Abstract

The regulation of occupations such as aviation pilots can result in their facing the shock of losing their medical certification and thus, their license to work. What are the issues that these former pilots face upon losing their medical certification? The key issues may take the form of protean career characteristics and mechanisms such as identity, adaptability, and agency, which may help the individuals match to a new occupational environment. The method of convergent interviewing is used to inductively acquire the key common issues that arise when pilots lose their medical certification in Australia. The results indicate that the clarity and strength of the pilots’ sense of occupational identity may amplify the impact of the shock when that career is denied to them. The findings highlight the importance of adaptability, although the reliance on adaptability varies depending on the pathway chosen to respond to the shock. Those in situations with less adaptability, agency, or support may be most in need of career and mental health counseling. Support and adaptability may be particularly important for those facing career shocks in occupations with substantial investments in their career identity.

1. Introduction

The initial responses to the COVID19 pandemic have led to many individuals assessing alternatives to their occupations. For example, the dramatic reduction in the number of flights during 2020 and 2021 left many pilots looking for work in other fields, highlighting the role of career adaptability. A specific example of the need for such adaptability, particularly for pilots, has always been present, due to the requirement that pilots maintain medical certification in order to retain their pilot’s license.

Aviation is a highly safety focused industry, in which pilots are required to undergo stringent medical examinations on a yearly basis to ensure that no health issues have developed that could be detrimental to safe flying operations (Alaminos-Torres et al. 2022). Part of the need for these medical certifications is that pilots face a variety of occupational demands that may have associations with health issues, including cardiometabolic health (e.g., the review of cardiometabolic studies of pilots by Wilson et al. 2022).

In Australia, there are several types of pilot licenses available, as regulated by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA), ranging from a recreational pilot license (RPL) that allows you to carry passengers and be pilot-in-command within 25 nautical miles (nm) of your departure point, to the private pilot license (PPL) that allows you to be pilot-in-command of private operations, to the commercial pilot license (CPL) that allows you to be pilot-in-command of some commercial operations, to the airline transport pilot license (ATPL) that allows you to be pilot-in-command in any operation, including on passenger jets (CASA 2021). There are a variety of pathways for obtaining a particular license, with those paths each requiring varying levels of theory and practice, depending on the modes of education and training undertaken, with the higher level licenses requiring far more practical time and assessment (CASA 2021).

As of 30 June 2022, there were 30,729 pilots in Australia (CASA 2022), but there is little authoritative publicly available data regarding the gender breakdown of those pilots. In Australia women make up, according to older anecdotal estimates, 3–4% of pilots overall, although survey response rates of 6.5% women (Mitchell et al. 2014) suggests that females may have slightly higher representation in the higher categories of pilot licenses (and/or are more likely to respond to surveys). That is, the piloting occupation is heavily male dominated.

In Australia, in order to exercise the privileges of an air transport pilot license, a commercial pilot license (other than balloons), a multi-crew pilot (airplane) license, a flight engineer license, or a student flight engineer license, individuals need a Class 1 medical certificate, with other pilot licenses requiring other forms of medical certification (CASA 2023a). In these cases, CASA medical staff work with Designated Aviation Medical Examiners (DAMEs) and a wide variety of medical specialists to conduct a wide variety of tests such as an eye examination, an ECG, audiogram, fasting serum lipids and fasting blood glucose, and a calculation of cardiovascular risk (CASA 2023b). Many of these tests are required for the renewal of the medical certificate at varying intervals, with the intervals often getting smaller as the individual ages.

Licensed professions represent a range of occupational groups where the mechanisms and culture associated with the profession emphasize occupation-specific resources, but access to those resources can be blocked due to the regulations empowering the requirement of those licenses (Ruggera and Erola 2022). That is, in the case of pilots who lose their license due to failing a medical certification, they are not only facing the medical issues that prevent them from being certified, but also an uncertain future, with their career identity being threatened or removed, as well as likely consequences because of that loss of license and identity. When pilots lose their medical certification, what are the issues that influence and guide their career options?

Protean Careers in Terms of Identity, Adaptability, and Agency

The bases for career theories often reflect approaches that match people to positions. Pilots experiencing loss of their medical certification face uncertain career prospects and may need to follow an approach more akin to the protean career, where the person, not the organization, is managing their careers by applying their self-direction and seeking alignment with their intrinsic values (Hall 1976).

The three mechanisms by which people can express their protean orientation in terms of protean careers are: identity awareness, adaptability, and agency (Hall et al. 2018). Identity awareness is a clear sense of one’s personal identity and values (Hall 1996), adaptability is the extent to which an individual has difficulty changing to fit new circumstances (Savickas 1997), and agency is the person’s sense of control over their career (Hall et al. 2018). The clarity and strength of the person’s identity can guide career choices (Savickas 1997) when the individual has a high level of self-awareness (Hall et al. 2018).

The protean capabilities of identity awareness and adaptability can result in successful careers when applied toward a purpose or goal. The capacity to make choices and intentionally make things happen in the world can result in proactive career behaviors (Hall et al. 2018). In applying their agency, people will be less susceptible to organizational and peer pressure by being guided by their own inner sense of direction (Hall et al. 2018).

The protean career does not necessarily imply direct behaviors, but rather a mindset that reflects freedom and choices based on personal values (Briscoe and Hall 2006). Pilots who can no longer fly for a living will need to adopt a protean attitude if they are to find fulfilment and psychological success in their new pathway.

When faced with the reality of finding a new career path, the protean approach places a greater emphasis on allowing people to successfully adapt to social, political, technological, and economic changes across multiple career life cycles (Hall 1976). Individuals require a greater level of adaptability, with protean careers characterized by the exercise of self-direction reflecting the individual’s own intrinsic values.

Adaptability is a psychosocial resource that is a combination of skills, attitudes, and behaviors that help individuals to adapt to their occupation (Mondo et al. 2021). Career adaptability is composed of concern, control, confidence, and curiosity (Savickas and Porfeli 2012) that can help individuals cope with changes and unforeseen events in their professional careers (Mondo et al. 2021). However, note that adaptability over the span of a career may present different considerations at the beginning of a career relative to the considerations that are associated with adaptability toward the end of a career (Ibert and Schmidt 2014), perhaps especially if a regulatory event terminates a career.

Major events that occur in people’s lives can have a significant impact on their career paths (Hirschi 2010). Unplanned and unexpected external events are often not accounted for within traditional career models and such career shocks are disruptive and, to some degree, usually caused by factors outside the individual’s control, triggering deliberate processing and a review of one’s career (Seibert et al. 2013). Career shocks can vary in terms of their impact and can be negative or positive (Seibert et al. 2013). Negative career shocks are events that may have a negative impact on the individual’s career and may lead the individual to believe achievement of career goals is less likely under the current course of action, which creates a career image violation (Beach and Mitchell 1987).

Furthermore, the impact of the career shocks may be particularly strong when the individuals are pursuing careers which they see as a calling, although it is acknowledged that such a calling may be technically more of a hybrid of a calling with another work orientation (Pitacho et al. 2021).

A protean approach has been suggested as a means of pursuing a career that is more akin to a calling (Dobrow and Tosti-Kharas 2011), particularly when first pursuing that career. However, in the later part of a career, adaptability in particular is important in enabling the individual to be open to a broad spectrum of opportunities, including exiting the career (Ibert and Schmidt 2014).

That is, individuals in some occupations build up their occupational identity over years of work, study, and investment and conversely, the clarity and strength of the individual’s sense of identity may have helped to guide their career choices, i.e., in becoming pilots or medical doctors (per Briscoe and Hall 2006). A strong sense of occupational identity may present extra challenges and considerations. Medical doctors have often never thought of being anything else (Turin et al. 2022), and the same is true for many pilots. Thus, a strong sense of career identity can also pose a challenge when that identity is threatened and can result in substantial consequences, including mental health impacts (Chen and Hung 2022).

In summary, the utility of protean career theory may vary due to a variety of context issues, such as the strength of the individual’s career identity, particularly for careers with substantial investments of time and resources, and those careers that are licensed by regulation. Further, the nature of adaptability may vary depending on whether the focus is general adaptability, rather than adaptability in the face of abrupt changes of circumstances. These and other context issues may modify the protean career emphasis on the individual, where other drivers may impact the degree of agency an individual may perceive and may constrain the breadth of that spectrum of opportunities that are considered.

Therefore, in order to better understand the key issues that arise when pilots lose their medical certification in Australia, this study will use a qualitative, inductive approach to derive the key common issues that influence the consequences and main options available to the individuals. The resulting issues are then considered in terms of protean career characteristics and mechanisms such as identity, including identity awareness, adaptability, and agency, as the individuals try to match to options in their environment.

2. Materials and Methods

Studies of occupational health surveillance, such as toxicology screening for drug use among pilots, have suggested that the medical screening processes vary by country in terms of whether the testing is conducted by company doctors, public officials, or other parties (Treglia et al. 2022). In the Australian context the medical examinations for pilots are conducted for the CASA by DAMEs.

A form of convergent interviewing was used to diagnose and extract the key common issues arising in the situation where pilots lose their medical certification in Australia. Convergent interviewing is an inductive, rigorous approach for studying novel topics and problems (Jepsen and Rodwell 2008), such as the issues associated with career shocks.

The convergent interviewing approach is detailed in the research of Dick (1990) and a recent, detailed outline of the processes is summarized by Thynne and Rodwell (2019), Chamberlain et al. (2022), and Thynne and Rodwell (2018). Through detailed, specific questions, the issues raised during the rounds of interviews tend to converge within a relatively short period, as opposed to the results of other more saturated interviewing styles.

The initial step in the convergent interviewing process includes the setting up of a steering committee, which tests questions with the goal of producing tight questions that do not lead the individual towards a particular issue. The convergent interviewing approach consists of rounds of interviews, typically with two interviews per round (Dick 1990). Once the question has been finalized, a potential set of interviewees is selected and listed in order of expertise in relation to the specific research question, consulting the steering committee for their opinions. The sequence of interviews was based on their degree of expertise about the specific question of interest and not on the basis of being representative of a particular population.

The initial person interviewed is the expert deemed to possess the highest level of expertise on the specific topic, followed by the second most knowledgeable, where that second person should be as different as possible in the nature of their (very high) level of expertise from the first person. The processes are repeated until a list of names, in order of the interview sequence, has been created.

All of the interviewees were experts selected because of their specific expertise regarding the focal question: when a pilot loses their medical certification, what are the issues that influence and guide their career options? The emphasis on the consequences and options available to individuals facing the loss of their medical certification and pilot’s license yielded the interviewees in the first few rounds as pilots having 20 or more years of experience and included current and former ATPL pilots, a CASA-approved doctor who conducted pilot medical examinations (DAME), and a union official with expertise regarding the medical certification process and its impact on pilots.

The interviewees were industry experts in the area of the pilot medical certification procured during the discovery stage. All of the individuals interviewed were located in Australia and were either currently or formerly employed by organizations operating in Australia. The experts came from a wide variety of perspectives from within the industry. The full set of interviewees included current and former commercial airline pilots, flight instructors in commercial instructional operations, and individuals involved in flying or training, as well as pilot union representatives in a wide array of areas, including medical and regulatory capacities. The interviewees also included DAMEs. Note that the focus of convergent interviewing is on the issues arising in common from interviewing people with expertise regarding the specific question and is not intended to be representative of an industry.

The interviews are conducted in rounds of two interviews, and at the end of each round, the issues raised by the interviewees are discussed and reviewed. Convergent interviewing reveals the key issues that are perceived to be in common regarding a situation. Therefore, issues that are mentioned by only one interviewee are not considered in the convergent process. All of the interviews across all of the rounds included the core question, with the first round particularly relying on non-directive interviewing techniques to keep the interviewees talking (Dick 1990). The analyses that occur after each round of interviews focus on the core, common issues and do not focus on any points raised by just one interviewee. Issues that the interviewees raised that were common in a round, whether or not the interviewees were in agreement regarding the issues, then becomes a focus for a probe question to be used in later rounds.

If both interviewees in a round raised and agreed regarding an issue, the researchers generated probe questions to investigate exceptions and constraints. For example, if both interviewees in a round agreed that the existence of loss of license insurance was a useful source of financial support when facing losing medical certification, then that led to the question, “When a pilot loses their medical certification, what financial options are available?” In turn, that probe question led to our discovering themes, i.e., the perception that many pilots, and especially student pilots, did not know about this type of insurance, and that only some airlines provided that insurance, whereas other pilots were covered by such insurance if they were in part of the union, with the gap arising regarding the fact that those pilots not working for an airline with this insurance, or who were not part of the union, often did not have any such insurance.

If all the interviewees in a round surface an issue, yet disagree about the nature of the issue, the researchers generated a probe question to explore why those differences may occur. For example, if both interviewees in a round mentioned that if a pilot loses their medical certification, they can get it back, but one felt that getting the certification back was quite a difficult and onerous process, whereas the other felt that regaining medical certification was (simply) a matter of working through the processes, the resulting probe question was, “What are the issues that determine how difficult it is to regain medical certification?”

Each of the following rounds of the convergent interviewing process asked the core question, along with any probe questions generated from previous rounds. The core common issues tend to converge over the rounds, mainly because the most diverse and the most expert individuals were interviewed in the earlier rounds. The interviews continue until no new issues are raised in two rounds, which, in this case, occurred quite quickly, after only 10 interviews. The interviews received ethics approval (Swinburne University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee Ref: 20226665-10564).

3. Results

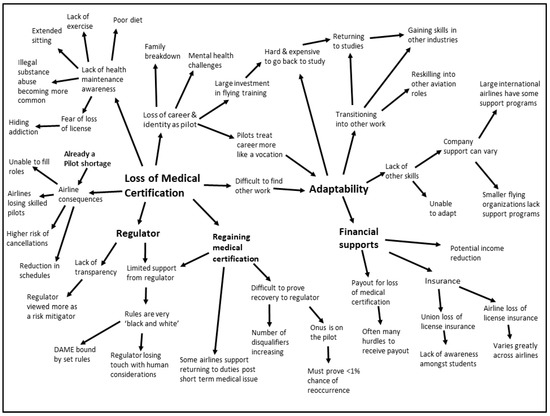

The major themes derived from the convergent interview process are issues related to loss of career, loss of income, health related issues, and links to context issues such as pilot shortages. The affinity diagram of the results is represented in Figure 1, and in addition to demonstrating the trigger/shock event, highlights the key issues pilots face when losing their medical certification. The more central issues are in a slightly larger font and are shown in bold near the center of the diagram.

Figure 1.

An affinity diagram summarizing the results from the convergent interviews.

The self-identity of the pilot was a substantial driving issue. A pilot’s job is a very niche task, with skills that are built over time from hours of practice and putting that training into practice. The strength of their identity as a pilot was a strong, consistent theme, whereas one respondent said: “Career change is hard because piloting is more a passion”.

Another theme extracted from the interviews was that there were often no direct pathways for pilots to transition into other roles within their aviation organizations. A small number of pilots are presented with the opportunity to transition into ground-based roles, including instructional roles and managerial positions; however, that was perceived to be the exception rather than the rule. The competitive nature of those positions in aviation, coupled with the academic skill sets of other candidates, can make these alternative pathways within aviation difficult to obtain. Although in the context of a pilot shortage in Australia, interviewees felt that the lack of organizational attention was odd, given that “the airlines are losing senior, highly-skilled pilots”.

In terms of alternative career paths, it was more common that the former pilots moved to other (non-aviation) industries that valued the unique skills and traits that are demonstrated by pilots, where these skills are often highly sought after, particularly in other transportation related roles. Pilots with many hours of flying often have emotional intelligence that could be relied upon, as well as instincts for a variety of situations, and this, in turn, builds good leadership and people skills. Yet, despite possessing these qualities, many of the former pilots struggle with accepting the possibility of transitioning away from flying, with many considering flying as a vocation rather than simply a job, where flying was often deeply embedded in the lifestyle of the pilots. Consequently, the former pilots faced a number of emotional and mental hurdles to overcome in order to process these changes.

There was often a lack of support for adaptation from outside the individual. A recurring issue was the lack of support given to pilots that have had medical issues, which then led to their licenses being revoked, particularly among the Australian airlines. The lack of support also occurred before the pilot lost their medical certification, with pilots facing medical challenges during their careers receiving little support or guidance in their sedentary environment during their working life. A pilot who was a member of the externally operated pilots union was far better off in terms of receiving support compared to an equivalent pilot that relied on their employing airline for support, and the services offered by employers were often deemed insufficient to provide the relevant mental, physical, and financial support to pilots.

Large international airlines were more receptive to the idea of developing pathways for former pilots who had lost their medical certification and would be more likely to aim to keep them within the airline and advance them on to another job. In contrast, as one respondent put it, “Many airlines do not have internal redeployment-you’re either a Pilot or nothing.” Thus, the level of support provided by airlines can vary significantly.

A common issue that arose was that many pilots who had lost their medical certification did not have any other pathways to follow, as they had not completed any other tertiary courses, and in the majority of cases, were of an age where they were less inclined to begin studying again and felt they had little direction in terms of a career. Pilots having completed some other degree during their time of study found it much easier to transition into another career pathway and still find the same enjoyment and self fulfilment previously provided by being a pilot. The breadth of academic background of the former pilots seemed to be a key enabler of adaptability.

The results suggest that prior to the loss of medical certification, many pilots were generally not following basic health recommendations (e.g., exercise) that were part of the syllabus from the first flight a pilot undertakes. There was also a perception of a lack of awareness among pilots regarding the availability of the union for assistance on the occasion of a medical disqualification, or even more broadly, regarding any issue pilots may face during their careers. Moreover, the lack of awareness concerning union support is compounded by a lack of awareness about loss of license insurance, an option that can serve as a lifeline for pilots facing permanent impairment in continuing their duties or transitioning to an alternate role. For example, one respondent noted that “If a pilot loses [their medical] certification what financial options are available? … Many pilots just don’t know”.

Another issue was that many pilots do not plan for the possibility of losing their medical certification and thus, do not prepare fallback plans, highlighting the importance of pilots remaining proactive throughout their career in creating adaptable qualities that greatly improve their chances of continuing a career beyond aviation. Pilots that were able to build on their training and find entrepreneurial routes beyond their disqualification were seen to have the best outcomes.

The regulator (CASA) in charge of the medical certification requirements was seen as overly-bureaucratic, with little flexibility in the rules (e.g., for illnesses that are known to be temporary or manageable once diagnosed). Pilots often felt that DAMEs took an absolute approach where, “The Medical Examiners could be too black and white, despite these conditions being able to be mitigated or managed”. Conversely, the regulators and some airlines were seen as desiring greater punishment associated with dishonesty in pilot medical consultations, arising when pilots face losing their medical viability that will affect their livelihood.

In cases where the pilots could be eligible to regain their medical certifications, the processes were seen to significantly “place the onus of proof upon the pilot” to argue to the regulator that any disqualifying cause was no longer a disqualifying impairment. Further, some of the technicalities and considerations in the procedures were seen to be obtuse or out of date and incorrect. There were examples where the regulator was using outdated data to drive their deciding factors in disqualifying a pilot’s medical approval. A common sentiment was that greater emphasis should be placed on research to create a more realistic and approachable base level for pilots to follow. Similarly, greater resources could be allocated into researching and creating more proactive guidelines to be followed in the DAME handbook, which was the final arbiter of their careers.

4. Discussion

The results above outline the core, common issues arising from the interviews of the experts associated with pilots losing their medical certification in Australia. Many of the issues raised align with protean career characteristics and mechanisms such as identity, including identity awareness, adaptability, and agency, as the individuals try to match to their environment.

The impact of the loss of identity built up over years of work, study, and investment by the pilots was substantial. The clarity and strength of the pilots’ sense of identity may have helped to guide their career choices when becoming pilots (per Briscoe and Hall 2006), but may amplify the impact of the shock when that career is denied to them. Although there is recognition that career shocks can vary in terms of their impact (Seibert et al. 2013), these findings suggest that there are occupational differences that may drive the likely degree of shock individuals face when losing their ability to work in their chosen occupation. The degree of the impact of a shock may be a function of the barriers to entry to an occupation, reflecting the amount of study and training required, as well as associated costs, and often reflecting whether the profession is licensed (per Ruggera and Erola 2022). Those in occupations with high barriers to entry, such as pilots and medical doctors, may experience a greater shock, especially when the individuals considers their careers as callings.

In terms of changing career in the face of these large, and at least initially, negative shocks, pilots who can no longer fly for a living will need to employ a protean attitude that reflects choices based on personal values if they are to find fulfilment and psychological success in their new pathways (Briscoe and Hall 2006). The importance of adaptability, the extent to which an individual has difficulty changing to fit new circumstances (Savickas 1997), varies by the pathway(s) chosen. The new circumstances can vary in terms of being a new role in the same industry, or perhaps requiring more adaptability (and/or agency), in terms of playing a new role in a new industry.

Changing occupations within the aviation industry should be straightforward, but this appears to be an uncommon pathway. Airlines could also be more proactive by facilitating a greater integration of pilots into other air operator obligations, such as flight planning, risk analysis, and route viability roles. Although there may be an initial resistance among pilots to ‘downgrade’ to these roles after the significant financial and time resources put into their careers, these subsequent and assisting roles could allow former pilots to make an ongoing contribution, leveraging their experience and skills.

Changing occupations out of the aviation industry is the path chosen or taken by most former pilots in Australia after losing their medical certifications. Although the individual-oriented shock of losing medical certification may be the focus here, the global shock of the recent COVID-19 pandemic has helped to demonstrate adaptability across pilots, aircrew, and ground staff in the aviation industry. With the substantial curtailment of flights during 2020–2021, as well as COVID-19 restrictions in place in Australia regarding flights from many parts of the world, pilots were often looking for work in other fields. Their ability to adapt to other fields only amplified the perceptions of the transferability of pilot skills, where pilots were recruited by risk analysis branches of banks to utilize their expertise, as well as the ongoing recruitment of pilots in policing roles.

Perhaps the most direct, straightforward, and instrumental enabler of adaptability in the findings was the scenario in which the former pilot had a broader background of study than only the narrower focus of training for becoming a pilot. The direction of causality of this finding may need further investigation though. For example, was the breadth of background in their studies serendipitous, or a reflection of a protean attitude back when they were choosing which pathways to take to become a pilot?

The net effect is that those pilots with high levels of career adaptability were not only prepared for being pilot, but were also more able to act when facing unforeseen events and changes to their career (supporting Mondo et al. 2021). However, the results in this study focus more on the issues that were important for adaptability at the end of their careers, reflecting differences in the nature and application of adaptability, depending upon whether the individual is entering or exiting a career (in a similar manner to Ibert and Schmidt 2014).

Across the potential pathways that these former pilots may choose from, if they have the agency, or the adaptability, the individual has the opportunity for self-reflection, planning, and deciding upon future career directions. The protean capabilities of identity awareness and adaptability can result in successful careers when applied toward a purpose or goal (Hall et al. 2018). Career counseling (e.g., Savickas et al. 2009) can help these former pilots determine their goals and life purposes in order to choose viable opportunities to become the person they want to be (Savickas 1997). The closely held identity of being a pilot may entail that some of these individuals require extra support in order to deal with that identity loss.

A pathway that receives little attention in career theory involves the issues associated with attempting to regain their occupation, in this case through regaining their medical certification. Regaining medical certification was seen to be slow, tedious, and bureaucratic. With airlines facing a shortage of pilots, it would seem that streamlining the regaining of medical certification, while still maintaining an appropriate standard of medical fitness, would be desirable—for the airlines and for the pilots. For the individuals attempting to regain their certification, that pathway may be just one of the options that they have the agency to choose (widening the choice options of Hall et al. 2018). Having a wider set of options, such as regaining certification, may also be of particular interest in occupations where maintaining one’s health is important to the role and where staying healthy can present additional difficulties, particularly in the later part of the career (Ibert and Schmidt 2014).

Future research on the nature and applications of adaptability may be particularly valuable for licensed professions, especially where the profession is often considered a calling. For example, medical doctors in a new host country will often have to spend years working to have their skills and training recognized in order to be licensed in the new country (Turin et al. 2022), just as many pilots will put tremendous efforts into trying to get their licenses back. The strong sense of identity of pilots, similar to those of immigrating medical doctors (Turin et al. 2022) or arts school based teachers (Chen and Hung 2022), may mean that a later career shock represents a substantial threat to their occupational identity, with possible mental health consequences. There are parallels between many of the issues found here for pilots and for other occupations, such as immigrating medical doctors. Former pilots can choose pathways such as regaining their certification and thus their license, changing to another role within their industry (aviation), or changing to another industry (preferably one that leverages their skills and abilities), and in circumstances with little support, they may become lost. All of these options present mental health concerns, although some pathways may involve more severe mental health concerns. Therefore, when facing career shocks, a key support can be career counseling, such as life designing (Savickas et al. 2009) and/or mental health counseling (Chen and Hung 2022). There are precedents in which career counseling interventions focusing on adaptability have had notable effects, such as in being beneficial to enhancing the adaptability of groups such as refugees (Morici et al. 2022).

Such counseling may be needed for medical doctors after immigration (per Turin et al. 2022) or as found here, for pilots losing their medical certification due to health surveillance. Other parallels between the issues facing pilots losing medical certification and immigrating medical doctors include that, given a shortage of medical doctors in many developed economies, surely streamlining the bureaucracy could be beneficial for both the intended doctors and the society as a whole. Counseling to enhance adaptability may be valuable in many settings.

For those former pilots not attempting to regain their medical certification, particularly because of potential medical limitations, those medical issues may be a further parameter to be considered when using their agency to choose a pathway. However, a subset of the former pilots will have difficulty adapting, may not receive any support, and may feel they have limited agency (essentially, the middle-right edge of Figure 1). Without counseling or some other support, that subset of former pilots seems to be cast out to blindly find their own path and may be a group at particular risk.

Perhaps it is because of groups such as those that end up fending for themselves that bodies such as relevant unions have tried to step in to the support role for pilots. However, to address the low levels of awareness of the details of support that can be provided by the union, the unions may need to increase the awareness among pilots about those support systems, as well as the existence of loss of license insurance. Another consideration is more preventative in that pilots, airlines, the regulator, and the union may wish to increase the awareness of pilots about their health and its career implications, e.g., in terms of obesity, physical exercise and the often sedentary nature of a pilot’s work, which are common causes of cardiometabolic illnesses (Treglia et al. 2022; Wilson et al. 2022), among other health issues (Alaminos-Torres et al. 2022).

Note that the findings of this study may be limited by being based in the Australian context. However, pilots face international regulation, especially for occupational health issues that may be seen to drive processes such as medical certification. Further, the method used here focuses on the main issues that the experts raised, with a different focus that the interviews to saturation method and does not aim to indicate proportions or statistics. However, the issues raised here may be useful for informing future research that seeks to determine the career pathways delineated above.

5. Conclusions

The recent impact of COVID-19 responses raised the issue of career adaptability, as many occupations had their activities curtailed. This study demonstrates that individually-specific career shocks, such as pilots losing their medical certification, can trigger a review of one’s career (Seibert et al. 2013). In tight labor markets, a protean approach to careers may facilitate individuals finding work (Savickas et al. 2009) that helps to fulfill their life purpose. A protean career attitude, especially in terms of adaptability may be particularly important for those facing career shocks in occupations with substantial investments in their career identity. Similarly, the impact of a negative career shock may be more substantial for those in careers requiring substantial investment and study.

The surveillance of pilots is justified by a mantra of ensuring safety in aviation (Alaminos-Torres et al. 2022), yet the consequences of that health surveillance are rarely considered. Perhaps of most concern from the results above is that the regulator and many of the airlines emphasize health surveillance and yet have little consideration for what happens if pilots lose their medical certification. Support processes have largely been left to the union, with some exceptions for international airlines or short-term illnesses. The result is that a large subset of the former pilots are left to fend for themselves. Although adaptability is powerful, those in situations with less adaptability or agency, or with less of a personal protean orientation, may be at risk of ill-health and/or withdrawing from work when they could yet be productive contributors to society. Applying the suggestions of Savickas et al. (2009), ongoing career management processes, along with career counseling, could lead to life designing and career building that offers the best possible assistance to individuals. Future research may wish to investigate the characteristics by occupation associated with those varying levels of impact, especially for negative shocks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.; Methodology, T.K., R.N., W.T. and J.W.; Formal analysis, J.R.; Investigation, T.K.; Writing—original draft, T.K., R.N., W.T. and J.W.; Writing—review & editing, J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Swinburne University of Technology (Human Research Ethics Committee Ref: 20226665-10564, final approval 16 August 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alaminos-Torres, Ana, Jesus R. Martínez-Álvarez, Noemi López-Ejeda, and Maria D. Marrodán-Serrano. 2022. Atherogenic risk, anthropometry, diet and physical activity in a sample of Spanish commercial airline pilots. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beach, Lee R., and Terence R. Mitchell. 1987. Image theory: Principles, goals, and plans in decision making. Acta Psychologica 66: 201–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, Jon P., and Douglas T. Hall. 2006. The interplay of boundaryless and protean careers: Combinations and implications. Journal of Vocational Behavior 69: 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASA. 2021. Pilot Career Guide. Canberra: Civil Aviation Safety Authority, Government of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- CASA. 2022. Civil Aviation Safety Authority: Annual Report 2021–2022. Canberra: Civil Aviation Safety Authority, Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- CASA. 2023a. Classes of Medical Certificate; Canberra: Civil Aviation Safety Authority, Government of Australia. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/licences-and-certificates/aviation-medicals/medical-certificates/classes-medical-certificate (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- CASA. 2023b. The Medical Certification Process; Canberra: Civil Aviation Safety Authority, Government of Australia. Available online: https://www.casa.gov.au/licences-and-certificates/aviation-medicals/medical-certificates/medical-certification-process (accessed on 7 April 2023.).

- Chamberlain, Kurt, Bethanie Storey, Jayden Brown, Scott Rayburg, John Rodwell, and Melissa Neave. 2022. Cleaning up forever chemicals in construction: Informing industry change. Sustainability 14: 2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chia-Cheng, and Chao-Hsiang Hung. 2022. Plan and then act: The moderated moderation effects of profession identity and action control for students at arts universities during the career development process. Healthcare 10: 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dick, Robert. 1990. Convergent Interviewing. Brisbane: Interchange. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrow, Shosana R., and Jennifer Tosti-Kharas. 2011. Calling: The development of a scale measure. Personnel Psychology 64: 1001–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Douglas T. 1976. Careers in Organizations. Glenview: Scott Foresman & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Douglas T. 1996. Protean careers of the 21st century. The Academy of Management Executive 10: 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Douglas T., Jeffrey Yip, and Kathryn Doiron. 2018. Protean careers at work: Self-direction and values orientation in psychological success. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 5: 129–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, Andreas. 2010. The role of chance events in the school-to-work transition: The influence of demographic, personality and career development variables. Journal of Vocational Behavior 77: 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibert, Oliver, and Suntje Schmidt. 2014. Once you are in you might need to get out: Adaptation and adaptability in volatile labor markets—The case of musical actors. Social Sciences 3: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, Denise M., and John J. Rodwell. 2008. Convergent interviewing: A qualitative diagnostic technique for researchers. Management Research News 31: 650–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Jim, Alexandra Kristovics, and Leopold P. Vermeulen. 2014. Another Empty Kitchen: Gender Issues on the Flight Deck. In Absent Aviators: Gender Issues in Aviation. Edited by Donna Bridges, Albert J. Mills and Jane Neal-Smith. London: Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 165–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mondo, Marina, Barbara Barbieri, Silvia De Simone, Flavia Bonaiuto, Luca Usai, and Mirian Agus. 2021. Measuring career adaptability in a sample of Italian university students: Psychometric properties and relations with the age, gender, and STEM/no STEM Courses. Social Sciences 10: 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morici, Roberta, Davide Massaro, Federico B. Bruno, and Diego Boerchi. 2022. Increasing refugees’ work and job search self-efficacy perceptions by developing career adaptability. Social Sciences 11: 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitacho, Liliana, Patricia J. da Parma, Pedro Correia, and Miguel P. Lopes. 2021. Why do people work? An empirical test of hybrid work orientations. Social Sciences 10: 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggera, Lucia, and Jani Erola. 2022. Licensed professionals and intergenerational big-, meso- and micro-class immobility within the upper class; social closure and gendered outcomes among Italian graduates. Social Sciences 11: 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, Mark L. 1997. Career adaptability: An integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory. The Career Development Quarterly 45: 247–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, Mark L., and Erik J. Porfeli. 2012. Career adapt-abilities scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of Vocational Behavior 80: 661–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, Mark L., Laura Nota, Jerome Rossier, Jean-Pierre Dauwalder, Maria E. Duarte, Jean Guichard, Salvatore Soresi, Raoul Van Esbroeck, and Annelies E.M. van Vianen. 2009. Life designing: A paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. Journal of Vocational Behavior 75: 239–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, Scott E., Maria L. Kraimer, Brooks C. Holtom, and Abigail J. Pierotti. 2013. Even the best laid plans sometimes go askew: Career self-management processes, career shocks, and the decision to pursue graduate education. Journal of Applied Psychology 98: 169–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thynne, Lara, and John Rodwell. 2018. A pragmatic approach to designing changes using convergent interviews: Occupational violence against paramedics as an illustration. Australian Journal of Public Administration 77: 272–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thynne, Lara, and John Rodwell. 2019. Diagnostic convergent interviewing to inform redesign toward sustainable work systems for paramedics. Sustainability 11: 3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treglia, Michele, Margherita Pallocci, Giorgio Ricciardi-Tenore, Flavio Baretti, Giovanna Bianco, Paola Castellani, Fabrizio Pizzuti, Valeria Ottaviano, Pierluigi Passalacqua, Claudio Leonardi, and et al. 2022. Policies and toxicological screenings for no drug addiction: An example from the civil aviation workforce. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turin, Tanvir C., Nashit Chowdhury, Deidre Lake, and Mohammad Z.I. Chowdhury. 2022. Labor market integration of high-skilled immigrants in Canada: Employment patterns of international medical graduates in alternative jobs. Healthcare 10: 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, Daniel, Matthew Driller, Ben Johnston, and Nicholas Gill. 2022. The Prevalence of cardiometabolic health risk factors among airline pilots: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).