The Relationship between Parenting Behaviors and Adolescent Well-Being Varies with the Consistency of Parent–Adolescent Cultural Orientation

Abstract

1. Introduction

This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Parental Cultural Orientation Questionnaire

2.2.2. Adolescents’ Cultural Orientation Questionnaire

2.2.3. Adolescents’ Perception of Parenting Behaviors Questionnaire

2.2.4. Basic Psychological Needs Questionnaire

2.2.5. Adolescents’ Well-Being Questionnaire

2.3. Procedure

- (1)

- Both the student and parent versions of the questionnaire should include the student’s school ID or the last four digits of their National Identification Number to ensure that each student’s and parent’s responses can be matched accurately.

- (2)

- The student version of the questionnaire must be completed by the student themselves and not by someone else. The parental version should be completed by a parent. If the parent is away for work, another guardian at home may answer it, but under no circumstances should the student fill it out on behalf of the parent.

- (3)

- There are no right or wrong answers to any of the questions; participants should answer according to their actual situations.

- (4)

- All provided information will be kept strictly confidential.

2.4. Data Analyses

- (1)

- Delete the questionnaires whose informed consent right is ‘No’;

- (2)

- Delete the questionnaires with missing or wrong answers;

- (3)

- Remove the questionnaires with a total score of 4 points or more of lie detection questions in the Parental Cultural Orientation Questionnaire;

- (4)

- Questionnaires with a total lie detection score of 4 or above were deleted from the questionnaires related to adolescents’ cultural orientation, perceived parenting behavior, basic psychological needs satisfaction, and well-being;

- (5)

- Either the student ID number or student number and the class filled in the Parental Cultural Orientation Questionnaire and the Adolescent Cultural Orientation Questionnaire can have a one-to-one correspondence. If not, parents and the youth version of the cultural orientation questionnaire will be deleted.

3. Results

3.1. Test for Common Method Bias

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

- (1)

- Parental cultural orientation (individualism–collectivism) is positively correlated with adolescents’ cultural orientation (individualism–collectivism).

- (2)

- Parental cultural orientation (individualism–collectivism) is positively correlated with adolescent-perceived parental autonomy support, adolescent basic psychological needs, and adolescent well-being. It is negatively correlated with adolescent-perceived parental control and the frustration of adolescents’ basic psychological needs.

- (3)

- Adolescents’ cultural orientation (individualism–collectivism) is positively correlated with adolescent basic psychological needs satisfaction and adolescents’ well-being but negatively correlated with the frustration of adolescent basic psychological needs.

- (4)

- Adolescent-perceived parental autonomy support is positively correlated with adolescent basic psychological needs satisfaction and adolescents’ well-being but negatively correlated with adolescent-perceived parental control and the frustration of adolescent basic psychological needs.

- (5)

- Adolescent-perceived parental control is positively correlated with the frustration of adolescent basic psychological needs but negatively correlated with adolescent basic psychological needs satisfaction and adolescents’ well-being.

- (6)

- Adolescent basic psychological needs satisfaction is positively correlated with adolescents’ well-being but negatively correlated with the frustration of basic psychological needs.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PCO(I-C) | 0.18 | 0.24 | |||||||

| 2. ACO(I-C) | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.242 ** | ||||||

| 3. APAS | 3.84 | 0.87 | 0.215 ** | 0.070 | |||||

| 4. APPC | 2.70 | 0.86 | −0.233 ** | −0.127 ** | −0.636 ** | ||||

| 5. ABPNS | 3.69 | 0.68 | 0.108 ** | 0.202 ** | 0.472 ** | −0.350 ** | |||

| 6. ABPNF | 2.83 | 0.82 | −0.212 ** | −0.175 ** | −0.391 ** | 0.574 ** | −0.435 ** | ||

| 7. AWB | 3.51 | 0.74 | 0.109 ** | 0.142 ** | 0.509 ** | −0.419 ** | 0.646 ** | −0.586 ** |

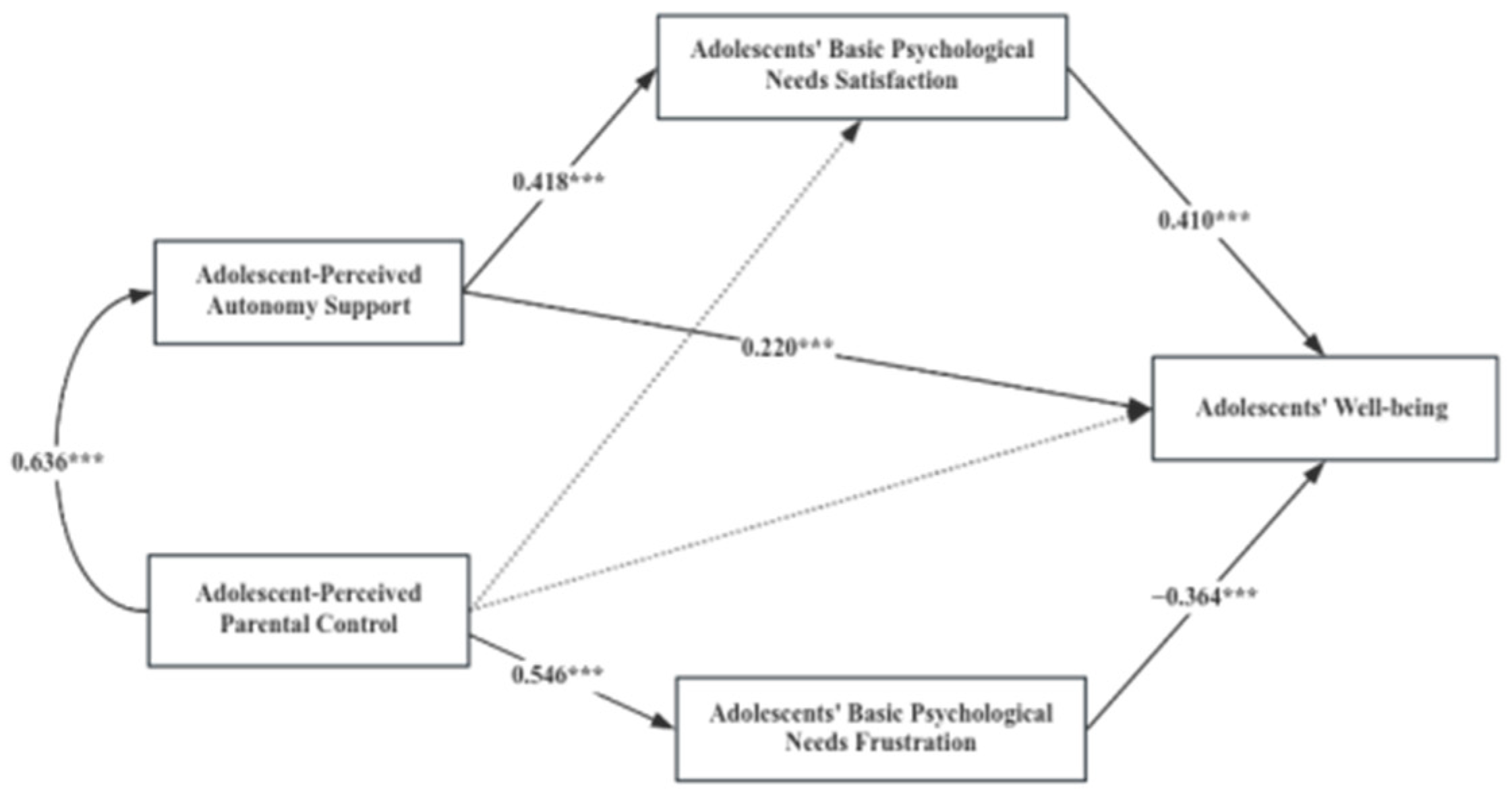

3.3. The Impact of Parenting Behavior on Adolescents’ Basic Psychological Needs and Well-Being

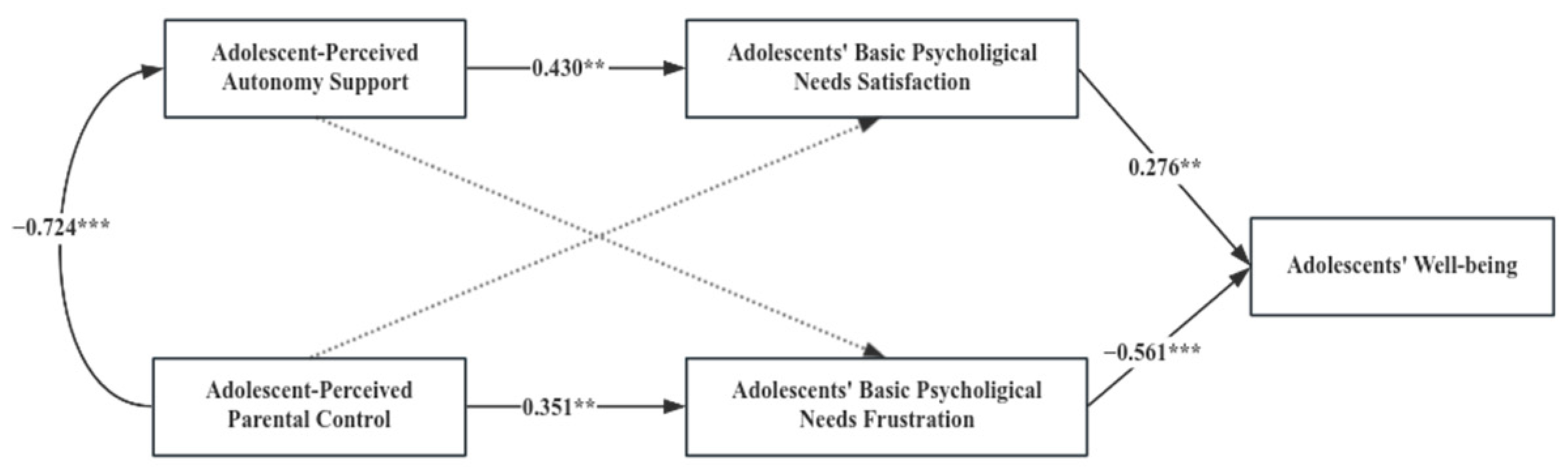

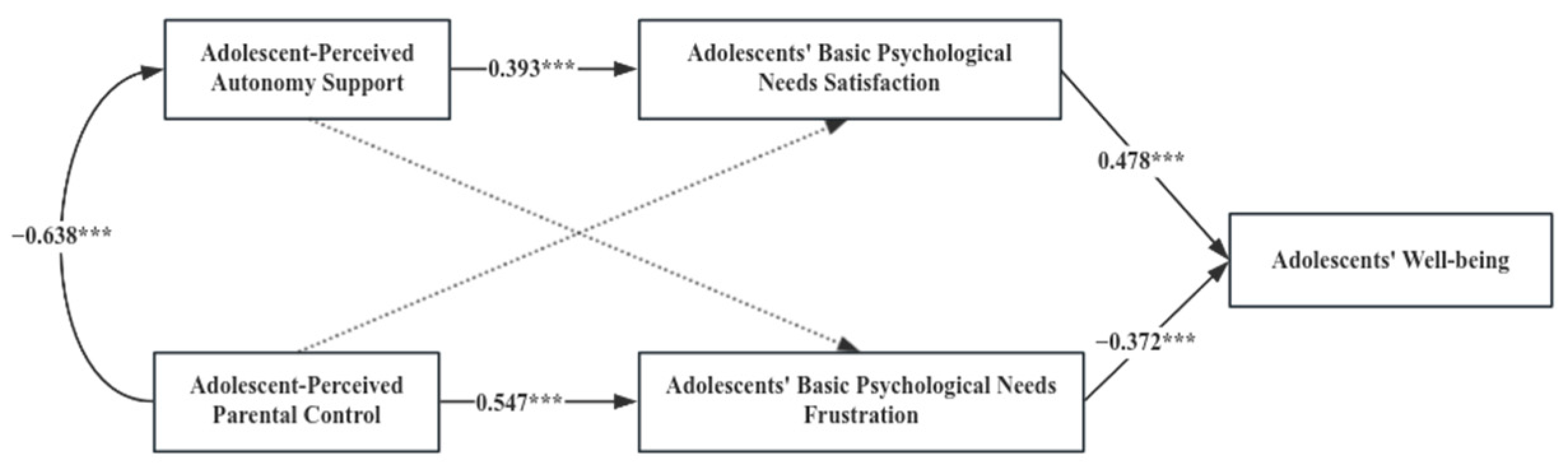

3.4. The Moderating Role of the Consistency of Parent–Adolescent Cultural Orientation in the Relationship between Parenting Behaviors and Adolescent Well-Being

4. Discussion

4.1. Reaffirmation of the Role of Basic Psychological Needs in the Relationship between Parenting Behavior and Adolescent Well-Being

4.2. Providing Initial Evidence for the Moderating Role of Parent–Child Cultural Orientation Alignment in the Outcomes of Parental Control Behaviors

4.3. Implications for Family Education Intervention Programs

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Abad, N.; Omoile, J. Testing Self-Determination Theory via Nigerian and Indian adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.R.; Richard, M. Facilitating Optimal Motivation and Psychological Well-Being Across Life’s Domains. Can. Psychol.-Psychol. Can. 2008, 49, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, A.T.; Katigbak, M.S.; Locke, K.D.; Zhang, H.; Shen, J.; de Jesus Vargas-Flores, J.; Ibanez-Reyes, J.; Tanaka-Matsumi, J.; Curtis, G.J.; Cabrera, H.F.; et al. Need Satisfaction and Well-Being: Testing Self-Determination Theory in Eight Cultures. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2013, 44, 507–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, L.; Diener, E. Needs and Subjective Well-Being Around the World. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Van Assche, J.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Soenens, B.; Beyers, W. Does Psychological Need Satisfaction Matter When Environmental or Financial Safety are at Risk? J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 745–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeHaan, C.R.; Hirai, T.; Ryan, R.M. Nussbaum’s Capabilities and Self-Determination Theory’s Basic Psychological Needs: Relating Some Fundamentals of Human Wellness. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M. Associations of Parenting Dimensions and Styles With Externalizing Problems of Children and Adolescents: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 873–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Bernstein, J.H.; Brown, K.W. Weekends, work, and well-being: Psychological need satisfactions and day of the week effects on mood, vitality, and physical symptoms. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 29, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Soenens, B. The Relations of Arab Jordanian Adolescents’ Perceived Maternal Parenting to Teacher-Rated Adjustment and Problems: The Intervening Role of Perceived Need Satisfaction. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Sireno, S.; Larcan, R.; Cuzzocrea, F. The six dimensions of parenting and adolescent psychological adjustment: The mediating role of psychological needs. Scand. J. Psychol. 2019, 60, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabbe, E.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Van Leeuwen, K. Do Personality Traits Moderate Relations Between Psychologically Controlling Parenting and Problem Behavior in Adolescents? J. Personal. 2016, 84, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholomew, K.J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Ryan, R.M.; Bosch, J.A.; Thogersen-Ntoumani, C. Self-Determination Theory and Diminished Functioning: The Role of Interpersonal Control and Psychological Need Thwarting. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 1459–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stebbings, J.; Taylor, I.M.; Spray, C.M.; Ntoumanis, N. Antecedents of Perceived Coach Interpersonal Behaviors: The Coaching Environment and Coach Psychological Well- and III-Being. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 34, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Chen, H.; Huebner, E.S. The Longitudinal Relationships Between Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction at School and School-Related Subjective Well-Being in Adolescents. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 119, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Beyers, W.; Boone, L.; Deci, E.L.; Van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Duriez, B.; Lens, W.; Matos, L.; Mouratidis, A.; et al. Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.K.; Stolz, H.E.; Olsen, J.A. Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2005, 70, 1–137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cordeiro, P.; Paixao, P.; Lens, W.; Lacante, M.; Luyckx, K. The Portuguese Validation of the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale: Concurrent and Longitudinal Relations to Well-being and Ill-being. Psychol. Belg. 2016, 56, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.; Lamm, B.; Abels, M.; Yovsi, R.; Borke, J.; Jensen, H.; Papaligoura, Z.; Holub, C.; Lo, W.S.; Tomiyama, A.J.; et al. Cultural models, socialization goals, and parenting ethnotheories-A multicultural analysis. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2006, 37, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Li, X. A cross-cultural examination of family communication patterns, parent-child closeness, and conflict styles in the United States, China, and Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Commun. 2017, 17, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R.K. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, R.; Liu, X. The relationships among parental psychological control/autonomy support, self-trouble, and internalizing problems across adolescent genders. Scand. J. Psychol. 2019, 60, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudy, D.; Grusec, J.E. Authoritarian parenting in individualist and collectivist groups: Associations with maternal emotion and cognition and children’s self-esteem. J. Fam. Psychol. 2006, 20, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Bouck, L.; Patterson, M.M.; Chen, J. Relations of Collectivism Socialization Goals and Training Beliefs to Chinese Parenting. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2019, 50, 396–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.B.; Ganotice, F.A., Jr. Does family obligation matter for students’ motivation, engagement, and well-being? It depends on your self-construal. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 86, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbell-Pierre, K.N.; Grolnick, W.S.; Stewart, A.L.; Raftery-Helmer, J.N. Parental Autonomy Support in Two Cultures: The Moderating Effects of Adolescents’ Self-Construals. Child Dev. 2019, 90, 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Wang, X. Value differences between generations in China: A study in Shanghai. J. Youth Stud. 2010, 13, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Xu, J. Intergenerational Changes in Individualism in China 1980–2010: The Role of Modernization; Chinese Psychological Society: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, X.; Ma, X.; Xu, J. Intergenerational Changes in Collectivism/Individualism in China: Evidence from Names; Chinese Psychological Society: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, P.; Xin, Y.; Gao, J.; Feng, C. Changes in the Values of Chinese Adolescents (1987–2015). Youth Stud. 2017, 4, 1–10+94. [Google Scholar]

- Helwig, C.C.; To, S.; Wang, Q.; Liu, C.; Yang, S. Judgments and Reasoning About Parental Discipline Involving Induction and Psychological Control in China and Canada. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 1150–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Jing, Y.; Yu, F.; Gu, R.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Cai, H. Individualism rises, collectivism declines? Global cultural changes and people ‘s psychological changes. Psychol. Sci. Prog. 2018, 26, 2068–2080. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, A.S.; Fung, J. On Better Footing to Understand Parenting and Family Process in Asian American Families. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2013, 4, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S.; Kim, B.S.K.; Chiang, J.; Ju, C.M. Acculturation, Enculturation, Parental Adherence to Asian Cultural Values, Parenting Styles, and Family Conflict Among Asian American College Students. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2010, 1, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; Coon, H.M.; Kemmelmeier, M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C.; Brislin, R.; Hui, C.H. Cross-cultural training across the individualism-collectivism divide. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1988, 12, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardif-Williams, C.Y.; Fisher, L. Clarifying the link between acculturation experiences and parent-child relationships among families in cultural transition: The promise of contemporary critiques of acculturation psychology. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2009, 33, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Yang, P.H.; Atkinson, D.R.; Wolfe, M.M.; Hong, S. Cultural value similarities and differences among Asian American ethnic groups. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2001, 7, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.K.; Li, L.C.; Ng, G.F. The Asian American values scale--multidimensional: Development, reliability, and validity. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2005, 11, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Chen, H. The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the united states and china. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 1592–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageau, G.A.; Ranger, F.; Joussemet, M.; Koestner, R.; Moreau, E.; Forest, J. Validation of the Perceived Parental Autonomy Support Scale (P-PASS). Can. J. Behav. Sci.-Rev. Can. Des Sci. Du Comport. 2015, 47, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.C.; Mandleco, B.; Olsen, S.F.; Hart, C.H. Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychol. Rep. 1995, 77, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L. A Longitudinal Study of Perceived Family Functioning and Adolescent Adjustment in Chinese Adolescents with Economic Disadvantage. J. Fam. Issues 2005, 26, 518–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L. Economic disadvantage, perceived family life quality, and emotional well-being in Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal study. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 85, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, E.S. Children’s reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Dev. 1965, 36, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, B.K. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 3296–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrin, C.; Woszidlo, A.; Givertz, M.; Bauer, A.; Murphy, M.T. The Association Between Overparenting, Parent-Child Communication, and Entitlement and Adaptive Traits in Adult Children. Fam. Relat. 2012, 61, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of a short-form of the EMBU among Chinese adolescents. Psychol. Rep. 2012, 110, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, S.; Scharf, M. “I will guide you” The indirect link between overparenting and young adults’ adjustment. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 228, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.T.Y.; Shek, D.T.L. Validation of the Perceived Chinese Overparenting Scale in Emerging Adults in Hong Kong. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. From Happiness to Hope: A Study on the Structure, Developmental Characteristics, and Related Factors of Adolescent Well-Being; Jilin University Press: Changchun, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Gai, X.; Zhange, Y.; Wang, G. The Impact of Adolescent Well-being on Academic Development: The Mediating Effect of School Engagement. Psychol. Explor. 2018, 38, 260–266. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. The Status, Role, and Influencing Factors of Well-Being among Junior High School Students. Ph.D. Thesis, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Long, L. Statistical Tests and Control Methods for Common Method Bias. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 6, 942–950. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, S.; Cuzzocrea, F.; Gugliandolo, M.C.; Larcan, R. Associations Between Parental Psychological Control and Autonomy Support, and Psychological Outcomes in Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Need Satisfaction and Need Frustration. Child Indic. Res. 2016, 9, 1059–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Soenens, B.; Loeys, T.; Mabbe, E.; Gargurevich, R. Autonomy-Supportive Parenting and Autonomy-Supportive Sibling Interactions: The Role of Mothers’ and Siblings’ Psychological Need Satisfaction. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 41, 1590–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.; Soenens, B.; Gugliandolo, M.C.; Cuzzocrea, F.; Larcan, R. The Mediating Role of Experiences of Need Satisfaction in Associations Between Parental Psychological Control and Internalizing Problems: A Study among Italian College Students. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Grolnick, W. Origins and pawns in the classroom: Self-report and projective assessments of individual differences in children’s perceptions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froiland, J.M. Parental Autonomy Support and Student Learning Goals: A Preliminary Examination of an Intrinsic Motivation Intervention. Child Youth Care Forum 2011, 40, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbell, K.N.; Grolnick, W.S. Correlates of parental control and autonomy support in an interdependent culture: A look at Ghana. Motiv. Emot. 2013, 37, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M. A theoretical upgrade of the concept of parental psychological control: Proposing new insights on the basis of self-determination theory. Dev. Rev. 2010, 30, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Soenens, B.; Vandereycken, W. Motivation to change in eating disorder patients: A conceptual clarification on the basis of self-determination theory. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005, 37, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-C.L.; Chan, H.-Y.; Chen, P.-C. Transitions of Developmental Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms Between Junior and Senior High School Among Youths in Taiwan: Linkages to Symptoms in Young Adulthood. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2018, 46, 1687–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.S.-S.; Pomerantz, E.M. Parents’ Involvement in Children’s Learning in the United States and China: Implications for Children’s Academic and Emotional Adjustment. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 932–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, B.W.; Wood, D. Personality Development in the Context of the Neo-Socioanalytic Model of Personality. In Handbook of Personality Development; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, J.A. Improving interactional organizational research: A model of person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbaum, F.; Trommsdorff, G. Do Roots and Wings Complement or Oppose One Another?: The Socialization of Relatedness and Autonomy in Cultural Context. In Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research; Grusec, J.E., Hastings, P.D., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 461–489. [Google Scholar]

- Camras, L.A.; Sun, K.; Li, Y.; Wright, M.F. Do Chinese and American Children’s Interpretations of Parenting Moderate Links between Perceived Parenting and Child Adjustment? Parent.-Sci. Pract. 2012, 12, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, W.A.; Kosterman, R.; Hawkins, J.D.; Herrenkohl, T.I.; Lengua, L.J.; McCauley, E. Predicting depression, social phobia, and violence in early adulthood from childhood behavior problems. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 43, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Van Petegem, S.; Beyers, W. Where Do the Cultural Differences in Dynamics of Controlling Parenting Lie? Adolescents as Active Agents in the Perception of and Coping with Parental Behavior. Psychol. Belg. 2016, 56, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singelis, T.M.; Triandis, H.C.; Bhawuk, D.P.S.; Gelfand, M.J. Horizontal and Vertical Dimensions of Individualism and Collectivism: A Theoretical and Measurement Refinement. Cross-Cult. Res. 1995, 29, 240–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C.; Gelfand, M.J. Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Individualism and Collectivism; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Singelis, T.M.; Brown, W.J. Culture, self, and collectivist communication: Linking culture to individual behavior. Hum. Commun. Res. 1995, 21, 354–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashima, Y.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kim, U.; Choi, S.-C.; Gelfand, M.J.; Yuki, M. Culture, gender, and self: A perspective from individualism-collectivism research. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.F.; West, S.G. Measuring individualism and collectivism: The importance of considering differential components, reference groups, and measurement invariance. J. Res. Pers. 2008, 42, 259–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulruf, B.; Hattie, J.; Dixon, R. Development of a new measurement tool for individualism and collectivism. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2007, 25, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. Measuring personal cultural orientations: Scale development and validation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 787–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vliert, E.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ren, X.P. Climato-Economic Imprints on Chinese Collectivism. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2013, 44, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pathways | Effect Size | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| APAS → ABPNS → AWB | 0.171 | 0.029 | 0.117 | 0.232 |

| APAS → ABPNF → AWB | −0.199 | 0.027 | −0.256 | −0.147 |

| Model | CMIN | DF | CFI | RMSEA | ΔCMIN | ΔDF | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconstrained | 89.724 | 36.000 | 0.958 | 0.048 | |||

| Structural weights | 102.754 | 41.000 | 0.952 | 0.049 | 13.030 | 5 | 0.023 |

| Structural residuals | 111.948 | 47.000 | 0.949 | 0.046 | 22.224 | 11 | 0.023 |

| Path | Ⅰ. P-C and A-C | Ⅱ. P-C and A-I | Ⅲ. P-I and A-I | Ⅳ. P-I and A-C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | C.R. | β | C.R. | β | C.R. | β | C.R. | |

| APAS → ABPNS | 0.411 | 3.020 ** | 0.430 | 0.295 ** | 0.393 | 6.844 *** | 0.490 | 5.072 *** |

| APPC → ABPNF | 0.553 | 4.402 *** | 0.351 | 0.314 ** | 0.547 | 10.243 *** | 0.397 | 3.991 *** |

| APPC → ABPNS | 0.085 | 0.623 | 0.036 | 0.027 | −0.111 | −1.926 | −0.126 | −1.306 |

| APAS → ABPNF | 0.231 | 1.836 | −0.267 | −0.220 | −0.036 | −0.676 | −0.195 | −1.957 |

| ABPNS → AWB | 0.557 | 4.948 *** | 0.276 | 0.330 ** | 0.478 | 12.302 *** | 0.535 | 7.775 *** |

| ABPNF → AWB | −0.212 | −1.887 | −0.561 | −0.556 ** | −0.372 | −9.592 *** | −0.345 | −5.014 *** |

| APAS → ABPNS | APPC → ABPNF | APPC → ABPNS | APAS → ABPNF | ABPNS → AWB | ABPNF → AWB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ⅰ-Ⅱ | −0.354 | −1.476 | −0.308 | −0.354 | −1.135 | −3.154 |

| Ⅰ-Ⅲ | −0.262 | −0.308 | −1.239 | −0.262 | 0.289 | −1.734 |

| Ⅰ-Ⅳ | 0.150 | −1.19 | −1.219 | 0.150 | 0.857 | −1.443 |

| Ⅱ-Ⅲ | 0.197 | 1.673 | −0.951 | 0.197 | 1.736 | 2.421 |

| Ⅱ-Ⅳ | 0.599 | 0.448 | −0.949 | 0.599 | 2.098 | 2.143 |

| Ⅲ-Ⅳ | 0.616 | −1.371 | −0.163 | 0.616 | 0.869 | 0.087 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, T.; Gai, X.; Wang, S.; Gai, S. The Relationship between Parenting Behaviors and Adolescent Well-Being Varies with the Consistency of Parent–Adolescent Cultural Orientation. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030193

Yang T, Gai X, Wang S, Gai S. The Relationship between Parenting Behaviors and Adolescent Well-Being Varies with the Consistency of Parent–Adolescent Cultural Orientation. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(3):193. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030193

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Tixiang, Xiaosong Gai, Su Wang, and Stanley Gai. 2024. "The Relationship between Parenting Behaviors and Adolescent Well-Being Varies with the Consistency of Parent–Adolescent Cultural Orientation" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 3: 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030193

APA StyleYang, T., Gai, X., Wang, S., & Gai, S. (2024). The Relationship between Parenting Behaviors and Adolescent Well-Being Varies with the Consistency of Parent–Adolescent Cultural Orientation. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030193