Simple Summary

The animal-assisted therapy (AAT) is a goal-oriented, planned, and structured treatment intervention directed and delivered by professionals. AAT is in the spotlight as a beneficial therapy for humans. However, there is a lack of research on this type of job or the education that these professionals should receive. This study aimed to analyze the job of the person executing AAT, design the curriculum, and provide discussions and suggestions for future research directions.

Abstract

This study analyzed the jobs of animal-assisted therapy specialists using the Development of a Curriculum (DACUM) technique, a job analysis method for the duties and tasks performed in a specific job. It derived nine duties and 54 tasks through a verification process. In addition, by analyzing the knowledge, skills, and attitudes according to the task, the duties of animal-assisted therapy specialists were derived with 37 knowledge points (K), 32 skills (S), and 46 attitudes (A). The curriculum was designed based on the results derived from the job analysis. The final derived subjects were “understanding the counselee”, “clinical practice”, “therapy-assisted animal management”, “case conceptualization”, “psychological test and evaluation”, “program development”, “understanding and practice of counseling psychology”, “animal-assisted intervention introduction”, “evaluation analysis and report”, “case study and practice”, “case guidance and management”, “training and behavior”, and “animal welfare”. These results can improve the professionalism of animal-assisted therapy specialists and the overall quality of the therapy site.

1. Introduction

Animal-assisted interventions (AAIs) have developed significantly over the past half century [1]. In 1950, child psychologist Boris Levinson discovered that using dogs to facilitate communication between therapists and patients could be beneficial for the treatment, which led Levinson to coin the term Pet Therapy in 1964 [2] and develop the Pet-Facilitated Psychotherapy and Pet-Oriented Child Psychotherapy theories [3]. Scientific and systematic animal-assisted therapy was initiated by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1988. According to a white paper by IAHAIO, the International Association of Human–Animal Interaction Organizations, AAIs are a goal-oriented and structured intervention that intentionally include or integrate animals into health, education, and services aimed at the therapeutic benefit of humans. Animal-assisted therapy (AAT), one of the subcategories of AAIs, is a goal-oriented, planned, and structured treatment intervention directed and delivered by a professional. Professionals performing AAT should have knowledge of animal behavior, needs, health indicators, and stress control, focusing on improving a particular subject’s physical, cognitive, behavioral, and socio-emotional functions [4]. AAT is being implemented in response to various symptoms and for different conditions, including autism [5,6,7], cognitive impairment and mobility [8], depression, anxiety [9], and dementia [10,11], and is being carried out in various environments, including mental health facilities [12,13], nursing homes [14,15], and hospitals [16]. Therefore, animal-assisted therapy specialists who perform AAT should be professionals with specialized knowledge in human physical, cognitive, behavioral, and social-emotional aspects and animal behavior, needs, health, and stress [4]. Despite the high level of expertise required for this job beyond simple interactions with animals, research on the duties performed by animal-assisted therapy specialists is still lacking.

The Developing a Curriculum (DACUM) technique is a job analysis method used to analyze the duties and tasks performed by a particular profession to develop a curriculum. The DACUM technique uses group interaction, synergy, and brainstorming. Compared to other techniques, it can be performed economically in a relatively short amount of time. This technique more systematically derives the characteristics of the job, knowledge, skills, and attitudes required through workshops with experienced experts [17,18,19]. DACUM was used to analyze jobs in various occupations, such as horticultural therapists (currently, welfare therapists) [20], occupational therapists [21], physical therapists [22], and forest prenatal care instructors [23] to increase job efficiency and professionalism by specifying and systematizing job contents. In addition, various occupations, such as nurses [24], professional counselors [25], and plant protection technicians [26], were analyzed through job analysis using DACUM to lay the foundation for these jobs and systematize them. All the jobs that were analyzed were newly created according to the trends of the times; thus, they tried to systematically operate them based on an understanding of and the evidence from actual work in the field through a job analysis. Currently, there are various definitions of animal-assisted interventions (AAIs), AAT, and animal-assisted education (AAE) in South Korea and abroad, and the problem is that they are inconsistent. In other areas, such as occupational therapy and physical therapy, all forms of intervention, including those that involve animals, are classified as animal-assisted therapy. This broad classification leads to potential problems because the corresponding programs can proceed with a lack of understanding of human–animal interactions and without evaluating animal behavior or temperament.

Currently, in South Korea, a degree or license is required to work as an animal-assisted therapy specialist, and individuals must undergo sufficient education. However, each institution implements programs with different names and contents, which are neither internationalized nor standardized. Consequently, a curriculum for actual activities in the field has not been developed. Moreover, there is a lack of research or data analysis on the duties of animal-assisted therapy specialists. This study aimed to analyze the duties of animal-assisted therapy specialists and design a curriculum using the DACUM technique. By enhancing the understanding of the role of animal-assisted therapy specialists through a job analysis, we anticipate improvements in the efficiency and quality of treatment in the clinical field, as well as in the professionalism of practitioners. Additionally, we expect the welfare of treatment-assisting animals and clients to improve.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. DACUM Commission

To form the DACUM committee, among the animal-assisted therapy specialists operating across the country, those with excellent technical work ability, job representation, communication ability, full-time work, and unbiased tendencies were selected as the panel according to the panel selection criteria [19]. Eight people were selected for the DACUM panel among ten candidates who agreed to participate. The workshop consisted of one professional analyst, one recorder, and one observer to help facilitate and analyze the workshop.

2.2. Process of DACUM Analysis

The schedule, location, time, and principles with which the panel had to comply were sent to the panelists by e-mail to familiarize them with DACUM. The workshop lasted for 10 h. In the first hour, an orientation was conducted through an analyst to enhance the panel’s understanding of the DACUM workshop. Seats were placed around the analyst such that everyone could see and talk to each other, and the recorder was placed in the seat closest to the analyst. Sticky walls were attached to the wall, and duties, tasks, knowledge, skills, and attitudes were separated by color and attached to the wall. The panel freely discussed their opinions and changed the position of the papers whenever their opinions were revised. The recorder recorded all the meeting contents in real time using a laptop, which were recorded for future review.

2.3. DACUM Analysis Verification Process

2.3.1. First Verification

The results derived from the DACUM workshop were sent to the panelists via e-mail and they were asked to review and provide suggestions for modifications about the duties, tasks, knowledge, skills, and attitudes. One week later, the revised DACUM chart was sent by e-mail for a second time, and the revised contents were returned two days later. Therefore, the first verification step was performed twice.

2.3.2. Second Verification

The animal-assisted therapy specialist DACUM chart, developed after two first-line validations, was sent to a three-member secondary validation committee, and a reply was received four days later. The second verification consisted mainly of working-level staff in the clinical field. This was performed to check whether there was a difference between the developed DACUM chart and the clinical field and to secure additional objective opinions.

2.4. Curriculum Derivation

To derive a curriculum for animal-assisted therapy specialists, three working-level staff members derived key tasks from the list of tasks and grouped the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for core tasks.

3. Results

3.1. The Definition of an Animal-Assisted Therapy Specialist

The definitions of animal-assisted therapy specialists derived from the DACUM workshop are presented. Among the various definitions derived, common terms were ‘animal’, ‘person’, ‘interaction’, ‘client analysis’, ‘psychotherapy intervention’, ‘environmental composition’, ‘adaptation’, ‘recovery’, ‘improvement’, ‘rehabilitation’, and ‘development’. Two rounds of verifications were conducted, and the definition of an animal-assisted therapy specialist was finally defined as “an expert who supports the psychological and emotional recovery, social adaptation, and development of the client through psychotherapy interventions using human–animal interactions”. Animal-assisted therapy specialists (Table 1) engage in psychotherapeutic interventions by interacting with animals with various subjects in various environments. After completing the curriculum set by each institution, they acquire qualifications and work in the clinical field.

Table 1.

Animal-assisted therapy specialist definition.

3.2. Duties and Tasks

Through the DACUM workshop and the two rounds of verifications, the animal-assisted therapy specialists’ duties and tasks were finally defined (Table 2). The duties were divided into nine categories: securing counselors, identifying service users, designing programs, conducting counseling, evaluating counseling, follow-up management, developing therapy specialist competency, managing therapy specialists, developing new programs, and analyzing 54 tasks.

Table 2.

Duties and tasks.

In <A. Securing Counseling Resources>, the following steps are implemented: identify the type of service user, consult on the counseling site, identify the physical environment of the counseling site, guide institutional users, and adapt treatment-assisting animals to the counseling site. To <B. Check the Service Users>, therapists should consult with institutions and individuals and conduct reception interviews. A counseling strategy is established after conducting psychological tests and conceptualizing the case. <C. Program Design> investigates the appropriate program for the client and selects the appropriate program format. The therapist selects treatment-assisting animals, determines their duties, and establishes a physical environment that considers the clients and animals. Subsequently, a suitable program for the client is designed. In <D. Progress Consultation>, the counseling environment is checked, and the condition of the treatment-assisting animal is checked before the session. After explaining animal-assisted therapy to the service users and obtaining their consent, a relationship is formed between the client, AAT specialist, and animal and they engage in psychotherapy interventions. Different physical environments should be provided according to changes in circumstances, and measures should be taken to check stress signals from treatment-assisting animals. All session processes should be documented, and conclusions should be discussed at the end of the session. In <E. Evaluation of counseling>, the consultation results are evaluated, and a result report is prepared. In <F. Follow-Up Management>, the client’s current status is identified, and additional counseling is decided. In addition, the results of follow-up management are documented. In <G. Development of the AAT Specialist Competency>, therapists learn the latest information in related fields, receive supervision, and participate in case-study meetings. They attend academic meetings and publish case results in academic journals. AAT specialists should have self-awareness and self-care skills; also, they must engage in self-promotion and marketing. In <H. Therapy-Assisting Animal Care>, the characteristics of treatment-assisting animals must be identified, and treatment-assisting animals must be educated and certified. Additionally, veterinary management and animal welfare must be practiced throughout all processes. Therefore, management plans for retirement of treatment-assisting animals should be established . In <I. Development of New Programs>, first, service users are analyzed, and then the purpose and goal of the program are set. A program suitable for service users is also developed by collecting and analyzing prior programs. The program’s validity is checked, implemented, and applied. The results are analyzed and their significance is checked. The program is revised and reviewed, and the development plan is documented. Animal-assisted therapy specialists who know their job will provide high-quality treatment services to clients and have a systematic structure for carrying out the work. In addition, the welfare and well-being of treatment-assisting animals, which are partners who work together with the therapist, can be improved through <H. Therapy-Assisting Animal Care>, which are areas that can be missed due to a focus on clients.

3.3. Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes

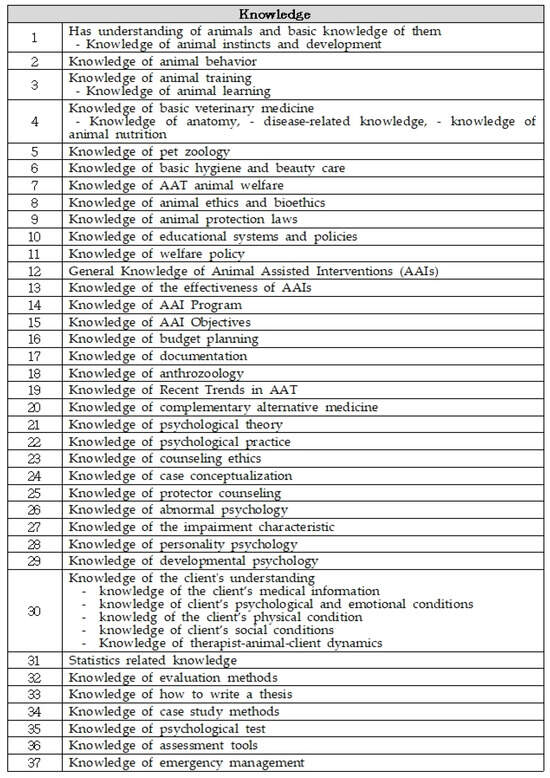

Knowledge (K), skills (S), and attitudes (A) define the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to perform each task. Knowledge is defined as the principles one needs to know to perform the job, such as understanding the basics of animal behavior, training, basic veterinary medicine, companion animal science, basic hygiene, AAT animal welfare, animal ethics and bioethics, animal protection laws, education systems and policies, welfare policies, general knowledge of animal-assisted interventions, knowledge of the effectiveness of AAIs, knowledge of AAI programs, knowledge of AAI objectives, budget planning, documentation, human zoology, recent trends, complementary medicine, psychological theory, psychological reality, counseling ethics, case conceptualization, guardian counseling, abnormal psychological psychology, developmental psychology, clients’ understanding, statistics, evaluation methods, thesis writing, case study methods, psychological tests, evaluation tools, and emergencies.

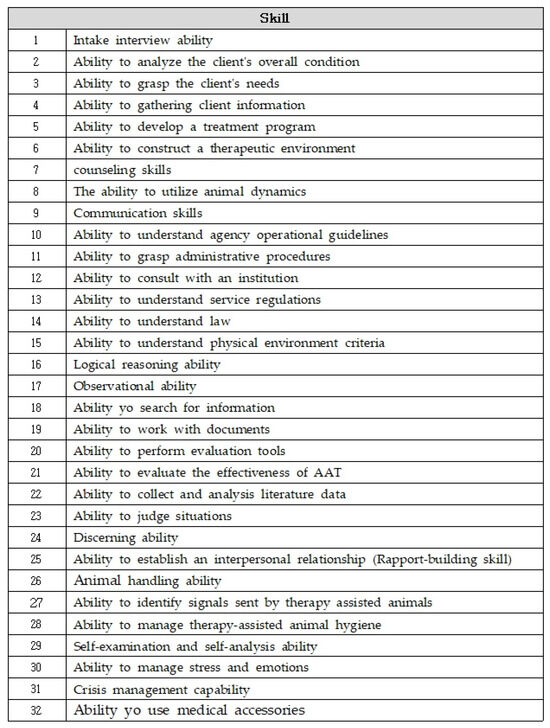

Skills refer to personality traits, psychological skills, and basic postures that must be used to perform a task. They are derived from the reception interview ability, client analysis ability, client information collection ability, treatment program development ability, therapeutic environment construction ability, counseling technique ability, animal dynamic utilization ability, administrative procedure ability, consultation ability, service regulation identification ability, physical environment standard identification ability, logical thinking ability, observation ability, work documentation ability, ability to use evaluation tools, literature data collection and analysis ability, ability to forms insight, handling ability, treatment-assisting animal health and hygiene management ability, self-reflection and self-analysis ability, AAT specialist stress and emotion management ability, crisis management ability, medical aid ability, and auxiliary device operation ability.

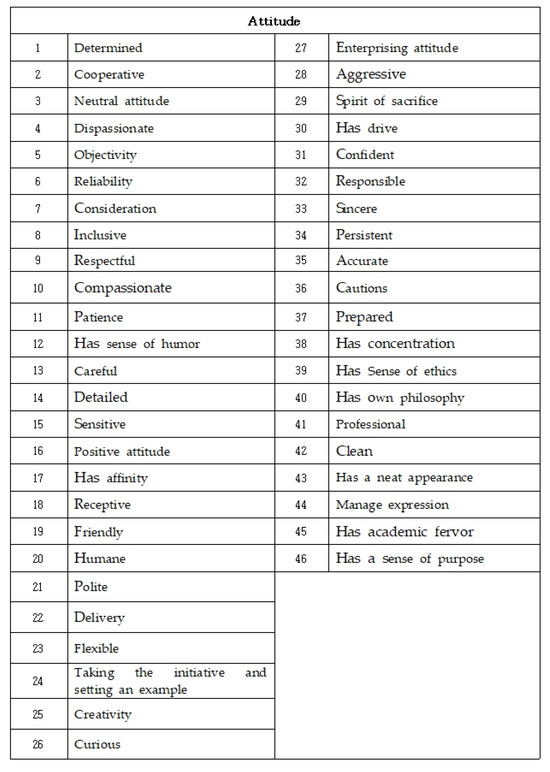

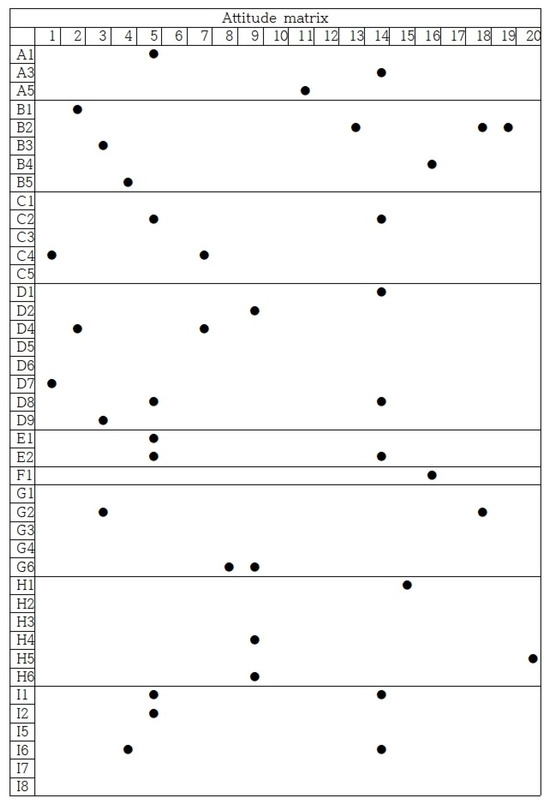

Attitudes are states of preparation for a response to an object based on individual perceptions and emotions. Attitudes refer to internal tendencies to react, even if they do not result in actual actions. The attitudes were defined as determined, cooperative, neutral, dispassionate, objective, reliable, thoughtful, broad-minded, gives unconditional regard, honest, provides careful concern, kind, patient, humorous, gentle, careful, sensitive, detailed, has a positive attitude, has affinity, receptive, friendly, humanity, courteous, affirmative, has transmissibility, flexible, pliable, takes the initiative and sets an example, creativity, curiosity, adventurous, progressive, has a positive mindset, self-sacrificing, leadership, trustworthy, confident, has a sense of duty, responsible, sincere, tenacious, accurate, careful, prepared, concentrated, ethical, has their own philosophy, professional, clean, has a neat appearance, manages expression, has academic fervor, and has a sense of purpose. Through the two rounds of verifications, 37 knowledge points (K), 32 skills (S), and 46 attitudes (A) were identified (Table 3).

Table 3.

Knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

3.4. Curriculum Design

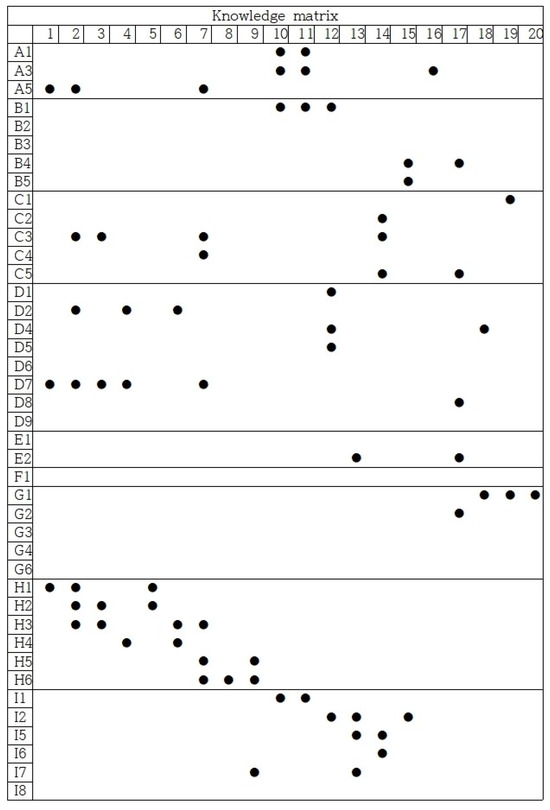

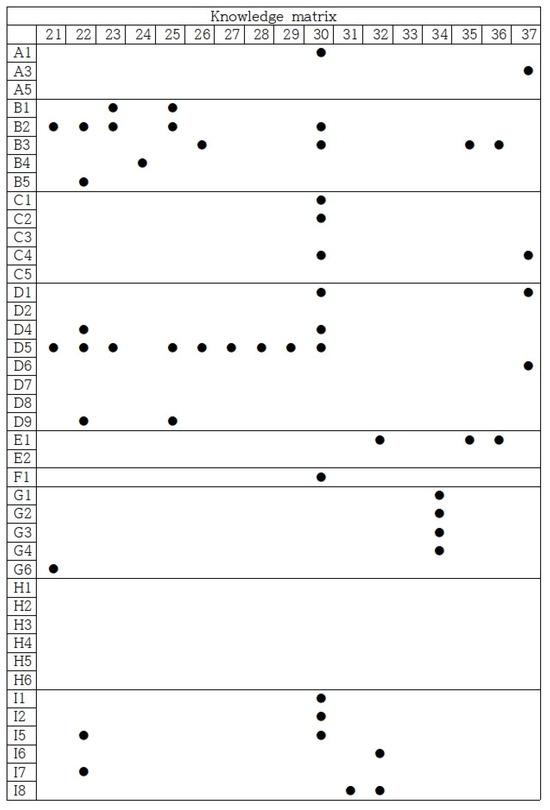

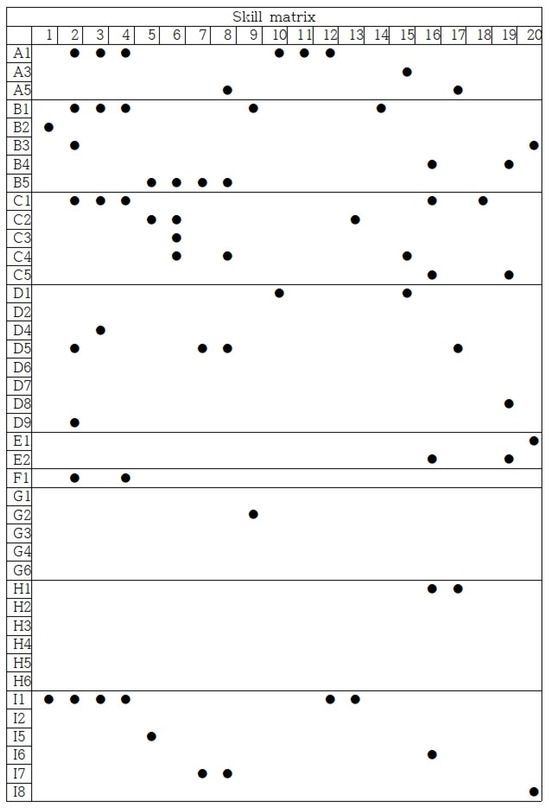

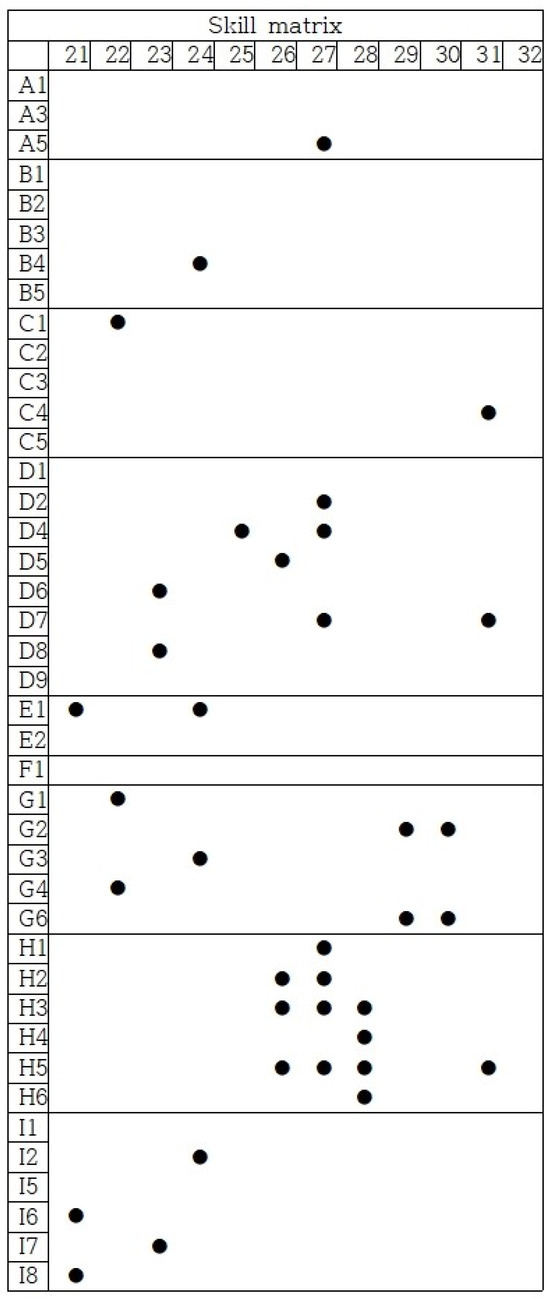

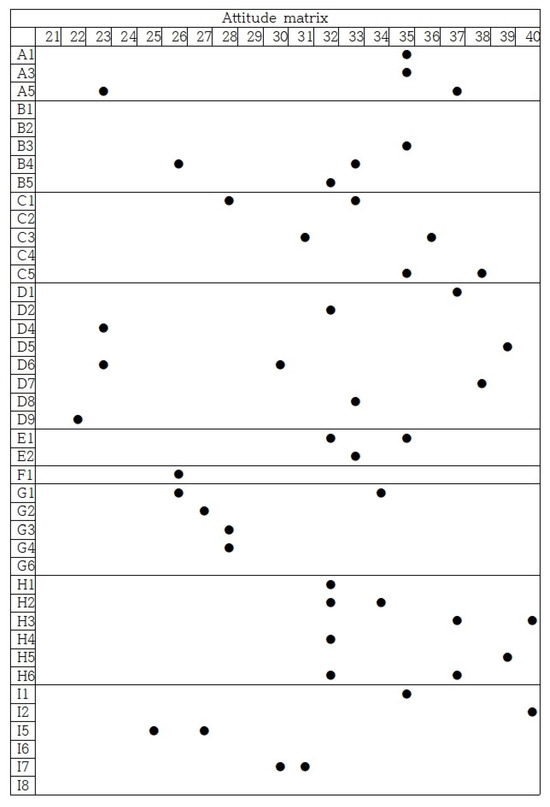

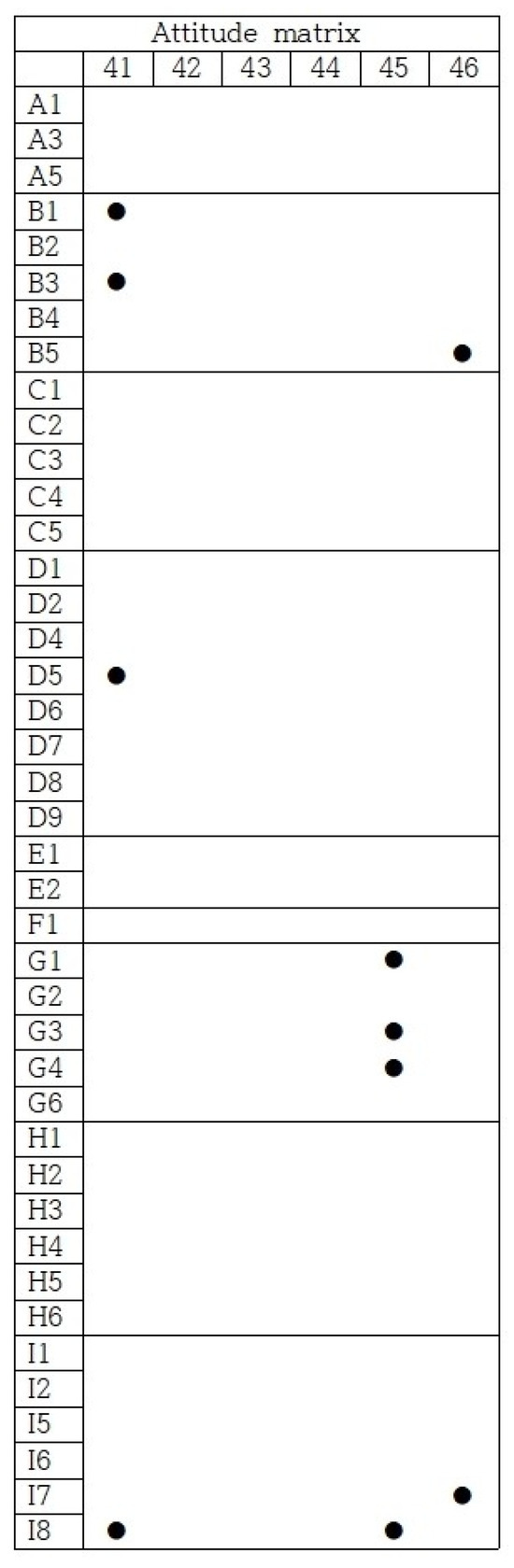

The knowledge, skills, and attitudes suitable for the key tasks were converted into a matrix (Figure 1), and the subjects necessary for the core tasks were derived. The knowledge, skills, attitudes were cross-referenced against the duties and tasks identified in Table 4.

Figure 1.

Knowledge, skills, and attitudes matrix. The black dots indicate the intersections between the KSA and DACUM charts.

Table 4.

Subjects of core courses.

A total of 13 subjects were derived: “Understanding Counselee”, “Clinical Practice”, “Therapy-Assisting Animal Management”, “Case Conceptualization”, “Psychological Test and Evaluation”, “Program Development”, “Introduction to Animal-Assisted Interventions”, “Counseling and Understanding Psychology ”, “Evaluation Analysis and Reporting”, “Case Research and Practice”, “Case Guidance and Management”, “Training and Behavior”, and “Animal Welfare”.

3.5. Derivation of Curriculum Subjects

Based on the curriculum designed in Table 5, a further refinement was conducted to design the main content. Three experts from the field were involved in this task, and the results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Curriculum and main content.

3.6. Curriculum Comparative Analysis

Using the main content outlined in Table 6 as a foundation, we conducted a thorough comparative analysis with the European Qualifications Framework (EQF) established by the International Society for Animal-Assisted Therapy (ISAAT) [27], a guideline endorsed by IAHAIO. In this analysis, we meticulously assessed the learning topics, learning outcomes, knowledge, and competencies outlined within the EQF, juxtaposing them with the core content developed through this study. This comparative approach aimed to pinpoint any divergences between the two frameworks, thereby providing insights into the strengths and potential areas for improvement in each.

Table 6.

The comparison between the developed curriculum and the EQF.

4. Discussion

In South Korea, animal-assisted therapy was introduced in the early 2000s. However, due to a lack of data on the duties of animal-assisted therapy specialists, it has been difficult to grasp the specific responsibilities of these professionals. Therefore, in this study, the duties of animal-assisted therapy specialists were analyzed through the DACUM technique, and as a result of the job analysis, it was finally determined that animal-assisted therapy specialists have 9 duties and 53 tasks, and need 37 knowledge points (K), 32 skills (S), and 47 attitudes (A) to perform their duties.

The contents of the duties and tasks of animal-assisted therapy specialists were defined as <A. Securing a Counselor>, <B. Service User Identification>, <C. Program Design>, <D. Consultation Progress>, <E. Consultation Evaluation>, <F. Follow-Up Management>, <G. AAT Specialist Competency Development>, <H. Treatment-Assisting Animal Management>, and <I. New Program Development>. The process includes identifying the service users, conducting psychological tests, case conceptualization, collecting counseling strategies, program design, understanding the clients, selecting a program format suitable for the characteristics of the client, conducting counseling, conducting psychotherapy interventions, and performing duties covering all matters related to treatment mediators. The results are consistent with the definition [4] that therapists should focus on improving the physical, cognitive, behavioral, and social–emotional functions of a particular subject and should have knowledge of animal behavior, needs, health indicators, and stress control.

The above findings will be helpful for practitioners to accurately understand their roles and enhance their professionalism since they provide practical knowledge that can be directly applied in real-life situations by animal-assisted therapy specialists. Moreover, they will serve as guidelines for these specialists to grow into experts in the field by identifying the knowledge that is actually needed. This will play a crucial role in improving the competence of practitioners and enhancing the quality of AAT.

Using a DACUM analysis, the job analysis results for forest prenatal care instructors [23], occupations belonging to complementary and alternative medicine, were <A. Understanding Forest Prenatal Care Subjects>, <B. Cultivating Forest Prenatal Care Professional>, <C. Operation of Forest Prenatal Care Program>, <D. Self-Development> and for horticultural therapy practitioners [20], they were <A. Decide on Horticultural Treatment Implementation Institution>, <B. Diagnosis and Assessment of Horticultural Treatment Subjects>, <C. Planning Horticultural Treatment Program>, <D. Preparation for Implementing Horticultural Treatment Activities by Session>, <F. Conducting Horticultural Treatment Activities by Session>, <G. Conducting Comprehensive Evaluation of Horticultural Treatment>, and <H. Self-Development as a Horticultural Therapy Practitioner>, which can be seen as having similar structures. However, this is different from previous studies in that one of the major characteristics was the addition of management of treatment mediators, counseling evaluation for clients, follow-up management, and the development of new programs. These were derived by highlighting the importance of duties rather than belonging to tasks, and duties and tasks were subdivided according to the order and process of the job, unlike research in similar occupations. Based on the results of the job analysis, horticultural therapists were used as basic data for the standards and educational content of the qualification process, and prenatal forest healers also laid the foundation for the development of curriculum subjects through a job analysis. In the case of occupational therapists [21], the job analysis provided basic data for expanding the domestic occupational therapy area and developing and improving the curriculum. Therefore, based on this study, the current and future application plans for the job analysis results of animal-assisted therapists are as follows: to complete the responsibilities and tasks of animal-assisted therapists working in the clinical field, there is a need for continuous additional education so that current animal-assisted therapists can maintain their qualifications and improve their professional competencies considering recent trends and knowledge. Kim Soo-yeon et al. [20], after conducting a job analysis of horticultural therapists using DACUM, conducted a survey on horticultural therapists nationwide over the past decade to evaluate their current performance and future needs and analyzed their educational needs. Therefore, job performance evaluation and addressing educational needs, such as the research methodology of horticultural therapists [20], are currently considered difficult tasks because of the lack of active personnel despite numerous qualification systems (around 40) operating for animal-assisted therapy specialists. Therefore, if the number of animal-assisted therapy specialists working in the actual clinical field increases in the future, it will be necessary to revise and supplement responsibilities, tasks, knowledge, and technical attitudes through research, including surveys, to identify the actual conditions and needs of AAT specialists working in the field and reorganize them through a job analysis according to the qualification level.

In the design of the educational curriculum, a comparative analysis was conducted with the European Qualifications Framework (EQF) of the International Society for Animal-Assisted Therapy (ISAAT). The EQF is structured in an open format to accommodate different learning needs based on the learners’ experiences and educational backgrounds. It is divided into knowledge, skills, and competencies to fulfill learning of different topics according to the learning domain. When comparing and analyzing the educational content developed in this study with the EQF, it was found that “clinical practice”, “case conceptualization”, and “psychological test and evaluation” were identified as the main additions. The fact that not only the basic theories are included, but also a certain period of clinical practice is required before engaging with clients, and that after conducting case conceptualization and psychological assessments with clients, AAT should be conducted, indicates a further advancement from traditional AAT. This seems to be a result of the evolving awareness that clients need to be analyzed more intricately before conducting AAT, and thus requiring a more specialized approach. Furthermore, the emphasis on evaluating AAI programs from the perspective of program development in the educational curriculum underscores the importance of accurately assessing whether meaningful changes occurred for clients after undergoing AAT. Another noteworthy aspect is that, in “Animal Welfare”, it is not only about overall animal welfare but students are also separately educated on the welfare of therapy-assisting animals, which serve as therapeutic aids. In AAT, therapy-assisting animals work together in a triangular relationship with AAT professionals and clients. The emergence of a separate subject dedicated to the welfare of therapy-assisting animals suggests that their welfare is deemed as important as that of humans. This underscores the significance of therapy-assisting animal welfare in AAT.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study may help current or prospective animal-assisted therapy specialists understand their roles and contribute to the advancement of the field. Animal-assisted therapy specialists receive training through various curricula. To enhance their competencies, improve animal welfare, and elevate the quality of therapy, tailored education for animal-assisted therapy specialists is necessary.

Through this study, as curricula are developed, there is a need to establish a framework that aligns with them. The duties, tasks, knowledge, skills, and attitudes of animal-assisted therapy specialists have been identified. Therefore, this study is significant in real-life settings by providing essential knowledge and tools for animal-assisted therapy, making it highly relevant in practical contexts. However, since it is not possible to cover all the duties of animal-assisted therapy specialists, a more detailed job analysis in the future would be beneficial.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J.C. and J.S.H.; methodology, S.J.C. and J.S.H.; data curation, S.J.C. and J.S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J.C. and J.S.H.; writing—review and editing, S.J.C. and J.S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Committee on Bioethics (IRB) of Konkuk University (7001355-202403-HR-769).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the research participants for their valuable input.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fine, A.H.; Beck, A.M.; Ng, Z. The state of animal-assisted interventions: Addressing the contemporary issues that will shape the future. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levinson, B.M.; Mallon, G.P. Pet-Oriented Child Psychotherapy; Charles C Thomas Publishing Limited: Springfield, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, A.H. Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Foundations and Guidelines for Animal-Assisted Interventions; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, L.; Gee, N.R. Recognizing and mitigating canine stress during animal assisted interventions. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London, M.D.; Mackenzie, L.; Lovarini, M.; Dickson, C.; Alvarez-Campos, A. Animal assisted therapy for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Parent perspectives. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 4492–4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijker, C.; Leontjevas, R.; Spek, A.; Enders-Slegers, M.J. Effects of dog assisted therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorder: An exploratory randomized controlled trial. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 2153–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijker, C.; Leontjevas, R.; Spek, A.; Enders-Slegers, M.J. Process evaluation of animal-assisted therapy: Feasibility and relevance of a dog-assisted therapy program in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Animals 2019, 9, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigo-Claverol, M.; Malla-Clua, B.; Marquilles-Bonet, C.; Sol, J.; Jové-Naval, J.; Sole-Pujol, M.; Ortega-Bravo, M. Animal-assisted therapy improves communication and mobility among institutionalized people with cognitive impairment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, N.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, L. Effects of animal-assisted therapy on hospitalized children and teenagers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 60, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peluso, S.; De Rosa, A.; De Lucia, N.; Antenora, A.; Illario, M.; Esposito, M.; De Michele, G. Animal-assisted therapy in elderly patients: Evidence and controversies in dementia and psychiatric disorders and future perspectives in other neurological diseases. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2018, 31, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimova, B.; Toman, J.; Kuca, K. Effectiveness of the dog therapy for patients with dementia—A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, S.B.; Dawson, K.S. The effects of animal-assisted therapy on anxiety ratings of hospitalized psychiatric patients. Psychiatr. Serv. 1998, 49, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Haire, M.E. Animal-assisted intervention for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic literature review. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 1606–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosi, C.; Zaiontz, C.; Peragine, G.; Sarchi, S.; Bona, F. Randomized controlled study on the effectiveness of animal-assisted therapy on depression, anxiety, and illness perception in institutionalized elderly. Psychogeriatrics 2019, 19, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veilleux, A. Benefits and challenges of animal-assisted therapy in older adults: A literature review. Nurs. Stand. 2021, 36, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germone, M.M.; Gabriels, R.L.; Guérin, N.A.; Pan, Z.; Banks, T.; O’Haire, M.E. Animal-assisted activity improves social behaviors in psychiatrically hospitalized youth with autism. Autism 2019, 23, 1740–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, R.E. DACUM Handbook. Leadership Training Series No. 67; Center on Education and Training for Employment, College of Education, The Ohio State University: Columbus, Ohio, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- DeOnna, J. DACUM: A versatile competency-based framework for staff development. J. Nurs. Staff. Dev. 2002, 18, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, I.K.; Choi, J.I. Education Program. Development Methodology; Hakjisa: Seogyo-dong, Republic of Korea, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Park, S.-A.; Son, K.-C.; Lee, C. Horticultural therapy: Job analysis, performance evaluation, and educational needs. Korean J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2014, 32, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yong, J.H.; Choi, H.S.; Jeong, W.M.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, H.Y.; Cho, B.Y.; Hong, S.P. Job analysis of Korean occupational therapists based on the DACUM method. J. Korean Soc. Occup. Ther. 2011, 19, 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.; Song, Y.; Lee, K.; Hwang, R.; Lee, J.; Moon, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, G.; Choi, Y. Job analysis of Korean physical therapists based on the DACUM method. J. Korean Phys. Ther. Sci. 2011, 18, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I.; Kim, S.; Bang, K.; Yi, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, D.; Jang, S. Job analysis and curriculum development for forest healing instructor in charge of forest taegyo based on DACUM. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2020, 24, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Lee, I.; Choo, J.; Noh, S.; Park, H.; Gweon, S.; Lee, k.; Kim, K. Job analysis of visiting nurses in the process of change using FGI and DACUM. J. Korean Acad. Community Health Nurs. 2022, 33, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Jo, N. Job analysis of school counselor using DACUM method. J. Korean Teach. Educ. 2010, 27, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, K.J. The Subjects for Examination and Criteria for Preparation of Test Questions of the Engineer Plant Protection Qualifications Developed by DACUM. J Korean Soc. People Plants Environ. 2012, 15, 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- International Society for Animal Assisted Therapy. Draft Framework Curriculum. Available online: https://isaat.org/standards/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).