Featured Application

This study helps Moodle users to choose the plugin that best suits their needs to create large question banks.

Abstract

The use of Learning Management Systems (LMS) has had rapid growth over the last decades. Great efforts have been recently made to assess online students’ performance level, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Faculty members with limited experience in the use of LMS such as Moodle, Edmodo, MOOC, Blackboard and Google Classroom face challenges creating online tests. This paper presents a descriptive and comparative study of the existing plugins used to import questions into Moodle, classifying them according to the necessary computing resources. Each of the classifications were compared and ranked, and features such as the support for gamification and the option to create parameterised questions are explored. Parameterised questions can generate a large number of different questions, which is very useful for large classes and avoids fraudulent behaviour. The paper outlines an open-source plugin developed by the authors: FastTest PlugIn, recently approved by Moodle. FastTest PlugIn is a promising alternative to mitigate the detected limitations in analysed plugins. FastTest PlugIn was validated in seminars with 230 faculty members, obtaining positive results about expectations and potential recommendations. The features of the main alternative plugins are discussed and compared, describing the potential advantages of FastTest PlugIn.

Keywords:

content creation tools; plugin; Moodle; e-learning technologies; LMSs; XML file; quiz; parameterised questions 1. Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, teaching programs were switched to online learning [1,2,3], which posed a significant challenge for both students and professors. In the literature, there are numerous studies that have analysed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning [4,5,6,7,8]. Some universities were already familiar with the use of e-learning methods before the beginning of the pandemic, and in fact, e-learning methods have been used since the beginning of the 21st century [9,10,11]. According to Dahlstrom et al. (2014) [12], 99% of institutions have Learning Management Systems (LMSs) in place, and 85% of faculty members use them. In Spain, 85% of faculty members were found to use an LMS almost daily for synchronous or asynchronous online teaching during the lockdown imposed due to the pandemic [13]. However, 60% of these faculty members did not have previous experience in online teaching [13]. The main difficulties with the use of e-learning methods reported by faculty were a lack of time (62.1%) and insufficient knowledge of the use of the LMS (29.6%).

Once online classes had been established, the next step was to assess students’ performance level. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, examinations were sometimes postponed; however, as lockdowns continued, institutes of higher education were forced to offer online examinations [14]. Online examination has both advantages and disadvantages for institutions, faculty members and students [15,16,17,18]: it is considered to be more economical and environmentally friendly (paper saving), and to have some other advantages such as automatic grading, student authentication and effectiveness [19,20]. However, online assessment also involves some disadvantages, such as a lack of technological resources by students [21,22], network connectivity problems [23,24] and the difficulty of detecting cheating [25,26].

One of the biggest challenges is to ensure the credibility, security, and validity of online assessment. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, cheating detection was one of the main concerns of faculty members [27,28,29,30], and several works have recently been published on this topic [16,31,32,33]. There is no general agreement in academia as to which online examination method is most suitable for assessing students [16,34,35,36]. Boitshwarelo et al. [34] studied the use of online tests in assessing learning in the 21st century. Online tests (also known as online quizzes) are a kind of computer-assisted assessment in which deployment and grading are automatic. The use of online tests has undergone rapid growth over the last two decades due to the widespread implementation of LMSs in higher education [37]. Gipps [38] highlighted the efficiency of online tests due to the use of automatic marking and feedback. According to Brady [39], online tests can be used to assess a wide range of topics within a short period of time; in addition, students have positive attitudes towards online testing [40,41]. It should be noted that the effectiveness of online tests increases when implemented in conjunction with other assessment methods [42].

Boitshwarelo et al. [34] proposed some principles for the design of online tests, based on an extensive literature review. One of the most successful strategies for minimising cheating identified in [43] was the use of multiple versions of the test in which the order of the questions and responses is randomised. In general, online tests may be composed of Multiple-Choice Questions (MCQs), matching questions, true/false questions and short answer questions, among others. The use of parameterised questions is a good option for creating individualised exercises. A parameterised question is a template for a question in which some parameters (numbers and/or text) are randomly generated based on a specific set of replacement values. In this way, each parameterised question can generate a large (or even unlimited) number of different questions. Consequently, individualised online tests can be generated based on a fairly small number of parameterised questions, which is very useful for large classes. Parameterised questions can be set manually (which requires a lot of time and work) or by using the tools provided in an LMS.

LMSs have undergone significant development over the last few decades for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) courses [44,45], and there are currently a high number of such systems for academic/educational purposes. Moodle, Edmodo, Massive Online Open Courses (MOOC), and Google Classroom were highlighted as being the most widely used and researched between 2015 and 2020 [46]. Comparisons between different LMSs can be found in the literature [47,48]. Moodle is the most popular open-source LMS, according to a recent work [49], and is used worldwide due to its high rate of acceptance in the academic community [50]. The number of Moodle users has shown an increasing trend in recent years, reaching 329 million at the beginning of August 2022 (Moodle Statistics: https://stats.moodle.org (accessed 16 August 2022)). As an open-source LMS, it facilitates creativity by its users. Moodle has a growing library of over 2000 plugins that are shared with the user community (Moodle Plugins: https://moodle.org/plugins (accessed on 3 September 2022)). The most frequently used tools in Moodle are “quizzes” and “workshops” [44]. However, the steep learning curve involved in transferring paper tests to the Moodle platform and/or the creation of parameterised questions can be daunting for faculty members with insufficient experience of this platform [51]. In order to solve this problem, Moodle allows users to import questions in a variety of formats [52]. While this process requires some experience with import codes, some plugins allow for easy conversion of text to Moodle questions. In fact, 145 of the 202 Moodle activity module plugins are intended for quiz activities, and 20 of them offer formats for the import/export of questions.

In summary, the use of online examination has increased significantly due to the COVID-19 pandemic, although faculty members have not typically had previous specific training in online assessment. This indicates the need for tools that can ease the creation of online tests.

In this article, we develop a descriptive and comparative study about the available Moodle plugins used to import questions into Moodle. First of all, a literature review is carried out. Considering the detected limitations in the review, we propose the use of a new open-source Moodle plugin called FastTest PlugIn (FastTest PlugIn: https://moodle.org/plugins/view.php?id=2831 (accessed on 16 August 2022)). This is a Microsoft® Excel-based plugin that allows for the importing of MCQs, true/false, matching, short answer, essay, missing word, Cloze and description questions, in an easy and intuitive way. Additionally, FastTest PlugIn provides the creation of parameterised questions to generate large numbers of different questions. Hence, faculty members with limited Moodle experience can develop a question pool without a great deal of time and effort. FastTest PlugIn was used and validated by 230 faculty members about if expectations were met and if they would recommend it. Finally, the features of FastTest PlugIn are compared with other Moodle plugins to evaluate if the limitations are mitigated; this will make it easier to select the best plugin to use, depending on the available resources.

In Section 2, we carry out a literature review of the plugins that can be employed to import questions in Moodle, and those that are most relevant are studied in greater detail. In Section 3, we describe a proposal to mitigate the detected limitations in the reviewed plugins. In Section 4, we present the principal functions included in a new Moodle plugin called FastTest PlugIn. Section 5 presents a comparison of the main features of the plugins identified in Section 2.3 with our proposal. Finally, the conclusions of this work are summarised in Section 6.

2. Related Research

In this section, a state of the art on existing plugins is developed to identify previous works related to the research topic of this article, which involves plugins that can be used to import questions into Moodle. The features of the main previous research projects are discussed. Finally, based on these features, the plugins that offer most features are selected.

2.1. State of the Art

The formats used to import questions in Moodle are as follows (Moodle Import Questions: https://docs.moodle.org/311/en/Import_questions (accessed on 16 August 2022)):

- Aiken: A simple format for importing MCQs from a text file;

- Blackboard: A format for importing plain text questions (.dat files) or a question with associated media such as images, sounds, etc. (.zip file);

- Embedded answers (Cloze): A format for importing multiple types of questions;

- Examview: A format for importing questions from ExamView4 Extensible Markup Language (XML) files;

- General Import Format Technology (GIFT): A proprietary Moodle format for importing MCQs, true/false, short answer, matching, missing word, numerical and essay questions via text files;

- Missing word: A format similar to GIFT for importing MCQs and short answer questions;

- Moodle XML: A proprietary Moodle format for importing questions via XML;

- WebCT: A format for importing short answer, multiple choice/single answer and multiple choice/multiple answer questions, calculations and essays, which are saved in WebCT’s text-based format.

The Aiken, Cloze and missing word formats were discarded, as these can only import one type of question. The Blackboard, Examview and WebCT formats were also discarded, as these are external platforms. Consequently, GIFT and Moodle XML were the only import formats considered in this work. The former enables the importation of a wide variety of types of questions with simple coding, while the latter enables the importation of all types of questions that can be created in Moodle. The Moodle XML format also allows for the importation of additional information beyond the question itself, such as feedback and clues. The main drawback of this format is that its programming code can be considered complex and non-intuitive for faculty members with no programming skills.

When the import formats had been selected, a scoping literature review was conducted to identify the existing Moodle plugins for importing questions in these formats. A search was carried out of the Moodle plugin directory, the forums used by the Moodle community, and research projects presented at conferences on Moodle and other platforms. The search terms used in the review were: import questions, quiz, Moodle, XML, GIFT, and plugin.

In terms of the number of downloads, “Microsoft Word File Import/Export” was the Moodle plugin most frequently used to import/export the questions collected in the “Question format” directory (Moodle Question Formats Statistics: https://moodle.org/plugins/stats.php?plugin_category=30 (accessed on 16 August 2022)). It was created in July 2012 and had been downloaded almost 6329 times over the last year (an average of 17 downloads per day). The next most popular plugin in the most-downloaded list was “H5P content types”, which was created in May 2020 and had been downloaded 3895 times in the last year (an average of 11 per day). This plugin is not considered in this article, as it enables the importation of various H5P content types into the Moodle question pool. The third position in the list of most frequently downloaded plugins was “GIFT with media’s format”. This plugin was created in April 2013 and had been downloaded more than 715 times in the last year (an average of two per day). The rest of the plugins were used to import questions developed in other formats (such as CSV) and/or in platforms that were not related to Moodle and are therefore not considered in this research.

Finally, some other plugins that could be used to import questions into Moodle were found via the Moodle forums. There are several plugins for LaTeX users, such as “Scientific WorkPlace” [53] and “Moodle package” [54]. The former is limited to MCQs, while the latter allows for the definition of a greater variety of question types. However, neither of these are considered in this study, as users are required to have prior knowledge of the LaTeX programming language.

2.2. Moodle Plugins for Importing Questions

In this section, the features of the main Moodle plugins for the importation of questions are reviewed (operation, language, ease of use, types of questions, etc.). The plugins are classified based on the computing resources needed.

2.2.1. Web-Based Plugins

These can be used with any operating system, and only an Internet connection is required:

- VLEtools.com

This plugin allows for the creation of quizzes and glossaries for Moodle (Ivanova, Y. VLEtools: Moodle XML Converter; http://www.vletools.com/converter/quiz (accessed on 16 August 2022)). It includes MCQs, true/false, short answer, essay, numerical, matching, order, description, and Cloze questions. The procedure for the creation of the questions is described on its webpage, with some illustrative examples. The question format in VLEtools is very similar to that of GIFT. An XML file is generated with all the questions ready to be imported into Moodle. VLEtools also allows for previsualisation of the questions and provides information and warnings about possible errors in their definition;

- Moodle test creator

This web-based plugin allows the creation of a question pool for Moodle (Vilas, M. Moodle test creator; http://text2gift.atwebpages.com/Text2GiftConverter.html (accessed on 16 August 2022)); it focuses on the management of a large number of questions, which can include MCQs, true/false, short answer, essay, and numerical questions. There are some specific rules for the definition of each type of question (the webpage gives some illustrative examples). A GIFT file is generated with all the questions ready for importing into Moodle. A warning message may appear if an error is found in the definition of the question.

2.2.2. Specialised Software

This is also an option for creating question pools to be imported into Moodle:

- Question Machine

This is free software [55] that provides a user-friendly Microsoft® Windows interface for the creation of question pools ready for importing into Moodle in XML format. It includes MCQs, true/false, short answer, numerical, matching, and Cloze questions. The software generates an XML file with all the questions, and users can export them all at once or select a particular type of question. If a question is incomplete, users cannot save it. Images are easily managed and are displayed via the interface (“what you see is what you get”). Question Machine is supported by the Windows operating system;

- Quiz Faber

Quiz Faber (Galli, L. QuizFaber; https://www.quizfaber.com/index.php/en (accessed on 16 August 2022)) is free Windows software for the creation of multimedia quizzes in Hyper Text Markup Language (HTML). The following types of question are supported: MCQs, true/false, matching, and essay questions. In addition, quizzes can be imported into Moodle (only for the types of question types supported by the platform). Images are easily managed, and warning messages appear if the question data are incomplete.

2.2.3. Plugins Developed in Text Processors

In the literature, there are several plugins that were developed in text processors such as Microsoft® Word or OpenOffice Writer. In the same way as for the plugins in Section 2.2.2, an Internet connection is not required to create question pools:

- QT_Machining, QT_Cloze, QT_TrueFalse

Hata et al. [56] presented some tools based on Word and Excel. These plugins are not available online, and all the information about them is in Japanese, which makes it difficult to analyse their features. However, this demonstrates that the introduction of questions into Moodle is a major concern for faculty members all over the world;

- Libre Gift

Libre Gift (Libre Gift; https://code.google.com/archive/p/libre-gift (accessed on 16 August 2022)) allows for the creation of questionnaires in GIFT and XML formats ready for importing into Moodle. It is based on Open Office Writer (free software) and includes the following types of questions: MCQ, true/false, missing word, short answer, matching, numerical, and Cloze questions. If question data are not correctly introduced, no warning message is displayed. Question pools are imported into Moodle in XML and GIFT formats;

- Moodle2Word

This is a plugin based on Microsoft® Word that imports questions (including images and equations) from structured tables in a .docx file. It also exports questions to a Word file, allowing for round-trip editing (Campbell, E. Microsoft Word File Import/Export: https://moodle.org/plugins/qformat_wordtable (accessed on 16 August 2022). The following types of questions are included in Moodle2Word: MCQs, all or nothing MCQs, true/false, missing word, short answer, matching, essay, description, and Cloze questions. Moodle2Word must be installed into the Moodle platform by an administrator. The webpage for this software provides sample templates for all types of questions. The steps that must be followed to enter the question data into the template are very clear, but the document is unlocked, and parts of it may be unintentionally deleted. The user is not shown a warning message if the question data are not correctly entered. Questions can be exported into XML and GIFT formats. Moodle2Word was developed in July 2012, and is currently installed in almost 4000 Moodle sites.

2.2.4. Spreadsheet-Based Plugins

Several plugins based on spreadsheets have been developed. Most of these require Microsoft® Excel to be installed, and were developed using the Visual Basic for Application (VBA) programming language (meaning that macOS users may experience problems). These plugins do not require an Internet connection to create the question pool:

- CQ4M Generator

This allows for the creation of large question pools for Moodle based on Excel (Bollaert, H. CQ4M Generator; https://sites.google.com/site/cq4mgenerator/home (accessed on 16 August 2022). It includes MCQs, numerical, Cloze, and binomial distribution questions. Each type of question is stored in a different Excel file, and question data are directly entered into the corresponding cells, with the exception of Cloze questions, where the lines of code must be directly entered. The spreadsheet is totally unlocked, so the user needs to be careful when entering questions as important cells may be deleted unintentionally. In addition, if the question data are not entered correctly, there is no warning message. This is also the case when generating the XML file, meaning that some errors may appear when the file is imported into Moodle. The language used in CQ4M Generator is English, but the message boxes for the macros are in Dutch. Excel functions can be used for calculation questions. Consequently, CQ4M Generator can create parameterised questions;

- Moodle Cloze and GIFT Code Generator

This is an Excel-based plugin that facilitates the question creation process by generating lines of code that are ready to be imported into Moodle [51]. Different types of questions such as MCQs, true/false, missing word, short answer, essay and Cloze are supported. As the Excel spreadsheet is totally unlocked, the user must enter the question data carefully into the corresponding cells (but it is not necessary for any line of code). Important cells may be deleted unintentionally, and no warning message is displayed if this occurs. Cloze questions include spelling questions. Moodle Cloze and GIFT Code Generator generates a GIFT or XML file to be imported into Moodle;

- Tool based on VBA for the generation of question pools in Moodle

This allows for the generation of question pools for Moodle from an Excel spreadsheet [57]. The following types of question are supported: MCQs, true/false and numerical questions. A tutorial is provided to guide the user when entering question data. This tool also allows for the introduction of images. Finally, an XML file is generated ready to be imported into Moodle.

2.3. Comparison of Moodle Plugins for Importing Questions

In this section, we compare the most important Moodle plugins for importing questions, based on the literature review in Section 2.2. The comparison is carried out according to the question types that each plugin provides. These question types are based on the 16 standard question types of Moodle (Standard question types: https://docs.moodle.org/400/en/Question_types#Standard_question_types (accessed on 16 August 2022).

There are three types of “Calculated” questions in Moodle, but we grouped them in one category to ease the comparison because the plugins shown in this paper included all the calculated question types or none. We also grouped two “Short answer” question types in one category due to similar reasons. Although there are three different question types about “Drag and drop”, we only included “Drag and drop into text” because the other drag and drop question types are only available inside of Moodle.

Then, the comparison of plugins developed in text processors and spreadsheets also considered other relevant features: requirement of installation in Moodle, operating system, parameterised questions, commercial software requirement, written tests, use of images and gamification. Gamification is a strategy that can increase student engagement through the use of typical elements of game playing (e.g., point scoring and competition with one another) in an educational environment [58]. Finally, the most recommended plugin for each category based on the detected features is provided.

2.3.1. Web-Based Plugins

From the web-based plugins described in Section 2.2.1, VLEtools.com is selected since it supports a larger range of different question types (see Table 1). In addition, before generating the XML file, it shows a preview of the result of the question; this option is very useful, as it makes it easier to see whether the question is configured correctly. The rest of the features are similar to those of the Moodle Test Creator plugin. Both have the advantage that as Internet-based software, they can be automatically translated into the language in which the user is working.

Table 1.

Comparison of the features of Web-based plugins.

2.3.2. Specialised Software

Question Machine was selected from this category (defined in Section 2.2.2) as it supports a larger range of different question types and is oriented towards Moodle’s users (see Table 2). Although Quiz Faber has several interesting features, these are not relevant to this research, as they do not relate to creating questions in HTML code.

Table 2.

Comparison of the question types handled by specialised software.

2.3.3. Plugins Developed in Text Processors

Both plugins have very similar features (see Table 3). Moodle2Word was selected from this category (as described in Section 2.2.3) due to its widespread use in the Moodle community. QT_Machining, QT_Cloze, and QT_TrueFalse could not be compared, as they were developed in Japanese. It would be very interesting if the authors were to publish a version in English, so that more users could use it, and could analyse and compare it with the alternatives. Although Libre Gift does not require a Microsoft® license, it has fewer options than Microsoft®, and although it displays a warning when a question is not configured correctly, it is not clear what the error is. However, for non-Windows users, Libre Gift is recommended.

Table 3.

Comparison of the question types handled by plugins developed in text processors.

2.3.4. Spreadsheet Plugins

Moodle Cloze Generator was selected from the spreadsheet plugins reviewed in Section 2.2.4 due to its high functionality (see Table 4). Although compared to the other plugins is that Moodle Cloze Generator does not provide numerical question types while the other plugins do, it provides six different question types and the others only three. Finally, the rest of the features considered in the comparison were similar for all the plugins.

Table 4.

Comparison of the question types handled by spreadsheet plugins.

3. Proposal of a New Plugin to Import Questions in Moodle

After conducting a literature review that is presented in Section 2, we detected some limitations in the existing Moodle plugins for importing questions. Firstly, any Moodle plugin provided all the question types included in the review. The two plugins that provided the most quantity of different question types were: VLEtools and Moodle2Word (eight of 11 question types for both plugins). Then, Libre Gift provided seven question types. However, these plugins are not spreadsheets plugins, which present relevant advantages such as they do not require an Internet connection and allow using functions to generate similar questions with different parameters, simulating parameterised questions. In case of adding a large quantity of questions, an automatic process as the use of parameterised questions could be necessary because it would not be feasible through a manual process.

The selected plugin of the spreadsheet category was Moodle Cloze Generator that only provided six question types. Although it is a spreadsheet plugin, it did not include any option to generate parameterised questions. Finally, Moodle Cloze Generator lacks other features such as Written tests and Gamification features that can be helpful for faculty members who are not Moodle users.

As indicated in Section 1, faculty members need tools that can help them prepare online tests. Although creating questions in Moodle is not a very complex task, it does take time. Users may copy previously created questions and introduce some changes in order to speed up the creation of online tests; however, the creation of a large question pool can be a tedious job and is very time-consuming. The speed of the Internet connection and the number of simultaneous users of the server of the academic institution have a strong influence on the time spent on the elaboration of questions in Moodle. Therefore, advantages as not Internet connection required and the simulation of parameterised questions make spreadsheet plugins as a suitable solution for importing questions in Moodle.

Considering the detected limitations in the literature review carried out in Section 2 and the advantages of spreadsheet plugins, in this paper we describe FastTest Plugin and a comparison with the previously selected plugins is conducted in Section 5.

In 2011, the first version of FastTest PlugIn was conceived as a tool for developing parameterised problems to check students’ understanding of the courses taught as part of the Mechanical Engineering degree at the University of Cadiz (Spain) [30]. This initial version only included Cloze questions, as this is the most versatile of the types of questions included in Moodle. It was developed in Microsoft® Excel using the VBA programming language. Microsoft® Excel was chosen due to its calculation power and its widespread use in the academic community.

FastTest PlugIn was well received by students and faculty members at the University of Cadiz. Hence, after reviewing plugins to import questions in Moodle, a new version of FastTest PlugIn was developed with the objective of mitigating the detected limitations in the literature review conducted in Section 2. Firstly, an option to generate parameterised questions were added to allow for the creation of large question pools that could be imported into Moodle easily and quickly, thus extending the features of the existing plugins. Then, all the types of question analysed in Section 2.1 were added: MCQs, true/false, missing word, short answer, matching, essay, Cloze and description questions. Next, forms were created for each type of question, and thus facilitate the introduction of data to the user.

Several seminaries have been carried out at University of Cadiz about how to use FastTest PlugIn, with a total participation of more than 230 faculty members. Before starting the seminar, the faculty members filled a one-question survey about “what they expected from the seminar”. The survey included one multiple choice question and the faculty members were asked to select as many choices as they agree. Firstly, 76% answered “Greater ease, speed and efficiency for the generation of questionnaires”. Then 16% answered “Improve my knowledge to create questionnaires” (novice Moodle users). Once the course was over, a second one-question survey was sent to evaluate if FastTest PlugIn met their expectations and if they would recommend it. The response was evaluated on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, where 1 is “FastTest PlugIn did not meet any of my expectations and I would not recommend it” and 5 is “FastTest PlugIn met all my expectations and I would recommend it”. A total of 90% answered affirmatively, while the rest described some problems with the plugin: minor errors, such as buttons that did not work well, or user experience problems, such as usual shortcuts that were not available in the plugin. The errors were resolved as soon as we were informed. Then, the user experience was adapted considering the received feedback. These fixes and improvements were included in later versions.

New functionalities were also incorporated into FastTest PlugIn in order to meet the requirements of faculty members, such as the management of images and LaTeX formulas and the use of alternative languages. Another plugin called ForImagine DataBase (Huerta, M. ForImage DataBase. Available online: https://github.com/MilagrosHuerta/ForImage-Database/releases/download/V2.0/ForImage.Database.zip (accessed on 16 August 2022)) was developed to serve as a warehouse for images and LaTeX formulas. This provides users with all the links to the images used in the tests in an organised manner, and allows users to store the most common formulas, which are organised by theme. Cloud-based storage solutions are used to store the images.

FastTest PlugIn was developed in Spanish, and has been translated into English, French, Italian and German. These languages were selected because they are incorporated in Moodle. There are also versions in Portuguese and Simplified Chinese because Brazil and China and two countries where Moodle is widely used. In addition, since Moodle is used in most countries of the world, FastTest PlugIn can be translated into almost any language. There is an option called “Custom Dictionary”, available to users who want to contribute by translating all the text of FastTest PlugIn into their native language.

FastTest PlugIn is under continuous development, based on the ideas and proposals of its users. In December 2021, it was included in Moodle’s plugins directory and had been downloaded almost 685 times (an average of three per day) (Moodle Utilities Statistics: https://moodle.org/plugins/stats.php?plugin_category=59 (accessed on 3 September 2022)).

4. FastTest PlugIn

A beta version of FastTest PlugIn [59] was first made available to the educational community in January 2021 through a YouTube channel (Huerta, M. Herramienta Para Crear de Manera Rápida Bancos de Preguntas Para Los Cuestionarios de Moodle: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC8O0Q5YfdpcmcZKuFeYvsow (accessed on 16 August 2022)). The need for an improved version of this plugin soon arose due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Different versions of FastTest PlugIn were developed to meet users’ needs. Prior to its inclusion within Moodle’s plugins directory, FastTest PlugIn had been downloaded 675 times (Huerta, M. GitHub Release Stats—FastTest PlugIn: https://tooomm.github.io/github-release-stats/?username=MilagrosHuerta&repository=FastTest-PlugIn (accessed on 16 August 2022)). Since FastTest PlugIn was included within Moodle’s plugins directory, it has been downloaded 685 times (199 by January 2022).

The architecture and the main features of this new Moodle plugin are described below.

4.1. Architecture of FastTest PlugIn

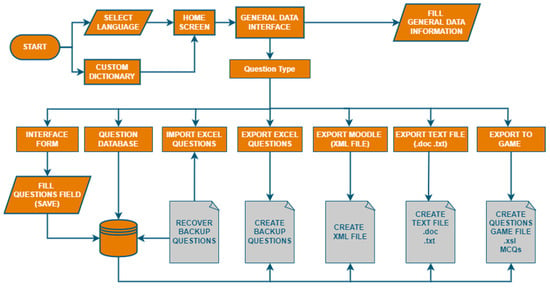

Figure 1 shows the architecture of FastTest PlugIn. Firstly, the language has to be selected. Then, the home interface displays general information of the plugin and allows the user to access to the general data interface. This interface is used to fill the common data for all the question types. Additionally, the user must select the question type to open its corresponding form and develop the questions. After creating all the questions, the user can carry out several actions: import/export the questions from/to an Excel backup file, export the questions to a XML file (to be imported in Moodle later), export the questions in a text file that can be printed in paper tests and export the multiple option questions to an Android game called “Cauchy App” (https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=appinventor.ai_roberto_garmena.CauchyApp1_4_0 (accessed 16 August 2022)).

Figure 1.

Architecture of FastTest PlugIn.

FastTest PlugIn is an open-source software developed using Excel functions and VBA macros. The interfaces were created by blocking all the cells to which the user should not make any changes. For the cells that needed to be filled in, data validation was activated, so that the user could not enter incorrect data. The blue buttons are cells in which the content changes depending on the language selected. These buttons have different functions and were created with simple VBA macros. Some macros carry out simple functions such as scrolling through the different interfaces and copying data from the forms in the question bank interface. The only difference between the forms is the number of fields used to store the data. Finally, the question data are collated using the XML encoding required by Moodle, for each type of question. For the dictionary, there are as many columns as there are built-in languages in the application, and an additional blank column was added to allow the user to enter text in a different language that can be translated by Google (47 more languages). If the translation is not quite right, the user can correct it by entering text in the corresponding line, via the dictionary customisation interface.

4.2. General Operating Principles

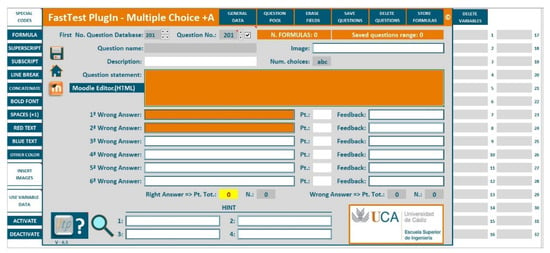

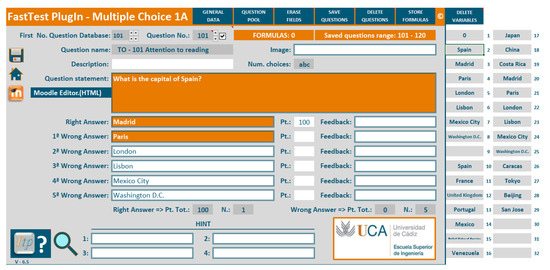

The data entry interfaces for the different types of questions have a uniform style in order to facilitate the entry of the information (see Figure 2). When entering data, the user can move to the next cell by pressing the tab button. Orange cells are mandatory, while white cells are optional. Variable data (grey cells) can be used to create parameterised questions. The cells appear in the “General Data” and “Form” interfaces, and users can choose whether to activate them. This is described in more detail in Section 4.2.3. Warning cells are shown in yellow, and inform the user about a cell that is incorrectly filled in. Cells without borders contain plain text, while cells with a double border can contain text in HTML, including images and video links. All of the interfaces in FastTest PlugIn have a link to the Moodle Editor and give information about the version of the plugin that is being used. All cells also have a personalised help option that informs users about the data that are expected.

Figure 2.

General question data entry interface (the example shows a form for a MCQ with one answer).

Each interface has a drop-down menu that is displayed by a right click. Blue buttons activate different functions. All functions have keyboard shortcuts (indicated in the drop-down menu). In both the “General Data” and “Form” interfaces, there is a lateral menu that contains special codes (such as superscript, subscript, bold, text colour, etc.) in HTML syntax (see Figure 2). In addition, images available on the Internet can be entered by specifying their Uniform Resource Locations (URLs) and viewing dimensions. Finally, in the lateral menu, the variable data can be activated or deactivated (grey cells).

The number of questions of each type appears in all the interfaces except for the “General Data” interface, where the value refers only to the number of questions of the particular type selected. In the case of parameterised questions, there is an option marked “Store Formulas” that allows the user to retrieve and reuse them. This storage option can be also used to save the most commonly used text for feedback. In the following subsections, some of the functionalities are described in more detail.

Finally, a zoom effect was added to display in a larger size the contents of the cells. The zoom function provides a better check of the formulas and is recommended for cells that contain long text strings, such as Cloze and parameterised questions, since visualisation of their content is difficult in regular-sized Excel spreadsheet cells

4.2.1. General Data Interface

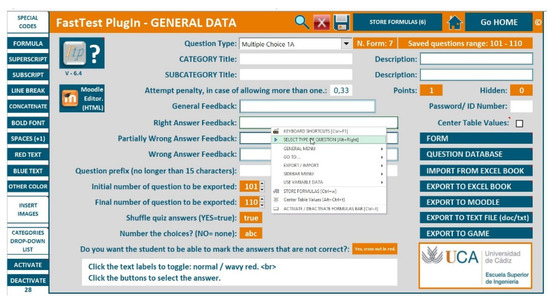

Figure 3 shows the “General Data” interface. All the buttons common to the different types of questions are displayed via this interface. The main cells in the “General Data” interface are as follows:

- Question type: The user selects the type of question (MCQ, true/false, matching, short answer, missing word, essay, Cloze or description). Depending on the type of question chosen, different options are displayed;

- Category and subcategory titles: These can be created with their respective descriptions;

- Attempt penalty: The user enters the penalty for multiple attempts and the question score;

- Feedback: The user can set up general feedback that will appear at the end of the test or after right answers. They can also enter feedback for partially wrong and wrong answers, which will appear after each question;

- Question prefix: A question prefix can be configured as a label for the question. In this way, all questions related to a given topic can have different names but a common prefix;

- Initial and final numbers of questions to be exported: The user can select the range of questions to be exported. A warning message appears if the selected range does not contain all the questions in the spreadsheet (this message can be omitted);

- Shuffle quiz answers: The answers to the questions can be shuffled (if the type of question allows for this);

- Marking answers: The user can decide whether students can mark the answers to their own tests. There is also an optional message that informs the students about this option.

Figure 3.

The “General Data” interface.

4.2.2. Question Pool and Form Interfaces

There is a question pool for each type of question, and all the question data are collected in a table where the number of columns depends on the input fields for each type of question. The questions of the table can be selected to access its corresponding form, new questions can be inserted into the question pool and existing questions can be deleted.

As described in Section 3, FastTest PlugIn supports the following types of question: MCQs (single and multiple answers), true/false, matching, short answer, missing word, essay, Cloze and description questions. Each type of question has its own “Form” interface, whose common options are presented:

- Question pool: Links to the question pool for the selected question type;

- Erase fields: Erases the content of all the cells to allow the user to define a new question from scratch;

- Save questions: Saves a question in the question pool;

- Delete questions: Allows the user to delete questions individually and a set as well;

- Store formulas: This saves the formulas used to create the parameterised question. It allows the user to store frequently used feedback or to retrieve formulas used to create other types of question. In addition, FastTest PlugIn allows for the importation and exportation of formulas so that these can be reused in different versions of the plugin.

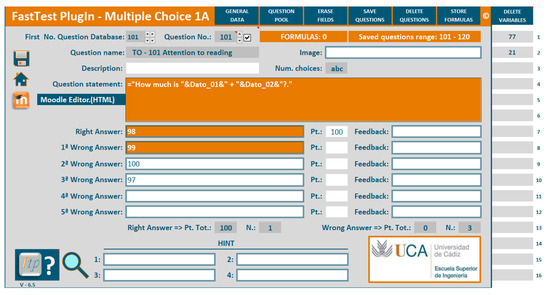

4.2.3. Parameterised Questions

Variable cells must be activated in order to generate parameterised questions. They allow the user to use one click to save up to 100 questions that are based on the same statement but have different data (if the user does not want to create this type of question, the variable cells must be deactivated).

These were designed to exploit the potential of Excel in terms of entering random data or Excel functions. There are up to 32 cells, which are named Dato_01, Dato_02, …, Dato_32. When the user wants to recall a value defined in one of these cells in the statement of a question, only the corresponding name needs to be entered.

To create questions with random values, a very useful Excel function is RANDBETWEEN (bottom, top) (RANDBETWEEN function https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/randbetween-function-4cc7f0d1-87dc-4eb7-987f-a469ab381685 (accessed on 16 August 2022)), which returns a random integer between two specified limits. A new random integer number is returned each time the worksheet is calculated. By joining this function with the CONCATENATE function (or “&”) (CONCATENATE function https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/concatenate-function-8f8ae884-2ca8-4f7a-b093-75d702bea31d (Accessed 16 august 2022)), parameterised questions can be created.

For example, to create the question “How much is Value1 + Value2?”, the user can define a random value in cell Dato_01 and another in cell Dato_02. The formula in the form statement would then be = “How much is “&Dato_01&” + “&Dato_02&”?”. In the correct answer cell, the formula “=Dato_01+Dato_02” would be entered. In the incorrect answers, it is necessary to enter an incorrect formula, for example: “=Dato_01+Dato_02+1”, “=Dato_01+Dato_02+2”, “=Dato_01+Dato_02-1”.

It is important to use the correct punctuation in each answer. Once a parameterised question has been prepared and the SAVE QUESTION button has been clicked, the user is asked how many questions are to be saved. This value can be between one and 100. If the user needs to save more than 100, the “SAVE QUESTION” button can be clicked again. Figure 4 shows an example based on the “Multiple Choice” form.

Figure 4.

Example of a parameterised question with numerical values.

The RANDBETWEEN function only accepts numerical values, and it is not possible to create parameterised questions that contain text using only this function. However, this can be done by combining other Excel functions, and there are several possible ways to achieve this. For example, the INDIRECT (INDIRECT function https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/indirect-function-474b3a3a-8a26-4f44-b491-92b6306fa261 (accessed on 16 August 2022)) and TEXT (TEXT function https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/text-function-20d5ac4d-7b94-49fd-bb38-93d29371225c (accessed on 16 August 2022)) function can be used. Since the cell names end in a number (from one to 32), the function = INDIRECT(“Dato_”& TEXT(RANDBETWEEN(1,32),”00”) can be used to refer to a value stored in cell Dato_0X or Dato_YY (where X or YY is a random value, in format “00”). In this way, the user can enter “Word” inside the Dato_XX cells, and Excel will return “Word”.

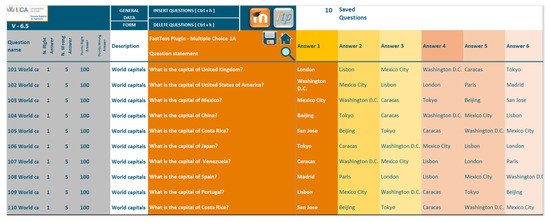

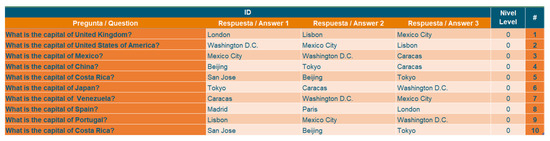

As an example, we take the question = “What is the capital of “&Dato_02&”?” Cells Dato_10 to Dato_19 contain the names of countries. In cells Dato_20 to Dato_29, the names of the capitals are entered (in the same order). Dato_01 contains the formula = RANDBETWEEN(0,9), while Dato_02 contains the formula =INDIRECT(“Dato_1”& Dato_01). In Dato_03 (correct answer), the following formula is entered: = INDIRECT(“Dato_2”& Dato_01). Finally, in cells Dato_04 to Dato_08, the incorrect answers must be entered. For instance, the following formula is used: = INDIRECT(“Dato_2”&IF(Dato_01>=5;Dato_01-X;Dato_01+X)), where X = 1 for Dato_04, X = 2 for Dato_05, X = 3 for Dato_06, X = 4 for Dato_07, X = 5 for Dato_08. Figure 5 shows an example based on the “Multiple Choice” form.

Figure 5.

Example of a parameterised question with text values.

Figure 6 shows the database interface with 10 questions, which are saved at the same time, based on the above formula. The formula can also be saved and used with new text values, for example state capitals. This example involved MCQs, but the same process can be used for all of types of questions supported by FastTest PlugIn.

Figure 6.

Example: saving 10 parameterised questions.

4.2.4. Gamification

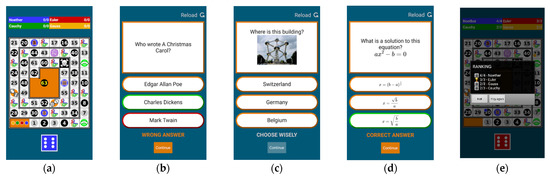

According to Poondej and Lerdpornkulrat [58], Moodle can be used as a learning tool for gamification. These authors deployed game elements in an e-learning course on the Moodle platform, using Moodle quizzes as one type of tool to motivate learners. Since the FastTest PlugIn can help in generating large question banks, this makes it faster to implement game activities for students.

FastTest PlugIn also has an option allowing the user to export questions generated in the MCQ format (with one correct answer) to a game that is available from the Play store (for Android) called Cauchy App. In this way, it is also possible to entice students to play with the questions on the syllabus for the course, without having to be on the Moodle platform. As shown in Figure 7a, up to four players can take part, and each player needs to roll the dice to move a piece. They are presented with a random question from a bank of questions, with up to six levels of difficulty. In addition, MCQs can be created in different formats: text only (Figure 7b); with an image in the statement (Figure 7c); or with formulas (Figure 7d). Figure 7e shows the ranking interface.

Figure 7.

Interfaces in Cauchy App: (a) main interface; (b) example question with text only; (c) example question with an image in the statement; (d) example question based on formulas; and (e) ranking interface.

The questions can be individually created by hand, or with FastTest PlugIn using parameterised questions, as explained in Section 4.2.3. Then, the questions can be exported to a game through a menu. Figure 8 shows an example with questions to be used in a game. For game questions, three answers are exported: the correct answer and two incorrect answers.

Figure 8.

Example of 10 MCQ questions for gaming activities created using FastTest PlugIn.

5. Results and Discussion

In this section, we compare the most important plugins that can be used to import questions into Moodle with FastTest PlugIn. The plugins were selected based on the literature review presented in Section 2.3. They are compared based on the question types that they provide, the available languages and the other features: installation in Moodle, operating system, creation of parameterised questions, commercial software requirements, written tests, gamification possibilities, and use of images.

Table 5 shows the question types supported by each plugin. FastTest PlugIn, Moodle2Word and VLEtools.com can handle a large number of different types of question. It should be noted that numerical questions can be entered in FastTest PlugIn via a Cloze question. The comparison shows how FastTest PlugIn is the only plugin that allows including all the question types considered in this paper. Although calculated questions cannot be directly used in FastTest PlugIn, these questions can be using Excel functions created using Excel functions due to FastTest PlugIn is a spreadsheet plugin. This is an advantage compared to the rest of the plugins of the comparison that do not include this type of questions. Therefore, FastTest PlugIn mitigated the detected limitations about the question types that the Moodle plugins for importing questions provides.

Table 5.

Comparison of question types.

Table 6 shows the available languages for the four studied plugins. FastTest PlugIn stands above the rest as it includes all the languages supported by Google Translate, and; the user can personalise the text displayed on all the buttons and drop-down menus. Using the option “Custom Dictionary”, FastTest PlugIn can be translated into any language supported by Google® Translate. Therefore, FastTest PlugIn provides the same languages and translation functionalities available by the other compared plugins: only VLEtools.com provides the same, the other plugins present less languages and functionalities.

Table 6.

Comparison of available languages.

Table 7 shows a comparison of the other important features of the plugins. Moodle2Word is the only plugin that needs to be installed in Moodle. This may be inconvenient, as only a Moodle administrator can install this type of plugin. The rest of the plugins do not require installation in Moodle. With regard to the operating system, Moodle2Word, Question Machine and FastTest PlugIn are compatible with Microsoft® Windows, while VLEtools.com is compatible with all operating systems. FastTest PlugIn is not fully compatible with macOS (depending on the version, not all the functionalities are available). A version of Question Machine that is compatible with macOS is under development.

Table 7.

Comparison of other features.

FastTest PlugIn is the only one that allows for the creation of parameterised questions. Since it is based on an Excel spreadsheet, parameterised questions can be easily created using formulas. It should be highlighted that although Moodle Cloze Generator is a spreadsheet plugin too, it does not include this functionality. On the one hand, FastTest PlugIn, Moodle Cloze Generator and Moodle2Word require commercial software: Microsoft® Excel for FastTest PlugIn and Moodle Cloze Generator, Microsoft® Word for Moodle2Word. On the other hand, VLEtools.com and Question Machine do not require commercial software. However, due to the widespread use of the Microsoft® Office package all over the world, this requirement is not considered a major drawback. FastTest PlugIn, Moodle2Word and Question Machine allow questions to be exported to text files to create written tests. The only plugin that allows for the creation of games based on the question pool is FastTest PlugIn, which can be used exporting questions to an Android game called “Cauchy App”. Finally, FastTest PlugIn, Moodle2Word and Question Machine allow for the introduction of images. FastTest PlugIn allows images found on the Internet to be used by entering a URL into any of the fields that allow for HTML code. In addition, a further plugin called ForImage DataBase has been developed, which allows for the creation of a pool of images and formulas.

FastTest PlugIn and Moodle2Word are the most complete plugins for importing questions into Moodle. Both require additional commercial software, but FastTest PlugIn does not require installation in Moodle. In addition, questions can be grouped by topic, difficulty, etc., in FastTest PlugIn. The user can store questions in an Excel file, grouped by course, in case there is a need to reuse them in future. Finally, since FastTest PlugIn is based on an Excel spreadsheet, it has all the advantages of this commercial software in terms of its calculation power. Parameterised questions can be defined using all of Excel’s functions, and this is a great advantage of FastTest PlugIn because it provides a process to include a large quantity of questions automatically, mitigating the limitations detected in the carried-out literature review.

6. Conclusions

A descriptive and comparative study about the available Moodle plugins used to import questions into Moodle was developed in this article. An extensive literature review was carried out to describe and select the most important plugins for importing questions in Moodle. Plugins were grouped in categories based on the computing resources required: Web-based plugins, specialised software, plugins developed in text processors and spreadsheet plugins. These plugins were compared according to the question types that they provide and other relevant features, such as the availability to create parameterised questions or gamification functionalities. After this comparison, the most recommended plugin of each category was selected: VLEtools.com (Web-based plugin), Question Machine (specialised software), Moodle2Word (text processor plugin), and Moodle Cloze Generator (spreadsheet plugin).

Several limitations were detected in these plugins. Firstly, none of them provided all the considered question types: MCQs (single and multiple answers), true/false, matching, short answer, missing word, essay, Cloze and description questions. Then, none of the spreadsheet plugins provided parameterised questions: an automatic process that could ease adding a large quantity of questions, which would not be feasible through a manual process. Finally, other relevant features such as Gamification functionalities were not included in the analysed plugins.

Considering the detected limitations in the literature review, in this paper we described FastTest Plugin: a new plugin for importing questions into Moodle. FastTest PlugIn was validated in seminars with 230 faculty members, obtaining positive results about expectations and potential recommendations. Authors took into account the detected limitations to provide FastTest PlugIn with features to mitigate them. FastTest Plugin was included in Moodle’s plugins directory in December 2021 and had been downloaded almost 685 times (an average of three per day). FastTest PlugIn was compared with the selected plugins in the literature review. It was concluded that FastTest PlugIn and Moodle2Word were the most complete plugins for importing questions into Moodle. It was also shown that FastTest PlugIn had several advantages over Moodle2Word.

Firstly, FastTest PlugIn allows for the definition of all the analysed question types. Taking the 16 native question types of Moodle, 14 of these questions can be created with FastTest PlugIn, only 2 drag and drop question types are not available because they cannot be created with plugins that are not embedded in Moodle. Next, as FastTest PlugIn is based on a Microsoft® Excel spreadsheet, the use of Excel functions allows for the definition of parameterised questions. Excel functions can be used to compute the results of numerical questions, meaning that faculty members must only enter the corresponding formulas and the result will be calculated automatically. This reduces the number of mistakes made when entering the question data. Then, FastTest PlugIn allows for the definition of gamified versions of traditional tests, exporting questions generated in the MCQ format (with one correct answer) to a game called Cauchy App (available for Android). Finally, FastTest PlugIn includes all the languages supported by Google Translate.

Based on the carried-out literature review, the recommended plugin for users who do not have Microsoft Office is Question Machine. Although Libre Gift is free software, Question Machine offers more possibilities and there is no need even to install LibreOffice Writer. For non-Windows users, Libre Gift is recommended.

FastTest PlugIn is a new plugin that can be used to import large question pools into Moodle; it offers all the functionalities of in other plugins and provides additional ones such as parameterised questions and gamified tests. Since it allows questions to be created for written exams and for use with Cauchy App, it can also be used by non-Moodle users. FastTest PlugIn is under constant development, and new functionalities will be incorporated in the future in order to meet faculty members’ requirements. A new version is currently being developed.

7. Patents

FastTest PlugIn has been registered as a “Computer Program” in Spain (reference 04/2021/4745).

Author Contributions

M.H.: Conceptualization, software, validation, investigation, writing—original draft preparation. J.A.C.-H.: visualization, writing—review and edition. M.A.F.-R.: visualization, writing—original draft preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present research project was partly financed by the Unidad de Formación e Innovación Docente of the University of Cádiz in the form of a “Proyecto de Innovación y Mejora Docente, code “sol-202000162327-tra” and title “Elaboración de grandes bancos de preguntas/problemas, como complemento a la docencia digital”. This support is gratefully acknowledged.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cuaton, G.P. Philippines Higher Education Institutions in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic. Rev. Rom. pentru Educ. Multidimens. 2020, 12, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas-Ch, W.; Palacios-Pacheco, X.; Roman-Cañizares, M.; Luján-Mora, S. Analysis of Educational Data in the Current State of University Learning for the Transition to a Hybrid Education Model. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, M.; Turko, O.; Dluhopolskyi, O.; Henseruk, H. The Quality of Training Future Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case from Tnpu. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummitha, H.R.; Kolloju, N.; Chittoor, P.; Madepalli, V. Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Its Effect on Teaching and Learning Process in the Higher Educational Institutions. High. Educ. Futur. 2021, 8, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S.; Chhetri, R. A Literature Review on Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Teaching and Learning. High. Educ. Futur. 2021, 8, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheti, I.A.; Nassar, R.I.; Halalşah, İ. The Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on the Learning Process among Students: A Comparison between Jordan and Turkey. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.B.; Silva-Peña, I.; Fernández, L.; Cuenca, C. When the Invisible Makes Inequity Visible: Chilean Teacher Education in COVID-19 Times. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pócsová, J.; Mojžišová, A.; Takáč, M.; Klein, D. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Teaching Mathematics and Students’ Knowledge, Skills, and Grades. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, K.; Pogroszewski, D. Virtual University Reference Model: A Guide to Delivering Education and Support Services to the Distance Learner. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 1998, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Cloete, E. Electronic Education System Model. Comput. Educ. 2001, 36, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feidakis, M.; Daradoumis, T.; Caballé, S.; Conesa, J. Embedding Emotion Awareness into E-Learning Environments. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2014, 9, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrom, E.; Brooks, D.C.; Bichsel, J. The Current Ecosystem of Learning Management Systems in Higher Education: Student, Faculty, and IT Perspectives; Research report; ECAR: Louisville, CO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, I. Educomunicación ¿Online?: Actuación Del Profesorado Universitario Ante Los Escenarios de La Crisis de La COVID-19. In La Comunicación Especializada del Siglo XXI; McGraw-Hill: Interamericana de España, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, J.; Butler-Henderson, K.; Rudolph, J.; Malkawi, B.; Glowatz, M.; Burton, R.; Magni, P.; Lam, S. COVID-19: 20 Countries’ Higher Education Intra-Period Digital Pedagogy Responses. J. Appl. Teach. Learn. 2020, 3, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ilgaz, H.; Adanir, G.A. Providing Online Exams for Online Learners: Does It Really Matter for Them. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, A.; Shazli, T.; Salman, M.S.; Naqvi, H.R.; Ahmad, N.; Ali, N. Challenges of Unrestricted Assignment-Based Examinations (ABE) and Restricted Open-Book Examinations (OBE) during COVID-19 Pandemic in India: An Experimental Comparison. Hum. Behav Emerg Tech 2021, 3, 1050–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón-Sancho, Á.; Vergara, D.; Lamas-álvarez, V.E.; Fernández-Arias, P. Digital Content Creation Tools: American University Teachers’ Perception. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Zambrano, J.; Lara, J.A.; Romero, C. Towards Portability of Models for Predicting Students’ Final Performance in University Courses Starting from Moodle Logs. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayazit, A.; Askar, P. Performance and Duration Differences between Online and Paper-Pencil Test. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. 2012, 13, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parshall, C.G.; Spray, J.A.; Kalohn, J.C.; Davey, T. Practical Considerations in Computer-Based Testing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Randy, G. E-Learning in the 21st Century. A Framew. Res. Pract. 2011, 2, 110–111. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, F.; Rathore, F.A.; Mansoor, S.N. Challenges of Online Medical Education in Pakistan during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pakistan 2020, 30, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Qazi, A.; Naseer, K.; Qazi, J.; AlSalman, H.; Naseem, U.; Yang, S.; Hardaker, G.; Gumaei, A. Conventional to Online Education during COVID-19 Pandemic: Do Develop and Underdeveloped Nations Cope Alike. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Siau, K.; Nah, F.F. COVID-19 Pandemic: Online Education in the New Normal and the next Normal. J. Inf. Technol. Case Appl. Res. 2020, 22, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fask, A.; Englander, F.; Wang, Z. Do Online Exams Facilitate Cheating? An Experiment Designed to Separate Possible Cheating from the Effect of the Online Test Taking Environment. J. Acad. Ethics 2014, 12, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellar, H.; Peytcheva-Forsyth, R.; Kocdar, S.; Karadeniz, A.; Yovkova, B. Addressing Cheating in E-Assessment Using Student Authentication and Authorship Checking Systems: Teachers’ Perspectives. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2018, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureda Negre, J.; Comas Forgas, R.; Gili Planas, M. Prácticas Académicas Deshonestas En El Desarrollo de Exámenes Entre El Alumnado Universitario Español. Estud. Sobre Educ. 2009, 17, 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Comas, R.; Sureda, J.; Casero, A.; Morey, M. La Integridad Académica Entre El Alumnado Universitario Español. Estud. Pedagog. 2011, 37, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, N. Cheating in Online Student Assessment: Beyond Plagiarism. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 2004, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta, M.; Portela, J.M.; Pastor, A.; Otero, M.; Velázquez, S.; González, P. Cómo Preparar Una Gran Colección de Problemas Virtuales, Para Que Los Alumnos Aprendan. In Proceedings of the VIII Jornadas Internacionales de Innovación Universitaria, Universidad Europea de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 11–12 July 2011; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Montejo Bernardo, J.M. Exámenes No Presenciales En Época Del COVID-19 y El Temor Al Engaño. Un Estudio de Caso En La Universidad de Oviedo. Magister 2020, 32, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haus, G.; Pasquinelli, Y.B.; Scaccia, D.; Scarabottolo, N. Online Written Exams during COVID-19 Crisis. In Proceedings of the 14th IADIS International Conference e-Learning 2020, MCCSIS 2020, Croatia (online), 21–23 July 2020; pp. 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, R.; Farooq, O. Online Exams in the Time of COVID-19: Quality Parameters. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Stud. 2020, 7, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boitshwarelo, B.; Reedy, A.K.; Billany, T. Envisioning the Use of Online Tests in Assessing Twenty-First Century Learning: A Literature Review. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2017, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.R.A.; Ahmed, T.E.; Saeed, R.A.; Alhumyani, H.; Khalek, S.A.; Zinadah, H.A. Analysis and Challenges of Robust E-Exams Performance under COVID-19. Results Phys. 2021, 23, 103987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Tocón, I. Moodle Quizzes as a Continuous Assessment in Higher Education: An Exploratory Approach in Physical Chemistry. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D.E.; Zheng, G. Learning Management Systems in a Changing Environment. In Handbook of Research on Education and Technology in a Changing Society; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2014; pp. 756–767. [Google Scholar]

- Gipps, C.V. What Is the Role for ICT-based Assessment in Universities? Stud. High. Educ. 2005, 30, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, A.M. Assessment of Learning with Multiple-Choice Questions. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2005, 5, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, C. The Use of Case Based Multiple Choice Questions for Assessing Large Group Teaching: Implications on Student’s Learning. Irish J. Acad. Pract. 2014, 3, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Baleni, Z.G. Online Formative Assessment in Higher Education: Its Pros and Cons. Electron. J. e-Learning 2015, 13, 228–236. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M.; Wilson, J.; Ennis, S. Multiple-Choice Question Tests: A Convenient, Flexible and Effective Learning Tool? A Case Study. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2012, 49, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, O.R.; Lambrinos, J.; Buffolino, J. Assessment Design and Cheating Risk in Online Instruction. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 2010, 13, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Gamage, S.H.P.W.; Ayres, J.R.; Behrend, M.B. A Systematic Review on Trends in Using Moodle for Teaching and Learning. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2022, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáiz-Manzanares, M.C.; Rodríguez-Díez, J.J.; Díez-Pastor, J.F.; Rodríguez-Arribas, S.; Marticorena-Sánchez, R.; Ji, Y.P. Monitoring of Student Learning in Learning Management Systems: An Application of Educational Data Mining Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiadi, P.M.; Alia, D.; Sumardi, S.; Respati, R.; Nur, L. Synchronous or Asynchronous? Various Online Learning Platforms Studied in Indonesia 2015–2020. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1987, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkoukani, M. Explore the Major Characteristics of Learning Management Systems and Their Impact on E-Learning Success. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2019, 10, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, N.S.; Shibghatullah, A.S.; Subaramaniam, K.A.P.; Wahab, M.H.A. A Systematic Review for Online Learning Management System. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1874, 12030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinpulluk, H.; Kesim, M. A Systematic Review of the Tendencies in the Use of Learning Management Systems. Turkish Online J. Distance Educ. 2021, 22, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergis, S.; Vlachopoulos, P.; Sampson, D.G.; Pelliccione, L. Implementing Teaching Model Templates for Supporting Fipped Classroomenhanced STEM Education in Moodle. In Handbook on Digital Learning for K-12 Schools; Marcus-Quinn, A., Hourigan, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 191–215. [Google Scholar]

- Svien, J. Streamlining Moodle’s Question Creation Process with Excel. In Proceedings of the MoodleMoot Japan 2017 Annual Conference, Moodle Association of Japan, Okinawa, Japan, 31 October 2017; pp. 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mintii, I.S.; Shokaliuk, S.V.; Vakaliuk, T.A.; Mintii, M.M.; Soloviev, V.N. Import Test Questions into Moodle LMS. In Proceedings of the 6th Workshop on Cloud Technologies in Education (CTE 2018), Kryvyi Rih, Ukraine, 21 December 2018. CEUR-WS.org. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, F.; Garzón, V.; Jiménez, J.A.; Arbeláez, R.F. Generation of Random Questions with Multiple Choice Single Answer for Moodle. Lámpsakos 2011, 3, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson, A.; College, S.N.; Pere, D. The Moodle Package: Generating Moodle Quizzes via LaTeX. 2016, pp. 1–12. Available online: http://tug.ctan.org/tex-archive/macros/latex/contrib/moodle/moodle.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Gourdie, J.; Fendall, A. Question Machine: A Tool for Creating Online Assessments in the Blended Learning and Moodle Environment. In Proceedings of the New Zealand Applied Business Education Conference 2012: Enhance, Engage, Educate, Hamilton, New Zealand, 1–3 October 2012; Volume 43, pp. 325–443. [Google Scholar]

- Hata, A.; Ueki, S.; Toyama, K. Improvement of Word-XML Conversion Tools and Expansion of Launcher. In Proceedings of the MoodleMoot Japan 2019 Annual Conference; Moodle Association of Japan: Okinawa, Japan, 2019; pp. 1–48. ISSN 2189-5139. [Google Scholar]

- González Gijón, V. Herramienta Basada En VBA Para Generación de Bancos de Preguntas En Moodle. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña, Cataluña, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Poondej, C.; Lerdpornkulrat, T. Gamification in E-Learning: A Moodle Implementation and Its Effect on Student Engagement and Performance. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2019, 17, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, M.; Fernández Ruiz, M.A. FTP: FastTest PlugIn, Aplication to Create Big Question Banks of Different Types for the Moodle Platform. In Proceedings of the CINAIC 2021: VI Congreso Internacional Sobre Aprendizaje, Innovación y Cooperación, Madrid, Spain, 20–22 October 2021; pp. 643–648. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).