Abstract

The current study investigated the effects of Chinese young adult users’ perceived information overload (i.e., the daily perception of exposure to excessive information) on their intention to stop using short-form video applications. Specifically, this study accomplished this by measuring the direct and indirect effects of social media fatigue, maladaptive coping, and life dissatisfaction in relation to users’ intention to discontinue their use of short-form video applications. The data were collected using a web-based survey and validated questionnaire, with a sample of 340 young adult (18–26 years old) respondents. The results indicated that perceived information overload had a direct effect on the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications. Moreover, short-form video fatigue, maladaptive coping, and life dissatisfaction all played mediating roles in the relationship between perceived information overload and the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications among young adults in China.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the influence of social media has risen continuously [1]. Despite the growing popularity of Facebook and WeChat, there is evidence that the number of daily visits and the total time spent on Facebook and other SNSs (social networking sites) by users has reduced drastically [2]. Similarly, Chinese short-form video applications have been shown to be susceptible to declining user interest during the COVID-19 pandemic [3]. For instance, the average daily active users of Kuaishou (the second-largest short-form video service in China) decreased by 2.1 million in the second quarter of 2021, and the average monthly active users fell by 13.6 million [4]. Additionally, since January 2018, the number of newly added users has declined as the Douyin, Kuaishou, Huaoxiao, and Watermelon video applications have reached mature industry status [5]. However, the mechanisms behind such phenomena during the pandemic in China remain underexplored.

In recent years, short-form video applications have been recognized as the fastest-growing forms of social media [6]. They are also known to be among the leading entertainment and social media applications in China [7]. Specifically, Douyin (known as TikTok overseas) has reached 600 million daily active users [8]. Short-form video applications fit in well with Chinese young adult users’ busy lives, provide entertainment, and have been applied to every aspect of Chinese peoples’ daily lives [9]. Regardless of its growing popularity and advantages, the dark side of social media usage has attracted the attention of researchers in recent years [10]. For instance, Liu et al. [11] found that gen Z social media users’ social media fatigue and fear of COVID-19 have increased their willingness to discontinue the use of social media. The discontinued use of social media is recognized as one of the negative outcomes of problematic media use [11,12,13]. This has amplified the effect of losing users from social media platforms, which in turn may be harmful to the growth of the social media industry [14]. Users quitting or switching applications costs users time and effort to adapt to new social media platforms [13,15]. Eventually, social media providers may lose their base users as well as potential revenue [16]. As discussed above, investigating this phenomenon is critically important for two reasons. First, short-form video application developers are eager to understand why users have tended to discontinue the use of their products during the COVID-19 pandemic [17]. Second, no empirical studies have applied a theoretical framework or identified the mechanisms that lead to the discontinued use of short-form applications.

The discontinued use of media has been discussed thoroughly in the field of digital and social media [18,19]. Fu et al. [12] conceptualized the discontinued use of media as users making the decision to reduce or abandon their use of social media. Previous research has demonstrated that the perception of exposure to excessive amounts of information has led to individuals discontinuing social media use or switching social media platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic [11,13]. Stress-coping theory indicates that maladaptive coping strategies involve individuals’ behavioral attempts to decrease their level of discomfort when they are maintaining negative emotional states [20,21]. Based on this theory, a previous study found that maladaptive coping is positively associated with individuals’ discontinued use of social media [22]. Moreover, Rajkumar [23] indicated that perceived threats related to COVID-19 have not only reduced the quality of individuals’ physical health but also their life satisfaction levels. Additionally, problematic internet use is recognized as one of the factors that has decreased Palestinians’ life satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic [21]. Ultimately, this has amplified individuals’ discontinued use of media [24,25]. Overall, prior studies have provided the clear and convincing finding that cognitive (short-form video fatigue and maladaptive coping) and psychological factors (life dissatisfaction) have increased individuals’ discontinuation of the use of social media. However, to the best of our knowledge, whether these factors interact to produce the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications amid the COVID-19 pandemic in China remains largely underexplored.

To fill this gap, this study drew on stress-coping theory as a guide, further exploring the effect of the perceived information overload from short-form video applications on Chinese young adult (18–26 years old) users’ intent to stop using said applications. This study also explored the mediating roles of short-form video fatigue, maladaptive coping, and life dissatisfaction in this process.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Stress-Coping Theory and Maladaptive Coping

Lazarus and Folkman defined coping as an individual’s response to stressful situations involving important and potentially negative consequences [26]. Several scholars have developed different types of coping categories [27,28]. Among those categories, two dimensions of coping categories have been widely applied in prior studies [29,30,31]. A recent study defined adaptive coping as a strategy that gives an individual the time he/she needs to self-reflect and refocus on what is important, whereas maladaptive coping refers to a strategy that involves efforts to regulate the psychological consequences of stressful or potentially stressful events [32]. However, maladaptive strategies deny the user feasible measures to improve the situation and encourage them to use their energy to suppress thoughts, emotions, and actions related to coping with stress, which results in users feeling that their ability to cope is increasingly limited [22]. In social media use and consumer behavioral studies, coping theory has been explained as the way individuals adapt to and handle social media overload. For instance, a previous study demonstrated that while users are dealing with technostressors, maladaptive strategies are likely to be used, which has unhealthy outcomes for perceiving stress [15]. Additionally, individuals who rely on maladaptive coping strategies tend to have emotional and negative consequences (e.g., anger, avoidance, or disengaged coping) [33]. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in China, Ni et al. [34] indicated that Chinese adults have spent too much time on social media searching for COVID-19-related information updates, which in turn has further increased their symptoms of depression and anxiety. Furthermore, a previous study demonstrated that perceived stress amid the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened Chinese users’ level of negative coping [35]. In response to this issue, individuals are more likely to use maladaptive coping strategies to deal with perceived technostressors as opposed to applying adaptive coping strategies, such as avoiding the use of social media. For instance, Lin [22] suggested that the more likely individuals are to use maladaptive coping styles, the more likely they are to discontinue their media usage. Considering the studies discussed above, maladaptive coping strategies can be applied to the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications in China and provide a clarifying perspective for the context of this research.

2.2. Effect of Information Overload on Intention and Cognitive and Psychological Factors

In recent years, cutting-edge new media platforms have greatly attracted Chinese young adults’ interest. Short-form video applications are among the most frequently used communication platforms in China [7]. The content created on short-form video applications is primarily user-generated [11]. With easy-to-use operation interfaces and functional editing features, short-form video applications offer users a variety of sound effects, video filters, and the ability to upload short-form videos directly from their phone [36,37]. As the latest Chinese investigation demonstrated, the majority of Douyin (TikTok) users are interested in short-form videos on topics such as singing, cooking, physical exercise, traveling, comedy, lip-syncing, and knowledge sharing (e.g., scientific knowledge, health-related knowledge, and skills) [38]. Although positive usage behaviors in short-form video applications have previously been demonstrated [9], scholars have recently focused on investigating whether information overload on TikTok could lead to negative outcomes, including the discontinued use of short-form video applications [39], short-form video fatigue [39], maladaptive coping [40], and life dissatisfaction [41]. Undoubtedly, these studies have suggested that information overload on TikTok directly influences individuals’ cognitive and psychological wellbeing. However, previous studies have failed to investigate such mechanisms during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. They have also failed to identify how information overload from Chinese short-form video applications leads to negative outcomes. Therefore, further investigation is required.

Farhoomand and Drury [42] claimed that when an individual perceives themselves as being exposed to excessive amounts of information, this impairs their ability to handle that information. This phenomenon is conceptualized as “information overload.” In most cases, information overload causes media users to feel overburdened and to experience an increasing level of stress, which results in a negative emotion arousal effect [11]. This study conceptualizes perceived information overload as a phenomenon whereby users receive too much information and communication in a short period of time from push notifications and recommended videos from short-form video applications. A previous study demonstrated that there was a positive relationship between individuals’ perceived information overload and Facebook users’ discontinued usage of the platform [12]. Similarly, a recent study found that social media users’ perceived information overload on Weibo was positively associated with their discontinued usage of the platform [43]. Therefore, Chinese young adult users’ information overload on short-form video applications is likely to increase their intention to discontinue their use of short-form video applications.

One of the critical factors that predicts individuals’ discontinued use of social media is social media fatigue [39]. Social media fatigue is described as a decrease in individuals’ interest in using social media [44]. In the context of this research, short-form video fatigue refers to the decrease in users’ interest in using those applications or to users’ intention to stop using short-form video applications. Cyberpsychology researchers have also investigated how perceived information overload can have an impact on how social media users deal with perceived technostress and suffer from feelings of dissatisfaction. For instance, when social media users experienced perceived information overload on social networks, it induced platform fatigue on these networks [45]. Moreover, one scholar found that individuals’ perception of being overloaded with information about COVID-19 was positively associated with their level of social media fatigue [11]. Likewise, a previous study also demonstrated that there is a positive relationship between WeChat users’ perceived information overload and their social media fatigue [46]. Thus, as Chinese young adult users’ information overload on short-form video applications increases, eventually this will increase their level of fatigue with short-form video applications.

Two types of coping strategies are involved in efforts to release stress from various stressful events. Among these coping strategies, maladaptive coping strategies were largely applied by Chinese social media users when they experienced information overload [22]. In our study, maladaptive coping refers to how individuals deal with perceived technostress from short-form videos by adopting a negative solution (e.g., avoidance or anger) and suffering from feelings of dissatisfaction. Recent studies have investigated whether individuals’ perceived information overload amplified their use of maladaptive coping strategies [22,47]. Media behavior scholars have found that when social media users are exposed to excessive information on WeChat, their level of maladaptive coping (e.g., giving up on dealing with stressful situations on WeChat and efforts to cope with exhaustion) increases [48]. Likewise, when college students were exposed to excessive amounts of health information online, instead of choosing positive ways to cope with perceived technostress, they expressed feelings of anger [49]. Therefore, the current study predicted that perceived information overload on short-form applications would be associated an increased level of maladaptive coping.

The factors that determine an individuals’ life dissatisfaction include health behavior, social factors, personality, and mood factors [26]. The current study conceptualizes life dissatisfaction as a reflection of individuals’ negative self-evaluation of their quality of life, according to their own perceptions, after being exposed to an overload of information on short-form video applications. Previously, Alheneidi [50] explored users’ excessive engagement in social media and how being exposed to information overload leads to an increase in their life dissatisfaction (e.g., distress, negative feelings from social comparison, and negative wellbeing). Perceived COVID-19 information overload is a strong predictor of individuals’ negative wellbeing (life dissatisfaction) [44]. To sum up, it is logical that Chinese young adults’ perceived information overload on short-form video applications may increase their level of life dissatisfaction. The following hypothesis was thus proposed:

H1.

Perceived information overload has a significant and positive effect on (a) the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications, (b) short-form video fatigue, (c) maladaptive coping, and (d) life dissatisfaction.

2.3. The Roles of Cognitive Factors as Mediators

A handful of researchers have found that there is a positive relationship between individuals’ perceived information overload and their levels of social media fatigue [11,27,45] Furthermore, the greater the media fatigue, the more likely it is that users will discontinue their use of social media [10,51]. Similarly, a Chinese study demonstrated that social media users’ exposure to excessive amounts of COVID-19-related information amplified their level of social media fatigue [11], which in turn may increase users’ intention to stop using social media [11,52].

However, previous studies related to media and behavior have demonstrated that social media users’ perceived information overload increases their level of maladaptive coping [22,53,54]. Furthermore, this has further reinforced individuals’ discontinuation of the use of social media [22]. To sum up, it is logical that Chinese young adults’ perceived information overload would increase their level of maladaptive coping. As a result, this would further affect their discontinued use of short-form video applications. The following hypotheses were thus proposed:

H2a.

Short-form video fatigue mediates the relationship between perceived information overload and the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications.

H2b.

Maladaptive coping mediates the relationship between perceived information overload and the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications.

2.4. The Roles of Psychological Factors as a Mediators

Scholars have discussed users’ excessive engagement with social media and how being exposed to information overload leads to increases in their life dissatisfaction (e.g., distress, negative feelings from social comparison, and negative wellbeing) [50]. Eventually, this induces individuals to avoid the use of social media [24,25]. Moreover, exposure to COVID-19-related information has increased individuals’ levels of negative wellbeing (life dissatisfaction) [44], which are amplified along with their frequency of discontinuing the use of social media applications [47].

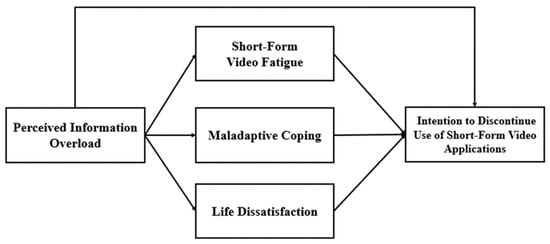

As mentioned above, previous literature has explored life dissatisfaction as one of the key psychological factors that indirectly affects this causal relationship. Therefore, this study argues that life dissatisfaction could mediate the effect of the relationship between perceived information overload and the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications. Hence, the following hypothesis was thus proposed (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

A model of the predictors of the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications.

H3.

Life dissatisfaction mediates the relationship between perceived information overload and the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Design

The current study adopted 5 measures (e.g., perceived information overload, media fatigue, maladaptive coping, life dissatisfaction, and discontinued usage) from existing studies. In addition, all questions related to each measurement were adapted from verified studies [2,22,24,55,56]. However, the measures had not previously been used in the context of Chinese culture. In order to maintain the precision and accuracy of the measures, this study carefully made appropriate modifications. First, the measures were translated from the original English into Chinese by three Chinese-speaking language experts. Later, all researchers compared the original and translated measures until they reached an agreement regarding the translation’s quality and accuracy [57]. Second, content and face validity methods were adopted to revise and eliminate items [58]. In this process, four experts from the Department of Journalism and Media were invited for the evaluation [57]. Third, a pretest was conducted with 15 volunteers who were recruited from Shanghai University and the Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication. Participants were asked to provide any recommendations for the revision if any item was unreadable or ambiguous [59]. We then revised the questionnaire based on the volunteers’ feedback and uploaded the finalized survey to the online survey platform Wenjuanxing. Wenjuanxing is also recognized as one of the most used survey design and dissemination platforms in China. In addition, the platform provides a sampling pool of nearly 260 million registered users in China (excluding Tibet). Based on these remarkable features, it has been utilized by numerous universities and scholars for conducting research related to China [60,61]. The users for this study were selected randomly, sent the survey link, and provided a reward upon their completion of the questionnaire. Permission to conduct the current study was reviewed and approved by the Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication Ethics Committee. The statement of permission was included in the beginning of the online questionnaire. The data were collected from 1 January to 1 October 2022 through an online survey platform. Among the 365 potential respondents who received the survey link, 340 filled out the questionnaire.

3.2. Measurement of Variables

3.2.1. Perceived Information Overload

To observe perceived information overload, we derived the information overload scale from Misra and Stokols’s [55] study. This scale was used to evaluate individuals’ perception of whether they received too much information from short-form video applications. Respondents answered the following questions about their level of agreement using a 5-point Likert scale: (1) “It takes too much effort to manage my subscribed accounts lists’’; (2) “I often feel overwhelmed with the number of notifications I receive on short-form video platforms”; (3) “Sorting through all the information on short-form video platforms takes up too much of my time”; (4) I receive too many recommended videos on the applications (M = 2.80, SD = 2.80, α = 0.65).

3.2.2. Short-Form Video Fatigue

The short-form video fatigue scale was adapted from Bright et al. [2]. The short-form video fatigue scale aimed to assess individuals’ decreased interest in using short-form video applications. Respondents answered regarding their level of agreement with the following questions using a 4-point Likert scale: (1) “I am not interested in all the new things that are happening on short-form video platforms”; (2) “After using short-form video applications, I feel tired or listless”; (3) “Short-form video applications make me feel very frustrated”; or (4) “After using short-form video applications, I feel extremely irritable” (M = 2.94, SD = 0.91, α = 0.84).

3.2.3. Maladaptive Coping

The 3-item maladaptive coping scale was adapted from Lin et al. [22]. This scale evaluates how individuals cope with perceived technostress from short-form video applications by adopting a negative solution and suffering from unsatisfied feelings. Respondents provided their level of agreement to the following questions using a 3-point Likert scale: (1) “I refuse to believe that messy situations have happened on short-form video applications”, (2) “I have given up on trying to deal with stressful situations on short-form video applications”, or (3) “I have given up attempting to cope with stressful situations on short-form video applications” (M = 2.98, SD = 0.78, α = 0.79).

3.2.4. Life Dissatisfaction

To measure life dissatisfaction, we adapted the life dissatisfaction scale created by Diener et al. [55]. The original scale was designed to measure individuals’ overall wellbeing. This study aimed to evaluate negative self-evaluations of quality of life after being exposed to an overload of information on short-form video applications. Therefore, a reversed 5-point Likert scale was applied. In this way, the indicators pointed in the same direction, with higher values identifying higher levels of human suffering [62]. Respondents answered with their level of agreement with the following questions: (1) “For the most part, I think life is close to ideal”; (2) “I think my living conditions are very good”; (3) “I am satisfied with my life”; (4) “So far, I have achieved the things that are important in my life”; or (5) “Even if I could start my life over again, I would not change anything” (M = 3.10, SD = 0.77, α = 0.85).

3.2.5. Intention to Discontinue the Use of Short-Form Video Applications

The intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications scale was adapted from Maier et al. [24]. This scale aims to assess individuals’ willingness to discontinue the use of short-form video applications. Respondents answered with their level of agreement with the following questions using a 4-point Likert scale: (1) “In the future, I will reduce the time I spend on short-form video applications”; (2) “I am planning to take a break from using short-form video applications for a while, but I might use them later”; (3) “I will delete my account on short-form video applications”; or (4) “I have found something more valuable than short-form video applications” (M = 2.88, SD = 0.86, α = 0.84). In order to validate the measurement scales in this study, we performed an explanatory factor analysis (EFA) to evaluate each scale’s level of adequacy. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were applied to perceived information overload (0.62), short-form video fatigue (0.76), maladaptive coping (0.75), life dissatisfaction (0.85), and the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications (0.80). KMO values ranged between 0.6 and 1.0, which indicated that the sampling was adequate [63]. Therefore, this study’s measurement scales were suitable for the data sets. The EFA values of the measurements can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

CR, CA, and AVE values.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Data

In total, 340 valid responses were collected. The demographic characteristics of the survey participants are outlined in Table 2. The respondents were mostly female (N = 221, 65%), single (N = 191, 56.2%), and either undergraduates (N = 219, 64.4%) or postgraduates (N = 83, 24.4). The respondents’ ages ranged from 18 to 21 years old (N = 247, 72.6%), and they had monthly incomes ranging from CNY 7000 to CNY 14,000 (N = 125, 36.8%). The bivariate associations between the key variables are provided in Table 3.

Table 2.

Key demographic characteristics of the survey participants.

Table 3.

Correlations between key variables.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

For testing Hypothesis 1, this study applied four hierarchical regression analyses for the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications, short-form video fatigue, maladaptive coping, and life dissatisfaction. As dependent variables, gender, education, and income were entered in the first block as controlling confounders, and perceived information overload was entered in the second block. The effect of Chinese young adults’ perceived information overload on their intention to discontinue their use of short-form video applications (β = 0.23, p < 0.001), short-form video fatigue (β = 0.43, p < 0.001), maladaptive coping (β = 0.45, p < 0.001), and life dissatisfaction (β = 0.30, p < 0.001) were all found to be significant. Therefore, H1(a–d) are fully supported (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Regression analysis predictors of cognitive and psychological factors.

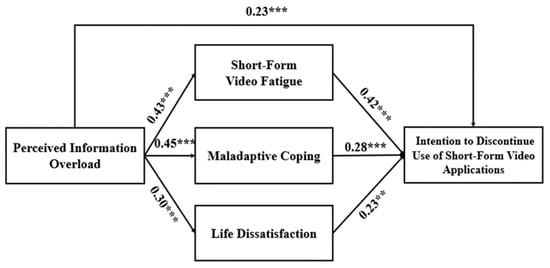

Hayes’ PROCESS macro (model 4) was used to test the mediation analysis of the cognitive and psychological factors’ effects on the relationship between perceived information overload and the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications among Chinese young adults. The current study applied bootstrapping to obtain bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals in order to make statistical inferences about specific indirect effects. Figure 2 indicates the standardized coefficients and significance values for each path in the hypothesized model.

Figure 2.

The effects of predictors of the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The results show that, in the first mediation model, short-form video fatigue bias positively predicted the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications (β = 0.42, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, perceived information overload did not predict the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications (β = 0.45, p > 0.05). The indirect effect was significant (β = 0.18, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.10, 0.28]). Therefore, the full mediation effect of short-form video fatigue was confirmed. The second mediation model’s result indicated that maladaptive coping positively predicted the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications (β = 0.28, p < 0.001). Perceived information overload did not predict the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications (β = 0.11, p > 0.05). The indirect effect was significant (β = 0.12, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.05, 0.20]). Thus, the full mediation effect of maladaptive coping was confirmed. The third mediation model showed that life dissatisfaction positively predicted the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications (β = 0.23, p < 0.01). Perceived information overload significantly predicted the intention to discontinue the use of short-form video applications (β = 0.16, p < 0.01). The indirect effect was significant (β = 0.07, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.02, 0.13]) The partial mediation effect of life dissatisfaction was confirmed. Therefore, H2 and H3 were fully supported.

5. Discussion

Drawing on stress-coping theory, this study explains the effect of Chinese young adult users’ perceived information overload on discontinuing their use of short-form video applications. Moreover, the prime objective of this study was to examine the direct and indirect effects of cognitive (social media fatigue and maladaptive coping) and psychological (life dissatisfaction) factors on Chinese users’ intention to stop using short-form video applications.

In terms of direct effects, perceived information overload was positively associated with Chinese young adults’ discontinued use of short-form video applications. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies [10,12]. For instance, Xie and Tsai [10] indicated that there was a positive relationship between individuals’ perceived information overload and Weibo users’ discontinued usage of the platform. An overview of the past literature showed that there has been limited investigation of the effect of the perceived information overload resulting from short-form video applications on cognitive factors (such as media fatigue). However, this study anticipated that perceived information overload would be positively associated with Chinese young adult users’ short-form video fatigue. This result is in line with those of previous studies, where it was shown that individuals’ perceived excessive exposure to information on social media increased their level of media fatigue [11,27,45]. Among those studies, a previous Chinese study found that perceived information overload on social networks is positively associated with Chinese media users’ platform fatigue on these networks [45]. Stress-coping theory explained how people manage the adverse effects of stress [26]. Among the different types of coping strategies, the use of maladaptive coping strategies may increase due to perceived technostress while using social media (e.g., perceived information overload and binge-watching videos) [53,64]. This study also found that there was a positive relationship between perceived information overload and Chinese young adults’ maladaptive coping, showing continued support for this hypothesis [22,53]. Noticeably, among the negative outcomes of problematic media use, the impact on maladaptive coping was found to be significantly higher compared to the impact on other factors. Similarly, Lewis et al. [65] also found that individuals’ use of maladaptive coping is one of the most significant outcomes predicted by individuals’ frequent use of media to obtain COVID-19-related information. Lastly, this finding demonstrated that perceived information overload has a significant and positive effect on life dissatisfaction. This finding is consistent with that of a prior study showing that media users being exposed to information overload on social media amplifies their life dissatisfaction [50].

In regard to the mediated effect, firstly, short-form video fatigue mediates the relationship between perceived information overload and Chinese young adults’ discontinued use of short-form video applications. This shows consistency with previous studies, which have demonstrated that social media users’ perceived excessive exposure to COVID-19-related information has increased their level of social media fatigue. Ultimately, this has further reinforced users’ intentions to stop using social media [11,52]. Secondly, maladaptive coping acts as a mediator in the relationship between perceived information overload and Chinese young adults’ discontinued use of short-form video applications. This finding is in line with a previous study that found information overload on social media to be a predictor of individuals’ level of maladaptive coping, which in turn further reinforces their intention to discontinue their use of social media [22]. Lastly, Cleofas [66] indicated that college students tended to use social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok) to cope during the COVID-19 lockdown period. Additionally, this study also demonstrated that the greater an individual’s daily use of TikTok, the more likely it was to increase their social media disorder. Eventually, this may increase individuals’ levels of depression, loneliness, low self-esteem, poor sleep quality, etc. [67]. Such negative feelings are also known as “life dissatisfaction”. A prior study demonstrated that life dissatisfaction is positively associated with individuals avoiding the use of social media [24]. The current study’s finding is consistent with those of previous studies [24,25,50], e.g., that life dissatisfaction mediates the relationship between perceived information overload and Chinese young adults’ discontinued use of short-form video applications.

The practical implications of this study relate to three aspects. Firstly, even though short-form video applications have brought a lot of benefits to Chinese people amid the COVID-19 pandemic, they have led to negative effects that are amplified by information overload. Therefore, the providers of short-form video applications should be aware of the potential negative outcomes. Additionally, reducing the number of daily notifications and instead setting more user-friendly alerts, such as push notifications, should ensure that users receive a limited amount of daily information. Secondly, the current study provides empirical evidence that short-form video fatigue is one of the key mediators in the relationship between perceived information overload and the discontinued use of short-form video applications. Moreover, spending time on these applications may induce individuals to experience short-form video fatigue, resulting in users quitting short-form video applications. Therefore, these applications’ providers should also pay more attention to the users’ time limitation when using these applications. In addition, the applications’ service providers can add features to applications that remind users of the recommended healthy amounts of time to spend on these applications. Social support has been shown to be one of the key factors that can offset the level of depression (life dissatisfaction) [68]. Therefore, encouraging family members and work colleagues to share helpful suggestions and guide each other in limiting their exposure to information on short-form video applications can help them manage their wellbeing.

There are several limitations of this study. Firstly, the analysis was conducted using a cross-sectional study. In this type of investigation, it is difficult to identify the direct and indirect effects of the tested factors. Secondly, the respondents’ education was mainly at the undergraduate level. Therefore, these findings cannot be generalized to young adult users in China from all education groups. Lastly, the current study adapted the original scales for measuring individuals discontinuing the use of short-form video applications. Undeniably, it is difficult to measure their actual behavior change. Instead, this study used the perspective of “expected” or “perceived” as a behavior change. A more accurate measurement would be beneficial for future studies.

Future research needs to further investigate the impacts of cognitive and psychological factors. For instance, whether self-efficacy is directly or indirectly associated with the discontinued use of short-form video applications should be analyzed. Similarly, whether an individual’s social comparison is positively or negatively associated with users avoiding the use of short-form video should also be investigated. These potential future studies will contribute to providing a holistic perspective of short-form video users’ behavior.

6. Conclusions

The current study discovered how information overload affects Chinese young adult users’ (18–26 years old) intention to discontinue using short-form video applications during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. This is the first study to explore both the direct and indirect effects of critical factors (short-form video fatigue, maladaptive coping, and life dissatisfaction) on such a relationship. The findings of this study make contributions to behavioral science research in the following aspects: First, the current study fills a gap in the prior literature on the discontinued use of short-form video applications in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Second, this study confirms that both cognitive (social media fatigue and maladaptive coping) and psychological (life dissatisfaction) factors act as mediating mechanisms in the relationship between information overload and Chinese young adult users’ intention to discontinue using short-form video applications. Future studies are recommended to investigate whether self-efficacy and social comparison are directly or indirectly associated with discontinuing the use of short-form video applications. The exploration of these factors will provide a better understanding of the negative outcomes of Chinese short-form video application users’ problematic media use.

Author Contributions

D.C. and Y.M. conceived the study idea. D.C. and Y.M. developed the survey questionnaire and gained ethical approval. D.C. and Y.C. cleaned and analyzed the data. Y.M. helped perform the analysis with constructive discussions. D.C. and Y.M. finalized the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the academic committee of the Network and New Media, Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication (protocol code: L20211220).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- China, Z. Tencent 2Q 2021 Earnings Report: Wechat Monthly Live Reached 1.25 Billion. Available online: https://maimai.cn/article/detail?fid=1653547542&efid=fduttZCtCxo3bK42szZ4lw (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Bright, L.F.; Kleiser, S.B.; Grau, S.L. Too much Facebook? An exploratory examination of social media fatigue. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 44, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohu. Why Are Short Videos Getting Boring These Days? Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/601246977_121465352 (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Jiemianxinwen. Kuaishou Posted a Net Loss of 3.18 Billion Yuan in the Second Quarter and Had 347 Million Average Daily Active Users. Available online: https://www.163.com/dy/article/HFFHUTCA0534A4SC.html (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Qianzhanwang. Analysis of Market Pattern and Development Trend of Short Video Industry in the First Half of 2019 Toutiao Short Video APP Has Strong Competitiveness. Available online: https://www.163.com/dy/article/EM4RTUHR051480KF.html (accessed on 9 August 2019).

- Prost, S. Tiktok and the Growth of Short-Form Video. Available online: https://rootedweb.com/tiktok-and-the-growth-of-short-form-video/ (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Du, X.; Liechty, T.; Santos, C.A.; Park, J. ‘I want to record and share my wonderful journey’: Chinese Millennials’ production and sharing of short-form travel videos on TikTok or Douyin. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ha, L. Why people use TikTok (Douyin) and how their purchase intentions are affected by social media influencers in China: A uses and gratifications and parasocial relationship perspective. J. Interact. Advert. 2021, 21, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Xue, X.; Zhao, Y.C.; Li, J.; Zhu, Q.; Zhao, M. Short-video apps as a health information source for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Information quality assessment of TikTok videos. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e28318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.-Z.; Tsai, N.-C. The effects of negative information-related incidents on social media discontinuance intention: Evidence from SEM and fsQCA. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 56, 101503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, W.; Yoganathan, V.; Osburg, V.-S. COVID-19 information overload and generation Z’s social media discontinuance intention during the pandemic lockdown. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 166, 120600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Pirkkalainen, H.; Salo, M. Social media overload, exhaustion, and use discontinuance: Examining the effects of information overload, system feature overload, and social overload. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, X.; Ma, L. The influences of information overload and social overload on intention to switch in social media. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.S.; Choi, S.B. Stress caused by social media network applications and user responses. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 17685–17698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudioso, F.; Turel, O.; Galimberti, C. The mediating roles of strain facets and coping strategies in translating techno-stressors into adverse job outcomes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lin, S.; Turel, O.; Xu, F. The buffering effect of flow experience on the relationship between overload and social media users’ discontinuance intentions. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 49, 101374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taimeiti. With Tiktok and Kuaishou Grabbing the Market Outside and Paying Users Falling Inside, What Is the Future of Live Shows? Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1708321772136624583&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Anderson, I.A.; Wood, W. Habits and the electronic herd: The psychology behind social media’s successes and failures. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 4, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, X.-K.; Lee, V.-H.; Loh, X.-M.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Ooi, K.-B.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The dark side of mobile learning via social media: How bad can it get? Inf. Syst. Front. 2021, 24, 1887–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frølund Pedersen, H.; Frostholm, L.; Søndergaard Jensen, J.; Ørnbøl, E.; Schröder, A. Neuroticism and maladaptive coping in patients with functional somatic syndromes. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 917–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamid, F.A.; Berte, D.Z.; Bdier, D. Problematic internet use and its association with sleep disturbance and life satisfaction among Palestinians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 8167–8174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Lin, J.; Luo, X.R.; Liu, S. Juxtaposed effect of social media overload on discontinuous usage intention: The perspective of stress coping strategies. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 52, 102066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, C.; Laumer, S.; Weinert, C.; Weitzel, T. The effects of technostress and switching stress on discontinued use of social networking services: A study of Facebook use. Inf. Syst. J. 2015, 25, 275–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettmann, J.E.; Anstadt, G.; Casselman, B.; Ganesh, K. Young adult depression and anxiety linked to social media use: Assessment and treatment. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2021, 49, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivumaa-Honkanen, H.; Honkanen, R.; Viinamaeki, H.; Heikkilae, K.; Kaprio, J.; Koskenvuo, M. Life satisfaction and suicide: A 20-year follow-up study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H. How compulsive WeChat use and information overload affect social media fatigue and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic? A stressor-strain-outcome perspective. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 64, 101690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiffge-Krenke, I. Causal links between stressful events, coping style, and adolescent symptomatology. J. Adolesc. 2000, 23, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, L.E.; Vartanian, L.R.; Pinkus, R.T. Weight stigma predicts poorer psychological well-being through internalized weight bias and maladaptive coping responses. Obesity 2018, 26, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weathers, M.R.; Canzona, M.R.; Fisher, C.L. Digital media as a context for dating abuse: Connecting adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies to young adult women’s well-being. Affilia 2019, 34, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiffge-Krenke, I. Adaptive and maladaptive coping styles: Does intervention change anything? Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2004, 1, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S. Chinese in a Pandemic: TikTok as a Window Into Chinese People’s Lives During COVID-19. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Public Relations and Social Sciences (ICPRSS 2021), Kunming, China, 17–19 September 2021; pp. 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hampel, P.; Petermann, F. Perceived stress, coping, and adjustment in adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 38, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, M.Y.; Yang, L.; Leung, C.M.; Li, N.; Yao, X.I.; Wang, Y.; Leung, G.M.; Cowling, B.J.; Liao, Q. Mental health, risk factors, and social media use during the COVID-19 epidemic and cordon sanitaire among the community and health professionals in Wuhan, China: Cross-sectional survey. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e19009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Yan, L.; Ding, X.; Gan, Y.; Kohn, N.; Wu, J. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general Chinese population: Changes, predictors and psychosocial correlates. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zilberg, I.E. Understanding Young Adults’ TikTok Usage. Undergraduate Honors Thesis, Department of Communication, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, D.B.V.; Chen, X.; Zeng, J. The co-evolution of two Chinese mobile short video apps: Parallel platformization of Douyin and TikTok. Mob. Media Commun. 2021, 9, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinboyang. Short Video Redskins Map Is Coming! Who is the Industry Representative among the 15 Categories and 10 Vertical Categories? Available online: https://www.163.com/dy/article/GTMVVEUR0552POWV.html (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Ye, D.; Cho, D.; Chen, J.; Jia, Z. Empirical investigation of the impact of overload on the discontinuous usage intentions of short video users: A stressor-strain-outcome perspective. Online Inf. Rev. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B.; Biswas, U.N.; Mansukhani, R.T.; Casarín, A.V.; Essau, C.A. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on internet use and escapism in adolescents. Rev. Psicol. Clínica Niños Adolesc. 2020, 7, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DONG, Z.; Xie, T. Why People Love Short-Form Videos? The Motivations for Using Tiktok and Implications for Well-Being. 2022. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4089602 (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Farhoomand, A.F.; Drury, D.H. Managerial information overload. Commun. ACM 2002, 45, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Yang, M.; Jin, X.-L. Differences in the reasons of intermittent versus permanent discontinuance in social media: An exploratory study in Weibo. In Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hilton Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Smith, A.P. Information overload, wellbeing and COVID-19: A survey in China. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, L.; Lu, Y.; Yang, J. Do you get tired of socializing? An empirical explanation of discontinuous usage behaviour in social network services. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H. Unraveling the influence of passive and active WeChat interactions on upward social comparison and negative psychological consequences among university students. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 57, 101510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, K.J.; Lee, S. A Study on the Antecedents and Effects of Social Media Fatigue on Korean Users. Media Econ. Cult. 2022, 20, 7–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Lu, Z.; Kuang, H.; Wang, C. Information avoidance behavior on social network sites: Information irrelevance, overload, and the moderating role of time pressure. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tham, J.S.; Waheed, M. The effects of receiving and expressing health information on social media during the COVID-19 infodemic: An online survey among malaysians. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alheneidi, H. The Influence of Information Overload and Problematic Internet Use on Adults’ Wellbeing; Cardiff University: Cardiff, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, K.; Panda, R.K. Examining the role of social networking fatigue toward discontinuance intention: The multigroup effects of gender and age. J. Internet Commer. 2020, 19, 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z. When I feel invaded, I will avoid it: The effect of advertising invasiveness on consumers’ avoidance of social media advertising. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, C.E.; Reed, P. Threat and efficacy uncertainty in news coverage about bed bugs as unique predictors of information seeking and avoidance: An extension of the EPPM. Health Commun. 2013, 28, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swar, B.; Hameed, T.; Reychav, I. Information overload, psychological ill-being, and behavioral intention to continue online healthcare information search. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Stokols, D. Psychological and health outcomes of perceived information overload. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 737–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S. Exploring short-form video application addiction: Socio-technical and attachment perspectives. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 42, 101243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broder, H.L.; McGrath, C.; Cisneros, G.J. Questionnaire development: Face validity and item impact testing of the Child Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Harn, R.-W.; Ebrahim, H.; Aldana, J. International students’ social media use and social adjustment. First Monday 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, X. Pro-environmental behavior predicted by media exposure, SNS involvement, and cognitive and normative factors. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 954–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.; Li, X. Smartphones and psychological well-being in China: Examining direct and indirect relationships through social support and relationship satisfaction. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 54, 101469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pedraza, P.; Guzi, M.; Tijdens, K. Life Dissatisfaction and Anxiety in COVID-19 Pandemic; MUNI ECON Working Paper; Masaryk University, Faculty of Economics and Administration: Brno, Czech Republic, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Razali, F.; Talib, O.; Manaf, U.K.A.; Hassan, S.A. A measure of students motivation, attitude and parental influence towards interest in STEM career among Malaysian form four science stream student. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigre-Leirós, V.; Billieux, J.; Mohr, C.; Maurage, P.; King, D.L.; Schimmenti, A.; Flayelle, M. Binge-watching in times of COVID-19: A longitudinal examination of changes in affect and TV series consumption patterns during lockdown. Psychol. Pop. Media 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, N.; Sznitman, S.R. Too Much Information? Excessive Media Use, Maladaptive Coping, and Increases in Problematic Cannabis Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2022, 54, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleofas, J.V. Social media disorder during community quarantine: A mixed methods study among rural young college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2022, 40, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergun, G.; Alkan, A. The social media disorder and ostracism in adolescents:(OSTRACA-SM Study). Eurasian J. Med. 2020, 52, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, S.-J. Mediating effect of social support on the relationship between older adults’ use of social media and their quality-of-life. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 4590–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).