Abstract

Peracetic acid (PAA) has strong biocidal activity against bacteria, fungi, and spores, even with short contact times. PAA-mediated sterilization is therefore an attractive method for sterilization of growth media that have heat-labile components or when polymer-based equipment is used. However, residual PAA and co-existing hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) can inhibit the growth of cultivated species, necessitating a fast and reliable quenching strategy that does not require rinsing. In contrast to Fe–EDTA-based catalytic decomposition that is strongly influenced by pH, buffers, and organic nitrogen, we demonstrate a fundamentally different, stoichiometric quenching strategy using sodium dithionite that enables instantaneous and selective removal of PAA. Na2S2O4 preferentially reduced PAA over H2O2 in a 0.03% PAA solution and achieved complete PAA reduction within 5 s, independent of pH and in the presence of nitrogen compounds. By adjusting the Na2S2O4 dose, PAA could be selectively removed while allowing a small fraction of H2O2 to remain. When applied to the cultivation of Euglena gracilis, which tolerates low levels of H2O2, the PAA–Na2S2O4-treated medium resulted in greater cell growth and higher paramylon production than autoclaved medium.

1. Introduction

Euglena is a genus of unicellular, photosynthetic, flagellated eukaryotes that mostly inhabit freshwater environments. E. gracilis can produce a variety of high-value compounds, such as paramylon starch, making it potentially valuable as a sustainable next-generation biotechnology platform [1,2]. In addition, biomass from E. gracilis can be used as a source of digestible proteins, unsaturated fatty acids, vitamins, and antioxidant compounds for the food and pharmaceutical industries [3,4,5,6,7]. Euglena-based systems can also couple CO2 fixation with nutrient removal from wastewater as part of a resource-circulating process and have potential use for the environmentally friendly production of biodiesel and the sustainable production of aviation fuel precursors [8,9].

The stable and reproducible manufacture of these high-value products requires axenic cultivation to prevent nutrient competition and metabolic interference by contaminating microorganisms [10]. Although autoclaving at high temperature and high-pressure is a common method of sterilization, it cannot be used with growth media and equipment that is heat-sensitive and it requires substantial energy when performed at a large scale [11,12,13]. Chemical sterilization is an important alternative, because it can be applied to heat-sensitive media and equipment [14,15,16,17,18,19]. Chemical sterilization commonly uses agents such as H2O2, NaClO, Ca(ClO)2, and peracetic acid (PAA), but these agents require careful handling and proper disposal and frequently necessitate labor-intensive rinsing with sterilized water to remove residual disinfectant prior to cell inoculation [14,20,21,22].

To address these issues, recent approaches have moved toward integrated chemical sterilization–neutralization strategies that enable concurrent sterilization of the culture medium and cultivation system. PAA has strong and broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against bacteria, fungi, spores, and even some biofilms after short contact times [15,16,18,19,23], and it can be decomposed and neutralized via ferric ion (Fe3+)-mediated reactions. Building on this principle, previous researchers who used a polymer-based bioreactor and glucose-containing medium performed simultaneous sterilization with PAA and neutralization via Fe-EDTA-mediated PAA decomposition/neutralization (hereafter, Fe-EDTA-mediated decomposition) in HEPES buffer [15,16,18,19]. This integrated sterilization–neutralization approach enabled mono-cultivation without washing or filtration and led to a higher biomass yield than conventional thermal sterilization. However, Fe–EDTA mediated PAA decomposition relies on metal-catalyzed Fe(III)/Fe(II) redox cycling, which requires tightly controlled conditions such as near-neutral pH, buffering, and stable iron speciation. In practical cultivation media, however, these requirements are difficult to satisfy due to complex organic and inorganic constituents that perturb iron chemistry, making the process highly sensitive to medium composition and limiting its applicability across diverse microorganisms. Sodium dithionite (Na2S2O4) exists as the dithionite ion (S2O42−) in aqueous solution and functions as a strong and rapid reducing agent [24,25]. Under diverse conditions, dithionite can generate highly reactive species that rapidly reduce and deactivate oxidizing compounds, such as PAA and H2O2.

The purpose of this study of E. gracilis was to determine the optimal dose of Na2S2O4 needed to rapidly and completely neutralize PAA-sterilized media without using Fe-EDTA-mediated decomposition or any additional reactions. We also examined the effect of medium conditions (pH, HEPES buffer, EDTA, and organic nitrogen) on the rapid Na2S2O4-mediated decomposition of PAA. We hypothesize that the differential reactivity of Na2S2O4 toward PAA and H2O2 and Euglena’s high tolerance to H2O2 will enable selective quenching of PAA at a moderate concentration of Na2S2O4, so that any residual Na2S2O4 does not inhibit Euglena growth. We also determined whether any reaction byproducts that formed during the PAA-Na2S2O4 neutralization reaction affected cell growth and paramylon production relative to control cells that were grown in autoclaved medium.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

PAA (20%) was from Dong Myung ONC Corp. (Busan, Republic of Korea) and sodium dithionite (83.0%) was from Daejung Chemicals & Metals Co., Ltd. (Siheung, Republic of Korea). Working solutions were prepared using triple-distilled water. Chemicals used in the growth medium are described below.

2.2. Instrumentation

Fixed-wavelength absorption measurements at 400, 515, and 680 nm were acquired using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (V-760, JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) with a 10 mm cell. The pH was measured using a digital pH meter (Mettler-Toledo InLab Ultra Micro-ISM, Greifensee, Switzerland). A colorimetric test strip (Peroxide Test Indicator, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was used to verify the decomposition of PAA by Na2S2O4.

2.3. Colorimetric Determination of PAA and H2O2

PAA solutions are typically present as an equilibrium mixture of PAA (CH3COOOH), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), acetic acid (CH3COOH), and water. The concentrations of PAA and H2O2 in PAA solutions were determined by a DPD/iodide colorimetric assay and a TiO-Ox colorimetric assay [26], respectively. Based on the commonly reported performance of the DPD/iodide colorimetric assay, the LOQ (limit of quantification) was approximately 0.00000025% (w/v) for PAA. Likewise, for the TiO-Ox colorimetric assay used for H2O2 determination, the LOQ was approximately 0.00000127% (w/v) [26].

2.4. Effect of Glucose on Degradation of PAA and H2O2 by Fe-Mediated Catalysis

Our previous study described the Fe-EDTA-mediated decomposition of PAA, in which HEPES was required to maintain pH and ensure complete degradation of peroxide species [19]. Thus, the effect of glucose on the complete decomposition of peroxide in the absence of HEPES was examined herein. A 0.03% PAA solution was prepared by diluting a 20% PAA stock solution with distilled water. A FeCl3-EDTA stock solution (96 mM FeCl3 and 96 mM EDTA) was then added to the 0.03% PAA solution that contained 0 or 20 g/L glucose to achieve a final FeCl3-EDTA concentration of 96 μM. The pH was then adjusted to approximately 7.0 using 5 M NaOH. Then, changes in the concentrations of PAA and H2O2 in the 0.03% PAA solution were monitored for 48 h using redox reaction-based colorimetric methods [26].

2.5. Effect of Peptone on Fe-EDTA-Mediated Degradation of PAA and H2O2

The Fe-EDTA-mediated decomposition of PAA can be inhibited by organic nitrogen compounds, such as peptone. To determine the effect of peptone on PAA decomposition in the presence of glucose, 5 g/L peptone was added to the 0.03% PAA solution that contained 20 g/L glucose. During the Fe-catalyzed conditions, changes in the concentrations of PAA and H2O2 were monitored for 48 h using colorimetric methods [26].

2.6. Decomposition of PAA by Reaction with Na2S2O4

A PAA solution contains PAA and H2O2, and Na2S2O4 reduces the PAA to acetic acid and the H2O2 to water. To determine the Na2S2O4 concentration required to completely reduce PAA and H2O2 in a 0.03% PAA solution, a 0.8 M Na2S2O4 stock solution was added to a 0.03% PAA solution to achieve a final Na2S2O4 concentration of 2.4, 4.8, 7.2, 9.6, or 12.0 mM (The Na2S2O4 concentration that is stoichiometrically equivalent to 0.03% PAA is approximately 4 mM). Then, residual PAA and H2O2 were quantified using colorimetric methods [26].

2.7. Rapid Na2S2O4-Mediated Decomposition of PAA Under Different Medium Conditions (pH, HEPES Buffer, EDTA, and Organic Nitrogen)

When a solution contains organic nitrogen, the Fe-EDTA-mediated decomposition of PAA is delayed, regardless of the presence of glucose or HEPES [16]. Therefore, the rapid Na2S2O4-mediated quenching of PAA was practically examined under Euglena growth medium conditions (see Section 2.9) in the presence of peptone. Briefly, Euglena growth medium containing 5 g/L peptone was sterilized with 0.03% PAA and subsequently treated with 9.6 mM Na2S2O4 to confirm complete neutralization of all PAA-derived peroxides. The presence of residual peroxides was assessed after 5 s using a Peroxide Test Indicator (Merck). In addition, we evaluated whether Na2S2O4 could completely quench a 0.03% PAA solution under various pH conditions (3, 5, 7, 9, and 11) and the presence of HEPES buffer or EDTA in Euglena medium.

2.8. Tolerance of Cells to Residual Na2S2O4

To evaluate the concentration-dependent cytotoxicity of Na2S2O4, a 0.8 M Na2S2O4 stock solution was added to actively motile cultures of E. gracilis to achieve final Na2S2O4 concentrations of 0.008, 0.016, 0.024, 0.032, or 0.040 mM. Changes in cellular activity were assessed after 5 min.

2.9. Cultivation of Cells

E. gracilis UTEX367 was purchased from the UTEX Culture Collection of Algae (Austin, TX, USA). The growth medium consisted of (g/L) NH4Cl—1, MgSO4·7H2O—0.1, CaCl2·2H2O—0.05, NaH2PO4—0.05, K2HPO4—0.05, Na2EDTA·2H2O—0.05, ZnSO4·7H2O—0.022, H3BO3—0.011, MnCl2·4H2O—0.005, FeSO4·7H2O—0.005, CoCl2·6H2O—0.0016, CuSO4·5H2O—0.0016, and (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O—0.0011. The growth factors (vitamins) were added at the following concentrations (mg/L): thiamine—0.01, biotin—0.002, cyanocobalamin—0.001, and pyridoxine—0.001.

Sodium acetate (10 g/L) was the primary source of organic carbon. Four cultivation conditions were established based on the presence of acetate (+Ac, −Ac) and the type of sterilization (PAA, autoclaving): (i) +Ac/PAA-sterilized, (ii) −Ac/PAA-sterilized, (iii) +Ac/autoclaved, and (iv) −Ac/autoclaved. For PAA sterilization, the PAA concentration was adjusted to 0.03%, and the medium was added to 500 mL T-flasks (GVS, Bologna, Italy) for 24 h. PAA was then completely quenched by adding Na2S2O4 (final concentration 7.2 mM), followed by adjustment of pH to approximately 7.0 using 5 M NaOH to provide pH conditions favorable for Euglena growth, and then inoculation with E. gracilis. The autoclaved control consisted of sterile growth medium that was autoclaved at 121 °C for at least 20 min. Cells were grown in the 500 mL T-flasks under agitation at 70 rpm and 25 °C, with continuous illumination from a flat LED panel that had a photosynthetic photon flux density of 50 µmol photons m−2 s−1. The growth of cells was monitored at 2-day intervals by measurement of OD680nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer spectrophotometer (V-760, JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) with a 10 mm glass cuvette. Each result was expressed as the mean and standard deviation of four replicates.

2.10. Determination of Paramylon

The paramylon content was measured using a gravimetric method [27]. First, 50 mg of a freeze-dried sample of cells was suspended in 5 mL of acetone to remove the chlorophyll, and the cells were then lysed by sonication for 30 min. The sample was then suspended in acetone and sonicated as above, centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min, suspended in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to remove substances other than paramylon, and boiled at 100 °C for 30 min. The samples were then cooled to room temperature, boiled in SDS a second time, and then washed twice in distilled water. Finally, the sample was transferred to a 1.5 mL microtube and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was dried overnight at 80 °C and then weighed. The paramylon content (%) was expressed relative to dry cell weight. Each result was expressed as the mean and standard deviation of three replicates.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical Analysis System software SAS version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Group differences were determined by a one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s test. A p-value below 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Glucose-Enhanced Fe-Catalyzed Decomposition of PAA

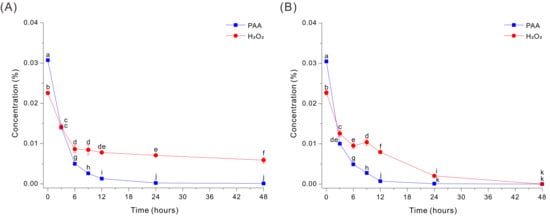

In the absence of HEPES, the Fe-EDTA-mediated decomposition of PAA in the 0.03% PAA solution at pH 7 was very rapid, but the level of H2O2 decreased more slowly and remained at appreciable levels even after 48 h (Figure 1A). Specifically, PAA decreased sharply within the first 3 h (from ~0.0307% to ~0.0141%) and was close to 0% by ~6–12 h, indicating efficient catalytic decomposition under these conditions. In contrast, H2O2 decreased from ~0.0226% to ~0.0086% after 6 h, but then remained at ~0.006 to 0.007% from 24 to 48 h.

Figure 1.

Decomposition of PAA and H2O2 by a Fe-EDTA-mediated reaction in a HEPES-free 0.03% PAA solution without glucose (A) or with 20 g/L glucose (B). The data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s test (p < 0.05). Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among groups.

To determine whether this persistent peroxide could be eliminated, we added 20 g/L glucose into the same HEPES-free Fe-EDTA decomposition medium. Interestingly, glucose markedly accelerated peroxide removal during PAA decomposition, and both compounds decreased rapidly during the first 6 h (Figure 1B). PAA declined from ~0.0305% to ~0.0100% by 3 h and continued to decrease thereafter, reaching ~0.0049% at 6 h, ~0.0028% at 9 h, ~0.0007% at 12 h, and ~0.00009% at 24 h. In parallel, H2O2 decreased from ~0.0227% to ~0.0104% at 6 to 9 h, and then declined more slowly to the LOQ level at 48 h (Figure 1B). Thus, Fe-catalyzed decomposition of PAA in the absence of HEPES was inhibited by the delayed breakdown of H2O2, but the addition of glucose enabled more complete decomposition of H2O2.

3.2. Effect of Peptone on Glucose-Accelerated Degradation of Peroxides During Fe-EDTA-Mediated Decomposition of PAA

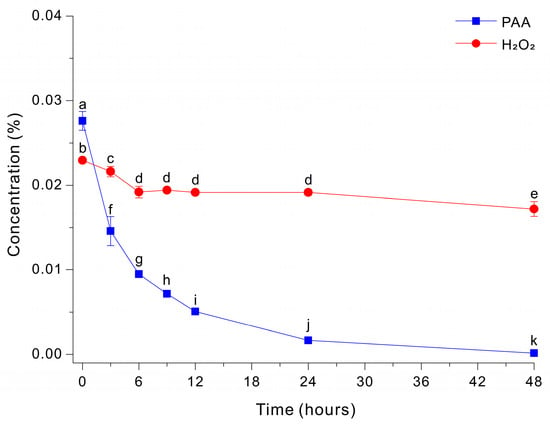

The addition of peptone (5 g/L) to the HEPES-free Fe-EDTA-mediated decomposition medium at pH 7 led to slower decomposition of PAA and incomplete removal of peroxide species (Figure 2). Specifically, PAA decreased rapidly during the initial phase, dropping from ~0.0276% to ~0.0146% by ~3 h, and this was followed by a slower decline to ~0.0016% at 48 h. In contrast, H2O2 remained essentially unchanged at ~0.0172 to 0.0229% throughout the entire monitoring period. These results indicate that peptone suppressed the decomposition of peroxide under these conditions.

Figure 2.

Decomposition of PAA and H2O2 by a Fe-EDTA-mediated reaction in a HEPES-free 0.03% PAA solution with 20 g/L glucose and 5 g/L peptone. The data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s test (p < 0.05). Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among groups.

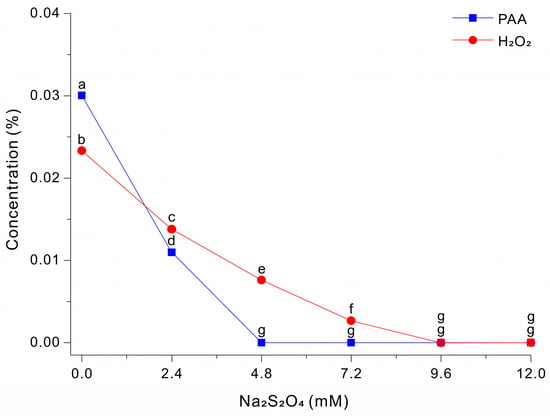

3.3. Degradation of PAA and H2O2 by Na2S2O4

We then examined the effect of Na2S2O4 on the degradation of PAA and H2O2 at pH 3. Thus, we treated a 0.03% PAA solution with different concentrations of Na2S2O4 and then measured the residual levels of PAA and H2O2 after 5 s (Figure 3). The results show that PAA decreased sharply as the Na2S2O4 concentration increased. The PAA level was ~0.0300% at 0 mM Na2S2O4, ~0.0110% at 2.4 mM Na2S2O4, and nearly 0 mM at 4.8 to 12 mM Na2S2O4. In contrast, the level of H2O2 had a more gradual decline as the level of Na2S2O4 increased and only approached 0% at 9.6 to 12.0 mM. These results indicate that Na2S2O4 reacts more readily with PAA-derived oxidants than with H2O2 under these conditions, and that the Na2S2O4 concentration can be adjusted to selectively quench PAA or to quench PAA and peroxide species.

Figure 3.

Decomposition of PAA and H2O2 after treatment with different concentrations of Na2S2O4 in a 0.03% PAA solution for 5 s. The data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s test (p < 0.05). Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among groups.

3.4. Na2S2O4-Mediated Rapid Decomposition of PAA Under Various Medium Conditions

When a solution contains peptone, Fe–EDTA-mediated decomposition of PAA is delayed, regardless of the presence of glucose and HEPES (Figure 2). Therefore, the rapid Na2S2O4-mediated quenching of PAA in the presence of peptone was examined in this study. In addition, we evaluated whether Na2S2O4 could completely quench a 0.03% PAA solution under various pH conditions (3, 5, 7, 9, and 11), as well as in the absence of HEPES buffer or EDTA. As a result, across all tested medium conditions—including the presence of organic nitrogen (peptone), a wide pH range (3–11), and conditions with or without HEPES buffer or EDTA—the peroxides in the 0.03% PAA solution were completely quenched within 5 s when Na2S2O4 was applied at a concentration of 9.6 mM (Table 1). Collectively, these findings indicate that Na2S2O4-mediated quenching of PAA is extremely rapid and largely independent of medium composition.

Table 1.

Na2S2O4-mediated quenching of a PAA solution under various medium conditions.

3.5. Growth and Paramylon Production of Cells in PAA-Treated Medium

Na2S2O4 is a highly potent reducing agent that is lethal to cells, even at very low concentrations. Our preliminary experiments with E. gracilis indicated no cell motility when the residual Na2S2O4 concentration was 0.032 mM or higher. Therefore, considering the relatively high tolerance of E. gracilis to H2O2, we adjusted the concentration of Na2S2O4 to 7.2 mM, a concentration that completely quenches PAA oxidants. Although some residual H2O2 remained in the medium, this H2O2 and the small amount of residual Na2S2O4 are unlikely to inhibit cell growth (Figure 3).

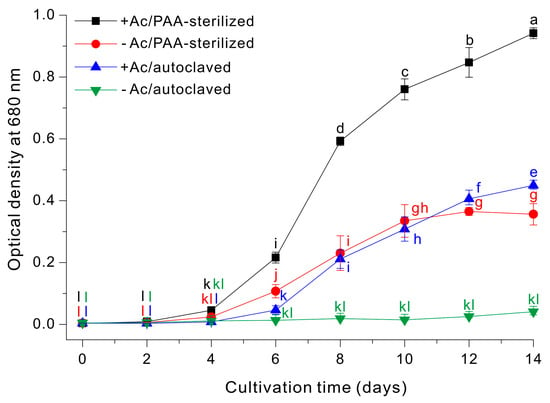

We then examined the growth profiles (OD680nm) of E. gracilis using four different growth media: (i) 10 g/L sodium acetate with autoclaving (+Ac/autoclaved); (ii) 10 g/L sodium acetate with PAA-sterilization (+Ac/PAA-sterilized); (iii) autoclaving alone (−Ac/autoclaved); and (iv) PAA-sterilization alone (−Ac/PAA-sterilized). Growth was clearly optimal in the +Ac/PAA-sterilized medium, intermediate in the –Ac/PAA-sterilized medium and the +Ac/autoclaved medium, and only negligible in the –Ac/autoclaved medium (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Growth of E. gracilis cells in a medium with or without sodium acetate that was prepared by PAA-sterilization or autoclaving. The data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s test (p < 0.05). Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among groups.

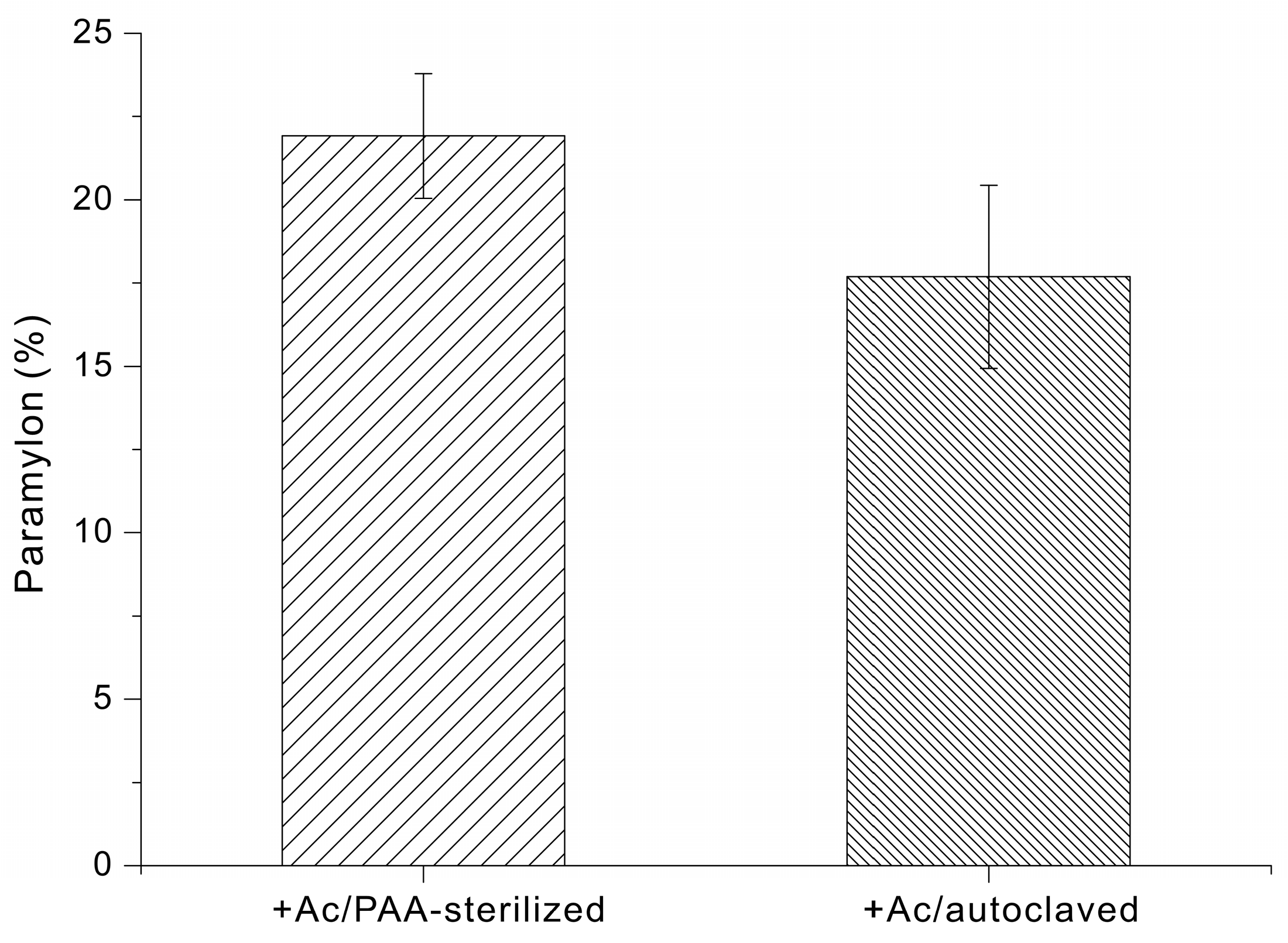

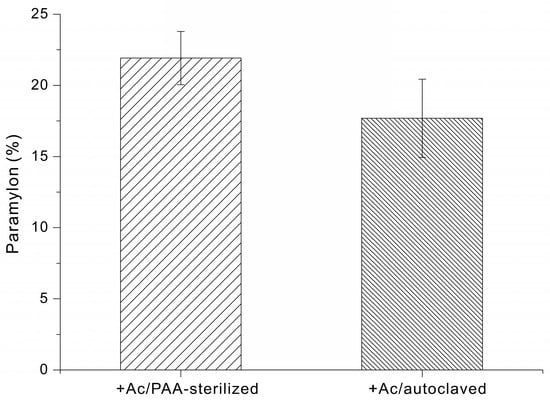

Finally, we determined the effect of different types of growth media on paramylon production by E. gracilis. When cells were grown in +Ac/PAA-sterilized medium, for 14 days the paramylon content was 22 ± 2% of dry cell weight. When cells were grown in +Ac/autoclaved medium, the paramylon content was 18 ± 3% of dry cell weight (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Paramylon content (% of dry cell weight) of E. gracilis grown in medium supplemented with sodium acetate and sterilized via PAA treatment or autoclaving.

4. Discussion

The Fe-EDTA-mediated sterilization of PAA is an attractive approach to sterilization because it uses catalytic redox cycling to decompose PAA-derived oxidants, thereby enabling sterilization of heat-labile components and polymer-based cultivation equipment. Notably, our previous study showed that a 0.03% PAA solution exhibits broad-spectrum biocidal activity, effectively inactivating most microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and spores, and that it can be completely decomposed within 12 h under optimized conditions [15,16,18,19]. However, because this approach relies on Fe-catalyzed reaction pathways, its efficacy can be decreased by medium chemistry, such as high pH, HEPES, organic nitrogen sources (peptone), and inorganic nitrogen salts (NaNO3). The HEPES-free Fe-EDTA-mediated decomposition process described herein fully decomposed PAA, but this required a reaction time of approximately 24 h. Moreover, neutralization of the co-existing H2O2 was slow, in that ~0.007% H2O2 remained after 48 h (Figure 1A). The Fe-EDTA catalyzed reaction of PAA therefore occurred in two stages: a rapid degradation of PAA and a slow and incomplete degradation of H2O2. It is possible that the absence of HEPES delayed neutralization, because HEPES is not only a pH buffer but can also maintain reaction conditions that support sustained iron redox cycling and efficient decomposition of peroxides [28]. However, without HEPES, the pH of the reaction solution will change, and even a modest change of pH could suppress the decay of peroxides, particularly H2O2. In addition, under HEPES-free conditions, the speciation and availability of catalytically active iron may be lower. Fe that is sequestered by competing ligands may undergo hydrolysis or precipitation or form less reactive complexes, thus decreasing the concentration of active catalyst.

Glucose exists partly in an open-chain form in solution and contains an aldehyde group (reducing group), allowing it to donate electrons (or hydrogen) and reduce other compounds [29,30]. Therefore, we examined the effect of glucose supplementation on Fe-catalyzed neutralization of PAA under HEPES-free conditions. During HEPES-free Fe-EDTA-mediated decomposition, the kinetics of PAA decay was similar in the absence and presence of glucose (Figure 1A,B). However, glucose supplementation substantially increased the decomposition of H2O2, and the H2O2 level was nearly 0% at 24 to 48 h (Figure 1B). This is likely because the Fe-EDTA-mediated reaction alone rapidly decomposes PAA, but complete removal of H2O2 is rate-limited by Fe redox cycling; thus, glucose apparently acts as an auxiliary electron donor that sustains the Fe(III)/Fe(II) cycle and promotes H2O2 decomposition [29,30]. Specifically, we can suggest two possible mechanisms by which glucose promotes the decomposition of residual H2O2: (i) it functions as an electron donor that sustains Fe(III)/Fe(II) redox cycling and thereby prolongs catalyst-driven peroxide turnover and/or (ii) it reacts with radicals or other oxidative intermediates to propagate chain reactions that accelerate oxidant consumption. A previous study described a sterilization–neutralization strategy in which a microalgal growth medium was sterilized with 0.02% Ca(ClO)2 and then fully neutralized with an MnCl2-Na2EDTA catalyst system within 8 h. In this previous study, glucose supplementation synergistically enhanced the MnCl2-Na2EDTA-catalyzed decay of oxidants and led to complete neutralization [17].

In the present study, we examined the effect of peptone on the Fe-catalyzed neutralization reaction. When we added peptone (5 g/L) to the glucose-supplemented Fe-EDTA solution, PAA decomposition continued gradually, but the H2O2 level remained essentially unchanged (~0.017–0.023%) for 48 h (Figure 2). In preliminary experiments in which glycine or glutamic acid was used in place of peptone, no inhibition of PAA or H2O2 decomposition was observed; rather, peroxide degradation proceeded more rapidly than in the nitrogen-free control. This behavior can be attributed to the fact that single amino acids exhibit weak and reversible coordination with iron and possess negligible radical-scavenging capacity, thereby preserving redox-active Fe2+/Fe3+ species and sustaining Fenton-type reactions that promote peroxide decomposition. The reduced decomposition of peroxides, particularly H2O2, in the presence of peptone can be explained by several mechanisms. First, peptone is a complex mixture containing peptide-bound residues as well as aromatic and sulfur-containing moieties, which can sequester iron ions, scavenge reactive radicals, and disrupt iron redox cycling [31,32]. Second, peptone may contain metal-binding ligands (e.g., histidine, cysteine, and carboxylate-bearing residues) that alter Fe speciation and/or decrease the reactivity of EDTA-bound Fe, thereby decreasing the fraction of catalytically effective and accessible Fe species [33]. Third, diverse organic constituents in peptone may scavenge radicals or other reactive intermediates, leading to decreases in chain propagation and activity of radical-mediated pathways that contribute to the decomposition of H2O2 [34]. Fourth, peptone may compete with peroxide species for oxidative reactions so that, despite the decomposition of PAA, the catalytic turnover required for sustained H2O2 decomposition—particularly the regeneration of Fe(II) from Fe(III)—cannot proceed efficiently [35]. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that complex organic nitrogen compounds can inhibit metal-catalyzed neutralization. This emphasizes that medium composition, especially supplementation by organic nitrogen and other complex organics, must be considered when designing a robust sterilization–neutralization process.

Our results indicate that Fe-EDTA-mediated decomposition rapidly consumes PAA, even in the absence of HEPES; however, a truly peroxide-free endpoint depends on elimination of the residual peroxide pool. Glucose supplementation can facilitate the complete removal of H2O2 (Figure 1A), but the presence of complex organic nitrogen sources, such as peptone, can negate this effect (Figure 2). In addition, neutralization of a PAA solution used for sterilization of microbial media via metal-catalyzed pathways, such as Fe-EDTA-mediated decomposition, requires at least 6 h under optimized conditions [15,16,18,19], making this approach unsuitable for many operating environments and media. This motivated us to develop an alternative PAA neutralization technology that does not have these limitations.

Sodium dithionite (Na2S2O4; also termed sodium hydrosulfite) is a sulfur(IV)-based inorganic salt that is widely used as a strong reducing agent in aqueous systems [25,36]. In water, dithionite functions as an efficient electron donor that is readily oxidized, and this property is responsible for its rapid reductive deoxygenation and chemical quenching of many oxidants. The results of the present study showed that Na2S2O4 provided a fundamentally different mode of neutralization than metal-catalyzed pathways. In particular, Na2S2O4 acts directly as a stoichiometric reductant that rapidly consumes oxidants present in a PAA solution, does not rely on buffers or pH, is unaffected by the presence of peptone, and does not require a prolonged reaction time. Importantly, Na2S2O4 can be used in acidic environments, and maintaining a low pH during the quenching/neutralization helps ensure robust sterilization [23]. By contrast, Fe-EDTA-mediated decomposition typically requires a pH near 7.0 to efficiently degrade peroxide species, and this can decrease the benefit of the strong biocidal activity of PAA at low pH.

Complete neutralization of the 0.03% PAA solution occurred within 5 s after the addition of 9.6 mM Na2S2O4 (Figure 3). Interestingly, Na2S2O4 also had clear reactivity against the two oxidant pools (PAA-derived oxidants and H2O2). Specifically, PAA-derived oxidants were quenched efficiently at a relatively low Na2S2O4 concentration, with near complete removal by ~4.8 mM Na2S2O4; near-complete quenching of H2O2 required a higher concentration of Na2S2O4 (~9.6–12.0 mM) (Figure 3). This difference provides a practical lever for tuning the neutralization endpoint based on Na2S2O4 concentration. From a bioprocess perspective, this selectivity is important because Na2S2O4 is a neutralizing reductant that can be cytotoxic if it remains at appreciable levels after treatment. For microorganisms that have a comparatively high tolerance to H2O2, such as E. gracilis, it may be advantageous to exploit the differential reactivity of Na2S2O4 by selecting a dose that fully quenches PAA while allowing a residual level of H2O2 to remain. If the target strain has greater tolerance to H2O2 than PAA-derived oxidants, this strategy could reduce the risk of reductant-associated toxicity by Na2S2O4 and maintain a mild residual oxidative background that may contribute to antimicrobial protection during early cultivation.

In this study, we leveraged the comparatively high H2O2 tolerance of E. gracilis to define an operational setpoint of 7.2 mM Na2S2O4 [37]. This concentration ensured complete quenching of PAA, although some H2O2 remained (Figure 3). This approach greatly decreased the amount of residual dithionite so there was no inhibition of cell growth. A growth medium prepared using this strategy outperformed conventional autoclave sterilization (Figure 4). Under acetate-supplemented conditions (+Ac, 10 g/L), PAA sterilization followed by Na2S2O4 quenching consistently led to greater cell growth than the autoclaved control. PAA sterilization likely has an additional advantage over thermal sterilization. Autoclaving can alter medium chemistry via degradation or modification of labile constituents and may generate growth-inhibitory byproducts (e.g., melanoidins and other browning-related reaction products) that decrease the quality of the growth medium [14,15,16,18,38]. In contrast, PAA-sterilization achieves decontamination without high temperature and pressure. As a result, PAA-sterilization enables greater accumulation of biomass (Figure 4). In addition, under acetate-free conditions (−Ac), the autoclaved medium had very little cell growth over 14 days, whereas the medium sterilized by PAA followed by Na2S2O4 quenching supported substantial growth (Figure 4). This outcome is plausibly attributable to the acetic acid generated during PAA decomposition/neutralization, which Euglena can use as a carbon source. In agreement, previous studies also showed that sterilization with PAA followed by neutralization led to greater growth of target organisms [15,16,18,19].

In addition to sterilization-dependent differences in biomass accumulation, the paramylon content was also greater following the PAA sterilization and Na2S2O4 quenching process (22 ± 2%) than after autoclaving (18 ± 3%) (Figure 5). The increased paramylon content observed following PAA sterilization and Na2S2O4 quenching may be attributed to improved preservation of medium integrity under non-thermal conditions. Although the underlying metabolic pathways were not directly investigated in this study, it is conceivable that avoiding heat limits glucose degradation and the formation of inhibitory byproducts, thereby maintaining more effective carbon availability for storage polysaccharide biosynthesis. In contrast, autoclaving could generate heat-derived compounds that impose metabolic stress and potentially redirect cellular resources away from paramylon accumulation.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that Na2S2O4 provided a robust, rapid, and wash-free method for quenching PAA-sterilized media and addressed the practical limitations of metal-catalyzed PAA decomposition/neutralization. Fe-EDTA-mediated decomposition often requires a near-neutral pH and a buffer and can be inhibited by complex organic constituents that lead to slow or incomplete removal of oxidants. In contrast, Na2S2O4 acted as a direct reductant that rapidly quenched PAA-derived oxidants without requiring pH adjustment or a buffer and was not sensitive to the presence of nitrogen compounds. In addition, Na2S2O4 exhibited clear differential reactivity, in that it degraded PAA at a relatively low concentration (~4.8 mM), but a higher concentration was needed to degrade H2O2 (~9.6–12.0 mM). This selectivity enabled the establishment of an operational window (~4.8–7.2 mM) in which PAA could be fully quenched while a controllable residual amount of H2O2 remained. Considering the strong cytotoxicity of residual Na2S2O4 (≥0.032 mM) and the relatively high tolerance of H2O2 by E. gracilis, we used 7.2 mM Na2S2O4 for quenching 0.03% PAA-sterilized media. Our optimized PAA-Na2S2O4 sterilization–neutralization process for preparing cultivation media for E. gracilis led to greater biomass and greater production of paramylon than conventional autoclaving.

Author Contributions

H.-J.L.: Conceptualization, Conducting experiments, Project administration, Writing–Original draft preparation; M.-S.K. (Min-Su Kang): Conducting experiments, Methodology, Investigation; M.-S.K. (Min-Sung Kim): Methodology, Investigation; J.-H.K.: Supervision, Conceptualization, acquisition of financial support for the project leading to this publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2021R1I1A3055799).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kottuparambil, S.; Thankamony, R.L.; Agusti, S. Euglena as a potential natural source of value-added metabolites. A review. Algal Res. 2019, 37, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gissibl, A.; Sun, A.; Care, A.; Nevalainen, H.; Sunna, A. Bioproducts from Euglena gracilis: Synthesis and applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, X. Euglena gracilis protein: Effects of different acidic and alkaline environments on structural characteristics and functional properties. Foods 2024, 13, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeyama, H.; Kanamaru, A.; Yoshino, Y.; Kakuta, H.; Kawamura, Y.; Matsunaga, T. Production of antioxidant vitamins, β-carotene, vitamin C, and vitamin E, by two-step culture of Euglena gracilis Z. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1997, 53, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; Toda, K.; Kitaoka, S. Enriching Euglena with unsaturated fatty acids. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1993, 57, 352–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chaudhuri, D.; Ghate, N.B.; Deb, S.; Panja, S.; Sarkar, R.; Rout, J.; Mandal, N. Assessment of the phytochemical constituents and antioxidant activity of a bloom forming microalgae Euglena tuba. Biol. Res. 2014, 47, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W.; Li, X.; Xu, H.; Chen, F.; Cheng, K.-W.; Liu, H.; Liu, B. Optimization of heterotrophic culture conditions for the microalgae Euglena gracilis to produce proteins. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, D.M.; Chanakya, H.; Ramachandra, T. Euglena sp. as a suitable source of lipids for potential use as biofuel and sustainable wastewater treatment. J. Appl. Phycol. 2013, 25, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Im, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, K.; Kim, M.; Lee, T. Biofuel production from Euglena: Current status and techno-economic perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 371, 128582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Garcia, O.; Bashan, Y.; Esther Puente, M. Organic carbon supplementation of sterilized municipal wastewater is essential for heterotrophic growth and removing ammonium by the microalga Chlorella Vulgaris 1. J. Phycol. 2011, 47, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, M.T.; Ozsahin, I.; Ozsahin, D.U. Evaluation of sterilization methods for medical devices. In Proceedings of the 2019 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 26 March–10 April 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, J.C.; Imthurn, A.C.P. Easy and efficient chemical sterilization of the culture medium for in vitro growth of gerbera using chlorine dioxide (ClO2). Ornam. Hortic. 2018, 24, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, E. Hydrolysis of sucrose by autoclaving media, a neglected aspect in the technique of culture of plant tissues. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 1953, 80, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.-J.; Kang, M.-S.; Kwon, J.-H. Sterilization of culture systems using oxidation–reduction cycles of iodine for efficient, cost-effective, and sustainable bioprocessing: Application for Euglena cultivation and production of paramylon. J. Appl. Phycol. 2025, 37, 3393–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang-Ho, C.; Do-Wook, W.; Jong-Hee, K. Development of Cultivation Process Using Decomposition of PAA for Cost-efficient Omega-3 Production by Aurantiochytrium sp. In Proceedings of the 2017 KSBB Fall Meeting and International Symposium (Abstract Book), BEXCO, Busan, Republic of Korea, 11 October 2017; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, C.-H.; Shin, W.-S.; Woo, D.-W.; Kwon, J.-H. Growth medium sterilization using decomposition of peracetic acid for more cost-efficient production of omega-3 fatty acids by Aurantiochytrium. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 41, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.-H.; Kim, W.; Kwon, J.-H. Development of a new sterilization method for microalgae media using calcium hypochlorite as the sterilant. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 47, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.-I.; Shin, W.-S.; Jung, S.M.; Kim, W.; Lee, C.; Kwon, J.-H. Effects of soybean curd wastewater on growth and DHA production in Aurantiochytrium sp. LWT 2020, 134, 110245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, M.-G.; Lee, H.; Nam, K.; Rexroth, S.; Rögner, M.; Kwon, J.-H.; Yang, J.-W. A simple method for decomposition of peracetic acid in a microalgal cultivation system. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 38, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Choi, W.-Y.; Park, A.; Lee, Y.-J.; Lee, Y.; Park, G.-H.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, W.-K.; Ryu, Y.-K.; Kang, D.-H. Marine cyanobacterium Spirulina maxima as an alternate to the animal cell culture medium supplement. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.; Dao, T.; Scott, H.; Lavy, T. Influence of Sterilization Methods on Selected Soil Microbiological, Physical, and Chemical Properties; 0047-2425; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kheirabadi, S.; Sheikhi, A. Recent advances and challenges in recycling and reusing biomedical materials. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 38, 100695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitis, M. Disinfection of wastewater with peracetic acid: A review. Environ. Int. 2004, 30, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeth, D.O.; Palmer, G. The kinetics and mechanism of reduction of electron transfer proteins and other compounds of biological interest by dithionite. J. Biol. Chem. 1973, 248, 6095–6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarov, S.V. Recent trends in the chemistry of sulfur-containing reducing agents. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2001, 70, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, M.; Pang, Z.; Dai, L.; Lu, J.; Zou, J. Simultaneous spectrophotometric determination of peracetic acid and the coexistent hydrogen peroxide using potassium iodide as the indicator. Anal. Methods 2019, 11, 1930–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kang, J.; Seo, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.Y.; Park, Y.; Yu, J.; Lee, T. A novel screening strategy utilizing aniline blue and calcofluor white to develop paramylon-rich mutants of Euglena gracilis. Algal Res. 2024, 78, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Gakh, O.; O’Neill, H.A.; Mangravita, A.; Nichol, H.; Ferreira, G.C.; Isaya, G. Yeast frataxin sequentially chaperones and stores iron by coupling protein assembly with iron oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 31340–31351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madani, M.; Hosny, S.; Alshangiti, D.M.; Nady, N.; Alkhursani, S.A.; Alkhaldi, H.; Al-Gahtany, S.A.; Ghobashy, M.M.; Gaber, G.A. Green synthesis of nanoparticles for varied applications: Green renewable resources and energy-efficient synthetic routes. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2022, 11, 731–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikhao, L.; Setthayanond, J.; Karpkird, T.; Suwanruji, P. Comparison of sodium dithionite and glucose as a reducing agent for natural indigo dyeing on cotton fabrics. In Proceedings of the MATEC Web of Conferences, Malacca, Malaysia, 25–27 February 2017; p. 03001. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasiliasi, S.; Tan, J.S.; Ibrahim, T.A.T.; Bashokouh, F.; Ramakrishnan, N.R.; Mustafa, S.; Ariff, A.B. Fermentation factors influencing the production of bacteriocins by lactic acid bacteria: A review. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 29395–29420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, S.A.; Gyawali, R.; Aljaloud, S.O.; Krastanov, A.; Ibrahim, S.A. Cultivation media for lactic acid bacteria used in dairy products. J. Dairy Res. 2019, 86, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaigher, B.; da Silva, E.d.N.; Sanches, V.L.; Milani, R.F.; Galland, F.; Cadore, S.; Grancieri, M.; Pacheco, M.T.B. Formulations with microencapsulated Fe–peptides improve in vitro bioaccessibility and bioavailability. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.-L.; Gao, M.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Li, X.-R.; Wang, P.; Wang, B. Antioxidant peptides from protein hydrolysate of marine red algae Eucheuma cottonii: Preparation, identification, and cytoprotective mechanisms on H2O2 oxidative damaged HUVECs. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 791248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.K.; Choi, J.S.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, S.Y.; Hur, S.J. Antioxidant, liver protective and angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory activities of old laying hen hydrolysate in crab meat analogue. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 29, 1774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Makarov, S.V.; Silaghi-Dumitrescu, R. Sodium dithionite and its relatives: Past and present. J. Sulfur Chem. 2013, 34, 444–449. [Google Scholar]

- Nowicka, B. Heavy metal–induced stress in eukaryotic algae—Mechanisms of heavy metal toxicity and tolerance with particular emphasis on oxidative stress in exposed cells and the role of antioxidant response. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 16860–16911. [Google Scholar]

- Leitzen, S.; Vogel, M.; Steffens, M.; Zapf, T.; Müller, C.E.; Brandl, M. Quantification of degradation products formed during heat sterilization of glucose solutions by LC-MS/MS: Impact of autoclaving temperature and duration on degradation. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1121. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.