Abstract

Why should societies invest resources in humanities, arts, and social sciences (HASS) research? While citizens’ quality of life should be affected by the type and level of cultural amenities they have access to, the broader links between HASS research and its impacts on quality of life attributes can be tenuous because of the research attribution challenge, temporally and spatially linking specific HASS research and its ultimate impact on well-being and society. From a survey of 1920 Canadians, here I report perceived values, awareness of HASS research, threats to quality of life, and levels of community and cultural engagement. The key finding of this exploratory study was that HASS research awareness acted as a powerful predictor of threat perceptions, levels of community activity, and cultural engagement at the local level. It was not, however, a significant predictor of core values. From a theoretical perspective, this is in line with a priori expectations that core values are a precursor to worldviews, threat perceptions, and behaviors. There are very different policy prescriptions for increasing HASS research awareness and, by extension, Canadian citizens’ propensity for cultural and physical engagement, depending on how HASS research awareness affects their threat perceptions, values, and behavior. They include alternatives that focus on experiential learning early in life and adult-oriented awareness-building activities. The strong relationship between HASS research awareness and citizen engagement implies that there are important roles for education and awareness-building activities beyond simply encouraging future consumption of cultural commodities among HASS-aware citizens.

1. Introduction

Why should societies invest resources in humanities, arts, and social sciences (HASS) research? That question is increasingly important for public sector policy makers and funding agencies given competing demands for scarce financial resources. While citizens’ quality of life should intuitively be affected by the cultural amenities they have access to, the links between HASS research and impacts can be tenuous because of the research attribution challenge, temporally and spatially linking specific research activities and their ultimate impacts on quality of life and society well-being (e.g., [1,2,3]). Furthermore, there are multiple conceptions of the types of value with which HASS research supplies society [3,4], and not all are amenable to current forms of impact evaluation [5]. Adding further complexity, the need for engagement of HASS scholars in transdisciplinary environmental change research has also been increasingly recognized [6,7,8,9], as has the potential role of HASS research in value adjudication in complex environmental management challenges [10]. Cross-disciplinary engagement on broad societal challenges beyond the traditional HASS domain is still largely lacking (e.g., [11]) but as levels of cross-disciplinary integration increase to address pressing environmental challenges, attribution will only become a more vexing issue.

It is already challenging to build a “business case” to fund and sustain HASS research, especially for governments that are focused on “value for money” (i.e., looking for outputs that contribute to technological development and economic growth) and academic institutions shaped by funding tied to impact evaluation frameworks [5,12]. HASS research has been viewed as not being competitive with other types of science, technology, engineering, and medical (STEM) research [13,14]. STEM research, which may compete for the same pool of limited public funding, has a much more established track record regarding its economic impact [15,16,17] and is also often viewed as central to national innovation policy [18]. As the Australian Council for the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences emphasized [19], in the public eye, the perception is that economic and social benefits are derived mostly from (natural and applied) scientific research and that, until that situation changes, HASS research will be undervalued by society. One approach to demonstrating the value of HASS research has been to quantify the economic impact of the arts and culture industries [1,20,21]. Given the public good nature of many of the quality of life attributes to which HASS research contributes, it may also be possible to quantify the nonmarket economic benefits of changes in specific attributes [22,23,24,25]. As in environmental economics [26], nonmarket values for HASS impacts can be used in cost-benefit analyses (CBA) and may potentially tip the balance in favor of HASS investment. As in environmental economics, there are, however, risks with commodification and “playing the CBA game”. Because it is based on narrow satisfaction of consumer-oriented preferences [27], “valued” and “valuable” attributes (this goes back to Dewey, who argued that to be valuable something needs to be subject to critical evaluation and reflection [28]) can get confused and may not be appropriate when attributes being valued occur at different geographic and temporal scales [29], and can be co-opted by governments with particular ideological agendas [30]. There have also been efforts to position HASS-based creativity as a vital input in the commercial innovation process [31], thus making HASS research more relevant for development of market goods and services. Still, viewing HASS research through an innovation lens is not without its problems [12,32].

HASS research is often oriented towards criticism, broadening thinking, maintaining a diversity of ideas in society, and encouraging deliberation about what constitutes value and knowledge [32,33,34]. It is possible that valuable spin-off benefits may also arise as a result of citizens’ direct engagement in artistic and cultural activities. Benefits from increased levels of citizen engagement could include factors such as increased personal life satisfaction and happiness, improved physical and mental health, expanded social networks, and more resilient and vibrant communities and societies [6,35,36,37,38,39,40]. As Galloway ([41], p. 339) noted, however, “this is an area where policy rhetoric outstrips research evidence”. While HASS research might build society’s capacity for undertaking action [3] and decrease vulnerability (i.e., by increasing adaptive capacity within households and societies), the assessment of the economic benefits arising from capacity-building is currently beyond accounting-oriented logic used in most government evaluation frameworks.

In order to adequately assess the influence of HASS research across a wide spectrum of social and economic impacts thus requires an improved understanding of the contributions HASS research makes to societal well-being—the attribution problem—as well as a diversity of methodological approaches that capture the range of those benefits [42]. In this paper I report results from an exploratory study (n = 1920) on the relationships between Canadians’ values, awareness of HASS research, perceived threats to quality of life, and levels of community and cultural engagement. This topic should be of broad interest in other regions because increasing our understanding of the antecedents of cultural participation and consumption are rather poorly understood and under-researched internationally [43], yet have important policy implications. The results of this study show that HASS research awareness is strongly related to threat perceptions, participation in cultural activities, and levels of community engagement. Furthermore, it is a stronger predictor of those factors than educational attainment or other standard demographic covariates. This suggests that the impact of HASS research amongst the general public may be much broader than typically thought and that research awareness may be a measurable proxy for a deeper variable that broadly affects active citizenship and engagement.

2. Data Generation and Analysis

2.1. Survey Design and Delivery

The focus of this paper is on four specific questions that were part of a national survey that explored willingness to pay for improved quality of life attributes for Canadians [24] (additional details on the rationale for survey design and its implementation are available in that article). In the four questions that are the current focus, survey respondents were asked to: (1) rate their level of agreement with a series of 15 value statements; (2) rate 12 potential threats to quality of life in Canada; (3) indicate whether they were members of any of seven types of community-based clubs or organizations; and (4) indicate whether they participated in any of six particular types of social or cultural activities over the past 12 months.

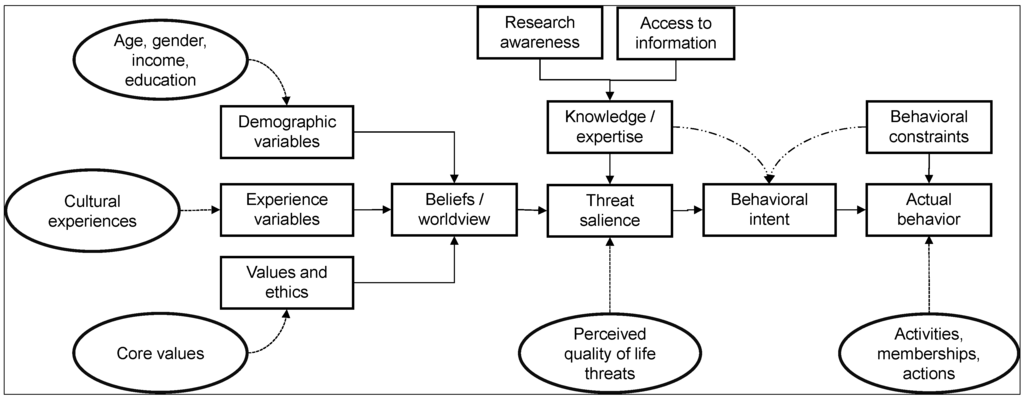

I used a slight modification of value-belief-norm (VBN) theory [44] to inform the survey design (Figure 1). VBN theory hypothesizes that actual behavior depends on a number of different factors, including: core values (enduring perspectives that last much of a person’s life and are heavily influenced by culture and upbringing); worldviews (relatively more malleable perspectives on how the world works); threat perceptions; behavioral intent; and realized behavior. Threat salience can be viewed as a function of worldview, a person’s education and awareness, and access to information. Behavioral intentions are not always realized because various material and social factors can constrain intended behavior. While a worldview-oriented scale based loosely on the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) [45] was developed in Australia [43], I chose to use only the Schwartz-based items [44,46] for reasons of theory (it captures stable, core values rather than more fluid worldviews) and practicality (negative reaction from focus groups regarding how seriously they took NEP-style questions in this study and in prior environmental valuation surveys).

Figure 1.

Causal linkages between threat perceptions and their precursors, and intended and realized behavior in a modified value-belief-norm theoretical framework.

Figure 1.

Causal linkages between threat perceptions and their precursors, and intended and realized behavior in a modified value-belief-norm theoretical framework.

Respondents were asked to rate how important each of 15 value statements was as a guiding principle in their lives. Of the 15 statements, twelve were taken directly from the Schwartz “brief scale” [46], a subset of the original 56-item instrument [47,48]. I modified three environment-specific statements [46] to form culturally oriented survey rating tasks. I first asked respondents to rate each statement on a scale of 1 to 7, whereby 1 represented not at all important and 7 was extremely important. If a respondent rated an item as not at all important, a follow-up question asked if the statement was simply not relevant or whether it was actually in opposition to their values.

The 15 statements used were: (1) protecting and preserving culture and heritage (hereafter referred to as Culture); (2) a creative world, rich in arts and cultural activity (Arts); (3) respecting people of the world, harmony with other cultures (Harmony); (4) a world at peace, free of war and conflict (Peace); (5) social justice, correcting injustice, care for the weak (Justice); (6) equality, equal opportunity for all (Equality); (7) honoring parents and elders, showing respect (Heritage); (8) family security, safety for loved ones (Family security); (9) self-discipline, self-restraint, resistance to temptation (Self-discipline); (10) authority, the right to lead or command (Authority); (11) influence, having an impact on people and events (Influence); (12) wealth, material possessions, money (Wealth); (13) a varied life, filled with challenge, novelty and change (Variety); (14) an exciting life, stimulating experiences (Stimulation); and (15) curious, interested in everything, exploring (Curiosity).

A capital asset approach to quality of life recognizes that individuals, organizations, and society as a whole possess or have access to stocks of cultural capital assets and services (flows) that can enhance quality of life [6,49,50]. Six types of assets—natural, manufactured, human, social, cultural, and financial capital—were used as themes to group indicators. Two potential threats for each of the six main types of capital assets were presented and respondents were asked how much of a threat those factors posed to quality of life in Canada. The 12 threats included: (1) global warming/climate change (Climate); (2) deterioration of water resource quality and/or quantity (groundwater, rivers, lakes, wetlands) (Water); (3) unforeseen consequences of rapid technological change (e.g., genetic engineering, nanotechnology) (Technology); (4) deterioration of Canadian public infrastructure such as roads, bridges, communications, hospitals, schools (Infrastructure); (5) human health problems relating to unhealthy lifestyle choices and/or environmental contaminants (Health); (6) declining standards in education and Canada’s capacity for creativity and innovation (Innovation); (7) declining safety and security at the community, national, and/or international level (Security); (8) stress on, and the breakdown of, Canadian families (Families); (9) loss of traditional ways of life, culture, and heritage (Heritage); (10) a decline in creativity, artistic endeavors, and the cultural industries in Canada (Culture); (11) globalization and its impact on the Canadian economy (Globalization); and (12) high prices, unaffordable housing, and losses in real purchasing power for Canadians (Economy).

Survey respondents were asked to indicate whether they were members of any of the selected seven types of clubs or organizations, including: (1) community service club or organization (e.g., Rotary, Kinsmen, etc.); (2) environmental or natural history organization; (3) outdoor recreation or fitness club (e.g., running, hiking clubs); (4) community performing arts organization; (5) political party (i.e., “card-carrying member”); (6) internationally oriented club or organization (e.g., Amnesty International, Oxfam); and (7) local sports club or team.

Respondents were also asked whether they had participated in any of the listed six types of social or cultural activities over the past 12 months: (1) attended a local church service; (2) attended a concert, play or musical event; (3) visited a local museum or heritage site; (4) purchased a book written by a Canadian author; (5) purchased a piece of art by a Canadian artist; and (6) attended a public talk or lecture at a local college or university.

Standard demographic data collected included age category, income category, gender, marital status, educational attainment, citizenship, primary languages spoken, and residential postal code. Postal codes were used to assign respondent’s place of residence to five regions: Atlantic Canada (Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick); Quebec; Ontario; Prairies (Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, including Northwest Territories); and British Columbia (including Yukon). Information was also collected on the version (English or French) completed, survey completion time (minutes), whether respondents were “protesters” in the accompanying valuation survey [24] (i.e., they would not support hypothetical investments that improved Canadian quality of life for reasons such as their distrust of government), and self-reported awareness of HASS research in Canada.

A HASS awareness indicator was constructed by aggregating scores from four questions regarding respondents’ awareness of the breadth and scope of HASS research in Canada prior to starting this survey. The questions related to: (1) what research is and how it works; (2) the three Canadian research councils that fund research activities nationally; (3) the size of Canadian public and private sector investments in arts, humanities and social sciences research and training; and (4) the diversity of arts, humanities, and social science research in Canadian universities (full wording for the questions is included in supplementary material S1). Responses were coded as 1 (not at all aware); 2 (somewhat aware); and 3 (very aware) and were summed across the four categories, giving a range of scores from 4 (completely unaware of research) to 12 (extremely high level of awareness of HASS research). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.696, indicating that internal consistency among the four items was acceptable.

An international market research firm, GMI, was contracted to supply a sample, drawn from an Internet panel of 140,000+ households generally representative of the Canadian population. The internet survey was designed and implemented with Sawtooth Software’s SSI interviewing software.

2.2. Data Analysis

Latent class (LC) cluster analysis can be used to identify unobserved, or latent, class membership based on observed variables or indicators that imperfectly measure underlying true class membership [51,52]. Functionally, LC clustering reduces dataset complexity by identifying a low number of proxy variables that are predictive of a larger number of dependent indicator variables.

Let X represent the latent variable and Yl one of the L observed indicator variables, where 1 ≤ l ≤ L, C be the number of latent classes, and Dl be the number of levels of Yl. A particular latent class is enumerated by an index x, where x = 1, 2, ..., C, and a particular value of Yl by yl, where yl = 1, 2, ..., Dl. The probability of obtaining any specific response pattern y, P(Y = y), is a weighted average of the C class-specific probabilities P(Y = y | X = x).

where P(X = x) denotes the proportion of respondents belonging to latent class x. Traditional LC analysis can be generalized from its assumption that each observation is a mutually independent member of only one LC when latent variable X is included as an additional dimension in a log-linear model of P(X = x | Y = y) [51,53,54]. Latent Gold software was used to estimate all LC models; Vermunt and Magidson [55] provide technical details on the maximum likelihood estimation methodology. In this study, all latent classes were defined solely on response patterns; sociodemographic covariates were not used for LC classification.

Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC = −2L + [LogN][npar], where N = sample size, L = log-likehood and npar = number parameters) was used to initially identify the model that was most parsimonious [56]. Local independence between indicators was tested in the initial model using the bivariate residual (BVR) Pearson χ2 statistic. Functionally, a significant BVR statistic (i.e., χ2 > 3.84 for 5% significance level) indicated a degree of redundancy between indicators. When there were significant interactions between indicators, I deleted indicators from the LC cluster models until all significant interactions were eliminated. Deleting indicators does not mean that they are unimportant to respondents, only that the information that they provide does not help differentiate clustering patterns. Posterior class membership probabilities from the LC analyses were subsequently used as dependent variables in the demographically based CHAID segmentation.

The Chi-Squared Automatic Interaction Detection (CHAID) segmentation technique is an exploratory tree-based segmentation process that separates a sample into mutually exclusive and exhaustive subgroups [57,58]. Chi-squared goodness of fit tests were used to identify significant predictors of LC membership patterns and merge predictor categories that did not differ in their prediction of the dependent variables. The CHAID procedure aids the development of predictive models by screening out extraneous variables and generating interpretable diagrams of mutually exclusive population segments with similar sociodemographic or survey-specific characteristics [56,58,59]. Predictors with the lowest Bonferroni-adjusted p value defined sub-groupings at each branch of the CHAID dendogram. Throughout the balance of the paper, I refer to first-stage latent class partitions as “classes” and the second-stage CHAID groupings as “segments”. I used SI-CHAID software [60] for all analyses.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Respondent Demographics

A total of 3555 people visited the survey website over an eight-day period in March 2008. In total, 1920 valid completed surveys (n = 266 French respondents; n = 1654 English respondents) were available for the final analysis (54.0% of respondents that visited the survey website). Only surveys in which all fields were completed, including all valuation questions, were used for this analysis.

Province of residence was aggregated into five geographic areas: Atlantic Canada (n = 246), Quebec (n = 331), Ontario (n = 807), Prairie Provinces (n = 292), and British Columbia (“BC”, n = 244). There were significant differences in region of residence between the Canadian population (>15 yrs) and the sample (χ2 = 126.4, 4 d.f., p < 0.0001), with under-representation of Quebec, Prairie Provinces, and BC respondents, and over-representation of Atlantic Canada and Ontario respondents.

Gender (χ2 = 16.9, 1 d.f., p < 0.0001) and age category (χ2 = 337.5, 3 d.f., p < 0.0001) for the sample were also significantly different than those for the population, with younger respondents and females over-represented. As a result, 40 sampling weights (five regions × four age classes × two genders) were used in all subsequent analyses to correct for imbalances in the sample.

Other demographic covariates used in the CHAID analyses included marital status (654 single, 1073 married or common law, 193 divorced, separated, or widowed), language most often spoken at home (1495 primarily English, 290 primarily French, 71 fully bilingual, 64 other languages), educational attainment (425 high school graduation or less, 962 some college or university, 359 bachelor’s degree or equivalent graduate, 174 with graduate-level education), and citizenship (1602 born in Canada, 203 naturalized Canadian citizens, 115 non-Canadian citizens).

The 108 respondents designated as “protestors” in the accompanying valuation analysis [24] were flagged with a dummy variable. Average time to complete the survey was 64.4 min, while median time was 27.5 min. For both the LC and CHAID analyses, survey completion time was grouped into three categories (fast 15.4 min average; medium 27.8 min; and slow 150.2 min) and treated as a nominal variable due to the upward skew in average completion times.

3.2. Cultural Values

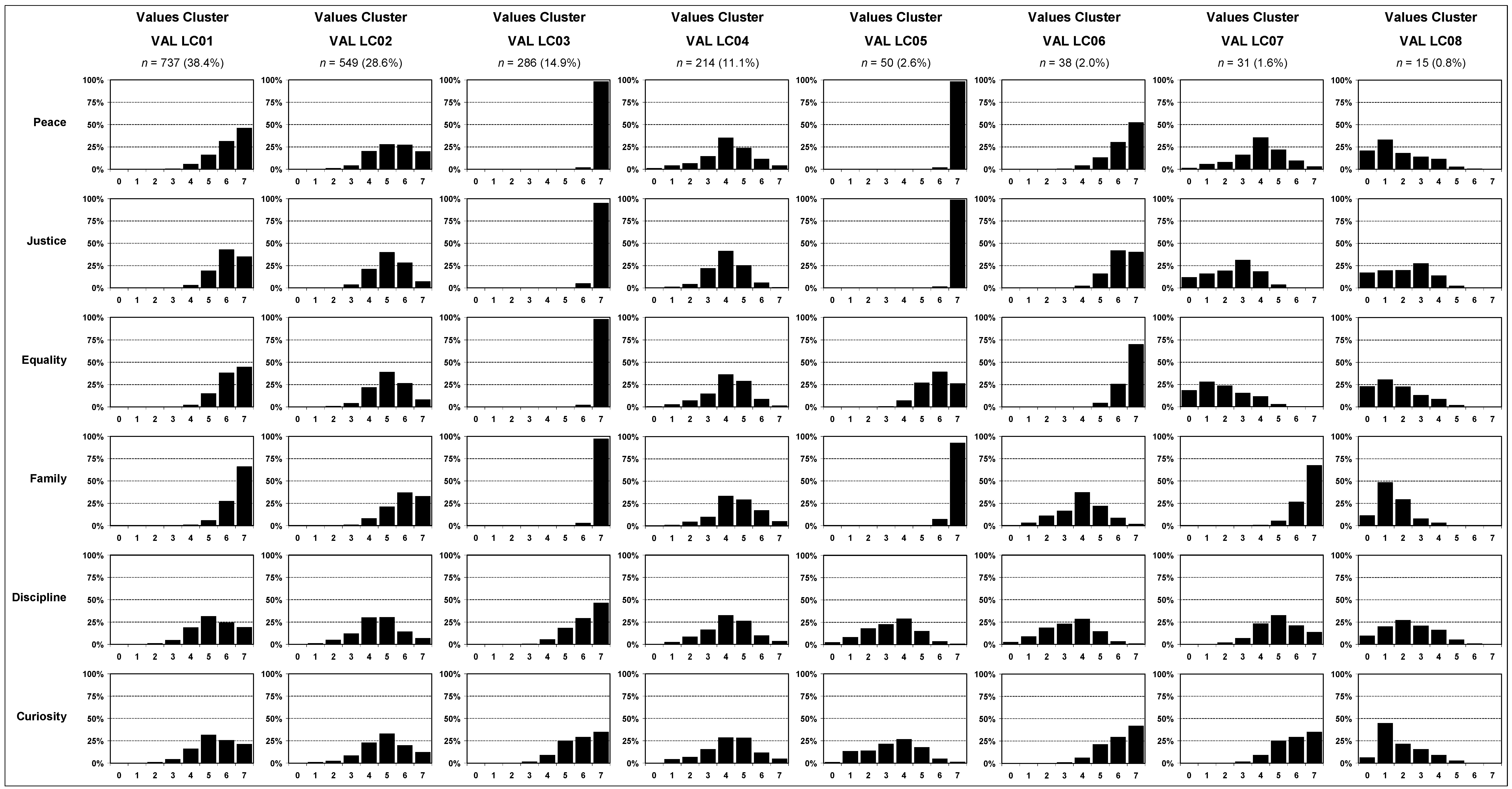

Respondents were presented with a series of 15 statements that they were asked to rate as to their importance as a guiding principle in the respondent’s life (Table 1). Models with two to 13 LCs were estimated. A 12-class LC cluster model minimized BIC and was chosen for further refinement. Numerous BVRs were significant at the 5% level, indicating that there was substantial redundancy amongst the indicators with regards to the information they provided relevant for cluster discrimination. Nine indicators were dropped sequentially (arts, harmony, culture, wealth, stimulation, respect, authority, variety, and influence) to eliminate all significant BVRs. With the reduced indicator set, BIC was minimized using an eight-class model. The final model (n = 1920 respondents, 91 parameters) performed well (LL = −16,281.7, entropy R2 = 0.6747, classification error = 20.3%), cleaving the national sample into eight distinct LCs based on response patterns for six of the 15 Schwartz short scale items. None of the three culturally oriented indicators were retained as explanatory indicators of core values.

Table 1.

Perceived importance of modified Schwartz brief scale value statements.

| Perceived Importance a of Factors as Guiding Principles | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threat | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Family security b | 3 | 12 | 22 | 38 | 145 | 243 | 468 | 989 |

| Peace b | 7 | 19 | 26 | 78 | 259 | 365 | 427 | 739 |

| Equality b | 15 | 20 | 35 | 68 | 239 | 414 | 468 | 661 |

| Respect | 3 | 21 | 33 | 69 | 235 | 373 | 535 | 651 |

| Justice b | 9 | 14 | 24 | 93 | 262 | 448 | 503 | 567 |

| Harmony | 15 | 36 | 65 | 109 | 348 | 491 | 460 | 396 |

| Curiosity b | 2 | 24 | 45 | 128 | 356 | 567 | 428 | 370 |

| Self-discipline b | 6 | 25 | 68 | 177 | 443 | 531 | 370 | 300 |

| Stimulation | 3 | 29 | 43 | 121 | 384 | 567 | 478 | 295 |

| Culture | 9 | 75 | 111 | 211 | 469 | 479 | 322 | 244 |

| Variety | 2 | 36 | 51 | 157 | 438 | 570 | 427 | 239 |

| Arts | 10 | 91 | 143 | 285 | 512 | 469 | 234 | 176 |

| Influence | 9 | 44 | 91 | 214 | 556 | 526 | 316 | 164 |

| Wealth | 22 | 64 | 145 | 260 | 483 | 502 | 283 | 161 |

| Authority | 19 | 85 | 140 | 313 | 564 | 450 | 210 | 139 |

a 0 = opposed to personal guiding principles; 1 = not at all important to 7 = extremely important; b indicator variables retained in latent class cluster analysis.

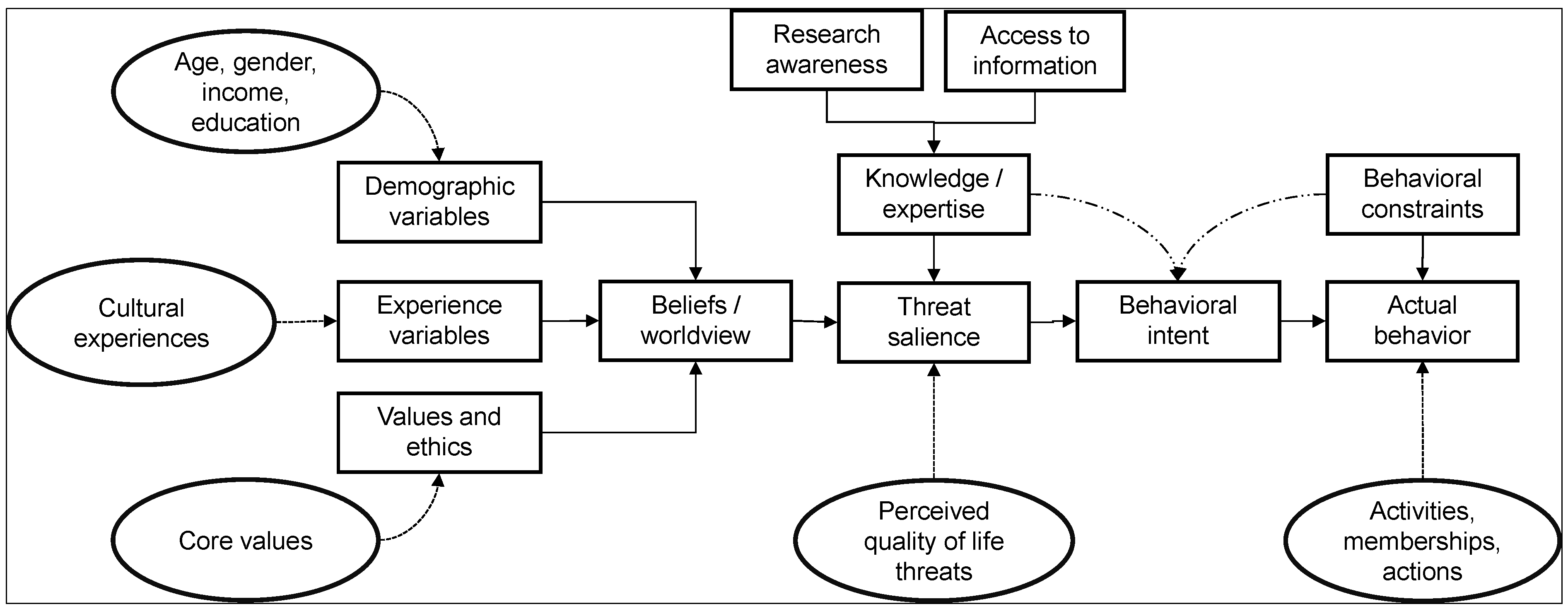

Figure 2 illustrates the differences between the LCs. For example, cluster VAL LC01 (column 1), the single largest class from the sample, was composed of respondents who viewed peace, justice, equality, and family security as important to extremely important. Clusters LC03 and LC05 illustrate the power of LC cluster analysis to differentiate response patterns. Respondents in both clusters almost all viewed peace, justice, and family as extremely important but, unlike respondents in VAL LC03, respondents in VAL LC05 view equality as much less important.

Figure 2.

Value-based cluster summary. X-axis labels: 0 = opposed to item as a personal guiding principle; 1 = not at all important to 7 = extremely important.

Figure 2.

Value-based cluster summary. X-axis labels: 0 = opposed to item as a personal guiding principle; 1 = not at all important to 7 = extremely important.

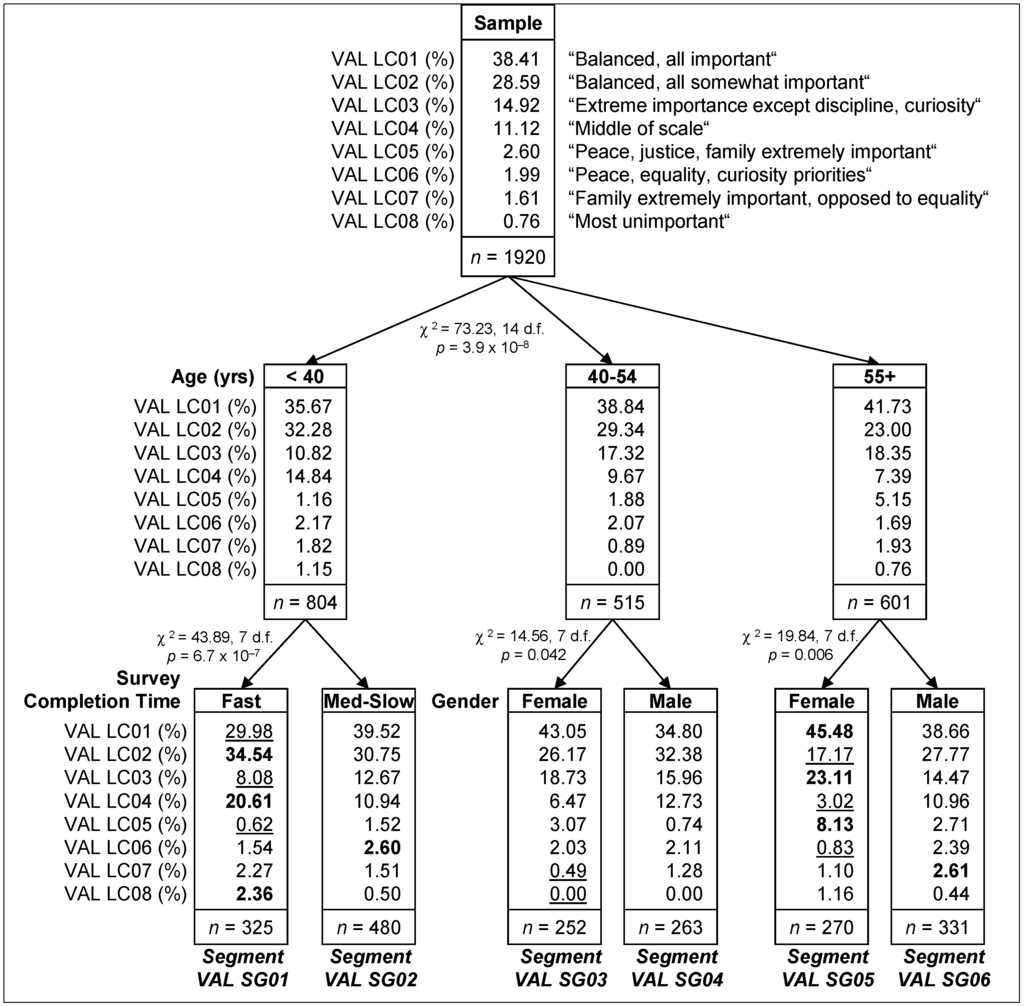

In the subsequent CHAID analysis, age was the most powerful predictor of LC class membership patterns for the eight value-based LCs identified (χ2 = 73.23, 14 d.f., p = 3.9 × 10−8). Three sub-groups, consisting of respondents <40 yrs (weighted n = 804), 40–54 yrs (n = 515), and 55+ yrs (n = 601), showed clear patterns of increasing (VAL LC01, LC03, LC05) and decreasing (VAL LC02, LC04) membership with increasing respondent age (Figure 3). For example, membership in VAL LC02 fell from 32.3% to 23.0% with increasing age. The CHAID dendogram split further along survey completion time for the youngest group and along gender lines for two older groups. Membership was higher in VAL LC01, LC03, and LC05 for older females, and higher in VAL LC02 and LC03 for older males. Older male responders generally seemed to be intermediate in their membership between the <40 yr fast responders and 55+ yr females, the two groups with the most distinctively different value cluster memberships. Note that HASS research awareness was not a significant predictor of any core value membership patterns.

Figure 3.

Value-based CHAID segmentation. Bold indicates the highest single value for latent class membership; underlined indicates the single lowest value for latent class membership.

Figure 3.

Value-based CHAID segmentation. Bold indicates the highest single value for latent class membership; underlined indicates the single lowest value for latent class membership.

Six demographically distinct sample segments (terminal nodes) were identified, each of which can be described according to exogenous predictors and their LC membership patterns (Table 2). The six segments were ranked by index scores that compared membership rate for a single segment to membership rate for the sample as a whole. Index scores were calculated by comparing membership proportions for LC clusters and the overall sample. For example, in CHAID segment 1 (VAL SG01), 34.5% of respondents were from latent class VAL LC02 versus 28.6% for the overall sample (see Figure 3), giving an index score of 121 (=34.5/28.6) and signifying that members of this segment were 21% more likely than average to belong to the “balanced, all somewhat important” latent class. Index scores provide insight into the relative level and diversity of LC membership across CHAID segments and allow rankings of LC membership across CHAID segments.

Table 2.

Summary of segmentation of value-based latent class clusters.

| VAL SEG 01 | VAL SEG 02 | VAL SEG 03 | VAL SEG 04 | VAL SEG 05 | VAL SEG 06 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segment size (n) | 325 | 480 | 252 | 263 | 270 | 331 |

| Proportion of sample (%) | 16.9 | 25.0 | 13.1 | 13.7 | 14.0 | 17.2 |

| Segment characteristics | ||||||

| Age (yrs) | <40 | <40 | 40–54 | 40–54 | 55+ | 55+ |

| Gender | - | - | Female | Male | Female | Male |

| Survey completion time a | 1 | 2–3 | - | - | - | - |

| Latent class membership (%) | ||||||

| Balanced, all important | 29.98 | 39.52 | 43.05 | 34.80 | 45.48 | 38.66 |

| Index | 78 | 103 | 112 | 91 | 118 | 101 |

| Rank | 6 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Balanced, all somewhat important | 34.54 | 30.75 | 26.17 | 32.38 | 17.17 | 27.77 |

| Index | 121 | 108 | 92 | 113 | 60 | 97 |

| Rank | 1 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| Extremely important except discipline, curiosity | 8.08 | 12.67 | 18.73 | 15.96 | 23.11 | 14.47 |

| Index | 54 | 85 | 126 | 107 | 155 | 97 |

| Rank | 6 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Middle of scale | 20.61 | 10.94 | 6.47 | 12.73 | 3.02 | 10.96 |

| Index | 185 | 98 | 58 | 114 | 27 | 99 |

| Rank | 1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3 |

| Peace, justice, family extremely important | 0.62 | 1.52 | 3.07 | 0.74 | 8.13 | 2.71 |

| Index | 24 | 58 | 118 | 29 | 313 | 104 |

| Rank | 6 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3 |

| Peace, equality, curiosity important | 1.54 | 2.60 | 2.03 | 2.11 | 0.83 | 2.39 |

| Index | 77 | 130 | 102 | 106 | 42 | 120 |

| Rank | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 2 |

| Family extremely important, opposed to equality | 2.27 | 1.51 | 0.49 | 1.28 | 1.10 | 2.61 |

| Index | 141 | 94 | 30 | 79 | 69 | 163 |

| Rank | 2 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

| Most unimportant | 2.36 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.16 | 0.44 |

| Index | 309 | 65 | 0 | 1 | 152 | 57 |

| Rank | 1 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

a Time: 1 = fast < 21.2 min (mean = 15.4); 2 = medium 21.2 to 35.9 min (mean = 27.8); 3 = slow 36+ min (mean = 150.2); bold indicates the highest single value for latent class membership; underlined indicates the lowest value for latent class membership).

Each segment was described in terms of the demographic profile of its members and their LC membership patterns. Segment 1, for example, which was comprised of younger respondents who completed the survey quickly, had the highest index scores for latent class VAL LC02 (“balanced, all somewhat important”), VAL LC04 (“middle of scale”), and VAL LC08 (“most unimportant”) memberships (the highest index scores are bolded in all CHAID diagrams). On the other hand, this group also had the lowest index scores for latent classes VAL LC01 (“balanced, all important”), VAL LC03 (“extreme importance except discipline, curiosity”), and LC05 (“peace, justice, family extremely important”) memberships.

3.3. Threat Perceptions

Respondents were presented with 12 potential threats to Canadian quality of life and were asked to rate their importance (Table 3). Threats to the economy and environment were viewed as the most important by respondents, while threats to heritage and culture, in addition to threats due to technological advances, were perceived as having relatively low importance.

Table 3.

Perceived importance of potential threats to Canadian quality of life.

| Perceived Importance of Potential Threats to Quality of Life in Canada | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threat | Very Low | Low | Moderate | High | Very High | No Opinion |

| Water | 49 | 136 | 350 | 547 | 804 | 34 |

| Economy a | 45 | 125 | 384 | 552 | 790 | 24 |

| Climate a | 148 | 202 | 383 | 418 | 733 | 36 |

| Health a | 60 | 159 | 480 | 591 | 609 | 21 |

| Infrastructure a | 60 | 187 | 467 | 638 | 537 | 31 |

| Families a | 112 | 235 | 521 | 516 | 502 | 34 |

| Innovation a | 100 | 259 | 570 | 519 | 429 | 43 |

| Security a | 126 | 344 | 636 | 465 | 301 | 48 |

| Globalization a | 167 | 306 | 661 | 446 | 259 | 81 |

| Heritage a | 304 | 436 | 528 | 354 | 251 | 47 |

| Technology a | 303 | 469 | 588 | 320 | 149 | 91 |

| Culture a | 420 | 543 | 566 | 232 | 86 | 73 |

a Indicator variables retained in latent class cluster analysis to define classes.

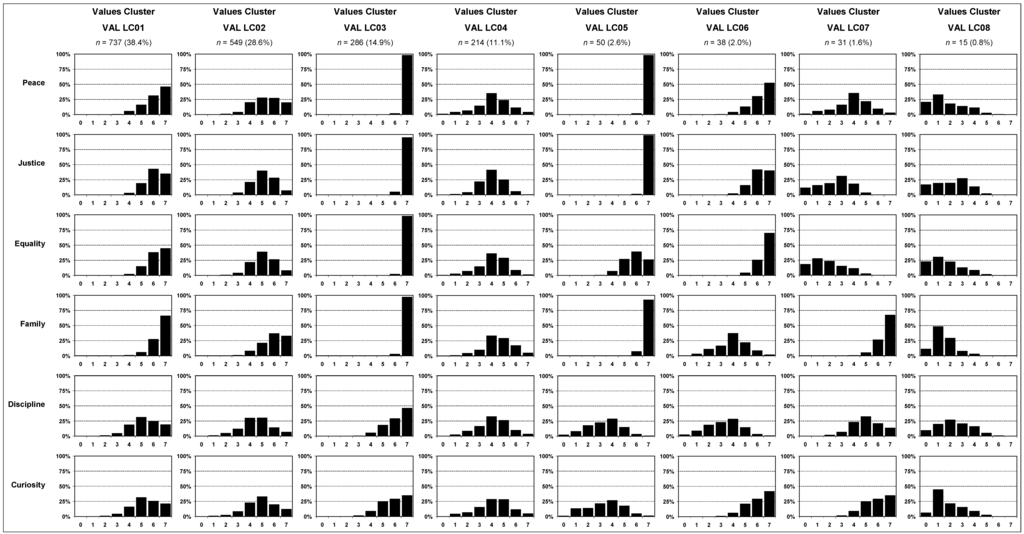

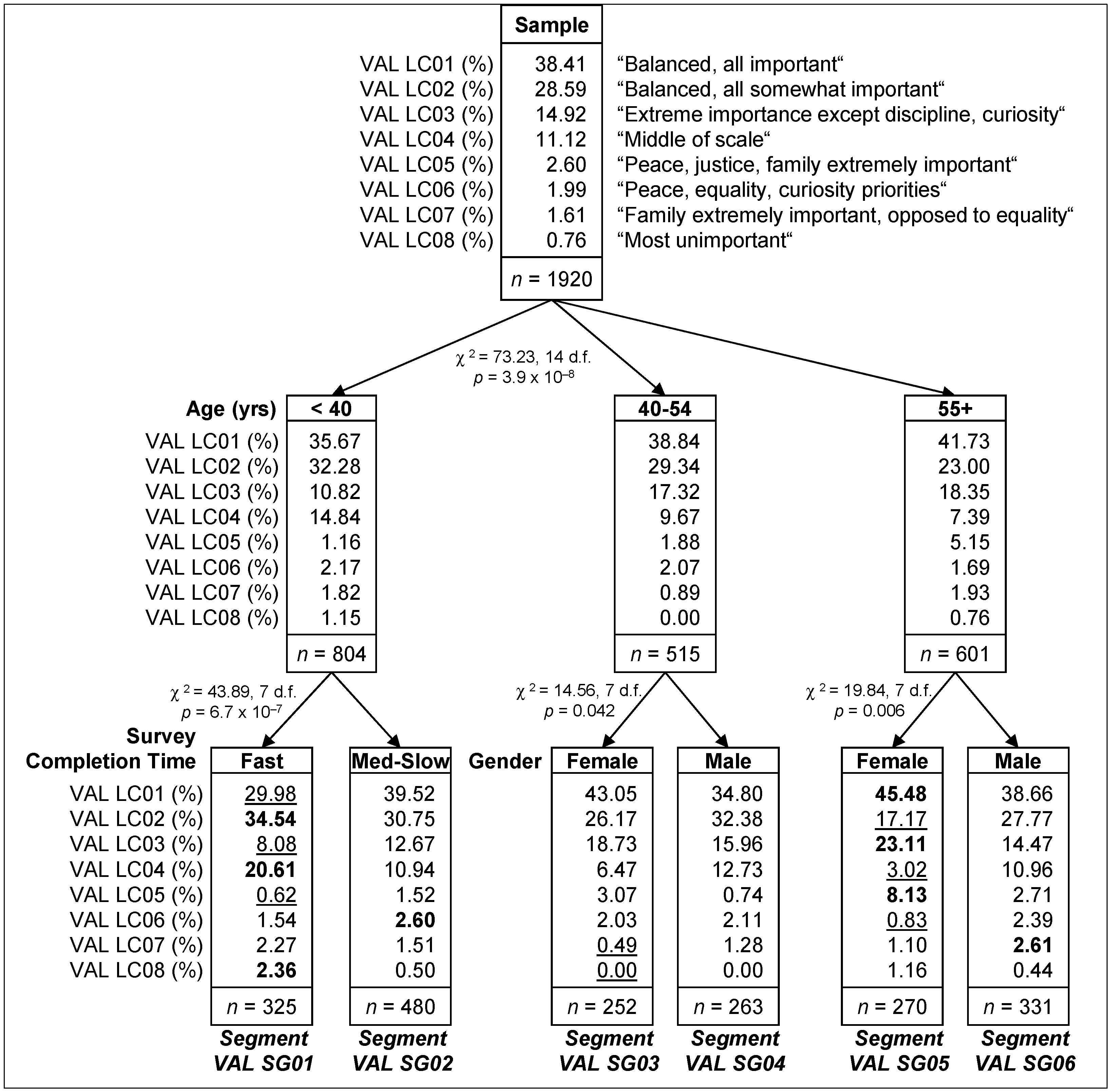

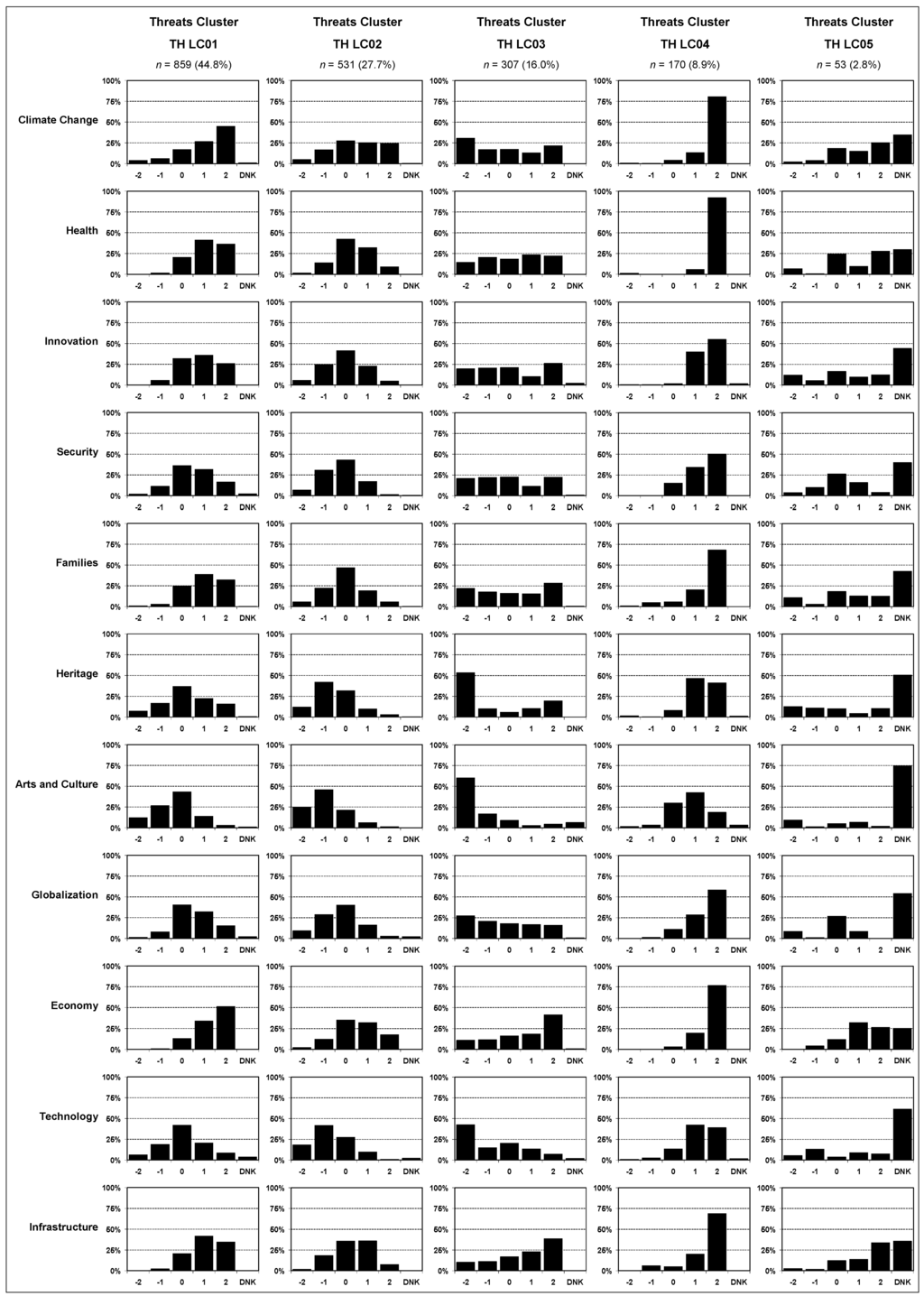

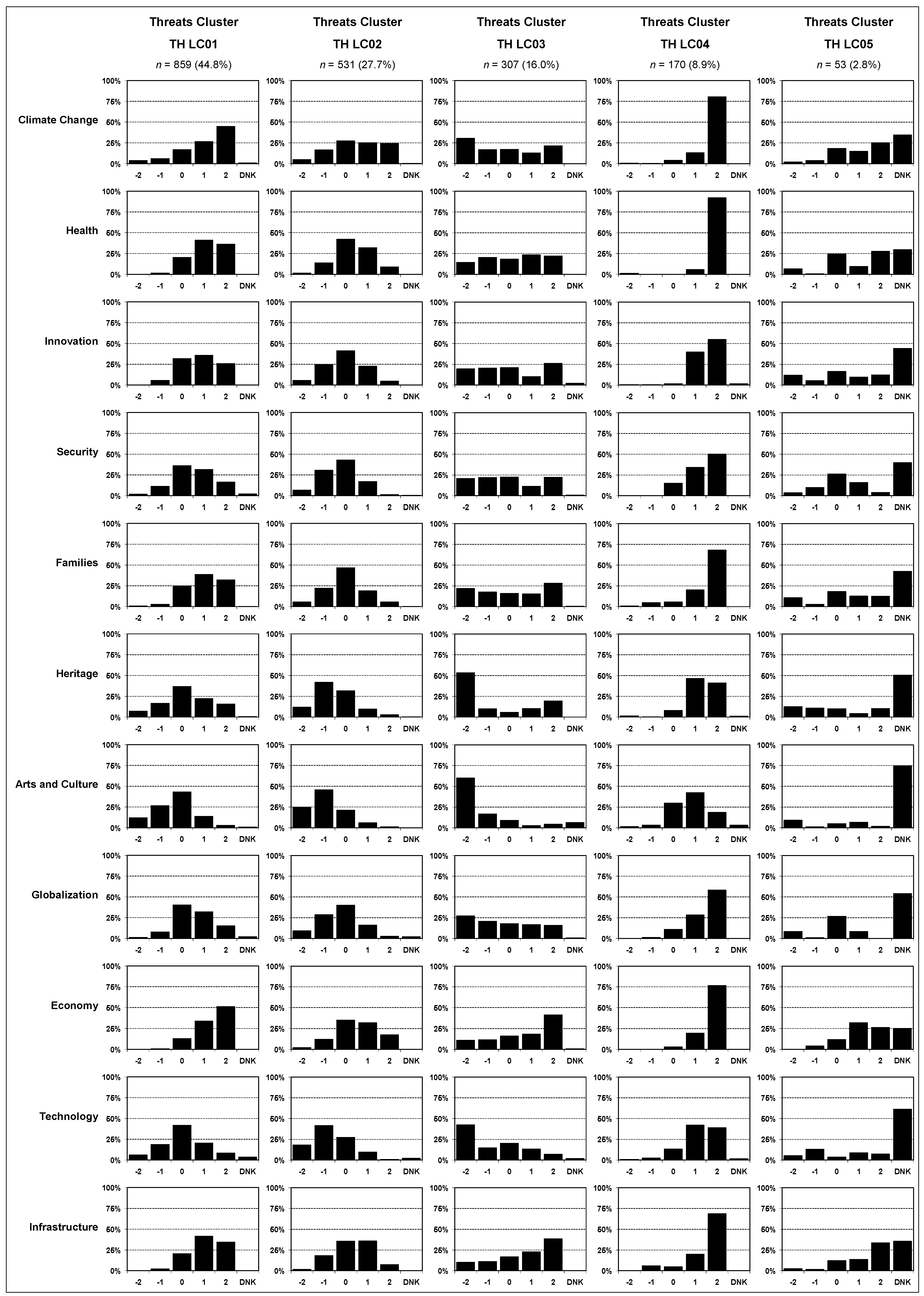

A 5-class LC cluster model initially minimized BIC and was chosen for further refinement. Only one BVR was significant, indicating that there was low overlap in clustering-relevant information that indicators provided. Water was dropped from the model to eliminate all significant BVRs. With the reduced indicator set, BIC was minimized using a five-class final model that performed very well (n = 1920 respondents, 91 parameters; LL = −29,986.1, entropy R2 = 0.7720, classification error = 11.8%). Figure 4 illustrates the indicator breakdowns.

Figure 4.

Threat-based cluster summary. X-axis scale: −2 = not at all important, to +2 = very important; DNK = do not know.

Figure 4.

Threat-based cluster summary. X-axis scale: −2 = not at all important, to +2 = very important; DNK = do not know.

For latent class TH LC01 (column 1), which comprised 44.8% of the sample, respondents viewed climate change and threats to the economy as the most important, and threats to the arts and cultural sector as least important. Cluster TH LC02 showed a very similar pattern of threat perception but their responses were more skewed to the left of the scale, indicating they viewed all threats as somewhat less important than TH LC01 respondents. Respondents in latent class TH LC03 exhibited a much different pattern, with relatively high emphasis on the economy and infrastructure, and a low emphasis on threats to arts and heritage, climate, and innovation. Respondents in cluster TH LC04 tended to view all threats as very important (although with slightly less emphasis on arts and culture, heritage, and technology) and respondents in cluster TH LC05 exhibited a high degree of uncertainty.

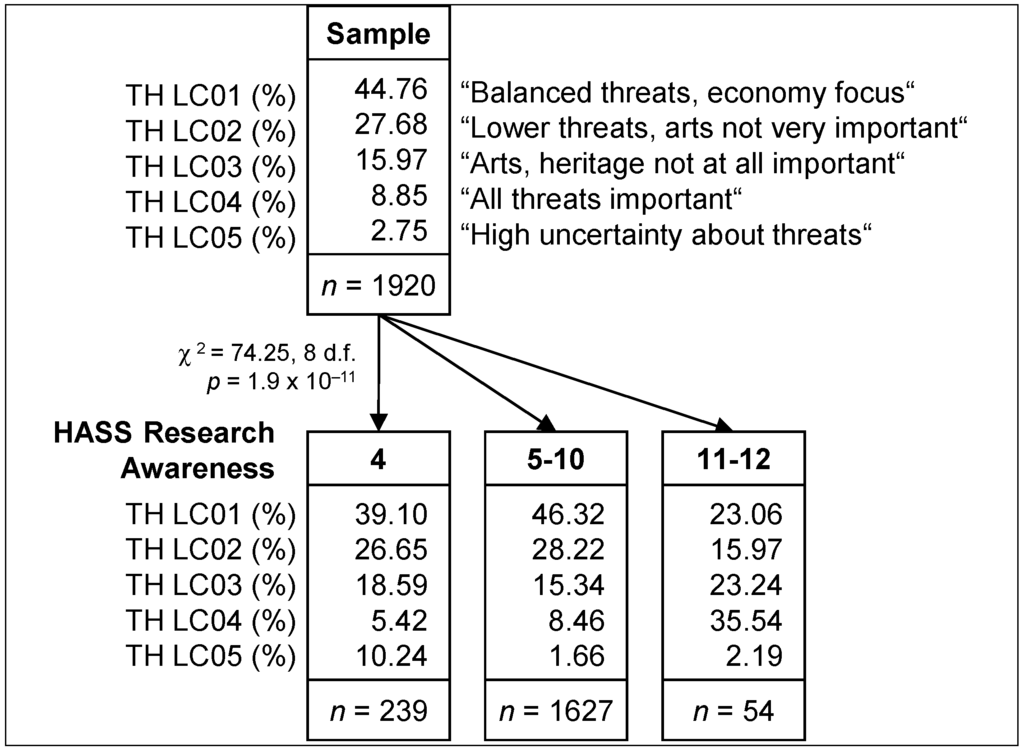

HASS research awareness was the most powerful predictor of LC class membership (χ2 = 74.25, 8 d.f., p = 1.9 × 10−11), with a clear breakdown of the sample into three groups (for brevity, Figure 5 shows only the first level of the CHAID tree) comprised of respondents with: no awareness of research or the HASS research process (score = 4); low to intermediate (score = 5–10) awareness; and high (score = 11–12) awareness. There is a particularly strong trend for cluster TH LC04 (“all threats important”) to increase with increasing HASS research awareness.

Figure 5.

Threat-based sample segmentation (first level of the CHAID dendogram only). HASS research awareness: 4 = no awareness to 12 = highest awareness.

Figure 5.

Threat-based sample segmentation (first level of the CHAID dendogram only). HASS research awareness: 4 = no awareness to 12 = highest awareness.

After the first-level, there were complex splits based on varying demographic and survey-specific indicators. Thirteen distinct CHAID segments were identified for the national sample (Table 4). For respondents with the lowest level of research awareness, educational attainment and—for respondents with more than secondary education—region of residence, were significant predictors of segmentation. Respondents with low HASS research awareness and low education attainment had the highest level of uncertainty about threats to quality of life. In segments TH SG02 and TH SG03, there were strong differences in LC membership by region with the “arts, heritage not at all important” being more prevalent in Ontario and western Canada relative to Quebec and Atlantic Canada.

The choice experiment “protest” dummy was significant for TH SG07. Over half of the members of this segment (intermediate HASS research awareness, fast completion time, male, some college education or above, protesters) belonged to TH LC03, the “arts, heritage not at all important” class.

Table 4.

Summary of segmentation of threat-based latent class clusters.

| CHAID Perceived Threats Segment | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TH SG01 | TH SG02 | TH SG03 | TH SG04 | TH SG05 | TH SG06 | TH SG07 | TH SG08 | TH SG09 | TH SG10 | TH SG11 | TH SG12 | TH SG13 | |

| Segment Size (n) | 90 | 72 | 77 | 215 | 40 | 185 | 23 | 158 | 400 | 493 | 114 | 18 | 36 |

| Proportion of sample (%) | 4.7 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 11.2 | 2.1 | 9.6 | 1.2 | 8.0 | 20.8 | 25.7 | 5.9 | 0.9 | 1.9 |

| Segment characteristics | |||||||||||||

| HASS research awareness a | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5–10 | 5–10 | 5–10 | 5–10 | 5–10 | 5–10 | 5–10 | 5–10 | 11–12 | 11–12 |

| Educational attainment b | 1 | 2–4 | 2–4 | - | 1 | 2–4 | 2–4 | 1 | 2–4 | - | - | - | - |

| Survey completion time c | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2–3 | 2–3 | 2–3 | 2–3 | 1 | 2–3 |

| Region d | - | 1–2 | 3–5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Gender | - | - | - | F | M | M | M | F | F | M | M | - | - |

| Citizenship e | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | - | - |

| Protest f | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Latent class membership (%) | |||||||||||||

| Balanced threats, economy focus | 47.2 | 42.0 | 26.8 | 45.6 | 35.2 | 35.2 | 28.4 | 52.3 | 58.8 | 45.7 | 36.5 | 31.6 | 18.8 |

| Index | 106 | 94 | 60 | 102 | 79 | 79 | 63 | 117 | 131 | 102 | 81 | 71 | 42 |

| Rank | 3 | 6 | 12 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 13 |

| Lower threats, arts not important | 18.6 | 34.8 | 28.6 | 31.8 | 14.8 | 39.9 | 20.5 | 19.6 | 26.2 | 31.0 | 28.8 | 21.7 | 13.1 |

| Index | 67 | 126 | 103 | 115 | 53 | 144 | 74 | 71 | 95 | 112 | 104 | 78 | 47 |

| Rank | 11 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Arts, heritage not at all important | 12.1 | 8.1 | 36.0 | 14.2 | 35.5 | 19.9 | 51.1 | 10.7 | 7.4 | 16.9 | 17.1 | 30.2 | 19.8 |

| Index | 76 | 51 | 225 | 89 | 222 | 124 | 320 | 67 | 47 | 106 | 107 | 189 | 124 |

| Rank | 10 | 12 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 11 | 13 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 6 |

| All threats important | 2.3 | 12.6 | 2.4 | 5.0 | 12.1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 14.5 | 7.5 | 6.3 | 15.6 | 10.1 | 48.2 |

| Index | 26 | 142 | 27 | 57 | 137 | 29 | 0 | 164 | 857 | 71 | 177 | 114 | 544 |

| Rank | 12 | 4 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 13 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 1 |

| High uncertainty about threats | 19.8 | 2.5 | 6.2 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 0.1 |

| Index | 720 | 92 | 227 | 121 | 87 | 91 | 2 | 105 | 2 | 8 | 71 | 233 | 4 |

| Rank | 1 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 12 | 5 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 2 | 11 |

a 4 = no HASS research awareness to 12 = highest awareness; b Education: 1 = secondary or less, 2 = some college or university, 3 = bachelor’s, 4 = graduate education; c Time: 1 = < 21.2 min, 2 = 21.2 to 35.9 min, 3 = 36+ min; d Region: 1 = Atlantic Canada, 2 = Quebec, 3 = Ontario, 4 = Prairie Provinces, 5 = BC; e Citizenship: 1 = Canadian-born, 2 = non-naturalized residents/non-Canadians; f 1 = non-protestor, 2 = protest voter in valuation survey. Bold = 2 highest membership values; underlined = 2 lowest membership values.

3.4. Memberships

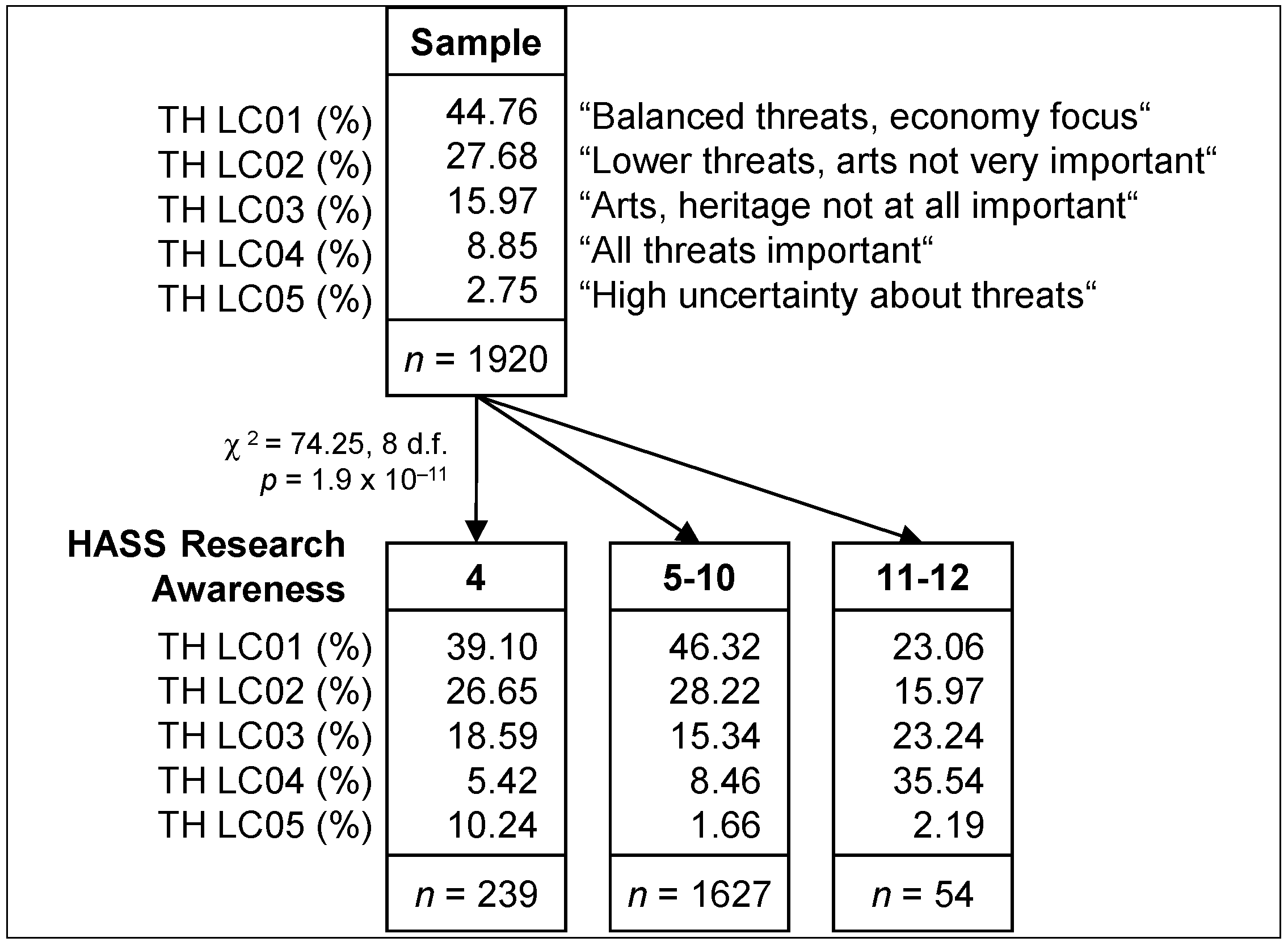

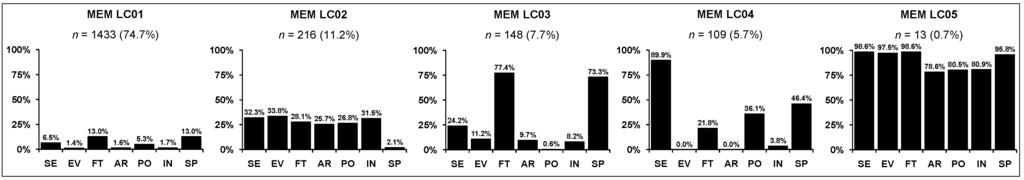

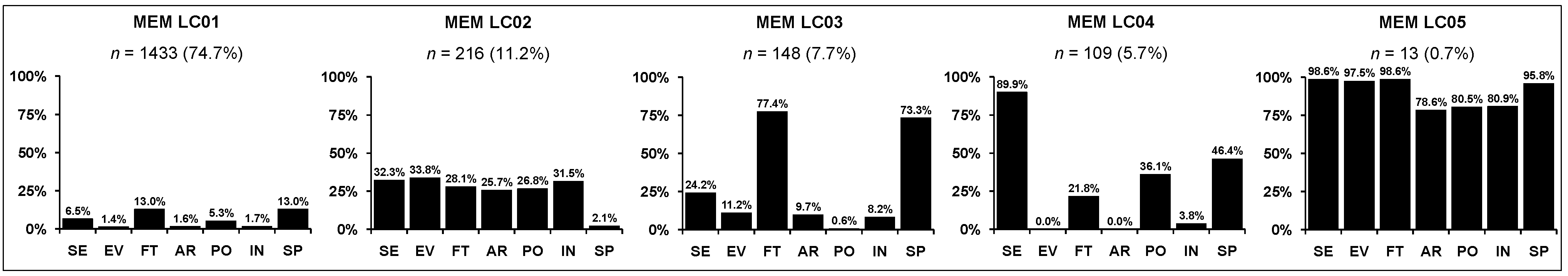

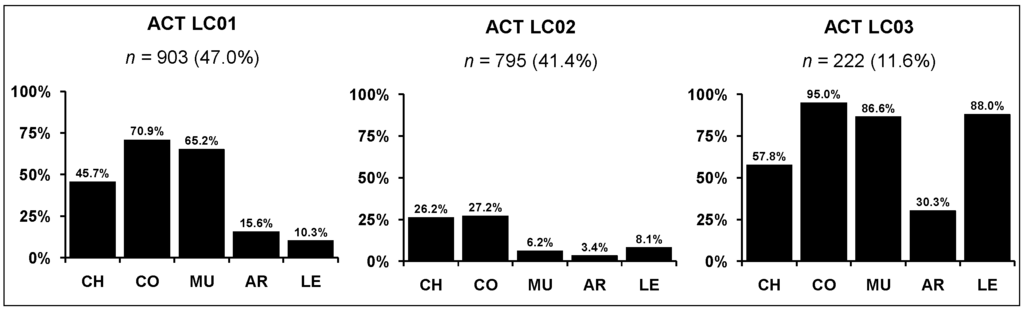

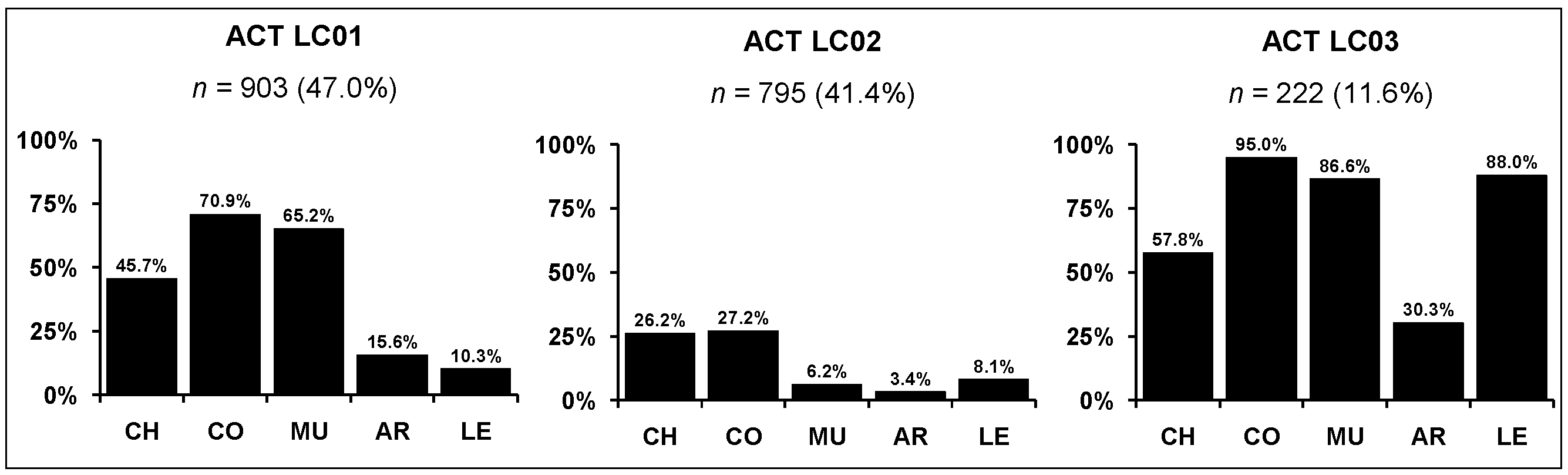

Binary yes-no responses regarding participation in seven various types of clubs or organizations were used for the memberships-based LC cluster analysis. The most popular organizations were recreation/fitness (n = 408, 21.3%) and sports (n = 403, 21.0%), followed by community service (n = 278, 14.5%), political (n = 138, 7.2%), internationally oriented (n = 130, 6.8%), environmental (n = 128, 6.7%), and community arts organizations (n = 109, 5.7%). A four-class LC cluster model minimized BIC but had one significant BVR due to a service-politics interaction. Rather than drop one of these indicators, the five-class model, which had no significant BVRs and only marginally higher BIC, was chosen as the final model (n = 1920 respondents, 39 parameters; LL = −4429.4, entropy R2 = 0.5194 classification error = 14.4%). Figure 6 shows the indicator breakdowns, which are simpler due to the binary membership indicators.

Figure 6.

Membership-based cluster summary. X-axis labels: SE = community service clubs; EV = environmental; FT = fitness and outdoor recreation; AR = community arts; PO = political; IN = internationally-oriented; SP = sports.

Figure 6.

Membership-based cluster summary. X-axis labels: SE = community service clubs; EV = environmental; FT = fitness and outdoor recreation; AR = community arts; PO = political; IN = internationally-oriented; SP = sports.

There were very clear differences between the classes, with 75% of the sample belonging to the “inactive” latent class MEM LC01. MEM LC02 members were moderately active in all organizations except for sports teams. MEM LC03 members were fitness and sport focused, while members of MEM LC04 were most involved with community service clubs. Members of the small MEM LC04 (n = 13) latent class were active in all organizations.

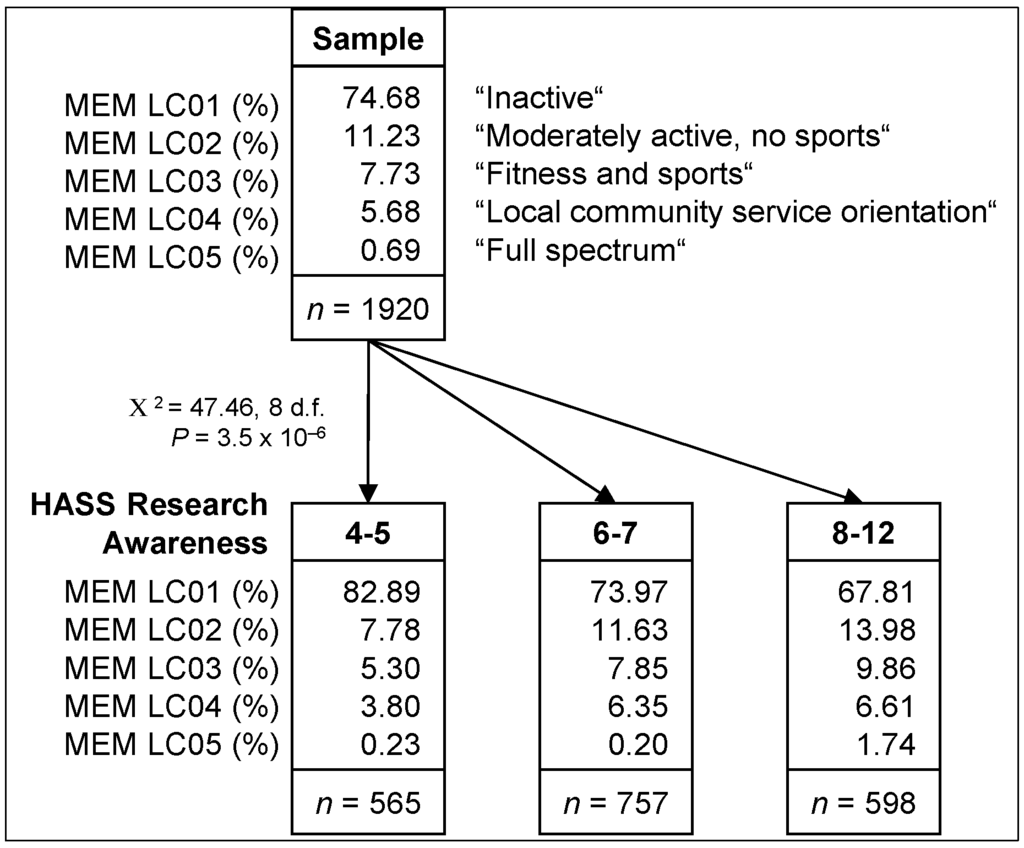

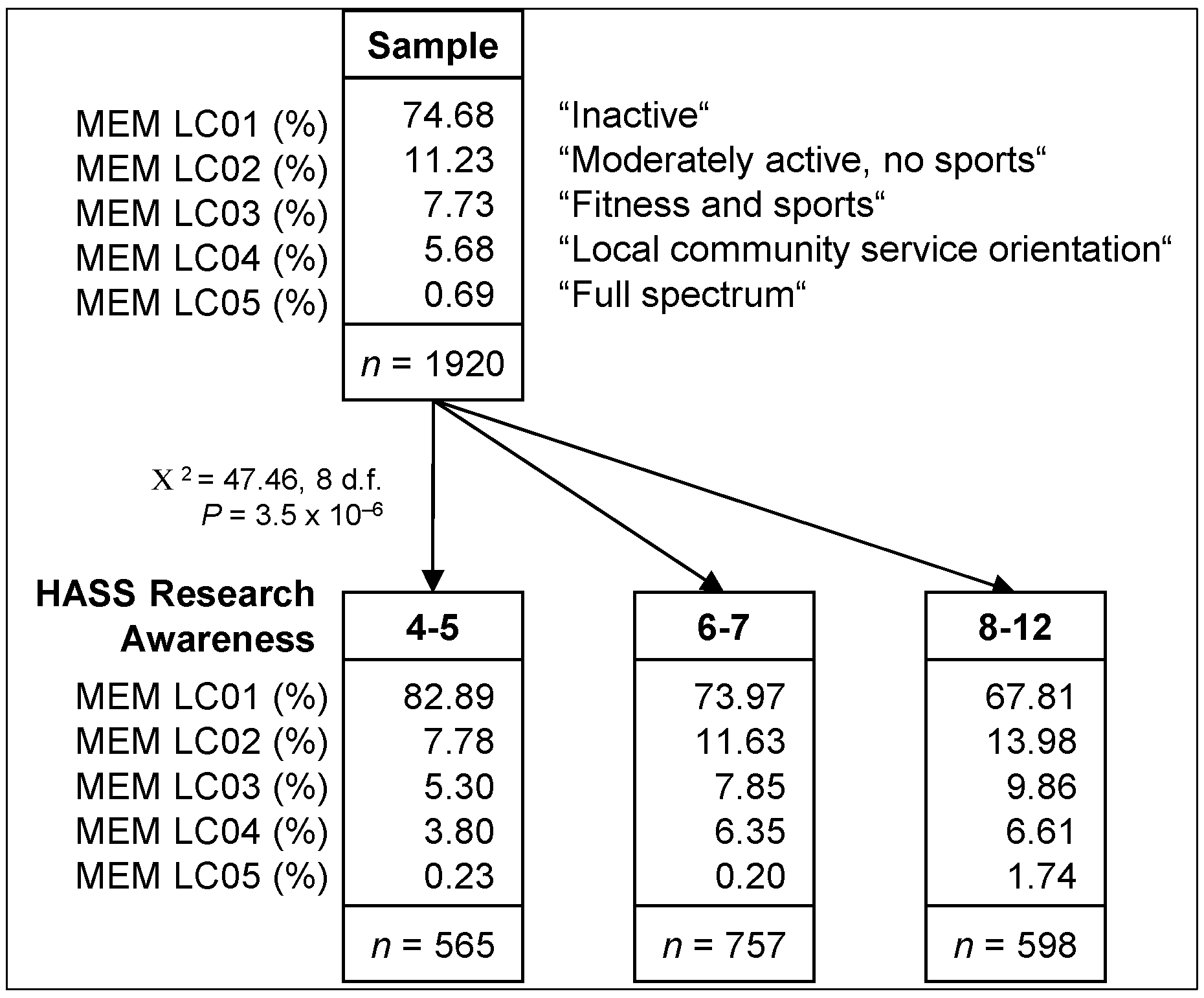

The first level of the CHAID dendogram for the membership analysis is shown in Figure 7 (the full chart is available from the author upon request). Again, HASS research awareness was the most powerful predictor of LC class membership (χ2 = 47.46, 8 d.f., p = 3.5 × 10−6). The survey respondents showed a sharp trend of declining inactivity with increasing HASS research awareness.

The low-medium awareness group (score = 6–7) split further on marital status, with higher MEM LC02 membership amongst single and married respondents. The group with medium to high HASS awareness (score = 8–12) could be further cleaved according to educational attainment and, for those with the highest levels of educational attainment, by citizenship at the 5% significance level. Six distinct CHAID segments were identified (Table 5). Respondents with the lowest levels of HASS research awareness (score = 4–5) were largely (82.9%) members of latent class MEM LC01, the inactive class. They also had the lowest proportion of MEM LC02 (moderately active, no sports) and MEM LC03 membership (fitness and sports) classes. At the other end of the spectrum, respondents who had a high level of HASS research awareness and educational attainment, and were not born in Canada had the highest level of membership in MEM LC03 and LC05 (full spectrum).

Figure 7.

Membership-based sample segmentation (first level of the CHAID dendogram only; HASS research awareness: 4 = no awareness to 12 = highest awareness).

Figure 7.

Membership-based sample segmentation (first level of the CHAID dendogram only; HASS research awareness: 4 = no awareness to 12 = highest awareness).

Table 5.

Summary of segmentation of membership-based latent class clusters.

| CHAID Membership Segment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEM SG01 | MEM SG02 | MEM SG03 | MEM SG04 | MEM SG05 | MEM SG06 | |

| Segment Size | ||||||

| n | 565 | 316 | 441 | 384 | 163 | 51 |

| % of total sample | 29.43 | 16.46 | 22.97 | 20.00 | 8.49 | 2.66 |

| Segment characteristics | ||||||

| HASS research awareness a | 4–5 | 6–7 | 6–7 | 8–12 | 8–12 | 8–12 |

| Marital status b | - | 1,3 | 2 | - | - | - |

| Educational attainment c | - | - | - | 1–2 | 3–4 | 3–4 |

| Citizenship status d | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 |

| Latent class membership (%) | ||||||

| Inactive | 82.89 | 73.37 | 74.40 | 70.53 | 63.05 | 62.50 |

| Index | 111 | 98 | 100 | 94 | 84 | 84 |

| Rank | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Moderately active, no sports | 7.78 | 15.67 | 8.73 | 14.28 | 13.51 | 13.29 |

| Index | 69 | 140 | 78 | 127 | 120 | 118 |

| Rank | 6 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Fitness and sports | 5.30 | 6.73 | 8.66 | 8.58 | 11.83 | 13.26 |

| Index | 69 | 87 | 112 | 111 | 153 | 172 |

| Rank | 6 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Local community service orientation | 3.80 | 3.89 | 8.12 | 6.01 | 9.47 | 2.00 |

| Index | 67 | 69 | 143 | 106 | 167 | 35 |

| Rank | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Full spectrum | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.61 | 2.14 | 8.95 |

| Index | 34 | 30 | 13 | 89 | 311 | 1300 |

| Rank | 5 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

a HASS research awareness: 4 = no awareness to 12 = highest awareness; b Marital status: 1 = single; 2 = married or equivalent; 3 = divorced, separated, or widowed; c Educational attainment: 1 = secondary or less, 2 = some college or university, 3 = Bachelor level graduate, 4 = graduate education; d Citizenship: 1 = Canadian born citizens, 2 = non-naturalized residents and non-Canadians; bold indicates the highest single value for latent class membership; underlined indicates the single lowest value for latent class membership.

3.5. Cultural Activities

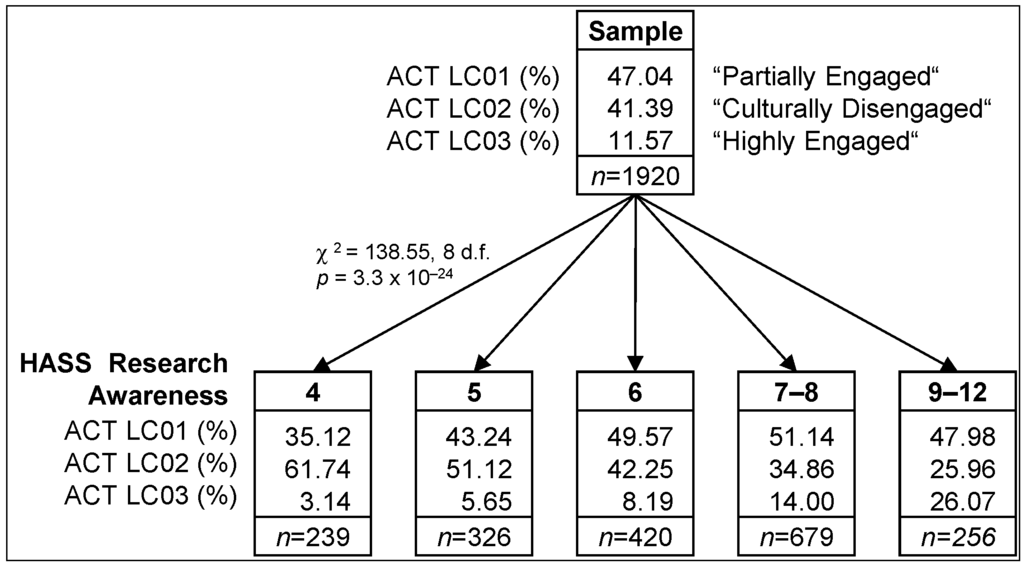

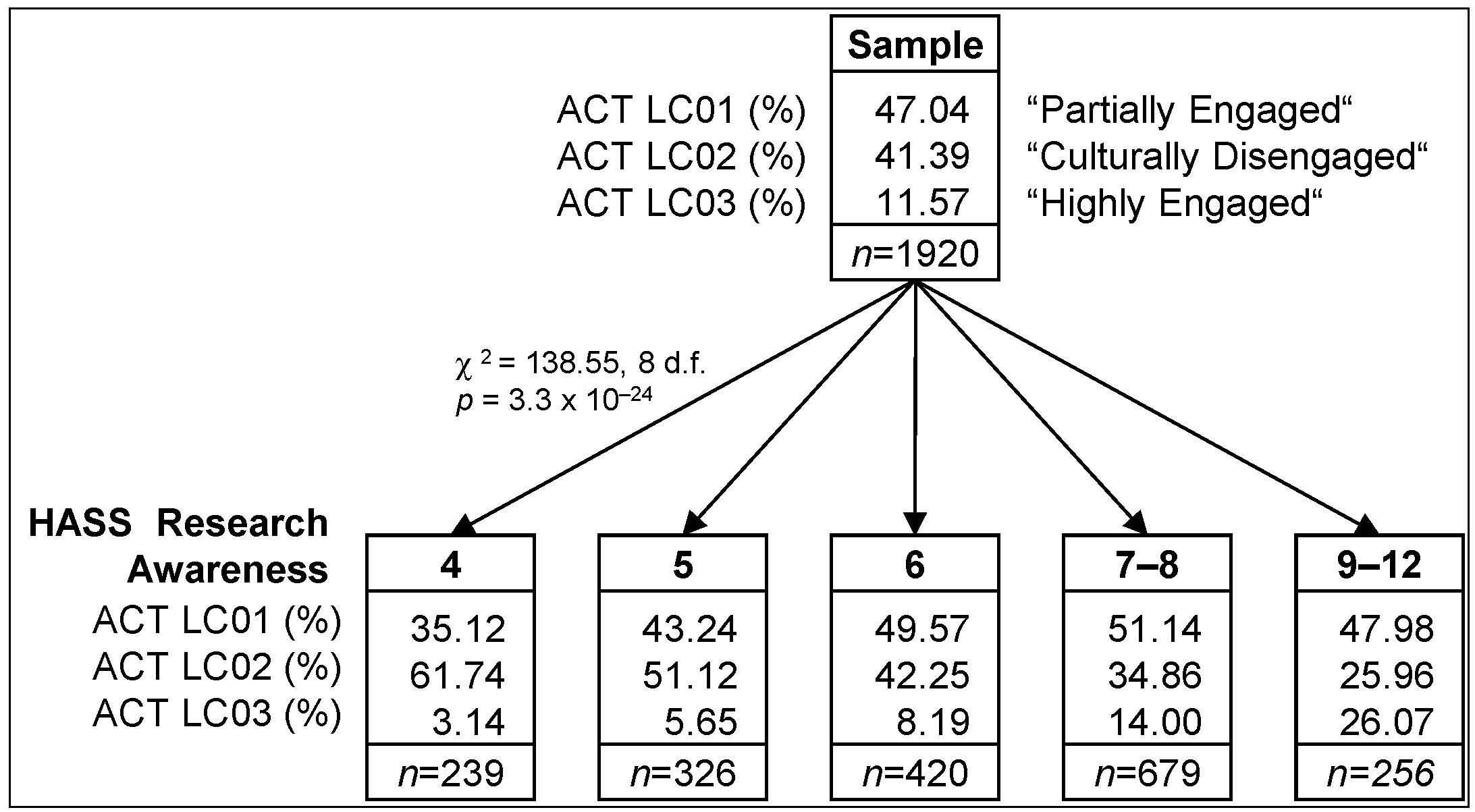

Binary yes-no responses regarding participation in six various types of social or cultural activities were used for the cultural activities LC cluster analysis. In the last 12 months, 1052 respondents (54.8%) had attended a concert or musical event, 850 (44.3%) had visited a museum or heritage site, 815 (42.4%) had purchased a book by a Canadian author, 720 (37.5%) had attended a local church service, 397 (20.7%) had attended a public lecture, and 248 (12.9%) had purchased a piece of Canadian art. After deleting Canadian book purchases (two significant BVRs), a three-class LC cluster model minimized BIC and was chosen as the final model (n = 1920 respondents, 17 parameters; LL = −5303.6, entropy R2 = 0.4916 classification error = 20.8%). The LC membership breakdown is shown in Figure 8. The first level of the CHAID dendogram for the activities analysis is shown in Figure 9 (the full chart is available from the author upon request). HASS research awareness was a very powerful predictor of LC class membership (χ2 = 138.55, 8 d.f., p = 3.3 × 10−24), with increasing trends in cultural participation as HASS research awareness increased.

Figure 8.

Activities-based cluster summary. X-axis labels: CH = attended church service; CO = attended concert; MU = museum or heritage site visit; AR = purchased Canadian art; LE = attended public lecture.

Figure 8.

Activities-based cluster summary. X-axis labels: CH = attended church service; CO = attended concert; MU = museum or heritage site visit; AR = purchased Canadian art; LE = attended public lecture.

Figure 9.

Activities-based segmentation (first level of the CHAID dendogram only). HASS research awareness: 4 = no awareness to 12 = highest awareness.

Figure 9.

Activities-based segmentation (first level of the CHAID dendogram only). HASS research awareness: 4 = no awareness to 12 = highest awareness.

The segments with the two lowest levels of research awareness could not be further split but all other groups with higher HASS awareness could be further divided based on educational attainment, with a general trend of increasing activity as educational level increased. Eleven demographically distinct sample segments were identified (Table 6). The lowest rates of participation (i.e., highest ACT LC02 membership at 61.7%) in cultural activities occurred in segment ACT SG01, the group with the lowest level of HASS awareness. Membership in the inactive LC02 class fell to 21.6% in ACT SG10, where respondents had the highest level of HASS research awareness, slow survey completion times, but lower levels of educational attainment (some college or university or less) than for ACT SG11.

Table 6.

Summary of CHAID segmentation of activity-based latent class clusters.

| CHAID Cultural Activities Segment | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT SG01 | ACT SG02 | ACT SG03 | ACT SG04 | ACT SG05 | ACT SG06 | ACT SG07 | ACT SG08 | ACT SG09 | ACT SG10 | ACT SG11 | |

| Segment Size (n) | 239 | 326 | 171 | 165 | 84 | 146 | 337 | 197 | 85 | 61 | 110 |

| Proportion of sample (%) | 12.4 | 17.0 | 8.9 | 8.6 | 4.4 | 7.6 | 17.5 | 10.3 | 4.4 | 3.2 | 5.7 |

| Segment characteristics | |||||||||||

| HASS research awareness a | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7–8 | 7–8 | 7–8 | 9–12 | 9–12 | 9–12 |

| Educational attainment b | - | - | 1–2 | 1–2 | 3–4 | 1 | 2 | 3–4 | 1–2 | 1–2 | 3–4 |

| Gender | - | - | F | M | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Survey completion time c | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1–2 | 3 | - |

| Latent class membership (%) | |||||||||||

| Partially engaged | 35.1 | 43.2 | 47.9 | 48.8 | 54.5 | 43.9 | 55.0 | 50.5 | 49.2 | 51.5 | 45.1 |

| Index | 75 | 92 | 102 | 104 | 116 | 93 | 117 | 106 | 105 | 109 | 96 |

| Rank | 11 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Culturally disengaged | 61.7 | 51.1 | 42.6 | 48.0 | 30.2 | 51.7 | 32.2 | 26.9 | 39.1 | 21.6 | 18.2 |

| Index | 149 | 123 | 103 | 116 | 73 | 125 | 78 | 65 | 94 | 52 | 44 |

| Rank | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 11 |

| Highly engaged | 3.1 | 5.6 | 9.5 | 3.1 | 15.3 | 4.5 | 12.8 | 23.2 | 11.7 | 26.9 | 36.7 |

| Index | 27 | 49 | 82 | 27 | 132 | 39 | 110 | 200 | 101 | 232 | 317 |

| Rank | 11 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 |

a HASS research awareness: 4 = no awareness to 12 = extremely high level of awareness; b Educational attainment: 1 = secondary or less, 2 = some college or university, 3 = Bachelor level graduate, 4 = graduate education; c Time: 1 = fast < 21.2 min (mean = 15.4), 2 = medium 21.2 to 35.9 min (mean = 27.8), 3 = slow 36+ min (mean = 150.2); bold indicates the two highest values for latent class membership; underlined indicates the two lowest values for latent class membership.

3.6. Correlations between Latent Classes

Posterior probabilities were generated for each respondent in the values, threats, memberships, and activities LC cluster analyses. Respondents were assigned to the cluster for which their probability of membership was highest and correlations between each of these groups of LCs tested (Spearman rank correlation). The values-based latent class assignments were significantly correlated with both the threats-based (rs = 0.15, p < 0.01) and cultural activities-based (rs = 0.08, p < 0.01) latent class assignments. Organizational membership latent class assignments were not significantly correlated with those for any of the other groups.

3.7. Segmentation Summary

The results of this relatively large national survey highlight the large degree of heterogeneity amongst Canadians with regards to their core values, potential threats to quality of life, community engagement, and participation in, and consumption of, cultural services and goods. For core values, six of 15 items for the Schwartz brief scale [46] were used to identify eight distinct LCs nationally. In subsequent CHAID segmentations, age, gender, and survey completion time were statistically significant predictors of six distinct segments that varied according to respondents’ probability of membership in the eight LCs.

Similarly, 11 of 12 potential quality of life indicators were used to identify five LCs within which sample respondents’ threat perception patterns were statistically similar. HASS research awareness, educational attainment, survey completion time, region of residence, and gender all played some role as significant predictors of membership for the various LCs. A total of 13 segments were identified with these predictor variables. All seven membership indicators were used to identify five LCs of community engagement. HASS research awareness, marital status, educational attainment, and citizenship status were predictors of six segments, within which individuals’ probability of membership in the five LCs describing level of engagement were similar. Finally, five of six indicators of cultural engagement and consumption were used to identify three LCs with similar patterns. The probability that an individual belonged to any one (of 11) particular cluster could be predicted using HASS research awareness, educational attainment, gender, and survey completion time.

It is likely that a small proportion of the sample were inattentive when answering the survey quickly. In the core values segmentation (recall Table 2), the segment VAL SEG 01 (16.9% of the sample) was comprised of respondents aged <40 yrs who completed the survey quickly. While it may well be the case that many younger respondents in this segment are technology savvy and can answer Internet-based survey questions quickly, it is also possible that some are completing the survey in a flippant manner. This group tended to belong to LCs where all responses were middle-of-the-scale or unimportant.

In the threat perceptions segmentation, both survey completion time and the dummy variable for choice experiment protestors were significant predictors of LC membership probabilities for respondents with a moderate level of HASS research awareness. Males with intermediate HASS awareness, higher levels of education, and fast survey completion times (10.8% of the sample) were most likely to belong to the LCs placing low priority on arts and heritage. These results imply that these segments may be identifying a mixture of respondents who really are middle-of-the-scale and who view arts and heritage as unimportant and those, perhaps around 5% of the sample, who simply have been grouped with the “true neutrals” due to their quick and inattentive responses.

4. Conclusions

The key finding of this exploratory study was that HASS research awareness acted as a powerful predictor of threat perceptions, levels of community activity, and cultural engagement at the local level (note that I use the term predictor in a modeling sense here; a strong relationship was identified but that does not necessarily imply causality). It was not, however, a significant predictor of core values. From a theoretical perspective, this is in line with a priori expectations as international values [48,61] and VBN theories [44] suggest core values are a precursor to worldviews, threat perceptions, and behaviors (also see [62]).

The strength of the predictive power of HASS research awareness was striking: it was the most powerful predictor for national patterns of quality of life threat perceptions, community organization membership, and cultural engagement and consumption. It was a more powerful predictor of those outcomes than educational attainment alone, but in all three analyses, the combination of HASS research awareness and educational attainment provided a degree of discriminatory power that HASS research awareness alone could not.

Values and threat perception latent classes, and values and cultural engagement latent classes were significantly correlated with each other, while threat perception and cultural engagement latent classes were not. Community-based membership patterns were not correlated with membership patterns from any of the other analyses. As the membership indicators included a mixture of environmental, sports and fitness, service, political, and arts organization indicator variables, it is not particularly surprising that community-based membership patterns are not correlated.

What was, however, surprising was that HASS research awareness was such a strong predictor of community membership and engagement. Canadian respondents were largely unengaged culturally at their community level and the majority was physically inactive. Among the more active and engaged, HASS research awareness was significantly higher relative to the unengaged portion of citizens. O’Brien [5] provided a telling 2011 quote from then-UK Culture Minister that alluded to the importance of free museum access as a means to create future consumers of cultural commodities. The results from this survey suggest a broad and strong relationship between HASS research awareness and citizen engagement and well-being, where individuals with strong awareness of the role that HASS research plays in society themselves play a much more important role in their communities and society. This survey, which was not designed to specifically focus on this issue, is not able to provide evidence regarding the causal relationships among those factors but does highlight that there is a relationship. That is, we cannot say, based on the current results, that HASS awareness boosts engagement or if individuals that are engaged are more likely to follow issues that expose them to the scope of HASS research. Whichever way the relationship runs, the results strongly suggest that HASS exposure does far more than simply create future consumers of cultural commodities.

There are very different policy prescriptions for increasing HASS research awareness and, by extension, Canadian citizens’ cultural and physical engagement, depending on causality and how HASS research awareness affects citizens’ threat perceptions, values, and behavior. VBN theory suggests that threat salience is influenced by worldview, which is itself based on core values, sociocultural factors, and upbringing (recall Figure 1). Following that logic, HASS research awareness may be more influenced by factors likely to be encountered later in life (e.g., news, advertising, media campaigns, university education, etc…). In order to increase HASS research awareness, and community and cultural engagement, interventions that focus on providing individuals (perhaps from the early teens) with better information about the role of HASS in well-being and measures to remove institutional barriers (norms and formal rules—[62]) that prevented people acting on intentions to become more engaged. In this situation, the credibility of HASS researchers and research on HASS research impact may become particularly important as a credible evidence base may be important in influencing adults. Stronger evidence would lead to people to put an increased level of importance on threats to arts and culture, and increase citizens’ propensity to act or support action to address threats. Community- and culturally-engaged citizens may thus be more willing to politically and financially support HASS research investments, potentially leading to a self-reinforcing virtuous cycle.

If, on the other hand, a high level of HASS research awareness was a result of the early-life family and cultural environment a person was brought up within, early life experiences should be the focus of efforts for policy. Experiential learning, rather than formal evidence, would be more important early in life. In the environmental field “nature deficit disorder” (referring to the lack of experience children gain as a result of not being exposed to nature in modern society) has been highlighted as being responsible for a range of phenomena from citizens’ lack of understanding of food supply systems to general lack of concern for environmental conservation [63,64,65]. If HASS awareness, as well as cultural and community engagement were, at their core, a challenge relating to childhood experience, it may be that society is, to echo Louv’s book Last Child in the Woods [63], facing a situation of “last child in the museum”. Given differences in access policy among comparable countries (e.g., the UK’s no-fee policy for access to major museums versus fee-based access in Canadian museums), it may well be possible to develop testable hypotheses and conduct research that empirically identifies the relative importance of these two possible pathways to citizen engagement.

This research project, while not designed specifically to assess the conceptual impacts of HASS research on the general public, suggests this may be a potentially important issue to explore in more detail in the future. The linkages between research awareness and social and cultural engagement will need to be more thoroughly examined, both with regards to their causality and geographic scope, in order to elucidate the causes, social and economic consequences, and policy implications of the relationship.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant from the Presidential Fund initiative “Capturing the Outcomes and Impacts of Canadian Research in the Social Sciences and Humanities” by the Canadian Social Science and Humanities Research Council and the Canada Research Chairs program while the author was at Memorial University.

Abbreviations

| CBA | cost-benefit analysis |

| HASS | humanities, arts, and social sciences |

| LC | latent class |

| STEM | science, technology, engineering and medical |

| VBN | Value-Belief-Norm theory |

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ruth Levitt, Claire Celia, Stephanie Diepeveen, Stephanie N. Chonaill, Lila Rabinovic, and Jan Tiessen. Assessing the Impact of Arts and Humanities Research at the University of Cambridge. Cambridge: RAND Europe, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jordi Molas-Gallart, and Puay Tang. “Tracing ‘productive interactions’ to identify social impacts: An example from the social sciences.” Research Evaluation 20 (2011): 219–26. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Benneworth. “Tracing how arts and humanities research translates, circulates and consolidates in society: How have scholars been reacting to diverse impact and public value agendas? ” Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 14 (2015): 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Helen Small. The Value of the Humanities. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dave O’Brien. “Cultural value, measurement and policy making.” Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 14 (2015): 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Costanza, Brendan Fisher, Saleem Ali, Caroline Beer, Lynne Bond, Roelof Boumans, Nicolas L. Danigelis, Jennifer Dickinson, Carolyn Elliott, Joshua Farley, and et al. “Quality of life: An approach integrating opportunities, human needs, and subjective well-being.” Ecological Economics 61 (2007): 267–76. [Google Scholar]

- Heide Hackmann, Susanne C. Moser, and Asuncion Lera St. Clair. “The social heart of global environmental change.” Nature Climate Change 4 (2014): 653–55. [Google Scholar]

- Joanne Kauffman. “Promoting integration and cooperation for sustainability views from the symposium held at UNESCO headquarters September 19, 2013.” Sustainability Science 9 (2014): 419–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gisli Palsson, Bronislaw Szerszynski, Sverker Sörlin, John Marks, Bernard Avril, Carole Crumley, Heide Hackmann, Poul Holm, John Ingram, Alan Kirman, and et al. “Reconceptualizing the ‘Anthropos’ in the Anthropocene: Integrating the social sciences and humanities in global environmental change research.” Environmental Science & Policy 28 (2013): 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Murray A. Rudd. “How research-prioritization exercises affect conservation policy.” Conservation Biology 25 (2011): 860–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- David Victor. “Climate change: Embed the social sciences in climate policy.” Nature 520 (2015): 27–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eleonora Belfiore. “‘Impact’, ‘value’ and ‘bad economics’: Making sense of the problem of value in the arts and humanities.” Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 14 (2015): 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Alan Brinkley. “Landscape of Humanities Research and Funding.” 2009. Available online: http://archive201406.humanitiesindicators.org/essays/brinkley.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2015).

- Claire A. Donovan. “Government Policy and the Direction of Social Science Research.” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Sussex, Sussex, UK, November 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce Gardner, and William Lesser. “International agricultural research as a global public good.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 85 (2003): 692–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan Grant, Philipp-Bastian Brutscher, Susan E. Kirk, Linda Butler, and Steven Wooding. Capturing Research Impacts: A Review of International Practice. Cambridge: RAND Europe, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shyama Kuruvilla, Nicholas Mays, Andrew Pleasant, and Gill Walt. “Describing the impact of health research: A research impact framework.” BMC Health Services Research 6 (2006): 134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Council of Canadian Academies. The State of Science and Technology in Canada. Ottawa: Council of Canadian Academies, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Council for the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences (CHASS). Measures of Quality and Impact of Publicly Funded Research in the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences. Canberra: CHASS, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Einar Bowitz, and Karin Ibenholt. “Economic impacts of cultural heritage—Research and perspectives.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 10 (2009): 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelle Reeves. Measuring the Economic and Social Impact of the Arts: A Review. London: Arts Council of England, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ståle Navrud, and Richard C. Ready. Valuing Cultural Heritage: Applying Environmental Valuation Techniques to Historic Buildings, Monuments and Artefacts. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas S. Noonan. “Contingent valuation and cultural resources: A meta-analytic review of the literature.” Journal of Cultural Economics 27 (2003): 159–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray A. Rudd. “An exploratory analysis of societal preferences for research-driven quality of life improvements in Canada.” Social Indicators Research 101 (2011): 127–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran H. Tuan, and Ståle Navrud. “Capturing the benefits of preserving cultural heritage.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 9 (2008): 326–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktor L. Adamowicz. “What’s it worth? An examination of historical trends and future directions in environmental valuation.” The Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 48 (2004): 419–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark Sagoff. “Should preferences count? ” Land Economics 70 (1994): 127–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Dewey. Logic: The Theory of Inquiry. New York: Holt, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Sagoff. “The quantification and valuation of ecosystem services.” Ecological Economics 70 (2011): 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricky N. Lawton, and Murray A. Rudd. “Strange bedfellows: Ecosystem services, conservation science, and central government in the United Kingdom.” Resources 2 (2013): 114–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Spoehr, Kate Barnett, Simon Molloy, Sanjugta V. Dev, and Ann-Louise Hordacre. Connecting Ideas: Collaborative Innovation for a Complex World. Adelaide: Australian Institute for Social Research, University of Adelaide, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Banks, and Justin O’Connor. “After the creative industries.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 15 (2009): 365–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph L. Koerner, and Lisbet Rausing. “Value.” In Critical Terms for Art History, 2nd ed. Edited by Robert S. Nelson and Richard Shiff. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996, pp. 419–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan Bate. The Public Value of the Humanities. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arts Council England (ACE). Cultural Capital: A Manifesto for the Future. London: ACE, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Alan S. Brown, Jennifer L. Novak, and Amy Kitchener. “Cultural Engagement in California’s Inland Regions.” 2008. Available online: http://www.giarts.org/sites/default/files/Cultural-Engagement-in-Californias-Inland-Regions.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2015).

- Kate Clark, and Gareth Maeer. “The cultural value of heritage: Evidence from the Heritage Lottery Fund.” Cultural Trends 17 (2008): 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoyong Kim, and Hyesun Kim. “Does cultural capital matter? Cultural divide and quality of life.” Social Indicators Research 93 (2009): 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jane Macnaughton, Mike White, and Rosie Stacy. “Researching the benefits of arts in health.” Health Education 105 (2005): 332–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jude Ortiz, and Gayle Broad Culture. Culture, Creativity, and the Arts: Achieving Community Resilience and Sustainability through the Arts in Sault Ste. Marie. Saskatoon: Centre for the Study of Co-Operatives, University of Saskatchewan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Susan Galloway. “Cultural participation and individual quality of life: A review of research findings.” Applied Research in Quality of Life 1 (2006): 323–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Throsby. “Determining the value of cultural goods: How much (or how little) does contingent valuation tell us? ” Journal of Cultural Economics 27 (2003): 275–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andy Choi, Franco Papandrea, and Jeff Bennett. “Assessing cultural values: Developing an attitudinal scale.” Journal of Cultural Economics 31 (2007): 311–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul C. Stern. “Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior.” Journal of Social Issues 56 (2000): 407–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley E. Dunlap, Kent D. van Liere, Angela G. Mertig, and Robert E. Jones. “Measuring endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A revised NEP scale.” Journal of Social Issues 56 (2000): 425–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul C. Stern, Thomas Dietz, and Gregory A. Guagnano. “A brief inventory of values.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 58 (1998): 984–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalom H. Schwartz. “Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? ” Journal of Social Issues 50 (1994): 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalom H. Schwartz. “An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values.” Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sao-Wen Cheng. “Cultural goods creation, cultural capital formation, provision of cultural services and cultural atmosphere accumulation.” Journal of Cultural Economics 30 (2006): 263–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claire A. Donovan. “The Australian Research Quality Framework: A live experiment in capturing the social, economic, environmental, and cultural returns of publicly funded research.” New Directions for Evaluation 2008 (2008): 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay Magidson, and Jeroen K. Vermunt. “Latent class models.” In The Sage Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. Edited by David Kaplan. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2004, pp. 175–98. [Google Scholar]

- Jeroen K. Vermunt, and Jay Magidson. “Latent class cluster analysis.” In Applied Latent Class Analysis. Edited by Jacques A. Hagenaars and Allan L. McCutcheon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002, pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques A. Hagenaars, and Allan L. McCutcheon. Applied Latent Class Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Juan Pulido-Fernández, and Marcelino Sánchez-Rivero. “Attitudes of the cultural tourist: A latent segmentation approach.” Journal of Cultural Economics 34 (2010): 111–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeroen K. Vermunt, and Jay Magidson. Technical Guide for Latent GOLD 4.0: Basic and Advanced. Belmont: Statistical Innovations Inc., 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nissan Levin, and Jacob Zahavi. “Predictive modeling using segmentation.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 15 (2001): 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon V. Kass. “An exploratory technique for investigating large quantities of categorical data.” Applied Statistics 29 (1980): 119–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay Magidson, and Jeroen K. Vermunt. “An extension of the CHAID tree-based segmentation algorithm to multiple dependent variables.” In Classification: The Ubiquitous Challenge. Edited by Claus Weihs and Wolfgang Gaul. Heidelberg: Springer Heidelberg, 2005, pp. 176–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cathy H. C. Hsu, and Soo K. Kang. “CHAID-based segmentation: International visitors’ trip characteristics and perceptions.” Journal of Travel Research 46 (2007): 207–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay Magidson. SI-CHAID 4.0 User’s Guide. Belmont: Statistical Innovations Inc., 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shalom H. Schwartz. “Rethinking the concept and measurement of societal culture in light of empirical findings.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 45 (2014): 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinor Ostrom. Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Louv. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Chapel Hill: Algonquin, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Roger Walsh. “Lifestyle and mental health.” American Psychologist 66 (2011): 579–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nancy M. Wells, and Kristi S. Lekies. “Nature and the life course: Pathways from childhood nature experiences to adult environmentalism.” Children, Youth and Environments 16 (2006): 1–24. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).