Abstract

Technology-facilitated abuse in relationships (TAR) is a relatively new form of intimate partner violence. Research exploring the impact of TAR on young people is limited, and while robust measures of TAR itself are emerging, measures of TAR impact lack evidence of validity. A mixed-methods approach was used to establish preliminary face and content validity for the measurement of TAR impact. Youth discussion groups (n = 38) revealed that (1) distress is favored over upset as a preferred measure of TAR impact, and (2) fear is an appropriate impact measure for some TAR behaviors. In an online survey, frontline practitioners (n = 171) perceived and subsequently rated a total of 54 TAR behaviors in the upper half of the severity range on fear and distress, with 6 behaviors ranking among each of the top 10 most fear- and distress-inducing behaviors. These findings provide evidence of both face and content validity for the use of fear and distress measures when seeking to understand the impact of TAR. Scholars, practitioners, and educators alike can use this evidence to enhance the validity of investigations into TAR and its impact, to support victims of TAR, and to improve TAR education among youth.

1. Introduction

Technology-facilitated abuse in relationships (TAR) has emerged as a relatively new but highly prevalent form of intimate partner violence (Aghtaie et al. 2018; Flynn et al. 2023; Mumford et al. 2023; Vogler et al. 2023). It is a widespread problem among youth and involves using technology to perpetrate abuse in intimate relationships (Borrajo et al. 2015b; Brown and Hegarty 2021; Reed et al. 2016; Smith-Darden et al. 2017). In particular, the spaceless 24/7 nature of digital devices enables a TAR perpetrator to generate a unique form of omnipresence and coercive control over their target (Fiolet et al. 2021; Harris and Woodlock 2022; Powell and Henry 2016). The use of technology in this way can transcend fixed, physical, or geographical borders and boundaries (Dragiewicz et al. 2018), extending the duration, intensity, and invasiveness of the abuse (Woodlock et al. 2019). These effects can be compounded when a perpetrator enlists others who knowingly or unknowingly help perpetrate the abuse (Dragiewicz et al. 2018). These unique features of TAR render it a distinct form of intimate partner violence that warrants its own investigation.

Theoretically, TAR is grounded in the understanding that intimate partner violence comprises a pattern of abusive, coercive, and controlling behaviors that occur in the context of familial, cultural, and structural gender inequality (Dobash and Dobash 1979). Stark (2007) emphasizes the pattern of both physical and non-physical abuse and control that are central to understanding the many different forms of intimate partner violence while Anderson (2008) highlights the potential for high levels of control even in the absence of physical violence. Thus, TAR, as a non-physical form of abuse, ought to be considered in the broader context of intimate partner violence and coercive control.

Scholars have yet to agree on the range of behaviors constituting TAR, and ambiguity exists around the terms and definitions used to delineate the phenomenon (Rocha-Silva et al. 2021; Rogers et al. 2022). For the purposes of the current paper, we define TAR as “… a patterned (or single) use of abusive or controlling behaviors in intimate relationships, enacted via digital mediums” (Brown 2021, p. 10). Scholars are also yet to ascertain the gendered influences on how TAR is perceived and experienced (Brown and Hegarty 2018; Caridade et al. 2019) and to fully understand the impact of TAR behaviors on victims (Afrouz 2023; Brown and Hegarty 2018; Dragiewicz et al. 2019; Rogers et al. 2022).

Technology-facilitated abuse in relationships is thought to engender a range of negative consequences for victims (e.g., Brown et al. 2020, 2021; Dragiewicz et al. 2019; Ortega-Barón et al. 2020; Stonard 2019, 2020). Young women may be more adversely affected than young men (Barter et al. 2017; Brown et al. 2020; Henry et al. 2019; Reed et al. 2017, 2020). However, studies to date provide varied and somewhat unrefined approaches to the measurement of TAR impact (e.g., Barter et al. 2017; Brown and Hegarty 2021; Duerksen and Woodin 2019; Reed et al. 2017). For example, TAR impact was measured via anticipated impacts (Bennett et al. 2011; Reed et al. 2016), degree of upset (Reed et al. 2017), fear of partner, depression, and perceived stress (Duerksen and Woodin 2019). Participants have also been asked to select from a range of negative and affirmative feelings, or no effect, to measure TAR impact (Barter et al. 2017). More recently, Flynn et al. (2023) measured impact via the extent to which participants felt controlled, humiliated, depressed, or afraid for their safety (among other more neutral measures) and collectively referred to these as harmful emotional impacts. Boateng et al. (2018) identify best practices for developing and validating health, social, and behavioral scales as including three phases: generating scale items and assessing their content validity, constructing the scale through pre-testing and administering the scale, and evaluating the scale’s reliability and validity. The abovementioned studies neglected to engage in these best practice steps and, thus, did not establish evidence of validity for their respective TAR impact measures and may not have generated valid findings or measured what was intended (Groth-Marnat 2009).

A crucial factor in the construction of measurement tools, validity indicates the degree to which a tool measures what it claims to measure (Groth-Marnat 2009). Multiple forms of validity exist, including face, content, criterion, and construct validity (Groth-Marnat 2009). In particular, face validity ensures the measure makes sense to, and exhibits test rapport with, the people who will take the test. It is most often generated with sample test users and improves the acceptability, relevance, and quality of the measure and its related research (Connell et al. 2018; Groth-Marnat 2009; Zamanzadeh et al. 2014). A lack of face validity can be associated with inaccurate and dishonest responses to survey questions (Connell et al. 2018). Content validity ensures the elements of a measurement instrument are relevant to and representative of the construct under question and is most often generated via content experts such as professionals with topic research interests or professional experience in the field (Almanasreh et al. 2019; Devellis 2017; Zamanzadeh et al. 2014). A lack of content validity can prevent the attainment of measurement reliability and can produce inconsistent, unpredictable, and inaccurate results (Groth-Marnat 2009).

The measurement of partner abuse is replete with complexities that challenge scholars’ ability to establish the accuracy of measurement (Follingstad and Rogers 2013). Self-report partner violence assessment tools that study the frequency of behavior alone, for example, can lead to the erroneous reporting of partner abuse and TAR (Brown et al. 2021; Hamby 2016). Additionally, the subjectivity of people’s perceptions of events and the nuanced, interpersonal, and often hidden nature of partner abuse can lead to inaccurate reporting (Follingstad and Rogers 2013). Further, the context in which abusive behaviors occur also holds relevance (Borrajo et al. 2015a, 2015b; Follingstad and Rogers 2013).

Undoubtedly, measures that fail to account in some way for the contextual nature of TAR will produce invalid findings (Brown and Hegarty 2018). Some scholars argue that the unique psychological significance of the behavior to the individual enduring it, particularly in the context of non-physical forms of relationship abuse, informs whether the behavior is experienced as abusive or not and is, therefore, central to understanding TAR and its impact (Brown and Hegarty 2018; Brown et al. 2021; Dragiewicz et al. 2019; Henry et al. 2019; Hinson et al. 2019). Accounting for impact when measuring TAR may also help scholars establish whether behaviors constitute abuse (rather than just hurt feelings or other aggressive but more normative behaviors) and, thus, help to establish measurement validity and provide a more accurate form of measurement (Follingstad and Rogers 2013). We argue the importance of measuring the impact of TAR on the basis that some TAR behaviors are highly contextual (Brown and Hegarty 2018), and others, such as the live digital monitoring of a partner’s whereabouts, are often normalized among younger people (Aghtaie et al. 2018; Brown and Hegarty 2018; Harris and Woodlock 2018; Stonard 2020). Furthermore, we argue that valid measurement of the impact of TAR is essential to scholars’ understanding of this relatively new phenomenon.

Moreover, youth identified technology-facilitated behaviors involving social interaction, such as threats, public and private insults, non-consensual sending/sharing of nude photos, and sexual rumors, among their worst dating experiences (Reed et al. 2020). Each possessing a social quality, we contend these behaviors can lead to psychosocial stress—a form of stress resulting from situations of social threat or social interaction with others (Kogler et al. 2015). Systematic reviews and longitudinal studies link psychosocial stress to varying forms of ill-health, including cardiovascular disease, mental illness, and changes in other physiological markers that contribute to disease (e.g., Calcia et al. 2016; Chiang et al. 2019; Fishta and Backé 2015; Mathur et al. 2016; Pruessner et al. 2008; Thoits 2010; Turecki and Meaney 2016; Wirtz and von Känel 2017). This further strengthens the argument that the measurement of TAR should include the measurement of constituent forms of psychosocial stress as indicators of the impact, seriousness, and abusiveness of TAR behaviors.

We recently published the development and preliminary validation of the new TAR Scale (Brown and Hegarty 2021). The development of the scale utilized best-practice scale development procedures for the scale’s behavioral items (Brown and Hegarty 2021). This included factor analysis (a form of construct validity) and consultation with topic experts and youth to establish content and face validity, respectively (Boateng et al. 2018; Carpernter 2018; Devellis 2017). The measurement of fear and distress were incorporated into the TAR Scale as indicators of TAR impact (Brown and Hegarty 2021), but the validation of these was not included in the development publication. Seeking to address earlier mentioned and well-documented measurement challenges in the field of partner abuse (e.g., Follingstad and Rogers 2013; Hamby 2016; Jouriles and Kamata 2016; Messing et al. 2020; Walby et al. 2017), the current paper expressly addresses the question of how face and content validity for the measurement of TAR’s emotional impact can be established. Without such validity evidence, a measurement of the TAR phenomenon is likely to be inaccurate and render future research and the subsequent provision of support to youth who experience the harmful effects of TAR at risk of compromise.

Accordingly, the current paper describes the process used to consult youth and experts to establish face and content validity for the TAR impact measures of the TAR Scale, is supplementary to the previously published validity evidence for the TAR Scale behavioral items (Brown and Hegarty 2021), and completes the provision of validity evidence for the entire scale. The aim of the current paper is, therefore, to establish face and content validity evidence of fear and distress as relevant and theoretically appropriate measures of youth TAR impact.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper reports two studies (see Figure 1). The first study aimed to establish preliminary face validity by exploring youths’ preferred emotion words for the measurement of the emotional impact of TAR. The second study aimed to establish preliminary content validity by surveying domestic violence practitioners’ perceptions of the extent to which the words proposed by youth in study 1 (distress and fear) related to a selection of TAR behaviors. The second study also explored practitioner perspectives on how distress- and fear-inducing a range of TAR behaviors was perceived to be; this was considered a potential indicator of harm.

Figure 1.

Studies designed to establish face and content validity for measuring impact of technology-facilitated abuse in relationships.

2.1. Study 1—Youth Qualitative Study

2.1.1. Participants

Thirty-eight youths (23 women, 15 men) aged 16 to 24 years (average age 18.4) were recruited via the university student portal, community youth organizations, and Facebook. Each participant received an AUD 30 gift voucher for participation in a discussion group. Of the participants, 18 women and 11 men then provided feedback on a survey about harmful technology use and its impact, receiving another AUD 30 gift voucher. Ethics approval for the study was granted by the university research ethics committee.

2.1.2. Procedures

Data was collected via semi-structured discussion groups (Liamputtong 2011). Totaling four and each of 60 min duration, the two all-men and two all-women discussion groups were conducted by two experienced facilitators in university or public library rooms. Informed consent was obtained from all participants following which definitions were provided. Dating Relationships were defined as “sexual or non-sexual, casual or serious, short-term or long-term, straight, gay, monogamous or open”. Technology was defined as “any form of modern-day technology/device… such as smartphones, tablets laptops, notepads, computers, internet, social media, GPS devices, software, apps etc.”. Harmful Behaviors were defined as “including (but not limited to) behaviors that are psychologically, emotionally, physically, or sexually harmful”.

When undertaking qualitative research to inform the development of a measure, the discussion guide should begin with broad, open-ended questions and proceed to a more detailed exploration of participant responses and, finally, to an exploration of the researcher’s additional questions of interest (Brod et al. 2009). Accordingly, with the use of a topic guide, participants were asked to identify and then write ‘emotion’ words they would use to describe the impact of harmful technology behaviors in the context of dating relationships. The facilitators displayed these on a whiteboard and promoted discussion using verbal prompts. Participants were then prompted to discuss the words upset, distress, and fear as generic measures of the impact of harmful technology use in dating relationships. Following this, participants were invited to privately write down the two words they considered most suitable for measuring the impact of the behaviors. These rankings remained anonymous and were collected by the researchers. The consultation of youth in the current study was undertaken to form preliminary evidence of face validity for the measurement of TAR impact.

2.1.3. Data Analysis

The group discussions were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using an inductive approach (Braun and Clarke 2006; Thomas 2006). A coding structure was developed through multiple readings of the data, reflexive journaling, and memo writing. These codes were then applied to the data to identify emerging themes, followed by an iterative review and cross-checking process to confirm the accuracy and consistency of the themes. A simple count method was used to analyze participants’ preferred words for measuring emotional impact and rankings on the combination of distress and fear. To maintain anonymity during analysis and reporting, each participant was designated an individual identifier comprising their gender and a unique number.

2.2. Study 2—Practitioner Quantitative Study

2.2.1. Participants

Domestic violence frontline practitioners (1082) from Australia were invited by email to participate in an online survey, of whom 325 agreed (30%). The responses of 47.5% of participants (154) were removed due to incomplete surveys, leaving 171 participants with a mean age of 44 years. Participants were contacted based on their membership in WESNET (an Australian organization whose vision is to promote the prevention of domestic violence) or participation in the Safe Connections Smartphone program (an Australian program providing smartphones, pre-paid credit, and education about safe technology use to women impacted by domestic violence). Surveying frontline practitioners enabled us to tap into the collective knowledge, insights, and expertise of professionals who have undertaken a multitude of in-depth interactions with victims of domestic violence, including TAR, aiding consistency with the perspective, experience, and words of the target population (Brod et al. 2009). Thus, the current sample of content experts was chosen to assist with the generation of evidence of content validity for the use of the words distress and fear in the measurement of TAR impact.

Ninety-eight percent of respondents identified as women, and two percent identified as men. Participants represented all states and territories of Australia as follows: New South Wales 35%, Victoria 19%, Queensland 19%, Western Australia 9%, South Australia 8%, Northern Territory 5%, Tasmania 3%, and Australia Capital Territory 1%. Eighty-five percent of participants specifically provided domestic/family violence services, and the remaining provided a range of support services, including for sexual assault, homelessness, drug and alcohol, child protection, crisis accommodation, and counseling. Thirty-four percent of participants were working as frontline practitioners for more than 10 years, 16% for 6 to 9 years, 25% for 3 to 5 years, and 25% for less than 2 years.

2.2.2. Procedures

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the university research ethics committee, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. In their capacity as frontline practitioners, participants were invited to rate 54 TAR behaviors (see Appendix A) on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 10 (Extremely) based on the extent to which they thought each behavior to be (a) distress-inducing and (b) fear-inducing. This enabled us to establish the extent to which experts thought the emotional impacts of distress and fear were relevant to and theoretically representative of the impact of a selection of TAR behaviors and also served to reveal practitioner perspectives on the impact of TAR.

2.2.3. Data Analysis

Analysis was completed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 27). No patterns were found among missing variables (Tabachnick and Fidell 2013). The distress and fear variables were treated as continuous variables, and missing data, which were <5% on each variable, were replaced with their respective series means (Tabachnick and Fidell 2013). Overall means were then calculated for each TAR behavior on both the distress and fear variables, and the behaviors were ranked in order of most to least distress-inducing and most to least fear-inducing.

3. Results

3.1. Study 1—Youth Qualitative Study

When asked to nominate words that would describe the impact of harmful technology experiences, female participants nominated words such as fear, betrayal, anxiety, distress, self-doubt, and isolation. Young men initially nominated words such as embarrassment, shame, loss of self-esteem, irritation, annoyance, and anger. Upon reflection and after discussion among the group, both men and women privately nominated distress and fear as preferred words for measuring the impact of harmful technology behaviors. The following themes emerged: (1) youth favored distress over upset for measuring the impact of TAR behaviors, and (2) fear is relevant for measuring the impact of selected TAR behaviors.

Distress and fear were the two words most frequently preferred by participants as generic measures of the impact of harmful technology behaviors in dating relationships. In the discussion groups, totaling 38 participants, distress was privately nominated as the preferred top word by 20 participants (12 women, 8 men), and fear was nominated by 7 participants (5 women, 2 men).

- Youth favored distress over upset for measuring the impact of TAR behaviors.

Participants expressed a preference for the use of the word distress rather than upset.

“Yeah, I think ‘distress’ would cover traumatized; anxiety. But upset doesn’t”.F6

“I don’t think [upset’s] quite specific enough…”F18

“… I think distress works as a catch-all term… probably works for all of the examples that we’ve said”.M10

“I think upset might be a bit too broad”.F8

“… ‘distress’ sounds like a grander, more serious word”.M9

Female participants identified distress as encompassing future-oriented concerns, including anxiety and uncertainty about consequences.

“I think distress covers some words that are… future based, because distress comes with that kind of emotion of you’re not sure what’s going to happen”.F4

“I think [distress] would be a better fit, because when I hear distress I think more anxiety, more… like an ongoing… I think it’s a more specific mix of emotion than upset”.F8

“… [distress] relates a lot more to anxious… anxiety… panic, you’re sweating… and you can’t think straight… your heart’s beating fast…”.F20

There was also a view that upset did not adequately represent the severity of the impact of harmful technology use.

“Upset’s just not strong enough”.F1

“[Upset] weakens how bad this is”.F2

“Upset’s just anything that’s not positive, isn’t it?…it’s a very broad term”.M13

Overall, participants perceived the strength and seriousness of the word distress as more accurately describing the impact of the behaviors than those of upset.

- Fear is relevant for measuring the impact of selected TAR behaviors.

Participants felt that fear was relevant to some behaviors but not all and possibly to those that could be considered more harmful.

“I think for example fear… it won’t go with all of them, but some of them… I reckon it’s definitely a top thing…”.F5

“… fear… you might need to address the situation a little bit sooner, because it might be personally endangering”.M6

“… the stalking will lead to fear”.M4

“You might not be afraid in every situation”.F14

When asked about which behaviors would make people feel fearful, female participants suggested blackmail, abuse, and “Controlling behavior through maybe demanding your password to your account, like your Facebook account…” F8.

“Fear… also fear of people finding out… I guess that goes back into the blackmailing, sort of thing. Like holding maybe a conversation or explicit photo or something as ransom, to say, ‘I’ve got you.’”F8

Aside from single-word responses nominating “stalking” and “GPS tracking” as eliciting fear, male participants did not voluntarily describe the experience of fear in relation to any other harmful technology behaviors during the discussion.

In summary, the above themes suggest that youth favored distress over upset for measuring the impact of TAR and that fear is also seen as a suitable measure of TAR impact, particularly for behaviors that may be considered more harmful.

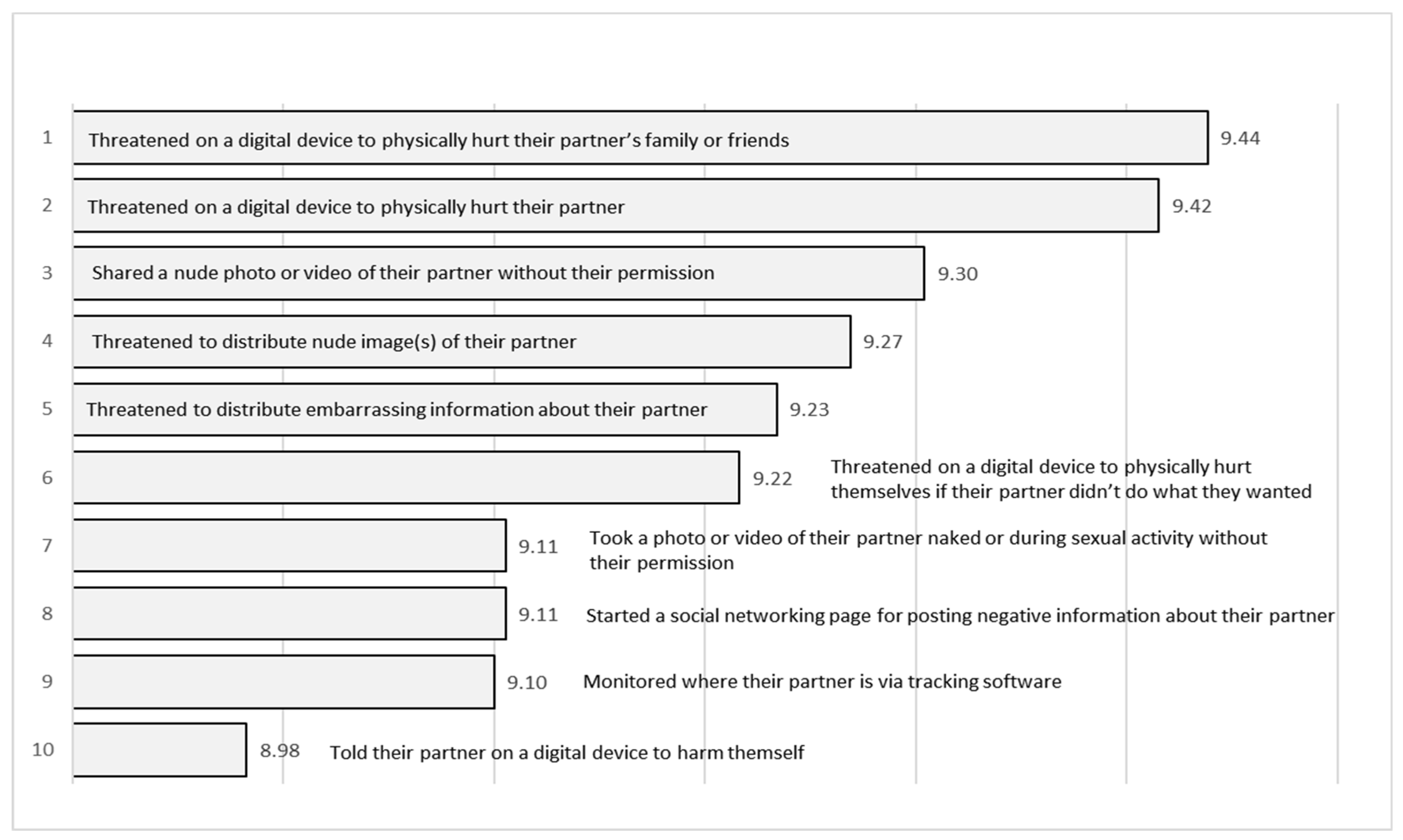

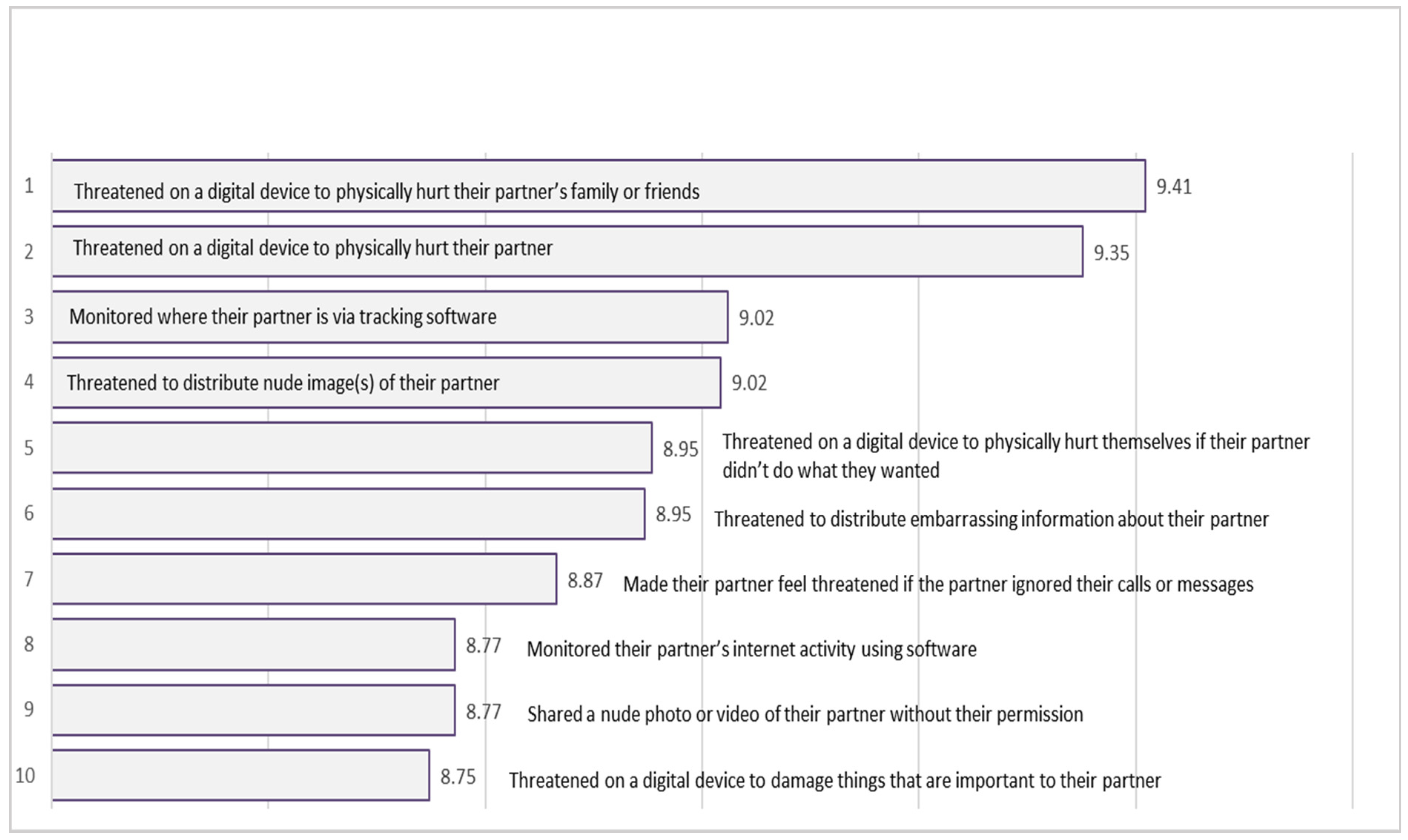

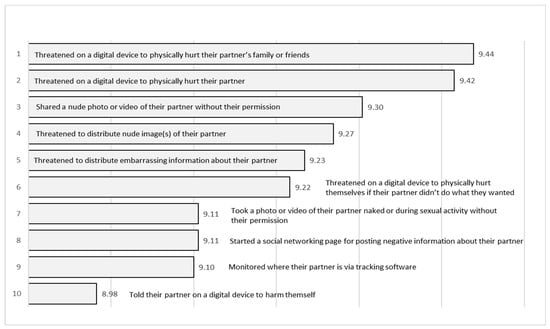

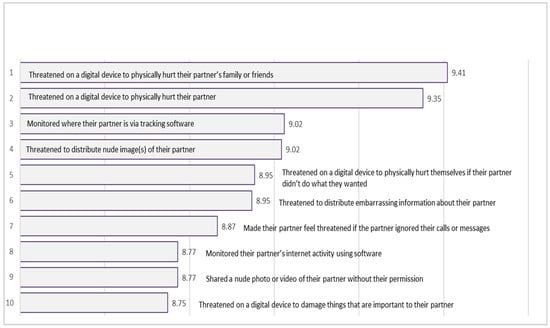

3.2. Study 2—Practitioner Quantitative Study

Practitioners’ mean ratings on the extent to which they thought each of the 54 TAR behaviors were distress- and fear-inducing were all in the upper half of the possible range of zero to 10 (see Appendix A). The mean ratings ranged from 9.44 (distress-inducing) and 9.41 (fear-inducing) for threatened on a digital device to physically hurt their partner’s family or friends) to 7.56 (distress-inducing) and 6.65 (fear-inducing) for shared an embarrassing non-sexual photo or video of their partner on a digital device. Behaviors rated in the top 10 most distress-inducing (see Figure 2) included five behaviors involving threatening behavior, three behaviors involving nudity or sexual acts, one behavior involving monitoring of a partner, and four behaviors containing references to physical harm. Behaviors rated in the top 10 most fear-inducing (see Figure 3) included seven behaviors involving threatening behavior, two behaviors involving nudity or sexual acts, two behaviors involving the monitoring of a partner, and four behaviors containing references to physical harm. Six items appeared in both top 10 lists (see Table 1). These included four behaviors involving threats, two behaviors involving nudity or sexual acts, one behavior involving the monitoring of a partner, and three behaviors containing references to physical harm.

Figure 2.

Top 10 TAR behaviors (ranked by mean) that experts perceive as most distress-inducing.

Figure 3.

Top 10 TAR behaviors (ranked by mean) that experts perceive as most fear-inducing.

Table 1.

Behaviors appearing in top 10 most distress- and fear-inducing and their rankings.

4. Discussion

This paper aimed to demonstrate face and content validity evidence for the measurement of youth TAR impact by exploring (1) youths’ perspectives on which emotion words should be used to measure the emotional impact of TAR and (2) practitioners’ perspectives on the emotional impact of TAR across a range of TAR behaviors. Youth identified distress (as preferable to upset) and fear as their preferred words for measuring the emotional impact of TAR. Frontline practitioners then reported the extent to which they thought individual TAR behaviors were distress- and fear-inducing. These findings bring new insights into understanding the impact of TAR and how it can be measured.

While research into the effects of TAR is limited, our finding of the relevance of fear to the impact of TAR aligns with women’s reports of fear resulting from TAR victimization (Brown et al. 2020, 2021; Dragiewicz et al. 2019; Duerksen and Woodin 2019; Flynn et al. 2023; Henry et al. 2019). A study among young adults found that experiencing TAR increased women’s, but not men’s, fear of their partner (Duerksen and Woodin 2019), while practitioners perceive that TAR behaviors create a constant state and omnipresence of fear for female victims (Dragiewicz et al. 2019; Fiolet et al. 2021; Rogers et al. 2022; Woodlock et al. 2019). Youth and adult victims of image-based sexual abuse (a subset of TAR) also reported being ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ fearful for their safety as a result of the behaviors, with women more likely to feel fearful than men (Henry et al. 2019), although men may also experience fear as a result of TAR victimization (Flynn et al. 2023). Relatedly, the measurement of “fear of partner” was identified as a useful short-form method for identifying the presence of partner abuse among women (Signorelli et al. 2020). While the gendered nature of TAR impact is yet to be fully understood, findings of women experiencing fear as a result of TAR echo findings in the adjacent fields of cyberstalking (Davies et al. 2016; Worsley et al. 2017), online harassment (e.g., Davies et al. 2016; Lindsay et al. 2016; Pereira et al. 2016), cyberbullying (e.g., Hoff and Mitchell 2009; Randa 2013; Yu 2017), in-person dating violence (e.g., Barter et al. 2017; Burton et al. 2013; Conroy 2016; Reidy et al. 2016), and non-physical aggression in relationships (O’Leary et al. 2013).

Distress was also reported by victims of TAR. Young and adult women (Bennett et al. 2011; Brown et al. 2021; Henry et al. 2019; Reed et al. 2017) reported greater levels of distress resulting from TAR behaviors than their male counterparts, with some adult women victims of TAR reporting ‘extremely high’ levels of distress (Dragiewicz et al. 2019). Young women have also more often reported high levels of distress than young men on selected TAR behaviors such as threats or the non-consensual distribution of nude images, being told to harm oneself, and being forced to remove contacts from one’s digital device (Brown et al. 2021). Another study found victims of image-based sexual abuse were almost twice as likely as non-victims to report high levels of distress, where threats to distribute sexual images specifically were associated with victims’ highest distress levels (Henry et al. 2019). Similarly, 93% of (mostly female) participants whose images were distributed online non-consensually experienced significant emotional distress (Cyber Civil Rights Initiative 2014). These findings likely bear similarity to reports of distress associated with offline relationship abuse, particularly in relation to non-physical forms of abuse (Arriaga and Schkeryantz 2015; Evans et al. 2014).

Youths’ preference for using distress over upset is important in light of the varying ways in which scholars have measured this construct. For example, studies elicited self-reported ‘upset’ to measure distress among young victims of TAR (Reed et al. 2017), female victims of domestic violence (Evans et al. 2014; Hegarty et al. 1999), and in relation to sexting coercion (Drouin et al. 2015). In contrast, the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (Kessler et al. 2002) was used to measure distress among victims of image-based sexual abuse (Henry et al. 2019) and TAR more broadly among adult Australians (Flynn et al. 2023). Research investigating the relationship between the distress and upset constructs is limited; however, Eisenberg et al. (1989) reported that children (and adults, to a lesser extent) experience distress and upset as two different constructs, while other scholars view upset as a subset of distress (e.g., Batson et al. 1983; Cialdini et al. 1987; Mitchell et al. 2012; Sze et al. 2012). Our findings suggest that young people perceive distress and upset as different constructs and prefer distress for the measurement of the emotional impact of TAR behaviors. Youths’ identification of distress and fear as applicable words for describing the impact of TAR behaviors establish face validity for its use in the measurement of TAR impact.

To establish content validity, frontline practitioners reported a range of distress and fear ratings across the 54 TAR behaviors, with all mean ratings falling in the upper half of the possible range. This reveals frontline practitioners’ perceptions that the words distress and fear are relevant to and theoretically representative of the impact of TAR, providing content validity for the use of distress and fear in the measurement of TAR impact. Of note, some behaviors were perceived by practitioners as more distress- and fear-inducing than others. For example, threats to hurt a partner, a partner’s family or friends, or themselves ranked in both the top ten most distress- and fear-inducing behaviors. These findings accord with other reports of high levels of fear and distress being associated with threats of physical harm to an intimate partner (Brown et al. 2021; Cercone et al. 2005; Olson et al. 2008). Concerningly, the findings may also mirror meta-analysis reports of threatening behavior (Matias et al. 2020), including threats to harm a partner (Spencer and Stith 2020) as risk factors for partner homicide.

Also, in practitioners’ top ten most distress- and fear-inducing behaviors was the non-consensual distribution of, or threats to distribute, nude images, a finding consistent with other studies reporting high levels of victim distress and fear resulting from these behaviors (Cyber Civil Rights Initiative 2014; Henry and Powell 2016; Henry et al. 2019; Office of the eSafety Commissioner 2017). Digital tracking of a partner was the final behavior ranked in the top ten most distress- and fear-inducing behaviors, mirroring victim reports of distress and fear from stalking (Diette et al. 2014), technology-facilitated surveillance (Dragiewicz et al. 2019), and technology-facilitated monitoring (Woodlock et al. 2019). Such fear may be linked to perpetrator omnipresence and inescapability engendered by TAR (Dragiewicz et al. 2019; Flynn et al. 2023; Woodlock et al. 2019) and highly warranted in light of cyberstalking’s association with partner homicide (Todd et al. 2020). The current findings suggest that some TAR behaviors, including those rated by practitioners in the top ten most distress- and fear-inducing in the current study, may have extremely serious consequences for victims.

Further signaling the seriousness of TAR, fear and distress are constituent forms of psychosocial stress (Duerksen and Woodin 2019; Ebesutani et al. 2011; Waters et al. 2014)—stress resulting from situations of social threat or social interaction with others (Kogler et al. 2015). By its very nature, TAR involves social interaction and, often, social threats (Brown and Hegarty 2021; Reed et al. 2016). Fear and distress resulting from a victim’s experience of TAR may, therefore, indicate the presence of serious harm and the potential for subsequent disease or other forms of ill health. In the current paper, youths’ and practitioners’ endorsement of fear and distress as relevant to and theoretically representative of the impact of TAR suggest that these particular psychosocial, emotional impacts—fear and distress—exhibit validity in the measurement of TAR.

The two studies presented in this paper exhibit limitations. Firstly, the qualitative data represent convenience samples from locations where the discussion groups were conducted and participants were of binary gender and mostly referred to heterosexual relationships; thus, a diverse range of views may not have been achieved, and the findings may not be generalizable to a more diverse population. Future research should engage a more diverse and representative sample of youth to achieve a broader, more inclusive range of views. Secondly, only 30% of frontline practitioners responded to the survey invitation, 98% of whom were female and 47% of whom provided insufficient data. The responses may, therefore, be unrepresentative of the broader frontline practitioner perspective, the specifics of which were unable to be determined from the descriptive data obtained from practitioners. In future research, the collection of additional descriptive data from practitioners may assist in determining sample bias associated with lower response rates or partial responses. Further, it is possible that frontline practitioner perceptions of some TAR behaviors, particularly the non-consensual sharing of nude images, may have been influenced by the saliency of “revenge porn” media coverage (Henry et al. 2019) during the period the study took place. A repeat survey after a period of minimal relevant media coverage may overcome this potential bias. Thirdly, when young men were initially asked which emotion words they would use to describe the impact of TAR, they nominated words such as embarrassment, shame, and anger; however, after group discussion about fear, distress, and upset, many of the young men privately nominated fear and distress. The reasons for this are speculative, and further qualitative research is needed to obtain a more nuanced understanding of young men’s perceptions and experiences of the impact of TAR. Finally, it should be noted that the content validity evidence in the current study is preliminary in nature and that rigorous assessment of content validity as a psychometric property can only be undertaken quantitatively (Brod et al. 2009).

In conclusion, this research identifies distress and fear as youths’ two most preferred words for measuring the impact of TAR behaviors, providing face validity for their use in the measurement of TAR impact. The frontline practitioner ratings support that distress and fear are relevant to and theoretically representative of the victim impact of TAR, providing preliminary content validity for their use in the measurement of TAR impact. Practitioner perceptions suggest that some TAR behaviors may be more distress- and/or fear-inducing than others, strengthening the view that some behaviors may be more harmful than others. Collectively, our findings support the argument for measuring TAR impact and provide validity evidence for the use of distress and fear for its measurement. The inclusion of distress and fear measures in TAR research will furnish a more accurate understanding of the TAR phenomenon and the psychological significance of TAR behaviors to victims. It may also provide a path through which the harmfulness and/or abusiveness of specific TAR behaviors can be established, enabling practitioners and policymakers to develop more targeted and effective approaches for responding to TAR risks, supporting TAR victims, and educating youth about this new, serious, and highly prevalent phenomenon.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B. and K.H.; Methodology, C.B. and K.H.; Validation C.B. and K.H.; Formal Analysis, C.B.; Investigation, C.B. and K.H.; Resources, C.B.; Data Curation, C.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.B.; Writing—Review & Editing, C.B. and K.H.; Visualization, C.B.; Supervision, K.H.; Project Administration, C.B.; Funding Acquisition, C.B. and K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Study 1 was funded via a small grant from the Department of General Practice, University of Melbourne.

Institutional Review Board Statement

These studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee, University of Melbourne (#1443159, #1443159, 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in these studies.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in these studies are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy issues.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the youth and practitioners who gave their time to participate in this research, and to Karen Bentley, from WESNET Australia, for facilitating recruitment of the practitioners who participated in Study 2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Means and Standard Deviations for Practitioner’s Ratings on The Extent to Which They Perceived 54 Technology-facilitated Abuse in Relationships Behaviors as Distress- and Fear-inducing.

| Behavior * | Distress | Fear | ||

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Threatened on a digital device to physically hurt their partner’s family or friends | 9.44 | 1.25 | 9.41 | 1.28 |

| Threatened on a digital device to physically hurt their partner | 9.42 | 1.38 | 9.35 | 1.40 |

| Shared a nude photo or video of their partner without their permission | 9.30 | 1.59 | 8.77 | 1.89 |

| Threatened to distribute nude image(s) of their partner | 9.27 | 1.62 | 9.02 | 1.77 |

| Threatened to distribute embarrassing information about their partner | 9.23 | 1.48 | 8.95 | 1.66 |

| Threatened on a digital device to physically hurt themselves if their partner didn’t do what they wanted | 9.22 | 1.50 | 8.95 | 1.70 |

| Took a photo or video of their partner naked or during sexual activity without their permission | 9.11 | 1.73 | 8.67 | 1.94 |

| Started a social networking page for posting negative information about their partner | 9.11 | 1.65 | 8.75 | 1.87 |

| Monitored where their partner is via tracking software | 9.10 | 1.68 | 9.02 | 1.76 |

| Told their partner on a digital device to harm themself | 8.98 | 1.73 | 8.63 | 1.96 |

| Pressured their partner on a digital device to engage in sexual acts | 8.94 | 1.86 | 8.52 | 2.16 |

| Threatened on a digital device to damage things that are important to their partner | 8.93 | 1.56 | 8.75 | 1.70 |

| Made their partner feel threatened if the partner ignored their calls or messages | 8.92 | 1.60 | 8.87 | 1.61 |

| Edited a photo or video of their partner in an offensive manner and sent it to them | 8.92 | 1.76 | 8.47 | 2.03 |

| Pressured their partner to engage in sexual activity via live video | 8.90 | 1.99 | 8.57 | 2.30 |

| Taken a video or photo of their partner against their wishes | 8.88 | 1.76 | 8.65 | 1.94 |

| Publicly declared their partner’s sexuality via a digital device without their permission | 8.86 | 1.89 | 8.18 | 2.23 |

| Threatened on a digital device to emotionally hurt their partner | 8.85 | 1.75 | 8.61 | 2.00 |

| Monitored their partner’s internet activity using software | 8.85 | 1.62 | 8.77 | 1.79 |

| Arrived uninvited when their partner has published their location online making the partner feel uncomfortable | 8.81 | 1.65 | 8.68 | 1.76 |

| Pressured their partner to send nude image(s) of themself | 8.78 | 1.87 | 8.39 | 2.20 |

| Sent their partner threatening messages on a digital device | 8.73 | 1.85 | 8.64 | 1.73 |

| Used a digital device to damage their partner’s friendship with another person | 8.65 | 1.72 | 7.95 | 2.11 |

| Signed their partner onto a pornography site without their permission | 8.61 | 2.05 | 8.02 | 2.34 |

| Prevented their partner from using their digital device (against their will) | 8.61 | 1.78 | 8.26 | 1.96 |

| Monitored their partner’s activity by insisting they answer their phone calls and/or messages | 8.61 | 1.69 | 8.45 | 1.76 |

| Pressured their partner on a digital device to send sexually explicit messages | 8.56 | 1.98 | 8.05 | 2.35 |

| Encouraged others to post negative things about their partner | 8.54 | 1.88 | 7.79 | 2.16 |

| Shared private information about their partner on a digital device without their permission | 8.52 | 1.94 | 7.65 | 2.41 |

| Checked to see who their partner was communicating with on their digital device, in a way that made the partner feel uncomfortable | 8.51 | 1.78 | 8.02 | 2.07 |

| Pressured their partner to engage in phone sex | 8.44 | 2.11 | 7.99 | 2.40 |

| Shared their partner’s private conversation on a digital device without their permission | 8.42 | 2.00 | 7.59 | 2.40 |

| Edited a photo or video of their partner in an offensive manner and shared it with others on a digital device | 8.41 | 2.03 | 7.71 | 2.31 |

| Pressured their partner on a digital device to discuss sexual issues | 8.41 | 2.02 | 7.81 | 2.39 |

| Contacted their partner via a digital device to check up on them in a way that made them feel uncomfortable | 8.41 | 1.82 | 8.18 | 2.06 |

| Made their partner disclose to them digital conversation(s) they’ve had with another person(s) | 8.39 | 1.87 | 7.92 | 2.10 |

| Posted negative comments about their partner | 8.39 | 1.79 | 7.65 | 2.15 |

| Read their partner’s digital conversation(s) with other people without their permission | 8.38 | 1.92 | 7.79 | 2.09 |

| Taken over their partner’s digital device conversation with another person in a way that made the partner feel uncomfortable | 8.31 | 2.07 | 7.69 | 2.39 |

| Sent their partner unwelcome nude images | 8.29 | 2.12 | 7.63 | 2.52 |

| Pretended to be their partner on a digital device in a way that made the partner feel uncomfortable | 8.28 | 2.02 | 7.69 | 2.31 |

| Made their partner stop interacting with another person(s) on their digital device | 8.28 | 1.89 | 7.69 | 2.20 |

| Interacted with their partner on a digital device without informing the partner who they were | 8.27 | 2.00 | 7.95 | 2.19 |

| Logged onto their partner’s digital device without their permission | 8.26 | 1.95 | 7.83 | 2.20 |

| Posted something negative through their partner’s account without their permission | 8.26 | 1.93 | 7.57 | 2.21 |

| Pressured their partner to watch pornography | 8.20 | 2.24 | 7.61 | 2.48 |

| Took their partner’s digital device password without their permission | 8.20 | 1.95 | 7.80 | 2.31 |

| Made their partner remove or add contact(s) on their digital device | 8.14 | 1.92 | 7.56 | 2.25 |

| Shared a hurtful meme about their partner on a digital device | 8.09 | 2.18 | 7.09 | 2.53 |

| Changed an aspect of their partner’s online profile without their permission | 7.91 | 2.16 | 7.21 | 2.26 |

| Called their partner insulting names on a digital device | 7.86 | 2.07 | 6.87 | 2.30 |

| Posted indirect comments that criticized their partner without using their name | 7.80 | 2.14 | 7.06 | 2.42 |

| Pressured their partner to share their password(s) with them | 7.70 | 2.19 | 7.51 | 2.26 |

| Shared an embarrassing non-sexual photo or video of their partner on a digital device | 7.56 | 2.39 | 6.65 | 2.55 |

| Note: Practitioners were requested to rate each behavior on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 10 (Extremely) based on the extent to which they thought each behavior to be (a) distress-inducing and (b) fear-inducing. * = Behaviors ranked in order of highest to lowest mean Distress ratings. | ||||

References

- Afrouz, Rojan. 2023. The nature, patterns and consequences of technology-facilitated domestic abuse: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 24: 913–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghtaie, Nadia, Cath Larkins, Christine Barter, Nicky Stanley, Marsha Wood, and Carolina Øverlien. 2018. Interpersonal violence and abuse in young people’s relationships in five European countries: Online and offline normalisation of heteronormativity. Journal of Gender-Based Violence 2: 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanasreh, Enas, Rebekah Moles, and Timothy F. Chen. 2019. Evaluation of methods used for estimating content validity. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 15: 214–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, Kristin. 2008. Is Partner Violence Worse in the Context of Control? Journal of Marriage and Family 70: 1157–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, Ximena, and Emily Schkeryantz. 2015. Intimate relationships and personal distress: The invisible harm of psychological aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 41: 1332–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barter, Christine, Nicky Stanley, Marsha Wood, Alba Lanau, Nadia Aghtaie, Cath Larkins, and Carolina Overlien. 2017. Young people’s online and face-to-face experiences of interpersonal violence and abuse and its subjective impact across five European countries. Psychology of Violence 7: 375–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. Daniel, Karen O’Quin, Jim Fultz, Mary Vanderplas, and Alice Isen. 1983. Influence of self-reported distress and empathy and egoistic versus altruistic motivation for helping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 45: 706–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Diana, Elise Guran, Michelle Ramos, and Gayla Margolin. 2011. College students’ electronic victimization in friendships and dating relationships: Anticipated distress and associations with risky behaviors. Violence and Victims 26: 410–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, Godfred, Torsten Neilands, Edward Frongillo, Hugo Melgar-Quiñonez, and Sera Young. 2018. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health 6: 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrajo, Erika, Manuel Gámez-Guadix, and Eether Calvete. 2015a. Cyber dating abuse: Prevalence, context, and relationship with offline dating aggression. Psychological Reports 116: 565–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrajo, Erika, Manuel Gámez-Guadix, Noemi Pereda, and Esther Calvete. 2015b. The development and validation of the cyber dating abuse questionnaire among young couples. Computers in Human Behavior 48: 358–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brod, Meryl, Laura Tesler, and Torsten Christensen. 2009. Qualitative research and content validity: Developing best practices based on science and experience. Quality of Life Research 18: 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Cynthia. 2021. Redefining the Measurement of Technology-Facilitated Abuse in Relationships: The TAR Scale. Ph.D. thesis, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Cynthia, and Kelsey Hegarty. 2018. Digital dating abuse measures: A critical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 40: 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Cynthia, and Kelsey Hegarty. 2021. Development and validation of the TAR Scale: A measure of technology-facilitated abuse in relationships. Computers in Human Behavior Reports 3: 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Cynthia, Lena Sanci, and Kelsey Hegarty. 2021. Technology-facilitated abuse in relationships: Victimisation patterns and impact in young people. Computers in Human Behavior 124: 106897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Cynthia, Michael Flood, and Kelsey Hegarty. 2020. Digital dating abuse perpetration and impact: The importance of gender. Journal of Youth Studies 25: 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, Candace, Bonnie Halpern-Felsher, Roberta Rehm, Sally Rankin, and Janice Humphreys. 2013. “It was pretty scary”: The theme of fear in young adult women’s descriptions of a history of adolescent dating abuse. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 34: 803–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcia, Marilia, David Bonsall, Peter Bloomfield, Sudhakar Selvaraj, Tatiana Barichello, and Oliver Howes. 2016. Stress and neuroinflammation: A systematic review of the effects of stress on microglia and the implications for mental illness. Psychopharmacology 233: 1637–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caridade, Sónia, Teresa Braga, and Erika Borrajo. 2019. Cyber dating abuse (CDA): Evidence from a systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 48: 152–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpernter, Serena. 2018. Ten steps in scale development and reporting: A guide for researchers. Communication Methods and Measures 12: 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercone, Jennifer, Steven Beach, and Ileana Arias. 2005. Gender symmetry in dating intimate partner violence: Does similar behavior imply similar constructs? Violence and Victims 20: 207–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Jessica, Heejung Park, David Almeida, Julienne Bower, Steve Cole, Michael Irwin, Heather McCreath, Teresa Seeman, and Andrew Fuligni. 2019. Psychosocial stress and C-reactive protein from mid-adolescence to young adulthood. Health Psychology 38: 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, Robert, Mark Schaller, Donald Houlihan, Kevin Arps, Jim Fultz, and Arthur Beaman. 1987. Empathy-based helping: Is it selflessly or selfishly motivated? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52: 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, Janice, Jill Carlton, Andrew Grundy, Elizabeth Taylor Buck, Anju Devianee Keetharuth, Thomas Ricketts, Michael Barkham, Dan Robotham, Diana Rose, and John Brazier. 2018. The importance of content and face validity in instrument development: Lessons learnt from service users when developing the Recovering Quality of Life measure (ReQoL). Quality of Life Research 27: 1893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, Nicole. 2016. Young Adult Dating Violence and Coercive Control: A Comparative Analysis of Men and Women’s Victimization and Perpetration Experiences. New York: Syracuse University. [Google Scholar]

- Cyber Civil Rights Initiative. 2014. End Revenge Porn: A Campaign of the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative. Available online: https://www.cybercivilrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/RPStatistics.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Davies, Elaine, Jacqueline Clark, and Al-Leigh Roden. 2016. Self-reports of adverse health effects associated with cyberstalking and cyberharassment: A thematic analysis of victims’ lived experiences. Faculty Articles & Research 1: 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Devellis, Robert. 2017. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed. Edited by Leonard Bickham and Debra J. Rog. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Diette, Timothy, Arthur Goldsmith, Darrick Hamilton, William Darity, Jr., and Katherine McFarland. 2014. Stalking: Does it leave a psychological footprint? Social Science Quarterly 95: 563–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobash, R. Emerson, and Russell Dobash. 1979. Violence against Wives: A Case against the Patriarchy. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dragiewicz, Molly, Bridget Harris, Delanie Woodlock, Michael Salter, Helen Easton, Angela Lynch, Helen Campbell, Jhan Leach, and Lulu Milne. 2019. Domestic Violence and Communication Technology: Survivor Experiences of Intrusion, Surveillance, and Identity Crime. Sydney: Australian Communications Consumer Action Network. [Google Scholar]

- Dragiewicz, Molly, Delanie Woodlock, Bridget Harris, and Claire Reid. 2018. Technology-facilitated coercive control. In The Routledge International Handbook of Violence Studies. Edited by Walter S. DeKeseredy, Callie Marie Rennison and Amanda K. Hall-Sanchez. London: Routledge, pp. 244–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, Michelle, Jody Ross, and Elizabeth Tobin. 2015. Sexting: A new, digital vehicle for intimate partner aggression? Computers in Human Behavior 50: 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerksen, Kari, and Erica Woodin. 2019. Cyber dating abuse victimization: Links with psychosocial functioning. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36: NP10077–NP10105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebesutani, Chad, Ashley Smith, Adam Bernstein, Bruce Chorpita, Charmaine Higa-McMillan, and Brad Nakamura. 2011. A bifactor model of negative affectivity: Fear and distress components among younger and older youth. Psychological Assessment 23: 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, Nancy, Richard Fabes, Paul Miller, Jim Fultz, Rita Shell, Robin Mathy, and Ray Reno. 1989. Relation of sympathy and personal distress to prosocial behavior: A multimethod study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Maggie, Emma Howarth, Alison Gregory, Kelsey Hegarty, and Gene Feder. 2014. “Even ‘daily’ is not enough”: How well do we measure domestic violence and abuse? A thinkaloud study of a commonly used self-report scale. Violence and Victims 31: 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiolet, Renee, Cynthia Brown, Molly Wellington, Karen Bentley, and Kelsey Hegarty. 2021. Exploring the impact of technology-facilitated abuse and its relationship with domestic violence: A qualitative study on experts’ perceptions. Global Qualitative Nursing Research 8: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishta, Alba, and Eva-Maria Backé. 2015. Psychosocial stress at work and cardiovascular diseases: An overview of systematic reviews. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 88: 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, Asher, Anastasia Powell, and Sophie Hindes. 2023. An Intersectional Analysis of Technology-Facilitated Abuse: Prevalence, Experiences and Impacts of Victimization. The British Journal of Criminology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follingstad, Diane, and M. Jill Rogers. 2013. Validity concerns in the measurement of women’s and men’s report of intimate partner violence. Sex Roles 69: 149–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth-Marnat, Gary. 2009. Handbook of Psychological Assessment. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby, Sherry. 2016. Self-report measures that do not produce gender parity in intimate partner violence: A multi-study investigation. Psychology of Violence 6: 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Bridget, and Delanie Woodlock. 2018. Digital coercive control: Insights from two landmark domestic violence studies. The British Journal of Criminology 59: 530–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Bridget, and Delanie Woodlock. 2022. Spaceless violence: Women’s experiences of technology-facilitated domestic violence in regional, rural and remote areas. In Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice; Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, Kelsey, Mary Sheehan, and Cynthia Schonfeld. 1999. A multidimensional definition of partner abuse: Development and preliminary validation of the Composite Abuse Scale. Journal of Family Violence 14: 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, Nicola, and Anastasia Powell. 2016. Sexual violence in the digital age: The scope and limits of criminal law. Social and Legal Studies 25: 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, Nicola, Asher Flynn, and Anastasia Powell. 2019. Responding to ‘Revenge Pornography’: Prevalence, Nature and Impacts; Edited by Australian Institute of Criminology. Canberra: Criminology Research Advisory Council.

- Hinson, Laura, Lila O’Brien-Milne, Jennifer Mueller, Vaiddehi Bansal, Naome Wandera, and Shweta Bankar. 2019. Defining and Measuring Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence. Edited by International Center for Research on Women (ICRW). Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, Dianne, and Sidney Mitchell. 2009. Cyberbullying: Causes, effects, and remedies. Journal of Educational Administration 47: 652–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouriles, Ernest, and Akihito Kamata. 2016. Advancing measurement of intimate partner violence. Psychology of Violence 6: 347–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, Ronald, Gavin Andrews, Lisa Colpe, Eva Hiripi, Daniel Mroczek, S-LT Normand, Ellen Walters, and Alan Zaslavsky. 2002. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine 32: 959–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogler, Lydia, Veronika Müller, Amy Chang, Simon Eickhoff, Peter Fox, Ruben Gur, and Birgit Derntl. 2015. Psychosocial versus physiological stress—Meta-analyses on deactivations and activations of the neural correlates of stress reactions. NeuroImage 119: 235–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamputtong, Pranee. 2011. Focus group methodology: Introduction and history. In Focus Group Methodology: Principles and Practice. Cambridge, MA: University Press, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, Megan, Jaime Booth, Jill Messing, and Jonel Thaller. 2016. Experiences of online harassment among emerging adults: Emotional reactions and the mediating role of fear. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 31: 3174–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, Maya, Elissa Epel, Shelley Kind, Manisha Desai, Christine Parks, Dale Sandler, and Nayer Khazeni. 2016. Perceived stress and telomere length: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and methodologic considerations for advancing the field. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 54: 158–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, Andreia, Mariana Gonçalves, Cristina Soeiro, and Marlene Matos. 2020. Intimate partner homicide: A meta-analysis of risk factors. Aggression and Violent Behavior 50: 101358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, Jill, Meredith Bagwell-Gray, Megan Lindsay Brown, Andrea Kappas, and Alesha Durfee. 2020. Intersections of stalking and technology-based abuse: Emerging definitions, conceptualization, and measurement. Journal of Family Violence 35: 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Kimberly, David Finkelhor, Lisa Jones, and Janis Wolak. 2012. Prevalence and characteristics of youth sexting: A national study. Pediatrics 129: 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, Elizabeth, Poulami Maitra, Jackie Sheridan, Emily Rothman, Erica Olsen, and Elaina Roberts. 2023. Technology-facilitated abuse of young adults in the United States: A latent class analysis. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 17: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the eSafety Commissioner. 2017. Image-Based Abuse National Survey: Summary Report; Edited by Office of the eSafety Commissioner. Canberra: Australian Government.

- O’Leary, K. Daniel, Heather Foran, and Shiri Cohen. 2013. Validation of Fear of Partner Scale. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 39: 502–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E. Carolyn, Bonnie Kerker, Katharine McVeigh, Catherine Stayton, Gretchen Van Wye, and Lorna Thorpe. 2008. Profiling risk of fear of an intimate partner among men and women. Preventive Medicine 47: 559–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Barón, Jéssica, Irene Montiel, Juan Manuel Machimbarrena, Liria Fernández-González, Esther Calvete, and Joaquín González-Cabrera. 2020. Epidemiology of cyber dating abuse victimization in adolescence and its relationship with health-related quality of life: A longitudinal Study. Youth & Society 54: 711–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Filipa, Brian Spitzberg, and Marlene Matos. 2016. Cyber-harassment victimization in Portugal: Prevalence, fear and help-seeking among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior 62: 136–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, Anastasia, and Nicola Henry. 2016. Policing technology-facilitated sexual violence against adult victims: Police and service sector perspectives. Policing and Society 28: 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruessner, Jens, Katarina Dedovic, Najmeh Khalili-Mahani, Veronika Engert, Marita Pruessner, Claudia Buss, Robert Renwick, Alain Dagher, Michael Meaney, and Sonia Lupien. 2008. Deactivation of the limbic system during acute psychosocial stress: Evidence from positron emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Biological Psychiatry 63: 234–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randa, Ryan. 2013. The influence of the cyber-social environment on fear of victimization: Cyberbullying and school. Security Journal 26: 331–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, Lauren, Kourtney Conn, and Karin Wachter. 2020. Name-calling, jealousy, and break-ups: Teen girls’ and boys’ worst experiences of digital dating. Children and Youth Services Review 108: 104607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, Lauren, Richard Tolman, and L. Monique Ward. 2016. Snooping and sexting digital media as a context for dating aggression and abuse among college students. Violence against Women 22: 1556–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, Lauren, Richard Tolman, and L. Monique Ward. 2017. Gender matters: Experiences and consequences of digital dating abuse victimization in adolescent dating relationships. Journal of Adolescence 59: 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, Dennis, Megan Kearns, Debra Houry, Linda Valle, Kristin Holland, and Khiya Marshall. 2016. Dating violence and injury among youth exposed to violence. Pediatrics 137: e20152627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Silva, Tiago, Conceição Nogueira, and Liliana Rodrigues. 2021. Intimate abuse through technology: A systematic review of scientific constructs and behavioral dimensions. Computers in Human Behavior 122: 106861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Michaela, Colleen Fisher, Parveen Ali, Peter Allmark, and Lisa Fontes. 2022. Technology-facilitated abuse in intimate relationships: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 24: 2210–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorelli, Marcos, Abgela Taft, Deirdre Gartland, Lisa Hooker, Christine McKee, Harriet MacMillan, Stephanie Brown, and Kelsey Hegarty. 2020. How valid is the question of fear of a partner in identifying intimate partner abuse? A cross-sectional analysis of four studies. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: 2535–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Darden, Joanne, Poco Kernsmith, Bryan Victor, and Rachel Lathrop. 2017. Electronic displays of aggression in teen dating relationships: Does the social ecology matter? Computers in Human Behavior 67: 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, Chelsea, and Sandra Stith. 2020. Risk factors for male perpetration and female victimization of intimate partner homicide: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 21: 527–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Evan. 2007. Coercive Control: How Men Entrap Women in Personal Life. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stonard, Karlie. 2019. Explaining ADVA and TAADVA: Risk factors and correlates. Advances in Developmental and Educational Psychology 1: 23–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonard, Karlie. 2020. “Technology was designed for this”: Adolescents’ perceptions of the role and impact of the use of technology in cyber dating violence. Computers in Human Behavior 105: 106211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, Jocelyn, Anett Gyurak, Madeleine Goodkind, and Robert Levenson. 2012. Greater emotional empathy and prosocial behavior in late life. Emotion 12: 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabachnick, Barbara, and Linda Fidell. 2013. Using Multivariate Statistics. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits, Peggy. 2010. Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51: S41–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, David. 2006. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation 27: 237–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, Chris, Joanne Bryce, and Virginia Franqueira. 2020. Technology, cyberstalking and domestic homicide: Informing prevention and response strategies. Policing and Society 31: 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turecki, Gustavo, and Michael Meaney. 2016. Effects of the social environment and stress on glucocorticoid receptor gene methylation: A systematic review. Biological Psychiatry 79: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogler, Stefan, Rachel Kappel, and Elizabeth Mumford. 2023. Experiences of technology-facilitated abuse among sexual and gender minorities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 38: 11290–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walby, Sylvia, Jude Towers, Susan Balderston, Consuelo Corradi, Brian Joseph Francis, Markku Heiskanen, Karin Helweg-Larsen, Lut Mergaert, Philippa Olive, and Catherine Emma Palmer. 2017. The Concept and Measurement of Violence against Women and Men. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, Allison, Brendan Bradley, and Karin Mogg. 2014. Biased attention to threat in paediatric anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, separation anxiety disorder) as a function of ‘distress’ versus ‘fear’diagnostic categorization. Psychological Medicine 44: 607–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirtz, Petra, and Roland von Känel. 2017. Psychological stress, inflammation, and coronary heart disease. Current Cardiology Reports 19: 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodlock, Delanie, Mandy McKenzie, Deborah Western, and Bridget Harris. 2019. Technology as a weapon in domestic violence: Responding to digital coercive control. Australian Social Work 73: 368–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, Joanne, Jacqueline Wheatcroft, Emma Short, and Rhiannon Corcoran. 2017. Victims’ voices: Understanding the emotional impact of cyberstalking and individuals’ coping responses. SAGE Open 7: 2158244017710292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Szde. 2017. Using mixed methods to understand the positive correlation between fear of cyberbullying and online interaction. In Violence and Society: Breakthroughs in Research and Practice. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 150–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanzadeh, Vahid, Maryam Rassouli, Abbas Abbaszadeh, Hamid Alavi Majd, Alireza Nikanfar, and Akram Ghahramanian. 2014. Details of content validity and objectifying it in instrument development. Nursing Practice Today 1: 163–71. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).