Social Interaction, Survival Stress and Smoking Behavior of Migrant Workers in China—An Empirical Analysis Using CHARLS Data from 2013–2018

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Variable Measurement

2.2.1. Smoking Behavior

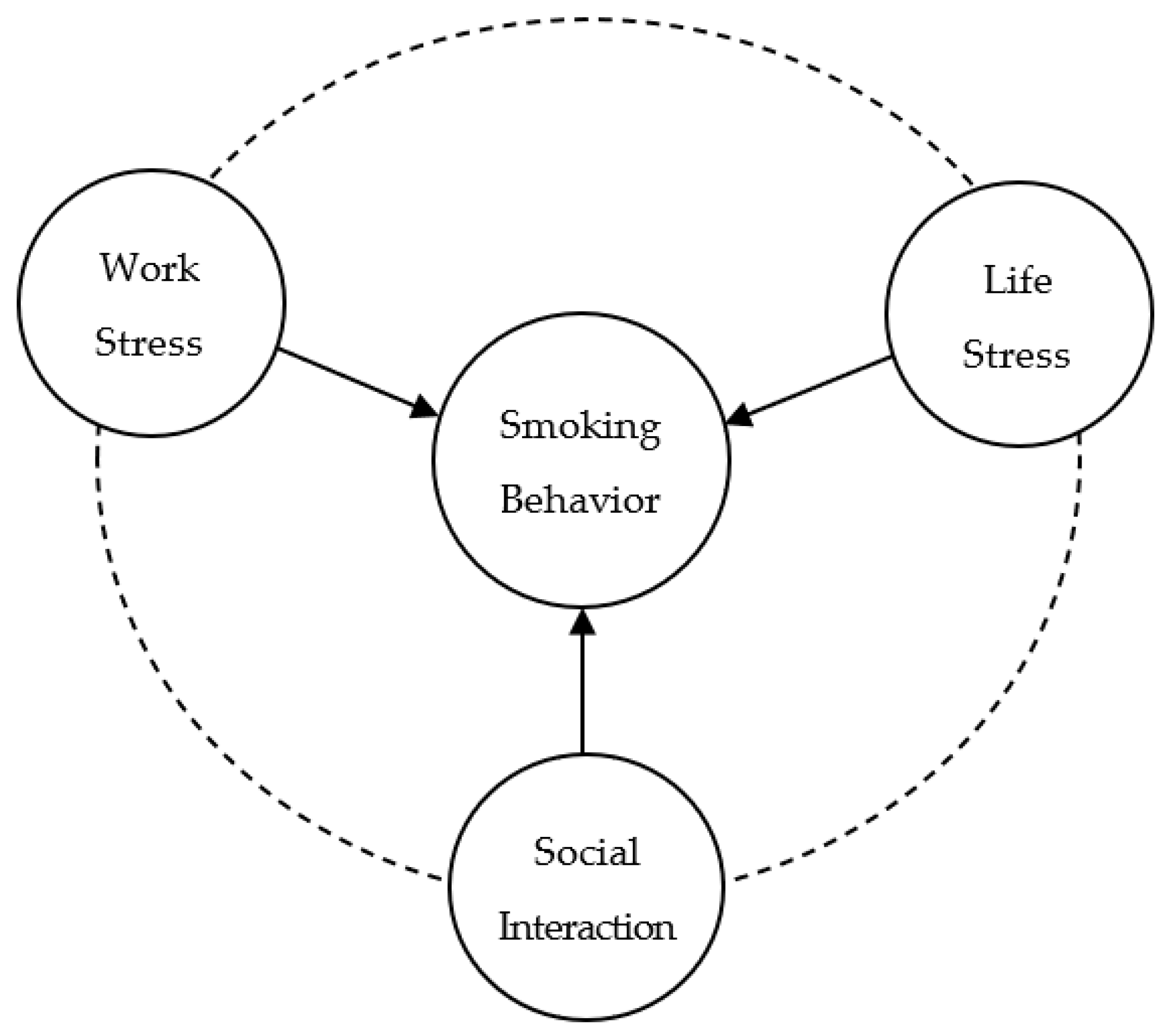

2.2.2. Stress and Social Interaction

2.2.3. Other Control Variables

2.3. Descriptive Statistics and Nonparametric Test

2.4. Model Selection

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Analysis of Preliminary Results

3.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

3.3. Robustness Test

- Winsorization. This study used Winsorization to perform truncation correction on continuous variables by removing extreme values within the upper and lower 1% and 5%, respectively, in order to eliminate the biased influence of extreme values on the model’s regression results. The specific robust regression results could be found in model (5) and (6) in Table 7. Compared to model (2) in Table 5, the regression results remained consistent, regardless of whether 1% or 5% truncation correction was applied. Moreover, after eliminating the impact of extreme values, the regression coefficients of the main independent variables were obviously increased, and their influence effects were further strengthened. This indicated that the empirical analysis results of the Heckman two-stage model used in this study were robust enough.

- Core variable replacement. On the one hand, work stress and life stress were used as replacement variables for the variable of income in this paper. We chose to do this since life stress was a relative value of income and living expenses, while work stress involved working time and indirectly affected income. Model (7) in Table 7 presents the corresponding regression results, contrasting with model (4) in Table 5. It was found that the regression results obtained after rerunning the model had not changed significantly compared to before. On the other hand, social number was used as a replacement variable for the variable of social activity in order to re-measure the key independent variable of social interaction, as presented in model (8). This part aimed to examine whether the number of social activity attendance, another measure of social interaction, had an impact on the two-stage process of smoking behavior among migrant workers. It indicated that the results after re-regression were basically consistent with the previous ones. These findings supported the conclusion that social interaction and life satisfaction affected the two-stage process of smoking behavior among migrant workers, and also verified the robustness of the empirical analysis results of the Heckman two-stage model in this paper.

4. Discussion

4.1. Further Analysis of the Results

4.2. Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Questions and Answers to the CHARLS Questionnaire | CHARLS Code |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking | Q: Have you ever chewed tobacco, smoked a pipe, self-rolled cigarettes or cigars? A: 1. Yes 2. No | da059 |

| Smoking frequency | Q: In one day about how many cigarettes do/did you consume? A: _____Cigarettes | da063 |

| Income | Q: What is the after-tax salary including bonus in the last year/month/week or daily wage? A: _____Yuan | ff002~ff009 |

| Working time | Q: How many hours did you work per day on average in the past year, excluding meal breaks but including any paid or unpaid overtime? A: _____Hours | fe003 |

| Work stress | —— | —— |

| Income per hour | —— | —— |

| Social activity | Q: Have you done any of these activities in the last month? (Code all that apply) A: 1. Interacted with friends 2. Played mahjong, chess, cards 3. Provided help to family, friends or neighbors who do not live with you 4. Went to a sport, social club 5. Took part in a community-related organization 6. Done voluntary or charity work 7. Cared for a sick or disabled adult who does not live with you 8. Attended a training course 9. Stock investment 10. Used the Internet 11. Other 12. None | dc028 |

| Social number | dc028 | |

| Life satisfaction | Q: Please think about your life-as-a-whole. How satisfied are you with your life-as-a-whole? A: 1. Completely satisfied 2. Very satisfied 3. Somewhat satisfied 4. Not very satisfied 5. Not at all satisfied | da056 |

| Life stress | —— | —— |

| Sense of loneliness | Q: I felt lonely? A: 1 = rarely or none of the time, 2 = some or a little, 3 = occasional or moderate, 4= most or all time | dc017 |

| Gender | Q: Interviewer record R’s gender. A: 1.male 2.female | ba000_w2_3 |

| Age | Q: When were you born? A: 1____year 2____month 3____day | zba002_1 |

| Education | Q: what is the highest level of education you have attained now? A: 1. No formal education(illiterate) 2. Did not finish primary school 3. Sishu/home school 4. Elementary school 5. Middle school 6. High school 7. Vocational school 8.two/three-year-college or associate degree | zbd001 |

| Marriage | Q: What is your marital status? A: 1. Married with spouse present 2. Married but not living with spouse temporarily such as work 3. Separated 4. Divorced 5. Widowed 6. Never married | be001 |

References

- World Health Organization. Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2021: Addressing New and Emerging Products. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240032095 (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- World Health Organization. Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Chang, C. Smoking and Its Determinants in Chinese Internal Migrants: Nationally Representative Cross-Sectional Data Analyses. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016, 18, 1719–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wipfli, H. The Tobacco Atlas, Fourth Edition. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 176, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Tartarone, A.; Pérez-Ríos, M.; Novello, S.; Mariniello, A.; Roviello, G.; Zhang, J. Smoking Burden, MPOWER, Future Tobacco Control and Real-World Challenges in China: Reflections on the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2021. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2022, 11, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. China Adult Tobacco Survey Report 2018; People’s Health Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2020; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.S.; Wan, X.; Wang, Q.; Raymond, H.F.; Liu, H.; Ding, D.; Yang, G.; Novotny, T.E. Perceived Discrimination and Smoking Among Rural-to-Urban Migrant Women in China. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2013, 15, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Census (No. 7). Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202105/t20210510_1817192.html (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Li, P.; Li, W. Economic Status and Social Attitudes of Migrant Workers in China. China World Econ. 2007, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florkowski, W.J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, H. Social Isolation: A Key to Explain a Migrant Worker Cigarette Smoking. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Abler, D. Interactions between Cigarette and Alcohol Consumption in Rural China. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2010, 11, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Wu, J.; Rockett, I.R.H.; Abdullah, A.S.; Beard, J.; Ye, J. Smoking Patterns among Chinese Rural–Urban Migrant Workers. Public Health 2009, 123, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, S.M.; Retneswari, M.; Moy, F.-M.; Darus, A.; Koh, D. Job Stressors and Smoking Cessation among Malaysian Male Employees. Occup. Med. 2012, 62, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcão, V.; Candeias, P.; Stefanovska-Petkovska, M.; Pintassilgo, S.; Machado, F.L.; Virgolino, A.; Santos, O. Mental Health and Well-Being of Migrant Populations in Portugal Two Years after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J.; Starke, D.; Chandola, T.; Godin, I.; Marmot, M.; Niedhammer, I.; Peter, R. The Measurement of Effort-Reward Imbalance at Work: European Comparisons. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 1483–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Li, X.; Wang, B.; Hong, Y.; Fang, X.; Qin, X.; Stanton, B. Discrimination, Perceived Social Inequity, and Mental Health among Rural-to-Urban Migrants in China. Community Ment. Health J. 2011, 47, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hu, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, R.; Hu, F.; Xu, C.; Yu, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Reliability and Validity of the Defeat Scale among Internal Migrant Workers in China: Decadence and Low Sense of Achievement. Healthcare 2023, 11, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, H.; Wang, T.; Wang, T.; Yang, H.; Gong, J.; Shen, Y.; Dai, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, S.; et al. Determinants of Tobacco Smoking among Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Shanghai. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, D.L.; Hong, O.; Gillen, M.; Bates, M.N.; Okechukwu, C.A. Cigarette Smoking in Building Trades Workers: The Impact of Work Environment. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2012, 55, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, S.H.; Goldman, N.; Massey, D.S. Healthier before They Migrate, Less Healthy When They Return? The Health of Returned Migrants in Mexico. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, L.; Wang, Y.; Yu, S. Marital Conflict, Family Socioeconomic Status, and Depressive Symptoms in Migrant Children: A Moderating Mediational Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiscock, R.; Bauld, L.; Amos, A.; Fidler, J.A.; Munafò, M. Socioeconomic Status and Smoking: A Review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1248, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyers, S.; Dragano, N.; Möbus, S.; Beck, E.-M.; Stang, A.; Möhlenkamp, S.; Jöckel, K.H.; Erbel, R.; Siegrist, J. Poor Social Relations and Adverse Health Behaviour: Stronger Associations in Low Socioeconomic Groups? Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, X.; Stanton, B.; Fang, X.; Lin, D.; Cole, M.; Liu, H.; Yang, H. Cigarette Smoking among Rural-to-Urban Migrants in Beijing, China. Prev. Med. 2004, 39, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaura, R.; Shadel, W.G.; Britt, D.M.; Abrams, D.B. Response to Social Stress, Urge to Smoke, and Smoking Cessation. Addict. Behav. 2002, 27, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Rockett, I.R.H.; Yang, T.; Cao, R. Work Stress, Life Stress, and Smoking among Rural-Urban Migrant Workers in China. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurieva, S.; Kõiv, K.; Tararukhina, O. Migration and Adaptation as Indicators of Social Mobility Migrants. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Smith, J.P.; Strauss, J.; Yang, G. Cohort Profile: The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Strauss, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Gong, J.; Meng, Q.; Wang, G.; Wang, H. China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study Wave 4 User’s Guide; National School of Development, Peking University: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Byles, J.E.; Xu, X.; Zhang, M.; Wu, X.; Hall, J.J. Association between Nighttime Sleep and Successful Aging among Older Chinese People. Sleep Med. 2016, 22, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, D.M.; Mahler, D.G.; Lakner, C.; Atamanov, A.; Tetteh Baah, S.K. Assessing the Impact of the 2017 PPPs on the International Poverty Line and Global Poverty; Policy Research Working Paper, No. 9941; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, J.J. Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error. Econometrica 1979, 47, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z. Socioeconomic Predictors of Smoking and Smoking Frequency in Urban China: Evidence of Smoking as a Social Function. Health Promot. Int. 2004, 19, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; Shou, J.; Xia, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, S.; Pan, Z. The Prevalence of Cigarette Smoking Among Rural-to-Urban Migrants in China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Subst. Use Misuse 2016, 51, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-H.; Kim, M.-J.; Lee, H.-J. A Study on the Factors Influencing Smoking in Multicultural Youths in Korea. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWall, C.N.; Pond, R.S. Loneliness and Smoking: The Costs of the Desire to Reconnect. Self Identity 2011, 10, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shen, J.J.; Sotero, M.; Li, C.A.; Hou, Z. Income, Occupation and Education: Are They Related to Smoking Behaviors in China? PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz, P.M.; House, J.S.; Lepkowski, J.M.; Williams, D.R.; Mero, R.P.; Chen, J. Socioeconomic Factors, Health Behaviors, and Mortality: Results from a Nationally Representative Prospective Study of US Adults. JAMA 1998, 279, 1703–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baluja, K.F.; Park, J.; Myers, D. Inclusion of Immigrant Status in Smoking Prevalence Statistics. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eo, Y.-S.; Lee, Y.-H.; Kim, M.-S. Health-Related Behavior and Psychosocial Characteristics of Adolescent Female Smokers in Korea, Compared with Adolescent Male Smokers. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakely, T.; van der Deen, F.S.; Woodward, A.; Kawachi, I.; Carter, K. Do Changes in Income, Deprivation, Labour Force Status and Family Status Influence Smoking Behaviour over the Short Run? Panel Study of 15 000 Adults. Tob. Control. 2014, 23, e106–e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruhm, C.J. Good Times Make You Sick. J. Health Econ. 2003, 22, 637–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.J.; Yu, D.; Wen, W.; Shu, X.-O.; Saito, E.; Rahman, S.; Gupta, P.C.; He, J.; Tsugane, S.; Xiang, Y.-B.; et al. Tobacco Smoking and Mortality in Asia: A Pooled Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e191474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition | CHARLS Code |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: | ||

| Smoking | Smoking behavior | da059 |

| Smoking frequency | How many cigarettes per day | da063 |

| Independent variable: | ||

| Work dimension | ||

| Income | Income per month from employment (yuan) | ff002~ff009 |

| Income per hour | Converted into income per hour (yuan) ① | —— |

| Working time | Working time including overtime per day | fe003 |

| Work stress | Relative index of work intensity per day | —— |

| Life dimension | ||

| Life satisfaction | How satisfied you are with your live | dc028 |

| Life stress | Relative index of income and basic living expenses ② | —— |

| Social interaction | ||

| Social activity | Take part in social activities | da056 |

| Social number | How many social activities per week | —— |

| Sense of loneliness | Degree to which you feel lonely | dc017 |

| Control variable: | ||

| Gender | Male or female | ba000_w2_3 |

| Age | Years | zba002_1 |

| Education | The highest education received | zbd001 |

| Marriage | Marital status | be001 |

| Categorical Variable | Value Description | Year | Freq. (n) | Pct. (%) | Year | Freq. (n) | Pct. (%) | Year | Freq. (n) | Pct. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 1 = smoking, 0 = no smoking | 0 | 2013 | 143 | 61.37 | 2015 | 132 | 35.11 | 2018 | 131 | 37.43 |

| 1 | 2013 | 90 | 38.63 | 2015 | 244 | 64.89 | 2018 | 219 | 62.57 | ||

| Social activity | 1 = yes, 0 = no participating | 0 | 2013 | 152 | 43.68 | 2015 | 153 | 41.46 | 2018 | 172 | 44.33 |

| 1 | 2013 | 196 | 56.32 | 2015 | 216 | 58.54 | 2018 | 216 | 55.67 | ||

| Social number | 0 = none, 1 = one term, 2 = two terms, 3 = three or more items | 0 | 2013 | 152 | 43.68 | 2015 | 153 | 41.46 | 2018 | 172 | 44.33 |

| 1 | 2013 | 105 | 30.17 | 2015 | 130 | 35.23 | 2018 | 120 | 30.93 | ||

| 2 | 2013 | 54 | 15.52 | 2015 | 54 | 14.63 | 2018 | 55 | 14.18 | ||

| 3 | 2013 | 37 | 10.63 | 2015 | 32 | 8.67 | 2018 | 41 | 10.57 | ||

| Life satisfaction | 0 = not at all satisfied, 1 = not very satisfied, 2 = somewhat satisfied, 3 = very and completely satisfied | 0 | 2013 | 4 | 1.16 | 2015 | 1 | 0.27 | 2018 | 3 | 0.81 |

| 1 | 2013 | 31 | 9.01 | 2015 | 13 | 3.54 | 2018 | 22 | 5.95 | ||

| 2 | 2013 | 240 | 69.77 | 2015 | 189 | 51.50 | 2018 | 211 | 57.03 | ||

| 3 | 2013 | 69 | 20.96 | 2015 | 164 | 44.69 | 2018 | 134 | 36.22 | ||

| Sense of loneliness | 0 = rarely or none of the time, 1 = some or a little, 2 = occasional or moderate, 3 = most or all time | 0 | 2013 | 290 | 84.80 | 2015 | 310 | 84.24 | 2018 | 301 | 81.35 |

| 1 | 2013 | 30 | 8.77 | 2015 | 28 | 7.61 | 2018 | 35 | 9.46 | ||

| 2 | 2013 | 13 | 3.80 | 2015 | 23 | 6.25 | 2018 | 16 | 4.32 | ||

| 3 | 2013 | 9 | 2.63 | 2015 | 7 | 1.90 | 2018 | 18 | 4.86 | ||

| Gender | 1 = male, 0 = female | 0 | 2013 | 84 | 21.65 | 2015 | 87 | 22.42 | 2018 | 86 | 22.16 |

| 1 | 2013 | 304 | 78.35 | 2015 | 301 | 77.58 | 2018 | 302 | 77.84 | ||

| Education | 0 = no formal education, 1 = did not finish primary school, home school, elementary school, 2 = middle school, 3 = high school, vocational school, 4= two/three-year-college or associate degree | 0 | 2013 | 25 | 6.44 | 2015 | 25 | 6.44 | 2018 | 25 | 6.44 |

| 1 | 2013 | 147 | 37.89 | 2015 | 147 | 37.89 | 2018 | 147 | 37.89 | ||

| 2 | 2013 | 148 | 38.14 | 2015 | 148 | 38.14 | 2018 | 148 | 38.14 | ||

| 3 | 2013 | 64 | 16.49 | 2015 | 64 | 16.49 | 2018 | 64 | 16.49 | ||

| 4 | 2013 | 4 | 1.03 | 2015 | 4 | 1.03 | 2018 | 4 | 1.03 | ||

| Marriage | 0 = never married, 1 = separated, divorced, widowed, 2 = married but not living with spouse temporarily, 3 = married with spouse present | 0 | 2013 | 2 | 0.52 | 2015 | 2 | 0.52 | 2018 | 2 | 0.52 |

| 1 | 2013 | 15 | 3.87 | 2015 | 20 | 5.15 | 2018 | 23 | 5.93 | ||

| 2 | 2013 | 41 | 10.57 | 2015 | 43 | 11.08 | 2018 | 43 | 11.08 | ||

| 3 | 2013 | 330 | 85.05 | 2015 | 323 | 83.25 | 2018 | 320 | 82.47 | ||

| Observations | Survey sample of migrant workers from three follow-up waves | 388 | |||||||||

| Continuous Variable | Value Description | Year | Mean | Std. DEV. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking frequency | Number of cigarettes smoked per day (cigarettes) | 2013 | 19.311 | 13.312 | 1 | 60 |

| 2015 | 20.033 | 12.828 | 1 | 70 | ||

| 2018 | 20.516 | 13.443 | 1 | 80 | ||

| Income | Income per month from employment (yuan) | 2013 | 2563.339 | 2106.732 | 400 | 23,000 |

| 2015 | 2669.041 | 1607.887 | 460 | 12,000 | ||

| 2018 | 3044.851 | 1943.985 | 400 | 15,000 | ||

| Working time | Working time including overtime per day (hour) | 2013 | 8.723 | 1.845 | 2 | 12 |

| 2015 | 8.482 | 1.942 | 1 | 12 | ||

| 2018 | 8.491 | 1.963 | 1 | 12 | ||

| Work stress | Work intensity per day: (working hours)/(standard hours) | 2013 | 1.090 | 0.231 | 0.250 | 1.5 |

| 2015 | 1.060 | 0.243 | 0.125 | 1.5 | ||

| 2018 | 1.061 | 0.245 | 0.125 | 1.5 | ||

| Income per hour | Income per hour: income per month/26/working time per day | 2013 | 11.694 | 8.601 | 2.25 | 76.67 |

| 2015 | 13.299 | 8.396 | 1.67 | 60.00 | ||

| 2018 | 15.540 | 12.295 | 1.67 | 120.00 | ||

| Life stress | Life stress per day: (income per day)/(the latest global poverty standard by Word Bank in 2022) | 2013 | 6.638 | 5.455 | 1.036 | 59.558 |

| 2015 | 6.911 | 4.164 | 1.191 | 31.074 | ||

| 2018 | 7.885 | 5.034 | 1.036 | 38.842 | ||

| Age | Years | 2013 | 53.227 | 5.045 | 45 | 65 |

| 2015 | 55.227 | 5.045 | 47 | 67 | ||

| 2018 | 58.227 | 5.045 | 50 | 70 | ||

| Observations | Survey sample of migrant workers from three follow-up waves | 388 | ||||

| Gender | Social Number | Smoking Behavior | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Total | 0 | 1 | Total | |

| 0 = female | 114 | 90 | 29 | 13 | 246 | 239 | 16 | 255 |

| 1 = male | 363 | 265 | 134 | 97 | 859 | 167 | 537 | 704 |

| Total | 477 | 355 | 163 | 110 | 1105 | 406 | 553 | 959 |

| Test parameter | Pearson = 11.51, Prob = 0.009 | Pearson = 375.77, Prob < 0.001 | ||||||

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | First | Second | First | Second | First | Second | |

| Income | 0.000 (>0) *** (4.040) | −0.002 † (−1.841) | 0.000 (>0) (0.406) | −0.000 (>0) (−0.573) | 0.000 (>0) *** (3.948) | −0.002 † (−1.741) | 0.000 (>0) (0.437) | −0.000 (>0) (−0.166) |

| Social activity | 0.185 † (1.841) | −0.189 (−0.069) | 0.252 * (1.968) | 6.482 (1.408) | 0.192 † (1.886) | −0.799 (−0.293) | 0.253 † (1.955) | 5.007 (1.045) |

| Life satisfaction | 0.141 † (1.653) | −4.887 * (−2.215) | −0.043 (−0.399) | −2.648 † (−1.892) | 0.145 † (1.697) | −5.140 * (−2.359) | −0.044 (−0.408) | −2.762 † (−1.960) |

| Sense of loneliness | 0.075 (0.965) | −1.981 (−1.372) | 0.201 † (1.820) | 1.426 (0.472) | 0.067 (0.857) | −1.444 (−1.062) | 0.200 † (1.801) | 1.191 (0.383) |

| Work stress | —— | —— | —— | —— | 0.146 (0.688) | −12.180 *** (−3.530) | −0.077 (−0.299) | −11.185 *** (−3.597) |

| Gender | —— | —— | 2.692 *** (12.376) | 56.691 (0.746) | —— | —— | 2.698 *** (12.330) | 40.595 (0.516) |

| Age | —— | —— | 0.023 † (1.955) | 0.066 (0.157) | —— | —— | 0.023 † (1.885) | −0.068 (−0.161) |

| Education | —— | —— | 0.073 (0.928) | −1.679 (−1.154) | —— | —— | 0.064 (0.815) | −2.488 † (−1.806) |

| Marriage | —— | —— | −0.144 (−1.097) | −0.278 (−0.113) | —— | —— | −0.137 (−1.046) | −0.068 (−0.028) |

| IMR | —— | −37.983 * (−1.706) | —— | 21.245 (0.536) | —— | −37.759 * (−1.770) | —— | 12.014 (0.292) |

| _cons | −0.527 ** (−2.394) | 64.089 *** (2.678) | −3.052 *** (−3.546) | −40.385 (−0.361) | −0.695 ** (−2.212) | 77.067 *** (3.053) | −2.939 *** (−3.216) | 0.118 (0.001) |

| N | 658 | 392 | 658 | 392 | 653 | 388 | 653 | 388 |

| Variables | (2)- Eastern Region | (2)- Central-Western | (4)- Eastern Region | (4)- Central-Western | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | First | Second | First | Second | First | Second | |

| Income | −0.000 (>0) (−0.727) | −0.000 (>0) (−0.680) | 0.000 (>0) ** (2.611) | 0.001 (0.531) | −0.000 (>0) (−0.472) | −0.000 (>0) (−0.824) | 0.000 (>0) * (2.458) | 0.001 (0.661) |

| Social activity | 0.486 ** (2.899) | 1.039 (0.128) | −0.053 (−0.229) | 4.907 † (1.907) | 0.459 ** (2.694) | 6.776 (0.887) | −0.022 (−0.095) | 4.539 † (1.806) |

| Life satisfaction | −0.276 † (−1.950) | −0.186 (−0.041) | 0.289 (1.560 | −0.861 (−0.258) | −0.270 † (−1.902) | −3.714 (−0.833) | 0.290 (1.541) | −1.274 (−0.402) |

| Sense of loneliness | 0.132 (0.901) | −1.171 (−0.501) | 0.365 † (1.955) | 2.047 (0.624) | 0.154 (1.037) | 0.626 (0.242) | 0.342 † (1.805) | 2.785 (0.927) |

| Work stress | —— | —— | —— | —— | −0.351 (−1.022) | −11.284 † (−1.717) | 0.410 (0.956) | −9.910 † (−1.683) |

| Gender | 2.864 *** (9.732) | −17.379 (−0.237) | 2.534 *** (6.819) | 42.734 (0.984) | 2.871 *** (9.683) | 41.977 (0.577) | 2.494 *** (6.700) | 50.364 (1.193) |

| Age | 0.041 * (2.517) | −0.448 (−0.667) | 0.010 (0.520) | −0.050 (−0.211) | 0.041 * (2.486 | 0.079 (0.118) | 0.010 (0.494) | −0.158 (−0.668) |

| Education | −0.034 (−0.334) | −1.280 (−1.107) | 0.253 † (1.831) | −2.241 (−0.853) | −0.058 (−0.551) | −2.356 † (−1.679) | 0.256 † (1.842) | −2.421 (−0.959) |

| Marriage | −0.255 (−1.530) | 0.472 (0.127) | 0.140 (0.560) | 6.446 * (2.200) | −0.244 (−1.466) | −2.486 (−0.690) | 0.170 (0.679) | 6.071 * (2.018) |

| IMR | —— | −15.642 (−0.421) | —— | 13.692 (0.572) | —— | 14.196 (0.383) | —— | 15.918 (0.687) |

| _cons | −3.245 ** (−2.841) | 72.756 (0.670) | −4.224 ** (−2.919) | −40.856 (−0.549) | −2.887 * (−2.366) | −1.834 (−0.018) | −4.657 ** (−2.964) | −30.312 (−0.399) |

| N | 416 | 226 | 242 | 166 | 413 | 223 | 240 | 165 |

| Variables | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | First | Second | First | Second | First | Second | |

| Income | 0.000 (>0) (0.606) | −0.000 (>0) (−0.016) | 0.000 (>0) (0.986) | 0.000 (>0) (0.311) | —— | —— | 0.000 (>0) (0.498) | −0.000 (>0) (−0.679) |

| Social activity | 0.252 * (1.969) | 6.170 (1.399) | 0.255 * (1.991) | 3.896 (1.111) | 0.253 † (1.955) | 5.007 (1.045) | —— | —— |

| Social number | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | 0.115 † (1.788) | 1.928 (0.884) |

| Life satisfaction | −0.046 (−0.418) | −2.664 † (−1.956) | −0.050 (−0.457) | −2.344 * (−2.089) | −0.044 (−0.408) | −2.762 † (−1.960) | −0.047 (−0.427) | −2.369 † (−1.632) |

| Sense of loneliness | 0.201 † (1.818) | 1.543 (0.535) | 0.201 † (1.814) | 1.155 (0.511) | 0.200 † (1.801) | 1.191 (0.383) | 0.197 † (1.799) | 0.269 (0.083) |

| Work stress | —— | —— | —— | —— | −0.077 (−0.299) | −11.185 *** (−3.597) | —— | —— |

| Life stress | —— | —— | —— | —— | 0.006 (0.437) | −0.029 (−0.166) | —— | —— |

| Gender | 2.685 *** (12.321) | 56.859 (0.785) | 2.672 *** (12.247) | 37.765 (0.668) | 2.698 *** (12.330) | 40.595 (0.516) | 2.690 *** (12.329) | 23.577 (0.286) |

| Age | 0.024 * (1.977) | 0.083 (0.206) | 0.024 * (2.009) | −0.026 (−0.082) | 0.023 † (1.885) | −0.068 (−0.161) | 0.022 † (1.847) | −0.129 (−0.305) |

| Education | 0.073 (0.929) | −1.494 (−1.071) | 0.072 (0.915) | −1.307 (−1.198) | 0.064 (0.815) | −2.488 † (−1.806) | 0.063 (0.789) | −2.390 (−1.688) |

| Marriage | −0.144 (−1.083) | −0.145 (−0.062) | −0.140 (−1.066) | 0.225 (0.124) | −0.137 (−1.046) | −0.068 (−0.028) | −0.137 (−1.046) | 0.745 (0.297) |

| IMR | —— | 21.496 (0.567) | —— | 12.452 (0.419) | —— | 12.014 (0.292) | —— | 3.832 (0.089) |

| _cons | −3.083 *** (−3.579) | −42.967 (−0.401) | −3.143 *** (−3.645) | −16.600 (−0.196) | −2.939 ** (−3.216) | 0.118 (0.001) | −2.936 *** (−3.441) | 10.295 (0.087) |

| N | 658 | 392 | 658 | 392 | 653 | 388 | 658 | 392 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kong, F.; Chen, H.; Cheng, Y. Social Interaction, Survival Stress and Smoking Behavior of Migrant Workers in China—An Empirical Analysis Using CHARLS Data from 2013–2018. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 680. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080680

Kong F, Chen H, Cheng Y. Social Interaction, Survival Stress and Smoking Behavior of Migrant Workers in China—An Empirical Analysis Using CHARLS Data from 2013–2018. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(8):680. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080680

Chicago/Turabian StyleKong, Fanzhen, Huiguang Chen, and Yu Cheng. 2023. "Social Interaction, Survival Stress and Smoking Behavior of Migrant Workers in China—An Empirical Analysis Using CHARLS Data from 2013–2018" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 8: 680. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080680

APA StyleKong, F., Chen, H., & Cheng, Y. (2023). Social Interaction, Survival Stress and Smoking Behavior of Migrant Workers in China—An Empirical Analysis Using CHARLS Data from 2013–2018. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 680. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080680