Abstract

Introduction: Class II growing patients can be successfully treated with the Herbst appliance, nevertheless this therapy generally produces side effects, such as upper incisors retroclination and lower incisors proclination, which eventually could reduce mandibular forward advancement. Treatment objectives: The purpose of this article is to show a treatment of class II malocclusion with crowding in both arches by a skeletally reinforced Herbst appliance. Treatment description: Two miniscrews were applied in the lower arch to control lower incisors proclination and in the upper arch an Hybrid palatal expander was used. Results: the correction of the severe class II malocclusion was obtained with mandibular advancement, avoiding lower incisors proclination with control also of the upper incisors. Upper crowding with lack of space for upper canine alignment was corrected. Conclusions: Upper and lower miniscrews worked successfully as anchorage for the entire treatment.

1. Introduction

Class II is one of the most common malocclusions. It affects one third of the Caucasian population [1].

A retrognatic mandible position is the most common feature [1,2] in this malocclusion and different therapeutical approaches have been proposed [2,3,4].

These include removable functional appliances (RFAs) such as the Twin Block [4], Fraenkel [5] and others, and the fix functional appliances (FFAs) such as the Herbst [6,7,8,9], MARA [10], Forsus [11] and others.

The Herbst dental and skeletal effects include mandibular advancement, overjet reduction, anterior displacement of the mandibular arch and posterior displacement of the maxillary arch.

The weak control of upper and lower incisors, as well as the uncontrolled movement of posterior teeth are Herbst side effects due to anchorage loss. Mandibular incisors proclination and maxillary incisors retroclination could reduce mandibular enhancement space.

A better control of unfavorable teeth movements may lead to greater skeletal effects as reported by the latest articles published in recent years [12,13,14].

With this case report, the authors describe the results of a class II growing patient treatment using a skeletally reinforced Herbst with miniscrews inserted in the lower and upper arch as anchorage reinforcement to reduce classic side effects of Herbst treatment and improve the patient aesthetic final results.

2. Diagnosis and Etiology

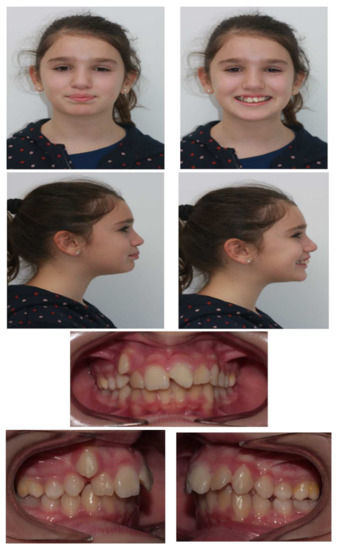

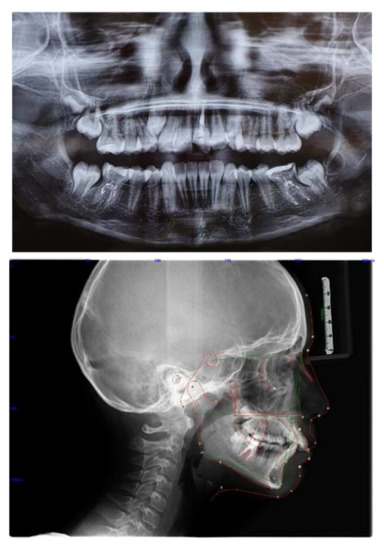

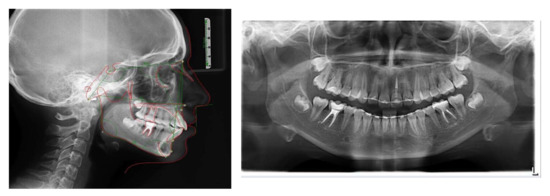

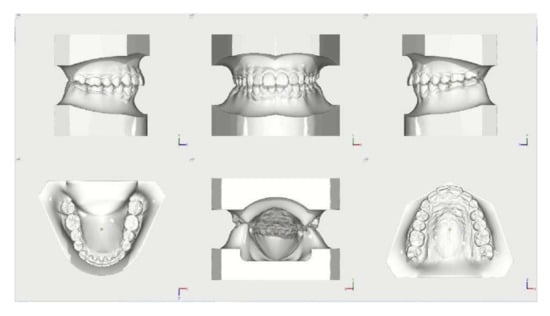

A 11-year-old patient presented to the private practice with her parents with a chief complaint of an unattractive smile, mainly due to an upper canine. The facial analysis showed an hypodivergent facial type with a reduced lower-third of the face, a convex profile with mandibular retrusion and upper lip protrusion with a proper nasolabial angle (Figure 1). The mini-esthetic analysis showed a superior inter-incisive line not coinciding with the median of the face, migrated on the left side, a ratio between arch amplitude and amplitude of the smile in the norm, and a reduced exposure of the smile with an irregular and asymmetrical smile arc. The intraoral clinical analysis revealed sagittal relationships of molar class II and canine class II, an upper interincisive line migrated on the left side, decreased transversal development of the upper arch, a severe crowding in the upper arch with a lack of space for 1.3 alignment, a 6.5 mm overjet, a 3.5 mm overbite, and an increased Spee curve (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The patient asked for treatment because the upper right canine (UR3) was not aligned and ectopic in the upper arch. Panoramic radiography and lateral cephalogram were required to confirm the diagnostic hypothesis of class II malocclusion and to measure incisors proclination. The cephalometric analysis showed a skeletal class II, hypodivergence and proclination of the upper and lower incisors (Figure 3, Table 1 and Table 2).

Figure 1.

Pretreatment facial and intraoral photographs.

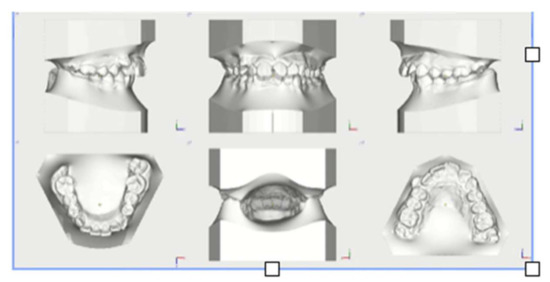

Figure 2.

Pretreatment models.

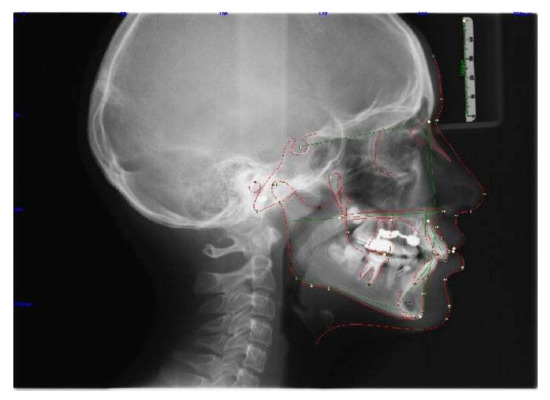

Figure 3.

Pretreatment radiographs and cephalometric analysis.

Table 1.

Cephalometrics parameters.

Table 2.

Pancherz analysis at T0, T1, T2.

3. Treatment Objectives

The treatments goals were aesthetic and functional.

The objectives of the treatment were:

- -

- Recovery of the sagittal and transverse dimensions of the upper arch

- -

- Correction of skeletal Class II

- -

- Space recovery for alignment 1.3

- -

- Resolution of Class II molar and canine relationships

- -

- Resolution of deep bite

- -

- Alignment and leveling, correction of the lower Spee curve

- -

- Occlusion finishing

- -

- Retention.

The treatment aimed to correct the transverse dimension of the upper arch and class II malocclusion with mandibular advancement without loss of anchorage, avoiding lower incisors proclination and upper molar distal movement.

4. Treatment Alternatives

Some treatment options existed in order to treat this class II patient, such as functional removable orthopedics or other fix functional appliances, like MARA or Forsus Fatigue Resistant Device, etc. As a first step, the upper arch had to be expanded to create space for 1.3 alignment and then Class II malocclusion could be corrected with a removable appliance or a fixed appliance without skeletal anchorage.

This conventional treatment without skeletal anchorage could effectively correct class II malocclusion but it could not avoid side effects due to the anchorage loss, such as lower incisors proclination.

5. Treatment Progress

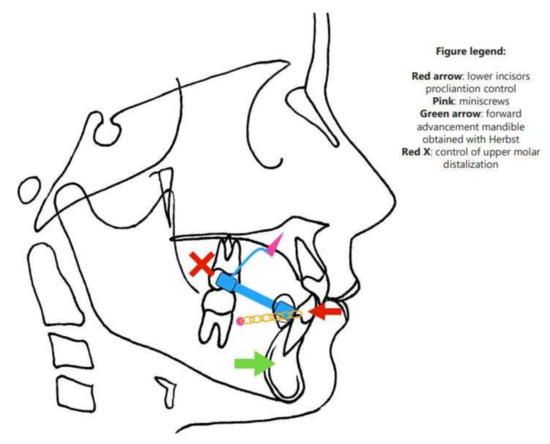

To achieve the treatment objectives, a hybrid palatal expander was initially applied, anchored to two palatal miniscrews and to first upper molars bands, to prepare the arch in a transverse direction. The patient’s parents gave their informed consent for the treatment. Having obtained an adequate size of the upper arch in a sagittal and transverse direction, the Herbst appliance was applied and anchored superiorly to the hybrid palatal expander to allow mandibular advancement and at the same time avoid excessive retroclination of the upper incisors and distalization of the upper molars, which could lead to an excessive increase in the nasolabial angle during Herbst therapy (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Herbst appliance reinforced with an Hybrid Hyrax Expander and two miniscrews in the lower arch.

Figure 5.

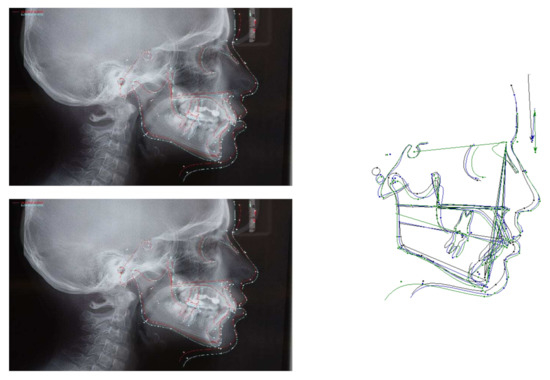

Radiograph post Herbst and cephalometric analysis.

The lower miniscrews were connected by an elastic chain to a vestibular button bonded on 3.3 and 4.3. A retainer was bonded from 3.3 to 4.3.

Once adequate mandibular advancement was obtained, after 9 months, the telescopic components of the Herbst appliance were removed to check if the centric relationship and centric occlusion were in the same position and then the device was removed.

At the next appointment, a fixed multibrackets appliance was applied in upper and lower arches, according to the Bidimensional Technique. Intermaxillary elastics with a diameter of 5/16” and progressively increasing strength from 2 ½ to 6 ½ 0 z were used, to consolidate class II correction and to obtain occlusion finishing.

For the retention protocol, an upper and lower retainer was used with the addition of an Essix in the upper arch.

At the end of the treatment, the conservative reconstruction of element 21 was carried out.

6. Treatment Results

Treatment lasted 26 months. Treatment goals were reached: correction of class II malocclusion was obtained, bilateral molar and canine class I occlusion was achieved, anterior crowding and deep bite were corrected and the smile’s aesthetic was improved.

Treatment started with the objective to obtain expansion in the upper arch using an Hybrid Hyrax Expander with both palatal miniscrew anchorage and first molar bands. The hybrid protocol was selected both to improve skeletal expansion and to avoid the loss of anchorage of the first upper molars during mandibular advancement.

After 20 activations, the Hybrid Hyrax Expander was stabilized and maintained in situ for the next 6 months to promote suture ossification. At this time, it was bonded to the Herbst device. The lower teeth from canine to canine were solidarized with a buccal retainer. Two miniscrews were inserted between the first and second lower premolars and connected with a power chain to the lower canines to avoid lower incisors proclination.

The Herbst device was reinforced by TADs. In the upper arch, two palatal TADs were inserted both to improve skeletal expansion and to avoid molar distalization during jaw advancement. In the lower arch, two TADs were inserted between the first and second premolar and connected to canines with a power chain to avoid lower incisors proclination. Elements from 3.3 to 4.3 were solidarized with steel wire.

Once sagittal discrepancy was solved, after 9 months, treatment continued with a fixed multi-brackets therapy in upper and lower arches with a Bidimensional Technique. Multibrackets treatment objectives were alignment, levelling and occlusion finishing. Intermaxillary elastics were used to complete class II correction to obtain occlusion finishing.

At the end of therapy, a fixed retention was applied to both arches with the addition of an Essix for the upper arch.

The insertion of the lower miniscrews allowed the control of lower incisors proclination. To resolve the lower crowding, avoiding further lower incisors proclination, interproximal reduction was performed.

At the end of treatment, a retainer was applied from 1.2 to 2.2, associated with an essix in the upper arch, and a retainer was applied in the lower arch from 3.4 to 4.4.

Before the placement of retainers, the aesthetic reconstruction of element 21 was carried out and an inlay was placed on element 36.

Total treatment time was 26 months, which was adequate considering the initial malocclusion, sagittal discrepancy and patient’s age.

At the end of treatment no particular root resorption was detected.

After seeing the obtained results, we would again select the same treatment plan today (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 6.

Post-treatment facial and intraoral photographs.

Figure 7.

Post-treatment radiographs and cephalometric analysis.

Figure 8.

Post-treatment models.

Figure 9.

Superimpositions at T0 (start of the treatment) and at T1 (Post-Herbst).

7. Discussion

Skeletally anchored assisting fixed functional appliances such as the Forsus TM Fatigue Resistant Device and the Herbst appliance have been shown to be effective in improving skeletal form [12,13,15,16,17]. Other studies have proposed a four miniscrews approach to further improve the skeletal result of fixed functional appliances [14] with favorable results.

In this case, we described the Herbst treatment with four miniscrews to obtain an im-proved skeletal correction for crowding and overjet with minimum anchorage loss. Conversely to the buccal miniscrew placement as other authors reported, the upper miniscrews were placed in the anterior area of the palate, allowing different advantages: easier insertion, simultaneous use for hybrid expander, lower risks roots lesions, upper teeth free to move; additionally from a biomechanics point of view, this anchorage allowed the following results: reducing upper molar distalization and intrusion effect of the Herbst, reduction of the upper incisor palatal inclination, maxillary expansion with noteworthy skeletal component.

The four miniscrews Herbst treatment finally resulted in a greater skeletal effect and a better control of maxillary and mandibular incisor position and maxillary molar dis-talization (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Biomechanics diagram.

A standard Herbst appliance therapy generally obtained a skeletal correction up to 65% of the class II relationships [18,19,20,21,22,23].

Pancherz described other options to reduce the effect of lower incisors inclinations such the premolar anchorage, premolar-molar anchorage, Pelott anchorage, labial lingual anchorage and class III elastics (150 gr), nevertheless all the systems produced an incisors proclination between 3.1 and 12.1° post Herbst treatment.

Manni et al. evaluated the effectiveness of Herbst treatment with an acrylic splint Herbst appliance adding miniscrews in the lower arch with two types of ligations; they showed that the skeletal anchorage reduced mandibular incisors flaring and the elastic chain increased the orthopedic effect of Herbst treatment. V. Bremen et al. assessed whether mandibular anchorage loss during treatment with Herbst/multibracket (MB) appliances can be prevented, using inter-radicular miniscrew anchorage. They showed that this anchorage did reduce proclination of the lower labial segment to a small extent. The authors found statistically significant differences in anchorage preservation between the study and control groups, even if they were small and were unlikely to be of clinical relevance.

In this case, the lower incisors showed a final proclination of 1.0° after the comprensive therapy; these results are similar to those previously published using skeletal anchorage reinforcement.

The upper incisors were slightly retroclined, avoiding naso-labial angle reduction and simultaneously allowing a crowding solution; these results may be addressed by the Hybrid Expander, which allowed a significant amount of skeletal expansion in the upper arch and consequently a significant arch length increase. Miniscrews in the anterior area of the palate also had a key role on the upper first molars avoiding distal and intrusive movement.

The success of this approach is deeply related to the miniscrew stability, which, in effect, was successful for both arches. The literature reported skeletal anchorage failure in the lower arch between 17.5 and 30% with Herbst-like appliances, with a higher success rate for the palatal insertion site [23,24,25]. The miniscrews success rate could represent a considerable limit, mainly in the lower arch, where the success rate is lower than the palatal area. From a clinical perspective, a lower miniscrew failure could be solved by inserting a new TAD into another position, thus allowing completion of the therapy; nevertheless, this would add more costs and possible patient-related concerns. This approach should also be limited to those patients where the initial lower incisors position is excessively proclined and a noteworthy maxillary expansion is needed.

In this perspective, the palatal approach could be advisable instead of the buccal approach in the upper arch, both to reach a greater miniscrews success rate and to allow more biomechanics for, such as for this case, a hybrid hyrax expansion.

8. Summary and Conclusions

Herbst treatment side effects in class II growing patients, such as lower incisors proclination, upper incisors retroclination, and upper molar distalization, were successfully controlled by the means of two miniscrews in the lower arch and two miniscrews in the anterior area of the palate as anchorage reinforcement.

The anchorage is provided by the upper Hybrid palatal expander and the two lower tads inserted between the first and the second premolars.

Lower incisors control leads to maintenance of overate and to a better mandibular advancement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.; methodology, M.M.; formal analysis, C.C.; data curation, C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M. and C.C.; writing—review and editing, M.M. and C.C.; supervision, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are published in the present report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Proffit, W.R.; Fields, H.W.; Moray, L.J. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in the United States: Estimates from the NHANES-III survey. Int. J. Adult Orthod. Orthognath. Surg. 1998, 13, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Cozza, P.; Baccetti, T.; Franchi, L.; De Toffol, L.; McNamara, J.A., Jr. Mandibular changes produced by functional appliances in Class II malocclusion: A systematic review. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2006, 129, 599.e1–599.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, J.A., Jr.; Brudon, W.L. Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics; Needham Press Inc.: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2001; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, D.I.; Sandler, P.J. The effects of Twin Blocks: A prospective controlled study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1998, 113, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, G.R.; Toruño, J.L.A.; Martins, D.R.; Henriques, J.F.C.; De Freitas, M.R. Class II treatment effects of the Fränkel appliance. Eur. J. Orthod. 2003, 25, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancherz, H. Treatment of Class II malocclusions by jumping the bite with the Herbst appliance: A cephalometric investigation. Am. J. Orthod. 1979, 76, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigal, T.; Dischinger, T.; Martin, C.; Razmus, T.; Gunel, E.; Ngan, P. Stability of Class II treatment with an edgewise crowned Herbst appliance in the early mixed dentition: Skeletal and dental changes. Am. J. Orthod. 2011, 240, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruf, S.; Pancherz, H. Herbst/multibracket appliance treatment of Class II division 1 malocclusions in early and late adulthood. A prospective cephalometric study of consecutively treated subjects. Eur. J. Orthod. 2006, 28, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancherz, H.; Hansen, K. Mandibular anchorage in Herbst treatment. Eur. J. Orthod. 1988, 10, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gönner, U.; Özkan, V.; Jahn, E.; Toll, D.E. Effect of the MARA appliance on the position of the lower anteriors in children, adolescents and adults with Class II malocclusion. J. Orofac. Orthop./Fortschr. Kieferorthopädie 2007, 68, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Servello, D.F.; Fallis, D.W.; Alvetro, L. Analysis of Class II patients, successfully treated with the straight-wire and Forsus appliances, based on cervical vertebral maturation status. Angle Orthod. 2015, 85, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, A.; Pasini, M.; Mazzotta, L.; Mutinelli, S.; Nuzzo, C.; Grassi, F.R. Comparison between an acrylic splint Herbst and an acrylic splint miniscrew-Herbst for mandibular incisors proclination control. Int. J. Dent. 2014, 2014, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, A.; Mutinelli, S.; Pasini, M.; Mazzotta, L.; Cozzani, M. Herbst appliance anchored to miniscrews with 2 types of ligation: Effectiveness in skeletal Class II treatment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2016, 149, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manni, A.; Migliorati, M.; Calzolari, C.; Silvestrini-Biavati, A. Herbst appliance anchored to miniscrews in the upper and lower arches vs standard Herbst: A pilot study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2019, 156, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manni, A.; Mutinelli, S.; Cerruto, C.; Cozzani, M. Influence of incisor position control on the mandibular response in growing patients with skeletal Class II malocclusion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2021, 159, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unal, T.; Celikoglu, M.; Candirli, C. Evaluation of the effects of skeletal anchoraged Forsus FRD using miniplates inserted on mandibular symphysis: A new approach for the treatment of Class II malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 2015, 85, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eissa, O.; El-Shennawy, M.; Gaballah, S.; El-Meehy, G.; El Bialy, T. Treatment outcomes of Class II malocclusion cases treated with miniscrew-anchored Forsus Fatigue Resistant Device: A randomized controlled trial. Angle Orthod. 2017, 87, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremen, J.; Ludwig, B.; Ruf, S. Anchorage loss due to Herbst mechanism-preventable through miniscrews? Eur. J. Orthod. 2015, 37, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomblyn, T.; Rogers, M.; Martin, C.; Tremont, T.; Gunel, E.; Ngan, P. Cephalometric study of Class II Division 1 patients treated with an extended-duration, reinforced, banded Herbst appliance followed by fixed appliances. Am. J. Orthod. 2016, 150, 818–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, N.C.; Gnandt, E.; Ruf, S. Occlusal stability after Herbst treatment of patients with retrognathic and prognathic facial types: A pilot study. Orofac. Orthop. 2016, 77, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souki, B.Q.; Vilefort, P.L.C.; Oliveira, D.D.; Andrade, I., Jr.; Ruellas, A.C.; Yatabe, M.S.; Nguyen, T.; Franchi, L.; McNamara, J.A., Jr.; Cevidanes, L.H.S. Three-dimensional skeletal mandibular changes associated with Herbst appliance treatment. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2017, 20, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laecken, R.; Martin, C.A.; Dischinger, T.; Razmus, T.; Ngan, P. Treatment effects of the edgewise Herbst appliance: A cephalometric and tomographic investigation. Am. J. Orthod. 2006, 130, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzi, C.; Luzi, V.; Melsen, B. Mini-implants and the efficiency of Herbst treatment: A preliminary study. Prog. Orthod. 2013, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Batista, K.B.; Lima, T. Herbst appliance with skeletal anchorage versus dental anchorage in adolescents with Class II malocclusion: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, H.W.; Kang, Y.G.; Jeong, H.J.; Park, Y.G. Palatal temporary skeletal anchorage devices (TSADs): What to know and how to do? Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2021, 24, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).