Abstract

An English-Bengali machine translation (MT) application can convert an English text into a corresponding Bengali translation. To build a better model for this task, we can optimize English-Bengali MT. MT for languages with rich resources, like English-German, started decades ago. However, MT for languages lacking many parallel corpora remains challenging. In our study, we employed back-translation to improve the translation accuracy. With back-translation, we can have a pseudo-parallel corpus, and the generated (pseudo) corpus can be added to the original dataset to obtain an augmented dataset. However, the new data can be regarded as noisy data because they are generated by models that may not be trained very well or not evaluated well, like human translators. Since the original output of a translation model is a probability distribution of candidate words, to make the model more robust, different decoding methods are used, such as beam search, top-k random sampling and random sampling with temperature T, and others. Notably, top-k random sampling and random sampling with temperature T are more commonly used and more optimal decoding methods than the beam search. To this end, our study compares LSTM (Long-Short Term Memory, as a baseline) and Transformer. Our results show that Transformer (BLEU: in validation, in test) outperforms LSTM ( in validation, in test) by a large margin in the English-Bengali translation task. (Evaluating LSTM and Transformer without any augmented data is our baseline study.) We also incorporate two decoding methods, top-k random sampling and random sampling with temperature T, for back-translation that help improve the translation accuracy of the model. The results show that data generated by back-translation without top-k or temperature sampling (“no strategy”) help improve the accuracy (BLEU , + on validation, , + on test). Specifically, back-translation with top-k sampling is less effective (, BLEU , + on validation, , + on test), while sampling with a proper value of T, makes the model achieve a higher score (, BLEU , + on validation, , + on test). This implies that in English-Bengali MT, we can augment the training set through back-translation using random sampling with a proper temperature T.

MSC:

68T01; 68T07; 68T10; 68T20; 68T27; 68T30; 68T35; 68T45; 68T50

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

In machine translation (MT), we input an ordered sequence of words in a source language (i.e., a sentence) to the model and expect that the model outputs a sentence in a target language, which has the same meaning as the input [1]. Most recent research on MT falls under neural machine translation (NMT), which employs various neural networks, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), transformer models, and so on. A typical NMT model consists of two main components: an encoder that transcribes the input sentence into a hidden representation and a decoder that generates the target sentence according to the hidden representation [2]. In particular, RNN-based models (basic RNN, LSTM, GRU, and other variants) were used in earlier days of NMT evolution [3,4]. However, with RNN-based models, translation accuracy degrades when the sequence length and out-of-vocabulary or unknown words increase. Another issue is that the information that the decoder receives from the encoder is the last hidden state of the encoder. It especially contains the numerical summary of the input sequence. With this, it can handle the translation of short sentences but not the translation of long sentences since it gets a numerical summary of itself. As human beings, we may also have trouble translating a long sentence. To address these issues, an RNN-based model with an attention-based mechanism was introduced [5,6,7]. In this mechanism, the encoder encodes the input sentence into a sequence of vectors (for each token) rather than encoding it into a fixed-length vector and passes the vectors to the decoder while addressing the issue of forgetting long sequences. It persists for all the sequences. As we know, LSTM or GRU are not computationally efficient for large datasets, also cannot help ensure parallel processing of tasks, and are attached to numerous issues. As such, Vaswani et al. [8] proposed a new model, the Transformer that renounces recurrence and rather entirely relies on self-attention technique while computing the global dependencies between source (input) and target (output). In addition, Transformer helps us ensure better parallel processing of tasks and helps achieve better translation accuracy [8,9,10]. Now, transformer models have become the mainstream architecture for NMT. A detailed demonstration of all these three architectures is presented in the Related Work section (Section 2.1).

We observe that in NMT, the size of the training data affects the translation quality. Models for translation between language pairs with abundant parallel corpora are easier to train and perform well in general usage. However, the languages that lack parallel corpora (known as low-resource languages) make it challenging to train a high-quality translation model on limited data. English-Bengali is an example of this case. As stated earlier, NMT is a data-driven task, so applying NMT to low-resource parallel corpora (English-Bengali in this study) is a challenge. We also observe that very few research works have been conducted in handling the translation in this domain. We briefly review a set of approaches herein. Mumin et al. [11] uses the NMT architecture, which has an RNN-based encoder-decoder with the attention mechanism. However, the translation accuracy and quality are very low (BLEU: 16.26, BilinguaL Evaluation Understudy (BLEU) is the most commonly used evaluation metric in MT evaluation [12]. The significance of it is presented in the later part of this section), and it is very hard to understand the gist. Kunchukuttan et al. [13] contributed significantly. The authors worked to build a corpus for the top 10 Indian languages, including Hindi, Bengali, Tamil, Telegu, and others; however, the accuracy of bilingual lexicon induction for English-Bengali is not good. We observe that in building English-Bengali corpus and English-Bengali NMT architecture, the most prominent research works come from BUET CSE NLP Group, Bangladesh (BUET CSE NLP Group, Bangladesh https://csebuetnlp.github.io/ accessed on 1 August 2024) [14,15,16,17]. In their research, they compile a Bengali-English parallel corpus, captioned as BanglaNMT, comprised of sentence pairs [18]. Also, in their research, they build a model called BanglaT5 [16] (a Transformer model based on the standard Transformer introduced by Vaswani et al. [8]. The base variant of the BanglaT5 model is comprised of 12 layers, 12 attention heads, 768 hidden-layer size, 2048 feed-forward size, trained on a v3-8 TPU instance on Google Cloud Platform), which evaluates six NLP tasks such as machine translation, question answering, text summarization, dialogue generation, cross-lingual summarization, and headline generation [16]. In the context of our study of English-Bengali Translation, we observe that the translation accuracy of BanglaT5 is not high (BLEU: 17.4). Notably, we can incorporate different augmentation approaches with the NMT models for the enhancement of machine translation tasks [2]. In this paper, we work on this aspect; however, our baseline Transformer model is not as large as the BanglaT5 (the detailed configuration is presented in the Experiments Section (Section 4.3)). Due to the lack of powerful computing resources and to reduce the carbon footprint while reducing the environmental impacts, we designed a very basic Transformer model integrated with two decoding strategies, as discussed in this paper. Especially toward building a viable NMT Engine for low-resource parallel corpora a set of augmentation approaches, such as back-translation [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], pivot language technique [30,31,32], leveraging multi-modal data [33], and others can be used while leveraging monolingual data. We observe that the notable approaches work well for the language pairs mentioned in the literature (a detailed demonstration is presented in the Related Work section (Section 2.2). However, we need to evaluate the effectiveness of the approaches for other low-resource language pairs.

1.2. Challenges and Contributions

In this paper, in building our viable English-Bengali NMT engine, we employ back-translation while leveraging monolingual data. Back-translation is one of the state-of-the-art strategies used in NMT for addressing low-resource languages and monolingual corpora [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Notably, the architectures of translation and back-translation models are similar, simply altering/reversing the source and target corpora for the encoder and decoder. In back-translation, instead of extracting the test set from the datasets used for training and validation, it is recommended to use a part of the dataset for testing or directly use a monolingual target corpus. That improves the model generalization. Especially, the translated text and the monolingual target data in the last stage can be used as a pseudo-parallel corpus and can be appended with the original dataset, and the model can be trained with this augmented dataset, which can help train the model better. Therefore, with back-translation, we can obtain an augmented dataset. However, the new data can be regarded as data with noise because they are generated by models that may not yet be trained very well or not evaluated as well as human translators (assuming that human translators generate perfect translations). Since the original output of a translation model is a probability distribution of candidate words, to make the model more robust, different decoding methods are used, such as beam search [34], top-k random sampling [35] and random sampling with temperature T [36], and others. Notably, top-k random sampling and random sampling with temperature T are the most commonly used and optimal decoding methods than the beam search [35,36]. Beam search was usually used in the early days of NMT evolution. Therefore, we can append the pseudo-parallel corpus with the original dataset obtained from back-translation with the decoding strategies. The experiment results (Section 4.4) show that back-translation with decoding strategies improves translation accuracy respectfully. Thus, the model can be trained with the augmented dataset, which can help enhance the generalization ability [37,38,39]. Especially, the process can be repeated further with the monolingual datasets from different sources.

In the experimental study of this paper, we start our analysis by comparing two (2) architectures: LSTM and Transformer. Thereafter, we employ back-translation with the two decoding methods as stated earlier: top-k random sampling [35] and random sampling with temperature T [36]. The top-k random sampling samples from the top k predictions. For example, if , in this case, the model simply picks up the 3 words or tokens with the highest probabilities and sets the probabilities of the rests to (−10,000 in practice). Alongside, random sampling with temperature T is a factor to modify the randomness of candidate words. Notably, if we set in top-k random sampling or if we set in random sampling with temperature T, then the probability distribution is not modified, i.e., the model samples from all tokens in its vocabulary with their original probabilities. (It can be called “no strategy”). It is not resource-intensive and optimal as it samples from all the tokens. In this paper, in our study, we explore the optimal values for k and T respectfully. For more details, including the definitions of k and T, we refer to Section 3 and Section 4.

Especially in our study, we evaluate the machine translation task using an automatic evaluation method called BilinguaL Evaluation Understudy (BLEU) [12]. BLEU is the most commonly used evaluation metric in machine translation evaluation [2]. Given a sentence predicted by the model and the reference translation, BLEU measures their similarity. Notably, the BLEU score is based on precision (ranges from 0 to 1) while analyzing the similarity between the candidate translation and any translation reference(s). Especially, the BLEU score is multiplied by 100 to make it a score in a 0 to 100 interval by convention [12]. Now, a question arises in our mind: what is a good BLEU score? Usually, a BLEU score higher than 30 is considered a good score. For the interpretation of BLEU scores, a rough guideline is provided by Google (Interpretation of BLEU Scores https://cloud.google.com/translate/automl/docs/evaluate accessed on 1 August 2024). If the score lies between 30–40, it means that “Understandable to good translations”. Similarly, 40–50 interprets “High-quality translations”, 50–60 interprets “Very high quality, adequate, and fluent translations”, and >60 interprets “Quality often better than human”.

So far, we have presented our study thoroughly. Now, for the sake of clarity, we summarize it. As such, the key aspects are as follows:

- The first aspect is a comparison between LSTM and Transformer on English-Bengali machine translation. We find that the Transformer architecture has better accuracy even with a small training dataset (BLEU: LSTM on validation, on test; Transformer on validation, on test). Specifically, this is our baseline study to evaluate whether the Transformer can perform better in our study of English-Bengali machine translation. In our further study, we use the baseline Transformer as the basis and employ back-translation with decoding strategies as mentioned earlier and in the following aspect.

- The second aspect is performing back-translation, reversing source and target languages. However, what is the novelty of doing this? Since we have a low-resource English-Bengali corpus, the model will not have a very high level of generalization ability. In this case, if we perform inference with the monolingual Bengali datasets as the training set, the Translation accuracy or quality will not be very good. Further, we would like to add that even if we train the model with a large dataset like BanglaNMT [18], the generalization ability of the model reaches a certain level. Therefore, in this case, the back-translation does not help much in augmenting machine translation. To this end, our goal is to augment the English-Bengali corpus with back-translation while incorporating decoding strategies that improve translation accuracy and quality. Since NMT is a data-driven task, we can repeat this process. Especially, we can employ this process for domain-specific translation tasks since achieving high accuracy in domain-specific machine translation is very challenging due to the lack of authentic parallel corpora, and understanding the languages by the model is a very complex task even though we may have high-resource parallel corpora. In sum, we use back-translation to boost our base Transformer model incorporated with the two decoding strategies, such as top-k random sampling and random sampling with temperature T. We observe that decoding by top- random sampling helps improve the accuracy (BLEU , + on validation, , + on test), while sampling with a proper value of T makes the model achieve a higher score (, BLEU , + on validation, , + on test) than the first strategy (top-k random sampling).

1.3. Outline of the Paper

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a literature review of the approaches to NMT in the context of low-resource languages. In Section 3, we give an introduction to the methods and evaluation metrics used in our experiments. Section 4 introduces our experiments about the impact of back-translation with decoding strategies on the final performance of the model. Conclusion and future work are in the last section.

2. Related Work

In this section, we review literature about methods of NMT approaches developed for low-resource languages. According to our observation, statistical machine translation (SMT) and neural machine translation (NMT) are the two most commonly used machine translation approaches. Both are corpus-based, where source and target texts are required to build the translation system. However, due to numerous issues with SMT, NMT has become the mainstream machine translation engine [2,40,41,42,43].

We observe that in SMT, a model is separated into several sub-modules, such as the language model, the translation model, the reordering model, etc. These components work together to implement the translation function. On the other hand, NMT adopts the neural network to translate from the source language to the target language directly. NMT with an attention mechanism dynamically obtains the source language information, which is correlated to the current generating word. Therefore, NMT can derive the corresponding alignment information without setting up an alignment model, as in SMT [2,44]. Notably, NMT models are non-linear and smaller, but SMTs are linear and larger [45]. Also, we observe that NMT outperforms SMT by a large margin in all evaluation metrics [44,46,47,48,49,50]. The key advantage of NMT is that the source and target corpora can be trained directly in an encoder-decoder engine, which makes it fast and accurate [51]. The classic neural translation models involve sequence-to-sequence implementation with RNN encoder-decoder models [3,4,52,53,54,55], attention mechanisms [5,6,7,56,57,58,59,60,61], transformers [8,62,63,64,65], and so on. The applications include: Google Translate [7], Microsoft Translate [66], OpenNMT [67,68,69], and many others.

2.1. Neural Machine Translation (NMT) Architecture

In this section, we review the architectures used in NMT.

NMT is the mainstream approach for MT tasks. Let x be the input sentence in the source language, y be the output sentence in the target language, and be the parameters of the model; the objective of NMT is to find the Equation (1):

The basic architecture of NMT, which handles input and output of arbitrary length, is a Seq2Seq model with pre- and post-processing. In this section, we introduce an example framework of NMT using LSTM as the encoder and decoder of a Seq2Seq model, as illustrated in Figure 1. The selection of the Seq2Seq model (including encoder and decoder) is essential in the architecture of NMT [70,71]. A lot of network structures can be leveraged as Seq2Seq models, including RNN-based models (basic RNN, LSTM, GRU, or other variants), RNN-based models with encoder-decoder attention mechanisms, Transformer, and so on. For these structures, the key idea is to store and leverage the information from the input sequence and the generated part of the output sequence.

Figure 1.

Example framework of NMT with LSTM as encoder and decoder [72].

2.1.1. RNN Based Model

For Seq2Seq architecture with RNN models as the encoder and decoder [3,4,52,53,54,55], the framework was introduced in the previous section. Given an input sequence , in the i th step, the key features of an RNN model are two functions that take element and a hidden state from the last step as input and respectively output for post-processing, as well as a new hidden state for the next step. Basically, each function can simply be a stack of FC layers with non-linear activation. As the encoder and decoder, a basic RNN can tackle input and output sequences of arbitrary length. It encodes and exploits the information from the input sequence in a hidden state. However, in a basic RNN, the hidden state has limited capacity and gradually forgets information obtained from earlier elements of the input sequence, which is known as the long-term dependency problem. For instance, if we pass a long sentence to a basic RNN encoder, the output translation may have the wrong subject. Because the subject is at the beginning of the input and its information vanishes from its hidden state after many updates. Long short-term memory (LSTM) [73] alleviates the problem. It employs the LSTM unit as the function to update the hidden state in RNN structures and introduces the cell state as another variable to store information. At step t, input gate , forget gate , cell gate , and output gate are calculated from input and hidden state by corresponding learnable linear transformations with non-linear activation functions. Then the cell state and hidden state are updated as Equations (2) and (3):

where ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication. Notably, the hidden state can be used by the other functions to produce output .

In the aforementioned RNN models, the encoded information is accumulated in one or two hidden states, and the output sequence is generated according to such hidden states that contain the information of the entire input. However, when producing some part of the output sequence, the context information of the corresponding part in the input is usually more important. For example, suppose the model is translating “We go to the bank of river” into Bengali. When it translates “bank”, besides “bank” itself, the encoded information from “river” is necessary because it specifies the meaning of “bank”, while other parts of the input are less relevant.

2.1.2. RNN Based Model with Attention Mechanism

To address the aforementioned problem, Bahdanau et al. [5] introduce an attention mechanism in the RNN encoder-decoder architecture. In modified RNN models with an encoder-decoder attention mechanism, given the input sequence , all hidden states in the encoder phase are stored in a matrix . Then, in step i of the decoder phase, the hidden state (denoted as to identify) is updated as well, while a weighted sum of encoder hidden states is calculated to represent the information that is important for the output in this step. Formally, given the decoder hidden state (information of output status), the normalized weight for the encoder hidden state is as Equation (4):

where can simply be dot product of and in practice.

Then is, as Equation (5):

Then, can be used to generate output . Notice that in each , the information from the corresponding input and its neighbor is expected to be predominant, and a high value of makes contain more information from . Therefore, weight indicates the attention of the decoder on input . In general, RNN models with an encoder-decoder attention mechanism can focus on important parts of input information in the transduction task, which improves performance [5,6,7,56,57,58,59,60,61]. However, RNN models have an auto-regressive workflow in both training and inference; that is, the hidden state has a dependency on from the last step. Therefore, the input and output have to be processed step-by-step and thus cannot be accelerated by parallel computation. Moreover, the encoder-decoder attention mechanism works in the decoder phase, while context information is neglected when encoding the input sequence.

2.1.3. Transformer Based Model

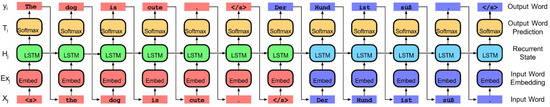

To address the aforementioned problems, the Transformer [8] is introduced, which receives the entire input sequence in only one step and uses self-attention to leverage context information for encoding the input sequence. For the details of the Transformer, we recommend referring to the original paper by Vaswani et al. [8]. Figure 2 shows the architecture of the Transformer. In the encoder phase, given the embedded input sequence (denoted as matrix ), it is first added by a positional encoding matrix, then goes through a stack of N encoder blocks ( in practice). In each encoder block, it is further encoded by a multi-head self-attention layer, which leverages context information. The production of head n ( in practice) is matrix , as is shown by Equations (6)–(11).

where , and WV are linear transformations that transfer embedded input into 3 vectors that play as query, key, and value, respectively in constructing context-considered representations, is the dimension of and , . Then the output of this layer O has the same size as the input, as shown in Equation (12).

Figure 2.

The Transformer Architecture. Reproduced from [8].

Then it is passed to a Feed Forward network (2 FC layers in practice) to obtain better representation. After each step, there is a residual connection and a layer normalization operation to keep the value of the output in a reasonable range. The output of the encoder is the context matrix , which is similar to the hidden state matrix in RNN. The decoder of the Transformer consists of blocks. It uses teacher forcing in the training stage; that is, the embedded input of first decoder block is right shifted ground truth where column i is similar to the input of decoder in step i for RNN. After positional encoding, it is passed to a masked multi-head self-attention layer, where is masked (set to 0) for all to prevent the contribution from future information when constructing a representation of . Another attention layer in the decoder block is similar to that in the encoder, with some differences are shown in Equations (13)–(15).

where is from C, the output of encoder, , . The output of the decoder in training (after (softmax)) is matrix , where is the vector of the probability distribution of candidate tokens for position i in the output sequence. The Transformer can be trained at high speed through parallel computation and has high capacity. It is the basis of many large language models (LLM), including chat generative pre-trained transformer (ChatGPT (ChatGPT https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt accessed on 1 August 2024)). Also, as stated earlier that BUET CSE NLP Group from Bangladesh, who are consistently working on optimizing the NLP tasks in Bengali, they also use Transformer as the basis of their study [14,15,16,17]. We further observe that prominent machine translation models [63,64,65] are built on top of the base transformer [8].

2.1.4. NMT Architecture in Our Study

For our study, we proceed with LSTM (without attention mechanism) and Transformer-based architecture, as demonstrated in Section 4. Notably, it is our baseline study as stated earlier. Moreover, we exploit the OpenNMT [67,68,69] toolkit to build the NMT framework for our study. OpenNMT is an open-source platform that provides various pre- and post-processing methods, as well as encoder and decoder model structures for sequence transduction tasks. By OpenNMT, we can explore the performance of customized LSTM and Transformer models in the English-Bengali translation task. Besides the selection of model structure, the training data are also critical for NMT tasks. However, as a low-resource language pair, English-Bengali translation lacks parallel data, so it is difficult to achieve a high accuracy in translation for low-resource language pairs (e.g., English-Bengali, or others). We observe that the prominent methods built on top of the baseline models can help address this issue and consequently help optimize the accuracy and quality of translations significantly [2,74].

2.2. Augmentation of Neural Machine Translation

Applying NMT to low-resource languages is a challenge. NMT is a data-driven task. Given the lack of parallel corpora, it is difficult to train a machine translation model to a high level of quality for the English-Bengali language pair. To address this, we employ strategies that focus on leveraging monolingual data and auxiliary language data, such as back-translation (round-trip translation) [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], pre-training on monolingual data [75,76], Pivot Language Technique [30,31,32], Leveraging Multi-Modal Data [33], and others.

2.2.1. Back-Translation

To augment the dataset, if we have a monolingual corpus in the target language, we can translate it into the source language by a translation engine in the reverse direction. Thus, we can have a pseudo-parallel corpus. We can then add the generated corpus to the original dataset to obtain an augmented dataset. This is called back-translation [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Similarly, in forward translation, if we have monolingual data in the source language, we can generate their counterparts in the target language using the same model we are training [25]. The new data can be regarded as data with noise because they are generated by models that are not trained very well yet rather than human translators (supposing they generate perfect translations). Since the original output of a translation model is a probability distribution of candidate words, to make the model more robust, Imamura et al. [77] employ random sampling instead of conventional beam search when generating translation. Meanwhile, the research work [78] adds noise to the pseudo-source sentences by deleting or masking certain words for the robustness of the model.

In Caswell et al. [26]’s research work, “Tagged Back-Translation” (TaggedBT), they show that setting a tag at the beginning of generated source sentences, instead of adding noise by dropping words, improves the translation performance. Especially in this work, by analyzing the entropy of decoder attention, the researchers noticed that when trained on normal back-translation data without a tag, the model concentrates more on the last input word (low entropy). It indicates a bias toward word-for-word translation. Meanwhile, models trained on tagged data show diffused attention (high entropy), indicating more attention to context. This implies that, when there is no tag, the model tends to use word-for-word translation for all input, while the tag helps the model identify sentences that belong to the back-translation and avoid using the word-for-word strategy on untagged input.

Dual learning [27] is another approach to back-translation that utilizes monolingual or low-resource datasets. In this method, Dual Learning [27] trains a source-target model and a target-source model at the same time. It combines the 2 models to make both input and output in the source language. Thus, the model can be trained only on source language data by minimizing the difference between input and output. Wang et al. [28] proposed letting models (agents) in different translation directions evaluate each other. In data diversification [29], models in 2 translation directions and the parallel corpus can be alternatively updated. That is, they first train models on the old corpus (updating models), then add pseudo-parallel data output by the trained models to the corpus (updating corpus).

2.2.2. Pre-Training on Monolingual Data

If there is no abundant parallel data, we can pre-train the model with monolingual data, forcing it to build a hidden representation space for source and target languages. Then the translation quality can be improved because the model gains a better understanding of the languages and better capability in generating the languages, even before translation training. The basic idea of monolingual pre-training is to request that the model reconstruct corrupted text.

In masked language modeling (MLM) [75], some words in the input sentence are replaced with mask tokens, and the model is tasked with predicting the masked words. Later, Conneau et al. [76] incorporated MLM with translation language modeling (TLM). In this work, instead of a single sentence in one language, a parallel sentence pair is concatenated and used as input. Zhu et al. [79] employ pre-trained BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) [75] to provide hidden representations of input sentences to the encoder and decoder designed in this work. These works pre-train the encoder and decoder, respectively. However, for the encoder-decoder attention mechanism, joint pre-training becomes important. In addition, to build a more robust model, some researchers seek more sophisticated methods to add noise during joint pre-training.

Song et al. [80] propose MAsked sequence-to-sequence pre-training (MASS). In this work, at the pre-training stage, some neighboring words in the sentence input to the encoder are masked, while the input to the decoder is further masked to force the decoder to employ the information extracted by the encoder. Likewise, we observe that at the pre-training stage of the text-to-text transfer transformer () model [62], some neighboring words are masked by a single token, and the model should reconstruct the masked content of arbitrary length. Lewis et al. [81] propose bidirectional and auto-regressive transformers (BART), which allow more types of document noise in joint pre-training, including masking (e.g., ), deleting words (e.g., without a mask token), sentence permutation (e.g., ), and so on.

2.2.3. Pivot Language Technique

Besides, some research employs rich resource languages that are different from the source and the target (called auxiliary languages [30]). For example, Cheng et al. [31] directly use English as the pivot between German and French by training a German-English model and an English-French model. Leng et al. [32] train a predictor to estimate the potential translation accuracy according to the choice of pivot language. The critical point in using an auxiliary language is to select an appropriate language. To better exploit the information from auxiliary languages, researchers may choose languages that are in the same or similar family. The auxiliary language may have the same writing system or similar grammar as the source or target language. In addition, if we choose languages whose speakers communicate frequently with speakers of source or target languages, the auxiliary language and source or target language may share expressions or words (called loan words), which helps build a shared hidden representation space for the translation model [82]. Tan et al. [83] define “similar languages” by clustering languages based on their embedding instead of prior domain knowledge. They train a multi-lingual translator, whose input is a sentence and a tag indicating its language. Then they extract the hidden representation of the tag (a vector) in the trained model as the embedding. Lin et al. [84] consider using auxiliary language models for transfer learning and propose LANGRANK, which selects the optimal language by ranking the candidates according to the data size, typological information, and so on. Niu et al. [85] proposes target-conditioned sampling. In this algorithm, the model first samples a sentence in the target language (low-resource), then samples its corresponding source sentence, where the source language is not fixed. The joint probability distribution is constructed to minimize the expected loss function of the translation task: . Then the sampling is according to the conditional probability distribution: . If we consider introducing auxiliary languages, we should balance the size of training data in different languages. Otherwise, the model cannot gain much knowledge about the low-resource language because of its finite capacity. Wang et al. [86] train a scorer that automatically decides the size of the data given the languages.

2.2.4. Leveraging Multi-Modal Data

Some studies also leverage multi-modal data. The basic idea is that multi-modal data has semantic information as well as text in any language, so researchers can embed an image, a piece of video, and/or a sentence in the same semantic space. Su et al. [33] conduct unsupervised learning of an English-French bi-directional translation model with (English, image) and (French, image) multi-modal monolingual corpora, where the images are not aligned. This model contains 2 Transformers for English and French, respectively, as well as a ResNet for the image part of the two datasets. For auto-encoding loss, in English, the English Transformer learns noisy words in a sentence according to the information extracted from images by the ResNet, while the French counterparts work similarly. For cycle-consistency loss, a pipeline like (En, encoder)→(Fr, decoder)→(Fr, encoder)→(En, decoder) is built to make both input and output English, and extracted image information is given to the English decoder. This allows researchers to avoid using an aligned English-French corpus. The model learns by minimizing the difference between input and output in English. Alongside, similar work is completed for the French corpus. Finally, in the English-French inference stage, an English sentence is input to the English encoder and the corresponding image to the French decoder, and then the model outputs the translated French sentence.

Instead of using multi-modal data for training directly, we can also employ such data to construct pseudo-parallel corpus. For example, given an image, Chen et al. [87] exploit image2text models in different languages to predict its caption. In this case, the short descriptions of the same image in different languages are expected to have the same meaning, thus a pseudo-parallel corpus is constructed.

2.2.5. Augmentation Approach in Our Study

Since NMT is data-driven, the aforementioned augmentation approaches are very effective in enhancing machine translation accuracy and quality. The concern is to know which approach is suitable for our study. We observe that, for low-resource language pairs, researchers either augment the parallel corpus by pseudo-sentence pairs or exploit the language data other than the parallel corpus. Back translation and forward translation are used in many research papers, combined with other modifications. In our research, we use back-translation on an English-Bengali translation model and explore the different decoding methods (sampling strategies) in back-translation, which is rare in previous research papers. Notably, top-k random sampling [35] and random sampling with temperature T [36] are the most commonly used and optimal decoding methods and are very effective in translation, as evaluated by the authors in [35,36]. Now, it comes to why we do not employ the other augmentation approaches mentioned in this literature. To this end, we start a comparative analysis with Pre-training on Monolingual Data. We observe that it is mostly used (also more effective) in masked language modeling and next-sentence prediction than machine translation. Next, it is pivot language technique. As stated earlier, it is to employ rich resource language pairs that are different from the source and the target, such as employing English as the pivot between German and French by training a German-English model and an English-French model. Thus, it is not effective if we do not have rich datasets for two different pairs with the pivot language as a medium. The last approach is leveraging multi-modal data. In our domain, it is difficult to get such datasets, and it is also resource-demanding since we need to conduct training for the language model and vision model. To this end, we find that back-translation with sampling strategies can help augment our machine translation study respectfully.

3. Methodology

In this section, we demonstrate the approaches adopted in our study for machine translation. In addition, we demonstrate the evaluation metrics in our experiments. Notably, for MT, we study the effect of model design and back-translation on the quality of MT models. Our focus is on low-resource English-Bengali translation.

As stated earlier, for our study, we proceed with LSTM (without attention mechanism) and Transformer-based architecture, as demonstrated in Section 4. As stated earlier, this is our baseline study to evaluate whether Transformer models can perform better in our study of English-Bengali machine translation. In our further study, we use the baseline Transformer as the basis and employ back-translation with the decoding strategies mentioned earlier. Moreover, we exploit the OpenNMT [67,68,69] toolkit to build the framework from input text in the source language to output text in the target language. OpenNMT is an open-source platform that provides various pre-processing and post-processing methods as well as encoder and decoder model structures for sequence transduction tasks. By using OpenNMT, we can explore the performance of customized LSTM and Transformer models in the English-Bengali translation task. Besides the selection of model structure, the training data is also critical for NMT tasks. However, as a low-resource language pair, the English-Bengali translation lacks parallel data. Therefore, we employ back-translation to augment the training data.

3.1. Back-Translation with OpenNMT

The framework of back-translation we conduct is as follows:

- We train an English-Bengali model and a Bengali-English model on the original parallel corpus.

- We introduce a Bengali monolingual corpus and use the trained Bn-En model to translate it into English; thus, we have another English-Bengali corpus (pseudo-corpus).

- We use the two corpora to train a new English-Bengali model.

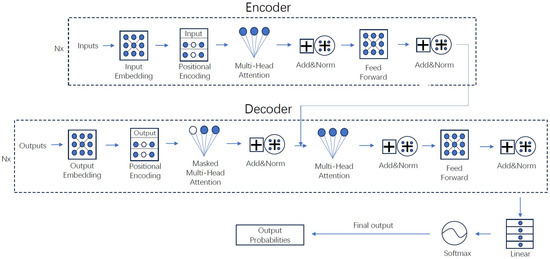

Notably, when preparing the pseudo-parallel data by back translation, we use two decoding methods: top-k random sampling and random sampling with temperature T. To demonstrate them, we observe the last steps of predicting an output word. The direct output from the decoder is a vector. The official documentation of OpenNMT-py (OpenNMT-py Official Documentation https://opennmt.net/OpenNMT-py/options/translate.html accessed on 1 August 2024) [67,68,69] use the term “logits” for it. The logits vector is then processed by softmax and becomes a probability distribution, according to which the model samples the output word. Therefore, top-k sampling is easy to understand. Supposing that , it simply picks up the 3 words with the highest probabilities and sets the probabilities of the other words to ( in practice). Another strategy is to introduce temperature T, a positive float variable, to modify the probability distribution. That is, we divide the logits by T before feeding them into softmax. In this strategy, all words in the vocabulary of the model are regarded as candidates. For better understanding, we consider logits with 2 elements: {‘I’:0, ‘you’:x}, notice that x can be any value, positive or negative. After softmax with temperature T (can be any positive value), P(‘’) becomes Equation (16):

Figure 3 shows the result of P(‘’) at different temperatures. At a low temperature (), if the probability of ‘you’ (x) is lower than that of ‘I’ (zero), then the final probability is P(‘’) = 0, and thus ’) = 1 and vice versa. Therefore, at a low temperature, the probability distribution becomes sharp, and the sampling algorithm concentrates more on the top words. Meanwhile, at a high temperature (), the probability distribution becomes flat, and all words have similar probabilities for sampling, despite the raw output (x) from the decoder.

Figure 3.

The relation between x and ’) at different temperatures T.

Using these two decoding methods, with different values of k or T, we investigate the performance of models trained on data with different levels of noise. First, we compare the performance of LSTM and Transformer networks in both translation directions. Then we choose the better architecture and back-translate (Bengali-English) the Bengali part of the training data to create a pseudo-parallel corpus and add it to the original training set. We keep the validation set invariant for consistency. At this stage, we generate different translations by setting the random sampling parameter, (the argmax), 5, and 10. We also generate translations with . Note that if we set , then the top 1 word with the maximum probability will have and will be sampled. Therefore, this is equivalent to top- random sampling. In addition, setting in top-k allows the model to sample from all tokens in the vocabulary, while setting temperature leads to the unmodified probability distribution for all tokens in the vocabulary. Both of the cases are equivalent to the setup where neither top-k nor temperature sampling is used. It is denoted as “no strategy” in this article.

Finally, we train new models on the augmented training data and compare their performance on the test set, which is from another dataset. In the experiment, we set the decoding methods using OpenNMT.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics: BLEU

BilinguaL Evaluation Understudy (BLEU) [12] is a widely used metric in machine translation. Given a sentence predicted by the model and the reference translation (usually generated by humans). The BLEU score represents the similarity between them. To compute BLEU, the first step is, for to N, counting , the total n-grams in the prediction, and , the n-grams in the prediction that are also found in the reference translation. We stop counting some n-grams in when they appear more frequently in the prediction than in the reference translation. Then we obtain and a brevity penalty as Equation (17):

which is introduced to reduce the score for short prediction. Finally, the BLEU is calculated as Equation (18):

In practice, we set and all weights , as in the original literature. We multiply 100 by the original BLEU value to make it a score in a 0 to 100 interval by convention.

4. Experiments

In this section, we present our experiments. We start by demonstrating the datasets used, then the pre-process tasks and model configuration, and finally, we show the experimental results.

4.1. Datasets

For English-Bengali machine translation, there are limited parallel corpora (∼1 k to ∼0.1 M sentences) compared with rich resource language pairs like English-Chinese (∼10 M to ∼100 M sentences). Most of the datasets have parallel contents that are translated or checked by humans, while some are automatically crawled and scored by algorithms. We obtain the following freely accessible datasets from OPUS [88], except SUPara.

- WikiMatrix [89] is collected from Wikipedia in 1620 language pairs by data mining technology. The pages describing the same entity in different languages can be related, but it may be hard to construct a sentence-to-sentence alignment. Therefore, the corresponding contents are “comparable” rather than “parallel”. For English-Bengali, it has 0.7 M pairs of sentences. In practice, we can separately use its English part and Bengali part as a monolingual corpus.

- GlobalVoices [90] is extracted from Global Voice news articles. The constructors leverage human evaluation to rate the aligned contents and then filter out low-quality translations. For the English-Bengali language pair, it contains 0.1 M pairs of sentences.

- Tanzil (Tanzil translations https://tanzil.net/trans/ accessed on 1 August 2024) is a project that provides the Quran in different languages, including 0.2 M sentence pairs in English-Bengali. The translations are submitted by users. Notably, aligned bilingual versions can be downloaded from OPUS.

- Tatoeba (Tatoeba https://tatoeba.org/ accessed on 1 August 2024) is an open and free multi-language collection of sentences and translations. Its name means “for example” in Japanese. The version of the English-Bengali corpus we use was updated on 12 April 2023, and contains 5.6 k pairs of sentences. Most of the sentences in this dataset are selected from short daily conversations.

- Shahjalal University Parallel (SUPara) corpus [91] is a collection of aligned English-Bengali sentences. It is constructed with a balance of text sources, including literature, administrative texts, journalistic texts, and so on. It has 21,158 pairs of sentences. However, the only source we find for this corpus is not freely available. Therefore, we only obtain 500 pairs of sentences (known as the test set of the SUPara benchmark) and employ them as the final test set.

We refer to Table 1 for some example sentences from the aforementioned datasets. It can be observed that some of the translations do not convey the exact same meaning. We plan to address this issue.

Table 1.

Parallel sentences from datasets.

4.2. Pre-Processing

In this section, we present the pre-processing tasks of our study [92].

- Experimental Setup: In our study, we conducted our experiments on the supercomputer at Macau University of Science and Technology. The setup for a personal user is: CPU: Intel Xeon E52098, GPU: NVIDIA Tesla V100.

- Data Filtering: Upon receiving the dataset, we first perform the data filtering. With data filtering, we prune the low-quality segments that can help optimize the translation accuracy and quality. Especially without filtering, the dataset may include misalignments, duplicates, empty segments, and other issues.

- Tokenization/Subwording: To train our model, we first need to build a vocabulary for the machine translation task. To this end, we usually tokenize/split sentences into words, which is called Word-based tokenization. This issue is that, in this case, our model is limited to learning a certain number of vocabulary tokens. To address this issue, subword tokenization is the preferred method over whole words. During translation, if the model encounters a new word/token that resembles one in its vocabulary, it may attempt to translate it instead of labeling it as “unknown” or “unk”. The most commonly used subwording approaches are byte pair encoding (BPE) and the Unigram model [93]. In our experimental analysis, we observe that the results of these two models are almost similar. Notably, we find that both models are integrated with OpenNMT-py, as we stated earlier that we conduct our analysis with OpenNMT-py. In our study, we by default use the Unigram model for subword tokenization. Notably, after translation, we have to “desubword” our text back employing the same subword tokenization model.

- Data Splitting: We use GlobalVoices, Tanzil, and Tatoeba datasets for both training and validation. We extract the first 500 pairs of sentences from each dataset to construct the validation set, then leave the rest for training. On the other hand, instead of extracting the test set from the datasets used for training and validation, we use the SUPara dataset (SUPara benchmark) for testing.

After the pre-processing tasks, next comes our experimental study.

4.3. Model Configuration

In this section, we present our model configuration. Notably, we begin our experimental analysis by comparing the performance of LSTM and Transformer models in both translation directions, and we conduct the analysis with OpenNMT-py. With OpenNMT, the basic configurations of models are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Training Configuration.

We design two models with LSTM and Transformer as follows:

- LSTM based Model: A deep LSTM model that uses 2 stacks of 4 LSTM units as encoder and decoder with 512 hidden size.

- Transformer-based Model: A simplified Transformer with only two blocks in the encoder and two blocks in the decoder (by default it is 6 for encoder and decoder) with 512 hidden-size, 512 feed-forward-size. We set two heads in multi-head attention instead of eight heads in the default setup. Because of the lack of powerful computing resources and to reduce the carbon footprint, we designed a basic Transformer model.

The simplification is to avoid overfitting of models on the training set. Notably, custom-configured models can be built. Especially after the preliminary experiment with LSTM and Transformer, the better model is then used for back-translation. To train a translation model in the reversed direction (Bn-En), we swap the source and target of vocabularies, as well as those of training and validation data. Notably, when we get the translation file after passing the test dataset to the model, we need to perform the desubwording of the translated output using the same subword tokenization model as stated in the Tokenization/Subwording stage of the pre-processing section. After that, we evaluate the translated output using the BLEU metric. These are the post-processing stages of our study.

As stated earlier, we use GlobalVoices, Tanzil, and Tatoeba datasets for both training and validation. We extract the first 500 pairs of sentences from each dataset to construct the validation set, then leave the rest for training. The vocabularies of both languages are generated from the first 200,000 pairs of sentences in the training set. In each vocabulary, the words that appear only once in the training data are neglected. We train one Transformer and one LSTM model on each translation direction for 50,000 epochs and save a checkpoint every 1000 epochs. Then we compute the BLEU score on the validation set at checkpoints.

4.4. Experiment Results and Discussion

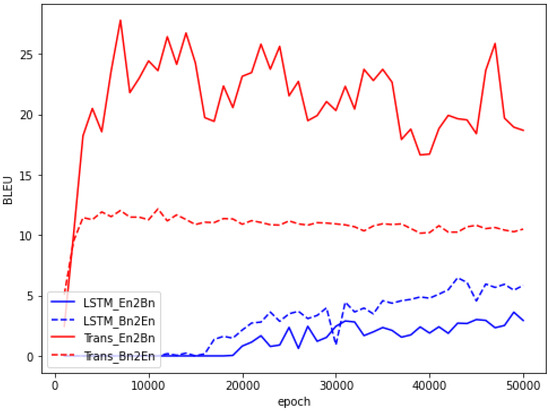

In this section, we present the results of our experiment and their discussion. As Figure 4 shows, Transformer models on both translation directions converge rapidly and outperform LSTM models. LSTM models need much more training epochs and show lower scores. This phenomenon implies that we can choose better architectures, like Transformer, to optimize the translation. Notably, according to our observation, the Bengali-English Transformer (for back-translation) has a higher BLEU score than the En-Bn by LSTM. One probable explanation is that a single sentence in English corresponds to several translations based on the status of speakers, but that extra information is lost in the corpus. Meanwhile, the result is reversed for the Transformer, which warrants further research.

Figure 4.

BLEU scores on the validation set over epochs for different models.

We then use the best Transformer Bn-En checkpoint (11,000 epochs) to back-translate the Bengali part of the WikiMatrix dataset. We obtain 7 versions of the translation, corresponding to different generation strategies. For top-k random sampling strategy, we randomly sample from the k most probable candidate words when generating the translation, with . Another method is to randomly sample from all candidate words with the probability modified by temperature T, with T = 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1.

As discussed earlier, (frozen) means that the word with the highest probability survives, while other choices have zero probability. This case is equivalent to the top 1 random sampling (argmax). Similarly, is equivalent to the “no strategy” setup because dividing by 1 does not change the probability. For large T (suppose ), the probability distribution becomes flat, which means the model degrades into an untrained situation (every word has the same probability). It destroys the modeled probability distribution, causing many writing errors to appear in the back-translated text. Therefore, we do not examine for a higher temperature.

The translations are separately added to the training data. Thus, we have seven versions of augmented training sets. Next, we train a new Transformer model on each of the seven augmented training data for 50,000 epochs, pick up their best checkpoints on the validation set, and compare their performance on the test set. Instead of extracting the test set from the datasets used for training and validation, we use a small part of the SUPara dataset (SUPara benchmark) for testing. With this approach, we expect to better examine the generalizability.

Table 3 shows the results of different setups on the validation set and the test set. Note that and refer to the same case: the argmax sampling in back-translation, and that the top-all setup () and the setup are the “no strategy” cases. According to the test, we obtained three results. First, the Transformer model has much better performance than LSTM on the base training set. Therefore, Transformer is promising for translating low-resource languages. Second, we can use back-translation to boost the translation performance, but the adoption of the top-k random sampling strategy weakens the effect of back-translation. Third, back-translation with temperature T sampling achieves higher BLEU with , while too low or too high T values reduce the enhancement.

Table 3.

English-Bengali NMT results on test set. We bold faced the best result for each set of comparisons. Note that in the base case, the training set is not augmented by back-translation.

5. Summary

5.1. Conclusion and Contributions

In this article, we develop a machine translation method to translate English texts to Bengali texts. In particular, we have evaluated LSTM and Transformer architectures. The experiment shows that the Transformer model outperforms LSTM in both directions of the English-Bengali translation task. The performance enhancement indicates that we can exploit Transformer in designing better NMT architectures for low-resource language pairs like English-Bengali. We then investigate the effect of back-translation on the Transformer for the English-to-Bengali translation task. In our experiments, we analyze two decoding methods: top-k random sampling and random sampling with temperature T. According to the results, back-translation with proper parameters improves translation accuracy through data augmentation. As the experiment shows, if we take top-k random sampling in back-translation, we can let all words in the vocabulary become candidates to achieve the best results. However, while the top-all () setup is shown as the optimal case in the top-k strategy, it is theoretically equivalent to the “no strategy” setup, which can also be regarded as case in temperature T sampling, where we can optimize T for even better results. Therefore, to obtain the best back-translation output, it is better to adopt random sampling with temperature T, and explore the optimal value of T between 0 and 1. We observed that using random sampling with temperature in back-translation makes the model perform best. Therefore, we can augment the English-Bengali corpus by back-translation incorporating the decoding strategy of random sampling with temperature T over and over again, which helps the model gain a higher generalization ability. Finally, it can help improve the accuracy and quality of translation. However, in the evaluation, we did not get a very high BLEU score. Notably, in our experiments, we have built a simplified Transformer with only two blocks in the encoder and two blocks in the decoder, having only two heads in the multi-head attention because of the lack of powerful computing resources and to reduce the carbon footprint. Above all, our study shows how we can augment the datasets for low-resource languages and, finally, how to enhance the learnability of the model toward optimizing machine translation tasks.

5.2. Limitations and Further Study

We can further optimize the English-Bengali translation in several ways as follows:

- For English-Bengali NMT, we can augment the limited parallel corpus by back- and forward translation. Since these methods simply need monolingual data, training models to generate monolingual text in English and Bengali will be beneficial for further study.

- We can explore the explanation for the phenomenon that the BLEU of Bengali to English translation by the Transformer is lower than that of the En to Bn translation.

- We can develop an algorithm to automatically refine the existing parallel corpus.

- We can exploit different datasets for training, validation, and testing. Compared with dividing one dataset into three parts, this method is expected to help select the model with the best generalization ability.

- We can employ our study for domain-specific translation tasks. Achieving high accuracy in a domain-specific machine translation is very challenging due to the lack of authentic parallel corpora. Notably, even if we have the high-resource parallel corpora for domain-specific translation tasks, for a model, it is a very complex task to understand the languages because of domain-specific vocabularies. Therefore, there is an urgent need to build domain-specific machine translation engines, and we plan to step into it in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.M., C.W., Y.C. (Yijun Chen), Y.C. (Yuning Cheng) and Y.H.; Methodology, S.K.M., C.W., Y.C. (Yijun Chen), Y.C. (Yuning Cheng), Y.H., H.-N.D. and H.M.D.K.; Software, C.W., S.K.M., Y.C. (Yuning Cheng), Y.H., Y.C. (Yijun Chen) and H.M.D.K.; Validation, C.W. and S.K.M.; Formal analysis, S.K.M., C.W., Y.C. (Yuning Cheng), Y.H., Y.C. (Yijun Chen), H.-N.D. and H.M.D.K.; Investigation, C.W. and S.K.M.; Resources, C.W. and S.K.M.; Data curation, C.W. and S.K.M.; Writing—original draft, S.K.M., C.W., Y.C. (Yijun Chen) and H.M.D.K.; Writing—review & editing, S.K.M., C.W., Y.C. (Yuning Cheng), Y.H., Y.C. (Yijun Chen), H.-N.D. and H.M.D.K.; Visualization, C.W. and S.K.M.; Supervision, S.K.M. and H.-N.D.; Project administration, S.K.M.; Funding acquisition, S.K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The Science and Technology Development Fund of Macao, Macao SAR, China under grant 0033/2022/ITP.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in [WikiMatrix] at [10.18653/v1/2021.eacl-main.115], reference number [89]; in [GlobalVoices] at [10.18653/v1/D19-5411], reference number [90]; in [SUPara] at [10.21227/gz0b-5p24], reference number [91]. Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://tanzil.net/trans/; https://tatoeba.org/ (accessed on 1 August 2024).

Acknowledgments

Authors gratefully acknowledge funding source. The authors also would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their quality reviews and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Full Form |

| argmax | arguments of the maxima |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional Long Short Term Memory |

| BLEU | Bilingual Evaluation Understudy |

| Bn-En | Bengali to English |

| BPE | Byte Pair Encoding |

| ChatGPT | Chat Generative Pre-Trained Transformer |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| En-Bn | English to Bengali |

| FC | Fully Connected |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| LLM | Large Language Models |

| LSTM | Long Short Term Memory |

| MT | Machine Translation |

| NMT | Neural Machine Translation |

| MASS | MAsked Sequence to Sequence |

| MLM | Masked Language Modeling |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| SUPara | Shahjalal University Parallel |

| SMT | Statistical Machine Translation |

| TLM | Tanslation Language Modeling |

| T5 | Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer |

References

- Stahlberg, F. Neural machine translation: A review. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2020, 69, 343–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.K.; Zhang, H.; Kabir, H.D.; Ni, K.; Dai, H.N. Machine translation and its evaluation: A study. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 10137–10226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Van Merriënboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.1078. [Google Scholar]

- Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O.; Le, Q.V. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, USA, 8–13 December 2014; pp. 3104–3112. [Google Scholar]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar]

- Luong, M.T.; Pham, H.; Manning, C.D. Effective Approaches to Attention-based Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Lisbon, Portugal, 17–21 September 2015; pp. 1412–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Schuster, M.; Chen, Z.; Le, Q.V.; Norouzi, M.; Macherey, W.; Krikun, M.; Cao, Y.; Gao, Q.; Macherey, K.; et al. Google’s neural machine translation system: Bridging the gap between human and machine translation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.08144. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, D. Transformers for Natural Language Processing: Build Innovative Deep Neural Network Architectures for NLP with Python, PyTorch, TensorFlow, BERT, RoBERTa, and More; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, H.D.; Mondal, S.K.; Alam, S.B.; Acharya, U.R. Transfer learning with spinally shared layers. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 163, 111908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mumin, M.A.; Seddiqui, M.H.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Islam, M.J. Neural machine translation for low-resource English-Bangla. J. Comput. Sci. 2019, 15, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. BLEU: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL ’02), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 7–12 July 2002; pp. 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunchukuttan, A.; Kakwani, D.; Golla, S.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Khapra, M.M.; Kumar, P. Ai4bharat-indicnlp corpus: Monolingual corpora and word embeddings for indic languages. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.00085. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Hasan, T.; Ahmad, W.; Li, Y.F.; Kang, Y.B.; Shahriyar, R. CrossSum: Beyond English-Centric Cross-Lingual Summarization for 1,500+ Language Pairs. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; pp. 2541–2564. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Hasan, T.; Ahmad, W.; Mubasshir, K.S.; Islam, M.S.; Iqbal, A.; Rahman, M.S.; Shahriyar, R. BanglaBERT: Language Model Pretraining and Benchmarks for Low-Resource Language Understanding Evaluation in Bangla. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2022, Seattle, WA, USA, 10–15 July 2022; pp. 1318–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Hasan, T.; Ahmad, W.U.; Shahriyar, R. BanglaNLG and BanglaT5: Benchmarks and Resources for Evaluating Low-Resource Natural Language Generation in Bangla. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EACL 2023, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 2–6 May 2023; pp. 726–735. [Google Scholar]

- Akil, A.; Sultana, N.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Shahriyar, R. BanglaParaphrase: A High-Quality Bangla Paraphrase Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2nd Conference of the Asia-Pacific Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 12th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 2: Short Papers), Online, 20–23 November 2022; pp. 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, T.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Samin, K.; Hasan, M.; Basak, M.; Rahman, M.S.; Shahriyar, R. Not Low-Resource Anymore: Aligner Ensembling, Batch Filtering, and New Datasets for Bengali-English Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 2612–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sha, J.; Shi, C. Revisiting back-translation for low-resource machine translation between Chinese and Vietnamese. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 119931–119939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zeng, Y.; Cao, D.; Lu, S. Video-guided machine translation via dual-level back-translation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 245, 108598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.X.; Yang, Y.T.; Dong, R.; Chen, Y.H.; Zhang, W.B. A Joint Back-Translation and Transfer Learning Method for Low-Resource Neural Machine Translation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 6140153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmumin, I.; Galadanci, B.S.; Aliyu, G. Tag-less back-translation. Mach. Transl. 2021, 35, 519–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Saxena, S.; Daniel, P. Improved unsupervised neural machine translation with semantically weighted back translation for morphologically rich and low resource languages. Neural Process. Lett. 2022, 54, 1707–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennrich, R.; Haddow, B.; Birch, A. Improving Neural Machine Translation Models with Monolingual Data. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016; pp. 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zong, C. Exploiting Source-side Monolingual Data in Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Austin, TX, USA, 1–5 November 2016; pp. 1535–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caswell, I.; Chelba, C.; Grangier, D. Tagged Back-Translation. In Proceedings of the Fourth Conference on Machine Translation (Volume 1: Research Papers), Florence, Italy, 1–2 August 2019; pp. 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T. Dual Learning; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, Y.; He, T.; Tian, F.; Qin, T.; Zhai, C.; Liu, T.Y. Multi-agent dual learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2019, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, X.P.; Joty, S.; Wu, K.; Aw, A.T. Data Diversification: A Simple Strategy For Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual, 6–12 December 2010; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 10018–10029. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Tan, X.; Luo, R.; Qin, T.; Liu, T.Y. A Survey on Low-Resource Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Montreal, QC, Canada, 19–27 August 2021; pp. 4636–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Sun, M.; Xu, W. Joint Training for Pivot-based Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-17, Melbourne, Australia, 19–25 August 2017; pp. 3974–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leng, Y.; Tan, X.; Qin, T.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, T.Y. Unsupervised Pivot Translation for Distant Languages. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Fan, K.; Bach, N.; Kuo, C.; Huang, F. Unsupervised Multi-Modal Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 10474–10483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, M.; Al-Onaizan, Y. Beam Search Strategies for Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Neural Machine Translation, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 4 August 2017; pp. 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, A.; Lewis, M.; Dauphin, Y. Hierarchical Neural Story Generation. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippolito, D.; Kriz, R.; Sedoc, J.; Kustikova, M.; Callison-Burch, C. Comparison of Diverse Decoding Methods from Conditional Language Models. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 3752–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H.D.; Mondal, S.K.; Khanam, S.; Khosravi, A.; Rahman, S.; Qazani, M.R.C.; Alizadehsani, R.; Asadi, H.; Mohamed, S.; Nahavandi, S.; et al. Uncertainty aware neural network from similarity and sensitivity. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 149, 111027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannattee, P.; Kumwilaisak, W.; Hansakunbuntheung, C.; Thatphithakkul, N.; Kuo, C.C.J. American Sign language fingerspelling recognition in the wild with spatio temporal feature extraction and multi-task learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 243, 122901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H.D.; Khanam, S.; Khozeimeh, F.; Khosravi, A.; Mondal, S.K.; Nahavandi, S.; Acharya, U.R. Aleatory-aware deep uncertainty quantification for transfer learning. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 143, 105246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.A.; Elsayed, A.A.; Hassan, Y.; Abdou, M.A. Neural machine translation: Past, present, and future. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 15919–15931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruf, S.; Saleh, F.; Haffari, G. A survey on document-level neural machine translation: Methods and evaluation. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimova, B.; Pikhart, M.; Benites, A.D.; Lehr, C.; Sanchez-Stockhammer, C. Neural machine translation in foreign language teaching and learning: A systematic review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 663–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragni, V.; Nunes Vieira, L. What has changed with neural machine translation? A critical review of human factors. Perspectives 2022, 30, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentivogli, L.; Bisazza, A.; Cettolo, M.; Federico, M. Neural versus phrase-based machine translation quality: A case study. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.04631. [Google Scholar]

- Besacier, L.; Blanchon, H. Comparing Statistical Machine Translation and Neural Machine Translation Performances; Laboratoire LIG, Université Grenoble Alpes: Saint-Martin-d’Hères, France, 2017; Available online: https://evaluerlata.hypotheses.org/files/2017/07/Laurent-Besacier-NMTvsSMT.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Yamada, M. The impact of Google Neural Machine Translation on Post-editing by student translators. J. Spec. Transl. 2019, 31, 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Stasimioti, M.; Sosoni, V.; Kermanidis, K.L.; Mouratidis, D. Machine Translation Quality: A comparative evaluation of SMT, NMT and tailored-NMT outputs. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation, Lisbon, Portugal, 4–6 May 2020; pp. 441–450. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Comparing and Analyzing Cohesive Devices of SMT and NMT from Chinese to English: A Diachronic Approach. Open J. Mod. Linguist. 2020, 10, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Anik, M.S.H.; Islam, A.B.M.A.A. Towards achieving a delicate blending between rule-based translator and neural machine translator. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 12141–12167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.; Carré, A. How to choose a suitable neural machine translation solution: Evaluation of MT quality. Mach. Transl. Everyone Empower. Users Age Artif. Intell. 2022, 18, 51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Ortiz, J.A.; Forcada, M.L.; Sánchez-Martínez, F. How neural machine translation works. Mach. Transl. Everyone Empower. Users Age Artif. Intell. 2022, 18, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, K.; Van Merriënboer, B.; Bahdanau, D.; Bengio, Y. On the properties of neural machine translation: Encoder-decoder approaches. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1259. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, D.; David, P.E.; Mittal, D.; Jain, A. Neural machine translation using recurrent neural network. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2020, 9, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, U.; Mohd Rahim, M.S.; Abid, A. A multi-stack RNN-based neural machine translation model for English to Pakistan sign language translation. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 13225–13238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vathsala, M.; Holi, G. RNN based machine translation and transliteration for Twitter data. Int. J. Speech Technol. 2020, 23, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wei, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, T.; Hu, G. Attention-over-attention neural networks for reading comprehension. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.04423. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, L.; He, S.; Wang, M.; Long, F.; Su, J. Bilingual attention based neural machine translation. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israr, H.; Khan, S.A.; Tahir, M.A.; Shahzad, M.K.; Ahmad, M.; Zain, J.M. Neural Machine Translation Models with Attention-Based Dropout Layer. Comput. Mater. Contin.a 2023, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xiong, D.; Xie, J.; Su, J. Neural machine translation with GRU-gated attention model. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 31, 4688–4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Komachi, M.; Kajiwara, T.; Chu, C. Region-attentive multimodal neural machine translation. Neurocomputing 2022, 476, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, L.; Tu, Z.; Li, G.; Shi, S.; Meng, M.Q.H. Attending from foresight: A novel attention mechanism for neural machine translation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech Lang. Process. 2021, 29, 2606–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, L.; Tran, P.; Nguyen, H. Improving Transformer-Based Neural Machine Translation with Prior Alignments. Complexity 2021, 2021, 5515407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniata, L.H.; Ampomah, I.K.; Park, S. A transformer-based neural machine translation model for Arabic dialects that utilizes subword units. Sensors 2021, 21, 6509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zong, C. Transformer: A general framework from machine translation to others. Mach. Intell. Res. 2023, 20, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junczys-Dowmunt, M. Microsoft Translator at WMT 2019: Towards Large-Scale Document-Level Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Fourth Conference on Machine Translation (Volume 2: Shared Task Papers, Day 1), Florence, Italy, 1–2 August 2019; pp. 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, G.; Kim, Y.; Deng, Y.; Senellart, J.; Rush, A. OpenNMT: Open-Source Toolkit for Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the ACL 2017, System Demonstrations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017; pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, G.; Kim, Y.; Deng, Y.; Nguyen, V.; Senellart, J.; Rush, A. OpenNMT: Neural Machine Translation Toolkit. In Proceedings of the 13th Conference of the Association for Machine Translation in the Americas (Volume 1: Research Track), Boston, MA, USA, 17–21 March 2018; pp. 177–184. [Google Scholar]