 13, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, A.C.M.; Borges, A.B.; Kukulka, E.C.; Moecke, S.E.; Scotti, N.; Comba, A.; Pucci, C.R.; Torres, C.R.G. Optical Property Stability of Light-Cured versus Precured CAD-CAM Composites. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 2011864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciafesta, V.; Sfondrini, M.F.; Scribante, A.; De Angelis, M.; Klersy, C. Effects of blood contamination on the shear bond strengths of conventional and hydrophilic primers. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2004, 126, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).