Abstract

This paper is devoted to a novel autonomous navigation method for spacecraft around the Sun–Earth L2 point. In contrast to the previous navigation methods, which rely on ground-based or inter-spacecraft measurements, the proposed method determines the orbit based on Earth-shadow measurements. First, the navigation framework using the Earth-shadow measurement is proposed. Second, the geometric analysis is used to derive the mathematical model of the Earth-shadow measurements. Then, the fifth-degree Cubature Kalman filter (CKF) is designed to estimate the states of the spacecraft. Numerical simulations are implemented to validate the performance of the proposed navigation method. Finally, the simulation results show that the navigation system is observable and that the proposed method could be potentially useful for an autonomous navigation mission near the Sun–Earth L2 point in the future.

1. Introduction

Recently, usage of the periodic orbits around the Lagrange points has attracted great attention, and many missions have been carried out or planned, such as the Chang’e-4 and the Deep Space Gateway [1,2]. One of the important issues in these missions is to accurately determine the orbit of the spacecraft. The knowledge of the spacecraft state is essential for substantial guidance and control, and can be potentially useful for some scientific purposes, such as gravitational wave detection and gravitational field recovery [3,4]. Thus, it is necessary to investigate the navigation problem of the spacecraft in three-body dynamics.

The typical space mission, ISEE-3, runs around the Sun–Earth L1 point with the Halo orbit. The precision of this navigation method is about 4 to 8 km during the two circles’ orbit calculation [5]. The navigation accuracy of CE-2 depending on the unified S-band measurement and very long baseline interferometry measurement can reach 2 km by using overlap analysis [6]. The typical accuracies of orbit determination methods are on the order of several hundred meters in position and several mm/s in velocity with 5–7 days tracking data. The European Space Agency (ESA) ground stations are designed and built to comply with the carrier stability requirements as defined in the ECSS-E-50-02A Ranging and Doppler tracking standard, which shows that the measurement precision of the Doppler tracking is in the magnitude of 0.1 mm/s, whilst for distance it is 1 m. The Radioscience Bepi-Colombo MORE experiment used Ka band radio links to make accurate measurements of the spacecraft range and range rate. Tropospheric zenith wet delays range from 1.5 cm to 10 cm, and the high variability impairs the accuracy of these measurements [7,8]. The combination of very long baseline interferometry data with range or Doppler data can improve the orbit accuracy in the L2 region compared with the range or Doppler data only. The technique and analysis method used can provide the foundation for future Earth–Moon libration point spacecraft missions, including the CE-4 relay satellite in the L2 region [9].

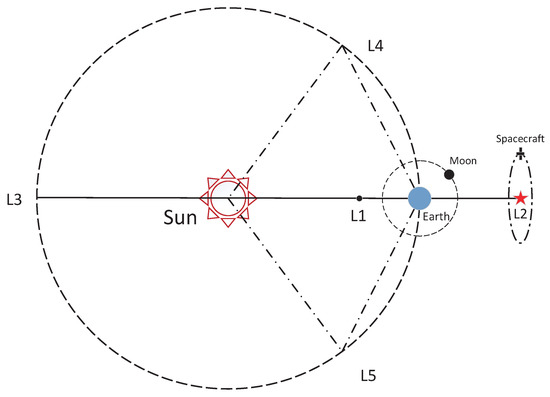

Nowadays, collinear Lagrange points of the restricted three-body problem are receiving increasing attention because of their special dynamical properties and unique geometrical positions [10,11,12]. There are five Lagrange points in the Sun–Earth three-body system. This study focuses on navigation around the Lagrange point L2. Because orbital motion near the Lagrange point L2 is extremely sensitive to the initial value, the small error will be quickly amplified. The spacecraft needs to conduct orbital maneuvers frequently, otherwise, it will deviate from the target area soon. Therefore, the navigation needs to meet high-precision requirements [13,14,15]. Vasile et al. [16] proposed an autonomous navigation method for deep space spacecraft, designed for measuring the attitude and azimuth of celestial bodies. This method is to determine the spacecraft state using the optical measurement data processed with the least-square-degree Kalman filter algorithm.

Focusing on the spacecraft navigation technology, Yim et al. [17] conducted a study about the observability of relative navigation in two-body dynamics by line-of-sight measurement under the influence of J2 perturbation. The results show that the performance of the navigation system can be improved by selecting the orbital parameters properly. Chen et al. [18] investigated the navigation method using space-based angle measurement data. This method calculates the orbital parameters by the Direct Method or Newton method based on the initial value and proves that the spacecraft orbit can be determined by the space-based angle measurement data. Zhang et al. [19] considered the relative motion and estimated the parameters of noncooperative targets from the perspective of the nonlinearly constrained optimization problem. The author also proposed a monocular vision method and verified its effectiveness through numerical simulation. Liu [20] took the space-based monitoring system as the research background and analyzed the space-based detectability of noncooperative targets. The author also improved the filtering algorithms and key technologies for initial navigation and combined navigation of space-based noncooperative targets, which are based on the angle measurement information. Lu [21] discussed the autonomous optical navigation technology of the deep space spacecraft, designed the image processing algorithm and information extraction algorithm, and analyzed the observability of the system by the numerical analysis method. The method of determining the relative orbit of two spacecraft by measuring their relative distance is commonly used. Although a great deal of the distance measurement method was put forward earlier, it is difficult to achieve high-precision requirements in a complex space environment. Moreover, while the relative navigation between the objective spacecraft and the observation spacecraft can be achieved by the other measurement information, the absolute navigation is hard to achieve [22,23,24].

Chen et al. [25] proposed an autonomous navigation method for spacecraft based on intersatellite ranging and orbit orientation parameter constraints. This method assumes that the coordinates connected to the Earth and the absolute orientation of the constellation in inertial space cannot be established solely through inter-satellite ranging. Thus, its orbit must be determined by combining dynamic equations and prediction information [26,27,28]. Tang [29] studied the inter-satellite distance measurement technology in the static and dynamic environment, discussed the autonomous navigation technology based on the intersatellite distance measurement, and proposed a ranging technology that can gradually improve the precision in a static environment. The study also proved that the high-precision distance between spacecraft could not be obtained only through inter-satellite distance measurement [30,31,32].

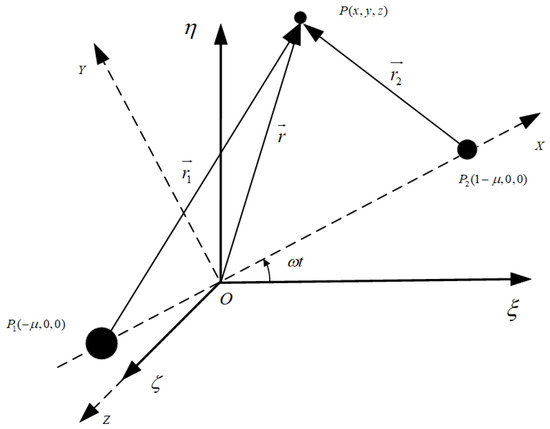

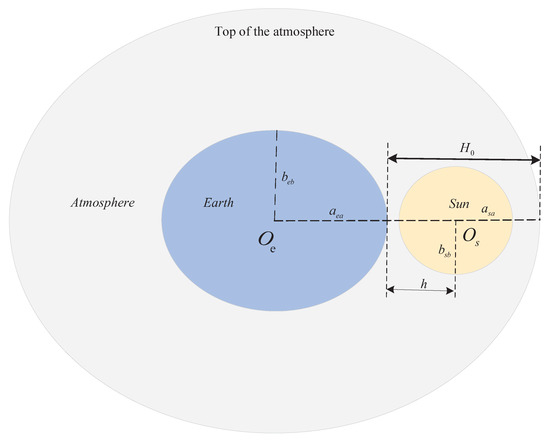

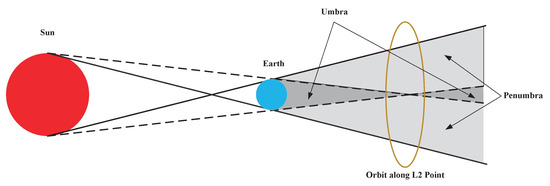

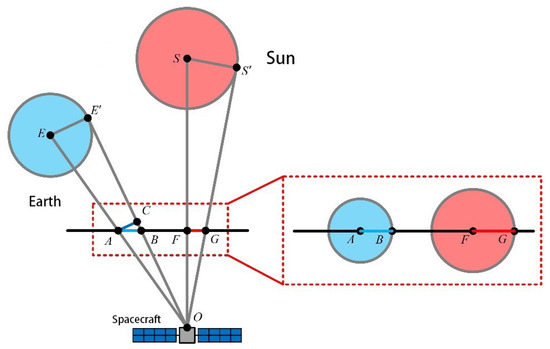

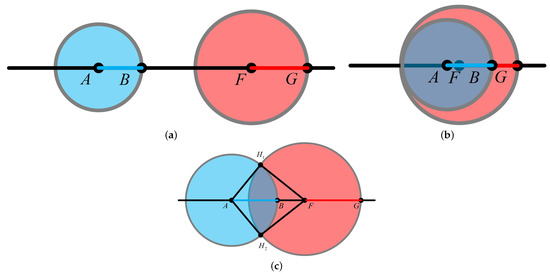

Based on the related Earth-shadow researches [33,34], we focus on the autonomous navigation at the Sun–Earth L2 point. The difficulty of navigation around the Sun–Earth L2 point is that there are few observations available for navigation [35,36,37]. This paper studies the autonomous navigation method based on the Earth-shadow observation near the Sun–Earth L2 point. This method determines the position and velocity of the spacecraft by measuring the proportion that the Sun is blocked by the Earth. In Section 2, we build the dynamic model and establish the measurement model of the Earth-shadow. Then, we derive the expression of the measurement function from three different observation scenarios. In Section 3, we apply the fifth-degree cubature Kalman filter algorithm to simulate the different models with an amplitude of 5000 km along the X direction. In Section 4, we obtain the simulation results of navigation and provide the analysis of the simulation results. Finally, the conclusions are given in Section 5.

4. Simulation Analysis

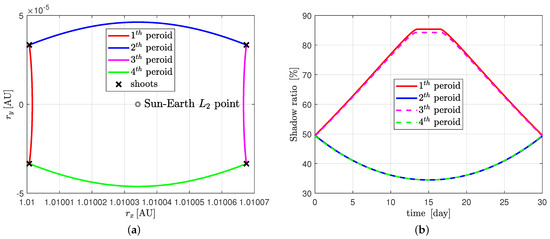

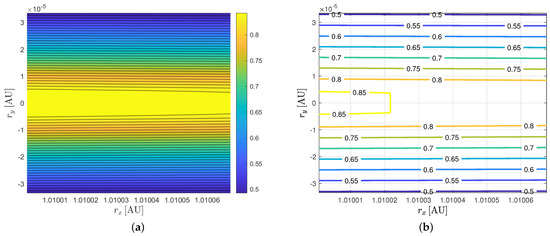

In the rotating coordinate system, the controlled periodic orbit is located in the X-Y plane. The amplitude of the periodic orbit along the X direction is 5000 km, and the orbit is composed of four uncontrolled orbital segments in one cycle. The initial parameters and the time of the uncontrolled orbits are shown in Table 1. The reference trajectory is shown in Figure 7, together with the measurement curve. It can be seen that the shadow ratio varies from approximately to . Figure 8 shows the contour distribution of the measurement function near the nominal track.

Table 1.

Nominal trajectory parameters.

Figure 7.

Nominal trajectory and its measurement parameters. (a) Nominal trajectory. (b) Measurement curve.

Figure 8.

Contour lines of measurements near the nominal track. (a) Outline of the nominal track. (b) Contour map of the nominal track.

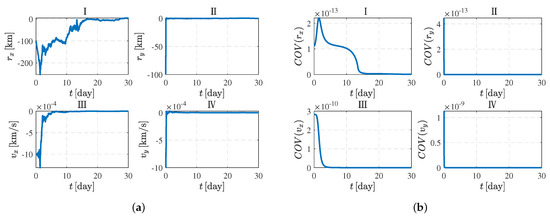

It can be seen that orbital period and orbital period are symmetrical and the orbital period and orbital period are symmetrical. Therefore, the orbital period and orbital period are considered and analyzed below. Firstly, for the orbital period, the simulation is performed by using CKF, where the initial position error is 100 km, the initial speed error is 1 m/s, and the measurement error is 0.001. The simulation results are shown in Figure 9, which, respectively, shows the navigation error and covariance convergence curve. As shown in Figure 9b, the error converges about 15 days later, and the convergence speed of the Y-axis state is faster than that of the X-axis.

Figure 9.

Navigation error results and covariance convergence curve. (a) Navigation error. (b) Covariance convergence curve.

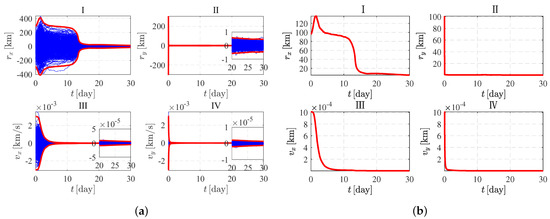

Figure 10a shows the 500 times shooting results of the Monte Carlo simulation, in which the accuracy along the X direction is poor and the convergence speed is slow. However, it can be seen that the accuracy in the Y direction is high and the convergence speed is fast. As shown in Table 2, the standard deviation of position error along the X direction is about 4.8581 km and the standard deviation of velocity error is 0.002 m/s. The standard deviation of position error along the Y direction is about 0.1518 km, and the standard deviation of velocity error is 0.0004 m/s.

Figure 10.

Results of the Monte Carlo simulation of the orbital period. (a) 500 times shooting results. (b) 3-sigma curve.

Table 2.

Analysis of the 3-sigma curve of the orbital period.

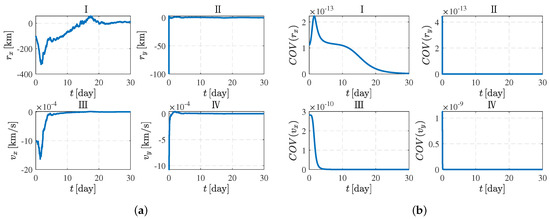

For the orbital period, the initial position error is 100 km, the initial speed error is 1 m/s, and the measurement error is 0.001. The simulation results are shown in Figure 11, which, respectively, show the navigation error and covariance convergence curve. As shown in Figure 11b, the error converges about 25 days later, and the convergence speed along the Y direction is still faster than along the X direction.

Figure 11.

Navigation error results and covariance convergence curve. (a) Navigation error. (b) Covariance convergence curve.

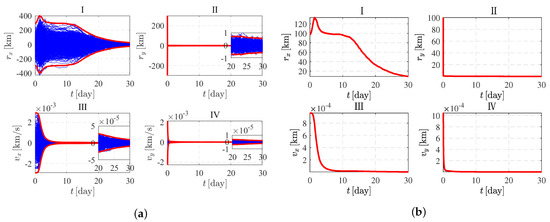

Figure 12a shows the 500 times shooting results of the Monte Carlo simulation, in which the accuracy along the X direction is poor and the convergence speed is slow. However, it is apparent that the accuracy along the Y direction is high and the convergence speed is fast. As shown in Table 3, the standard deviation of position error along the X direction is about 8.7276 km and the standard deviation of velocity error is 0.003 m/s. The standard deviation of position error along the Y direction is about 0.1877 km and the standard deviation of velocity error is 0.001 m/s.

Figure 12.

Results of the Monte Carlo simulation of the orbital period. (a) 500 times shooting results. (b) 3-sigma curve.

Table 3.

Analysis of the 3-sigma curve of the orbital period.

5. Conclusions

Aiming at the small-scale orbit near the Sun–Earth L2 point, this paper studied the navigation method based on the Earth-shadow measurement. The paper also considered effects such as the atmosphere and oblateness of the Earth and the Sun in spacecraft autonomous navigation. This method takes the proportion of the Sun blocked by the Earth as the measurement function and calculates the position and velocity of the spacecraft through the continuous change in the measurement function H. For the orbital period, the position error along the X direction is about 4.8581 km and the velocity error is 0.002 m/s. The position error along the Y direction is about 0.1518 km and the velocity error is 0.0004 m/s. For the orbital period, the position error along the X direction is about 8.7276 km and the velocity error is 0.003 m/s. The position error along the Y direction is about 0.1877 km and the velocity error is 0.001 m/s. The above simulation results indicate that the characteristics of convergence and observability along the Y axis are good. Furthermore, this method makes some contribution to the difficulty that the Sun–Earth L2 point has few observations available for navigation and improves the accuracy for autonomous navigation. The autonomous navigation method using satellite-borne equipment has wide application prospects in gravitational wave detection, asteroid exploration, and other deep space exploration fields. Based on this work, the method of autonomous navigation and filtering algorithm could be further conducted in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W.; methodology, Q.L.; software, T.Q. and C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12202048; Grant No. 12102441), and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (Grant No. 2020295). This research was also funded by The National Key RD Program of China (Grant number 2020YFC2201200).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, C.; Zuo, W.; Wen, W.; Zeng, X.; Gao, X.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Su, Y.; Ren, X.; et al. Overview of the Chang’e-4 mission: Opening the frontier of scientific exploration of the lunar far side. Space Sci. Rev. 2021, 217, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniakiewicz, P.J.; Bridges, J.; Burchell, M.J.; Carey, W.; Carpenter, J.; Della Corte, V.; Dignam, A.; Genge, M.J.; Hicks, L.; Hilchenbach, M.; et al. A cosmic dust detection suite for the deep space Gateway. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 68, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Qin, T.; Zhu, S.; Liu, Y.; Xu, R.; Yu, Z. Trajectory curvature guidance for Mars landings in hazardous terrains. Automatica 2018, 93, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Zhu, S.; Cui, P.; Luan, E. Divert capability analysis and subsequent guidance design for mars landing. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MN, USA, 4–11 March 2018; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman, M. Orbit determination issues for libration point orbits. In Libration Point Orbits and Applications; World Scientific: Singapore, 2003; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Hu, S.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L. Orbit determination and analysis for chang’E-2 extended mission. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2013, 38, 1339–1343. [Google Scholar]

- Bobrinksy, N.; Maldari, P.; Schulz, K.J.; Sessler, G.; Mascaraque, Í. ESA’s Space Communication Architecture and Ground Station Evolution. In Proceedings of the SpaceOps 2008 Conference, Heidelberg, Germany, 12–16 May 2008; p. 3237. [Google Scholar]

- Barriot, J.; Serafini, J.; Sichoix, L. Calibration of the KA Band Tracking of the Bepi-Colombo Spacecraft (more Experiment). In Proceedings of the AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, San Francisco, CA, USA, 9–13 December 2013; Volume 2013, p. P13A-1743. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Li, P.; Fan, M. Orbit determination of CE-5T1 in Earth-Moon L2 libration point orbit with ground tracking data. 42nd COSPAR Sci. Assem. 2018, 42, B3-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sanyal, A.K.; Warier, R.R.; Qiao, D. Landing of Hopping Rovers on Irregularly-shaped Small Bodies Using Attitude Control. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 65, 2674–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qiao, D.; Barucci, M. Analysis of equilibria in the doubly synchronous binary asteroid systems concerned with non-spherical shape. Astrodynamics 2018, 2, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Cheng, Y.; Qiao, D.; Huo, Z. An adaptive surrogate model-based fast planning for swarm safe migration along halo orbit. Acta Astronaut. 2022, 194, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Zhu, S.; Cui, P.; Gao, A. An innovative navigation scheme of powered descent phase for Mars pinpoint landing. Adv. Space Res. 2014, 54, 1888–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Qin, T.; Zhou, X. Observability Analysis and Improvement Approach for Cooperative Optical Orbit Determination. Aerospace 2022, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Qin, T.; Meng, L. Maneuvering Spacecraft Orbit Determination Using Polynomial Representation. Aerospace 2022, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile, M.; Sironi, F.; Bernelli-Zazzera, F. Deep space autonomous orbit determination using CCD. In Proceedings of the AIAA/AAS Astrodynamics Specialist Conference and Exhibit, Monterey, CA, USA, 5–8 August 2002; p. 4818. [Google Scholar]

- Yim, J.R.; Crassidis, J.L.; Junkins, J.L. Autonomous orbit navigation of two spacecraft system using relative line of sight vector measurements. In Proceedings of the AAS Space Flight Mechanics Meeting, Maui, HI, USA, 8–12 February 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.; Gan, Q.; Zhang, J.; Lu, B.; Ma, J. An orbit determination method using space-based angle measured data. Acta Astron. Sin. 2008, 49, 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Cai, W.; Sun, C. Monocular vision-based relative motion parameter estimation for non-cooperative objects in space. Aerosp. Control Appl. 2010, 36, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G. Research on Non-Cooperative Target Tracking Algorithms and Related Technologies Using Space-Based Bearings-Only Measurements, Graduate School of National University of defence Technology; Graduate School of National University of Defense Technology: Singapore, 2011; pp. 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R. Study on Autonomous Optical Navigation Technology for Deep Space Probe; Graduate School of Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Nanjing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, D.; Mao, Q.; Jiang, J. Transfer to near-Earth asteroids from a lunar orbit via Earth flyby and direct escaping trajectories. Acta Astronaut. 2017, 133, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Qiao, D.; Cui, H.; Luan, E. Target selection and transfer trajectories design for exploring asteroid mission. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2010, 53, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestrini, S.; Piccinin, M.; Zanotti, G.; Brandonisio, A.; Lunghi, P.; Lavagna, M. Implicit Extended Kalman Filter for Optical Terrain Relative Navigation Using Delayed Measurements. Aerospace 2022, 9, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiao, W.; Ma, J.; Song, X. Autonav of navigation satellite constellation based on crosslink range and orientation parameters constraining. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2005, 30, 439–443. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Qiao, D.; Li, P. Frozen orbit design and maintenance with an application to small body exploration. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 92, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channumsin, S.; Jaturutd, S. Analysis of coupled attitude and orbit dynamics for uncontrolled re-entry satellite. In Proceedings of the 2019 7th International Electrical Engineering Congress (iEECON), Cha-am, Thailand, 6–8 March 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Warier, R.R.; Sanyal, A.K.; Qiao, D. Trajectory tracking near small bodies using only attitude control. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2019, 42, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Hu, X.; Zhou, S.; Liu, L.; Pan, J.; Chen, L.; Guo, R.; Zhu, L.; Hu, G.; Li, X.; et al. Initial results of centralized autonomous orbit determination of the new-generation BDS satellites with inter-satellite link measurements. J. Geod. 2018, 92, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiao, D.; Cui, P. Design of optimal impulse transfers from the Sun–Earth libration point to asteroid. Adv. Space Res. 2015, 56, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, X.; Guo, L. An autonomous navigation study of Walker constellation based on reference satellite and inter-satellite distance measurement. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Chinese Guidance, Navigation and Control Conference, Yantai, China, 8–10 August 2014; pp. 2553–2557. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, T.; Qiao, D.; Macdonald, M. Relative orbit determination using only intersatellite range measurements. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2019, 42, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edery, A. Earth Shadows and the SEV Angle of MAP’s Lissajous Orbit at L2. In Proceedings of the AIAA/AAS Astrodynamics Specialist Conference and Exhibit, Monterey, CA, USA, 5–8 August 2002; p. 4428. [Google Scholar]

- Adhya, S.; Sibthorpe, A.; Ziebart, M.; Cross, P. Oblate earth eclipse state algorithm for low-earth-orbiting satellites. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2004, 41, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Cui, P.; Cui, H. Proposal for a multiple-asteroid-flyby mission with sample return. Adv. Space Res. 2012, 50, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, G.; Savransky, D.; Gustafson, E.; Shapiro, J.; Keithly, D.; Della Santina, C. Navigation and Orbit Phasing of Modular Spacecraft for Segmented Telescope Assembly about Sun-Earth L2. In Proceedings of the American Astronomical Society Meeting Abstracts# 233, Seattle, WA, USA, 6–10 January; Volume 233, p. 157.20.

- Wang, Y.M.; Qiao, D.; Cui, P.Y. Design of low-energy transfer from lunar orbit to asteroid in the Sun-Earth-Moon system. Acta Mech. Sin. 2014, 30, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canalias, E.; Gomez, G.; Marcote, M.; Masdemont, J. Assessment of Mission Design Including Utilization of Libration Points and Weak Stability Boundaries; ESA Advanced Concept Team: Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, R.W.; Dunham, D.W.; Guo, Y.; McAdams, J.V. Utilization of libration points for human exploration in the Sun–Earth–Moon system and beyond. Acta Astronaut. 2004, 55, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tu, R.; Zhang, P.; Liu, J.; Lu, X. Study of satellite shadow function model considering the overlapping parts of Earth shadow and Moon shadow and its application to GPS satellite orbit determination. Adv. Space Res. 2019, 63, 2912–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.K.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, J.; Kushvah, B.; Ramakrishna, B.; Ekambram, P. Earth conical shadow modeling for LEO satellite using reference frame transformation technique: A comparative study with existing earth conical shadow models. Astron. Comput. 2015, 9, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Topputo, F. Indirect Optimization for Low-Thrust Transfers with Earth-Shadow Eclipses. In Proceedings of the 31st AAS/AIAA Space Flight Mechanics Meeting, Charlotte, NC, USA, 31 January–4 February 2021; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Toulmonde, M. The diameter of the Sun over the past three centuries. Astron. Astrophys. 1997, 325, 1174–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Ziebart, M.; Bhattarai, S.; Harrison, D. A shadow function model based on perspective projection and atmospheric effect for satellites in eclipse. Adv. Space Res. 2019, 63, 1347–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).