Destructive and Constructive Interparental Conflict, Parenting Stress, Unsupportive Parenting, and Children’s Insecurity: Examining Short-Term Longitudinal Dyadic Spillover and Crossover Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

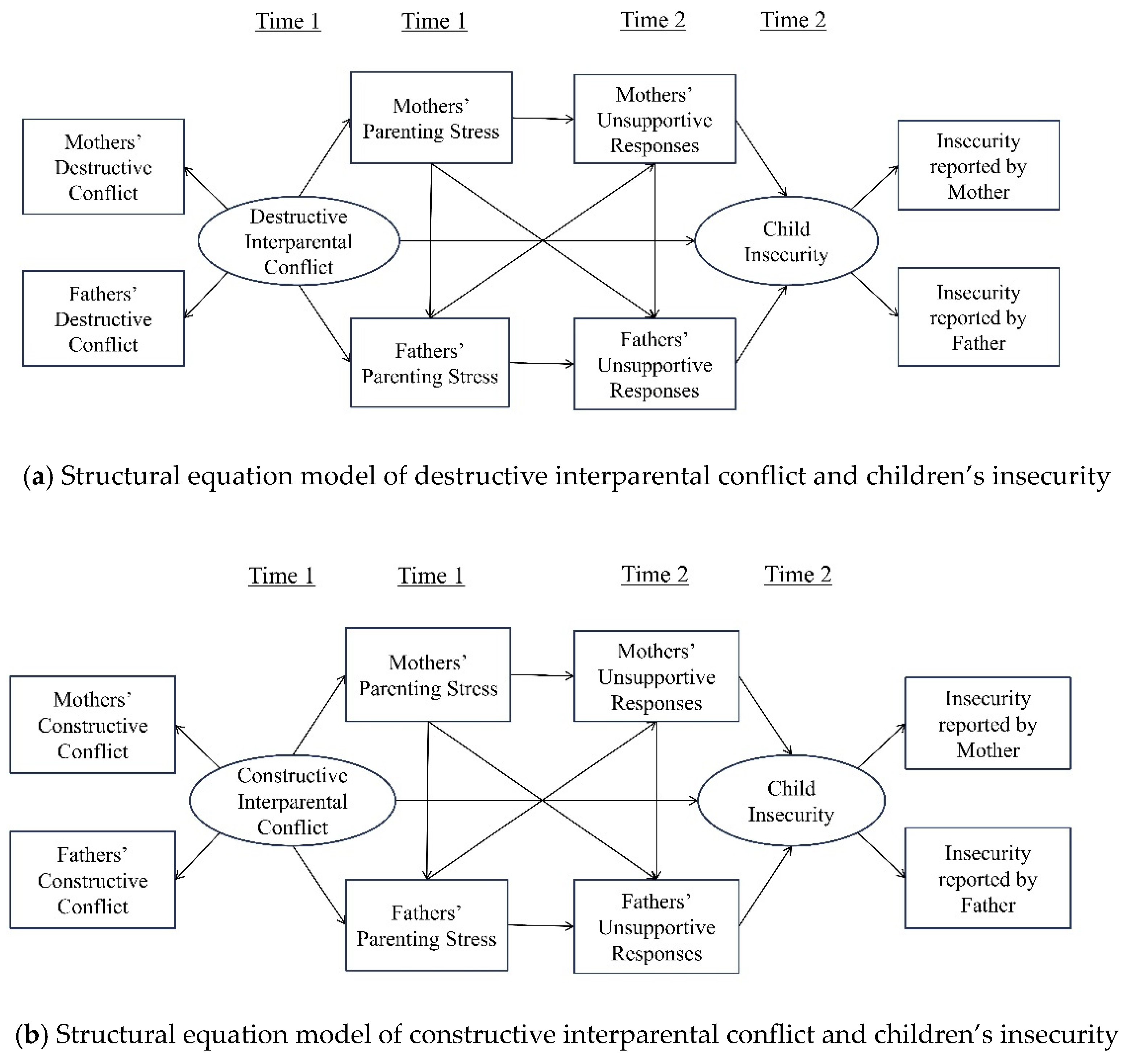

1.1. Spillover Effects of the Mother-Father Relationship on the Parent–Child Relationship

1.2. Crossover Effects of Mothers and Fathers in the Relationship Between Parenting Stress and Parenting Behavior

1.3. Role of Constructive Conflict in Reducing Child Insecurity

1.4. Current Research

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Interparental Conflict

2.2.2. Parenting Stress

2.2.3. Parental Unsupportive Responses

2.2.4. Children’s Insecurity

2.2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Model Fit Verification

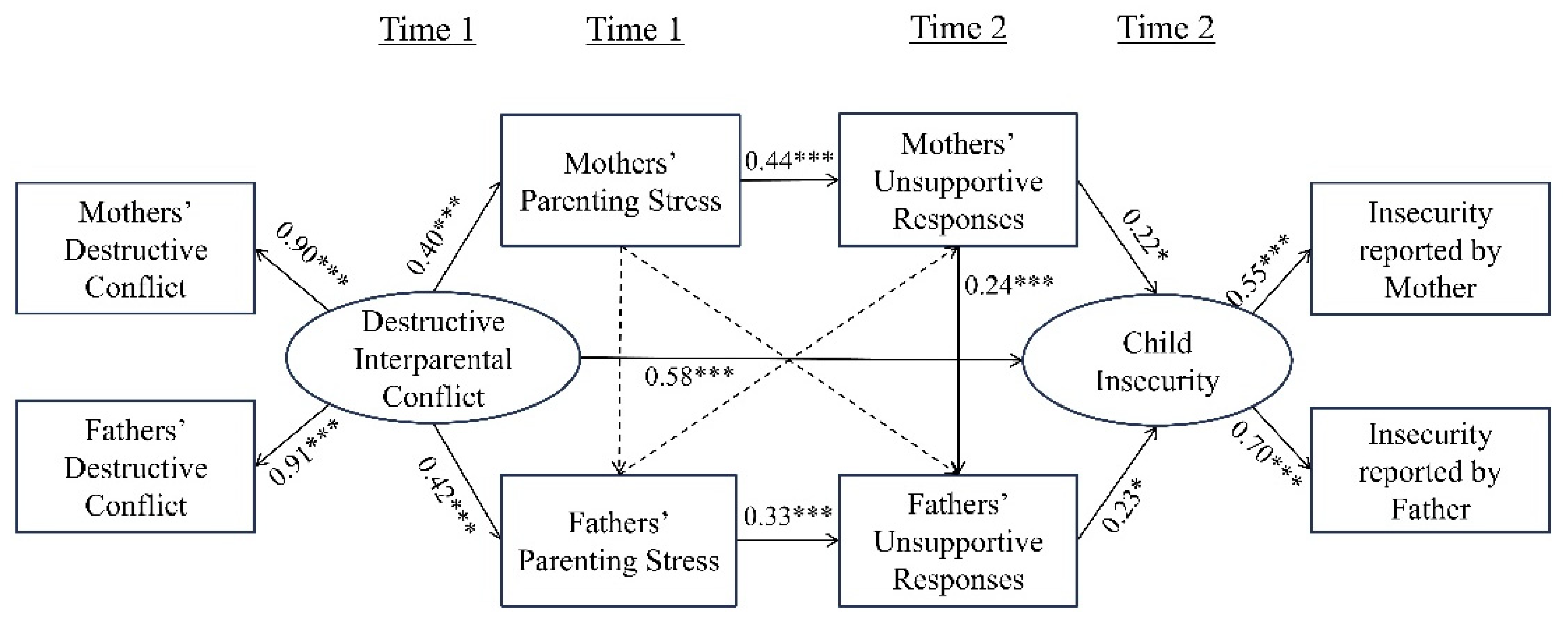

3.2.1. Destructive Interparental Conflict Model

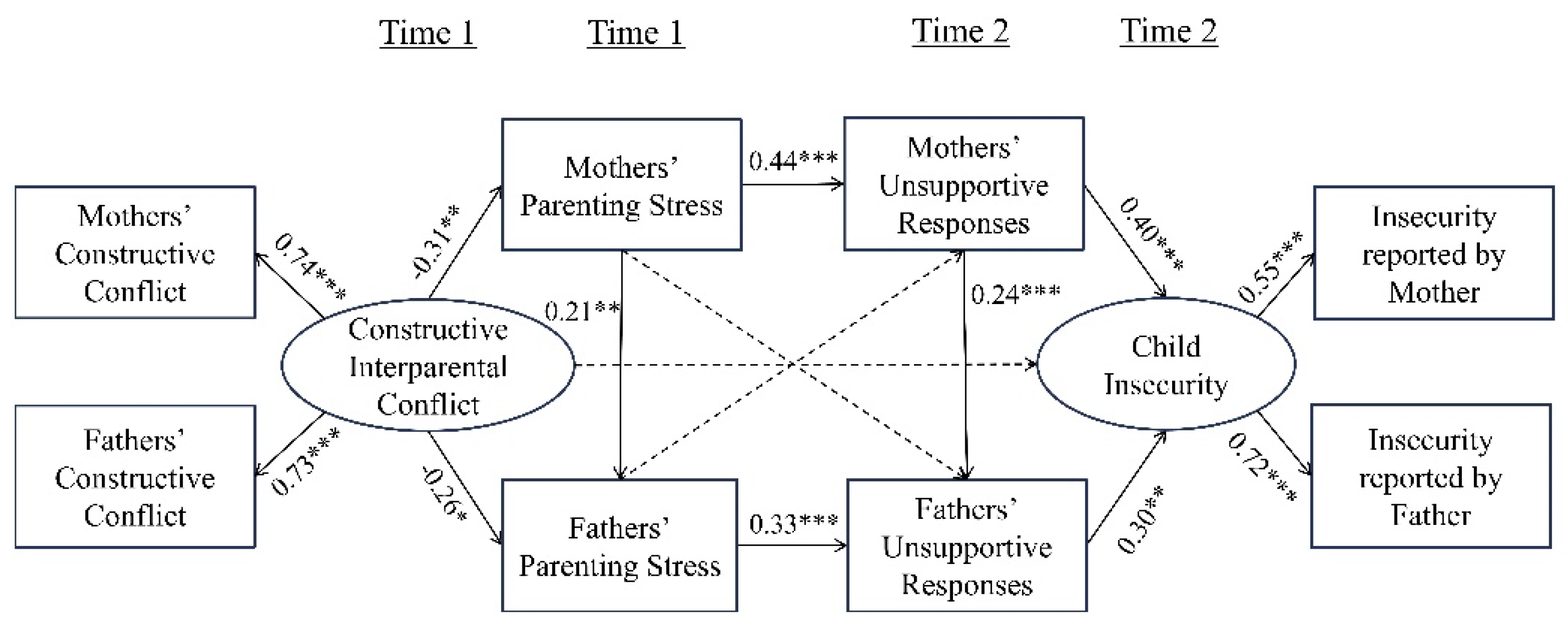

3.2.2. Constructive Interparental Conflict Model

3.3. Mediation Model Verification

3.3.1. Destructive Interparental Conflict Mediation Model

3.3.2. Constructive Interparental Conflict Mediation Model

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T. Marital Conflict and Children: An Emotional Security Perspective; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McCoy, K.P.; George, M.R.; Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T. Constructive and destructive marital conflict, parenting, and children’s school and social adjustment. Soc. Dev. 2013, 22, 641–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, X.; Chen, F.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, X.; Luo, Y.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Y. The relationship between parental conflict and preschool children’s behavior problems: A moderated mediation model of parenting stress and child emotionality. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 95, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.E.; Brophy-Herb, H.E. Dyadic relations between interparental conflict and parental emotion socialization. J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 3564–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erel, O.; Burman, B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 118, 108–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, K.J.; Lindahl, K.M.; Malik, N.M.; Laurenceau, J.P. Marital conflict, maternal and paternal parenting, and child adjustment: A test of mediation and moderation. J. Fam. Psychol. 2006, 20, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engfer, A. The interrelatedness of marriage and the mother-child relationship. Relatsh. Within Fam. Mutual Influ. 1988, 7, 104. [Google Scholar]

- Warmuth, K.A.; Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T. Constructive and destructive interparental conflict, problematic parenting practices, and children’s symptoms of psychopathology. J. Fam. Psychol. 2020, 34, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, R.R. The determinants of parenting behavior. J. Clin. Child. Psychol. 1992, 21, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnic, K.; Arbona, A.P.Y.; Baker, B.; Blacher, J. Mothers and fathers together: Contrasts in parenting across preschool to early school age in children with developmental delays. Int. Rev. Res. Ment. Retard. 2009, 37, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huth-Bocks, A.C.; Hughes, H.M. Parenting stress, parenting behavior, and children’s adjustment in families experiencing intimate partner violence. J. Fam. Violence 2008, 23, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.E. Parents’ stress factors and parenting behaviors: Test of the spillover, crossover, and compensatory hypotheses. Korean J. Child. Stud. 2018, 39, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, L.L.; Mares, S.H.W.; Otten, R.; Engels, R.C.M.E.; Janssens, J.M.A.M. The co-development of parenting stress and childhood internalizing and externalizing problems. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2016, 38, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, E.M.; Goeke-Morey, M.; Raymond, J. Fathers in family context: Effects of marital quality and marital conflict. In The Role of the Father in Child Development, 4th ed.; Lamb, M., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 196–221. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, M.A.; Deng, M.; Mills-Koonce, W.R.; Willoughby, M.; Cox, M. Interdependence of parenting of mothers and fathers of infants. J. Fam. Psychol. 2008, 22, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnet, K.; Mortelmans, D.; Wouters, E.; Van Leeuwen, K.; Bastaits, K.; Pasteels, I. Parenting stress and marital relationship as determinants of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting. Personal. Relat. 2013, 20, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnet, K.; Wouters, E.; Mortelmans, D.; Pasteels, I.; De Backer, C.; Van Leeuwen, K.; Van Hiel, A. The influence of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress and depressive symptoms on own and partner’s parent-child communication. Fam. Process 2013, 52, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.E. Childcare sharing and family happiness: Analyzing parental and child well-being in the actor-partner interdependence model. Front. Public. Health 2024, 12, 1361998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, J.; Day, R.; Lamb, M.E.; Cabrera, N.J. Should researchers conceptualize differently the dimensions of parenting for fathers and mothers? J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2014, 6, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, C.S.; Overall, N.C.; Henderson, A.M.E.; Low, R.S.T.; Cross, E.J. Conflict-coparenting spillover: The role of actors’ and partners’ attachment insecurity and gender. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeke-Morey, M.C.; Cummings, E.M.; Papp, L.M. Children and marital conflict resolution: Implications for emotional security and adjustment. J. Fam. Psychol. 2007, 21, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemp, M.; Johnson, M.D.; Bodenmann, G. Out of balance? Positivity-negativity ratios in couples’ interaction impact child adjustment. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 55, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, M.; Conger, R.D. Parenting behavior as mediator and moderator of the association between marital problems and adolescent maladjustment. J. Res. Adolesc. 2008, 18, 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryczkowski, M.R.; Jordan, S.S.; Mercer, S.H. Differential relations between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting practices and child externalizing behavior. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2010, 19, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.; Rovine, M. Patterns of marital change across the transition to parenthood: Pregnancy to three years postpartum. J. Marr. Fam. 1990, 52, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownell, C.A.; Kopp, C.B. Socioemotional Development in the Toddler Years: Transitions and Transformations; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Camisasca, E.; Miragoli, S.; Blasio, P.D. Families with distinct levels of marital conflict and child adjustment: Which role for maternal and paternal stress? J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, L.A.; Umemura, T.; Jacobvitz, D.; Hazen, N. Marital conflict and parental responses to infant negative emotions: Relations with toddler emotional regulation. Inf. Behav. Dev. 2015, 40, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauber, R.; Forehand, R.; Thomas, A.M.; Wierson, M. A mediational model of the impact of marital conflict on adolescent adjustment in intact and divorced families: The role of disrupted parenting. Child. Dev. 1990, 61, 1112–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, N.A.; Pitts, S.C.; Hill, N.E.; Roosa, M.W. A mediational model of the impact of interparental conflict on child adjustment in a multiethnic, low-income sample. J. Fam. Psychol. 2000, 14, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, C.; Benson, M.J.; Gerard, J.M. Interparental hostility and early adolescent problem behavior: The mediating role of specific aspects of parenting. J. Res. Adolesc. 2006, 16, 265–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.J.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 793. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D.B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Survey; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1987; Volume 81. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J.W. Missingdata: Analysis and Design; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig, P.K. Assessing the links between interparental conflict and child adjustment: The conflicts and problem-solving scales. J. Fam. Psychol. 1996, 10, 454–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.E.; Seo, S. Interparental conflict and Korean children’s inhibitory control: Testing emotional insecurity as a mediator. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 632052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Kang, H.K. Research: Development of the parenting stress scale. Hum. Ecol. Res. 1997, 35, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fabes, R.A.; Eisenberg, N.; Bernzweig, J. The Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale: Procedures and Scoring; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 1990; Volume 10, p. J002v34n03_05. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J.H. A Study About Parents’ Reactions to Children’s Negative Emotions and Children’s Daily Stress; The Graduate School Ewha Womans University: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, P.T.; Harold, G.T.; Goeke-Morey, M.C.; Cummings, E.M.; Shelton, K.; Rasi, J.A.; Jenkins, J.M. Child emotional security and interparental conflict. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child. Dev. 2002, 67, i-127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.E.; Seo, S. Validity of the Korean version of the security in the marital subsystem—Parent report (K-SIMS-PR). Early Child. Educ. 2020, 40, 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.P. Rewriting Statistical Analysis Structural Equation Model Analysis; Wiseincompany: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browen, M.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit in testing structural equation model. Mark. Sci. 1993, 18, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J. The Role of Model Complexity in the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models; The Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.S. Performance Comparison of Variable Selection Methods Combined with Multiple Imputation with Missing Data; Graduate School of Korea University: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Application; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Loucks, L.A.; Shaffer, A. Joint relation of intimate partner violence and parenting stress to observed emotionally unsupportive parenting behavior. Couple Fam. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2014, 3, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Maat, D.A.; Jansen, P.W.; Prinzie, P.; Keizer, R.; Franken, I.H.A.; Lucassen, N. Examining longitudinal relations between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress, parenting behaviors, and adolescents’ behavior problems. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boele, S.; Van der Graaff, J.; De Wied, M.; Van der Valk, I.E.; Crocetti, E.; Branje, S. Linking parent-child and peer relationship quality to empathy in adolescence: A multilevel meta-analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 1033–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackler, J.S.; Kelleher, R.T.; Shanahan, L.; Calkins, S.D.; Keane, S.P.; O’Brien, M. Parenting stress, parental reactions, and externalizing behavior from ages 4 to 10. J. Marriage Fam. 2015, 77, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, C.M. Cultural Factors Contributing to Relational Conflicts Within Korean/Euro-American Marriages. Ph.D. Thesis, Biola University, La Mirada, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.E. Relations between childhood emotional insecurity, self-esteem, and adulthood marital conflict in South Korea. Fam. Relat. 2023, 72, 1926–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. M_DC | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. F_DC | 0.817 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 3. M_CC | −0.462 ** | −0.344 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 4. F_CC | −0.323 ** | −0.431 ** | 0.540 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 5. M_PS | 0.373 ** | 0.342 ** | −0.245 ** | −0.202 * | 1 | |||||

| 6. F_PS | 0.357 ** | 0.383 ** | −0.219 ** | −0.252 ** | 0.289 ** | 1 | ||||

| 7. M_UR | 0.368 ** | 0.371 ** | −0.206 ** | −0.148 | 0.440 ** | 0.238 ** | 1 | |||

| 8. F_UR | 0.176 * | 0.245 ** | −0.168 * | −0.200 * | 0.085 | 0.380 ** | 0.314 ** | 1 | ||

| 9. M_CI | 0.372 ** | 0.366 ** | −0.073 | −0.086 | 0.315 ** | 0.171 * | 0.339 ** | 0.142 | 1 | |

| 10. F_CI | 0.410 ** | 0.458 ** | −0.163 * | −0.160 * | 0.227 ** | 0.385 ** | 0.320 ** | 0.353 ** | 0.399 ** | 1 |

| M | 0.947 | 0.967 | 2.579 | 2.541 | 2.530 | 2.201 | 2.889 | 2.721 | 1.896 | 1.950 |

| SD | 0.348 | 0.345 | 0.399 | 0.422 | 0.713 | 0.671 | 0.729 | 0.824 | 0.537 | 0.606 |

| S | 0.774 | 0.187 | −1.388 | −1.102 | 0.491 | 0.262 | 0.229 | −0.206 | 0.425 | −0.130 |

| K | 1.321 | −0.030 | 2.496 | 1.136 | 0.007 | −0.255 | −0.418 | 0.966 | −0.296 | 1.433 |

| Pathway | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | → | M_PS | 0.927 *** | 0.927 *** | |

| DC | → | F_PS | 0.912 *** | 0.912 *** | |

| DC | → | M_UR | 0.417 *** | 0.417 *** | |

| DC | → | F_UR | 0.474 *** | 0.474 *** | |

| DC | → | CI | 0.545 *** | 0.076 *** | 0.621 *** |

| M_PS | → | M_UR | 0.450 *** | 0.450 *** | |

| M_PS | → | F_UR | 0.121 ** | 0.121 ** | |

| M_PS | → | CI | 0.049 ** | 0.049 ** | |

| F_PS | → | F_UR | 0.397 *** | 0.397 *** | |

| F_PS | → | CI | 0.033 † | 0.033 † | |

| M_UR | → | F_UR | 0.268 ** | 0.268 ** | |

| M_UR | → | CI | 0.086 † | 0.022 * | 0.109 ** |

| F_UR | → | CI | 0.083 † | 0.083 † | |

| Pathway | Indirect Effect | 95% CI LLCI, ULCI | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | → | M_PS | → | M_UR | → | CI | 0.036 | [0.001, 0.111] | ||

| DC | → | F_PS | → | F_UR | → | CI | 0.030 | [0.001, 0.070] | ||

| DC | → | M_PS | → | M_UR | → | F_UR | → | CI | 0.009 | [0.001, 0.031] |

| Pathway | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | → | M_PS | −0.735 ** | −0.735 ** | |

| CC | → | F_PS | −0.579 ** | −0.146 ** | −0.726 *** |

| CC | → | M_UR | −0.331 ** | −0.331 ** | |

| CC | → | F_UR | −0.377 *** | −0.377 *** | |

| CC | → | CI | −0.094 *** | −0.094 *** | |

| M_PS | → | F_PS | 0.199 * | 0.199 * | |

| M_PS | → | M_UR | 0.450 *** | 0.450 *** | |

| M_PS | → | F_UR | 0.200 *** | 0.200 *** | |

| M_PS | → | CI | 0.094 *** | 0.094 *** | |

| F_PS | → | F_UR | 0.397 *** | 0.397 *** | |

| F_PS | → | CI | 0.042 * | 0.042 * | |

| M_UR | → | F_UR | 0.268 ** | 0.268 ** | |

| M_UR | → | CI | 0.162 ** | 0.029 * | 0.191 *** |

| F_UR | → | CI | 0.107 * | 0.107 * | |

| Pathway | Indirect Effect | 95% CI LLCI, ULCI | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | → | M_PS | → | M_UR | → | CI | −0.054 | [−0.171, −0.006] | ||

| CC | → | F_PS | → | F_UR | → | CI | −0.025 | [−0.089, −0.003] | ||

| CC | → | M_PS | → | M_UR | → | F_UR | → | CI | −0.009 | [−0.037, −0.001] |

| CC | → | M_PS | → | F_PS | → | F_UR | → | CI | −0.006 | [−0.024, −0.001] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, U.; Lee, Y.-E. Destructive and Constructive Interparental Conflict, Parenting Stress, Unsupportive Parenting, and Children’s Insecurity: Examining Short-Term Longitudinal Dyadic Spillover and Crossover Process. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121212

Lee U, Lee Y-E. Destructive and Constructive Interparental Conflict, Parenting Stress, Unsupportive Parenting, and Children’s Insecurity: Examining Short-Term Longitudinal Dyadic Spillover and Crossover Process. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(12):1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121212

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Uiju, and Young-Eun Lee. 2024. "Destructive and Constructive Interparental Conflict, Parenting Stress, Unsupportive Parenting, and Children’s Insecurity: Examining Short-Term Longitudinal Dyadic Spillover and Crossover Process" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 12: 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121212

APA StyleLee, U., & Lee, Y.-E. (2024). Destructive and Constructive Interparental Conflict, Parenting Stress, Unsupportive Parenting, and Children’s Insecurity: Examining Short-Term Longitudinal Dyadic Spillover and Crossover Process. Behavioral Sciences, 14(12), 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121212