Abstract

Cognitive infocommunications (CogInfoCom) is a young and evolving discipline that is at the crossroads of information and communication technology (ICT) and cognitive sciences with many promising results. The goal of the field is to provide insights into how human cognitive capabilities can be merged and extended with the cognitive capabilities of the digital devices surrounding us, with the goal of enabling more seamless interactions between humans and artificially cognitive agents. Results in the field have already led to the appearance of numerous CogInfoCom-based technological innovations. For example, the field has led to a better understanding of how humans can learn more effectively, and the development of new kinds of learning environment have followed accordingly. The goal of this paper is to summarize some of the most recent results in CogInfoCom and to introduce important research trends, developments and innovations that play a key role in understanding and supporting the merging of cognitive processes with ICT.

1. Introduction

Cognitive infocommunication (CogInfoCom) is an interdisciplinary field of science created by Hungarian researchers who have recognized that human relationships with information technology, robotics and communication devices, “smart” homes, cities and cars will change significantly in the near future. In addition to all this, the generation that is now growing up using information technology (IT) tools, smartphones, display a different development of certain areas of their brains, which can mean not only biological, physiological, but also mental change. The basic definition was formulated by P. Baranyi and A. Csapo [1] of the field of science, while it was extended and finalized by P. Baranyi and A. Csapo also [2] and G. Sallai [3]:

“Cognitive infocommunications (CogInfoCom) investigates the link between the research areas of infocommunications and the cognitive sciences, as well as the various engineering applications which have emerged as the synergic combination of these sciences. The primary goal of CogInfoCom is to provide a systematic view of how cognitive processes can co-evolve with infocommunications devices so that the capabilities of the human brain may not only be extended through these devices, irrespective of geographical distance, but may also interact with the capabilities of any artificially cognitive system. This merging and extension of cognitive capabilities is targeted towards engineering applications in which artificial and/or natural cognitive systems are enabled to work together more effectively.”

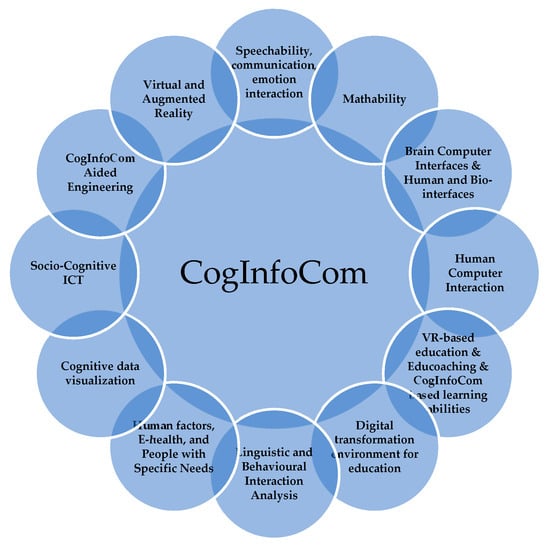

The above definition can be summarized as CogInfoCom, a science that studies the interaction between information technology and people, which examines the possibility of creating new cognitive communication channels in addition to the topic of conventional human–machine relationships; and it can also be seen as a synergy of the research topics illustrated in Figure 1. The areas listed in the figure can provide the creation of complex sensory IT systems that can be used to make human–machine communication more efficient and new procedures, mathematical modelling, learning techniques and related behavioural research help to better understand perceptual and brain processes also.

Figure 1.

The main related topics of cognitive infocommunication (CogInfoCom).

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of human–computer interaction (HCI) and virtual reality (VR) research fields in CogInfoCom during the eight-year period from 2012 to 2020 based on the International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications and its special issues. These works were classified in terms of application areas into two categories: (1) human–computer interaction and (2) virtual reality.

2. Overview of International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom) and Its Special Issues

Together with the definition of the field, the 1st International Workshop on Cognitive Infocommunications on CogInfoCom was held at the University of Tokyo in 2010, followed by the International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications, which has been held every year to this day. The conference series has been published in several countries and cities in Europe over the past 9 years, with more than 1000 studies published and thousands of references received until Q1 2021, as well as indexed by scientifically relevant databases such as IEEE Xplore, Scopus or Web of Science. The special feature of the conference series is that for several years, the majority of the presentations have been shown in 3D, virtual spaces supported and implemented by the MaxWhere platform. (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The 11th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications conference presentations were seen by participants in 3D virtual space.

Moreover, the following journal special issues (Table 1) have appeared on CogInfoCom-related topics.

Table 1.

Journal special issues related to CogInfoCom topics.

3. Related Papers

3.1. Human–Computer Interaction (HCI)

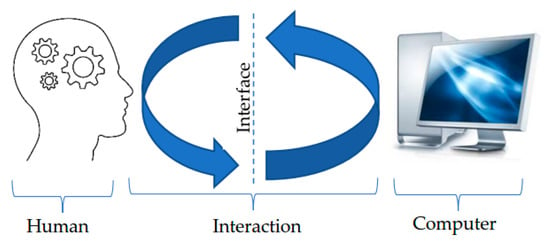

HCI, also called human–machine interaction (HMI) refers to the interfaces between computer technology and people as users (Figure 3). The aim of this section is to provide an overview of HCI fields which were published on International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom) and its special issues. For this overview, two search engines were used to collect papers over the specified time period that were selected using the following boolean string: ((Human Computer Interaction OR HCI) OR (Human Machine Interaction OR HMI) OR (Brain Computer Interface OR BCI) OR Eye Tracking OR Gaze Tracking OR Gesture Control). 2012–2020 was chosen as the timeline for this literature review, as the publications of the conference series related to the field of science and its special issue can be found in the major databases in this time band until 2021 Q1. A further condition was formulated as an additional criterion: (Citations number ≥ 10 in IEEE Xplore OR in Scopus until 2021 Q1).

Figure 3.

High-level diagram of a typical human–computer interaction (HCI).

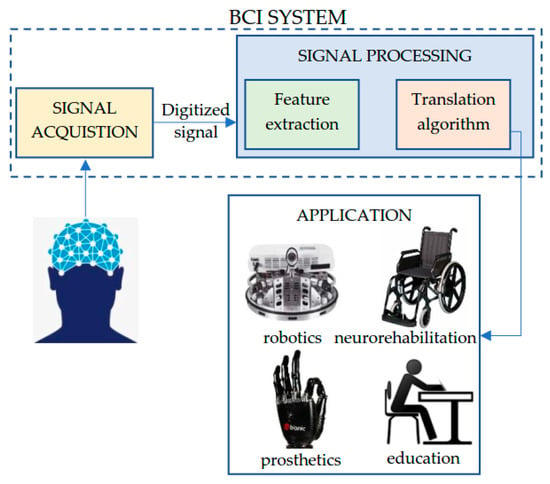

According to L. Izso [4], complex HCI-based support systems implemented in the field of CogInfoCom can improve the quality of life of patients with cognitive disorders and related disabilities. Examples of such complex systems include brain–computer interfaces (BCIs), which allow the implementation of an alternative communication channel between the computer and the human brain (Figure 4). In the research by J. Katona et al. [5], human–robot interaction (HRI) was developed based on a cost-effective BCI system, where the speed control of a mobile robot was implemented, and its effectiveness was tested in a real environment involving test subjects. The results of development and research can contribute, for example, to the development of a brainwave-controlled wheelchair for a person with reduced mobility and to increase its operational efficiency. M. Tariq et al. [6] aimed to improve the quality of life of patients with impaired motor functions by implementing a BCI-based neurorehabilitation system mainly focusing on the quantification and investment of mu-beta event-related desynchronization (ERD) and event-related synchronization (ERS). In addition, the results obtained can be applied well in robotics during the implementation of the movement of a robot arm or leg. As described by J. Katona [7,8], BCI systems can also play a significant role in increasing the effectiveness of learning by monitoring attention as a key cognitive process and can also appear as a kind of learning support system.

Figure 4.

High-level block diagram of a typical brain–computer interface (BCI).

Human–computer interactions are significantly influenced by the means of communication used to control the computer. Systems based on gesture control or eye movement tracking may allow some functions of the mouse or keyboard to be triggered or replaced. G. Sziladi et al [9] compared the traditional computer mouse and its handling with a cost-effective hand gesture detection and processing system called Leap Motion (Figure 5a) by analyzing the movement of a computer mouse cursor. Although the gesture control used showed more inaccurate and uncertain mouse cursor movement, the results obtained may be key in performing a task that requires less fine movement, where the use of gesture control systems may be beneficial to the user. In addition to the cost-effective gesture controls used by G. Sziladi et al [9], other devices with similar characteristics are available. The aim of the research by B.A. Csapo [10] is to examine the effectiveness of an armband called Myo (Figure 5b) and to discuss how visually impaired people can use this device as a kind of support tool in their everyday lives. The results obtained show that the device is currently only partially suitable for performing continuous search tasks and further calibration methodological improvements are needed for more efficient operation.

Figure 5.

Leap Motion controller (a) and Myo armband (b). [9].

J. Zsolt et al. [11] described a self-developed system for replacing computer input peripherals (keyboard and mouse) using eye path tracking. In some cases, gaze control can be much more informative than simple mouse movement, as not only the path of the gaze but also the emotional factors become readable in this way. A. Torok et al. [12] analyzed the technique of reading a colorful early map by examining eye movement parameters, where it was observed that test subjects spend more time studying the cluttered area, but this effect can be related to eccentricity. The experiences and the obtained results can contribute to the design and development of modern user interfaces. K. Hercegfi et al. [13] present the usability testing of a semi-intelligent agent called the Emotional Display Object of the Virtual Collaboration Arena (VirCA) based on interviews and eye-tracking. The results show that selective attention is quite strong and during new tasks the test subjects focus only on the most important points of the screen for the solution and for the less important parts they do not notice the changes during the observation. A. Kovari et al. [14] examine the forms and effectiveness of the debugging phase of software development through eye movement tracking with the involvement of test subjects. After examining the results, it can be seen that test subjects who made many minor modifications as well as more frequent compilations and runs with less efficiency and more time required, discovered and corrected more hidden errors in the source code than those who placed more emphasis on interpretation, and they used the ability to compile and run the application less often. T. Ujbanyi et al. [15] examine eye movement parameters in the context of the acquisition of IT skills. The results obtained show that differences in gaze movement can be detected in students with different levels of knowledge, from which conclusions can be stated and related to effectiveness, success or failure of learning. Figure 6 shows two cost-effective and reliable eye tracker devices that were used in the reviewed literatures.

Figure 6.

The Eye Tribe tracker [15] (a), the Gazepoint GP3 Eye tracker [14] (b).

A. Garai et al. [16] examine HMI for body-sensors that collect and store health data about its user and extends an adaptive eHealth content management methodology. Such information and telecommunication systems make it possible to monitor the patient’s live data away from classical medical institutions. B. Solvang et al. [17] present a new architecture for human–machine and machine-to-machine communication and control that facilitates communication between old and new devices and equipment and improves human–machine interaction through more efficient integration. some sub-units can make better use of their capabilities.

Table 2 summarizes the year of reviewed publications of this section, the area of applicability of the obtained results, and the applied HCI/HMI components.

Table 2.

The area of applicability of the results of the reviewed literature and the applied human–computer interaction/human–machine interaction (HCI/HMI) components.

With the development of technology, it is assumed by A. Torok [18] that the efficiency and reliability of HCI-based systems can be improved, but in order to be able to design and implement highly efficient, understandable and manageable HCI-based systems, we need to know human behavior, human limits, human needs, and human cognition. In addition, I. Siegert et al. [19] mentioned that we need to pay attention to the overlapping speech effect present in HCI communication and also make recommendations to avoid this.

3.2. Virtual Reality (VR)

VR is a collective name for specialized, widely used electronic technologies designed to create a virtual environment in which the user can feel as if they exist in physical reality. The aim of this section is to provide an overview of VR-based education and educoaching and CogInfoCom-based learning abilities which were published by the International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom) and its special issues. For this overview, two search engines were used to collect papers over the specified time period that were selected using the following boolean string: ((Virtual Reality OR VR) AND Education OR Learning). We chose 2012–2020 as the timeline for this literature review, as the publications of the conference series related to the field of science and its special issue can be found in the major databases in this time band until 2021 Q1. Further condition was formulated as an additional criterion: (Citations number ≥10 in IEEE Xplore OR in Scopus until 2021 Q1).

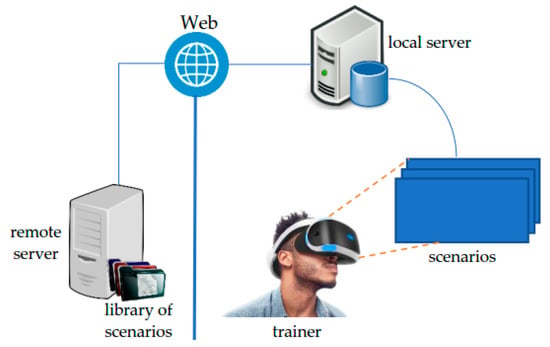

VR tools can provide both professionals and students with cost-effective and risk-free practice areas that can help plan, implement, and evaluate certain processes, and even provide remote connectivity. E. Markopoulos et al. [20] describe a prototype of a cost-effective and portable VR-based system that, after a successful testing phase, will provide seafarers with training and practice opportunities in virtual reality in either a home or office environment. M. Al-Adawi et al. [21] demonstrate a fire safety application-based VR also that can be used by both professionals and students for fire protection exercises, contributing to the development and testing of the most effective firefighting techniques for different types of fires. As a summary of the processed articles, it can be stated that professionals or students, regardless of the physical work areas, can learn the tasks related to their work effectively without physical dangers, and can react to reactions to various dangerous situations and prepare for unexpected situations. Figure 7 shows the tools and their connections required for producing VR training scenarios.

Figure 7.

Tools and their connections for producing virtual reality (VR) training scenarios.

S. Korečko et al. [22] examine the evaluation of cognitive functions of the visual space and the possibilities of teaching in a virtual environment. The study used cognitive tests, EEG measurements, cognitively stimulating tasks and two VR games in an immersive 3D virtual environment-based CAVE (Cave Automatic Virtual Environment) system. The obtained results can contribute to the comprehensive study of various cognitive processes in the field of cognitive research.

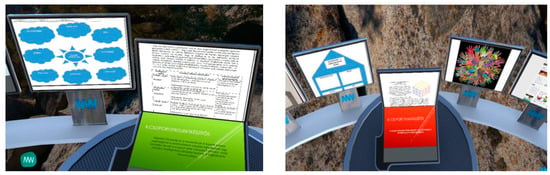

In the last decade, distance learning, also known as e-learning, is increasingly emerging in the field of higher education, in which teachers make the most static content available. Today, however, remote and virtual laboratories are gaining ground, especially in the engineering disciplines. T. Budai et al. [23] examine the possibilities of developing such laboratory systems and current solutions, focusing primarily on higher education, stating that with the help of CogInfoCom we can explore the important factors that can be used to increase the efficiency of such systems. G. Csapo [24] presents a 3D virtual environment implemented in MaxWhere, where students were provided with all the information and resources that could support the effective mastery of spreadsheet programming, computer problem solving, database management, and building algorithms. In an electrical engineering course, it is quite difficult for students to teach the structure and operation of various electrical machines and drives with 2D illustrations, while using 3D, animated content can make this process much more efficient. Z. Kvasznicza [25] focuses on more efficient training of asynchronous machines in a 3D VR space and emphasizes that devices and equipment that are difficult and expensive to obtain in physical reality can be produced easily and cost-effectively in a virtual environment. Computer science requires a kind of inventive thinking, so we should strive to develop student creativity and innovative thinking in university education as well. Based on G. Bujdoso’s [26] results, it can be stated that with the help of virtual reality, these abilities can be significantly improved. The study was conducted in a so-called immersive VR (iVR) system developed on the MaxWhere platform, which offers a wide range of opportunities for user interaction and provides tools to trigger cognitive processes that can contribute to the development of inventive thinking. According to A. Kovari [27], by supporting IT tools and technologies based on CogInfoCom, such as 3D VR learning environments, traditional education can be expanded and made more efficient, resulting in increased learning efficiency, motivation and creativity. A. Csapo et al. [28] also examine VR environments from a psychological perspective, analyzing the impact of these types of environment on the formation of new memories, and also makes recommendations for the development of effective AI-enhanced CogInfoCom systems. The results of the study show that the elements presented in the VR environment are stored more deeply in human memory, which can ultimately result in a more efficient retrieval and learning process. Figure 8 shows two study “desks” with task descriptions, helping the template and study.

Figure 8.

Two study “desks” with task description, helping the template and study.

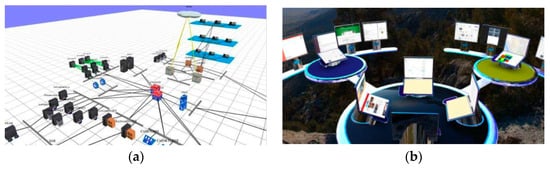

The possibilities of the 3D VR environment are not limited to education and learning but can even make the planning and administration of education more efficient. I. Horvath [29] emphasizes that the increasing use of VR and augmented reality (AR) technologies in the field of education can significantly contribute to the development of new learner-centred teaching and learning strategies and methods, as a result of which an innovative educational ecosystem can be created. The results of the experiment presented in the study show that in 3D space implemented in the MaxWhere environment, digital instructor workflows required 37–64% fewer user and 72% less machine operations compared to those performed on traditional 2D interfaces. This can mean that MaxWhere, as an educational platform, offers benefits not only to students but also to faculty. A. D. Kovacs et al. [30] provide an example of this through the self-assessment workflow associated with institutional accreditation, which has shown that such a workflow can reduce it by up to 25% due to more effective collaboration, increased work flexibility, and easier organization. work time requirement. B. Lampert et al. [31] analyze the processes of sharing workflows, descriptions, digital content and technological tools, and the defined results can be well applied in the field of workflow sharing. The results of the applied tests show that in the MaxWhere 3D environment, users were able to execute the required workflows at least 50% faster compared to other traditional 2D environments. Figure 9 shows two 3D representation of workflows.

Figure 9.

3D representation of the workflow [31] (a) and MaxWhere 3D employees’ workspace [31] (b).

CogInfoCom also examines the interaction between thinking and social processes and extends it to the virtual space. I. L. Komlosi et al. [32] examine post-Y-generation information processing properties and characteristics in the context of knowledge management. People born in the digital age and socialized in culture are much more able to develop knowledge transfer and communication interaction between human and non-human agents. The study emphasizes that the transformation of linear information processing that has developed in the past is expected in the future. V. Kovecses-Gosi [33] also emphasizes the importance of introducing new teaching methods and exploiting the potential of 3D virtual spaces in the field of education and presents how the lesson built on the improvement of different intelligence levels can be accomplished. I. Horvath [34] describes an edu-coaching teaching method supported by ICT tools that fit into the digital-based life of Generation Z students based on a special interrogatory technique. Based on the defined results, the real environment of education that requires expensive engineering tools can be replaced well by a properly constructed and simulated 3D virtual environment. I. Horvath [34,35] emphasizes that environments designed in this way can revolutionize engineering education, as they do not necessarily require expensive physical equipment, and computer networks allow physically distant teachers and students to interact effectively in such environments, with which education is ultimately, in addition to its cost-effectiveness, student motivation may also increase.

It is essential that immersive VR environments effectively simulate and track different forms of movement and make them more effective through exercises and training, improve route search and orientation as cognitive processes, and significantly enhance lifelike audio-visual elements in addition to illustrating well-chosen visual elements. the effectiveness of immersive VR “being there”.

D. Edler et al. [36] use an example of the transformation and development of a post-industrial area to show how it is possible to increase the user experience of a 3D environment by supporting the Unreal Engine 4 game engine. In addition, he emphasizes that the use of immersive VR-based technology can enrich us with additional extremely real experiences that are not experienced during a visit to a real physical area and can appear as a kind of design support option in the field of landscape architecture and research. C. Boletsis et al. [37] present and analyze the user experiences provided by contemporary and now widespread VR movement techniques through empirical research. The results of the study show that users delve into virtual space mostly through a walking-in place, but this also means the greatest psychophysical strain on them. The VR movement supported by different controllers or joysticks showed ease of use; however, visual jumps made with these devices very easily break the feeling of immersion. F. Hruby et al. [38] examine the importance of scaling and makes recommendations, as it is extremely important for immersive VR systems to create a sense of reality, so mapping different geographical environments in great detail is of paramount importance. Based on the results of E. I. Lokka et al. [39], it can be stated that the individual cognitive training developed during the research, optimized for route learning, can counterbalance the decline in spatial memory associated with older age and the associated route search and orientation difficulties. F. Hruby [40] attaches great importance to the study of multisensory experiences in order to maximize the “being there” presence in the VR environment and, as an alternative, analyzes the Geovisualization Immersive Environment (GeoIVE) to investigate the potential of sound. Table 3 shows the summary on applied virtual reality applications and environments.

Table 3.

The area of applicability of the results of the reviewed literature and the applied virtual reality (VR) application/environment.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

From 2012 to 2020, the study provided a brief overview of the results published and most cited in the two most important research areas of the CogInfoCom discipline based on the International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications and its special issues.

One of the most important research areas of CogInfoCom is the development of complex HCI-based systems and the study of their efficiency. In summarizing the results, it was revealed that EEG-based BCI, gesture control, and eye/gaze tacking appeared as the most frequently used alternative communication tools. The results presented in the field of BCI may support the development of communication channels between the human brain and the computer that can be used in the following areas: HRI, robotics, velocity control, medical signal detection, neurophysiology, patient rehabilitation and education. The results summarized in the field of gesture control complement or extend the possibilities of developing human-computer interactions and can also be used in areas such as controlling systems, haptic interfaces, image motion analysis and motion or auditory control. The results explored and summarized in the field of eye/gaze tracking can contribute to the development of areas such as emotional recognition, iris detection, visualization, user interfaces, task analysis, cognition, HRI, virtual reality and agents, programming, computer network and education.

Based on the reviewed literature, it can be stated that more cost-effective and reliable HCI-based systems are increasingly appearing and becoming part of our everyday lives. For people with disabilities, such systems will increasingly be able to provide a full life in the future, significantly improving their quality of life. In addition, the use of BCI, eye-tracking, or gesture control systems is expected to expand and develop traditional communication between humans and robots, as well as various devices and equipment. Moreover, the spread of BCI systems can be predicted to increase the learning efficiency of children with learning difficulties and it is also possible to compile adaptive learning materials that can describe the learning material to be acquired in a dynamic way, taking into account the current state of concentration of the students, as opposed to a traditional book, which does all this in a static way.

Another major area of research is a special, widely applicable electronic technology, the VR, which is primarily used to create a virtual environment in which the user can perform their tasks as if they were in a physical reality. Depending on the goals, several softwares are used to create the virtual environment. One such goal may be to provide users with an area where they can practice trying new techniques without physical hazards. To achieve this goal, for example, MarSEVR (Maritime Safety Education with VR Technology) or Electric Cabin Fire Simulation are used, which can be used in areas such as computer-based training, marine engineering, ergonomics, maritime safety training, simulation, fire safety or industrial training. Another priority could be to increase the efficiency of learning and the organization of education, and to examine the interaction between thinking and social processes, extended to the virtual space. To achieve such goals, for example, the MaxWhere 3D VR Framework is used, which can be used in other areas such as simulation, informatics and AI-enhanced CogInfoCom.

Based on the reviewed literature, it can be stated that in the future we will be increasingly able to create the feeling of “being there” by utilizing all our senses more effectively. Immersive 3D VR will be a key application in real-life simulation of environments free of physical hazards, where professionals or students can practice, master, and develop new techniques in the event of a potential emergency. In addition, 3D-based virtual environments will be of paramount importance in the field of education for the development of more effective learning materials, and the purchase of expensive tools and equipment for educational purposes will be avoided as we will be able to simulate and illustrate them more effectively. In addition, the use of virtual reality can better develop students’ creative and innovative thinking, as well as predict a significant improvement in motivation. In addition to teaching and learning, 3D VR environments will be able to effectively support and accelerate the planning and administration of education. For example, the students of the future will not have to gather in one physical place to listen to a lecture, for example, but can do so from anywhere in the world. Overall, the use of 3D VR environments will create an innovative educational ecosystem, as opposed to the now obsolete traditional 2D-based interfaces, which can be assumed to be continuously replaced.

In the future, the fusion of HCI-based systems and 3D VR environments can complement each other to raise the level of utilization, development and support of human cognitive abilities, leading to more creative and innovative ways of thinking and knowledge acquisition expected according to the abilities of the individual.

With the continuous development of technology, the implementation of increasingly reliable and cost-effective CogInfoCom-based systems can be assumed. However, we must also take into account that the development, operation and maintenance of increasingly complex systems will present new challenges, and that people as users are much slower to adapt to innovation and that the introduction of a new interface can only be effective if the limitations are well known.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baranyi, P.; Csapo, A. Cognitive Infocommunications: Coginfocom. In Proceedings of the 2010 11th International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Informatics (CINTI), Budapest, Hungary, 18–20 November 2010; pp. 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Baranyi, P.; Csapó, Á. Definition and Synergies of Cognitive Infocommunications. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2012, 9, 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sallai, G. The Cradle of Cognitive Infocommunications. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2012, 9, 171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Izsó, L. The Significance of Cognitive Infocommunications in Developing Assistive Technologies for People with Non-Standard Cognitive Characteristics: CogInfoCom for People with Non-Standard Cognitive Characteristics. In Proceedings of the 2015 6th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Gyor, Hungary, 19–21 October 2015; pp. 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Katona, J.; Ujbanyi, T.; Sziladi, G.; Kovari, A. Speed Control of Festo Robotino Mobile Robot Using NeuroSky MindWave EEG Headset Based Brain-Computer Interface. In Proceedings of the 2016 7th IEEE international conference on cognitive infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Wrocław, Poland, 16–18 October 2016; pp. 251–256. [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, M.; Uhlenberg, L.; Trivailo, P.; Munir, K.S.; Simic, M. Mu-Beta Rhythm ERD/ERS Quantification for Foot Motor Execution and Imagery Tasks in BCI Applications. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Debrecen, Hungary, 11–14 September 2017; pp. 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Katona, J.; Kovari, A. Examining the Learning Efficiency by a Brain-Computer Interface System. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2018, 15, 251–280. [Google Scholar]

- Katona, J.; Kovari, A. The Evaluation of BCI and PEBL-Based Attention Tests. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2018, 15, 225–249. [Google Scholar]

- Sziladi, G.; Ujbanyi, T.; Katona, J.; Kovari, A. The Analysis of Hand Gesture Based Cursor Position Control during Solve an IT Related Task. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Debrecen, Hungary, 11–14 September 2017; pp. 413–418. [Google Scholar]

- Csapo, A.B.; Nagy, H.; Kristjánsson, Á.; Wersényi, G. Evaluation of Human-Myo Gesture Control Capabilities in Continuous Search and Select Operations. In Proceedings of the 2016 7th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Wrocław, Poland, 16–18 October 2016; pp. 415–420. [Google Scholar]

- Zsolt, J.; Levente, H. Improving Human-Computer Interaction by Gaze Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Kosice, Slovakia, 2–5 December 2010; pp. 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Török, Á.; Török, Z.G.; Tölgyesi, B. Cluttered Centres: Interaction between Eccentricity and Clutter in Attracting Visual Attention of Readers of a 16th Century Map. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Debrecen, Hungary, 11–14 September 2017; pp. 433–438. [Google Scholar]

- Hercegfi, K.; Komlódi, A.; Köles, M.; Tóvölgyi, S. Eye-Tracking-Based Wizard-of-Oz Usability Evaluation of an Emotional Display Agent Integrated to a Virtual Environment. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2019, 16, 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kovari, A.; Katona, J.; Costescu, C. Evaluation of Eye-Movement Metrics in a Software Debbuging Task Using Gp3 Eye Tracker. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2020, 17, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujbanyi, T.; Katona, J.; Sziladi, G.; Kovari, A. Eye-Tracking Analysis of Computer Networks Exam Question besides Different Skilled Groups. In Proceedings of the 2016 7th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Wrocław, Poland, 16–18 October 2016; pp. 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Garai, Á.; Attila, A.; Péntek, I. Cognitive Telemedicine IoT Technology for Dynamically Adaptive EHealth Content Management Reference Framework Embedded in Cloud Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2016 7th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Wrocław, Poland, 16–18 October 2016; pp. 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Solvang, B.; Sziebig, G.; Korondi, P. Shop-Floor Architecture for Effective Human-Machine and Inter-Machine Interaction. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2012, 9, 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Torok, A. From Human-Computer Interaction to Cognitive Infocommunications: A Cognitive Science Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2016 7th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Wrocław, Poland, 16–18 October 2016; pp. 433–438. [Google Scholar]

- Siegert, I.; Bock, R.; Wendemuth, A.; Vlasenko, B.; Ohnemus, K. Overlapping Speech, Utterance Duration and Affective Content in HHI and HCI-An Comparison. In Proceedings of the 2015 6th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Gyor, Hungary, 19–21 October 2015; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Markopoulos, E.; Lauronen, J.; Luimula, M.; Lehto, P.; Laukkanen, S. Maritime Safety Education with VR Technology (MarSEVR). In Proceedings of the 2019 10th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Naples, Italy, 23–25 October 2019; pp. 283–288. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Adawi, M.; Luimula, M. Demo Paper: Virtual Reality in Fire Safety–Electric Cabin Fire Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2019 10th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Naples, Italy, 23–25 October 2019; pp. 551–552. [Google Scholar]

- Korečko, Š.; Hudák, M.; Sobota, B.; Marko, M.; Cimrová, B.; Farkaš, I.; Rosipal, R. Assessment and Training of Visuospatial Cognitive Functions in Virtual Reality: Proposal and Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Budapest, Hungary, 22–24 August 2018; pp. 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Budai, T.; Kuczmann, M. Towards a Modern, Integrated Virtual Laboratory System. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2018, 15, 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Csapó, G. Sprego Virtual Collaboration Space. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Debrecen, Hungary, 11–14 September 2017; pp. 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kvasznicza, Z. Teaching Electrical Machines in a 3D Virtual Space. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Debrecen, Hungary, 11–14 September 2017; pp. 385–388. [Google Scholar]

- Bujdosó, G.; Novac, O.C.; Szimkovics, T. Developing Cognitive Processes for Improving Inventive Thinking in System Development Using a Collaborative Virtual Reality System. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th IEEE international conference on cognitive infocommunications (coginfocom), Debrecen, Hungary, 11–14 September 2017; pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kovari, A. CogInfoCom Supported Education: A Review of CogInfoCom Based Conference Papers. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Budapest, Hungary, 22–24 August 2018; pp. 000233–000236. [Google Scholar]

- Csapo, A.; Horváth, I.; Galambos, P.; Baranyi, P. VR as a Medium of Communication: From Memory Palaces to Comprehensive Memory Management. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Budapest, Hungary, 22–24 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth, I. Evolution of Teaching Roles and Tasks in VR/AR-Based Education. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Budapest, Hungary, 22–24 August 2018; pp. 355–360. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, A.D.; Kvasznicza, Z. Use of 3D VR Environment for Educational Administration Efficiency Purposes. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Budapest, Hungary, 22–24 August 2018; pp. 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert, B.; Pongrácz, A.; Sipos, J.; Vehrer, A.; Horvath, I. MaxWhere VR-Learning Improves Effectiveness over Clasiccal Tools of e-Learning. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2018, 15, 125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Komlósi, L.I.; Waldbuesser, P. The Cognitive Entity Generation: Emergent Properties in Social Cognition. In Proceedings of the 2015 6th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Gyor, Hungary, 19–21 October 2015; pp. 439–442. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses-Gosi, V. Cooperative Learning in VR Environment. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2018, 15, 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth, I. The IT Device Demand of the Edu-Coaching Method in the Higher Education of Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Debrecen, Hungary, 11–14 September 2017; pp. 379–384. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, I. Innovative Engineering Education in the Cooperative VR Environment. In Proceedings of the 2016 7th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Wrocław, Poland, 16–18 October 2016; pp. 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Edler, D.; Keil, J.; Wiedenlübbert, T.; Sossna, M.; Kühne, O.; Dickmann, F. Immersive VR Experience of Redeveloped Post-Industrial Sites: The Example of “Zeche Holland” in Bochum-Wattenscheid. KN-J. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. 2019, 69, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boletsis, C.; Cedergren, J.E. VR Locomotion in the New Era of Virtual Reality: An Empirical Comparison of Prevalent Techniques. Adv. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruby, F.; Castellanos, I.; Ressl, R. Cartographic Scale in Immersive Virtual Environments. KN-J. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokka, I.E.; Çöltekin, A.; Wiener, J.; Fabrikant, S.I.; Röcke, C. Virtual Environments as Memory Training Devices in Navigational Tasks for Older Adults. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hruby, F. The Sound of Being There: Audiovisual Cartography with Immersive Virtual Environments. KN-J. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. 2019, 69, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).