Accepting the notion that “childhood” and “adulthood” are social constructs and not biological facts affords an opportunity to see and understand how the lived experiences of children and adults, past and present, intersect in complicated and multitextured ways. Literature created for and about children, then, is always filtered through the lens of adult experiences since children are not writing, publishing, or buying their own texts. Adults are the gatekeepers defining and documenting the good and the bad of children’s lives and placing value and legitimacy on the creative and literary expressions for and about children.

To read the history of a society, a nation, a country, a community, and of a people is to attend to the children’s texts—songs, ditties, toys, stories, folktales, folklore, jokes, games, and play rituals—that serve to indoctrinate and to teach lessons and values about good and evil, about right and wrong, about Black and white. Even as adult politics are framed allegedly around “protecting the children,” children have participated directly in social movements and been directly affected by social injustices.

This Special Issue of Humanities focuses on African American children’s literature and looks at the many ways in which reading and studying children’s texts teach as much about the adult world as about the world of children. This collection is not a history of African American children’s literature though histories certainly inform the texts written, published, lauded, celebrated, banned, taught, or ignored. Those who study and teach African American children’s literature know that stories and narratives about Black children were not always available in ways and forms that celebrated Black children when they were not altogether erased or absent. From stereotypes to violence, literary and creative expressions about Black children by non-Black authors—when available—engaged problematic tropes of white saviorism, exceptionalism, animalization, primitivism, violence, and tokenism—too often in efforts to “educate” and entertain white children often through humor and dehumanization. When Black authors endeavored to rescue Black children from the damaging tropes that denied humanity, they too often subscribed to respectability politics, “toxic positivity,” colorism, and classism. From representations to illustrations to narratives, this Special Issue offers a more critically nuanced treatment of Black children’s lives and experiences.

A 2018 “Diversity in Children’s Books” Infographic created by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, Department of Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, offers this representation breakdown in children’s books: “American Indians/First Nations (1%), Latinx (5%), Asian Pacific Islander/Asian Pacific American (7%), African/African American (10%), Animals/Other (27%) and White (50%)” (). So, while there are far more books about Black children, there is plenty of work to be done to move Black children’s literature to the same studied value both inside and beyond the academy to reflect the value and meaning of Black children’s complex lives and experiences. This Special Issue moves that critical conversation along more deliberately and intentionally, moving African American children’s literature from the sidelines and margins to the center of literary and cultural studies. This collection imbues African American children’s literature with the same complexity, nuance, and relevance as African American adult literature, essentially breaking down the artificial barriers around relevance, value, and importance.

In Toni Morrison’s novel The Bluest Eye (1970), Claudia MacTeer narrates a childhood memory of meeting her Black family’s new rental tenant. This perspective mirrors the ways in which adults have not always centered children or children’s experiences in the world: “Freida and I were not introduced to [Mr. Henry]—merely pointed out. Like, here is the bathroom; the clothes closet is here; and these are my kids, Frieda and Claudia; watch out for this window; it doesn’t open all the way” (). Ideally, this Special Issue contributes to the growing body of scholarship and discourse that covers a range of identity and representation issues that center rather than marginalize African American children. This collection further underscores the reality that critical conversations about children and what they are exposed to are as much about the adults who create and present these texts and ideologies to children. This Special Issue will be of interest to and a valuable resource for students, parents, teachers, and community members invested in representation, narrative, social justice, critical race theory, identity politics, and publishing industry bias. It also makes the invisible visible and relevant, and acknowledges children and children’s lives beyond just being extensions and human possessions of adults and parents.

As for putting this Special Issue together, contributors responding to the 2021 Call for Papers were offered these possible prompts to show the volume’s open range of perspectives for consideration:

- Black children and mental health;

- Black children and sexuality;

- Black children and transgender identity;

- Black children and violence;

- Black children and US history;

- Black children and the Diaspora;

- Black children and toys and games;

- Black children and sports;

- Black children and death and dying;

- Black children and education;

- Black children and dance;

- Black children and theater;

- Black children and creativity;

- Black children and disability;

- Black children and racial justice;

- Black children and white supremacy;

- Black children and social movements;

- Black children and Black Lives Matter;

- Black children and “critical race theory”;

- Black children and language;

- Black children and music;

- Black children and the arts;

- Black children and folklore;

- Black children and science;

- Black children and class;

- Black children and social organizations;

- Black children and homelessness;

- Black children and other racial/ethnic groups;

- Parenting Black children;

- Black children and “curriculum violence”;

- Black children and trauma;

- Black children and intergenerational trauma;

- Black children and play.

Such a list of possible topics underscores the complexity of perspectives and the myriad angles from which this specific literature could and can be examined. This list is also a reminder that this volume is not meant to be comprehensive in that everything about this literature is included. While the various essays that constitute this volume involve historical and social contexts, the goal of the collection and these essays is to remind readers across disciplines and professions that Black children are and have always been at the nexus of adult US racial politics.

- Special Issue Trials and Tribulations

Relatively speaking, having this volume of essays on African American children’s literature come together has been no small feat. While I enthusiastically accepted the invitation to edit this Special Issue as an exciting opportunity four years ago, I also encountered a number of challenges. Some of these challenges had to do first with getting enough Contributors. Other challenges involved the very nature of this journal’s review process to include different kinds of essays solicited and received. This process has taught me quite a bit about professional and editorial gatekeeping and about the ways in which efforts to open up and even expand critical conversations about African American children’s literature from multiple and diverse perspectives continually bump up against “tradition,” against scholarly and editorial skepticism. My frustration in this regard was shared among those who do not come at this and their work in African American children’s literature as “traditional scholars.” What constitutes this final volume makes me happy and satisfied that I and some of the authors persisted to the bitter end.

One of the first lessons I have learned in this Special Issue Guest Editorship is that African American children’s literature is still a relatively small area of academic inquiry, exploration, and expertise within the academy. I already knew based on my engagement with mostly faculty colleagues at other institutions of higher education that I can readily identify folks who do African American “adult” literature. I can easily find folks who do children’s literature more broadly. Those who do African American literature do not necessarily do children’s or young adult literature, and those who do children’s literature do not always hold space for and expertise in African American children’s literature. Arguably, those of us who do African American children’s literature are a rather rare cast of academics. That was potentially part of the challenge of receiving contributions but also in identifying reviewers who could speak critically and knowledgeably about this particular genre.

This reality is also what led to other bigger challenges that I faced as the Guest Editor. Attending in March 2024 the inaugural African American Children’s Literature Symposium1 in Washington, DC, opened my eyes to the reality of multiple aspects of African American children’s literature that go beyond the authored books and the “traditional scholars” who analyze and write about children’s books. The symposium, focusing on the “Role of DC Writers in Building Canon and Community—1970s through the Present.” had a very specific regional focus, but the attention to others associated with publishing, distributing, illustrating, and marketing African American children’s books was on full display. Attending this conference allowed me to make connections with others who are not affiliated with institutions of higher education, and that in itself proved challenging for the journal’s review team. At the conference, I also met authors writing these books that constitute the African American children’s literature canon as we know it, and their contributions offer an insider’s perspective on this subject, particularly regarding publisher biases, marketing, and distributions. I was also reminded of the blatant gatekeeping that still exists within the publishing industry that keeps certain kinds of stories from seeing the light of day. That means, I have learned, that so many stories, experiences, perspectives go unheard and unrealized. Hence, this volume intentionally engages these sobering conversations that in many ways led to the initial historical need for Black stories that intentionally center Black children’s lives and perspectives. While I invited many more individuals to consider submitting pieces than appear in this volume—an illustrator, a satirist, a filmmaker, a doll collector, a bookstore owner, a bookstore distributor, and a social justice organization, for instance—many of those approached declined my invitation or gave up after we reviewed first drafts and abstracts because they felt unprepared to write what I and this journal were asking of them critically. What I was asking of them was what was being asked and expected of me as the journal issue’s Guest Editor. For those who accepted my invitation, I am most grateful. I, too, felt the air sucked from beneath their and my wings each time another level of edits and revisions was requested before an essay was finalized and then moved forward to completion and final acceptance. Importantly and disappointingly, these editorial revisions often had nothing to do with the overall quality of the submissions but all to do with a checklist of what essays in this journal “traditionally” look like and entail.

At last, this volume has come together in a way that showcases and amplifies multiple aspects of African American children’s literature. I am also adding two journal-identified “editorial pieces” as insider perspectives to complement these “scholarly articles” that do have their professionally obligatory footnotes and referencesIn one of the final essays submitted, reviewed, and accepted for this volume, the author contextualizes her teaching of a Jacqueline Woodson young adult novel within the current US political climate that is legislatively and aggressively whitewashing, erasing, or rewriting US history. This current moment disturbingly reflects the publication reality that initially led to the need for Black authors to tell their Black human stories as they both lived and imagined their experiences.

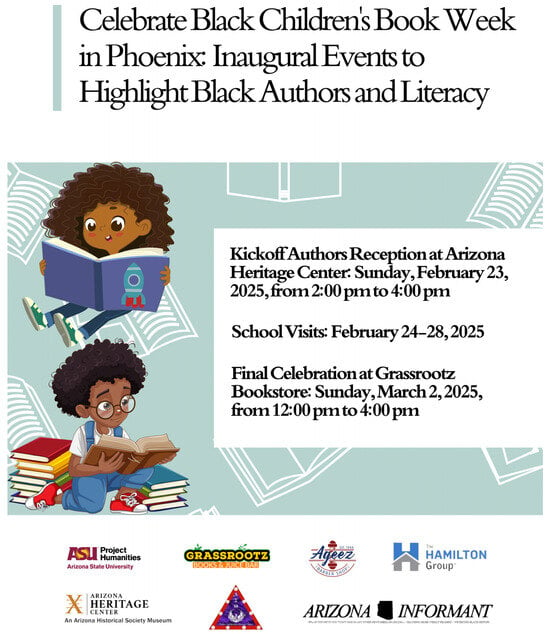

On a related note, as I was putting this volume together, I was invited to be part of a community grassroots advisory team facilitating the inaugural Black Children’s Book Week2 in Phoenix, AZ, from 23 February through 2 March 2025. As the five of us identified several local Black Arizona authors with books, enthusiasm, and readiness to participate in what was a very successful inaugural event, one of our marketing pieces went out thusly: “Celebrate Black Children’s Book Week in Phoenix: Inaugural Events to Highlight Black Authors and Literacy.” As we were promoting the culminating event where multiple authors would be reading to children from their books, I received a communication from my university dean and the university’s General Counsel asking—or rather telling me—to remove the word “Black” from our reference to “Black Authors” (Figure 1). While, technically, non-Black authors can and did write Black children’s literature that was not laden with racist tropes, caricatures, and stereotypes, the very reason that Black authors emerged was to counter the all-too-prevalent racial and cultural misrepresentations by non-Black authors. As instructed, we removed the word and recognized in so doing that the socially and politically aggressive anti-CRT (Critical Race Theory), anti-WOKE, and anti-DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) movements are once again trying desperately to silence, erase, or whitewash Black stories, Black experiences, and Black lives altogether, both inside and beyond classrooms, libraries, and publications. The very existence of this volume will not allow that to happen.

Figure 1.

Marketing flier for inaugural Black Children’s Book Week in Phoenix, AZ (23 February–2 March 2025), sent out electronically on 27 February 2025 from the Arizona State University Project Humanities marketing team since Project Humanities was a leading event sponsor.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are not conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Presented by (), with this complete title: “African Americans and Children’s Literature: An Examination of the Role of DC Writers in Building Canon and Community—1970s through the Present.” See day’s event video recording of all panels here: https://tinyurl.com/5fb74pc2. (available online 27 September 2025) |

| 2 | See (). Founded by Veronica N. Chapman in January 2022, this national event was created as “an invitation for everyone to be intentional about making sure Black children feel our love.” This sweeping anti-Blackness is both literal and figurative, part of a broader political movement to paint diversity generally and Blackness specifically as “divisive” and un-American. See this story by Daniel Johnson about removing the word “Black” from a named Goldman Sachs marginalized group initiative: “().” About this change, Ashai Pompey, an African American woman and Goldman Sachs’ Global Head of Corporate Engagement, admits being aware of the current political scrutiny of all public and private alleged DEI programs: “Goldman Sachs was ‘aware of what’s out there,’ a reference to the political climate around diversity, equity, and inclusion, but said that despite this, ‘we are very focused on achieving the objectives of our program. Of course, we do that in operation and in compliance with laws, but our commitment to One Million Black Women is strong.’” |

References

- Chambers, Veronica N. 2022. Black Children’s Book Week. Available online: https://blackbabybooks.com/bcbw/ (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Dahlen, Sarah Park. 2019. Picture This: Diversity in Children’s Books. Available online: https://readingspark.wordpress.com/2019/06/19/picture-this-diversity-in-childrens-books-2018-infographic/ (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Esther Productions, Incorporated, The Black Student Fund, and The Institute for African American Writing. 2024. African Americans and Children’s Literature: An Examination of the Role of DC Writers in Building Canon and Community—1970s Through the Present. Washington, DC: Trinity Washington University. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Daniel. 2025. Goldman Sachs Drops ‘Black’ from Diversity Pledge, Rebrands ‘Black in Business’ as Profit Initiative. Black Enterprise. Available online: https://share.newsbreak.com/cxd7kwbk (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Morrison, Toni. 1970. The Bluest Eye. New York: Washington Square Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).