Featured Application

QSAR model for the determination of gut permeability of 228 pharmacological drugs at different pH conditions.

Abstract

The present study aims at developing a quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) model for the determination of gut permeability of 228 pharmacological drugs at different pH conditions (3, 5, 7.4, 9, intrinsic). As a consequence, five different datasets (according to the diverse permeability shown by the compounds at the different pH values) were handled, with the aim of discriminating compounds as low-permeable or high-permeable. In order to achieve this goal, molecular descriptors for all the investigated compounds were computed and then classification models calculated by means of partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). A high predictive capability was achieved for all models, providing correct classification rates in external validation between 80% and 96%. In order to test whether a reduction in the molecular descriptors would improve predictions and provide information about the most relevant variables, a feature selection approach, covariance selection, was used to select the most relevant subsets of predictors. This led to a slight improvement in the predictive accuracies, and it has indicated that the most relevant descriptors for the discrimination of the investigated compounds into low- and high-permeable were associated with the 2D and 3D structures.

1. Introduction

The gastrointestinal adsorption of oral administered drugs is an essential parameter worth being investigated, as it influences the bioavailability and the effects that several medicines explicate on the body. Furthermore, among the ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion) molecular properties, adsorption drives drug design significantly since bioavailability has proven to be one of the leading causes of drug discard during preclinical and phase I trials [1]. However, studying the permeability of drugs in real systems is a complex process, and not without practical obstacles and ethical problems. In this regard, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines include in vivo, in situ, and in vitro (tissues and cells such as Caco-2 cell) methods to assess drug permeability [2]. In this context, the parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA) [3] has proven to be particularly advantageous in identifying promising candidates in the early stages of drug development, to the extent that it has been included in the Tier I ADME assay at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), together with rat liver microsomal (RLM) stability, and kinetic aqueous solubility [4]. Indeed, PAMPA is an inexpensive and easily reproducible non-cell permeability assay able to model passive transcellular permeation mechanisms, which are predominant in the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, even if PAMPA fails in simulating active and efflux transport, its outcomes correlate well with in vitro Caco-2 cell and in vivo human intestinal absorption, mainly because approximately 90% of Active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) are absorbed via passive diffusion [5].

Studies combining PAMPA and quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) modeling are particularly topical, mainly due to the opportunity to predict gastrointestinal tract (GIT) adsorption and to interpret bioavailability in terms of molecular descriptors directly related to structural characteristics. Consequently, it is understandable how these studies represent a valuable contribution to drug development and risk assessment. Focusing attention on systems designed to simulate gastrointestinal tract absorption, most studies in this field apply regression methods (mainly multiple linear regression or partial least squares) on datasets derived from different PAMPA systems and specific to a certain class of bioactive compounds [6,7,8]. Otherwise, a very recent study concerning PAMPA–QSAR models, used to classify many pharmaceuticals into highly or poorly permeable classes, using random forest and graph convolutional neural networks as classification methods, has been proposed [4].

Surprisingly, most of these papers do not report a systematic study of pH; indeed, among the various parameters that can modify the permeability within the gastrointestinal tract, pH is certainly one of the most important [9,10]. Medicaments can have a different ionic form (and consequently, a different capacity to be absorbed) as the pH varies. This chemical–physical criterion is not constant within the intestine, and it varies from lower (5.6 in the duodenum) to higher values (up to 8.5 in the colon). As a result, since drugs permeate the diverse intestinal tract differently, the entire range of intestinal pH should be tested for a reliable in vivo prediction.

Oja et al. [11] presented a well-designed dataset of acidic, basic, ampholytic, and neutral compounds which were analyzed over an extensive range of pH. This specific work aimed at developing a QSAR model, by applying best multilinear regression, to predict the pH permeability profiles of drug candidates. In addition, they recently reprocessed the dataset mentioned above to classify high- and low-permeable drug substances according to the Biopharmaceutical Classification System framework [2]. Firstly, a logistic regression method was applied to the different datasets, which are the outcomes of the different pH measurements. Then, decision trees were used to analyze the predictions of all the previous models and to assign drug substances into BCS permeability classes. The calculations made by means of decision trees on the theoretical molecular descriptor led to an accuracy of 0.91, indicating the suitability of the proposed approach.

Based on these considerations, the present work considers a sub-set of molecules reported in the public database produced by Oja et al., to apply an alternative classification approach based on the use of a linear model, namely, partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). Moreover, with respect to the original study by Oja et al. [2], where only 1D and 2D descriptors were considered, together with hydrophobicity descriptors, here, a wider range of molecular descriptors (from 0D to 3D) was calculated. Although the results are not directly comparable, as different validation methods were chosen, the presented approach turns out to be a simple, reliable, and easily interpretable method to distinguish and classify different classes of compounds in terms of their permeability characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

The investigated data were a sub-set of those described in [2]. Two hundred and twenty-eight different compounds of pharmaceutical interest have been taken into consideration (a complete list of them is reported in Table 1). The GIT permeability of the molecules at four different pH conditions (pH = 3, 5, 7.4, and 9) was assessed by parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA), as described in [2,11]. The molecules’ structures (as SMILES files) and their permeability capability were downloaded from the QSAR Data Bank repository [12], where the authors made the data available [2,13].

Table 1.

List of the 228 investigated compounds.

Given the heterogeneous nature of the analyzed compounds, their permeating capability changes as the pH varies. According to the literature [11], the inspected molecules were labelled as high-permeable (logPe ≥ −6.2) or low-permeable (logPe < 6.2). This collection of empirical data led to the organization of four different datasets, one for each pH level. Eventually, a last set of information was obtained by evaluating the intrinsic permeability (IP) of the compounds [2], leading to a total of five diverse datasets.

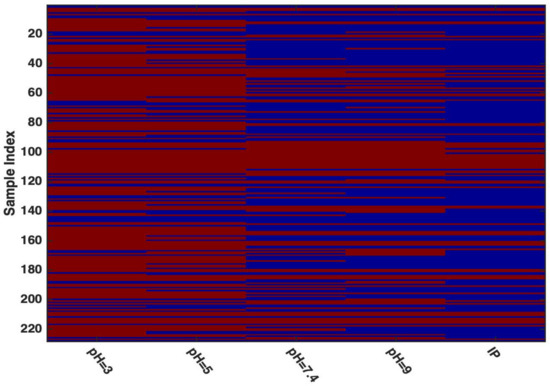

The distribution of the molecules into the two classes according to the diverse pH levels, together with IP-based outcome, is shown in Figure 1. In the plot, red and blue bars represent low- and high-permeability, respectively. As expected, (and in agreement with the literature), a general increase in permeability can be observed as the pH moves to higher values.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the molecules into the two classes according to the different pHs, together with IP-based outcome. Legend: red—low permeability; blue—high permeability.

2.1. Molecular Descriptors

Molecular structures were optimized using the MacroModel 7.1 molecular modelling program package [14].

The MM2 force field was used to search the global energy minimum of each molecule. Molecular descriptors were calculated with Dragon Software 6.0 [15].

The total number of descriptors obtained was 4885, classified as zero- (0D), one- (1D), two- (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) descriptors, depending on whether they are estimated from the chemical formula, the substructure list representation, the graph, or the geometrical representation of the molecule, respectively. Constant and highly correlated variables (r > 0.95) were removed, and a total of 1499 molecular descriptors were retained and used for the analysis.

2.2. Chemometric Modelling

Classification models relating the molecular descriptors to the GIT permeability at the different pH were built using partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) [16,17].

This technique represents a generalization of the PLS regression algorithm [18] to discrimination problems and allows the calculation of reliable and stable classification models in the presence of a high number of (even highly correlated) descriptors, when more traditional approaches, such as linear discriminant analysis (LDA [19]), would not be applicable due to ill-conditioning issues hindering the invertibility of the within-class variance/covariance matrix.

However, by transforming a classification problem into a regression one, PLS-DA exploits all the advantages of the PLS algorithm to deal with such ill-conditioning through bilinear modeling. This possibility is mediated by the introduction of a (binary) dummy response y that encodes the class membership of the molecules. In particular, in the present study, such a dependent variable is given the value of one if the molecule has high permeability, and zero if it has low permeability. A regression model is then built to relate the matrix of molecular descriptors X and the dummy response y by means of the PLS algorithm, according to:

where b is the vector of regression coefficients.

y = Xb

PLS can deal with ill-conditioned descriptor matrices since it operates by projecting the data onto a relevant low-dimensional subspace of orthogonal component scores (T) having maximum covariance with the response:

with R being the projection weights. The scores are then the actual predictors for the response:

through the set of coefficients q (inner relation), so that Equation (1) is in fact the result of the combination of the relations in (2) and (3), with:

T = XR

y = Tq

b = Rq

Once the model is built on the training data, the regression coefficients b can be used to predict the response for new molecules new, based on the value of their molecular descriptors Xnew:

However, differently from their target counterparts, the predicted values of the response will not be binary but real-valued; therefore, there is the need of defining a classification criterion to predict the class-membership of the molecules based on the values of new. In the case of a two-class problem, such as the one addressed in the present paper, this translates to identifying a threshold value threshold for the predicted response, so that if new > threshold the molecule is predicted as high-permeable, whereas if new < threshold its permeability is predicted to be low. To establish such a threshold value, different strategies have been proposed in the literature. In the present study, the probabilistic approach suggested by Perez et al. [20] has been applied.

3. Results and Discussion

As described above, a total of five different datasets were available, four associated with different pH conditions (3, 5, 7.4 and 9) and one with the IP.

Each distinctive dataset was individually processed; consequently, five different classification models have been developed. In order to perform the external validation of the models, prior to their creation, each dataset was divided into a training and a test set. It is trivial that, given the different distribution of the samples in the two classes as the pH varies, the training and the test sets of the different models do not correspond.

In order to ensure the representativeness of the populations of the two sub-sets, the molecules were split into calibration and validation sets by the Duplex algorithm [21].

A summary diagram of the distribution of the samples into the two classes at the different pH levels is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of the samples into the two classes at the different pH levels for the training and the test set.

As mentioned above, five different PLS-DA models were calculated, one per each auto-scaled dataset. In particular, the training data were used to build the corresponding classification models, the optimal complexity of which (in terms of number of latent variables (LVs)) was defined as the one leading to the lowest classification error (%CECV) in a five-fold cross-validation procedure.

For each dataset, once the classification model was built on the training set with the selected optimal complexity, it was then applied to the test set to be validated. The overall accuracy and the correct classification rate (CCR%) for each category are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

PLS-DA: number of latent variables (LVs), overall accuracy and correct classification rate (CCR%) for the individual categories on the training set (in calibration, and cross-validation (CV)) and the test set (prediction).

As can be observed, from the prediction point of view, there is a general improvement with the increase in the pH. This is probably due to a higher stability of the system, and a greater balance of compounds between the classes.

In agreement with this observation, it can be noticed that the less accurate model, i.e., the one that led to the lowest CCR, is built on the data collected at pH 3; however, this provided a completely acceptable result, successfully predicting the permeability category of 83% of all the test samples, completely in agreement with the individual classification models discussed by Oja et al., whose predictive accuracies ranged between 81% and 88%.

However, the highest accuracy was provided by the model built on the IP dataset, which achieved an overall correct classification rate of ~93% on the external test set.

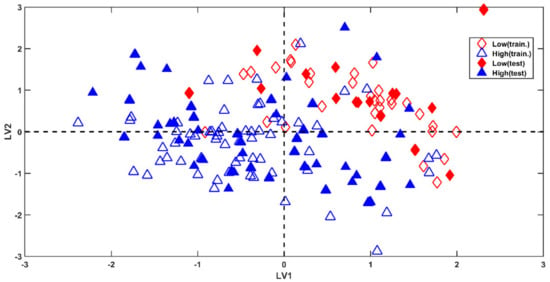

A graphical representation of the results can be seen in Figure 2, where calibration (empty symbols) and validation molecules (filled symbols) have been projected onto the space spanned by the first two latent variables (LVs). From the plot, it is possible to notice a clear grouping tendency among observations belonging to the two classes. In particular, the greatest part of the compounds presenting low permeability (red diamonds) falls at the positive values of both LV1 and LV2; however, high-permeating molecules (blue triangles) spread along LV1, but mainly present negative scores for LV2. This representation does not completely reflect the accuracy of the achieved results (a total accuracy of 93.33%), which corresponds to the misclassification of only five test samples (over 75), all belonging to class high-permeable. Nevertheless, this is due to the fact that the displayed scores plot provides a substandard representation of the results, because it takes into account only the variability modelled by two (over eleven) components.

Figure 2.

PLS-DA: model on the IP-based categorization. Projection of the training and test molecules onto the first two latent variables.

Eventually, in order to investigate which molecular descriptors contribute the most to the prediction of the permeability characteristics of the investigated molecules, and, at the same time, to verify whether retaining only the most relevant predictors could improve the classification models, a variable selection strategy based on the covariance selection (CovSel) algorithm [22] was adopted. In particular, for each dataset, models including an increasing number of descriptors (selected by CovSel, up to a maximum of 50) were built and cross-validated (using five cancelation groups). Eventually, the number of variables (nVar) leading to the lowest classification error in cross-validation was selected, and the optimal one and the corresponding descriptors were used to build the final PLS-DA classification model, which was then validated on the test molecules. In all cases, the selected descriptors can be considered as the ones being more relevant in determining the discrimination between high- and low-permeable substances, providing the basis for a molecular interpretation of the permeation process.

The number of selected molecular descriptors and the classification results of the PLS-DA models built on the reduced sets of variables (both in cross-validation on the training data and in prediction on the external test sets) are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

PLS-DA of the five investigated datasets after variable selection by CovSel: Number of selected descriptors (nVar), number of latent variables (LVs), overall accuracy and correct classification rate (CCR%) on the training data in cross-validation (CV) and on the test set in prediction.

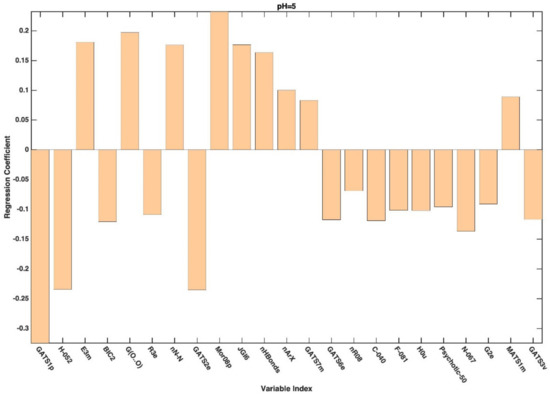

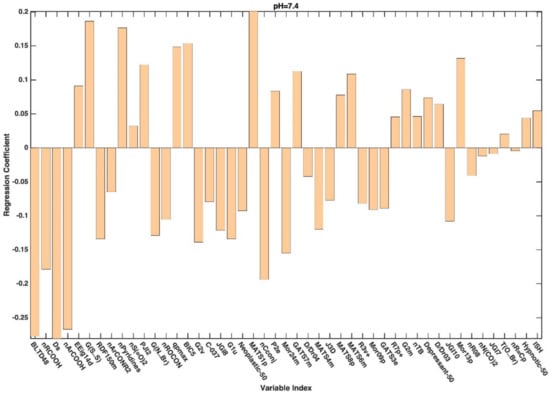

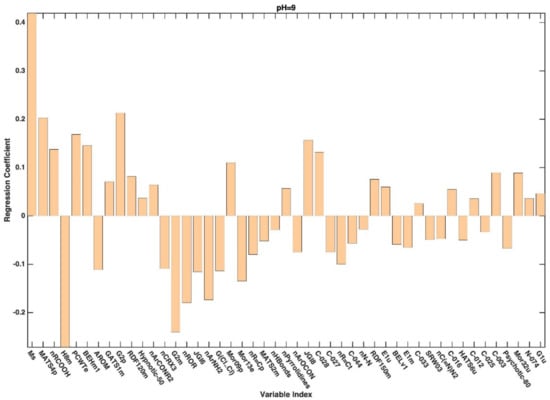

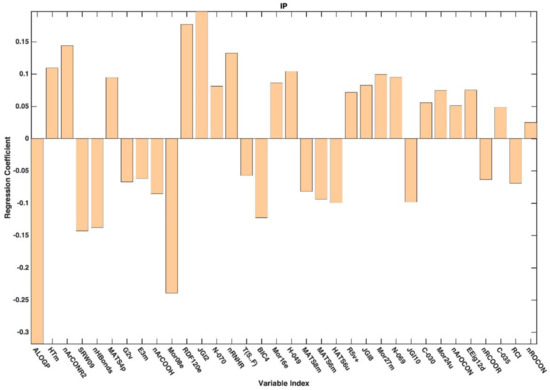

In general, variable selection of the variables has led to an improvement from the point of view of prediction. Indeed, except for the model built on the dataset associated with pH 3, the predictive accuracy of all the PLS-DA models built on the selected variables was higher than that obtained on the full set of descriptors (Table 3). Looking at the table, it is also possible to observe how (and in the case of the reduced datasets) the prediction accuracy of the PLS-DA models follows the same trend with respect to the increase in pH as already registered for the full set of descriptors, whereas models predicting the categorization observed at higher pH appear to be more accurate. When moving to the interpretation of the PLS-DA models, further support is provided by the inspection of the regression coefficients associated with the selected molecular descriptors, which are graphically represented in Appendix A. When looking at the selected variables and at the values of the associated coefficients, it can be affirmed that, irrespectively of the pH at which the permeability is measured/defined, the most significant molecular descriptors for classification purposes are those associated with 2D and 3D structures (see Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3, Figure A4 and Figure A5 for more details).

4. Conclusions

The aim of the present work was to develop a QSAR model suitable for the classification of 228 pharmaceutical drugs according to their GIT permeability at different pH levels. The starting point of this study was a previous paper published by Oja et al., where the same aim was achieved by logistic regression followed by decision trees. The present research represents an equally efficient solution for the same purpose, requiring a less substantial computational effort. In general, the predictive capability obtained is equal to or greater than that achieved by Oja et al. Furthermore, the application of a variable selection method has allowed highlighting which molecular descriptors are the most relevant for the classification of compounds. In particular, this further step has indicated that the predictors associated with the 2D and 3D structures of the investigated compounds are the most significative features for discriminating drugs into low- and high-permeable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and F.M.; methodology, A.B. and F.M.; software, A.B. and F.M.; validation, A.B. and F.M.; formal analysis, L.M. and F.M.; investigation, A.B. and L.M.; resources, F.M.; data curation, L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B. and M.F.; writing—review and editing, A.B., M.F. and F.M.; visualization, A.B. and M.F.; supervision, F.M.; project administration, F.M.; funding acquisition, F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available at QsarDB repository, reference number [13].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Additional figures and table reporting details about the selected descriptors.

Figure A1.

Regression coefficients associated to the descriptors selected by CovSel for the PLS-DA model based on the reduced dataset collected at pH 3.

Figure A2.

Regression coefficients associated to the descriptors selected by CovSel for the PLS-DA model based on the reduced dataset collected at pH 5.

Figure A3.

Regression coefficients associated to the descriptors selected by CovSel for the PLS-DA model based on the reduced dataset collected at pH 7.4.

Figure A4.

Regression coefficients associated to the descriptors selected by CovSel for the PLS-DA model based on the reduced dataset collected at pH 9.

Figure A5.

Regression coefficients associated to the descriptors selected by CovSel for the PLS-DA model based on the IP-based dataset.

Table A1.

Comprehensive list of the descriptors selected in the final models.

Table A1.

Comprehensive list of the descriptors selected in the final models.

| Descriptor | Block | |

|---|---|---|

| ALOGP | Molecular properties | Other |

| AROM | Geometrical descriptors | 3D |

| BEHm1 | Burden eigenvalues | 2D |

| BELv1 | Burden eigenvalues | 2D |

| BIC2 | Information indices | 2D |

| BIC4 | Information indices | 2D |

| BIC5 | Information indices | 2D |

| BLTD48 | Molecular properties | Other |

| C-003 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| C-012 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| C-016 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| C-025 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| C-027 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| C-028 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| C-030 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| C-033 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| C-035 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| C-037 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| C-040 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| C-044 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| D/Dr03 | Ring descriptors | 2D |

| D/Dr04 | Ring descriptors | 2D |

| Depressant-50 | Drug-like indices | Other |

| Ds | WHIM descriptors | 3D |

| E1m | WHIM descriptors | 3D |

| E1u | WHIM descriptors | 3D |

| E3m | WHIM descriptors | 3D |

| EEig12d | Edge adjacency indices | 2D |

| EEig14d | Edge adjacency indices | 2D |

| F-081 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| G(Cl…Cl) | 3D atom pairs | 3D |

| G(N—Br) | 3D atom pairs | 3D |

| G(O…O) | 3D atom pairs | 3D |

| G(S…S) | 3D atom pairs | 3D |

| G1u | WHIM descriptors | 3D |

| G2e | WHIM descriptors | 3D |

| G2m | WHIM descriptors | 3D |

| G2p | WHIM descriptors | 3D |

| G2v | WHIM descriptors | 3D |

| GATS1m | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| GATS1v | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| GATS3e | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| GATS3v | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| GATS6e | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| GATS7m | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| GETS2e | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| GVWAI-50 | Drug-like indices | Other |

| H-049 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| H-052 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| H0u | GETAWAY descriptors | 3D |

| H8m | GETAWAY descriptors | 3D |

| HATS6u | GETAWAY descriptors | 3D |

| HATS7u | GETAWAY descriptors | 3D |

| HTm | GETAWAY descriptors | 3D |

| Hypnotic-50 | Drug-like indices | Other |

| ISH | GETAWAY descriptors | 3D |

| J3D | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| JGI10 | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| JGI2 | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| JGI6 | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| JGI7 | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| JGI8 | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| MAT1p | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| MATS1m | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| MATS2m | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| MATS4m | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| MATS4p | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| MATS6m | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| MATS7u | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| MATS8m | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| MATS8p | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| MATS8v | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| Mor08e | 3D-MoRSE descriptors | 3D |

| Mor08p | 3D-MoRSE descriptors | 3D |

| Mor09p | 3D-MoRSE descriptors | 3D |

| Mor09p | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| Mor11p | 3D-MoRSE descriptors | 3D |

| Mor13e | 3D-MoRSE descriptors | 1D |

| Mor13p | 3D-MoRSE descriptors | 3D |

| Mor16e | 3D-MoRSE descriptors | 3D |

| Mor24m | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| Mor24u | 2D autocorrelations | 2D |

| Mor26u | 3D-MoRSE descriptors | 3D |

| Mor27m | 3D-MoRSE descriptors | 3D |

| Mor28m | 3D-MoRSE descriptors | 3D |

| Mor32u | 3D-MoRSE descriptors | 3D |

| Ms | Topological descriptors | 2D |

| N-067 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| N-069 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| N-070 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| N-074 | Atom-centered fragments | 1D |

| nArC=N | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nArCN | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nArCONR2 | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nArCOOH | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nArCOOR | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nArNH2 | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nArOCON | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nArOH | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nArX | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nC(=N)N2 | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nC=N-N< | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nCconj | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nCONN | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nCRX3 | Functional group counts | 1D |

| Neoplastic-50 | Drug-like indices | Other |

| Neoplastic-80 | Drug-like indices | Other |

| nHBonds | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nHDON | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nlsoxazoles | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nN(CO)2 | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nN-N | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nOxolanes | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nPyrazines | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nPyridines | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nR=Cp | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nR=Ct | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nR08 | Ring descriptors | 2D |

| nR08 | Ring descriptors | 2D |

| nRNHR | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nRNR2 | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nROCON | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nROR | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nS(=O)2 | Functional group counts | 1D |

| nTB | Constitutional indices | 0D |

| P2e | WHIM descriptors | 3D |

| PCWTe | Charge descriptors | Other |

| PJI2 | Topological indices | 2D |

| Psicotic-80 | Drug-like indices | Other |

| Psychotic-50 | Drug-like indices | Other |

| PW3 | Topological indices | 2D |

| qpmax | Charge descriptors | Other |

| R3e | GETAWAY descriptors | 3D |

| R3v+ | GETAWAY descriptors | 3D |

| R5v+ | GETAWAY descriptors | 3D |

| R7p+ | GETAWAY descriptors | 3D |

| RCI | Ring descriptors | 2D |

| RDF090p | RDF descriptors | 3D |

| RDF120e | RDF descriptors | 3D |

| RDF120m | RDF descriptors | 3D |

| RDF150m | RDF descriptors | 3D |

| RDF155m | RDF descriptors | 3D |

| SRW03 | Walk and path counts | 2D |

| SRW09 | Walk and path counts | 2D |

| T(O…Br) | 2D atomic pairs | 2D |

| T(O…O) | 2D atom pairs | 2D |

| T(S…F) | 2D atom pairs | 2D |

References

- Waring, M.J.; Arrowsmith, J.; Leach, A.R.; Leeson, P.D.; Mandrell, S.; Owen, R.M.; Pairaudeau, G.; Pennie, W.D.; Pickett, S.D.; Wang, J.; et al. An analysis of the attrition of drug candidates from four major pharmaceutical companies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oja, M.; Sild, S.; Maran, U. Logistic Classification Models for pH-Permeability Profile: Predicting Permeability Classes for the Biopharmaceutical Classification System. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 2442–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kansy, M.; Senner, F.; Gubernator, K. Physicochemical High Throughput Screening: Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeation Assay in the Description of Passive Absorption Processes. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 1007–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siramshetty, V.; Williams, J.; Nguyễn, Ð.T.; Neyra, J.; Southall, N.; Mathé, E.; Xu, X.; Shah, P. Validating ADME QSAR Models Using Marketed Drugs. SLAS Discov. 2021, 26, 1326–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diukendjieva, A.; Tsakovska, I.; Alov, P.; Pencheva, T.; Pajeva, I.; Worth, A.P.; Madden, J.C.; Cronin, M.T.D. Advances in the prediction of gastrointestinal absorption: Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modelling of PAMPA permeability. Comput. Toxicol. 2019, 10, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chi, C.T.; Lee, M.H.; Weng, C.F.; Leong, M.K. In silico prediction of PAMPA effective permeability using a two-QSAR approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diukendjieva, A.; Alov, P.; Tsakovska, I.; Pencheva, T.; Richarz, A.; Kren, V.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Pajeva, I. In vitro and in silico studies of the membrane permeability of natural flavonoids from Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. and their derivatives. Phytomedicine 2019, 53, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savić, J.; Dobričić, V.; Nikolic, K.; Vladimirov, S.; Dilber, S.; Brborić, J. In vitro prediction of gastrointestinal absorption of novel β-hydroxy-β-arylalkanoic acids using PAMPA technique. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 100, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSesso, J.M.; Jacobson, C.F. Anatomical and physiological parameters affecting gastrointestinal absorption in humans and rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2001, 39, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charman, W.N.; Porter, C.J.H.; Mithani, S.; Dressman, J.B. Physicochemical and Physiological Mechanisms for the Effects of Food on Drug Absorption: The Role of Lipids and pH. J. Pharm. Sci. 1997, 86, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oja, M.; Maran, U. pH-permeability profiles for drug substances: Experimental detection, comparison with human intestinal absorption and modelling. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 123, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruusmann, V.; Sild, S.; Maran, U. QSAR DataBank repository: Open and linked qualitative and quantitative structure–activity relationship models. J. Cheminform. 2015, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oja, M.; Sild, S.; Maran, U. Data for: Logistic Classification Models for pH-Permeability Profile: Predicting Permeability Classes for the Biopharmaceutical Classification System. QsarDB Repos. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadi, F.; Richards, N.G.J.; Guida, W.C.; Liskamp, R.; Lipton, M.; Caufield, C.; Chang, G.; Hendrickson, T.; Still, W.C. Macromodel—An integrated software system for modeling organic and bioorganic molecules using molecular mechanics. J. Comput. Chem. 1990, 11, 440–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talete, S.r.l. DRAGON 6.0 for Windows (Software for Molecular Descriptor Calculations); Talete S.r.l.: Milan, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström, M.; Wold, S.; Söderström, B. PLS Discriminant Plots. In Pattern Recognition in Practice; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ståhle, L.; Wold, S. Partial least squares analysis with cross-validation for the two-class problem: A Monte Carlo study. J. Chemom. 1987, 1, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, S.; Martens, H.; Wold, H. The Multivariate Calibration Problem in Chemistry Solved by the PLS Method. In Matrix Pencils; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Kågström, B., Ruhe, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1983; Volume 973. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.A. The use of multiple measurements in taxonomic problems. Ann. Eugen. 1936, 7, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, N.F.; Ferré, J.; Boqué, R. Calculation of the reliability of classification in discriminant partial least-squares binary classification. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2009, 95, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snee, R.D. Validation of Regression Models: Methods and Examples. Technometrics 1977, 19, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, J.M.; Palagos, B.; Bertrand, D.; Fernandez-Ahumada, E. CovSel: Variable selection for highly multivariate and multi-response calibration: Application to IR spectroscopy. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2011, 106, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).