Abstract

Russia’s armed attack on Ukraine on 24 February 2022 started one of the worst refugee crises of the 21st century. It caused involuntary migrations of Ukrainians to other countries, mainly to Europe, and caused the refugees to face the challenge of integrating with the host countries’ labor markets. The aim of this study was to analyze the views of the Ukrainian refugees who migrated to two European countries: Poland and Hungary. We took into account self-esteem, social support, good job expectations, and submissiveness in the labor market. The data were obtained via a survey method using the modified CAPI (Computer-Assisted Personal Interview) technique between 21 November and 20 December 2022 from 807 adult Ukrainian refugees. Results show that disability fosters lower self-esteem, self-assessment of resources, and job demands. Among those who have children, the mean value of self-esteem was higher than in the group without any children. No statistically significant differences were found in the area of professional work. According to the estimation of structural model results, expectations of a good job have a significant, negative effect on the tendency toward submissiveness. The assessment of personal resources and the level of self-esteem have a significant and positive effect on the expectations of a good job. Both a higher level of personal resources and a higher level of self-esteem resulted in higher good job expectations. The assessment of personal resources also has a positive effect on the level of self-esteem. We also found a direct relationship between personal resources, self-esteem, and the tendency toward submissiveness.

1. Introduction

Russia’s armed attack on Ukraine on 24 February 2022 started one of the worst refugee crises of the 21st century. It resulted in involuntary migrations of Ukrainians to other countries, mainly to Europe, but also Russia (Konstantinov et al. 2023). When leaving their home country, Ukrainian refugees lost not only their existing social ties, but also their previous professional jobs, and were faced with the challenge of integrating with the labor markets of the host countries (Tsolak and Bürmann 2023). The integration of refugees differs substantially from the integration of other migrants (Brücker et al. 2019; Fasani et al. 2022). First, refugees often experience traumatic episodes caused, for example, by war-related outcomes. These episodes occur not only in their home countries, but also during travels and in the host countries (for example, in refugee camps) (Brell et al. 2020). Second, in many cases, a rapid, unprepared migration results in refugees arriving the host countries with inadequate or completely lacking skills in the local language (van Tubergen and Kalmijn 2009; Kristen and Seuring 2021).

Refugees have a much more limited ability to choose their migration destination compared to economic migrants (Brell et al. 2020). They may face a biased perception from potential employers who may view refugees as candidates suitable only for low-skilled jobs (Boerchi 2023; Coates and Carr 2005). Moreover, it is harder for refugees traveling with small children and other dependents to invest additional time to improve their language skills in the host country, or partake in schooling or training that can help them in the labor market of the new country (Hartmann and Steinmann 2021; Bernhard and Bernhard 2021). Having family responsibilities may affect the integration of refugee women; it may lead to a worsening position in the European labor market and it may lead to inequalities which may intensify over time (Cheung and Phillimore 2017; Salikutluk and Menke 2021). As single parents, refugee women may face discrimination and they may experience disapproval within their communities, which further isolates them in their already marginalized positions (Bloch et al. 2000). Refugees may also face various labor market integration policies enforced by the hosting countries. One of them is the “work first” policy (Arendt 2022) that favors any type of work or employment taken on by the refugees to integrate them into the labor market while not taking into account previous job experience, skills, and the educational background of the refugee (Tsolak and Bürmann 2023). Refugees also face an uncertain future. They do not know when and if they can return to their home country, if asylum will be granted to them and their families, or if it will be temporary or permanent (Brell et al. 2020).

Such a particular situation and the obstacles which refugees face makes the group vulnerable to a more disadvantaged situation than economic migrants in European countries (Brücker et al. 2019; Bevelander et al. 2019; Fasani et al. 2022). This may lead to a loss of self-esteem as they are unable to secure appropriate employment (Willott and Stevenson 2013) and have lower future job expectations (Akkaymak 2017). Previous studies showed that refugees: often face a loss in occupational status compared to the situation before the migration (Chiswick et al. 2005; Tsolak and Bürmann 2023); occupy jobs with a significantly lower level of wages (Brell et al. 2020); and undertake part-time or temporary jobs (Bakker et al. 2017; Jackson and Bauder 2014) requiring low skills (Kanas and Steinmetz 2021) for which they are overqualified (Akresh 2006; Lamba 2003). Finding employment was perceived as one of the major problems of Chilean refugees in Britain, just after housing and language (Joly 2016). Although initially after arriving, professionally qualified refugees had positive attitudes regarding a return to their profession before the migration, their attitudes often changed the more time the refugees spent in the United Kingdom (Willott and Stevenson 2013).

Such a disadvantaged labor market situation may lead to prolonged unemployment for the refugees in European host countries, especially refugees from culturally distant areas of Africa and Asia (Lundborg 2013). Brell et al. (2020) provided an overview of the integration of refugees into the labor markets of a number of high-income countries, including European countries (Denmark, Finland, Germany, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom). They found that the employment rates of refugees are below 20 percent in the first two years after migration (except for the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada). The employment rates of refugees are below those of other migrants, especially in the first years of stay in the host country (Dustmann et al. 2017), and increase in the subsequent years (Brell et al. 2020). These findings are in line with the results of other studies. Fasani et al. (2022) analyzed the labor market performance over time of refugees and other types of migrants across 20 European countries. They found that refugees are 11.6% less likely to have a job and 22% more likely to be unemployed than other migrants, and also have a lower income, occupational quality, and labor market participation. A mixed-method study of refugees’ experiences of vocational stress conducted by Baranik et al. (2018) on 159 refugees showed that the most frequently reported refugee vocational stressor was “access and opportunity” (31%). The stressor encompasses feelings of a discontinuation of past work experience when searching for a job, struggles with the job search, and exploitation (e.g., low pay). In the long run, prolonged exclusion from the labor market and reliance on government-provided benefits results not only in poverty, but also in frustration and a loss of pride and dignity among refugees and their families (Bloch et al. 2000).

Campion (2018) argues that unlike the general trend of career adaptability, which has a strong positive relationship with objective markers of career success (like good job quality, high pay), refugees are likely to experience downward occupational mobility, prioritizing the generation of networks for social safety rather than the acquisition of jobs in line with personal skills. Such kinds of behavior by refugees in the labor market of the host country leads to lower-status jobs than in their home country, low payments, and fewer opportunities for language skill acquisition. On the other hand, researchers also presented evidence that refugees are likely to have a higher net return to criminal activity than economic migrants (Bell et al. 2013). The resettlement of refugees from richer Western nations to poorer countries was suggested as a possible solution (Azarnert 2018).

Despite its clear importance, very few studies focus on the refugees’ vocational behavior after they leave their home countries, including navigating their careers, seeking employment, or identifying work-related challenges (Newman et al. 2018b). Even fewer studies focus on the refugees’ submissive behavior in the labor market and their job expectations. The authors have not found any research which sought to find a relationship between the above, as well as the specific role of self-esteem and social support of the refugees. The relationship between social support, self-esteem, personal and professional situation, the tendency toward submissiveness, and expectations of a good job have not been thoroughly examined. This study seeks to fill this gap. Understanding these complex relationships may help in the development of interventions aimed at helping to find jobs suitable to the expectations of refugees, and identify possible areas upon which the most attention should be placed, while assisting refugees in the adaptation process through counseling professionals, organizations, and policy makers (Newman et al. 2018b).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Job Expectations

Finding employment is a crucial step in the integration or settlement process within the new country of stay. It is almost as important as gaining language skills and housing (Joly et al. 1997). If the process of finding a proper job is resolved successfully, it may lead to a reduction in the burden incurred by local authorities (Joly 2016).

Job expectations are notions concerning responsibilities, roles, and tasks of the workplace and work environment (Major et al. 1995). They may also simply be the desire to achieve something from work (Thamrin et al. 2022), or beliefs that an individual will receive an outcome (or a level of an outcome) in his or her job (Greenhaus et al. 1983). Job expectations are particularly important in the context of experiences of newcomer workers or employees since they influence the future relationship of the organization and the individual (Buckley et al. 1998). Researchers usually focus on newcomers’ expectations formed before the entry into an organization like during recruitment. The expectations formed can also be about the roles within the workplace. Then, after the entry into the workplace, the expectations are confronted with the organization’s real working conditions. The expectations can therefore be met, exceeded, or unmet, which may produce the effect of a “reality shock” (Major et al. 1995; Walk et al. 2013).

Locke (1976) proposed that unmet job expectations produce a pleasant or unpleasant surprise, or satisfaction or dissatisfaction. It is possible for realistic job expectations to be confirmed or met at a workplace. This may produce job satisfaction that in return reduces the tendency of a particular individual to withdraw from their employer. Nonetheless, realistic expectations do not invariably produce higher levels of satisfaction than unrealistic ones (Greenhaus et al. 1983).

Studies connect unmet expectations with lower levels of job satisfaction (Turnley and Feldman 2000; Nelson and Sutton 1991) and higher levels of turnover (Lance et al. 2000). Therefore, organizations often implement procedures to reduce job expectations of newcomers in order to increase their satisfaction and reduce turnover (Buckley et al. 1998). Maden et al. (2016) tried to empirically explore how employees differ in their responses to unmet job expectations. They found that employees with more positive future work-related expectations have stronger relationships between unmet job expectations, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction, and that efficacy beliefs moderated the relationship of unmet job expectations and turnover intention. A meta-analysis on the effects of met expectations for newcomers to organizations, which included 31 studies of 17,241 people, found the mean correlations of 0.39 for job satisfaction and organizational commitment, 0.29 for intent to leave, 0.19 for job survival, and 0.11 for job performance (Wanous et al. 1992). In a recent study performed during the COVID-19 pandemic, Thamrin et al. (2022) concluded that emotional mental conditions, psychological well-being, job performance, and job satisfaction have a positive effect on job expectations. The results of another study on employees’ expectations in Lithuania indicated that an attractive salary and good working conditions are the most important attributes (69% and 61%, respectively), especially for employees older than 35 years old (Bakanauskienė et al. 2014). Linden (2015) noted that job expectations may vary between generations. Millennials seek work/life flexibility, supervisors who recognize achievements, and employers that provide opportunities for promotions and compensation based on job performance. Other research among hotel employees concluded that employee motivation decreases when extrinsic rewards (like good pay, monetary bonuses, pay increases, or promotions) are not provided (Chiang and Jang 2008).

There is still very little research about the job expectations of refugees and most of it is based on qualitative research on small samples of respondents. Baran et al. (2018) interviewed 85 refugees in the United States. The findings indicated that refugees who developed unrealistically positive expectations about life in the country (the “American dream”), face underemployment and experience job dissatisfaction when underemployed. Another study worth mentioning was conducted among 22 young (18 to 35 years old) adult refugees using semi-structured interviews. The study indicated that the participants expected their jobs to be in line with their interests and personalities, have good working conditions, and allow for the opportunities to help others (Fedrigo et al. 2023).

2.2. Submissiveness in the Labor Market and Self-Esteem

Historically, organizations preferred the so called “ideal worker norm”, a model of a worker who puts the job ahead of any other areas of life and is highly available to the employer (Coron and Garbe 2023). Nonetheless, an increased number of employees who experienced a lack of enthusiasm, decreased commitment, and lower productivity at the job place led to the development of the work–life balance (WLB) concept in the 1970’s and 1980’s (Liszka and Walawender 2019). The WLB concept gained popularity in the United States and the European Union. The ideal worker norm is still widely accepted in developing countries, like Bangladesh, where workers, especially women, can face poor earnings, long working hours, overtime work without extra payment, lack of safety and security, and no access to sick leave, vacations or weekends. Their situation is even worse as submissive employee behavior is connected with exploitation by managers and supervisors (Islam et al. 2017). Their passive or submissive behavior may present them as easy and vulnerable targets with low self-esteem who are unable to defend themselves from aggressors (like abusive supervisors) (Henle and Gross 2014). Researchers usually connect abusive management with the core self-evaluation (CSE) of employee traits (Kluemper et al. 2019; Chang et al. 2012; Coron and Garbe 2023; Neves 2014). Judge et al. (1997) tried to identify dispositional factors that affect job satisfaction and proposed a model based on core evaluations which employees make about themselves, others, and the external world. The four proposed CSE traits were provisionally identified: “global” self-esteem or self-worth (Rosenberg 1989), locus of control (perceived control of external events or desired effects), generalized self-efficacy (self-ascribed estimates to meet personal challenges), and emotional stability (or ability to feel calm and secure) (Chang et al. 2012). Submissive employees with low CSE (for example, low self-esteem, low self-assessments of their worthiness and competence) and low assertiveness drew more abusive supervision and were at risk of becoming “submissive victims” (Kluemper et al. 2019). A decreased CSE and decreased coworker support may lead to increased abusive supervision, especially in downsized organizations, as Neves (2014) found in a study on a sample of 193 employee–supervisor dyads from downsized and non-downsized organizations.

Researchers very rarely explore the submissive behaviors of refugees in the labor market, and if so, they focus mainly on Muslim refugees. Zaytoun et al. (2017) received responses from Syrian refugees living in Jordan stating that their submissiveness in the host country is a necessity in order to obtain social protection and to satisfy their needs. Perceived or stereotyped submissiveness is also connected with particular groups of refugees in connection with their gender or country of origin. For example, Asian women refugees are stereotyped as being docile and submissive (Koyama 2023; Kaur 2021).

On the other hand, the self-esteem of employees very often interests researchers in many aspects. One of it is the relationship of self-esteem with wages. The research results on the connection between self-esteem and wage levels are controversial. Goldsmith et al. (1997a), using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth on a sample of 12,686 participants, found a direct effect of psychological capital (via self-esteem) and indirect (through locus of control) on an individual’s real wage. De Araujo and Lagos (2013), using data from the same National Longitudinal Study of Youth (NLSY79), found that self-esteem does not significantly affect wages directly once controlled for locus of control, but has a significant and positive impact indirectly via education. Other areas of interest are, for example, the relations between self-esteem and work conditions and outcomes (Kuster et al. 2013), or task performance at the workplace (Baumeister et al. 2003).

Willott and Stevenson (2013) explored the attitudes toward work and experiences of professionally qualified refugees who tried to find a job in the United Kingdom. Their findings were that, initially, the refugees are motivated to work, but they suffer a loss of self-esteem if they are unable to find desired employment, as self-esteem may be boosted by occupational successes (Baumeister et al. 2003). In another study among 90 Liberian refugees in Ghana, Wehlah and Akotia (2000) found a positive correlation between self-esteem and life satisfaction. Within the study, most of the refugees indicated that they are not satisfied with their present life. Self-esteem was also found to be a significant predictor of well-being after adjusting for pre-migration and demographic factors among a cohort of refugee youths in Australia (Correa-Velez et al. 2015).

2.3. Social Support

Although there are many various definitions of “social support”, in general, it refers to material or psychological resources provided to a particular individual in a form of a social relationship (Jolly et al. 2021). Cohen (1992) distinguished three basic components of social support: social networks as social relationships, supportive behaviors that help individuals cope with stress, and perceived support of social relationships providing resources.

Refugees encounter many stressors, including job searching and building new social communities (Schwarzer et al. 1994), or finding suitable housing. Therefore, social support and social networks play a very important role in various areas of refugees’ lives (Simich et al. 2005) either when seeking employment or while already working. Possessing particular social networks (for example, contacts with ethnic (Lamba 2003) or religious and co-national groups) helps with housing and access to work (Cheung and Phillimore 2014), especially if the networks are mobilized for the job search (Gërxhani and Kosyakova 2020). In case of refugees, the support is provided usually by family members and the authorities. Refugees’ social networks are present (Gericke et al. 2018), but often diminished (Sundvall et al. 2021), and not sufficient to compensate for refugees’ downward occupational mobility (Lamba 2003). Support offered by the authorities, on the other hand, focuses mainly on offering various professional and employment services. Nonetheless, there may be a mismatch between perceptions and expectations of the services by providers and by the refugees. The latter may perceive the employment services (like training) as an opportunity to develop new social networks rather than gain new skills, which may help in finding employment (Torezani et al. 2008).

Support of the nearest and dearest (like the spouse) affects attitudes of unemployed individuals while searching for a job (Vinokur and Caplan 1987). The higher the level of instrumental and emotional support, the lower the level of the family interfering with work (Adams et al. 1996). Such support is also very important after a job is found. The Newman et al. (2018a) study among already employed refugees living in Australia concluded that perceived organizational support and perceived family support are positively related to the well-being of refugees. On the other hand, a lack of social support and prolonged unemployment of refugees can affect their health. Schwarzer et al. (1994), in a study among 235 East German refugees who entered West Germany after the 1989 collapse of the communist system, concluded that in the two subsequent years, the refugees who remained unemployed indicated worse self-reported health and that the health-stress relationship was moderated by social support. Makwarimba et al. (2010) interviewed Chinese and Somali refugees in Canada and found that social support facilitated their employment, but also reduced stress, and improved mental and physical health.

2.4. Human Capital Theory

The concept of human capital, which emphasizes the importance of knowledge and qualifications in the labor market, was created by T.W. Schultz (1961a, 1961b) and developed by Gary S. Becker. It considers expenditures on health, education, internal migrations to find a better job, or on-the-job training as examples of investments in human capital to obtain a higher return of investment, for example, in the form of higher earnings and a wider range of available employment choices. Consequently, Shultz considered lower earnings to be the consequence of such individual factors such as lower or no attained education, poor health, lack of needed skills, or even age (as younger workers more readily move toward finding a suitable job). Therefore, he focused on the five main categories of investments in human capital: health services and facilities, on-the-job-training (including apprenticeships), formal education of all levels, study programs for adults, and the migration of individuals or families toward job opportunities (Schultz 1961b).

Becker (1962) also focused on individual investments on information about better employment opportunities, like learning about the wages offered by different companies, spending time to find a suitable job, finding employment agencies, or investing time and resources for geographical movement (for example, to another country). He concluded that younger people have a greater incentive to invest in themselves as they may collect the return of the investment over many years. Moreover, differences in earnings between particular workers may also be explained as consequences of the level of the investment in themselves. Besides investments in human capital by governments and individuals, Becker also emphasized the importance of time and money invested by families into their children (Becker 1962).

Schultz (1962) emphasized that not everyone’s economic capabilities are acquired at birth, during entry into the workplace, or upon the completion of schooling, but many of them are developed by activities with attributes of an investment, for example, in health, additional training or schooling, in migration, or searching for information about job opportunities.

Currently, most studies about the integration of migrants in the labor market focus on the human capital approach (Boerchi 2023), especially studies concerning refugees (for example, de Vroome and van Tubergen 2010; De Voretz et al. 2004; Cortes 2004; Duleep and Regets 1999). It was also the case in building the hypotheses of our study.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Method

A quantitative research concerning the situation of refugees from Ukraine was conducted using a survey questionnaire during a one month period (from 21 November until 20 December 2022) in Poland and Hungary. The data were collected via face-to-face interviews through a survey method using the modified CAPI (Computer-Assisted Personal Interview) technique. The interviewer selected the respondents in accordance with the sample instructions and provided a respondent with a mobile device on which the survey tool was uploaded. The data were automatically recorded in the system and ready for analysis—so there was no need for manual recording. Automation accelerated the processing of the results. The respondents completed the questionnaire by themselves.

The survey targeted Ukrainians aged 18 and over who crossed the Polish–Ukrainian and Hungarian–Ukrainian borders after the date of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (24 February 2022). The structure of the defined population was not known.

3.2. Sample

Due to the dynamic size and the structure of the population, it was assumed that in order to achieve an appropriate selection of the sample, the population should be divided into strata from which individuals were then drawn for the sample. Our research had respondents from all Ukrainian oblasts, including the occupied Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Luhansk, and Donetsk oblasts.

The size of the population of Ukrainian refugees residing in Poland and Hungary was estimated in September, 2022 based on the latest UNHCR data available: 1,017,655 in Poland (active registrations in the PESEL database, from around the 1.5 million refugees who applied for a temporary protection, those who left the country for over 30 days were excluded) and 28.662 in Hungary (applications for temporary protection). The total estimated population size was approximately 1.05 million Ukrainians. According to the outlines in the table by Krejcie and Morgan (1970), a sample size of 384 is suggested as appropriate for a population of one million. We used the well-known—among behavioral and social science researchers—table by Memon et al. (2020) for sample size determination.

The selection criteria were as follows: (1) war refugee—the respondent first entered the territory of Hungary or Poland after the date of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (24 February 2022); (2) Ukrainian resident—the respondent was a resident of Ukraine before first entering the territory of Poland or Hungary; (3) adult—the respondent was at least 18 years old.

A total of 807 refugees were surveyed (400 arriving in Poland and 407 in Hungary). We used the data obtained from all the 807 valid questionnaires for the purpose of the research presented in this manuscript.

3.3. Hypotheses Developed from the Human Capital Theory Perspective and the Proposed Research Model

The following research questions were asked for the purpose of the article:

- Do expectations of a good job, positive self-esteem, possessed personal resources and a tendency to be submissive depend on the refugee’s professional and personal situation?

- How do positive self-esteem and possessed personal resources affect expectations of a good job preference?

- How can positive self-esteem and possessed personal resources influence the submissiveness tendency?

The general thesis adopted in the research is that the expectations of a good job, positive self-esteem, and possessed personal resources influence the propensity to be submissive about the conditions of the work undertaken.

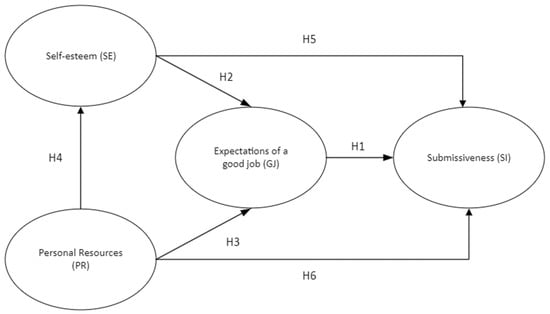

For the purposes of the article, the following research hypotheses were adopted:

H1.

The higher the level of good job (GJ) expectations, the lower the tendency toward submissiveness (SI).

H2.

The higher the personal resources’ (PRs) assessment level, the higher the good job (GJ) expectations.

H3.

The higher the level of self-esteem (SE), the higher the good job (GJ) expectations.

H4.

The higher the personal resources’ (PRs) assessment level, the higher the level of self-esteem (SE).

H5.

The higher the personal resources’ (PRs) assessment level, the lower the tendency toward submissiveness (SI).

H6.

The higher the level of self-esteem (SE), the lower the tendency toward submissiveness (SI).

Figure 1 presents the proposed research model.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model.

The STATISTICA 13.3 and SmartPLS4 4.0 software were used for data analysis. The t-Student test and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) were used to verify the hypotheses (α = 0.05, p < α). The following terms for statistical significance were adopted: p < 0.05—existing (*), p < 0.01—high (**), and p < 0.001—very high (***).

3.4. Measurements

Scale items used for measure are available in Supplementary Table S1. In the study, participants assessed, inter alia, the selected statements relating to the following four aspects:

- (1)

- Self-esteem. The M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale—SES questionnaire containing 10 items was used. The questionnaire was developed in the 1960s by Rosenberg to measure self-worth by measuring both positive and negative feelings about oneself (RSES, Rosenberg 1989). A Likert-type scale was used with 4 options (1—“Strongly Disagree”; 2—“Disagree”; 3—“Agree”; 4—“Strongly Agree”). Scores between 15 and 25 are within normal range, while scores below 15 suggest low self-esteem.

- (2)

- Perceived social support/personal resources. The C. Weinert Personal Resource Questionnaire—PRQ2000 was used (Weinert and Brandt 1987). It contains 15 (positively worded) items to measure the level of perceived social support. It is graded on a 7-point Likert scale, from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly agree”). The total score is calculated by summing all items. Scores range from 15 to 105, where higher scores indicate more support.

- (3)

- Desired job expectations as characteristics of a good workplace. There were 5 options (1—“Completely disagree”, 2—“Rather disagree”, 3—“Neither agree nor disagree”, 4—“Rather agree”, 5—“Completely agree”).

- (4)

- Submissiveness meaning a tendency to give up some job requirements in order to obtain employment. There were 5 options (1—“Completely disagree”, 2—“Rather disagree”, 3—“Neither agree nor disagree”, 4—“Rather agree”, 5—“Completely agree”).

For the purpose of this study, we also used the following data from the questionnaire: personal characteristics of the refugees (not having or having a job; not having or having children and the number of children; not having or having dependents), as well as social characteristics of the refugees (gender, age, place of residence in Ukraine before entering Poland or Hungary).

After performing the exploratory factor analysis, the following indicators were included for further analyses of all four variables (these contributed the most to the reliability of the analyzed constructs): for PRs—PR1, PR4, PR7, PR10, PR12, and PR14; for SE—SE4, SE6, and SE7; for GJ—GJ1, GJ3, GJ4, GJ5, GJ7, GJ8, and GJ12; and for SI—SI1, SI6, and SI7.

4. Results

4.1. The Refugee’s Professional and Personal Situation

Women dominated among the respondents (n = 626)—they constituted 77.57% of the respondents. The mean age of the surveyed people was 37.1 years (S.D. = 11.45 years). The surveyed refugees differed according to the criteria studied, depending on the country of destination (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the examined group.

Overall, in both surveyed refugee groups, there were 319 people who were currently working (39.52%), 90 disabled persons (11.15%), and 73 people who cared for dependent persons (9.04%). There were also 442 people who had no children (54.77%), 178 people with one child (22.05%), and 123 people with two children (15.24%). Twenty-seven of the surveyed refugees had three children (3.34%), eleven had four (1.36%), and two persons had more than four children (0.24%).

4.2. Expectations of a Good Job, Positive Self-Esteem, Possessed Personal Resources, and Submissiveness Indexes among Refugees

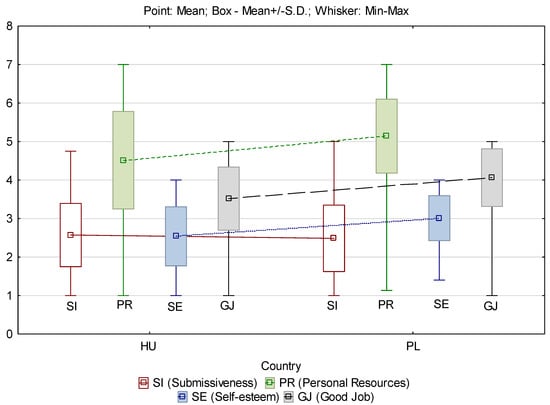

An index summary relating to each of the four indices (PRs, SE, GJ, and SI) was developed based on the responses. Its values are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Table 2.

Values of the analyzed indices.

Figure 2.

Boxplot diagram for the value of the indices. Source: Own study.

It was to be expected that for the three indices (SE, PRs, GJ), the higher the value, the more positive the outlook in the respective aspect. In the case of the last index (SI), its lower value was indicative of a higher level of firmness in career-related decision making. Analyzing the results, a statistically significant difference was found for the first three indicators (SE, PRs, GJ)—their values were higher among the surveyed refugees arriving in Poland (Table 2). As for the indicator depicting submissiveness, there was no statistically significant difference in its level between refugees arriving in Poland or Hungary (p > α p = 0.2831). This means that other factors can influence the variation in its value. The personal and professional situations of refugees were therefore taken into account during the analysis. Table 3 presents the mean values of the indices and the results of the t-Student test regarding the four grouping variables: (1) with/without employment; (2) with/without children; (3) with/without dependent persons; (4) disabled/abled person.

Table 3.

t-Student test for 4 dependent variables.

The results of the analysis indicated that only three of the grouping variables affected the value of the indices. Being a disabled person had the largest effect, resulting in differences in three of the four indices. For self-esteem, the highest mean value was observed in the group of not disabled people (2.81). Similarly, for the assessment of personal resources and good job characteristics, people who were not disabled chose the higher values for the assessed statements. This means that disability fosters lower self-esteem, a self-assessment of resources, and job demands. However, it is worth noting that among all refugees with disabilities, 51 out of 90 were working (the employment rate in this group was therefore 56.6%, comparable to the non-disabled group with 56.8%).

The mean value of self-esteem was higher among those who have children (2.90) than in the group without any children (2.66). This may be due to the treatment of children as a reference point in the statements being assessed (thus making having children the “background” of one’s own assessment—see the statements in Table S1. Referring to the submissive index, it is worth noting that the mean value was higher in the group with no children. This means that those refugees who are responsible for children want a job that enables them to care for children and reconcile work and family life.

The last group in which differences were analyzed included those with and without dependents. A statistically significant difference was not found in the assessment for any aspect.

Given the above, it can be concluded that only the personal situation of the surveyed refugees influenced the values of the survey indicators, with this being the response to the first set of research questions.

4.3. Postulated Structural Equation Model for Self-Esteem, Personal Resources, Good Job, and Submissiveness among Refugees

The previously analyzed indexes became the basis for the creation of latent constructs expressing the four dimensions: self-esteem, personal resources, good job, and submissiveness. These dimensions allowed for the creation of reflective indicators for latent variables. The exogenous group of latent variables were the SE and PRs variables and the endogenous groups were the GJ and SI variables. All of these were determined via explicit variables. The SEM model assumes that there were reflective relationships (confirmed by the results of the tetrad analysis; see Bollen and Ting 2000). This means that the explicit variables are a reflection of the latent variables.

The reliability of the constructs was measured using Cronbach’s Alpha, Dijkstra–Henseler’s rho (rho_a), Joreskog rho (rho_c), and AVE (Larcker–Fornell’s Average Variance Extracted), as presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Reliability and validity of constructs.

The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient value indicates the homogeneity of the scale (>0.6) (Sagan 2004). Both Dijkstra–Henseler’s and Joreskog’s rho values for each construct were higher than 0.7 and indicated the reliability of the scales used. The value of the square root of the AVE coefficient for each latent variable was higher than the value of the correlation of the variable with any other latent variable, indicating that the Fornell–Larcker criterion was met (Table 5).

Table 5.

HTMT matrix.

The heterotrait/monotrait ratio of the correlation matrix (HTMT matrix) proves that all correlations are below 0.85, meaning that the blocks of variables are well separated. The validity of the constructs is thus confirmed.

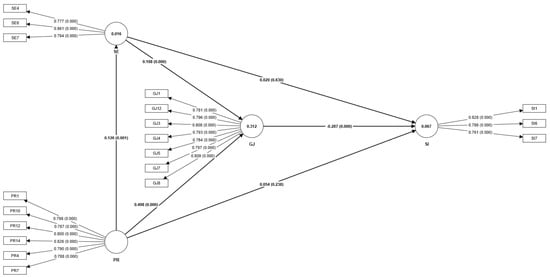

The proposed structural model was estimated with reflective indicators for all four latent variables (PRs, SE, GJ, and SI). Figure 3 and Table 6 present the structural parameters of the model.

Figure 3.

The path model of declared submissiveness to requirements for a potential job among migrants (p < 0.05).

Table 6.

Significance testing results of the structural model path coefficients and factor loadings for latent variables.

The relative chi2 value equals 201.395 (df = 146; p = 0.002) and chi2 is 1.37, which is acceptable (Byrne 1989). These values may indicate the need to reject H0 with regard to the equality of the input and the reconstituted matrices, but this situation is due to the high sample size. RMS standardized residual equals 0.025 and is lower than 0.08, which indicates a valid value. The goodness-of-fit measures of the tested model indicate a very good fit. Steige–Lind RMSEA index is 0.022, which indicates a close fit of the model to the population data (0.01 < RMSEA < 0.05). Population gamma index is 0.993 (adjusted = 0.991). McDonald’s non-centrality index is also >0.95 and equals 0.967. Other single sample fit indices confirm goodness of fit: Joreskog GFI is 0.974 (Adjusted = 0.967), which means that approximately 97% of the actual covariance is explained by the developed model. Bentler–Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI) is 0.97 and Bentler Comparative Fit Index (CFI) is 0.991.

The predictive precision of the model was evaluated by using R2 values of the endogenous latent variables (Table 7). The literature identifies specific desirable values of the coefficient of determination as significant (0.75), moderate (0.5), or weak (0.25), but in the social sciences, R2 values are lower, hence 0.04 to 0.16 is assumed to be moderately weak and 0.25 to 0.49 as moderately strong (Figueroa-García et al. 2018; Hair et al. 2017; Ritchey 2008). Based on the results from the PLS-SEM algorithm, a weak/moderately weak value of explained variance was obtained for SI (6%), and similarly for SE (1.5%). In contrast, a moderately strong value was obtained for GJ (31%).

Table 7.

Explained variance.

According to the estimation of the structural model results, expectations of good job (GJ) have a significant negative effect on the tendency toward submissiveness (SI). The regression coefficient was (−0.287) (t = 6.046; p = 0.000), which supports hypothesis 1 (H1: the higher the level of good job (GJ) expectations, the lower the tendency toward submissiveness (SI)).

The assessment of personal resources (PRs) and the level of self-esteem (SE) have a significant and positive effect on expectations of a good job (GJ). The regression coefficient for the first dependency (PRs -> GJ) was 0.498 (t = 16.291; p = 0.000), and for the second (SE -> GJ), it was 0.198 (t = 6.636; p = 0.000), which supports hypotheses 2 and 3 (H2: the higher the personal resources’ (PRs) assessment level, the higher the good job (GJ) expectations; H3: the higher the level of self-esteem (SE), the higher the good job (GJ) expectations).

The assessment of personal resources (PRs) also has a positive effect on the level of self-esteem (SE). The regression coefficient was 0.126 (t = 3.394; p = 0.001), which supports hypothesis 4 (H4: the higher the personal resources’ (PRs) assessment level, the higher the level of self-esteem (SE)). The obtained results confirmed the directions of the relationships indicated in the first four hypotheses.

Another two hypotheses assumed a direct relationship between two latent variables (PRs and SE) and the tendency toward submissiveness (SI) (H5: the higher the personal resources’ (PRs) assessment level, the lower the tendency toward submissiveness (SI); H6: the higher the level of self-esteem (SE), the lower the tendency toward submissiveness (SI)). The results of the analysis indicated that the dependency in both cases is not significant. The regression coefficient for the first dependency (PRs -> SI) was 0.054 (t = 1.180; p = 0.238), and for the second one (SE -> SI), it was 0.020 (t = 0.482, p = 0.630). The obtained results do not give any indication of a direct negative impact of the two factors (PRs and SE) on SI. However, it can be noted that there is an indirect relationship between PRs, SE, and SI, in which GJ will act as a moderator. The relationship between PRs, SI, SE, and SI is not statistically significant as we are dealing with perfect mediation.

5. Discussion

For the purpose of this study, in November–December, 2022, we collected data from 807 adult Ukrainian war refugees who entered Poland or Hungary after 24 February 2022. This study investigated relationships between (1) self-esteem (RSES, Rosenberg 1989), (2) perceived social support/personal resources (C. Weinert Personal Resource Questionnaire—PRQ2000), (3) desired job expectations, and (4) submissiveness of Ukrainian war refugees in two countries, Poland and Hungary.

Women constituted 77.57% of the respondents (Poland—89.75%, Hungary—65.60%). This distribution is in line with available data. The share of women in the refugee population differed substantially between European countries in November, 2022, with 70% being the average (OECD Data 2023). In some countries, like Poland, the share was even higher. In the OECD report published shortly before the start of our research, 92% of the adult refugees were estimated to be women (OECD Data 2022). The main reason why men were underrepresented in the studied sample, as well as in the general Ukrainian refugee population, may be the Decree of the President of Ukraine No. 64/2022 as of 24 February 2022 (“On the imposition of martial law in Ukraine”). The decree prohibited male Ukrainian citizens aged 18 to 60 from traveling abroad and was in effect at the time of the study.

Analyzing the results, we found a statistically significant difference for three indicators (SE, PRs, GJ). Their values were higher among the surveyed refugees arriving in Poland. This could be partially explained by the similarity of the Polish and Ukrainian spoken languages (Corbett and Comrie 1993) and, therefore, the human capital usable in the Polish labor market (spoken language competences possessed by the Ukrainian refugees) (Kovács et al. 2023). This would allow refugees to more readily express their need for social support in various networks, help them in finding a suitable job, negotiate the terms, or understand the supervisors’ comments.

One of our main findings is that the disability of the refugees fosters lower self-esteem, self-assessment of resources, and job demands (expectations). The findings are in line with some other studies, but the results are controversial. In a systematic literature review of studies published between 1990 and 2021 on adults with intellectual disabilities, mixed evidence was found regarding the level of self-esteem compared with the general population. In general, positive self-esteem is linked with engagement in activities by the general population and by adults with disabilities (Lee et al. 2023). In the research of Nosek et al. (2003) among 881 women in the USA, the subgroup of 475 respondents with a variety of mild to severe physical disabilities indicated, in a correlation analysis, significantly lower self-esteem and greater social isolation. Lower self-esteem was also observed in a study among adults with dyslexia and the research suggested that perceived family support has a direct influence on the self-esteem of the group (Blace et al. 2015) as well as in the case of disabled persons with multiple sclerosis (Balbis 1995). Moreover, other research studies confirmed that self-esteem and family support play an important role in adjusting to the disability (Li and Moore 1998) and they are associated with depression (Brown et al. 1986), mental, and general health (Cott et al. 1999; Lee et al. 2023; Wahl et al. 2010).

There is little research interest in job expectations of disabled employees, none of which we are familiar with that focused on disabled refugees. Therefore, our findings are yet to be confirmed by further research. Choe and Baldwin (2017) concluded that workers with long durations of disability are employed in jobs better suiting their physical limitations than workers with a shorter duration of disability. Three working conditions seem to be critical for people with disabilities: job demands (meaning being forced to work hard), control (or freedom of decision making), and physical demands of the job (Baumberg 2014; Johansson and Lundberg 2004).

Another main result of our research is that the mean value of self-esteem was higher among refugees with children than those without any children. The mean value of the submissive index was also higher in the group with no children. This means that refugees who are responsible for children want a job that enables them to care for their family and allows them to reconcile work and family life. Parenthood may enhance an individual’s self-esteem as it provides a feeling of purpose and self-worth. On the other hand, parenthood can lead to a decline in self-esteem due to increased stress and societal pressures. A recent literature review of 40 studies on adult self-esteem and family relationships indicates that parents with high self-esteem experience enhanced satisfaction with their children (El Ghaziri and Darwiche 2018). Unfortunately, not many researchers have investigated the differences in the levels of self-esteem between parents and nonparents. Usually, studies rather focus on the groups’ psychological well-being (Menaghan 1989; Ishii-Kuntz and Ihinger-Tallman 1991; Negraia and Augustine 2020) or the self-esteem of children (Harris et al. 2015; Dickstein and Posner 1978).

Our findings with respect to the submissiveness of parents are in line with the findings of other studies. In a study among a nationally representative sample of 2958 U.S. wage and salaried workers, Galinsky et al. (1996) concluded that parent and nonparent employees, although quite similar in many respects, differed in values they placed on benefits and policies, the sacrifices made in their personal lives for their jobs, and in the time available for completing household and childcare responsibilities. Job demands also foster work–family conflict between working parents (Bakker et al. 2008). The ability to manage work and family roles is affected negatively by heavy job demands, low wages, and extended parental or family responsibilities (Annor 2013). The findings of other studies (Chapple 2001; Preston et al. 1993) confirmed that women with children are likely to seek a workplace close to home and reduce commuting times.

We found that having or not having professional work did not produce a significant difference in the analyzed indices. Our findings are in line with some other research results on the relationship of unemployment and self-esteem (Shamir 1986; Hartley 1980) or well-being (Knabe and Rätzel 2010). Nonetheless, the findings are controversial, as many other studies concluded that unemployment may lower self-esteem (Goldsmith et al. 1997b; Sheeran et al. 1995; Álvaro et al. 2019; Warr and Jackson 1983).

We concluded that good job expectations have a significant negative effect on the tendency toward submissiveness. As McQuaid et al. (2001) concluded in their study among 306 unemployed job seekers, poor accessibility to a workplace may discourage people from working there because they may require access to a car and may need to integrate the work journey with other trips (picking up kids, shopping). Moreover, travel time to work is determined by the place of residence, employment locations of the family members, and family ties or responsibilities.

Finally, in our study, the assessment of personal resources and the level of self-esteem have a significant and positive effect on good job expectations. The findings are in line with other studies concluding that self-esteem increases occupational prestige and income (Kammeyer-Mueller et al. 2008), and that there are positive relationships between social support and self-esteem, general self-efficacy, and job search self-efficacy (Maddy et al. 2015).

The possibility of generalizing the study results to other refugee populations may be limited. It is difficult to directly translate the results into the context of other countries despite numerous studies on the impact of migration on the labor market in host countries. This difficulty results from the complexity of the phenomenon which was studied, differences in the labor market conditions of particular countries, diverse migration policies, and different structures of the migrant population. Each empirical study examines specific temporal and locational conditions (Piekutowska 2019). Therefore, the situation of refugees in the labor market and their impact on this market requires separate treatment. Refugees are a very specific category of migrants (due to their traumatic experiences, and specific socio-demographic structure). Recent research on refugee reception is based mainly on studies of young single men from countries in the Middle East and Africa who face institutional and structural constraints and largely hostile social attitudes (Kosyakova and Kogan 2022). There are large differences in the structures of refugees arriving in Western countries in 2015–2016, compared to refugees from Ukraine post 24 February 2022 (these differences are also confirmed by our research, the results of which are presented in this article). Kosyakova and Kogan (2022) asked an open empirical question as to whether the integration patterns of refugees arriving in 2015–2016 will be comparable to the patterns of Ukrainian refugees in 2022. There are striking differences in relation to the sociodemographic structure of the refugee population in 2015–2016 and actions taken by host countries.

Even within the post-2022 Ukrainian refugee population, it should be noted that those who crossed the border immediately after 24 February 2022 may differ from those who migrated at a later time. The latter could have some more time to prepare for the migration and could be closer in behavior to economic migrants, similarly for the Ukrainians from West Ukraine—the region that was much less affected by the war than East Ukraine.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. There were incomplete data about the population of Ukrainian war refugees in both countries. The challenge was in preparing an exhaustive sampling frame of the refugees. For example, in Poland, refugees were registered in the PESEL database, which enabled them to obtain social benefits. Nonetheless, the database lacked some records like a record of the place of residence. Another limitation about the sample features was related to the population dynamics. The fluctuation of refugees is understandable, given the situation from which they are fleeing and the opportunities they will seek in other countries. For researchers, this is a challenge in terms of difficulties in estimating and interpreting the results. Moreover, there were no data obtained about the time the sample population had spent in Poland and in Hungary.

As in the general Ukrainian refugee population, women predominated among our research respondents. This study did not investigate if possible differences exist across the genders in the studied sample. Nonetheless, women tend to be different from males in many aspects, as in migration. The differences of refugees residing in Hungary and in Poland were also not addressed in the presented study results. Nonetheless, they may exist since the selection of the migration destination may depend on the administrative procedures of a particular European country, the culture or language similarity, and the distance or possibility of transportation. Moreover, we did not ask our respondents about their type of disability and the time they were disabled at the time of the interview. The limited variables related to the work environment and cultural adaptation are another limitation of this study. Additional variables could further enrich the understanding of refugees’ labor experiences. Similarly, a contextualization of labor experiences in relation to specific norms and values in Poland and Hungary, or a deeper exploration of the submission trend and its impact on the adaptation and overall well-being of Ukrainian refugees, would further enhance this study. The above are possible areas to explore and present in further research articles.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci13010014/s1, Table S1. Elements of the measuring scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.W. and D.L.; methodology, P.W., D.L. and. E.S.; software and data analysis, E.S.; validation, P.W. and D.L.; formal analysis, E.S.; investigation, P.W., D.L. and E.S.; resources, P.W. and D.L.; data curation, E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.W., D.L. and E.S.; writing—review and editing, D.L. and E.S.; visualization, P.W., D.L. and E.S.; supervision, P.W.; project administration, P.W. and D.L.; funding acquisition, P.W. and D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article and project have been supported by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange under the NAWA Intervention Grants program, grant decision number BPN/GIN/2022/1/00019/DEC/1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of: University of Krakow Rector’s Research Ethics Board (protocol code DNa.0046.1.5.2022, 28 September 2022) and of Egyesített Pszichológiai Kutatásetikai Bizottság (protocol code 2022-108, 8 October 2022) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy regulations in the University of Krakow, the dataset supporting this research is not publicly available. Nevertheless, the lead author can supply the data in response to a reasonable written request, adhering to the relevant legal and ethical standards.

Acknowledgments

The data were collected by an external contractor—Research Collective Sp. z o.o., Warsaw, Poland. The contractor transferred to the University of the National Education Commission, Krakow all the economic copyrights to the work and all its components in terms of disposing of them and using them for an indefinite period in all known fields of exploitation. The authors wish to thank Clarann Weinert for granting the permission to use the PRQ2000 scale. The authors wish to thank the Hungarian team members (Judit Kovács, Csilla Csukonyi, Karolina Eszter Kovács) from University of Debrecen, Institute of Psychology, who participated in the NAWA Intervention Grants program (BPN/GIN/2022/1/00019/DEC/1), for consultation the psychological scales used in the questionnaire, including the ones listed in this manuscript: PRQ2000, Rosenberg Self-Evaluation Scale.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams, Gary A., Lynda A. King, and Daniel W. King. 1996. Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work–family conflict with job and life satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology 81: 411–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaymak, Guliz. 2017. A Bourdieuian Analysis of Job Search Experiences of Immigrants in Canada. Journal of International Migration and Integration 18: 657–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akresh, I. Redstone. 2006. Occupational Mobility among Legal Immigrants to the United States. International Migration Review 40: 854–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvaro, José L., Alicia Garrido, Cícero R. Pereira, Ana R. Torres, and Sabrina C. Barros. 2019. Unemployment, self-esteem, and depression: Differences between men and women. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 22: E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annor, Francis. 2013. Managing work and family demands: The perspectives of employed parents in Ghana. In Work–Family Interface in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and Responses. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Jacob N. 2022. Labor market effects of a work-first policy for refugees. Journal of Population Economics 35: 169–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnert, Leonid V. 2018. Refugee resettlement, redistribution and Growth. European Journal of Political Economy 54: 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakanauskienė, Irena, Lina Žalpytė, and Justina Vaikasienė. 2014. Employer’s attractiveness: Employees’ expectations vs. reality in Lithuania. Human Resources Management and Ergonomics 8: 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, Arnold B., Evangelia Demerouti, and Maureen F. Dollard. 2008. How job demands affect partners’ experience of exhaustion: Integrating work-family conflict and crossover theory. Journal of Applied Psychology 93: 901–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Linda, Jacob Dagevos, and Godfried Engbersen. 2017. Explaining the refugee gap: A longitudinal study on labour market participation of refugees in the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43: 1775–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbis, Lara E. 1995. The Relationship of Hope, Self-Esteem, Perceived Social Support and Disability in Persons Who Have Multiple Sclerosis. Gainesville: University of Florida College of Nursing. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, Benjamin E., Sorin Valcea, Tracy H. Porter, and Vickie C. Gallagher. 2018. Survival, expectations, and employment: An inquiry of refugees and immigrants to the United States. Journal of Vocational Behavior 105: 102–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranik, Lisa E., Carrie S. Hurst, and Lillian T. Eby. 2018. The stigma of being a refugee: A mixed-method study of refugees’ experiences of vocational stress. Journal of Vocational Behavior 105: 116–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumberg, Ben. 2014. Fit-for-Work—Or Work Fit for Disabled People? The Role of Changing Job Demands and Control in Incapacity Claims. Journal of Social Policy 43: 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, Roy F., Jennifer D. Campbell, Joachim I. Krueger, and Kathleen D. Vohs. 2003. Does High Self-Esteem Cause Better Performance, Interpersonal Success, Happiness, or Healthier Lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest 4: 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, Gary S. 1962. Investment in Human Capital: A Theoretical Analysis. Journal of Political Economy 70: 9–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Brian, Francesco Fasani, and Stephen Muchin. 2013. Crime and immigration: Evidence from large immigration waves. Review of Economics and Statistics 95: 1278–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, Sarah, and Stefan Bernhard. 2021. Gender differences in second language proficiency—Evidence from recent humanitarian migrants in Germany. Journal of Refugee Studies 35: 282–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevelander, Pieter, Fernando Mata, and Ravi Pendakur. 2019. Housing policy and employment outcomes for refugees. International Migration 57: 134–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blace, A. Nalavany, Lena W. Carawan, and Stephanie Sauber. 2015. Adults with Dyslexia, an Invisible Disability: The Mediational Role of Concealment on Perceived Family Support and Self-Esteem. The British Journal of Social Work 45: 568–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, Alice, Treasa Galvin, and Barbara Harrell-Bond. 2000. Refugee Women in Europe: Some Aspects of the Legal and Policy Dimensions. International Migration 38: 169–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerchi, Diego. 2023. Reception Operators’ Perception of the Labor Market Integration of Refugees in Light of the Social Cognitive Career Theory. Social Sciences 12: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, Kenneth A., and Kwok-fai Ting. 2000. A Tetrad Test for Causal Indicators. Psychological Methods 5: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brell, Courtney, Christian Dustmann, and Ian Preston. 2020. The labor market integration of refugee migrants in high-income countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives 34: 94–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, George W., Bernice Andrews, Tirril Harris, Zsuzsanna Adler, and Lee Bridge. 1986. Social support, self-esteem and depression. Psychological Medicine 16: 813–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brücker, Herbert, Philipp Jaschke, and Yuliya Kosyakova. 2019. Refugee Migration to Germany Revisited: Some Lessons on the Integration of Asylum Seekers. Paper presented at XXI European Conference of the fRDB on How to Manage the Refugee Crisis, Calabria, Italy, 15 June. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, Ronald M., Donald B. Fedor, John G. Veres, Danielle S. Wiese, and Shawn M. Carraher. 1998. Investigating newcomer expectations and job-related outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology 83: 452–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Barbara. 1989. A Primer of LISREL. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Campion, Emily D. 2018. The career adaptive refugee: Exploring the structural and personal barriers to refugee resettlement. Journal of Vocational Behavior 105: 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Chu-Hsiang, D. Lance Ferris, Russell E. Johnson, Christopher C. Rosen, and James A. Tan. 2012. Core self-evaluations: A review and evaluation of the literature. Journal of Management 38: 81–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, Karen. 2001. Time to work: Job search strategies and commute time for women on welfare in San Francisco. Journal of Urban Affairs 23: 155–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Sin Yi, and Jenny Phillimore. 2014. Refugees, Social Capital, and Labour Market Integration in the UK. Sociology 48: 518–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Sin Yi, and Jenny Phillimore. 2017. Gender and refugee integration: A quantitative analysis of integration and social policy outcomes. Journal of Social Policy 46: 211–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Chun-Fang, and SooCheong S. Jang. 2008. An expectancy theory model for hotel employee motivation. International Journal of Hospitality Management 27: 313–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiswick, Barry R., Yew Liang Lee, and Paul W. Miller. 2005. A Longitudinal Analysis of Immigrant Occupational Mobility: A Test of the Immigrant Assimilation Hypothesis. International Migration Review 39: 332–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Chung, and Marjorie L. Baldwin. 2017. Duration of disability, job mismatch and employment outcomes. Applied Economics 49: 1001–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, Kim, and Stuart C. Carr. 2005. Skilled Immigrants and Selection Bias: A Theory-Based Field Study from New Zealand. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 29: 577–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Sheldon. 1992. Stress, social support, and disorder. In The Meaning and Measurement of Social Support. Edited by O. F. Veiel Hans and Urs Baumann. New York: Hemisphere Press, pp. 109–24. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, Greville, and Bernard Comrie. 1993. The Slavonic Languages. Oxton: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Coron, Clotilde, and Emmanuelle Garbe. 2023. Deviation from the ideal worker norm and lower career success expectations: A “men’s issue” too? Journal of Vocational Behavior 144: 103892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Velez, Ignacio, Sandra M. Gifford, and Celia McMichael. 2015. The persistence of predictors of wellbeing among refugee youth eight years after resettlement in Melbourne, Australia. Social Science and Medicine 142: 163–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, Kalena E. 2004. Are refugees different from economic immigrants? Some empirical evidence on the heterogeneity of immigrant groups in the United States. Review of Economics and Statistics 86: 465–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cott, Cheryl A., Monique A. Gigna, and Elizabeth M. Badley. 1999. Determinants of self rated health for Canadians with chronic disease and disability. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 53: 731–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Araujo, Pedro, and Stephen Lagos. 2013. Self-esteem, education, and wages revisited. Journal of Economic Psychology 34: 120–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Voretz, Don J., Sergiy Pivnenko, and Morton Beiser. 2004. The Economic Experiences of Refugees in Canada. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=526022 (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- de Vroome, Thomas, and Frank van Tubergen. 2010. The Employment Experience of Refugees in the Netherlands. International Migration Review 44: 376–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickstein, Ellen B., and Joanne M. Posner. 1978. Self-Esteem and Relationship with Parents. The Journal of Genetic Psychology 133: 273–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duleep, Harriet O., and Mark C. Regets. 1999. Immigrants and human-capital investment. American Economic Review 89: 186–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dustmann, Christian, Francesco Fasani, Tommaso Frattini, Luigi Minale, and Uta Schönberg. 2017. On the economics and politics of refugee migration. Economic Policy 32: 497–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghaziri, Nahema, and Joëlle Darwiche. 2018. Adult self-esteem and family relationships: A literature review. Swiss Journal of Psychology 77: 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasani, Francesco, Tommaso Frattini, and Luigi Minale. 2022. (The Struggle for) Refugee integration into the labour market: Evidence from Europe. Journal of Economic Geography 22: 351–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedrigo, Laurence, Marine Cerantola, Caroline E. Frésard, and Jonas Masdonati. 2023. Refugees’ Meaning of Work: A Qualitative Investigation of Work Purposes and Expectations. Journal of Career Development 50: 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-García, Edna C., Juan J. García-Machado, and Diana C. Pérez-Bustamante Yábar. 2018. Modeling the Social Factors That Determine Sustainable Consumption Behavior in the Community of Madrid. Sustainability 10: 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinsky, Ellen, James T. Bond, and Dana E. Friedman. 1996. The role of employers in addressing the needs of employed parents. Journal of Social Issues 52: 111–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gericke, Dina, Anne Burmeister, Jil Löwe, Jürgen Deller, and Leena Pundt. 2018. How do refugees use their social capital for successful labor market integration? An exploratory analysis in Germany. Journal of Vocational Behavior 105: 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gërxhani, Klarita, and Yuliya Kosyakova. 2020. The Effect of Social Networks on Migrants’ Labor Market Integration: A Natural Experiment. IAB-Discussion Paper 202003. Nürnberg: Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (IAB) [Nuremberg: Institute for Employment Research]. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, Arthur H., Jonathan R. Veum, and William Darity Jr. 1997a. The impact of psychological and human capital on wages. Economic Inquiry 35: 815–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, Arthur H., JonathanR. Veum, and William Darity Jr. 1997b. Unemployment, joblessness, psychological well-being and self-esteem: Theory and evidence. The Journal of Socio-Economics 26: 133–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey H., Claudene Seidel, and Michael Marinis. 1983. The impact of expectations and values on job attitudes. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 31: 394–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jr., Tomas Hult, Christian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2017. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Michelle A., Andrea E. Gruenenfelder-Steiger, Emilio Ferrer, M. Brent Donnellan, Mathias Allemand, Helmut Fend, Rand D. Conger, and Kali H. Trzesniewski. 2015. Do par-ents foster self-esteem? Testing the prospective impact of parent closeness on adolescent self-esteem. Child Development 86: 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, Jean F. 1980. The impact of unemployment upon the self-esteem of managers. Journal of Occupational Psychology 53: 147–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, Jörg, and Jan-Philip Steinmann. 2021. Do gender-role values matter? Explaining new refugee women’s social contact in Germany. International Migration Review 55: 688–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henle, Christine A., and Michael A. Gross. 2014. What Have I Done to Deserve This? Effects of Employee Personality and Emotion on Abusive Supervision. Journal of Business Ethics 122: 461–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii-Kuntz, Masako, and Marilyn Ihinger-Tallman. 1991. The Subjective Well-Being of Parents. Journal of Family Issues 12: 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Nazrul, Suntu K. Ghosh, Anilka Islam, Neesha M. Salam, Tanvir Khosru, and Abdullah Al Masud. 2017. Working Conditions and Lives of Female Readymade Garment Workers in Bangladesh. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2921867 (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Jackson, Samantha, and Harald Bauder. 2014. Neither temporary, nor permanent: The precarious employment experiences of refugee claimants in Canada. Journal of Refugee Studies 27: 360–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, Gun, and Ingvar Lundberg. 2004. Adjustment latitude and attendance requirements as determinants of sickness absence or attendance. Empirical tests of the illness flexibility model. Social Science and Medicine 58: 1857–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, Phillip M., Dejun T. Kong, and Kyoung Y. Kim. 2021. Social support at work: An integrative review. Journal of Organizational Behavior 42: 229–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, Danièle. 2016. Haven or Hell?: Asylum Policies and Refugees in Europe. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Joly, Danièle, Lynette Kelly, and Clive Nettleton. 1997. Refugees in Europe: The Hostile New Agenda. London: Minority Rights Group. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, Timothy A., Edwin A. Locke, and Cathy C. Durham. 1997. The dispositional causes of job satisfaction: A core evaluations approach. Research in Organizational Behavior 19: 151–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, John D., Timothy A. Judge, and Ronald F. Piccolo. 2008. Self-esteem and extrinsic career success: Test of a dynamic model. Applied Psychology 57: 204–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanas, Agnieszka, and Stephanie Steinmetz. 2021. Economic outcomes of immigrants with different migration motives: The role of labour market policies. European Sociological Review 37: 449–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Harmeet. 2021. Fetishized, Sexualized and Marginalized, Asian Women Are Uniquely Vulnerable to Violence. CNN. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2021/03/17/us/asian-women-misogyny-spa-shootings-trnd/index.html (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Kluemper, Donald H., Kevin W. Mossholder, Dan Ispas, Mark N. Bing, Dragos Iliescu, and Alexandra Ilie. 2019. When Core Self-Evaluations Influence Employees’ Deviant Reactions to Abusive Supervision: The Moderating Role of Cognitive Ability. Journal of Business Ethics 159: 435–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knabe, Andreas, and Steffen Rätzel. 2010. Better an insecure job than no job at all? Unemployment, job insecurity and subjective wellbeing. Economics Bulletin 30: 2486–94. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinov, Vsevolod, Alexander Reznik, and Richard Isralowitz. 2023. The impact of the Russian–Ukrainian war and relocation on civilian refugees. Journal of Loss and Trauma 28: 267–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosyakova, Yuliya, and Irena Kogan. 2022. Labor market situation of refugees in Europe: The role of individual and contextual factors. Frontiers in Political Science 4: 977764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Judit, Csilla Csukonyi, Karolina E. Kovács, Damian Liszka, and Paweł Walawender. 2023. Kovács, Judit, Csilla Csukonyi, Karolina E. Kovács, Damian Liszka, and Paweł Walawender. 2023. Integrative attitudes of Ukrainian war refugees in two neighboring European countries (Poland and Hungary) in connection with posttraumatic stress symptoms and social support. Front. Public Health 11: 1256102. [Google Scholar]

- Koyama, Jill. 2023. Fabricating and positioning refugees as workers in the United States. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, Robert V., and Daryle W. Morgan. 1970. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement 30: 607–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristen, Cornelia, and Julian Seuring. 2021. Destination-language acquisition of recently arrived immigrants: Do refugees differ from other immigrants? The Journal of Educational Research 13: 128–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuster, Farah, Ulrich Orth, and Laurenz L. Meier. 2013. High Self-Esteem Prospectively Predicts Better Work Conditions and Outcomes. Social Psychological and Personality Science 4: 668–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, K. Navjot. 2003. The employment experiences of Canadian refugees: Measuring the impact of human and social capital o quality of employment. Canadian Review of Sociology 40: 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lance, Charles E., Robert J. Vandenberg, and Robin M. Self. 2000. Latent Growth Models of Individual Change: The Case of Newcom-er Adjustment. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes 83: 107–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jun Y., Maya Patel, and Katrina Scior. 2023. Self-esteem and its relationship with depression and anxiety in adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic literature review. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 67: 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Li, and Dennis Moore. 1998. Acceptance of Disability and its Correlates. The Journal of Social Psychology 138: 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, Samantha. 2015. Job Expectations of Employees in the Millennial Generation. Doctoral dissertation, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Liszka, Damian, and Paweł Walawender. 2019. Cross-Sectoral Cooperation Toward a Work-Life Balance. HSS 26: 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, Edwin A. 1976. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Edited by Marvin D. Dunnette. Chicago: Rand McNally, pp. 1297–349. [Google Scholar]

- Lundborg, Per. 2013. Refugees’ Employment Integration in Sweden: Cultural Distance and Labor Market Performance. Review of International Economics 21: 219–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddy, Luther M., III, John G. Cannon, and Eric J. Lichtenberger. 2015. The effects of social support on self-esteem, self-efficacy, and job search efficacy in the unemployed. Journal of Employment Counseling 52: 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maden, Ceyda, Hakan Ozcelik, and Gaye Karacay. 2016. Exploring employees’ responses to unmet job expectations: The moderating role of future job expectations and efficacy beliefs. Personnel Review 45: 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, Debra A., Steve W. Kozlowski, Georgia T. Chao, and Philip D. Gardner. 1995. A longitudinal investigation of newcomer ex-pectations, early socialization outcomes, and the moderating effects of role development factors. Journal of Applied Psychology 80: 418–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwarimba, Edward, Miriam J. Stewart, Morton Beiser, Anne Neufeld, Laura Simich, and Denise Spitzer. 2010. Social support and health: Immigrants’ and refugees’ perspectives. Diversity and Equality in Health and Care 7: 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid, Ronald W., Malcolm Greig, and John Adams. 2001. Unemployed job seeker attitudes towards potential travel-to-work times. Growth and Change 32: 355–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, Mumtaz Ali, Hiram Ting, Jun-Hwa Cheah, Ramayah Thurasamy, Francis Chuah, and Tat H. Cham. 2020. Sample size for survey research: Review and recommendations. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling 4: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menaghan, Elizabeth G. 1989. Psychological Well-Being Among Parents and Nonparents: The Importance of Normative Expectedness. Journal of Family Issues 10: 547–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negraia, Daniela V., and Jennifer M. Augustine. 2020. Unpacking the parenting well-being gap: The role of dynamic features of daily life across broader social contexts. Social Psychology Quarterly 83: 207–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]