Abstract

This review explores the complex environmental and human health issues facing the Navajo Nation, USA and focuses on arsenic and uranium pollution in vital drinking water sources. Located in the Southwestern United States, with territory comparable to the size of Ireland, these are the homelands of the indigenous Navajo people. Rich in coal, natural gas, and oil, Navajo lands have been a critical target for resource exploitation over the past century. Uranium and arsenic are the two most widespread geogenic contaminants and are also common contaminants associated with mining and other anthropogenic sources in this region. The legacy of uranium mining during the Cold War era on the Navajo Nation has left significant environmental damage to the land and vital drinking water sources in these arid lands. There is an estimated 20 to 30% lack of public water systems in the Navajo Nation, creating a reliance on water hauling for many Navajo families. This reliance often results in the use of potentially harmful contaminated domestic water sources for Navajo families who must gather water from unregulated but available resources. The contamination of drinking water sources poses significant health risks to the Navajo people, who already endure the combined effects of inadequate public infrastructure, a struggling economy, and persistent poverty. There are present and on-going efforts from several key groups and organizations working to address these challenges. However, there is continued need for remediation and mitigation efforts, research, and community involvement to address this critical environmental justice issue and ensure equal access to safe drinking water for the Navajo people.

Keywords:

drinking water; arsenic; uranium; Navajo; mining; tribal; indigenous; environmental health 1. Introduction

Clean water is essential for life, yet for numerous Indigenous communities, this fundamental resource is often impacted by pollution. The historical exploitation of natural resources to Indigenous lands in the United States (U.S.) and elsewhere across the globe has led to environmental contamination, displacement, loss of traditional and cultural practices, violating human rights, and worsening disparities [1,2,3]. Indigenous communities have often received little to no profit from the exploitation of their natural resources, yet they are the ones who ultimately bear the impacts and responsibilities of environmental damage to their homelands [4]. Drinking water is a primary route for human exposure to environmental pollutants, and this is critical because heavy metal contamination in drinking water in tribal communities is frequently overlooked [5]. Tribal populations disproportionately suffer from illnesses linked to poor water quality, a problem worsened by significant deficits in essential water infrastructure and the consumption of water from unregulated sources, particularly in areas with historical mining [5,6]. In 2012 the U.S. Indian Health Service articulated their relationship of sanitary water as “Improving the environment in which people live and assisting them to interact positively with that environment results in significantly healthier populations” [7].

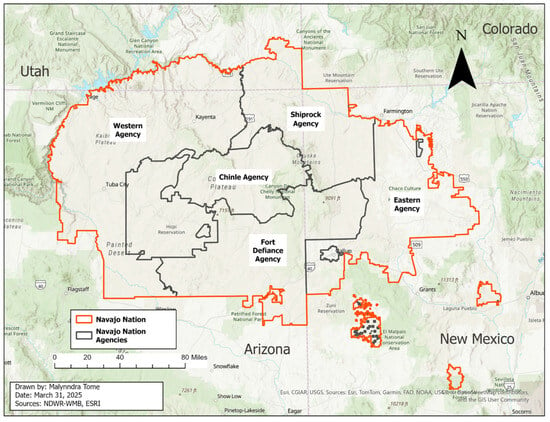

Established in the Four Corners region of the Southwestern United States are the homelands of the Navajo people. The Navajo Indian Reservation, also known as the Navajo Nation (NN), is located within the Colorado Plateau. Primarily a high desert ecosystem, the area is characterized by low precipitation, varying elevations, and diverse geological features like canyons, mesas, and badlands. The NN includes over 27,000 square miles (>71,000 square kilometers), spans across three states (Arizona, New Mexico, Utah) and has been compared to the size of the U.S. State of West Virginia. There are 110 chapters or communities within the NN, which are divided among five management agencies (Western Agency, Chinle Agency, Fort Defiance Agency, Eastern Agency, and Shiprock Agency) [8]. Chapters are the local government subdivisions of the Navajo Nation. The vast geographic land base and large tribal enrollment population of nearly 400,000 make the NN the largest American Indian tribal nation in the United States [9,10]. Approximately 160,000 Navajo people live in the NN, according to the 2020 Census [9]. It should also be noted that the NN has been categorized as a rural area, with a population density of 6.02 people per square mile [9]. Figure 1 provides a map of the NN boundaries and agencies located within the NN.

Figure 1.

Map of Navajo Nation (NN) and NN Agencies.

The 2003 Navajo Nation Drought Contingency Plan prepared by the NN Department of Water Resources (NNDWR) includes a description of the regional climate. The NN has been recorded to have large variations in temperature and rainfall with distinct wet (winter and summer) and dry (spring and fall) seasons [11]. The wet seasons differ significantly in how precipitation occurs and where it falls. Winters have been recorded to bring widespread, low-intensity precipitation, with snow in higher elevation areas, from frontal storm systems. Summer, on the other hand, sees monsoonal moisture from the subtropics fueling localized, intense convective storms, leading to a very uneven distribution of rainfall across large areas like the Navajo Nation [11]. Some areas of the NN have been reported to receive less than eight centimeters of precipitation per year and other areas receive an average of twenty to thirty centimeters per year [12]. The Navajo Nation sits within the Colorado Plateau and the major water basins of the NN are the Upper and Lower Colorado River Basin. The three largest basins on and in proximity to the NN are the San Juan Basin, Black Mesa Basin, and the Blanding Basin [13]. The NN currently relies on groundwater as its primary and most consistent municipal water supply [14]. Ranging from various depths and capacities, the NN currently accesses approximately 20 groundwater aquifers [13]. For municipal and domestic water use, the main source of aquifers for Navajo communities comes from, shallow to deep, alluvial aquifer systems, the Mesa Verde group, Dakota (D), Navajo (N), and Coconino (C) aquifers [13].

The semi-arid climate of the NN, characterized by low and infrequent precipitation events coupled with increasing temperature that drives high evaporation rates, severely constrains the availability of surface water [11]. These climatic limitations create a heavy reliance on groundwater for the most stable domestic water source [11]. Inadequate infrastructure and drought-like conditions of the NN dictate the consumption patterns where a significant portion of the Navajo population must haul water, which results in the regions lowest per capita water usage rates [14].

It has been estimated by the NNDWR that approximately thirty percent of households in the Navajo Nation lack safe, reliable, and affordable access to clean water and indoor plumbing [14]. With a great land area and a sparse population, building extensive water infrastructure across the remote and rough terrain can be extremely expensive and difficult [14]. The lack of infrastructure has led to the reliance on water hauling for many Navajo families. This reliance often results in the use of water sources that are not regulated or monitored, such as stock ponds, historical wells, or springs. It has been documented that many Navajo water haulers commonly drive long distances to reach a regulated centralized water source [14,15,16] Additionally, water transportation cost is high because of factors such as vehicle wear and tear, mileage, and hauling time [16] Navajo families who must haul water pay substantially more for their water compared to families in suburban areas. In situations where accessing regulated water is challenging, the closest and often unregulated water source becomes the primary and vital source for livestock, household use, small gardens, and residential consumption [12,15]. Several studies have also documented that unregulated water sources in the NN regularly exceed the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s (USEPA) Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCL) allowed in drinking water for uranium and arsenic [6,15,17]. Natural mineral reserves, historical mining, and inadequate water infrastructure in Navajo raise the risk of exposure to inorganic pollutants through uncontrolled water sources.

The objective of this review was to synthesize the current research, action plans, and policy effects on the arsenic and uranium environmental and human health impacts within the U.S. Navajo Nation. We investigated the legacy of historical mining, the documented contamination of drinking water, and the systemic barriers to accessing clean water.

2. Occurrence, Fate, and Transport of Uranium (U) and Arsenic (As) in the Environment

Naturally formed As is present in significant quantities within the Earth’s crust. Although As is categorized as a metalloid, exhibiting properties intermediate between those of metals and nonmetals, it is commonly referred to as a metal [18]. Low levels of the element can be found in all environmental media with varying concentrations from rural to urban areas [18]. The concentration of As in soils varies widely; however, soils in the vicinity of As rich geological deposits as well as some mining and smelting sites may contain higher levels of As [18]. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry documents the concentration of As in natural surface and groundwater as generally about 0.001 mg/L but may exceed 1 mg/L in contaminated areas where As levels in soil are high. Ground water is far more likely to contain high levels of As than surface water [18,19]. This is due to two primary geochemical mobilization mechanisms favored by underground conditions; the most common mechanism being the reductive dissolution of iron oxyhydroxides (FeOOH) [20]. In low oxygen environments of aquifers, anaerobic bacteria use the Fe3+ in iron oxides as a substitute for oxygen respiration. This process releases both soluble Fe2+ and the highly mobile AsIII [20].

The radioactive element U also occurs naturally. Present in almost all soils and rocks, it has an average concentration of approximately 3 mg/kg in U.S. soils [21]. Naturally elevated U levels in the Western U.S. are due to the geological formations of the region [21]. The three isotopes that make up natural U are U234, U235, and U238. U238 is the most prevalent isotope and accounts for ninety-nine percent of the mass of natural U. Although each isotope has its own radioactive characteristics, together they exhibit some similar chemical behavior such as oxyanion formation. In the case of isotopic U radiochemical decay, the time for this process can be extensive. The half-life of U238 is 4.5 billion years and U235 is 704 million years [21]. Uranium presence in the environment for extremely long periods of time indicates persistence and the potential for long term radiological risks to human health.

The global contamination of U is a critical environmental health issue, often linked to naturally elevated levels and anthropogenic pollution from mining activities. For instance, in South Africa’s Gauteng Province, gold mining has resulted in widespread residential pollution from uranium rich mine tailings [22]. The Zupunski et al., 2023, study found that children in Northeast Soweto in Johannesburg, South Africa, had significantly elevated mean U concentrations in their hair compared to non-exposed populations globally [22]. Elevated exposure did not correlate with proximity to mine tailings, which suggests that exposure is driven by complex exposure pathways beyond windblown dust, such as contaminated local streams, soil ingestion, and possibly crops irrigated with contaminated water [22].

In Iran’s arid Rafsanjan plain, a study completed by Rahnamarad et al., 2020, found that more than 80% of groundwater samples contained arsenic concentrations exceeding World Health Organization guidelines for drinking water [23]. Although the area’s volcanic geology is a major source of arsenic, the groundwater is susceptible to contamination from the adjacent Sarcheshmeh copper mine [23].

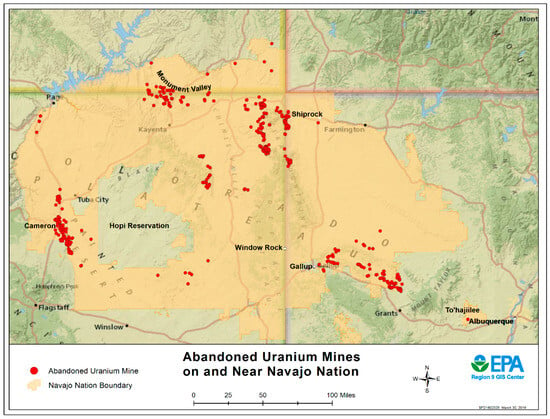

U and As are the two most naturally occurring and widespread contaminants, but their spread has been exacerbated by human activities like mining [24]. As cited in Credo et al., 2019, the geology of the Four Corners region is rich in coal, copper, U, and vanadium [15]. Mining for vanadium, co-occurring with U in mineral carnotite, was mined in the Navajo Nation beginning in the early 1900s [25]. Vanadium has a primary use in strengthening steel alloys. During the time of the Cold War, the Navajo Nation was the largest domestic producer of U ore [15,26]. According to the USEPA, fifty thousand metric tons of U oxide was extracted from mines in the NN between the early 1940s and late 1980s [6]. Past mining activities resulted in an estimated 1200 mine sites and/or features and over 500 abandoned uranium mine (AUM) sites [12,27]. Figure 2 shows a map developed by USEPA of AUM on Navajo Lands. Many Navajo communities continue to be chronically exposed to these waste sites, as these sites are in and proximal to their communities [25].

Figure 2.

Abandoned Uranium Mines on and near the Navajo Nation from the USEPA Region 9 GIS Center [28].

Arsenic is naturally present in the geology and soil of the Southwestern U.S., and the levels in groundwater can be high due to chemical and microbial processes, dissolution, high evaporation, and past and present mining operations [12]. These factors combine to create a significant problem of elevated As in drinking water sources in the region [12]. As and U tend to occur together because they both become more soluble when oxidized and can precipitate into the same minerals. As a result, they are often found in high concentrations together, particularly where U has been mined [12]. U and As are documented to co-occur more frequently in the Navajo Nation than throughout the rest of the U.S. [6]. Although there is limited data on the link between historical U mining and widespread contamination of groundwater in the NN, Hoover et al., 2017, observed that unregulated water sources located closer to AUM more frequently exceeded As and U drinking water standards [6].

Described in Ingram et al., 2020, mining can increase the naturally elevated levels of As and U, by releasing tailings waste that contains significant levels of As and U and can potentially enter groundwater [27]. The process of acid rock drainage (ARD) can cause significant concentrations of dissolved metals in areas with natural mineral deposits [27,29]. All sulfide minerals undergo ARD, a natural process brought on by weathering, microbial action, and oxidation that mobilizes metals [29]. Acid mine drainage (AMD) is a kind of ARD which results from mining operations that increase the acidity of waterways by exposing pyrite and other sulfide minerals to oxygen and water sources more frequently; as a result it raises the levels of dissolved metals in water in a process impacting the NN environment [27,29].

The 1979 accidental release of 352 million liters of radioactive and contaminated tailings waste into the Puerco River as a result of a tailings ponds breach from a former U mill demonstrates the severe and long lasting environmental and public health consequences [30]. This largest release of radioactive material in the U.S. occurred on the NN in the community of Church Rock, NM [31,32]. The release also impacted the downstream city of Gallup, NM. The deLemos et al., 2008, study on the Upper Puerco River watershed, located within the Church Rock, Pinedale, Coyote Canyon, Nahodishgish Chapters, observed the rapid dissolution of soluble U compounds in the region’s sediments [31]. These compounds contain U in its highly mobile and soluble +6 oxidation state [31]. It was interpreted that the rapid dissolution leads to the mobilization of U, increasing the dissolved U concentration in water. The arid conditions of the NN and the lack of precipitation are a key factor in the dissolution and transport process. Although precipitation events are infrequent, when they do occur, they can lead to the flushing of U from the sediment. The rapid dissolution and mobilization process is understood to recur episodically whenever significant, infrequent precipitation events flush the accumulated U from the sediments. The dissolved and mobilized U can contaminate surface and groundwater sources, potentially impacting drinking water and ecosystems [31].

Arsenic is found naturally in soil and minerals. It can enter the air through dust carried by the wind and enter waterways through runoff and leaching [18,33]. Ores that contain metals like lead and copper are linked to As. Therefore, the mining and smelting of these ores can release As into the environment. Coal fired power stations and incinerators also discharge small amounts of As into the atmosphere because coal and waste products often contain some As. Several common As compounds are soluble in water; these compounds can enter lakes, rivers, or groundwater through precipitation or the release of industrial waste [18,33]. Alternatively, volcanic eruptions and erosion by wind and water can release U into the environment. U may also be released into the environment from industrial sites involved in U mining, milling, and processing. Inactive U operations may also still release U into the environment [21].

The environmental oxidation states of As and U are directly responsible for their high mobility and toxicity on the NN. The dry and arid climate of the NN can create an oxidizing environment. The highly mobile, hexavalent form of U (UVI) is the uranyl ion (UO22+). This species is highly soluble in water, readily leaching from mine waste and moving easily through soil and groundwater. Arsenic’s environmental mobility and speciation are governed by redox conditions. The two common oxidation states are arsenite (AsIII), which predominates in reducing environments, and arsenate (AsV), the stable form in oxygenated conditions. In the environment, AsIII and AsV form the triprotic oxyanions arsenous acid (As(OH)3) and arsenic acid (AsO(OH)3), respectively. Arsenate is a chemical analog of phosphate. Thus, it can be mistakenly taken up by plants and microorganisms through phosphate transport proteins, thereby increasing its potential for toxicity.

Extensive U mining in NN lands left behind numerous abandoned mines and milling sites [26]. These sites are persistent sources of contamination that can leach into soil and groundwater. U can dissolve in groundwater and be transported over long distances, contaminating drinking water sources. Particles can be carried by wind, leading to inhalation exposure. Runoff from contaminated sites can carry U into streams and rivers. U can persist in the environment for long periods due to its long half-lives. U can accumulate in soil and groundwater, posing ongoing risks [21].

Arsenic’s natural occurrence in the geology of the NN can lead to elevated As levels. Mining activities have been correlated with the exacerbation of As contamination by releasing it from rocks [25]. Acid mine drainage increases the mobilization of As. Arsenic is highly mobile in groundwater, making it a significant concern for drinking water contamination. It is like U in that surface water runoff can transport As to other surface water sources. Arsenic can accumulate in soil and sediments and its persistence in groundwater can lead to long term human exposure [18].

3. Toxicological Implications of U and As

3.1. Levels of U and As in Drinking Water

For most people, food and drinking water are the main sources of U exposure [21]. In most areas of the U.S. low levels of U are found in drinking water; high levels may be found in areas with elevated levels of naturally occurring U in rocks and soil [21]. The primary exposure route for people in the NN is contaminated drinking water [6,27,34]. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) established a maximum contaminant level (MCL) for U of 0.030 mg/L in drinking water [35]. The USEPA revised the drinking water standard from 0.050 to 0.010 mg/L for As in drinking water in January of 2001 [36]. These As and U drinking water standards match World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for drinking water quality [37].

The USEPA approved the Navajo Nation Public Water System Supervision Program (PWSSP), as meeting all the requirements to implement and enforce the federal Safe Drinking Water Act and federal regulatory requirements for Public Water Systems (PWS). This action allows the NN to have primacy over all PWS in the NN, including tribal trust lands [38]. The Navajo Nation has established specific water quality standards for both its surface water resources and drinking water sources. These standards are actively monitored at designated wells to ensure compliance and prevent potential negative health effects within the community. The Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency (NNEPA) operates the water quality program and holds the responsibility for enforcing these regulations. The standard for domestic water supply mandates that U levels do not exceed 0.030 mg/L, and As levels are set at 0.010 mg/L [38]. In addition to domestic water standards, the Navajo Nation established a maximum As level of 0.200 mg/L for water intended for livestock [39]. The NNEPA’s current regulations do not include a maximum contaminant level for U in livestock water [39].

Several studies have been carried out to comprehend the regional variability of U and As pollution in groundwater. These studies have all revealed that As and U surpass the USEPA drinking water standards in unregulated water sources. Unregulated sources that are located closer to AUM were higher in concentrations of As and U than more distant water sources [6]. Additionally, locations where the water wells exceeded the USEPA guidelines corresponded to locations where As and U contamination might be expected based on geological characteristics [40].

In recent work, Jones et al., 2020, collected 82 water samples from unregulated wells in the Western agency of the NN [12]. It focused on twelve chapters, seven of which were located within the western AUM region. The highest levels of U and As were found in the southwestern portion of Coalmine Canyon Chapter. Nine unregulated sources exceeded U MCL, and 14 exceeded As MCL. The highest levels of U were found in the southwestern portion of the study area (Western agency), this part of the study area has the highest concentration of AUM. Indicating that mining activity could be responsible for the elevated levels. However, since pre-mining baseline levels are unknown, it is not definitive to determine the source [12].

A 2017 study by Hoover et al. combined 25 years of water quality data for unregulated sources across the Navajo Nation. This information came from water quality surveys conducted by tribal, federal, and academic organizations [6]. The combined dataset contained water quality data for a total of 464 distinct unregulated sources located on Navajo lands. While As and U were often found together and correlated in about half of Navajo water sources, the overall percentage of sources exceeding the MCLs for both contaminants were 3.9%. More than 7% of unregulated sources in the Western Agency exceeded the safety limits for both As and U simultaneously [6]. A summary of this analysis can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

A comparison of USEPA and NNEPA regulatory standards with Hoover et al., 2017, observed As and U levels in 464 unregulated sources on NN [6]. * Exceeds MCL for both As and U.

In another study completed by Hoover et al. in 2018, the research utilized Bayesian clustering and spatial scan statistics to identify areas where sources exhibit similar contaminant profiles and where those contaminated sources are geographically clustered [34]. The study identified seven water quality clusters that exhibited similar profiles of metal and metalloid contaminants. It was found that As, U, lead, and manganese frequently co-occur in some unregulated water sources. Spatial clustering of these contaminant mixtures was observed across the study area. Several contaminant profiles contained concentrations of metals and metalloids that could pose a risk for human toxicity—specifically As, U, lead, manganese, and selenium [34].

3.2. Levels of U and As in the Human Body

People who work with materials and products that contain U may have occupational exposure. This includes workers who mine, mill, or process U or make items that contain U. People who live near U mining, processing, and manufacturing facilities could be exposed to more U than the general population [21].

During the U boom on the Colorado Plateau, thousands of Navajo men were employed in the mines. Navajo miners were largely uninformed about the severe health risks associated with radiation exposure, and despite the known link between U mining with high rates of lung cancer, few protections were provided for Navajo miners [26]. Many miners used U-laden rocks from mines to construct their homes, unknowingly exposing their families [26]. For decades, miners and their families suffered from direct and indirect health effects, including alarmingly high rates of lung cancer, pneumoconiosis, other respiratory diseases, and various other illnesses such as kidney disease and diabetes [26].

In addition, residential radon exposure may occur due to naturally high uranium concentrations in the soil or hazardous waste sites such as abandoned uranium mines and mill tailings [41]. As described in Yazzie et al., 2020, according to the U.S. EPA radon zone map, NN residents are predicted to have indoor radon concentrations between 74.0 and 148.0 Bq/m3 of radon gas [41]. This is higher than the national indoor average radon level in the U.S. which is approximately 50.0 Bq/m3 [42]. According to the U.S. EPA, radon exposure is estimated to cause thousands of lung cancer deaths annually in the U.S. and that radon levels less than 50.0 Bq/m3 can still pose a risk [43].

U can enter the body through inhalation, food, skin contact or drinking water. When U is swallowed, only a small fraction (0.1–6%) is absorbed into the bloodstream via the digestive system [21]. Water-soluble U compounds are absorbed more readily than those that do not dissolve easily in water. Most ingested U is not absorbed and is expelled in feces, while absorbed U is eliminated in urine. Absorbed U is deposited throughout the body, with the highest levels in bones, liver, and kidneys. A significant amount (66%) is stored in bones and can persist there for a long time, with a half-life of 70–200 days. U not stored in bones is generally eliminated from the body within one to two weeks [21]. Soil ingestion for infants and children due to house dust, crawling, hand to mouth behaviors, and pica, a condition of direct soil ingestion, have been explored as vectors for lead exposure [44,45]. While no specific data has been developed for U, house dust and contaminated play area soil exposure may contribute to hazard levels of Navajo children in some regions of the NN.

The levels of U and other metals in pregnant Navajo women were examined in the Hoover et al., 2020, study, and it compared the levels to those of the general population. The study found that pregnant Navajo women had higher levels of U, manganese, cadmium, and lead in their urine compared to the general US population [46]. This study highlighted a significant concern: pregnant Navajo women have detectable U and other metals in their urine, likely due to contamination and exposure vectors from abandoned U mines and facilities [46]. Their median urinary U concentrations, as measured in the Navajo Birth Cohort Study (NBCS), were 2.6 to 2.8 times greater than those of women in the National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey (NHANES) [46]. This indicates that pregnant Navajo women experience higher exposure to metal mixtures and significantly elevated U levels, with some exceeding health-based reference points and raising concerns about potential toxic effects. These findings are of considerable concern regarding prenatal exposure risks, as heavy metals are known to cross the blood–placental barrier and potentially disrupt fetal development.

It is unlikely to be able to live in an environment free of As due to its high industrial use in products and presence in many foods. It is used in making semiconductors, herbicides, pesticides, fertilizers, paints, cosmetics, glass industry, fireworks, ammunitions, etc. Exposure to As includes food, air, soil, and water [47]. The primary exposure route for people in the NN is contaminated drinking water [6,27,34]. Once ingested, As is quickly absorbed, and the amount absorbed depends on how much and the specific As chemical moiety consumed [18]. The body eliminates As through urine. Inorganic As can stay in the body for days to months, but organic As, such as arsenobetaine found in fish, is typically eliminated within a few days [18].

The Thompson González et al., 2022, study found that pregnant Navajo women participating in the NBCS had considerably higher than the U.S. national average biomonitoring levels of As species (i.e., AsIII, MMA, DMA), reported in the NHANES [48]. The study suggests that As species are immunosuppressive, which modulates the mother’s immune system potentially resulting in long term health issues for both the mother and child [48]. It was referenced in this study that As and its species can cross the blood–placental barrier, raising the risk of infant mortality [48,49]. This is of considerable concern for the health and livelihood of pregnant Navajo women and children who are exposed through environmental pathways.

Furthermore, dust is an important, ongoing route of exposure to U and As in addition to contaminated water from abandoned uranium mine waste sites in the NN [46]. Harmon et al., 2017, found that cardiovascular risk which is likely driven by an alternate exposure pathway—specifically the inhalation of windblown metal rich dust from abandoned mine sites—remains a major public health hazard for NN residents living near these waste sites [50].

4. Health Effects of U and As and the Role of Co-Contaminants

Natural and depleted U have identical chemical effects on the body. It is noted that the health effects of natural and depleted U are due to chemical effects and not to radiation [21]. Kidneys are documented to be the main target of U, as kidney damage has been consistently observed in humans and animals after the inhalation or ingestion of U compounds [21]. Consuming water-soluble U compounds can have harmful effects on the kidneys at much smaller doses than the consumption of insoluble U [21]. Water soluble compounds are more easily absorbed by the body and can enter the bloodstream more quickly, allowing them to reach and affect the kidneys. Insoluble compounds, which are not easily absorbed, can quickly pass through the body.

While studies have documented health risks like kidney diseases, hypertension, and other chronic illnesses for people living near AUM, there is a significant gap in our understanding of the health consequences of past mining, specifically for tribal communities [5,12]. However, an important finding of the 2025 Strong Heart Family Study (SHFS) reveals a link between chronic U exposure and high blood pressure and hypertension in tribal communities in the Southwest and Great Plains [51]. While progress is being made in understanding the harmful effects of U, we still do not fully understand the specific mechanisms behind its toxic chemical effects [51].

Inorganic As has been known as a deadly poison for centuries; large oral doses can result in death. Ingesting As is also linked to an increased risk of liver, bladder, and lung cancer [18,33,52]. Health authorities like the Department of Health and Human Services, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), and the USEPA have all classified inorganic As as a known human carcinogen [18,33,52].

Long-term As exposure, as highlighted by sources in 2023 Singh et al., is associated with a greater likelihood of developing cancers in various organs, including the liver, kidney, prostate, skin, bladder, and lungs [47]. This is a consequence of arsenic’s ability to trigger oxidative stress, damage DNA, mutate cells, and inhibit enzymes within the body [47]. Arsenic can be neurotoxic causing neuropathy, and it can cross the blood–brain barrier. It does this by making mitochondrial membranes unstable, disrupting neurotransmitters, and interfering with enzymes. Its ability to cross the placental barrier also means it can reach the fetuses from mothers, potentially leading to negative pregnancy outcomes. Skin disorders are another reported consequence of As toxicity [47].

Beyond As and U, results from 2019 Credo et al. demonstrate an elevation above USEPA guidelines and United States Geological Survey average water concentration of four other metals (Cd, Li, Mn, V) [15]. Hoover et al., 2018, discusses contaminants of concern and the public health implications of lead and manganese found in unregulated water sources in the NN [34]. Manganese is an essential dietary nutrient; however, excessive amounts can cause neurologic impairment [53]. Lead is a neurotoxin and the presence of it in drinking water is a potential public health concern, especially when elevated blood lead levels occur in infants and children. Lead has been associated with decreased cognitive function in children, as well as cardiovascular and renal problems [45]. There is a potential for study to examine if other contaminants may pose measurable health effects in those exposed in the NN, especially in a chronic co-exposure context [54,55].

A healthy diet rich in nutrients can provide a buffer against potentially toxic metals in the environment. Essential minerals such as iron, calcium, zinc, antioxidants, and fiber all offer protective barriers against toxic heavy metals [56]. However, for individuals living in food deserts, people may lack these protective nutrients, making them more vulnerable to heavy metal toxicity. Heavy metals have been documented to mimic or displace essential minerals that the body needs [56]. In a study of neurotoxic metals in iron-deficient children, it was explained that the body’s iron absorption mechanisms are like those for other divalent metals such as cadmium and lead. When iron stores are low, the expression of the cell membrane transport protein, Divalent Metal Transporter 1, increases, leading to more efficient absorption of not only iron but potentially toxic metals as well [53,56].

In the U.S., the Navajo Nation experiences the highest rate of food insecurity [57] and is classified by the USDA as a food desert [58]. A food desert is characterized by low wealth and limited access to healthy food like fresh produce and lean proteins. The Navajo Nation, with a vast land area, has only thirteen grocery stores [10,57,59]. Many Navajo families must drive long distances, often 30 min to 1 h to reach the closest grocery store [60]. Families may also choose to travel off the reservation to border towns to purchase food in bulk. Food purchases often consist of nutrient-poor, energy-dense, and prepackaged foods that have a longer shelf life. This trend is often influenced by factors such as low income, food insecurity, and the widespread availability of less nutritious, affordable options [10,60]. These kinds of foods have been linked to diabetes, obesity, coronary heart disease, hypertension, and other chronic illnesses [57]. It has been documented that the purchasing of healthy food is impacted by a family’s proximity to the grocery store, product shelf life, and price of food [10]. A healthier traditional diet has historically been a staple of Navajo culture. However, poverty, poor policies, and inefficient food distribution systems have combined to cause the rise of chronic disease like diabetes and food insecurity [10].

There are twelve healthcare facilities on or around the NN, covering the twenty-seven thousand square miles of Navajo land, serving over 175,000 Navajo people [61]. The NN has been classified as a medically underserved area by the Arizona Department of Health Services [62] The most vulnerable to the lack of equal access to healthcare are children, the elderly, and pregnant women, as we have seen from recent studies. More research is needed to assess the specific risks to these populations. In addition to the significant lack of infrastructure of waterlines and electricity, there is also a significant lack of paved roads. Two thirds of the fourteen thousand roads within NN are not paved, making the commute to essential services such as medical care, school, work, water hauling, and grocery stores a challenge [57,63]. Inclement weather has been known to worsen the already inadequate road infrastructure, posing extra difficulties, especially in emergencies [57].

Although we understand there are health risks, we still do not fully understand how common specific health problems occur or how they are distributed, especially when people are exposed to multiple contaminants and disease vectors at once. Box 1 demonstrates how systemic inequalities can intensify the impacts of environmental pollution on vulnerable populations.

Box 1. Economic and social influences can worsen the impacts of environmental contamination on vulnerable NN populations.

1. Lack of Water Infrastructure

- Associated Challenge: An estimated 20–30% lack public water systems and indoor plumbing in the region.

- Direct Influence: This necessitates a reliance on water hauling.

- Influence on Contamination Exposure:

- ○

- Increases reliance on unregulated, potentially contaminated water sources (stock ponds, springs).

- ○

- Raises the risk of exposure to Arsenic (As) and Uranium (U) due to unmonitored sources.

- Worsening Impact on Health Outcomes: Magnifies the physical vulnerability to heavy metal toxicity, particularly for vulnerable populations (children, elderly, pregnant women).

2. Food Insecurity

- Associated Challenge: The region has the highest rate of food insecurity in the U.S. and is classified as a food desert, with only 13 grocery stores for the entire area.

- Direct Influence: Long travel distances and the need for shelf-life result in the purchase and consumption of pre-packaged, energy-dense, processed foods.

- Influence on Contamination Exposure: Potential for nutritional deficiencies that may alter susceptibility to heavy metal poisoning.

- Worsening Impact on Health Outcomes: Worsens pre-existing chronic illnesses such as diabetes, obesity, and heart disease.

3. Limited Healthcare Access

- Associated Challenge: The region is a medically underserved area, with only 12 healthcare facilities for approximately 175,000 people across 27,000 square miles.

- Direct Influence: Delays diagnosis and treatment of contaminant-related illnesses.

- Influence on Contamination Exposure: Ongoing exposure to harmful factors hinders the long-term management of chronic illnesses.

- Worsening Impact on Health Outcomes: Magnifies the physical vulnerability to heavy metal toxicity, especially for vulnerable populations (children, elderly, pregnant women).

4. Poor Road Conditions

- Associated Challenge: Commutes to essential services are challenging, as two-thirds of the 14,000 roads are unpaved, and extreme weather events worsen road conditions.

- Direct Influence:

- ○

- Hinders access to regulated water sources, increasing the reliance on unregulated ones.

- ○

- Delays emergency medical care for acute exposures or complications from chronic exposure.

- Worsening Impact on Health Outcomes: Worsens food insecurity by limiting access to grocery stores.

5. Mitigating U and As Exposure and Challenges to Be Solved

Efforts to mitigate the contamination of As and U in drinking water involve a multifaceted approach: testing water sources for contamination, providing alternative water supplies, and ultimately water source treatment and remediation. A lack of comprehensive data on background concentrations of U and As in the NN makes it difficult to distinguish between natural levels and contamination from mining activities [6]. Despite limited data on the water quality of unregulated sources, studies have aimed to determine their safety for drinking water by collecting and compiling data [6,12,15,17,40]. Ongoing efforts to understand the spatial variability of groundwater contamination are important for resource management, assessing human health risks, and communicating risks to the local Navajo people. Notably, there is an uncertainty about the health effects of exposure to both As and U. This could be of concern especially since they are known to occur together in unregulated water sources in rural, former mining areas where health is already a problem. This situation highlights the need to better understand the toxicology of this chemical mixture and to develop intervention strategies that lower co-exposure.

Addressing environmental contamination on the Navajo Nation requires effective and adaptable U remediation technologies, and recent research highlights some promising advancements. Ighalo et al., 2024, offers a review on applicable remediation technologies [64]. The review includes several methods for removing U from water, including physical, chemical, and biological approaches such as membrane processes, adsorption, ion exchange, and biological reduction [64]. The removal rate of U from each method cited in the review demonstrated approximately ninety percent or greater [64]. Sadee et al., 2025, discusses conventional and developing technologies for As removal [52]. This includes adsorption, ion exchange, phytoremediation, chemical precipitation, electrocoagulation, and membrane technologies [52]. The removal rate of As from the majority of methods cited in the review exhibited approximately ninety percent or greater [52].

Similar to the Navajo Nation and many other tribal communities, the Walker River Paiute tribe also faces serious problems with As contamination [65]. Backer et al., 2025, demonstrated a successful intervention by implementing an iron coagulation microfiltration system. The tribe was able to dramatically reduce As concentrations in their drinking water to below USEPA’s maximum contaminant level for As. An important part of this study was the use of urinary As concentrations as a biological marker to confirm that the treatment was not only cleaning the water but also reducing human exposure to As. This research model was community led with collaborations involving the tribal government, the Indian Health Service, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [65].

In another pilot study testing the removal of As, Newcombe et al. used a reactive filtration [66,67]. The system combined hydrous ferric oxide adsorption and sand filtration, where ferric chloride (FeCl3) was added to the contaminated groundwater in an up flow moving bed sand filter. Clean water was then separated from a rejected waste stream in the filter [67]. The pilot scale system was tested for 49 h in a small community water system in Fruitland, ID. Arsenic concentration was significantly reduced by 92% from 0.0402 mg/L to 0.0033 mg/L, well below the drinking water MCL. Interestingly, the solid waste produced by the process was tested and found to be safe for landfill disposal [67]. This study demonstrates an effective method of removing As from water to meet drinking water MCL standards. The same chemistry may also be applied to U contaminated waters because of the demonstrated capacity of iron adsorption approaches to water treatment for U removal. These remediation technologies offer proven and effective frameworks that could be adapted and applied to address the ongoing water safety concerns in the NN.

Although the expansion of comprehensive central water infrastructure remains the ideal long-term objective, Point-of-Use (POU) filtration systems, such as those employing adsorptive media, provide a prompt, at-the-tap barrier against contaminants. A viable and cost-effective mitigation strategy to quickly address the need for lower arsenic and uranium exposure for NN residents who rely on unregulated water sources is the deployment of POU technologies [6,27]. This approach circumvents the prohibitively high cost and complex logistics associated with extending centralized piping to the Navajo Nation’s dispersed, remote communities [12]. The Strong Heart Water Study (SHWS) demonstrated a successful intervention model in comparable American Indian populations. In a randomized controlled trial, the SHWS installed POU arsenic filters and supported participants with a digital health program to ensure proper usage and filter changes. This action led to a substantial 47% average decrease in participants’ urinary arsenic levels over a two-year period, confirming the filters’ effectiveness for unregulated water source users [68]. Filter maintenance, regular replacement of cartridges, and consistent use are critical for achieving broad and sustained NN exposure reduction success. Any POU exposure intervention can be complicated by logistical and human factors, requiring the development of culturally appropriate, community-driven programs to address exposure [68]. The effort to clean contaminated drinking water supplies in the NN is a long-term, complex, and challenging, but important endeavor, which will require sustained commitment supported by federal funding and strong leadership of the Navajo Nation.

6. Working Towards Solutions in the NN

6.1. Key Stake Holders and Organizations

6.1.1. Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources (NNDWR)

Unequal access to clean drinking water is evident across the Navajo Nation, a problem exacerbated by the pollution of key water sources. Even so, the NN is committed to improving the standard of living in Navajo, and the development of sustainable water supplies is a high priority [14,69]. The NNDWR is the Nation’s water resources program and is organized into several key departments and branches, primarily focused on water management, protection, and resource planning. The mission and visions statements of the NNDWR articulate a dedication to responsible stewardship and management of the Nation’s vital water resources, ensuring their protection and beneficial use for both present and future generations while upholding Navajo sovereignty. This commitment drives efforts to sustain long-term socio-economic development, supports rural communities, and ultimately enhances the quality of life for all Navajo Nation members [70].

The severe lack of water infrastructure prompted the development of the 2011 draft Water Resources Development Strategy for the Navajo Nation that was created to help meet the needs of a growing population [14]. This strategy includes several components such as regional water projects, improving small public water systems, and drought mitigation response. For example, the Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project (NGWSP) is a significant regional water project that will serve more than forty Navajo chapters in New Mexico and Arizona, the City of Gallup, and the southern part of the Jicarilla Apache Nation. The project has two separate pipeline laterals, identified as San Juan and Cutter. The project is designed to provide a long-term sustainable water supply to meet the 40 year future population needs of approximately 250,000 people in these communities [71]. NGWSP will blend treated water from the San Juan River in northwest NM with local NTUA ground water wells [72]. As of 2024, the Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project (San Juan lateral) is 60% complete. The Cutter Lateral in Eastern Navajo Agency has been delivering water to more than 6000 people in eight chapters since 2020 [73]. Other long-term goals include several large regional water supply projects: Western Navajo pipeline, Ganado Regional Project, Southwest Navajo Regional Project, Utah Project, and the Farmington to Shiprock Pipeline.

6.1.2. Navajo Tribal Utility Authority (NTUA)

Established in 1959 by the Navajo Tribal Council [74], NTUA is a tribally owned enterprise of the NN and is the main and only utility provider on Navajo lands [75]. NTUA’s mission is to “provide safe, reliable, and affordable utility services that exceed their customers’ expectations.” The NTUA service area includes 38,000 electric customers, 35,000 water customers, and 13,000 wastewater customers. It is divided into seven districts and operates more than 100 public water systems with more than 220 wells, 270 tanks, 71 boosters, 90 lagoons, and 1300 miles of pipelines [14]. NNDWR has estimated that NTUA serves drinking water to more than 130,000 people every day [14].

6.1.3. Dig Deep—Navajo Water Project

A human rights nonprofit and umbrella organization, Dig Deep, funds and helps manage the Navajo Water Project (NWP). NWP is registered as an official enterprise in the Navajo Nation [76]. The NWP is a community managed utility alternative that brings hot and cold running water to homes without access to water or sewer lines. This is primarily completed by installing off grid home water systems. Large 1200-gallon water tanks are placed into the ground and buried. The house is plumbed, completed with a sink, water heater, septic system, filter and drain line. The project also provides power and lights to the home via solar panels [76] Multiple infrastructure gaps are simultaneously addressed through this system, benefiting rural households. A part of the project includes the development of new wells where water is pumped, treated, and stored. Water is delivered in food grade tanker trucks to hundreds of families located near the new water well. Water systems are also repaired and maintained through the project. Establishing reliable household water sources offers vital protection against the effects of climate change, especially for communities that have been historically underserved by public water systems [76].

6.1.4. Navajo Safe Water—Water Access Coordination Group (WAC-G)

Formed at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the group was created to help address the acute need for improved water access to Navajo homes lacking connection to public water systems [77]. It was a collaboration among tribal and federal agencies, public health researchers, and non-governmental organizations. WAC-G played a crucial role in sharing information, strategies, and ideas to assist in water access for the Navajo people [77]. The NN Water Access Mission was funded through Indian Health Service (IHS) CARES and ARPA Act funds. These funding opportunities helped Navajo homes that did not have access to piped water [77].

6.2. Federal Support to Improve Water Access in the NN

The proposed Tribal Access to Clean Water Act of 2025 aims to improve water security in tribal communities by expanding federal investment in water infrastructure [78]. Introduced on 14 July 2025, the bipartisan bill seeks to increase funding through the Indian Health Service (IHS), the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Rural Development, and the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) [78]. Over a five-year period, the legislation authorizes specific funding allocations to these agencies. These include USD 500 million for USDA’s Rural Development Community Facilities Grant Loan Program, with an additional USD 150 million designated for technical assistance. It also proposes USD 2.5 billion for IHS community facilities, USD 750 million for related technical assistance and operations and maintenance, and USD 90 million for the Bureau of Reclamation’s Native American Affairs Technical Assistance Program [78]. While this legislation represents a significant federal response to the critical lack of water infrastructure on tribal lands, it remains a proposal at the time of this publication [78].

6.3. Abandoned Mines Cleanup

The USEPA’s ten year federal action plan (2020–2029) to address the U contamination in the NN reported significant progress from 2023–2024, as detailed in the recent 2025 update [79]. Some notable achievements include the cleanup of The Cove Transfer Stations 1 & 2, which involved the excavation of approximately 20,000 cubic yards of mine waste. In addition, USEPA issued cleanup decisions for eight mine sites, with one mine site located in the Western AUM Region of Navajo lands and the remaining seven mine sites in the Eastern AUM Region. The cleanup decisions are noted to clean up over one million cubic yards of mine waste bringing the total waste volume addressed to an estimated 20% of waste in the NN. USEPA also added the Lukachukai Mountain Mining District to the National Priorities List in March of 2024. The site encompasses 88 mine sites, representing one million cubic yards of mine waste. Finally, the USEPA initiated consent decree negotiations with United Nuclear Corporation/General Electric to clean up the Northeast Church Rock (NECR) Mine site (Eastern Agency). This cleanup will involve removing approximately 1 million cubic yards from NECR mine sites and consolidating and capping the waste at the United Nuclear Corporation Superfund site in USEPA Region 6. As of August 2025, these negotiations have culminated in a formal agreement. A consent decree was lodged with the U.S. District Court for the District of New Mexico, requiring the United Nuclear Corporation (UNC) and General Electric (GE) to perform a nearly USD 63 million, decade-long cleanup [80,81]. Some actions also noted in the progress updates were completed by the Department of Energy. The Defense-Related Uranium Mine Program completed field investigations at Navajo AUMs in coordination with Navajo Abandoned Mine Lands for a total of 104 completed investigations in the Northern and North Central AUM Region [79].

7. Remaining Research Gaps

While substantial research has documented the extent of the harm of U and As contamination in drinking water sources, critical gaps remain. The exact extent of U and As transport through air and soil, particularly dust transport from tailing and waste piles, is not fully mapped or modeled across the entire NN [82]. There remains an ongoing challenge in definitively determining the proportion of contamination that is human caused versus natural, which has impacted remediation strategy and liability [83]. Additionally, there remains a gap in our understanding of bioaccumulation of U and As in the food chain (e.g., agriculture) on the NN [84]. It is understood that contaminants such as As and U can accumulate in livestock meat and milk as well as in crops irrigated with contaminated water and that this pathway directly affects Navajo residents who rely on subsistence practices [84]. However, there have been no extensive studies on the impact of dietary exposure from these sources [85]. Research is also needed to assess the effectiveness of risk communication strategies and environmental health education programs tailored to Navajo language and culture, especially for residents who rely on unregulated water sources [86]. Despite multi-agency efforts and settlements, governmental response has been characterized by delayed action, piecemeal funding, and a failure to fully uphold the Federal Trust Responsibility by not adequately funding essential water infrastructure [87,88].

8. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

This review of the environmental and human health impacts of U and As contamination in drinking water sources on the Navajo Nation reveals a concerning pattern of exposure and threat to the health and wellbeing of the Navajo people. The persistent exposure to these contaminants requires sustained research and the continued development of targeted interventions. The contamination of Navajo lands is not just a scientific problem, but a systemic issue rooted in historical injustice and socioeconomic disparities, that continues across many Indigenous communities. Despite these significant challenges, the resilience and advocacy of the Navajo people in advancing access to clean water are evident. Moving forward, collaborative efforts must prioritize empowering the community in monitoring, remediation, and ensuring access to safe and reliable drinking water for generations to come.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T. and G.M.; methodology, M.T. and G.M.; formal analysis, M.T. and G.M.; investigation, M.T. and G.M.; resources, G.M.; data curation, M.T. and G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.; writing—review and editing, M.T. and G.M.; visualization, M.T.; supervision, G.M.; project administration, G.M.; funding acquisition, G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Pacific Northwest Alliance to Develop, Implement and Study a STEM Graduate Education Model for American Indians and Native Alaskans, award number 1432910. This work is also supported by the Idaho Agricultural Experiment Station, USDA NIFA Project Number IDA0171. The APC was funded by MDPI.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Scheidel, A.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Bara, A.H.; Del Bene, D.; David-Chavez, D.M.; Fanari, E.; Garba, I.; Hanaček, K.; Liu, J.; Martínez-Alier, J.; et al. Global impacts of extractive and industrial development projects on Indigenous Peoples’ lifeways, lands, and rights. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade9557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimordiaz, A.; Suswanta, S. Environmental Conflict and Human Rights: Indigenous Peoples’ Struggle Against Land Exploitation in Papua. J. Ilmu. Sos. Dan. Hum. 2025, 14, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Garteizgogeascoa, M.; Basu, N.; Brondizio, E.S.; Cabeza, M.; Martínez-Alier, J.; McElwee, P.; Reyes-García, V. A State-of-the-Art Review of Indigenous Peoples and Environmental Pollution. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2020, 16, 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uncommon Ground: The Impact of Natural Resource Corruption on Indigenous Peoples|Brookings. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/uncommon-ground-the-impact-of-natural-resource-corruption-on-indigenous-peoples/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Redvers, N.; Chischilly, A.M.; Warne, D.; Pino, M.; Lyon-Colbert, A. Uranium Exposure in American Indian Communities: Health, Policy, and the Way Forward. Environ. Health Perspect. 2021, 129, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, J.; Gonzales, M.; Shuey, C.; Barney, Y.; Lewis, J. Elevated Arsenic and Uranium Concentrations in Unregulated Water Sources on the Navajo Nation, USA. Expo. Health 2017, 9, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Sanitation Facilities Construction Program of the Indian Health Service. Annual Report for 2012. The Sanitation Facilities Construction Program of the Indian Health Service. 2012. Available online: https://www.ihs.gov/sites/dsfc/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/reports/SFCAnnualReport2012.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Navajo Nation|History. Available online: https://www.navajo-nsn.gov/History (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Navajo Epidemiology Center. Navajo NationPopulation Profile U.S. Census 2020; Navajo Department of Health: Window Rock, AZ, USA, 2024. Available online: https://nec.navajo-nsn.gov/Portals/0/Reports/Navajo%20Nation%20Population%20Profile%202020.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- George, C.; Bancroft, C.; Salt, S.K.; Curley, C.S.; Curley, C.; de Heer, H.D.; Yazzie, D.; Antone-Nez, R.; Shin, S.S. Changes in food pricing and availability on the Navajo Nation following a 2% tax on unhealthy foods: The Healthy Diné Nation Act of 2014. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources. Navajo Nation Drought Contingency Plan 2003; Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources: Window Rock, AZ, USA, 2003; Available online: http://www.frontiernet.net/~nndwr_wmb/PDF/Reports/DWRReports/DWR2003%20Navajo%20Nation%20Drought%20Contingency%20Plan.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Jones, L.; Credo, J.; Parnell, R.; Ingram, J.C. Dissolved Uranium and Arsenic in Unregulated Groundwater Sources—Western Navajo Nation. J. Contemp. Water Res. Educ. 2020, 169, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Chapter 5: Assessment of Current Tribal Water Use and Projected Future Water Development, Section 5.5, Navajo Nation. In Colorado River Basin Ten Tribes PartnershipTribal Water Study; U.S. Bureau of Reclamation: Denver, CO, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/programs/crbstudy/tws/docs/Ch.%205.5%20Navajo%20Current-Future%20Water%20Use%2012-13-2018.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources. DraftWater Resource Development Strategy for the Navajo Nation; Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources: Window Rock, AZ, USA, 2011. Available online: https://www.ose.nm.gov/Legal/settlement/NNWRS/Navajo%20Nation%20Discovery%20Responses/Water%20Use/WU-21%202011-07%20Draft%20NN%20DWR%20Water%20Resource%20Dev%20Strategy.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Credo, J.; Torkelson, J.; Rock, T.; Ingram, J.C. Quantification of Elemental Contaminants in Unregulated Water across Western Navajo Nation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns Hopkins Center for Indigenous Health. Wateris Life: Using Data to Empower Diné Communities to Close the Water Access Gap: Research Brief; Johns Hopkins Center for Indigenous Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2024; Water is Life—Using Data to Empower Dine; Available online: https://cih.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Dine-HH-Water-Survey-Research-Brief_-1.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Blake, J.M.; Avasarala, S.; Artyushkova, K.; Ali, A.-M.S.; Brearley, A.J.; Shuey, C.; Robinson, W.P.; Nez, C.; Bill, S.; Lewis, J. Elevated Concentrations of U and Co-occurring Metals in Abandoned Mine Wastes in a Northeastern Arizona Native American Community. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 8506–8514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Arsenic; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service: Washington, DC, USA; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2007. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp2.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Nickson, R.; McArthur, J.; Burgess, W.; Ahmed, K.M.; Ravenscroft, P.; Rahmanñ, M. Arsenic poisoning of Bangladesh groundwater. Nature 1998, 395, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smedley, P.L.; Kinniburgh, D.G. A review of the source, behaviour and distribution of arsenic in natural waters. Appl Geochem. 2002, 17, 517–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and DiseaseRegistry. Toxicological Profile for Uranium; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service: Washington, DC, USA; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp150.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Zupunski, L.; Street, R.; Ostroumova, E.; Winde, F.; Sachs, S.; Geipel, G.; Nkosi, V.; Bouaoun, L.; Haman, T.; Schüz, J.; et al. Environmental exposure to uranium in a population living in close proximity to gold mine tailings in South Africa. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2023, 77, 127141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnamarad, J.; Derakhshani, R.; Abbasnejad, A. Data on arsenic contamination in groundwater of Rafsanjan plain, Iran. Data Brief 2020, 31, 105772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift Bird, K.; Navarre-Sitchler, A.; Singha, K. Hydrogeological controls of arsenic and uranium dissolution into groundwater of the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota. Appl. Geochem. 2020, 114, 104522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.; Hoover, J.; MacKenzie, D. Mining and Environmental Health Disparities in Native American Communities. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugge, D.; Goble, R. The History of Uranium Mining and the Navajo People. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.C.; Jones, L.; Credo, J.; Rock, T. Uranium and arsenic unregulated water issues on Navajo lands. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2020, 38, 031003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abandoned Mines Cleanup|US EPA. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/navajo-nation-uranium-cleanup/aum-cleanup#sites (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Akcil, A.; Koldas, S. Acid Mine Drainage (AMD): Causes, treatment and case studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fettus, G.H.; McKinzie, M.G. Nuclear Fuel’s DirtyBeginnings; Natural Resources Defense Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/uranium-mining-report.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- De Lemos, J.L.; Bostick, B.C.; Quicksall, A.N.; Landis, J.D.; George, C.C.; Slagowski, N.L.; Rock, T.; Brugge, D.; Lewis, J.; Durant, J.L. Rapid Dissolution of Soluble Uranyl Phases in Arid, Mine-Impacted Catchments near Church Rock, NM. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 3951–3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How the US Poisoned Navajo Nation. 2020. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ETPogv1zq08 (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- IRIS Toxicological Review of Inorganic Arsenic (Public Comment and External Review Draft)|IRIS|US EPA. Available online: https://iris.epa.gov/document/&deid%3D253756 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Hoover, J.H.; Coker, E.; Barney, Y.; Shuey, C.; Lewis, J. Spatial clustering of metal and metalloid mixtures in unregulated water sources on the Navajo Nation—Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 1667–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radionuclides Rule|US EPA. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/dwreginfo/radionuclides-rule (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- US EPA Drinking Water Arsenic Rule History. 13 October 2015. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/dwreginfo/drinking-water-arsenic-rule-history (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality; Fourth Edition Incorporating the First and Second Addenda; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency. Navajo Nation Primary Drinking Water Regulations; Nation Environmental Protection Agency: Window Rock, AZ, USA, 2024; Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/61f18d0ee0605f4e06b817ca/t/6758673e78c2a22d0a6f7afd/1733846850264/NN+Primary+Drinking+Water+Regulations+%28NNPDWRs%29.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency. Navajo Nation Surface Water Quality Standards 2015; Nation Environmental Protection Agency: Window Rock, AZ, USA, 2015; Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/61f18d0ee0605f4e06b817ca/t/63b5bf293fdf95545c63ca36/1672855339036/NN+CWA+Surface+Water+Quality+Standards.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Corlin, L.; Rock, T.; Cordova, J.; Woodin, M.; Durant, J.L.; Gute, D.M.; Ingram, J.; Brugge, D. Health Effects and Environmental Justice Concerns of Exposure to Uranium in Drinking Water. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2016, 3, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazzie, S.A.; Davis, S.; Seixas, N.; Yost, M.G. Assessing the Impact of Housing Features and Environmental Factors on Home Indoor Radon Concentration Levels on the Navajo Nation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What is EPA’s Action Level for Radon and What Does it Mean?|US EPA. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/radon/what-epas-action-level-radon-and-what-does-it-mean (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- A Citizen’s Guide to Radon: The Guide to Protecting Yourself and Your Family from Radon; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA.

- Thompson, K.M.; Burmaster, D.E. Parametric Distributions for Soil Ingestion by Children. Risk Anal. 1991, 11, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and DiseaseRegistry. Toxicological Profile for Lead; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service: Washington, DC, USA; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp13.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Hoover, J.H.; Erdei, E.; Begay, D.; Gonzales, M.; NBCS Study Team; Jarrett, J.M.; Cheng, P.Y.; Lewis, J. Exposure to uranium and co-occurring metals among pregnant Navajo women. Environ. Res. 2020, 190, 109943. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Yadav, R.; Sharma, S.; Singh, A.N. Arsenic contamination in the food chain: A threat to food security and human health. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson González, N.; Ong, J.; Luo, L.; MacKenzie, D. Chronic Community Exposure to Environmental Metal Mixtures Is Associated with Selected Cytokines in the Navajo Birth Cohort Study (NBCS). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.M.; Noble, B.N.; Joya, S.A.; Hasan, M.O.S.I.; Lin, P.-I.; Rahman, M.L.; Mostofa, G.; Quamruzzaman, Q.; Rahman, M.; Christiani, D.C.; et al. A Prospective Cohort Study Examining the Associations of Maternal Arsenic Exposure with Fetal Loss and Neonatal Mortality. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, M.E.; Lewis, J.; Miller, C.; Hoover, J.; Ali, A.-M.S.; Shuey, C.; Cajero, M.; Lucas, S.; Zychowski, K.; Pacheco, B.; et al. Residential proximity to abandoned uranium mines and serum inflammatory potential in chronically exposed Navajo communities. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, K.P.; Gold, A.O.; Spratlen, M.J.; Umans, J.G.; Fretts, A.M.; Goessler, W.; Zhang, Y.; Navas-Acien, A.; Nigra, A.E. Uranium Exposure, Hypertension, and Blood Pressure in the Strong Heart Family Study. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2025, 22, 240122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadee, B.A.; Zebari, S.M.S.; Galali, Y.; Saleem, M.F. A review on arsenic contamination in drinking water: Sources, health impacts, and remediation approaches. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 2684–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Park, S. Iron deficiency increases blood concentrations of neurotoxic metals in children. Korean J. Pediatr. 2014, 57, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Heavy metals: Toxicity and human health effects. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 153–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartrem, C.; Tirima, S.; Von Lindern, I.; von Lindern, I.; von Braun, M.C.; Worrell, M.C.; Anka, S.M.; Abdullahi, A. Unknown risk: Co-exposure to lead and other heavy metals among children living in small-scale mining communities in Zamfara State, Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2014, 24, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, D.; Słowik, J.; Chilicka, K. Heavy Metals and Human Health: Possible Exposure Pathways and the Competition for Protein Binding Sites. Molecules 2021, 26, 6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennion, N.; Redelfs, A.H.; Spruance, L.; Benally, S.; Sloan-Aagard, C. Driving Distance and Food Accessibility: A Geospatial Analysis of the Food Environment in the Navajo Nation and Border Towns. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 904119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutko, P.; Ploeg, M.V.; Farrigan, T. Characteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts. In Economic Research Report; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Etsitty, S.O.; John, B.; Greenfeld, A.; Alsburg, R.; Egge, M.; Sandman, S.; George, C.; Curley, C.; Curley, C.; de Heer, H.D.; et al. Implementation of Indigenous Food Tax Policies in Stores on Navajo Nation. Health Promot Pract. 2022, 23 (Suppl. 1), 76S–85S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diné Policy Institute. Diné Food Sovereignty:A Report on the Navajo Nation Food System and the Case to Rebuild a Self-Sufficient Food System for the Diné People. Diné Policy Institute, Diné College: Tsaile, AZ, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.dinecollege.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/dpi-food-sovereignty-report.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Healthcare Facilities|Navajo Area. Available online: https://www.ihs.gov/navajo/healthcarefacilities/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Arizona Department of Health Services. Arizona Medically Underserved Areas: Biennial Report; ArizonaDepartment of Health Services: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.azdhs.gov/documents/prevention/health-systems-development/data-reports-maps/reports/azmua-biennial-report.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Chowdhury, S.; Dey, A.; Alzarrad, A. Charting pathways to holistic development: Challenges and opportunities in the Navajo Nation. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2024, 44, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, J.O.; Chen, Z.; Ohoro, C.R.; Oniye, M.; Igwegbe, C.A.; Elimhingbovo, I.; Khongthaw, B.; Dulta, K.; Yap, P.-S.; Anastopoulos, I. A review of remediation technologies for uranium-contaminated water. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backer, L.; Stearns, D.; Daniel, J.; Tomazin, R.; Harvey, D.; Williams, T.; Peterson-Wright, L.; Strosnider, H.; Freedman, M.; Yip, F. Changes in Exposure to Arsenic Following the Installation of an Arsenic Removal Treatment in a Small Community Water System. Water 2025, 17, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Baker, M.C.; Taslakyan, L.; Strawn, D.G.; Möller, G. Reactive Filtration Water Treatment: A Retrospective Review of Sustainable Sand Filtration Re-Engineered for Advanced Nutrient Removal and Recovery, Micropollutant Destructive Removal, and Net-Negative CO2e Emissions with Biochar. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, R.L.; Hart, B.K.; Möller, G. Arsenic Removal from Water by Moving Bed Active Filtration. J. Environ. Eng. 2006, 132, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, C.M.; Zacher, T.; Endres, K.; Richards, F.; Robe, L.B.; Harvey, D.; Best, L.G.; Cloud, R.R.; Bear, A.B.; Skinner, L.; et al. Effect of an Arsenic Mitigation Program on Arsenic Exposure in American Indian Communities: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of the Community-Led Strong Heart Water Study Program. Environ. Health Perspect. 2024, 132, 037007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeper, J.W. Navajo Nation plans for their waterfuture. In New Mexico Water Planning 2003, Proceedings of the 48th Annual New Mexico Water Conference, Las Cruces, New Mexico, 13–14 November 2003; New Mexico Water Resources Research Institute: Las Cruces, NM, USA, 2003; Available online: https://nmwrri.nmsu.edu/publications/water-conference-proceedings/wcp-documents/w48/leeper.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources|Home. Available online: https://nndwr.navajo-nsn.gov/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project|Upper Colorado Region|Bureau of Reclamation. Available online: https://www.usbr.gov/uc/progact/navajo-gallup/index.html (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Division of Sanitation Facilities Construction -Indian Health Service. Annual Report 2017; Division of Sanitation Facilities Construction—Indian Health Service: Rockville, MA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.ihs.gov/sites/dsfc/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/reports/SFCAnnualReport2017.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project’s San Juan Lateral is 60% Complete—Navajo Nation Office of the President. Available online: https://opvp.navajo-nsn.gov/navajo-gallup-water-supply-projects-san-juan-lateral-is-60-complete/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Navajo Tribal Utility Authority|Home. Available online: https://www.ntua.com/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Navajo Tribal Utility Authority. 2024Progress Report; Navajo Tribal Utility Authority: Navajo Nation, AZ, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.navajonationcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/2024_NTUA_PROGRESS_REPORT_final_web.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- McNeeley, S.; Shimabuku, M.; Anderson, R.; Will, R.; Dery, J. Achieving Equitable, Climate-Resilient Water and Sanitation forFrontline Communities: Water, Sanitation, and Climate Change in the United States, Part 3; Pacific Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://pacinst.org/publication/achieving-equitable-water-and-sanitation/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Improving Water Access|Navajo Safe Water. Available online: https://navajo-safe-water-2-navajosafewater.hub.arcgis.com/pages/f99e7f8fec5d4358a6866262c229eb31 (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- H.R.4377—119th Congress (2025–2026): Tribal Access to Clean Water Act of 2025|Congress.gov|Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/4377/text/ih?overview=closed&format=xml (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 9. Progress Update: Federal Actions to Address Uranium Contamination on Navajo Nation2020–2029; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2025-07/ten-year-plan-nnaum-progress-update-2023-2025.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- United Nuclear Corporation and General Electric to Perform $63 Million Cleanup of Uranium Mine Waste at Northeast Church Rock Mine in Navajo Nation|US EPA. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/united-nuclear-corporation-and-general-electric-perform-63-million-cleanup-uranium (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- UNC, GE Agree to Clean Up Former N.M. Uranium Mine—ANS/Nuclear Newswire. Available online: https://www.ans.org/news/2025-08-13/article-7274/unc-ge-agree-to-clean-up-former-new-mexico-uranium-mine/ (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Lin, Y.; Hoover, J.; Beene, D.; Erdei, E.; Liu, Z. Environmental risk mapping of potential abandoned uranium mine contamination on the Navajo Nation, USA, using a GIS-based multi-criteria decision analysis approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 30542–30557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]