Abstract

The relationship between humans and protected areas may contribute to the success of conservation efforts. The Qinling Mountains are significant to China and the rest of the world, and the Qinling Zhongnanshan UNESCO Global Geopark comprises eight distinct scenic spots with residential communities. This study investigated the Geopark’s relationship between humans and protected areas by examining local residents’ incomes and land ownership characteristics. Data were derived from a questionnaire survey of 164 residents living in or near four of the eight scenic spots. Their individual and household incomes, requisitioned farmland losses and compensations, employment, and participation were analyzed. Most respondents were aged 30–70 years, and 90.9% were locally born and raised in the region. They tended to be self-employed in food catering or accommodation services within the Geopark or near its entrance. Reliance on the Geopark for their livelihoods was significant, because they worked full-time and earned a major share of their household incomes from Geopark-related employment. Fifty respondents reported that their farmland was requisitioned during the Geopark’s establishment. However, not all of them were financially compensated, and compensation was not equally distributed among those who received it. Reforming the complex top-down administrative system and developing an effective profit-sharing scheme for local residents are suggested measures for enhancing public satisfaction and knowledge about the Geopark, both factors that were low among the respondents. Increasing the local residents’ participation in Geopark activities is an important way to avoid conflict; increasing the number of job opportunities for local residents is proposed to achieve this goal.

1. Introduction

Protected areas (PAs), a cornerstone of biodiversity conservation, are effective ways to mitigate the losses of biodiversity and habitat [1,2] and have long been considered significant tools for maintaining habitat integrity, species’ diversity, and representative samples of the biotopes [2,3,4,5]. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines these areas as geographical spaces with clear demarcations determined by legal or other effective means, which are recognized, dedicated, and managed to achieve long-term nature conservation with related ecosystem services and cultural values [6]. PAs currently cover more than 15% of the world’s land surface [7]. Some concerns have arisen that PAs should contribute to sustaining their local communities’ livelihoods [8,9,10]. However, commercial interests, such as mines, dams, roads, and tourism, might put pressure on those PAs [11].

China’s total PA area currently comprises 21.02% of its territory (land area: 15.61%; marine area: 5.41%) [12]. Many scholars have researched China’s PAs, such as Xu [13], who pointed out that PAs have various objectives and criteria for success depending on their goals [4]. For example, PAs variously focus on conserving ecosystems and species, protecting threatened species, ecosystem services, and cultural or social factors [3,14,15,16]. The effective management of PAs may lead to success [10]. Karanth [17] reported that conservation success is strongly dependent on the relationships between residents and management. Furthermore, positive relationships between PAs and their local communities may improve conservation outcomes [18], as Holmes [19] indicated, that local people can refuse cooperation with management officials if they do not support the PAs. Moreover, Tessema [20] concluded that PA–community relationships are of great significance to the conservation of wild life. Consequently, the human–PA relationship is very important [21] and is a significant predictor of a PA’s success [22]. Redpath [23] indicated that this relationship is a highly debated issue because local support does not exert a strong influence on the conservation of wildlife in PAs. Other scholars agree [24,25]; however, the wellbeing of a PA’s local community should be considered because it is important to the success of wildlife conservation [24]. As was also stated by Jonathan, appropriate management, including allowing more local participants into management occupations and granting access to resources, would increase local satisfaction. This should lead to a more harmonious relationship between the PAs and their local communities.

Zhongnanshan Mountain, famous throughout China and around the world for its geological and geographical significance, is located in the midsection of the Qinling Mountains. Some scholars have focused their research on this region. For example, Yang et al. [26] conducted research on the regional geological setting, evolution, and strata of the Qinling Zhongnanshan UNESCO Global Geopark (QZUGG), and concluded that the area has distinctive, perhaps unique, features compared to the geosites in other global geoparks. Tie [27] discussed protections and ways to develop the area’s tourism. However, no studies have described or analyzed the relationship between the management of the Geopark and its local residents. During the field work and preliminary interviews with some local residents, it appeared that the PA–community relationship was tense. Local people seemed dissatisfied with the Geopark’s management. Therefore, this study investigated the local community in and around the Geopark, in terms of residents’ employment, occupations, financial situations, and the extent to which the local residents were satisfied with the QZUGG.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

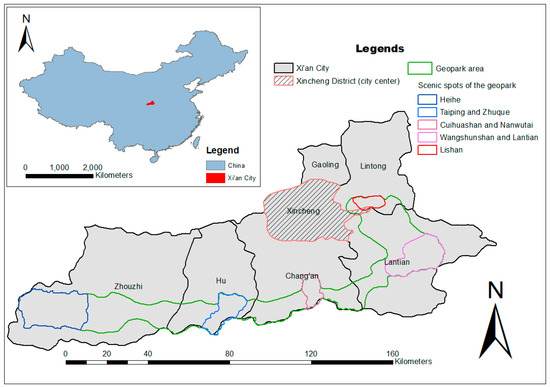

The Qinling Mountains are a major east-west mountain range that provides China with a transcontinental natural boundary between its northern and southern regions, including distinguishing their geology, geography, ecology, climate, and humanities [26]. This study’s sites (Figure 1) were four scenic spots of the QZUGG in the main part of the Qinling orogenic belt [26]. Preliminary fieldwork and an interview with a management official suggested the importance of the Zhuque, Taiping, Cuihuashan, and Wangshunshan scenic spots as research targets. These four locations are the most useful because of their relatively long histories, high prestige, and large numbers of tourists. Located in southern Xi’an, QZUGG, which is usually regarded as the “Chinese Central National Park,” covers an area of about 1074.85 km2. Of all the world’s geoparks, QZUGG is the closest to a large city because it is a mere 25 km from Xi’an [26]. QZUGG boasts eight scenic spots (Figure 1). However, these eight spots are designated as National Forest Park or National Geopark, and, therefore, they are independently managed by different government agencies (Table 1). In 2009, QZUGG was designated a member of the Global Geopark Network (GGN) and named Qinling Zhongnanshan UNESCO Global Geopark after validation [28].

Figure 1.

Qinling Zhongnanshan UNESCO Global Geopark (QZUGG) and its proximity to Xi’an City.

Table 1.

QZUGG’s eight scenic spots by name, area, and proximity to Xi’an City’s center.

2.2. Analytical Methods

This study is part of a larger study of the same area that examined and evaluated QZUGG’s management as well as its users’ perceptions and satisfaction. This study employed a mixed method of interviews and questionnaire surveys, including a face-to-face household questionnaire survey, to obtain data. The questionnaire contains two types of questions. The first type contained several questions related to their demographics, occupations, livelihood, and incomes. The other type of questions employed a five-point Likert scale to evaluate respondents’ satisfaction. In-depth interviews were conducted in 2017 with four management officials (one at each of the four scenic spots, namely, the Zhuque, Taiping, Cuihuashan, and Wangshunshan) as well as a professional hiking expert. In addition, in 2017, a questionnaire survey was conducted on a sample of local residents from 50% of the households at each scenic spot (n = 164). Within the area where we were allowed to conduct our research, we visited each household and conducted our questionnaire survey face to face with one representative. The survey targeted the occupational and financial situations of the local residents. To enhance the quality of the questionnaire data, several workshops were held with other professionals before the questionnaire was administered. Furthermore, its reliability and validity were tested using the SPSS version 24 statistical package (by checking the coefficient of Cronbach’s alpha and Pearson correlation), which found acceptable results of 0.926 and 0.728, respectively. The data were faithfully imported into SPSS version 24 for the statistical analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Survey Sample Characteristics

The gender of the respondents of the household survey was almost evenly divided, with 47.6% males and 52.4% females (Table A1). Regarding age, the respondents were mostly aged 30 through 70 (the oldest respondent was 70 years old); respondents younger than age 30 years were just 25% of the sample (Table A1). Most of the respondents (89%) completed middle school or had less education (Table A1). Most of the respondents originated in the local areas (90.9%).

3.2. Employment and Occupation

More than one-half of the respondents at each of the four scenic spots reported holding full-time jobs related to the Geopark (Zhuque (73.2%), Taiping (68.4%), Cuihuashan (62.8%), and Wangshunshan (95.2%)) (Table A2). About 2.6% of the Taiping respondents and about 2.4% of the Zhuque respondents stated that they were civil servants, and about 7% of the Cuihuashan respondents reported employment as business staff. The highest percentage was self-employed (Zhuque: 12.2%, Taiping: 15.8%, Cuihuashan: 9.3%, and Wangshunshan: 4.8%) (Table A2). Some respondents were teachers, students, peasants, or others. The average household size was four, of which 1.25 (on average) were employed at jobs related to the Geopark. On average, 36.1% of the respondents had family members whose jobs were based on the scenic spots, including such roles as catering services, which were the most common (Zhuque: 97.6%, Taiping: 97.4%, Cuihuashan: 90.7%, and Wangshunshan: 83.3%) (Table A2). The second most common job was accommodation services (Zhuque: 63.4%, Taiping: 42.1%, Cuihuashan: 32.6%, and Wangshunshan: 11.9%).

3.3. Income and Livelihood Characteristics

The respondents at the four study sites reported that income from employment related to the scenic spots comprised more than 60% of their household’s total income: 74% in Zhuque, 62% in Taiping, 70% in Cuihuashan, and 77% in Wangshunshan. Most of the respondents reported that they had always lived in their communities: 75.6% in Zhuque, 73.7% in Taiping, 79.1% in Cuihuashan, and 88.1% in Wangshunshan. Approximately one-half of the respondents had lived there for more than 20 years: 83.3% in Zhuque, 47.4% in Taiping, 51.1% in Cuihuashan, and 70.7% in Wangshunshan scenic spots. In Cuihuashan, about 65.1% of the respondents knew that their residences were in the Geopark; about 71.1%, 63.4%, and 69% in Taiping, Zhuque, and Wangshunshan, respectively, were aware of their residential location. They reported various ways by which they had obtained this information; however, the least common was via the GGN official website. They mostly knew they were living in a geopark from their village committees or other governmental organizations (24.2% on average; see Table A3).

3.4. Farmland Requisition for QZUGG

In Cuihuashan, about 60.5% of the respondents reported that their farmlands had been requisitioned for the Geopark (Table A4). The next highest requisition rate was in Taiping (39.5%), followed by Wangshunshan (16.7%). Just 2% of the respondents at Zhuque reported that their farmland had been requisitioned. All of the Wangshunshan respondents whose farmland had been requisitioned had also received some financial compensation; however, none of the Zhuque respondents had been compensated. Some of the respondents from Taiping (26.3%) and a few Cuihuashan respondents (4.7%) reported that they had received financial compensation. The extent of satisfaction with the compensation received varied (Table A4). All of the Cuihuashan respondents reported that they were satisfied, but none from Wangshunshan were satisfied. In fact, in Taiping and Wangshunshan, more than one-half of the respondents were very dissatisfied (Taiping: 60.0%, Wangshunshan: 57.1%).

A bonus from the Geopark was reported only by Taiping respondents, and also only by just 10.5% of them: none of them were satisfied with it (7.9% dissatisfied, 2.6% neutral). Interestingly, 30.2% of the Cuihuashan respondents reported that they received other types of compensation, which included 100 kg of wheat flour per household member per year. One household reportedly received three rooms as compensation; one Taiping respondent stated that he receives about USD 3000 to USD 4500 each year, and one Zhuque respondent did not disclose the nature of his compensation.

4. Discussion

Our research shows that there were few respondents younger than 30 years (Table A1). Some respondents explained that young adults could earn relatively more money for their families as migrant workers. These rural migrant workers (people working outside of where there were born) tend to be young adults who work at home only during planting and harvest seasons [29]. These statements support Chinese government data on the increase in migrant workers in Shaanxi Province [30]. Teye et al. [31] suggested that people with high educational attainment have more positive attitudes, than less educated people regarding tourism development. Education increases awareness and understanding of environmental and political issues [32]. Educated people tend to be better informed on matters, than their less educated counterparts [33]. However, about 70% of the sample had no more than a middle school education (Table A1). Low educational attainment might relate to low satisfaction and negative perspectives, as a result of a lack of understanding the benefits and other positive aspects of geoparks. These respondents may also have had an insufficient understanding of the Geopark itself.

It is interesting that, although more than 90% of the respondents were born in their communities (Table A1), and although several reported more than 20 years of residence there (Table A3), many of them were unaware that they lived in a geopark. This might be related to their low educational attainment or to the GGN’s failure to disseminate and communicate information to the public. In a study conducted in India and Nepal, it was indicated that most local residents knew that they were living in PAs [17]. The main way through which respondents became aware that they lived in a geopark was learning about it from a village committee or other government agency. Before the establishment of the Geopark, each of the scenic spots was either a National Geopark or a National Forest Park. However, it seemed that information regarding this Geopark was not publicized among local residents. It appears that government agencies have an important role in the development and conservation of such areas [34]. Consequently, we suggest that disseminating educational information to PAs’ local communities should be enhanced to raise collective awareness and understanding of the Geopark.

It can be inferred from the data that the respondents were highly dependent on the Geopark for their livelihoods. A large share of the respondents worked full-time jobs related to the Geopark (Table A3), suggesting that they no longer farmed or had other occupations. Furthermore, almost 40% of the respondents relied on the Geopark for their entire family’s income (Table A5). Almost one-half of the household members (on average) had jobs related to the Geopark, indicating the Geopark’s positive function for providing job opportunities and support to its local residents. However, these were mostly food catering and accommodation service jobs in or near the entrance to the Geopark. Few jobs were posted for which local people qualified, and, during the interviews, only two local people reported being directly hired by the Geopark. It is clear that the Geopark does not offer sufficient job opportunities for the local people, which could alienate the local residents from the Geopark and impede their understanding and perception of the Geopark.

It is reasonable for employment contractors to seek the people with the best work experience and education to fill a particular job opening; however, they should consider hiring local residents as it would lead to more efficient management of the PA, particularly regarding conflict with the local people [35]. Bookbinder [36] argued that employment of the local people can make them view the PAs in a positive way and discourage them from collecting firewood or poaching wildlife, which will in turn make the management of the PA easier and more effective. Furthermore, when more land is needed to expand the geopark or when new rules are implemented for management purposes, it would be helpful to have local people on the payroll because the extent of the local people’s understanding and awareness of geopark activities depends on their level of engagement with the geopark [37]. Karanth [17] also pointed out that constructive engagement with local residents would support long-term success of conservation. A profit-sharing or bonus scheme might help to secure local people’s financial interests [38] and increase their satisfaction with the Geopark, which is crucial to QZUGG’s success. Previous studies have emphasized the need to increase job opportunities for local residents [39,40], which would significantly strengthen the human–geopark relationship.

Directly benefitting the local people might be key to avoiding conflicts between them and the PAs, as the benefits to the locals can be substantial, such as tourism-generated income [41]. Understanding the local people’s benefits related to the Geopark is essential for striking a balance between conservation goals and local communities’ needs [11,42]. However, only a small number of local households received compensation, and not many appeared satisfied with it. In addition to a one-time monetary payment, four respondents received wheat flour every year, one received rooms as additional compensation, and another received additional money every year. This seems to be an unequal, perhaps inappropriate, compensation scheme (or even a non-existent compensation scheme). In another developing country (Nepal), researchers indicated uneven benefit distribution which was largely restricted to people living close to tourism centers [43].

One reason for the failure to implement a reasonable compensation scheme might be the complexity of the top-down management system. The eight QZUGG scenic spots (Table 1) are managed by different government agencies (The Ministry of Forestry, Water Conservancy Bureau, Tourist Administration, and Bureau of Land Resources), although they are centrally managed by a QZUGG management office in Xi’an City. Negotiations and agreements for compensation might have been made with some, but not other, residents. Otherwise, it seems that there should have been more local residents in our sample to have been compensated. A close examination of the incomes of those 50 people reveals that almost one-half of them earned all of their income from Geopark-related employment (Table A6). Because the Geopark’s tourism business is seasonal, annual incomes must be rapidly ensured and generated during those months when the tourists visit. These circumstances help to explain the unhappy or angry respondents during the interviews, and it is not difficult to understand their dissatisfaction with the Geopark’s management officials.

To increase the local residents’ levels of satisfaction, good management is fundamental [38]. The combined efforts of eight scenic spots in applying for UNESCO Global Geopark status have created a contradiction. The integrity of a UNESCO Global Geopark requires unified action and conservation. However, these eight spots conduct tourism activities, development, and business independent of each other, and unification is difficult. This might create problems, such as unclear themes of the individual scenic spots because of variations in design and construction standards, as well as a lack of effective communication among them. These problems may reduce the numbers of visitors, which, in turn, may negatively affect local residents’ incomes.

The complex top-down management system of multiple administrative agencies adds inefficiency regarding the implementation of new policies or new management schemes. Therefore, efforts should be made to reform the system to be more unified. It is essential that policymakers and managers understand PAs and their status quo [3,43] as the basis of future activities. The QZUGG central management office should perform a thorough assessment of the four scenic spots toward achieving a balanced tourism resource distribution. Furthermore, an online communication platform should be established to improve cooperation.

5. Conclusions

The complex QZUGG management system requires better scrutiny. Currently, there is a lack of effective communication and cooperation among the eight scenic spots, which may negatively influence the Geopark. Multiple management agencies inevitably reduce the efficiency of the operations and create conflicts. A profit-sharing scheme that includes the local residents may improve their opinions of the Geopark, which is significant for the QZUGG’s future development and success. An online communication platform should be established for unified and coordinated activities, and a unified and more direct management system would benefit the Geopark and local residents. The Geopark administrators should provide more job opportunities to the local residents, which would increase their participation in Geopark activities, improve their knowledge of the Geopark’s value, and hopefully, raise their opinions of the Geopark. Geopark administrators would find that their jobs become less burdensome as local resident satisfaction improves.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. and T.W.; Data curation, L.C.; Formal analysis, L.C.; Funding acquisition, T.W.; Investigation, L.C. and T.W.; Methodology, L.C. and T.W.; Project administration, T.W.; Resources, L.C. and T.W.; Supervision, T.W.; Validation, L.C. and T.W.; Visualization, L.C.; Writing the original draft, L.C. and T.W.; Writing the review and editing, L.C. and T.W.

Funding

This research was partly funded by JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) Grant Number JP16H05641 (Teiji Watanabe).

Acknowledgments

Jian Ke of the Graduate School of Environmental Science helped to organize and prepare the reference list.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample characteristics of the respondents.

Table A1.

Sample characteristics of the respondents.

| Number of Cases | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | male | 78 | 47.6 |

| female | 86 | 52.4 | |

| Total | 164 | 100.0 | |

| Age | under 20 years | 12 | 7.3 |

| 20–30 years | 29 | 17.7 | |

| 31–40 years | 42 | 25.6 | |

| 41–50 years | 44 | 26.8 | |

| over 50 years | 37 | 22.6 | |

| Total | 164 | 100.0 | |

| Education level | middle school and less | 114 | 69.5 |

| high school | 32 | 19.5 | |

| college or university | 17 | 10.4 | |

| master or more | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Total | 164 | 100.0 | |

| Where are you from? | Locala | 149 | 90.9 |

| non-local | 15 | 9.1 | |

| Total | 164 | 100.0 |

a “Local” refers to respondents born in and currently residing in the community.

Appendix B

Table A2.

Employment and occupations of the respondents and their family members.

Table A2.

Employment and occupations of the respondents and their family members.

| Statements | Scenic Spots | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuihuashan | Wangshunshan | Zhuque | Taiping | |

| n = 43 | n = 42 | n = 41 | n = 38 | |

| % | % | % | % | |

| 1. This is your full-time job. | 62.8 | 95.2 | 73.2 | 68.4 |

| 2. If it is not your full-time job, what else do you do? | ||||

| 2.1. Civil servants | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| 2.2. Business staff | 7.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 2.3. Self-employed | 9.3 | 4.8 | 12.2 | 15.8 |

| 2.4. Teacher | 2.3 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| 2.5. Students | 14.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.3 |

| 2.6. Peasants | 2.3 | 0.0 | 7.3 | 5.3 |

| 2.7. Other | 2.3 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 |

| Total | 37.2 | 4.8 | 26.7 | 31.6 |

| 3. All my family member do the job related to this scenic area. | 34.9 | 28.6 | 43.9 | 36.8 |

| 4. Number of my family member doing the job related to this scenic area. | ||||

| 4.1. one | 11.6 | 38.1 | 26.8 | 31.6 |

| 4.2. two | 25.6 | 26.2 | 22.0 | 10.5 |

| 4.3. three | 18.6 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 13.2 |

| 4.4. four | 2.3 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| 4.5. five | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| 4.6. six | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 4.7. nine | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 |

| Total | 58.1 | 71.5 | 56.0 | 63.1 |

| 5. Number of my family member. | ||||

| 5.1. two | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 5.2. three | 4.7 | 9.5 | 7.3 | 10.5 |

| 5.3. four | 18.6 | 9.5 | 14.6 | 13.2 |

| 5.4. five | 20.9 | 21.4 | 22.0 | 15.8 |

| 5.5. six | 9.3 | 14.3 | 7.3 | 7.9 |

| 5.6. seven | 2.3 | 7.1 | 2.4 | 7.9 |

| 5.7. eight | 2.3 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| 5.8. nine | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 |

| 5.9. ten | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 5.10. eleven | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 |

| Total | 58.1 | 71.4 | 56.0 | 63.1 |

| 6. The kinds of job my family member do. | ||||

| 6.1. catering services | 90.7 | 83.3 | 97.6 | 97.4 |

| 6.2. accommodation service | 32.6 | 11.9 | 63.4 | 42.1 |

| 6.3. raw materials service | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 6.4. tour guide service | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 6.5. scenic area employee | 4.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 6.6. transport service | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 5.3 |

| 6.7. other | 2.3 | 14.3 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| Total | 132.6 | 111.9 | 163.4 | 147.4 |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Income and livelihood characteristics.

Table A3.

Income and livelihood characteristics.

| Statements | Scenic Spots | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuihuashan | Wangshunshan | Zhuque | Taiping | |

| n = 43 | n = 42 | n = 41 | n = 38 | |

| 1. The degree to which my income from this job account for my family’s total income | % | % | % | % |

| 1.1. one-fourth or less | 14.0 | 14.3 | 4.9 | 18.4 |

| 1.2. one-third or less | 11.6 | 11.9 | 7.3 | 5.3 |

| 1.3. half | 11.6 | 38.1 | 26.8 | 34.2 |

| 1.4. three-fourth or more | 20.9 | 19.0 | 14.6 | 13.2 |

| 1.5. all from it | 41.9 | 16.7 | 46.3 | 28.9 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 100.0 |

| 2. I have been always living here | 79.1 | 88.1 | 75.6 | 73.7 |

| 2.1. 20 years and under | 23.3 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 23.7 |

| 2.2. 20–40 years | 20.9 | 64.3 | 26.8 | 23.7 |

| 2.3. 40 years and above | 30.2 | 19.0 | 43.9 | 26.3 |

| Total | 74.4 | 88.1 | 75.6 | 73.7 |

| 3. I know this is a geopark (via) | 65.1 | 69.0 | 63.4 | 71.1 |

| 3.1. QZUGG official website | 11.6 | 0.0 | 7.3 | 7.9 |

| 3.2. GGN official website | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.3 |

| 3.3. Other cyber-resources | 7.0 | 0.0 | 9.8 | 10.5 |

| 3.4. Friends and relatives | 2.3 | 7.1 | 14.6 | 13.2 |

| 3.5. Travel agency | 2.3 | 31.0 | 7.3 | 5.3 |

| 3.6. Village committees and other government organizations | 27.9 | 33.3 | 12.2 | 23.7 |

| 3.7. Adervertisement of the geopark | 14.0 | 23.8 | 22.0 | 23.7 |

| Total | 65.1 | 95.2 | 73.2 | 89.6 |

Appendix D

Table A4.

Farmland requisitions for QZUGG.

Table A4.

Farmland requisitions for QZUGG.

| Statements | Scenic Spots | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuihuashan | Wangshunshan | Zhuque | Taiping | |

| n = 43 | n = 42 | n = 41 | n = 38 | |

| % | % | % | % | |

| 1. My land was taken over for use during the park construction. | 60.5 | 16.7 | 2.0 | 39.5 |

| 2. I received financial compensation. | 4.7 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 26.3 |

| 3. The degree to which the financial compensation satisfied me, | ||||

| 3.1. very dissatisfied | 0.0 | 57.1 | 0.0 | 60.0 |

| 3.2. dissatisfied | 0.0 | 42.9 | 0.0 | 20.0 |

| 3.3. neutral | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.0 |

| 3.4. satisfied | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.0 |

| 3.5. very satisfied | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 4. This Geopark provides bonus. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.5 |

| 5. The degree to which the bonus satisfied me, | ||||

| 5.1. very dissatisfied | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.0 |

| 5.2. dissatisfied | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7.9 |

| 5.3. neutral | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.6 |

| 5.4. satisfied | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.0 |

| 5.5. very satisfied | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.0 |

| Total | N/A | N/A | N/A | 10.5 |

| 6. This Geopark provides other forms of compensation. | 30.2 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

Appendix E

Table A5.

Relationship between type of employment and income contribution to total household income (percentage).

Table A5.

Relationship between type of employment and income contribution to total household income (percentage).

| My Income Accounting for My Family’s Total Income | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/4 or less | 1/3 | one-half | 3/4 or above | all | ||

| % | % | % | % | % | ||

| Full-time job or not | Yes | 10.6 | 7.3 | 26.0 | 17.9 | 38.2 |

| no | 19.5 | 14.6 | 31.7 | 14.6 | 19.5 | |

Appendix F

Table A6.

Annual income/total household annual income ratio of respondents whose farmland was requisitioned for the geopark (n = 50).

Table A6.

Annual income/total household annual income ratio of respondents whose farmland was requisitioned for the geopark (n = 50).

| Income Ratio | Cuihuashan | Wangshunshan | Zhuque | Taiping | % | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/4 or less | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6.0 | 3 |

| 1/3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.0 | 4 |

| half | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 12.0 | 6 |

| 3/4 or more | 9 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 28.0 | 14 |

| all | 11 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 46.0 | 23 |

| Total | 26 | 7 | 2 | 15 | 100.0 | 50 |

References

- Zhou, C.F.; Zhao, Y.Z.; Connelly, J.W.; Li, J.Q.; Xu, J.L. Current nature reserve management in China and effective conservation of threatened pheasant Species. Wildl. Biol. 2017, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butchart, S.H.M.; Walpole, M.; Collen, B.; Van Strien, A.; Scharlemann, J.P.W.; Almond, R.E.A.; Baillie, J.E.M.; Bomhard, B.; Brown, C.; Bruno, J.; et al. Global biodiversity: Indicators of recent declines. Science 2010, 328, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, N. Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008; ISBN 978-2-8317-1086-0. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, T.M.; Bakarr, M.I.; Boucher, T.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Hoekstra, J.M.; Moritz, T.; Oliveri, S.; Parrish, J.; Pressey, R.L.; Rodrigus, A.S.L.; et al. Coverage provided by the global protected-area system: Is it enough? BioScience 2004, 54, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzinada, A.H. The role of protected areas in conserving biological diversity in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Arid Environ. 2003, 54, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldmann, J.; Barnes, M.; Coad, L.; Craigie, I.D.; Hockings, M.; Burgess, N.D. Effectiveness of terrestrial protected areas in reducing habitat loss and population declines. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 161, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldmann, J.; Barnes, M.; Coad, L.; Barnes, M.; Craigie, I.; Hockings, M.; Burgess, N. Changes in protected area management effectiveness over time: A global analysis. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 191, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnley, S.A.; Fischer, A.P.; Jones, E.T. Integrating traditional and local ecological knowledge into forest biodiversity conservation in the Pacific Northwest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 246, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A.; Cunningham, A.; Byarugaba, D.; Kayanja, F. Conservation in a region of political instability: Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, Uganda. Conserv. Biol. 2000, 14, 1722–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.E.M.; Dudley, N.; Segan, D.B.; Hockings, M. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature 2014, 515, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFries, R.S.; Karanth, K.K.; Pareeth, S. Interactions between protected areas and their surroundings in Human-Dominated Tropical Landscapes. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 2870–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protected Planet. Available online: https://Protectedplanet.Net/Search?Country=China&q=China (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- Xu, H.G.; Tang, X.P.; Liu, J.Y.; Ding, H.; Wu, J.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Q.W.; Cai, L.; Zhao, H.J.; Liu, Y. China’s progress toward the significant reduction of the rate of biodiversity loss. BioScience 2009, 59, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.G.; Linderman, M.; Ouyang, Z.; An, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H. Ecological degradation in protected areas: The case of Wolong Nature Reserve for Giant Pandas. Science 2001, 292, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, M.T.; Nepstad, D.C. Smallholders, the Amazon’s new conservationists. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 1553–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coad, L.; Burgess, N.; Fish, L.; Ravillious, C.; Corrigan, C. Progress towards the convention on biological diversity Terrestrial 2010 and Marine 2012 Targets for protected area coverage. Parks 2009, 17, 35–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanth, K.K.; Nepal, S.K. Local residents perception of benefits and losses from protected areas in India and Nepal. Environ. Manag. 2012, 49, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutanga, C.N.; Vengesayi, S.; Muboko, N.; Gandiwa, E. Towards harmonious conservation relationships: A framework for understanding protected area staff-local community relationships in developing countries. J. Nat. Conserv. 2015, 25, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, G. Exploring the relationship between local support and the success of protected areas. Conserv. Soc. 2013, 11, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, M.E.; Lilieholm, R.J.; Ashenafi, Z.T.; Leader-Williams, N. Community attitudes toward wildlife and protected areas in Ethiopia. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allendorf, T.D.; Aung, M.; Swe, K.K.; Songer, M. Pathways to improve park-people relationships: Gendered attitude changes in Chatthin Wildlife Sanctuary, Myanmar. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 216, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struhsaker, T.T.; Struhsaker, P.J.; Siex, K.S. Conserving Africa’s rain forests: Problems in protected areas and possible solutions. Biol. Conserv. 2005, 123, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redpath, S.M.; Young, J.; Evely, A.; Adams, W.M.; Sutherland, W.J.; Whitehouse, A.; Amar, A.; Lambert, R.A.; Linnell, J.D.C.; Watt, A.; et al. Understanding and managing conservation conflicts. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockington, D. Community conservation, inequality and injustice: Myths of power in protected area management. Conserv. Soci. 2004, 2, 411–432. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, A.G. Effectiveness of parks in protecting tropical biodiversity. Science 2001, 291, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.T.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, W.; Zha, F.Y. Geoheritages in the Qinling orogenic belt of China: Features and comparative analyses. Geol. J. 2018, 53, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T. Protection of geoheritage and development of tourist resources in the Qinling Zhongnanshan Geopark. Geol. Shaanxi 2009, 27, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Qinling Zhongnanshan UNESCO Global Geopark. Available online: http://www.qlzns.com/ynews/show-382.html (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- Wong, K.; Fu, D.; Li, C.Y.; Song, H.X. Rural migrant workers in urban China: Living a marginalised life. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2007, 16, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/shuju/2017-08/20/content_5219043.htm (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- Teye, V.; Sirakaya, E.; Sönmez, S.F. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 668–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocănea, C.M.; Sorescu, C.; Ianoşi, M.; Bagrinovschi, V. Assessing public perception on protected areas in Iron Gates Natural Park. Procedia Soc. Behav. 2016, 32, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvenegaard, G.T.; Dearden, P. Linking ecotourism and biodiversity conversation: A case study of Doi Inthanon National Park, Thailand. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 1998, 19, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, N.; Halim, S.A.; Liu, O.P.; Saidin, S.; Komoo, I. Public education in heritage conservation for geopark community. Procedia Soc. Behav. 2010, 7, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walpole, M.J.; Goodwin, H.J. Local attitudes towards conservation and tourism around Komodo National Park, Indonesia. Environ. Conserv. 2001, 28, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookbinder, M.P.; Dinerstein, E.; Rijal, A.; Cauley, H.; Rajouria, A. Ecotourism’s support of biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Biol. 1998, 12, 1399–1404. [Google Scholar]

- West, P.; Igoe, J.; Brockington, D. Parks and peoples: The social impact of protected areas. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2006, 35, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbi, S.; Linkie, M.; Leader-Williams, N. Evaluating the legacy of an integrated conservation and development project around a tiger reserve in India. Environ. Conserv. 2008, 35, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandbrook, C.G. Local economic impact of different forms of nature-based tourism. Conserv. Lett. 2010, 3, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyere, B.L.; Beh, A.W.; Lelengula, G. Differences in perceptions of communication, tourism benefits, and management issues in a protected area of rural Kenya. Environ. Manag. 2009, 43, 19–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, H.; Ruhanen, L. Power in tourism stakeholder collaborations: Power types and power holders. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiteri, A.; Nepal, S.K. Evaluating local benefits from conservation in Nepal’s Annapurna Conservation Area. Environ. Manag. 2008, 49, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiman, D.G.; Reading, R.P.; Miller, B.J.; Clark, T.W.; Scott, J.M.; Robinson, J.; Wallace, R.L.; Cabin, R.J.; Fellerman, F. Improving the evaluation of conservation programs. Conserv. Biol. 2000, 14, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).