Abstract

The island of Mindoro forms the northeastern part of the Palawan Continental Terrane, a terrane that is considered to have formed at the southwestern margin of SE China and subsequently drifted into its present position as a consequence of the opening of the South China Sea. Using U-Pb age determinations of detrital zircon in sedimentary rocks and of current river sediments, this study aims to establish the relationships between the various geological units exposed on this island. The results indicate that some established units have left no trace in the current river sediments. On the other hand, some ages found in the age distributions of river sediments have no known source in the studied units. The data presented support the concept that the Northeast Mindoro Block is distinct from the Southwest Mindoro Block. Both blocks contain units that may be correlated with units exposed in northern and southern Palawan, and thus both appear to be related to the SE China margin of the South China block.

1. Introduction

The eastern margin of the Asian continent, including the islands fringing it to the east, is a complex puzzle of various crustal slivers (e.g., [1,2,3]). Their origins, their boundaries, and their relationships are a matter of intense debate. Even the relationship of major tectonic units like the Korean Peninsula and the island of Honshu (Japan) is contentious (e.g., [4,5]). In order to understand the evolution and assembly of the eastern margin of Asia, it is important to identify crustal blocks, to delineate their boundaries, and to determine their evolution.

The Philippine archipelago is one of the complex collages of various tectonic blocks located east of the Asian continent. It consists of two fundamental tectonic units, the Philippine Mobile Belt (PMB) in the east and the Palawan Continental Terrane (PCT) in the central western part. While it has long been recognized that the PMB is a collage of ophiolites, island arcs, and intervening sedimentary basins (see review in [6]], there has been little study on the overall composition of the PCT. It was recognized already for a long time that it is derived from the eastern margin of the Asian continent in SE China [7,8], and details of the origin of specific units have been worked out on the basis of studies of detrital zircon (e.g., [9] and references therein). However, it now appears that this terrane itself is composed of various blocks, the relationships of which were little studied [10,11].

The study of the U-Pb ages of detrital zircon extracted from river sediment and clastic sediments has proven to be a powerful tool to establish the relationships between disrupted terranes [9,12,13,14,15,16]. In Japan, even tiny slivers of only tens of meters in extension could be related to larger entities using this method [17]. For the PCT, there are several studies presenting U-Pb zircon age data for the island of Palawan that forms the northwestern part of the PCT, and these have been used to address the origin of Palawan, the temporal evolution of sediment sources, and the age of various geological units [9,14,16,18,19,20,21,22].

In contrast to the status of zircon work in Palawan, little work has been carried out on detrital zircon in Mindoro, which forms the northern part of the PCT [14,23]. The present study aims to partially redress the situation with the aim of evaluating proposed correlations and deciphering the nature and origin of the various blocks composing Mindoro and their relationship to other parts of the PCT. Specific questions investigated are

- ○

- Do the detrital zircon spectra in recent river sediments reflect the current knowledge of the geological units composing Mindoro?

- ○

- How are the major blocks composing Mindoro related to each other, i.e., are there systematic differences in the detrital zircon signatures between the Northeast Mindoro Block and the Southwest Mindoro Block?

- ○

- How similar are the provenances of Mindoro and Palawan? Are there specific units that can be correlated on the basis of their detrital zircon spectra? Does the data support the view that all blocks composing these islands originated from the same location on the southeastern margin of China?

- ○

- Is there evidence that supports a previous suggestion that the Northeast Mindoro Block was derived from the margin of the East China Sea Basin [10]?

In order to carry out an inventory of the island of Mindoro, zircons separated from 10 river sediment samples were dated, which is the first study of this kind in Mindoro. In addition, zircon from three sedimentary rocks, considered to be the main potential source rocks in northern Mindoro, was dated, adding to the data reported in previous studies for sedimentary rocks [14,23]. Data for other potential source rocks, i.e., intrusive quartzdiorite [24], rhyolite [25], and low-grade metamorphic rocks in central Mindoro [26] were published previously. Together with data available for other parts of the PCT [9,14,16,19,20,21,22,26], these data are used to evaluate several correlations proposed for Mindoro. This study illustrates the possibilities and problems of such studies.

2. Regional Geology

The Philippine Archipelago, located at the eastern margin of the South China Sea, is composed of two fundamentally different tectonic units: the Philippine Mobile Belt (PMB), forming the eastern part of the archipelago, and the Palawan Continental Terrane (PCT) that occupies the western central part of the archipelago (Figure 1). The PMB consists of amalgamated older and younger island arc sequences and obducted ophiolite complexes that came into existence probably in the early Cretaceous and later (e.g., [6]). The PCT, on the other hand, is a fragment of the Asian margin that drifted into its present position as a result of the opening of the South China Sea in the Oligocene (e.g., [7,8,9,23,27]).

Figure 1.

(Left): Geologic outline of the tectonic setting of the Palawan Continental terrane (PCT) relative to southeastern China and the Philippine Mobile Belt (PMB). (Right): Simplified geological map of Mindoro (compiled from various sources). NMB: Northeast Mindoro Block, SMB: Southwest Mindoro Block, EMB: East Mindoro Basin.

The timing of the collision of the PCT and the PMB is yet not well constrained. Yumul et al. (e.g., [28,29]) have repeatedly argued for an early Miocene collision since they interpret the structural evolution of the PMB as a result of that collision. Queano et al. [30], on the other hand, argued for a late Miocene collision based on paleomagnetic data. Walia et al. [31], combining several radiometric dating methods, suggested that collision at the eastern boundary of the PCT in Panay started at 14–15 Ma and was complete by 8 Ma.

The island of Mindoro forms the northeastern part of the PCT. It is composed of four major tectonic units (Figure 1): the Northeast Mindoro Block, the Southwest Mindoro Block, the Amnay Ophiolite Complex (e.g., [32,33]) separating the former, and the East Mindoro Basin, located east of the East Mindoro Fault [34]. It is generally agreed that the Southwest Mindoro Block is part of the PCT (e.g., [7,8,16]) whereas the tectonic affinity of the Northeast Mindoro Block has been a matter of intense discussion. Karig [35], Yumul et al. [32] and others argued that the Northeast Mindoro Block is part of the PMB, as it is located east of the suture zone delineated by the Amnay Ophiolite. Rangin et al. [11], Knittel and Daniels [36], and Knittel et al. [24] on the other hand, argued that this part of the island is likewise part of the PCT and was separated only temporarily from the main part of the PCT by a small ocean. Fu et al. [10] suggest that the Amnay Ophiolite is part of the eastern, now partially subducted crust of the East China Sea and that the Northeast Mindoro Block represents a part of its eastern margin. The southwestern block may have formed at the same margin, but further to the south.

The basement of the Northeast Mindoro Block is composed of metamorphic units of Carboniferous-Permian age [24,36], including mafic schists, marble, and granodiorite [37] that are collectively referred to as Mindoro Metamorphics. The next oldest unit is the Abra-de-Ilog Formation, exposed in a small strip extending from Abra de Ilog to the southwest, and it is considered to be of Cretaceous age [38]. This unit is composed mainly of pillow basalts, breccias, and tuffs with intercalations of red pelagic limestone between pillow units. However, as Canto et al. [39] and Cancepcion et al. [40] do not show this unit on their maps and stratigraphic columns, the status of this unit may be considered questionable. The main sedimentary unit of the Northeast Mindoro Block is the Lasala Formation (Figure 1), which is of Late Eocene to early Oligocene age [39,40]. This sedimentary sequence consists of interbedded medium-grained quartz arenite and dark gray shale with subordinate coralline limestones, conglomerates, and basalt flows [39,40]. Geochemical work [23,39,40] as well as age data for detrital zircon [14,23] have shown that the sediments were derived from a continental mass, most likely SE China. It is overlain by Pliocene to Early Pleistocene sandstone–siltstone sequences of the Balanga Formation. Both the Mindoro Metamorphics and the Lasala Formation are likely the most important sources of detrital zircon in river sediments.

The oldest unit exposed in the Southwest Mindoro Block is the Jurassic Mansalay Formation, which is well known for its Jurassic ammonites of late Middle to Late Jurassic age ([41] and references therein). The presence of these Jurassic sediments is commonly considered evidence that the Southwest Mindoro Block is part of the PCT, though temporal equivalents were not known from Palawan and the surrounding islands. Recently, however, detrital zircon of Jurassic age was discovered in the Bacuit Formation of Palawan, which was previously thought to be of Permian age [19]. The Mansalay Formation, consisting principally of sandstones, mudstones, and shales with minor limestones and pebbly conglomerate, is probably in fault contact with all other units [42]. The areal extent of the exposure is uncertain, as Marchadier and Rangin [43] consider parts of the mapped outcrop to consist of reworked Jurassic sediment. Therefore, the outcrop area shown in Figure 1 needs to be considered as preliminary. The next oldest sedimentary unit in this block is the Agbahag Conglomerate, which is probably of Middle Eocene age. The conglomerate is poorly sorted and is made up of pebbles of limestone, sandstone, mudstone, phyllite, chert, schist, basic volcanic rocks, and granitic rocks. This conglomerate is overlain by the Late Eocene to Early Oligocene Caguray Formation (Figure 1), consisting essentially of shale, mudstones, and sandstones with minor conglomerates and limestone. Some authors (e.g., [11]) have correlated the Caguray Formation with the Lasala Formation, which is of roughly identical age. The Caguray Formation is overlain by several limestone units, including the Pocanil Formation, composed of shale, siltstone, and sandstone interbedded with limestone, and the Punso Conglomerate, made up of pebbles of gneiss, schist, slate, quartzite, chert, basalt, gabbro, diorite, and limestone set in a siliceous and limy matrix.

Located between the Northeast Mindoro Block and the southwest Mindoro block is the Amnay Ophiolite (Figure 1). For this ophiolite, formation ages of 23–24 and ca. 33 Ma were reported on the basis of single-grain U-Pb dating of zircon [44]. This ophiolite consists of N-MORB and E-MORB [32,33].

3. Samples

Figure 2.

Sampling sites and catchment areas of the rivers sampled, and locations of the sediment samples. Sampling points P-06 and S-03 come from Yan et al. [14] and Z03-3 from Dimalanta et al. [23].

Table 1.

Summary of the results obtained in U-Pb dating of the detrital zircons.

3.1. River Sediment Samples

1–2 kg of recent river sediment was taken with an emphasis on fine-grained sediment. Samples from the north coast (Figure 2) are MIN-17A, MIN-19A, MIN-20A, and 21A. Their drainage areas are completely underlain by the Mindoro Metamorphics (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Two major rivers, the Pagbahan River (sample MIN-06A) and the Amnay River (sample MIN-9A), were sampled on the western coast where Highway 450 (Mindoro West Coastal Road) crosses these rivers to obtain insight into the inventory of large areas of northwestern Mindoro (Figure 2). The geology of the catchment areas is described in Section 6.3.

Two samples were taken from two rivers/creeks on the southeastern edge of the Northeast Mindoro Block: from the Magasawang Tubig River (MIN-32D) and an unnamed tributary of the Ibalo River that drains into the Magasawang Tubig River (MIN-35A). On the southeastern coast, samples were taken downstream of the Bongabong River (MIN-40A) and the Mansalay River (MIN-41A). The latter was collected at the bridge where the Calapan South Road crosses the river south of the municipality of Mansalay. The geological make-up of the catchment areas is described in the discussion.

3.2. Sandstone Samples

Three sandstone samples were collected from the Lasala Formation, which is considered to be an important source of zircon found in river sediments. MIN-12C and MIN-13A come from an isolated, narrow exposure along the northwestern tip of Mindoro (Figure 2, note that sampling locations are not correctly shown in Figure S2 of [19]) and it is thus not certain whether the sandstones exposed in the cliffs are really part of the Lasala Formation. Faure et al. [45], Canto et al. [39] and Perez et al. [33], however, consider them to be part of the Lasala Formation. Geochemical evidence is ambiguous: MIN-1D and MIN-13A have higher Zr/Ti and Nb/Ti ratios than samples analyzed by Concepcion et al. [40] (Supplementary Materials S1), which could be due to higher zircon contents in these samples. In terms of V/Cr, a plot which showed good discriminating power in studies of the Sanbagawa vs. Shimanto belt sediments ([46] and papers cited therein), MIN-1D and MIN-13A fall into the field defined by the Lasala samples [40].

Sample MIN-1D was collected from an outcrop that represents a mixture of various rock types, including ultramafic rocks, and therefore is probably a mélange. The outcrop may be part of the Abra-de-Ilog Formation or the Lasala Formation. Details on the petrography and geochemistry of these samples are provided in Supplementary Materials S1.

4. Methods

To extract zircons from the sediment samples, they were sieved, and components larger than 1 mm were discarded. Zircons were then separated using conventional shaking-table, magnetic, and heavy liquid separation methods. The sandstone samples were crushed, and components larger than 1 mm were discarded; the smaller components were further processed in the same way as the sediment samples.

U-Pb age determination of zircon was carried out in the Department of Geosciences of the National Taiwan University using an Agilent 7500s quadrupole ICP-MS instrument (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a Photon Machines 193 nm Analyte G2 excimer laser ablation system (Teledyne Photon Machines, Belgrade, MT, USA). The laser beam had a diameter of slightly less than 30 μm. The system was calibrated using the GJ-1 zircon, whereas zircon 91,500 and Australian Mud Tank Carbonatite zircon (MT) were used to control the quality of the data in 2009 (MIN-14B). In 2010, the MT standard was replaced by a zircon from Plešovice [47]. Average 207Pb-206Pb ages obtained were 1067.7 ± 4.2 Ma (n = 100) for 91,500 (recommended value 1065 Ma; [48]), 728.9 ± 4.6 Ma (n = 44) for Mud Tank zircon (recommended value 732 ± 5 Ma; [49]) and 337.3 ± 1.6 Ma (n = 76) for Plešovice (recommended value 337.1 ± 0.4 Ma; [47]]. Additional details of the analytical procedures are given in [50]. All U-Th-Pb isotope ratios were calculated using the GLITTER 4.0 (GEMOC) software. Common lead was corrected using the common lead correction function proposed by Andersen [51]. For zircons younger than 1 Ga, 206Pb/238U ages are considered due to the smaller statistical error compared to 207Pb/206Pb ages, which is due to the slow growth of 207Pb in young zircons, whereas 207Pb/206Pb ages, which are independent of the quality of the determination of the U/Pb ratio, were preferred for zircons older than 1 Ga. We consider zircons as concordant if the error ellipse falls on the concordia. We also accepted analyses plotting off the concordia, if the degree of discordance (calculated as [1 − (206Pb/238Uage)/(207Pb/206Pbage)] ∗ 100 [%]) was less than 15%. The weighted mean U-Pb ages were calculated, and probability density plots were produced using Isoplot v. 3.0 [52]. For some plots, the Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) [53] was used, as these plots more clearly exhibit the main features of the patterns.

All zircons were imaged by cathodoluminescence (CL) at Academia Sinica, Taipei. A thermal emission, low-vacuum type scanning electron microscope (JEOL W-LVSEM: JSM-6360LV; JEOL, Akishima, Japan), equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer and a cathodoluminescence (CL) image detector (Gatan mini-CL; Gatan, Pleasanton, CA, USA) was used. On the basis of the CL pictures and examination under reflected light, care was taken to avoid inclusions during analysis.

5. Results

The results of the age determinations are summarized in Table 1, and the corresponding data are provided as Supplementary Data Files T1 and T2. Ages younger than 1 Ga are reported as 206Pb/238U, whereas ages older than 1 Ga are reported as 207Pb/206Pb ages in the text. Selected CL pictures are provided as Supplementary Material F1 that illustrates several aspects of the zircons: most ca. 1.86 Ga zircons are very dark in CL (e.g., MIN-41A, analyses 27 and 35 in F1), though some are bright (e.g., MIN-12B, analyses 74 and 75 in F1). Where cores and rims were analyzed, the former may be older than the rims (e.g., MIN-13A, analyses 61 and 62 in F1) or may have about the same age (e.g., MIN-13A, analyses 27 and 29 in F1; note that these two analyses are identical with 2σ errors).

5.1. River Sediments

For samples from the small rivers draining the metamorphic complex to the north (MIN-17A, MIN-19A, MIN-20A, and MIN-21), altogether 180 analyses were carried out, of which 6 were rejected due to discordance or large errors. Most grains (143 out of 174 = 82%) fall into the range 237–276 Ma, with an average of ca. 255 Ma. In some samples, a minor peak is indicated at ca. 243 Ma, which would explain why the peak is rather broad. Th/U ratios are 0.12–1.51, with the exception of two 238 Ma old grains that have Th/U of 0.03 and 2.9, respectively. Th/U ratios > 0.1 are considered to indicate a magmatic origin of zircon. The next abundant group comprises 8 grains in the range 81–92 Ma and includes two core/rim analysis pairs. Th/U is 0.27–1.69.

Ages represented by two or more grains only are 103–105 Ma (n = 2), 121–125 Ma (n = 2), 168–180 Ma (n = 3), and 352–390 Ma (n = 5) (2σ errors).

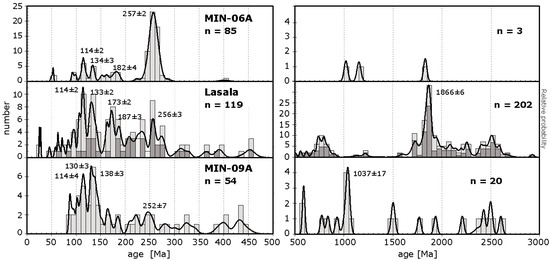

Samples from the Pagbahan and Amnay rivers show much more diverse age spectra than those from the northeastern coast. For the Pagbahan River sediment (MIN-06), all but three grains gave 206Pb/238U ages of less than 402 Ma. The older grains gave concordant 207Pb/206Pb ages of 1019 ± 38 Ma, 1152 ± 40 Ma, and 1828 ± 17 Ma. Th/U ratios lie between 0.29 and 1.31. Among the Phanerozoic zircons, those with ages between 242 Ma and 272 Ma predominate (53 grains = 60%), and an average age of 257 ± 2 Ma can be calculated with a relatively low MSWD value of 1.4 (Figure 3). Three more significant age clusters occur at 114 ± 2 Ma (7 grains, MSWD = 0.8; Th/U = 0.39–0.91), 134 ± 3 Ma (5 grains, MSWD = 0.5; Th/U = 0.43–0.81), and at 182 ± 4 Ma (5 grains, MSWD = 1.1; Th/U = 0.29–0.71). Only 14 grains have ages scattered outside these ranges. The youngest grains have ages of 50 ± 4 and 53 ± 2 Ma.

Figure 3.

Probability density plot for detrital zircon ages for sediment samples from the Pagbahan River (MIN-6A) and the Amnay River (MIN-09A) in comparison to the corresponding plot for the Lasala sediments (this study, [14,23]; dark colored data is data for MIN-12-C and MIN-13A.

In the Amnay River sediment, the youngest cluster occurs at 105 ± 6 Ma (4 analyses, MSWD = 2.0) (Figure 3). Additional clusters occur at 116 ± 2 Ma (6 analyses, MSWD = 1.0), 130 ± 3 Ma (n = 6, MSWD = 0.28), and 138 ± 3 Ma cluster (n = 6, MSWD = 0.59). A relatively large number of analyses gave 207Pb/206Pb ages >1Ga (17 analyses = 21%). For these ages, no distinct clustering is discernible (not considering “clusters” of two grains) with the exception of a possible cluster at 1035 ± 18 (5 grains, MSWD = 0.61), which is present only if, also for zircons with 206Pb/238U ages greater than 900 Ma, the 207Pb/206Pb ages are preferred (Figure 3).

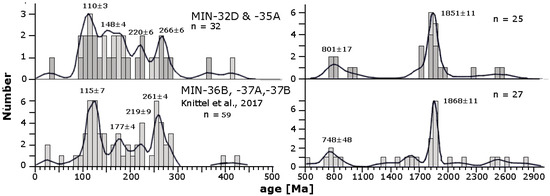

Only 16 grains could be analyzed for MIN-32D from the Magasawang Tubig River due to a problem with the analytical equipment. A peak is indicated at ca. 180 Ma and at 1851 ± 18 Ma (Figure 4). For sample MIN-35A, three discordant grains define a discordia with an upper intercept at 929 ± 71 Ma and a lower intercept at 177 ± 52 Ma that would match the indicated peak at 180 Ma of sample MIN-32D. Zircon ages of less than 500 Ma show little clustering, though three grains each fall into the narrow ranges of 108–119 Ma and 124–134 Ma. For older zircons, a peak is indicated at 804 ± 20 Ma, and there is a clear peak at 1851 ± 11 Ma. In Figure 4, these data are combined.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the KDE age spectra of the zircons from the Magasawang Tubig River (light gray boxes) and tributary (dark gray boxes) (upper panel) and those from the low-grade metamorphics exposed north of the Ogos Ultramafic Complex (lower panel, data from [26]).

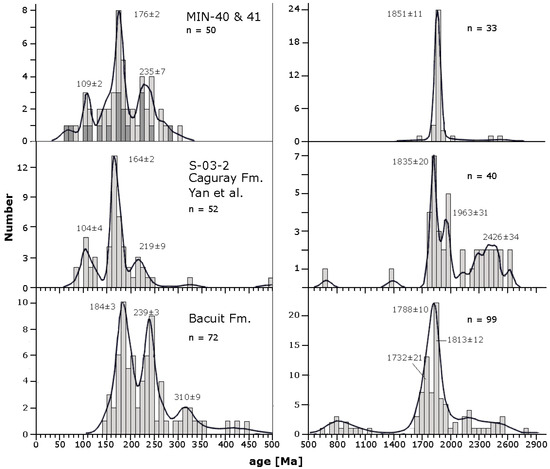

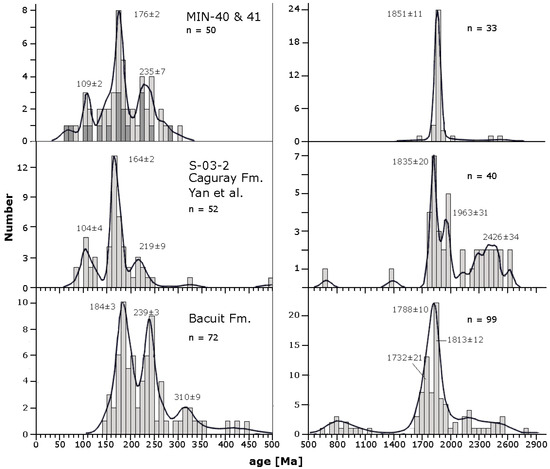

Of the accepted 60 analyses for sample MIN-41A, 7 are younger than the Jurassic sediments (Callovian–Oxfordian, ca. 165–150 Ma) of the Mansalay Formation, which are considered to be the main source of the Mansalay River sediment. The youngest grain was dated at 89 ± 2 Ma. 26 grains have early Mesozoic and late Paleozoic ages that are compatible with the (hypothetical) derivation from Jurassic sediments, and 27 grains have Paleoproterozoic ages of 1.84–2.54 Ga (=45%).

Most grains can be ascribed to three Mesozoic ‘events’ in the late Upper Jurassic 152 ± 8 Ma (n = 6; MSWD = 4.9), the late Lower Jurassic 177 ± 3 Ma (n = 7; MSWD = 0.93), and early Upper Triassic 238 ± 8 Ma (n = 6; MSWD = 2.1). Of the Paleoproterozoic ages, twenty-two grains have an average age of 1.863 ± 7 Ma (MSWD 0.42).

Of the concordant ages obtained for the Bongabong River sediment, 17 fall into the range 64–284 Ma and 6 ages into the range 1.86–2.41 Ga. 5 of the Precambrian grains have an average age of 1868 ± 17 Ma (MSWD = 0.23). Due to the small number of analyses, no real clustering is observed, but overall, the pattern is similar to that of the sample from the Mansalay River (Figure 5), with 5 grains with an average age of 177 ± 9 Ma.

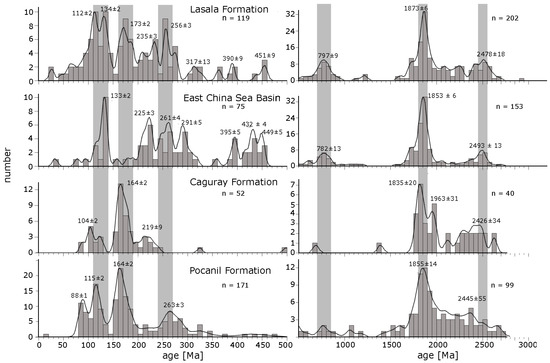

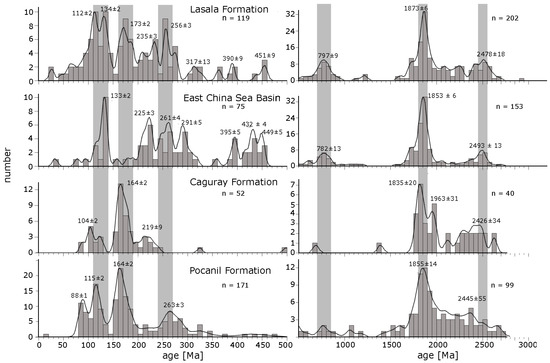

5.2. Sediments of the Lasala Formation

Sampling point coordinates and major results for sandstone samples from the Lasala Formation are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Coordinates of sampling points and major results for sandstone samples from the Lasala Formation.

In sample MIN-1D, the youngest grains have ages of 58 ± 4 Ma, 63 ± 2 Ma, and 75 ± 4 Ma. Peaks in the age pattern occur at 110 Ma, 141 Ma, and 1867 ± 13 Ma (Figure 6). 12 grains scatter between 391 and 913 Ma without forming clusters. Th/U ratios range from 0.17 to 1.74 except for two grains with Th/U = 0.02 dated at 196 and 217 Ma.

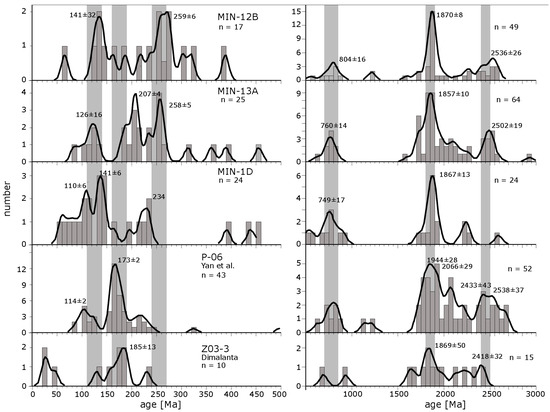

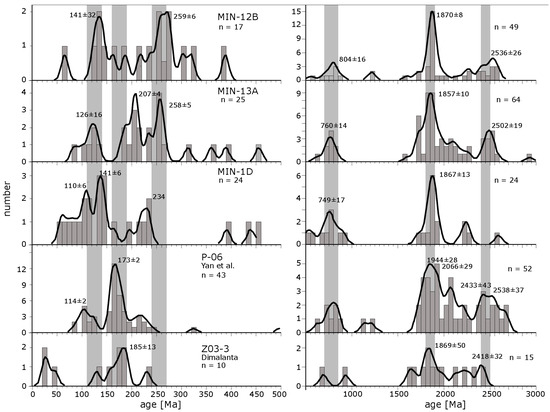

In sample MIN-12B, the youngest zircon has an age of 66 ± 4 Ma. In total, 25 gains have an age of <1 Ga, and 41 of >1 Ga. Small clusters were found at 141 Ma, 259 Ma, and 804 Ma, and 17 grains form a prominent cluster at 1870 ± 8 Ma. Six grains define a peak at 2529 ± 27. Six discordant grains define a discordia with an upper intercept at 2275 ± 29 Ma. The Th/U ratios scatter between 0.10 and 2.79.

For sample MIN-13A, the youngest age is 84 ± 3 Ma. No useful YC1σ age can be calculated due to insufficient clustering of the ages. Only 34 ages are <1 Ga and 55 >1 Ga. Clusters are found at 207 Ma and 258 Ma, at 1857 and 2508 Ma.

Figure 5.

Kernel density estimation (KDE) spectra and histograms of the Mansalay and Bongabong River (dark gray) samples. Middle panel: plot for the Caguray sample [14]. Lower panel: plot for the Bacuit Formation in Palawan [19].

6. Discussion

6.1. Sediment Samples

Previously, U-Pb ages for detrital zircon were reported for two samples of the Lasala Formation [14,23]. The new data reported here for three further samples were made available to other authors who have already used it for comparisons [16,19]. Figure 6 shows that the individual samples exhibit quite variable spectra. In multidimensional scaling (MDS) plots [54], samples MIN-12C and MIN-13A from the NW coast of Mindoro plot close to each other ([19], Figure 15 and Figure 16), whereas MIN-1D and P-06 [14] also plot close to each other. Samples MIN-12B and MIN-13A have significant clusters at ca. 250 Ma that apparently are inherited from Mindoro Metamorphics [24]. This peak is only poorly developed in the other samples that come from roughly the same area. This observation illustrates a general problem of this kind of study, i.e., the peaks in summary KDE curves like the one shown in Figure 3 and Figure 7 may be produced by only a small subset of the samples.

The main common features of all Lasala age spectra are some zircons in the range 700–850 Ma and a significant peak at 1.86 Ga. All other peaks shown in Figure 7 are lacking in one sample or the other. The number of Proterozoic grains in all samples is larger than that of Phanerozoic grains.

It is further noteworthy that the sample S-03-3 of the Caguray Formation [14] multidimensional scaling (MDS) plots do not plot in the same cluster as the Lasala samples ([19], Figure 15 and Figure 16). However, given the variability of the individual samples of the Lasala Formation discussed above, it is very difficult to judge the similarity/dissimilarity of these units on the basis of a single sample.

6.2. Northeastern Coast

The creeks on the northern coast drain the various units of the Mindoro Metamorphics. As noted in the results section, 82% of the zircon ages obtained for creeks draining the northeastern part of Mindoro fall into the range 237–276 Ma, with a peak at ca. 255, which roughly coincides with the age of a single sample of the Camarong Gneiss of 251.0 ± 2.6 Ma [24]. As argued by Knittel et al. [24], these zircons do not date a single event but an igneous episode that led to the formation of the protoliths of the Camarong Gneiss.

The 6 grains having ages of 81–92 Ma are probably derived from rhyolitic intrusions, one of which was dated at 82.9 ± 0.9 Ma [25]. There are 15 grains dated at 103 to 232 Ma that do not exhibit any visible clustering. Their origin, therefore, is not known. Five grains were dated at 352–390 Ma, for which an average age of 368 ± 19 Ma (Late Devonian) can be calculated. It might be speculated that these represent the age of the mafic igneous rocks that form a large part of the Mindoro Metamorphics. This would be compatible with the Late Paleozoic age of marble inferred on the basis of its Sr isotope composition [36]. Only two grains have Precambrian ages, which suggests that the sediments of the Lasala Formation do not significantly contribute to the zircon inventory of the creeks draining the northeastern coastal area, as in the Lasala sediments, zircon of Precambrian age is abundant (see above).

6.3. West Coast

For the northwestern coast, data is provided for samples from two major rivers draining northwestern Mindoro, the Pagbahan River and the Amnay River.

The catchment area of the Pagbahan River in its upper reaches is underlain by the Mindoro Metamorphics, and in its lower reaches by the sediments of the Lasala Formation and a small part of the Amnay Ophiolite (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The age spectrum of zircon from river sediment from the Pagbahan River is dominated by 53 grains (60%) dated at 237–272 Ma, identical to the bulk of the grains found in the creeks draining to the north. These grains are likewise considered to be derived from the Camarong Gneiss. Other noteworthy peaks occur at 114.0 ± 2.0 Ma and 133.6 ± 2.6 Ma. These ages are not represented in the creeks draining the northeastern coastal areas but are observed in the Lasala sediments (Figure 3 and Figure 6). However, the Pagbahan River age spectrum is not simply a mixture of grains derived from the Camorong Gneiss and the Lasala Formation, as there are also distinct differences relative to the spectra of the samples from the Lasala Formation. The latter contains significant amounts of Neoproterozoic zircon in the range of ca. 600–750 Ma that are not found in the Pagbahan River sediment. Furthermore, only three grains of Meso- to Paleoproterozoic age were found in the river sediment, whereas Paleoproterozoic zircons constitute a significant portion (30–62%) of the zircon inventory of the Lasala Formation (Figure 3 and Figure 6). It thus appears possible that another source may dilute the contribution of the Lasala Formation, but at the present stage of study, no possible candidate is known. Alternatively, the Paleoproterozoic may have become less stable during transport due to radiation damage. Another possibility is that the samples analyzed for the Lasala Formation do not represent the whole spectrum of patterns realized in the Lasala Formation.

Figure 6.

Probability density curves and histograms of samples of the Lasala Formation. Patterns obtained in this study (MIN-1D, MIN-12C, and MIN-13A) are compared with patterns obtained by Dimalanta et al. [23] and Yan et al. [14].

A noteworthy feature of the Pagbahan River spectrum is the lack of zircon in the age range 30–40 Ma, the supposed age of the Pagbahan Granodiorite that is considered to be exposed in the drainage area of the Pagbahan River, though only in small outcrops [55]. Likewise, no zircons with the formation age of the Amnay Ophiolite ([23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] Ma; [44]) were found.

The Amnay River drains areas underlain by the Lasala Formation and by mafic and ultramafic rocks of the Mangyan and the Amnay ophiolites. Its uppermost portion reaches the exposure of the Camorong Gneiss (Figure 1 and Figure 2) but there is no significant peak at ca. 250–270 Ma. The major peaks at 114 ± 4 Ma, 130 ± 3 Ma and 138 ± 3 Ma have corresponding peaks in the Lasala samples MIN-1D and MIN-12B. However, like the Pagbahan River sample, the Amnay River sample lacks Paleoproterozoic zircons, in particular the peak at 1.86 Ga. As in the Pagbahan River sediment, no zircons with the age of the Amnay ophiolite were found.

6.4. Central Eastern Mindoro

The drainage area of the Magasawang Tubig River is largely underlain by the Lasala Formation (upstream), the Ogos Ultramafic Complex, and a low-grade young metamorphic complex [26]. The unnamed tributary of the Ibalo River drains the Ogos Ultramafic Complex and the low-grade metamorphics. The zircons found in these rivers (MIN-32D and MIN-35A) overall exhibit patterns similar to those from the low-grade metamorphics exposed north of the Ogos Ultramafic Complex (Figure 4) studied by Knittel et al. [26]. Unfortunately, the number of analyzed zircons is small in both cases, and therefore, a more detailed comparison is not possible.

6.5. Southeastern Mindoro

The samples taken from the Bongabong River and the Mansalay River are the only samples from the southwestern block of Mindoro in this study. The Bongabong River drains large exposures of the Caguray Formation and exposures of ultramafic complexes. Sample MIN-40A was collected where the Calapan South Road crosses the Bongabong River.

Sample MIN-41A was collected south of the municipality of Mansalay, and, based on the mapping of Sarewitz and Karig [42], a large part of the catchment area is underlain by the Jurassic Mansalay Formation, which is of Oxfordian age (ca. 165–150 Ma) [41,56]. Marchadier and Rangin [43], however, noted that the Mansalay Formation is difficult to differentiate from the overlying Eocene to Oligocene Carugay Formation, and, in all likelihood does not occur with the great geographic extent proposed in earlier studies [42,55]. The zircons of sample MIN-41A, therefore, may constitute a mixture of zircons derived from the Mansalay and the Caguray Formations.

Yokoyama et al. [57] determined monazite total U-Pb ages for a sample of the Mansalay Formation and reported peaks at 177 ± 18, 231 ± 27, and 1881 ± 43 Ma in the age distribution. These are identical to the peaks at 176 ± 2, 235 ± 6, and 1851 ± 11 Ma observed in our sediment sample, suggesting that the zircons that define these peaks are derived from the Mansalay Formation. Further similarities are the lack of monazite and zircon ages, respectively, in the range 324 Ma–1.64 Ga and the abundance of monazites and zircons, respectively, older than 1 Ga (50 and 40%, respectively). The absence of a peak at 153 ± 7 Ma in the monazite age pattern of Yokoyama et al. [57] may indicate that their sample comes from an older part of the Mansalay Formation, as this age is close to the uppermost age boundary reported for the Mansalay Formation [41,56].

The peak at 177 ± 3 Ma is almost unique in Mindoro. A small peak at 182 ± 4 Ma in the sample MIN-6A and at 173 ± 2 in the Lasala sample of Yan et al. may be the only equivalents. In contrast, peaks at ca. 177 Ma are found in a number of samples from Palawan, e.g., in three of the four samples of the Middle to Late Jurassic samples of the Bacuit Formation ([19], see Figure 5) and in 6 of the eight samples of the Late Cretaceous Guinlo Formation [16,22]. A detailed comparison between the spectra of samples MIN-40A and MIN-41A with that of the Bacuit Formation shows that the main peaks at 176–184 and at 235–239 are present in both spectra, but the 1.86 Ga peak is shifted to 1.79 Ga in the Bacuit spectra, and the peak at ca. 800 Ma is altogether lacking in MIN-40A and MIN-41A. The Upper Triassic peak at ca. 230 Ma is shifted to a lower age compared to the mid-Mesozoic peak at 250–270 Ma seen in northeastern Mindoro. Thus, there is only ambiguous evidence for a close relationship between the southwestern block of Mindoro and northern Palawan.

Compared to the Caguray sample, the Mansalay and Bongabong River patterns show a shift in the Triassic peak from ca. 220 to 235 Ma and a paucity of grains in the age range from ca. 2.2 Ga to 2.6 Ga. The Lasala sediments differ from the Mansalay and Bongabong River patterns in particular, in the period between 304 Ma and 1.66 Ga, where there are no zircons falling into this age range, while Lasala sediments contain moderate amounts of zircon in the age range 700–800 Ma. It is therefore tentatively concluded that the Lasala Formation and the Caguray Formation are not the same unit. This is also supported by the distance of the Caguray sample to the Lasala samples in the MDS plots ([19], Figure 15 and Figure 16). Whether or not there is a distinct input from the Mansalay Formation into the Caguray Formation must await further studies.

6.6. Relationship Between the Northeast Mindoro Block and the Southwest Mindoro Block

There have been numerous attempts to elucidate the relationship between the Northeast Mindoro Block and the Southwest Mindoro Block. Initially, the prevailing opinion was that the Northeast Block is part of the PMB (e.g., [29,32,35]). This conclusion is, however, incompatible with the Carboniferous to Permian age of the Mindoro Metamorphics [24,36]. Fu et al. [10] recently proposed a new interpretation of the relationships between the Northeast and Southwest blocks of Mindoro, and their relationship to Palawan. These authors suggest that the Mindoro blocks are derived from the eastern margin of the East China Sea Basin and formed at some distance from each other. They based this proposal on the similarity of the zircon spectra from the East China Sea Basin and the Lasala Formation in a multidimensional scaling plot and a cumulative age distribution plot ([10], Figure 5a,b). In particular, the Lasala samples MIN12C and MIN13A plot furthest from the samples from Palawan and the South China coast multidimensional scaling plots of Cao et al. [19]. Fu et al. [10] also pointed out that zircon age spectra in both areas—in contrast to samples from the northeastern margin of the South China Sea—are characterized by a large number of peaks and a high abundance of zircon of Precambrian age.

A close examination of the patterns shows great similarities, i.e., peaks at 130–150 Ma, 240–260 Ma, 700–850 Ma, 1.80–1.90 Ga, and 2.45–2.55 Ga (Figure 7). A major difference, however, is the almost complete lack of zircon in the range 150–190 Ma in the East China Sea sediments. This lack of Middle to Late Jurassic zircon is also seen in the northern rivers draining SE China, i.e., the Gan River [58], the Ou River [59], and the Min River [60,61]. Prominent Late Jurassic peaks occur in the zircon age spectra of the rivers south of the Min River, i.e., the Juilong River [60], the North River [59], and the Pearl River [61]. It thus appears probable that the sediments exposed in Mindoro were not deposited at the margin of the East China Sea Basin but close to the present coast of the southern part of SE China. In this respect, they are similar to the sediments studied in Palawan that are considered to be derived from the eastern margin of the South China Sea, as interpreted by many authors, including Shao et al. [16], Cao et al. [19] and Chen et al. [9].

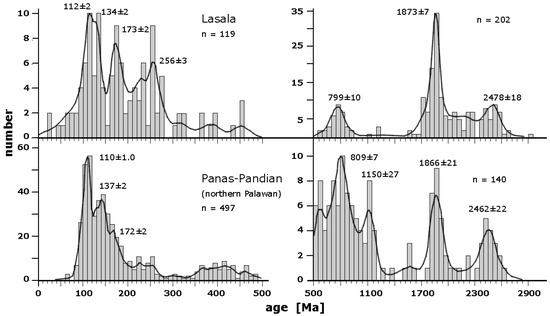

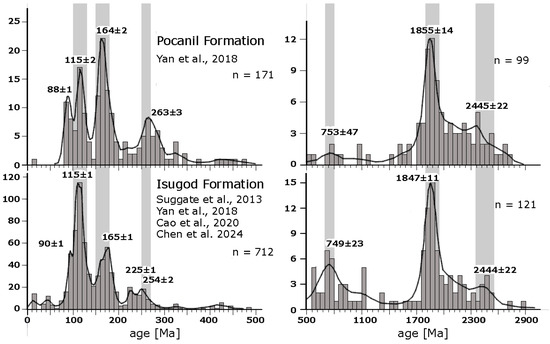

If the Northeast Mindoro Block and the Southwest Mindoro Block were derived from different areas along the eastern margin of the East China Sea Basin, it could be expected that the age patterns from these blocks differ from each other. There is little data for the southwestern block; Yan et al. [14] presented data for one sample of the Caguray Formation and for three samples of the mid-Miocene Pocanil Fm. As shown in Figure 7, there are indeed some differences; compared to the Lasala age spectra, the Caguray Formation sample contains only one grain in the range 310–450 Ma and only a single grain in the range 700–850 Ma, whereas the Lasala spectrum exhibits distinctive peaks in these age ranges. However, it must be kept in mind that data is available only for a single Caguray sample. The Pocail samples exhibit a zircon age spectrum that is relatively similar to that of the Lasala samples. This may indicate that the Pocanil samples, possibly contain contributions from the older Lasala Formation. In detail, it is noted that in the Pocanil samples about two-thirds of the zircons are younger than 500 Ma, whereas in the Lasala, the opposite is true. In addition, the Pocanil samples lack a significant zircon population in the range 390–460 Ma.

Figure 7.

Comparison of age spectra of detrital zircon from the Lasala Formation (dark shading are samples MIN-12B and -13, this work), the East China Sea Basin [10], the Pocanil Formation [14], and Mansalay and Bongabong Rivers (this work).

6.7. Relationships Between Palawan and Mindoro

A question that has as yet never been really discussed is the relationship between Mindoro and Palawan. While it is generally agreed that southwestern Mindoro is part of the PCT, and after it has been established that northeastern Mindoro is also part of the PCT [24,25,36], it is noteworthy that the stratigraphic columns of Mindoro and Palawan are quite different (e.g., [19], Figure 7). No Late Cretaceous strata are known from Mindoro that may correspond to the Baoyan Formation, the Concepcion Phyllite, and the Caramay Schist (i.e., the Barton Group sediments) exposed in the southern part of northern Palawan. Until recently, no equivalent to the Jurassic Mansalay Formation was known, but recently it was discovered that the Bacuit Formation exposed in northern Palawan is of about the same age as the Mansalay Formation exposed in southern Mindoro [19]. The age spectrum of the Bacuit samples resembles that of our proxy for the Mansalay Formation, i.e., those of the river sediments MIN-40A and MIN-41A. But a notable feature of the Bacuit spectrum is the peak at 1.71 Ga. Such zircons are very rare in the PCT and also in the sediments of the rivers draining SE China [58,59,60,61], where zircons in the range 1675–1759 Ma were found only occasionally, except for one sample from the Min River that contains 10 grains (out of 127 concordant analyses) in this age range.

There are no clastic sediments of Eocene/Oligocene age in northern Palawan that could correspond to the Caguray and Lasala Formations, but in southern Palawan, the Panas and Pandian Formations are of about the same age (Figure 8). Their age spectra show similarities (Figure 8) in terms of age peaks, but the Lasala samples contain a much greater proportion of Precambrian grains, and Chen et al. [9] studied the Panas–Pandian Formation in detail and concluded that they were deposited at 48–33 Ma and—based on a comparison between the detrital zircon inventories of these formations and sediments on the southeastern margin of southeast China—concluded that they were deposited in the area of the Pearl River Mouth Basin.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the KDEs of the Lasala Formation (this study, [14,23]) and the Panas–Pandian Formation of Palawan [9,16].

The Pocanil Formation could have its counterpart in the Isugod Formation of southern Palawan, as both units are of about the same age and have very similar age spectra of detrital zircon (Figure 9), though the relationships between the number of Precambrian and Phanerozoic grains are different. In the Pocanil Formation, Phanerozoic grains make up 63%, and in the Isugod Formation, 85%. This supports the suggestions that the Southwest Mindoro Block and southern Palawan are parts of the PCT.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the KDEs of the Pocanil Formation [14] and the Isugod Formation of Palawan [14,18,19,21].

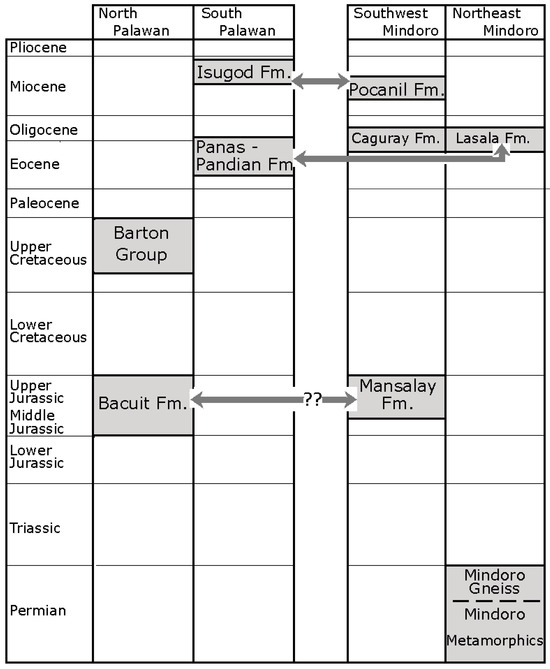

A summary of the possible relationships is shown in Figure 10. This illustrates that the sedimentary units of the Northeast and Southwest Mindoro blocks can be correlated with units from northern and southern Palawan. However, no coherent correlation is seen between the different blocks: the Lasala Formation of the Northeast Mindoro Block and the Pocanil Formation of the Southwest Mindoro Block are both best correlated with the Panas–Pandian and the Isugod Formations of southern Palawan. On the other hand, the Mansalay Formation of the Southwest Mindoro Block may be correlated to the Bacuit Formation of northern Palawan. The possible correlation of the Caguray Formation—if there is any—is not clear and must await further study. It thus appears that all four entities, i.e., the Northeast and Southwest Mindoro blocks and southern and northern Palawan, formed in close proximity to each other and were disrupted and displaced relative to each other only during the opening of the South China Sea and/or during the collision with the PCT.

Figure 10.

Correlations of sedimentary sequences from Mindoro and Palawan based on the spectra of detrital zircon.

7. Conclusions

- Zircons in the rivers/creeks draining the northeastern coast of Mindoro are largely derived from Late Permian plutonic rocks that intrude the metamorphic basement. In addition, some zircons reflect the minor rhyolite volcanism of Cretaceous age.

- The Pagbahan and Amnay Rivers that drain to the west coast likewise contain zircon derived from the Permian intrusives but also contain zircon that might be derived from the Late Eocene to Early Oligocene Lasala sediments. However, the zircon spectra of these rivers are not simply mixtures of zircon derived from the Lasala sediments and the Permian intrusives, as they contain only a few Precambrian zircons that are abundant in the Lasala sediments.

- Zircon from rivers in central-eastern Mindoro is largely derived from low-grade metamorphic rocks that are younger than the Mindoro Metamorphic Rocks proper [26].

- Sediments from rivers draining to the southeast of Mindoro represent the Southeast Mindoro Block. They apparently contain zircon derived from the Jurassic Mansalay Formation.

- The sedimentary units exposed on the northeast and southwest Mindoro blocks appear to be correlated with units from southern and northern Palawan. It thus appears that all blocks were formed in the same general area. At the current state of knowledge, deposits of the Northeast and Southwest Mindoro blocks were not deposited in the same area. A derivation of the Northeast Mindoro Block from the East China Sea Basin is unlikely.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/geosciences16010017/s1, S1: Data for sandstone samples; F1: Cathodoluminiscene (CL) pictures of zircon analyzed in this study; T1: U-Pb data for detrital zircons from river sediments; T2: U-Pb data for detrital zircons from the Lasala Formation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.K. and T.F.Y.; investigation, U.K., H.-L.C., M.W. and T.F.Y.; resources, T.F.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, U.K.; writing—review and editing, U.K.; funding acquisition, T.F.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

National Science Council, Taiwan, R.O.C. (NSC grant 97-2811-M-002-040) to UK; and NSC 97-2116-M-002-011 to TFY.

Data Availability Statement

All data produced in this study is contained in the Supplementary Files.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Karlo Queano, Leo T. Armarda, the late Rudolfo A. Tamayo, and Anna P. B. Canto for guidance and company in the field and Sun-Lin Chung for generous access to laboratory facilities. UK gratefully acknowledges a grant from the National Science Council, Taiwan, R.O.C. (NSC grant 97-2811-M-002-040), which permitted him to carry out this research at the National Taiwan University. Additional support came from a grant NSC 97-2116-M-002-011 to Yang. Comments by four reviewers were helpful to address several points more clearly. We thank our assistant editor for her unwavering support and patience.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Fletcher, C.J.; Chan, L.S.; Sewell, R.J.; Diarmad, S.; Campbell, G.; Davis, D.W.; Zhu, J. Basement heterogeneity in the Cathaysia crustal block, southeast China. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spéc. Publ. 2004, 226, 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe, I. Gondwana dispersion and Asian accretion: Tectonic and palaeogeographic evolution of eastern Tethys. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013, 66, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charvet, J. Late Paleozoic–Mesozoic tectonic evolution of SW Japan: A review–Reappraisal of the accretionary orogeny and revalidation of the collisional model. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013, 72, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, K.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Kim, H.; Cho, M.; Hidaka, H.; Terada, K. A U-Pb geochronological study of migmatitic gneiss in the Busan gneiss complex, Gyeonggi massif, Korea. Geosci. J. 2009, 13, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.W.; Kusky, T. The Late Permian to Triassic Hongseong-Odesan collision belt in South Korea, and its tectonic correlation with China and Japan. Int. Geol. Rev. 2007, 49, 636–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumul, G.P.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Maglambayan, V.; Marquez, E. Tectonic setting of a composite terrane: A review of the Philippine island arc system. Geosci. J. 2008, 12, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W. Tectonics of the Indonesian Region; Professional Paper; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1979; Volume 1078.

- Holloway, N.H. North Palawan Block, Philippines—Its relation to Asian Mainland and role in the evolution of South China Sea. Bull. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. 1982, 66, 1355–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.-H.; Yan, Y.; Carter, A.; Huang, C.-Y.; Yumul, G.P.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Gabo-Ratio, J.A.S.; Wang, M.-H.; Chen, D.; Shan, Y. Stratigraphy and provenance of the Paleogene syn-rift sediments in central-southern Palawan: Paleogeographic significance for the South China Margin. Tectonics 2021, 40, e2021TC006753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Gao, S.; Zhu, W. The Northeast Mindoro block is the conjugate margin of the southern East China Sea Basin: Insight from detrital zircon data. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 162, 106710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangin, C.; Stephan, J.F.; Muller, C. Middle Oligocene oceanic crust of the South China Sea jammed into Mindoro collision zone, Philippines. Geology 1985, 13, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Yang, S.; Li, C.; Su, N.; Bi, L.; Chang, Y.-P.; Chang, S.-C. Detrital zircon geochronology of river sands from Taiwan: Implications for sedimentary provenance of Taiwan and its source link with the east China mainland. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2017, 164, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.; Yan, Y.; Huang, C.-Y.; Santosh, M.; Shan, Y.-H.; Chen, W.; Yu, M.; Qian, K. Topographic architecture and drainage reorganization in Southeast China: Zircon U-Pb chronology and Hf isotope evidence from Taiwan. Gondwana Res. 2016, 36, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Yao, D.; Tian, Z.; Huang, C.; Chen, W.; Santosh, M.; Yumul, G.P., Jr.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Li, Z. Zircon U-Pb chronology and Hf isotope from the Palawan-Mindoro Block, Philippines: Implication to provenance and tectonic evolution of the South China Sea. Tectonics 2018, 37, 1063–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Takeuchi, M. Sedimentary history and provenance analysis of the Sanbagawa Belt in eastern Kii Peninsula, Southwest Japan, based on detrital zircon U–Pb ages. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2020, 196, 104342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Cao, L.; Qiao, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; van Hinsbergen, D.J. Cretaceous–Eocene provenance connections between the Palawan Continental Terrane and the northern South China Sea margin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2017, 477, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, K.; Hayasaka, Y.; Das, K.; Shibata, T.; Kimura, K. Zircon U–Pb geochronology of “Sashu mylonite”, eastern extension of Higo Plutono-metamorphic Complex, Southwest Japan: Implication for regional tectonic evolution. Isl. Arc 2020, 29, e12350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-H.; Yan, Y.; Carter, A.; Clift, P.D.; Huang, C.-Y.; Yumul, G.P.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Gabo-Ratio, J.A.S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, M.-H. Evolution of arc-continent collision in the southeastern margin of the South China Sea: Insight from the Isugod Basin in central-southern Palawan. Tectonics 2024, 43, e2023TC008078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Shao, L.; Qiao, P.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, X. Formation and paleogeographic evolution of the Palawan continental terrane along the Southeast Asian margin revealed by detrital fingerprints. GSA Bull. 2020, 133, 1167–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, M.; Knittel, U.; Suzuki, S.; Chung, S.-L.; Pena, R.E.; Yang, T.F. No Paleozoic metamorphics in Palawan (the Philippines)? Evidence from single grain U–Pb dating of detrital zircons. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 52, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suggate, S.M.; Cottam, M.A.; Hall, R.; Sevastjanova, I.; Forster, M.A.; White, L.T.; Armstrong, R.A.; Carter, A.; Mojares, E. South China continental margin signature for sandstones and granites from Palawan, Philippines. Gondwana Res. 2013, 26, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrones, J.T.; Tani, K.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Imai, A. Imprints of late Mesozoic tectono-magmatic events on Palawan Continental Block in northern Palawan, Philippines. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2017, 142, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimalanta, C.; Faustino-Eslava, D.; Padrones, J.; Queaño, K.; Concepcion, R.; Suzuki, S.; Yumul, G., Jr. Cathaysian slivers in the Philippine island arc: Geochronologic and geochemical evidence from sedimentary formations of the west Central Philippines. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2018, 65, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knittel, U.; Hung, C.-H.; Yang, T.F.; Iizuka, Y. Permian arc magmatism in Mindoro, the Philippines: An early Indosinian event in the Palawan Continental Terrane. Tectonophysics 2010, 493, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knittel, U. 83 Ma rhyolite from Mindoro—Evidence for Late Yanshanian magmatism in the Palawan Continental Terrane (Philippines). Isl. Arc 2011, 20, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knittel, U.; Walia, M.; Suzuki, S.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Tamayo, R.; Yang, T.F.; Yumul, G.P. Diverse protolith ages for the Mindoro and Romblon Metamorphics (Philippines): Evidence from single zircon U–Pb dating. Isl. Arc 2017, 26, e12160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Takemura, S.; Yumul, G.P.; David, S.D.; Asiedu, D.K. Composition and provenance of the Upper Cretaceous to Eocene sandstones in Central Palawan, Philippines: Constraints on the tectonic development of Palawan. Isl. Arc 2000, 9, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumul, G.P.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Tamayo, R.A. Indenter-tectonics in the Philippines: Example from the Palawan microcontinental block Philippine Mobile Belt collision. Resour. Geol. 2005, 55, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumul, G.P.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Marquez, E.J.; Queano, K.L. Onland signatures of the Palawan microcontinental block and Philippine mobile belt collision and crustal growth process: A review. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2009, 34, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queano, K.L.; Ali, J.R.; Milsom, J.; Aitchison, J.C.; Pubellier, M. North Luzon and the Philippine Sea Plate motion model: Insights following paleomagnetic, structural, and age-dating investigations. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2007, 112, B05101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, M.; Yang, T.F.; Knittel, U.; Liu, T.K.; Lo, C.H.; Chung, S.L.; Teng, L.S.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Yumul, G.P., Jr.; Yuan, W.M. Cenozoic tectonics in the Buruanga Peninsula, Panay Island, Central Philippines, as constrained by U–Pb, 40Ar/39Ar and fission track thermochronometers. Tectonophysics 2013, 582, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumul, G.P.; Jumawan, F.T.; Dimalanta, C.B. Geology, Geochemistry and Chromite Mineralization Potential of the Amnay Ophiolitic Complex, Mindoro, Philippines. Resour. Geol. 2009, 59, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.D.C.; Faustino-Eslava, D.V.; Yumul, G.P., Jr.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Tamayo, R.A., Jr.; Yang, T.F.; Zhou, M.-F. Enriched and depleted characters of the Amnay Ophiolite upper crustal section and the regionally heterogeneous nature of the South China Sea mantle. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013, 65, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimando, R.; Rimando, J. The Central Mindoro Fault: An Active Sinistral Fault Within the Translational Boundary Between the Palawan Microcontinental Block and the Philippine Mobile Belt. GeoHazards 2025, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karig, D.E. Accreted terranes in the northern part of the Philippine archipelago. Tectonics 1983, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knittel, U.; Daniels, U. Sr-isotopic composition of marbles from the Puerto Galera area (Mindoro, Philippines); additional evidence for a Paleozoic age of a metamorphic complex in the Philippine island arc. Geology 1987, 15, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caagusan, N. Petrography of the metamorphic rocks of Northern Mindoro. Bull. Inst. Philipp. Geol. 1966, 1, 22–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sarewitz, D.R.; Karig, D.E. Processes of allochthonous terrane evolution, Mindoro Island, Philippines. Tectonics 1986, 5, 525–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canto, A.P.B.; Padrones, J.T.; Concepcion, R.A.B.; Perez, A.D.C.; Tamayo, R.A., Jr.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Faustino-Eslava, D.V.; Queaño, K.L.; Yumul, G.P., Jr. Geology of northwestern Mindoro and its offshore islands: Implications for terrane accretion in west Central Philippines. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 61, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concepcion, R.A.B.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Yumul, G.P., Jr.; Faustino-Eslava, D.V.; Queaño, K.L.; Tamayo, R.A., Jr.; Imai, A. Petrography, geochemistry, and tectonics of a rifted fragment of Mainland Asia: Evidence from the Lasala Formation, Mindoro Island, Philippines. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2012, 101, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Kase, T.; Shigeta, Y.; De Ocampo, R.S.; Ong, P.A.; Aguilar, Y.M.; Mago, W. Newly Collected Jurassic Ammonites from the Mansalay Formation, Mindoro Island, Philippines. Bull. Natl. Mus. Natl. Sci. Ser. C 2012, 38, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sarewitz, D.R.; Karig, D.E. Geologic evolution of western Mindoro Island and the Mindor Suture Zone, Philippines. J. Southeast Asian Earth Sci. 1986, 1, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchadier, Y.; Rangin, C. Polyphase tectonics at the southern tip of the Manila Trench, Mindoro-Tablas Islands, Philippines. Tectonophysics 1990, 183, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Dilek, Y.; Yumul, G.P., Jr.; Yan, Y.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Huang, C.-Y. Slab-controlled elemental–isotopic enrichments during subduction initiation magmatism and variations in forearc chemostratigraphy. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2020, 538, 116217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, M.; Marchadier, Y.; Rangin, C. Pre-Eocene synmetamorphic structure in the Mindoro-Romblon-Palawan area, West Philippines, and implications for the history of Southeast-Asia. Tectonics 1989, 8, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiminami, K. Parentage of low-grade metasediments in the Sanbagawa belt, eastern Shikoku, Southwest Japan, and its geotectonic implications. Isl. Arc 2010, 19, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sláma, J.; Kosler, J.; Condon, D.J.; Crowley, J.L.; Gerdes, A.; Hanchar, J.M.; Horstwood, M.S.A.; Morris, G.A.; Nasdala, L.; Norberg, N.; et al. Plesovice zircon—A new natural reference material for U-Pb and Hf isotopic microanalysis. Chem. Geol. 2008, 249, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenbeck, M.; Alle, P.; Corfu, F.; Griffin, W.; Meier, M.; Oberli, F.; Quadt, A.V.; Roddick, J.; Spiegel, W. Three natural zircon standards for U-Th-Pb, Lu-Hf, trace element and REE analyses. Geostand. Newsl. 1995, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, L.; Gulson, B. The age of the mud tank carbonatite, strangways range, northern territory. BMR J. Aust. Geol. Geophys. 1978, 3, 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, H.; Chung, S.; Wu, F.; Liu, D.; Liang, Y.; Lin, I.; Iizuka, Y.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Chu, M. Zircon U–Pb and Hf isotopic constraints from eastern Transhimalayan batholiths on the precollisional magmatic and tectonic evolution in southern Tibet. Tectonophysics 2009, 477, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T. Correction of common lead in U-Pb analyses that do not report 204Pb. Chem. Geol. 2002, 192, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.R. Isoplot v. 3.0: A Geochronological Toolkit for Microsoft Excel; Special Publication; Berkeley Geochronology Center: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003; Volume 4, p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeesch, P. On the visualisation of detrital age distributions. Chem. Geol. 2012, 312, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeesch, P. Multi-sample comparison of detrital age distributions. Chem. Geol. 2013, 341, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MMAJ. Report on Geological Survey of Mindoro Island, Phase II; Metal Mining Agency of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 1983; p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Andal, D.R.; Esguina, J.S.; Hashimoto, W.; Reyes, B.P.; Sato, T. The Jurassic Mansalay Formation, southern Mindoro, Philippines. In Geology and Paleontology of SE Asia; University of Tokyo Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1968; Volume 4, pp. 179–197. [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama, K.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Kase, T.; Queano, K.; Aguilar, Y. Provenance study of Jurassic to Early Cretaceous sandstones from the Palawan microcontinental block, Philippines. Mem. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci. 2012, 48, 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.; Zheng, H.; Clift, P.D. Zircon U–Pb geochronology and Hf isotope data from the Yangtze River sands: Implications for major magmatic events and crustal evolution in Central China. Chem. Geol. 2013, 360, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; O’Reilly, S.; Griffin, W.; Wang, X.; Pearson, N.; He, Z. The crust of Cathaysia: Age, assembly and reworking of two terranes. Precambr. Res. 2007, 158, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Yi, L.; Yin, X.; Wang, A.; Li, Y.; Chen, J. Detrital zircons U-Pb age and Hf isotope from the western side of the Taiwan. Terr. Atmos. Ocean Sci. 2014, 25, 505–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhao, T. Using detrital zircons from river sands to constrain major tectono-thermal events of the Cathaysia Block, SE China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2016, 124, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.