Abstract

Objective: Esthetic dentistry is an important factor in increasing patients’ quality of life. This study aimed to investigate the impact of laser use on bleaching procedures for natural teeth and dental restorative materials. Methods: In January 2024, an electronic search was conducted using PubMed, Web of Science (WoS), and Scopus databases with the keywords (tooth) AND (laser) AND (bleaching), following PRISMA guidelines and the PICO framework. The initial search yielded 852 articles, of which 441 were screened. After applying inclusion criteria, 376 articles were excluded as they did not focus on the use of lasers in bleaching natural teeth and restorative materials. Consequently, 40 articles were included in the final review. Results: Of the 40 qualified publications, 29 utilized a diode laser, of which 10 authors concluded that it increases the whitening effect comparing classical methods. Three of included publications investigated the whitening of dental materials, while another three focused on endodontically treated teeth. Whitening procedures on ceramics effectively removed discoloration, but the resulting color did not significantly differ from the initial shade. Conversely, composite materials not only failed to bleach but also exhibited altered physical properties, thereby increasing their susceptibility to further discoloration. The KTP laser demonstrated promising outcomes on specific stains. The Er,Cr:YSGG and Er:YAG lasers also showed beneficial effects, although there were variations in their efficacy and required activation times. Conclusions: The findings partially indicate that laser-assisted bleaching improves the whitening of natural teeth. Further research on the effect of laser bleaching on the physical parameters of restorative materials is necessary.

1. Introduction

Tooth bleaching has become one of the most popular esthetic procedures performed in dental offices in recent years [1]. This surge in popularity is driven by patients’ increasing desire not only for dental health but also for enhanced esthetics. White teeth are widely regarded as indicators of youth, social status, and health-consciousness [2]. Hydrogen peroxide (HP) is the most commonly used bleaching agent, at concentrations typically around 35% [3]. The mechanism of tooth bleaching involves a chemical oxidation reaction in which chromogenic compounds are oxidized and converted to colorless forms [4,5,6]. Despite its efficacy, conventional in-office bleaching with HP often necessitates multiple treatment sessions to achieve the desired results. This can lead to tooth sensitivity, which is a common side effect [7]. Furthermore, the outcomes of bleaching treatments are frequently unsatisfactory when it comes to dental restorations, such as composite resins and porcelain crowns. These materials often do not respond uniformly to bleaching agents, leading to discrepancies in color and overall esthetic results. Recent advancements have prompted the evaluation of laser-assisted bleaching as an adjunct to traditional methods. Laser technology has shown promise in enhancing the efficacy of bleaching agents by accelerating the chemical reactions involved. Various studies have explored the use of lasers to improve the speed and effectiveness of the whitening process. Additionally, lasers may help in achieving more uniform results across both natural teeth and restorative materials.

When planning the teeth whitening process for patients, it is crucial to recognize that the aforementioned bleaching agents will interact not only with the natural tissues of the tooth but also with various restorative materials commonly used in modern dentistry [8]. One of the most frequently used restorative materials is composite resin, which is a popular choice due to its esthetic properties and ease of application. It is important to assess how exposure to bleaching agents will influence the physical and chemical properties of these materials. Recent research has highlighted the impact of bleaching agents on the color and stability of composite resins, as achieving a brighter shade is a primary goal of whitening treatments. While hydrogen peroxide (HP) and carbamide peroxide (CP) are effective at whitening natural tooth tissues, their interaction with resin composites can be problematic. Studies have shown that these materials often do not respond to bleaching agents in the same manner as natural tooth tissues [8]. For instance, while natural teeth can exhibit significant color change, resin composites may experience limited or uneven color modification, which can lead to esthetic discrepancies between natural teeth and restorations. Resin composites, due to their organic matrix, are particularly susceptible to adverse effects from tooth whitening treatments. The oxidative hydrolysis induced by peroxides at the C-C bonds of the polymer matrix can lead to the degradation of the composite resin, causing discoloration, a loss of gloss, and structural weakening [4]. The integrity of the resin matrix can be compromised, leading to potential issues such as increased porosity and reduced bonding strength. Additionally, studies have found that repeated exposure to bleaching agents can exacerbate these issues, causing the progressive deterioration of the composite material over time. Some research also indicates that certain types of composite resins are more resistant to bleaching effects than others, suggesting that material composition and formulation play a significant role in the response to whitening treatments [8]. To address these concerns, it is essential to carefully select restorative materials that are compatible with whitening agents and to consider alternative or supplementary whitening strategies that minimize the impact on dental restorations.

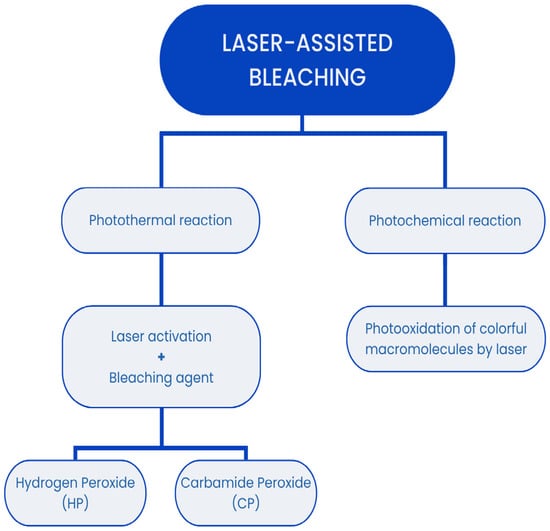

The mechanisms behind laser-assisted tooth bleaching can be divided into two basic methods: photothermal and photochemical reactions (Figure 1). In the photothermal method, the laser acts as an activator and enhancer for the bleaching agent, typically hydrogen peroxide (HP) or carbamide peroxide (CP). The laser’s energy increases the rate of the chemical reactions involved in the bleaching process by heating the bleaching agent, which enhances its effectiveness. This method can lead to the more efficient breakdown of chromogenic compounds and accelerated whitening [2,9]. In the photochemical method, laser light is absorbed by the bleached surfaces and directly induces the photooxidation of the chromogenic macromolecules. The energy from the laser light interacts with the pigment molecules, causing a chemical reaction that breaks down the color-producing compounds, resulting in a lighter shade of the tooth [10,11]. This method leverages the laser’s ability to generate reactive oxygen species that interact with and degrade chromogenic molecules. Each laser used in these procedures is characterized by several critical parameters: the wavelength of the emitted light (measured in nanometers, nm), the power density of the beam (measured in watts per square centimeter, W/cm2), and the type of energy emitted—whether pulsed or continuous [12,13]. Additional features include the pulse rate and pulse duration, which influence the overall effectiveness and safety of the procedure [2,9,10,11]. The choice of laser parameters can significantly affect the outcome of the bleaching treatment, as different wavelengths and power settings can result in varying levels of effectiveness and risk. The energy emitted by a laser must be meticulously controlled during in vivo tooth bleaching, as part of the beam is converted into heat. Excessive heat can increase the temperature of the tooth structure and the surrounding soft tissues, potentially leading to pulp damage, thermal injury, or discomfort [14,15]. Effective cooling mechanisms and the precise calibration of laser settings are essential to mitigate these risks and ensure the safety of the procedure [16,17].

Figure 1.

The mechanisms behind laser-assisted tooth bleaching.

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the role of laser-assisted teeth bleaching, considering its effectiveness on both dental restoration materials and natural teeth. After analyzing articles related to the use of laser irradiation to support the bleaching process, it was determined that a systematic review of this subject is justified. Currently, no systematic review on this topic has been published. Undertaking such a literature review could inspire researchers to conduct further studies, potentially yielding significant advantages for both dental practitioners and patients in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focused Question

The systematic review followed the PICO framework [18] as follows: In cases of dental bleaching (population) what would be the effect of laser use (investigated condition) on the color change (outcome) of teeth and different dental restorative materials compared to other bleaching methods (comparison condition)?

2.2. Protocol

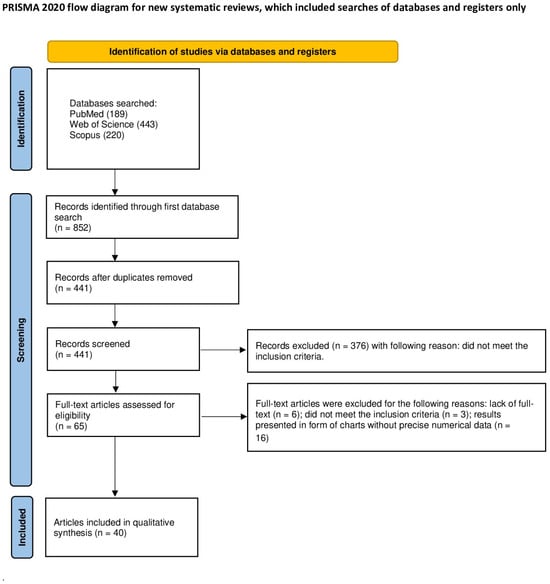

The selection process for articles included in the systematic review was carefully outlined following the PRISMA flow diagram [19] (see Figure 2). The systematic review was registered on the Open Science Framework under the following link: https://osf.io/dvnh8 (accessed on 3 August 2024).

Figure 2.

The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

The researchers agreed to include only the articles that met the following criteria [18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]:

- Laser conditioning studies;

- Studies conducted on natural teeth or restorative materials;

- Color evaluation studies;

- In vitro studies;

- In vivo studies;

- Studies with a control group;

- Studies in English;

- Full-text articles.

The exclusion criteria the reviewers agreed upon were as follows [18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]:

- No laser treatment;

- No color evaluation;

- Studies without a control group;

- Non-English papers

- Systematic review articles;

- Review articles;

- No full-text accessible;

- Duplicated publications.

No restrictions were applied with regard to the year of publication.

2.4. Information Sources, Search Strategy, and Study Selection

In January 2024, the PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS) databases were searched to find articles meeting the specified inclusion criteria. To find articles focusing on laser bleaching’s effect on natural teeth or restorative materials, the search was narrowed to titles and abstracts using a combination of key words: tooth AND laser AND bleaching. All searches conformed to the predefined eligibility criteria, and only articles with accessible full-text versions were taken into consideration.

2.5. Data Collection Process and Data Items

The articles that followed the inclusion criteria were carefully extracted by seven independent reviewers (J.K, B.P, M.Z.-D., W.Ś, J.K, S.K, W.D). The following data were used: first author, year of publication, study design, article title, laser application, and its bleaching effect. These essential data were entered into a standardized Excel file.

2.6. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

During the initial phase of study selection, each reviewer independently examined the titles and abstracts to mitigate potential reviewer bias. The Cohen’s k test served as a tool to assess the extent of the agreement among reviewers. Any discrepancies regarding the inclusion or exclusion of an article in the review were addressed through discussion among the authors [29].

2.7. Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (J.M, M.D) conducted independent screenings of the included studies to assess the quality of each selected study. To evaluate the study’s design, implementation, and analysis, the following criteria were used: a minimum group size of 10 subjects, the presence of a control group, a clear description of the performed bleaching method, the characteristics of the exposure time, an assessment of the bleaching effect, a description of the effect of bleaching on tooth tissue or surfaces, and the number of bleaching methods used. The studies were scored on a scale of 0 to 10 points, with a higher score indicating higher study quality. The risk of bias was assessed as follows: 0–4 points denoted a high risk, 5–7 points denoted a moderate risk, and 8–10 points indicated a low risk. Any discrepancies in scoring were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached [18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

An initial database search of PubMed, Scopus, and WoS yielded 852 articles potentially relevant to the review. After removing duplicates, 441 articles were screened. After the initial screening of titles and abstracts, 376 articles that did not concern laser-assisted teeth or restorative material bleaching were excluded. It was not possible to access the full text of six articles. Of the remaining 59 articles, 3 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria and 16 were excluded in which the research results were presented in the form of charts, without the possibility of reading precise numerical data. Ultimately, a total of 40 articles were included in the qualitative synthesis of this review. The considerable heterogeneity among the included studies prevents the possibility of conducting a meta-analysis.

3.2. General Characteristics of the Included Studies

The selected studies assessed the change in the color of teeth and dental materials as a result of carbamide peroxide (CP) and hydrogen peroxide (HP) whitening activated by laser light. To assess color, researchers most often used a spectrophotometer and its parameters using the CIE L*a*b* system. It is a color space created by the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) for the purpose of the standardization and repeatability of measurements. The L* axis contains shades of gray, numerically ranging from 0 to 100, where 0 is black and 100 is white. The a* axis is referred to as “red–green”. At its negative end there are shades of red, and at its positive end there are shades of green. The b* axis, called “blue–yellow”, is created analogously. The blue color is described by negative numbers, while the positive numbers are reserved for the yellow color. The tested color is described as a point in three-dimensional space. It is defined by three numerical values that change linearly. If two colors are written in the CIE L*a*b* color space, you can calculate the number ΔE (the number of the difference between the colors), which is the distance between these colors in the three-dimensional CIE L*a*b color space, using the formula ΔE* = (ΔL*2 + Δa*2 + Δb*2)1/2 [30,31]. Some authors also calculated the Whitening Index for Dentistry (WID) using the formula WID = 0.511 L* − 2.324 a* − 1.100 b* [1,3]. Another system used is Vita Classical Shade Guide, where we deal with 16 shades arranged from the lightest B1 (1) to the darkest D4 (16). To calculate the difference in color change, the authors used numerical values corresponding to individual shades and called them Shade Guide Units (SGU) [32].

3.2.1. Diode Laser-Assisted Bleaching

Authors most often chose to use a diode laser for bleaching in their studies. This procedure appeared in as many as 29 papers [2,3,4,5,7,8,9,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. In 11 of them, the in vitro whitening involved human teeth [34,35,37,40,42,45,47,50,51,52,55]. It was observed that when using 35% HP, the best whitening effects were achieved with a laser power of 1.5 W, regardless of whether the wavelength was 810, 940, or 980 nm [37,55,56]. For higher and lower power values, the results were not as significant [37,55,56]. When using CP as a bleaching agent, both Saluja et al. [35] and Nam et al. [46] proved that the effect was proportional to the CP concentration and exposure time. This relationship did not occur in the case of HP and bovine teeth [38,48]. The studies also included two publications in which the whitening agent was activated in the pulp chamber with a diode laser, and, in both cases, a more favorable effect was obtained at a shorter wavelength [33,43]. It was much more difficult to find relationships in the studies conducted in patients [2,5,7,41,44,49,54,57,58]. In these cases, very different wavelengths, concentrations of preparations, and methods for assessing the effects were used. For example, Mondelli et al. [54] used an 810 nm diode laser to activate materials containing 35% HP, 38% HP, and 15% CP. After exposing each material for 3 min, he concluded that they were equally effective [54]. However, effectiveness cannot be conclusively determined for whitening dental materials where the ΔE typically reaches a value less than 1, indicating that the color difference is not noticeable [8,36]. The exception is a study conducted by Mawlood AA and Hamasaeed NH [4], who whitened a composite restorative material (Filtek™, 3MESPE, Dental Product, St. Paul, MN, USA) with 40% HP activated by a 940 nm diode laser, achieving ΔE values of 5–10, which are comparable to those observed in enamel whitening [4]. Additionally, some publications included studies using hybrid light. Guedes et al. [3] reported that irradiation with an 808 nm diode laser combined with blue and violet LEDs increased whitening efficiency. In contrast, Costa et al. [9], who added a violet LED to an 810 nm diode laser, found that the effect was no different from using 35% HP without activation [9].

3.2.2. Gallium Aluminum Arsenate (AsGaAl) Laser-Assisted Bleaching

AsGaAl laser-assisted bleaching was conducted only by Vochikovski et al [1]. Its aim was to reduce post-treatment sensitivity, but the obtained result turned out to be statistically insignificant. The whitening effect was comparable to that without laser activation [1].

3.2.3. Neodymium/Yttrium–Aluminum–Garnet (Nd:YAG) Laser-Assisted Bleaching

The use of the Nd:YAG laser for whitening non-vital teeth has proven to be as effective as both a diode laser at 810 and 980 nm and the walking bleaching method [33]. In in vivo tooth whitening, the results were comparable to those achieved without activation. However, in vitro studies showed less tooth color change with Nd:YAG laser activation compared to halogen light [59,60]. Borse et al. [61] attempted to enhance the whitening effect by pre-treating the enamel with this laser before applying the whitening agent, but this approach did not yield the expected results [61].

3.2.4. Argon Laser-Assisted Bleaching

Lima et al. [62] performed bleaching using 35% HP and 37% CP and activation with various light sources, including an argon laser with a wavelength of 488 nm. The results showed that this laser produced the least color change of all the groups tested. Jones et al. [63] concluded that argon laser activation did not cause any color change, obtaining an average ΔE of 2.23 [63].

3.2.5. Potassium Titanyl Phosphate (KTP) Laser-Assisted Bleaching

There was a dissonance between researchers using the KTP laser. According to some studies, the effects are more visible compared to the diode laser, but the results of others indicate that there is no statistically significant difference between them [48,52]. Lagori et al. [53] point out the difference in action against specific discolorations. In their study comparing the effects of diode laser-assisted whitening and KTP, he showed that both lasers could remove coffee stains, while enamel stains caused by fruit and tea were only removed by using the KTP laser and not the diode laser [53].

3.2.6. Erbium/Yttrium–Aluminum–Garnet (Er:YAG) and Erbium, Chromium, Yttrium, Scandium, Gallium Garnet (Er,Cr:YSGG) Laser-Assisted Bleaching

Whitening with the assistance of an Er:YAG laser led to a change in the color of the enamel comparable to that achieved with a diode laser, but required twice the exposure time [55]. When applied to endodontically treated teeth, the Er:YAG laser provided a more favorable effect than the walking bleaching method, although this was only observed with the use of 20% HP [64]. Both Papadopoulos et al. [10] and Dionysopoulos et al. [55] prove, with their research, the effectiveness of Er,Cr:YSGG laser whitening. They both used 35% HP and the same laser parameters for this purpose. Papadopoulos additionally compared the power of 1.25 W and 2.5 W, while Dionysopoulos reduced the exposure time from 30 to 15 s. In each case, whitening was more effective than conventional methods. However, this does not work in the case of composite fillings. In this case, the obtained color did not differ from the initial one [8] (see Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of studies.

3.3. Main Study Outcomes

A diode laser was used in 29 publications, of which 10 concluded that it increases the whitening effect [5,34,38,40,42,43,48,52,53,55]. Of the four publications in which the Nd:YAG laser was used, only one showed its positive effect on whitening [59]. In two out of three tests conducted using the Er,Cr:YSGG laser, a greater color change was found compared to the conventional method [8,10,55]. None of the studies involving argon or AsGaAl lasers showed that they increased whitening efficiency [1,62,63]. At the same time, the authors of all articles describing whitening assisted with KTP or Er:YAG lasers concluded that they increased the whitening effect [48,52,53,55,64]. In 31 papers, a spectrophotometer was used to measure color, of which only 1 decided not to calculate the ΔE value [1,2,3,4,7,8,9,10,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,44,46,48,49,51,52,53,54,55,56,61,63,64,65]. As many as seven researchers decided to use the VITA shade guide as the only assessment of whitening effects [5,42,43,47,57,58,60]. The bleaching of ceramics typically results in the restoration of their original factory color, with no significant improvement beyond that [36]. Moreover, bleaching composite materials has generally yielded limited or no noticeable color improvement [4,8]. For whitening endodontically treated teeth, laser-assisted techniques have demonstrated superior efficacy compared to conventional methods, as shown in two studies [43,64]. Furthermore, lasers have been effective in whitening non-vital primary teeth, presenting a promising alternative to traditional approaches [51]. Among the whitening agents, 35% hydrogen peroxide (HP) was the most commonly used, featured in 17 of the 40 studies reviewed [1,2,7,10,37,40,45,51,52,54,55,59,60,61,63,65,66]. (See Table 2.)

Table 2.

Detailed characteristics table.

3.4. Quality Assessment

Among the articles included in the review, eleven [1,3,5,8,9,37,40,41,45,60,61] were rated as high-quality, achieving a score between 8 and 10 points out of 10. One study [34] was categorized as low-quality. Furthermore, twenty-eight studies [2,4,7,9,10,33,36,38,39,42,43,44,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,57,58,59,63,64,65] were identified as having a moderate risk of bias, scoring between 5 and 7 points (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Quality assessment of reviewed articles. The full titles of some of the columns in Table 3 are given here. Column 7: evaluation of the bleaching effect (spectrophotometry/visual assessment using VITA coloring). Column 8: description of the effect of bleaching on teeth or dental materials (0 pts—no data/1 pt—before or after bleaching procedure/2 pts—information before and after bleaching procedure). Column 9: the number of bleaching methods used (1 laser/1 solution concentration/1 wavelength—1 point; ≥2 lasers/solutions/wavelengths—2 points).

4. Discussion

In this systematic review, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy of various laser wavelengths in bleaching procedures used for both natural teeth and restorative materials in comparison to traditional methods. Our findings suggest that laser-assisted bleaching can enhance the whitening effect for both natural teeth and dental restorative materials. A diode laser, with wavelengths ranging from 808 nm to 980 nm, was the most frequently utilized laser in these studies. [2,3,4,5,7,8,9,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Ten studies employing a diode laser concluded that its use enhances the whitening effect [5,34,38,40,42,43,48,52,53,55]. Interestingly, it was observed that when using 35% hydrogen peroxide, the best whitening effects were achieved with a laser power of 1.5 W, regardless of whether the wavelength was 810 nm, 940 nm, or 980 nm [37,55,56]. For higher and lower power values, the results were not significant [37,55,56]. Three papers focused on the laser-assisted bleaching of restorative materials. However, the differing methodologies and various variables assessed in these studies create difficulties in comparing the results. The use of the Nd:YAG laser for whitening non-vital teeth has proven to be as effective as 810 nm and 980 nm diode lasers [33]. Moreover, the results of two studies by Papadopoulos et al. [10] and Dionysopoulos et al. [55] demonstrated the effectiveness of Er,Cr:YSGG laser whitening with the application of 35% hydrogen peroxide.

Among the included papers, there were significant differences regarding the rationale for using laser-assisted activation in whitening procedures. Guedes et al. [3] reported that irradiation with an 808 nm diode laser combined with blue and violet LEDs increased whitening efficiency. In contrast, Costa et al. [9], who added a violet LED to an 810 nm diode laser, found that the effect was no different from using 35% HP without activation [3,9]. Ahrari et al. [38], Fekrazad et al. [40], and Al Maliky et al. [5] agreed that diode lasers with wavelengths of 810 and 940 nm not only shortened the whitening time but also reduced post-treatment sensitivity. Ergin et al. [55] achieved a better whitening effect by activating 35% HP with an Er:YAG laser than with a 940 nm diode laser, but the difference in the ΔE was less than 1, which means that it was not visually noticeable. However, according to Ergin et al. [55], it is still worth using the Er:YAG laser if the teeth require restoration after whitening, because they observed a better adhesion of materials to the whitened surfaces. However, the studies of Kiryk et al. [67] show that the Er:YAG laser leads to damage of the enamel surface. Ozer et al. [64] used this laser for the intracoronal whitening of endodontically treated teeth. A better effect is visible here than in the walking bleaching technique using 20% HP. Bahuguna [68] wrote that heating 30% HP promotes the development of external cervical resorption; the question arises as to whether the use of 20% HP with an Er:YAG laser will result in a lower risk of this common complication.

Other lasers discussed in this review include argon, Nd:YAG, and KTP lasers. The analysis of the compiled results indicates that the argon laser produced the least effective outcomes. Despite using bleaching agents such as 35% HP and 37% CP and a laser wavelength of 488 nm, its effect was not significantly visible. This may indicate insufficient laser power, meaning that it does not contribute to permanent enamel discoloration [62]. Other lasers, such as AsGaAL, Nd:YAG, or KTP lasers, did not show a better effect than the diode laser [1,33,48,53,59,60,61]. However, it is worth noting that, according to some studies, the KTP laser performs better on tea or fruit stains compared to the diode laser. This may indicate its superiority over the diode laser, as the spectrum of discolorations it affects appears to be somewhat broader [53].

Another important aspect is the irradiation time of the bleached surface. Studies show that increasing the laser irradiation time increases the bleaching effect. This effect can be said to increase proportionally, and with a twofold increase in time the effect doubles [35]. We must remember that during bleaching, the use of a laser only activates the chemical agent, which is crucial to the whole process. When using CP as a bleaching agent, both Saluja et al. [35] and Nam et al. [46] proved that the effect was proportional to the CP’s concentration and exposure time. There is no such relationship with HP [38,48]. According to the studies of Mondelli et al. [54], when bleaching teeth in patients, the use of 15% CP gives the same result as using 35 or 38% HP. Much better results, presented as ΔE, were obtained using lasers with shorter wavelengths. Studies conducted by Shokouhinejad N. et al. [33] and Saeedi R. et al. [37] compared the bleaching effect of diode lasers with different wavelengths—810, 940, and 980 nm. Analyzing these two studies, one can conclude that the bleaching effect increases with the decrease in the wavelength of the assisting laser, presented in both studies as ΔE. The difference between the shortest and the longest wavelength is up to 7 units, which translates into a bleaching effect and enamel color change [37,56]. Similar conclusions can be drawn by considering other studies, where examples with shorter wavelengths produced better bleaching effects than those with longer wavelengths [41].

Some studies combined the use of diode lasers and LED light [3,9,39]. The results of these studies show that LED light can additionally enhance the effect of the bleaching on enamel. For the purpose of this review, we can compare the study conducted by Guedes et al. [3], which used additional LED light, with the study by Loiola et al. [69], which only used a diode laser with the same wavelength of 808 nm. Despite slight differences in laser parameters and the use of different bleaching agents, a significantly better bleaching effect can be observed for the diode laser combined with LED light, where the ΔE reaches up to 14 units [3]. Additionally, the use of LED light helps achieve a similar bleaching effect to that obtained at high concentrations even at low concentrations of the bleaching agent [9,38].

However, the other factors, apart from the tooth color itself, which should be taken into account and were not included in most of the studies are intriguing. When looking for the positive effects of lasers, it is worth paying attention to the aforementioned hypersensitivity caused by whitening. Browning et al.’s [70] study shows that as many as 77% of patients experience hypersensitivity within 2 weeks of teeth whitening, which indicates that this is a very important clinical aspect. Silva Casado et al. [71] and Kikly et al. [72] addressed this topic and both showed that laser activation does not reduce post-treatment hypersensitivity.

In the literature on whitening dental materials, authors have discussed different aspects of the materials, making it difficult to directly compare their findings. Mawlood and Hamasaeed [4] analyzed color stability and concluded that as a result of whitening, the physical parameters of the composites change, causing their surface to become rough and increasing their water sorption, which makes them more susceptible to discoloration. The authors made an intriguing observation that changes in composite parameters are influenced by the amount of filler within the material. The bleaching of composites was also performed by Karanasiou et al. [8], and they concluded that it did not affect the color of resin-based restorations. Conversely, Chitsaz et al. [36], studying ceramics, concluded that these materials are susceptible to discoloration from specific substances used in their experiments, such as coffee and orange juice. However, samples soaked in distilled water after bleaching did not show any change in color compared to their initial state, indicating that bleaching does not alter the inherent color of the ceramics.

The significant heterogeneity of the included studies does not allow for a meta-analysis. However, to obtain more accurate results and to be able to proceed to a meta-analysis, additional studies are needed that are homogeneous in terms of the laser types used and their parameters. There is no doubt that the number of publications describing the whitening of dental materials is so small that it is impossible to draw reliable conclusions for use in clinical practice. Nevertheless, considering the influence of laser light on the physical parameters of these materials, as demonstrated by Mawlood and Hamasaeed [4], this topic should be investigated in more detail in order to ensure the safety of whitening procedures for patients and to avoid complications harmful to oral health.

5. Conclusions

The reviewed studies partially demonstrate that laser-assisted bleaching significantly influences the color change seen in natural teeth. Among the various lasers evaluated, the diode laser showed the most consistent positive effects on bleaching outcomes, especially when used in combination with LED light, and lasers with shorter wavelengths generally provided better results. Certain lasers, such as the KTP laser, demonstrated promising outcomes on specific stains; others, like the argon laser, proved less effective. The Er,Cr:YSGG and Er:YAG lasers also showed beneficial effects, though with some variations in their efficacy and required activation times. Overall, laser-assisted bleaching enhances whitening results, but further research is crucial to refine the protocols used and achieve more consistent and dependable outcomes.

In summary:

- The diode laser demonstrated the most consistent positive effects on bleaching outcomes.

- The Er:YAG laser has a more beneficial effect on endodontically treated teeth, thanks to the possibility of using a lower HP concentration compared to the walking bleaching method.

- When assisting whitening with a diode laser, it is more beneficial to use a shorter wavelength.

- Laser-activated bleaching reduces post-treatment hypersensitivity.

- Laser bleaching may have an adverse effect on the physical parameters of restorative materials. This requires further in-depth study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K. (Jan Kiryk), J.M. and M.D.; methodology, J.K. (Jan Kiryk) and J.M.; software, J.K. (Jan Kiryk); validation, J.K. (Jan Kiryk) and J.M.; formal analysis, M.D.; investigation, W.Ś., J.K. (Jan Kiryk), J.K. (Julia Kensy), B.P., M.Z.-D., S.K. and W.D.; resources, J.M. and J.K. (Jan Kiryk); data curation, J.M. and M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, B.P., M.Z.-D., J.K. (Jan Kiryk), J.K. (Julia Kensy), S.K. and W.D. writing—review and editing, M.D. and J.M.; visualization, J.K. (Jan Kiryk); supervision, M.D. and J.M.; project administration, J.M. and M.D.; funding acquisition, J.M. and M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed by a subsidy from Wroclaw Medical University, number SUBZ.B180.24.058.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state that there are not any conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- Vochikovski, L.; Favoreto, M.W.; Rezende, M.; Terra, R.M.O.; Gumy, F.N.; Loguercio, A.D.; Reis, A. Use of Infrared Photobiomodulation with Low-Level Laser Therapy for Reduction of Bleaching-Induced Tooth Sensitivity after in-Office Bleaching: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2023, 38, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekce, A.U.; Yazici, A.R. Clinical Comparison of Diode Laser- and LED-Activated Tooth Bleaching: 9-Month Follow-Up. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 3237–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedes, R.d.A.; Carlos, N.R.; Turssi, C.P.; França, F.M.G.; Vieira-Junior, W.F.; Kantovitz, K.R.; Bronze-Uhle, E.S.; Lisboa-Filho, P.N.; Basting, R.T. Hybrid Light Applied with 37% Carbamide Peroxide Bleaching Agent with or without Titanium Dioxide Potentializes Color Change Effectiveness. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 44, 103762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mawlood, A.A.; Hamasaeed, N.H. The Impact of the Diode Laser 940 Nm Photoactivated Bleaching on Color Change of Different Composite Resin Restorations. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2023, 14, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maliky, M.A. Clinical Investigation of 940 Nm Diode Laser Power Bleaching: An in Vivo Study. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 10, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabi, S.; Assadian, H.; Nahavandi, A.M.; Nokhbatolfoghahaei, H. Comparison of Tooth Color Change after Bleaching with Conventional and Different Light-Activated Methods. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 9, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena-Serrano, A.P.; Garcia, E.; Luque-Martinez, I.; Grande, R.H.M.; Loguercio, A.D.; Reis, A. A Single-Blind Randomized Trial about the Effect of Hydrogen Peroxide Concentration on Light-Activated Bleaching. Oper. Dent. 2016, 41, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanasiou, C.; Dionysopoulos, D.; Naka, O.; Strakas, D.; Tolidis, K. Effects of Tooth Bleaching Protocols Assisted by Er,Cr:YSGG and Diode (980 Nm) Lasers on Color Change of Resin-Based Restoratives. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.L.d.S.G.; Besegato, J.F.; Kuga, M.C. Bleaching and Microstructural Effects of Low Concentration Hydrogen Peroxide Photoactivated with LED/Laser System on Bovine Enamel. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 35, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, A.; Dionysopoulos, D.; Strakas, D.; Koumpia, E.; Tolidis, K. Spectrophotometric Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Er,Cr:YSGG Laser-Assisted Intracoronal Tooth Bleaching Treatment Using Different Power Settings. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 34, 102272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moor, R.J.G.; Verheyen, J.; Diachuk, A.; Verheyen, P.; Meire, M.A.; De Coster, P.J.; Keulemans, F.; De Bruyne, M.; Walsh, L.J. Insight in the Chemistry of Laser-Activated Dental Bleaching. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, 650492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matys, J.; Dominiak, M.; Flieger, R. Energy and Power Density: A Key Factor in Lasers Studies. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, ZL01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Cronshaw, M.; Matys, J.; Brugnera, A.; Nammour, S. Full Operating Parameter Recording as an Essential Component of the Reproducibility of Laser-Tissue Interaction and Treatments. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 33, 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeb, J.G.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Weaver, C.; Matys, J.; Bencharit, S. Retrieval of Glass Fiber Post Using Er:YAG Laser and Conventional Endodontic Ultrasonic Method: An In Vitro Study. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 1024–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A.; García, J.A.; Costela, Á.; Gómez, C. Influence of the Light Source and Bleaching Gel on the Efficacy of the Tooth Whitening Process. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2011, 29, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matys, J.; Hadzik, J.; Dominiak, M. Schneiderian Membrane Perforation Rate and Increase in Bone Temperature during Maxillary Sinus Floor Elevation by Means of Er:YAG Laser—An Animal Study in Pigs. Implant. Dent. 2017, 26, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Bencharit, S.; Skrjanc, L.; Kanduti, D.; Matys, J.; Deeb, J.G. Utilization of Er:YAG Laser in Retrieving and Reusing of Lithium Disilicate and Zirconia Monolithic Crowns in Natural Teeth: An In Vitro Study. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lin, J.; Demner-Fushman, D. Evaluation of PICO as a Knowledge Representation for Clinical Questions. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2006, 2006, 359–363. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homa, K.; Zakrzewski, W.; Dobrzyński, W.; Piszko, P.J.; Piszko, A.; Matys, J.; Wiglusz, R.J.; Dobrzyński, M. Surface Functionalization of Titanium-Based Implants with a Nanohydroxyapatite Layer and Its Impact on Osteoblasts: A Systematic Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rygas, J.; Matys, J.; Wawrzyńska, M.; Szymonowicz, M.; Dobrzyński, M. The Use of Graphene Oxide in Orthodontics—A Systematic Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajewska, J.; Kowalski, J.; Matys, J.; Dobrzyński, M.; Wiglusz, R.J. The Use of Lactide Polymers in Bone Tissue Regeneration in Dentistry—A Systematic Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kensy, J.; Dobrzyński, M.; Wiench, R.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Matys, J. Fibroblasts Adhesion to Laser-Modified Titanium Surfaces—A Systematic Review. Materials 2021, 14, 7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matys, J.; Kensy, J.; Gedrange, T.; Zawiślak, I.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Dobrzyński, M. A Molecular Approach for Detecting Bacteria and Fungi in Healthcare Environment Aerosols: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struzik, N.; Wiśniewska, K.; Piszko, P.J.; Piszko, A.; Kiryk, J.; Matys, J.; Dobrzyński, M. SEM Studies Assessing the Efficacy of Laser Treatment for Primary Teeth: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, J.; Rygas, J.; Homa, K.; Dobrzyński, W.; Wiglusz, R.J.; Matys, J.; Dobrzyński, M. Antibacterial Activity of Endodontic Gutta-Percha—A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piszko, P.J.; Piszko, A.; Kiryk, J.; Lubojański, A.; Dobrzyński, W.; Wiglusz, R.J.; Matys, J.; Dobrzyński, M. The Influence of Fluoride Gels on the Physicochemical Properties of Tooth Tissues and Dental Materials—A Systematic Review. Gels 2024, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murias, I.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Murias, A.; Walicka-Cupryś, K.; Dominiak, M.; Deeb, J.G.; Matys, J. Efficacy of Various Laser Wavelengths in the Surgical Treatment of Ankyloglossia: A Systematic Review. Life 2022, 12, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.F.; Petrie, A. Method Agreement Analysis: A Review of Correct Methodology. Theriogenology 2010, 73, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sproull, R.C. Color Matching in Dentistry. Part I. The Three-Dimensional Nature of Color. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1973, 29, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cal, E.; Sonugelen, M.; Guneri, P.; Kesercioglu, A.; Kose, T. Application of a Digital Technique in Evaluating the Reliability of Shade Guides. J. Oral Rehabil. 2004, 31, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, S.J.; Trushkowsky, R.D.; Paravina, R.D. Dental Color Matching Instruments and Systems. Review of Clinical and Research Aspects. Proc. J. Dent. 2010, 38, e2–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokouhinejad, N.; Khoshkhounejad, M.; Hamidzadeh, F. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Laser-Assisted Bleaching of the Teeth Discolored Due to Regenerative Endodontic Treatment. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 3589609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, P.; Valli, K. Comparative Study of Effects of Home Bleach and Laser Bleach Using Digital Spectrophotometer: An In Vitro Study. J. Conserv. Dent. 2022, 25, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saluja, I.; Shetty, N.; Shenoy, R.; Pangal, S. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Diode Laser in Bleaching of the Tooth at Different Time Intervals Using Spectrophotometer: An In Vitro Study. J. Conserv. Dent. 2022, 25, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitsaz, F.; Ghodsi, S.; Harehdasht, S.A.; Goodarzi, B.; Zeighami, S. Evaluation of the Colour and Translucency Parameter of Conventional and Computer-Aided Design and Computer-Aided Manufacturing (CAD-CAM) Feldspathic Porcelains after Staining and Laser-Assisted Bleaching. J. Conserv. Dent. 2021, 24, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, R.; Omrani, L.R.; Abbasi, M.; Chiniforush, N.; Kargar, M. Effect of Three Wavelengths of Diode Laser on the Efficacy of Bleaching of Stained Teeth. Front. Dent. 2019, 16, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrari, F.; Akbari, M.; Mohammadpour, S.; Forghani, M. The Efficacy of Laser-Assisted in-Office Bleaching and Home Bleaching on Sound and Demineralized Enamel. Laser Ther. 2015, 24, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersezio, C.; Martín, J.; Angel, P.; Bottner, J.; Godoy, I.; Avalos, F.; Fernández, E. Teeth Whitening with 6% Hydrogen Peroxide and Its Impact on Quality of Life: 2 Years of Follow-Up. Odontology 2019, 107, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekrazad, R.; Alimazandarani, S.; Kalhori, K.A.M.; Assadian, H.; Mirmohammadi, S.M. Comparison of Laser and Power Bleaching Techniques in Tooth Color Change. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2017, 9, e511–e515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vildosola, P.; Vera, F.; Ramirez, J.; Rencoret, J.; Pretel, H.; Oliveira, O.B.; Tonetto, M.; Martin, J.; Fernandez, E. Comparison of Effectiveness and Sensitivity Using Two In-Office Bleaching Protocols for a 6% Hydrogen Peroxide Gel in a Randomized Clinical Trial. Oper. Dent. 2017, 42, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutani, N.; Venigalla, B.S.; Patil, J.P.; Singh, T.V.; Jyotsna, S.V.; Jain, A. Evaluation of Bleaching Efficacy of 37.5% Hydrogen Peroxide on Human Teeth Using Different Modes of Activations: An In Vitro Study. J. Conserv. Dent. 2016, 19, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Karadaghi, T.S.; Al-Saedi, A.A.; Al-Maliky, M.A.; Mahmood, A.S. The Effect of Bleaching Gel and (940 Nm and 980 Nm) Diode Lasers Photoactivation on Intrapulpal Temperature and Teeth Whitening Efficiency. Aust. Endod. J. 2016, 42, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrari, F.; Akbari, M.; Mohammadipour, H.S.; Fallahrastegar, A.; Sekandari, S. The Efficacy and Complications of Several Bleaching Techniques in Patients after Fixed Orthodontic Therapy. A Randomized Clinical Trial. Swiss Dent. J. 2020, 130, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameda, A.; Masuda, Y.M.; Toko, T.; Yamada, Y.; Kimura, Y.; Tamaki, Y.; Miyazaki, T. Effects of Tooth Coating Material and Finishing Agent on Bleached Enamel Surfaces by KTP Laser. Laser Ther. 2013, 22, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.H.; Lee, H.W.; Cho, S.H.; Lee, J.K.; Jeon, Y.C.; Kim, G.C. High-Efficiency Tooth Bleaching Using Nonthermal Atmospheric Pressure Plasma with Low Concentration of Hydrogen Peroxide. J. Appl. Oral. Sci. 2013, 21, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, P.; Schondelmaier, N.; Wolkewitz, M.; Altenburger, M.J.; Polydorou, O. Efficacy of Tooth Bleaching with and without Light Activation and Its Effect on the Pulp Temperature: An In Vitro Study. Odontology 2013, 101, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaini, C.; Lagori, G.; Merigo, E.; Meleti, M.; Manfredi, M.; Guidotti, R.; Serraj, A.; Vescovi, P. Analysis of Shade, Temperature and Hydrogen Peroxide Concentration during Dental Bleaching: In Vitro Study with the KTP and Diode Lasers. Lasers Med. Sci. 2013, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgan, S.; Cakir, F.Y.; Yazici, E. Different Light-Activated in-Office Bleaching Systems: A Clinical Evaluation. Lasers Med. Sci. 2010, 25, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, D.A.N.L.; Aguiar, F.H.B.; Liporoni, P.C.S.; Munin, E.; Ambrosano, G.M.B.; Lovadino, J.R. Influence of Chemical or Physical Catalysts on High Concentration Bleaching Agents. Eur. J. Esthet. Dent. 2011, 6, 454–466. [Google Scholar]

- Gontijo, I.T.; Navarro, R.S.; Ciamponi, A.L.; Miyakawa, W.; Zezell, D.M. Color and Surface Temperature Variation during Bleaching in Human Devitalized Primary Teeth: An In Vitro Study. J. Dent. Child. 2008, 75, 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Kinoshita, J.I.; Zhao, B.; Toko, T.; Kimura, Y.; Matsumoto, K. Effects of KTP Laser Irradiation, Diode Laser, and LED on Tooth Bleaching: A Comparative Study. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2007, 25, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagori, G.; Vescovi, P.; Merigo, E.; Meleti, M.; Fornaini, C. The Bleaching Efficiency of KTP and Diode 810 Nm Lasers on Teeth Stained with Different Substances: An In Vitro Study. Laser Ther. 2014, 23, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondelli, R.F.L.; de Azevedo, J.F.D.e.G.; Francisconi, A.C.; de Almeida, C.M.; Ishikiriama, S.K. Comparative Clinical Study of the Effectiveness of Different Dental Bleaching Methods—Two Year Follow-Up. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2012, 20, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergin, E.; Ruya Yazici, A.; Kalender, B.; Usumez, A.; Ertan, A.; Gorucu, J.; Sari, T. In Vitro Comparison of an Er:YAG Laser-Activated Bleaching System with Different Light-Activated Bleaching Systems for Color Change, Surface Roughness, and Enamel Bond Strength. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 1913–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.S.; Costa, C.A.S.; Soares, D.G.S.; Dos Santos, P.H.; Cintra, L.T.A.; Briso, A.L.F. Effect of Different Light Sources and Enamel Preconditioning on Color Change, H2O2 Penetration, and Cytotoxicity in Bleached Teeth. Oper. Dent. 2016, 41, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polydorou, O.; Wirsching, M.; Wokewitz, M.; Hahn, P. Three-Month Evaluation of Vital Tooth Bleaching Using Light Units—A Randomized Clinical Study. Oper. Dent. 2013, 38, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Quran, F.A.M.; Mansour, Y.; Al-Hyari, S.; Al Wahadni, A.; Mair, L. Efficacy and Persistence of Tooth Bleaching Using a Diode Laser with Three Different Treatment Regimens. Eur. J. Esthet. Dent. 2011, 6, 436–445. [Google Scholar]

- Strobl, A.; Gutknecht, N.; Franzen, R.; Hilgers, R.D.; Lampert, F.; Meister, J. Laser-Assisted in-Office Bleaching Using a Neodymium: Yttrium-Aluminum-Garnet Laser: An In Vivo Study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2010, 25, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcondes, M.; Paranhos, M.P.G.; Spohr, A.M.; Mota, E.G.; Da Silva, I.N.L.; Souto, A.A.; Burnett, L.H. The Influence of the Nd:YAG Laser Bleaching on Physical and Mechanical Properties of the Dental Enamel. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2009, 90B, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borse, V.S.; Sanjay Pandit, V.; Gaikwad, A.; Bajirao Jadhav, A.; Handa, A.; Bhamare, R. Effect of Neodymium-Doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet (Nd:YAG) Laser Enamel Pre-Treatment on the Whitening Efficacy of a Bleaching Agent. Cureus 2022, 14, e31325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, D.A.N.L.; Aguiar, F.H.B.; Liporoni, P.C.S.; Munin, E.; Ambrosano, G.M.B.; Lovadino, J.R. In Vitro Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Bleaching Agents Activated by Different Light Sources. J. Prosthodont. 2009, 18, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.H.; Diaz-Arnold, A.M.; Vargas, M.A.; Cobb, D.S. Colorimetric Assessment of Laser and Home Bleaching Techniques. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 1999, 11, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özer, S.Y.; Kaplslz, E. Comparison of Walking-Bleaching and Photon-Initiated Photoacoustic Streaming Techniques in Tooth Color Change of Artificially Colored Teeth. Photobiomodul Photomed. Laser Surg. 2021, 39, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionysopoulos, D.; Strakas, D.; Tolidis, K.; Tsitrou, E.; Koumpia, E.; Koliniotou-Koumpia, E. Spectrophotometric Analysis of the Effectiveness of a Novel In-Office Laser-Assisted Tooth Bleaching Method Using Er,Cr:YSGG Laser. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1811–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arce, M.B.; Lima, D.A.; Aguiar, F.H.; Ambrosano, G.M.; Munin, E.; Lovadino, J.R. Evaluation of Ultrasound and Light Sources as Bleaching Catalysts—An In Vitro Study. Eur. J. Esthet. Dent. 2012, 7, 176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kiryk, J.; Matys, J.; Nikodem, A.; Burzyńska, K.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Dominiak, M.; Dobrzyński, M. The Effect of Er:Yag Laser on a Shear Bond Strength Value of Orthodontic Brackets to Enamel—A Preliminary Study. Materials 2021, 14, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahuguna, N. Cervical Root Resorption and Non Vital Bleaching. Endodontology 2013, 25, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiola, A.B.A.; Souza-Gabriel, A.E.; Scatolin, R.S.; Corona, S.A.M. Impact of Hydrogen Peroxide Activated by Lighting-Emitting Diode/Laser System on Enamel Color and Microhardness: An In Situ Design. Contemp Clin Dent 2016, 7, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, W.D. Use of Shade Guides for Color Measurement in Tooth-Bleaching Studies. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2003, 15, S13–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Casado, B.G.; Pellizzer, E.P.; Maior, J.R.S.; Lemos, C.A.A.; do Egito Vasconcelos, B.C.; de Moraes, S.L.D. Laser Influence on Dental Sensitivity Compared to Other Light Sources Used during In-Office Dental Bleaching: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oper. Dent. 2020, 45, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikly, A.; Jaâfoura, S.; Sahtout, S. Vital Laser-Activated Teeth Bleaching and Postoperative Sensitivity: A Systematic Review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2019, 31, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).