Abstract

Literature suggests that culturally promotive curricula can counter the effect of anti-Blackness in United States (U.S.) schools by cultivating Black students’ cultural, social, and academic development and fostering learning environments in which they feel respected, connected, and invested in their school communities. However, Black students, especially young Black men, who return to school following a period of incarceration, face discrimination and numerous barriers to school reentry and engagement. While some enroll in alternative schools as a last option to earn a diploma, little is known about how curricula in these educational settings can facilitate positive school reentry experiences and outcomes among this population. As such, this intrinsic qualitative case study explored how one alternative school’s culturally promotive curriculum fosters and cultivates educational resilience among formerly incarcerated young Black men. Data collection included observations, interviews, and document reviews, and utilized a thematic analytic approach that included grounded theory techniques. Results indicate that teaching content that formerly incarcerated young Black men perceived as truthful and relevant to their lived experiences augmented their school engagement. The young men reported feeling empowered by the school’s curriculum structure and culture that allowed them to self-direct learning goals and course content toward themes that affirmed their cultural and social identities. The curriculum also appeared to facilitate positive relationships with the instructors, leading to the development of a positive school climate where the young men felt safe, appreciated, and supported. These findings highlight the important role space, place, and relationships can play in bolstering formerly incarcerated young Black men’s educational resilience through a culturally promotive curriculum in the context of an alternative school.

1. Introduction

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement has raised awareness of the endemic racial injustice Black Americans experience (). Anti-Black racism is embedded in all social systems in the United States (U.S.) and is acutely evident in the criminal justice and education systems (). Traditional public education in the U.S. often perpetuates multiple forms of racism that specifically target Black students and are associated with young Black men’s dramatic overrepresentation in the criminal justice system (; ; ; ). A potential means of counteracting the pervasive anti-Black educational discrimination and structural racism in U.S. schools is the adoption of culturally promotive curricula—which center racial equity and positive racial identity development. Culturally promotive curricula have been shown to have broad positive effects on Black students’ cultural, social, and academic development (; ; ), and to help cultivate inclusive learning environments in which they feel respected, connected, and invested in their school communities (; ; ). The importance of culturally promotive curricula is particularly salient among formerly incarcerated Black students, for whom experiences in the traditional public school system are often beset by a confluence of discrimination experiences and racist structural barriers that circumscribe school engagement, marginalize scholastic identities, and impose barriers to school completion. Moreover, formerly incarcerated young Black men often face substantial barriers to reentering traditional school post-incarceration (; ). Some may therefore enroll in alternative schools as a last option to earn a high school diploma or General Education Development (GED) credential. However, little is known about the ways in which alternative schools are structured to promote academic success among these young people (; ). Yet, given their non-traditional approach to teaching and learning (; ; ), alternative schools may offer an important opportunity to examine how culturally promotive curricula can foster a reconceptualization and reconstruction of educational spaces that promote educational resilience, positive racial identity development, and academic success among this population. As such, guided by educational resilience (), intersectionality (; ), and a social constructivist epistemological framework (), this intrinsic qualitative case study explored the ways in which an alternative school’s culturally promotive curricula facilitates educational resilience among formerly incarcerated young Black men.

2. The Impact of Anti-Black Racism on Black Students

Anti-Black racism is foundational to the social fabric of the U.S. (). Critical Race Theory (CRT) asserts that anti-Black racism is centrally concerned with institutional power, and entrenched anti-Black racism within public institutions functions as a form of social control that promotes and maintains White supremacy (). () also posits that race is “an organizing principle of social relationships that shapes the identity of individual actors at the micro level and shapes all spheres of social life at the macro level” (p. 3). The persistence of anti-Black racial discrimination in schools can therefore be viewed as an emergent property of systemic racism in the U.S.—in which race-linked disparities in multiple domains such as poverty, health, housing, policing, and education are connected through reciprocal causation within an overarching racial discrimination system ().

Anti-Black racism is deeply rooted in the way the American public education system was constructed (; ; ). Black youth in traditional educational spaces encounter extensive social, cultural, and political obstacles that hinder their academic and social progress. Some of these obstacles include exposure to physical and psychological violence (), oppressive teachers (; ), over-policing, tracking, over-surveillance (), and racist microaggressions (). Traditional Eurocentric school standards and curricula also promote racist tropes that depict Black students as “dangerous” and undermine their cultural identity (; ; ; ). Black youth within traditional school settings are often pathologized and viewed as deficient (), leading to low expectations from teachers (), and are overrepresented in special education (). They also disproportionately bear the brunt of exclusionary school discipline (), and have substantially lower rates of school completion in comparison to than their White peers (), all of which are reciprocally associated with heightened interaction with the criminal justice system (). In short, anti-Black racial discrimination undermines Black students’ school engagement.

School engagement—which describes the nature of the relationship between a student and the school experience—is widely considered to be an essential component in the academic and social success of young people in the U.S. (; ). School engagement is generally understood as multifaceted and encompassing behavioral, emotional, and cognitive components (). Anti-Black bias damages all three components of school engagement. The differential use of exclusionary school discipline undermines behavioral engagement, barring Black students from participation in school activities. Culturally insensitive and diminishing curricula undermine cognitive engagement (; ; ). Racial bias undermines emotional engagement and the ways in which educators and schools develop relationships with Black students, which deleteriously affects the way in which Black students understand themselves in educational spaces (). School engagement is also undermined through discursive processes operating in Black students’ educational ecologies such as deficit-based language, barring the use of African American Vernacular English (AAVE), and a myriad of subjective school policies such as dress codes (; ; ). For instance, anti-Black racism is often embedded in public school dress code policies and leads to Black students being unduly reprimanded and barred from school activities for wearing culturally affirming hair styles or clothing (e.g., dreadlocks, braids, headwraps, cornrows, etc.) (). These discursive practices differentially expose Black students to school discipline and undermine Black students’ school engagement. Decreased school engagement is associated with negative outcomes such as dropping out of school () and contact with the juvenile justice system (). This highlights the systematic processes through which endemic racism is ubiquitously dispersed across Black students’ educational ecologies and manifests in the school-to-prison pipeline phenomenon ().

Anti-Black racism is conspicuous in the school-to-prison pipeline (SPP) phenomenon (). The SPP refers to the reciprocal relationship between educational and criminal justice institutions that pushes students out of school and toward incarceration, disproportionately targeting Black students, especially young Black men (; ). The racial disparities highlighted by the SPP attest to the way American educational institutions center dominant, Eurocentric, and anti-Black approaches to pedagogy and behavioral expectations that harm Black students’ development within schools. Indeed, the SPP is driven by longstanding structural anti-Black racism and institutional practices in schools. These practices were accelerated by “zero-tolerance” policies that were adopted by many public schools following the enactment of the 1994 Gun-Free School Act (GFSA)—and incited by coded racist language such as that used by former First Lady Hillary Clinton when she referred to Black youth as “super predators” (; ). Enacted under the aegis of school safety, zero-tolerance policies increased the use of exclusionary school discipline, undermining school engagement, and channeling Black students away from graduation and toward carceral discipline (). Zero-tolerance refers to the use of mandatory punishments for violations of school rules that are sanctioned without regard for contextual factors and function to criminalize minor infractions. Zero-tolerance policies are also associated with increased security protocols in schools such as the increased presence of School Resource Officers (SROs), metal detectors, surveillance equipment, and other carceral appurtenances (; ). These policies are targeted at Black students (; ) and are associated with increased student arrests (). Subsequently, Black youth, particularly young Black men, are arrested at disproportionately high rates, comprising 35% of all juveniles arrested in the U.S, while constituting only 15% of the U.S. under 18 population ().

In its wake, the SPP leaves many young Black men disconnected from educational opportunities and severely traumatized (; ). As such, formerly incarcerated young Black men comprise a group of learners with complex educational needs, for whom the risk of dropping out of school or recidivism is increased (; ). The incarceration of these young people has broadly iatrogenic impacts—with wide-ranging deleterious consequences to psychosocial development and the risk of future criminal justice involvement (). In particular, incarceration during adolescence and early adulthood relegates key developmental processes related to the self-regulation of impulsivity and aggression, the ability to view things from multiple social and temporal vantage points, and the development of autonomy (). Incarceration also generates and intensifies academic struggles (), which can have lasting effects on formerly incarcerated Black student’s educational and life trajectories and outcomes.

3. Culturally Promotive Curricula and Formerly Incarcerated Young Black Men

Due to the racially discriminatory policies and practices formerly incarcerated young Black men face in educational settings, many often disassociate themselves from these spaces as a protective measure in response to the trauma they have experienced (; ). There is therefore a vital need to rethink and recreate educational spaces, including curriculum, in a way that is affirming and cultivates healing for these young people. Afrocentric education, for example, centers and represents African ideals, values, and beliefs throughout the curriculum and classroom attempts to empower Black students (; ; ; ). Studies find Afrocentric school curriculum and practices to have a positive impact on Black students’ self-esteem and love of self, independence and self-reliance, sense of self-determination and motivation in school, and commitment to serve their communities (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). Rethinking and recreating a school curriculum that is culturally promotive may therefore be a potential means of counteracting the pervasive anti-Black educational discrimination and structural racism formerly incarcerated young Black men have faced.

In particular, the integration of culturally promotive curricula in schools provides opportunities for formerly incarcerated young Black men to collectively deepen the racial, ethnic, and cultural identities. Namely, culturally promotive curricula focus on centering the lived experiences of students and acknowledging the multiple intersecting identities through which they navigate their social environments. This affirmation-based approach creates opportunities to self-direct learning toward content that is culturally relevant to and affirm their unique positionalities, which promotes intellectual, moral, and emotional development, and positive self-conception (; ; ). Encouraging them to collaboratively develop an individualized curriculum also centers their agency, which offers them an opportunity to cultivate skills in self-determination, goal construction, and leadership that are integral to healthy psychosocial and racial identity development (; ; ; ; ; ). Additionally, it engages a holistic approach by centering relationship building among students and school staff, helping to build school climates in which they can flourish academically and access resources and support vital to reducing reentry barriers and promoting academic success (; ).

Culturally promotive curricula facilitated by teachers and school staff members who are racially representative of their students can also help support the development of strong positive relationships among formerly incarcerated young Black men and their teachers. This approach to teaching and learning presents an opportunity for them to establish a reimagined version of student-teacher relationships that are rooted in cultural relevance as well as a “love ethic” that recognizes their humanity (). Moreover, literature documents that higher ratios of Black teachers in schools are associated with increased social and emotional engagement, fewer disciplinary problems (), and higher academic achievement for Black students ().

These positive impacts suggest that culturally promotive curricula that focus on Black people and Black history have the potential to radically alter formerly incarcerated Black students’ educational trajectories, with far-reaching positive effects across their social ecologies (; ; ; ; ). Embedding culturally promotive structures within school curricula can help to ensure the learning process meets formerly incarcerated young Black men’s educational needs and simultaneously provide developmental benefits derived through the process of participating in the development itself. Formerly incarcerated young Black men who are in the transition to adulthood (18–25) may likewise benefit from educational settings guided by culturally promotive curricula. However, little is known about the ways in which a culturally promotive curriculum promotes development, resilience, and academic success among these young people.

4. School Reentry and Alternative Schools

Despite federal law requiring correctional facilities to offer educational supports and programming (), formerly incarcerated youth are frequently released from carceral placements with substantial educational deficits (; ). In addition, there is often a lack of collaboration and communication among justice and educational systems (), and formerly incarcerated youth face substantial educational discrimination when they attempt to reenroll in traditional public schools’ post-incarceration (; ; ). When enrolled, these young people often arrive at school without the necessary documents required for reenrollment, such as academic transcripts and identification cards (). Age restrictions also often bar formerly incarcerated youth from reentering traditional public schools after incarceration (). Moreover, schools frequently fail to accept the academic credits that these youth may earn in correctional education programs, and correctional facilities do not always provide accurate academic records (). Studies have also reported that formerly incarcerated youth are typically reenrolled during the middle of an academic term and have limited time and support to catch up on course material that was previously covered, increasing the likelihood of school dropout (). Due to the negative stigma that is associated with having a juvenile record, schools are also often reluctant to admit formerly incarcerated youth, as they fear their criminal status and low academic performance will adversely affect performance on state-wide standardized tests linked to funding (Feierman et al. 2009. This often leads to the inability to reenroll in school following incarceration, which negatively affects formerly incarcerated youth’s ability to successfully reintegrate into their communities.

For formerly incarcerated Black students, especially young Black men, alternative schools are often among few accessible means of acquiring a high school diploma or GED post-incarceration and accessing vital services and supports (e.g., legal and case management services) that help to buffer their school reentry challenges (; ; ; ; ). Given their comprehensive and non-traditional approach, alternative schools have become a key dropout prevention strategy for students in many states facing risk factors that impede their educational progress and health and well-being (; ; ; ; ). Although available data on alternative school student success are limited, one study found repeat 11th and 12th grade California High School Exit Exam-takers (CAHSEE) enrolled in alternative and traditional schools to perform identically on the language arts component of the exam (). Qualitative studies also found alternative schools that foster positive teacher and peer relations, high expectations and responsibility, and an understanding of the social-cultural issues impacting their students’ lives to facilitate learning and coping, a sense of belonging and safety, and academic achievement (; ; ). Alternative schools are therefore likely an important setting to examine the potential for implementing culturally promotive curricula that can foster a reconceptualization and reconstruction of school for formerly incarcerated young adult Black students that promote their development, resilience, and academic success. However, literature is limited concerning the ways in which alternative schools implement culturally promotive curricula, or the contextual features, practices, and processes of these educational spaces that are most influential in promoting formerly incarcerated young Black men’s development, resilience, and academic success.

5. Present Study

Given the limited knowledge concerned with the protective mechanisms within alternative educational settings that can enhance the academic success of formerly incarcerated Black students, the present study explored how a culturally promotive curriculum in one alternative school bolsters the resilience of young Black men who reentered school following a period of incarceration. Educational resilience, which is defined as “the heightened likelihood of success in school and other life accomplishments despite environmental adversities brought about by early traits, conditions, and experience,” guided this study as it identifies three important school and classroom protective factors (viz., supportive and caring relationships, high expectations, and meaningful opportunities for participation) that promote resilience and protect against risk factors associated with school disengagement and incarceration (e.g., suspension/expulsion; substance abuse, etc.) (; ; ; ; ). This study also draws upon intersectionality as it provides an additional lens to better understand how overlapping and intersecting power relations influence how the individuals in educational settings experience and perceive a culturally promotive curriculum and the extent to which it can enhance the academic success of young adult Black men with histories of incarceration (; ; ; ). As such, the specific research question includes: What are the elements of an alternative school’s culturally promotive curricula that cultivate educational resilience among formerly incarcerated young adult Black men?

This research is important because young Black men in particular have significantly higher school disengagement and recidivism rates nationally and face numerous barriers and discrimination in their attempts to reenroll and remain engaged in school. A focus on resilience also shifts the attention away from deficits towards the protective mechanisms and processes embedded within educational institutions serving formerly incarcerated young people that can help to redress racial and gender disparities in school disengagement, incarceration, and recidivism. Moreover, because the subjective experiences and voices of formerly incarcerated young Black men are often absent from the literature, research examining their experiences with an alternative school’s culturally promotive curriculum can elicit important knowledge about the ways in which they understand and cope with school reentry obstacles and if they perceive the curriculum as protective and promotive. This research is also innovative in that it uses unique frameworks to understand young men’s experiences around academic possibilities and criminal background situations that previous research has only done sparingly. The attempt to locate this analysis in one alternative school setting also allows for a more organic assessment of how strength and culturally based alternative learning spaces can promote the academic success of formerly incarcerated young adult Black men.

6. Methods

An intrinsic qualitative case study was employed to better understand how educational resilience is fostered and cultivated among formerly incarcerated young adult Black men through one alternative school’s culturally promotive curricula (; ; ; ). This study is part of a larger case study that explored the elements of an alternative school that promote positive school reentry experiences among formerly incarcerated young adults. This approach was useful for exploring the research question posed because it is best suited when the aim is to gain an in-depth understanding from an unusual or unique information-rich source in its real-life context. According to (), theory informs how case studies are conceptualized, wherein social constructivism served as the guiding epistemological framework for this study.

Social constructivism is a learning theory developed by () that emphasizes the collaborative production of learning derived through cultural contexts. Social constructivism posits that learned knowledge is the product of meaning-making processes co-constructed and situated within dynamic social environments. Students’ identities and their unique intersections frame the way they navigate and understand their educational environment and how they interpret academic content. Examining culturally promotive curricula through this epistemological lens is efficacious as culturally promotive curricula explicitly center the creation of individualized learning opportunities among students and shift the role of teachers from instructors to facilitators. Students are thus encouraged to meaningfully participate in the construction of their own learning activities while teachers provide scaffolding—continually engaging students to dialectically synthesize knowledge acquisition rather than unidirectionally instructing students. The individualized nature of culturally promotive curricula therefore ensures that learning is not a one-way process (). This discursive shift to “teachers-as-facilitators” rather than “teachers-as-instructors” reframes learning as co-constitutive. Learned knowledge is therefore understood as dynamic and culturally bound as learners and facilitators co-construct new understanding based upon their preexisting knowledge, context, and collaborative reflection processes (). Accordingly, the concept of a culturally promotive curriculum is understood as bound within the manner in which it is shared and reified between students and teachers and amid the unique social environment situating its implementation (; ). This epistemological understanding of learning frames this study’s analysis of the elements of the school’s culturally promotive curriculum that augmented students’ educational resilience.

7. Researcher Positionality

Acknowledging that a researcher’s identities, experiences, and beliefs influence the research process from conceptualization to dissemination, we, the authors, discuss our positionalities in relation to the topic explored in this study (). The first author identifies as a Black man and university professor whose research examines the risk and resilience processes of justice-involved young Black men and the mechanisms within educational, community, and correctional settings that are promotive and protective. This research is driven by his belief that educational institutions are inherently racist, and that racial and ethnic equity-informed strategies can buffer the impact of racial trauma and cultivate Black students’ development, resilience, and educational persistence. These beliefs are based on his own racialized experiences in educational settings, role as a classroom counselor providing behavior modification support, and the host of deficit-based educational research on and with Black students. While his positionality situates him as an insider in this study, he acknowledges that his position as a university researcher makes him an outsider, as well as the fact that he has never experienced physical incarceration, attended an alternative school, or participated in a secondary learning environment that uses a culturally promotive curriculum. The first author conducted all school engagement and data collection, was the primary analyst of all data sources, and was reflective of these characteristics throughout the study period (i.e., memoing).

The second author identifies as a White-Hispanic male. Accordingly, he considers himself an outsider with respect to the lived experiences of formerly incarcerated Black students. His goal through this study was to contribute to amplifying the voices of young people in our communities who too often are not heard from in academic research. These voices are crucial to the creation of more efficacious and just educational supports and resources that counter deficit-based educational narratives and highlight the need to dismantle and reimagine educational systems with racial and socioeconomic equity and social-emotional learning principles centered. The third author’s position within this world as a Black mxn who grew up in the educational system, experienced various youth programs, and served as an educator for Black youth, influences the ways in which they understood and engaged with this study. He came to this research having experienced many of the programs, experiences, rules, and norms that the participants experience. Furthermore, his views and experiences are what informs how he participated in interpreting as well as conveying the study’s important messages. The love that he has for Black people and Black youth is a part of a long ancestral lineage that will not and cannot be uprooted. This love informs the ways in which they view the possibilities of education for Black youth in the midst of immense oppression from various directions.

8. Case Study Site

Founded in 2004, New Directions (pseudonyms are used for the case site and study participants), a nonprofit community-based organization in Los Angeles County that provides mentor-based creative arts and educational programs, including poetry, music production, gardening, and fitness to justice-involved young people (13–25), served as the case site for this study. While New Directions has primarily provided services and support to incarcerated young people since its founding, in 2015 they partnered with a charter school organization to launch a community-based alternative school as a way to address the cycle of re-incarceration and recidivism. New Direction’s alternative high school is structured around five key developmental areas, including academic instruction, counseling and leadership development, community service, vocational training, and post-secondary placement. The school’s curriculum is identified as culturally promotive because it uses an individualized and project-based approach to learning where students learn and critically reflect upon their own cultural, social, and political histories. In particular, a creative writing program that is based on the California Common Core Standards is embedded into the school’s curriculum, wherein students have the opportunity to learn the structure of poetry and how to write and perform their own poems, and learn how to create musical beats to their poetry using the school’s recording studio as they engage in the learning process (). The school is designed to serve 100 young people between the ages of 16 and 25 and operates year-round. To graduate, students must earn a total 210 credits in core (i.e., English, history, mathematics, science) and elective courses (i.e., health/physical education (P.E.), economics, vocational education). Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristics and experiences of the 117 students enrolled in New Directions during the study period (March 2016–2017). According to school reports, each year less than 5% of students recidivate, more than 80% improve their grade point average, and 10 earned enough credits to graduate during the 2016–2017 academic year.

Table 1.

Summary of New Directions’ student characteristics.

9. Sampling and Recruitment

A purposive, convenience sampling approach was used to identify the alternative school site for this study (; ; ). Site selection criteria included: (a) located in Los Angeles County, (b) offers a high school diploma/GED program and vocational training, (c) serves formerly incarcerated young adults between the ages of 18 and 25, and d) utilizes a culturally relevant, strength-based approach. Thus, New Directions emerged as an intrinsic case for this study because its target population, strength and cultural approach to teaching and learning, and geographic location positioned it as an information-rich source (; ; ). To recruit New Directions, the first author facilitated an informational meeting with the school’s administrators, educators, and social workers. He was introduced to these individuals by a colleague familiar with the study and alternative school. During the recruitment meeting, the first author answered questions these individuals had about the study, and upon agreement of a research plan, the study began with New Directions in March 2016. This study was approved by the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Institutional Review Board (IRB).

10. Data Collection

10.1. Participant Observation

Observational field research, in particular participant observation (conducted by the first author), was the main mode of data collection for this study (; ). Over a period of one year (March 2016–March 2017), 33 observations of New Directions’ educational program were conducted for a total of 97.1 h. Given New Directions’ culturally strength-based and arts and leadership approach, observational activities also included visual and performing arts programs and performances, vocational and employment activities, staff and student meetings, field trips, and a graduation ceremony. Each observation session lasted 3.5 h (on average) and included five school personnel (e.g., teacher, social worker, administer) and approximately 19 students, of which five were formerly incarcerated young Black men. During each observation session, close attention was given to the school’s physical setting, schoolwide and classroom activities and discussions, and interactions and conversations among and between the various actors (i.e., students, administrators, teachers, counselors, community partners, etc.), with a particular focus on formerly incarcerated young Black men. During the first six months of the study, participant observations were conducted one to two times per week. This was scaled down to one to two times every other week for the subsequent six months to allow time for other data collection activities. Field notes, which included a description of the first author’s direct observations, reflective impressions, experience as a researcher, and future observation activities, were recorded using a pen and notebook and then expanded into a Microsoft Word document within two days of each observation. When possible, digital photos of the school’s physical space and student work were also captured. Each instructor (n = 5) that was approached to participate in the study agreed. Since students were not individually consented, the first author facilitated an oral consent process by reading the study script at the beginning of each class session. Students who agreed to participate were asked to indicate their choice by raising their hands.

10.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

Interviews with New Directions’ executive director, academic instructors (n = 2), and students who were a formerly incarcerated young adult Black man (n = 8) were also conducted to answer the research question posed. Convenience and snowball sampling approaches that included a purposive selection process were used to identify potential participants because the first six months of field observations allowed the first author to identify individuals at New Directions who were instrumental in describing the elements of the curriculum that are critical to cultivating formerly incarcerated young Black men’s educational resilience as they navigate school reentry (; ). Young Black men who were between the ages of 16 and 25, released from a correctional facility in the past five years, enrolled in New Directions for at least three months, and had not earned a high school diploma at the time of the first interview were eligible to participate (see Table 2). Recruitment activities included announcements at staff meetings, posting flyers, and consulting with the lead case manager who oversaw student files. A one-on-one recruitment presentation was then conducted with each potential participant using the informed consent.

Table 2.

Formerly incarcerated young Black men participant characteristics.

Each interview was conducted in a private room at New Directions using a semi-structured interview guide. The interview with the executive director explored New Directions’ organizational history, structure, and culture, including its mission and vision, service model, and approach and impact with justice-involved young people. Academic instructors were asked to describe their teaching philosophy and pedagogical approach, and the influence they perceive these to have on the experiences and outcomes of formerly incarcerated young Black men. Interviews with the young men focused on their perceptions of their life and school experiences prior to enrolling in New Directions and the elements of the school and curriculum that positively influence their school reentry process. Interviews ranged from 30 to 90 min and a $25 gift card was provided as an incentive. Formerly incarcerated young Black men (n = 4) who participated in two interviews were provided an additional $35 gift card. We also note that none of the young men recidivated or earned enough credits to graduate during the study period.

10.3. Document Reviews

A review of documents was also conducted as part of this study. This included organizational documents (e.g., reports, policies and procedures, lesson plans, newsletters), recruitment and enrollment documents, school and class handouts, and student work. Digital and hardcopy media documents and news clippings were also reviewed, and digital images of the school’s physical setting were captured and reviewed. This activity helped to develop a better understanding of New Directions’ structure, culture, and practices, and how these, especially in relation to the curriculum, helped to cultivate resilience among formerly incarcerated young Black men.

11. Analysis

Informed by educational resilience, intersectionality, and social constructivism, an embedded thematic analysis of New Directions’ curriculum that used grounded theory techniques (i.e., constant comparative method) and followed a six-phase analytic process was conducted (all data sources were analyzed and interpreted by the first author) (; ; ). Each typed observational field note, professionally transcribed interview, and digital and scanned hardcopy document was uploaded into Atlas.ti (). The first author first immersed himself in the data by reading typed field notes, interview transcripts (with recorded audio), and documents in Atlas.ti, and completing an analytic memo that discussed preliminary codes, emerging themes, and reflexive commentary. Next, an initial codebook was developed with the codes generated in phase 1 (familiarization) and a priori codes that were derived from the research questions, theories, and interview protocols. All data sources were then coded using the codebook, which was consistently refined throughout the analytic process. To search for and define themes, individual codes were collated into thematic categories that described patterns in the data, and all relevant data sources and codes and categories were then compared to identify preliminary themes. The first author also wrote analytic memos to discuss and identify the essence of each theme, supporting quotes and artifacts, and the relationship between themes. Prolonged engagement, peer debriefing, reflexive memoing, and triangulation were used as strategies to increase rigor and trustworthiness ().

12. Results

The overarching theme, “traditions are just not for me,” refers to New Directions’ culturally promotive curriculum as one element of the alternative school that fosters and cultivates educational resilience. Specifically, New Directions offered students several opportunities for meaningful participation and time to build caring and supportive relationships. For instance, in the following quote, Chris, a formerly incarcerated young Black man who attended multiple traditional schools prior to enrolling in New Directions, identifies the important role the non-traditional curriculum plays in his school reentry process. He stated:

I was sitting in my bed [at the sober living home], and I knew I wanted to do better for myself, but I didn’t know how to … So one day, one of my housemates gave me the brochure to New Directions and was like, ‘you need to go back to school.’ So I called New Directions, but I was kind of skeptical because I was 24 and I didn’t really know if this was for me . . . I’m like this might be a traditional school, and I’m not with traditions because over the years, experience let me know that traditions are just not for me … so school for me, anything that was traditional I couldn’t do. That’s probably what had me feeling stuck over the years … I need something that was more with me.

As such, two subthemes, “teaching the truth” and “going at my own pace”, describe and explain how New Directions’ culturally promotive curricula foster and cultivates educational resilience among formerly incarcerated young Black men.

13. Teaching the Truth

“Teaching the truth”, which refers to pedagogies that incorporate the histories, texts, values, beliefs, and perspectives of people from diverse cultural backgrounds, is one example of how New Directions fostered opportunities for meaningful participation. For instance, when describing his teaching philosophy, Mr. Brown, a Black teacher, explained that he intentionally integrates content concerning the history and experiences of racial/ethnic groups in his class activities. He stated:

I come with a great deal of humility and an understanding that I don’t know everything.… The second thing I do is that I try to make sure that I’m always teaching the truth. I get away from the standard text, and the standard way of doing things, and try to get into why things have become standard. Why are these tests so standardized? Why is Columbus Day, Columbus Day? … You can tell me that Thanksgiving is Thanksgiving, and then we can all eat turkey, but you’re not going to tell me it was a massacre. So, I’m talking about the massacre in my classes.

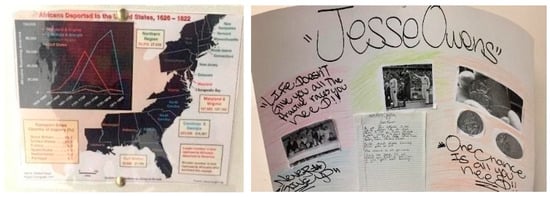

As such, throughout the observations, Mr. Brown engaged the students in a range of learning activities that included a cultural component. For example, Figure 1 displays images of students’ project-based learning history projects that were posted throughout Mr. Brown’s classroom. For one activity, students developed timelines that traced the deportation of African slaves to the U.S. Additionally, during the 2016 summer Olympic games, Mr. Brown had students develop poster board-sized profiles of prominent racial/ethnic minoritized gold medalists who participated in the 1936 Olympic games, such as Jesse Owens.

Figure 1.

Students’ cultural history projects.

These reflective and hands-on cultural activities appeared to address the students’ needs for meaning, belonging, and mastery, which kept them engaged in the learning process. For instance, the following field note excerpt describes an interaction the first author observed between Mr. Brown and two young Black men in his history class that involved a critical discussion of how they might approach their anti-oppression history project.

When I arrived at the class, the students were working on research projects that were based on a historical anti-oppression person, group, or event. Instructions to the assignment were written on the white board, and read, ‘Do Now: Project based on historical anti-oppression person, group or event.’ In particular, students were to: (1) ‘Discuss who you’d like to research and why;’ (2) ‘Write it down;’ (3) ‘Grab a computer and research the group, person, or event;’ and (4) ‘Discuss who, what, when, where, how, and why in the research project.’ I got the sense that not many students worked on this project over the past week, as students were still asking Mr. Brown how to approach the assignment.

To help the students, Mr. Brown used Martin Luther King as an example of a person who was against oppression. Sam, a 25-year-old young Black man who was formerly incarcerated added to Mr. Brown’s example by stating that he might conduct his project on the untraceable gun that killed Martin Luther King. Mr. Brown redirected this conversation to get the students to think in terms of his birth and death, why he was killed, and the many issues surrounding why he protested. This conversation soon led to a discussion about race, slavery, and mass incarceration, wherein Sam further expressed, ‘It’s all about the poor,’ meaning that the issues Martin Luther King attempted to address were focused on poor people. Sam also pointed to the issue of race by saying, ‘Why can a White man get a job better than a Black man even if he doesn’t have a PhD?’

The conversation about Martin Luther King, race, and mass incarceration soon led to a discussion about the prison industrial complex as a potential research project. Mr. Brown asked the students to explain what they knew about the prison industrial complex. Another young Black man, Victor, explained ‘Prisons are like a WingStop franchise.’ Mr. Brown and the students then began to talk about prison conditions, such as overcrowding, wherein Victor said, ‘people sleeping on the floor is against human rights.’ Following the student’s comments, Mr. Brown asked them to develop an argument for their anti-oppression project, based on their discussion. Sam, replied aloud ‘Prisons only target people of color.’ Mr. Brown nodded and verbally agreed by saying, ‘yes, that would be a good topic to pursue.’—Field Note, 4-13-16

As noted in the above field note, socio-cultural learning activities appeared to play a key role in the schooling experiences of formerly incarcerated young Black men at New Directions. In particular, in this example, Mr. Brown incorporated a culturally relevant activity that was built on the students’ interest and knowledge regarding incarceration. This not only kept the students engaged in the learning process, yet, in many ways appeared to enhance their understanding of the issues affecting their life chances and opportunities. The discussion between Mr. Brown and the two young Black men also appeared to evoke a process of critical thinking, which seemed to bolster the young men’s, particularly Sam, problem-solving skills and self-efficacy concerning his anti-oppression project. Moreover, discussions of race in relation to the criminal justice system highlighted the ways in which the young men perceived their racial/ethnic identity and, in some cases, status as a formerly incarcerated person to shape their opportunities and outcomes.

The interviewees also pointed to New Directions’ cultural approach to education as a key element of the non-traditional curriculum that supported their school reentry processes. For instance, Robert expressed that he is “a better individual” because he now attends a school where he learns about his history and culture. He stated:

I’m a better individual because my mindset is different. Back then I didn’t even know a lot about my history … and now I know that. But one thing that New Directions did is that I got to learn about the things in my culture…. Like, in a regular unified school district I feel like a kid loses. One he loses because he gets to be taught what the government wants him to. Not the truth. But at my school [New Directions] we dig deeper into the subject than just Africans being slaves. We go way deeper than that. We get to learn about Egyptian history. Like, I didn’t really know anything about Egyptian history. I knew that we were Black kings, but I never had the encouragement to go deeper into finding out who I am, and that’s what our school does. We learn about who we are and why we are special.

This example helps to illuminate how teaching the “truth,” that is, education that incorporates the histories and beliefs of racial/ethnic groups, helped to enhance some young Black men’s self-awareness concerning their cultural background and history. In Robert’s case, engaging with a curriculum that incorporates his cultural background not only motivated him to participate in the learning process, it also enhanced his sense of self, particularly regarding his racial/ethnic identity. This was emphasized when he stated, “…I never had the encouragement to go deeper into finding out who I am, and that’s what our school does. We learn about who we are and why we are special.”

Critical to keeping the young men motivated and engaged were instructors who also reflected their cultural backgrounds. In particular, the young men felt that the instructors’ racial/ethnic background and shared interest in the arts helped them to feel “comfortable” in the class setting. For instance, when asked to describe the teachers at New Directions, Paul expressed:

- Paul:

- The teachers here, they’re cool. They care. That’s all I can say about them.

- Interviewer:

- What makes them cool?

- Paul:

- Well, they’re cool because mostly they try to relate to us, and … like Ms. Jennings, she makes music herself … and she’s in a band. And Mr. Brown, you know, he’s Black. He can relate…. Like he’s a cool older Black man. I can relate to bro … he vouch for me all the time, you know? Ms. Jennings vouched for me all the time so I’m cool with her.

- Interviewer:

- Like, how do they relate to you?

- Paul:

- It’s because Mr. Brown talks about stuff like I’ve been through. He told me about his life. Like he was young and he told me, ‘I was young at a point in time and doing this and doing that.’ He told me he’d been through some crazy stuff. Sounded like what I’ve been through and then Mrs. Jennings, with the music, it’s like, you know?

- Interviewer:

- Yeah, I feel you. Well, how would you say being able to relate to them impacts your schooling experience?

- Paul:

- It’s because I feel more comfortable around them…. Because how do you learn from a person that you don’t like? That’s hard, that’s why I didn’t pass geometry for so long … cause I didn’t like that teacher. I had As, all As in algebra and then when I got to geometry, I failed every class.

Additionally, Joshua expressed that having instructors with similar lived experiences was relevant to keeping them engaged in the learning process. He explained:

Some teachers have similar stories as mine, teaching-wise, and as far as school-wise like going through school, growing up … doing work, having problems … and not coming to school and not showing that I wanna be in this school. They tell me a lot about life, and right there … that’s more important because you learn from your life experiences. You learn from it more because … I had similar situations, not all the same but similar things as far as school. Like, when I didn’t wanna go to school, or I don’t feel like going to school, or I feel like ditching or whatever, they tell us why not to do these things and why we should stay in school so that we could obtain and get to a level that they are at or higher.

As noted in the examples above, the inclusion of instructors who reflected the young men’s cultural and racial/ethnic backgrounds, were interested in the arts, and had similar life experiences helped to foster and cultivate educational resilience. This was important to the young men who learned from both their academic and lived experiences. Thus, because they had the opportunity to include their cultural and life histories as part of the learning process, they perceived their post-incarceration schooling experiences to be more meaningful. Yet, although the young men perceived that including instructors who mirrored their racial/ethnic and cultural backgrounds to be critical to delivering a culturally promotive curriculum, participant observations and interviews revealed that the availability of instructors that reflected these young men’s racial/ethnic identity and cultural backgrounds are limited.

14. Going at My Own Pace

New Directions also fostered and cultivated educational resilience by using an individualized academic approach. The young Black men viewed the schools’ individualized approach to education as an opportunity for meaningful participation, because it allowed them to participate in the learning process at their own pace. For example, in the following quote, Kevin, who checked out of his traditional high school in the twelfth grade, expressed that having the ability to work his own pace was a key motivating factor that influenced his decision to enroll at New Directions. He stated:

I checked out of my high school and came here, because at the rate I was going, I wasn’t going to graduate…. I needed 260 credits to graduate and I had 88. It wasn’t no way in hell I was going to graduate … I was in the 12th grade, and I was like I need to get the fuck up out of here, cause I’ll be damn if the rest of my class walk across this stage and I’m sitting on the sideline. I’d rather be at another school going at my own pace. Graduate with everybody else at my own pace.

Due to New Directions’ individualized approach to education, the young men appreciated that they were allowed to complete their class work in different spaces throughout the school. This served as a meaningful opportunity for several young men, such as Paul, who reported that he often has a difficult time remaining focused and engaged during class. He explained:

Ms. Jennings helped me because like I said I don’t like to be around a lot of people sometimes, it’s cool to be around a lot of people, but sometimes I get trippy … like I start getting anxious and unfocused. So, I told her that and she was like, ‘Well, good that you let me know that we can set up something where you can work in the TA’s room.’ And that was around the time I was actually doing my work. Because I was able to focus. I’m in that class and I’m hearing a whole bunch of ignorant shit, and I’m laughing with it, and I’m making jokes myself so much that I can’t even focus on my own work. So, it’s like, that helped me out a lot.

As described above, the individualized academic approach fostered a meaningful opportunity for Paul to participate in the learning process. This was important to him because being around a lot of people in the classroom sometimes made him “anxious and unfocused.” Yet, New Directions’ individualized approach to education afforded him the opportunity to work outside of the classroom setting, which helped him to remain engaged in the learning process. The ability to work at their own pace and outside the class setting, in many ways, helped to motivate the young men, which in turn appeared to positively influence their academic self-efficacy.

In addition to offering meaningful opportunities to participate in the learning process, the individualized academic approach also serves as an example of how New Directions fostered and cultivated caring and supportive relationships. Specifically, given the self-directed approach, academic instructors generally viewed themselves as facilitators of learning, wherein they guided and assisted students in learning for themselves. For instance, during an interview session with Ms. Jennings, she explained that she sees herself as a coach rather than a teacher:

I’m more of a coach than a teacher. These students are between 16 and 24 years old. We are talking about folks that have kids, folks that have jobs outside of here, and folks that are married.… So, I’m really big on choice culture. I … ask them what do they want to do? How fast do they want to move? How productive do they want to be? … I tell them what their options are, and that my job is to support them and that I’m also going to push them a little bit…. So, I’m like a constructivist…. I can show them the different pieces, but, at the end of the day, they have to construct their own knowledge and skill set.

As Ms. Jennings describes, given the students’ characteristics, particularly their ages and the reality that some are parenting and have other financial responsibilities, the individualized approach to education is suiting, in many ways, for them to balance their educational and personal responsibilities. Moreover, given New Directions’ “choice culture,” power struggles between students and teachers were limited during each observation session, which seemed to help students with developing caring and supportive relationships with instructors.

This “choice culture” also helped to increase opportunities for academic instructors to communicate messages of high expectations. Specifically, throughout the study period, instructors and other school personnel frequently spoke encouraging and affirming messages, such as “you can do this,” to students who were struggling with a particular assignment or activity. These positive messages were also displayed throughout the physical environment of the school, wherein the walls in classrooms and throughout the common areas of the school were covered in various phrases and quotes such as, “never give up,” “Be Awesome Today,” and “In order to succeed we must first believe that we can” (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

High expectation messages.

These positive messages, whether spoken or written, seemed to foster a school climate of belonging, as the first author observed instructors and students repeat these messages as they interacted throughout the learning process. Formerly incarcerated young Black men interviewees also typically described instructors and school personnel as “caring” and “cool,” which highlights that some viewed them as non-authority figures. The young men also expressed that they felt loved and respected by some of the instructors and other school personnel. Feeling a sense of belonging in the school setting and loved and respected by instructors and school personnel was important to the young men because some perceived New Directions’ climate and their interactions with adults and their peers in the school setting to positively influence their optimism, problem-solving skills, and academic self-efficacy. For instance, Chris explained:

They [academic instructors] push me. One day Ms. Jennings gave me a packet of work for algebra. I thought I got all of them wrong because I’m not good in math, so I’m like man this is not good. And I read through the package and I got the majority of my work done right. I was kind of shocked, like man I did this right? I haven’t done math in like forever. That was a push factor for me because … she would tell me like she’s proud of me. You don’t really get that at most schools. Teachers can care less.

As Chris explained, receiving high expectation messages from Ms. Jennings served as a “push factor” for him because he had previously experienced minimal success in math. Additionally, in comparing the level of care he received from Ms. Jennings to teachers in other school settings, he highlights New Direction’s individualized academic approach as a key element of the school and curriculum that influences caring and supportive relationships among instructors and students.

While the young Black men perceived the individualized curriculum to enhance their academic self-efficacy and optimism, it also appeared to motivate them throughout the learning process. This was important because, given their previous schooling and incarceration experiences, they, like other students, arrived at New Directions with low academic skills and competencies. This therefore served as an obstacle to some young men participating in the learning process and persisting academically. The following field note excerpt helps to illustrate this point by describing an observation of Kevin, a formerly incarcerated young Black man who enrolled in New Directions so he could work at his own pace, yet faced challenges when attempting to test out of math.

I recorded the math problem that was written on the whiteboard as the students were sharpening their pencils. While I was writing, Kevin, a slender young Black man who appeared to be 19 or 20, began to negotiate with Mr. Turner, a White instructor, for more credits in math. He asked, ‘what type of agreement can we come to for my credits? Yall give us like .2 credits a day…. If I would have stayed at my high school, I would have graduated yesterday…. I thought I would have been done by now…. Can I test out of math?’ Mr. Turner responded by informing Kevin that he can test out of math, however, he has to pass the 13 exams with 75% or better. Kevin agreed that he could do this, grabbed a book, and began to work. About 30 to 45 minutes into class, Kevin yelled aloud, ‘Oh my gosh, this is only chapter 5?’ He began to flip through the pages of the book to get a sense of how much he would have to complete. Mr. Turner noticed what Kevin was doing and explained to him that this would likely take several days to complete, even if he worked on it relentlessly. I noticed Kevin lower his head as if he felt defeated, and he then expressed aloud, ‘damn that just crushed my spirit…. I’m going home…. I’m going to be honest; I don’t even think I can do it.’—Field Note, 6-2-16

Chris, Joshua, and Paul, also described their ability to remain engaged in the learning process as a challenge, given their low academic achievement. Specifically, these young men expressed that being disconnected from school for a long period of time sometimes caused them to feel frustrated and resentful as they participated in the learning process because they often struggled academically or had trouble sitting in class for long periods. Paul, for example, expressed, “I feel like I’m so set back…. I’ve been in high school for so long…. I really let my past plague my life”.

New Directions’ school personnel and instructors also perceived students’ previous schooling and incarceration experiences to negatively impact their academic self-efficacy and self-esteem. They also believed that these past experiences often deterred them from the opportunity to engage with an individualized curriculum that is designed to help address their school reentry obstacles. For instance, while describing the strengths and challenges of students enrolled at New Directions, Ms. Moore, the executive director stated:

I think a lot of times they’re … just coming from failing schools and systems that have failed them to where they are not at the same level, academically, as the other students. I think that has an effect on their self-esteem at times. And when they’re not able to achieve or not being given the opportunity to achieve in the way that they can, they shut down. And so, you’ll find them wandering the hall, they’re talking to staff, you’ve seen it, hanging out.

Field observations reinforced this theme. The excerpt below includes a discussion the first author had with Ms. Jennings about the specific barriers and challenges she perceives to serve as an obstacle to academic achievement for formerly incarcerated youth.

Today was Friday, so most students were working on credit recovery, while others were either in the music studio, on their phone, or sitting around talking with their friends. Because I had not seen Ms. Jennings in several weeks, I decided to stop by her class during lunch, as most of the students walked to the store to grab food. Ms. Jennings and I caught up for a bit, and somehow ended up talking about New Direction credit recovery process and the educational approach. She expressed, ‘One of the flaws of our educational model is that we are taking them [students] from a highly dependent setting [correctional facility] and putting them in a self-directed, choice-based school…. In correctional education programs, students show up and learn because they are always being told what to do. However, in a choice-based school setting, students are forced to learn…. This has been a flaw of the educational model, because they [the students] are so dependent given their experiences in camp…. Camp creates a sense of socialized dependency where students believe they are doing good because they are doing what everyone tells them to do…. Here, students have to take autonomy with their education, but this is hard for some students given the correctional settings they are coming from…. Society says it’s a character flaw if they are unable to achieve successful reentry. But in most cases, the odds are against them.—Field Note, 9-9-16

As Ms. Jennings explains, some formerly incarcerated youth who participate in a self-directed, choice-based academic curriculum will likely experience some obstacles to academic success. This is because, as a result of their highly structured incarceration experiences, some students are unable to fully take advantage of New Directions’ individualized curriculum because incarceration, in many ways, stifles their ability to utilize their personal agency as they have frequently been told what to do, when, and how.

Throughout the study period, New Directions began offering tutoring services for students who needed additional academic support. However, this strategy was implemented towards the end of the study period, wherein the researcher was not able to examine how this element helped to address some students’ challenge with engaging with an individualized approach to education. Nevertheless, New Directions’ individualized approach to educating formerly incarcerated young adults appeared to foster meaningful opportunities for students to participate and build caring and supportive relationships. This element also helped foster a school culture of high expectations, which appeared to bolster student’s resilience.

15. Discussion

The purpose of this intrinsic qualitative case study was to examine how the elements of a culturally promotive curriculum in one alternative school bolsters the educational resilience of formerly incarcerated young adult Black men. Informed by an educational resilience framework, intersectionality, and social constructivism, the results suggested that the curriculum appeared to bolster their resilience, despite the various adversities they faced during the reentry process. A central element of the curriculum was that its structure and culture were interpreted as a form of resistance to hegemonic pedagogy. The formerly incarcerated young Black men participating in this study understood the traditional educational system as hostile to their educational trajectories and well-being, in which one expressed, “I’m not with traditions because, over the years, experience let me know that traditions are just not for me.” This statement was a tacit recognition of the need for counter-hegemonic pedagogies that contest anti-Black educational discrimination and ideological racism embedded in traditional curricula in U.S. public schools (; ). It also represents a cognizance that the traditional educational system is structured in a manner that excludes countervailing truths salient among formerly incarcerated young Black men and does not provide them support they perceive to be beneficial to their lives. Conversely, the results identified several elements of the alternative school’s curriculum that the participants in this case study understood as cultivating the young men’s educational resilience. These elements were summarized in the themes “teaching the truth” and “going at my own pace.” “Teaching the truth” for students represented being taught content that was relevant to their own experiences and being taught that content by teachers with whom they felt had a shared socio-cultural understanding and identity. “Going at my own pace” for students represented the need for individualized, project-based learning opportunities that allowed students to self-direct their learning processes. These themes represent the intersections of process, content, provider, and context that ground the co-construction of learning within culturally promotive curricula.

The findings suggest that including curricular content that affirms the truth of formerly incarcerated young Black men’s experience can help to engage them in the learning process and facilitate critical thinking and self-awareness. As mentioned above, teaching the truth in this context referred to the teaching of truths that were excluded from the traditional, hegemonic educational settings participants previously experienced. Having the opportunity to identify successful Black icons in American history and discuss and develop class projects on mass incarceration and its impacts afforded the young men the opportunity to affirm the potential of their own ambitions for success and critically assess the social conditions impacting their life trajectories and outcomes, which helps to counter the anti-Black racism they had previously experienced in traditional educational spaces (; ). Engaging with curricular content that affirmed the truth of their experiences also helped them to feel as though they had opportunities for meaningful participation within their classrooms, where their visions and ideas were able to flourish, and be integrated into the development of course content and classroom culture. This co-construction of the learning goals and classroom environment suggested culturally promotive curricula may foster school engagement and a liberatory education experience among formerly incarcerated young Black men, which in the traditional American school system had previously been denied them through endemic anti-Black racism (). The increased school engagement displayed by the formerly incarcerated young Black men in this study further suggests that culturally promotive curricula facilitated by teachers who share cultural and racial commonalities may be efficacious in creating positive student-teacher relationships that foster meaningful learning opportunities and bolster educational resilience. It is well established that having Black teachers reduces Black students’ experiences of school discipline (; ) and improves Black students’ motivation and educational outcomes (). Likewise, having teachers they identified with experientially (i.e., artist) and racially provided a form of cultural matching that acknowledges the importance of race and culture in these students’ school experiences (). Having teachers with shared racial identities and socio-cultural understandings also seemed to foster deeper relationships between the young men and teachers, which has been shown to be vital in developing connections to school (). Indeed, culturally promotive curricula require holistic engagement that promotes and encompasses relationship development situated in the lived cultural experiences of the students. These relationships are vital for students’ ability to thrive academically () and this study’s findings underscored the manner in which racial, political, and cultural intersections within educational spaces are bound to curricula and the co-production of learning.

Findings also suggest that encouraging students to collaboratively develop the curriculum offered an opportunity to cultivate skills in self-determination, goal construction, and leadership that are integral to healthy psychosocial development (). Moreover, this study’s findings highlighted the reciprocal relationship between school curricula and these developmental needs as foundational to formerly incarcerated Black men as they negotiate school reentry obstacles and opportunities. For instance, the development of psychosocial maturity (i.e., mastery and competence, interpersonal relationships and social functioning, and self-definition and self-governance) can assist formerly incarcerated young adults with creating and taking advantage of opportunities that support their life goals (). New Directions’ culturally promotive curriculum exemplified this through engaging the young men with meaningful opportunities to participate in the development of their curriculum and organization of their educational space. By offering them the opportunity to conceptualize and create individualized learning plans and classroom environments, they achieved the simultaneous benefits of engaging with a curricular context that was culturally and individually relevant to their interests, and experiencing the developmental benefits intrinsic to the process of conceptualization and creation. Put differently, the young men were able to learn organization, planning, goal construction, and leadership skills when they were given the opportunity to self-direct their learning processes.

At the same time, having teachers encourage them to pursue content relevant to their lives in an educational space they perceived as safe likely motivated them to more deeply engage in identity development that fosters educational resilience. Additionally, the use of culturally meaningful and encouraging messages—through visual signage and affirming language—throughout the school provided a space in which the young men and teachers co-constructed a physical space and school climate that helped them to feel comfortable, supported, and encouraged as they engaged in the learning process. The use of messaging also cultivated high expectations for the young men as they worked with teachers to collaboratively develop their learning goals. This approach influenced teachers to view themselves as facilitators of students’ learning rather than instructors. It is therefore likely that this conceptual shift in teachers’ role (from instructors to facilitators) was embedded in the school’s culturally promotive curriculum and functioned as a key curricular element that the young men identified as beneficial in augmenting their school engagement and educational resilience.

Indeed, this conceptual shift is a central element of the culturally promotive curriculum at New Directions, as teachers are encouraged to coach students throughout the learning process by communicating positive messages and encouraging students who struggle academically to remain engaged. The young Black men in this study alluded that this shift from teachers-as-instructors to teachers-as-facilitators helped develop trusting relationships that set the foundation for high expectations. The positive messaging from teachers was also supported through discursive practices such as motivational signage and student art that promoted academic and cultural strengths. These messages were displayed on the walls throughout the school setting, such as “never give up,” and “be awesome today.” The young men also reported that they perceived these positive and encouraging messages as important elements of the school space that bolstered their academic self-efficacy and optimism. These messages, and their interactions with instructors, were reported to also helping them feel accepted and appreciated. They therefore described teachers as “caring” and “cool” because the messages they relayed helped them to believe in their own skills and abilities, motivating them towards academic achievement.

New Directions also offered students an opportunity to display their own posters and art and to set up the use of classroom space in an inclusive way. This process centered participation, authenticity, and flexibility, and promoted resilience and autonomy amongst the formerly incarcerated young Black men in this study (; ). These elements of the school’s curriculum helped to foster educational resilience through students’ educational exploration, civic participation, and sense of belonging. These findings suggest that these curricular elements helped build a school climate in which students felt liberated to authentically express themselves, vent, create, and heal (; ; ). In this way, this study’s findings support the supposition that the use of culturally promotive curricula among formerly incarcerated young Black men may provide advantages to the development of educational resilience vis-à-vis traditional education curricula. The alternative educational space co-constructed through New Directions’ curriculum, teachers, and students provided a safe respite from the trauma of racism and oppression students experienced elsewhere in their lives.

16. Limitations

This study is limited in several ways. First, this study is subjected to researcher and reactivity bias, as participant observation was the main mode of data collection and all data collection and analysis was conducted by the first author. Additionally, the purposive selection process that included convenience and snowball sampling strategies makes the study subject to selection bias. This threat can further skew the study’s findings, as the data collected may not fully represent the experiences and perspectives of all individuals in this alternative school setting. Moreover, although all eight young Black male interviewees were contacted for a second interview, only four (i.e., Chris, Joshua, Robert, and Kevin) participated in two interviews. It is therefore likely that the perceptions of the young Black men are skewed towards the experiences of the four young men participating in two interviews. Nevertheless, the first author attempted to account for this by using multiple strategies to improve rigor and trustworthiness. This limitation also points to the difficulties in engaging hard-to-reach populations in research, and the need for effective strategies that can address this threat in conducting qualitative, empirical research. Additionally, the unit of analysis was the alternative school curriculum, which did not allow the researcher to observe other influential factors outside the school setting (e.g., family, neighborhood, etc.) beyond the individual interviews that were influential to the formerly incarcerated young Black men’s post-release success. Lastly, although the alternative school selected for the case study offered a unique opportunity for knowledge development, it had only been in operation for eight months at the start of data collection.

17. Conclusions

This study found that New Directions offered a range of meaningful opportunities for formerly incarcerated young Black men to participate in the learning process and supported the efficacy of culturally promotive curricula for enhancing educational resilience, bolstering school engagement, and setting a strong foundation for students’ educational success. Using educational resilience and intersectionality as guiding frameworks, this study uncovered that a culturally promotive curriculum can bolster formerly incarcerated young Black men’s resilience in the face of adversity. This was demonstrated in several cases where the young men expressed that New Directions’ curriculum enhanced their academic self-efficacy and optimism despite the fact that they arrived at school with low academic expectations and identities marginalized by traditional educational spaces. This supports the argument that a culturally promotive curriculum can facilitate educational resilience despite the presence of substantial risk factors. The educational resilience framework and intersectionality are thus important lenses through which to consider the impacts of curricula on the educational experiences of formerly incarcerated Black students. Incorporating components of formerly incarcerated young Black men’s cultural backgrounds and racial/ethnic identity as they participated in learning was also critical to facilitating their engagement in school, academic success, and positive and rewarding relationships. While this study offers important insights, more rigorous research is needed to better understand how and the extent to which culturally promotive curricula within alternative school settings can bolster formerly incarcerated young Black men’s educational and life trajectories over time, and buffer the various risk factors they face to post-release success. This research should also seek to identify the diversity of needs, experiences, and assets and resources these young people embody as they reenter their communities and engage with educational systems, in an effort to improve the development and implementation prevention and intervention strategies with this population.

Author Contributions