Simple Summary

In this study, Tg (GnIH: mCherry) and esr2b knockout zebrafish were constructed to explore the regulation between estrogen receptors and gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone (GnIH). Our work showed that GnIH neuropeptide expression location overlaps with that of Hcrt at 36 hpf and 72 hpf. Estrogen treatment experiments showed that an appropriate dose of E2 is able to induce GnIH mRNA levels. High-dose E2 will induce a feedback mechanism. Esr2b knockout led to increased GnIH mRNA levels in zebrafish embryos and it started on the fourth day. In a word, estrogen receptors are able to regulate GnIH expression, but esr2b is involved in negative regulation.

Abstract

Gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone (GnIH) is a neuropeptide involved in the regulation of reproductive function in vertebrates. It is able to inhibit the synthesis and secretion of GnRH and Gth in the HPG axis. However, the regulatory role and mechanism by which current gonadal steroid hormones regulate GnIH are still unclear. In this study, transcription factor binding site analysis was performed on the promoter sequence of zebrafish GnIH. Whereafter, transgenic zebrafish (GnIH: mCherry) accurately labeled GnIH and esr2b knockout zebrafish, which were constructed previously, were used to explore the regulation between estrogen and GnIH. In vitro exposure of wild-type zebrafish embryos and transgenic zebrafish embryos to estradiol showed that 10 μM estradiol significantly increased the transcription level of GnIH. However, both 10 μM and 50 μM estradiol significantly increased the transcription level of GnIH in esr2b knockout zebrafish. We compared the expression levels of GnIH in esr2b knockout zebrafish and wild-type zebrafish at different developmental stages (48 hpf–120 hpf). The results showed that from 96 hpf, the expression level of GnIH in esr2b knockout zebrafish was significantly higher than that in wild-type zebrafish, indicating that esr2b is involved in the negative regulation of GnIH, and this regulatory relationship is established on the fourth day of zebrafish development.

1. Introduction

Gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone (GnIH) is a short peptide composed of twelve amino acids that was isolated from the hypothalamus of Japanese quail by the Japanese scholar Tsutsui [1]. Subsequently, homologous genes for GnIH have been identified in different fish, including goldfish, Nile tilapia, European eel, Atlantic salmon, Medaka, Zebrafish, and common carp [2,3,4,5,6,7]. GnIH is able to negatively influence the reproduction of vertebrates through the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis. Micro-osmotic pumps containing GnIH peptides were implanted under the skin of male Japanese quail, and after two weeks of treatment, the mRNA expression of the alpha and LH beta subunits of gonadotropins in the pituitary gland of the quail was significantly decreased [8]. The mRNA expression of the FSH beta subunit also decreased, and the levels of LH and testosterone in the blood were significantly reduced [8]. Results in hamsters showed that the secretion of LH was significantly inhibited after intracerebroventricular or subcutaneous injection of GnIH peptides [9]. The inhibitory effect of GnIH on gonadotropins may be achieved by directly affecting the secretion activity of GnRH. In the brain of European starlings, Ubuka and colleagues found that GnIH and GnRH nerve fibers were directly connected [10]. In addition, GnIH receptors were found to be expressed in GnRH-secreting cells [10]. Similarly, the direct connection between GnIH nerve fibers and GnRH was detected in the septal regions, preoptic area, and anterior hypothalamic area of rodents’ (mice, rats, and hamsters) brains [8]. Electrophysiological experiments also showed that the injection of GnIH peptides into the mouse brain could directly inhibit the activity of 41% of GnRH neurons [11]. In summary, current research indicates that GnIH may negatively regulate vertebrate reproductive activity by inhibiting the secretion activity of GnRH neurons or directly inhibiting the secretion of gonadotropins in the pituitary gland.

Estrogen is a type of steroid hormone produced by the ovaries through the catalysis of aromatase P450 from testosterone [12]. Estrogen plays an important role in ovarian development and maintenance of secondary sexual characteristics in female vertebrates. The synthesis and secretion of key factors GnRH, FSH, and LH in the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis are regulated by estrogen feedback [13]. The main function of estrogen is to bind and activate its receptor in order to regulate downstream gene expression. In rodents, two types of estrogen receptors were identified: estrogen receptor α(ERα) and estrogen receptor β [14,15]. In zebrafish, four kinds of estrogen were identified: esr1 (ERα), esr2a (ER βII), esr2b (ER βI), and gper [16]. To analyze the role of different estrogen receptors in teleosts, gene editing technology TALENS or CRISPR-Cas9 were used in ER knockout zebrafish construction. In gper knockout female zebrafish, plasma levels of vitellogenin were reduced significantly and follicle development was retarded [17]. Esr1, esr2a, and esr2b single knockout resulted in a male-biased sex ratio (70–85%), but reproductive development and function were normal [18]. It was also reported that esr2b knockout leads to embryo development delay and a mortality rate increase during zebrafish development [19]. qPCR and in situ hybridization results demonstrated a significant downregulation of cyp19ab1b expression in esr2b knockout embryos compared to wild-type embryos [19]. Meanwhile, few study have focused on the function of estrogen receptors during early embryo development. The MO technique is a widely used approach for investigating gene function during the early stages of embryonic development in zebrafish. Griffin designed all esr1, esr2a, and esr2b MOs. Single or combined MOs were injected into zebrafish embryos [20]. Both esr1 and esr2b MOs blocked estradiol induction of vitellogenin and ERα mRNAs. Only esr2b MO was able to block the induction of cyp19a1b mRNA through estrogen treatment [20]. It was also reported that esr2a is involved in neuromast development in zebrafish [21]. Esr2a MO activated the Notch signaling pathway, leading to abnormal hair cell development [21].

In ovariectomized mouse, subcutaneous administration of 17β-estradiol for 4 days by implanting silastic capsules significantly reduced GnIH mRNA levels [22]. Evidence from dual-label immunohistochemistry showed approximately 20% of the GnIH neurons expressed estrogen receptor (ER)-α, but not ERβ [8]. In female hamsters, ER-α mRNA was also found in GnIH immunoreactive cells [8]. Estrogen treatment in ovariectomized hamster increased c-fos labeling in GnIH neurons [8].

Although estrogen was found to influence GnIH expression in rodent brains, reports are rare, and the mechanisms are still unclear. In this study, Tg (GnIH: mCherry) transgenic zebrafish and esr2b knockout zebrafish were established to assess the relationship between estrogen and GnIH expression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Zebrafish

Different zebrafish lines (wild-type\transgenic\gene knockout zebrafish) were raised at a constant temperature of 28 degrees Celsius and under a 12 h:12 h light–dark cycle. Zebrafish embryos were obtained through natural breeding of female and male zebrafish. To facilitate subsequent in situ hybridization experiments and fluorescence observation, 0.003% (w/v) of 1-phenyl-2-thiourea was added to the water when the zebrafish embryos developed to 24 h to inhibit pigment formation. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Special Committee of Science Ethics, Academic Committee of Hunan University of Arts and Sciences (2022090733).

2.2. Drug Treatment

17β-estradiol(E2) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) used for drug treatment was purchased from Sigma. The drug was dissolved in DMSO to prepare 1 mM, 10 mM, and 50 mM stock solutions. Three different experimental concentrations of 1 μM, 10 μM, and 50 μM were used to treat the zebrafish embryos. Approximately 30 zebrafish embryos were placed in a 4 cm culture dish, and 3 replicates were set for each concentration. The medium containing E2 was added to the embryos on the second day, and the control group used water containing 0.1% DMSO. The culture medium was replaced with fresh water every 24 h, and on the fourth day, the embryos were placed in 4% PFA for in situ hybridization detection or stored in Trizol at −80 degrees Celsius for RNA extraction and qPCR detection.

2.3. In Situ Hybridization

Different developmental stages of zebrafish embryos were fixed with 4% PFA/PBS solution, kept at 4 degrees Celsius overnight, dehydrated with methanol, and stored at −20 degrees Celsius for later use. In situ hybridization was mainly conducted according to the method described by Thisse, C. and Thisse, B [23]. Dual-color in situ hybridization was mainly carried out according to the descriptions of Hauptmann, G. and Jowett, T [24,25]. For in situ hybridization, partial sequences of different genes were amplified and cloned into PCS2+ plasmids. These constructed plasmids were linearized. A T7 Transcription Kit (Roche., Basel, Switzeland) was used for probe synthesis. The primers used for in situ hybridization are listed in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used for probes and qPCR (protecting group is in bold type).

2.4. Preparation of Transgenic and esr2b Knockout Zebrafish

The JASPAR database was used for transcription factor binding analysis (https://jaspar.elixir.no/, 16 September 2020). The sequence information of the GnIH gene was obtained from the Vega database. GnIH promoter fragments with lengths of 2.4 kb (−2357 to +50) were obtained. The amplified GnIH promoter fragments were connected to the Psk-CMV + mCherry plasmid using XhoI and ClaI enzymes. This vector has a transposase binding site and fluorescence label. The GnIH promoter sequence was then sequenced for validation. The plasmids containing the GnIH promoter sequence (100 ng/μL–200 ng/μL) were mixed with phenol red and injected into zebrafish embryos at the one-cell stage using a PLI-90 microinjector (Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA). Approximately 400 embryos were injected, and the fluorescence location was observed and recorded after the embryos were raised to the three-day post-fertilization stage. The equipment used for photography and fluorescence observation was a Nikon digital sight DS-5Mc camera (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) attached to an Olympus fluorescence acro-microscope MVX10 (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Because the 2.4 kb GnIH promoter had the best fluorescence intensity and accuracy after injection, we chose it to prepare the transgenic zebrafish lines. The method for preparing transgenic zebrafish lines followed the procedure described by Song et al. [26]. The plasmid containing the 2.4 kb GnIH promoter (50 ng/uL), the Tol2 transposase (100 ng/uL), and phenol red were mixed together and injected into zebrafish one-cell stage embryos. After the embryos developed for two days, luminescent embryos were screened and raised to maturity. F1 generation transgenic zebrafish were obtained by crossing them with wild-type zebrafish, and luminescent individuals were selected and raised to maturity for crossing to produce F2 generation transgenic zebrafish. F2 generation transgenic zebrafish were self-crossed to obtain F3 generation homozygous individuals.

The TALENs method was used for zebrafish esr2b knockout. For details refer to Peng [19]. mRNA was mixed at a concentration of 100 ng/uL, and phenol red was added before microinjection. After the zebrafish developed to 48 hpf, 5–10 zebrafish embryos were collected, and DNA was extracted for identification of the mutation. The P0 generation embryos were raised to maturity (about 3 months) and crossed with wild-type zebrafish to obtain F1 generation knockout zebrafish. The tails of the F1 generation zebrafish were cut off, and DNA was extracted to identify the type of mutation. F1 generation female and male zebrafish with the same type of mutation were selected and crossed to obtain F2 generation knockout zebrafish. The tails of F2 generation knockout zebrafish were cut off, and DNA was extracted to identify the homozygous individuals with esr2b gene knockout.

2.5. Real-Time PCR

The Ultra-Pure Total RNA Extracting Kit (Simgen, Hangzhou, China) was used for RNA extraction. The zebrafish RNA was checked for purity and integrity using gel electrophoresis and a spectrophotometer (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA), respectively. DNaseI was used to eliminate contaminating genomic DNA prior to reverse transcription. The cDNA Synthesis Master Mix Kit (Simgen, Hangzhou, China) was chosen for cDNA synthesis. Briefly, 1 μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed, and the resulting cDNA was diluted five fold for qPCR analysis. Next, 2 × One Step SYBR Green RT-qPCR Mix (Simgen, Hangzhou, China) was used for qPCR, which was performed on a Bio-Rad CFX96 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The 20 μL PCR reaction contained 10 μL of SYBR mix, 6.4 μL of deionized water, 0.8 μL of forward primer, 0.8 μL of reverse primer (primers listed in Table 1), and 2 μL of cDNA. The qPCR program consisted of 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 45 s. β-actin was used as an internal reference, and the 2−△△ct method was used to calculate gene expression levels.

2.6. Statistics

All estrogen exposure experiments were repeated 3 times. The results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) values. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 10.0 and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Target gene expression levels were normalized to the expression of β-actin mRNA. All data were analyzed using a Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with multiple comparisons of means performed using Tukey’s test method.

3. Results

3.1. Expression of GnIH During Embryonic Development

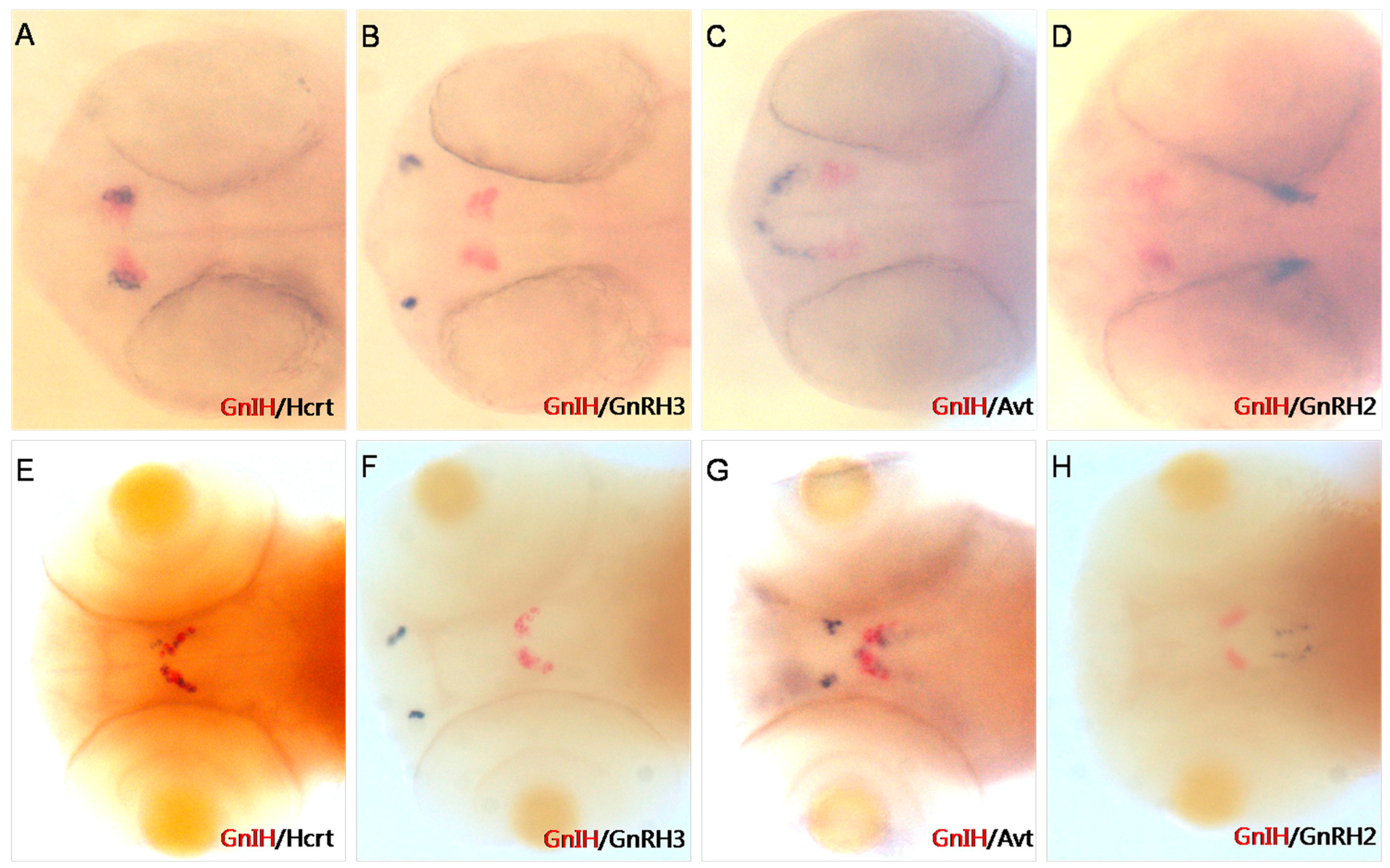

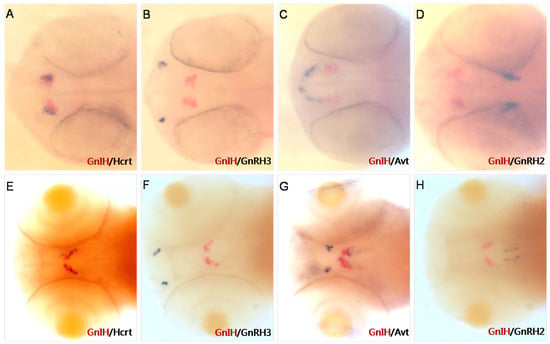

To accurately determine the expression location of GnIH in early zebrafish embryonic development, we performed double-color in situ hybridization of GnIH and other neuropeptides in the brain (Figure 1). The results of double-color in situ hybridization showed that at 36 hpf, the expression of GnIH and Hcrt was located in the same position in the zebrafish brain (Figure 1A), while at 72 hpf, the expression of GnIH and Hcrt was staggered in the lateral part of the hypothalamus of zebrafish (Figure 1E). Additionally, this study found that at 36 hpf, the expression of GnIH was located anterior to that of Avt (Figure 1C), and by 72 hpf, the expression of Avt in the hypothalamus was adjacent to the expression of GnIH (Figure 1D). However, in early zebrafish embryonic development, the expression location of GnIH was not in the same region as reproductive-associated factors GnRH2/3 (Figure 1B,F,G).

Figure 1.

Two-color in situ hybridization detection of GnIH, Hcrt, GnRH3, Avt, and GnRH2 (dorsal view) at 36 hpf (A–D) and 72 hpf (E–H). Other peptides mark different areas in the brain. At 36 hpf and 72 hpf, Hcrt is expressed in the lateral hypothalamus (A,E); GnRH3 mRNA is localized in the vicinity of the developing olfactory organ at 36 hpf (B). At 72 hpf, it migrates to the transitional area between the olfactory organ and olfactory bulb (F); Avt mRNA is localized in the pre-optic area (front of GnIH signals) and ventral hypothalamus (close to GnIH mRNA); GnRH2 mRNA is expressed in the lateral midbrain at 36 hpf and 72 hpf (D,H).

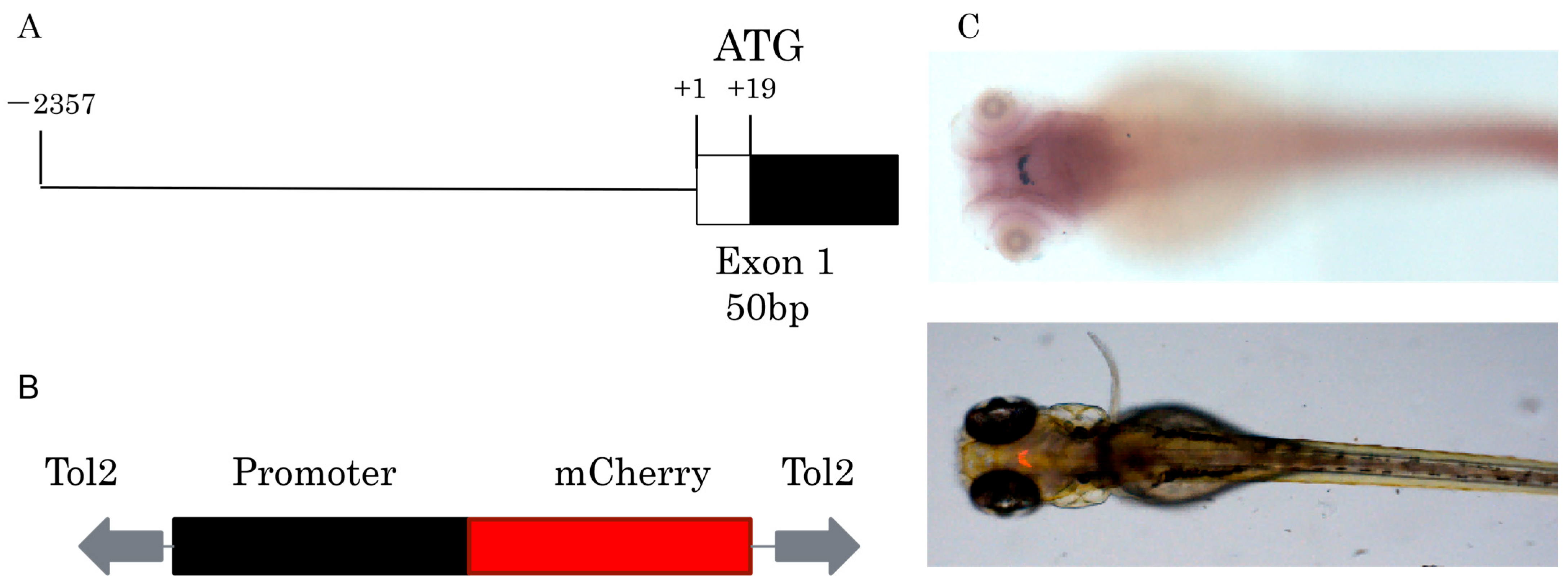

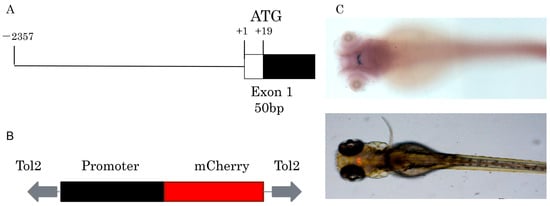

3.2. Establishment of a Zebrafish Line Expressing a Red Fluorescent Signal Under the GnIH Promoter

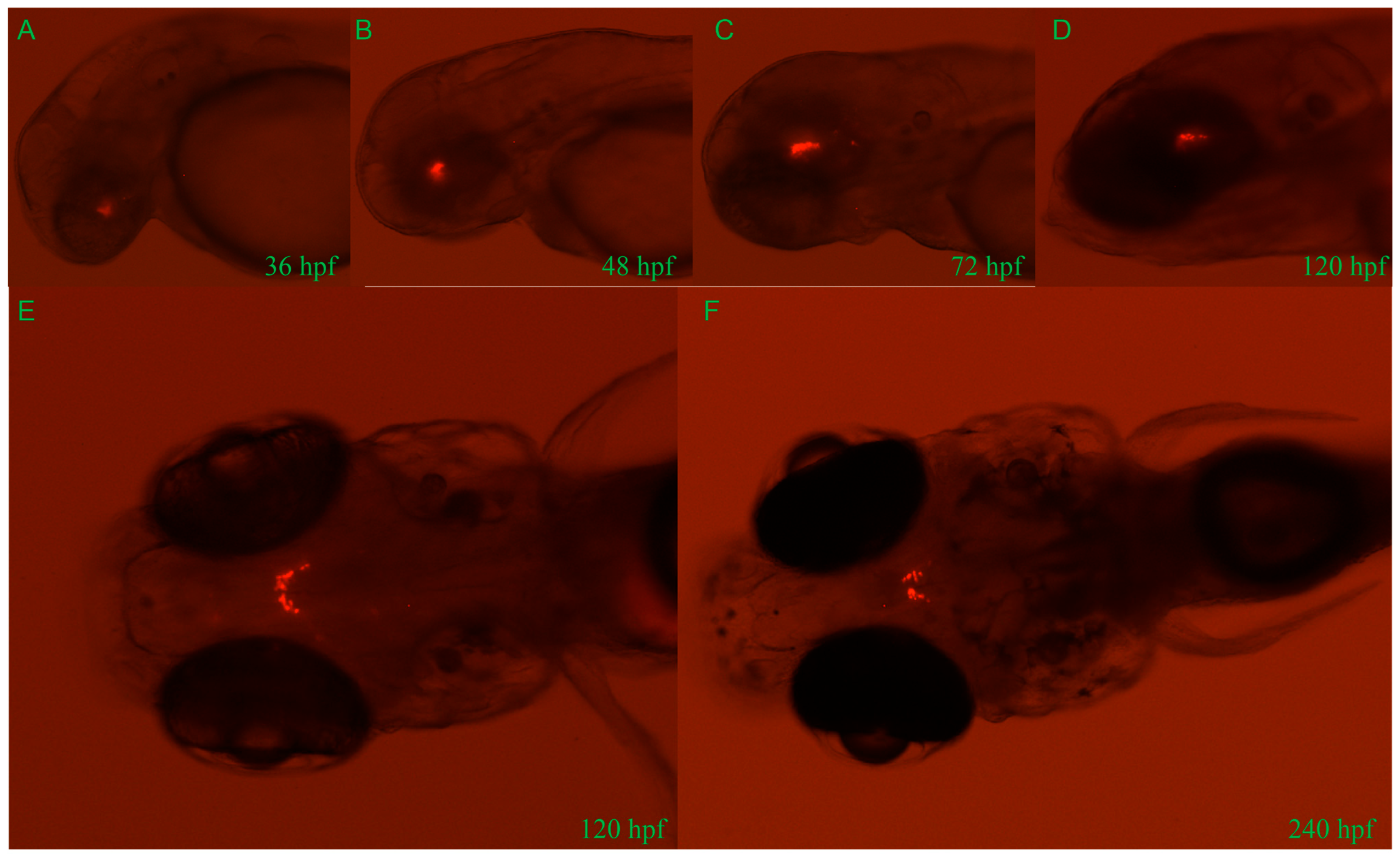

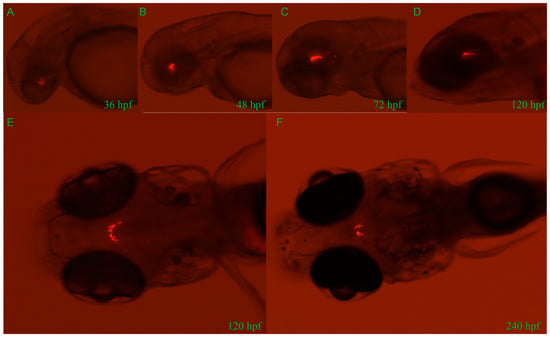

Approximately 2.4 kb length upstream of the GnIH gene was cloned for construction of transgenic zebrafish line Tg (GnIH:mCherry), which contains the non-coding sequence upstream of the GnIH gene 2357 bp and 50 bp of the first exon’s sequence (Figure 2). The results of in situ hybridization showed that the expression pattern of endogenous GnIH mRNA was consistent with the mCherry fluorescence signal (Figure 2C). Subsequently, the fluorescence signals during zebrafish embryonic development were recorded from 36 hpf to 240 hpf (Figure 3). At 36 hpf, specific red fluorescence signals were firstly observed in the brain of transgenic zebrafish embryos. From 48 hpf to 120 hpf, mCherry fluorescence of GnIH mRNA continued to be clear and specific in zebrafish brain. The fluorescence signal was still clear and stable at 240 hpf. The fluorescence signals were never detected outside the unique area, indicating that the GnIH transcripts were restricted to the lateral hypothalamus, just like Hcrt. From 36 hpf to 72 hpf, the signals were notably enhanced, accompanied by signal migration.

Figure 2.

Construction of Tg (GnIH:mCherry) transgenic line. (A) The fragment used to drive mCherry fluorescence contains 2357 bp of 5′-flanking region and 50 bp of exon1. (B) The main elements of the plasmid used for generation of the transgenic zebrafish line, the plasmid contains tol2 elements and mCherry, the promoter elements were replaced by GnIH promoter fragments. (C) In situ hybridization of GnIH mRNA and mCherry fluorescence signal in transgenic zebrafish at 72 hpf (dorsal view).

Figure 3.

Developmental profile of mCherry fluorescence in the Tg (GnIH:mCherry) zebrafish line from 36 hpf to 240 hpf (10 dpf). Lateral views of mCherry fluorescence from 36 hpf to 120 hpf (A–D). From 36 hpf to 120 hpf, the fluorescence migrates to the lateral hypothalamus. Dorsal views of mCherry fluorescence at 120 hpf (5 d) and 240 hpf (10 d) (E,F). Consistent with results of in situ hybridization, all fluorescence is restricted in the area of brain.

Then, JAPAR, an online database, was used for screening potential transcription factors. The result of transcription binding factor analysis showed that there exists 12 potential estrogen receptor binding sites (Supplementary File S1).

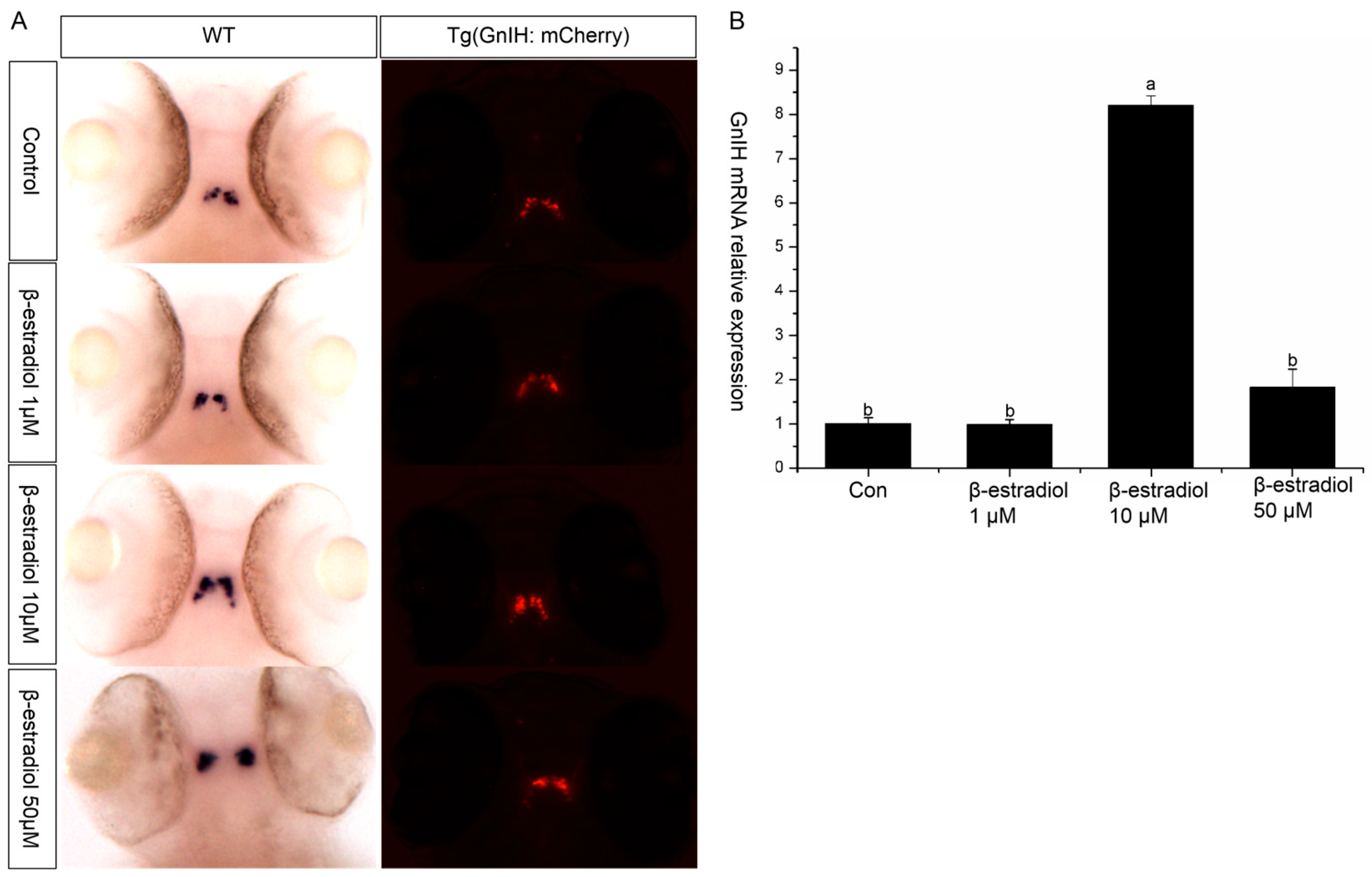

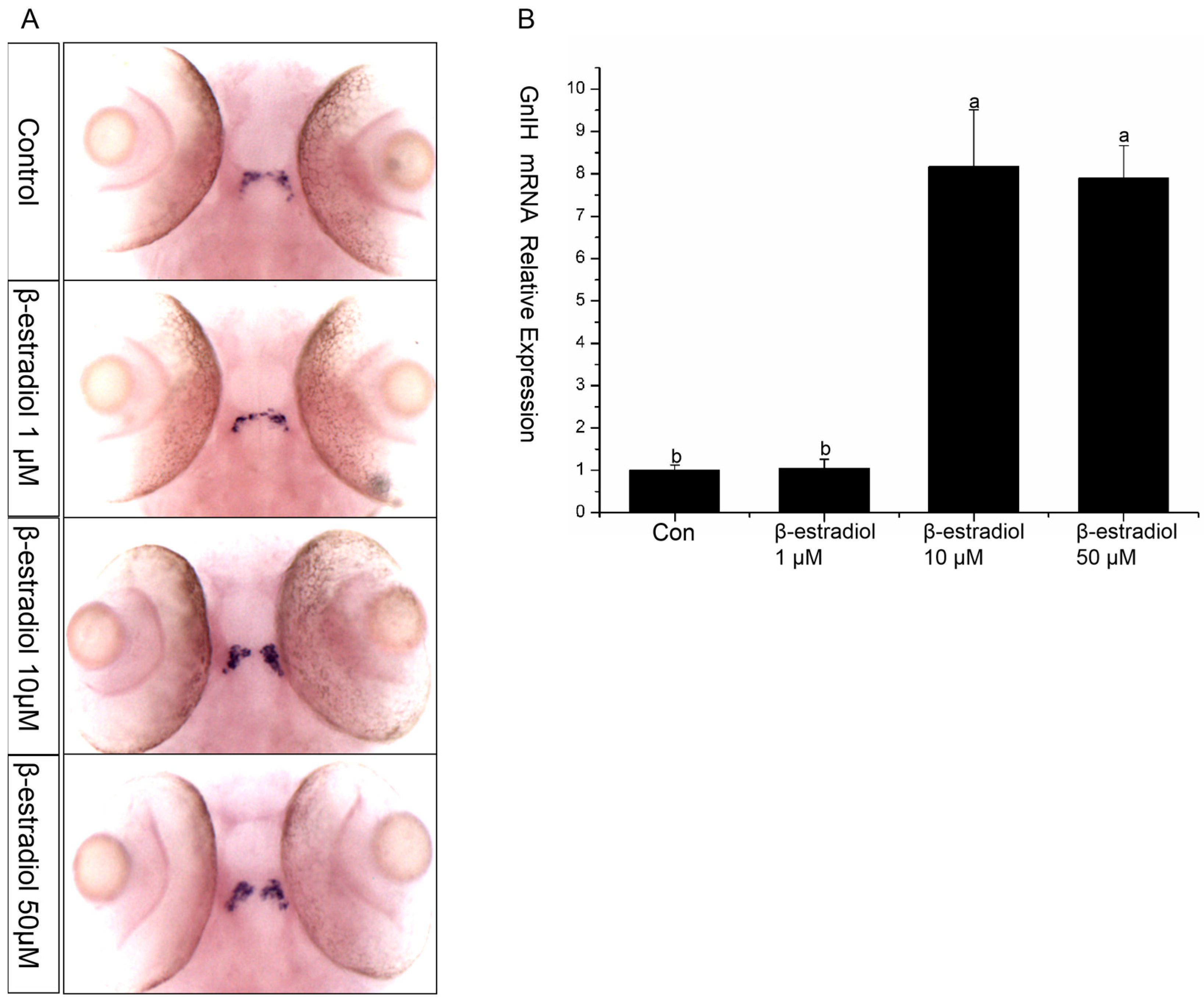

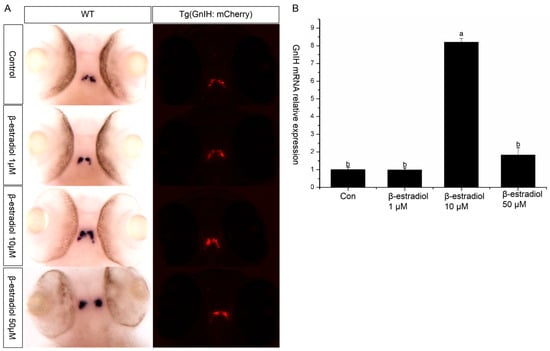

3.3. The Effect of Estrogen on GnIH Expression

To explore the regulatory role of estrogen on GnIH, wild-type and transgenic zebrafish embryos were exposed to estradiol for 48 h from 48 hpf, with exposure maintained until 96 hpf. Then, in situ hybridization and qPCR were performed to detect the expression changes of GnIH in the wild-type zebrafish, and images were captured to record the fluorescent signals in the transgenic zebrafish. The results of in situ hybridization showed that 1 μM and 50 μM had no significant effect on the GnIH mRNA content, while 10 μM significantly increased the level of GnIH mRNA (Figure 4A). The results of treating transgenic zebrafish embryos with estradiol also showed that the expression level of red fluorescence in the transgenic zebrafish embryos treated with 10 μM estradiol increased significantly (Figure 4A). The qPCR results showed that 1 μM estradiol had no effect on the expression of GnIH mRNA, 10 μM estradiol could significantly increase the expression of GnIH mRNA, and 50 μM estradiol could promote the expression of GnIH, but there was no significant difference compared with the 1 μM treatment group (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

β-estradiol treatment experiments. In the treatment experiments, each treatment group contains 30 embryos (3 parallel). All samples were treated from 48 hpf to 96 hpf. At 96 hpf, in situ hybridization, qPCR, and fluorescence signals were detected. (A) In situ hybridization to detect GnIH mRNA changes of wild-type zebrafish embryos treated with different doses of β-estradiol (1 μM, 10 μM, 50 μM). This treatment experiment was also repeated using transgenic zebrafish embryos. (B) In the wild-type zebrafish embryo treatment experiments, qPCR was also preformed to confirm the results. The results are presented as mean ± SEM values. Values accompanied by different letters are significantly different (ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, p < 0.05).

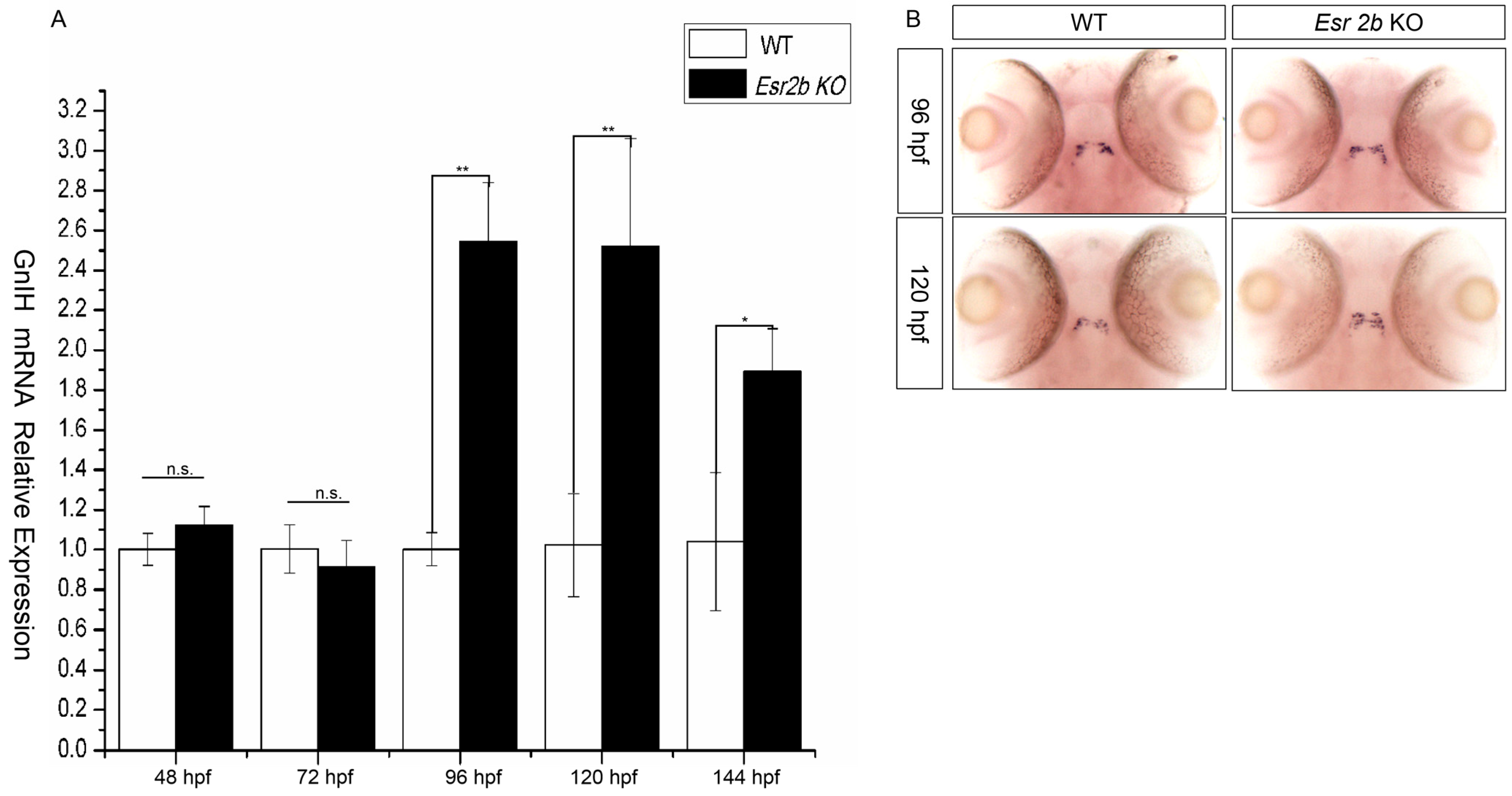

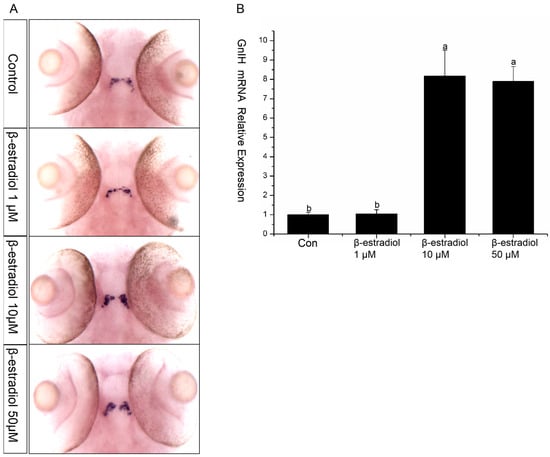

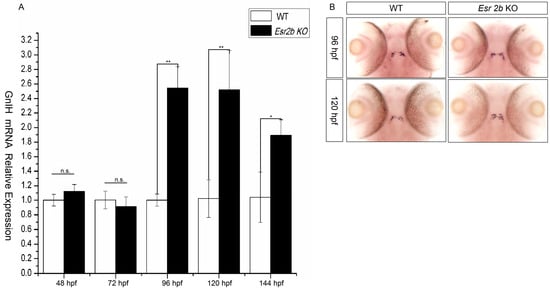

3.4. The Effect of Estrogen Receptor 2b Knockout on GnIH Expression

To further investigate the regulatory effect of estrogen on GnIH, esr2b knockout zebrafish were obtained using the TALENs method. Subsequently, we treated 48 hpf esr2b knockout zebrafish embryos with 1μM, 10 μM, and 50 μM estradiol for 48 h. In situ hybridization and qPCR were used to detect the expression of GnIH (Figure 5). The results showed that, similar to wild-type zebrafish embryos, 1 μM estradiol had no significant effect on GnIH expression, while 10 μM and 50 μM estradiol significantly promoted GnIH expression (Figure 5A,B). In addition, the expression levels of GnIH in wild-type and esr2b knockout zebrafish at different developmental stages were detected using qPCR and in situ hybridization. The qPCR results showed that there was no significant difference in GnIH expression between wild-type and esr2b knockout zebrafish embryos at 48 hpf and 72 hpf. However, at 96 hpf, 120 hpf, and 144 hpf, the expression of GnIH in esr2b knockout zebrafish embryos was significantly higher than that in wild-type embryos (Figure 6A). The in situ hybridization results also showed that at 96 hpf and 120 hpf, the expression of GnIH in esr2b knockout zebrafish was significantly higher than that in wild-type zebrafish (Figure 6B).

Figure 5.

GnIH mRNA changes in esr2b knockout zebrafish embryos in the β-estradiol treatment experiments. (A) In situ hybridization to detect GnIH mRNA changes of esr2b knockout zebrafish embryos treated with different doses of β-estradiol (1 μM, 10 μM, and 50 μM). (B) qPCR results of the treatment experiments. The results are presented as mean ± SEM values. Values accompanied by different letters are significantly different (ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

The difference in GnIH mRNA expression between wild-type and esr2b knockout zebrafish at different developmental stages. (A) qPCR was also performed to detect the difference in GnIH mRNA expression level from 48 hpf to 144 hpf. (* represents a significant difference, p < 0.05; ** represents a significant difference, p < 0.01). (B) In situ hybridization to detect between wild-type and esr2b knockout zebrafish embryos at 96 hpf and 120 hpf. At different developing points, 30 embryos of wild-type and esr2b knockout zebrafish were sampled for in situ hybridization and qPCR detection.

4. Discussion

As a neuropeptide that negatively regulates reproduction, the early development of GnIH is still poorly understood. Immunohistochemical results in zebrafish showed that the GnIH protein signal is present in the hypothalamus at 37 hpf [27]. Zhang et al. used RT-PCR to monitor the expression of GnIH during zebrafish embryonic development and found that zebrafish GnIH began to be expressed at the prim-5 stage [7]. In our previous work, in situ hybridization results showed that the GnIH signal appeared in zebrafish at 24 hpf. In the present work, GnIH had a specific distribution in the zebrafish brain during early development, showing a symmetrical distribution (Figure 1). Dual-color in situ hybridization results showed that GnIH was expressed in a position that overlapped with Hcrt expression in the early stage, located in the ventral midbrain of the hypothalamus, also known as the lateral hypothalamus [28]. In vertebrates, the brain has functional divisions. The expression position overlap indicated that GnIH and Hcrt may perform similar functions. The Hcrt gene encodes neuropeptide that is involved in the regulation of sleep and energy balance in mammals [28]. However, GnIH signaling and GnIH-expressing neurons are both necessary and sufficient to promote sleep, mature peptides derived from the GnIH preproprotein promote sleep in a synergistic manner, and stimulation of GnIH-expressing neurons induces neuronal activity levels consistent with normal sleep [29]. In addition, the zebrafish prepared in this study with the transcribed GnIH promoter accurately marked the activity of endogenous GnIH. By tracking the fluorescence labeling of transgenic zebrafish embryos, we found that GnIH fluorescence signals were concentrated in the lateral hypothalamus and were highly specific. The signals were first observed at 36 hpf (Figure 3). Currently, zebrafish mainly contain three nucleus estrogen receptors: esr1, esr2a, and esr2b. Research on the three estrogen receptors in zebrafish embryos showed that in the early stage of zebrafish embryonic development, the content of esr2a mRNA was high in newly fertilized oocytes of zebrafish, the content of esr2a mRNA gradually decreased and disappeared between 6 hpf and 12 hpf of zebrafish embryonic development, and when the zebrafish developed to 24 hpf, the homozygous gene was activated, and the content of esr2a mRNA began to rise again [30,31]. Unlike esr2a, the expression level of esr2b was very low in newly fertilized oocytes of zebrafish, and the expression levels of the two receptors increased significantly as zebrafish embryos developed [30,32]. Overall, during the 12 hpf–48 hpf developmental period of zebrafish embryos, the mRNA expression levels of the three estrogen receptors were relatively low, and the content of estrogen receptor mRNA increased significantly from around 48 hpf [33]. In situ hybridization results of zebrafish embryos showed that the content of esr2a and esr2b mRNA increased significantly from 48 hpf to 60 hpf, and most of the signal was located in the hypothalamus area [34]. In contrast to esr2a and esr2b, esr1 mRNA had a relatively low content in the early stage of zebrafish embryo development, mainly located in the liver [34]. Estrogen receptors were involved in regulating cyp19a1b during zebrafish embryo development. A low dose of estradiol (10−8 μM) was able to trigger cyp19a1b expression in the preoptic area and mediobasal hypothalamus at 48 hpf and 108 hpf [35]. The cyp19a1b-gene is so sensitive to estrogens that it has been proposed as a biomarker for estrogenic exposure. It was reported that the cyp19a1b promoter containing an estrogen-responsive element (ERE) located upstream of the transcription start site is absolutely mandatory for upregulating aromatase expression by estrogens [35]. This evidence indicated that estrogen receptors are involved in neurogenesis during zebrafish development [36]. Meanwhile, estrogen receptors esr2a and esr2b are widely present in the hypothalamus of zebrafish embryos in the early stage of development, consistent with the expression location of GnIH, and early expression of GnIH is likely to be regulated by estrogen.

Currently, there is very limited research on the regulation of GnIH by estrogen. In mice, Molnár et al. implanted capsules containing estradiol under the skin of female mice that already had their ovaries removed, and after four days of treatment, they found a significant decrease in the amount of GnIH mRNA [22]. In addition, researchers found that estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) is expressed in GnIH neurons [9]. In hamsters, it was also found that about 40% of GnIH neurons express ERα, and treatment with estradiol in hamsters can enhance GnIH neuron secretion activity [9]. These pieces of evidences suggest that estrogen regulates the expression of GnIH through ERα. In this study, we conducted a transcription factor binding analysis of GnIH promoter sequence fragments and found potential estrogen receptor binding sites on the sequence. Subsequently, we treated wild-type zebrafish embryos and transgenic zebrafish embryos (Tg GnIH: mCherry) with estradiol and found that 1 μM estradiol had no effect on GnIH expression, while 10 μM estradiol significantly increased GnIH expression, and 50 μM estradiol increased GnIH expression, but not significantly. These results indicate that estrogen is able to promote the expression of GnIH during the early stage of zebrafish development. GnRH is a classic neuropeptide involved in regulating vertebrate reproduction. In both males and females, gonadal steroid hormones exert negative feedback regulation on axis activity at the levels of both the pituitary and the hypothalamus [13]. The feedback regulation is mediated by estrogen receptors(ERs). Many studies have shown that estrogen has a bimodal effect on the hypothalamus with both inhibitory and stimulatory influences on GnRH secretion [37,38,39,40,41]. In an in vivo study, there was observed a decrease in GnRH expression and secretion by estradiol in both the GN11 and GT1-7 GnRH-expressing cell lines, and these effects were determined to be primarily mediated by ERα in GT1-7 cells and by both ERα and ERβ in GN11 cells [40]. In our work, 10 μM was able to induce GnIH transcription. But a high dose of estrogen (50 and 100 μM) lost this function. We hypothesize that the failure of elevated estrogen concentrations to upregulate GnIH expression is likely attributable to classical negative feedback regulation. To further study the regulation of GnIH by estrogen, esr2b knockout zebrafish were constructed. Similarly, esr2b knockout zebrafish embryos were treated with estradiol and we found that a 1 μM concentration of estradiol still had no effect on GnIH expression, while 10 μM and 50 μM estradiol both significantly promoted GnIH expression. Since zebrafish contain three types of estrogen receptors, esr1, esr2a, and esr2b, we hypothesized that after esr2b knockout, estrogen may still promote GnIH expression through esr1 or esr2a. Interestingly, high concentrations of estradiol (50 μM) did not significantly promote GnIH expression in wild-type zebrafish but significantly increased GnIH expression in esr2b knockout zebrafish. Afterward, we detected the expression of GnIH in the development process of esr2b knockout zebrafish (48 hpf–144 hpf) and found that there was no significant difference in the expression of GnIH in zebrafish embryos at 48 hpf and 72 hpf between esr2b knock-out and wild-type zebrafish. However, from 96 hpf, the expression of GnIH in esr2b knockout zebrafish was significantly higher than that in wild-type zebrafish. Therefore, we believe that esr2b may be responsible for the negative regulation of GnIH expression, and the establishment of this relationship begins on the fourth day of embryonic development. Our work mainly explored the regulatory role of the estrogen signaling pathway in the early development of GnIH in zebrafish by preparing transgenic zebrafish and esr2b knockout zebrafish.

This study found that in the early development of zebrafish, GnIH expression can be induced by estrogen. At the same time, it is the first to discover the negative regulatory role of esr2b on GnIH from the fourth day of zebrafish development. Considering the complexity of estrogen receptors, more esr knockout models may be needed in the future to explore the regulatory role of the estrogen signaling pathway on the early expression of GnIH.

5. Conclusions

In this study, Tg (GnIH: mCherry) and esr2b knockout zebrafish were used to explore the regulation between estrogen receptors and GnIH. Our work showed that the GnIH neuropeptide expression location overlaps with that of Hcrt at 36 hpf and 72 hpf. Estrogen treatment experiments showed that an appropriate dose of E2 is able to induce GnIH mRNA levels. High-dose E2 (50 μM) is not able to significantly induce GnIH mRNA levels. Esr2b knockout led to increased GnIH mRNA levels in zebrafish embryos and it started on the fourth day. In a word, estrogen receptors are able to regulate GnIH expression in the early zebrafish development stage. However the esr2b is involved in negative regulation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ani16030444/s1, File S1. The analysis of GnIH promoter sequence online(JASPAR database).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.P. and B.Z.; methodology, W.P. and Y.Z.; software, B.Z.; validation, W.P. and L.H.; formal analysis, W.P.; investigation, W.P.; resources, L.L.; data curation, W.P.; writing—original draft preparation, W.P.; writing—review and editing, W.P.; visualization, W.P.; supervision, B.Z.; project administration, W.P.; funding acquisition, B.Z. and W.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 31802277), the Hunan University of Arts and Science Research Project (Grant No. 24YB06), and the Excellent Youth Project of Hunan Education Department (Grant No. 23B0662).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Special Committee of Science Ethics, Academic Committee of Hunan University of Arts and Sciences (2022090733).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tsutsui, K.; Saigoh, E.; Ukena, K.; Teranishi, H.; Fujisawa, Y.; Kikuchi, M.; Ishii, S.; Sharp, P.J. A Novel Avian Hypothalamic Peptide Inhibiting Gonadotropin Release. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 275, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, K.; Ukena, K.; Satake, H.; Iwakoshi, E.; Minakata, H.; Tsutsui, K. Novel fish hypothalamic neuropeptide. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 6000–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osugi, T.; Ubuka, T.; Tsutsui, K. Review: Evolution of GnIH and related peptides structure and function in the chordates. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugars, G.; Pasquier, J.; Atkinson, C.; Lafont, A.-G.; Campo, A.; Kamech, N.; Lefranc, B.; Leprince, J.; Dufour, S.; Rousseau, K. Gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone in teleosts: New insights from a basal representative, the eel. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2020, 287, 113350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Cueto, J.A.; Paullada-Salmeron, J.A.; Aliaga-Guerrero, M.; Cowan, M.E.; Parhar, I.S.; Ubuka, T. A journey through the gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone system of fish. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Cao, M.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, W. GnIH plays a negative role in regulating GtH expression in the common carp, Cyprinus carpio L. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2016, 235, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Lu, D.; Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Cheng, C.H. Structural diversity of the GnIH/GnIH receptor system in teleost: Its involvement in early development and the negative control of LH release. Peptides 2010, 31, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubuka, T.; Ukena, K.; Sharp, P.J.; Bentley, G.E.; Tsutsui, K. Gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone inhibits gonadal development and maintenance by decreasing gonadotropin synthesis and release in male quail. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriegsfeld, L.J.; Mei, D.F.; Bentley, G.E.; Ubuka, T.; Mason, A.O.; Inoue, K.; Ukena, K.; Tsutsui, K.; Silver, R. Identification and characterization of a gonadotropin-inhibitory system in the brains of mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 2006, 103, 2410–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubuka, T.; Kim, S.; Huang, Y.C.; Reid, J.; Jiang, J.; Osugi, T.; Chowdhury, V.S.; Tsutsui, K.; Bentley, G.E. Gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone neurons interact directly with gonadotropin-releasing hormone-I and-II neurons in European starling brain. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric, D.; Anderson, G.M.; Herbison, A.E. RFamide-related peptide-3, a mammalian gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone ortholog, regulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron firing in the mouse. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 2799. [Google Scholar]

- Diotel, N.; Le Page, Y.; Mouriec, K.; Tong, S.K.; Pellegrini, E.; Vaillant, C.; Anglade, I.; Brion, F.; Pakdel, F.; Chung, B.C.; et al. Aromatase in the brain of teleost fish: Expression, regulation and putative functions. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 31, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovick, S.; Levine, J.E.; Wolfe, A. Estrogenic regulation of the GnRH neuron. Front. Endocrinol. 2012, 3, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couse, J.F.; Lindzey, J.; Grandien, K.; Gustafsson, J.A.; Korach, K.S. Tissue distribution and quantitative analysis of estrogen receptor-alpha (ERalpha) and estrogen receptor-beta (ERbeta) messenger ribonucleic acid in the wildtype and ERalpha-knockout mouse. Endocrinology 1997, 138, 4613–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, G.B.; Tremblay, A.; Copeland, N.G.; Gilbert, D.J.; Jenkins, N.A.; Labrie, F.; Giguere, V. Cloning, chromosomal localization, and functional analysis of the murine estrogen receptor beta. Mol. Endocrinol. 1997, 11, 353–365. [Google Scholar]

- Menuet, A.; Pellegrini, E.; Anglade, I.; Blaise, O.; Laudet, V.; Kah, O.; Pakdel, F. Molecular characterization of three estrogen receptor forms in zebrafish: Binding characteristics, transactivation properties, and tissue distributions. Biol. Reprod. 2002, 66, 1881–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.J.; Williams, M.J.; Kew, K.A.; Converse, A.; Thomas, P.; Zhu, Y. Reduced Vitellogenesis and Female Fertility in Gper Knockout Zebrafish. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 637691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Cui, Y.; Jiang, L.; Ge, W. Functional analysis of nuclear estrogen receptors in zebrafish reproduction by genome editing approach. Endocrinology 2017, 7, 2292–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Song, B.; Yang, P.; Liu, L. Developmental Delay and Male-Biased Sex Ratio in esr2b Knockout Zebrafish. Genes 2024, 15, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, L.B.; January, K.E.; Ho, K.W.; Cotter, K.A.; Callard, G.V. Morpholino-mediated knockdown of ERα, ERβa, and ERβb mRNAs in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos reveals differential regulation of estrogen-inducible genes. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 4158–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlicher, M.; Liedtke, A.; Groh, K.; López-Schier, H.; Neuhauss, S.C.; Segner, H.; Eggen, R.I. Estrogen receptor subtype beta2 is involved in neuromast development in zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae. Dev. Biol. 2009, 30, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, C.S.; Kalló, I.; Liposits, Z.; Hrabovszky, E. Estradiol down-regulates RF-amide-related peptide (RFRP) expression in the mouse hypothalamus. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 1684–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thisse, C.; Thisse, B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat. Protoc. 2001, 3, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauptmann, G. One-, two-, and three-color whole-mount in situ hybridization to Drosophila embryos. Methods 2001, 23, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, T. Double in Situ Hybridization Techniques in Zebrafish. Methods 2001, 23, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Peng, W.; Luo, J.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, W. Organization of the gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone (Lpxrfa) system in the brain of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2021, 304, 113722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessmar-Raible, K.; Raible, F.; Christodoulou, F.; Guy, K.; Rembold, M.; Hausen, H. Conserved Sensory-Neurosecretory Cell Types in Annelid and Fish Forebrain: Insights into Hypothalamus Evolution. Cell 2007, 129, 1389–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraco, J.H.; Appelbaum, L.; Marin, W.; Gaus, S.E.; Mourrain, P.; Mignot, E. Regulation of hypocretin (orexin) expression in embryonic zebrafish. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 29753–29761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.A.; Andrey, A.; Truong, T.V. Genetic and neuronal regulation of sleep by neuropeptide VF. Elife 2017, 6, e25727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardet, P.L.; Horard, B.; Robinson-Rechavi, M.; Laudet, V.; Vanacker, J.M. Characterization of oestrogen receptors in zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002, 28, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassiter, C.S.; Kelley, B.; Linney, E. Genomic structure and embryonic expression of estrogen receptor beta a (ERbetaa) in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Gene 2002, 299, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pikulkaew, S.; De Nadai, A.; Belvedere, P.; Colombo, L.; Dalla Valle, L. Expression analysis of steroid hormone receptor mRNAs during zebrafish embryogenesis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 165, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingaud-Sequeira, A.; André, M.; Forgue, J.; Barthe, C.; Babin, P.J. Expression patterns of three estrogen receptor genes during zebrafish (Danio rerio) development: Evidence for high expression in neuromasts. Gene Expr. Patterns 2004, 4, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouriec, K.; Gueguen, M.M.; Manuel, C.; Percevault, F.; Thieulant, M.L.; Pakdel, F.; Kah, O. Androgens upregulate cyp19a1b (aromatase B) gene expression in the brain of zebrafish (Danio rerio) through estrogen receptors. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 80, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menuet, A.; Pellegrini, E.; Brion, F.; Gueguen, M.M.; Anglade, I.; Pakdel, F.; Kah, O. Expression and estrogen-dependent regulation of the zebrafish brain aromatase gene. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005, 485, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coumailleau, P.; Pellegrini, E.; Adrio, F.; Diotel, N.; Cano-Nicolau, J.; Nasri, A.; Vaillant, C.; Kah, O. Aromatase, estrogen receptors and brain development in fish and amphibians. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Regul. Mech. 2014, 1849, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, N.D.; Srouji, S.S.; Histed, S.N.; Hall, J.E. Differential effects of aging on estrogen negative and positive feedback. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 301, E351–E355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, J.L.; Wise, P.M. The role of the brain in female reproductive aging. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 299, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.; Wolfe, A.; Novaira, H.J.; Radovick, S. Estrogen regulation of gene expression in GnRH neurons. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 303, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Criado, J.E.; de Las Mulas, J.M.; Bellido, C.; Navarro, V.M.; Aguilar, R.; Garrido-Gracia, J.C.; Malagon, M.M.; TenaSempere, M.; Blanco, A. Gonadotropin-secreting cells in ovariectomized rats treated with different oestrogen receptor ligands: A modulatory role for ERbeta in the gonadotrope? J. Endocrinol. 2006, 188, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Simerly, R.B. Wired for reproduction: Organization and development of sexually dimorphic circuits in the mammalian forebrain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 25, 507–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.