Abstract

(1) Background: The pathways perspective considers how different biological, psychological, and social experiences affect women compared to men and how these experiences can lead to initial justice-involvement and recidivism. The relational model provides context for understanding women’s pathways to the criminal justice system. Interpersonal relationships have strong effects on women’s likelihood to offend. The relationship between risk factors like childhood victimization, adult relationship dysfunction, self-esteem, and self-efficacy are less clear. (2) Methods: Using a sample of justice-involved women, the current study uses a path analysis to investigate the impact of childhood physical abuse on adult relationship dysfunction and if this relationship is mediated by self-esteem and/or self-efficacy. (3) Results: Childhood physical abuse was found to have a significant negative effect on self-esteem and self-efficacy as well as a significant positive effect on adult relationship dysfunction. Indirect relationships were not significant. (4) Conclusions: The current study verifies previous pathways analysis but does not support self-esteem and self-efficacy as mediators of adult relationship dysfunction.

1. Introduction

Over the last 30 years, best practices for intervening with criminal justice populations has been guided by the principles of risk–need–responsivity (RNR) (Andrews et al. 1990b; Bonta and Andrews 2023). The risk principle asserts that the intensity of interventions should match an individual’s risk level, with emphasis on medium- and high-risk populations. The need principle says that interventions must target primarily criminogenic needs. The responsivity principle emphasizes effective means of intervention such as utilizing cognitive-behavioral and skill building strategies. The efficacy of these principles is reliant on appropriately identifying the risks and needs of justice-involved persons (Andrews et al. 1990a; Blanchette and Brown 2006; Bonta and Andrews 2023; Salisbury and Van Voorhis 2022).

Women are the fastest growing correctional population in the United States representing a 500% increase over the last 30 years (The Sentencing Project 2022; Zeng 2022). Women currently make up approximately 7% of the overall prison population and 24% of the population on probation in 2021 (Carson 2022; Kaeble 2023). Decades of scholarship on corrections and correctional interventions have focused on the perspectives of the majority male population (Chesney-Lind 1999; Daly and Chesney-Lind 1988; Davidson and Chesney-Lind 2009). While men and women share some risk factors for justice involvement, women have experiences that inform their unique pathways into the criminal justice system and ongoing risk factors and needs once there (DeHart 2018; Salisbury and Van Voorhis 2009, 2022). Attempts to supervise women in systems built around the identified risks and needs of men leads to significant frustration by criminal justice staff and the perception that women are more difficult to oversee (Baines and Alder 2016; Dodge 1999; Gaarder et al. 2004; Keen et al. 2023; Seng and Lurigio 2005).

The women’s pathways perspective considers how different biological, psychological, and social experiences affect women compared to men, and how these experiences can lead to initial justice-involvement and recidivism (Belknap et al. 1997; DeHart et al. 2014; DeHart and Lynch 2021; Salisbury and Van Voorhis 2009; Van Voorhis et al. 2010).

1.1. Childhood Physical Abuse

While childhood abuse is not unique to women in the justice system, nor does it affect all justice-involved women, the kinds and rates of abuse experienced by women are distinct to that of men. Girls report higher rates of abuse in childhood compared to boys (Finkelhor 2008; Finkelhor et al. 2015; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2023). One study of incarcerated delinquent youth found that the girls in their sample experienced higher rates of abuse overall compared to boys, and physical abuse specifically (Belknap and Holsinger 2006). In particular, girls, compared to boys, experienced more physical abuse from family members (75% vs. 63%), more physical abuse from people outside their families (65% vs. 36%), and more repeated experiences of physical abuse over time (63% vs. 43%). Girls who have experienced physical abuse during childhood are more likely to engage in delinquency, experience symptoms of PTSD, and use substances during youth (Auslander et al. 2016; Kilpatrick et al. 2003). Girls who have experienced physical abuse have also been found to demonstrate more frequent aggressive behaviors (Auslander et al. 2016). Studies have also found that girls who experience abuse may also suffer from long term mental and emotional impacts such as depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, post-traumatic stress, and substance use disorder (Auslander et al. 2016, 2018; McMillen et al. 2005; Salokangas et al. 2020; Springer et al. 2007). Women with histories of physical abuse in childhood have also been shown to be at increased risk of future victimization (Aakvaag et al. 2017; Afifi et al. 2017; Auslander et al. 2018; Browne and Finkelhor 1986; Finkelhor et al. 2015)

Abuse experienced in childhood is a significant pathway for women’s criminal involvement (Auslander et al. 2018; Belknap and Holsinger 2006; Brennan et al. 2012; Brennan and Jackson 2022; DeHart 2018; Salisbury and Van Voorhis 2009; Saxena and Messina 2021). Childhood physical abuse has been linked to lower educational attainment and economic stability, higher externalizing mental disorder behaviors, and increased criminal legal involvement for men and women over their lifetime (Lansford et al. 2021). Salisbury and Van Voorhis (2009) describe a pathway model in which self-reported childhood physical abuse was significantly related to a history of mental illness, current depression/anxiety, and both static and dynamic forms of substance use. Through these factors, childhood physical abuse is significantly indirectly related to admission to prison.

1.2. Relationship Dysfunction

The relationship between childhood experiences of violence, especially in the home, and either the perpetration or victimization of intimate partner violence is well documented (Briggs et al. 2021; Browne and Finkelhor 1986; Friesen et al. 2010; Jung et al. 2019; Stith et al. 2000). Childhood abuse has been linked to negative development outcomes including difficulty developing trust and intimacy in future relationships (Pepin and Banyard 2006; Tardif-Williams et al. 2017). For women, violence in the home has been found to be more strongly linked to future victimization by a partner compared to men (Jones et al. 2018; Stith et al. 2000). Valerio and Lepper, in a qualitative study of women survivors of child sexual abuse, found that for some women, “one index of trauma is a preoccupation with the abuse and a pattern of becoming involved in relationships which contribute to the sense of being ‘damaged goods’” (Valerio and Lepper 2009, p. 151). Treating issues of self-esteem and self-efficacy are central goals of therapeutic interventions for survivors and can promote improved interpersonal relationships in the future (Lei et al. 2023; Marshall et al. 2020; Valerio and Lepper 2009).

Research has also connected experiences of childhood physical abuse to low relationship quality in adulthood (Vaillancourt-Morel et al. 2024; Zamir 2022). A study using structural equation modeling (SEM) to explore the relationship between childhood abuse and relationship stability found that higher frequency of childhood physical abuse was significantly related to higher relationship distress for women (Larsen et al. 2011). This literature explores possible mediating and protective factors such as attachment styles, psychological distress/resilience, behavioral factors, and demographic factors, though findings are largely inconclusive (Vaillancourt-Morel et al. 2024; Zamir 2022).

1.3. Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy

Prior research indicates that childhood abuse is related to future self-esteem and self-efficacy. Self-esteem can connote an individual’s sense of self-worth and internal locus of control. Self-efficacy indicates an individual’s confidence in their ability to achieve goals and perform tasks. The two concepts are distinct but inherently related to one another. Self-esteem and self-efficacy have been linked to criminal offending in women as part of broader pathways analyses (Salisbury et al. 2009; Salisbury and Van Voorhis 2009; Van Voorhis et al. 2010). Previous research on the long-term effects of childhood abuse indicate that self-esteem and self-efficacy may play a substantial role in dysfunctional relationship patterns that contribute to criminal offending. Abuse experienced in childhood has long been linked to poor mental health outcomes including anxiety, depression, feelings of stigma, and poor self-esteem, along with behaviors such substance use, self-harm, and aggression (Auslander et al. 2016; Belknap and Holsinger 2006; Browne and Finkelhor 1986; Messina and Grella 2006; Pereira et al. 2021; Valerio and Lepper 2009). Childhood physical abuse can have long term deleterious effects on self-esteem into adulthood (Çelik and Odacı 2020; Salokangas et al. 2020; Shen 2009).

Decreased self-esteem is a devaluation of the self, resulting from shame and self-consciousness related to abuse (Fereidooni et al. 2023; Vidal and Petrak 2007). Previous research has not found self-esteem to mediate the relationship between childhood abuse and adult relationship quality (Friesen et al. 2010; McCarthy and Taylor 1999; Zamir 2022). It should be noted that these previous studies did not specifically target justice-involved women nor physical abuse alone. The effect, if any, that self-esteem and self-efficacy may have on the relationship between childhood physical abuse and adult relationship in women involved in the justice system is unclear. Low self-esteem or self-efficacy do not cause a perpetrator to commit acts of physical or emotional violence nor justify these acts. It is worth considering if high self-esteem or self-efficacy may act as protective factors for future violence or simply improve relationship quality for justice-involved women. This relationship could guide future interventions.

1.4. The Relational Model

The relational model of development was derived from feminist relational theory in the 1980s and 1990s (Koggel et al. 2022). The model refocuses women’s psychosocial development from the perspective of women rather than using a gender-neutral lens which focuses on individual identity (Covington 2007; Covington and Surrey 1997). By centering women’s perspectives, researchers learned that women are primarily motivated by a need to establish connection with others in their lives (Covington 2007; Covington and Surrey 1997; Miller 1986). The relational model traces pathologized behavior to experiences of disconnection and/or violation in close interpersonal relationships like families, friendships, or romantic relationships. Similarly, healthy mutual relationships create constant opportunity for change and improvement.

The relational model provides context for understanding women’s pathways to the criminal justice system. Interpersonal relationships have strong effects on women’s likelihood to offend (Barlow and Weare 2019; Bloom et al. 2003; Covington 2007; Covington and Surrey 1997; Salisbury and Van Voorhis 2009). Salisbury and Van Voorhis (2009) highlight three ways relationships can influence pathways to criminal offending: (a) childhood victimization, (b) dysfunctional relationships and victimization as an adult, and (c) social and human capital as it impacts employment/financial stability. Women in dysfunctional relationships may use substances as a means of connecting with a partner, family member, or friend that uses (Covington and Surrey 1997). Relationships, especially romantic relationships, are common precursors of criminal offending for women (Barlow and Weare 2019; Bloom et al. 2003; Covington 2007; Covington and Surrey 1997; Salisbury and Van Voorhis 2009). Co-offending relationships may be, like substance use, a means of connecting with a friend or partner and could be a result of either love or fear (Barlow and Weare 2019). Relationship dysfunction can also have an indirect effect on criminal offending by increasing risk of future victimization, reducing self-esteem and self-efficacy, and causing psychological symptoms such as depression and anxiety (Covington 2007; Salisbury and Van Voorhis 2009).

1.5. The Current Study

The connection between childhood abuse and adult relationship quality has been well documented (Zamir 2022). Previous research has indicated that justice-involved women and women in the general population may experience different effects of previous victimization (Radatz and Wright 2017). However, the majority of studies conflate one or more forms of abuse into a single measure, which makes drawing conclusions about individual types of abuse difficult (see Horwitz et al. 2001; Pepin and Banyard 2006; Pereira et al. 2021 for examples). Few studies have explored mediating and protective factors using samples of justice-involved women or focused on the role of physical abuse histories specifically (DeHart 2018). Current pathways research has demonstrated significant relationships leading from childhood victimization and relationship dysfunction to other risk factors such as mental health, substance use disorder, self-efficacy, and future offending behaviors (Salisbury and Van Voorhis 2009). Previous pathways research has explored how these risk factors relate to offending but has not explored how these risk factors relate to one another. Understanding what mechanisms may impact relationship quality for justice-involved women could inform future interventions with this population. Using a sample of justice-involved women, the current study uses a path analysis to investigate the impact of childhood physical abuse on adult relationship dysfunction and if this relationship is mediated by self-esteem and/or self-efficacy

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

The sample for the current study was drawn from a pilot study for the Women’s Risk Need Assessment (WRNA) project that was conducted in Maui County, Hawaii (The University of Utah 2025; Van Voorhis et al. 2006). The WRNA project was a National Institute of Corrections (NIC)-funded research study to design and validate a gender-responsive risk and needs assessment for correctional settings. Data were collected between June 2003 and October 2005. Maui County was originally selected as a research site due to the probation agency’s interest in implementing strategies to improve services for their female population and the overall research opportunity. All participants (a) had at least six months of supervision remaining on their term, (b) were convicted of a felony, and (c) could speak English (Van Voorhis et al. 2006). Women on probation or parole meeting these criteria were asked to participate in the study. Researchers were given access to intake materials, including responses to a gender-neutral risk assessment and background information. Additionally, participants were asked to complete five self-report surveys. This survey asked about gender-responsive risk factors including relationships, self-esteem, self-efficacy, parenting, and victimization experiences in childhood and as an adult (Van Voorhis et al. 2010). The current study uses responses from four gender-responsive scales: intimate relationships, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and childhood physical abuse. Only participants who completed at least one of these gender-responsive surveys were included.

The current sample included 192 cisgender women serving either probation or parole in Maui County, Hawaii during the study dates. Demographic characteristics and criminal history are included below in Table 1. The average age of women in the sample was 34.7 years. The sample was racially diverse with the majority (43.2%) identifying as Hawaiian or part Hawaiian. White women were the next largest grouping with 26.6% of the total population. The sample also included a substantial number of Filipinos, Asians, Pacific Islanders (not Hawaiian), and mixed-race women. Many women in the sample had at least one prior felony (34%). Women were also asked about the most serious offense they had been charged with. Of those who replied, the most common were theft or substance related crimes. More than half (56%) were charged with their first offense before the age of 25. This sample was chosen because it was previously used to validate measures of women’s criminogenic risks and included a high incidence of reported childhood physical abuse. The size and demographic characteristics of the sample will however limit the generalizability of findings.

Table 1.

Sample demographics and criminal histories.

2.2. Gender-Responsive Scales

Four gender-responsive scales were used in the current analysis. Descriptive statistics for these scales can be found in Table 2. The predictive reliability of each scale is available in Table 3.

Table 2.

Gender-responsive scales descriptives.

Table 3.

Gender-responsive scales reliability.

2.2.1. Childhood Physical Abuse Scale

The WRNA pilot included a scale covering a wide variety of physical and emotional abuse during both adulthood and childhood derived from several known indices (Campbell et al. 1994; Coleman 1997; Holsinger et al. 1999; Murphy and Hoover 1999; Rodenburg and Fantuzzo 1993; Shepard and Campbell 1992). The child abuse scale included 38 behavioral indicators of physical and emotional abuse. The scale described behavior experienced by the respondent and asked them to rank their experience on a three-point Likert scale (Never, Less than 5 times, More than 5 times). Since the scale was not a previously validated measure of abuse, correlations were assessed and an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to determine which measures best assessed individual forms of childhood abuse (Yong and Pearce 2013). The analysis identified 13 items related to physical abuse experienced in childhood such as ‘spanked/slapped you’, ‘beat you’, and ‘burned/scalded you’ (see Table 1). These measures all showed moderate to high correlation with each other and high reliability (alpha = 0.932). All loadings were well above the acceptable 0.3. These measures all showed moderate to high correlation with each other and high reliability (alpha = 0.932). Within the sample, 74% of women indicated having experienced at least one incident of physical abuse as a child. Analysis of emotional abuse measures did not demonstrate significant strength to warrant its inclusion as an additional abuse scale.

2.2.2. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

Self-esteem was measured using a previously validated 10-item scale (Rosenberg 1979). Respondents were asked to rank their perceptions of self on a 3-point scale (often/most of the time, sometimes, seldom) asking questions such as ‘Do you feel that you are a person of worth—at least equal to others?’, ‘Do you feel like a failure?’, and ‘Can you do things as well as most other people?’. Four questions were reverse coded in analysis (3, 8–10) to measure the reliability of the scale (alpha = 0.89).

2.2.3. Sherer Self-Efficacy Scale

Self-efficacy was measured using a previously validated 17-point scale (Sherer et al. 1982). The scale asked questions such as ‘When you make plans, are you fairly certain that you can make them work?’, ‘Do you have problems getting down to work when you should?’, and ‘When you set important goals for yourself, do you have trouble achieving them?’ and asked them to rank their experiences on a 3-point scale (most of the time, sometimes, seldom). Eight items were reverse coded (1,3, 8, 9, 11, 13, 15, and 17) to measure scale reliability (alpha = 0.91).

2.2.4. Relationship Dysfunction Scale

The relationship dysfunction scale attempts to “identify women who were experiencing relationship difficulties resulting in a loss of personal power”, also sometimes referred to as codependency (Van Voorhis et al. 2006). The scale is made up of 15 items, influenced by multiple sources (Fischer and Spann 1991; Jack and Dill 1992; Roehling and Gaumond 1996). Two items (4 and 15) were dropped from this analysis due to low correlation with the other measures. Of the remaining 13 items, 10 use a 3-point scale to measure responses (often, sometimes, seldom). These questions included, “Do you worry about what others think of you?’, ‘Have significant others loved and appreciated you for who you are?’, and ‘Do you tend to put your significant other’s needs ahead of your own?’. Two other questions used a binary yes/no scale. These questions were ‘In general, would you describe these relationships as supportive and satisfying?’ and ‘Do you get into relationships that are painful for you? Or is your present relationship a painful one?’. These two questions were recoded to fit the 3-point scale used in the other items. One last question was, ‘Would you describe yourself as one who is open with your partner about your feelings or do you tend to hold back, especially when it might cause conflict to say what you feel?’, which was measured on a 3-point scale (open, sometimes open, hold back). This item was also recoded to match the rest of the scale. Four items were reverse coded (5–7, 11) to allow for reliability testing (alpha = 0.800).

2.3. Analysis Plan

The current study utilizes a free path analysis to analyze the relationship between four gender-responsive scales (relationship dysfunction, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and childhood physical abuse) (Streiner 2005). In particular, the current study explores the pathway between childhood physical abuse and relationship dysfunction as an adult. Factor analyses were conducted on each scale to determine appropriateness with the sample. A path analysis was chosen to better understand the direction and strength of the relationship between variables that are known to be related. Control variables were not included for this exploratory analysis. Previous studies have indicated that covariates such as gender, socioeconomic status, and age (adolescent or adult) could impact the analysis (Zamir 2022). The current sample, however, is already limited to adult women on community supervision. Additionally, given the racial/ethnic makeup of the sample, controlling for race would not improve the generalizability of the findings. The proposed model then considers self-esteem and self-efficacy as mediators of childhood abuse and adult relationship dysfunction. Mediation was assessed by determining if the specific indirect effect of self-esteem and self-efficacy on the relationship between childhood abuse and relationship dysfunction was significant (p < 0.05) and straddled zero (Memon et al. 2018; Preacher and Hayes 2004; Zhao et al. 2010). Bootstrapping (r = 5000) was used due to the small sample size.

3. Results

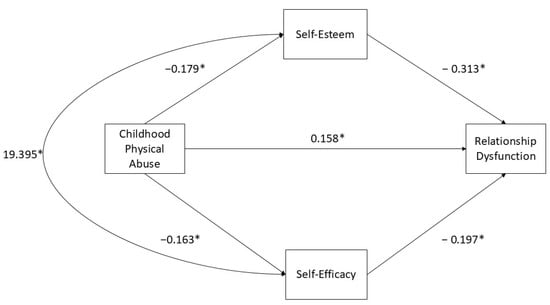

Path model results can be found in Figure 1. Straight lines can be understood as unstandardized OLS coefficients. While curved lines should be understood as correlations. Only paths that meet a p ≤ 0.05 criteria are shown. The model tests the relationship between childhood physical abuse and adult relationship dysfunction as mediated by self-esteem and self-efficacy. The model shows that all direct relationships were found to be significant, see Table 4. For each additional point of childhood physical abuse experienced by respondents, self-esteem decreased by 0.179, self-efficacy decreased by 0.163 and relationship dysfunction increased by 0.158. Self-esteem and self-efficacy are strongly correlated (p < 0.001) as expected. The indirect relationships between childhood physical abuse and relationship dysfunction with both mediators were, however, not significant. The model can account for 34% of the total variance (R2 = 0.34, p < 0.001), see Table 5.

Figure 1.

Path model. * p ≤ 0.05.

Table 4.

Path analysis model unstandardized statistics.

Table 5.

Path model fit.

Standard coefficients provide additional information on how the measures relate to one another. While both self-esteem and self-efficacy have significant relationships to childhood physical abuse, self-esteem has a stronger relationship. Additionally, while relationship dysfunction has significant relationships with other variables, it has the strongest relationship with childhood physical abuse.

4. Discussion

The current study adds to the women’s pathways literature by exploring a potential pathway between childhood physical abuse and adult relationship disfunction. The current model demonstrated that childhood physical abuse can negatively impact self-efficacy and self-esteem in adulthood. This finding is largely consistent with the pathways literature detailing women’s risk and protective factors for criminal legal involvement (Salisbury and Van Voorhis 2009; Van Voorhis et al. 2010). This finding also helps to connect pathways research with the literature detailing the long-term effects of childhood trauma such as ongoing mental health symptoms, relationship dysfunction, and substance use disorder (Auslander et al. 2018; Browne and Finkelhor 1986; Çelik and Odacı 2020; Finkelhor 2008; Pereira et al. 2021; Stith et al. 2000). Similar pathways to juvenile offending have been identified for girls who have experienced abuse (Crosby et al. 2022; Kerig 2018; Modrowski and Kerig 2019).

Additionally, childhood physical abuse was shown to have a positive link to adult relationship dysfunction. This finding is also consistent with the literature on the relationship between childhood and adult victimization for women (Aakvaag et al. 2017; Brunton and Dryer 2024; Fereidooni et al. 2023). Early experiences of abuse have long term consequences on women’s sense of self-worth and can promote entering and staying in unhealthy intimate relationships (Brunton and Dryer 2024; Chen 2010; Pepin and Banyard 2006; Pereira et al. 2021). The model, however, also attempted to test whether self-esteem and self-efficacy mediates the relationship between childhood abuse and relationship dysfunction. Like previous studies with different populations, this test did not demonstrate significance (Friesen et al. 2010; McCarthy and Taylor 1999). While all the variables do affect one another, self-esteem and self-efficacy did not mediate the effect of childhood victimization on adult relationships. Previous studies have found significant mediators that may undermine the potential impact of self-esteem and self-efficacy such as early onset substance use and sexual activity, insecure attachment styles, self-regulation skills, use of coping strategies, and psychological distress (Friesen et al. 2010; Larsen et al. 2011; McCarthy and Taylor 1999; Zamir 2022). Frequency of childhood physical abuse may relate to adult relationship dysfunction due to a combination of behavioral and experiential factors such as (1) early onset substance use and sexual risk-taking leading to early cohabitation and instability, (2) repressed social skill development impacting women’s ability to effectively navigate partnerships and conflict, (3) development of insecure attachment styles, and (4) untreated substance use disorder or dependance. Additional research is needed to determine if these mediating factors are equally significant with justice-involved women. Had self-esteem and self-efficacy been found to significantly mediate the impact of child abuse on relationship dysfunction, it would have warranted exploring additional avenues of treatment for justice-involved women. Instead, the findings do not justify a departure from current gender-responsive practices (Blanchette and Brown 2006; Bloom et al. 2003; Salisbury and Van Voorhis 2022).

The current study poses several limitations. First, path analysis does not provide proof of cause or effect. The model demonstrates that a relationship exists between the variables, but readers cannot presume more than with conventional regression. Longitudinal data would be required to draw conclusions about order of variables. Second, the sample was too small for a more intensive model, like structural equation modelling. A larger sample would allow for more detailed models allowing researchers to determine additional points of intervention. The distinct cultural characteristics of the site should be considered as a potential limitation in generalizability of results below. The sample size and demographics also prohibit generalizability of results to the wider population. Third, in order to verify that the pathways discussed are gender-specific, the model should be compared to a sample of men. Future research should compare samples of men and women to determine if such findings are indeed gender-specific or understudied in men. Fourth, the current sample was pulled from a larger research project focused on women’s risk factors and pathways conducted nearly 20 years prior. Researchers are currently using adapted scales of the Women’s Risk Needs Assessment (Van Voorhis et al. 2010) that may provide different conclusions.

Despite these limitations, the current study supports and fits within the larger context of the literature on women’s criminal offending pathways and attempts to add additional nuance to previous research. In particular, results support the general consensus among feminist pathways researchers that trauma-informed services and interventions should be utilized among this population (Bloom et al. 2003; DeHart 2018; Wanamaker and Brown 2021). Both early intervention and the treatment of trauma experienced by children, as well as subsequent psychosocial effects, continue to have influence over women’s behavior, such as negative relationships with the self and intimate partners. Future studies should continue to explore the interrelationship between childhood victimization and adult relationship dysfunction as both are important pathways for women. Greater knowledge in the interrelationship and mechanisms of women’s criminogenic pathways is critical for developing appropriate treatment interventions, refining risk/need assessments, and identifying areas of early intervention for at-risk girls.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F. and E.S.; Methodology, M.F.; Formal analysis, M.F.; Investigation, E.S.; Resources, E.S.; Data curation, E.S.; Writing—original draft, M.F.; Writing—review and editing, E.S.; Visualization, M.F.; Supervision, E.S.; Project administration, E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of a de-identified secondary data set.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the original data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable to the public due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aakvaag, Helene Flood, Siri Thoresen, Tore Wentzel-Larsen, and Grete Dyb. 2017. Adult victimization in female survivors of childhood violence and abuse: The contribution of multiple types of violence. Violence Against Women 23: 1601–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, Tracie O., Natalie Mota, Jitender Sareen, and Harriet L. MacMillan. 2017. The relationships between harsh physical punishment and child maltreatment in childhood and intimate partner violence in adulthood. BMC Public Health 17: 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Don A., James Bonta, and Robert D. Hoge. 1990b. Classification for effective rehabilitation: Rediscovering psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior 17: 19–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Donald A., Ivan Zinger, Robert D. Hoge, James Bonta, Paul Gendreau, and Francis T. Cullen. 1990a. Does correctional treatment work? A clinically relevant and psychologically informed meta-analysis. Criminology 28: 369–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auslander, Wendy, Paul Sterzing, Jennifer Threlfall, Donald Gerke, and Tonya Edmond. 2016. Childhood Abuse and Aggression in Adolescent Girls Involved in Child Welfare: The Role of Depression and Posttraumatic Stress. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 9: 359–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auslander, Wendy, Sarah Myers Tlapek, Jennifer Threlfall, Tonya Edmond, and Jerry Dunn. 2018. Mental health pathways linking childhood maltreatment to interpersonal revictimization during adolescence for girls in the child welfare system. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 33: 1169–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, Margaret, and Christine Alder. 2016. Are girls more difficult to work with? Youth workers’ perspectives in juvenile justice and related areas. Crime & Delinquency 42: 467–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, Charlotte, and Siobhan Weare. 2019. Women as co-offenders: Pathways into crime and offending motivations. Howard Journal of Crime and Justice 58: 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belknap, Joanne, and Kristi Holsinger. 2006. The Gendered Nature of Risk Factors for Delinquency. Feminist Criminology 1: 48–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belknap, Joanne, Kristi Holsinger, and Melissa Dunn. 1997. Understanding incarcerated girls: The results of a focus group study. Prison Journal 77: 381–405. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette, Kelley, and Shelley L. Brown. 2006. The Assessment and Treatment of Women Offenders: An Integrative Perspective. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Barbara, Barbara Owen, Stephanie Covington, and M. Raeder. 2003. Gender-Responsive Strategies: Research, Practice, and Guiding Principles for Women Offenders; Washington, DC: National Institute of Corrections. Available online: https://www.worldcat.org/title/gender-responsive-strategies-research-practice-and-guiding-principles-for-women-offenders/oclc/52632840 (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Bonta, James, and Donald Arthur Andrews. 2023. The Psychology of Criminal Conduct, 7th ed. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, Tim, and Eugenie Jackson. 2022. Women’s pathways: Replication and generalizability across state prison systems. Criminal Justice and Behavior 49: 1323–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, Tim, Markus Breitenbach, William Dieterich, Emily J. Salisbury, and Patricia van Voorhis. 2012. Women’s pathways to serious and habitual crime: A person-centered analysis incorporating gender responsive factors. Criminal Justice and Behavior 39: 1481–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, Ernestine C., Lisa Amaya-Jackson, Karen T. Putnam, and Frank W. Putnam. 2021. All adverse childhood experiences are not equal: The contribution of synergy to adverse childhood experience scores. American Psychologist 76: 243–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, Angela, and David Finkelhor. 1986. Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research. Psychological Bulletin 99: 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, Robyn Joy, and Rachel Dryer. 2024. Intimate Partner Violence Risk Factors: A Vulnerability-Adaptation Stress Model Approach. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 39: 3738–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Doris W., Jacquelyn Campbell, Christine King, Barbara Parker, and Josephine Ryan. 1994. The reliability and factor structure of the Index of Spouse Abuse with African-American women. Violence and Victims 9: 259–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson, E. Ann. 2022. Prisoners in 2021—Statistical Tables; Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/prisoners-2021-statistical-tables (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Chen, Gila. 2010. Gender differences in sense of coherence, perceived social support, and negative emotions among drug-abstinent israeli inmates. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 54: 937–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney-Lind, Meda. 1999. The forgotten offender. Corrections Today 60: 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, Frances L. 1997. Stalking behavior and the cycle of domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 12: 420–33. [Google Scholar]

- Covington, Stephanie S. 2007. Women and the criminal justice system. Women’s Health Issues 17: 180–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covington, Stephanie S., and Janet L. Surrey. 1997. The relational model of women’s psychological development: Implications for substance abuse. In Gender and Alcohol: Individual and Social Perspectives. Piscataway: Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies, pp. 335–51. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, Modrowski, Shannon D. Chaplo, and Patricia Kerig. 2022. Advancing Our Understanding of the Risk Factors Associated with Crossover Youth in the Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice Systems: A Trauma-Informed Research Agenda. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 25: 283–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, Çiğdem Berber, and Hatice Odacı. 2020. Does child abuse have an impact on self-esteem, depression, anxiety and stress conditions of individuals? International Journal of Social Psychiatry 66: 171–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, Kathleen, and Meda Chesney-Lind. 1988. Feminism and criminology. Justice Quarterly 5: 497–538. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Janet T., and Meda Chesney-Lind. 2009. Discounting women: Context matters in risk and need assessment. Critical Criminology 17: 221–46. [Google Scholar]

- DeHart, Dana D. 2018. Women’s pathways to crime: A heuristic typology of offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior 45: 1461–82. [Google Scholar]

- DeHart, Dana D., and Shannon Lynch. 2021. Women’s and Girls’ Pathways Through the Criminal Legal System: Addressing Trauma, Mental Health, and Marginalization, 1st ed. San Diego: Cognella. [Google Scholar]

- DeHart, Dana D., Shannon Lynch, Joanne Belknap, Priscilla Dass-Brailsford, and Bonnie Green. 2014. Life history models of female offending. Psychology of Women Quarterly 38: 138–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, L. Mara. 1999. “One female prisoner is of more trouble than twenty males”: Women convicts in Illinois prisons, 1835–1896. Journal of Social History 32: 906–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereidooni, Fatemeh, Judith K. Daniels, Anne D. Krause-Utz, Muriel A. Hagenaars, Tom Smeets, Jenna Heins, Martin J. Dorahy, Arnold.A.P. van Emmerik, Peter J. de Jong, Steven Hoekstra, and et al. 2023. Childhood maltreatment and adulthood victimization: An evidence-based model. Journal of Psychiatric Research 167: 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelhor, David. 2008. Childhood Victimization: Violence, Crime, and Abuse in the Lives of Young People. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, David, Heather Turner, Anne Shattuck, Sherry Hamby, and Kristen Kracke. 2015. Children’s Exposure to Violence, Crime, and Abuse: An Update; Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and Centers for Disease Control. Available online: https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh176/files/pubs/248547.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Fischer, Judith L., and Lynda Spann. 1991. Measuring codependency. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 8: 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, Myron D., L. J. Woodward, L. J. Horwood, and D. M. Fergusson. 2010. Childhood exposure to sexual abuse and partnership outcomes at age 30. Psychological Medicine 40: 679–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaarder, Emily, Nancy Rodriguez, and Marjorie S. Zatz. 2004. Criers, liars, and manipulators: Probation officers’ view of girls. Justice Quarterly 21: 547–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsinger, Kristi, Joanne Belknap, and Jennifer L. Sutherland. 1999. Assessing the Gender Specific Program and Service Needs for Adolescent Females in the Juvenile Justice System; Columbus: State of Ohio’s Criminal Justice Services.

- Horwitz, Allan V., Cathy Spatz Widom, Julie McLaughlin, and Helene Raskin White. 2001. The Impact of Childhood Abuse and Neglect on Adult Mental Health: A Prospective Study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 42: 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, Dana Crowley, and Diana Dill. 1992. The Silencing the Self Scale: Schemas of intimacy associated with depression in women. Psychology of Women Quarterly 16: 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Melissa S., Meredith G.F. Worthen, Susan F. Sharp, and David A. McLeod. 2018. Life as she knows it: The effects of adverse childhood experiences on intimate partner violence among women prisoners. Child Abuse & Neglect 85: 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Hyunzee, Todd I. Herrenkohl, Martie L. Skinner, Jungeun Olivia Lee, J. Bart Klika, and Ashley N. Rousson. 2019. Gender Differences in Intimate Partner Violence: A Predictive Analysis of IPV by Child Abuse and Domestic Violence Exposure During Early Childhood. Violence Against Women 25: 903–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeble, Danielle. 2023. Probation and Parole in the United States, 2021; Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/ppus21.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Keen, Jaclyn, Mariah Cowell, Megan Foster, and Emily J. Salisbury. 2023. Mythologies of Working with Justice-Involved Women in Correctional Settings. In Perceptions fo Female Offenders. Edited by Brenda Russell and Celia Torres. 2 vols, Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig, Patricia K. 2018. Polyvictimization and Girls’ Involvement in the Juvenile Justice System: Investigating Gender-Differentiated Patterns of Risk, Recidivism, and Resilience. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 33: 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilpatrick, Dean G., Benjamin E. Saunders, and Daniel W. Smith. 2003. Youth Victimization: Prevalence and Implications; Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

- Koggel, Christine M., Ami Harbin, and Jennifer J. Llewellyn. 2022. Feminist relational theory. Journal of Global Ethics 18: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, Jennifer E., Jennifer Godwin, Robert J. McMahon, Max Crowley, Gregory S. Pettit, John E. Bates, John D. Coie, and Kenneth A. Dodge. 2021. Early Physical Abuse and Adult Outcomes. Pediatrics 147: e20200873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, Carly D., Jonathan G. Sandberg, James M. Harper, and Roy Bean. 2011. The Effects of Childhood Abuse on Relationship Quality: Gender Differences and Clinical Implications. Family Relations 60: 435–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Man-Kit, Mark T. Berg, Ronald L. Simons, and Steven R. H. Beach. 2023. Specifying the psychosocial pathways whereby child and adolescent adversity shape adult health outcomes. Psychological Medicine 53: 6027–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, Kylee, Alyssa Banford Witting, Jonathan G. Sandberg, and Roy Bean. 2020. We Shall Overcome: The Association Between Family of Origin Adversity, Coming to Terms, and Relationship Quality in African Americans. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal 42: 305–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, Gerard, and Alan Taylor. 1999. Avoidant/Ambivalent Attachment Style as a Mediator between Abusive Childhood Experiences and Adult Relationship Difficulties. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 40: 465–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillen, J Curtis, Bonnie T Zima, Lionel D Scott, Wendy F Auslander, Michelle R Munson, Marcia T Ollie, and Edward L. Spitznagel. 2005. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older youths in the foster care system. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 44: 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, Mumtaz Ali, Jun-Hwa Cheah, T. Ramayah, Hiram Ting, and Francis Chuah. 2018. Mediation analysis: Issues and recommendations. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling 2: i–ix. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, Nena, and Christine Grella. 2006. Childhood trauma and women’s health outcomes in a California prison population. American Journal of Public Health 96: 1842–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, Jean Baker. 1986. What Do We Mean by Relationships? Working Paper Series. Newark: Stone Center. [Google Scholar]

- Modrowski, Crosby A., and Patricia K. Kerig. 2019. Investigating the Association Between Posttraumatic Risky Behavior and Offending in Adolescents Involved in the Juvenile Justice System. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 48: 1952–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Christopher M., and Sharon A. Hoover. 1999. Measuring emotional abuse in dating relationships as a multifactorial construct. Violence and Victims 14: 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, Elise N., and Victoria L. Banyard. 2006. Social support: A mediator between child maltreatment and developmental outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 35: 612–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, André, José P. Santos, Pedro Sardinha, Jorge Cardoso, Catarina Ramos, and Telma Almeida. 2021. The impact of childhood abuse on adult self-esteem and emotional regulation. Annals of Medicine 53 Suppl. S1: S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Andrew F. Hayes. 2004. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers 36: 717–31. [Google Scholar]

- Radatz, Dana L., and Emily M. Wright. 2017. Does polyvictimization affect incarcerated and non-incarcerated adult women differently? An exploration into internalizing problems. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 32: 1379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenburg, Frances A., and John W. Fantuzzo. 1993. The measure of wife abuse: Steps toward the development of a comprehensive assessment technique. Journal of Family Violence 8: 203–28. [Google Scholar]

- Roehling, Patricia V., and Eva Gaumond. 1996. Reliability and validity of the Codependent Questionnaire. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 14: 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, Morris. 1979. Conceiving the Self. New Orleans: Robert E Krieger. [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury, Emily J., and Patricia Van Voorhis. 2009. Gendered pathways: A quantitative investigation of women probationers’ paths to incarceration. Criminal Justice and Behavior 36: 541–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, Emily J., and Patricia Van Voorhis. 2022. Correctional Counseling and Rehabilitation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury, Emily J., Patricia Van Voorhis, Emily Wright, and Ashley Bauman. 2009. Changing probation experiences for female offenders based on Women’s Needs and Risk Assessment Project Findings. Women, Girls, and Criminal Justice 10: 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Salokangas, Raimo K. R., Frauke Schultze-Lutter, Stefanie J. Schmidt, Henri Pesonen, Sinikka Luutonen, Paul Patterson, Heinrich Graf von Reventlow, Markus Heinimaa, Tiina From, Jarmo Hietala, and et al. 2020. Childhood physical abuse and emotional neglect are specifically associated with adult mental disorders. Journal of Mental Health 29: 376–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, Preeta, and Nena Messina. 2021. Trajectories of victimization to violence among incarcerated women. Health & Justice 9: 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, Magnus, and Arthur J. Lurigio. 2005. Probation officers’ views on supervising women probationers. Women & Criminal Justice 16: 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, April Chiung-Tao. 2009. Self-Esteem of Young Adults Experiencing Interparental Violence and Child Physical Maltreatment: Parental and Peer Relationships as Mediators. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 24: 770–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, Melanie F., and James A. Campbell. 1992. The Abusive Behavior Inventory: A measure of psychological and physical abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 7: 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherer, Mark, James E. Maddux, Blaise Mercandante, Steven Prentice-Dunn, Beth Jacobs, and Ronald W. Rogers. 1982. The Self-Efficacy Scale: Construction and validation. Psychological Reports 51: 663–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, Kristen W., Jennifer Sheridan, Daphne Kuo, and Molly Carnes. 2007. Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: Results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse & Neglect 31: 51530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stith, Sandra M., Karen H. Rosen, Kimberly A. Middleton, Amy L. Busch, Kirsten Lundeberg, and Russell P. Carlton. 2000. The Intergenerational Transmission of Spouse Abuse: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family 62: 640–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, David L. 2005. Finding our way: An introduction to path analysis. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50: 115–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardif-Williams, Christine Y., Masako Tanaka, Michael H. Boyle, and Harriet L. MacMillan. 2017. The Impact of Childhood Abuse and Current Mental Health on Young Adult Intimate Relationship Functioning. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 32: 3420–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Sentencing Project. 2022. Incarcerated Women and Girls. Available online: https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/incarcerated-women-and-girls/ (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- The University of Utah. 2025. Women’s Risk Needs Assessment: WRNA. Available online: https://socialwork.utah.edu/research/ucjc/wrna/index.php (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2023. Child Maltreatment 2021. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/report/child-maltreatment-2021 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Vaillancourt-Morel, Marie-Pier, Ève-Line Bussières, Marie-Chloé Nolin, and Marie-Ève Daspe. 2024. Partner Effects of Childhood Maltreatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse 25: 1150–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valerio, Paola, and Georgia Lepper. 2009. Sorrow, shame, and self-esteem: Perception of self and others in groups for women survivors of child sexual abuse. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy 23: 136–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Voorhis, Patricia, Emily M. Wright, Emily Salisbury, and Ashley Bauman. 2010. Women’s risk factors and their contributions to existing risk/needs assessment: The current status of a gender-responsive supplement. Criminal Justice and Behavior 37: 261–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Voorhis, Patricia, Emily Salisbury, Ashley Bauman, and Emily Wright. 2006. Gender Responsive Risk/Needs Assessment: Final Report Prepared for the Maui CARE Project; Washington, DC: National Institute of Corrections.

- Vidal, Maria Elena, and Jenny Petrak. 2007. Shame and adult sexual assault: A study with a group of female survivors recruited from an East London population. Sexual and Relationship Therapy 22: 159–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanamaker, Kayla A., and Shelley L. Brown. 2021. The Relationship Between Patterns of Change in Dynamic Risk and Strength Scores and Reoffending for Men on Community Supervision. Criminal Justice and Behavior 48: 1208–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, An Gie, and Sean Pearce. 2013. A beginner’s guide to factor analysis: Focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology 9: 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamir, Osnat. 2022. Childhood Maltreatment and Relationship Quality: A Review of Type of Abuse and Mediating and Protective Factors. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse 23: 1344–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Zhen. 2022. Jail Inmates in 2021—Statistical Tables; Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/jail-inmates-2021-statistical-tables (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Zhao, Xinshu, John G. Lynch, and Qimei Chen. 2010. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. Journal of Consumer Research 37: 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).