Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Evidence of Construct Validity in Argentinians

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Sampling Procedure

2.2. Data Collection Instruments

2.3. Data Analysis Process

- 1-

- Due to the variability in items 6 and 7 on frequency and so as to use consistent criteria for the response format, these indicators were respecified prior to subsequent analysis. The original response format for items 6 and 7 is open and does not provide categorised response options. In this case, the question refers to indicating the number of times the person has made suicide attempts. Since the originally reported frequencies ranged from 0 to 15, the recoding consisted of requesting that values greater than 5 be taken with the value 5, while the rest of the values remained with the original value. So here, respecification consisted of recoding the responses with the range of 0 to 5, as is the case with the rest of the questions on frequency.

- 2-

- Because the scale assesses two distinct facets of suicide severity and uses a specific response format for each one (i.e., it assesses the occurrence of indicators based on dichotomous responses and the frequency with which these indicators have presented using a 5-point Likert scale), we decided to carry out two separate factor analyses: a factor analysis for the occurrence indicators and a factor analysis for the frequency indicators.

- 3-

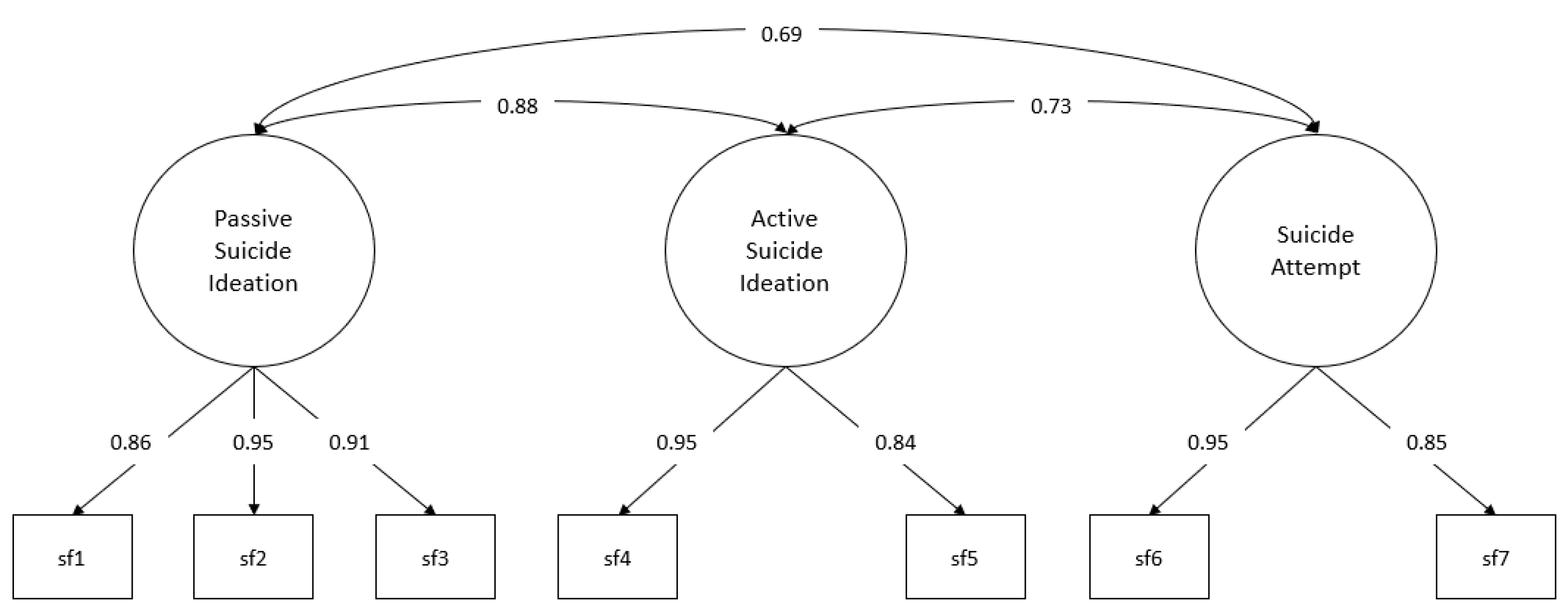

- Measurement models for three correlated factors were specified, which examine suicide severity in ascending order. This model is consistent with the aim of the C-SSRS where the intention is to distinguish the domains of suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviour based on their severity degree [11]. In this sense, the elaboration and objectives followed by the C-SSRS are contrary to the traditional view that considers suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviour a unidimensional construct. In line with previous applications of the C-SSRS [12], the specified measurement models defined the factors based on the degree of severity. Thus, the following factors were specified in the measurement models: (1) passive suicidal ideation (i.e., no intent to act); (2) active suicidal ideation (i.e., intent to act); and (3) suicide attempt. Although it would be possible to specify a two-factor measurement model, separating only between suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviour, the C-SSRS has been constructed for the purpose of gradually differentiating different levels of suicidal severity. In this sense, we consider that the fact of not differentiating within the dimension of suicidal ideation between passive and active suicidal ideation detracts from the discriminative capacity of the measurements in terms of being able to distinguish between less severe ideation (i.e., passive suicidal ideation) and more severe ideation (i.e., active suicidal ideation).

- 4-

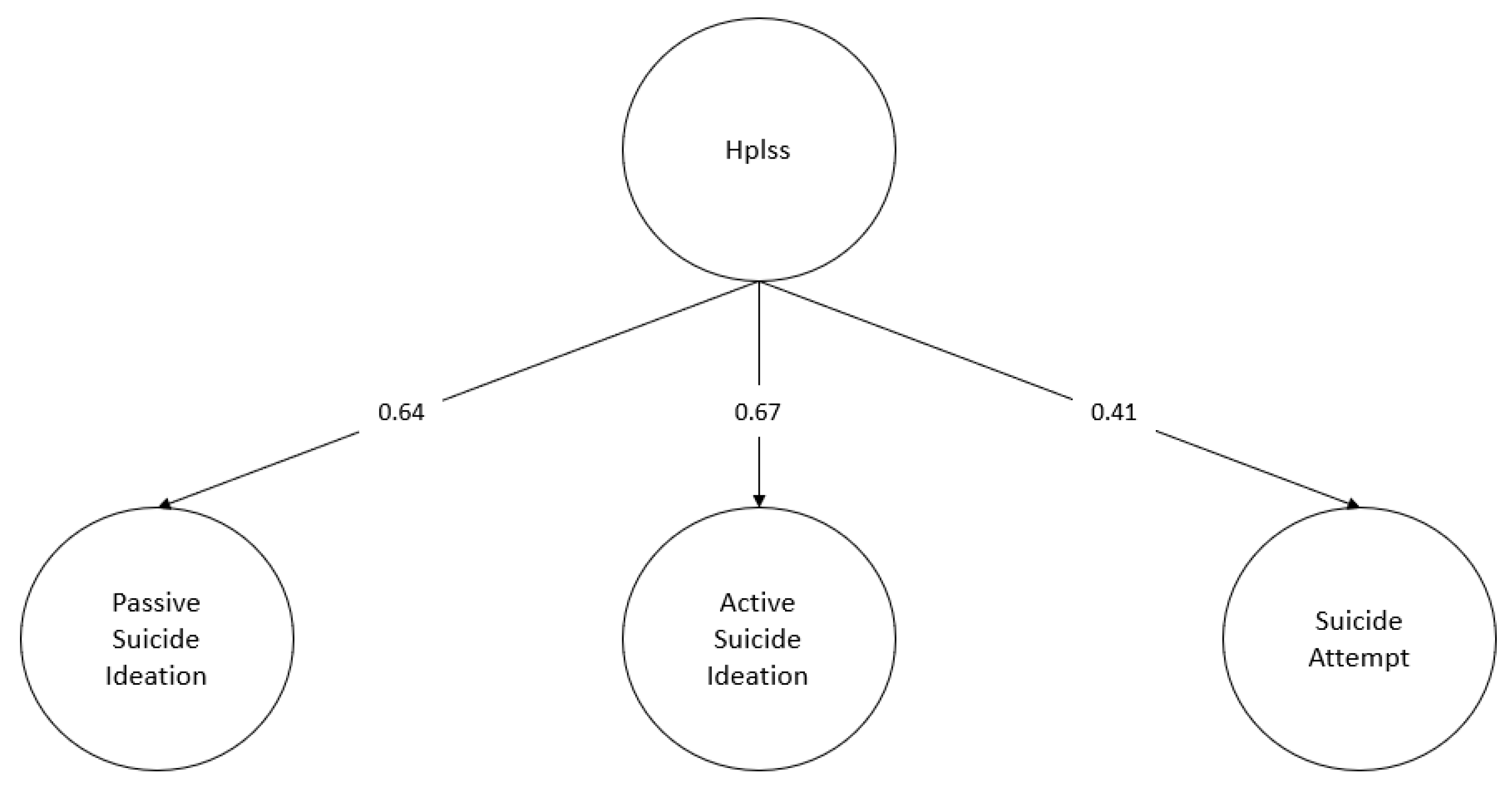

- Regarding the structural model, the specified model considers the effect of the hopelessness factor on the suicide severity factors (i.e., passive suicidal ideation, active suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt). Here, we hypothesise that hopelessness will have a stronger relationship with suicidal ideation than suicide attempts. This hypothesis is based on the cognitive model of suicidal behaviour [22], where it is postulated that suicidal ideation is the strongest predictor of the suicidal act, whereas hopelessness is the strongest predictor of suicidal ideation.

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Models: Source of Structural Evidence

3.2. Structural Models: Source of External Evidence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flores Kanter, P.E. El Lugar de La Psicología En Las Investigaciones Empíricas Del Suicidio En Argentina: Un Estudio Bibliométrico. Interdiscip. Rev. Psicol. Cienc. Afines 2017, 34, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Kanter, P.E.; García-Batista, Z.E.; Moretti, L.S.; Medrano, L.A. Towards an Explanatory Model of Suicidal Ideation: The Effects of Cognitive Emotional Regulation Strategies, Affectivity and Hopelessness. Span. J. Psychol. 2019, 22, E43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghavi, M. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Suicide Mortality 1990 to 2016: Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. BMJ 2019, 364, l94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Suicide Worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-002664-3.

- Ministerio de Seguridad Argentina Suicidios (Sistema de Alerta Temprana—Suicidios). 2022. Available online: https://estadisticascriminales.minseg.gob.ar/reports/Informe_Suicidios.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-004933-8.

- Reifels, L.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Kõlves, K.; Francis, J. Implementation Science in Suicide Prevention. Crisis 2022, 43, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirtley, O.J.; Janssens, J.J.; Kaurin, A. Open Science in Suicide Research Is Open for Business. Crisis 2022, 43, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arensman, E.; Scott, V.; De Leo, D.; Pirkis, J. Suicide and Suicide Prevention from a Global Perspective. Crisis 2020, 41, S3–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millner, A.J.; Robinaugh, D.J.; Nock, M.K. Advancing the Understanding of Suicide: The Need for Formal Theory and Rigorous Descriptive Research. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020, 24, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posner, K.; Brown, G.K.; Stanley, B.; Brent, D.A.; Yershova, K.V.; Oquendo, M.A.; Currier, G.W.; Melvin, G.A.; Greenhill, L.; Shen, S.; et al. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial Validity and Internal Consistency Findings from Three Multisite Studies with Adolescents and Adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viguera, A.C.; Milano, N.; Laurel, R.; Thompson, N.R.; Griffith, S.D.; Baldessarini, R.J.; Katzan, I.L. Comparison of Electronic Screening for Suicidal Risk with the Patient Health Questionnaire Item 9 and the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale in an Outpatient Psychiatric Clinic. Psychosomatics 2015, 56, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.P.; Tan, T.M. Suicide Screening Tools and Their Association with Near-Term Adverse Events in the ED. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 33, 1680–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roaten, K.; Johnson, C.; Genzel, R.; Khan, F.; North, C.S. Development and Implementation of a Universal Suicide Risk Screening Program in a Safety-Net Hospital System. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2018, 44, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nock, M.K.; Ursano, R.J.; Heeringa, S.G.; Stein, M.B.; Jain, S.; Raman, R.; Sun, X.; Chiu, W.T.; Colpe, L.J.; Fullerton, C.S.; et al. Mental Disorders, Comorbidity, and Pre-Enlistment Suicidal Behavior among New Soldiers in the U.S. Army: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Suicide Life. Threat. Behav. 2015, 45, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVylder, J.E.; Jahn, D.R.; Doherty, T.; Wilson, C.S.; Wilcox, H.C.; Schiffman, J.; Hilimire, M.R. Social and Psychological Contributions to the Co-Occurrence of Sub-Threshold Psychotic Experiences and Suicidal Behavior. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 1819–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universidad Nacional de Rosario. Rosario, Argentina., Universidad Nacional de Rosario.; Serrani Azcurra, D. Psychometric Validation of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale in Spanish-Speaking Adolescents. Colomb. Médica 2017, 48, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Halabí, S.; Sáiz, P.A.; Burón, P.; Garrido, M.; Benabarre, A.; Jiménez, E.; Cervilla, J.; Navarrete, M.I.; Díaz-Mesa, E.M.; García-Álvarez, L.; et al. Validación de la versión en español de la Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (Escala Columbia para Evaluar el Riesgo de Suicidio). Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2016, 9, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International Test Commission. International Guidelines on Computer-Based and Internet-Delivered Testing. Int. J. Test. 2006, 6, 143–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigold, A.; Weigold, I.K.; Russell, E.J. Examination of the Equivalence of Self-Report Survey-Based Paper-and-Pencil and Internet Data Collection Methods. Psychol. Methods 2013, 18, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Weissman, A.; Lester, D.; Trexler, L. The Measurement of Pessimism: The Hopelessness Scale. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1974, 42, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Kanter, P.E.; Toro, R.; Alvarado, J.M. Internal Structure of Beck Hopelessness Scale: An Analysis of Method Effects Using the CT-C(M–1) Model. J. Pers. Assess. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R, RStudio, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2020.

- Rhemtulla, M.; Brosseau-Liard, P.É.; Savalei, V. When Can Categorical Variables Be Treated as Continuous? A Comparison of Robust Continuous and Categorical SEM Estimation Methods under Suboptimal Conditions. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B. Update to Core Reporting Practices in Structural Equation Modeling. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2017, 13, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E. Neither Cronbach’s Alpha nor McDonald’s Omega: A Commentary on Sijtsma and Pfadt. Psychometrika 2021, 86, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, T.D.; Pornprasertmanit, S.; Schoemann, A.M.; Rosseel, Y. SemTools: Useful Tools for Structural Equation Modeling. R Package Version 0.5-6. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=semTools (accessed on 15 October 2022)2022.

- Beck, A.T.; Rush, A.J. (Eds.) Cognitive Therapy of Depression; The Guilford Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy Series; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; ISBN 978-0-89862-919-4. [Google Scholar]

- Vecco, G.A.; Flores-Kanter, P.E.; Luque, L.E. Análisis Psicométrico Del Inventario de Orientación Suicida ISO-19, En Adolescentes Cordobeses Escolarizados. Rev. Evaluar 2021, 21, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | n | % | Pyscho_treat | n | % | Pyschi_treat | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 410 | 79.46% | Yes | 142 | 27.52% | Yes | 44 | 8.53% |

| Male | 101 | 19.57% | No | 374 | 72.48% | No | 472 | 91.47% |

| Non-binary | 5 | 0.97% |

| Primary | n | % | Secondary | n | % | T/U | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 513 | 99.42% | Yes | 503 | 97.48% | Yes | 251 | 48.64% |

| No | 3 | 0.58% | No | 13 | 2.52% | No | 265 | 51.36% |

| Employment Status | n | % | Income | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homemaker | 10 | 1.94% | <40k | 177 | 34.3% |

| Self-employed | 139 | 26.94% | 40–80k | 167 | 32.36% |

| Unemployed | 49 | 9.5% | 80–95k | 59 | 11.43% |

| Student | 86 | 16.67% | 95–120k | 48 | 9.3% |

| Retired or pensioner | 26 | 5.04% | 120–380k | 61 | 11.82% |

| Dependent | 206 | 39.92% | >380k | 4 | 0.78% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Flores-Kanter, P.E.; Alesandrini, C.; Alvarado, J.M. Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Evidence of Construct Validity in Argentinians. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030198

Flores-Kanter PE, Alesandrini C, Alvarado JM. Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Evidence of Construct Validity in Argentinians. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(3):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030198

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlores-Kanter, Pablo Ezequiel, Claudia Alesandrini, and Jesús M. Alvarado. 2023. "Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Evidence of Construct Validity in Argentinians" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 3: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030198

APA StyleFlores-Kanter, P. E., Alesandrini, C., & Alvarado, J. M. (2023). Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Evidence of Construct Validity in Argentinians. Behavioral Sciences, 13(3), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030198