Abstract

This research aims to examine the role and emerging trends of critical thinking within tertiary education through a bibliometric analysis, with particular emphasis on disparities among countries with differing Human Development Index (HDI) levels. The analysis seeks to identify thematic associations related to critical thinking across nations at various stages of development, as well as to explore the educational methods and strategies employed regionally to cultivate critical thinking skills. The findings highlight notable contrasts between developed and developing nations, especially in terms of educational strategies, dominant academic discourses, and region-specific research priorities.

1. Introduction

The development and application of critical thinking have become fundamental to advancing educational, scientific, and personal development, particularly within higher education. In a global educational landscape marked by differing levels of human development, diverse approaches and pedagogical strategies have emerged to foster critical thinking. However, significant discrepancies exist among countries in the structure and content of tertiary education systems and the thematic focus of academic research—all of which influence how critical thinking is taught and practiced (Nuryana et al., 2024). In recent decades, critical thinking has been in a focus in the field of pedagogical and psychological research due to its indispensable role in solving complex problems, making informed decisions, and fostering civic responsibility (Angwaomaodoko, 2024). Tertiary education is not solely concerned with the transmission of knowledge but increasingly with equipping students with the analytical skills necessary to critically engage with the world and form independent, well-founded perspectives. However, the development of critical thinking skills does not occur uniformly across countries. The methods and procedures employed to promote these skills vary significantly, depending on the level of human development within the respective educational systems (Yücel, 2025). This study seeks to map the global trends in the advancement of critical thinking and its role in tertiary education across countries at different stages of human development. Particular emphasis is placed on the interplay between education and academic research, as well as on the analysis of strategies and methodologies that support the development of critical thinking in the international arena. The analysis involves a comparative examination of educational systems and research trends across various nations, with the aim of identifying the latest scientific directions and future development opportunities in this field using bibliometric data. Bibliometric analysis enables the tracking of scholarly publications and research trends over time, and provides insights into the extent and manner in which critical thinking is integrated into the education systems around the world.

An approach based on varying levels of development provides valuable insight into how the maturity of educational systems influences the dissemination and development of critical thinking. While more developed countries have established extensive and in-depth research initiatives and educational programs in this area, in developing nations, educational reforms and international collaborations play a pivotal role in advancing critical thinking (Passas, 2024). This research, therefore, aims not only to enrich academic discourse but also to offer practical recommendations for educational policy across different national contexts.

2. Theoretical Framework

This section aims to present the methods for developing critical thinking, its role within tertiary education, and the global disparities observable through the lens of the Human Development Index (HDI). The first sub-section discusses strategies for fostering critical thinking, emphasizing diverse pedagogical approaches and tools. This is followed by an exploration of the relationship between critical thinking and tertiary education, focusing on the university environment’s contribution to nurturing this skill. The third sub-section analyzes global differences based on HDI, comparing the varied practices and challenges encountered in developed versus developing countries. Finally, the section outlines the methodology and emerging trends in bibliometric analysis, which serve to identify the main directions of scholarly research and the evolving global discourse surrounding critical thinking.

2.1. Methods for Developing Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is a cognitive skill that enables individuals to reflectively, logically, and objectively evaluate information, assess the validity of arguments and counterarguments, and make well-founded decisions (Rusmin et al., 2024). Tertiary education plays a pivotal role in cultivating this skill, as university students are expected not only to acquire new knowledge but also to critically analyze and apply it. Below, the most commonly applied methods for developing critical thinking are presented, all of which are gaining increasing importance in modern educational systems (J. M. Kumar, 2024). The first noteworthy method is problem-based learning (PBL). PBL is a pedagogical approach in which students are confronted with a specific problem and work toward a solution through independent research, analysis, and group discussion. This method not only enhances critical thinking but also fosters independent learning, creative problem-solving, and collaboration skills (Abidin & Sulaiman, 2024). Another important approach is the Socratic Method. The Socratic Method is an interactive teaching technique wherein instructors use guided questioning to stimulate deeper thought and encourage students to substantiate their opinions. This method supports the development of logical reasoning skills and promotes greater self-reflection among students (Shaheen & Mahmood, 2024). Debate and exercises based on argument also play a crucial role. Debates offer students the opportunity to engage with diverse perspectives and to articulate their viewpoints in a structured manner. In debates, students must ground their arguments in evidence, which cultivates critical thinking and the objective evaluation of information (Tiasadi, 2020). Reflective writing and essay composition are likewise highly effective tools for the development of critical thinking. Through writing, students are required to present their ideas, arguments, and supporting evidence in a structured manner, which fosters analytical thinking and the ability to draw independent conclusions (Sudirman et al., 2024). Another method of considerable significance is project-based learning. In project-based learning, students engage with a specific topic or problem over an extended period, requiring complex analytical and decision-making skills. This method promotes independent research and critical thinking, as students must gather information from multiple sources and synthesize it to draw well-founded conclusions (Quinapallo-Quintana & Baldeón-Zambrano, 2024). Finally, it is important to highlight the increasing importance of digital and interactive tools. With the advancement of modern technology, digital tools such as interactive learning materials, simulations, and online debate platforms are playing an increasingly important role in fostering critical thinking. Online collaborative tools and simulations provide students with opportunities to analyze and critically assess real-world scenarios (Blíznyuk & Kachak, 2024).

In summary, the methods for developing critical thinking employ diverse approaches, yet they share the common goal of enhancing students’ analytical and evaluative abilities. Active learning strategies, problem-solving methodologies, and structured argumentation techniques all contribute to enabling students to critically analyze information and make well-reasoned decisions both within the education environment and beyond (Sharma et al., 2022).

2.2. Relationship Between Critical Thinking and Tertiary Education

One of the primary objectives of tertiary education is to ensure that students emerge not merely as passive recipients of knowledge but as independent, reflective, and critically thinking individuals. The development of critical thinking plays a pivotal role not only during university studies but also in long-term professional success, scientific research, and active participation in societal and political decision-making processes (Katende, 2023). Educational institutions are increasingly adopting teaching methods that foster the development of students’ analytical and problem-solving skills. University courses often create learning environments that encourage students to question traditional perspectives, consider multiple viewpoints, and substantiate their own positions through logical reasoning (Belhad, 2024). A fundamental element in cultivating critical thinking is academic writing and research, which demands data analysis, the weighing of arguments and counterarguments, and the articulation of independent conclusions. Additionally, tertiary education makes extensive use of interactive learning methods, such as debates, case studies, and group projects, all of which contribute significantly to strengthening students’ critical thinking abilities (Sharma et al., 2022). The development of critical thinking varies across different academic disciplines. In the humanities and social sciences, particular emphasis is placed on the analysis of texts, the construction of arguments, and the consideration of historical contexts. In the fields of natural sciences and engineering, critical thinking primarily manifests through experimental methods and data interpretation, while in economics and legal studies, logical reasoning and the modeling of complex problems receive greater emphasis (Wani & Hussian, 2024). Although the development of critical thinking is a central goal of tertiary education, several challenges may hinder its effective implementation. Some educational systems continue to rely heavily on traditional, lecture-based teaching methods, offering limited opportunities for interactive and reflective learning experiences. Moreover, the growing number of students and the constraints of limited instructional time can further complicate the integration of tasks that demand deep critical engagement (Bachtiar, 2024). Another significant issue is the diversity in students’ prior educational backgrounds and levels of critical thinking skills, which can make it difficult to design uniform educational strategies. Therefore, educational institutions at tertiary level must adopt flexible teaching approaches that accommodate the varied needs and previous experiences of their students (Bachtiar, 2024). Overall, it can be concluded that tertiary education plays a vital role in cultivating critical thinking, a skill indispensable for students’ intellectual and professional development. Universities employ a range of strategies to empower students to independently analyze information, evaluate arguments, and approach scientific and societal issues with a critical mindset. Although the effectiveness of critical thinking education depends on numerous factors, contemporary trends in education increasingly emphasize interactive and reflective learning methods, which foster the development of this essential skill (Kerruish, 2024).

2.3. Global Differences Based on HDI

The development of critical thinking in tertiary education largely depends on a country’s socio-economic situation, educational infrastructure, and cultural characteristics. The Human Development Index (HDI) is a comprehensive indicator that considers life expectancy, education level, and economic prosperity, thus providing a clear reflection of a country’s human development. Comparing countries based on the HDI makes it possible to examine the differences in critical thinking education at varying levels of development (Lind, 2024). Countries with a high HDI—such as the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan—generally place a strong emphasis on fostering critical thinking within their educational systems. In these countries, educational institutions widely employ innovative pedagogical methods, such as problem-based learning, open debates, research-based teaching, and project-based learning (Alamoudi & Bafail, 2023). The tertiary education systems of developed countries typically have adequate funding, modern infrastructure, and well-trained instructors, all of which contribute to the development of students’ critical thinking skills. Universities encourage autonomous learning, the preparation of scientific publications and research projects, as well as interdisciplinary approaches, all of which support the development of students’ analytical and problem-solving abilities (Balogun et al., 2024). In countries with a medium HDI—such as Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, Turkey, and Thailand—education systems have undergone significant progress over recent decades but still face numerous challenges. Although increasing attention is being paid to the development of critical thinking in these countries, their educational systems often still rely heavily on traditional, lecture-based methods that provide fewer opportunities for students to engage in independent thinking (Hamsani et al., 2024). In these countries, the quality of education often shows significant inequalities from both regional and socio-economic perspectives. While universities in major urban centers are often competitive on the international stage, institutions in smaller regions frequently struggle to provide the necessary resources for the development of critical thinking. Financial difficulties, increasing student numbers, and an overburdened faculty can also hinder the application of innovative teaching methods (Bennett et al., 2024). Countries with a low HDI—such as Afghanistan or Haiti—face numerous structural challenges in their tertiary education systems that significantly limit the development of critical thinking. Access to education is often restricted, universities are underfunded, and teaching methods frequently fail to meet modern learning expectations (Nurfarkhana & Priadana, 2023). In these countries, tertiary education often focuses more on the transmission of factual knowledge, while the development of critical thinking is pushed into the background. Furthermore, political instability, economic hardships, and cultural factors—such as an authoritarian approach within education—also contribute to students being less exposed to teaching methods that promote reflective and analytical thinking (Bennett et al., 2024). Overall, the development of critical thinking and its role within educational systems show significant variations based on the HDI. Educational systems in high HDI countries widely employ methods that encourage critical thinking, while countries with medium and low HDI values often face various structural and economic barriers. In order to reduce global inequalities, it is crucial for developing countries to introduce educational reforms, modernize teaching methods, and strengthen international collaborations in tertiary education (Lind, 2024).

2.4. Methods and Trends in Bibliometric Analyses

Bibliometric analysis is a method used for the quantitative examination of scientific publications, enabling the measurement of research trends, collaboration networks, and academic impact. In the investigation of the relationship between critical thinking and tertiary education, bibliometric analysis plays a key role by mapping major research directions, scientific collaborations between countries, and changes within the scientific field (Boudraa & Helmi, 2024). Bibliometric analyses employ various methods to examine scientific publications and citation data. Without claiming to be exhaustive, these methods are summarized in Table 1 below (R. Kumar, 2025).

Table 1.

Methods of bibliometric analyses.

When examining the relationship between critical thinking and tertiary education, bibliometric methods make it possible to uncover the following:

- Which countries and institutions are at the forefront of research in the field of development of critical thinking;

- What major topics and trends dominate the scientific literature related to teaching critical thinking;

- How the scientific research on critical thinking changed during recent decades;

- To what extent different scientific fields are related to the research on critical thinking (Hussain et al., 2025).

In recent years, bibliometric analyses have increasingly employed more sophisticated methods that enable deeper and more comprehensive examination of scientific research. The key trends include the following:

- The increasing importance of open-access databases: Databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar are making more scientific publications accessible, facilitating broader bibliometric analyses (Nuar & Sen, 2024).

- The application of Big Data and Artificial Intelligence: With advances in data analysis technologies, increasingly efficient text mining and network analysis methods are becoming available for the study of scientific research (Nageye et al., 2024).

- The use of altmetrics: Beyond traditional citation metrics, alternative indicators (e.g., social media shares, mentions in blogs, and discussions on professional forums) are gaining prominence, taking into account the societal impact of research (Guechairi, 2024).

In summary, bibliometric analyses provide an effective tool for the scientific examination of the relationship between critical thinking and tertiary education. Through the mapping of citation metrics, network analyses, and thematic trends, we can gain deeper insights into research directions and their global variations. Advances in data analysis technologies offer further opportunities for bibliometric studies, contributing to a deeper understanding and organization of scientific knowledge (Boudraa & Helmi, 2024).

3. Materials and Methods

Within the research field of critical thinking and tertiary education, we mapped the structure and themes of the scientific discourse through bibliometric analysis using the VOSviewer software (version 1.6.20). Data mining was conducted on 3 March 2025 by processing relevant publications from the Web of Science database. We analyzed journal article data published between 2020 and 2025 to identify the latest trends in critical thinking research. During data collection, we defined the search criteria shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Search criteria.

The publications that met the search criteria were categorized into four groups based on the HDI index of their country of origin: very high HDI, high HDI, medium HDI, and low HDI. Countries were assigned based on the affiliations of all authors listed in Web of Science, allowing a single publication to appear under multiple HDI categories. This approach enabled a more accurate geographic mapping of international collaborations, which could have been distorted if classification had been based solely on the first author’s affiliation, thereby ignoring the contributions of co-authors. This categorization enabled a deeper investigation of research trends, aiming to identify the main topics and the key directions of academic discourse based on the level of human development.

During the research, three main research questions were formulated:

- Q1: What major clusters can be identified based on co-keyword analysis, and what thematic characteristics do they exhibit in countries with different HDI levels?

- Q2: What differences can be observed in research focusing on the relationship between critical thinking and tertiary education across countries with different HDI levels?

- Q3: How do the educational strategies and methods applied to develop critical thinking differ between highly developed (very high and high HDI) and less developed (medium and low HDI) countries?

In addition to the research questions, the authors also formulated research hypotheses, summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

The list of research hypotheses.

Data processing steps included the following:

- Cleaning of Bibliographic Data: Relevant publications were identified, and irrelevant or duplicate records were removed through manual review and comparison of titles and keywords. A single publication could appear under multiple HDI categories if it involved co-authors from different countries; however, within each HDI group, duplicates were excluded to ensure that each publication was counted only once.

- Analysis of Keywords and Co-Keywords: Using the VOSviewer software, we analyzed the keywords associated with each publication and examined the frequency of keyword occurrences. Keywords that appeared at least five times were included in the co-keyword analysis.

- Cluster Analysis: Based on the frequency of keyword occurrences and their network connections, clusters were identified. These clusters represent the main research directions in the application of critical thinking in tertiary education. Each cluster was analyzed and named according to its constituent keywords.

- Comparison by HDI Categories: The identified clusters were compared across countries with different HDI levels, revealing differences in research focus and priorities according to the level of human development.

4. Results

4.1. Examination of the First Research Question

The first research question formulated before the research process began was as follows: What major clusters can be identified based on keyword analysis, and what thematic characteristics do they exhibit in countries with different HDI indices?

Below, we provide a detailed presentation of how the research focuses on critical thinking and higher education differ in countries with varying levels of the Human Development Index (HDI).

4.1.1. Very High HDI Countries

In highly developed countries, research on critical thinking and tertiary education requires an extremely diverse and interdisciplinary approach that integrates numerous scientific fields. In our analysis, we identified a total of 2380 relevant publications on the subject, covering a wide range of areas, including the influence of pedagogy, psychology, philosophy, education policy, and technology on the development of critical thinking in tertiary education. Based on the literature review and in-depth keyword analysis, we found 7509 distinct keywords that help uncover research focuses and trends. Through the so-called co-keyword analysis, we identified 566 keywords that appeared at least five times, indicating the recurring and prominent topics within the body of research.

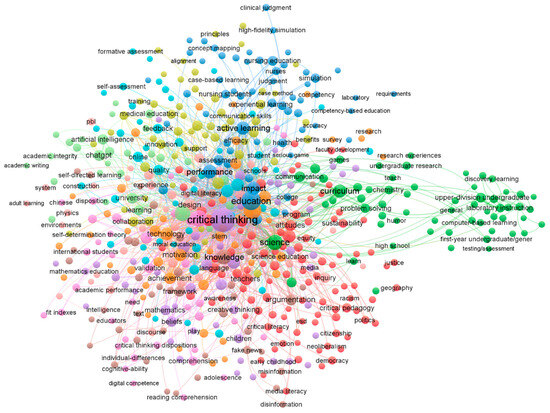

Through cluster analysis of the identified keywords, we were able to define 11 well-distinguished clusters, illustrating the interconnections between different scientific disciplines and research directions. These clusters are also visually represented in Figure 1 using a network-based map layout, offering insights into the relationships among key topics and the structure of research landscapes.

Figure 1.

Co-keyword map of countries with a very high HDI index. Source: based on the authors’ own research, edited by using the VOSviewer program, 2025.

Based on the keywords associated with each cluster, several thematic clusters were identified, which are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Cluster analysis of publications from countries with a very high HDI.

4.1.2. High HDI Countries

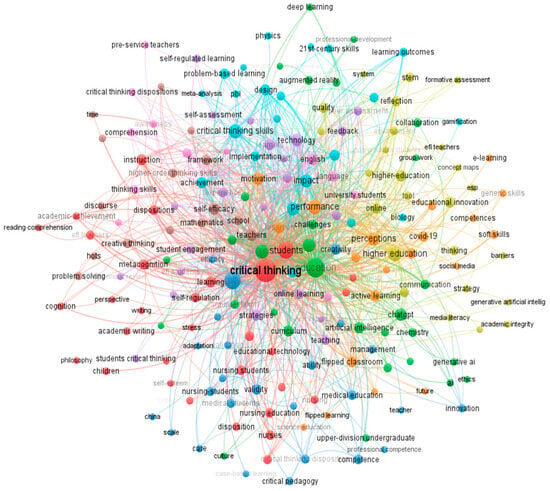

Research on critical thinking and tertiary education in countries with a high Human Development Index (HDI) is likewise highly complex and spans multiple academic disciplines. In our analysis, we identified 1015 relevant publications that explore various aspects of the development and application of critical thinking within education contexts. From these publications, a total of 3639 keywords were extracted, shedding light on the thematic focus of the research. Through co-keyword analysis, 204 keywords were identified as particularly frequent and influential, indicating their central role in the research discourse. Based on cluster analysis of these keywords, nine distinct clusters were identified, illustrating the major research areas and their interconnections. These clusters are visually represented in Figure 2 in the form of a co-keyword map, which provides a visual overview of the networked relationships among the key themes and concepts.

Figure 2.

Co-keyword map of high HDI countries. Source: based on our own research, using the VOSviewer program, 2025.

The nine different clusters were named and categorized based on their thematic content and are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Cluster analysis of publications from countries with a high HDI.

4.1.3. Medium HDI Countries

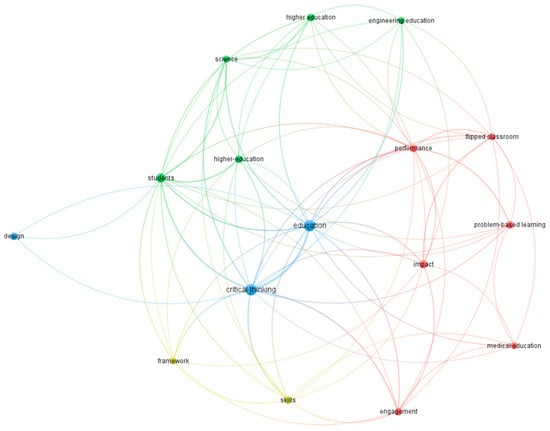

The number of studies originating from medium HDI countries was significantly lower; a total of 113 relevant publications were identified on the topic of critical thinking and tertiary education. These studies typically examine local educational challenges, the barriers to developing critical thinking, and regional specificities. From these publications, 595 keywords were extracted, revealing the main research focus. Among them, only 16 keywords were identified as occurring at least five times, indicating that the discourse surrounding the topic is less concentrated and shows a wider distribution. As a result of frequency analysis and cluster formation, the most important keywords were grouped into four distinct clusters, reflecting the main directions of the research. These clusters are also presented visually in Figure 3 to provide a clearer overview of research trends and interconnections in medium-developed countries.

Figure 3.

Co-keyword map of medium HDI countries. Source: our own research, edited by using the VOSviewer program, 2025.

The name and analysis of the clusters are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Cluster analysis of publications from medium HDI countries.

4.1.4. Low HDI Countries

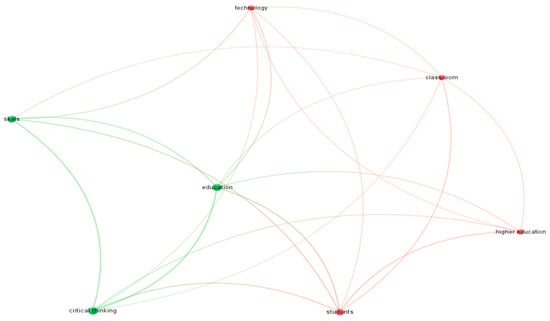

In our analysis, a total of 71 publications were identified from countries with low Human Development Index (HDI). Out of 435 keywords, only 7 met the threshold of appearing at least five times, forming two distinct clusters, which are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Co-keyword map of low HDI countries. Source: our own research, edited by using the VOSviewer program, 2025.

The cluster analysis of co-keywords of low HDI countries is summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Cluster analysis of publications from low HDI countries.

4.2. Examination of the Second Research Question

The second research question formulated by the authors prior to the commencement of the research process was as follows: What differences can be observed in the focus of studies examining the relationship between critical thinking and tertiary education across countries with varying Human Development Index (HDI) levels?

Publications originating from very high HDI countries (11 clusters) tend to examine critical thinking within a broader, more holistic context. These studies emphasize the social responsibility of education, interdisciplinary approaches, digital education, and the impacts of artificial intelligence. In contrast, clusters from high HDI countries (nine clusters) more frequently focus on specific pedagogical methods (e.g., cooperative learning, problem-based learning), individual learner characteristics (e.g., self-regulation, self-assessment), and the direct outcomes of educational processes (e.g., learning results, skills development). In the clusters from medium HDI countries, research primarily concentrates on pedagogical approaches and educational outcomes; the prevalence of themes such as the flipped classroom, problem-based learning, and learner engagement indicates that researchers in these contexts are particularly focused on enhancing the effectiveness of education. In the clusters from low HDI countries, the emphasis shifts toward the fundamental infrastructure and general development of education. In this case, the central focus lies on educational technologies and the development of higher education systems.

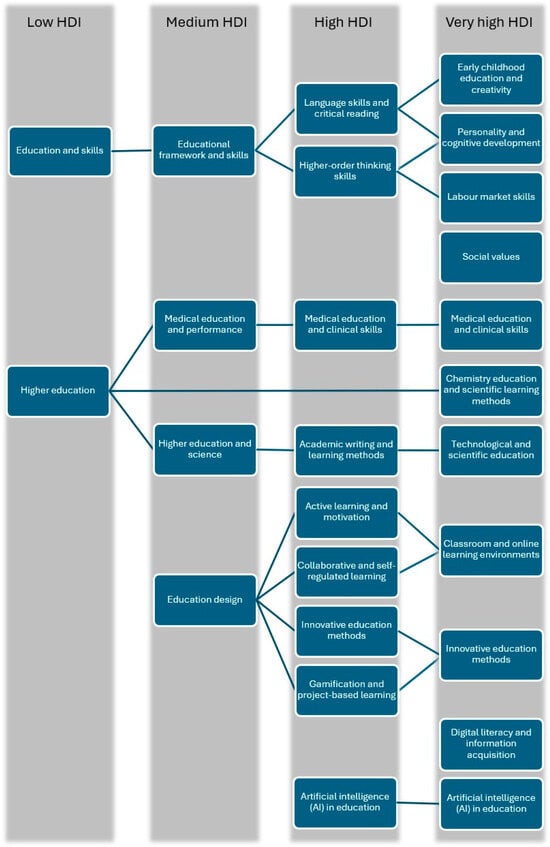

The clusters identified through the co-keyword analysis, along with their interrelations, are illustrated in Figure 5, visually representing the main differences between country groups.

Figure 5.

Clusters on critical thinking across countries with different HDI classification. Source: our own research and our own editing, 2025.

In very high HDI countries, research on critical thinking tends to be more interdisciplinary, often integrating natural sciences, social sciences, and digital technologies (e.g., STEM, environmental protection, sustainability education). In contrast, studies from high HDI countries typically focus on specific academic disciplines (e.g., medical and nursing education, language education) and show fewer interdisciplinary overlaps. Research from medium HDI countries particularly emphasizes medical and engineering education, while publications from low HDI countries are less focused on specific disciplines and concentrate more on the general development of tertiary education.

4.2.1. Examination of the Validity of Hypothesis 1

In addition to answering the research questions, it is also essential to assess the validity of the hypotheses formulated at the outset of the study. Hypothesis 1 states:

H1.

Significant differences can be observed in the focus of research on the relationship between critical thinking and tertiary education across countries with varying HDI levels, with research in lower HDI countries (medium and low HDI) demonstrating a narrower focus on critical thinking.

In very high HDI countries, research applies an interdisciplinary approach and places particular emphasis on global challenges such as sustainable development, social justice, and digital literacy. Innovations—especially the application of artificial intelligence (AI)—play a central role in education, alongside the development of STEM fields and 21st-century labor market skills. In contrast, research in high HDI countries focuses on active learning environments, collaborative learning, and innovative educational methods, such as gamification and project-based learning. AI also plays a key role in this case, along with a strong emphasis on academic writing and the development of language skills. Studies from medium HDI countries are more practice-oriented, concentrating primarily on methods in medical education (e.g., problem-based learning) and educational planning. The development of educational frameworks and improving student performance are central themes. In low HDI countries, research primarily targets the structural aspects of education—such as classroom environments and the development of fundamental skills. Innovations are less emphasized, with a stronger focus placed on establishing the foundations of critical thinking. The key differences identified through cluster analysis and the most frequently occurring keywords (presented in Appendix A) are summarized in Table 8 below.

Table 8.

Comparison on publications on critical thinking and tertiary education from countries with varying HDI levels.

Based on the co-keyword analysis and cluster examination of publications from countries with different HDI levels, it is evident that the level of socio-economic development significantly influences how critical thinking and its development in tertiary education are approached. In very high HDI countries, research examines critical thinking within a global social, technological, and ethical context. In contrast, high HDI countries tend to focus more on pedagogical strategies and specific skills. Medium HDI country studies emphasize educational effectiveness, educational planning, and frameworks, while low HDI countries prioritize the development of educational infrastructure and development of basic skills. While research in higher HDI countries tends to address more complex themes, in lower HDI countries, the focus remains on fundamental educational challenges. Therefore, we accept our H1 hypothesis, according to which there are significant differences in the research focus on the relationship between critical thinking and higher education across countries with varying HDI levels, with medium and low HDI countries displaying a narrower focus in critical thinking research.

4.2.2. Examination of the Validity of Hypothesis 2

Following the confirmation of the first hypothesis, we now examine the second hypothesis, which states:

H2.

The role of artificial intelligence (AI) and technology is more prominently represented in more developed (very high and high HDI) countries.

Our hypothesis analysis was conducted based on the most frequent keywords listed in Appendix A and the cluster analysis related to Research Question 1. According to our results, studies from very high and high HDI countries address the impacts of AI and generative artificial intelligence on education in detail. Topics such as digital literacy, learning analytics, gamification, e-learning, and virtual reality suggest that these countries are actively researching the role of technology in developing critical thinking. In high HDI countries, technological tools appear primarily as pedagogical instruments (e.g., STEM education, online learning, gamification), whereas in very high HDI countries, they are considered part of the structural transformation of education. In medium HDI countries, AI does not appear at all, and technology is only marginally represented through keywords such as “flipped classroom” and “engineering education.” In low HDI countries, the role of AI is not addressed either; although the keyword “technology” does appear, it is not treated as a methodological tool but rather as a general factor necessary for the modernization of education. Based on these findings, we accept our H2 hypothesis, which states that the role of artificial intelligence (AI) and technology is more prominent in more developed (very high and high HDI) countries.

4.3. Examination of the Third Research Question

Our third research question was formulated as follows: How does the focus of educational strategies and methods aimed at developing critical thinking differ between more developed (very high and high HDI) and less developed (medium and low HDI) countries?

In very high HDI countries, there is often a strong emphasis on reflective thinking, metacognitive strategies, and pedagogies that promote intercultural awareness and social justice. These countries tend to treat critical thinking within a broader context, as part of democratic education and societal progress. In high HDI countries, the focus is more on developing individual learner skills, such as self-regulation, self-assessment, learning strategies, and cognitive development. Among educational methods, innovative pedagogies—including problem-based learning (PBL), simulations, and collaborative learning—are especially significant. In medium HDI clusters, the key themes include problem-based learning (PBL), flipped classrooms, and performance assessment. In low HDI countries, the topics of critical thinking, skills development, and higher education appear, but in a less specific and less structured manner. In general, research in less developed (medium and low HDI) countries tends to focus on the overall improvement of education quality and the development of student skills.

Examining the Validity of Hypothesis 3

Finally, the third hypothesis formulated by the authors was as follows:

H3.

In more developed countries (very high and high HDI), research related to critical thinking and tertiary education places greater emphasis on innovative pedagogical methods.

The focus of educational strategies and methods applied to develop critical thinking differs significantly between more and less developed countries. In more developed countries (very high and high HDI), the emphasis is on innovative pedagogical methods, such as gamification, project-based learning, flipped classroom, as well as the integration of digital tools and artificial intelligence (AI) into education. In addition, there is a strong focus on transmitting social values and developing 21st-century workforce skills. In moderately developed countries (medium HDI), educational strategies mainly focus on medical education and scientific training, employing methods such as problem-based learning (PBL) and flipped classrooms, while educational planning and skills development are also key areas. In less developed countries (low HDI), the focus is on the general development of higher education and the development of basic skills. The focus of educational strategies and methods related to critical thinking is summarized in Table 9 according to the HDI classification of countries.

Table 9.

Pedagogical approaches in publications on critical thinking and tertiary education by HDI classification.

The results of the analysis confirm the hypothesis that, in more developed countries (very high and high HDI), research related to critical thinking and higher education places a greater emphasis on innovative pedagogical methods. Research from very high HDI countries focuses particularly on technological innovations, the integration of AI into education, digital literacy, and interdisciplinary approaches. In contrast, studies from high HDI countries examine the effectiveness of gamification, project-based learning, and active learning environments. These studies aim to develop higher-order thinking skills and increase student motivation, which supports the prominent role of innovative pedagogical methods in these countries. Based on our findings, we accept Hypothesis 3, which states that, in more developed (very high and high HDI) countries, research on critical thinking and tertiary education places a greater emphasis on innovative pedagogical methods.

5. Discussion

Based on the results of the research, it can be clearly established that the role of critical thinking in tertiary education—and the related body of research—varies significantly across countries with different levels of human development. The clusters identified during the analysis and the frequency of keywords revealed clear trends: in more developed countries, critical thinking appears in a broader, interdisciplinary, and innovative pedagogical context, whereas in less developed countries, the focus is more on the fundamental improvement of education and addressing structural deficiencies.

In countries with a very high HDI, research on critical thinking centers around innovation, technological advancement, and social and ethical issues. An interdisciplinary approach is typical, incorporating natural sciences, digital literacy, educational technologies, and social responsibility. These countries place a strong emphasis on pedagogical methods that foster the development of students’ independent thinking.

Research from these countries highlights that the development of critical thinking is closely linked to problem-solving skills, creative thinking, and multidisciplinary educational programs. Tertiary education in these nations increasingly emphasizes the creation of adaptive learning environments that enable students to acquire dynamic thinking strategies (Sharma et al., 2022; Katende, 2023; Wani & Hussian, 2024; Quinapallo-Quintana & Baldeón-Zambrano, 2024).

In high HDI countries, research also significantly focuses on innovative teaching methods, but it is less interdisciplinary and tends to concentrate more on specific academic disciplines. Educational strategies aimed at developing critical thinking primarily emphasize cooperative learning, self-regulated learning techniques, and individual cognitive development. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and other digital tools into education is also prominent, though these often appear more as pedagogical tools rather than as key elements in the structural transformation of education.

Studies highlight that, in these countries, developing the digital competencies of both teachers and students is essential for fostering critical thinking. AI-based adaptive learning platforms are becoming increasingly widespread, as they enable the creation of personalized learning pathways (Chira, 2020; Sajja et al., 2023).

In medium HDI countries, research on critical thinking is more targeted and practically oriented. The main focus is on improving educational quality, strengthening educational structures, and addressing specific subject areas (such as medical and engineering education). Among educational strategies, the flipped classroom, problem-based learning (PBL), and enhancing student engagement receive more emphasis, although innovation appears less broadly.

Research indicates that one of the major barriers to teaching critical thinking in these countries is outdated curricular structures and teachers’ limited methodological training. As a result, reforms primarily concentrate on teacher training and the introduction of modern pedagogical tools (Leibovitch et al., 2024; Anis, 2024).

In low HDI countries, research primarily focuses on fundamental educational issues and infrastructural challenges. Strategies aimed at developing critical thinking are less specific, with a stronger emphasis on general skill development and the overall improvement of tertiary education.

Initiatives to improve the education system often depend on donors and international organizations, which affects the possibilities for fostering critical thinking. In low HDI countries, the reform of teacher training and ensuring access to basic educational resources are top priorities (Steiner-Khamsi, 2025).

The research findings support hypothesis H1 that states that, in countries with lower HDI indices, the focus of critical thinking research is narrower. In very high and high HDI countries, interdisciplinary and innovative approaches dominate, while in medium and low HDI countries, emphasis is placed on structural and fundamental educational development.

The role of artificial intelligence and technology is significantly more pronounced in more developed HDI countries, thereby confirming hypothesis H2 as well. In very high HDI countries, AI appears as part of the transformation of education, whereas in high HDI countries, it is more often applied as a pedagogical tool. In medium and low HDI countries, the role of AI and digital tools is far less prominent.

Hypothesis H3—that countries with higher HDI levels place greater emphasis on innovative pedagogical methods—was also confirmed. In more developed countries, there is a strong focus on gamification, project-based learning, and the integration of digital literacy, whereas in less developed countries, teaching methods are less advanced and pedagogical innovations appear only partially.

Based on the results, the HDI level strongly influences the priorities and methods of educational research. The educational strategies for developing critical thinking and related factors are closely linked to a country’s level of development. In more developed countries, the methods and technologies used to foster critical thinking are far more sophisticated, while in developing countries, the primary goal remains improving the quality of basic education and addressing infrastructural shortcomings. Research in developed countries covers a broader spectrum with a greater focus on technology and innovation, whereas in less developed countries, the main challenge is the enhancement of basic skills and the strengthening of educational structures.

Overall, our research findings confirm that the HDI level significantly determines the priorities of educational research. The strategies and tools for teaching critical thinking vary considerably across development levels, which affects the application of pedagogical innovations and the opportunities for students to develop higher-order thinking skills.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Although bibliometric analysis is an effective method for identifying scientific trends, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. Our research was based solely on the Web of Science database, and studies available in other databases (e.g., Scopus, ERIC) were excluded from the analysis, which may lead to a distorted representation of regional research. This study treated all included publications as qualitatively equivalent, without differentiating between journal quality (e.g., quartile ranking) or research type (empirical vs. theoretical). Considering such distinctions in future work could enrich the analysis and allow for more nuanced interpretations. Additionally, the HDI index-based categorization does not account for the specificities of individual countries’ educational systems and cultural differences. Moreover, while the Human Development Index is a relevant composite indicator, it does not reflect cultural, religious, or political factors that may significantly shape educational practices and the development of critical thinking. Acknowledging these contextual limitations would provide greater depth to cross-national comparisons. Furthermore, the keyword-based analysis may not fully capture the entire academic discourse, as variations in keyword usage among authors could influence the results. For future research, it would be beneficial to incorporate a wider range of databases, complement the findings with qualitative analyses, and explore the role of educational policies and cultural factors in the development of critical thinking.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.H. and L.F.; methodology, K.H.; software, K.H.; validation R.M., E.K. and L.F.; formal analysis, K.H.; investigation, K.H., L.F.; writing—original draft, K.H., L.F.; writing—review & editing, K.H., R.M., E.K., L.F.; visualization K.H.; supervision, R.M., E.K.; project administration, R.M., E.K. and L.F.; funding acquisition R.M. and E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research has been supported by Project—KEGA003UJS-4/2024: “The application of innovative educational methods in the context of the development of critical thinking in higher education”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository. The original data presented in the study are openly available in the Web of Science (WoS) article database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The most frequently used 20 keywords in different HDI countries.

Table A1.

The most frequently used 20 keywords in different HDI countries.

| Very High HDI | High HDI | Medium HDI | Low HDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | education (387) | education (203) | education (27) | education (15) |

| 2 | students (263) | students (137) | students (13) | students (12) |

| 3 | higher education (227) | skills (122) | higher education (13) | skills (11) |

| 4 | skills (218) | higher education (98) | impact (8) | higher education (6) |

| 5 | science (166) | science (62) | skills (8) | technology (6) |

| 6 | knowledge (133) | performance (58) | performance (7) | classroom (5) |

| 7 | performance (108) | critical thinking skills (57) | engagement (6) | science (4) |

| 8 | curriculum (96) | knowledge (49) | problem-based learning (6) | thinking (4) |

| 9 | impact (94) | impact (45) | design (6) | achievement (4) |

| 10 | active learning (87) | model (45) | science (5) | critical thinking skills (4) |

| 11 | perceptions (77) | perceptions (39) | flipped classroom (5) | self-efficacy (4) |

| 12 | creativity (74) | motivation (37) | framework (5) | Nigeria (4) |

| 13 | technology (71) | teachers (37) | engineering education (5) | instruction (3) |

| 14 | pedagogy (71) | technology (34) | medical education (5) | user acceptance (3) |

| 15 | teachers (67) | chatgpt (33) | learners (4) | engineering education (3) |

| 16 | model (65) | English (32) | pedagogy (4) | gender (3) |

| 17 | engagement (63) | self-efficacy (31) | online (4) | Tanzania (3) |

| 18 | motivation (61) | classroom (26) | technology (4) | attitudes (3) |

| 19 | critical thinking skills (59) | creativity (25) | augmented reality (4) | performance (3) |

| 20 | achievement (56) | artificial intelligence (25) | teachers (4) | model (3) |

Source: Our own research and our own editing, 2025.

References

- Abidin, Z., & Sulaiman, F. (2024). The effectiveness of problem based learning on students’ ability to think critically. Zabags International Journal of Education, 2(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoudi, M., & Bafail, O. (2023). Human development index: Determining and ranking the significant factors. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology, 12(3), 231–245. [Google Scholar]

- Angwaomaodoko, E. A. (2024). Critical thinking: Strategies for fostering a culture of inquiry in education. Path of Science, 10(9), 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis, M. (2024). Teacher professional development in the digital age: Adressing the evolving needs post-Covid. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, 6(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bachtiar. (2024). Strategies and challenges in encouraging students’ critical thinking skills in online learning: A literature review. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, 6(2), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Balogun, S. O., Olaleye, A. S., Gbadegeshin, A. S., Agbo, F., & Mogaji, E. (2024). Higher education management in developing countries: A bibliometric review. Information Discovery and Delivery, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Belhad, B. (2024). Critical thinking in education: Skills and strategies. International Journal of Social Science and Human Research, 7(7), 4723–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, P., Foley, K., Green, A. D., & Salvanes, G. K. (2024). Education and inequality: An international perspective. Fiscal Studies, 45(3), 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blíznyuk, T., & Kachak, T. (2024). Benefits of interactive learning for students’ critical thinking skills improvement. Journal of Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University, 11(1), 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudraa, C., & Helmi, D. (2024). Bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review in management practices & artificial intelligence. Revue Internationale des Sciences de Gestion, 7(4), 26–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chira, C. (2020). A digitális kompetencia keretrendszerei és a pedagógusok digitális kompetenciája. In A kultúraváltás hatása az egyéni kompetenciákra (pp. 38–57). Eszterházy Károly Egyetem Líceum Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Guechairi, S. (2024). Mapping altmetrics: A bibliometric analysis using Scopus (2012–2024). Science and Knowledge Horizons Journal, 4(1), 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamsani, H., Samsuddin, A. M., Affando, A., & Affresia, R. (2024). Analysis of increasing Human Development Index (HDI) based forecasting approaches. Equity Jurnal Ekonomi, 11(2), 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, W. H. N. W., Fadzil, M. H., & Shahali, M. H. E. (2025). Critical thinking in science education: A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Education, Psychology and Counselling, 10(57), 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katende, E. (2023). Critical thinking and higher education: A historical, theoretical and conceptual perspective. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(8), 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerruish, E. (2024). Postdigital teaching of critical thinking in higher education: Non-instrumentalised sociality and interactivity. Postdigital Science and Education, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J. M. (2024). The imperative of critical thinking in higher education. IETE Technical Review, 41(5), 509–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. (2025). Bibliometric analysis: Comprehensive Insights into tools, techniques, applications, and solutions for research excellence. Spectrum of Engineering and Management Sciences, 3(1), 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibovitch, M. Y., Beencke, A., Ellerton, J. P., McBrien, C., Robinson-Taylor, L. C., & Brown, D. (2024). Teachers’ (evolving) beliefs about critical thinking education during professional learning: A multi-case study. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 56(4), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, N. (2024). Human Development Index (HDI). In Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 3285–3286). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Nageye, Y. A., Jimale, A., Abdullahi, O. M., & Ahmed, A. Y. (2024). Emerging trends in data science and big data analytics: A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Electronics and Communication Engineering, 11(5), 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuar, A. N. A., & Sen, C. S. (2024). Examining the trend of research on big data architecture: Bibliometric analysis using Scopus database. Procedia Computer Science, 234, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurfarkhana, A., & Priadana, S. (2023). Human development index as an effort to increase economic growth. Return Study of Management Economic and Business, 2(1), 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuryana, I., Sugeng, B., Soesilowati, E., & Andayani, E. S. (2024). Critical thinking in higher education: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 16(5), 2216–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passas, I. (2024). Bibliometric analysis: The main steps. Encyclopedia, 4(2), 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinapallo-Quintana, M. A., & Baldeón-Zambrano, B. X. A. (2024). Project-based learning. International Research Journal of Management IT and Social Sciences, 11(1), 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusmin, L., Misrahayu, Y., Pongpalilu, F., Radiansyah, & Dwiyanto. (2024). Critical thinking and problem solving skills in the 21st century. Journal of Social Science, 1(5), 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajja, R., Sermet, Y., Cwiertny, D., & Demir, I. (2023). Integrated AI and learning analytics for data-driven pedagogical decisions and personalized interventions in education. arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, L., & Mahmood, N. (2024). Correlation between socratic questioning and development of critical thinking skills in secondary level science students. International Journal of Innovation in Teaching and Learning, 10(2), 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M., Doshi, M. B., Verma, M., & Verma, A. (2022). Strategies for developing critical-thinking capabilities. World Journal of English Language, 12(3), 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2025). Time in education policy transfer: The seven temporabilities of global school reform (p. 242). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 78-3-031-82524-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sudirman, A., Gemilang, V. A., Kristanto, A. M. T., Robiasih, H., Hikmah, I., Nugroho, D. A., Karjono, S. C. J., Lestari, T., Widyarini, L. T., Prastanti, D. A., Susanto, R. M., & Rais, B. (2024). Reinforcing reflective practice through reflective writing in higher education: A systematic review. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 23(5), 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiasadi, K. (2020). Debating practice to support critical thinking skills: Debaters’ perception. AKSARA Jurnal Bahasa dan Sastra, 21(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, A. S., & Hussian, Z. (2024). Developing critical thinking skills: Encouraging analytical and creative thinking. In Transforming education for personalized learning (pp. 114–130). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Yücel, G. A. (2025). Critical thinking and education: A bibliometric mapping of the research literature (2005–2024). Participatory Educational Research, 12(2), 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).