1. The Journey to Self-Acceptance and Inspiration for Beauty With A Birthmark

“It’s ugly, and I hate it, and you know it’s ugly and should hate it, too”.

These words of my then eleven-year-old daughter, Jessica, hit my ears like an incorrect piano chord in the middle of a masterpiece. She was referring to her birthmark on the right side of her face. We later discovered that her birthmark was named Nevus of Ota. I reassured her that it was not ugly and that she was beautiful, while I hid my sadness. I will always remember that day and the moment when I realized that my beautiful Black daughter had negative thoughts about her looks because of the birthmark. That realization led to the birth of the book that we co-authored, Beauty With A Birthmark.

In my dreams of motherhood, I had hoped to have this baby girl. She was my masterpiece. Born two years after her big brother, she was a perfect fit for our family. At birth, her face was much darker on the right side. While we noticed the color variation, we assumed that it was a temporary discoloration that would fade over time. However, as Jessica grew, the birthmark remained and became a permanent part of her identity. The journey of self-discovery and self-acceptance was both hers and ours, as a family. We navigated the complexities of societal beauty standards, often finding ourselves at odds with the pervasive Eurocentric ideals that still dominate virtually every aspect of media and literature. Our experience highlights the importance of positive representation in the books that all children read, sparking the idea for a book celebrating diverse physical appearances and telling Jessica’s story as one of beauty, not of blemish.

2. Discovery of the Birthmark

“Birthmarks highlight a person’s individuality and this book shows their importance”. Toni C. Stockton, MD, FAAD, endorsement of Beauty With A Birthmark

A routine visit to the dermatologist for my son’s and Jessica’s acne turned out to be one of the most pivotal moments in our journey with Beauty With A Birthmark. We had an appointment with Dr. Toni Stockton, a renowned name in the Phoenix medical community. At one time, she was the only Black dermatologist in the entire state of Arizona and represented just three percent of board-certified dermatologists in the U.S. That kind of representation, especially in healthcare, is rare and powerful.

During the appointment, after the physician’s assistant examined Jessica, she called Dr. Stockton into the room. When I inquired about the birthmark on Jessica’s face, Dr. Stockton recognized it as Nevus of Ota. I was surprised when she explained that the two small spots in Jessica’s eyes were part of this condition. She told us it was critical that our ophthalmologist monitor any changes to ensure her vision would not be affected. Dr. Stockton’s words were reassuring and informative. Nevus of Ota, caused by the hyperpigmentation of cells, is more common in women of African and Asian descent. It can be present at birth, just as it had been with Jessica. While laser treatment is an option for those who want to address it cosmetically, the priority for us was understanding and managing any potential risks to her vision, including the possibility of glaucoma.

The fact that Dr. Stockton, a woman who looked like us, was able to identify and thoroughly explain Jessica’s condition is significant. It underscored how multicultural representation in health care matters. Studies have consistently shown that Black patients have better health outcomes when treated by practitioners who share their background and experiences. This is why Dr. Stockton’s role in Beauty With A Birthmark goes beyond a mere depiction. She is a crucial figure who educated us both in the book and real life. Her thriving practice in Phoenix, Arizona, and her endorsement of the book, with a quote on the back cover, speak volumes about the importance of having diverse voices in the medical field.

3. Challenging Traditional Beauty Standards

- Birthmarks, moles, freckles, and scars

- all unique like the sky’s stars

- These skin marks are our design—

- both mine and yours let us shine!

—Beauty With A Birthmark

Traditional standards of beauty refer to the physical characteristics and traits valued and idealized within a given society. These standards are shaped by cultural norms, media portrayals, literature, and societal expectations. They show up in every fashion and style scenario on television, internet videos, and in the movies. In many Western societies, traditional beauty centers Eurocentric ideals: light or fair skin complexions that signal and grant privilege and higher status; symmetrical facial features; blue or green eyes; long, straight, and silky hair.

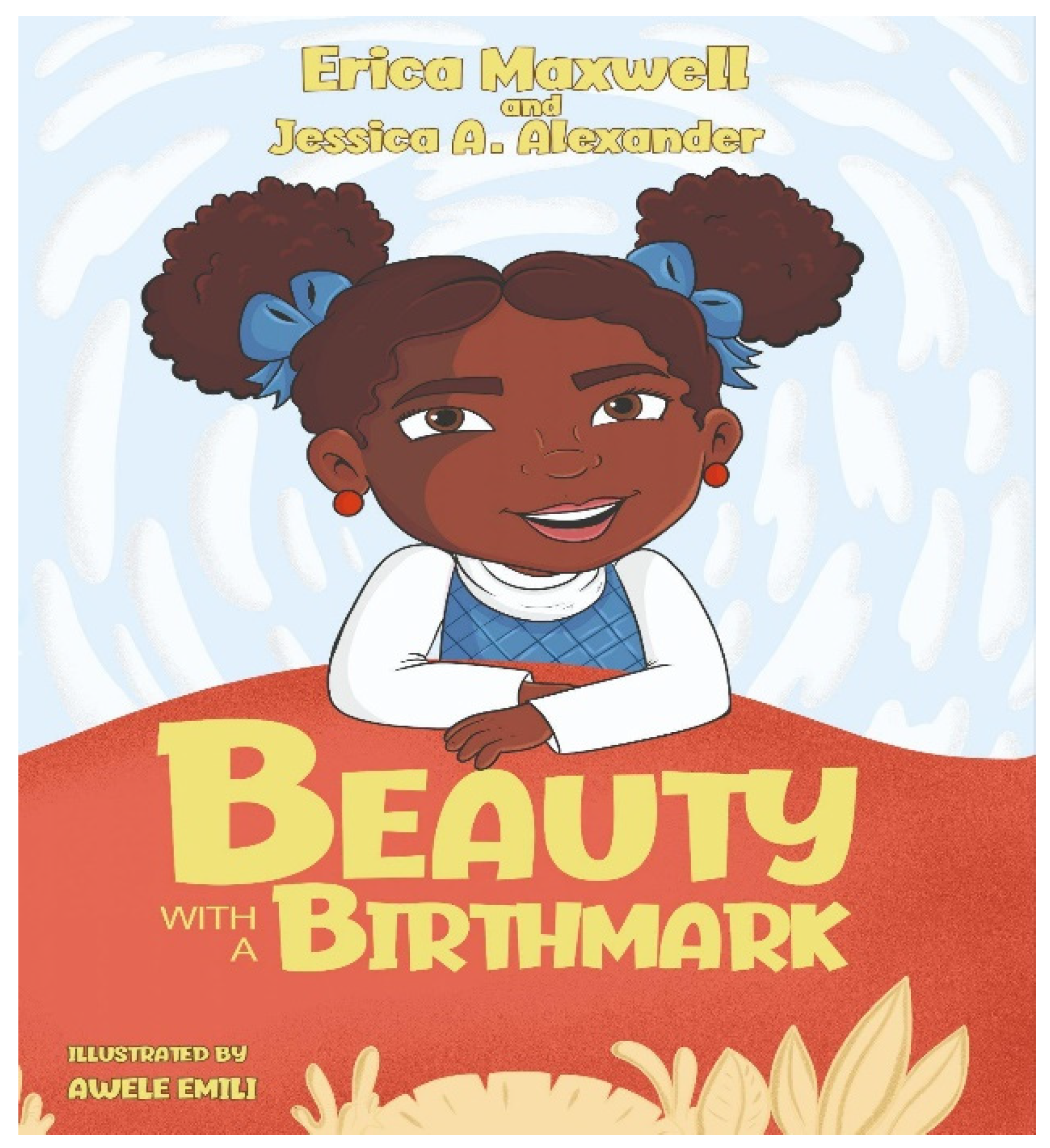

The creation of

Beauty With A Birthmark was an act of resistance against these narrow and exclusive definitions of beauty. The book’s cover was inspired by a photograph of Jessica that depicts her with the right side of her face darkened by the Nevus of Ota, kinky hair styled in cultural Afro puffs, dark brown eyes, and mocha skin. It is a way to tell Jessica and other children like her that their unique features are not seen as flaws, but as marks of beauty. The book challenges the status quo and promotes an inclusive understanding of beauty that celebrates diversity in all its physical forms and manifestations. Even the title of this book defies typical capitalization standards and expectations.

Figure 1 illustrates how the title was planned as a subversive exercise for the sake of demonstrating and valuing true diversity and acceptance outside the proverbial lines.

To illustrate this message of Black self-affirmation, the book includes characters with various skin conditions like Mongolian spots, port wine stains, moles, and freckles (see

Figure 2,

Beauty With A Birthmark). Including these diverse traits, along with an educational glossary, normalizes different physical appearances, and expands readers’ understanding and concepts of beauty.

4. Underrepresentation of Black Characters in Children’s Literature

The landscape of children’s literature has long been marked by a lack of diversity, particularly in representations of Black characters. When we began writing Beauty With A Birthmark, the underrepresentation was evident in books that sought to address birthmarks. Two prominent books were Buddy Booby’s Birthmark (2007) and Sam’s Birthmark (2013). While both books address birthmarks, they leave a pronounced void in representation. Buddy Booby’s Birthmark, for example, features a stork as a presumably male protagonist, a well-meaning but distant choice for children yearning for human characters they can see themselves in. Similarly, Sam’s Birthmark places a white male at the center of its narrative, which again reflects the dominant trend in children’s literature: white male characters as main characters. Both stories, while valuable in their lessons about acceptance and physical difference, fail to provide children of color, particularly Black children, with protagonists who resemble them and affirm their experiences. Such omissions reinforce the notion that Black children are either invisible or not deemed worthy of being central figures in stories about self-acceptance and beauty. This realization was a catalyst for Beauty With A Birthmark, a story where a Black child with her unique birthmark can stand proudly at the center. Through this work, we challenge the homogeneity of children’s literature and offer a narrative that celebrates Black beauty, inclusivity, and the individuality of all children.

Nancy Larrick (

1965) brought the lack of representation in non-white children’s literature to national attention in her seminal 1965 article, “The All-White World of Children’s Books”, published in

The Saturday Review. In her article, Larrick exposed the pervasive racial exclusion in children’s books, revealing that a mere 7 percent of the 5206 children’s books published between 1962 and 1964 include one or more Black characters. Even more troubling is the fact that when Black characters were present, they were often relegated to secondary roles or depicted through stereotypes: “Many children’s books which include a Negro show him as a servant or slave, a sharecropper, a migrant worker, or a menial”, reinforcing a social and racial inferiority rather than empowerment.

Despite the growing diversity in society, children’s books featuring Black main characters remain woefully underrepresented. According to a study by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, only 11.9 percent of children’s books published in 2018 featured Black characters. This lack of representation has profound effects on young Black readers, particularly in terms of self-esteem and identity formation. Within the space of Black protagonists, the gap remains for celebrated Black female protagonists. According to studies on diversity in children’s literature, between one and two percent of children’s books feature a Black female main character. A 2022 report by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) found that while there has been improvements in the representation of characters of color, the number remains disproportionately low, especially for Black female protagonists. Efforts to increase diversity are ongoing, but the underrepresentation of Black girls in children’s books continues.

Historically, the opportunity for Black children to see themselves in literature was nearly nonexistent. W.E.B Du Bois, with

The Brownies’ Book (1920), sought to change this reality by showing Black children that being “colored” is a beautiful thing (

McGee 2023). However, it was not until Ezra Jack Keats’s

The Snowy Day (1962) that a mainstream picture book featured a Black protagonist. And Keats’ book was not without some stereotypical representations of a Mammy-like mother image and a Black father absent from the family unit. Walter Dean Myers echoed this ongoing issue of underrepresentation in his 2014

New York Times op-ed, asking “Where are the People of Color in Children’s Books?” Myers argued that the absence of Black characters sends a message of exclusion and limits the opportunities for both Black and white children to understand the full spectrum of humanity, theirs and others’ (

Myers 2014).

5. The Importance of Inclusive Literature

Inclusive literature plays a crucial role in shaping children’s perceptions of themselves and others. For all children, seeing characters that look like them in the books they read validates their experiences, raises their self-esteem, and fosters belonging. This reality is especially important for Black children who often face societal messages that devalue or erase their appearance and culture altogether. Books like

Beauty With A Birthmark affirm Black self-worth and beauty, countering the negative stereotypes they encounter. Our repetitive phrase, “I am a beauty with a birthmark”, throughout our book is an affirmation, encouraging readers to celebrate their unique traits. Affirmations in educational settings can have far-reaching effects, helping to reduce academic stress and improve overall student well-being (

Yeager and Walton 2011). For instance, in the (

Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) 2019), a young student of color shared: “When I see people that look like me in books, it makes me feel like I belong in the world and can do things like the characters do”. Still, within this diversity of representation, data shows that lighter-skinned Black and Brown children see themselves represented more often in these books than darker skinned children (

Adukia et al. 2023), highlighting a persistent imbalance in whose experiences and identities are worthy of storytelling.

Research further shows that when students see themselves reflected in school curricula, they are more engaged and more motivated to learn. Incorporating diverse books into classrooms and school libraries validates students’ experiences and enhances their academic performance. When children do or do not see others represented, their conscious or unconscious perceptions of their own potential and that of groups with identities different than theirs can be molded in detrimental ways and can erroneously shape subconscious defaults (

Adukia et al. 2023). For marginalized students of any group, being able to read literature that reflects their identities assists educators in creating inclusive learning environments that support the success of all students.

6. Appreciation of Diversity in Inclusive Literature

About our book, Beauty With A Birthmark, Judith Outten, M.D., Licensed and Board-Certified Adult/Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist, observed: “This delightful book is vital for building children’s self-esteem as they learn to fully embrace themselves and what makes them unique. It’s an integral part of any home library as an important child development tool that teaches empathy, understanding and acceptance—key character traits that can greatly reduce the likelihood of bullying”. The impact of inclusive literature extends beyond individual self-esteem. It also promotes empathy and an appreciation of diversity among all readers. Jessica’s story emphasizes the strength, resilience, and joy of a Black girl protagonist who engages in activities that any child might participate in: swimming, playing the piano, celebrating her birthday, cheerleading, traveling across the United States, and spending time with friends and family who fully embrace her in all of her beauty. Despite differences with the identity of the main character, who is a Black female with a birthmark, the reader can form a human connection through seeing these experiences, thereby potentially developing a more compassionate view when they interact with those who have birthmarks or other visible and invisible differences.

Inclusive literature celebrates the richness of human diversity by weaving together narratives that reflect the interconnectedness of various aspects of identity. As noted by

Adukia et al. (

2023), “we also draw on a central insight from the study of intersectionality. Different aspects of identity—such as race, gender identity, class, sexual orientation, and disability—do not exist separately from each other but are inextricably linked”. This understanding emphasizes the importance of moving beyond single-dimension portrayals in literature to acknowledge the complexity of individual and collective experiences. When children’s books embrace intersectionality, they provide authentic representations that resonate with readers from all walks of life.

Hopefully, Black children in our audiences and those who read our book will recognize a shared experience and connect with the main character in a way that transcends cultural, social, and personal barriers. By layering identities and portraying everyday experiences alongside Jessica’s uniqueness, our book offers readers a broader understanding of beauty and acceptance, challenging the conventional notions about normality and difference. When children are exposed to stories featuring diverse characters, they learn to see the world from different perspectives. This can lead to greater understanding and acceptance of people from different backgrounds, fostering a more inclusive society.

7. The Role of Gatekeepers

The process of writing and publishing this book was deeply personal and political. When cultural gatekeepers come from homogenous backgrounds, they unintentionally miss the richness and nuance of stories that speak to underrepresented communities. Our experience with self-publishing Beauty With A Birthmark was both empowering and eye-opening.

To begin our publishing journey, I consulted with several of my colleagues in the community colleges who referred me to a local author who was also a former student of theirs. This person had recently published a children’s book with an animal as a main character. After meeting with this author who recommended a local company, Five Star Publications, and after spending USD 400 on an initial review of our manuscript in 2015, I was excited to receive feedback, hoping it would help bring our vision to life. However, the review came from a white male whose expertise centered on books with animals as main characters. His review marked our story as being without interest. The unique story that we wanted to tell—one that celebrates diversity, individuality, and self-acceptance—seemed to be overlooked in favor of animals as main characters and more generic subjects that might appeal to mainstream white readers—children, parents, librarians, and educators who still make up 80 percent of public-school K-12 classroom teachers. It was clear that the narrative shaped by Jessica’s and my lived experiences did not resonate with this non-Black male reviewer’s perspective. For more than 25 years, the landscape of major book publishers in the U.S. has remained the same. Today, the “Big Five” publishing houses are Penguin/Random House; Hachette Book Group; Harper Collins; Simon and Schuster; and Macmillan (

Horne 2023). These giants dominate the industry, yet only five percent of the smaller publishing houses are Black-owned, according to Statista.com. Additionally, buyers play a crucial role as decision-makers in determining which books are on the shelves. As Horning notes, “more than one publisher has told me that they’ve heard Barnes & Noble buyers say that Black books don’t sell” (

Horning 2014). Still, we have experienced support from our local Barnes & Noble at Chandler Mall (Chandler, AZ), through participation in storytime and local author events where we have been invited and featured. While these local engagements have had a positive impact, we aim to expand our reach nationally, which will require buyers to purchase our books in bulk and stock them in stores across the country.

In my journey as a children’s book author, I knew that we wanted something different—a publisher that reflected us and our culturally-specific perspectives. With intention, I sought out and found Amber Books, a reputable press right here in Phoenix, Arizona. Amber Books, owned by Tony Rose and his spouse Yvonne, stands as the largest African American publisher in the U.S. It was a privilege to partner with Yvonne, the director of Quality Press, a company that supports authors who self-publish. When we realized that the chances of Beauty With A Birthmark being selected by one of the major publishing houses were slim and that the costs associated with traditional publishing were daunting, we chose the path of self-publishing. We purchased a package from Bowker Publishing Services, which included essential tools like ISBN numbers, eBook creation, copyright registration, and barcodes.

Throughout the process, I leaned on Yvonne for her invaluable guidance. When my illustrations and text were finalized, she helped me cross the finish line, ensuring that my book was properly formatted and ready for distribution through Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Her expertise was a crucial part of our success, and I continue to recommend her to other aspiring authors.

The publishing industry’s gatekeepers—publishers, editors, and agents—play a critical role in determining which stories reach young readers. Historically, the industry has been dominated by white decision-makers, resulting in limited opportunities for authors of color telling stories of people of color. While there is a growing movement to diversify the publishing industry through organizations such as We Need Diverse Books, significant barriers remain. To ensure that more stories like Beauty With A Birthmark reach children and communities across the globe, publishers must actively seek and support diverse voices, recognizing the value of stories that reflect the experiences of all children.

According to the Lee and Low Books 2023 Diversity Baseline Survey Publishing Industry Demographics, 72.5 percent of workers in the book publishing industry identified as white, a decrease since their last study, published in 2019 (

Anderson 2024). This percentage includes U.S. publishing, review journals, and literary agent staffers. In a New York Times article, publisher Linda Duggins stated “Publishing houses and institutions within this industry are not set up for people of color. … You’re bucking up against really entrenched cultures” (

Alter and Harris 2024). This lack of diversity adversely impacts Black children’s literature in a variety of ways: limited representation; narrow narratives; cultural misrepresentations; fewer opportunities for Black authors; and impact on readers of all backgrounds. Overall, the publishing industry’s lack of diversity creates an ecosystem where Black children’s literature is underrepresented, limiting the range of stories available to all children and perpetuating systemic inequities in education and cultural understanding.

8. Inside Beauty with A Birthmark

Beauty With A Birthmark is written in rhyme and captures beauty beyond conventional standards as the main character born with a prominent birthmark comes to embrace her uniqueness. The vibrant illustrations were designed by Nigerian illustrator Awele Emili, a freelance artist whom I contracted with through Upwork. We provided Awele with several of Jessica’s photographs, and we were pleased with the way Awele accurately rendered Jessica as she joyfully participates in everyday activities like playing the piano, cheerleading, and running track, highlighting her confidence and talent. Jessica’s travels across the United States and her celebrations with friends and families who love and accept her for who she is further underscore our message of self-acceptance and inner and outer beauty. We were intentional about emphasizing Jessica’s rich experiences, her supportive friendships, and embracing her individuality.

Beauty With A Birthmark is more than a book; it is a statement. It is a declaration that all children, regardless of their physical appearance, deserve to see themselves represented in the stories they read. It is a call to action for the publishing industry to prioritize diversity and to create space for voices that have been historically marginalized. Through our book, we know that we will validate and inspire other authors and illustrators to tell stories that reflect the rich diversity of our world.

9. The Personal and Local as Global

Our journey of writing and publishing

Beauty With A Birthmark has been deeply intertwined with our desire to share the message of self-acceptance and beauty with children across the world. This mission came full circle during our literacy mission trip to Johannesburg, South Africa in October 2023. We shared our book at an elementary school where Jessica, the heart of the story and real-life inspiration behind the character, read the book aloud (see

Figure 3,

Beauty With A Birthmark). What unfolded was magical. Without being prompted, the students rushed to share their own books with Jessica. They were astonished to discover that she was the main character in the book; their excitement was palpable. The principal engaged in a meaningful conversation with Jessica about her life as a child and young adult with a birthmark in the United States, further deepening the connection between her story and these young African students.

This experience on the mission trip echoed the broader themes of Beauty With A Birthmark, particularly in the context of Africa where views of beauty, including birthmarks, vary across cultures. In some African cultures, birthmarks are symbols of uniqueness, beauty, or even good fortune, while in others, they may be misunderstood. Our book, because it is rooted in the idea that beauty comes from embracing one’s uniqueness, aligns with these diverse perspectives, and opens into conversations about how different cultures view and celebrate beauty. Meeting the African students and seeing their reactions affirmed the power of storytelling to bridge gaps and to inspire self-love. It was a moment where our written words and real-life experiences merged to reinforce the fact that beauty transcends appearances and cultural boundaries.

Writing Beauty With A Birthmark has been a journey of discovery, resistance, and hope. It is a testament to the power of representation and the importance of inclusive literature. By challenging traditional beauty standards and promoting diversity in children’s books, we can create a more inclusive and affirming world for all children. Jessica’s story is just one of many, but it is a reminder that every child deserves to feel beautiful and valued.

10. From the Margins to the Center: In Jessica’s Own Words

I would never have thought I would ever be the main character of a book! Beauty With A Birthmark highlights one of my biggest insecurities. What does it mean to me to have this opportunity to share my story of pain, vulnerability, and triumph? Empowering is the best way to describe this feeling now as I read my story to and share with others. I feel empowered through my loving mother whose care, concern, and consideration of me was enough to express my beauty through this children’s book. I am empowered through being the main character, and a source of inspiration and empowerment to those around the world who have similar birth and skin marks, or none at all but are open minded to learn about them. I feel loved and seen through not just my loving and talented mother, but also through the world/community. Our book has brought out love and support through my interactions and sharing my story with so many people with whom I would never have interacted otherwise. Awareness is another word that describes what this book has brought to me and to this new sense of being in community locally and globally.

My birthmark has damaged me. One of my first heartbreaks was self-inflicted through insecurity. My birthmark made me feel different—not stand out and stand tall “different”; more of a “different” where I didn’t fit with others. I didn’t belong. Was I ugly? Little old Jess didn’t know why her face was two-toned until I was 11 years old, when a dermatologist showed interest, too. I was never ugly, but I always thought so. I recalled cruel, unthinking classmates calling me a “cow” and describing me as “the dark-skinned girl with that stuff on her face”. My confidence waned as I attempted to connect with others and build relationships when I wasn’t loving or embracing myself fully. It absolutely hurt me to my core. So, I wore my birthmark as a mask. Two-toned in the face, my birthmark had me masked up. I became those who made fun of me. I spat hate right back out my mouth because that’s what was surrounding me as a form of protection I owed to myself. As I matured in age and grew in self-acceptance, it got easier because the crowd grew and people stopped caring about the way I looked. I gained confidence and found people who aided and reassured me that I was well-deserving of love and care. But that mask never left my side. I like to think it was the start of my attitude that I carry with me. The mask is a part of me and will never leave. I protect myself before opening up to anyone new. If I see anyone like me, I’m eager to converse because maybe they’ll understand, and I’ll be able to be seen and heard beyond my birthmark.

Books and readings are amazing, not just for the kids. I thank the adults who allow their kids to tune in because that’s where education and empathy start! There are many pictures of me where it seems as though I’m more tuned in with the crowd than anything else, as if they’re telling me the story. But that’s how I view it. Others are now part of my story. Beauty With A Birthmark is me, I am a Beauty!

Kids engaging in the book will mention anything from “I like swimming, too” to trying to pronounce the word “dermatologist” for the first time. These genuine moments in response to our book and my story will always intrigue me. Sharing this book and story about me with others brings me joy. I will be forever grateful for the experience to educate those willing to listen, as well as entertain. Public readings of our book have also brought me close to many people. Some stop by just out of curiosity about the book. Some walk away 30 min later with a signed copy made out to someone specific because in some way, they connected them to our book. Our book speaks to people with and without birthmarks, of all ages, genders, ethnicities, and religious beliefs. Our mother-daughter book welcomes all, redefining beauty and amplifying awareness, love, and education. All kids need books that hug them in the way that Natasha Tarpley beautifully states when referring to books she writes, “I wanted the book to feel like a warm hug for Black kids—one that would encourage them to connect with their inner beauty and inspire a more holistic love of self” (

Tarpley 2023).

11. Ripples of Impact

Beauty With A Birthmark has garnered significant attention and support since its release. The book has resonated with readers for its message of self-acceptance and the importance of embracing uniqueness. It has been especially meaningful to connect with families and educators who value diversity and representation in children’s literature.

One of our most memorable engagements was an author’s visit to an elementary school in South Phoenix. Jessica read the book to students and our visit sparked meaningful conversations about self-love, uniqueness, and inclusion. Many students eagerly shared their own stories and affirmations.

Our journey also took us to Kent State University (Erica’s alma mater), where we shared the book with children at the Child Development Center on campus. Connecting with young readers there was a special experience, bringing the book’s message full circle to a place that shaped a meaningful educational journey.

In addition to schools and universities, we have had the pleasure of participating in Storytime and Local Authors Events at Barnes & Noble in Chandler Mall, where we connected with families and fellow authors to celebrate the importance of diverse children’s literature.

The Phoenix Children’s Hospital Dermatology Department also purchased copies to provide for their patients, furthering our mission to empower children with visible differences. Jessica had an incredible opportunity to be a special guest for the Wild ’N Out Tour in Phoenix, where she was recognized as an Ncredible Changemaker. She shared her book with celebrities, spreading the message of self-acceptance to an even broader audience.

Our media engagements on Good Morning Arizona (3TV) and Arizona Horizon (PBS) helped amplify the book’s message across Arizona. Additionally, Beauty With A Birthmark is listed on the Vascular Birthmarks Association’s Children’s Book List, making it a valuable resource for families affected by vascular birthmarks.

Through these experiences, Beauty With A Birthmark has continued to inspire children and adults to embrace individuality. These engagements spark meaningful conversations about beauty, identity, and self-acceptance, and we look forward to expanding our reach to empower even more communities.