Abstract

The need for automated data extraction is continuously growing due to the constant addition of information to the worldwide web. Researchers are developing new data extraction methods to achieve increased performance compared to existing methods. Comparing algorithms to evaluate their performance is vital when developing new solutions. Different algorithms require different datasets to test their performance due to the various data extraction approaches. Currently, most datasets tend to focus on a specific data extraction approach. Thus, they generally lack the data that may be useful for other extraction methods. That leads to difficulties when comparing the performance of algorithms that are vastly different in their approach. We propose a dataset of web page content blocks that includes various data points to counter this. We also validate its design and structure by performing block labeling experiments. Web developers of varying experience levels labeled multiple websites presented to them. Their labeling results were stored in the newly proposed dataset structure. The experiment proved the need for proposed data points and validated dataset structure suitability for multi-purpose dataset design.

1. Introduction

The landscape of information systems is evolving, the amount of digital information increases daily. The need to collect, process, and access stored information also continuously grows. This constant growth makes manual data processing impossible. So the importance of automated data exchange between systems is becoming increasingly relevant and utilized.

There are many sources of information that can be used for data collection, and one of them is publicly available data on various web pages. To efficiently process information presented on a website, it needs to be identified first. Modern websites tend to have a lot of secondary information present on them, which has little to no value. Thus, this kind of information needs to be discarded. During initial identification, only the relevant information is stored and used for further processing. That way, overall efficiency is improved. Suitable information blocks can be identified in multiple ways [1]. The main techniques include—data-based extraction, structure-based extraction, vision-based extraction, or a complex approach that uses two or more techniques [2,3]. Various techniques have their advantages and disadvantages. None of them are perfect yet [4]. It is not easy to compare the results obtained using various methods due to them using different data points and different websites for performance evaluation.

Determining the content block’s type and purpose can be done by analyzing various data points. Classification solutions used in this process can vary greatly. The latest website content extraction and analysis methods are based on supervised learning. These methods require a dataset with labeled website data. A dataset is used to train the model and to evaluate the performance. Therefore, a well-defined web page dataset with labeled blocks would be valuable both for development and research purposes.

Various researchers use different webpage datasets because different methods require different data points for data extraction. Some techniques use an HTML (hyper-text markup language) structure, some use styling information, while others need screenshots, etc. [4,5]. Thus, it is hard to establish a proper performance comparison between different approaches and proposed algorithms [6,7]. It can be said that there is a need for a dataset that would include all the required information no matter what data extraction approach is used. Such a dataset can be used for machine learning applications since they require initial data for the learning process. Having a well-structured dataset would greatly help in this field as it could be used as a basis for the new website analysis solutions. It can also be used for testing or efficiency comparison of different approaches.

This paper aims to ease the development of website content extraction solutions by providing a unified source of data that can be used for training and validation of web page content block extraction solutions. Therefore the contribution of this paper includes:

- Dataset structure. We propose a design of a multi-purpose web page dataset for content block labeling. This dataset includes various types of information about stored web pages, therefore providing broader usage possibilities. The dataset structure is not just a combination of different data points. The proposed dataset structure solves the content block perception problem and presents the idea of block variations. It also allows maintaining a hierarchical structure within content blocks.

- Content block perception variety estimation. Results of the executed research on the webpage content block labeling process highlight the content block variation problem and present an initial variety scale. These results can be used as a conceptual idea to improve content block labeling solutions by incorporating content block size variation. Performed experiments also provide data for semantic concept and tag similarity estimation in the field of web pages.

2. Related Works

Research in the field of automated data extraction is very active due to its relevance. We reviewed some of the popular approaches for automated data identification and extraction from websites. Focusing on the data needed to analyze the webpage content and determined the performance of selected methods. Therefore analysis on whether this kind of data is available for public usage was performed too.

2.1. Approaches and Problems for Automated Website Content Block Identification

Nowadays, website data is presented in a semi-structured way. While the semantic web is not fully adopted in practice, most website data is incorporated in layout and design rather than content blocks [8]. HTML5 added some tags that would help make the structure more informative. In a way, these new tags made some parts of the websites more semantic, but the website’s overall structure still mainly describes its layout. Content sectioning tags, such as <article>, <aside>, <header>, <footer>, <main>, <section>, headings, etc., and text content tags, such as paragraph, various lists, figures, etc., can be used to partially identify information that they store. There are a few reasons why tags alone are not enough for block identification. First, tags are very generic and only vaguely describe the information they store (e.g., paragraph, header, heading, etc.). Same tags appear multiple times per page, further reducing their uniqueness. Another issue is that there is no penalty in misusing these tags other than the SEO (search engine optimization) impact. For example, lists are commonly used for navigation menus, and images can be used to display backgrounds rather than content-related media. Headings can be misused, negating their importance score (<h1>—Most important, <h6>—Least important). CSS (cascading style sheet) styles also add additional complexity because it is possible to make different types of elements look alike, which would make it impossible to differentiate them using visual cues.

This lack of information is further proven by search engines, which need to know what data is being presented to improve their search results. Although there is no openly available information about how search engines identify information within websites, we can conclude that it is not an easy task since they provide additional tools for webmasters to make this process of identification more accurate. A prime example is schema.org, founded by Google, Microsoft, Yahoo, and Yandex. Its main task is to markup the data presented on a website in a search-engine-friendly form. Applying schema on a website requires developers to label website data based on vocabularies provided by schema.org. Search engines later use this data to provide users with richer search results, which would otherwise be impossible or highly error-prone.

Web page content extraction is a vast problem. One of the more general tasks in web content extraction is eliminating trivial content elements. In most cases, it is achieved by identifying the web page template and gathering meaningful content only [9]. Another more specific case-data extraction form tables or lists presented on the web page [10]. T. Grigalis and A. Čenys proposed a method to extract such records from a web page [11]. However, this approach can be applied only to situations with multiple records presented in a visually structured form.

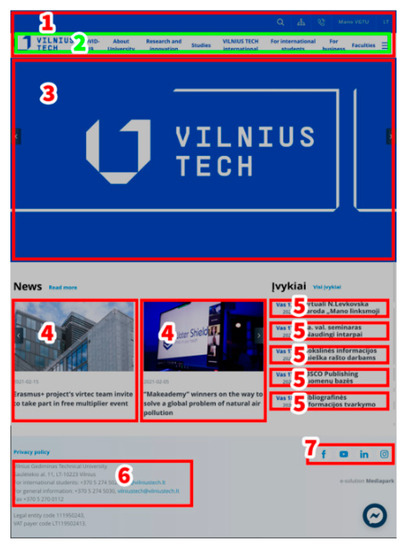

Another web page content extraction direction is web page segmentation. During this process, labels are assigned to content blocks based on their purpose, such as header, menu, main content, etc. Cai, Deng et al. proposed the VIPS (Vision-based Page Segmentation) algorithm for this purpose [12]. Nguyen et al. used the visual information and extracted additional information present in the DOM (document object model) after rendering the page [13]. Burget et al. performed segmentation based on block position within a page, also utilizing some visual cues [14]. Feng et al. offered an interesting approach based on how information is presented from a design perspective. Their algorithm works top-down in multiple steps. First, splitting the content into rows, then dividing them into inner rows and columns using visual separators. Finally, a label assignment task is performed [15]. Bing et al. proposed the approach of segmenting a page using boundaries. Boundaries are applied across the page based on visual cues and later labeled whether the boundary is splitting content or not. The labeling process considers local features of the analyzed boundary and context features based on sibling boundaries [16]. In his thesis, Vargas proposed a Block-o-Matic (BoM) algorithm for web segmentation. It performs segmentation of the page without any prior knowledge, utilizing heuristic rules defined by W3C Web standards [17]. For web page segmentation example, see Figure 1. Only the main blocks are labeled to make this example easier to examine. The main blocks defined within Figure 1 are 1—Header (top section of the web page), 2—Navbar (menu, dedicated for navigation in the web page), 3—Hero (first introductory block on a website, usually containing images, texts, links or forms), 4—Article Preview (title and excerpt of the article), 5—Event (main information on event), 6—Contact Info Block (block to present the main contact details), 7—Social Menu (icons with links to social networks).

Figure 1.

Website content segmentation example.

As noted before, using only HTML structure for data identification can be challenging. That is why often visual representation is used for block identification. One of the most popular algorithms for this is VIPS [18,19,20]. Akpinar et al. took the VIPS algorithm as a base and further improved it by adding HTML5 tags under original tag sets, improved handling of invisible nodes, and ported the algorithm to Java [21]. Zhang et al. noted that although VIPS is a very popular algorithm, it still has some drawbacks. One of the drawbacks is difficulty in setting the value of partition granularity. While using VIPS, this value is different for each segmented page. Zhang et al. tried to solve this by proposing their approach that uses the same granularity value across all segmented pages [22].

On the other hand, blocks that perform the same purpose tend to have a somewhat similar structure. Currently, web development is becoming more and more automated, using various frameworks and content management systems to speed up the development process. Thus, the chance that the same purpose blocks would follow the same or similar structure is even higher. Based on this, the HTML structure can be used for block identification. That way, there is less of a need to analyze block contents—That can be presented in different languages or use different visual styling.

Some techniques analyze multiple pages from the same domain to identify constant and variable information blocks. These can be separate pages, presenting different information or the same page but using a foreign language to display the same data. This approach is not always possible since one-page websites are very popular now, and there is no other page within the same website to compare. Another issue is that different pages within the same domain can use different page layouts or even a different design, which would also hinder block identification utilizing this technique.

2.2. Datasets of Website Content Blocks

Block identification can be completed using machine learning solutions. Machine learning models need various source data for the training process, depending on the data extraction approach. Often researchers use their own datasets to validate their algorithms. Burget et al. collected 100 documents from 10 news websites, then manually assigned nine classes to the visual areas that belong to the article and the tenth class to data that is not relevant [14]. Vargas collected websites based on these categories: Blog, Forum, Picture, Enterprise, Wiki. Each category consisted of 25 websites, and one page from each of the websites was crawled and stored. This dataset included DOM, CSS, and image files [17]. Andrew et al. used a dataset consisting of 53 web pages from 3 domains: Tourism, E-Commerce, and News [19].

There are also a couple of open-source datasets that were used for this purpose. Utiu et al. used multiple datasets, Cleaneval and Dragnet, to benchmark their content extraction method [5]. Deng et al. used the Web Track dataset to compare the proposed VIPS algorithm to the DOMPS algorithm [12]. Bartík used multiple datasets. The first one was WebKB, a dataset consisting of 4518 web pages from the computer science department websites, classified into six categories. Another dataset was manually created from multiple English news websites, manually annotated, and assigned six categories. In total, the second dataset contained almost 500 pages [22]. Kreuzer et al. created two datasets, one based on popular websites and one based on random websites. It was decided to do this because of the anticipation that popular websites would be complex to deal with. That complexity could affect the accuracy of testing results, so the second dataset was created to solve this problem. The labeling process was performed for some blocks on the first and second levels. The first level block used such labels: Header, Footer, Content, Sidebar. Second level blocks were assigned labels, such as Logo, Menu, Title, Link-list, Table, Comments, Ad, Image, Video, Article, Searchbar [23]. These two datasets provided quite a lot of data, but it was still limited because labeling was performed only for two levels, and only 15 block labels were used. Yao et al. used two datasets to perform their research, Dragnet and L3S. The latter consisted of 621 articles from Google News that were manually classified [24].

Generally, web datasets store page source information only, without any additional assets used within a page. Datasets often store a web page’s source code to ensure that the analyzed web page will not change or get deleted and available to use at a later stage. However, these stored pages often consist of only textual content and are pretty old. Thus, they do not represent the current web development trends and can differ structure and code-wise from modern web pages.

Some openly available datasets include only the initial/source data and do not have any extracted data, which would help test the data extraction algorithms’ performance. We did review a few datasets (see Table 1) to see what kind of information is stored within them. Data stored in the dataset is marked with the sign “+”, while missing data is marked with “−”.

Table 1.

Comparison of data stored by datasets.

All except one dataset had the HTML source code available. Some datasets also store extracted data, presented as clean text. Clean text is content stripped of any tags, i.e., only text. These data points are enough for some data extraction applications, for example, context extraction. Additional data needs to be stored to make the dataset more universal.

Two datasets, filled by the same authors, stood out from the others by providing HTML source and HTML DOM code [23]. HTML DOM is HTML code that the browser processed during page load. DOM code can be different from source HTML code due to syntax errors that the browser can automatically correct. It can also contain content that is dynamically generated, for example, by JavaScript. These datasets also store labeled HTML and page assets, such as CSS, JavaScript, and images. These assets can be used to emulate websites in a local environment. If any of these assets are missing, the saved web page’s rendered view will not match the original. Overall this dataset provided quite a lot of source code and assets making it possible to use different data extraction approaches (both context extraction as well as HTML pattern identification). However, some of the potentially useful data was still missing. None of the datasets provide a view of the webpage and its content blocks. This is important as some website analysis solutions are based on optical character recognition (OCR) or use other visual cues for data identification.

3. Proposed Structure of Dataset for Websites and Their Content Blocks

We propose a new dataset structure to store the website’s data and its content blocks. It is based on analysis of the existing website’s content block identification solutions and drawbacks of existing datasets, discussed in the previous section. The proposed dataset structure stores the page source data, code snippets, and screenshots of each HTML node. That makes it possible to use it with different types of data extraction algorithms. It integrates variation possibilities for each block, therefore adds some additional value to the dataset and does it as an option that labeler can choose to ignore.

At first, the idea was to split HTML code into blocks and store them in the database while also labeling them with block type. It soon became apparent that there may be variations of HTML block structure when labeling is performed (see Figure 2). The HTML block size is not strictly defined and can vary based on its visual features or by the decision of the person performing the labeling task. Additional block variation entry was added to account for these situations when more than one adjacent HTML block can be labeled with the same block type. This allowed us to store minimal and extended snippets of the same block. These could later be refined by comparing to other stored blocks or used while estimating block similarity score. Therefore, we provided various data points that can be used based on the specific situation’s problem and needs.

Figure 2.

Dataset data structure simplified diagram.

In the dataset structure, the block types were just general web page elements, such as menu, menu item, article, heading, etc. Currently, there are more than 70 block types, and the list is not final. It can be extended and modified to meet the tendencies of the website development trends.

Block variations can also be used when the same HTML structure can represent multiple block types. For example, an article heading can also act like a link. In a case such as this, two entries will be saved in a dataset as type variations (heading and link).

It is also important in what context hierarchy-wise each of the dataset entries occurs in HTML document. Depending on the hierarchy, block labeling can also change. Thus, each dataset entry also had a parent block associated with it, and the same went for all of the block variations.

Block labeling can be performed either by analyzing code or by evaluating visual features. A screenshot of a web page can be generated if all web page assets are available. However, it might be complicated if some sources are remote—They can become unavailable, modified, etc. Therefore, it was decided to include a node screenshot with each block entry because of the visual approach applications. It simplified the dataset data usage and guaranteed the stability of the dataset.

Some HTML blocks are only visible at a certain screen size. Therefore, we included three screenshots for each HTML block. Selected screen sizes represented desktop, tablet, and mobile viewports. Viewports were chosen based on the currently most popular resolutions for each viewport as listed on statcounter.com—For desktops viewport width was set to 1366 px, for tablets 768 px and for phones 360 px.

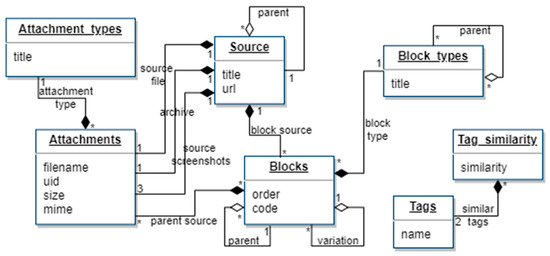

The proposed dataset structure can be seen in Figure 3. A relational database is selected to implement the dataset. The dataset has value when a suitable structure is designed, a large number of records is stored, and a functional user interface is implemented. The dataset is filled with the data at the moment, but to make the stored data flexible and possible to adapt to the user’s needs, it will be available as a service rather than a separate text-based file or an archive of files. Users will be able to generate different data formats and structures adapted to their own needs. It will be possible for the user to specify which data is required and how much data is needed. For example, limit the number of web pages, content block types, etc.

Figure 3.

An example of HTML block variations, where red blocks can be considered as containers and all three cases can be assumed as correct bounds of the block.

Primary data is stored within one table (table “blocks” in Figure 3). It keeps the information about HTML blocks used within the page. This includes hierarchy (block’s parent) and block’s order within the parent block. This table also stores the block’s code, type, whether the block is a variation of another block, and source file id. Each block has a predefined block type assigned to it. All block types are stored in table “block_types”. Block types are also hierarchical, and multiple parent blocks are possible. The pivot table “block_type_hierarchy” allows creating a parent/child block type hierarchy.

The “Attachments” table stores information about various assets used within the dataset, such as source files of HTML pages, source archives (which include images, CSS, scripts, and other assets used by a website). It also stores full screenshots of pages and individual node’s screenshots in three sizes (desktop, tablet, phone). Since each HTML node requires multiple screenshot files, there is also a pivot table called “attachment_block”. Each attachment has a predefined type stored within the “attachment_types” table. The list of attachment types increases the dataset’s extensibility since additional types can be added. It also limits the user to select predefined attachment types only.

Table “sources” stores information about a page used as a source for HTML data. This table allows storing complete HTML and all available assets (images, CSS, JavaScript, etc.) as an archive. This can be useful if the live web page changes, making the original code available. Additionally, a full-page screenshot is also saved. If the data is from an inner page, then the parent page is declared. This makes it possible to have a hierarchical sitemap of the analyzed website.

Tag similarity can be evaluated to determine whether blocks have a similar structure but use different tags to display the same type of information. If blocks are similar, then the same label can be assigned. For this purpose, there are two tables, named: “tags”—Stores HTML tags, “tag_similarity”—Stores an estimated value of how similar two tags are. A higher value corresponds to a higher chance that these tags can substitute one another.

4. Research on the Proposed Dataset Structure Suitability and Its Data Peculiarities

4.1. Dataset Structure Completeness Evaluation

To evaluate the completeness of the proposed data structure, the data needed for existing web page segmentation and labeling solutions were analyzed. Required data were mapped to the proposed dataset’s structure using queries. Table 2 presents web page segmentation solutions that were analyzed in the related work section. Each segmentation method has a summary of what data it used as an input to perform web page segmentation tasks and what output would be produced. Input and output values had to be extracted from the dataset to perform the segmentation task and validate results by comparing them to the dataset data. The possibility to extract the needed data was presented as a query, which can be used to extract the needed data from the proposed dataset structure.

Table 2.

Proposed dataset suitability for existing web page segmentation and labeling solutions.

The comparison revealed all needed data could be extracted from the proposed dataset structure for existing web page segmentation solutions. The option to use a custom aggregation function during dataset data extraction adds additional flexibility. The researcher can get both the minimum or maximum block bound or choose to use the most common block bound. The aggregation function will reduce the number of block variations and will provide only one block bound result. However, researchers can also extract multiple variations of the same block and take them into account during web page segmentation.

Another additional feature of the proposed dataset structure—Block hierarchy. Some of the analyzed web page segmentation solutions take into account the hierarchy of segmented blocks. This hierarchy information is collected/calculated during the segmentation process. The proposed dataset structure stores hierarchy data for each block; therefore, it can be used to reduce the data processing time.

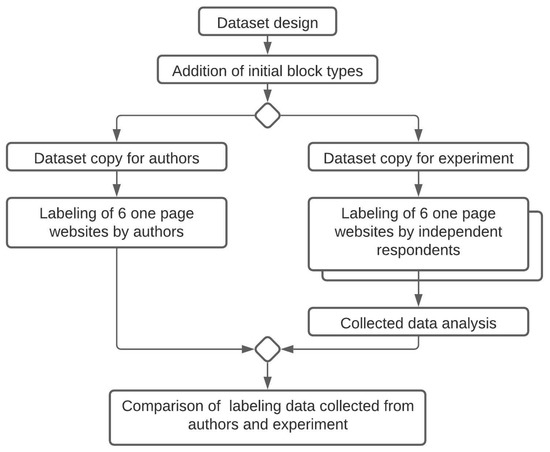

4.2. Research Methodology for Manual Web Page Segmentation

Dataset suitability might be evaluated not only by its data coverage. It is important to understand how new data should be added to the dataset as well as what are the specifics of such data. To account for that, an additional experiment was designed to refine the situations when web page content block variations occur. Simultaneously, the proposed dataset structure suitability to store all the block variations was also evaluated.

Manual web page segmentation and labeling were used to assure real-world websites will be presented in the dataset. Usage of synthetic, auto-generated websites and their blocks would not guarantee natural variety and variations of existing web pages.

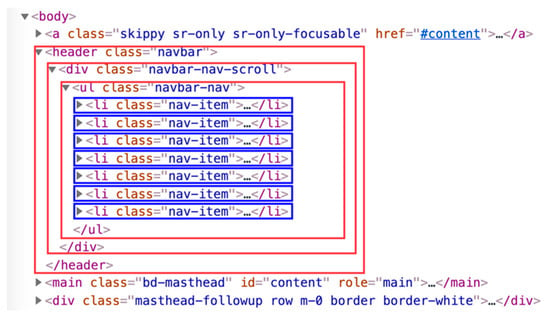

During the experiment, we labeled content blocks of the selected websites. Block labeling data allowed us to evaluate if there were any redundant or missing elements in the proposed dataset schema. Since this kind of evaluation can be influenced by unconscious bias to the designed dataset structure, additional respondents were gathered for the experiment. Six respondents labeled the same set of websites independently from each other. That also allowed us to see if block labels pre-selected by authors would match labels created by respondents (see Figure 4). That helped refine preset labels that were used when filling the dataset with data.

Figure 4.

Basic schema of the experiment for the dataset schema validation.

Respondents were presented with 6 one page websites and were asked to perform a block labeling task. Respondents were of different experience ranging from junior developers to senior developers. One-page websites were chosen because they contain more different types of blocks when compared to regular web pages, which concentrate on one specific topic or purpose per page. Presented websites also covered different information domains: 3 company websites that offered services, one personal website that offered services, one restaurant website, and one website promoting a mobile app. Websites were presented in random order to each of the respondents. When choosing websites for the experiment, it was essential to make sure that they had as many different block types as possible and also used different visual designs to display blocks of the same kind. This allowed testing different approaches to the block labeling process. Some respondents could choose block types based on visual features. Others could select block type based on the information it presents. Finally, there could be situations when both block data and its visual features were used to determine the type.

During the experiment, respondents had to create their own block labels. They were not provided with any predefined labels. Labels created by respondents were stored separately. After the experiment concluded, collected labeling data was compared to the authors labeling data. The complete schema of the experiment is presented in Figure 4.

4.3. Labeling Experiment Results Analysis

In total, during the experiment, 905 individual blocks were labeled. Each labeled page consisted of 82 (average) unique blocks that could be marked. A block’s uniqueness was defined by its purpose. When multiple adjacent blocks of the same type were labeled during the labeling process, only one was counted. As an example, a navigation menu block could be examined. When multiple menu items within the same navigation menu were labeled, only one was counted as a unique block, and others were discarded from experiment statistics. This was done to reduce the number of duplicate labeled blocks present within a page. In an example presented in Figure 5, we can see a menu block, number 3. This menu block consisted of six menu items (home, about, services, portfolio, blog, contact). If we were to compare them, only text and link would differ. Because each menu element serves the same function, all of them can be labeled the same in this example. Additional analysis of these blocks could still be performed later since some metadata may not be visible for the user while still being present in the HTML code. For example, menu items may include some additional attributes that would describe linked content in more detail. This exclusion of duplicate blocks was only done during the experiment to validate the dataset’s structure. When filling the dataset with real data, all labeled blocks are added to have the whole page labeled.

Figure 5.

Example of duplicated block ignorance, when block number 4 represents any menu item of the menu (block No. 3), rather than labeling all menu items.

After analyzing the experiment data, it was noted that users tended to use different names when labeling the same blocks, but at the same time, these block labels tended to be synonymous. For example, block number 1 in the above image (see Figure 5) had these block types assigned by respondents: navbar, header, top navbar. While block number 3 had labels, such as main nav, navbar, main menu, nav, navigation. In both situations, block labels can be treated as synonyms except using the navbar as a label for block number 3, which was not entirely correct, although this label still somewhat correctly represented the block’s purpose. Situations such as this can arise quite often because there is no unanimous agreement on what each website element should be called. One of the reasons is the vast amount of different ways to style websites. The experiment proved the proposed solution is resistant to the problem of multiple labels being assigned to the same block. There is an option in the proposed dataset to store the same block in numerous variations. Consequently, this option has an additional value for website content block analysis. A block’s label synonyms can be analyzed to identify each block type’s best possible title.

During the experiment, multiple situations arose where block variations proved useful. The need for block variations stemmed from different block sizes and different data aggregation levels. Some block variations varied by content length while using the same label. In the image below (see Figure 6), you can see three blocks: number 7 included the text “hello, I’m”, number 8 consisted of the text “Mark Parker”, and number 80 consisted of both of the above. Some respondents marked block 80 as heading or title, including both blocks (7 and 8) at the same time. In contrast, other respondents marked block 7 as pre-title and block 8 as title or heading. The proposed dataset allowed to store labeled data in both situations. This enables mapping block’s relations to each other by purpose(label) or stored content.

Figure 6.

Example of block variations.

The collected data (see Table 3) shows there was no unanimity in the block labeling process, and almost 50% of unique blocks had at least two labeling variations. It also reveals that with a higher count of labeled blocks, variations percentage also increased, proving that there is a lot of room for interpretation when labeling blocks. Based on these results, the option to store block variations in the dataset proved to be essential.

Table 3.

Websites labeling results obtained from respondents during the experiment.

In total, survey respondents added 905 labeled blocks. Out of this number, 383 blocks were unique, which means that respondents marked the same area but attached various labels. Out of 383 unique blocks, 192 of them had only one label attached. This amounts to about 50% of unique blocks. These labels can be treated as well recognizable and unambiguous. Another half of the unique labeled blocks had at least two labels present, about 18% had three or more different labels, ~9% had four or more labels, ~3% had five or more labels, and <1% had six different labels assigned. As six different persons were labeling the same websites, three or more additional labels for the same content block illustrate that 18% of blocks were not clearly presented or had an ambiguous purpose and title.

Collected variations were further analyzed to determine whether those variations were synonymous or not. The similarity of block labels was inspected on a per-block basis. To determine whether block labels were synonymous, they were compared against the authors’ labels assigned to the same block. Cases where block labels were synonymous would prove that authors’ labels were correct. In contrast, nonsynonymous labels would show whether any of the authors’ labels needed to be changed or adjusted to match the specific block type. The number of blocks with nonsynonymous variations varied significantly between different websites presented during the survey. As we noted before, these websites were selected to be similar in terms of content structure. Based on that, we can assume that the presence of these variations depends on the visual styling used by a website. Websites with more complex designs had a greater block variety. On average, each block had 2.3 nonsynonymous variations (0.6186 std.). Most of the time, it was two or three variations per block, but there were also some outliers. Seven blocks had four nonsynonymous variations, which was the most observed during the survey. Not a single block had more than five nonsynonymous variations.

The collected data analysis showed what naming respondents used for block labeling. This was required to see if it was similar (matched 75.41% of the cases) to the one proposed and used during dataset testing by authors. Overall, the labels that respondents used were either the same or synonymous with those used during dataset testing. That proved that the initial block types chosen for block labeling will be acceptable and understandable for other users. Some of the block types collected during the experiment were data-focused. They described the data rather than its purpose. These kinds of labels are not suitable for the dataset since labels should be abstract from the content. For example, for the restaurant website, label names contained dish names rather than being abstract (“egg sandwich” instead of “menu entry” or “dish name/title”). Having block labels tied too closely to the data limits such blocks’ reusability. Data-focused labels can pollute the labeling process, leading to mislabeling blocks of similar purpose that store different data.

5. Conclusions

Since data extraction is an ongoing issue, many new methods have been developed to tackle it. Still, it is hard to compare and test the efficiency of those methods in cases when they use a vastly different approach to data extraction. This comparison issue stems from the datasets that are used to test different data extraction methods. Most of the time, these datasets consist only of the data that is needed for the method that is being tested and do not include any additional data that other data extraction methods may use. We proposed a dataset structure that would provide various data points that can be used to benchmark or develop different types of algorithms and easily compare their performance. After the dataset is filled with a large number of labeled website data and a user interface is implemented, it will be publicly available.

Based on the experiment results, the initial structure of the dataset and labels used to define different content blocks were in line with the expected results. That means that the dataset can be further developed in multiple steps. First, by testing the predefined labels, by performing a similar experiment to the one described in this paper, but this time providing the respondents with labels that they can use during the labeling process. That would show whether these labels need tweaking or new ones need to be added.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.G. and S.R.; methodology, K.G. and S.R.; writing—original draft preparation K.G.; writing—review and editing, S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Griazev, K.; Ramanauskaitė, S. Web mining taxonomy. In 2018 Open Conference of Electrical, Electronic and Information Sciences (eStream), Proceedings of the 2018 Open Conference of Electrical, Electronic and Information Sciences (eStream), Vilnius, Lithuania, 26 April 2018; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, E.; De Meo, P.; Fiumara, G.; Baumgartner, R. Web data extraction, applications and techniques: A survey. Knowl. Based Syst. 2014, 70, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laender, A.H.F.; Ribeiro-Neto, B.A.; Da Silva, A.S.; Teixeira, J.S. A brief survey of web data extraction tools. ACM SIGMOD Rec. 2002, 31, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghuribi, S.M.; Alshomrani, S. A Comprehensive Survey on Web Content Extraction Algorithms and Techniques. In 2013 International Conference on Information Science and Applications (ICISA), Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Information Science and Applications (ICISA), Pattaya, Thailand, 24–26 June 2013; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Utiu, N.; Ionescu, V.-S. Learning Web Content Extraction with DOM Features. In 2018 IEEE 14th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP), Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 14th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 6–8 September 2018; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, S.; Mitra, P.; Giles, C.L. Automatic extraction of informative blocks from webpages. In SAC’05: Proceedings of the 2005 ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, Proceedings of the 2005 ACM Symposium on Applied Computing SAC’05, Santa Fe New, Mexico, 13 March 2005; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2005; p. 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-H.; Ho, J.-M. Discovering informative content blocks from Web documents. In KDD’02: The Eighth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Proceedings of the Eighth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Edmonton Alberta, Canada, 23–26 July 2002; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sleiman, H.A.; Corchuelo, R. TEX: An efficient and effective unsupervised Web information extractor. Knowl. Based Syst. 2013, 39, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán, J.C.; Jiménez, P.; Corchuelo, R. On extracting data from tables that are encoded using HTML. Knowl. Based Syst. 2020, 190, 105157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigalis, T.; Cenys, A. Using XPaths of inbound links to cluster template-generated web pages. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2014, 11, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, J.D.; Dujovne, L.E.; L’Huillier, G. Extracting significant Website Key Objects: A Semantic Web mining approach. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2011, 24, 1532–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Yu, S.; Wen, J.-R.; Ma, W.-Y. VIPS: A Vision-Based Page Segmentation Algorithm; Microsoft Technical Report (MSR-TR-2003-79); Microsoft Corporation: Redmond, WA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, C.K.; Likforman-Sulem, L.; Moissinac, J.-C.; Faure, C.; Lardon, J. Web Document Analysis Based on Visual Segmentation and Page Rendering. In Proceedings of the 10th IAPR International Workshop on Document Analysis Systems, Gold Coast, Australia, 27–29 March 2012; pp. 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burget, R.; Rudolfova, I. Web Page Element Classification Based on Visual Features. In 2009 First Asian Conference on Intelligent Information and Database Systems, Proceedings of the 2009 First Asian Conference on Intelligent Information and Database Systems, Dong Hoi, Vietnam, 1–3 April 2009; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H.; Zhang, W.; Wu, H.; Wang, C.-J. Web Page Segmentation and Its Application for Web Information Crawling. In 2016 IEEE 28th International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 28th International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), San Jose, CA, USA, 6–8 November 2016; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 598–605. [Google Scholar]

- Bing, L.; Guo, R.; Lam, W.; Niu, Z.-Y.; Wang, H. Web page segmentation with structured prediction and its application in web page classification. In Proceedings of the 37th international ACM SIGIR conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, Proceedings of the 37th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, Old Coast Queensland, Australia, 6–11 July 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 767–776. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, A.S. Web page segmentation, evaluation and applications. In Web; Université Pierre et Marie Curie-Paris VI: Paris, France, 2015; NNT: 2015PA066004. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, J.; Ferrari, S.; Maurel, F.; Dias, G.; Giguet, E. Web Page Segmentation for Non Visual Skimming. In Proceedings of the 33rd Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation (PACLIC 33), Hakodate, Japan, 13–15 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppusamy, K.S.; Gnanasekaran, A. A Model for Web Page Usage Mining Based on Segmentation. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2011, 2, 1144–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Bartík, V. Text-Based Web Page Classification with Use of Visual Information. In 2010 International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, Odense, Denmark, 9–11 August 2010; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 416–420. [Google Scholar]

- Akpınar, M.E.; Yesilada, Y. Vision Based Page Segmentation Algorithm: Extended and Perceived Success. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2013, 8295, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Cobia, F. Vision-Based Web Page Block Segmentation and Informative Block Detection. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Joint Conferences on Web Intelligence (WI) and Intelligent Agent Technologies (IAT), Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–20 November 2013; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 3, pp. 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzer, R.; Hage, J.; Feelders, A. A Quantitative Comparison of Semantic Web Page Segmentation Approaches. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2015, 9114, 374–391. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, J.; Zuo, X. A Machine Learning Approach to Webpage Content Extraction; CS229 Machine Learning Final Project; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).