Abstract

Children heading households (CHH) in urban informal settlements face specific vulnerabilities shaped by limitations on their opportunities and capabilities within the context of urban inequities, which affect their wellbeing. We implemented photovoice research with CHHs to explore the intersections between their vulnerabilities and the social and environmental context of Nairobi’s informal settlements. We enrolled and trained four CHHs living in two urban informal settlements—Korogocho and Viwandani—to utilise smartphones to take photos that reflected their experiences of marginalisation and what can be done to address their vulnerabilities. Further, we conducted in-depth interviews with eight more CHHs. We applied White’s wellbeing framework to analyse data. We observed intersections between the different dimensions of wellbeing, which caused the CHHs tremendous stress that affected their mental health, social interactions, school performance and attendance. Key experiences of marginalisation were lack of adequate food and nutrition, hazardous living conditions and stigma from peers due to the limited livelihood opportunities available to them. Despite the hardships, we documented resilience among CHH. Policy action is required to take action to intervene in the generational transfer of poverty, both to improve the life chances of CHHs who have inherited their parents’ marginalisation, and to prevent further transfer of vulnerabilities to their children. This calls for investing in CHHs’ capacity for sustaining livelihoods to support their current and future independence and wellbeing.

1. Introduction

1.1. Urban Informality and Vulnerability

An estimated 1 billion people, globally, live in informal urban settlements, sometimes known as slums (UN-Habitat 2020). According to Yiftachel (2009), informal settlements are “grey spaces”, as they are neither integrated nor eliminated from city plans, economics, and polity. The informality of populations and activities in urban informal settlements contributes to them being in a perpetual state of “permanent temporariness”, meaning that they are acknowledged to exist but, at the same time, are destined for elimination (Yiftachel 2009). In short, informal spaces are a manifestation of urban inequities in wealth, health, and wellbeing (ibid.). There is limited literature on inequities within urban informal settlements and the invisibility of specific populations residing and working within them (Elsey et al. 2016). The central focus of the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), ‘leave no one behind’, commits to eradicating poverty (Goal 1) and reducing inequality and vulnerabilities (Goal 10) (United Nations 2017). In addition, the specific goals for health and wellbeing (Goal 3) and sustainable cities and communities (Goal 11) cannot be achieved without a concerted effort to improve the lives of the most marginalised populations living and working in urban informal settlements (United Nations 2017).

There are multiple, intersecting axes of inequity for people living in urban informal settlements, such as age, gender identity, and disability. Positionalities within these systems of power create vulnerabilities for particular individuals and households that exacerbate their discrimination and exclusion. Such positionalities of intersecting vulnerabilities can lead to marginalisation and exclusion from mainstream social, educational and cultural life (Sevelius et al. 2020). The Accountability and Responsiveness in Informal Settlements for Equity (ARISE) Research Consortium aims to increase accountability for marginalised people working and living in informal settlements to claim their rights to health across cities in Kenya, Sierra Leone, India, and Bangladesh (ARISE 2022). Whilst the Kenyan government has made efforts to reduce inequities in health outcomes at a national level, urban informal settlements and particularly vulnerable groups within them are being left behind. Through ARISE’s work of exploring inequities within informal settlements, child-headed households (CHHs) in Nairobi have emerged as a particularly vulnerable group.

1.2. Wellbeing as a Development Concept

Wellbeing as a concept emerged as a counterpoint to narrowly materialist and economic framings and measurements of development. Whilst complex and contested, understandings of wellbeing tend to share a holistic approach that includes multiple dynamic, person- and culture-specific dimensions of human experience, including material, subjective and relational dimensions (White 2009; King et al. 2014). Loewenson and Masotya (2018) identify areas of commonality among twelve wellbeing frameworks: social and political; material; ecological; and ‘other’ (which incorporates subjective dimensions such as people’s levels of satisfaction and priorities). There is no commonly agreed upon definition of wellbeing (Loewenson and Masotya 2018). White (2010) points to a common formulation of wellbeing as ‘doing well, feeling good; doing good, feeling well’: ‘doing well’ referring to the material welfare or standard of living; ‘feeling good’ expressing a personal perception of satisfaction with life; ‘doing good’ relating to a moral dimension of ‘living a good life’, and ‘feeling well’ encapsulating a holistic sense of health (White 2010). King et al. (2014) broadly define wellbeing based on objective and subjective viewpoints. Objective components of wellbeing include many material and social attributes of people’s life circumstances such as physical resources, employment and income, education, health, and housing (King et al. 2014). Subjective components of wellbeing relate to individuals’ thoughts and feelings about their life and circumstances, and their level of satisfaction with specific dimensions (ibid.). White’s (2019) influential ‘Bath framework’ conceptualises wellbeing as both a process and an outcome, involving the interplay between material and relational, objective and subjective dimensions of lived experience, which is dialectically produced in relation to social, economic, and political structures of power over time and space.

In this article, we use White’s (2009) wellbeing pyramid framework to frame and explore the unique experiences of CHHs and how these change through time and space. Within this framework, three dimensions are identified, which are seen as interdependent. The material dimension comprises aspects of living standards such as levels of consumption, livelihoods, and wealth. The relational dimension is made up of two aspects: first, social relations and access to public goods, including social networks, relations with the state, security and socio-cultural identities and inequities; and second, human capabilities, including education, information and skills, physical health and (dis)ability, personal relationships of love and obligation, self-concepts and attitudes to life. The subjective dimension comprises people’s perceptions of their positions, both material and relational, their cultural values, ideologies, and beliefs. The subjective dimension is placed at the apex of a pyramid, emphasising that the meaning of a ‘good life’ is inextricably linked with subjective values located in time and place.

1.3. Wellbeing and Vulnerabilities of Child-Headed Households

A CHH is a complex construct with varied understandings across contexts (Van Breda) Here, CHHs are households where children assume most or all of the day-to-day parental and household responsibilities due to the death, illness, or incapacitation of parents or any adult caregiver (Le Roux-Kemp 2013; Thwala 2018). Sometimes, the extended family can absorb children, but changes such as urbanisation, challenging economic circumstances, and Westernisation have altered the tradition of children being absorbed by the communities surrounding them (Kanyi). When families do not absorb children within their communities, the eldest of the children may assume parental responsibilities (Van Breda 2010; Chidziva and Heeralal 2016). In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the limited literature on CHHs mainly focuses on children that were made orphans amidst the strains on kinship networks due to the high mortality from the HIV/AIDS pandemic (Chademana and Van Wyk 2021; Francis-Chizororo 2010; Mogotlane et al. 2010; Collins et al. 2016). The scale of the CHHs problem in Kenya is significant. Government surveys estimate that 8.4% of Kenya’s children are orphans (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics 2021). An estimated 870,000 orphaned and vulnerable children (OVC) benefit from international charities, and the Kenya government is financing social security interventions such as cash-transfer programs (Ministry of Health 2018). A national HIV survey in 2021 revealed there were approximately 2.6 million OVC in Kenya; 1.8 million were orphans and 750,000 were vulnerable (Lee et al. 2014).

Studies of CHHs experiences in Africa are framed from a range of perspectives, including quality of life (Chademana and Van Wyk 2021; Awino 2010), vulnerabilities (Donald and Clacherty 2005), resilience (Ward and Eyber 2009) and coping strategies (Daniel and Mathias 2012; Kurebwa and Kurebwa 2014). Some studies focus on psychological or psychosocial wellbeing (Caserta et al. 2017; Makuyana et al. 2020), whilst others consider multiple aspects of daily life including material, social aspects (Kanyi 2019; Collins et al. 2016; Kurebwa and Kurebwa 2014; Evans 2005; Mogotlane et al. 2010).

These studies have identified multi-layered vulnerabilities of CHH. Ward and Eyber (2009) argue that a child’s vulnerability is defined by the complex and dynamic interplay of individual characteristics, as well as risk and protective factors in his/her environment (Ward and Eyber 2009). Limited financial assets of CHHs often means that their socio-economic needs including access to food, health, hygiene, education, safety and shelter are not met (Mogotlane et al. 2010). Lack of material needs such as shelter creates increased exposure to extreme temperatures across different seasons and may perpetuate related health challenges (Chademana and Van Wyk 2021). Furthermore, lack of financial resources (Chademana and Van Wyk 2021) as well as lack of knowledge or the right documentation (Mogotlane et al. 2010) hinders adequate access to general health services. Rapid parentification and lack of financial assets translates to high school dropout rates, which have longstanding impacts on the opportunities for CHHs to break out of cycles of poverty (Collins et al. 2016; Kurebwa and Kurebwa 2014). CHHs are often vulnerable to exploitation by family, such as failure to recognise or grabbing inheritance, including in informal settlements in Kenya (Kanyi 2019) as well as in Uganda (Collins et al. 2016). Multiple layers of hardships intersect with social dimensions of vulnerability—such as stigma, exclusion and exploitation—and psychological trauma related to multiple losses, resulting in anxiety and depression, which are further exacerbated by lack of support and limited psychological resources (Van Breda 2010; Kanyi 2019; Mogotlane et al. 2010; Collins et al. 2016; Makuyana et al. 2020). Ndeda (2013) found that girls who head households experience a ‘double vulnerability’ by nature of their gender. Girls heading households take on a larger share of the caring responsibility and are more likely to report feelings of hopelessness and negative symptoms (Ndeda 2013). Despite experiencing chronic crises, many studies find that CHHs are resilient and adopt specific strategies such as developing time and financial management skills and social networking (Awino 2010; Donald and Clacherty 2005; Ward and Eyber 2009).

Experiences of CHHs in Kenya and Nairobi in particular are not well understood (Gaciuki 2010), which limits opportunities to hold duty bearers accountable for their wellbeing (Lee et al. 2014). This study aimed to deepen understanding by exploring the experiences and drivers of vulnerability and wellbeing of CHHs in the specific context of two informal settlements in Nairobi from their own perspectives. A holistic wellbeing framing allows us to draw out the material, social and human dimensions that intersect to impact their experiences and perceptions of wellbeing and shape how they navigate the challenging environment they live in.

2. Materials and Methods

Study setting: This study took place in Viwandani and Korogocho informal settlements in Nairobi, which have an estimated population of 52,698 and 36,276 residents, respectively. Korogocho, the fourth largest informal settlement located in the northeast of Nairobi, covers an area of about 0.97 km2 (Beguy et al. 2015; Emina et al. 2011). Housing structures are built in rows and are mostly made of mud and timber walls, and waste tin cans are used as the roofing material. Korogocho has a settled population, as many of the residents have lived there for many years. Nairobi city’s only dumpsite is adjacent to Korogocho and is a source of livelihood for many youthful residents who scavenge solid waste material for selling. The Viwandani informal settlement is situated on public land, occupied by its residents since 1973. In contrast to Korogocho, most residents are youthful and highly mobile, working or seeking employment within the nearby industrial area. Viwandani is situated along the Nairobi River, which is heavily polluted with industrial waste from the neighbouring industries. The majority of residential structures in Viwandani are made from iron sheets. Korogocho and Viwandani are characterised by poor or lack of basic infrastructures such as roads and sanitation.

Study design and background to project: We adopted a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach, which was conducted within the larger ARISE Research Consortium. We first conducted a social mapping exercise in Korogocho and Viwandani to identify the most marginalised groups in both urban informal settlements. Through prioritisation exercises, community stakeholders identified older persons, persons with disability, and CHHs as particularly vulnerable and marginalised groups in both communities. We used the photo-voice research method, a form of visual participatory data collection with members of the marginalised groups that were residents of both urban informal settlements. Photovoice is a participatory visual research method that seeks to ‘give voice’ to communities using photography. This method enables an in-depth understanding of the realities of people that otherwise might remain inaccessible (Wang et al. 1997; Le and Yu 2021). Photovoice is frequently employed in community-based participatory research (CBPR) by giving cameras to participants to enable them to act as ‘co-researchers’ to identify and reflect on issues within their own community (Wang et al. 1997). This method has the potential to stimulate social engagement and the co-creation of sustainable solutions to complex problems (Budig et al. 2018; Fairey 2018; Nykiforuk et al. 2011). Photovoice has been applied to a wide range of health-related topics, (Catalani and Minkler 2010) such as community-based palliative care (Bates et al. 2018); child care in urban informal settlements (Hughes et al. 2020); maternal, child and women’s (Wang 1999; Wang and Pies 2004); water, sanitation, hygiene (Bisung et al. 2015); and clean cooking practices and interventions (Ardrey et al. 2021; Ronzi et al. 2019). In this study, photovoice enabled us to gain an in-depth understanding of the daily lived experiences of the participants regarding marginalisation, wellbeing, and agency (Chloe et al. 2020; Lindhout et al. 2021). The approach enabled us to explore and understand the complex problems in the study settings in a way that is relevant to residents of informal settlements. In this article, we present and discuss in depth the findings of photovoice conducted with child-headed households as this speaks to a clear evidence gap in the Kenyan setting. Findings from other marginalised groups with whom photovoice was conducted will be published separately.

Study Participants

We undertook photovoice with four CHHs—two from each settlement. All participants had been residents in the informal settlement for at least six months, were above 15 years old and qualified as mature minors (National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP) 2015). The photovoice process with these participants included production and discussion of visual data and narratives and is described in detail below. In addition, we conducted in-depth interviews (IDIs) in Swahili with eight additional children who were heading households. Characteristics of all participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study participants (n = 12).

Recruitment and training: Before we implemented the photovoice research, we sensitised community representatives and leaders on this study and clarified the purpose. During the sensitisation meetings, we presented to community gatekeepers how we selected the marginalised groups to work within both study sites. We then purposively sampled photovoice participants with help from community gatekeepers such as village elders, religious leaders, and community health volunteers (CHVs). We partnered with CHVs to vet each participant to ensure that they met the eligibility criteria. The CHVs, who were also residents in the study sites, had detailed knowledge of residents and their living conditions in both study settings. After obtaining written consent from the participants, we trained them for two days on how to take photos that convey meaning and photography ethics using simple terms and definitions. Because none of the participants had ever used a smartphone before, we trained them on photovoice using photos in newspapers to demonstrate photo angles and lighting. Before issuing the phones to the participants, we ensured they had adequate internet bundles throughout the study by regularly topping up their internet credit. We then activated the phones to automatically synchronise photographs into cloud storage to ensure real-time backing-up of photographs. We also installed the WhatsApp™ application to enable participants to share their photos with the research team daily. Photos shared via WhatsApp™ were backed up in a password-protected cloud database.

Data collection: The process entailed three rounds of photography over a period of three weeks. In the first week, the participants took photos that reflected their day-to-day life, highlighting what marginalisation meant to them and how it was reflected in their lives daily. In the second week of photovoice, participants took photos that reflected what health and wellbeing meant to them. CHHs participants then highlighted their daily experiences (positive and negative) related to their health and well-being. In the third week, participants took photos that represented what needed to be addressed to make their own lives better and improve their health and wellbeing. Research team members met with the CHHs participants weekly to conduct in-depth interviews to gain a deeper understanding of why they took each photograph. These weekly meetings provided opportunities for researchers to engage with each of the CHHs and understand their fears and hopes regarding health and well-being.

We documented feedback from each CHH on how the process impacted them as informal settlement residents. During these interviews, we encouraged each CHH to select five (5) photographs that would be shared with other CHHs and community members in a co-analysis workshop. After selecting the five photographs, we encouraged each CHH participant to write a caption that best described each of the five photographs they had selected. We then obtained another round of written consent from the CHHs to allow us to use the photos for advocacy and dissemination of study findings. We conducted additional in-depth interviews with eight additional CHHs, who were not part of those in the photovoice, in our study settings. In-depth interviews with these additional CHHs explored their experiences and perceptions of marginalization and vulnerability, and what can be done to alleviate these experiences. We conducted reflexivity sessions among the research team members and with the CHVs to journal our positionality, biases, experiences, challenges, and assumptions about our participants and their lived experiences. The research team held a series of four workshops to reflect on the photos prioritised by the photovoice participants, to further reflect on how they represented their everyday lived experiences of vulnerability and marginalisation among CHH.

Data management and analysis: We transcribed the digital audio recordings verbatim in MS Word™ and translated them to English. Four researchers read through all the transcripts to ensure they aligned with the audio recordings and ensure that no meaning was lost during translation. We uploaded both transcripts and captioned photographs in the NVivo R version1.6 (QSR International Australia) analysis software for analysis. We used the framework analysis approach to analyse all IDIs and photovoice transcripts. This approach enabled us to organise and categorise narratives in the IDI transcripts and captioned photographs into themes and emerging concepts (Gale et al. 2013; Nowell et al. 2017). Four research team members independently read and re-read the transcripts and viewed the related photos to identify emerging themes and concepts inductively. We also analysed the captioned photos to categorise them into themes. To enhance trustworthiness in our analysis, four researchers (RK, IN, RS, NW) independently coded eight randomly selected transcripts with related photos in NVivo, discussed any discrepancies in coding, and made minor adjustments to the coding framework. We trained the research assistants on qualitative methods to ensure a high-quality standard. More experienced researchers continuously mentored the research assistants at all phases of this research. We utilised the reflexivity sessions to enhance the trustworthiness of our study by identifying any biases and values that may influence how we analysed and interpreted the qualitative data. We then charted the data to summarise our key findings, which we presented as preliminary findings to the CHHs participants and community leaders for validation and additional input.

Ethical and safeguarding considerations: We obtained clearance to conduct this study from the AMREF Africa Ethics and Scientific Review Committee (ESRC-P747/2019) and the National Council for Science, Technology, and Innovation. We also received broader ethical clearance from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (Protocol: 19-089). Before our participants were engaged, they were trained on safeguarding and reporting channels for the same; thereafter, we sought written informed consent from them. Because we conducted this study within the evolving COVID-19 pandemic in 2021 and 2022, we ensured strict adherence to Kenya’s public health regulations to minimise the risk of transmission, namely physical masks, physical distancing, and handwashing before each meeting and IDI. As part of our safeguarding considerations, we resolved that the ubiquitous nature of smartphones in Korogocho and Viwandani meant that possession of smartphones did not pose an additional threat to CHHs in our study, though we tracked them to ensure that data were safe. We trained the participants on photography ethics at the start of the study and provided continuous mentorship on the ethical conduct of photovoice. No safeguarding concerns or challenges with photography arose during data collection. We, however, offered counseling to the study participants after each data collection session. We also observed study participants for any signs of distress and discomfort during IDIs for referral to professional counseling services and follow-up, at no cost to them. We put in place safeguarding measures to prevent and manage burnout among researchers during data collection and analysis. Additionally, researchers participated in weekly debriefing sessions to minimise the risk of psychological distress. The ARISE Hub developed a safeguarding policy and identified safeguarding leads who met quarterly to deliberate on emerging concerns and agree on actions to address the safeguarding dilemmas. As part of our safeguarding practices, we organised group and individual counseling sessions for the CHHs participants to address any grief and distress that may have been triggered during the photovoice and IDIs.

3. Results

In this section, we present data on the perceptions and experiences of vulnerability and marginalisation among CHHs in our study sites. We also explored determinants that exacerbated their vulnerability in informal settlements. We structured our findings around the dimensions of White’s wellbeing triangle (material, social, human, and subjective). Our results demonstrate much interaction between the dimensions, and we draw out these interlinkages and dynamics.

3.1. Participant Characteristics

All participants were born in urban informal settlements and had experienced poverty since birth. Five CHHs (all boys) were living with a parent that was incapacitated by either illness or alcohol dependence. Four CHHs (all girls) had been abandoned by their parents; two were orphaned (a boy and a girl), and one girl was driven away from her home by her parents when she became pregnant. The CHHs were living in parts of the urban informal settlements that were prone to flooding and environmental hazards. Their living surroundings were made hazardous by either open sewers or illegal electricity connections. The CHHs faced continuous experiences of food insecurity and hunger. Table 2 provides additional characteristics of the CHHs in our study.

Table 2.

Characteristics of CHHs in Viwandani and Korogocho informal settlements.

3.2. Material Aspects of Wellbeing

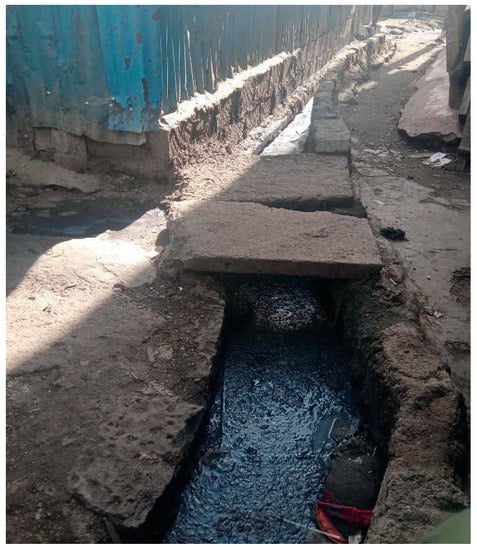

The physical environment was a key concern to CHHs participants. They reported living in dirty environments that weighed heavily on their minds and mental wellbeing. They also highlighted living in an environment characterised by exposed electricity wires that were used in illegal electricity connections, open sewage, and chemicals that produce a pungent stench. They perceived such environmental conditions where they lived as worse compared to other parts of the informal settlement in which they resided, and were ostracised by their peers due to their dirty living conditions. Consequently, their living environments impacted their own and their families’ physical health and wellbeing (human dimension) and influenced their subjective wellbeing as described in the photos below (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

“So, the [electricity] wires are actually stima za kusambaza (illegal electricity connections), they are very dangerous. They can electrocute when wet…at night you cannot sleep because they start producing sparks…there is a time they burnt a house” (Daniel, 17-year-old boy, Viwandani).

Figure 2.

“They should build for us a proper sewage system…the ones constructed underground so that we cannot see them. It also prevents us from contracting many diseases” (Daniel, 17-year-old boy, Viwandani).

The CHHs, especially in Viwandani, reported that they lived under the constant threat of electrocution due to the exposed electrical wires that are used for illegal electricity connections in the informal settlement, as reflected in this quote:

“Like at the bridge. When the bridge was removed there were some wires that were there on the wall. A woman went to pass, she touched a wire and she was electrocuted. So people are even afraid to pass through that road because of the wires…They [electricity gangs] hook electricity on your roof. So, when you touch the roof, you are shocked [electrocuted].”(Mwangaza, 17-year-old girl, Viwandani)

Some structure owners deliberately electrified their iron-sheet houses to prevent people from touching their roofs as they navigate the alleys within the urban settlements:

“During floods, the house owner may shock [electrocute] you so that you don’t touch his roof while crossing the floods. That is the electricity challenge here. Someone puts current so that you don’t touch his roof while you cross. They think you will lean on it [the roof] and bend it. So they put a current there.”(Mwangaza, 17-year-old girl, Viwandani)

Violet, who recently entered a CHH, also reflected on her own wellbeing in relation to other neighbourhoods. She expressed a form of grievance for her old life before her mother became unwell, highlighting the dynamic and relational aspects of wellbeing that shift with time and space.

“Those who are living in other areas like for example in Civo (nearby middle-class estate). They usually have garbage collection but here in Korogocho there is no garbage collection, you just throw the garbage into the river. Others even do flying toilets…. Someone goes for a long call (defecates) then puts the human waste in a plastic bag and throws it away. Sometimes it can even land into your food and they won’t be bothered. For them, wherever it goes, let it go it’s okay, but in the estates you cannot find such things.”(Violet, 17-year-old girl, Korogocho)

Our participants also reported that they lacked adequate nutrition and access to food, especially for themselves and their siblings. CHHs in Korogocho reported that the only food they could find was from either scavenging within the dumpsite or buying the cheapest available, which was kale and ugali (corn meal). Due to inadequate food, the CHHs narrated during the interviews that they often went without meals for prolonged periods of time or had to share small amounts of food with their siblings, as these quotes illustrate:

“I get laundry work to do…. There are sometimes I don’t get [any] at all and sometimes I get—it depends. … When I don’t get, we sleep like that… We sleep hungry.”(Paula, 17-year-old girl, Viwandani)

The photos presented below (Figure 3 and Figure 4) and their narratives illustrate CHHs experiences of accessing food for themselves and their siblings.

Figure 3.

“This photo was taken on a day when I had gone to work but I wasn’t feeling well, so I just washed utensils for one person then bought rice which we ate on that day. Before we were not eating like this—everyone was eating from their own plate—but nowadays, we are sharing because it is not much. So you just put there for everyone to eat. Sometimes we even do not have any food to eat. The first days when my mum fell sick, the kids had not gotten used to eating less food but now, they are used to it. When you tell them that there is no lunch, they will just go out to play. Sometimes they will just sleep hungry since they are used to it” (Violet, 17-year-old girl, Korogocho).

Figure 4.

“We had that ugali but had nothing like vegetables to eat it with…and sometimes we have the vegetables with no money for flour” (Paula, 17-year-old girl, Viwandani).

CHHs of both genders in Korogocho reported scavenging in the nearby dumpsite for plastics, papers, and food. A male CHHs in the same setting worked in illicit brew dens to generate income for their upkeep as one male CHH narrated:

“I have been living as a street child, getting my earning from the garbage scavenging. Whatever I get, I go and sell and get money to go and buy food or sometimes [I] ask for some work from those who brew alcohol. Those who brew alcohol tell us to go to Boma and bring to them those things used to brew alcohol and when there is water shortage we go and fetch water for them… such things.”(Job, 17-year-old boy, Korogocho)

This also revealed the subjective dimensions with regard to how CHHs viewed their satisfaction with the income-generating activities available to them—and how this interacted with the relational aspects of wellbeing—as the stigmatisation caused by working on the dumpsite and judgement from their peers caused distress:

“With my kind of work and having to collect garbage and over-ripe bananas, I am bound to get dirty. My peers (living in same settlement) tell me that I resemble a Chokora (homeless street child). They make fun that I eat food from the garbage river. They go to the extent of saying that I might infect them with COVID-19 just by virtue of being dirty.”(Robert, 17-year-old boy, Korogocho)

The prioritisation of survival over education for this CHH was challenging and distressing to them. CHHs were somewhat envious of other children who did not have to take on such premature burdens of responsibility. Two CHHs reported a “positive” effect from the government directive when they closed all schools for almost nine months during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Closure of schools during the COVID-19 pandemic meant that the CHHs had more time to scavenge in the Dandora dumpsite for food and recyclable waste that they sold for upkeep without falling behind with school work (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

“This is the dumpsite. When we go there we don’t wear gloves because we cannot afford [them] so we have to touch everything. Sometimes we end up touching faeces because that is waste from people’s households. You can even get diseases there. In this picture, I’m at the dump site because some of the waste dumped there is from abroad and that is where COVID is prevalent. So you can end up touching someone’s mask then you forget and touch your face. You see in that situation you may end up getting COVID, so we are at high risk. Sometimes I get sick also—back aches and coughing—because I wake up very early in the morning” (Violet, 17-year-old girl, Korogocho).

Figure 6.

“This is a matatu (minibus or similar vehicle used as a taxi) …where I work this is where I get some money. And the money you know that it is for supper, breakfast and lunch and other responsibilities” (Daniel, 17-year-old boy, Viwandani).

“Last year were it not for COVID, I was struggling…. COVID started in March. Before COVID started I never used to go to school. So to some extent COVID has helped me because all those months I could have missed school since there was nobody at home who could have been left to take care of mum. And my sister has to go to work so that she can get the money for my mother’s medication.”(Violet, 17-year-old girl, Korogocho)

3.3. Social Relational Aspects of Wellbeing

CHHs in our study experienced diminished access to public goods and support from public services. CHHs reflected about the dangerous, insecure and violent environments they experienced daily. They reported the multiple reports of drug and alcohol misuse and crime among their peers. They also asserted that their environment was rife with gender-based violence (GBV) and that girls turning to sex work to earn money to feed their siblings and parents was common, highlighting how gendered power relations also create further vulnerabilities, especially in the urban informal settlements. The quote below demonstrates how the female CHHs’ bodily autonomy is contested, and limited available livelihood options place them at risk of physical harm.

“As I was doing casual jobs of washing clothes and utensils, there was a boy who wooed me, impregnated me. We lived together for like 6 months after I delivered. But he started beating me. I got pregnant, the second time. The guy was still abusive, he threated to stab me and kill the baby. I have even been strangled using electricity wires.”(Sandra, 16-year-old girl, Korogocho)

Some structures that had been built in the informal settlements created a perception of segregation and increased insecurity among residents. For example, a wall had been erected around the Viwandani informal settlement that separated the residents from another residential area that was across a railway line. A CHH elucidated how the wall increased incidents of crime as exemplified below (Figure 7):

Figure 7.

“The government came and put up that wall, to close us in, the people of the Kijiji (referring to Viwandani informal settlement), from the other side of the rail track. So, like when these houses burn, you find that the fire trucks are not able to reach the burning houses…they put up the wall to separate us. You start feeling like you are not a Kenyan, or you feel like you were thrown away and it is like you do not hold any significance” (Daniel, 17-year-old boy, Viwandani).

The general lack of governance and accountability for the wellbeing of CHHs in informal settlements also emerged from the data. Interviewing CHHs in our study revealed the desire for more accountability and support from the government, as well as a platform to be heard and air their grievances. Additionally, CHHs requested investment in their human capital/capacities for sustaining livelihoods that would support their future independence and better wellbeing:

“We need to be given a chance to speak out. You find someone like me needs to be given a chance for us to air grievances or they take us to go and do a course or they offer us jobs.”(Shadrack, 17-year-old boy, Viwandani)

Some CHHs had been previously reliant on this support and had to seek alternative ways of accessing food. This was linked with social networks as a single mother further reported how relief food given during COVID-19 was very ‘discriminative’ and only well-connected people in the community would be called to access relief food. This mother was also turned away and beaten when she sought community support which led her to further isolation from social support networks:

“During that period for COVID, I heard that there was money that used to be sent but I never got to receive any money and even my name was never registered anywhere. I just used to struggle on my own—I go to hassle (slang for work) and then come back I used to hear that people were being sent money …KES 7000 (Approximately USD 70) from the Chief’s Office…but I never received any… I don’t know why I didn’t get it.”(Meshack, 17-year-old boy, Viwandani)

We found cases of CHHs relying on social networks to ease their daily struggles. For example, CHHs gave examples of structure owners that were lenient to CHHs whenever they were late with rent payments. A CHHs also reported receiving “grace periods” for late payment of school fees. Robert narrated how once the two-week grace period for late school fees was up, his teachers displayed a lack of empathy for his situation which impacted his emotional wellbeing:

- R:

- I feel very bad because sometimes the teacher does not care about our situation and thinks one is strong just by their outward looks, but little does he know how much suffering there is on the inside. He sometimes uses harsh and spiteful words while sending us away. He once said, ‘Go and take your mother to town and beg for money’…this is something that we do not want to do. He tries to pressure us into it as long as he gets something to fill his pockets.

- I:

- When you are sent away and there is still learning ongoing, how does this make you feel?

“I feel terrible because everything that will be taught in my absence will not be repeated and this affects my performance in school and my grades as well. In secondary school, the teachers do not repeat what has once been taught even for students who do not understand. To them, it is just a job that will pay them after all and they even result to using rude language when questioned. My classmates are also selfish at times and will not share notes taken in my absence. They, however, tease and insult me citing my situation and poor state. This stresses me.”

Violet also narrated how despite being absent once a day every week to work at the dumpsite or wash clothes, teachers ‘turned a blind eye’ to her situation rather than supporting her to access assistance. There is little opportunity for the CHHs to catch up with missed schoolwork.

3.4. Human Aspects of Wellbeing

The burden of caring for siblings and incapacitated parents emerged as a dominant theme which relates to human relational aspects of wellbeing. Photovoice participants had household structures that differed from the ‘norm’ or their peers, which they lamented. These structures were largely shaped by their parent’s health status characterised by chronic illness, disability and alcoholism. In some cases, the participants became the default head of the household as the eldest sibling, but in other cases, they either became the head of the household due to limited family support, or because elder siblings had turned to alcohol and drugs to cope. None of the participants reported receiving familial or social support with taking care of their incapacitated parents and younger siblings.

“[Other relatives] are there but you cannot depend on them every day like for example today you go to them and borrow. Same situation again tomorrow they will tell you to also go out and work… I know you are aware how bad the relatives usually talk so you are forced to just depend on yourself. Sometimes they can even call to form a committee but the committee is not for helping it is just for gossip. So, you are forced to just solve your problems within your house.”(Violet, CHH, 17-year-old girl, Korogocho)

Participants demonstrated wisdom and maturity but also expressed sadness at the situations they found themselves in, longing for a return to normality or to be like their peers. CHHs took on a huge burden of caregiving and had to ensure their younger siblings and incapacitated parents were bathed and fed, on top of school work and income-generating activities for rent, food and school fees leaving them little time for leisure. There were no differences in the burden of care between male and female participants because children of both genders played this role. Tumaini’s account of her day illustrates the heavy burden of responsibilities and time constraints:

“I usually wake up at 4.30 a.m. take a bath then prepare by 5.30 I make sure that even the other children have prepared and gone to school. Then I go to school and come back in the house around 6.20 or 6.30 p.m. there about. Upon arriving home I check with my sister—if there is work that she hasn’t done, I do it, then check up on my mum to see if she has had her porridge or not. After that I go to the market shop for vegetables, then come and prepare them, then cook, after which I feed my mum… I serve food to the small ones first then give to my mum. I usually go to bed at around 9.30 p.m.”(Tumaini, 17-year-old girl, Korogocho)

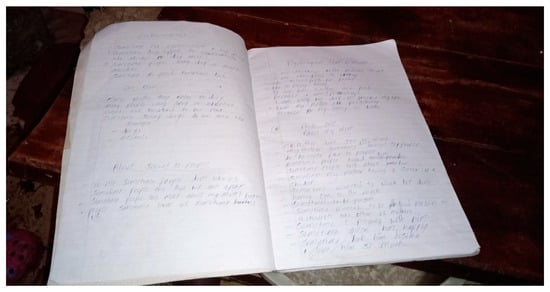

During the interviews, we observed stress among all the CHHs due to the caregiving roles, which had a direct effect on their mental health and lack of concentration in class. As a result, these children performed poorly academically, and some CHHs dropped out of school to take care of their family members, thus limiting their ability to attain education and break the cycle of poverty (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

“Sometimes, when in school, my thoughts are still at the situation back at home. I am constantly in conflict [about] whether I should be in school or proving for my family and help my mum. The book there is to remind me that education is still a pillar of my life in my quest to sustain my family” (Robert, 17-year-old boy, Korogocho).

As well as impacting their emotional wellbeing, their role as primary breadwinners and caregivers impacts their physical health. Stress was reported as leading to ulcers, and being forced to work in dangerous, unsanitary and unhygienic conditions that would lead to lung disease and nose bleeds to sustain their families also took its toll physically.

“Yes, it is at the market where I work. There is a place where there’s sewage belonging to Nairobi water, but it smells so bad so whenever I come to dispose the ‘’mahuti’’ (onion waste)…the stench from the sewage comes with a lot of pressure and the poison from those chemicals spoils my clothes—it also affects my chest and also there is a lot of dirt like from avocados and other garbage, but that is the same place that I try to look for something while I use my bare hands when looking for something or sweeping. It affects my clothes—for example you can see this sack that I usually use to carry the garbage is dirty and it also spoils my clothes. And also, the stench of that garbage and carrying the garbage on my back which affects my skin and makes it start peeling off.”(Robert, 17 year-old boy, Korogocho)

3.5. Subjective Perceptions of Wellbeing

The narratives from participants described the lack of social interactions for CHHs in some cases, leading to loneliness and stress. Their perception of their wellbeing was also shaped by comparison to their peers, who did not have to work as hard as our participants and the heavy responsibility of caregiving and raining money to support their families, as illustrated in these quotes:

“I feel bad that my friends are living comfortably while I’m suffering…When my friends call me to hang out, I cannot because most of the time, my mind is thinking of home. My friends sometimes advise and encouraged me to stop thinking about home and my family, but I cannot because I am the one who has to sustain it. Some of my peers who live with disabled parents have rejected their situations and abandoned responsibility and they even encourage me to do so but I cannot because even though my mother is blind, I still value her advice and respect her. This does not go down well with my peers who make me feel isolated and alone.”(Musa, 17-year-old boy, Korogocho)

Subjective perceptions of wellbeing among CHHs intersected with the human (caring burdens) and social (discrimination and stigma) dimensions. Generally, there was a sense of loss among all the CHHs in our study. This was manifested in the form of grief, especially due to the burdens that the CHHs experienced due to either incapacitation or absence of their parents due to death or desertion.

Despite the suffering, there were also many examples of resilience, agency, and human capabilities expressed and demonstrated by participants. While being caught in hardship, CHHs expressed hope and optimism that things would change in the future and persistence in pursuing their goals, such as education. Further, they demonstrated leadership and encouragement to their younger siblings and fellow CHHs.

- I:

- What made you feel that these pictures are important?

- R:

- “These pictures are important because one day I believe ‘nitaomoka’ (I will become rich). So when I’ll look back at these photos, they will be reminding me of where I came from, so that is why I was taking them” (Violet, 17-year-old, Korogocho).

Robert used faith as a coping mechanism. He gained a lot of his strength to keep going from his faith; this enabled him to resist the temptation to succumb to peer pressure and fall into drugs like many of his friends. However, he also questioned God in relation to his situation as compared with his peers:

- R:

- When I see my friends going out, I question God about my situation. Some of them are also realising and utilising their talents while I do not get the chance to do so myself. I ask God why he made my situation to be like this.

- I:

- What is your talent?

- R:

- I have three. One is dancing another is drawing… actually, I have three, and acting.

4. Discussion

We conducted this study to explore the perceptions and experiences of wellbeing and its drivers with CHHs in Nairobi’s informal settlements. Our study identified severe and inter-related health and wellbeing vulnerabilities facing CHHs across the material, human, relational and subjective dimensions in White’s wellbeing framework (White 2009). Key experiences of marginalisation were lack of adequate food and nutrition, hazardous living conditions, stigma from peers and exploitation from employers due to the limited livelihood opportunities available to them. The daily experiences of extreme deprivation and the stress of survival in these harsh material and social conditions impacted the physical, mental health and perceptions of self-worth among CHHs and their siblings. They further negatively impacted their school performance and attendance with potentially long-term consequences for the development of their human capabilities and opportunities to improve their situations. Despite their many vulnerabilities, we documented resilience among CHHs. In this section, we discuss the key findings, propose recommendations, strengths and limitations of the study.

Urban poverty and realities of life in informal settlements are poorly measured and documented, especially in national demographic surveys. As a result, the poor, including CHH, become increasingly invisible (Pipa and Conroy 2020), and the status of their health and well-being is largely unknown. The Kenyan government invests in social assistance programs such as cash transfers, social security and tax-funded health insurance for the most vulnerable populations, including CHHs. However, this programming is designed with little or no empirical evidence (McCollum et al. 2018). The social protection policy in Kenya recognizes CHHs as particularly vulnerable (Government of Kenya 2011, 2017). However, an assessment of the social protection programs in Kenya noted that cash transfer programs for orphaned and vulnerable children (OVC) excluded other vulnerable children. Thus, CHHs remain unrecognised despite the care-giving burdens that they carry, which are sometimes heavier than those among adults, given their limited capabilities. As recommended by the Kenya social protection review report, there is need to focus on all vulnerable children including CHHs who may have both or one parent but who may be incapacitated and therefore dependent on their children for all their needs (Government of Kenya 2017).

Our study findings on the material deprivation, including limited access to food, that CHHs face resonate with the findings of other studies in African contexts (Chademana and Van Wyk 2021; Mogotlane et al. 2010). Particular factors emerging in these informal settlement contexts were environmental risks related to not only poor-quality housing, contaminated environment and drinking water, but also the occupational risks related to their limited livelihood opportunities. The deprivations and risks experienced by CHHs in our study expose them to poor health outcomes such as malnutrition and infectious diseases. A comparative study in Kenya revealed that children in urban informal settlements are particularly vulnerable and their health outcomes in urban informal settlements are worse than in rural parts of Kenya (Ezeh et al. 2017). In line with other studies with CHHs, we found that health vulnerabilities were further exacerbated by poor financial and social access to healthcare, including lack of documentation to prove entitlements (Chademana and Van Wyk 2021; Mogotlane et al. 2010). Studies with CHHs in settings similar to our study sites reported similar risk factors for malnutrition and infectious diseases that contribute to stunted growth and longer-term effects on cognitive development, which affect school performance (Ezeh et al. 2017; De Vita et al. 2019). The social vulnerabilities faced by the CHHs in our study further resonate with studies in other informal settlements which show that social vulnerabilities exacerbated material deprivations and risks of poor health (Kanyi 2019; Collins et al. 2016). Together, social isolation and discrimination contribute towards poor mental health for many CHHs (Van Breda 2010; Kanyi 2019; Mogotlane et al. 2010; Collins et al. 2016; Makuyana et al. 2020).

We found that the generationally transferred poverty experienced by CHHs in urban informal settlements worsens their limited access to and participation in school. Whilst some of the CHHs and their siblings remained in school, their material circumstances directly and indirectly affected their academic performance. Lack of empathy, negative attitudes from both teachers and classmates, stigmatization and social exclusion are common negative experiences reported by CHHs that remain in school (Pillay 2016). These hostilities result in CHHs feeling insecure, overwhelmed and performing poorly academically (ibid.). Our findings resonate with the existing literature that documents the negative effects of poverty and related stress, poor health, and nutrition on academic performance of CHHs (Collins et al. 2016; Kurebwa and Kurebwa 2014) including those residing in urban informal settlements in Kenya (Kakulu 2008; Moyo 2013). Kakulu (2008) found that poor school performance reduces CHHs chances of improving their livelihoods and escaping the vicious cycle of poverty inherited from their parents (Kakulu 2008). Despite the multi-layered vulnerabilities facing CHHs, our study findings align with others that identified their resilience, adaptability and capabilities (Awino 2010; Donald and Clacherty 2005; Ward and Eyber 2009).

An important strength of our study was the participatory methodology, which creates spaces for and emphasises the importance of listening to children’s voices and recognizing their capacities as a basis for designing interventions to strengthen their wellbeing (Ward and Eyber 2009). A limitation of our study is that financial and time constraints, to date, have limited the opportunities of CHHs to participate beyond the photovoice process to define the aims and approaches of the study. However, the participatory process is incomplete to date, with an intention for subsequent involvement of CHHs to prioritise ensuring that their perspectives and priorities influence the design of supportive interventions.

Over the years, national governments and city authorities have ignored urban informal settlements and failed to identify them as unique settings, compared to other urban settings, during national surveys (The Lancet 2017). This failure further marginalises CHHs and other vulnerable groups living in informal settlements. We propose two recommendations. First, we recommend that city and national authorities recognise that urban informal settlements are a modern and growing phenomenon with identifiable challenges. Secondly, we call on government authorities to conduct a granular analysis of survey data to identify the exact populations that are left behind, especially in the urban informal settlements. This will require additional capacity strengthening for statistical offices to collect and analyse data from these informal settlements (Pipa and Conroy 2020). Such recognition of the rights of people living in informal settlements and granular information about specific vulnerabilities should be used to develop evidence-based interventions to promote health and wellbeing.

5. Conclusions

Photovoice enabled us to shed light on wicked problems that contribute to the vulnerability and marginalisation of children heading households. Efforts to mitigate the economic and social drivers that contribute to the emergence of child-headed households should be prioritised. Using photovoice, we identified the day-to-day experiences of CHHs, who go through financial, educational, and parental poverty and are highly likely to transfer these vulnerabilities to the next generation. Policymakers should prioritize mitigating the generational transfer of poverty, especially in urban informal settlements. Through our photovoice findings, we recommend a multi-disciplinary approach for mitigating generational poverty that is inherited by CHHs. We recommend that policymakers, researchers, and advocates implement long-term strategies for addressing the factors that could curb generational poverty from CHHs to their children. For example, these actors could target the implementation of social protection, education subsidies, and employment creation interventions for vulnerable young people, particularly CHHs. Our findings also illustrate how lack of access to health services and catastrophic health expenditures lead to poverty and cause children to take on adult roles when parents become incapacitated due to unresolved debilitating chronic illnesses. We recommend an expedited scale-up of existing public-funded health insurance for marginalised persons in the urban informal settlements who need it the most. Finally, this photovoice study illustrates that vulnerable and marginalised CHHs can participate in identifying and prioritizing problems that affect their health and wellbeing. Participatory approaches offer potential to give a voice to CHHs by engaging them in co-designing interventions that will mitigate poverty and promote wellbeing for all in urban informal settlements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T., R.K., R.S., I.N., M.L. and L.O.; Methodology, R.S., R.K., L.A.O., R.T., M.L., N.W.G. and N.M.; Formal Analysis, R.S., M.L., N.W.G., I.N., L.A.O. and L.O.; Investigation, N.M. and L.A.O.; Data Curation, R.K., I.N. and N.W.G.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.L., R.S., R.T., R.K., I.N. and S.T.; Writing—Review & Editing, R.K., R.T., N.W.G. and S.T.; Project Administration, N.M. and L.O.; Funding Acquisition, S.T., L.O., S.T. and R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The GCRF Accountability for Informal Urban Equity Hub (“ARISE”) is a UKRI Collective Fund award with award reference ES/S00811X/1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the AMREF Africa Ethics and Scientific Review Committee (ESRC-P747/2019; Date: 8 May 2020) and the National Council for Science, Technology, and Innovation (NACOSTI/P/20/7726; Date: 20 November 2020). We also received broader ethical clearance from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (Protocol: 19-089; Date 21 January 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the need to protect the confidentiality of children involved in the research.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to all children who accepted to participate in this study. We also thank our research team that comprised Faith Munyao, Jane Muturi and Sakibu Lyaga who tirelessly ensured that our participants were safe and that we collected high quality data. We also thank the community leaders in our study settings and the Nairobi Metropolitan Services for allowing us to carry out this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ardrey, Jane, Kate Jehan, Kate Desmond, Caroline Kumbuyo, Kumbuyo Mortimer, and Rachel Tolhurst. 2021. ‘Cooking Is for Everyone?’: Exploring the Complexity of Gendered Dynamics in a Cookstove Intervention Study in Rural Malawi. Global Health Action 14: 2006425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ARISE. 2022. Accountability and Responsiveness in Informal Settlements for Equity (Arise). Available online: https://www.ariseconsortium.org/ (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Awino, Dorcus. 2010. Life in a Child/Adolescent Headed Household. A Qualitative Study on Everyday Life Experience of Children Living in Child/Adolescent Headed Households in Western Kenya Region. Umeå: Umeå University. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, Maya Jane, Jane Ardrey, Treza Mphwatiwa, Squire Bertel Squire, and Louis Willem Niessen. 2018. Enhanced Patient Research Participation: A Photovoice Study in Blantyre Malawi. BMJ Support Palliat Care 8: 171–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beguy, Donatien, Patricia Elung’ata, Blessing Mberu, Clement Oduor, Marylene Wamukoya, Bonface Nganyi, and Alex Ezeh. 2015. Health & Demographic Surveillance System Profile: The Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (Nuhdss). International Journal of Epidemiology 44: 462–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisung, Elijah, Susan Elliott, Bernard Abudho, Diana Karanja, and Corrine Schuster-Wallace. 2015. Using Photovoice As a Community Based Participatory Research Tool for Changing Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Behaviours in Usoma, Kenya. BioMed Research International 2015: 903025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budig, Kirsten, Julia Diez, Paloma Conde, Marta Sastre, Mariano Hernán, and Manuel Franco. 2018. Photovoice and Empowerment: Evaluating the Transformative Potential of A Participatory Action Research Project. BMC Public Health 18: 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caserta, Tehetna Alemu, Anna Maija, Pirttilä Backman, and Raija-Leena Punamäki. 2017. The Association between Psychosocial Well-Being and Living Environments: A Case of Orphans in Rwanda. Child & Family Social Work 22: 881–91. [Google Scholar]

- Catalani, Caricia, and Minkler Minkler. 2010. Photovoice: A Review of the Literature in Health and Public Health. Health Education & Behavior 37: 424–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chademana, Kudzai, and Brian Van Wyk. 2021. Life in a Child-Headed Household: Exploring the Quality of Life of Orphans Living in Child-Headed Households in Zimbabwe. African Journal of AIDS Research 20: 172–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidziva, Verna, and Prem Jotham Heeralal. 2016. Circumstances Leading to the Establishment of Child-Headed Households. International Journal for Innovation Education and Research 4: 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chloe, Ilagan, Akbari Zahra, Sethi Bharati, and Williams Allison. 2020. Use of Photovoice Methods in Research on Informal Caring: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Journal of Human Health Research 1: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Lisa, Matthew Ellis, Matthew Pritchard, Christopher Jenkins, Ingrid Hoeritzauer, Adam Farquhar, Orla Laverty, Vincent Murray, and Brett D. Nelson. 2016. Child-Headed Households in Rakai District, Uganda: A Mixed-Methods Study. Paediatrics and International Child Health 36: 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Daniel, Marguerite, and Angela Mathias. 2012. Challenges and coping strategies of orphaned children in Tanzania who are not adequately cared for by adults. African Journal of AIDS Research 11: 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vita, Maria Vittoria, Carlo Scolfaro, Bruna Santini, Antonella Lezo, Federico Gobbi, Dora Buonfrate, Elizabeth W. Kimani-Murage, T. Macharia, M. Wanjohi, J. M. Rovarini, and et al. 2019. Malnutrition, Morbidity and Infection in the Informal Settlements of Nairobi, Kenya: An Epidemiological Study. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 45: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, David, and Glynis Clacherty. 2005. Developmental Vulnerabilities and Strengths of Children Living in Child-Headed Households: A Comparison with Children in Adult-Headed Households in Equivalent Impoverished Communities. African Journal of AIDS Research 4: 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsey, Helen, D. R. Thomson, R. Y. Lin, Uden Maharjan, Siddharth Agarwal, and James Newell. 2016. Addressing Inequities in Urban Health: Do Decision-Makers Have the Data They Need? Report from the Urban Health Data Special Session at International Conference on Urban Health Dhaka 2015. Journal of Urban Health 93: 526–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emina, Jacques, Donatien Beguy, Muindi Zulu Eliya, Alex Ezeh, Kanyiva Muindi, Patricia Elung’ata, John Otsola, and Y. Yé. 2011. Monitoring of Health and Demographic Outcomes in Poor Urban Settlements: Evidence from the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System. Journal of Heredity 88: S200–S218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Ruth. 2005. Social Networks, Migration, And Care in Tanzania. Journal of Children And Poverty 11: 111–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, Alex, Oyinlola Oyebode, David Satterthwaite, Yen-Fu Chen, Robert Ndugwa, Jo Sartori, Blessing Mberu, G. J. Melendez-Torres, Tilahun Haregu, Samuel Watson, and et al. 2017. The History, Geography, and Sociology of Slums and the Health Problems of People Who Live in Slums. The Lancet 389: 547–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairey, Tiffany. 2018. Whose Photo? Whose Voice? Who Listens? ‘Giving’, Silencing and Listening to Voice in Participatory Visual Projects. Visual Studies 33: 111–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis-Chizororo, Monica. 2010. Growing up without Parents: Socialisation and Gender Relations in Orphaned-Child-Headed Households in Rural Zimbabwe. Journal of Southern African Studie 36: 711–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaciuki, Perpetua. 2010. Child Headed Households, The Emerging Phenomenon in Urban Informal Settlements: A Case Study of Kibera Slum Nairobi-Kenya. Master’s thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, Nicola, Gemma Heath, Elaine Cameron, Sabina Rashid, and Sabi Redwood. 2013. Using the Framework Method for the Analysis of Qualitative Data in Multi-Disciplinary Health Research. BMC Medical Research Methodology 13: 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Kenya. 2011. Kenya National Social Protection Policy. Nairobi: Government of Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Kenya. 2017. Kenya Social Protection Sector Review. Nairobi: Government of Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Robort, Patrical Kitsao-Wekulo, Sunil Bhopal, Elizabeth W. Kimani-Murage, Hill Zelee, and B. R. Kirkwood. 2020. Nairobi Early Childcare in Slums (Necs) Study Protocol: A Mixed-Methods Exploration of Paid Early Childcare in Mukuru Slum, Nairobi. BMJ Paediatrics Open 4: E000822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakulu, Stephen. 2008. Challenges Facing Orphaned and Vulnerable Children in Accessing Free Primary Education in Kenya: A Case of Embakasi Division. Nairobi: University of Nairobi. [Google Scholar]

- Kanyi, Nancy. 2019. Social and Economic Constrains Affecting the Welfare of Households Headed by Children. In Mathare Slums, Nairobi City County. Nairobi: Kenya University of Nairobi. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. 2021. Kenya Integrated Household Budget Survey 2015–2016. Nairobi: KNBS. [Google Scholar]

- King, Megan, Vivian Renó, and Evlyn Novo. 2014. The Concept, Dimensions and Methods of Assessment of Human Well-Being within a Socioecological Context: A Literature Review. Social Indicators Research 116: 681–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurebwa, Jeffrey, and Nyasha Kurebwa. 2014. Coping Strategies of Child-Headed Households in Bindura Urban Zimbabwe. International Journal of Innovative Research and Development 3: 236–49. [Google Scholar]

- Le, Trang Mai, and Nilan Yu. 2021. Sexual and Reproductive Health Challenges Facing Minority Ethnic Girls in Vietnam: A Photovoice Study. Culture, Health & Sexuality 23: 1015–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux-Kemp, Andra. 2013. Child Headed Households in South Africa: The Legal and Ethical Dilemmas When Children Are the Primary Caregivers in a Therapeutic Relationship. In People Being Patients: International, Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Edited by Peter Bray and Diana Mak. London: Inter-Disciplinary Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Veronica C., Patrick Muriithi, Ulrike Gilbert-Nandra, Andrea A. Kim, Mary E. Schmitz, James Odek, Rose Mokaya, Jennifer S. Galbraith, and KAIS Study Group. 2014. Orphans and Vulnerable Children in Kenya: Results from a Nationally Representative Population-Based Survey. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 66: S89–S97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhout, Partick, Truus Teunissen, and Genserik Reniers. 2021. What about Using Photovoice for Health and Safety? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 11985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenson, Rene, and Marie Masotya. 2018. Pathways to Urban Health Equity Report of Multi-Method Research in East and Southern Africa. Harare: Civic Forum on Human Development and Lusaka District Health Office. [Google Scholar]

- Makuyana, Abigail, Shingirai P. Mbulayi, and Mbulayi Kangethe Shingirai. 2020. Psychosocial Deficits Underpinning Child Headed Households (Chhs) in Mabvuku and Tafara Suburbs of Harare, Zimbabwe. Children and Youth Services Review 115: 105093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollum, Rosalind, Sally Theobald, Lilian Otiso, Tim Martineau, Robinson Karuga, E. Barasa, Sassy Molyneux, and M. Taegtmeyer. 2018. Priority Setting for Health in the Context of Devolution in Kenya: Implications for Health Equity and Community-Based Primary Care. Health Policy and Planning 33: 729–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. 2018. Kenya AIDS Response Progress Report 2018; Saint Vincent and the Grenadines: Ministry of Health.

- Mogotlane, Sophie Mataniele, Chauke Motshedisi, van Rensburg Gisela, Human Sarie, and Kganakga Mokgadi. 2010. A Situational Analysis of Child-Headed Households in South Africa. Curationis 33: 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, Wisdom. 2013. Causes and Effects of Poverty on Academic Achievements of Rural Secondary School Students: Case of Tshazi Secondary School in Insiza District. International Journal of Asian Social Science 3: 2104–13. [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP). 2015. Guidelines for Conducting Adolescent Hiv Sexual and Reproductive Health Research in Kenya. Nairobi: National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP). [Google Scholar]

- Ndeda, Mildred. 2013. The Gendered Face of Orphanhood: The Double Vulnerability of Female Orphans in Child-Headed Households in Kisumu East District. Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est/The East African Review 46: 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, Lorelli S., Jill M. Norris, Deborah E. White, and Nancy J. Moules. 2017. Thematic Analysis:Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16: 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykiforuk, Candace, Vallianatos Helen, and Nieuwendyk Laura. 2011. Photovoice as a Method for Revealing Community Perceptions of the Built and Social Environment. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 10: 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, Jace. 2016. Problematising Child-Headed Households: The Need for Children’s Participation in Early Childhood Interventions. South African Journal of Childhood Education 6: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipa, Tony, and Conroy Caroline. 2020. Leave No One Behind Time for Specifics on the Sustainable Development Goals. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ronzi, Sara, Puzzolo Elisa, Hyseni Lirije, Higgerson James, Stanistreet Debbi, Hugo Mbatchou, Bruce Nigel, and Pope Daniel. 2019. Using photovoice methods as a community-based participatory research tool to advance uptake of clean cooking and improve health: The LPG adoption in Cameroon evaluation studies. Social Science & Medicine 228: 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevelius, Jae, Gutierrez-Mock Luis, Zamudio-Haas Sophia, McCree Breonna, Ngo Azize, Jackson Akira, Clynes Carla, Venegas Luz, Salinas Arianna, Herrera Cinthya, and et al. 2020. Research with Marginalized Communities: Challenges to Continuity During the COVID-19 Pandemic. AIDS and Behavior 24: 2009–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet. 2017. Health in Slums: Understanding the Unseen. The Lancet 389: 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwala, S’lungile. 2018. Experiences and Coping Strategies of Children From Child-Headed Households in Swaziland. Journal of Education and Training Studies 6: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Un-Habitat. 2020. World Cities Report 2020: The Value of Sustainable Urbanization. Nairobi: UN-Habitat. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2017. Leaving No-One Behind: Equality and Non-Discrimination at the Heart of Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Van Breda, Adrian D. 2010. The Phenomenon and Concerns of Child-Headed Households in Africa. In Sozialarbeit des Südens, Band III: Kindheiten und Kinderrechte. Edited by Manfred Liebel and Ronald Lutz. Oldenberg: Paolo Freire Verlag, pp. 259–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Caroline. 1999. Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. Journal Womens Health 8: 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Caroline, and Cheri Pies. 2004. Family, Maternal, and Child Health through Photovoice. Maternal and Child Health Journal 8: 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Caroline, Burris Mary, and Ann Burris. 1997. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior 24: 369–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, Laura, and Carola Eyber. 2009. Resiliency of Children in Child-Headed Households in Rwanda: Implications for Community Based Psychosocial Interventions. Intervention 7: 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Sarah. 2009. Analyzing Wellbeing: A Framework for Development Practice. In Wellbeing in Developing Countries. Bath: Bath University. [Google Scholar]

- White, Sarah. 2010. Analysing Wellbeing: A Framework for Development Practice. Development in Practice 20: 158–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiftachel, Oren. 2009. Theoretical Notes on ‘Gray Cities’: The Coming of Urban Apartheid? Planning Theory 8: 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).