Abstract

The inefficiency of states in meeting their populations’ needs poses a deterrent to citizen participation. Within this context, an inquiry into the impact of citizen laboratories on urban governance becomes pertinent. Democracy necessitates innovation to ascertain solutions by harmonizing technology, knowledge, design, planning, and the social sciences. Citizen laboratories foster this equilibrium, thereby enabling the effective exercise of popular governance. Furthermore, they empower individuals to cultivate their civic conduct grounded in five pivotal concepts: the political, the politic, the policy, the culture, and the cultural. This contributes to urban sustainability and engenders the consolidation of identity, principles, ideals, memory, and the social fabric. By means of a literature review, an examination can be undertaken guided by the foundational premises that shape the distinctive attributes of citizen laboratories. This endeavor proves valuable in extending the discourse, as authentic and unfeigned citizen involvement in decision-making processes for their communities emerges as an indispensable factor.

1. Introduction

Presently, urban residents and administrative authorities are actively exploring novel modes of collaborative engagement to address communal challenges. As far back as the 5th century BC, Athens witnessed the aristocracy experimenting with democracy, thereby fostering platforms for public participation. This innovative concept was subsequently adopted by various nations, adapting it to the unique historical circumstances of each era. The inhabitants of Comuna 5 in Medellín, Colombia, have established arenas for representation and collaboration that have effectively engaged academic institutions, private sectors, and governmental bodies. This article undertakes a comprehensive examination of the academic literature on citizen laboratories, adopting a perspective that embraces both the political and the cultural dimensions. The aim is to comprehend the intricate structure and organization of citizenship, epitomized by diverse societal actors such as social leaders, cultural stewards, activists, environmental advocates, and political figures, among others. The overarching goal is to enhance living conditions and foster harmonious coexistence within urban realms. Against this backdrop, a pivotal query emerges: What is the transformative influence of citizen laboratories as realms for cultural and political democratization in contemporary society? This exploration undeniably propels us toward a nuanced contextualization and characterization of citizen laboratories, consequently furnishing insights into the multifarious viewpoints that grapple with the present-day challenges confronting urban governance.

2. Background

During the 5th century BC, Athens pioneered the concept of democracy through the endeavors of statesmen driven by the aim of curbing aristocratic privileges and fostering the active engagement of the populace in the governance of the city-state. While the blueprint of ancient Greek democracy may not seamlessly translate to the modern milieu, certain democratic facets are reminiscent of Hellenic ideals. Notably, principles such as the selection of representatives, the delineation of powers, and the institution of popular juries now transformed into judicial entities, among others, have their origins in this era. It is imperative to acknowledge, however, that these democratic tenets have undergone evolution and adaptation to align with the realities and requisites of present-day societies, particularly those adhering to the ethos of liberal democracies (Fukuyama 1992).

In the context of medieval Europe, the democratic attributes witnessed in earlier periods underwent a decline, yielding ground to the establishment of the feudal system. This socio-economic and political framework was characterized by the dominance of landholders, referred to as feudal lords, who exercised authority over territories. In return for labor and services, they accorded protection and privileges to serfs, effectively curtailing avenues for active citizen involvement.

Conversely, the colonization of the American continent during the late 15th century brought about a paradigm where individuals of European descent assumed dominance as rulers, while native populations and slaves were positioned beneath this authority. This socio-political arrangement endured across the majority of American nations until the early 19th century. However, this historical juncture also presented a notable opening for transformation (Elazar 1998). The resulting cultural amalgamation, initially marked by tensions, eventually paved the way for fresh political and social prospects, particularly during the transition from colonial governance in America and the feudal system in Europe to the emergence of state autonomy.

In connection with this, the attainment of independence by American colonies and the establishment of modern European states during the 19th and early 20th centuries epitomize a fresh paradigm. Within numerous Western nations, democratic frameworks have been embraced and progressively honed. Thus, it can be posited that contemporary democracy, originating from nascent concepts within the Greek polis, has undergone a multifaceted evolution. It has assimilated notions and principles from an array of historical origins, often transcending the fundamental tenets of parliamentary systems (Canetti 2014).

From this vantage point, the majority of Western nations embraced this governance model, championing individual liberties and extending rights to a broader populace. Nonetheless, its evolution has not been uniform. The vulnerabilities of this system were starkly exposed by the Second World War (Polanyi 2006). As the 21st century commenced, representative democracies encountered formidable challenges (Ceballos 2018), particularly from 2008 onwards, following the economic collapse that triggered a profound re-examination of the capitalist structure. In response to this crisis, three distinct types of reactions emerged: stasis (institutions resistant to change), measured transformation (institutions gradually integrating changes for adaptation), and experimentation (the establishment of novel institutions) (Pascale and Resina 2020, p. 10).

Conversely, modern liberal democracies are characterized by conditions that render them increasingly intricate. The advancement of industrialization and the constant march of scientific progress have profoundly reshaped contemporary societies. The progressive accessibility of the internet and the interconnectedness of users have ushered in novel modes of mass communication and alternative media platforms alongside traditional outlets. Information, knowledge, and technical competencies have proliferated at an accelerated pace. Citizens are now more cognizant of their entitlements and vocal in their call for the exercise of their freedoms. Consequently, states have fortified their bureaucracies to establish institutions entrusted with addressing the evolving democratic expressions of a society (Resina 2010; Peña-López 2018).

The challenge becomes even more pronounced in a contemporary context that hampers citizen participation due to three fundamental factors. Primarily, there is the intricacy of ensuring that an array of perspectives is considered by decisionmakers, who impact the entire community. Secondly, there persists a perception that the political realm falls short in effectively addressing matters pertaining to common welfare. Lastly, there exists a lack of inclination to adopt individual stances concerning matters of public life. Consequently, the elite class retains a firm grasp on the levers of power, steering society in accordance with their inclinations while cloaked in the veneer of an ostensibly agreed-upon consensus. This phenomenon is what Crouch (2000) labels as post-democracy.

An effective resolution remains elusive, as contemporary citizens perceive the state’s inadequacy in meeting their requirements. Conventional political theory frameworks fail to furnish solutions for the novel challenges that societies presently confront. It is evident that democracy necessitates innovation to devise pragmatic solutions that increasingly hinge upon the equilibrium between technology, knowledge, design, planning, and the social sciences. Thus, it becomes imperative to explore methodologies that facilitate the involvement of a citizenry that demands transparency and efficiency from public administration (Smith 2009; Shiavo and Serra 2013; Resina 2019; Pascale and Resina 2020; Asenbaum and Hanusch 2021).

Any democratic innovation must strive to diminish the disparity between the two ends of the participation spectrum. On one pole, manipulated citizens assume a passive stance towards decisions influencing them. On the opposite end, there are individuals who adopt resolute positions on matters of public concern and wield influence over public authority (Arnstein 1969). The gulf between these factions is bridged through democratization, a process realized when citizens effectively generate and disseminate knowledge that bolsters their influence and impels them to engage proactively (Sangüesa 2013).

It is imperative to disrupt the conventional paradigm wherein governmental endeavors adhere to a top-down governance framework. Within this construct, civil servants assume primary authority over civic propositions, programs, or projects, relegating citizens to a subordinate position of mere acceptance. This approach relegates citizens to the status of the weakest element, rendering them passive recipients rather than dynamic and engaged participants. This power asymmetry stifles the public’s voice (Nguyen et al. 2022).

Within this context, innovation acts as a conduit for synthesizing expertise from corporate, academic, governmental, and community domains, facilitating the emergence of innovative and varied solutions to the complexities confronting contemporary societies (Arboleda Jaramillo et al. 2019).

In light of the aforementioned, the objective of this investigation is to assess the function of citizen laboratories as platforms cultivating community involvement and active participation, thereby advancing cultural and political democratization through collaborative arenas. To attain this objective, it is imperative to undertake a comprehensive literature review encompassing seminal scholars and scholarly articles. The latter will encapsulate the latest research elucidating concepts pertaining to the political and the cultural within the context of citizen laboratories.

3. Theoretical Context

Human endeavors are fundamentally imbued with political implications. Aristóteles’ (1986) anthropocentric viewpoint underscores that humanity is inherently political, as evidenced by his concept of “Zoon politikón” (Urmeneta and Legerén 2016), designating humans as the sole species possessing language. However, not every human endeavor occurs within the political domain, and any political undertaking necessitates adroit linguistic manipulation. Language has also been wielded for duplicitous purposes, obscuring the true intentions of power hegemony and subjugating individuals or communities. Citizens adopt roles, confront challenges, and embark upon tasks in pursuit of personal or collective interests. Each action engenders a reaction and elicits a degree of accountability, be it through action or inaction, for these endeavors. Aligned with this, five distinct concepts delineate the public conduct of individuals: the political, the politic, the policy, the culture, and the cultural.

3.1. The Political

This revolves around the agent of action, someone endowed with the capacity to enact and render judgments in response to a situation or condition, be it transitory or enduring, bearing individual or communal ramifications. In this vein, Max Weber propounds that the actor is the individual who arrives at decisions rooted in their values and ushers in a novel occurrence within a distinct milieu. The outcomes ensuing from such decisions evade precise prognostication due to the singularity of the circumstance at hand (Weber 1979).

The political realm is shaped by human actions. People engage in actions aligned with a party, a social collective, an ideology, adhering to principles, safeguarding interests, and wielding power. Essentially, individuals exhibit political dimensions across the spectrum of human existence. Francisco Giraldo-Gutiérrez asserts that this inherent political nature of humanity is demonstrated by the creation of spaces during interactions, where contemplation and deliberation on matters demanding individual and collective action occur (Giraldo-Gutiérrez 2009, p. 174).

The politician must possess the ability to comprehensively grasp and interpret their constituents across all spheres and dimensions. The effectiveness of their election and their performance as representatives of a collective—be it their own party or a broader community—is significantly contingent on this comprehension. Engaging with fellow individuals in analogous political roles facilitates the evaluation of the extent to which their obligations to ordinary citizens are fulfilled. In this context, from both a philosophical and existential standpoint, a correlation exists between self-awareness and understanding of others, between revisiting the conflicts confronted by bygone individuals and the present stance taken (Weber 1979).

For the betterment or detriment of a societal community, whether to attain personal or communal objectives or to subdue others, it becomes imperative to possess knowledge and comprehension of citizens’ actions, interests, and intentions within their contexts. The politician extrapolates their own motivations and designs onto others, stemming either from personal inclinations or through demagogic maneuvers that could potentially devolve into unlawful activities due to the disquiet within society.

Three fundamental attributes are pivotal for a politician: fervor, a profound sense of obligation, and judiciousness. Fervor encapsulates an affirmative dedication to a “cause,” an impassioned alignment with the deity or demon that steers it (Weber 1979, p. 153). Within this framework, a politician’s activities, whether via delegation, election, or representation as an agent of authority, and in the context of their actions, must be comprehensive and cohesive.

Consequently, an inquiry emerges regarding the attributes that will empower the politician to effectively shoulder the burden of that authority (however circumscribed it might be in their particular circumstance) and the ensuing responsibilities. This navigates us into the domain of ethics, for it is this field that delineates the persona one must embody to warrant the legitimacy to shape the trajectory of history (Weber 1979).

To recapitulate, the politician is required to operate congruently with their role, championing the authority and concerns of the constituency that elected them or whom they represent. As a result, the politician is engaged in a moral responsibility, a moral obligation. When undertaking the mantle of a politician, an ethical framework is embraced. Conforming to this framework (demonstrating responsibility and dedication in wielding authority) ensures that when actions are appraised, they do not fall within the realms of antagonism, autocracy, or apathy. Each exertion of power will inevitably encompass its merits and drawbacks, alongside degrees of discontent and perceptions of non-adherence.

Indeed, historical evidence underscores that achieving the attainable in this world necessitates persistent pursuit of the seemingly unattainable. However, to accomplish this feat, one must embody not only leadership but also heroism. Only those who possess the unwavering resolve to stand strong when the world, from their perspective, appears too irrational or ignoble for their offerings; only those who can counter all of this with an unwavering “however”; only an individual forged in this mold can possess the “calling” for politics (Weber 1979). Within this continuum of ideas, the politician is entrusted with the task of being tenacious and unwavering on the journey towards realizing the objectives set by the community.

3.2. The Political

This constitutes the setting or sphere of operation for an individual or a group. These spheres of operation are interrelated with what is delineated as the realms of the liberal individual. Grounded in the premise that the notion of freedom gains traction in modernity, it is presupposed that the pursuits aimed at attainment, as aspirations, are not solely centered around the individual and their personal essence. They also concurrently and contrastingly encompass the collective, that is, the individual within society (Giraldo-Gutiérrez 2009). The political assumes a role, fulfills a purpose, and is, in itself, an exercise of authority. Analogous to politics, it constitutes a theater of authority underpinned by ideals, principles, and doctrines.

The political element, therefore, encompasses not only the subject or issue that propels the politician’s conduct but also, to a significant extent, the underlying purpose, what stirs emotions, and what prompts an individual to take up a position of authority. Routinely, one engages with an ethical posture and a perspective concerning the subject, which concurrently serves as both a means and an end for the attainment of the envisaged objectives. It is due to this very rationale that “the political actions within the social interrelation of humanity, constituting civilization, are inherently ethical actions, even if some may contest the axiological significance of humanity” (Arnaiz 1999, p. 284). Confronting the political subject, the political figure bears the responsibility to act in alignment with the prerogatives of society.

The political domain possesses an expansive sphere of influence, encompassing domains such as human rights, international humanitarian law, environmental rights, and constitutional mandates. These normative frameworks facilitate the delineation of the realms within the political spectrum, extending to encompass other sentient beings and the tangible and intangible cultural aspects of territories.

3.3. Politics

Politics encompasses the subjects, domains, and fields of liberal action, as well as the philosophy and principles corresponding to a political party or association. Moreover, it defines the actions undertaken by a government or a state.

The concept of “politics” is extensive, encompassing a wide range of autonomous leadership activities. Max Weber raises the question and provides certain elements of an answer: What constitutes “politics”? It incorporates the currency policies of banks, discount policies, union policies, the school policies of a city, the policies exercised by the presidency of an association, and even the policies of a spouse endeavoring to influence their partner (Weber 1979).

As Weber elucidates, politics, as a conceptual framework, is applicable to all spheres and actions of individuals: in social, political, economic, and familial contexts. In essence, it holds true to assert that everything possesses or corresponds to a political dimension. Nonetheless, “politics entails a demanding and protracted struggle against resilient resistance; one that demands both passion and moderation simultaneously” (Weber 1979, p. 107). Moreover, those who engage in politics aspire to power as a means of achieving other ends, whether idealistic or self-serving, or simply to relish the sense of prestige it confers (Weber 1979). As the exercise of power, politics bestows upon the individual or political group that wields it social standing, acknowledgment, and economic influence.

Viewed through this lens, it can be deduced that individuals can participate in “politics” as either “occasional” politicians, as a secondary vocation, or as their primary profession (Table 1). All of us become “occasional” politicians when we cast our votes, express approval or dissent in a “political” gathering, deliver a “political” speech, or partake in any other form of assertion of our will. Presently, “semi-professional” politicians encompass those representatives and officials of political groups who generally engage in such activities as needed, without predominantly deriving their sustenance or purpose from them, both materially and spiritually (Weber 1979).

Table 1.

How to do politics: role of the subject of political action.

The suffragist, in their capacity as an intermittent politician, exercises their entitlement and duty to elect those who undertake the political profession and will assume roles of representation in governance. Through suffrage, citizens gain the chance to engage in political decision-making and shape the trajectory of their community, locality, or nation. By casting their vote, the suffragist designates the politician or contender they perceive as the most competent, reliable, and in harmony with their principles and requirements.

Politics, as the enactment of the political agent, while considering their interests, circumstances, and capabilities, evolves into an ideal within the realm of politics, its conceptual underpinnings, and its theories. In contemporary democracies, this conceptualization and operationalization, guided by normative structures, have become somewhat indistinct.

Individuals with the education and economic means to participate in politics often, in the optimal scenario, leverage their involvement to amass wealth and advance the interests of their economic and political circles. Those who lack significant wealth but possess the necessary education and capabilities to engage in politics typically rely on state compensation, rendering them susceptible to the sway of political parties, factions, and power coalitions across the domains of their interaction. Regardless of the context and sphere of political engagement, the political actor finds themselves in a precarious position, potentially bordering on illicit or unethical behaviors (such as corruption, patronage, misappropriation, and unlawful enrichment).

In both political theory and practice, transgressions can occur through acts of commission or omission. None of the scenarios detailed in the preceding analysis absolve political actions that infringe upon the fundamental rights of individuals, living entities, or systems. As Weber (1979, pp. 96–97) cautions, “whoever dedicates their life to politics must also be financially “independent”, meaning their income cannot be contingent on dedicating the entirety or a significant portion of their personal labor and thought to its attainment.” Nevertheless, throughout history, democratic systems have occasionally allowed for the potential concentration of power and the faltering fulfillment of the mandates bestowed by the majority.

3.4. Culture and the Cultural

The concept of a city surpasses its mere physical forms and structures, its economic and consumerist outputs, and its institutions, to transcend the facets of civilization that form the bedrock of the material space, transmuted into culture, since the city’s uniqueness is embedded in the existence of the human collective (Wirth 2020).

From the aforementioned perspective, contemporary cities serve not only as magnets for economic growth and prosperity but also as repositories of cultural assets, encompassing both tangible or physical elements and intangible facets like spirituality, politics, or history (Gravagnuolo et al. 2021). Drawing from this standpoint, the economic maximization that characterized industrial cities, cemented from the 19th century until the close of the 20th century, is giving way to spaces guided by new principles. It is within this context that the notion of conserving cultural heritage gains prominence, serving as a strategic partner for the tourism sector, enabling the economic optimization of a locality’s cultural assets. As a result, emerging strategies focus on harnessing the identity representations of a community, including visual and performing arts, the audiovisual realm, and literary and musical creations. Similarly, the entirety of the historical urban landscape, encompassing monuments and urban planning, becomes a viable commodity for profit.

Under this premise, cities embody intricate social ecosystems, interconnected and perpetually evolving, shaped and reshaped by the interplay of diverse interests and aspirations. Urban physical spaces serve as canvases that project and articulate historical occurrences through narratives that encapsulate collective memory (Psomadaki et al. 2019). Additionally, these spaces reflect the ongoing construction of the present moment.

A comparable viewpoint is endorsed by UNESCO, which revolves around the notion of “Living Heritage” within an urban context. The concept pertains to individuals who possess an elevated level of expertise and skills necessary for the evolution or crafting of distinct components of intangible cultural heritage (UNESCO 2019). It is important to underscore that in UNESCO member states, this designation is attributed to those who epitomize active cultural traditions. Moreover, this recognition extends to the creative aptitude of collectives, communities, and individuals residing within their respective territories.

The intricate nature of contemporary cities necessitates proficient governance that not only conserves cultural heritage but also stimulates the vibrant living heritage embodied in daily spiritual manifestations. Consequently, public policies should center on facilitating citizens’ engagement with culture. This encompasses establishing mechanisms conducive to critical, profound, and self-directed contemplation within both society and the cultural sphere. This approach facilitates progress while concurrently upholding the preservation of culture and living heritage. It also entails cultivating inclusive circumstances and subjectivities that engender initiatives addressing societal concerns (Ríos 2021, p. 180).

4. The Case of Comuna 5 in Medellín

This research is dedicated to the examination of the case of Comuna 5 in Medellín, Colombia. Since its establishment and subsequent development, the residents of this region have fortified processes of political, communal, cultural, and artistic organization. Through the establishment of participatory and representative platforms, these endeavors constitute the bedrock of democracy. They facilitate the practice of civic engagement, cultivate coexistence, endorse respect and the acknowledgment of human rights, and fortify the social fabric. This collective effort has empowered the community to foster identity anchors and memories that nurture a profound connection to the land. Additionally, various stakeholders within the city, including academia, private enterprises, and the public sector, have contributed to this domain by endorsing and reinforcing initiatives designed to meet the populace’s requirements. This collaborative approach has yielded comprehension and exploration of innovative social alternatives that enhance collaboration across diverse institutions. Citizen laboratories serve as the conduit for this collaboration. However, prior to ascertaining their practical implementation, an exhaustive theoretical exploration of the topic remains indispensable.

5. Methodology

The foundation of this dissertation derives from the research endeavor titled “Citizen Laboratories and Social Transformation Mediated by ICTD: Human Security, New Forms of Urban Tourism, ICC, and Environmental Management for Communities in Medellín.” Within this project, the implementation of Participatory Action Research (PAR) as proposed by Borda (2009) is put forth. The research employs analytical, descriptive, and qualitative methodologies, in accordance with the approach delineated by Sánchez Silva (2005). This methodological choice is underpinned by the applied and socially oriented nature of the research.

The aforementioned research project introduces multiple avenues of analysis supported by robust literary foundations. Consequently, this paper leverages theoretical viewpoints to enhance the discourse surrounding the notion of citizen laboratories. Adhering to these principles, we have integrated a total of 60 bibliographic references to provide structure to this dissertation.

Accordingly, we initiate with a literary analysis that encompasses two fundamental components. Firstly, we delve into the theoretical underpinnings offered by classical authors, whose works are inherently linked to the theme, encompassing viewpoints from sociology, political science, and urbanism. Secondly, we undertake a review of more contemporary sources, wherein a multitude of researchers contribute through articles published in specialized databases.

It is imperative to delve deeper into certain facets of this final component, given the comprehensive bibliometric analysis undertaken. This analysis was conducted on publications catalogued in the Scopus database, employing the search terms “living labs” and “city labs.” Scrutinizing historical data spanning from 1990 to April 2023 yielded a total of 2384 articles. Subsequently, the Core of Science database was harnessed to refine the selection to the most pertinent articles within the timeframe of 2012 to April 2023, resulting in a curated pool of 108 articles. Through a meticulous evaluation and examination of the distinct keywords encompassed within each text, 32 articles were discerningly chosen that align with the multifaceted themes underpinning this dissertation.

This analysis enabled the identification of works that have significantly contributed to the subject, illuminating the theories, concepts, debates, and controversies encircling city labs and their integration within local communities. Systematic documentation tracking also facilitated a comprehensive grasp of the prevalence and impact of these social innovations on various dimensions such as the cultural, political, environmental, economic, and democratic facets of the territories. Consequently, this culminated in drawing conclusions regarding the pivotal role of city labs in the advancement of democracy, cultural enrichment, and political engagement within the examined territory.

In conclusion, it is pertinent to highlight that although a majority of the referenced texts originate from the Scopus database, essential contributions from seminal authors in the field have been incorporated. Furthermore, a select number of texts have been included from local authors who, while publishing in journals or books not indexed in the Scopus database, have contributed significantly to the topic and are indexed in other regional databases.

In recapitulation, the 60 bibliographic references under scrutiny encompass a multifaceted composition: 32 emanate from the Scopus database, while an additional 20 derive from sources archived in Hispanic American repositories. Furthermore, seven references pertain to canonical authors, and one emanates from the esteemed international institution UNESCO. From a methodological standpoint, this amalgamation of diverse elements ensures a comprehensive and holistic grasp of the issue under consideration.

6. Findings

The longevity of democracy hinges on its ability to foster novel arenas for equitable and unrestricted participation. Should this capacity falter, the system’s resilience wanes (Asenbaum and Hanusch 2021). In epochs marked by impediments or curtailments on the dissemination of ideas and viewpoints for the majority, innovation becomes imperative. Nevertheless, this trajectory may prove disheartening if privileged groups exploit emerging avenues of discourse to consolidate their dominion and sway over communal assets (Pascale and Resina 2020).

The modern world has ventured into diverse avenues of democratic innovation. Expressions of popular authority have frequently materialized through citizen assemblies, and towards the close of the 20th century, participatory budgeting initiatives proliferated across various regions as endeavors to amplify the voices of those previously marginalized (Fung and Wright 2001).

The technological advancements that have surfaced in the initial two decades of the 21st century have ushered in cultural transformations. Citizens now possess a multitude of digital skills for engagement in processes and interaction with others. This shift has prompted a reconsideration of the core nature and execution of agreements within communities (Resina 2019). Consequently, laboratories have gained traction across different nations and through varied approaches. Some are socially focused, prioritizing innovation, while others are urban, political, citizen-centric, living labs, governance-oriented or centered on transformation and change. All of these models aim to foster the involvement of diverse interest groups experimenting with novel ways to contribute to the democratic resolution of societal issues (Asenbaum and Hanusch 2021).

Citizen laboratories epitomize advancements in participation and bolster democracy. Their principal contribution lies in facilitating coordination among society, the state, and the economic system to establish realms of participation. Within these spaces, citizens contribute their creativity, exchange knowledge, and collaborate with authorities in crafting policies (Pascale and Resina 2020). These initiatives entail the collaboration of dedicated individuals, officials, and academics striving to devise innovative solutions for persisting issues within communities (Asenbaum and Hanusch 2021).

The trajectory of democracy’s future hinges on a two-fold debate. Firstly, there is a pressing need to uncover novel avenues of participation. Secondly, there is a discussion about governance carried out by specialized elites within public administration. Laboratories find themselves at an intermediary point, potentially holding promise for the future of popular governance. Nonetheless, these innovations also carry the risk of being co-opted by dominant powers and of potentially diminishing individuals’ enthusiasm to voice their opinions on matters of public significance (Asenbaum and Hanusch 2021).

6.1. Challenges for Urban Governance

In the contemporary landscape, citizens and urban policymakers across diverse nations are actively exploring novel collaborative methodologies to tackle challenges that extend beyond social concerns like poverty, inequality, and segregation (Loorbach et al. 2016; Frantzeskaki et al. 2017).

Traditional policy-oriented methods fall short of tackling the underlying origins of these intricate and enduring issues. Procedures within established urban systems lack the capability to adequately meet emerging requirements and necessities. Consequently, innovative strategies are arising to safeguard and maintain cities as thriving environments conducive to well-being, delivering a superior standard of living without exhausting finite environmental resources (Puerari et al. 2018).

Over the past decades, governmental bodies have progressively embraced diverse engagement methodologies, characterized as community-driven governance. These transformative methodologies are referred to as “third way” strategies (Rose 2000), public–private partnerships (Teisman and Klijn 2000), or public–private–people partnerships (Kuronen et al. 2010). Urban stakeholders representing distinct spheres and social strata might not inherently intersect, comprehend, or collaborate immediately. Frequently, they interact exclusively within their own social circles, occupational realms, institutional frameworks, or geographical settings (Puerari et al. 2018).

These disconnections have erected barriers to novel collaborative approaches in shaping urban futures. Some scholars assert the necessity of suitable venues and transitional spaces for collaborative modes of urban governance (Balducci 2013; Von Wirth et al. 2018). In response to these challenges, public officials, citizens, and scholars are devising and piloting diverse methods to coordinate endeavors aimed at addressing urban needs across European cities. Urban living labs (ULLs) epitomize an experimental governance model where stakeholders devise and trial fresh technologies, commodities, services, and ways of life to yield innovative solutions for challenges like climate change, urban resilience, and sustainability (Bulkeley and Castan Broto 2013). Experimentation within these laboratories is deemed an instrument for urban and territorial innovation that contributes to the sustainability of urban environments (Marsh et al. 2008; Concilio and Celino 2012).

Sustainability constitutes a significant facet of the living labs phenomenon, with numerous investigations delving into the subject (Bakıci et al. 2013). Indeed, certain reports scrutinize initiatives for innovation and development aimed at enhancing everyday life sustainably (Nyström et al. 2014). Others delve into transition labs striving for sustainable development changes (Nevens et al. 2013), the interrelation between sustainable innovation and living labs (Buhl et al. 2017), as well as the role of design, practice, and processes in effecting environmental transformation (Bulkeley et al. 2016). Furthermore, studies have explored sustainable development in smart city endeavors (Leminen and Westerlund 2017) as well as in urban development and entrepreneurship (Rodrigues and Franco 2018).

6.2. Citizen Labs in Context

The concept of citizen labs originated in the late 1990s at the MIT Media Lab, emerging from computer science scholars (Puerari et al. 2018). It draws inspiration from the theory of open innovation (Chesbrough et al. 2006), the notion of the “prosumer” as a pivotal agent within Web 2.0 era markets (Marsh et al. 2008), and the “lead user paradigm” (Von Hippel 1988). At its inception, this concept aimed to address the necessity for devising contemporary approaches to integrate work within novel technological landscapes.

Citizen labs have evolved into spaces of participation and collaboration that consolidate identity, principles, and ideals, while also preserving the cultural memory of communities and enhancing social cohesion. They additionally serve as platforms for individual and collective political engagement. These labs are conceived as geographically integrated environments shaped by their context, where a range of actors with diverse interests engage in research and development activities centered on user needs. They form part of an open innovation ecosystem composed of organizations aiming to experiment and learn within specific locales, such as cities or neighborhoods (Von Wirth et al. 2018; Voytenko et al. 2016). Citizen labs can emerge through collaborations established for exploratory purposes or can originate from novel forms of urban activism, including endeavors by social entrepreneurs, civic volunteers, or grassroots initiatives (Puerari et al. 2018).

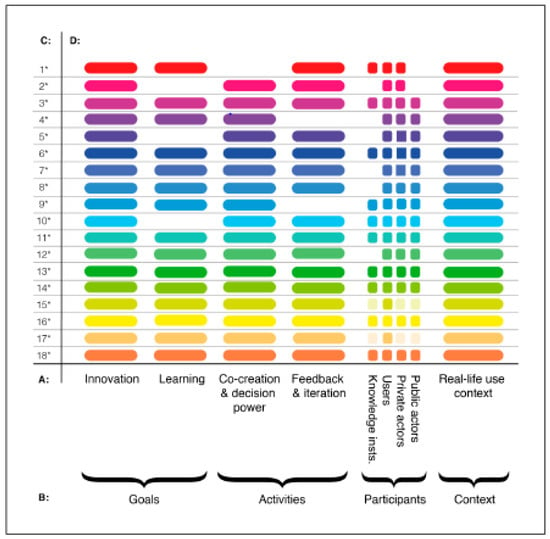

Drawing from the preceding overview (Figure 1), it is of significance to highlight that a citizen lab manifests as a collaborative arena wherein diverse public and private entities converge with the shared objective of cultivating innovation, learning, and co-creation. Within this context, an emphasis is placed on the active engagement of users, who contribute their knowledge and expertise to address specific challenges within authentic settings. Decision-making is steered towards consensus, taking into account the varied viewpoints of participants, encompassing both public and private stakeholders, in addition to the general users. These environments foster interaction and discourse to cultivate novel insights among the array of involved actors, facilitating an exchange of ideas and the collaborative forging of solutions. Through this cooperative progression, the aspiration is to engender inventive responses that are finely attuned to the requisites and concerns of the community, whose experiences are deeply rooted in tangible spaces of everyday life.

Figure 1.

Characteristics that define citizen laboratories and authors who address their approaches. A = Proposed defining characteristics of citizen laboratories. B = Dimensions applicable to the defining characteristics. C = The definitions of citizen laboratories provided in the literature. D = Presence of the defining characteristics proposed in the definitions of citizen laboratories provided in the literature. Source: Reprinted with permission from Steen and Van Bueren (2017). Characteristics of the living labs associated with their dimensions according to the most relevant literature.

In delineating the concept of a citizen lab, it becomes apparent that there exist various configurational components interlinked with the distinct attributes, typologies, resultant advantages, and activities that transpire within these collaborative creation spheres. As depicted in Table 2, these configurational elements exhibit a pervasive presence across diverse viewpoints, encompassing dimensions like innovation, learning paradigms, co-creation methodologies, decision-making modalities, and interaction strategies. It is imperative to acknowledge that these perspectives may undergo modification contingent upon the context and the precise objectives inherent to each individual citizen lab.

Table 2.

Different perspectives to define a citizen laboratory.

Table 3 outlines the objectives of citizen labs, centering on the pursuit of innovative and sustainable resolutions for urban predicaments. The activities undertaken are marked by their diversity and adaptability, fostering collaborative creation among assorted stakeholders who collaborate in tasks encompassing predicament recognition, idea formulation, solution delineation, and project execution, thereby facilitating constructive iteration.

Table 3.

Characteristics of citizen laboratories: features based on four fundamental aspects.

Moreover, contributors within citizen labs exhibit a rich diversity, a facet that precisely cultivates co-creation and the origination of solutions that are more holistic and attuned to the context. It is crucial to underscore that the locale in which citizen labs unfold is the urban milieu, as they grapple with challenges encountered by communities, all while meticulously accounting for distinct social, economic, and environmental nuances.

Similarly to the aforementioned, Aquilué et al. (2021) delineate four principal attributes of a citizen lab. (Table 4) Firstly, it embodies an objective centered on innovation, knowledge advancement, and heightened urban sustainability. Secondly, it conducts initiatives arising from inventive development, facilitating co-creation and iterative processes among diverse actors. Thirdly, its context is firmly rooted in authentic, real-world scenarios. Lastly, the composition of participants encompasses users, both private and public entities, as well as knowledge institutions.

Table 4.

Model with elements associated with the characteristics and strategic, civic, and organic components of a citizen laboratory.

The studies examining the primary attributes of a citizen lab do not deviate from these aspects.

A citizen lab is marked by the involvement of various actors assuming strategic, civic, and organic functions in its establishment. From a strategic standpoint, primary contributors often encompass innovation agencies, national governments, and corporate enterprises. On the civic front, key participants involve municipal and local governments, authorities, higher education institutions, research centers, local enterprises, and SMEs. These actors collectively shape the urban landscape as a contingent and historically evolved phenomenon within their specific milieu.

In the organic dimension, civil society, communities, NGOs, and the populace assume a pivotal role in the citizen lab. These stakeholders interpret the urban landscape through their unique perspectives and experiences, shaping the approach to tackling challenges and devising solutions. Communities are approached from the vantage points of social, economic, and environmental considerations, with diverse forms of community organization evident at both micro and individual levels.

7. Conclusions

Democracy represents a social innovation that different nations have adopted in accordance with their distinct circumstances. This has provided individuals with a platform to shape their civic conduct grounded in notions of the political, politicians, politics, culture, and cultural facets. The progression of technology across time has introduced alterations in the practice of popular governance. The present task lies in achieving a balance among society, the government, the economic structure, and academia to establish arenas of participation that facilitate proficient responses to community needs. The array of authors surveyed in this study elucidate that citizen labs streamline collaboration among these stakeholders to ensure equitable decision-making authority for all.

To attain this objective, four prerequisites need to be fulfilled. Firstly, there must be a well-defined objective encompassing innovation, knowledge enrichment, and enhanced urban sustainability. Secondly, there should be an ongoing process of experimentation and co-creation involving various stakeholders. Thirdly, the actual context must be considered, which entails the presence of a particular region and tangible challenges that demand resolutions. Lastly, a diverse array of participants must be integrated, comprising users, knowledge institutions, as well as private and public entities.

Within these processes of social innovation, three categories of collaborators come to the forefront. The first group encompasses strategic partners, encompassing national governments and corporate enterprises. These actors assume the responsibility of delineating investment and innovation priorities. Following suit are the civic participants, incorporating municipal authorities, academic institutions, and local businesses or industries. Their focus extends towards economic matters and the creation and propagation of knowledge. The final facet of citizen labs is the organic element, comprising civil society, communities, NGOs, and the broader population. They are primarily invested in matters related to coexistence, mobility, education, health, economy, environment, or novel entrepreneurial avenues.

As a reaction to the social and environmental complexities within cities, novel collaborative strategies in urban governance have been under exploration. Conventional policy-driven methods have demonstrated inadequacy in tackling the underlying and enduring problems within urban domains. The significance of citizen participation and governance enacted through community involvement has grown progressively. Nevertheless, obstacles and disjunctions endure among distinct urban stakeholders, impeding the realization of collaborative strategies. In this setting, citizen labs possess the potential to cultivate an experimental mode of governance, enabling stakeholders to trial new technologies, products, and services to discover inventive resolutions for urban predicaments.

Adopting a comprehensive viewpoint, one can deduce that citizen labs, conceived as arenas for cultural and political democratization, wield substantial influence in the realms of political science, urban governance, and citizen engagement, thereby amplifying the comprehension of participatory democracy. From this perspective, citizen labs stand as instances of democratic innovation that nurture citizen involvement and cooperation in decision-making processes. A study concentrated on these labs has the potential to enhance our comprehension of how mechanisms of citizen participation within contemporary democracy can be broadened and fortified. It can delve into how citizen labs facilitate more equitable and unrestricted engagement and explore their ramifications on political decision-making.

This dissertation holds the potential to enrich forthcoming scholarly inquiries by offering a theoretical extension of the role of citizen labs as domains fostering cultural and political democratization within governance and citizen engagement. In doing so, it broadens the vista of comprehension concerning the impediments and obstacles encountered in the execution of participatory strategies. Moreover, the discourse remains unsettled, beckoning the juxtaposition and distinction of diverse methodologies and viewpoints in decision-making originating from local communities.

In summation, it becomes imperative to revisit the questions raised by Henri Lefebvre in his seminal work “The Right to the City,” alongside the concerns articulated by Ion Martínez and Manuel Delgado in their introductory presentation to this discourse. These inquiries probe the intricate terrain of citizen participation within urban decision-making, a terrain often rife with duplicity and ambiguity as replicated by participation models often perpetuated by expedient political agendas (Lefebvre 2017). In its essence, citizen participation should transcend the confines of a conventional and superficial consultative or decisional process within urban contexts, one that merely echoes the directives of those in authoritative positions: a scenario where the articulations of citizens are noted but their entreaties tend to dissipate, rendering the populace as mere “ornaments”. Lefebvre’s assertion lies in the argument that this circumscribed notion of citizen participation fails to genuinely address the aspirations and requisites of urban denizens, thus precluding the realization of authentic democracy.

Urban planning and management discover an invaluable prospect within citizen laboratories, transcending the confines of mere formal consultation and the delegation of authority to experts or officials. It is imperative that citizens possess the agency to directly impact the creation of urban spaces, the decision-making process, and the configuration of their surroundings.

The explicit delineation of the diverse collaborators engaged in citizen laboratories and the objectives they pursue culminates in the inference that the prerequisites for implementing this social innovation in Comuna 5 of Medellín are met. The scholars affiliated with the “Citizen Laboratories and Social Transformation Mediated by ICT. Human Security, New Forms of Urban Tourism, ICC, and Environmental Management for Medellín Communities” project now confront the task of formulating a framework to harmonize the participants, with the goal of fostering participation in this specific locale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L.G.G., H.D.J.T.R., C.P.L. and J.E.M.U.; methodology, F.L.G.G., H.D.J.T.R., C.P.L. and J.E.M.U.; investigation, F.L.G.G., H.D.J.T.R., C.P.L. and J.E.M.U.; resources F.L.G.G., H.D.J.T.R., C.P.L. and J.E.M.U.; F.L.G.G., H.D.J.T.R., C.P.L. and J.E.M.U.; writing—original draft preparation, F.L.G.G., H.D.J.T.R., C.P.L. and J.E.M.U.; writing—review and editing, F.L.G.G., H.D.J.T.R., C.P.L. and J.E.M.U.; visualization, F.L.G.G., H.D.J.T.R., C.P.L. and J.E.M.U.; supervision, F.L.G.G., H.D.J.T.R., C.P.L. and J.E.M.U.; project administration, F.L.G.G., H.D.J.T.R., C.P.L. and J.E.M.U.; funding acquisition, F.L.G.G., H.D.J.T.R., C.P.L. and J.E.M.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Laboratorios Ciudadanos y Transformación Social: Laboratorios Ciudadanos y Transformación Social Mediada por TICD. Seguridad Humana, Nuevas Formas de Turismo Urbano, ICC y Gestión Ambiental para Comunidades de Medellín] grant number [1211].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aquilué, Inés, Angélica Caicedo, Joan Moreno, Miquel Estrada, and Laia Pagès. 2021. A Methodology for Assessing the Impact of Living Labs on Urban Design: The Case of the Furnish Project. Sustainability 13: 4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboleda Jaramillo, Carlos Augusto, Juan Manuel Montes Hincapié, Carlos Mario Correa Cadavid, and Claudia Milena Arias Arciniegas. 2019. Laboratorios de innovación social como estrategia para el fortalecimiento de la participación ciudadana. Revista de Ciencias Sociales (RCS) XXI: 130–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristóteles. 1986. Obras, La Política. Aguilar (Colección Grandes Culturas). Madrid: Primera Edición, p. 1166. ISBN 84-03-01027-3. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaiz, Aurora A. 1999. Ciencia Política. Estudio Doctrinario de sus Instituciones. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 744p. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, Sherry. 1969. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35: 216–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asenbaum, Hans, and Frederic Hanusch. 2021. (De)futuring democracy: Labs, playgrounds and ateliers as democratic innovations. Futures 134: 102836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakıci, Tuba, Esteve Almirall, and Jonathan Wareham. 2013. A smart city initiative: The case of Barcelona. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 4: 135–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, Alessandro. 2013. “Trading Zone”: A Useful Concept for Some Planning Dilemmas. In Urban Planning as a Trading Zone. Edited by Alessandro Balducci and Raine Mäntysalo. Dordrecht: Springer Science and Business Media, p. 23. ISBN 9789400758537. [Google Scholar]

- Borda, Orlando Fals. 2009. La investigación acción en convergencias disciplinarias. Revista Paca. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhl, Johannes, Justus von Geibler, Laura Echternacht, and Moritz Linder. 2017. Rebound effects in Living Labs: Opportunities for monitoring and mitigating respending and time use effects in user integrated innovation design. Journal of Cleaner Production 151: 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, Harriet, and Vanesa Castán Broto. 2013. Government by experiment? Global cities and the governing of climate change. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38: 361–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, Harriet, Lars Coenen, Niki Frantzeskaki, Christian Hartmann, Annica Kronsell, Lindsay Mai, Simon Marvin, Kes McCormick, Frank van Steenbergen, and Yuliya Voytenko Palgan. 2016. Urban living labs: Governing urban sustainability transitions. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 22: 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canetti, Elias. 2014. Masa y Poder. Obra Completa 1. Barcelona: DeBolsillo. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos, Dardo. 2018. La era de la colaboración. In Abrir Instituciones Desde Dentro. Edited by Eduardo Traid, Susana Barriga, Beatriz Palacios, Jesús Isarre and Raúl Oliván. Zaragoza: Abrir Instituciones Desde Dentro, pp. 145–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, Henry, Win Vanhaverbeke, and Joel West, eds. 2006. Innovación Abierta: Investigando un Nuevo Paradigma. New York: Prensa de la universidad de Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Chronéer, Diana, Anna Ståhlbröst, and Abdolrasoul Habibipour. 2019. Urban living labs: Towards an integrated understanding of their key components. Technology Innovation Management Review 9: 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concilio, Gracia, and Adèle Celino. 2012. Learning and Innovation in Living Lab environments. In Knowledge, Innovation and Sustainability. Integrating Micro & Macro Perspectives. Edited by Giovanni Schiuma, J.-C. Spender and Tan Yigitcanlar. Matera: IKAM. ISBN 9788896687086. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, Colin. 2000. Coping with Post-Democracy. Fabian Ideas 598. London: Fabian Society. [Google Scholar]

- Elazar, Daniel. 1998. Covenant and Constitutionalism: The Great Frontier and the Matrix of Federal Democracy. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Frantzeskaki, Niki, Vanesa Castán Broto, Lars Coenen, and Derk Loorbach, eds. 2017. Urban Sustainability Transitions: The Dynamic and Opportunities of Sustainability Transitions in Cities. In Urban Sustainability Transition. New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0-415-78418-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, Archon, and Erik Olin Wright. 2001. Deepening democracy: Institutional innovations in empowered participatory governance. Politics & Society 29: 5–41. [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo-Gutiérrez, Francisco. 2009. Aproximaciones Filosóficas Para una Democracia Liberal. Fondo Editorial ITM, Colección Arte y Humanidades. Medellín. 200p. Available online: https://repositorio.itm.edu.co/handle/20.500.12622/1765?show=full (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Gravagnuolo, Antonia, Luigi Fusco Girard, Karima Kourtit, and Peter Nijkamp. 2021. Adaptive re-use of urban cultural resources: Contours of circular city planning. City, Culture and Society 26: 100416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuronen, Matti, Seppo Junnila, Wisa Majamaa, and Ilka Niiranen. 2010. Public-Private-People Partnership as a way to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from residential development. The International Journal of Strategic Property Management 14: 200–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, Henry. 2017. El Derecho a la Ciudad. Madrid: Capitán Swing Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Leminen, Seppo, and Mika Westerlund. 2017. Categorization of Innovation Tools in Living Labs. Technology Innovation Management Review 7: 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, Derk, Niki Frantzeskaki, and Flor Avelino. 2016. Sustainability Transitions Research: Transforming Science and Practice for Societal Change. The Annual Review of Environment and Resources 41: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, Jesse, Paul Cunningham, and Miriam Cunningham, eds. 2008. Living Labs and Territorial Innovation. Amsterdam: IOS Press. ISBN 9781586039240. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin, Simon, Harriet Bulkeley, Lindsay Mai, Kes McCormick, and Yuliya Voytenko Palgan, eds. 2018. Urban Living Labs: Experimenting with City Futures. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nevens, Frank, Niki Frantzeskaki, Leem Gorissen, and Derk Loorbach. 2013. Urban Transition Labs: Co-creating transformative action for sustainable cities. Journal of Cleaner Production 50: 111–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Huong, Pilar Marques, and Paul Benneworth. 2022. Living labs: Challenging and changing the smart city power relations? Technological Forecasting and Social Change 183: 121866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyström, Anna-Greta, Seppo Leminen, Mika Westerlund, and Mika Kortelainen. 2014. Actor roles and role patterns influencing innovation in living labs. Industrial Marketing Management 43: 483–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascale, Pablo, and Jorge Resina. 2020. Prototipando las instituciones del futuro: El caso de los laboratorios de innovación ciudadana (Labic). Iberoamerican Journal of Development Studies 9: 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-López, Ismael. 2018. Fomento de la participación democrática no formal e informal. De la democracia de masas a las redes de la democracia. In Abrir Instituciones Desde Dentro. Zaragoza: Laboratorio de Aragón Gobierno Abierto, pp. 113–23. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, Karl. 2006. La Gran Transformación: Los Orígenes Políticos y Económicos de Nuestro Tiempo. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Psomadaki, Ofilia, Charalampos Dimoulas, George Kalliris, and Gregory Paschalidis. 2019. Digital storytelling and audience engagement in cultural heritage management: A collaborative model based on the Digital City of Thessaloniki. Journal of Cultural Heritage 36: 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerari, Emma, Jotte De Koning, Timo Von Wirth, Philip Karré, Ingrid Mulder, and Derk Loorbach. 2018. Co-creation dynamics in urban living labs. Sustainability 10: 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resina, Jorge. 2010. Ciberpolítica, redes sociales y nuevas movilizaciones en España: El impacto digital en los procesos de deliberación y participación ciudadana. Mediaciones Sociales 7: 143–64. [Google Scholar]

- Resina, Jorge. 2019. ¿Qué es y para qué sirve un Laboratorio de Innovación Ciudadana? El caso del LABICxlaPaz. Revista del CLAD Reforma y Democracia 74: 31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos, Henry de Jesús Toro. 2021. Estudio Sobre el Paisaje Urbano Histórico de La Comuna 10 La Candelaria, Centro de Medellín. Doctoral dissertation, UNED, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, Margarida, and Mário Franco. 2018. Importance of living labs in urban Entrepreneurship: A Portuguese case study. Journal of Cleaner Production 180: 780–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Nikolas. 2000. Community, Citizens, and the Third Way. American Behavioral Scientist 43: 1394–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Silva, Modesto. 2005. La Metodología en la Investigación Cualitativa. Available online: https://repositorio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/bitstream/10469/7413/1/REXTN-MS01-08-Sanchez.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Sangüesa, Ramón. 2013. La tecnocultura y su democratización: Ruido, límites y oportunidades de los. Labs. Revista CTS 8: 259–82. [Google Scholar]

- Shiavo, Ester, and Artur Serra. 2013. Laboratorios ciudadanos e innovación abierta en los sistemas CTS del siglo XXI. Una mirada desde Iberoamérica. Revista CTS 8: 115–21. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Graham. 2009. Democratic Innovations: Designing Institutions for Citizen Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steen, Kris, and Ellen Van Bueren. 2017. The defining characteristics of urban living labs. Technology Innovation Management Review 7: 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teisman, Geert, and Erik-Hans Klijn. 2000. Public-Private partnership in the European Union: Officially suspect, embraced in a daily practice. In Public-Private Partnerships. Theory and Practice in International Perspective. Edited by Stephen Osborne. New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, pp. 165–86. ISBN 0415439620. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2019. Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial. Recuperado el 3 de Noviembre de 2021. Available online: https://es.unesco.org/themes/patrimonio-cultural-inmaterial (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Urmeneta, Vicente Huici, and Andrés Dávila Legerén. 2016. Del Zoon Politikón al Zoon Elektronikón. Una reflexión sobre las condiciones de la socialidad a partir de Aristóteles. Política y Sociedad 53: 757–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hippel, Eric. 1988. The Sources of Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Von Wirth, Timo, Lea Fuenfschilling, Niki Frantzeskaki, and Lars Coenen. 2018. Impacts of urban living labs on sustainability transitions: Mechanisms and strategies for systemic change through experimentation. European Planning Studies, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Voytenko, Yuliya, Kes McCormick, James Evans, and Gabriele Schliwa. 2016. Urban living labs for sustainability and low carbon cities in Europe: Towards a research agenda. Journal of Cleaner Production 123: 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Max. 1979. El Político y el Científico. Editorial: Alianza Editorial, Madrid-España 240p. Quinta edición. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/19323146/El_politico_y_el_cientifico (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Wirth, Louis. 2020. “Urbanism as a Way of Life”: American Journal of Sociology (1938). In The City Reader. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 111–9. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).