Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to assess students’ social representations of forced migration as a relevant social problem in the last year of primary education and the opportunity for its curricular inclusion. The study was carried out by means of a questionnaire, filled in by 6th-year primary education groups (11–12 years old) (n = 70), in a state-supported private school in the city of A Coruña (Galicia, Spain). The questionnaire was supported by three pictures of forced migrations from the media. In this case, the children had to interpret the pictures through a series of questions that sought to investigate their representations, the causes they identify in this social problem, their opinions, and possible solutions. Finally, the opportunity for the inclusion of social problems as curriculum content was addressed. The study shows that the students are in favor of migrants, that they use concepts from the social sciences in their arguments—albeit simple ones, and that they are in favor of the curricular inclusion of social problems, in which they develop representations through different sources of information.

1. Introduction

This paper incorporates in its title the term “social representations”, a fairly common concept in the Didactic of Social Science research. This notion comes from the field of Social Psychology thanks to the pioneering work of Moscovici (1976) and Jodelet (1989) and it takes into consideration the existing relationship between people and their environment.

Araya (2002) notes that “when people refer to social objects, classify them, explain them and, moreover, evaluate them, it is due to the fact that they have a social representation of that object” (p. 11). According to the same author, these representations are formed, first, by the cultural background accumulated by people and society over time, and then by the anchoring mechanisms, i.e., the incorporation of knowledge into representations and the influence of social structures, to which the role of the media and interpersonal relationships must be added (Araya 2002).

Following Pagès and Oller (2007, p. 6), we could define them as “a set of information, opinions, and values that constitute a more or less well-structured ‘pre-knowledge’ that provides explanations, more or less elaborated, about a situation, a present or past event, a problem, a conflict, a subject, etc.”

Therefore, once we are aware of what this concept refers to, we should ask ourselves what the purpose of our attempt to understand these representations is, and more specifically those of pupils in the last year of primary school. The main reason lies in their importance in shaping the teaching-learning process, as it is necessary to detect them to consolidate or modify them, since exploring these representations “is essential for teaching, as learning is considered to be about modifying these representations” (Pagès and Oller 2007, p. 6).

There are recent studies in our area of knowledge on the social representations of a wide range of subjects—especially controversial social issues—most of them carried out by the Autonomous University of Barcelona. In particular, we can highlight the work of Pagès and Oller (2007), who studied the representations of law, justice, and legislation in Catalan students in the 4th year of ESO, concluding that they were shaped outside of the educational system and that they are quite similar to those of adolescents in other European countries. Marolla and Pagès Blanch (2015) approached the representations of women’s history among Chilean secondary school teachers. Sant et al. (2011) examined Catalan teenagers’ representations of democratic participation. Moreover, social representations of immigration were the subject of study in Bergamaschi’s (2011) work, examined alongside attitudes in a comparative survey carried out in France and Italy.

On the process of transformation of social representations, the thesis by Salinas (2017)—which focuses on participation in social problems of the community—is noteworthy. Other studies by Salinas et al. (2016) focus on social representations of citizen participation among Chilean Social Science teachers and primary school students (Salinas and Oller 2017). Moreover, representations of the economic crisis (Olmos et al. 2017; Olmos and Pagès 2017) or contemporary problems in teacher training (Ortega and Pagès 2017) are good examples of the study of social representations around an issue, a problem or some relevant concepts conducted within the field of Social Sciences Didactics.

This study is part of a larger research that addresses the curricular inclusion of social problems among students at different levels of schooling in northwest Spain, more specifically in Galicia. The purpose of the main study is to understand the social representations of forced migration as a social problem among students in the last year of primary education and its curricular inclusion. Following the same line of research, we have also investigated students’ representations at the end of secondary education (García-Morís and Oller 2022), which allows us to compare the results between the studies conducted in both stages.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Purpose of Social Sciences and the Curricular Inclusion of Social Problems

The social approach of Geography and History in Spain gained ground in the last decades of the 20th century within the emerging field of Social Sciences Didactics (Benejam 1992, 1997; Fien 1992; Pagès 1994). This approach, which could be called a critical approach, corresponds to one of the dominant paradigms in research on the teaching and learning of the Social Sciences, but not in educational practice at the primary and secondary level. In the Spanish case, it was first defined from the epistemology of the Didactics of Geography (Benejam 1992, 1997), and later of the Didactics of History (Pagès 1994, based on Evans 1991).

In Spain—in line with what has been defended in other European countries and also in North America (Simonneaux and Legardez 2010)—there is an increasing number of specialists in Social Sciences Didactics who defend the need to orientate the teaching and learning of Social Sciences, Geography, and History towards relevant social problems (Oller 1999, 2011; Santisteban 2009; Pagès and Santisteban 2011b; García-Pérez 2014; Pagès 2016, among others), although this notion is still rare in the classroom.

“A Social Sciences for global citizenship must consider, analyze, and value the possibilities of approaches centered on relevant social problems (RSP), on socially acute questions (SAQ), on everyday life, on controversial issues or on the disciplinary knowledge generated to analyze, interpret, and try to solve all sorts of problems” (Pagès 2016, p. 725).

The VII International Seminar on Teaching Social Studies Research organized by the Autonomous University of Barcelona in 2010 was devoted exclusively to relevant social problems. For this reason, both for an approach to their meaning and a review of this subject in the Spanish and international scene, the work resulting from the conference is an essential reference (Pagès and Santisteban 2011b). In the Anglo-Saxon tradition, the label “relevant social problems” or “controversial issues” is used (Evans and Saxe 1996; Hurst and Ross 2000), while in the more recent French tradition, the term “socially acute questions” is used (Audigier 2001; Tutiaux-Guillon 2011; Legardez 2003; Legardez and Simonneaux 2006; Thénard-Duvivier 2008), both having in common their orientation towards democratic citizenship.

The contribution of the Canadian author Legardez (2003) delimits, from a conceptual point of view, what is encompassed by the concept of “social and historical, socially acute questions”, which are those that are alive in society, in the reference knowledge and educational knowledge. Le Roux (2002) analyzes the approach to Geography and History problems, fine-tuning what we understand by problems.

Although in Spain one might say that curricular research based on relevant social problems is fairly recent, it follows a line that connects with the research initiated at the Autonomous University of Barcelona by Benejam and Pagès on the teaching of contemporary issues (Benejam 1997). The research carried out at the UAB was closely related to this approach, as it focused on democratic political education, education for citizenship, problems related to everyday life, the development of historical awareness, and the shaping of temporality with a special emphasis on the future (Pagès and Santisteban 2011a). The connection between social problems and social and civic competence is key in this approach.

In the Spanish case, due to the legislative changes that took place in education during the democratic period, it is impossible not to link this approach to the debate on Education for Citizenship or on the key competences, especially social and civic competences, as was the case in the European context. This competence should be connected with the critical approach to Social Sciences, since—although competences are dealt with in all areas of the curriculum—social and civic competence was claimed as part of the area of Social Sciences Didactics. Santisteban (2009) understands that this competence must be worked on through the approach and resolution of social problems since most of the issues that people face in their daily lives “have to do with personal relationships, social values or the experiences of men and women. In addition, these problems are often of an economic, political, sociological or anthropological nature” (p. 12).

In this sense, the role of teachers is essential in the development of this competence, as they “propose or help in defining the problem-situations, create the conditions to solve them and provide information, show possible ways of reasoning, encourage reflection and debate, lead towards an attitude open to discovery, and help in reviewing the ideas” (Santisteban 2009, p. 12). All of this is linked to learning about the future, to consider the future as part of our subject in this permanent dialogue with the past and the present.

Classroom work on social and civic competence must ensure that children and teenagers in our schools understand and act, that they are able to solve problems, that they imagine the future and, above all, that their projects do not end up in oblivion or inaction (Santisteban 2009, p. 15).

However, the vindication of the work on social and civic competence, and the development of social thinking have not only remained at the theoretical level. Moreover, there is research on the implementation of educational proposals along these lines. Santisteban et al. (2014); Santisteban (2019) presented a study on the introduction of controversial issues to address citizenship competence and the development of social thinking, in which they explored social representations, developed curricular materials, and analyzed their implementation.

Ross and Vinson (2012) introduce the concept of “dangerous citizenship”, which is important to highlight at this point as it refers to a critical, social justice-oriented citizenship that resists the dominant power, i.e., that opts for the implementation of participation, to which it gives a fundamental role.

Both research and proposals for curriculum organization based on socially acute questions have grown considerably in the Didactics of Social Science in Spain. However, its transference to the educational system is slow and its presence is rare. Therefore, it is necessary to act in teacher training to change this scenario. According to Pagès (2007), the approach focused “on relevant social problems is a great opportunity for citizenship education since, as Dewey proposed, it brings young people closer to the world and prepares them for life” (p. 208).

2.2. Migration as a Relevant Social Problem

The social question chosen for this work is frequently shown in the media, especially with the arrival of African migrants across the Mediterranean, which is the source of two of the images used in this research. However, it should be pointed out that it is not migration itself that is the subject in this research, but rather forced migration and the conditions in which people are forced to move.

In 1950, the UN created the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and in 1951 “refugee” was defined as a person who “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his [or her] nationality”. The problem with this definition of refugee lies mainly in its limitations, as people displaced by war or natural disasters, for example, are not considered to be refugees, something that does not seem to be changing for the time being for the United Nations.

Those who cannot prove that they face persecution in their home country are not considered refugees and are seen as “economic migrants”, a distinction soon made by the receiving countries as to whether to accept asylum. Migrants are considered a burden on the state in the main so-called “rich” receiving areas—mainly the United States, Europe, and Australia—thus, the existence today of numerous border controls, as well as major people-smuggling mafias.

The work of Kabunda (2017) presents an interesting synthesis of migration in Africa. Among the factors that generate migratory movements are wealth inequality, the existence of transnational networks, and the degree of poverty in the countries of origin and rejection by the receiving ones. Apart from the causes, the positive aspects of migratory phenomena for both Africa and Europe were also presented, which are mainly two-fold: The arrival of remittances in the countries of origin and the rejuvenation of the population in the countries of destination.

These remittances are estimated to represent 3% of Africa’s GDP. In addition to financing families’ necessity goods and prestige, these remittances contribute to improving aspects of social justice and human development in the countries of origin and therefore contribute to reduce poverty. According to the World Bank, the 20 million African immigrants transferred nearly 31 billion dollars to Africa in 2014. Moreover, the intangible benefits generated by social and cultural remittances should be underlined (Kabunda 2017, p. 46). Furthermore, some of the advantages of the migration’s impact in Spain are included in the Report Immigration in Spain: Effects and Opportunities (Economic and Social Council of Spain 2019).

The positive effects of migration in economic terms are not the exclusive patrimony of the countries of origin, but there are also benefits for the receiving areas. For the European Union, “migration is an economic necessity not only due to the growing ageing of the population, but also due to the need, as in the previous case, for cheap migrant labor” (Kabunda 2017, p. 46). Beyond all of the economic stimulus that migration can bring, the human rights violations that are taking place not only in the countries of origin, but also in the countries of destination, as well as in the so-called transit zones, must be taken into account (Table 1).

Table 1.

Violation of migrants’ human rights.

The solution to this relevant social problem lies “not in the closure of borders, but in the efficient management of circular migration in order to achieve brain gain (the cost-effectiveness of human capital circulation)” (Kabunda 2017, p. 49). Undoubtedly, the promotion of measures in the countries of origin—such as the recovery and fulfilment of the social and economic functions of the state in African countries, demographic transition, training, and generation of infrastructures and technologies, etc.—could be part of the solution.

Although brief, the above data are sufficiently representative of the fact that the displacement of people throughout the world generates strong conflicts and great inequalities, which are a constant violation of human rights, representing today one of the major social problems on a global scale.

2.3. Research on the Migration Problems in the Social Sciences Didactics

For the last section of our theoretical framework, we have conducted a literature review in order to identify other research that has recently dealt with migration from an educational research perspective, mainly in the Spanish context. We have not focused on research on immigrants in the education system—of which there are numerous works, such as those of Fernández-Batanero (2004), Ortiz (2008) or the report on educational challenges in the face of immigration (Aja et al. 1999), among others—but we are specifically interested in an area with a smaller production: Representations and how to approach migrations from the perspective of teaching and learning in Social Sciences.

One of the studies that most closely resembles what we intend to accomplish in this paper is the recent work by Gil et al. (2018) on the representations of immigration in children in the last year of primary school. The research, carried out through a questionnaire and a focus group, deals with the family history of the students to find out the ideas surrounding the statement “we are all immigrants”. The research concludes that the students’ social representations “differentiate the immigrant and the foreigner, the former as someone who moves out of necessity, especially for economic reasons, conflicts or insecurity, the latter as someone who goes to another country, without further descriptions” (p. 32). In addition, the authors were satisfied with the favorable attitudes of the participating primary school children towards migrants.

In a study carried out by Llonch et al. (2014) for the same educational stage, but in two different contexts, the authors proposed the encouragement of motivation through the migratory roots of the students and an interesting didactic proposal. Initially, the participating students were familiar with the term immigration, but they had a negative view of it. Then, with the implementation of the proposal, this view changed. However, this work is more about the analysis of the didactic proposal carried out and the didactic materials generated rather than the change in social representations. Moreover, noteworthy is the work by Tosar et al. (2016) on critical literacy based on the interpretation of information of the recent refugee crisis.

Serulnicoff and Bernardini (2015) presented a reflection on the teaching of migration processes to children, questioning some of the methodologies through which this topic was introduced in Argentinean schools and proposing a series of resources for its inclusion in the classroom, ranging from testimonies to itineraries, including fragments of letters, all of them quite conventional.

Haro et al. (2016) incorporated immigration into a teaching proposal for the 3rd year of ESO based on controversial issues. The authors called the didactic unit: What about immigration? In addition, they posed a series of questions about the motivating force of migrants, their sociology, and the role of institutions, formulating three interesting questions for debate: What happens to the migrants who arrive? What does the receiving population think? What does it mean to live in a multicultural society? (p. 401). The authors conclude that “knowledge and understanding of other people and cultures require students to constantly question their own social reality, to acknowledge social problems and their causes”, and that this “helps them in recognizing the complexity of respecting different points of view in order to become aware of the need to build multicultural and multi-identity societies” (p. 405).

Although more examples could be included, we will discuss three research studies that focus on initial teacher training. Jiménez et al. (2002) presented an experience of working on immigration in the classroom. Of particular interest is the work of Rodríguez-Izquierdo (2009) on the social image of immigrants held by trainee teachers. Although the author focuses on attitudes through semantic differential rather than on social representations, she reaches important conclusions. She notes minority attitudes of explicit rejection, although tolerance predominates. According to Rodríguez-Izquierdo (2009) “the reactions of the students can be classified as a receptive attitude, of unreserved acceptance or what we call optimistic multiculturalism” (p. 272).

The issue of refugees and migrants from the perspective of Citizenship and Civic Education was explored in a recent monograph (Acikalin et al. 2021), in which the work of Blanck (2021) stands out, addressing teachers’ prior ideas about migration and their decisions to guide educational practice on this issue.

Moreover, there is research on the treatment of migration in textbooks, such as the work of Taboada (2016, 2018) or Balsas (2013, 2014) for the Argentinean case. Finally, it is worth highlighting the thesis by Haro (2017) on social justice, which incorporates the analysis by secondary school students of an image on the rescue of immigrants (p. 203).

Increasing knowledge about migrants, a heterogeneous reality, fostering a change in attitudes, and the involvement in the resolution of social problems, are the main purpose of the educational treatment of this subject. This is a major social problem of global scope, and throughout this theoretical framework, this issue has been discussed in relation to the main theoretical references on social problems relevant to the Didactics of Social Sciences.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questions, Premises, and Objectives

As mentioned above, the main objective of this research is to learn about the students’ representations of migrants in the last year of primary school (6th grade, 11–12 years old), with special attention to the Mediterranean case. These representations have been developed mainly through information from the social environment, including the media (Araya 2002). The research questions to be answered in this paper are the following:

- What are the social representations of forced migration that 6th-year primary school students have?

- What are the opinions they have about this social problem?

- What are the solutions that they propose to repair this relevant social problem?

- Where does the information they have about this issue come from and what do they think about the school’s approach to it?

Based on the existing literature and the research we have previously carried out, we begin with several premises. The first, based on the study by Gil et al. (2018) on primary school students’ conceptions of immigration, is that these students have social representations, which they associate with the idea of physically moving people to another place and which come from different sources of information. As a second premise—and following the same study—students at the end of primary school identify the causes of this phenomenon, mainly through economic motivation. In addition, and as a third premise, students have opinions about this phenomenon. Moreover, looking at the study by Gil et al. (2018), and at the one by García-Morís and Oller (2022), we observe that students recognize some sensitive issues such as racism, relating it to aspects such as skin color or religion. There are no prejudices or negative attitudes towards immigrants, and students are also favorable towards their curricular treatment. These research questions, and the initial premises, are intended to be verified through the following objectives:

- To analyze the social representations of forced migration among students at the end of the primary school stage.

- To analyze the opinions that students in the last year of primary school have about the situations that migrants go through.

- To identify the solutions that the children propose for this social problem.

- To analyze the contexts in which the students learnt what they know about this social problem and their opinion about the inclusion of this content in the curriculum.

3.2. Participants

The study was carried out with the 6th-year primary school groups (11–12 years old) of a state-supported private school in the city of A Coruña (Galicia, Spain), a Catholic school that receives public funding. The socio-economic level of families is average, and the majority of pupils are Spanish-born (89%), although there are some children born in or with at least one parent from other countries, mainly Latin America (11%).

The sample was based on accessibility and convenience, as the individuals were easily approachable by the authors. The school follows a traditional methodology, although it is characterized by carrying out numerous solidarity projects to help people in at-risk situations.

Eighty-nine percent of the children’s families are of Spanish origin and 11% are from foreign families or with one of the parents of a non-Spanish origin. Within the latter case, the Venezuelan nationality stands out (38% of foreign families). Moreover, it was found that 21% of the students had a family member (mother or father) who had been an emigrant outside of Spain at some point in their lives.

3.3. Research Instrument

A questionnaire was designed for the research, based on the model of Pagès and Oller (2007) for the study of Catalan teenagers’ representations of law and justice, which was used for this study and for García-Morís and Oller’s (2022) work on social representations of migration among secondary school students.

The questionnaire was divided into two parts, with a series of open-ended questions with images for the students to answer freely. The first part, entitled “What do these images tell me?”, comprises questions 1 to 4, and includes the students’ interpretations of the selected images, inquiring about the representations, causes, opinions, and possible solutions to this social problem. Each of the images reflects a migration situation present in society, thus it was expected that they would be familiar or close to them. The images were not accompanied by any kind of prior information.

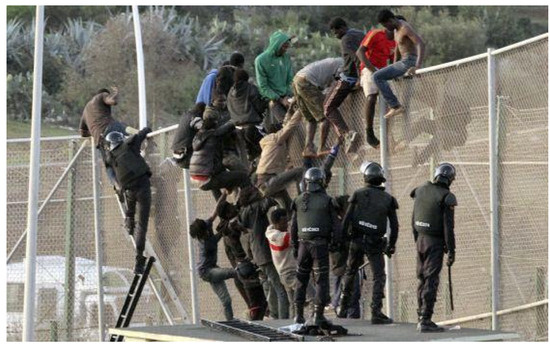

Three media images were included in the questionnaire. The first two belong to scenes of migration in the Mediterranean (Figure 1 and Figure 2) and the third to refugees in Mexico (Figure 3). The images were chosen from a wider selection since they depicted different moments experienced by migrants in forced displacement. One image was about displacement by sea and the risks involved, the second about transit, and the last reflected the walls and deprivation of freedom of passage and movement of migrants.

Figure 1.

(Rescue) from the questionnaire. Source: Boats in the Mediterranean. Photograph by Ricardo García Vilanova. Libyan waters 2016. El Periódico.

Figure 2.

(Fence) from the questionnaire. Source: Photograph by Antonio Ruiz. Melilla, October 2014. El País.

Figure 3.

(Refugees) from the questionnaire. Source: https://www.elnuevodiario.com.ni/internacionales/420740-mexico-pais-transito-pais-acogida-refugiados/ (accessed on 20 September 2021).

3.4. Method of Data Collection and Analysis

The questionnaire was printed on paper and distributed to all of the 6th-year primary school groups during a Social Studies lesson. The data were processed using the commercial software Microsoft Excel, which allowed the responses to be categorized and quantified.

The procedure followed for data analysis was different for each question. The images were presented to the students without any explanation of their origin or the situation portrayed in them. Question 1 made it possible to analyze the representations, grouping similar concepts that described or analyzed the reality represented. The same procedure was followed for questions 2, 3, and 4, which focused on the causes, opinions, and possible solutions to this problem. Question 5 was closed, thus the answers were quantified, and question 6, related to the teaching and learning process of these subjects, was processed by grouping those with identical answers.

4. Results

4.1. Social Representations of Migration

4.1.1. The Interpretation of Images

In the first point of the questionnaire, students were asked to answer questions from the photographs such as What people do you see? What is happening? Why is it happening?

The interpretation of Figure 1 (Rescue) was contextualized. As can be seen in Table 2, students associate the forced displacement of people with causes intrinsic to the countries of origin, such as fleeing war (15.69%), poverty (15.33%) or seeking a better life (12.04%). Within this contextualized analysis, demographic concepts such as immigrants (10.58%) or emigrants (9.12%) are incorporated. There is another group of answers that identify the elements of the image, but in a less contextualized way, referring to the protagonists of the scene as “people in boats” (8.76%), people fleeing (7.66%) or simply boys, girls, men, and women (5.84%) or even lifeguards (4.01%) and black men (2.55%). To a lesser extent, political and economic problems or the impossibility of legal migration are mentioned.

Table 2.

Social representations from Figure 1 (Rescue).

Moreover, the interpretation of Figure 3 (Refugees) was analyzed in a contextualized way (Table 3), since in the narratives constructed by the children to respond to the queries in the questionnaire—although they refer to “people fleeing” (21.94%)—they incorporated concepts such as “fleeing poverty” (15.83%), “migrating” (11.87%), “fleeing war” (8.99%) or “seeking a better life” (8.63%), i.e., responses that reflect an interpretative analysis of the image, mainly associated with intrinsic causes in the countries of origin. To a lesser extent, other more descriptive concepts are used, such as “walking on the tracks” (8.27%) or looking for a place to sleep (0.72%). Furthermore, they associated the images with being in danger (5.76%), immigrating (2.52%), having no money or work (3.96%) or being poor (2.88%). One of the pupils identifies the image as a Syrian family.

Table 3.

Social representations from Figure 3 (Refugees).

The interpretation of Figure 2 (Fence) received some clearly descriptive responses such as “boys jumping a fence” (13.8%), young boys (10.14%) or even, in one case, a group of friends (Table 4). In the descriptions, students identified the presence of the police (10.81%) as “the police blocking their way” (8.78%) or “chasing them” (5.74%). In other words, 25.68% of the responses referred to the police being present at the scene, making them the most identified elements in the narratives. Only one case analyzes the police presence positively, considering that “the police helps them”. In a more interpretative way, another group of answers identified people fleeing (12.16%) or linked the scene again to causes such as poverty (7.43%), the search for a better life (6.76%) or war (5.74%). For some of the students, they are immigrants (4.39%), border-crossers (4.73%), and 5.41% are identified as “people who are escaping from prison”, i.e., in a negative view.

Table 4.

Social representations from Figure 2 (Fence).

To further explore the causes, a second question was included with the following wording: Why do you think the people in the images are travelling or moving from place to place? (Table 5). The results confirm the responses analyzed above, as they place the causes in the war in the countries of origin (29.23%), poverty (29.23%), seeking a better life (20%) or fleeing from dangerous situations (10%). The political and economic situation (7.69%) or homelessness are among the causes least mentioned by students (3.85%).

Table 5.

Identified causes.

4.1.2. Students’ Views on the Events Observed in the Images

In addition, the questionnaire asked for the students’ opinions of what was happening in the images. As can be seen in Table 6, the most repeated answers reject the existence of these situations, with 23.81% of the answers stating that “this situation should not happen”. This is followed by “it is worrying” (20.95%) or “it is unfair” (14.29%). In other words, there is a clear rejection of forced migration. In general, students are aware that these people have a hard time (6.67%) and that solutions need to be found (13.33%), which is why they advocate equal rights and opportunities (4.76%) as one of the possible solutions. Only one case of a pupil considered that it was not their problem.

Table 6.

Students’ opinions.

4.1.3. Possible Solutions to Forced Migration Proposed by Students

Finally, the proposed solutions provided by the students are analyzed (Table 7). The majority of the children support the option of helping, and within this, the following forms of help are included: Giving money, food, work, and housing, solutions which account for over 53% of the total responses. Moreover, ending war (13.64%) or seeking equal rights and opportunities (10.91%) are recurrent solutions.

Table 7.

Proposed solutions by students.

Furthermore, 6.36% consider that the solution lies in solidarity and in the support and empowerment of NGOs (5.45%). Another solution, following the students’ terminology, would be to “let them move to other countries” (4.55%) or to eliminate racism (1.82%). Although not very representative, the solution proposing a correct election of the president is striking (2.73%). Once again, we find a response that considers that it is “not my problem”, but, as can be seen, the majority of answers place the solutions in the destination countries, externally, not in the countries of origin and their people.

4.2. The Educational Approach to Forced Migration as a Relevant Social Problem

4.2.1. Where Have They Learned What They Know about this Social Problem?

All of the students answered affirmatively when asked if they had ever heard of or read about this social problem. In addition, when asked where this information came from, they put the media in the first place, mainly the news (34.43%) (Table 8). The family is in second place (20.77%) and, significantly behind, the school (12.57%). To a lesser extent, the newspaper (12.02%), the Internet (10.93%), others (7.10%), and through friends (2.19%).

Table 8.

Where students learned that they know about the issue.

4.2.2. Why Address This Issue in the Classroom?

First, we asked the students whether they thought it was necessary to address this issue in the classroom. Eighty-seven percent of the answers were affirmative, compared to the 12% that were negative. Those students who considered it important to address this issue said that it was necessary to know about it to “be informed” (39.78%) (Table 9). Moreover, they considered it important to “help” (19.35%) and to “raise awareness” (18.28%). Furthermore, it was considered important to address these issues to “prevent them from happening” (8.60%) and to try to achieve equal rights and opportunities (3.23%). Finally, 8.60% simply felt that it was important to be aware of the issue.

Table 9.

Why address this issue in the classroom.

5. Discussion

The first of the premises made was that students have social representations about migration, a concept they associate with the idea of the physical movement of people from one place to another, identifying part of its causes. The research verified this premise, confirming that, in their narratives, 6th-year primary school children use some concepts from the Social Sciences to explain what they see in the images of forced migration. In order to interpret them, they use some of the causes of the phenomenon in their arguments, as was presented in the second premise. Given that we have carried out a previous study (García-Morís and Oller 2022), with the same instrument but with pupils at the end of the secondary stage, in this section we make some comparisons between the social representation made by students at both educational stages.

Among the main causes identified are economic, conflict, and insecurity, which are consistent with the study by Gil et al. (2018) and also with the research we have conducted with secondary school students in a study similar to the present one (García-Morís and Oller 2022). In other words, the conception of the migrant as someone who “moves out of necessity, especially for economic reasons, conflicts or insecurity” (Gil et al. 2018, p. 32) occurs both at the end of primary school (12 years old) and secondary school (16 years old). In the case of secondary school students, most of the causes are found in the countries of origin. However, they also identified some external causes, showing a lack of analysis with a historical perspective, of interdependence between countries, characteristic of a global world. Logically, in the case of primary school students, given their age, the causes are simplified, and all of them were contextualized in the countries of origin, excusing developed countries from any kind of responsibility.

As a third premise, we maintained that students had opinions about this phenomenon, which we have verified in this study. The opinions of students at the end of secondary school on migration phenomena are often stereotypical, although they were favorable towards migrants and focused mainly on describing the events. In the case of 6th-year children, most of the opinions also focus on describing the situation, rejecting that it happens.

The possible solutions provided by students to this social phenomenon can be grouped into those that are in the hands of the countries of origin, and those that are given to countries of destination, mainly developed countries. In the case of secondary education, there is a Europeanist vision with little perspective of otherness, which—although it does not reach the geographical, cultural, and even ethnic determinism identified in similar research at the end of the last century (Gil 1993)—only gives importance to the developed countries in the solutions. In the case of primary education, this was even more intense, as the solutions provided were dominated by the resolution of this social problem in the form of economic aid. In other words, solving the problem from outside and without giving the countries of origin and their citizens the capacity to overcome their current situation.

As mentioned above, primary school students, as well as secondary school students, shape their representations through different sources of information. In both cases, they point to television as the main source from which they have learned something about this issue, most likely since the arrival of immigrants, especially from Africa to Spain, is a constant in the media, and children also consume news in the family environment. Another coincidence between students at both states is that, after the news, the family is the second most important source of information. In the case of primary education, the school is the third place, and in secondary education, the Internet is the third most popular source of information.

Regarding the need for the curricular inclusion of these topics, both secondary and primary school students consider it important to address them in the class. Although in the case of secondary school the first reason for their inclusion is to raise awareness, while primary school students opt for being informed as the first option. We agree with Blanck (2021) that, although 12-year-olds may be too young to understand phenomena in a structural way, it is “important not to underestimate what pupils already know and have the opportunity to understand” (p. 97). Therefore, addressing social problems in the classroom is essential to place Social Sciences in the orbit of citizenship education and to work on social and civil competence (Santisteban 2009), and to develop critical social sciences for social change (Gil et al. 2018). Gil et al. (2018) considered that working on migration is very necessary “to differentiate the causes for which people are forced to leave their homes and become migrants, displaced persons, exiles or refugees” (p. 33). There is no doubt that a theoretical deepening of these issues is needed, something that should also be done at the primary stage.

Furthermore, migrations can be approached by relating them to family and local experiences, which is an interesting didactic opportunity and helps in empathizing with other cultures and working on diversity (Balsas 2013; Blanck 2021; Gil 1993; Gil et al. 2018; Hammond 2010). Therefore, it is necessary to take advantage of their educational opportunities (Ernst-Slavit and Morrison 2018), which also contributes to combat possible xenophobic discourses (McCorkle 2018).

6. Conclusions

The curricular inclusion of social problems, either by organizing the curriculum through socially acute questions or through the problematization of historical and geographical contents of a more classical nature, clearly dominates research in Didactics of Social Sciences in Spain. However, and despite the regulatory changes that are taking this perspective into account, the real transference of this model to primary and secondary classrooms is slow. For this to become a reality, it is necessary to act in the initial training of teachers, in order for the curricular deficiencies to be complemented in the development of the curriculum in the classroom. As has been observed, primary school children are favorable to including these social issues in the curriculum. Therefore, it is necessary to continue exploring the representations in order to formulate well-oriented didactic proposals that contribute to the development of critical citizenship, the main purpose of Social Sciences.

However, although we are dealing with a case study, focused on a specific school, which we have also carried out with secondary school students (García-Morís and Oller 2022) and whose conclusions are not generalizable, it is common to observe in the results of this type of studies that pupils are in favor of the inclusion of these current social issues as a central theme in Social Sciences subjects. This curricular approach contributes to the development of an education for citizenship and human rights, which is why its development represents a great educational opportunity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G.-M. and N.G.B.; methodology, R.G.-M. and N.G.B.; formal analysis, R.G.-M. and N.G.B.; investigation, R.G.-M., N.G.B. and R.M.-M.; resources, R.G.-M., N.G.B. and R.M.-M.; data curation, R.G.-M., N.G.B. and R.M.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.-M. and R.M.-M.; writing—review and editing, R.G.-M. and R.M.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of the project Children’s, adolescents’, and youth rights: Inhabiting activist projects with students, teachers, and contemporary artists of the State Programme for Knowledge Generation and Scientific and Technological Strengthening of the R&D&i System and R&D&i Oriented to the Challenges of Society, of the State Plan for Scientific and Technical Research and Innovation 2017–2020; funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Government of Spain, with code: PID2020-117147RA-I00, and Principal Investigator: José María Mesías Lema.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acikalin, Mehmet, Olga Bombardelli, and Gina Chianese. 2021. Editorial: Citizenship and Civic Education for Refugees and Migrants. Journal of Social Science Education 20: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aja, Eliseo, Francesc Carbonell, Colectivo Ioé, Jaume Funes, and Ignasi Vila. 1999. La Inmigración Extranjera en España. Los Retos Educativos. Barcelona: Fundación La Caixa. [Google Scholar]

- Araya, Sandra. 2002. Las Representaciones Sociales: Ejes Teóricos Para su Discusión. San José: Flacso-Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales. [Google Scholar]

- Audigier, François. 2001. Les contenus d’enseignement plus que jamais en question. In Entre Culture, Compétence et Contenu: La Formation Fondamentale, un Espace à Redefinir. Edited by Christiane Gohier and Suzanne Laurin. Montréal: Éditions Logiques, pp. 141–92. [Google Scholar]

- Balsas, María Soledad. 2013. A imaxe dos inmigrantes galegos nos libros de texto arxentinos. Revista Galega de Educación 56: 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Balsas, María Soledad. 2014. Las Migraciones en Los Libros de Texto. Tensión Entre Globalización y Homogeneidad Cultural. Buenos Aires: Editorial Biblos. [Google Scholar]

- Benejam, Pilar. 1992. La didàctica de la geografia des de la perspectiva constructivista. Documents D’anàlisi Geográfica 21: 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Benejam, Pilar. 1997. Las finalidades de la educación social. In Enseñar y Aprender Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia en la Educación Secundaria. Edited by Pilar Benejam and Joan Pagès. España: Horsosi, pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bergamaschi, Alessandro. 2011. Attitudes et représentations sociales. Les adolescents français et italiens face à la diversité. Revue européenne des sciences sociales. European Journal of Social Sciences 49: 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Blanck, Sara. 2021. Editorial: Teaching about migration. Teachers’ didactical choices when connecting specialized knowledge to pupils’ previous knowledge. Journal of Social Science Education 20: 70–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic and Social Council of Spain. 2019. Report Immigration in Spain: Effects and Opportunities. Madrid: Economic and Social Council of Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst-Slavit Gisella, Steven Morrison. 2018. “Unless You Were Native American… Everybody Came From Another Country:” Language and Content Learning in a Grade 4 Diverse Classroom. The Social Studies 109: 309–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Ronald. W. 1991. Concepciones del maestro sobre la historia. Boletín de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales 3: 61–94. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Ronald W., and David Warren Saxe, eds. 1996. Handbook on Teaching Social Issues. Washington: National Council for the Social Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Batanero, José María. 2004. La presencia de alumnos inmigrantes en las aulas: Un reto educativo. Educación y Educadores 7: 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fien, John. 1992. Geografía, sociedad y vida cotidiana. Documents D’anàlisi Geográfica 21: 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- García-Morís, Roberto, and Montserrat Oller. 2022. Enseñar y Aprender las Migraciones Forzosas en Ciencias Sociales. Magis, Revista Internacional de Investigación en Educación 5. Unpulished Work. [Google Scholar]

- García-Pérez, Francisco Florencio. 2014. Ciudadanía participativa y trabajo en torno a problemas sociales y ambientales. In Una Mirada al Pasado y un Proyecto de Futuro: Investigación e Innovación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Edited by Joan Pagès and Antoni Santisteban. Barcelona: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, vol. 1, pp. 119–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, Francisco, Sandra Muzzi, and Antoni Santisteban. 2018. Todos y todas somos inmigrantes: Representaciones de niñas y niños de primaria sobre la inmigración. REIDICS: Revista de Investigación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales 2: 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, María Encarna. 1993. Las concepciones de los alumnos sobre el tercer mundo al acabar la escolaridad obligatoria: Participación de la institución escolar en la formación, mantenimiento o refuerzo de las mismas. Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales y Sociales 7: 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, Thomas. 2010. “So What?” Students’ Articulation of Civic Themes in Middle-School Historical Account Projects. The Social Studies 101: 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, María del Rosario, María Teresa Call, Montserrat Yuste, and Montserrat Oller. 2016. ¿Qué pasa con la inmigración? Una propuesta didáctica para la comprensión de la pluriidentidad. In Deconstruir la Alteridad Desde la Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Educar Para una Ciudadanía Global. Edited by Carmen Rosa García, Aurora Arroyo and Beatriz Andreu. Las Palmas: AUPDCS, pp. 398–405. [Google Scholar]

- Haro, María del Rosario. 2017. Una Proposta D’innovació Curricular per Treballar la Justícia Social a l’aula de Secundària: Una Reflexió Sobre la Pròpia Pràctica. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, David W., and E. Wayne Ross, eds. 2000. Democratic Social Education. Social Studies for Social Change. New York: Falmer Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, María Dolores, Socorro Sánchez, Carmen Rosa García, and Concepción Moreno. 2002. Trabajamos la inmigración en el aula. Una experiencia desde la formación inicial de maestros y maestras. Kikiriki. Cooperación Educativa 65: 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jodelet, Denise, ed. 1989. Les Représentations Sociales. París: PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Kabunda, Mbuyi. 2017. Migraciones, derechos humanos y desarrollo. El caso africano. In Derechos Humanos, Migraciones y Comunidad Local. Andalucía: Fondo Andaluz de Municipios para la Solidaridad Internacional (FAMSI), pp. 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux, Anne. 2002. Enseigner L’histoiregéographie par le Problème? París: L’Harmatan. [Google Scholar]

- Legardez, Alain. 2003. L’enseignement des questions sociales et historiques, socialement vives. Le Cartable de Clio 3: 245–53. [Google Scholar]

- Legardez, Alain, and Laurence Simonneaux. 2006. L’école à l’épreuve de l’actualité. Issy-Les-Moulineaux: ESFEditeur. [Google Scholar]

- Llonch, Nayra, Mireia Gonell, and Pilar Isern. 2014. Abordando las raíces migratorias en el aula: Análisis y comparativa de una misma implementación didáctica en diferentes contextos. Clío: History and History Teaching 40: 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Marolla, Jesus, and Joan Pagès Blanch. 2015. Ellas sí tienen historia. Clío & Asociados 20–21: 223–36. [Google Scholar]

- McCorkle, William. 2018. The Rationale and Strategies for Undermining Xenophobia in the Classroom. The Social Studies 109: 151–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, Serge. 1976. La Psychanalyse, Son Image, Sonpublic. París: PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Oller, Montserrat. 1999. Trabajar problemas sociales en el aula, una alternativa a la transversalidad. In Un Currículum de Ciencias Sociales Para el Siglo XXI: Qué Contenidos y Para Qué. Edited by Teresa García Santa María. La Rioja: AUPDCS, pp. 123–31. [Google Scholar]

- Oller, Montserrat. 2011. Ensenyar geografia a partir de situacions problema. Perspectiva Escolar 358: 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Olmos, Rafael, and Joan Pagès. 2017. Cambios y continuidades en las representaciones sociales de un mismo grupo de chicos y chicas sobre la crisis económica. In Investigación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Retos Preguntas y Líneas de Investigación. Edited by Ramón Martínez, Roberto García-Morís and Carmen Rosa García. Córdoba: AUPDCS, pp. 720–29. [Google Scholar]

- Olmos, Rafael, González-Monfort Neus, and Joan Pagès. 2017. Las representaciones sociales del alumnado sobre la crisis. ¿Qué soluciones ofrece el alumnado ante los problemas económicos? Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales y Sociales 32: 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Delfin, and Joan Pagès. 2017. Las representaciones sociales de los problemas contemporáneos en estudiantes de magisterio de Educación Primaria. Revista Investigación en la Escuela 93: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, Monica. 2008. Inmigración en las aulas: Percepciones prejuiciosas de los docentes. Papers: Revista de Sociología 87: 253–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagès, Joan. 1994. La didáctica de las ciencias sociales, el currículum y la formación del profesorado. Signos. Teoría y Práctica de la Educación 13: 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès, Joan. 2007. La enseñanza de las ciencias sociales y la educación para la ciudadanía en España. Didáctica Geográfica 9: 205–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès, Joan. 2016. La ciudadanía global y la enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales: Retos y posibilidades para el futuro. In Deconstruir la Alteridad desde la Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Edited by Carmen Rosa García, Aurora Arroyo and Beatriz Andreu. Las Palmas: AUPDCS, pp. 713–730. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès, Joan, and Montserrat Oller. 2007. Las representaciones sociales del derecho, la justicia y la ley de un grupo de adolescentes catalanes de 4º de ESO. Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales: Revista de Investigación 6: 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès, Joan, and Antoni Santisteban. 2011a. Les qüestions socialment vives i l’ensenyament de les ciències socials. Barcelona: Servei de Publicacions de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès, Joan, and Antoni Santisteban. 2011b. Enseñar y aprender Ciencias Sociales. In Didáctica del Conocimiento del Medio Social y Cultural en la Educación Primaria: Ciencias Sociales Para Aprender, Pensar y Actuar. Edited by Antoni Santisteban and Joan Pagès. España: Síntesis, pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Izquierdo, Rosa María. 2009. Imagen social de los inmigrantes de los estudiantes universitarios de magisterio. Revista Complutense de Educación 20: 255–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Wayne, and Kevin D. Vinson. 2012. La educación para una ciudadanía peligrosa. Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales: Revista de Investigación 11: 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas, Juan José. 2017. Transformando las Representaciones Sociales de la Participación Ciudadana Mediante la Acción Sobre Problemas Sociales de la Comunidad. Una Investigación-Acción con Estudiantes de Secundaria. Ph.D thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas, Juan José, and Montserrat Oller. 2017. Debatiendo temas controversiales para formar ciudadanos. Una experiencia con alumnos de secundaria. Praxis Educativa 21: 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salinas, Juan José, Monterrat Oller, and Calos Muñoz. 2016. Representaciones sociales de la participación ciudadana en docentes de ciencias sociales: Perspectivas para la nueva asignatura de formación ciudadana en Chile. Foro Educacional 27: 141–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sant, Edda, María Teresa, asas, and Joan Pagès. 2011. Participar para aprender la democracia. Las representaciones sociales de jóvenes catalanes sobre la participación democrática. Uni-Pluri/Versidad 11: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, Antoni, Neus González-Monfort, Joan Pagès, and Montserrat Oller. 2014. La introducción de temas controvertidos en el currículo de ciencias sociales: Investigación e innovación en la práctica. In Historia e Identidades Culturales. Edited by Joaquin Prats, Isabel Barca and Ramón López-Facal. Barcelona: Universidad de Barcelona, pp. 310–22. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, Antoni. 2009. Cómo trabajar en clase la competencia social y ciudadana. Aula de Innovación Educativa 187: 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, Antoni. 2019. La enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales a partir de problemas sociales o temas controvertidos. Estado de la cuestión y resultados de una investigación. El Futuro del Pasado: Revista Electrónica de Historia 10: 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serulnicoff, Adriana. E., and Cecilia Bernardini. 2015. Reflexiones acerca de la enseñanza de procesos migratorios a niños pequeños. Didácticas Específicas 13: 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Simonneaux, Laurence, and Alain Legardez. 2010. The epistemological and didactical challenges involved in teaching socially acute questions. Journal of Social Science Education 9: 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, María Beatriz. 2016. Nación y migración: Revisión crítica de libros de texto para la enseñanza secundaria en la Argentina. Romanica Olomucensia 2: 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taboada, María Beatriz. 2018. Abordaje de sujetos migrantes y procesos migratorios en libros de texto de Ciencias Sociales. Un análisis de caso. Revista Educación 42: 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thénard-Duvivier Franck. 2008. L’enseignement des Questions Socialement Vives en Histoire et Géographie. Actes du Colloque Organisé par le SNES et le CVUH. Paris: ADAPT Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Tosar, Beogan, Antoni Santisteban, Albert Izquierdo, Joan Llusá, Roser Canals, Neus González-Monfort, and Joan Pagès. 2016. La literacidad crítica de la información sobre los refugiados y refugiadas: Construyendo la ciudadanía global desde la enseñanza de las ciencias sociales. In Deconstruir la Alteridad Desde la Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Educar Para una Ciudadanía Global. Edited by Carmen Rosa García, Beatriz Andreu and Beatriz Andreu. Las Palmas: AUPDCS, pp. 550–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tutiaux-Guillon, Nicole. 2011. Les qüestions socialment vives, un repte per a la història i la geografía escolars. In Les Qüestions Socialment Vives i L’ensenyament de les Ciències Socials. Edited by Joan Pagès and Antoni Santisteban. Barcelona: Servei de Publicacions UAB, pp. 25–39. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).