Abstract

In this technology-driven era, the digitalization of social work practice is becoming almost mandatory in many countries, especially in Europe. Within this context, it is important to look at the possibilities and challenges for the digitalization of critical reflection, which is a fundamental part of social work practice. Using a conceptual and theoretical framework based on reflective practice, critical reflection, and experiential learning, this article aims to outline and discuss the use of ATLAS.ti software as a supporting tool in digitalizing critical reflection in social work supervision (SWS). For illustrative purposes, a case example of child welfare from Sweden is used. This article considers both the benefits and challenges of using ATLAS.ti as a technological tool for the digitalization of critical reflection in SWS. It concludes that social workers’ autonomy and wellbeing need to be at the center in deciding about the use of digital tools such as ATLAS.ti in SWS.

1. Introduction

Digitalization—a process of integrating informational and communication technologies—is transforming almost every aspect of human life. In this technology-driven era, digitalization has therefore become almost mandatory within social work in many countries. Consequently, social work in many parts of the world has gradually moved toward the incorporation of new digital tools in its education, practice, and research (Lagsten and Andersson 2018; Peláez and Marcuello-servós 2018; Taylor 2017). The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the process of digitalization in social work (Papouli et al. 2020; Watters and Northey 2020). Within the process of digitalization, a recent report from Europe has urged providers of social services to explore and analyze the benefits and challenges of digital technologies in improving the delivery and management of social work (Eurofound 2020). In this regard, educators and practitioners are currently exploring and evaluating different digital tools that could further enhance social work education and practice.

One specific area of social work that could be benefited from the use of digital technologies is the Social Work Supervision (SWS). SWS can be conducted in many forms such as coaching, mentoring and consultation, with different emphases placed on its key functions—such as normative/administrative, formative/educational and restorative/supportive (Bradley and Engelbrecht 2010; Kadushin and Harkness 2002). The core purpose of SWS is to ensure that risks are managed effectively, and interventions are based on knowledge derived from accumulated theoretical and practice-based accounts for promoting professionalism in social work (Spolander et al. 2014). SWS is in fact considered as one of the key elements in enabling frontline social workers to enhance their professional development in providing responsive quality care and services (Bourn and Hafford-Letchfield 2011; Noble and Irwin 2009; Tsui 2005).

For SWS to fulfill its learning and support functions, it must include the process of reflective practice (Busse 2009; Rankine 2019). Reflective social work practice, which is broadly defined as making reflection in, on, and about social work situation(s) and intervention(s), is crucial for the process of enhancing the quality of work. It is essentially considered as an educative practice with potential learning situations for practitioners to learn, grow, and develop in and through their practice (Ferguson 2018). A reflective social work practitioner therefore needs to engage with knowledge that emerges from critical reflection on the practice itself (Fook 2002). Critical reflective practice incorporates both critical thinking and critical reflection (Pawar and Anscombe 2015). According to Askeland and Fook (2009), critical reflection is an ability to think critically, and is an integral part of critical practice. In particular, critical reflection allows the integration of theory and practice in creative and complex means to promote the creation of a knowledge base in social work (Fook 2002). SWS is therefore a professional space where social workers develop and enhance their competencies through critical reflection (Rankine 2019).

The debate on SWS has largely focused on experiences of social workers in the roles of supervisor and supervisee, the activity of supervision itself, and the context within which supervision takes place (Davys et al. 2017; O’Donoghue et al. 2018). Currently, more discussions are required on digital tools for enhancing critical reflection within SWS. In fact, contemporary SWS is lacking tools for digitalizing critical reflection (Saltiel 2017). Digital tools can promote the accountability of critical reflection in SWS. Accountability, which is the duty and responsibility to justify professional actions and the knowledge base of social work practice, has become a norm in many European countries (Banks 2013). SWS entails not only the advocacy of critical reflection but also fosters its accountability as a basis for practice-based knowledge. Accountability has its share of benefits as it protects both public and service users from exploitative and oppressive social work practices. In principle, professional accountability is considered crucial in developing competence, demeanor, and ethical social work practice (NASW and ASWB 2013). In this sense, there is a need to explore possibilities for SWS to be a place of critical reflection and professional development so that it does not remain dominantly a space for organizational control, but rather a practice that promotes knowledge development and accountability (Beddoe 2010; Davys et al. 2017; O’Donoghue et al. 2018).

This article thus considers the benefits and challenges of ATLAS.ti software as a technological tool for accounting and enhancing critical reflection within SWS. In particular, this article makes use of a case-study on SWS in a child welfare case from Sweden to (1) demonstrate how critical reflection can be digitalized and, (2) how the critical reflections can be accounted for using ATLAS.ti software. ATLAS.ti software is primarily a tool for supporting qualitative data analysis, but it can also be used as a digital platform for enhancing and accounting critical reflection in the practice of SWS. In fact, ATLAS.ti is built on the learning principles of Noticing, Collecting and Thinking (NCT) (Friese 2019). Anything noticed from the practice of supervision can therefore be collected as a basis for critical thinking and reflection. Details on the features and capabilities of the software can be found from the free manual and video tutorials available at http://atlasti.com (accessed on 2 October 2020). Readers of this article are therefore referred to the ATLAS.ti’s manual and/or video tutorials for more in-depth information on the use and application of the software.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

SWS incorporates learning and support functions which includes the giving and receiving of constructive feedback based on critical reflection to create an atmosphere of self-improvement as well as a strong sense of security while contributing to organizational objectives (Bourn and Hafford-Letchfield 2011). Its purpose is also intended to ensure that risks are tackled effectively, and that interventions are based on knowledge derived from accumulated account of experiences for promoting professionalism (Bradley and Engelbrecht 2010; Ornellas et al. 2018). In particular, Beddoe (2010) opines that the integrity of supervision might be threatened when it is lacking the learning-focused activities. In addition, “good quality supervision” is often mentioned as one that goes beyond case and task management to offer developmental and emotional support in a safe space and makes valuable contribution in developing reasoning skills and more deliberative analyses based on Experiential Learning (EL) (Rankine 2019; Saltiel 2017; Zorga 1997).

EL is regarded as a holistic integrative theory on learning that combines learning based on experiences, perceptions, observations and reflections. Kolb (1984, 2015) presents an EL model on how different people learn by integrating their practical experiences with reflections. Kolb’s view is that learning is a cycle that perpetuates more learning based on continuous reflection. In particular, Kolb’s experiential model has become quite popular within SWS (Cheung and Delavega 2014). For Kolb (1984, 2015), learning is a process where knowledge is and required to be created through the transformation of experience. He therefore argues that learning should be conceived as a holistic process grounded on experiences, and not to be looked at from an outcome’s perspective (Kolb 1984, 2015). According to Kolb’s (1984) EL model, learning process from practice exposure takes place through a cyclical process with the following four distinct phases: (1) feeling—through being involved in concrete experience (2) watching—making reflective observation (3) thinking—abstract construction of concepts and (4) doing—making active experiment. The learning process in Kolb’s illustration can begin at any phase, but it should pass through all the four phases for EL to be completed (Zorga 1997). In Kolb’s EL theory, there are two primary axes: A concrete experience- abstract conceptualization dimension; and an active experimentation-reflective observation dimension (Healey and Jenkins 2000). Kolb’s EL theory is closely related to Donald Schon’s theorization on reflective practice which requires deriving knowledge from practical experiences (Pawar and Anscombe 2015).

Reflective practice is generally based on Schon’s “reflection in action” and “reflection on action” for integrating knowledge derived from practice with theory rather than only applying theory to practice (Askeland and Fook 2009; Pawar and Anscombe 2015). From Schon’s perspective, reflective practice is a learning space where professionals use reflection to deal with the risks and uncertainties surrounding their work to help shape their thinking and provide justification for their actions in improving practice (Ferguson 2018). Reflective practice therefore focuses on the improvement practice, which makes its strength (Béres and Fook 2020). In essence, Day (2000, p. 118) identifies the following five kinds of reflections in any reflective practice: the holistic, where the emphasis is upon the context and content; the pedagogical (on and in action), in which emphasis is upon learning from theories, methods, field interactions, facts, and past experiences; the interpersonal, where the focus is on group dynamics, relationship building, and networking; the strategic, where the focus is on ethical, effective, and efficient means of achieving set goals; and the intrapersonal, where reflexivity is critical. Reflective practice therefore incorporates reflexivity, and it essentially means making reflections on the process of knowledge construction with regard to awareness of self in relation to others involved in creating knowledge within the practice (Béres and Fook 2020; Sheppard et al. 2000).

Reflective practice goes hand in hand with critical refection. According to Rankine (2018), reflective practice provides a professional process for developing self-awareness and considering alternative plans for action, whereas critical reflection assists practitioners to examine power relationships, challenge assumptions and to critique existing social structures. According to Askeland and Fook (2009), critical reflection is based on Mezirow’s (2003) approach that requires reflection on a deep and assumptive level that promotes transformative learning from practice. In particular, critical reflection creates awareness on how conditions and experiences are influenced by certain underlying and sometimes unquestioned assumptions, values, beliefs, forces, power, and practices inherent in society. It enhances motivation to find new ways of working, re-energizing interest and commitment to the job, and finding new strategies and options to deal with longstanding dilemmas in social work (Fook and Askeland 2006). Critical reflection is therefore a transformative method for engaging in the creation of knowledge entailing deep change of perspective (Béres and Fook 2020). Mezirow (2003) argues that transformative learning is understood as a form of metacognitive reasoning that provides arguments for supporting beliefs that result in making decisions to act in bringing required changes. Transformative learning requires the use of a prior interpretation based on what is already known to construe a new or revised interpretation of one’s experience on what is being known as a guide to the future knowledge-based actions for bringing transformative changes (Mezirow 2000). Most often, SWS is considered as the ideal professional space of transformative learning through critical reflection on the wider social work environment (Rankine 2018).

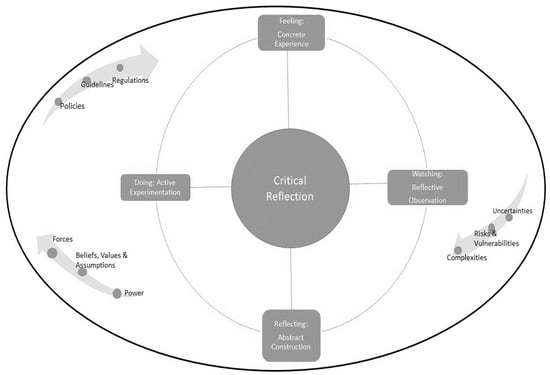

Figure 1 represents the complex environment within which the practice of SWS takes place. Within the process of SWS, policies, guidelines, and regulations need to be followed carefully. The SWS practice also requires dealing with uncertainties, risks, vulnerabilities as well as different forms of complexities related to managerial, procedural, ethical, and technical responsibilities (Banks 2004). Moreover, various societal forces, beliefs, values, assumptions and power structures, influence the whole process of social work practice and its supervision (Fook 2002). In the context of EL, the benefits and challenges of digital technologies in facilitating and enhancing critical reflection within SWS has to consider such a complex environment as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The framework of environment within which the practice of SWS takes place.

Digital technologies have been developed and used constantly to facilitate the learning and practice of social work (Berzin et al. 2015; Nadan et al. 2020; Reamer 2018; Watters and Northey 2020). Digital technologies such as various types of data management systems, online learning platforms and web-based conferencing tools present excellent opportunities for enhancing critical reflection to promote transformational learning in SWS. However, Fook (2015) emphasizes that it is not technology, which is important in the use of critical reflection for learning purposes; rather, it is much more about the approach that can promote knowledge development through the use of technology. It is therefore imperative to study how digital technologies can support and improve EL in undertaking critical reflection in SWS. A quick literature search on various academic databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar reveals that to-date there is no published studies on the use of digital technologies for enhancing critical reflection in SWS. Latest emerging studies have mostly focused on looking at the overall benefits of using new technologies in online clinical supervision practice in a more general manner (Nadan et al. 2020; Watters and Northey 2020; Woo et al. 2020). Hence, this article attempts to contribute to closing such a gap that exists within social work discourses by focusing on an approach in using ATLAS.ti as a digital tool in enhancing critical reflection in SWS.

3. The Case Study: Mira

In this article, a case study on SWS from Sweden is used as material to illustrate a possible method on how digitalization of critical reflection using ATLAS.ti version 9 software could be carried. The case study presented below is anonymized with fictitious names.

Mira is a 7-year-old girl who has been living in a foster family for the last four years. Before that, she lived with her biological parents and two cats. The family had a poor social network and no contact with relatives. Mira became a case of social services after an animal protection association was called to the house because of a neighbor’s complaint about the two cats. The attending animal protection staff suspected Mira as a neglected child, and reported her case to social services. Social services and police inquiries revealed that Mira had spent most of her life in her crib in the apartment, with almost no social interaction with anyone, including even her parents. Consequently, Mira suffered from personal attachment difficulties as well as trauma. She was underdeveloped—both physically and emotionally—which carried numerous long-term consequences. The social services investigation also revealed that Mira’s parents were not able to provide for her basic needs. The assigned social worker—filed a case in accordance to “The Care of Young Persons (Special Provisions) Act. 1990:272”, and through a court decision placed Mira into foster care. Four years later, Mira’s parents demanded to get her back, and therefore a new investigation was started. This case was assigned to Ben, a social worker, and he had Anna as his social work supervisor.

4. Illustration and Discussions

In this article, the illustrations and discussions on the digitalization of critical reflection in SWS is organized in two parts based on Kolb’s EL axes: concrete experience—abstract conceptualization dimension, and active experimentation—reflective observation dimension. In addition, the discussion is also grounded on the theorizations related to reflective practice and critical reflection as outlined in the theoretical and conceptual framework section of this article.

4.1. Concrete Experience—Abstract Conceptualization Dimension

Applying Kolb’s (1984) theoretical perspective, abstract conceptualization within the social work practice is considered as a specific period during which social workers try to make sense of their experiences and get involved in interpreting the events through critical reflection. During the abstract conceptualization process, social workers (both supervisor and supervisee) make critical reflections on various concepts that represent a mental construction of reality (Bisman 1999). During supervision, the supervisor and supervisee are particularly involved in the process of abstract conceptualization from available information on various aspects of social work practice such as existing theories, approaches, methods, skills, techniques, contexts as well as supervisor’s and supervisee’s own reflexivity.

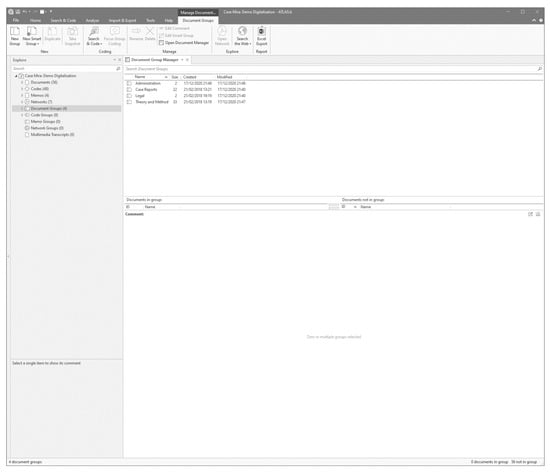

The concrete experience is the case of Mira and the abstract conceptualization is, let us say, related to social work interventions in meeting Mira’s basic needs. When the social worker (Ben) and his supervisor (Anna) are assigned Mira’s case, the social work practice and interventions to solve the problems and issues related to Mira become a new concrete experience for them. Both Ben and Anna were required to gather preliminary background information and create an information system related to the case. An information system based on digital technology has the potential to amplify abilities of social workers, and to enhance effectiveness and efficiencies in SWS (Gillingham 2015; Johnson et al. 2001). In ATLAS.ti v.9.0, an information system related to the case of Mira is therefore created as a New Project. The New Project is given a name (in this case, it is labeled as Case Mira). Under the project—Case Mira—different documents containing vital information to manage Case Mira are gathered and classified under different “Document Groups” such as case reports, legal documents, administrative material, etc. (as shown in Figure 2). For information on how to create a project and organize documents in ATLAS.ti, refer to the ATLAS.ti v.9.0 manual (Friese 2020).

Figure 2.

Example of documents in ATLAS.ti.

Within the process of SWS, social workers and their respective supervisors are required to gather of all necessary information related to the case. For instance, Ben and Anna gathered all case information about Mira and her parents as well as other material, such as minutes of meetings/reports, police records, court decisions and medical reports in ATLAS.ti, under the project—Case Mira. They then coded all the uploaded documents. Technically, coding means assigning a label to a segment of data within ATLAS.ti, that is, indexing (Friese 2019); which helps in organizing essential aspects related to the project to be used as a basis for supporting/guiding critical reflection, as well as for rapid retrieval for referencing and reporting purposes. Coding is an interpretive indexing process that allows Ben and Anna to capture the essence of the data. For this reason, a code is usually given an appellation that captures the meaning of the material described (written and saved) and organized according to their source and function. For instance, in Case Mira Ben and Anna organized codes, such as Positive Parental Behavior, Negative Parental Behavior, Risk Factors, Safety Factors, etc., under a Code Group labeled as “Social Work Assessment”. Similarly, Ben and Anna organized another Code Group labeled as Legal Regulations, which contains all codes for reviewing legal documents related to Case Mira. Still another Code Group based on theory from literature review called Anti-Oppressive Practice was created by Ben and Anna, to capture essential aspects for guiding anti-oppressive practices in Case Mira. More information related to coding and group codes in ATLAS.ti can be found in the manual (Friese 2020).

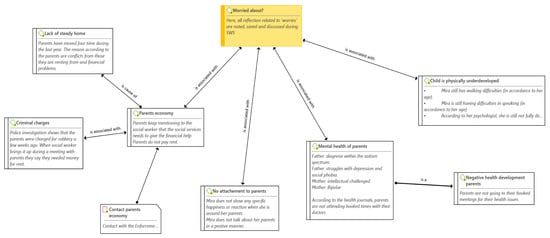

The digitalization of such background information on the case is important in critical reflection for accounting, validating, and testing abstract construction in planning and undertaking possible social work interventions. For experience learning to take place, Ben and Anna needed to undertake critical reflections in a “concrete” way to think “abstractly” on how to proceed with their intervention using logic and reason based on the information and material gathered and organized in ATLAS.ti. After the process of coding, Ben and Anna applied the feature Networks in ATLAS.ti, with the purpose of increasing the prospect of abstract conceptualization on possible social work interventions. Networks are graphical interpretations of a part of the project Case Mira. In ATLAS.ti, networks are central to the digitalization of critical reflections in SWS. The aim of using the Network feature in ATLAS.ti is to digitalize and make visible critical thoughts—deliberately or instinctively—and to allow further exploration of relationships between different facts, occurrences, observations, and reflexivity (Friese 2019). For example, in Case Mira, the Networks feature in ATLAS.ti offers a possibility to undertake and record critical reflections on the Assessment and Planning (label assigned to a Network in ATLAS.ti). Ben and Anna then created a network called Assessment and Planning, with codes such as “Worried about”, “Working well”, and “Needs to happen”. Under each code, Ben and Anna recorded their notes (basic facts and information) that would guide them in undertaking critical reflections. Therefore, this is one of the steps toward the digitalization of critical reflection in SWS using ATLAS.ti. See Figure 3 as an example on how codes, links, and notes related to a network could be recorded and generated. Links are connections showing relationships between codes. Figure 3 establishes the network with codes and notes related to an SWS session, where the focus is on issues that Ben was “Worried about”. It is worth noting that Figure 3 presents a partial snapshot generated in ATLAS.ti. In reality, the network could be a complex environment, with several codes having extensive notes. However, it is possible to generate and retrieve only partial coded materials that the supervisor and supervisee need to focus on during an SWS session.

Figure 3.

Example of a network with codes, notes, and links.

4.2. Active Experimentation—Reflective Observation Dimension

According to Kolb’s (1984, 2015) EL model, active experimentation is rather regarded as—a phase where constant monitoring of the “trials” is vital within the process of supervision for achieving the “best practice”. In this endeavor, the role of a supervisor in the process of EL is to moderate and guide the supervisee toward a safe and ethical experimentation through jointly carried out critical reflections (Kadushin and Harkness 2002; Zorga 1997). In such tasks, reflective observation can provide a useful focus in learning when critical reflections on observations are made and recorded jointly by both supervisor and supervisee. Thus, it is vital that reflective observations on active experimentations are digitalized scientifically for learning, making future references, promoting accountability, and, above all, for legitimizing the knowledge created during the process. Active experimentation, in this particular case, means that new ideas that have been discussed during supervision need to be experimented as social work interventions. It is generally argued that social problems related to case management are best understood through critical reflection during active experimentation of solutions (Gates 2015). Active experimentation of ideas/solutions based on the critical reflections of social problems/issues is therefore central to the creation of practice-based wisdom (Trevithick 2005). Such practice-based knowledge needs to be legitimized through scientific methods for embedding it in the teaching, learning, and management domains of social work (Fook 2002).

In ATLAS.ti, reflective observation on active experimentation (as well as on concrete experiences and abstract construction) can be further digitalized using the Memos feature. Technically speaking, a Memo is a writing template/space in ATLAS.ti (Friese 2019), where observations on active experimentation can be integrated for enhancing critical reflections. Memos are often used in the process of supervision mostly as a communication material (Kadushin and Harkness 2002); however, they are rarely integrated in a holistic manner in promoting EL. In ATLAS.ti, Memos are classified in groups depending on their source and/or purpose. For instance, Day’s (2000, p. 118) classification of reflective practice can be used to create different “Memo Groups”, such as: “Critical Reflection: Pedagogical”, “Critical Reflection: Strategic”, “Critical Reflection: Intrapersonal”, “Critical Reflection: Interpersonal”, and “Critical Reflection: Holistic”.

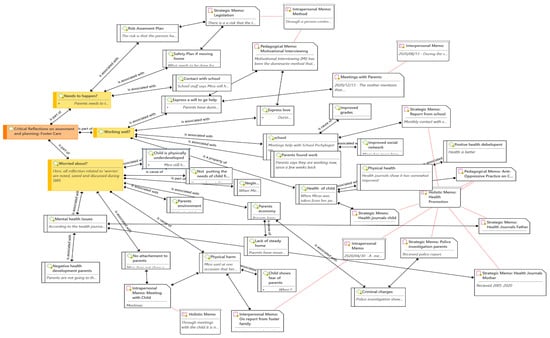

In Case Mira, Ben and Anna recorded all of their critical reflections related to active experimentations and observations, for instance, on the “Assessment and Planning” regarding foster care. The critical reflections made during the SWS sessions are digitalized in ATLAS.ti using the Memo and the Network features. Figure 4 shows a snapshot example of the network of “Assessment and Planning” related to critical reflection regarding observations made during the experimentation of foster care. As observed in Figure 4, different types of memos—pedagogical, strategic, holistic, intrapersonal, and interpersonal—containing critical reflections are linked to various types of Codes with important notes/information for assisting the process of critical reflections in SWS. Therefore, the memos contain notes and reports related to the critical reflections made at different stages during the process of SWS. The gathered information in the codes and memos can be retrieved, displayed, and printed (if required) by clicking on different icons in ATLAS-ti. Critical reflection requires much more than simply thinking about experiences, it involves a critique on the assumptions on which our beliefs and values have developed (Hickson 2011; Mezirow 2003). As Fook (2015) puts it, critical reflection entails deconstruction and reconstruction of the case, the roles and the responsibilities of stakeholders involved in the case as well as the power dynamics, values, beliefs, ideologies, and theories involved in the practice. In this endeavor, the Memos in ATLAS.ti is an ideal feature for facilitating the Noticing, Collecting and Thinking (NCT) involved in the reconstruction and deconstruction tasks in making and using critical reflection in SWS.

Figure 4.

Example of a network on critical reflection with codes, notes, memos, and links.

As observed in Figure 4, by clicking some buttons in ATLAS-ti, Ben and Anna could work on making deep critical reflections assisted by a panoply of digitalized information through network, and codes—containing vital notes, and memos—where different types of critical reflections are organized and recorded. The digitalized critical reflection based on facts and information gathered and organized in ATLAS.ti enhances the reconstruction and deconstruction tasks, and promotes the accountability of social work interventions and practices in Case Mira. The digitalized critical reflection supports the justification of professional actions and the knowledge-base of social work interventions and practices undertaken by Ben and Anna. Finally, digitalization through ATLAS.ti allows Ben and Anna to enhance embedded critical reflections in the case management and promoting the learning culture in SWS.

The management of the information processed by supervisee (Ben) and supervisor (Anna) with this software contributed in having quick access to well-structured and organized information for making informed decisions and interventions in Case Mira. ATLAS.ti was used as a key digitalized database system that allowed Ben and Anna to gather, organize, and manage a large quality of information from different sources. In particular, the software acted as a “container” keeping all the information, codes, notes, and memos for and with critical reflection, thus making it easier for the next supervision session. It helped supervisee(s) and supervisor(s) to manage, extract, compare and explore rapidly the vital information based on and for critical reflections that are essential in helping social work service users and providers. ATLAS.ti enhances critical reflection, which is an essential element for ensuring the quality of social work. ATLAS.ti was used to generate outputs on various key aspects such as from various reports and key legislations that were used in making decisions and planning informed interventions by social worker-Ben. For instance, Figure 4 shows an example of the output generated on “‘Assessment and Planning Foster Care”. As presented in Figure 4, the boxes in ATLAS.ti software can be clicked on to generate further detailed information that has been gathered and saved under each of them. In Case Mira, Ben and Anna were able to get quick access to a well-structured and organized data (as shown in Figure 4) for treating and solving various issues (for instance, making informed decisions regarding foster care for Mira).

One of the central concrete effects of using ATLAS.ti in Case Mira was the personal and professional development of Ben as a social work with the support of Anna (supervisor). ATLAS.ti was not only a digital platform for managing information but also a transformative learning platform that was incorporated with key information that helped Anna to guide Ben’s professional development as a social worker. The ability to critically reflect and make in-depth analysis of experiences and to develop, substantiate, and evaluate knowledge is a key component in a person’s professional development (Colomer et al. 2020). In case Mira, ATLAS.ti was used as a capability-enhancing tool for facilitating the in-depth analysis of facts and experiences gathered in the software that played a vital role in Ben’s professional development. Ben enhanced his skills on case analysis, and got to learn about problem-solving strategies through exploring key facts/information and navigating through different possible options in a digitalized environment that supported him and Anna in the process of making critical reflections.

In addition, ATLAS-ti played a central role in developing professional identity and self-understanding of both Ben as a social worker and Anna as a social work supervisor. Personal identity and self-understanding focus on how professionals perceive themselves in terms of their self-image, self-esteem, task perception, job motivation and views on future perspectives (Engelbertink et al. 2021; Kelchtermans 2009). Professional self-understanding impacts how social workers view their work, give meaning to it and take actions (Kelchtermans 2009). ATLAS.ti as a digital platform allowed Ben and Anna to work together in co-creating problem-solving skills and knowledge through recording and saving various types of critical reflections (pedagogical, strategic, interpersonal, intrapersonal and holistic) and linking them with various sources of information. It also facilitated Ben and Anna to quickly retrieve their critical reflections (saved as Memos in ATLAS.ti) and generate outputs (for instance, as the network shown in Figure 4), on the observations, material and information used in making in-depth analysis during the process of critical reflections. Table 1 provides examples of areas of observation and associated reflections (pointwise). Such observations and reflections were digitalized using ATLAS.ti.

Table 1.

Examples on Areas of Observation and Associated Reflections.

5. Implications for Practice

Social work practice is constantly undergoing the process of digitalization. From this perspective, the knowledge generated during critical reflection within the SWS process also needs to be digitalized. ATLAS.ti presents an appropriate digital platform for digitalizing critical reflection in SWS. A digital platform is a vital component of managing information and communication in making informed decisions in SWS (Lagsten and Andersson 2018). In an era driven by evidence-based practice discourses, the digitalized materials support re-conceptualizing SWS, with more focus on promoting critical reflection-based practice evidence for professional development.

In particular, ATLAS.ti has a panoply of features and capabilities that can be used to gather, organize, retrieve, and analyze in making critical reflections. The functions and capabilities in ATLAS.ti allow SWS data to be retrieved, linked, and generated rapidly and can be shared digitally in a safe and secure manner—through password protection—between supervisor and supervisee. The digitalized critical reflections from SWS in ATLAS.ti can be used as raw data and evidence in promoting practice-based knowledge. For instance, in Case Mira, Ben and Anna were able to solve practical issues related to making decisions on issues such as ”Family assessment”, “Child custody”, and “Court presentations”. In making such complex evaluations and decisions, Ben and Anna had to involve other professional experts such as psychologists, physicians, and lawyers. Dealing with such issues, requires tremendous amount of commitment and effort in making critical reflections on legislations, management organizations, social work practice knowledge (Bow and Martindale 2009). Practice-based knowledge from critical reflection is essential in examining how inter-professional knowledge is implemented, created and theorized (Trevithick 2005). Such a process is vital in legitimizing knowledge based on critical reflections (Fook 2002).

ATLAS.ti supports in enhancing critical reflections by providing features such as Memos, Linkages, Codes, and Networks for recording different types of critical reflections in an organized manner and by having a better overview on various aspects and issues related to a social work case (for instance, Figure 4). In this way, ATLAS.ti as a digital technology enhances the analytical skills of social workers and their supervisors by enabling them to make and record various observations, explore complex issues by linking them with various possible alternatives and apply critical reflection in an integrated and systematic manner. The whole process of SWS becomes effective and efficient with ATLAS.ti. Information and critical reflections can be rapidly retrieved and reported; changes and amendments on various aspects, such as decisions, legislations and progress made can be easily followed. Most importantly, the software allows making informed decisions based on well-structured and organized information that could be explored in depth just by clicking software buttons.

Yet, one may wonder whether new technological tools such as ATLAS.ti might become an instrument of surveillance, rather than for enhancing SWS. Johns (2001) warns that the process of digitalization could not only let supervision be at a risk of becoming another technology of surveillance, but it might also become an opportunity to shape the practitioner into organizationally preferred ways of practice, even though veiled as being in the practitioner’s best interests. For instance, within the Swedish context, diverge views prevail on supervision as being a regulatory instrument (Hämberg 2013). Particularly in Sweden, there has been criticism regarding the current supervision system as being unclear and ineffective in discovering and dealing with the shortcomings inherent in social services (Hämberg 2013). In this sense, it is therefore better to use digital solutions in SWS through which critical reflections-based knowledge can be captured and used, rather than leaving the supervision system unclear and ineffective. Critical reflection is an important part of SWS, as it enables the understanding of power relationships, navigating oppressive structures, and supporting disadvantaged groups in society (Fook 2015). To engage in critical reflection is often a complex and difficult process to grasp, as it relies on competence, structure, and, foremost a will of the social worker to self-evaluate and desire to change. In this sense, the use of digital technologies, such as ATLAS.ti, in SWS needs to be seen as an avenue of having better knowledge and not as a hindrance in social work practice. However, it is important to acknowledge that producing sound knowledge does not always lead to practice enhancement as many other factors, such as political and personal will/commitment, also affect the move toward achieving the “best practice” in social work (Gray et al. 2009).

Moreover, the use of ATLAS.ti in SWS might be considered as being an additional burden on management as well as staff members. For instance, the software is not free of cost and it requires training of users and administrators, which in turn requires additional resources such as time and finance. Keeping up-to-date and well-organized/indexed critical reflection could also be very challenging and time-consuming, especially with preserving motivation to make regular entries. However, currently, massive resources are being used on paper works that are not necessarily organized and structured in a systematic manner. In addition, resources are also being used in organizing critical reflection tasks through supervision. However, the knowledge generated during such a process is not fully captured and legitimized, resulting in a massive resource and educational loss (Bullock and Colvin 2015).

In addition, some practitioners may feel they are being “forced” to use new technological tools such as ATLAS.ti. Indeed, social workers’ autonomy is a vital factor in determining the positive or negative effects of digitalization and new technologies (Christensen et al. 2019). Not all social workers (including supervisors) advocate for the use of digital tools in social work practice (Csiernik et al. 2013). For instance, some social work practitioners/supervisors prefer to see social work as an art, rather than a science in solving social problems and enhancing human well-being (Gray and Webb 2008; Huss and Sela-Amit 2019). As an art, social work is practiced through intellectual creative intuition, and one might argue that digitalization of SWS poses the risk of diminishing such free and artistic skills. However, Cornish (2017) argues that an effective and distinctly social work culture combines the scrutiny of science with the recognition and articulation of the unique, and can draw effectively and empathically on what each approach has to offer.

To sum up, digitalization of critical reflection with ATLAS.ti software in SWS brings two main categories of advantages to the users. The first category has technical advantages. The software has technical features and capabilities to digitalize vital information and the critical reflections made during SWS. In particular, it enables the users to have a well-organized and well-structured information system on various aspects related to a social work case. The saved information could be easily and rapidly retrieved, reported (as output), and shared between supervisor and supervisee. The second category encompasses the professional development of social workers and social work supervisors. ATLAS.ti creates a digitalized environment that facilitates the process of informed decision-making by having an integrated and holistic view on the social work case, as well as progress and basis of decisions being made/or to be made. For instance, through the network platform provides a sound base for critical reflections, which play important role in transformative learning, and personal and professional development. However, the use of ATLAS.ti in digitalization of critical reflection in SWS has some disadvantages, which are mainly related to resource investment.

6. Limitations and Conclusions

This article is limited to be an introductory proposal of ATLAS.ti as a possible tool for digitalizing critical reflection in SWS. It is beyond the scope of the article to cover such a proposal in breadth and depth with multiple examples. Nevertheless, it is desired that the presentation and discussion made in this article can initiate further continuation toward a more detailed and thorough consideration of the use of ATLAS.ti for digitalizing critical reflection. Moreover, this article is written with the assumption that readers have some basic prior knowledge of ATLAS.ti software or would read and understand the ATLAS.ti manual alongside this contribution. In addition, the proposal made herein needs to be further researched and validated by social work practitioners, supervisors, and top managers through pilot applications of ATLAS.ti in a variety of SWS settings.

In summary, it is concluded that technology such as ATLAS.ti presents an intellectual capital in SWS (King et al. 2017). Through ATLAS.ti, critical refection can be digitalized as organizational and supervisory support and as promotion of practice-based knowledge (King et al. 2017). Using a sound theoretical framework, this article has initiated the first step toward considering the use of ATLAS.ti within the process of SWS. Using a case-study, this article has demonstrated how ATLAS.ti can be utilized by digitalizing critical reflections in SWS. It has also made suggestions on the possibilities offered by the software in knowledge production from practice that can contribute toward both practice-based evidence and evidence-based practice. In sum, this article concludes that ATLAS.ti brings an added value to a paradigm shift towards contemporary technology-based SWS which would be beneficial to enhance the practice of critical reflection.

As the world of social work is constantly changing with the advent of new technologies, social workers need to adjust and adapt in capitalizing on available technologies for innovative approaches and overcome any resistance toward exploring and learning new information technology skills (Bullock and Colvin 2015). New technologies bring along new possibilities for enhancing social work practice. Social workers, therefore, have a duty to explore the possibilities for providing “best practice” to the society. Similarly, Berzin et al. (2015, p. 3) opine: “As the world becomes increasingly reliant on technology, a grand challenge for social work is to harness technological advancements and leverage digital advances for social good”. In particular, SWS has to evolve hand-in-hand with new technological tools for supporting supervision with the best possible management systems that enhance critical reflections. In particular, managing social work is centered on human decisions and not on technologies. In fact, human beings and not technology, decide how practice should be organized, delivered, and supervised. Technology simply provides tools for easing the process of management particularly through supporting systematic ways of organizing gathered information for enhancing the process of decision making toward the search for the “best practice”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.R.; methodology, K.R. & N.N.; software, K.R.; validation, N.N.; formal analysis, K.R. & N.N.; investigation, K.R. & N.N.; resources, K.R. & N.N.; writing—original draft preparation, K.R. & N.N.; writing—review and editing, K.R. & N.N.; visualization, K.R.; supervision, K.R.; project administration, K.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Askeland, Gurid Aga, and Jan Fook. 2009. Critical Reflection in Social Work. European Journal of Social Work 12: 287–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Sarah. 2004. Ethics, Accountability and the Social Professions. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, Sarah. 2013. Negotiating Personal Engagement and Professional Accountability: Professional Wisdom and Ethics Work. European Journal of Social Work 16: 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddoe, Liz. 2010. Surveillance or Reflection: Professional Supervision in ‘the Risk Society’. British Journal of Social Work 40: 1279–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béres, Laura, and Jan Fook. 2020. Learning Critical Reflection. In Learning Critical Reflection Experiences of the Transformative Learning Process. Edited by Laura Béres and Jan Fook. Abingdon: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Berzin, Stephanie Cosner, Jonathan Singer, and Chitat Chan. 2015. Practice Innovation through Technology in the Digital Age: A Grand Challenge for Social Work. Working Paper No. 12. Cleveland: American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Bisman, Cynthia. 1999. Social work assessment: Case theory construction. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services 89: 596–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, Diana, and Trish Hafford-Letchfield. 2011. The Role of Social Work Professional Supervision in Conditions of Uncertainty. International Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Change Management 10: 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bow, James N., and David A. Martindale. 2009. Developing and Managing a Child Custody Practice. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice 9: 127–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, Greta, and Lambert Engelbrecht. 2010. Supervision: A Force for Change? Three Stories Told. International Social Work 53: 773–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, Angela, and Alex D. Colvin. 2015. Communication Technology Integration into Social Work Practice. Advances in Social Work 16: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, Stefan. 2009. Supervision between Critical Reflection and Practical Action. Journal of Social Work Practice 23: 159–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Monit, and Elena Delavega. 2014. Five-Way Experiential Learning Model for Social Work Education. Social Work Education 33: 1070–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Jan Olav, Live Bakke Finne, Anne Helene Garde, Morten Birkeland Nielsen, Kathrine Sørensen, and Jolien Vleeshouwers. 2019. The Influence of Digitalization and New Technologies on Psychosocial Work Environment and Employee Health: A Literature Review. STAMI-rapport No. 2. Oslo: STAMI. [Google Scholar]

- Colomer, Jordi, Teresa Serra, Dolors Cañabate, and Remigijus Bubnys. 2020. Reflective Learning in Higher Education: Active Methodologies for Transformative Practices. Sustainability 12: 3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, Sally. 2017. Social Work and the Two Cultures: The Art and Science of Practice. Journal of Social Work 17: 544–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiernik, Rick, Patricia Furze, Laura Dromgole, and Giselle Marie Rishchynski. 2013. Information Technology and Social Work-the Dark Side or Light Side? Information Technology and Evidence-Based Social Work Practice 3714: 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davys, Allyson Mary, Janet May, Beverly Burns, and Michael O’Connell. 2017. Evaluating Social Work Supervision. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work 29: 108–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, Christopher. 2000. Effective Leadership and Reflective Practice. Reflective Practice 1: 113–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbertink, Monique M. J., Jordi Colomer, Kariene M. Woudt Mittendorff, Ángel Alsina, Saskia M. Kelders, Sara Ayllón, and Gerben J. Westerhof. 2021. The Reflection Level and the Construction of Professional Identity of University Students. Reflective Practice 22: 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. 2020. Impact of Digitalisation on Social Services. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Harry. 2018. How Social Workers Reflect in Action and When and Why They Don’t: The Possibilities and Limits to Reflective Practice in Social Work. Social Work Education 37: 415–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fook, Jan, and Gurid Aga Askeland. 2006. The ‘critical’ in critical reflection. In Critical Reflection in Health and Social Care. Edited by Sue White, Jan Fook and Fiona Gardner. Maidenhead: Open University, pp. 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fook, Jan. 2002. Social Work: Critical Theory and Practice. London: SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fook, Jan. 2015. Reflective Practice and Critical Reflection. In Social Work and Social Care: Knowledge and Theory. Edited by Joyce Lishman. Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley, pp. 440–54. [Google Scholar]

- Friese, Susanne. 2019. Qualitative Data Analysis with ATLAS.ti, 3rd ed. London: SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Friese, Susanne. 2020. ATLAS.ti 9 User Manual. Available online: https://atlasti.com/manuals-docs/ (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Gates, Trevor G. 2015. Valuing Experience in a Baccalaureate Social Work Class on Human Behavior. The Journal of Practice Teaching and Learning 13: 76–85. [Google Scholar]

- Gillingham, Philip. 2015. Electronic Information Systems and Social Work: Principles of Participatory Design for Social Workers. Advances in Social Work 16: 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Mel, and Stephen A. Webb. 2008. Social Work as Art Revisited. International Journal of Social Welfare 17: 182–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Mel, Debbie Plath, and Stephen A. Webb. 2009. Evidence-based Social Work: A Critical Stance. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hämberg, Eva. 2013. Supervision as Control System: The Design of Supervision as a Regulatory Instrument in the Social Services Sector in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration 17: 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, Mick, and Alan Jenkins. 2000. Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory and Its Application in Geography in Higher Education. Journal of Geography 99: 185–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickson, Helen. 2011. Critical Reflection: Reflecting on Learning to Be Reflective. Reflective Practice 12: 829–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, Ephrat, and Michal Sela-Amit. 2019. Art in Social Work: Do We Really Need It? Research on Social Work Practice 29: 721–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, C. 2001. Depending on the Intent and Emphasis of the Supervisor, Clinical Supervision Can Be a Different Experience. Journal of Nursing Management 9: 139–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Elizabeth, James Hinterlong, and Michael Sherraden. 2001. Strategies for Creating Mis Technology to Improve Social Work Practice and Research. Journal of Technology in Human Services 18: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadushin, Alfred, and Daniel Harkness. 2002. Supervision in Social Work, 4th ed. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kelchtermans, Geert. 2009. Who I Am in How I Teach Is the Message: Self-Understanding, Vulnerability and Reflection. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 15: 257–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Sue, Ed Carson, and Lisa Helen Papatraianou. 2017. Self-Managed Supervision. Australian Social Work 70: 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, David A. 1984. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, David A. 2015. Experiential Learning: Experiences as the Source of Learning and Development, 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lagsten, Jenny, and Annika Andersson. 2018. Use of Information Systems in Social Work—Challenges and an Agenda for Future Research. European Journal of Social Work 21: 850–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, Jack. 2000. Learning to Think Like an Adult: Core Concepts of Transformation Theory. In Learning as Transformation. Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. Edited by J. Mezirow and Associates. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, Jack. 2003. Transformative Learning as Discourse. Journal of Transformative Education 1: 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadan, Yochay, Razi Shachar, Daniella Cramer, Tali Leshem, Darylle Levenbach, Rinat Rozen, Nurit Salton, and Saviona Cramer. 2020. In Couple and Family Therapy. Family Process 59: 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NASW, and ASWB. 2013. Best Practice Standards in Social Work Supervision. Available online: http://www.naswdc.org/practice/naswstandards/supervisionstandards2013.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Noble, Carolyn, and Jude Irwin. 2009. Social Work Supervision: An Exploration of the Current Challenges in a Rapidly Changing Social, Economic and Political Environment. Journal of Social Work 9: 345–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, Kieran, Yuh Ju Peace Wong, and Ming-sum Tsui. 2018. Constructing an Evidence-Informed Social Work Supervision Model. European Journal of Social Work 21: 348–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornellas, Abigail, Gary Spolander, and Lambert K. Engelbrecht. 2018. The Global Social Work Definition: Ontology, Implications and Challenges. Journal of Social Work 18: 222–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papouli, Eleni, Sevaste Chatzifotiou, Charalampos Tsairidis, and Eleni Papouli. 2020. The Use of Digital Technology at Home during the COVID-19 Outbreak: Views of Social Work Students in Greece Outbreak: Views of Social Work Students in Greece. Social Work Education 39: 1107–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, Manohar, and Bill Anscombe. 2015. Reflective Social Work Practice: Thinking, Doing and Being. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peláez, Antonio López, and Chaime Marcuello-servós. 2018. E-Social Work and Digital Society: Re- Conceptualizing Approaches, Practices and Technologies. European Journal of Social Work 21: 801–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankine, Matt. 2018. How Critical Are We?: Revitalising Critical Reflection in Supervision. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education 20: 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rankine, Matt. 2019. The ‘Thinking Aloud’ Process: A Way Forward in Social Work Supervision. Reflective Practice 20: 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reamer, Frederic G. 2018. Ethical Standards for Social Workers’ Use of Technology: Emerging Consensus. Journal of Social Work Values & Ethics 15: 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Saltiel, David. 2017. Supervision: A Contested Space for Learning and Decision Making. Qualitative Social Work 16: 533–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, Michael, Steve Newstead, Antonietta Di Caccavo, and Kate Ryan. 2000. Reflexivity and the Development of Process Knowledge in Social Work: A Classification and Empirical Study. British Journal of Social Work 30: 465–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolander, Gary, Lambert Engelbrecht, Linda Martin, Petri Tani, Alessandro Sicora, and Francis Adaikalam. 2014. The Implications of Neoliberalism for Social Work: Reflections from a Six-Country International Research Collaboration. International Social Work 57: 301–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Amanda. 2017. Social Work and Digitalisation: Bridging the Knowledge Gaps. Social Work Education 36: 869–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevithick, Pamela. 2005. Social Work Skills: A Practice Handbook, 2nd ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui, Ming Sum. 2005. Functions of Social Work Supervision in Hong Kong. International Social Work 48: 485–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, Yulia, and William F. Northey. 2020. Online Telesupervision: Competence Forged in a Pandemic. Journal of Family Psychotherapy 31: 157–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Hongryun, Na Mi Bang, Jungin Lee, and Kate Berghuis. 2020. A Meta-Analysis of the Counseling Literature on Technology-Assisted Distance Supervision. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 42: 424–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorga, Sonja. 1997. Supervision Process Seen as a Process of Experiential Learning. Clinical Supervisor 16: 145–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).